Abstract

Angelman syndrome (AS) is a neurogenetic disorder characterized by severe developmental delay with absence of speech, happy disposition, frequent laughter, hyperactivity, stereotypies, ataxia and seizures with specific EEG abnormalities. There is a 10–15% of patients with an AS phenotype whose genetic cause remains unknown (Angelman-like syndrome, AS-like). Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed on a cohort of 14 patients with clinical features of AS and no molecular diagnosis. As a result, we identified 10 de novo and 1 X-linked pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in 10 neurodevelopmental genes (SYNGAP1, VAMP2, TBL1XR1, ASXL3, SATB2, SMARCE1, SPTAN1, KCNQ3, SLC6A1 and LAS1L) and one deleterious de novo variant in a candidate gene (HSF2). Our results highlight the wide genetic heterogeneity in AS-like patients and expands the differential diagnosis.

Introduction

Angelman syndrome (AS, OMIM #105830) is a neurogenetic disorder with a prevalence of about 1/15000 births. AS is characterized by severe developmental delay/intellectual disability (DD/ID) with absence of speech and distinctive dysmorphic craniofacial features such as microcephaly and wide mouth. Neurological problems include ataxia and seizures with specific electroencephalogram (EEG) abnormalities. The behavioral phenotype is characterized by happy disposition, frequent laughter, hyperactivity and stereotypies [1]. The consensus criteria for the clinical diagnosis of AS was proposed in 2005 by Williams et al., [1] which included a list of (i) consistent, (ii) frequent and (iii) associated features. However, clinical manifestations of AS can overlap with other diseases.

AS is caused by the loss of function in neuronal cells of the ubiquitin protein ligase E6-AP (E6-Associated Protein) encoded by the UBE3A gene, which is located on chromosome 15q11-q13 imprinted region. Methylation study of this region identifies 75–80% of AS patients including maternal deletion, paternal uniparental disomy (UPD) and imprinting center defects. Pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in the UBE3A gene identify a further 10% of cases. However, for approximately 10–15% of clinically diagnosed AS patients, the genetic cause remains unknown (AS-like) [2].

Some of these AS-like patients present alternative clinical and molecular diagnoses in syndromes that have overlapping clinical phenotypes and that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of AS. AS differential diagnosis include single gene disorders such as Christianson syndrome (SLC9A6), Rett syndrome (MECP2), Pitt Hopkins syndrome (TCF4), Kleefstra syndrome (EHMT1), Mowat-Wilson syndrome (ZEB2) or HERC2 deficiency syndrome (HERC2). Individuals affected by the above mentioned syndromes present severe DD, seizures, postnatal microcephaly, absent or minimal speech and sleep disturbances as AS patients [3–5].

In order to further identify the molecular defects in AS-like patients, whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed in a cohort of 13 parent-patient trios and one single patient with clinical features of AS and no molecular diagnosis. Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in known neurodevelopmental genes were found in 78,5% of patients while a deleterious variant in a new candidate gene was identified in another patient. Overall, our results show that 10–15% of patients with a clinical but with no molecular diagnosis of AS present alternative genetic alterations in genes not previously associated with AS, expanding the genetic spectrum of AS-like.

Material and methods

Patient samples

14 patients (7 girls and 7 boys) referred to the Angelman syndrome Unit at the Parc Taulí Hospital Universitari (Sabadell, Spain) were enrolled in the study. Patient 1 has also been included in another study [6]. The corresponding written informed consent was obtained from all parents of each participant. The study was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee of Institut d’Investigació i Innovació Parc Taulí I3PT (CEIC 2016/668).

The clinical diagnosis was made between ages 11 months and 8 years. All patients presented neurodevelopmental phenotypes suggestive of AS including severe global developmental delay, speech impairment and a behavioral phenotype that included apparent happy disposition as the most remarkable feature. AS negative testing included the analysis of the methylation status of the SNURF-SNRPN locus and Sanger sequencing and intragenic deletions/duplications analysis of the UBE3A gene. In addition, no alterations were detected by array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH, ISCA 60 Kb, Agilent Technologies) and fragile X syndrome testing.

All the cases were sporadic and no other relevant findings were present in their family history.

Whole-exome sequencing and variant interpretation

Trio WES of 13 patients and their parents was performed using the SureSelect Human All Exon V5+UTR kit (Agilent technologies). In patient 4, WES was performed only in the patient sample. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina Hiseq2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) producing 2x100nt paired end reads at the National Centre of Genomic Analysis (CNAG-CRG, Barcelona, Spain). Raw data quality was assessed using FastQC software (v0.11.8, available at https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and an in depth analysis of each single generated FastQ file was performed to discard sequencing systematic errors and biases. On average, approximately 102.4 million reads per sample were generated during the sequencing process with an average GC content of 47.4% (standard deviation = 0.6%). Each sequenced base had on average a coverage of 67x and for each individual 87% of bases had a coverage >15. Raw reads were mapped to the human reference genome (hg19) using the Burrows-Wheeler aligner (BWA, v0.7.17-r1188) [7] and subsequently processed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) pipeline in order to remove PCR duplicates and perform base quality score recalibration. Reads with RMS Mapping Quality (MQ) = 255, with bad mates or a Phred mapping quality <20 were filtered out, only bases with Phred quality score>18 were considered for variant calling and only variants with Phred-scaled confidence>10 were called. Variant discovery was performed using the Haplotype Caller tool and following the best practices for exome sequencing variant discovery of GATK (v4.0.11.0) [8]. On average, 21,170 exonic variants were detected for each individual, among which on average 9,570 were missense variants, 351 were loss of functions, 237 were non-frameshift variants and 10,606 were synonymous variants. The remaining exonic variants were classified as “unknown” by ANNOVAR.

All exome variants were first checked against a de novo followed by an X-linked and autosomal recessive model of inheritance. In order to detect de novo variants, only variants with valid genotype and genotype quality ≥20 in all the trio members were considered. Variants having a read depth lower than 5 in the parents or lower than 10 in the patients were discarded. Only variants that were heterozygous in the patients but homozygous for the reference allele in the parents were considered. Finally, putative de novo variants were filtered considering only those showing the alternative allele in more than 10% of the reads.

According to an autosomal recessive model of inheritance, annotated variants were filtered for allele frequencies<0.02 in the gnomAD database (v2.1.1) and their predicted impact on the protein. X-linked variants were filtered for allele frequencies <0.001 and their predicted impact on the protein.

Both de novo and recessive variants were annotated using ANNOVAR (v:16.04.2018) [9] a tool suited for functional annotation of variants detected from high-throughput sequencing data and assessing the impact of missense variants leveraging several in silico tools (S1 Table). Splice site variants were evaluated using the software Human Splicing Finder [10].

Sanger sequencing of the candidate variants was performed in the patients and the parents in order to confirm the presence of the variant and the pattern of inheritance. Variants were classified following the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) guidelines [11]. Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants have been submitted to ClinVar [12].

Real time quantitative PCR (RTqPCR) analysis

RNA was extracted using the Biostic Blood Total RNA Isolation Kit sample (MO BIO laboratories, Inc) and cDNA was obtained using the PrimeScriptTMRT reagent Kit (Takara). RTqPCR gene expression analysis was performed in triplicate using the Taqman probes HSF2-Hs00988309_g1 and GADPH-Hs02758991_g1 for normalization (Applied Biosystems).

Results

Identified variants were first filtered according to a dominant de novo model of inheritance. Variants in genes known to be involved in neurodevelopmental diseases were prioritized and confirmed to be de novo. Overall, 10 de novo (SYNGAP1, VAMP2, TBL1XR1, ASXL3, SATB2, SMARCE1, SPTAN1, KCNQ3 and SLC6A1) and 1 X-linked (LAS1L) pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants were confirmed in 11 patients, leading to a diagnostic yield of 78,5% (Table 1). These variants were located in 10 different genes previously reported to be associated with neurodevelopmental disorders [6,13–21].

Table 1. Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants identified in AS-like patients.

| Patient | Gene | NM number | Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | Variant Type | Pattern of inheritance | ACMG/AMP Classification | Described before | Protein function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VAMP2 | NM_014232.2 | c.128_130delTGG | p.Val43del | In-frame | De novo | Pathogenic | Yes Salpietro et al., 2019 [6] |

VAMP2 is a member of the SNARE family of proteins, which are involved in membrane fusion of synaptic vesicles. |

| 2 | SYNGAP1 | NM_006772.2 | c.1861C>T | p.Arg621* | Nonsense | De novo | Pathogenic | No | SYNGAP1 is a RAS-GTPase-activating protein with a critical role in synaptic development, structure, function and plasticity. |

| 3 | TBL1XR1 | NM_024665.5 | c.1000T>C | p.Cys334Arg | Missense | De novo | Likely pathogenic | No | TBL1XR1 is part of the repressive NCoR/SMRT complex acting as a transcriptional regulator. |

| 4 | TBL1XR1 | NM_024665.5 | c.1043A>G | p.His348Arg | Missense | De novo | Likely pathogenic | No | |

| 5 | SATB2 | NM_001172509.1 | c.1826delA | p.Asp609Alafs*15 | Frameshift | De novo | Pathogenic | No | SATB2 participates in chromatin remodeling and transcription regulation. |

| 6 | KCNQ3 | NM_004519.3 | c.688C>T | p.Arg230Cys | Missense | De novo | Pathogenic | Yes Decipher and Miceli F et al., 2015, Sands TT et al., 2019 [20,22,23] |

KCNQ3 is a voltage-gated potassium channel subunits that underlay the neuronal M-Current. |

| 7 | SMARCE1 | NG_032163.1 (NM_003079.4) | c.237+1G>T | p.Ala53_Lys79del | Splice site | De novo | Likely pathogenic | Yes Aguilera et al., 2019 [24] |

SMARCE1 is part of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex involved in transcriptional activation. |

| 8 | SPTAN1 | NM_001130438.2 | c.6592_6597dupCTGCAG | p.Leu2198_Gln2199dup | In-frame | De novo | Likely pathogenic | No | SPTAN1 is an α-ΙΙ spectrin involved in stabilization and activation of membrane channels, transporters and receptors. |

| 9 | ASXL3 | NM_030632.2 | c.3106C>T | p.Arg1036* | Nonsense | De novo | Pathogenic | Yes Kuechler A et al., 2017 [25] |

ASXL3 plays a role in the regulation of gene transcription and histone deubiquitination. |

| 10 | LAS1L | NM_031206.4 | c.1237G>A | p.Gly413Arg | Missense | X-linked | Likely pathogenic | No | LAS1L is involved in the 60S ribosomal subunit synthesis and maturation of 28S rRNA. |

| 14 | SLC6A1 | NM_003042.3 | c.889G>A | p.Gly297Arg | Missense | De novo | Pathogenic | Yes Carvill GL et al., 2015 [26] |

SLC6A1 gene encodes for the GAT-1 GABA transporter. |

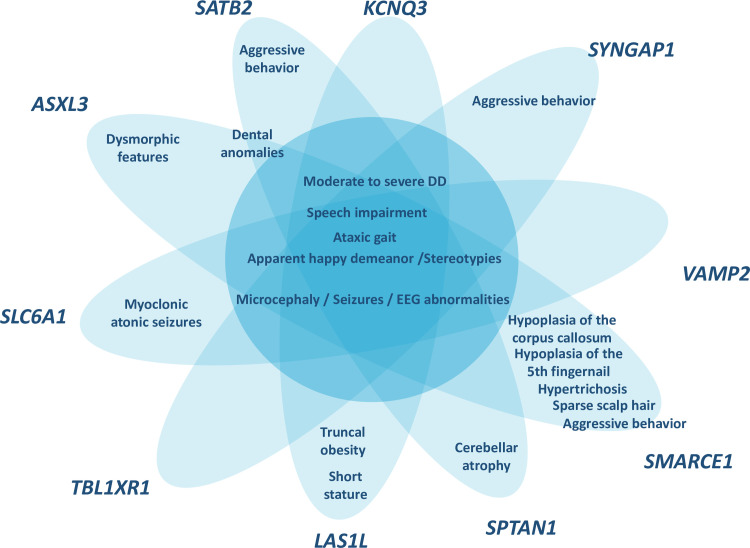

Clinical re-evaluation of patients at the time of the molecular diagnosis (ages between 9–38 years) showed that all patients met the consistent clinical features of AS (Table 2), except for ataxia of gait which was present in 9 of 14 patients. Even though the ataxia of gait is considered a consistent feature in AS patients, a recent review shows that it ranges from 72,7% to 100% according to the genetic etiology [27]. Additional clinical features identified in the clinical re-evaluation of patients were analyzed taking into account the clinical phenotype described for the genes identified. The presence of specific clinical features associated with the new genes were confirmed for some of the patients. In short, cerebellar atrophy for SPTAN1 [13], hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, hypoplasia of the 5th finger nail, hypertrichosis, sparse scalp hair and aggressive behavior for SMARCE1 [21], truncal obesity and short stature for LAS1L [16], myoclonic atonic seizures for SLC6A1 [15], aggressive behavior for SYNGAP1 [17], dysmorphic features and dental anomalies for ASXL3 [14] and aggressive behavior and dental anomalies for SATB2 [19] (Fig 1).

Table 2. Characteristics of AS-like patients at clinical re-evaluation.

| Patient | Gender | Age at molecular diagnosis (years) | Consistent features present in 100% of patients with AS | Frequent features present in more than 80% of AS affected individuals | Associated features present in 20–80% of AS affected individuals | Additional clinical features | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe developmental delay | Speech impairment | Ataxia or unsteady gait | Apparent happy demeanor/Stereotypies | Microcephaly | Seizures | Abnormal EEG | |||||

| 1 | M | 14 | + | + (5–10 words) | + | +/+ | - | + | + | Sleep disorder, hypotonia | Congenital torticolis, bruxism, aggressive behavior |

| 2 | F | 19 | + | + (less than 5 words) | - | +/+ | - | + | + | Sleep disorder, feeding problems, kyphoscoliosis | Aggressive behavior |

| 3 | F | 12 | + | + (Absent speech) | + | -/+ | - | + | + | Hypotonia | Aggressive behavior |

| 4 | F | 9 | + | + (Absent speech) | + | +/+ | + (Relative) | - | + | Hypotonia, feeding problems | - |

| 5 | F | 20 | + | + (5–10 words) | + | +/- | - | - | + | - | Dental anomalies, auto and hetero-aggressive behavior |

| 6 | F | 18 | + | + (Absent speech) | - | +/- | + (Relative) | + | - | Scoliosis | - |

| 7 | M | 15 | + | + (less than 5 words) | + | +/+ | - | + | + | Feeding problems, wide mouth, hypotonia | Sparse scalp hair, hypertricosis in the back and hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, hypoplasic 5th fingernail, auto and hetero-aggressive behavior |

| 8 | F | 14 | + | + (More than 20 words) | + | +/- | + | - | - | Hypotonia | Cerebellar atrophy |

| 9 | M | 38 | + | + (Absent speech) | + | +/+ | + (Relative) | + | + | Hypotonia, feeding problems (esophageal reflux), sleep disorder | Dental anomalies, bruxism, episodic hyperventilation |

| 10 | M | 7 | + | + (less than 5 words) | - | +/- | + (Relative) | - | - | Wide spaced teeth, brachycephaly | Truncal obesity, short stature |

| 11 | F | 14 | + | + (less than 5 words) | - | +/+ | + (Relative) | + | - | Feeding problems (dysphagia) | - |

| 12 | M | 24 | + | + (5–10 words) | - | +/+ | + | + | NA | Strabismus, sleep disorder, kyphoscoliosis | Hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, abnormal behavior, hypothyroidism, bruxism |

| 13 | M | 9 | + | + (Absent speech) | + | +/+ | + (Relative) | + | - | Sleep disorder, hypotonia | Episodic hyperventilation, mild subcortical atrophy |

| 14 | M | 13 | + | + (Absent speech) | + | +/+ | - | + | + | Sleep disorder, wide-spaced teeth | Myoclonic atonic seizures, bruxism |

M, Male; F, Female; +, present; -, not present; NA, non-available data.

Fig 1. Schematic representation of the phenotypic overlap between the patients with pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants genes and the AS phenotype.

In the middle of the figure the core AS features present in all the patients while in the tips the clinical features present in the patients that are associated with the gene identified.

However, not all patients presented all the clinical features associated with the genes identified. Unsteady gait and hypotonia were not present in patient carrying the pathogenic variant in SYNGAP1 [17]. The patient harboring a pathogenic variant in SATB2 did not show sialorrhea and feeding difficulties [19]. Finally, the ataxia of gait, stereotypies and hypotonia were not observed in the patient with a pathogenic variant in KCNQ3 [20].

A novel candidate variant was identified in a gene not previously associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. The identified variant is a de novo frameshift deletion c.456_459delTGAG (NM_004506.3), p.(Ser152Argfs*40) in HSF2 gene in patient 12. The variant has not been reported before and is not present in the gnomAD database (version 2.1.1).

UBE3A has been shown to have both nuclear and cellular functions mainly through its ubiquitin protein-ligase activity [28]. UBE3A interacts with most of the components of the proteasome [29] regulating the activity of signal transduction pathways such as Wnt signaling that regulates central nervous system development [30–32] and synaptic plasticity in both excitatory and inhibitory GABAergic axon terminals [33–36]. At the nucleus, UBE3A has been shown to regulate chromatin structure, DNA methylation and transcriptional regulation [37–40]. Interestingly, 8 out of the 10 genes found mutated in this study are mainly involved in synapsis (VAMP2, SYNGAP1, SLC6A1 and KCNQ3) [41–44] and chromatin remodeling or transcription regulation (TBL1XR1, SATB2, SMARCE1 and ASXL3) [45–48].

Discussion

We identified causal variants in 11 out of 14 patients with an AS-like phenotype. The global yield diagnostic of WES in this is study is 78,5%, which is higher to what has been reported in the literature for other neurodevelopmental disorders (24–68%) [49]. The results of WES led to the identification of 10 new genes that cause an AS-like phenotype (SYNGAP1, VAMP2, TBL1XR1, ASXL3, SATB2, SMARCE1, SPTAN1, KCNQ3, SLC6A1 and LAS1L), all of them previously associated with other neurodevelopmental disorders. In addition, we propose HSF2 (Heat Shock Factor) as a new candidate gene for the AS-like phenotype. Although HSF2 has not been previously associated with any human disease, the gene is highly expressed in the brain (Data source: GTEx Analysis Release V8, dbGaP Accession phs000424.v8.p2 [50]) and is highly intolerant to loss of function variation (pLI 0.92). Quantification of the mutated allele in mRNA showed a reduction in the allele carrying the frameshift variant (S1A Fig), suggesting the activation of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) machinery [51] and supporting a loss of function mechanism of disease for the HSF2 gene. Expression analysis of HSF2 in blood mRNA also showed a reduction in HSF2 expression in the patient compared to control (p-value 0.014) (S1B Fig). However, other tissues should be examined to clearly demonstrate the activation of NMD and a loss of function mechanism for the HSF2 variant.

Furthermore, HSF2 knockout mice show defects in the development of the central nervous system and spermatogenesis [52,53]. The identification of additional patients with loss of function variants in HSF2 and functional studies in neural cells will contribute to elucidate the role of HSF2 in the AS-like phenotype.

De novo variants have been described to account for approximately half of the genetic architecture of severe developmental disorders [54]. In our cohort, 10 of the 11 pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants were de novo, accounting for 90% of diagnosis and highlighting the power of using trio-WES for the molecular diagnosis of severe developmental disorders. Only in one case, the X-linked variant in LAS1L was inherited from the mother, who was a healthy carrier (data not shown).

All patients had received a suspected clinical diagnosis of AS. In the majority of our patients (12/14) the initial diagnosis was done during infancy or early childhood (before five years old). At the time of initial diagnosis, all of them presented severe global DD and speech impairment in addition to the characteristic happy disposition. Clinical re-evaluation at the time of molecular diagnosis confirmed the clinical diagnosis of AS (Table 2). In addition, other clinical features manifested during growth were then associated with the new identified genes. Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in VAMP2, KCNQ3, SMARCE1, SATB2, SYNGAP1, SLC6A1, ASXL3, SPTAN1, TBL1XR1 and LAS1L genes are associated with neurodevelopment disorders that overlap with AS and whose features have been defined in the last years [6,13–19,21]. Finally, not all patients presented all the clinical features associated with the genes identified. This clinical variability, possibly due to the different pathogenicity strength of the genetic variants, differences in genetic background and to non-genetic environmental factors, makes the clinical diagnosis challenging.

Lack of molecular diagnosis in 10–15% of clinically diagnosed AS patients has been used to define the AS-like group. Our trio based WES approach demonstrates that the majority of these patients (78,5%) are carriers of pathogenic variants in genes involved in neurodevelopmental disorders whose features overlap with AS (Fig 1), highlighting the wide genetic heterogeneity in AS-like patients and expanding the differential diagnosis. Likewise, other studies have recently described new genes associated with Angelman-like phenotypes such as HIVEP2 [55] or UNC80 [56].

TBL1XR1, SATB2, SMARCE1 and ASXL3 are known transcriptional regulators acting through chromatin modification [46,57,58]. UBE3A has been shown to be present in euchromatin-rich nuclear domains indicating that it may influence neuronal physiology by regulating chromatin and gene transcription [59]. RNA-seq studies of UBE3A loss in rat cortex, mice hippocampus and SH-SY5Y cells have shown differential gene expression of KCNQ3 [60], SMARCE1, HSF2 [38], SPTAN1 and SATB2 [39] suggesting that these genes may be transcriptionally regulated by UBE3A. Moreover, UBE3A gain and loss in human SH-SY5Y cells has been shown to have significant effects on DNA methylation and chromatin modification in genes involved in transcriptional regulation and brain development including SATB2, ASXL3, SMARCE1 and TBL1XR1 [38]. Overall, these evidences suggest common deregulated pathways between new identified Angelman-like genes and UBE3A. In addition, UBE3A has been shown to localize in axon terminals suggesting it locally regulates individual synapses. Five of the genes identified here, VAMP2, SYNGAP1, SLC6A1 and KCNQ3 are known to be involved in synapse function suggesting they may be regulated by UBE3A, as has already been demonstrated for KCNQ3 [60].

Except for the SYNGAP1 gene, none of the genes identified here have been previously described in the differential diagnosis of AS [61]. We propose the genes identified in this study should be included in the AS differential diagnosis and that trio WES should be considered as first line approach for the molecular diagnosis of AS-like patients. A high rate of diagnosis is essential since it contributes to more appropriate clinical patient surveillance as well as family genetic counseling.

Supporting information

A) Sanger sequencing of a fragment encompassing variant c.456_459delTGAG from patient 12 and a control sample shows a reduction in the percentage of the allele with the variant in the cDNA compared to DNA. The sequence corresponds to the reverse strand. B) qPCR analysis of HSF2 gene expression in patient 12 and a control sample normalized to GAPDH shows less HSF2 expression in patient 12 (* p-value 0.014).

(TIF)

Prob. DA, Probably Damaging; Pos. DA, Possibly Damaging; D, Deleterious; M, Medium; H, High; NA, Not Available.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and families for their participation in this study.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work is supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (MG, PI16/01411), Asociación Española de Síndrome de Angelman (EG), Institut d’investigació i innovació Parc Taulí I3PT (CA, CIR2016/025, CIR2018/021) and Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (XD, SAF2016-14 80255-R). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Williams C, Beaudet AL, Clayton-Smith J, Knoll JH, Kyllerman M, Laan LA, et al. Angelman Syndrome 2005: Updated Consensus for Diagnostic Criteria Charles. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2006;140: 413–418. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beygo J, Buiting K, Ramsden SC, Ellis R, Clayton-Smith J, Kanber D. Update of the EMQN/ACGS best practice guidelines for molecular analysis of Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27: 1326–1340. doi: 10.1038/s41431-019-0435-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan WH, Bird LM, Thibert RL, Williams CA. If not Angelman, what is it? A review of Angelman-like syndromes. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2014;164: 975–992. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luk H-M. Angelman-Like Syndrome: A Genetic Approach to Diagnosis with Illustrative Cases. Case Rep Genet. 2016;2016: 1–6. doi: 10.1155/2016/9790169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harlalka G V, Baple EL, Cross H, Kuhnle S, Cubillos-Rojas M, Matentzoglu K, et al. Mutation of HERC2 causes developmental delay with Angelman-like features. J Med Genet. 2013;50: 65–73. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salpietro V, Malintan NT, Llano-Rivas I, Spaeth CG, Efthymiou S, Striano P, et al. Mutations in the Neuronal Vesicular SNARE VAMP2 Affect Synaptic Membrane Fusion and Impair Human Neurodevelopment. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104: 721–730. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26: 589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, Poplin R, Del Angel G, Levy-Moonshine A, et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinforma. 2013;43: 11.10.1–33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38: e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desmet F-O, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod-Beroud G, Claustres M, Beroud C. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37: e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17: 405–423. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, Brown GR, Chao C, Chitipiralla S, et al. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46: D1062–D1067. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Syrbe S, Harms FL, Parrini E, Montomoli M, Mutze U, Helbig KL, et al. Delineating SPTAN1 associated phenotypes: from isolated epilepsy to encephalopathy with progressive brain atrophy. Brain. 2017;140: 2322–2336. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balasubramanian M, Willoughby J, Fry AE, Weber A, Firth H V, Deshpande C, et al. Delineating the phenotypic spectrum of Bainbridge-Ropers syndrome: 12 new patients with de novo, heterozygous, loss-of-function mutations in ASXL3 and review of published literature. J Med Genet. 2017;54: 537–543. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johannesen KM, Gardella E, Linnankivi T, Courage C, Martin A de Saint, Lehesjoki A-E, et al. Defining the phenotypic spectrum of SLC6A1 mutations. Epilepsia. 2018;59: 389–402. doi: 10.1111/epi.13986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu H, Haas S, Chelly J, Esch H Van, Raynaud M, Brouwer A de, et al. X-exome sequencing of 405 unresolved families identifies seven novel intellectual disability genes. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;21: 133–148. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mignot C, von Stulpnagel C, Nava C, Ville D, Sanlaville D, Lesca G, et al. Genetic and neurodevelopmental spectrum of SYNGAP1-associated intellectual disability and epilepsy. J Med Genet. 2016;53: 511–522. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laskowski RA, Thornton JM, Tyagi N, Johnson D, McWilliam C, Kinning E, et al. Integrating population variation and protein structural analysis to improve clinical interpretation of missense variation: application to the WD40 domain. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25: 927–935. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zarate YA, Smith-Hicks CL, Greene C, Abbott MA, Siu VM, Calhoun ARUL, et al. Natural history and genotype-phenotype correlations in 72 individuals with SATB2-associated syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2018;176: 925–935. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sands TT, Miceli F, Lesca G, Beck AE, Sadleir LG, Arrington DK, et al. Autism and developmental disability caused by KCNQ3 gain-of-function variants. Ann Neurol. 2019. doi: 10.1002/ana.25522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zarate YA, Bhoj E, Kaylor J, Li D, Tsurusaki Y, Miyake N, et al. SMARCE1, a rare cause of Coffin–Siris Syndrome: Clinical description of three additional cases. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2016;170: 1967–1973. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Firth H V, Richards SM, Bevan AP, Clayton S, Corpas M, Rajan D, et al. DECIPHER: Database of Chromosomal Imbalance and Phenotype in Humans Using Ensembl Resources. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84: 524–533. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miceli F, Soldovieri MV, Ambrosino P, Maria M De, Migliore M, Migliore Xr, et al. Early-Onset Epileptic Encephalopathy Caused by Gain-of-Function Mutations in the Voltage Sensor of Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 Potassium Channel Subunits. J Neurosci. 2015;35: 3782–3793. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4423-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aguilera C, Gabau E, Laurie S, Baena N, Derdak S, Capdevila N, et al. Identification of a de novo splicing variant in the Coffin-Siris gene, SMARCE1, in a patient with Angelman-like syndrome. Mol Genet genomic Med. 2019;7: e00511. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuechler A, Czeschik JC, Graf E, Grasshoff U, Huffmeier U, Busa T, et al. Bainbridge-Ropers syndrome caused by loss-of-function variants in ASXL3: a recognizable condition. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25: 183–191. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carvill GL, McMahon JM, Schneider A, Zemel M, Myers CT, Saykally J, et al. Mutations in the GABA Transporter SLC6A1 Cause Epilepsy with Myoclonic-Atonic Seizures. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96: 808–815. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell L, Wittkowski A, Hare DJ. Movement Disorders and Syndromic Autism: A Systematic Review. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49: 54–67. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3658-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang L, Kinnucan E, Wang G, Beaudenon S, Howley PM, Huibregtse JM, et al. Structure of an E6AP-UbcH7 complex: insights into ubiquitination by the E2-E3 enzyme cascade. Science. 1999;286: 1321–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez-Noel G, Luck K, Kuhnle S, Desbuleux A, Szajner P, Galligan JT, et al. Network Analysis of UBE3A/E6AP-Associated Proteins Provides Connections to Several Distinct Cellular Processes. J Mol Biol. 2018;430: 1024–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kléber M, Sommer L. Wnt signaling and the regulation of stem cell function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16: 681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lie D-C, Colamarino SA, Song H-J, Désiré L, Mira H, Consiglio A, et al. Wnt signalling regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nature. 2005;437: 1370–1375. doi: 10.1038/nature04108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuwabara T, Hsieh J, Muotri A, Yeo G, Warashina M, Lie DC, et al. Wnt-mediated activation of NeuroD1 and retro-elements during adult neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12: 1097–1105. doi: 10.1038/nn.2360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun AX, Yuan Q, Tan S, Xiao Y, Wang D, Khoo ATT, et al. Direct Induction and Functional Maturation of Forebrain GABAergic Neurons from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 2016;16: 1942–1953. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace ML, Burette AC, Weinberg RJ, Philpot BD. Maternal Loss of Ube3a Produces an Excitatory/Inhibitory Imbalance through Neuron Type-Specific Synaptic Defects. Neuron. 2012;74: 793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Margolis SS, Salogiannis J, Lipton DM, Mandel-Brehm C, Wills ZP, Mardinly AR, et al. EphB-Mediated Degradation of the RhoA GEF Ephexin5 Relieves a Developmental Brake on Excitatory Synapse Formation. Cell. 2010;143: 442–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kühnle S, Mothes B, Matentzoglu K, Scheffner M. Role of the ubiquitin ligase E6AP/UBE3A in controlling levels of the synaptic protein Arc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110: 8888–8893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302792110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaaroor-Regev D, de Bie P, Scheffner M, Noy T, Shemer R, Heled M, et al. Regulation of the polycomb protein Ring1B by self-ubiquitination or by E6-AP may have implications to the pathogenesis of Angelman syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107: 6788–6793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003108107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopez SJ, Dunaway K, Islam MS, Mordaunt C, Vogel Ciernia A, Meguro-Horike M, et al. UBE3A-mediated regulation of imprinted genes and epigenome-wide marks in human neurons. Epigenetics. 2017/11/06. 2017;12: 982–990. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2017.1376151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopez SJ, Laufer BI, Beitnere U, Berg EL, Silverman JL, O’Geen H, et al. Imprinting effects of UBE3A loss on synaptic gene networks and Wnt signaling pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2019;28: 3842–3852. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El Hokayem J, Weeber E, Nawaz Z. Loss of Angelman Syndrome Protein E6AP Disrupts a Novel Antagonistic Estrogen-Retinoic Acid Transcriptional Crosstalk in Neurons. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55: 7187–7200. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-0871-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Südhof TC, Rothman JE. Membrane fusion: grappling with SNARE and SM proteins. Science. 2009;323: 474–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1161748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clement JP, Aceti M, Creson TK, Ozkan ED, Shi Y, Reish NJ, et al. Pathogenic SYNGAP1 mutations impair cognitive development by disrupting maturation of dendritic spine synapses. Cell. 2012;151: 709–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mermer F, Poliquin S, Rigsby K, Rastogi A, Shen W, Romero-Morales A, et al. Common molecular mechanisms of SLC6A1 variant-mediated neurodevelopmental disorders in astrocytes and neurons. Brain. 2021;144: 2499–2512. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baculis BC, Zhang J, Chung HJ. The Role of Kv7 Channels in Neural Plasticity and Behavior. Front Physiol. 2020;11: 1206. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.568667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li JY, Daniels G, Wang J, Zhang X. TBL1XR1 in physiological and pathological states. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2015;3: 13–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gyorgy AB, Szemes M, de Juan Romero C, Tarabykin V, Agoston D V. SATB2 interacts with chromatin-remodeling molecules in differentiating cortical neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27: 865–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06061.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lomeli H, Castillo-Robles J. The developmental and pathogenic roles of BAF57, a special subunit of the BAF chromatin-remodeling complex. FEBS Lett. 2016;590: 1555–1569. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Functional Katoh M. and cancer genomics of ASXL family members. Br J Cancer. 2013;109: 299–306. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clark MM, Stark Z, Farnaes L, Tan TY, White SM, Dimmock D, et al. Meta-analysis of the diagnostic and clinical utility of genome and exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in children with suspected genetic diseases. npj Genomic Med. 2018;3: 1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41525-018-0053-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Consortium GTEx. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science (80-). 2020;369: 1318 LP– 1330. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lykke-Andersen S, Jensen TH. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: an intricate machinery that shapes transcriptomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16: 665–677. doi: 10.1038/nrm4063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang G, Zhang J, Moskophidis D, Mivechi NF. Targeted disruption of the heat shock transcription factor (hsf)-2 gene results in increased embryonic lethality, neuronal defects, and reduced spermatogenesis. Genesis. 2003;36: 48–61. doi: 10.1002/gene.10200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kallio M, Chang Y, Manuel M, Alastalo T-P, Rallu M, Gitton Y, et al. Brain abnormalities, defective meiotic chromosome synapsis and female subfertility in HSF2 null mice. EMBO J. 2002;21: 2591–2601. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McRae J, Clayton S, Fitzgerald T, Kaplanis J, Prigmore E, Rajan D, et al. Prevalence and architecture of de novo mutations in developmental disorders. Nature. 2017;542: 433–438. doi: 10.1038/nature21062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goldsmith H, Wells A, Sá MJN, Williams M, Heussler H, Buckman M, et al. Expanding the phenotype of intellectual disability caused by HIVEP2 variants. Am J Med Genet A. 2019;179: 1872–1877. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He Y, Ji X, Yan H, Ye X, Liu Y, Wei W, et al. Biallelic UNC80 mutations caused infantile hypotonia with psychomotor retardation and characteristic facies 2 in two Chinese patients with variable phenotypes. Gene. 2018;660: 13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.03.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Srivastava A, Ritesh KC, Tsan Y-C, Liao R, Su F, Cao X, et al. De novo dominant ASXL3 mutations alter H2A deubiquitination and transcription in Bainbridge-Ropers syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25: 597–608. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoon H-G, Choi Y, Cole PA, Wong J. Reading and function of a histone code involved in targeting corepressor complexes for repression. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25: 324–335. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.324-335.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burette AC, Judson MC, Burette S, Phend KD, Philpot BD, Weinberg RJ. Subcellular organization of UBE3A in neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2017;525: 233–251. doi: 10.1002/cne.24063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Panov J, Kaphzan H. Bioinformatics analyses show dysregulation of calcium-related genes in Angelman syndrome mouse model. Neurobiol Dis. 2021;148: 105180. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parker MJ, Magee AC, Maystadt I, Benoit V, study D, FitzPatrick DR, et al. De novo, heterozygous, loss-of-function mutations in SYNGAP1 cause a syndromic form of intellectual disability. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2015;167: 2231–2237. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A) Sanger sequencing of a fragment encompassing variant c.456_459delTGAG from patient 12 and a control sample shows a reduction in the percentage of the allele with the variant in the cDNA compared to DNA. The sequence corresponds to the reverse strand. B) qPCR analysis of HSF2 gene expression in patient 12 and a control sample normalized to GAPDH shows less HSF2 expression in patient 12 (* p-value 0.014).

(TIF)

Prob. DA, Probably Damaging; Pos. DA, Possibly Damaging; D, Deleterious; M, Medium; H, High; NA, Not Available.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.