Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the diffusion properties in the kidneys affected by renal artery stenosis (RAS) using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI).

Methods:

In this prospective study, 35 patients with RAS and 15 patients without renal abnormalities were enrolled and examined using DTI. Cortical and medullary regions of interest (ROIs) were located to obtain the corresponding values of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and fractional anisotropy (FA). The cortical and medullary ADC and FA were compared in the kidney affected by variable degrees of stenosis (RAS 50–75% and >75%) vs controls, using the one-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test. The Spearman correlation test was used to correlate the mean ADC and FA values in the cortex and medulla with the estimate glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

Results:

For the controls, the ADC value was significantly (p = 0.03) higher in the cortex than in the medulla; the FA value was significantly (p = 0.001) higher in the medulla than in the cortex. Compared with the controls, a significant reduction in the cortical ADC was present with a RAS of 50–75% and >75% (p = 0.001 and 0.041, respectively); a significant reduction in the medullary FA was verified only for RAS >75% (p = 0.023). The Spearman correlation test did not show a statistically significant correlation between the cortical and medullary ADC and FA, and the eGFR.

Conclusion:

The alterations of the diffusional parameters caused by RAS can be detected by DTI and could be useful in the diagnostic evaluation of these patients.

Advances in knowledge:

1. Magnetic resonance DTI could provide useful information about renal involvement in RAS.

2. Magnetic resonance DTI allows non-invasive repeatable evaluation of the renal parenchyma, without contrast media.

Introduction

Renal artery stenosis (RAS) is caused by atherosclerotic disease in 90% of cases and by fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) in 10%1; previous population-based studies have found significant RAS in 6–7% of patients with hypertension.2,3

This vascular lesion leads to a reduction of the blood flow to the kidney, resulting in renovascular hypertension and ischemic nephropathy1: a hemodynamically significant vascular disease produces global hypoperfusion of the kidney leading to altered endothelial and epithelial factors as well as to activation of the renin-angiotensin system; this causes subsequent vasoconstriction with oxidative injury ultimately leading to atrophy and fibrosis.4

Revascularization using percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTRA) seems to control hypertension and improve renal function in FMD and RAS following arteritis while its usefulness in atherosclerotic RAS is still controversial.5

Doppler ultrasonography, computed tomographic angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) represent non-invasive imaging methods allowing the accurate detection and grading of RAS; unfortunately, these methods do not provide detailed information regarding parenchymal involvement.1

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) allows us to study water molecule diffusion and provides information regarding the renal microstructure by calculating the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC).6,7 Previous studies have found alterations in the ADC correlated to significant RAS.8 Other studies have demonstrated that the diffusion process in the kidney occurs in an anisotropic manner due to its complex organization.9–16 Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), therefore, is the most appropriate functional technique for assessing diffusion properties in the kidney by calculating the ADC (expressing global diffusion) and fractional anisotropy (FA) (measuring the directionality of this diffusion). DTI demonstrates clear anisotropy in the renal medulla and decreasing diffusion anisotropy is observed in diabetic nephropathy,13 allograft dysfunction,14 ischemia-reperfusion damage,15 and chronic parenchymal disease.16

To our knowledge, studies regarding the use of DTI in RAS are very limited in the literature.12

Thus, the aims of our study were: (a) to prospectively evaluate the feasibility of DTI in investigating renal diffusion properties in patients with RAS; (b) to analyze the changes in the ADC and FA values as compared to patients with normal renal function, attempting to identify useful parameters for the evaluating renal damage.

Methods and materials

Study population

This prospective study was approved by the institutional review board in accordance with institutional guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were notified of the investigational nature of this study and gave their written informed consent.

The patients were consecutively enrolled according to the following inclusion criteria: a) were admitted to the Nephrology Unit of AOU of Bologna; b) had ≥18 years old; c) had multidrug resistant hypertension; d) were suspected of having RAS based on clinical history, physical examination results, and Doppler ultrasound findings; e) required MRA as part of the routine clinical protocol, and f) have an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥30 mL/min.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: a) arteritis, primary hypertension and other known kidney diseases (such as glomerulonephritis); b) previous PTRA with or without stenting for RAS; c) any contraindications to performing the MRI.

Finally, 35 patients (22 males; mean age ± standard deviation, 57 ± 11 years; median age 57 years; range 35–77 years) were enrolled and constituted the study group. The patients’ clinical characteristics included a history of smoking (n = 19), elevated cholesterol level (n = 10), and a family history of hypertension or coronary artery disease (n = 18).

For comparison, 15 patients (nine males; mean age ± standard deviation, 54 ± 11 years; median age 35 years; range 35–76 years) who had no history of renal disease, hypertension, diabetes or other vascular diseases and had undergone MRI of the upper abdomen for clinical reasons other than kidney disease, constituted the control group (necessary for the measurement of reference values); in these patients, color Doppler was used to excluding RAS.

According to the diagnostic protocol of our Nephrology Unit, once admitted to the unit, all patients of the study group underwent blood sampling within a week of the MRI. For each patient, serum creatinine and the eGFR (calculated according to the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease – MDRD – formula)17,18 were recorded. For the patients in the control group, the same laboratory data were extracted from the central database of AOU of Bologna, as it was only necessary to verify that the patients had a normal renal function. Only patients who had previously undergone laboratory testing not more than a month before were considered.

MRI protocol

The MRI examinations were performed with a 1.5T whole-body scanner (Signa HDxt; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) and a standard 8-channel phased-array body coil.

All patients, fasting for at least 6 h and normally hydrated, without any diuretic drugs before the exam, underwent MRI in a supine position.

The standard protocol for all study group patients included an axial respiratory-triggered single-shot fast spin echo (SSFSE) T2 weighted sequence, an axial breath-hold fast-spoiled gradient (FSPGR) T1 weighted sequence (double acquisition in/out of phase), and a coronal two-dimensional respiratory-triggered fast imaging technique employing steady-state acquisition (FIESTA) sequence. In all the study group patients, the contrast-enhanced MRA (CE-MRA) was added in order to study the vasculature with contrast media using a breath-hold, three-dimensional time of flight (TOF) fast-spoiled gradient (FSPGR) sequence in the coronal plane with an anatomical range covering both kidneys and the aorta, during intravenous injection of a contrast bolus of 0.1 mmol per kilogram of body weight of Gadobutrol (Gd-DTPA) (Gadovist®, Bayer Schering Pharma, Germany) at a flow rate of 2 ml/s, followed by 20 ml of saline solution. The parameters for the CE-MRA were the following: TE 1.4–1.7 ms, TR 4–5 ms, flip angle 35°, TI 14 ms, receiver bandwidth 62.5 Hz/pixel, field of view (FOV) 400 mm, slice thickness 3.6 mm, locations per slab 40, frequency matrix 256, phase matrix 224, number of excitations 0.5, phase FOV 1, and an acquisition time of 15–16 s.

In all the control group patients, standard MRI protocol, according to the patient’s specific clinical needs, was carried out.

The DTI acquisition was added to the routine clinical protocol in all individuals of both groups after anatomical imaging and before the injection of contrast medium (when contrast medium was used), in the axial plane with breath-hold, using a spin echo single-shot echoplanar imaging (SSEPI) sequence, with six diffusion-encoding gradient directions, two b-values (0 and 500 s/mm2) and the following parameters: TE 82 ms, TR 3000 ms, FOV 400 × 400 mm, slice thickness 6 mm, intersection gap 0.5 mm, matrix size 128 × 128, number of excitations one and number of slices 14, for a total imaging time of 24 s.

An axial respiratory-triggered single-shot fast spin echo (SSFSE) T2 weighted sequence was acquired matching the DTI sequence slice positions.

Analysis of the DTI data was carried out offline at a separate workstation, using commercially available software (Functool, 4.5.5, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI).

The quantitative ADC maps were calculated based on a monoexponential fitting model. Fractional anisotropy was calculated and depicted in a quantitative parametric map (FA map).

Image analysis

All data were evaluated in consensus by two radiologists, with 10 and 15 years of experience in the renal MRI, to reduce measurement error, on an independent workstation. Any discrepancies during image analysis were resolved by consensus discussion between the two investigators.

The analysis included: 1) an assessment of the vasculature by analyzing the CE-MRA data set and, 2) a functional evaluation of the kidneys by analyzing the DTI acquisition data.

The assessment of the renal arteries was carried out as reported in a previous study.19 In their analysis, the readers noted the number of renal arteries on both sides; the arteries entering the renal hilum were considered as the main renal arteries. The presence or absence of accessory renal arteries were also assessed, and the same evaluation regarding the possible presence of stenosis was attempted. For each renal artery, stenosis grading was carried out by measuring the minimal luminal diameter with an electronic caliper. The percentage of stenosis was calculated using the following formula: [1 – (L/R)]×100, where L was the diameter of the lesion and R was the diameter of the reference site; the latter was defined as the normal-looking portion of the stenotic vessel distal to the lesion. The extent of the RAS was then graded as follows: Grade 1 indicated less than 20% luminal narrowing, Grade 2, 20–49% luminal narrowing, Grade 3, 50–74% luminal narrowing, Grade 4, 75–99% luminal narrowing and Grade 5, occlusion.

For the study group, the analysis was conducted per-kidney. As reported in the literature, RAS ≥50% (Grade 3–5) was considered hemodynamically significant; thus, kidneys with RAS ≥50% constituted the study group. However, hemodynamic studies have shown that more severe stenosis, at least of 75%, could produce significant flow alterations. Therefore, based on the stenosis grade, two subgroups were identified: subgroup A, with a stenosis grade between 50 and 75% (Grade 3), and subgroup B, with a stenosis grade greater than 75% (Grade 4–5).

The functional evaluation was carried out as reported in a previous study16; all the DTI images were reviewed by the two readers to judge whether the MRI quality was good enough to measure the FA and ADC values. The absence of artifacts on the anatomical and DTI images was evaluated and confirmed by the two readers. In all patients and for each kidney, an axial DTI b0 slice was selected in the middle portion of the kidney, at the level of the renal hilum, and three circular regions of interest (ROIs) (mean pixel size 50 mm2) were located in the cortex and the medulla respectively, carefully avoiding the renal vessels and the collecting system. The T2 weighted sequence coupled to the DTI b0 slice helped the correct placement of the ROIs in the cortex and medulla. For each ROI, the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the ADC (expressed in 10−3 mm2/s) and the FA (dimensionless parameter) values were calculated from the ADC and FA maps.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Excel 9.0 (Microsoft, Seattle, WA) and MedCalc 12.0 (Mariakerke, Belgium) software packages.

In each subject of the control and study groups, in all sites (cortex and medulla) and for each kidney, the mean values of the three ROIs for the ADC and FA were calculated.

For the control group, these values between left and right kidney were compared using the paired Student’s t-test; the mean values of the ADC and FA for the cortex and medulla between left and right kidney were calculated and considered the reference values.

The one-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test was carried out to assess the difference between the variables and the groups. The paired Student’s t-test was used to compare the mean values of the ADC and the FA for each ROI site in each group. The two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare the mean values of the ADC and the FA for each ROI site between the groups and subgroups. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Furthermore, a Spearman correlation test was used to correlate the mean ADC and the mean FA, in the cortex and medulla, with the eGFR.

Results

No artifacts were observed on the anatomical and DTI images of any of the patients in either group.

Control group

No parenchymal abnormalities were observed.

Table 1 shows the mean values and standard deviation of the ADC and the FA, in the cortex and the medulla, for both kidneys. The ADC value was significantly higher in the cortex than in the medulla; the FA value was significantly higher in the medulla than in the cortex (Figure 1). No significant difference was found between the left and the right kidneys.

Table 1.

Mean values and standard deviation of the ADC and FA of the left and right kidneys in the control group

| Cortex | Medulla | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADC (x 10−3 mm2/s) | |||

| Right kidney | 2.54 ± 0.07 | 2.29 ± 0.01 | 0.001 |

| Left kidney | 2.53 ± 0.02 | 2.18 ± 0.02 | 0.0002 |

| p | 0.89 | 0.17 | |

| FA | |||

| Right kidney | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Left kidney | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 0.38 ± 0.06 | <0.001 |

| p | 0.58 | 0.81 | |

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; FA, fractional anisotropy.

A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Diffusion tensor imaging analysis in a control group patient (eGFR of 105 mL/min). Circular ROIs were defined in the cortex and medulla on the ADC (A) and FA (B) maps of the right kidney, by using the T2 sequence for the correct placement (C): the corresponding values of the ADC were 2.54 and 2.23 × 10−3 mm2/s and the corresponding values of the FA were 0.26 and 0.40. ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FA, fractional anisotropy; ROIs, regions of interest.

The mean values between the left and the right kidneys useful as reference standard for cortical and medullary ADC (x 10−3 mm2/s) were 2.53 ± 0.16 and 2.21 ± 0.18 (p = 0.03) and for cortical and medullary FA were 0.31 ± 0.06 and 0.39 ± 0.06 (p = 0.001), respectively.

The mean value of the eGFR in the control group was 90 mL/min (range 75–105 mL/min).

Study group

Based on the CE-MRA findings, stenosis was identified in 23/35 patients, with a RAS ≥50% (Grade 3–5) in 22/35 (63%) patients which was bilateral in 9/35 (26%). In three patients, four accessory renal arteries without RAS were identified. Overall, 31 kidneys with hemodynamic RAS were evaluated: 13/31 (42%) were associated with a RAS 50–75% (Grade 3) and were included in subgroup A and 18/31 (58%) were associated with a RAS ≥75% (Grade 4–5) and were included in subgroup B.

The mean value of the eGFR in the study group was 50 mL/min (range 40–79 mL/min).

Comparison among groups

Table 2 shows the comparison between the control group and the study group. Significant reduction in the cortical ADC and in the medullary FA (p = 0.012 and 0.027, respectively) was found in the study group as compared with the control group (Figures 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Comparison between the control group, the study group, and subgroups A and B

| ADC (x 10−3 mm2/s) | FA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortex | Medulla | Cortex | Medulla | |

| Control group | 2.53 ± 0.16 | 2.21 ± 0.18 | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 0.39 ± 0.06 |

| Study group (RAS ≥50%) | 2.27 ± 0.17 | 2.15 ± 0.11 | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.05 |

| p | 0.012 | 0.21 | 0.881 | 0.027 |

| Subgroup A (RAS 50–75%) | 2.28 ± 0.11 | 2.21 ± 0.10 | 0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.32 ± 0.05 |

| p | 0.001 | 0.625 | 0.623 | 0.075 |

| Subgroup B (RAS >75%) | 2.27 ± 0.20 | 2.11 ± 0.11 | 0.30 ± 0.06 | 0.30 ± 0.05 |

| p | 0.041 | 0.134 | 0.888 | 0.023 |

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; FA, fractional anisotropy; RAS, renal artery stenosis.

A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

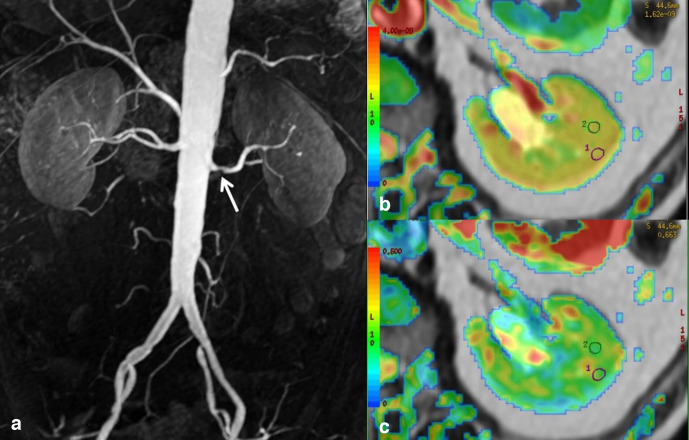

Figure 2.

A patient of subgroup A with an eGFR of 56 mL/min. (A) The contrast-enhanced Magnetic Resonance Angiography shows left RAS of 60% (white arrow). DTI analysis of the right kidney (not shown) did not find alterations of the diffusion parameters. On the left side, the ADC map (B) shows a significant reduction in the cortical ADC (2.29 × 10−3 mm2/s) as compared to the reference standard values; the medullary ADC was 2.46 × 10−3 mm2/s. The FA map (C) did not show significant alteration in the cortical and medullary FA (0.28 and 0.33, respectively). ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FA, fractional anisotropy; RAS, renal artery stenosis; ROIs, regions of interest.

Figure 3.

A patient of subgroup B with an eGFR of 40 mL/min. (A) The contrast-enhanced Magnetic Resonance Angiography shows bilateral RAS > 80% (white arrows). The DTI analysis shows a bilaterally significant reduction in the cortical ADC and the medullary FA calculated on the ADC and FA maps. Here, the DTI analysis of the right kidney is shown: on the ADC map (B) the ADC values were 2.24 (cortex) and 2.30 (medulla) x 10−3mm2/s; on the FA map (C), the FA values were 0.36 (cortex) and 0.20 (medulla). ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FA, fractional anisotropy; RAS, renal artery stenosis.

There was no significant difference in the medullary ADC and cortical FA values between the groups.

The comparison between the control group and subgroups A and B showed a persistent significant reduction in the cortical ADC (p = 0.001 and 0.041, respectively), but a significant reduction in the medullary FA was verified only for subgroup B (p = 0.023).

The comparison between the subgroups did not show significant differences for the same parameters.

The Spearman correlation test did not show a statistically significant correlation between the cortical and medullary ADC and FA, and the eGFR for the study group.

Discussion

The diffusion within the kidney is predominant because of its elevated blood flow and tubular water transport. Therefore, in addition to the classic Brownian movements of the water molecules, blood and tubular flows contribute to determining the high ADC values in the kidney as compared to other organs. These flows differ qualitatively and quantitatively in the cortex and in the medulla and, therefore, affect the ADC values differently; the blood perfusion is predominant in the cortex while tubular transport is prevalent in the medulla. However, the increased perfusion of the cortex as compared to the medulla explained the higher value of the cortical ADC in the healthy kidney. The application of DTI allowed analyzing even the anisotropy of the renal diffusion, which is the preferential direction of the diffusional movements, measured by FA. Several studies have shown that the FA is higher in the medulla than in the cortex due to the directionality of the diffusivity, mainly due to the tubular flow radially oriented towards the pelvis.9–16

Renal artery stenosis causes a reduction in the blood supply in the peripheral circulation of the affected kidney, leading to a reduction in perfusion and, therefore, in global diffusion phenomena in the renal parenchyma. An overall reduction in the ADC in kidneys affected by RAS was first described, in an animal study model by Muller et al,20 even for moderate stenosis, probably due to the influence of the blood flow on both perfusion and tubular transport. Thereafter, other authors8,21 noted a characteristic reduction in the cortical ADC in the kidney affected by RAS.

In the present study, the alterations of the diffusion parameters in different degrees of stenosis were analyzed; this represented a strategy to better understand the influence of the blood flow on the diffusional processes and, therefore, to investigate the usefulness of the ADC and FA as predictors of renal damage. In fact, our results showed that it is possible to detect a significant decrease in the cortical ADC in the presence of RAS ≥50%, confirming that the ADC is very sensitive to changes in perfusion, particularly in the cortex where blood perfusion is predominant, as stated above. Using DTI, the modifications in the cortical ADC are detectable, even for moderate stenosis of the renal artery.

Moreover, some studies22,23 in recent years have shown that renal anisotropy is also influenced by blood flow; decreased blood flow can cause a reduction in the medullary FA.

Therefore, it can be argued that blood flow and microstructure are the two main factors determining diffusional parameters, such as the ADC and FA; however, modifications of the blood flow can be reversible within certain limits whereas the microstructural changes can more frequently express an irreversible phenomenon. In fact, many different diseases, including RAS, can cause damage to the parenchyma with consequent fibrosis in the cortical and medullary sites. Fibrosis contributes to worsening alterations in perfusion and tubular molecular transport, with an additional consequent reduction in the ADC and FA. Since tubular transport phenomena are more represented at the medullary level, the medullary FA will be predominantly reduced.

Some authors24,25 have shown that parenchymal FA decreases in the advanced stages of the disease, probably when fibrosis phenomena altering the parenchymal microstructure occur. Recent studies13–15 have demonstrated the correlation between FA and renal histopathological damage (including fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and cellular infiltration); the mechanisms which act to decrease diffusion anisotropy, however, remain unclear. Tubular atrophy, collagen deposition related to interstitial fibrosis, and inflammatory cell infiltration are different factors that can contribute to the destruction of the parenchymal microstructure by altering the normal functional processes of the kidney.

Our results have also shown that a significant reduction in FA occurs in the renal medulla only for more severe stenosis (RAS >75%).

This result suggests some considerations based on the above observations. On the one hand, it can be seen that tubular transport is altered in the presence of the most severe blood supply reduction and, therefore, FA represents a more stable parameter than the ADC in this pathological condition. On the other hand, as previously stated, the FA changes due to a higher degree of stenosis probably reflect the occurrence of irreversible alterations in the renal parenchyma.

The limitations of our study included: 1) the lack of correlation between the DTI results and the histopathological findings detected by renal biopsy, in order to demonstrate the presence of fibrotic change in kidneys affected by RAS; 2) the lack of comparison of the DTI results before and after revascularization with percutaneous angioplasty in order to evaluate reversible changes in the diffusion parameters and 3) the group of kidneys with RAS was heterogeneous, with various times to diagnosis and volume alteration of the affected kidney.

In conclusion, this preliminary report established the capability of the DTI technique to detect the changes in the diffusion parameters due to the decreased blood flow within the kidney affected by RAS; in particular, the cortical ADC and medullary FA may vary according to the degree of the stenosis. As has already been described, FA is probably the most sensitive parameter for evaluating renal damage.

The combined use of these two parameters, for varying degrees of stenosis, can be potentially advantageous for prognosis and follow-up of patients affected by RAS.

Contributor Information

Caterina Gaudiano, Email: caterina.gaudiano@gmail.com.

Valeria Clementi, Email: valeria.clementi40@gmail.com.

Beniamino Corcioni, Email: beniamino.corcioni@aosp.bo.it.

Matteo Renzulli, Email: matteo.renzulli@aosp.bo.it.

Elena Mancini, Email: elena.mancini@aosp.bo.it.

Rita Golfieri, Email: rita.golfieri@unibo.it.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weber BR, Dieter RS. Renal artery stenosis: epidemiology and treatment. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2014; 7: 169–81. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S40175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowley JJ, Santos RM, Peter RH, Puma JA, Schwab SJ, Phillips HR, et al. Progression of renal artery stenosis in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. Am Heart J 1998; 136: 913–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(98)70138-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansen KJ, Edwards MS, Craven TE, Cherr GS, Jackson SA, Appel RG, et al. Prevalence of renovascular disease in the elderly: a population-based study. J Vasc Surg 2002; 36: 443–51. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.127351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Textor SC. Ischemic nephropathy: where are we now? J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15: 1974–82. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000133699.97353.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alderson HV, Ritchie JP, Kalra PA. Revascularization as a treatment to improve renal function. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2014; 7: 89–99. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S35633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenberger U, Thoeny HC, Binser T, Gugger M, Frey FJ, Boesch C, et al. Evaluation of renal allograft function early after transplantation with diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Eur Radiol 2010; 20: 1374–83. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1679-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thoeny HC, De Keyzer F, Oyen RH, Peeters RR. Diffusion-Weighted MR imaging of kidneys in healthy volunteers and patients with parenchymal diseases: initial experience. Radiology 2005; 235: 911–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2353040554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yildirim E, Kirbas I, Teksam M, Karadeli E, Gullu H, Ozer I. Diffusion-Weighted MR imaging of kidneys in renal artery stenosis. Eur J Radiol 2008; 65: 148–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kataoka M, Kido A, Yamamoto A, Nakamoto Y, Koyama T, Isoda H, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of kidneys with respiratory triggering: optimization of parameters to demonstrate anisotropic structures on fraction anisotropy maps. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009; 29: 736–44. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Notohamiprodjo M, Dietrich O, Horger W, Horng A, Helck AD, Herrmann KA, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) of the kidney at 3 Tesla–Feasibility, protocol evaluation and comparison to 1.5 tesla. Invest Radiol 2010; 45: 245–54. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181d83abc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaudiano C, Clementi V, Busato F, Corcioni B, Ferramosca E, Mandreoli M, et al. Renal diffusion tensor imaging: is it possible to define the tubular pathway? A case report. Magn Reson Imaging 2011; 29: 1030–3. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2011.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Notohamiprodjo M, Glaser C, Herrmann KA, Dietrich O, Attenberger UI, Reiser MF, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of the kidney with parallel imaging: initial clinical experience. Invest Radiol 2008; 43: 677–85. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31817d14e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu L, Sedor JR, Gulani V, Schelling JR, O'Brien A, Flask CA, et al. Use of diffusion tensor MRI to identify early changes in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Nephrol 2011; 34: 476–82. doi: 10.1159/000333044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hueper K, Gutberlet M, Rodt T, Gwinner W, Lehner F, Wacker F, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging and tractography for assessment of renal allograft dysfunction-initial results. Eur Radiol 2011; 21: 2427–33. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2189-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung JS, Fan SJ, Chow AM, Zhang J, Man K, Wu EX. Diffusion tensor imaging of renal ischemia reperfusion injury in an experimental model. NMR Biomed 2010; 23: 496–502. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaudiano C, Clementi V, Busato F, Corcioni B, Orrei MG, Ferramosca E, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging and tractography of the kidneys: assessment of chronic parenchymal diseases. Eur Radiol 2013; 23: 1678–85. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2749-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N. Roth D. a more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130: 461–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klee GG, Schryver PG, Saenger AK, Larson TS. Effects of analytic variations in creatinine measurements on the classification of renal disease using estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR. Clin Chem Lab Med 2007; 45: 737–41. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaudiano C, Busato F, Ferramosca E, Cecchelli C, Corcioni B, De Sanctis LB, et al. 3D FIESTA pulse sequence for assessing renal artery stenosis: is it a reliable application in unenhanced magnetic resonance angiography? Eur Radiol 2014; 24: 3042–50. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3330-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Müller MF, Prasad PV, Bimmler D, Kaiser A, Edelman RR. Functional imaging of the kidney by means of measurement of the apparent diffusion coefficient. Radiology 1994; 193: 711–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.193.3.7972811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Namimoto T, Yamashita Y, Mitsuzaki K, Nakayama Y, Tang Y, Takahashi M. Measurement of the apparent diffusion coefficient in diffuse renal disease by diffusion-weighted echo-planar MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 1999; 9: 832–7. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heusch P, Wittsack H-J, Kröpil P, Blondin D, Quentin M, Klasen J, et al. Impact of blood flow on diffusion coefficients of the human kidney: a time-resolved ECG-triggered diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI) study at 3T. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 37: 233–6. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Notohamiprodjo M, Chandarana H, Mikheev A, Rusinek H, Grinstead J, Feiweier T, et al. Combined intravoxel incoherent motion and diffusion tensor imaging of renal diffusion and flow anisotropy. Magn Reson Med 2015; 73: 1526–32. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Q, Ma Z, Wu J, Fang W. DTI for the assessment of disease stage in patients with glomerulonephritis--correlation with renal histology. Eur Radiol 2015; 25: 92–8. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3336-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Z, Xu Y, Zhang J, Zhen J, Wang R, Cai S, et al. Chronic kidney disease: pathological and functional assessment with diffusion tensor imaging at 3T Mr. Eur Radiol 2015; 25: 652–60. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3461-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]