Abstract

This study is aimed at exploring the possible mechanism of action of the Suanzaoren decoction (SZRD) in the treatment of Parkinson's disease with sleep disorder (PDSD) based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) was used to screen the bioactive components and targets of SZRD, and their targets were standardized using the UniProt platform. The disease targets of “Parkinson's disease (PD)” and “Sleep disorder (SD)” were collected by OMIM, GeneCards, and DisGeNET databases. Thereafter, the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed using the STRING platform and visualized by Cytoscape (3.7.2) software. Then, the DAVID platform was used to analyze the Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway. Cytoscape (3.7.2) software was also used to construct the network of the “herb-component-target-pathway.” The core active ingredients and core action targets of the drug were verified by molecular docking using AutoDock software. A total of 135 Chinese herbal components and 41 corresponding targets were predicted for the treatment of PDSD using SZRD. Fifteen important signaling pathways were screened, such as the cancer pathway, TNF signaling pathway, PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, HIF-1 signaling pathway, and Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. The results of molecular docking showed that the main active compounds could bind to the representative targets and exhibit good affinity. This study revealed that SZRD has the characteristics and advantages of “multicomponent, multitarget, and multipathway” in the treatment of PDSD; among these, the combination of the main active components of quercetin and kaempferol with the key targets of AKT1, IL6, MAPK1, TP53, and VEGFA may be one of the important mechanisms. This study provides a theoretical basis for further study of the material basis and molecular mechanism of SZRD in the treatment of PDSD.

1. Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disease in middle-aged and elderly individuals. Clinically, symptoms include classic motor symptoms—tremor, myotonia, bradykinesia, and postural imbalance—as well as nonmotor symptoms—sleep disorders, smell disorders, autonomic nervous dysfunction, and cognitive and mental disorders [1]. Sleep disorders (SD), the most common nonmotor symptoms of PD, seen in 60–90% of these patients, are one of the common nocturnal symptoms [2]. Treatment modalities of PD with sleep disorder (PDSD), used in clinical practice, include levodopa, dopamine receptor agonists, benzodiazepines, and melatonin [3–5]. However, long-term use of such drugs may enhance restless leg syndrome, periodic limb movements, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder symptoms [6]. Furthermore, melatonin had little effect on objective sleep parameters [7]. Suanzaoren decoction (SZRD), derived from JinKuiYaoLue, is composed of five traditional Chinese medicines: Semen ziziphi spinosae, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Rhizoma anemarrhenae, Poria cocos, and Rhizoma chuanxiong [8]. It has the effect of nourishing the blood, calming the mind, clearing away heat, and eliminating annoyance, mainly treating liver and blood deficiency and insomnia caused by heat deficiency [9–12]. PD belongs to the category of “fibrillation disease” in traditional Chinese medicine, and it is more common in the elderly [13]. Clinical evidence shows that SZRD has a remarkable curative effect on insomnia [14–16]. However, the mechanism of action of fibrillation disease merging with wakefulness is not clear. Therefore, with the systematic research methods of network pharmacology and molecular docking, the overall analysis of the “herb-component-target-pathway” was conducted in this study to explore the possible mechanism of SZRD in the treatment of PDSD and to provide new theoretical support for the clinical treatment of PDSD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Screening and Target Prediction of Active Components of SZRD

Application analysis platform and database system pharmacology of Chinese medicine (TCMSP, https://tcmspw.com/tcmsp.php) [17] were used to retrieve active ingredients of SZRD and predict the targets of active ingredients. We use pharmacodynamics to select active ingredients satisfying both oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 30% and drug − likeness (DL) ≥ 0.18 [18, 19]. TCMSP was used for the prediction of targets of active ingredients. At the same time, the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/) [20], which was set for human species, was used to standardize the drug target of each active ingredient.

2.2. Screening of Disease-Related Targets

The targets related to the PD and SD were obtained through retrieving the OMIM (https://omim.org/search/advanced/) [21], GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) [22], and DisGeNET database search (https://www.disgenet.org/) [23] using the keyword “Parkinson's diseases” or “Sleep disorder.”

2.3. Screening of Common Targets of Diseases and Drugs

The online Venny 2.1 mapping platform (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html) was used to map “Parkinson's diseases,” “Sleep disorder,” and “SZRD” targets and to get the intersection targets.

2.4. Common Target PPI Network Construction

The intersection targets were imported into the STRING database (https://string-db.org/cgi/input) [24]. A confidence, ≥0.4, was taken, and the free nodes were hidden to construct the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network. This PPI network was further processed by Cytoscape 3.7.2 software [25] to realize visualization and screen out the core targets.

2.5. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis

For the screened core targets, the DAVID data platform (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp) [26] was used for Gene Ontology (GO) functional annotations and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis. Select “Homo species” on the DAVID platform; further analyze the SZRD for PDSD-related biological processes (BP), cellular component (CC), molecular function (MF), and signal pathway; and use the bioinformatic online platform (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/) [27] to visualize the result analysis.

2.6. Constructing the “H-C-T-P” Network

Cytoscape 3.7.2 software was used to construct the network of “herb-component-target-pathway” (H-C-T-P). This “H-C-T-P” network together with the screened main active ingredients, core targets, and concentrated main signal pathways was used to systematically analyze the possible mechanism of SZRD in the treatment of PDSD.

2.7. Docking and Verification of Potential Active Ingredients with Core Target Molecules

The 2D structures of the potential active ingredients in SZRD were downloaded from the TCMSP database while the 3D structure of the PDSD docking targets (top 5 of degree in PPI network) treated by SZRD was downloaded from the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (PDB) database (https://www.rcsb.org/) [28]. They were imported to AutoDockTools [29] for hydrogenation, dehydration, and other pretreatments. Then, molecular docking of the receptor and ligand was conducted to analyze its binding activity. The docking results were visualized using the PyMol software [30].

3. Results

3.1. The Active Components and Effective Targets of SZRD

By searching the TCMSP database, 135 different active ingredients of SZRD were screened, including 9 in Semen ziziphi spinosae, 15 in Poria cocos, 15 in Rhizoma anemarrhenae, 7 in Rhizoma chuanxiong, and 92 in Glycyrrhiza glabra. The results showed that these different drugs contained common active ingredients, namely A, B, and C as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

SZRD shares chemical composition information table.

| Number | Mol ID | Molecule name | OB% | DL | Drug |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | MOL000359 | Sitosterol | 36.91 | 0.75 | Glycyrrhiza glabra, Rhizoma chuanxiong |

| B | MOL000211 | Mairin | 55.38 | 0.78 | Glycyrrhiza glabra, Semen ziziphi spinosae |

| C | MOL000422 | Kaempferol | 41.88 | 0.24 | Glycyrrhiza glabra, Rhizoma anemarrhenae |

Cytoscape 3.7.2 software was used to screen the active ingredients with a degree ≥ 20 in SZRD. As shown in Table 2, 17 major components, which include quercetin, kaempferol, vestitol, 7-methoxy-2-methyl isoflavone, naringenin, anhydroicaritin, formononetin, stigmasterol, licochalcone A, and isorhamnetin, were obtained using this software.

Table 2.

Chemical information sheet of major active ingredients.

| Number | Mol ID | Molecule name | OB% | DL | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC84 | MOL000098 | Quercetin | 46.43 | 0.28 | 127 |

| C | MOL000422 | Kaempferol | 41.88 | 0.24 | 104 |

| GC74 | MOL000500 | Vestitol | 74.66 | 0.21 | 33 |

| GC8 | MOL003896 | 7-Methoxy-2-methyl isoflavone | 42.56 | 0.20 | 30 |

| GC11 | MOL004328 | Naringenin | 58.29 | 0.21 | 29 |

| ZM2 | MOL004373 | Anhydroicaritin | 45.41 | 0.44 | 27 |

| GC9 | MOL000392 | Formononetin | 69.67 | 0.21 | 26 |

| ZM6 | MOL000449 | Stigmasterol | 43.48 | 0.76 | 24 |

| GC5 | MOL002565 | Medicarpin | 49.22 | 0.34 | 24 |

| GC63 | MOL000497 | Licochalcone a | 40.79 | 0.29 | 24 |

| GC41 | MOL004891 | Shinpterocarpin | 80.3 | 0.73 | 23 |

| GC65 | MOL004978 | 2-[(3R)-8,8-Dimethyl-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyrano[6,5-f] chromen-3-yl]-5-methoxyphenol | 36.21 | 0.52 | 23 |

| SZR1 | MOL001522 | (S)-Coclaurine | 42.35 | 0.24 | 22 |

| GC6 | MOL004980 | Isorhamnetin | 39.71 | 0.33 | 22 |

| GC76 | MOL005003 | Licoagrocarpin | 58.81 | 0.58 | 21 |

| GC25 | MOL004835 | Glypallichalcone | 61.60 | 0.19 | 20 |

| GC64 | MOL004974 | 3′-Methoxyglabridin | 46.16 | 0.57 | 20 |

GC: Glycyrrhiza glabra; C: common components of Glycyrrhiza glabra and Rhizoma anemarrhenae; ZM: Rhizoma anemarrhenae; SZR: Semen ziziphi spinosae.

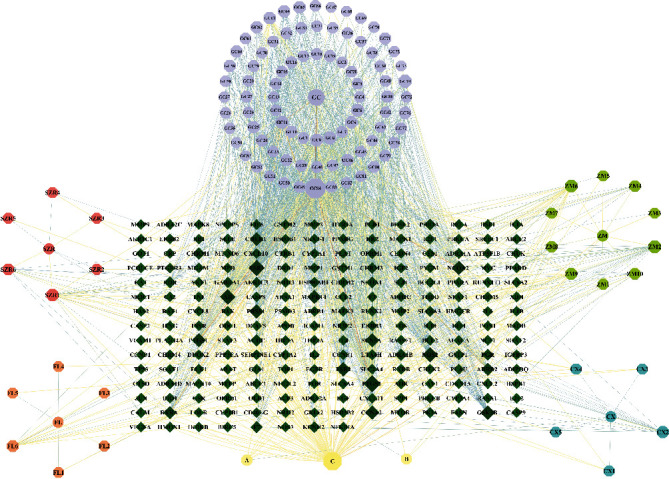

A total of 204 different drug targets were screened using the TCMSP database and were standardized by the UniProt database, which included the 26 in Semen ziziphi spinosae, 16 in Poria cocos, 90 in Rhizoma anemarrhenae, 23 in Rhizoma chuanxiong, and 193 in Glycyrrhiza glabra. The data of potential active ingredients and potential targets of SZRD in the treatment of PDSD were imported into Cytoscape 3.7.2 software to obtain a diagram of the traditional Chinese medicine component-target network (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Composition-target network of SZRD. Circles are for traditional Chinese medicine; octagons are compound component; diamonds are target. GC: Glycyrrhiza glabra; SZR: Semen ziziphi spinosae; FL: Poria cocos; ZM: Rhizoma anemarrhenae; CX: Rhizoma chuanxiong; A: common components of Glycyrrhiza glabra and Rhizoma chuanxiong; B: common components of Glycyrrhiza glabra and Semen ziziphi spinosae; C: common components of Glycyrrhiza glabra and Rhizoma anemarrhenae.

3.2. Related Targets for Disease

After combining the three databases and deleting repeated targets, a total of 9777 PD-related targets and 10748 SD-related targets were obtained from the OMIM, DisGeNET, and GeneCards databases.

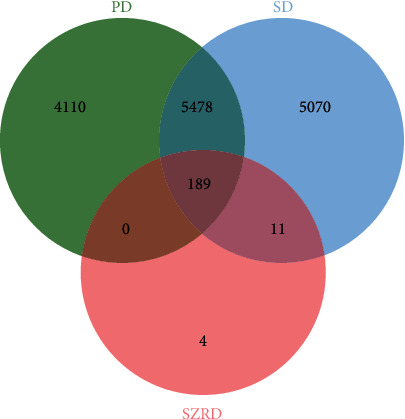

3.3. Common Targets for Diseases and Drugs

A total of 9777 PD-related targets, 10748 SD-related targets, and 204 SZRD drug prediction targets were imported using the Venny online mapping platform. After mapping, 189 intersection targets of SZRD and PDSD were obtained (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Disease-drug target Venn diagram.

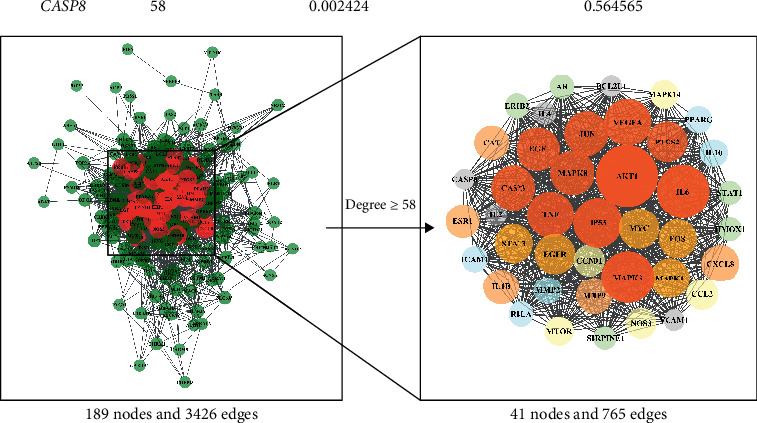

3.4. PPI Network Construction

A total of 189 targets were imported into the STRING platform to construct a PPI network. Then, 189 nodes and 3426 edges were also obtained using this platform. The double median of “Degree,” that is, “Degree ≥58,” was used to screen the intersection targets. Thus, 41 nodes, 765 edges, and a total of 41 core targets for SZRD treatment of PDSD were obtained (Table 3). Import the PPI network information obtained from the STRING platform into Cytoscape (3.7.2) software for visualization (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Core target information table.

| Target | Degree | Betweenness centrality (BC) | Closeness centrality (CC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AKT1 | 123 | 0.064225 | 0.731518 |

| IL6 | 110 | 0.033377 | 0.693727 |

| MAPK3 | 109 | 0.052416 | 0.693727 |

| TP53 | 105 | 0.027917 | 0.676259 |

| VEGFA | 100 | 0.016309 | 0.664311 |

| TNF | 98 | 0.018693 | 0.661972 |

| CASP3 | 97 | 0.019316 | 0.661972 |

| JUN | 97 | 0.021842 | 0.664311 |

| EGF | 95 | 0.020902 | 0.657343 |

| MAPK8 | 95 | 0.017033 | 0.657343 |

| PTGS2 | 91 | 0.032141 | 0.646048 |

| MAPK1 | 90 | 0.012068 | 0.639456 |

| EGFR | 89 | 0.016470 | 0.641638 |

| MYC | 89 | 0.013782 | 0.639456 |

| STAT3 | 88 | 0.011530 | 0.635135 |

| FOS | 87 | 0.033525 | 0.639456 |

| CXCL8 | 85 | 0.016357 | 0.626667 |

| MMP9 | 85 | 0.027723 | 0.632997 |

| IL1B | 82 | 0.013500 | 0.626667 |

| CAT | 81 | 0.038221 | 0.624585 |

| ESR1 | 79 | 0.010994 | 0.616393 |

| CCND1 | 77 | 0.006779 | 0.610390 |

| CCL2 | 76 | 0.005212 | 0.608414 |

| NOS3 | 74 | 0.020902 | 0.614379 |

| MTOR | 71 | 0.006984 | 0.598726 |

| MAPK14 | 71 | 0.005773 | 0.600639 |

| IL10 | 70 | 0.003254 | 0.593060 |

| MMP2 | 69 | 0.003821 | 0.596825 |

| PPARG | 68 | 0.008861 | 0.594937 |

| ICAM1 | 67 | 0.002937 | 0.591195 |

| RELA | 67 | 0.014775 | 0.585670 |

| ERBB2 | 66 | 0.009451 | 0.587500 |

| AR | 64 | 0.017042 | 0.589342 |

| HMOX1 | 63 | 0.006109 | 0.580247 |

| STAT1 | 63 | 0.006329 | 0.574924 |

| SERPINE1 | 62 | 0.004200 | 0.580247 |

| IL4 | 61 | 0.002350 | 0.576687 |

| IL2 | 60 | 0.002819 | 0.569697 |

| VCAM1 | 60 | 0.002099 | 0.574924 |

| BCL2L1 | 59 | 0.002173 | 0.567976 |

| CASP8 | 58 | 0.002424 | 0.564565 |

Figure 3.

Core target PPI network. As the figure shows, the larger area of the circle could be considered as more important in this network.

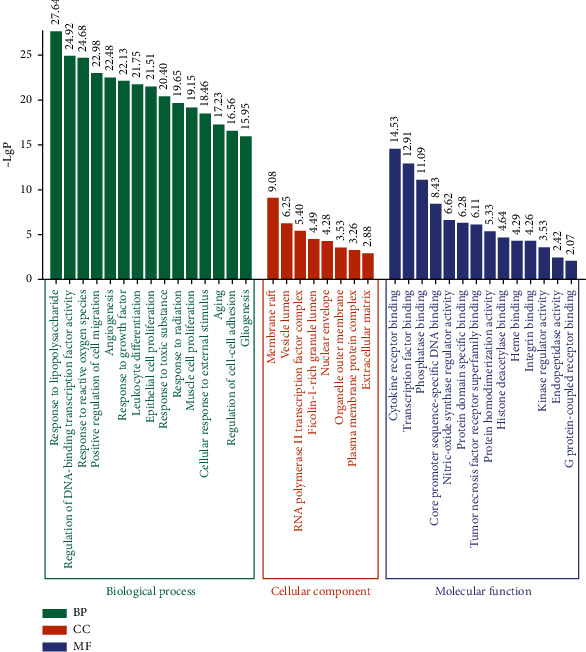

3.5. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis

The GO function enrichment analysis of the 41 core targets was performed on the DAVID platform, and a total of 1423 GO items were obtained, including 1325 BP, 36 CC, and 62 MF. The first 15, 8, and 14 items were selected based on the P value for visual analysis (Figure 4). Results showed that the treatment of PDSD by SZRD mainly involves BP such as cell migration, angiogenesis, leukocyte differentiation, cell proliferation, stress, cell aging, cell adhesion, and cell regeneration. These targets pass through cytokine receptor binding, transcription factor binding specificity, phosphatase binding, DNA binding domain specificity, protein structure combining, G protein coupled receptor molecules, and other functions, and they play a role in the cell membrane, RNA polymerase II transcription factor complex, nucleus and organelle outer membrane and plasma membrane protein complexes, and extracellular matrix components.

Figure 4.

GO function enrichment results of SZRD in the treatment of PDSD.

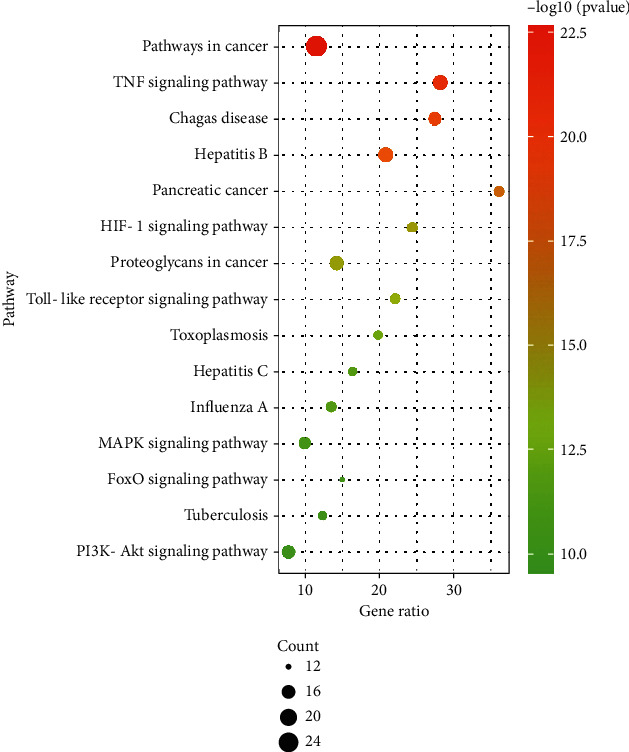

One hundred and nine signal pathways were enriched by KEGG pathway analysis of the core targets using the DAVID platform. According to the P value < 0.05 and the number of genes ≥ 12, 15 signal pathways with high probability were screened out for visual analysis as shown in Table 4 and Figure 5. Moreover, Figure 5 shows that SZRD treatment of PDSD may be mainly related to TNF, PI3K-Akt, MAPK, HIF-1, Toll-like receptor, FoxO, and other signaling pathways.

Table 4.

KEGG pathway enrichment results.

| Term | % | Count | P value | Related genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa05200: pathways in cancer | 65.8536 | 27 | 2.30E-23 | CXCL8, PTGS2, RELA, EGFR, MAPK8, CASP8, CCND1, MYC, CASP3, ERBB2, AKT1, MAPK1, MAPK3, JUN, EGF, STAT1, MMP2, STAT3, FOS, MMP9, MTOR, VEGFA, AR, IL6, PPARG, TP53, BCL2L1 |

| hsa04668: TNF signaling pathway | 43.9024 | 18 | 3.19E-21 | JUN, VCAM1, FOS, PTGS2, MAPK14, TNF, MMP9, RELA, ICAM1, IL6, MAPK8, CASP8, IL1B, CASP3, CCL2, AKT1, MAPK1, MAPK3 |

| hsa05161: hepatitis B | 43.9024 | 18 | 7.08E-19 | JUN, CXCL8, STAT1, STAT3, FOS, TNF, MMP9, RELA, IL6, MAPK8, CASP8, CCND1, MYC, CASP3, AKT1, MAPK1, TP53, MAPK3 |

| hsa05142: Chagas disease | 41.4634 | 17 | 1.04E-19 | IL10, JUN, CXCL8, SERPINE1, FOS, MAPK14, TNF, IL2, RELA, IL6, MAPK8, CASP8, IL1B, CCL2, AKT1, MAPK1, MAPK3 |

| hsa05205: proteoglycans in cancer | 41.4634 | 17 | 4.91E-15 | MMP2, STAT3, MAPK14, ESR1, TNF, MMP9, EGFR, MTOR, VEGFA, CCND1, MYC, CASP3, ERBB2, AKT1, MAPK1, TP53, MAPK3 |

| hsa04151: PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 39.0243 | 16 | 3.03E-10 | NOS3, EGF, EGFR, IL2, MTOR, RELA, VEGFA, IL4, IL6, CCND1, MYC, AKT1, MAPK1, TP53, BCL2L1, MAPK3 |

| hsa04010: MAPK signaling pathway | 36.5853 | 15 | 5.72E-11 | JUN, EGF, FOS, MAPK14, TNF, EGFR, RELA, MAPK8, MYC, IL1B, CASP3, AKT1, MAPK1, TP53, MAPK3 |

| hsa05212: pancreatic cancer | 34.1463 | 14 | 1.31E-17 | STAT1, EGF, STAT3, EGFR, RELA, VEGFA, MAPK8, CCND1, ERBB2, AKT1, MAPK1, TP53, BCL2L1, MAPK3 |

| hsa04066: HIF-1 signaling pathway | 34.1463 | 14 | 2.96E-15 | NOS3, EGF, STAT3, SERPINE1, EGFR, MTOR, RELA, VEGFA, IL6, ERBB2, AKT1, MAPK1, HMOX1, MAPK3 |

| hsa04620: Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 34.1463 | 14 | 1.11E-14 | JUN, CXCL8, STAT1, FOS, MAPK14, TNF, RELA, IL6, MAPK8, CASP8, IL1B, AKT1, MAPK1, MAPK3 |

| hsa05164: influenza A | 34.1463 | 14 | 7.36E-12 | JUN, CXCL8, STAT1, MAPK14, TNF, RELA, ICAM1, IL6, MAPK8, IL1B, CCL2, AKT1, MAPK1, MAPK3 |

| hsa05145: toxoplasmosis | 31.7073 | 13 | 5.84E-13 | IL10, STAT1, STAT3, MAPK14, TNF, RELA, MAPK8, CASP8, CASP3, AKT1, MAPK1, BCL2L1, MAPK3 |

| hsa05160: hepatitis C | 31.7073 | 13 | 5.83E−12 | CXCL8, STAT1, EGF, STAT3, MAPK14, TNF, EGFR, RELA, MAPK8, AKT1, MAPK1, TP53, MAPK3 |

| hsa05152: tuberculosis | 31.7073 | 13 | 1.73E-10 | IL10, STAT1, MAPK14, TNF, RELA, IL6, MAPK8, CASP8, IL1B, CASP3, AKT1, MAPK1, MAPK3 |

| hsa04068: FoxO signaling pathway | 29.2682 | 12 | 1.45E-10 | IL10, IL6, MAPK8, CCND1, EGF, STAT3, CAT, MAPK1, AKT1, MAPK14, EGFR, MAPK3 |

Figure 5.

KEGG enrichment bubble diagram.

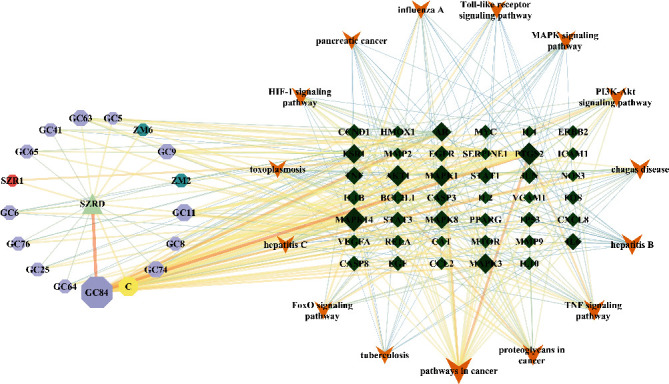

3.6. Construction of “H-C-T-P” Network

The “H-C-T-P” network was constructed using the 17 major components, 41 core targets, and 15 signal pathways of SZRD in the treatment of PDSD (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

H-C-T-P network diagram. Triangle is SZRD; octagons are compound component; diamonds are target; V is pathway.

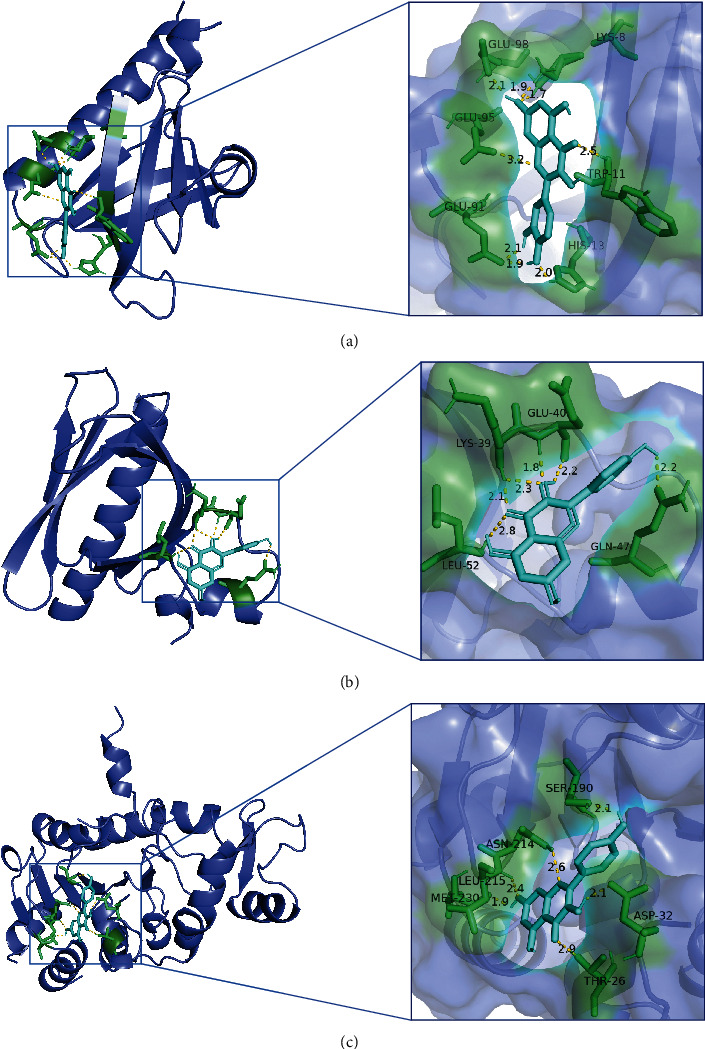

3.7. Molecular Docking Results and Analysis

According to Table 3, the top 5 targets of degree are AKT1, IL6, MAPK1, TP53, and VEGFA. The docking targets with the two active components with the highest degree of quercetin (degree = 127) and kaempferol (degree = 104) in SZRD were docking. As shown in Table 5, the binding energy of quercetin, kaempferol with AKT1, IL6, MAPK1, TP53, and VEGFA was all less than -5.0 kcal·mol−1, showing good binding force. The binding of AKT1 to quercetin and kaempferol and TP53 to kaempferol is shown in Figure 7.

Table 5.

Docking results of target protein and active compound.

| Core target | PDB ID | Binding energy/(kcal Mol-1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin | Kaempferol | ||

| AKT1 | 1UNQ | -6.18 | -6.51 |

| IL-6 | 1ALU | -5.72 | -5.90 |

| MAPK3 | 4QTB | -5.45 | -5.33 |

| TP53 | 1YC5 | -5.92 | -6.08 |

| VEGFA | 4QAF | -5.61 | -5.67 |

Figure 7.

Molecular docking diagram of chemical composition to target: (a) 1UNQ-quercetin; (b) 1UNQ-kaempferol; (c) 1YC5-kaempferol.

4. Discussion

4.1. Understanding of PDSD in Traditional Chinese Medicine and Western Medicine

In Western medicine, PDSD is believed to be associated with a variety of factors which may also be related to the increase or decrease of serum vitamin D, melatonin, serum cystatin (Cys) C, homocysteine (Hcy), and dopamine levels in the striatum caused by PD itself [31–34].

There is no related record of PDSD in traditional Chinese medicine classes, but according to its related clinical symptoms, it can be classified as a combination of “fibrillation” and “insomnia.” SZRD is a classic prescription, with tranquilizing properties, mainly treating “deficiency of liver and blood, deficiency of heat, and internal disturbance.” This prescription uses a lot of Semen ziziphi spinosae that nourishes the blood and liver and gives peace of mind. Rhizoma anemarrhenae nourishes Yin and clears the heat, and when the evil heat is gone, the healthy Qi is restored. “Poria cocos calms the heart and tranquilizes the mind.” Moreover, the theory of the properties of drugs says it is “good at calming the mind.” Rhizoma anemarrhenae and Poria cocos are used to help Semen ziziphi spinosae calm the mind from vexation. The nature of Rhizoma chuanxiong is scattered, “Qi medicine in the blood,” and is introduced into the liver meridian. Furthermore, this regulates Qi activity to help the liver recover its ability to dredge and release Qi. Rihua Zi medicine said that it “cures all wind, all Qi, all strain, all blood, and replenish five kinds of weakness.” Rhizoma chuanxiong is used in combination with King medicine, which has a magical effect to help sanguification and liver recuperation. Then, Glycyrrhiza glabra is used to harmonize the various drugs. All the drugs work together, to calm the mind in addition to the effect of vexation.

4.2. The Mechanism Prediction of SZRD for PDSD

Based on the network pharmacological research method, a total of 17 major active components of SZRD, which include quercetin, kaempferol, visistin, 7-methoxy-2-methyl isoflavone, naringenin, anhydroicaritin, formononetin, stigmasterol, licochalcone A, and isorhamnetin, in the treatment of PDSD were obtained.

Quercetin, kaempferol, and isorhamnetin are flavonoids which can scavenge reactive oxygen free radicals and achieve antioxidant and neuroprotective effects [35–38]. In the H2O2-induced PD model PC-12 cells, quercetin treatment increased cell viability, reduced mutagenesis of antioxidant enzymes, and reduced apoptosis of cells and hippocampal neurons [39]. In addition, quercetin can significantly reduce inflammation and oxidative damage in the striatum of PD model rats induced by 6-hydrox-ydopamine (6-OHDA) or 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) [40]. Filomeni et al. found that kaempferol can significantly protect neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y nerve cells) and major neurons from rotenone damage [41]. Moreover, it can reduce protease lysis and nuclear apoptosis and significantly reduce oxidative stress levels and mitochondrial hydroxyl compound content [41]. We also found that kaempferol may play a neuroprotective role by inhibiting cysteine proteinase-3 and by reducing brain cell apoptosis [42]. At the same time, quercetin and kaempferol have sedative and hypnotic effects, and both can also improve the effects of sleep disorders [43–46].

According to the GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis results, we speculated that the mechanism of SZRD in the treatment of PDSD may be mainly related to TNF, PI3K-Akt, MAPK, HIF-1, Toll-like receptors, and FoxO-associated signaling pathways. Such as involving AKT1, IL6, MAPK3, TP53, and VEGFA multiple key targets, cell aging, adhesion, regeneration, and angiogenesis, leukocyte differentiation is closely related to the process of cell metabolism. Recent studies have shown that PI3K-Akt, MAPK, and FOXO are all involved in the process of human cell apoptosis [47–49]. AKT1, an important member of the AKT (protein kinase B, PKB) family, is an intracellular serine/threonine involved in a variety of cellular BP, and its activation is mainly dependent on the PI3K signaling pathway [50]. AKT1 is activated by phosphorylation, which in turn activates downstream signaling molecules [51]. The PI3K/Akt signal transduction pathway is involved in a variety of cytokines, and it has been found that by reducing the phosphorylation levels of PI3K, AKT, and mTOR, the transduction of this pathway can play a role in the treatment of MPTP-induced PD mice [52]. Studies have shown that cytokines are involved in regulating sleep, among which interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α and TNF-β) play a role in promoting sleep [53–55]. Elevation of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and TNF-α can directly act on central sleep-wake neurons, causing increased nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and regulating the pathologic circadian rhythm [56, 57]. IL-1β and TNF-α, as sleep-regulating cytokines, can induce the production of each other [58]. After the activation of the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, the activity of inflammatory mediator genes was upregulated, which promoted the production of a large number of cytokines and the increase in the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, thus playing a role in regulating sleep [59]. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is a kind of serine/threonine protein kinases in cells. The MAPK-mediated signal transduction pathway is mainly related to the inflammatory response and plays a role in the phosphorylation of protein c-Jun [60]. Studies have shown that SP600125, a specific inhibitor of the JNK signaling pathway, significantly reduced the expression of phosphorylated c-Jun in the substantia nigra of the midbrain in PD model mice [61]. It was found that MAPK, AKT1, and IL-6 in the serum of patients with anxiety were all increased, and there was a significant positive correlation between anxiety severity and sleep quality. With the improvement of anxiety state and sleep state, the expression of MAPK decreases gradually [62–64]. The FOXO signaling pathway is interrelated with the PI3K-Akt and MAPK signaling pathways [65, 66]. FoxO3a protein is an important subtype of the FoxO family and is an important cytokine in PI3K-Akt signal transduction [67]. After phosphorylation and modification of FoxO3a, specific downstream target genes can be activated to induce autophagy and apoptosis of cells [68]. For example, when the MAPK pathway is activated or the PI3K-Akt pathway is inhibited, FoxO3a is dephosphorylated, thereby regulating different downstream factors and promoting cell apoptosis [68]. HIF-1 and its target gene VEGF can play a protective role in PD through mechanisms such as antioxidant stress, and the overexpression of VEGF can promote the proliferation and differentiation of neurons and reduce MPTP-induced substantia nigra cell injury [69]. The expression of angiogenic factor VEGF increased with an increase in the severity of sleep disturbance [70].

5. Conclusions

In this study, we used the network pharmacology research method to predict the chemical composition, target, and signal pathways at multiple levels. The prediction results were verified by molecular docking technology. The results show that SZRD plays an important role in the treatment of sleep disorders associated with PD through “multicomponent, multitarget, and multipathway,” which provides a new theoretical basis for further experimental research and clinical treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the web database platform and software for data analysis. I would like to thank my tutor Professor Juan Zhang for her guidance on the ideas and writing of the article. Thanks are due to Professor Yu and Professor Xie for their guidance on the content of my article. Thanks are due to my classmates for their help in data collation and analysis. This article could not have been finished without their help. This study was totally supported by the National Natural Foundation of China (No. 81774299) and the Scientific Research Project of the Chinese National Medical Association (No. 2020ZY070-410033).

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Yan-yun Liu and Li-hua Yu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Berardelli A., Wenning G. K., Antonini A., et al. EFNS/MDS-ES recommendations for the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. European Journal of Neurology . 2013;20(1):16–34. doi: 10.1111/ene.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guidelines for the treatment of Parkinson's disease in China (fourth edition) Chinese Journal of Neurology . 2020;53(12):973–986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan Y. C., Wang F. L. Evaluation of the clinical effect of carbidopa- levodopa controlled- release tablet in the treatment of Parkinsonundefineds disease with sleep disorde. World Journal of Sleep Medicine . 2019;6(5):544–546. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Z. Y., Wang J. Role of dopaminergic agonists in the treatment of non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Shanghai Med Pharm . 2015;36(3):9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei H. J., Du M., Bai H. Y. Correlations of melatonin and glutathione levels with oxidative stress mechanism in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Academiae Medicinae Sinicae . 2019;41(2):183–187. doi: 10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.10775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juri C., Chaná P., Tapia J., Kunstmann C., Parrao T. Quetiapine for insomnia in Parkinson Disease. Clinical Neuropharmacology . 2005;28(4):185–187. doi: 10.1097/01.wnf.0000174932.82134.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng A. P., Wu M. Q., Yuan P. Q., Yanag L. Research progress of sleep disorders in patients with Parkinson's disease. Journal of nursing . 2019;26(18):27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Q. H., Wang H. L., Zhou X. L., et al. Efficacy and safety of Suanzaoren decoction for chronic insomnia disorder in adults: study protocol for randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled trial. BMJ Open . 2017;7(4, article e014280) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y., Yang X., Xia P. F., et al. Review of chemical constituents, pharmacological effects and clinical applications of Suanzaoren decoction and prediction and analysis of its Q-markers. China journal of Chinese materia medica . 2020;45(12):2765–2771. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20190812.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niu X. Y., He B. S., du Y., et al. The investigation of immunoprotective and sedative hypnotic effect of total polysaccharide from Suanzaoren decoction by serum metabonomics approach. Journal of Chromatography B . 2018;1086:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhan L. H., Dong Y. J., Yang K., et al. Soporific effect of modified Suanzaoren decoction and its effects on the expression of CCK-8 and orexin-A. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2020;2020:17. doi: 10.1155/2020/6984087.6984087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang B., Zhang A. H., Sun H., et al. Metabolomic study of insomnia and intervention effects of Suanzaoren decoction using ultra-performance liquid-chromatography/electrospray-ionization synapt high-definition mass spectrometry. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis . 2012;58:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2011.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang W. M., Bao Y. C., Wang H., et al. Diagnosis and treatment of fibrillation (Parkinson's disease) Clinical Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine . 2012;24(11):1125–1126. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X., Wang P., Ding L., Zhang S. B., Shi K., You Q. Y. Effects of Suanzaoren decoction on the expression of nuclear receptor PPARγ and its co-activator PGC-1α in elderly chronic sleep deprivation rats. Modernization of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Materia Medica-World Science and Technology . 2021;23(5):1339–1346. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong Y. X. Clinical effect evaluation of Suanzaoren decoction on insomnia. Inner Mongolia Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine . 2021;40(6):12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou K. T., Yu Y. X. Clinical efficacy and safety of modified Suanzaoren decoction combined with escitalopram tablets in the treatment of insomnia. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rational Drug Use . 2021;14(15):134–136. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ru J., Li P., Wang J., et al. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. Journal of Cheminformatics . 2014;6, article 24735618:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang S., Wang H., Lu Y. Tianfoshen oral liquid: a CFDA approved clinical traditional Chinese medicine, normalizes major cellular pathways disordered during colorectal carcinogenesis. Oncotarget . 2017;8(9):14549–14569. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y. Y., Yu W. D., Shi C. L., et al. Network pharmacology of Yougui pill combined with Buzhong Yiqi decoction for the treatment of sexual dysfunction. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2019;2019:10. doi: 10.1155/2019/1243743.1243743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Research . 2017;45(D1):D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamosh A., Scott A. F., Amberger J. S., Bocchini C. A., McKusick V. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic acids research . 2005;33(Database issue, article 15608251):D514–D517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Safran M., Dalah I., Alexander J., et al. GeneCards version 3: the human gene integrator. Database . 2010;2010, article 20689021 doi: 10.1093/database/baq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piñero J., Ramírez-Anguita J. M., Saüch-Pitarch J., et al. The DisGeNET knowledge platform for disease genomics: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Research . 2020;48(D1):D845–D855. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szklarczyk D., Gable A. L., Lyon D., et al. STRING V11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Research . 2019;47(D1):D607–D613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Research . 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang D. W., Sherman B. T., Lempicki R. A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nature protocols . 2009;4(1):2498–2504. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heatmap was plotted by https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/, a free online platform for data analysis and visualization

- 28.Goodsell D. S., Zardecki C., di Costanzo L., et al. RCSB protein data bank: enabling biomedical research and drug discovery. Protein Science . 2020;29(1):52–65. doi: 10.1002/pro.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Hachem N., Haibe-Kains B., Khalil A., Kobeissy F. H., Nemer G. AutoDock and AutoDockTools for protein-ligand docking: beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) as a case study. Methods in Molecular Biology . 2017;1598, article 28508374:391–403. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6952-4_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baugh E. H., Lyskov S., Weitzner B. D., Gray J. J. Real-time PyMOL visualization for Rosetta and PyRosetta. PLOS ONE . 2011;6(8, article e21931) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma Z. W., He P. C., Ma T. Correlation analysis of sleep disturbance and serum vitamin D level in patients with Parkinson's disease. Journal of Applied Clinical Medicine . 2020;24(24):53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li L. Y. Correlation between plasma melatonin levels and non-motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease . Zhengzhou university; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang L., Huang M. L., Fu R. Correlation between serum Cysc, Hcy levels and sleep disorders in patients with early Parkinson's disease. Chinese Journal of Gerontology . 2020;40(3):571–574. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo X. F., Li Y., Hu J., Zhang C. H. Regulating effect of gardenoside on sleep disturbance in experimental Parkinson's disease rats and its mechanism. Ournal of Jilin University (Medical Edition) . 2020;46(6):1177–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Y. H., Li Y. Y., Yu H. Y., et al. Quercetin attenuates chronic ethanol hepatotoxicity: Implication of "free" iron uptake and release. Food and Chemical Toxicology . 2014;67, article 24569067:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soucek P., Kondrova E., Hermanek J., et al. New model system for testing effects of flavonoids on doxorubicin-related formation of hydroxyl radicals. Anti-Cancer Drugs . 2011;22(2):176–184. doi: 10.1097/cad.0b013e328341a17b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajendran P., Rengarajan T., Nandakumar N., Palaniswami R., Nishigaki Y., Nishigaki I. Kaempferol, a potential cytostatic and cure for inflammatory disorders. European journal of medicinal chemistry . 2014;86, article 25147152:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi Y. H. The cytoprotective effect of isorhamnetin against oxidative stress is mediated by the upregulation of the Nrf2-dependent HO-1 expression in C2C12 myoblasts through scavenging reactive oxygen species and ERK inactivation. General Physiology and Biophysics . 2016;35(2):145–154. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2015034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bao D. K., Wang J. K., Pang X. B., Liu H. L. Protective effect of quercetin against oxidative stress-induced cytotoxicity in rat pheochromocytoma (PC-12) cells. Molecules . 2017;22(7):p. 1122. doi: 10.3390/molecules22071122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shamsher S., Puneet K. Piperine in combination with quercetin halt 6-OHDA induced neurodegeneration in experimental rats: biochemical and neurochemical evidences. Neuroscience research . 2018;133, article 29056550:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Filomeni G., Graziani I., de Zio D., et al. Neuroprotection of kaempferol by autophagy in models of rotenone-mediated acute toxicity: possible implications for Parkinson's disease. Neurobiology of Aging . 2012;33(4):767–785. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He Y. Z., Ding M. P., Wang Y. K., et al. Protective effect of kaempferol on cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Chinese Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine . 2009;27(8):1673–1675. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Q. J., Gan X. Research progress on extraction of quercetin from Sophora japonica and its effect on central nervous system. Chemical and biological engineering . 2007;24(3):11–13. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tao Y. H. Study on enzyme inhibitors of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) metabolism . Wuhan: Huazhong University of Science and Technology; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen W. J. Experimental study on anticonvulsant and sedative and hypnotic effects of bupleurin A . Guangzhou: Southern Medical University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhong J. W., Chen L. X., Cai B. C. Effect of Chinese herb oyster on hypnotic effect of pentobarbital sodium. Chinese Archives of Traditional Chinese Medicine . 2009;27(3):499–501. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rademacher Y. B. L., Matkowskyj K. A., LaCount E. D., Carchman E. H. Topical application of a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor prevents anal carcinogenesis in a human papillomavirus mouse model of anal cancer. European Journal of Cancer Prevention . 2019;28(6):483–491. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang Z., Zhang J. L., Qiu J. T., Cui S. ThePD‐1/PD‐L1binding inhibitorBMS‐202 suppresses the synthesis and secretion of gonadotropins and enhances apoptosis via p38MAPKsignaling pathway. Drug Development Research . 2021;34309063:1–8. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi Y. Y., Meng X. T., Xu Y. N., Tian X. J. Role of FOXO protein's abnormal activation through PI3K/AKT pathway in platinum resistance of ovarian cancer. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research . 2021;47(6):1946–1957. doi: 10.1111/jog.14753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo X. T., Liang J. F., Zhang X. B. Research progress on the relationship between PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and Parkinson's disease. Journal of Modern Medicine & Health . 2015;31(7):1019–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo R. L., Ya J., Li X. J., Wang W. L., Mo Z. F., et al. Expression of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in tumors and its role in proliferation and apoptosis. Hebei Medical Journal . 2012;34(12):1863–1864. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lv R. X., Du L. L., Zhou F. H., Zhang L. X., Liu X. Y. Study on the mechanism of rosmarinic acid inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and promoting autophagy to alleviate Parkinson's disease. Journal of Ningxia Medical University . 2019;41(12):1189–1194. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shearer W., Reuben J., Mullington J., et al. Soluble TNF-α receptor 1 and IL-6 plasma levels in humans subjected to the sleep deprivation model of spaceflight. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology . 2001;107(1):165–170. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Entzian P., Linnemann K., Schlaak M., Zabel P. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and circadian rhythms of hormones and cytokines. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine . 1996;153(3):1080–1086. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.3.8630548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang L., Zhang R. H., Shen Y., Qiao S. Z., Hui Z. L., Chen J. Shimian granules improve sleep, mood and performance of shift nurses in association changes in melatonin and cytokine biomarkers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Chronobiology International . 2020;37(4):592–605. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1730880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang Y., Xia L., Chen G. H. Study on changes of tumor necrosis factor-α in patients with primary insomnia. Chinese Journal of Clinicians (electronic version) . 2013;7(7):2877–2879. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wright K., Drake A., Frey D., et al. Influence of sleep deprivation and circadian misalignment on cortisol, inflammatory markers, and cytokine balance. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity . 2015;47, article 25640463:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo A. S., Liu C., Li B. S., Zhu Z. J., Chen W. G., Li A. H. Effects of acupoint embedding thread on monoamine transmitters, IL-1β and TNF-α contents in hypothalamus of rats with insomnia. Shanghai Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion . 2014;33(7):672–675. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luyendyk J., Schabbauer G., Tencati M., Holscher T., Pawlinski R., Mackman N. Genetic analysis of the role of the PI3K-Akt pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine and tissue factor gene expression in monocytes/macrophages. Journal of Immunology . 2008;180(6):4218–4226. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu S. Y., Xu P., Luo X. L., Hu J. F., Liu X. H. (7R,8S)-Dehydrodiconiferyl alcohol suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in BV2 microglia by inhibiting MAPK signaling. Neurochemical Research . 2016;41(7):1570–1577. doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-1870-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y. S., Wei Z. F., Tian Q. Y., Zhang Z. F., Zhou H. X., Zhang Y. X. Regulation of JNK pathway in the process of inflammation and apoptosis of substantia nigra cells in subacute Parkinson's disease model mice. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology . 2007;5:601–605. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoshihiko N., Taku A., Hikaru Y., Norio S., Minoru T., Hiroshi T. Yokukansan enhances the proliferation of B65 neuroblastoma. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine . 2017;7(1):34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang C. X., Sun N., Ren Y., et al. Association between AKT1 gene polymorphisms and depressive symptoms in the Chinese Han population with major depressive disorder. Neural Regeneration Research . 2012;7(3):235–239. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Niraula A., Witcher K. G., Sheridan J. F., Godbout J. P. Interleukin-6 induced by social stress promotes a unique transcriptional signature in the monocytes that facilitate anxiety. Biological Psychiatry . 2019;85(8):679–689. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu H. C., Zhang J. W., Sun Z. G., Xiang S., Qiao Y., Lian F. Effects of electroacupuncture on expression of PI3K/Akt/Foxo3a in granulosa cells from women with Shen (kidney) deficiency syndrome undergoing in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine . 2019;25(4):252–258. doi: 10.1007/s11655-019-2948-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matsuda F., Inoue N., Maeda A., et al. Expression and function of apoptosis initiator FOXO3 in granulosa cells during follicular atresia in pig ovaries. Journal of Reproduction and Development . 2011;57(1):151–158. doi: 10.1262/jrd.10-124h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guo D. M., Xiao L. L., Hu H. J., Liu M. H., Yang L., Lin X. FGF21 protects human umbilical vein endothelial cells against high glucose- induced apoptosis via PI3K/Akt/Fox3a signaling pathway. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications . 2018;32(8):729–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tseng A., Wu L. H., Shieh S. S., Wang D. L. SIRT3 interactions with FOXO3 acetylation, phosphorylation and ubiquitinylation mediate endothelial cell responses to hypoxia. The Biochemical Journal . 2014;464(1):157–168. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Z., Yan J., Chang Y., ShiDu Yan S., Shi H. Hypoxia inducible factor-1 as a target for neurodegenerative diseases. Current Medicinal Chemistry . 2011;18(28):4335–4343. doi: 10.2174/092986711797200426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dong Y. B., Wu G. Y., Zhu T., et al. VEGF promotes cartilage angiogenesis by phospho-ERK1/2 activation of Dll4 signaling in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis caused by chronic sleep disturbance in Wistar rats. Oncotarget . 2017;8(11):17849–17861. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.