Abstract

Background

International guidelines suggest using a higher (> 10 cm H2O) positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) in patients with moderate-to-severe ARDS due to COVID-19. However, even if oxygenation generally improves with a higher PEEP, compliance, and Paco2 frequently do not, as if recruitment was small.

Research Question

Is the potential for lung recruitment small in patients with early ARDS due to COVID-19?

Study Design and Methods

Forty patients with ARDS due to COVID-19 were studied in the supine position within 3 days of endotracheal intubation. They all underwent a PEEP trial, in which oxygenation, compliance, and Paco2 were measured with 5, 10, and 15 cm H2O of PEEP, and all other ventilatory settings unchanged. Twenty underwent a whole-lung static CT scan at 5 and 45 cm H2O, and the other 20 at 5 and 15 cm H2O of airway pressure. Recruitment and hyperinflation were defined as a decrease in the volume of the non-aerated (density above −100 HU) and an increase in the volume of the over-aerated (density below −900 HU) lung compartments, respectively.

Results

From 5 to 15 cm H2O, oxygenation improved in 36 (90%) patients but compliance only in 11 (28%) and Paco2 only in 14 (35%). From 5 to 45 cm H2O, recruitment was 351 (161-462) mL and hyperinflation 465 (220-681) mL. From 5 to 15 cm H2O, recruitment was 168 (110-202) mL and hyperinflation 121 (63-270) mL. Hyperinflation variably developed in all patients and exceeded recruitment in more than half of them.

Interpretation

Patients with early ARDS due to COVID-19, ventilated in the supine position, present with a large potential for lung recruitment. Even so, their compliance and Paco2 do not generally improve with a higher PEEP, possibly because of hyperinflation.

Key Words: acute respiratory distress syndrome, coronavirus disease 2019, mechanical ventilation, positive end-expiratory pressure

Abbreviations: PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure

Graphical Abstract

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT, SEE PAGE 869

ARDS is characterized by inflammatory pulmonary edema with heavy lungs, acute hypoxemia, and low compliance.1 CT has clarified that hypoxemia depends on a large number of alveoli perfused but not aerated and low compliance on the small dimension of the ventilated lung.2 A higher positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) can be used to reopen the non-aerated alveoli (anatomical recruitment) and relieve hypoxemia.3 , 4 As ventilation gets distributed in more units, compliance will probably increase, and Paco 2 will probably decrease.4, 5, 6 However, in patients with a small non-aerated compartment, recruitment is modest or nil. With a higher PEEP, oxygenation can still improve via other mechanisms, including a decrease in the cardiac output,6 , 7 but compliance and Paco 2 probably will not, because of alveolar overdistention.4, 5, 6 As a general rule, the more severe the hypoxemia, the larger the alveolar collapse, the greater the probability of a positive effect of a higher PEEP on lung morphology (ie, larger recruitment), lung function (ie, better gas exchange and mechanics),4 and possibly survival.8 , 9

In line with this general model and recommendations for treating ARDS of other origins,10 international guidelines suggest using a higher PEEP (> 10 cm H2O) for moderate-to-severe hypoxemia due to COVID-19.11 However, many patients with this novel disease present with less than expected alveolar collapse,12 , 13 so their potential for recruitment may be smaller than in other ARDS. Accordingly, compliance or Paco 2 frequently worsen with a higher PEEP.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 These and other data21, 22, 23 suggest that in COVID-19, hypoxemia is caused not only by alveolar collapse and that the primary response to a higher PEEP is not always lung recruitment.

This study aimed to describe the response to a higher PEEP in patients with early ARDS due to COVID-19. We hypothesized that this is generally negative because the potential for lung recruitment is low.

Study Design and Methods

This study was approved by our institutional review board (protocol 465/20). Informed consent was obtained according to local regulations.

Forty patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 underwent a PEEP trial and a lung CT within 3 days of endotracheal intubation. Inclusion criteria were: (i) admission to our ICU with ARDS24; (ii) ongoing invasive mechanical ventilation with deep sedation and paralysis; and (iii) one of the authors being available for collecting data. Exclusion criteria were: (i) lung CT already taken after intubation; (ii) patient too unstable for transfer to the radiology unit; and (iii) pulmonary air leak. We studied 10 nonconsecutive patients from March 1, 2020 to May 31, 2020, when we were frequently unavailable because of the exceptional clinical workload, and 30 consecutive patients from October 16, 2020 to December 9, 2020 (e-Fig 1). Those with a BMI > 35 (obese) underwent a slightly different protocol than the others, as reported in the next two paragraphs.

PEEP Trial

Patients were studied in the supine semirecumbent position. After a recruitment maneuver,4 PEEP was set at 15, 10, and 5 cm H2O. If the patient was obese, PEEP was set at 20, 15, and 10 cm H2O. Other settings were kept constant. Gas exchange and respiratory system mechanics were assessed after 20 minutes at each PEEP level.

Lung CT

Patients were studied in the supine horizontal position. After a recruitment maneuver,4 a lung CT was taken at 45 and 5 cm H2O (the first 20 patients) or 15 and 5 cm H2O (the other 20 patients) of airway pressure. If the patient was obese, CTs were taken at 45 and 10 or 20 and 10 cm H2O. The total (tissue and gas) volume, the tissue weight, and the gas volume of the whole lung and its non-aerated (density above −100 HU), poorly aerated (from −100 to −500 HU), normally aerated (from −500 to −900 HU), and over-aerated (below −900 HU) compartments were measured as in Gattinoni et al.2 , 4 The expected premorbid lung weight was estimated from the subjects’ height.25 Recruitment and hyperinflation induced by any increase in airway pressure were computed as the absolute difference in total volume of the non-aerated or over-aerated compartment between 5 cm H2O (or 10 cm H2O in obese patients) and the higher airway pressure.4 , 26 , 27 We used the hyperinflation-to-recruitment ratio to weigh the risks and benefits of higher airway pressure.

To be consistent with other studies on ARDS unrelated to COVID-19,4 , 28 we also computed the recruited lung tissue as the difference in the non-aerated tissue weight between 5 cm H2O (or 10 cm H2O in obese patients) and the higher airway pressure and expressed it as a percentage of the lung weight with 5 cm H2O (or 10 cm H2O in obese patients). The tissue remaining non-aerated at 45 cm H2O of airway pressure was considered consolidated.

The same methods were applied to 10 equally spaced vertical levels forming each CT slice from the sternum to the vertebra. The pressure (super)imposed on each level was obtained as in Gattinoni et al2 and Pelosi et al.29 In healthy subjects lying supine, the (maximal) superimposed pressure on the most dorsal level is 2.6 ± 0.5 cm H2O.25

Aiming to describe the response to a higher PEEP, we present all the results as if airway pressure had been increased throughout the study. Moreover, because we included only four obese patients, results of their PEEP trial are reported as obtained with 5, 10, and 15 (rather than 10, 15, and 20) cm H2O of airway pressure, as for the other patients. Similarly, results of their lung CTs are reported as obtained with 5 and 45 (rather than 10 and 45), or 5 and 15 (rather than 10 and 20), cm H2O.

Please refer to e-Appendix 1 for other details on methods.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the median (Q1-Q3) or proportion. They were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney rank-sum test, Wilcoxon signed rank-sum test, Fisher exact test, Spearman rank-order correlation, and Friedman's repeated-measures analysis of variance on ranks. Post hoc comparisons were run with the Wilcoxon signed rank-sum test corrected with Bonferroni's method.

These analyses were done with Stata Statistical Software release 16 (Stata Corp. LLC). A two-tailed P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

We studied 40 patients with COVID-19 on invasive mechanical ventilation. Their characteristics at ICU admission are reported in e-Tables 1 and 2. Thirty-three (82.5%) were males and seven (17.5%) females, with a mean age of 66 (59-72) years. Three (8%) had a history of COPD, and four (10%) were obese. They were all transferred to the ICU for endotracheal intubation after 2 (1-5) days in the hospital. By that time, 36 (90%) had received some form of noninvasive ventilation. Initial C-reactive protein was 14 (8-17) mg/dL. Fifteen (38%) died in the ICU.

The study was performed 1 (0-1) day after ICU admission. The lung function and morphology of all 40 patients are described in Table 1 and e-Tables 3 and 4. With 5 cm H2O of PEEP, hypoxemia was mild (Pao 2:Fio 2 > 200 mm Hg) in five (13%), moderate (Pao 2:Fio 2 101-200 mm Hg) in 19 (47%), and severe (Pao 2:Fio 2 ≤ 100 mm Hg) in 16 (40%). The total lung volume was 2,368 (2,148-2,624) mL: 21% (14%-32%) in the non-aerated, 30% (25%-36%) in the poorly aerated, 44% (31%-52%) in the normally aerated, and 1.8% (0.3%-5.9%) in the over-aerated compartment. The lung tissue weight was 1,318 (1,114-1,633) g, 266 (143-570) g higher than expected. The lung gas volume was 999 (756-1,309) mL. The superimposed pressure increased along the sterno-vertebral axis, up to 11 (10-13) cm H2O. Accordingly, the non-aerated compartment was dorsal, and the over-aerated compartment was ventral (e-Fig 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 40 Patients With COVID-19, the Day of the Study, and With 5 cm H2O of PEEP

| Variable | Data |

|---|---|

| No. | 40 |

| Ventilatory setting | |

| Tidal volume, mL | 420 (385-445) |

| Tidal volume, mL/kg of PBW | 6.1 (5.9-6.7) |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 20 (18-22) |

| Fio2, % | 60 (55-95) |

| Minute ventilation, L/min | 8.3 (7.3-9.9) |

| Respiratory system mechanics | |

| Plateau airway pressure, cm H2O | 15 (14-16) |

| Driving airway pressure, cm H2O | 9 (8-10) |

| Compliance, mL/cm H2O | 45 (42-51) |

| Gas exchange | |

| Arterial pH | 7.39 (7.34-7.43) |

| Paco2, mm Hg | 47 (40-51) |

| Pao2, mm Hg | 78 (66-90) |

| Pao2/Fio2, mm Hg | 112 (84-154) |

| Lung tissue and gas distribution | |

| Total lung | |

| Tissue, g | 1,318 (1,114-1,633) |

| Gas, mL | 999 (756-1,309) |

| Non-aerated | |

| Tissue, g | 526 (384-743) |

| Gas, mL | 5 (0-10) |

| Poorly aerated | |

| Tissue, g | 516 (406-601) |

| Gas, mL | 216 (167-244) |

| Normally aerated | |

| Tissue, g | 286 (193-382) |

| Gas, mL | 713 (507-959) |

| Over-aerated | |

| Tissue, g | 3 (1-7) |

| Gas, mL | 40 (8-129) |

All data refer to the time of the study. Respiratory system mechanics and gas exchange were measured with 5 cm H2O PEEP. Other ventilator settings were at the discretion of the attending physicians. Lung CTs were taken in static conditions during an end-expiratory pause with 5 cm H2O of PEEP. PBW = predicted body weight; Fio2 = inspiratory fraction of oxygen; Pao2 = arterial tension of oxygen. The driving airway pressure was the difference between the plateau airway pressure and total PEEP measured with a 5-second end-inspiratory and end-expiratory pause. The compliance was the ratio of the tidal volume to the driving airway pressure. Data are reported as median (Q1-Q3). If the non-aerated compartment had a density > 0 HU (ie, higher than the density of water), the gas volume (in mL) was considered zero.

Functional Response to a Higher PEEP

The individual changes in gas exchange and respiratory system mechanics with 5, 10, and 15 cm H2O of PEEP are shown in Figure 1 . The Pao 2:Fio 2 progressively increased while the compliance initially increased but then decreased. The Paco 2 did not change. The mean arterial pressure slightly decreased, and the arteriovenous oxygen content difference increased (e-Table 5).

Figure 1.

The functional response to a higher PEEP. Gas exchange and respiratory system compliance were measured with 5, 10, and 15 cm H2O of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) while other ventilatory settings were kept constant (the so-called “PEEP trial”). Herein we show individual data recorded with the three different levels of PEEP and the group median values (red bars). Pao2 = arterial tension of oxygen. Fio2 = inspiratory fraction of oxygen. The compliance was the ratio of tidal volume to driving airway pressure, the difference between plateau airway pressure and total PEEP. P-values refer to the overall Friedman’s test (above), and the posthoc Wilcoxon signed rank-sum test, corrected with Bonferroni's method (below).

Overall, as PEEP was increased from 5 to 15 cm H2O, oxygenation improved in 36 (90%) patients, but compliance in only 11 (28%) and Paco 2 in only 14 (35%).

Morphological Response to a Higher PEEP

The quantitative analysis of lung CTs is shown in Tables 2 and 3 and in Figures 2 and 3 , and e-Figures 2-4.

Table 2.

Lung Tissue and Gas Distribution With 5 and 45 cm H2O of Airway Pressure

| Variable | Quantitative Analysis of Lung CT | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airway pressure, cm H2O | 5 | 45 | … |

| No. | 20 | 20 | … |

| Total lung | |||

| Tissue, g | 1,336 (1,112-1,586) | 1,439 (1,157-1,575) | .062 |

| Gas, mL | 950 (577-1,230) | 2,905 (2,410-3,345) | < .001 |

| Non-aerated | |||

| Tissue, g | 555 (404-742) | 197 (115-307) | < .001 |

| Gas, mL | 3 (0-10) | 0 (0-2) | .008 |

| Poorly aerated | |||

| Tissue, g | 502 (364-601) | 378 (313-498) | .011 |

| Gas, mL | 192 (160-256) | 199 (164-274) | .852 |

| Normally aerated | |||

| Tissue, g | 255 (156-382) | 777 (598-882) | < .001 |

| Gas, mL | 658 (356-922) | 2,288 (1,474-2,484) | < .001 |

| Over-aerated | |||

| Tissue, g | 3 (0-7) | 31 (18-45) | < .001 |

| Gas, mL | 46 (6-131) | 476 (217-766) | < .001 |

Twenty patients underwent a lung CT at 5 and 45 cm H2O of airway pressure. Herein we compare the distribution of tissue and gas in their whole lungs and in their four compartments at these two airway pressures. Data are reported as median (Q1-Q3). P value refers to the Wilcoxon signed rank-sum test. If the nonaerated compartment had a density > 0 HU (ie, higher than the density of water), the gas volume was considered zero.

Table 3.

Lung Tissue and Gas Distribution With 5 and 15 cm H2O of Airway Pressure

| Variable | Quantitative Analysis of Lung CT | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airway pressure, cm H2O | 5 | 15 | … |

| No. | 20 | 20 | … |

| Total lung | |||

| Tissue, g | 1,301 (1,157-1,658) | 1,331 (1,172-1,696) | .003 |

| Gas, mL | 999 (913-1,393) | 1,943 (1,683-2,322) | < .001 |

| Non-aerated | |||

| Tissue, g | 475 (311-754) | 301 (140-444) | < .001 |

| Gas, mL | 5 (0-10) | 2 (0-6) | .002 |

| Poorly aerated | |||

| Tissue, g | 517 (438-596) | 479 (345-601) | .794 |

| Gas, mL | 219 (190-233) | 220 (174-293) | .014 |

| Normally aerated | |||

| Tissue, g | 305 (255-388) | 517 (471-598) | < .001 |

| Gas, mL | 722 (642-989) | 1,414 (1,225-1,749) | < .001 |

| Over-aerated | |||

| Tissue, g | 1 (1-7) | 10 (6-26) | < .001 |

| Gas, mL | 16 (8-102) | 130 (70-324) | < .001 |

Twenty patients underwent a lung CT at 5 and 15 cm H2O of airway pressure. Herein we compare the distribution of tissue and gas in their whole lungs and in their four compartments at these two airway pressures. Data are reported as median (Q1-Q3). P-value refers to the Wilcoxon signed rank-sum test. If the nonaerated compartment had a density > 0 HU (ie, higher than the density of water), the gas volume was considered zero.

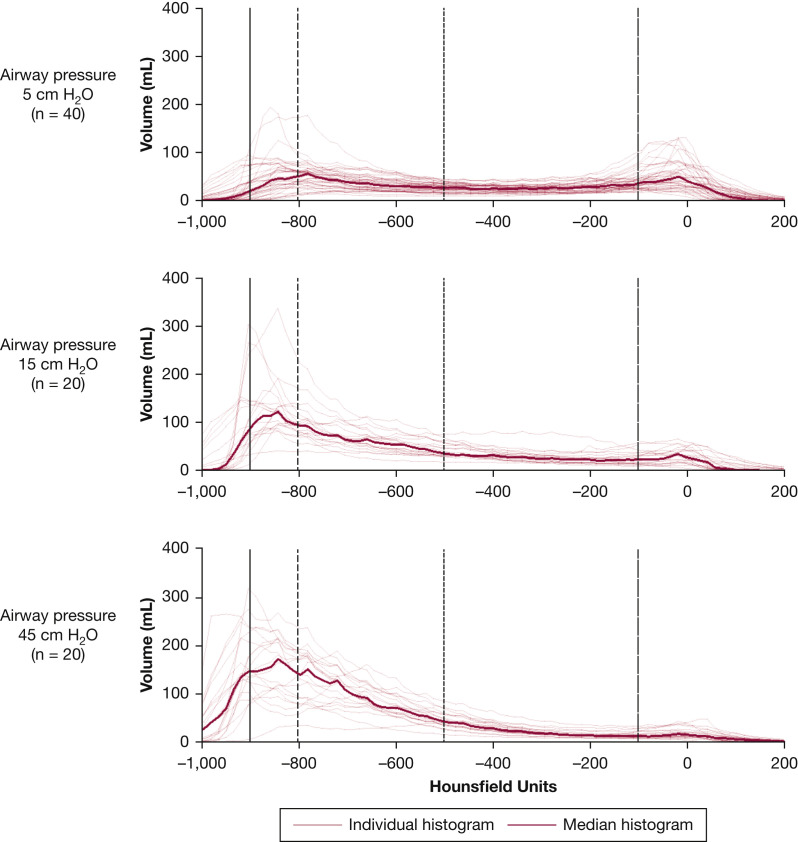

Figure 2.

Lung volume distribution of CT densities at 5, 15, or 45 cm H2O of airway pressure. Forty patients with COVID-19 underwent a lung CT at 5 cm H2O of airway pressure. Twenty of them had a second CT taken at 15 cm H2O, and the other 20 at 45 cm H2O of airway pressure. Herein we show the individual and median distributions of lung volume (tissue and gas) as a function of the physical densities measured in Hounsfield units (HU). With a higher pressure, volumes with density above −100 HU (non-aerated) decreased, as for alveolar recruitment, whereas those with density from −500 to −900 (normally aerated) increased, as for better aeration. Volumes with a density below −900 HU (over-aerated) simultaneously increased, as for hyperinflation. Volumes with a density from −800 to −900 HU, which can become over-aerated after tidal inflation,26 increased as well. The over-aerated compartment in some patients at 5 or 15 cm H2O was larger than in others at 45 cm H2O of airway pressure (see also e-Fig 4).

Figure 3.

Color-coded analysis of lung CT data. Representative CT images taken at the level of carina at 5 and 45 cm H2O of airway pressure from three patients with COVID-19 and very different degrees of recruitment and hyperinflation. Upper panels: original lung CT images, with aeration shown on a continuous grayscale. Lower panels: using an automated encoding system, we attributed a specific color to the non-aerated, poorly aerated, normally aerated, and over-aerated compartments. Left panels: recruitment 457 mL and hyperinflation 5 mL. With 5 cm H2O of PEEP, maximal superimposed pressure was 13.4 cm H2O; compliance 27 mL/cm H2O; Pao2:Fio2 90 mm Hg. C-reactive protein at ICU admission was 20 mg/dL. Central panels: recruitment 347 mL and hyperinflation 661 mL. Maximal superimposed pressure 11.5 cm H2O; compliance 44 mL/cm H2O; Pao2:Fio2 104 mm Hg. C-reactive protein 10 mg/dL. Right panels: recruitment 160 mL and hyperinflation 993 mL. Maximal superimposed pressure 9.4 cm H2O; compliance 60 mL/cm H2O; Pao2:Fio2 80 mm Hg. C-reactive protein 1 mg/dL. None of these patients had a history of COPD or was obese.

From 5 to 45 cm H2O of airway pressure, the total lung volume increased by 2,131 (1,516-2,327) mL. The non-aerated compartment decreased by 351 (161-462) (range, 79-771) mL, and the over-aerated increased by 465 (220-681) (range, 5-1,197) mL. On average, the over-aerated compartment increased by 1.7 (0.5-3.8) mL for a 1-mL decrease of the non-aerated compartment. Hyperinflation exceeded recruitment in 12 (60%) patients. The recruited tissue was 24% (14%-35%) (range, 8%-45%), and the consolidated tissue 16% (9%-23%) of the lung weight with 5 cm H2O of PEEP.

From 5 to 15 cm H2O of airway pressure, changes were similar but smaller. The total lung volume increased by 861 (751-1,077) mL. The non-aerated compartment decreased by 168 (110-202) (range, 50-585) mL, and the over-aerated increased by 121 (63-270) (range, 8-524) mL. The over-aerated compartment increased by 1.1 (0.3-1.7) mL for a 1-mL decrease of the non-aerated compartment. Hyperinflation exceeded recruitment in 11 (55%) patients. The recruited tissue was 11% (9%-14%) (range, 5%-30%).

With a higher airway pressure, recruitment occurred dorsally and hyperinflation ventrally (e-Fig 3).

The hyperinflation-to-recruitment ratio was associated with (i) the maximal superimposed pressure (rho −0.862 and P < .001 in patients studied at 5 and 45 cm H2O; rho −0.838 and P < .001 in those studied at 5 and 15 cm H2O); (ii) the gas volume in the whole lung (rho 0.725 and P < .001; rho 0.787 and P < .001); (iii) the gas volume in the over-aerated compartment (rho 0.784 and P < .001; rho 0.785 and P < .001); and (iv) to some extent, compliance (rho 0.417 and P = .068; rho 0.444 and P = .050) (e-Table 6), all measured with 5 cm H2O of PEEP. It was not associated with Pao 2:Fio 2 with 5 cm H2O of PEEP (rho 0.216 and P = .361; rho 0.390 and P = .090). It was associated with the circulating C-reactive protein measured at ICU admission (rho −0.714 and P < .001; rho −0.741 and P < .001). To summarize, with a higher airway pressure, hyperinflation tended to exceed recruitment in patients with lower superimposed pressure, larger aeration and over-aeration with 5 cm H2O of PEEP, somewhat higher compliance with 5 cm H2O of PEEP, and less inflammation.

Discussion

The main findings of this study can be summarized as follows. In patients with early ARDS caused by COVID-19, ventilated in the supine position, the response to a higher PEEP was variable. Arterial oxygenation usually improved, but compliance and Paco 2 frequently did not even if lung recruitment was large. This disagreement between changes in lung physiology and anatomy can be at least partly explained by the simultaneous occurrence of hyperinflation and overdistention.

The functional response to a higher PEEP suggested a small potential for recruitment. The arterial oxygenation quite constantly improved, but the compliance and the Paco 2 did not. An isolated increase in arterial oxygenation does not necessarily signal large recruitment. Other mechanisms can play a role.6 , 7 With a higher PEEP, the mean arterial pressure decreased, and the arteriovenous oxygen content difference increased as if the cardiac output had decreased. Arterial oxygenation thus may have increased because the nonaerated compartment became less perfused, independently of recruitment (see also e-Fig 5).7 The decrease in compliance with a PEEP > 10 cm H2O also suggests little recruitment with net overdistention.4, 5, 6 Other authors have hypothesized the same based on a very similar response to the PEEP trial in patients with early COVID-19.13 However, those authors did not study the morphological response to a higher PEEP, so that they could not verify their hypothesis as we did.

Discovering with lung CT that patients with early COVID-19 have a very large potential for recruitment came as a surprise. In most14 , 18 , 30 but not all31 other studies on COVID-19, the potential for lung recruitment was small. Herein it was 24% (14%-35%), probably larger than reported in other pulmonary ARDS (16% [9%-25%])28 (see also e-Fig 6). The reasons why our findings differ from previous ones may include our use of CT, the performance of a recruitment maneuver at the beginning of the study, and enrollment of patients soon after their ICU admission, before any later decrease in lung recruitability.14 , 32 , 33 In our study population, the alveolar collapse was almost fully reversible (see also e-Fig 7), and the residual consolidated tissue only 16% (9%-22%) of the lung weight (in other pulmonary ARDS it is 28% [17%-38%]).28

This disagreement between the functional and morphological response to a higher PEEP can be at least partly explained by simultaneous alveolar overdistention.26 , 27 The net effect of PEEP depends on two opposite phenomena: non-aerated units regaining aeration vs already aerated units receiving more gas, up to the point of becoming over-stretched.4 , 34 , 35 As PEEP was increased from 5 to 10 cm H2O, the predominant response seemed to be dorsal recruitment, with less non-aerated tissue, better arterial oxygenation, and better compliance. When PEEP was increased to 15 cm H2O, overdistention of the nondependent lung regions possibly prevailed over any additional dorsal recruitment, with ventral overdistention at the CT and a sharp decline in compliance. Three aspects of our findings should be noted. First, CT is not ideal for measuring overdistention, for the following reasons: hyperinflation can occur without overdistention, as in emphysema36; overdistention may develop without hyperinflation, at the interface between non-aerated and aerated units37; with ARDS, the decrease in CT density due to excessive inflation can be masked by the increased tissue mass.2 With all these limitations, the decrease in compliance of the whole respiratory system (e-Table 5) and of the ventral lung levels (e-Fig 2) suggest that overdistention developed in most patients. Second, end-expiratory lung CT underestimates end-inspiratory hyperinflation. Third, all of these changes occurred with seemingly protective ventilation. In all patients but one, including those with the largest PEEP-induced hyperinflation, driving and plateau airway pressures did not exceed 15 and 30 cm H2O, not even with 15 cm H2O of PEEP.38

Other factors may have contributed to the poor functional response to a higher PEEP in the face of large anatomical recruitment. On one side, the modest improvement in gas exchange could have been due to an abnormal distribution of pulmonary blood flow.21, 22, 23 Arterial oxygenation will not increase much if the recruited alveoli are not well perfused. Conversely, compliance measured during tidal ventilation may not have increased with a higher PEEP because of cyclic recruitment (which increases compliance per se) with a lower PEEP.39 , 40 The relationship between changes in lung aeration and compliance is complex; recruitment should not be estimated only from the latter.41 , 42

The superimposed pressure can be defined as the hydrostatic pressure acting on each lung level. With ARDS, it increases and contributes to the alveolar collapse.2 , 29 , 43 PEEP restores aeration by counteracting the superimposed pressure.43, 44, 45 Considering that in early ARDS due to COVID-19 the lung weight gain is modest (approximately 250 g), the airway pressure needed to recruit the lung (the opening pressure) and keep it open (PEEP) may be quite low. If so, a PEEP > 10 cm H2O will induce significant overdistention.46

Net hyperinflation was associated with C-reactive protein and compliance. With less inflammation, there will be less pulmonary edema, lower superimposed pressure, less alveolar collapse, larger lung gas volume, and higher compliance.5 Changes in pulmonary perfusion will play a major role in the pathogenesis of hypoxemia.21, 22, 23 Possibly, a lower PEEP will be appropriate. By contrast, with more inflammation and lower compliance, the superimposed pressure should be higher and the balance between hyperinflation and recruitment more favorable. A higher PEEP will be more indicated.

Some of the limitations of this study deserve a comment. First, the sample size was based on feasibility limitations caused by the ongoing pandemic. Some subgroup analyses were probably underpowered. Second, during the first wave of the pandemic, we could not enroll all consecutive eligible patients, which may have been a source of bias. Third, we did not include a control group to compare patients with COVID-19 with those with other ARDS, especially for the frequency and severity of overdistention. It may be worth noting that in our study, increasing PEEP from 5 to 15 cm H2O enlarged the over-aerated compartment in all patients, including 19 with no history of COPD (on average by 118 [53-253] mL). By contrast, in a previous study on 32 patients with ARDS of other origins, increasing PEEP from 0 to 15 cm H2O did the same in only 14 (44%), and only in eight (31%) of those with no history of COPD (on average by 25 [19-28] mL).27 Fourth, lung CTs were not taken at 10 cm H2O of PEEP. Our model, with predominant recruitment below that threshold and hyperinflation above it, has to be validated. Fifth, the lung phenotype in COVID-19 changes over time,47 so that our findings may not be valid for later stages of the disease.14 , 32 , 33

Clinical Implications

International guidelines suggest using a higher PEEP to relieve moderate-to-severe hypoxemia caused by COVID-19.11 Accordingly, among 3,988 patients admitted to an ICU in our region (Lombardy, Italy), half were ventilated with a PEEP > 12 cm H2O, and one fourth with a PEEP > 15 cm H2O.48 In retrospect, PEEP on day 1 of ICU admission was an independent risk factor of death: for any 1-cm H2O increase, mortality increased by 4%.48

We did not study the impact of a higher or lower PEEP on clinically relevant outcomes, such as survival or duration of mechanical ventilation. Therefore, our findings do not provide any evidence on how to set the ventilation in patients with COVID-19. Even so, they suggest that the response to a higher PEEP can be hardly predictable; and that some patients might benefit from a lower PEEP, even if their ARDS is moderate or severe. Considering changes in gas exchange, respiratory system mechanics, and lung aeration (measured with the CT or other technique) as a whole may help the clinicians to set PEEP according to the characteristics of every single patient.

In conclusion, in this group of patients with early COVID-19, ventilated in the supine position, the response to a higher PEEP was variable and usually less favorable than expected for the severity of hypoxemia and the potential for lung recruitment. Signs of hyperinflation and overdistention were common.

Take-home Points.

Study Question: What is the response to a higher PEEP in mechanically ventilated patients with early ARDS due to COVID-19?

Results: When PEEP is increased from 5 to 15 cmH2O, oxygenation usually improves but compliance and the Paco 2 do not. Lung CT shows that when the airway pressure is increased from 5 up to 45 cmH2O, recruitment is large but hyperinflation can be even larger.

Interpretation: In patients with early ARDS due to COVID-19, a higher PEEP can induce net hyperinflation with overdistention.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: A. P. takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis. A. P. contributed to the conception and design of the study, analysis, and interpretation of the data and wrote the manuscript. A. S. contributed to the conception and design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and revised the manuscript. F. P., C. C., M. Cr. contributed to the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data and revised the manuscript. M. F., G. E. I., L. C., and E. L. contributed to the collection of the data and revised the manuscript. G. P. contributed to the analysis of the data and revised the manuscript. P. C., A. A., and M. Ce. contributed to the conception of the study, interpretation of the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved this final version of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: None declared.

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Other contributions: We are grateful to all nurses, physicians, and other health care professionals who helped us perform this study. The following colleagues contributed to the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data: Francesca Collino, MD, Elena Costantini, MD, Francesca Dalla Corte, MD, Maxim Neganov, MD, and Valerio Rendiniello, NP (Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care Units, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center—IRCCS, Rozzano, Milan, Italy); Nicolò Martinetti, MD, and Luca Pugliese, MD (Department of Biomedical Sciences, Humanitas University, Pieve Emanuele, Milan, Italy).

Additional information: The e-Appendix, e-Figures, and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: Support was provided solely from institutional or departmental sources.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Ashbaugh D.G., Bigelow D.B., Petty T.L., Levine B.E. Acute respiratory distress in adults. Lancet. 1967;2(7511):319–323. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(67)90168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gattinoni L., Caironi P., Pelosi P., Goodman L.R. What has computed tomography taught us about the acute respiratory distress syndrome? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(9):1701–1711. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.9.2103121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gattinoni L., Pesenti A., Bombino M., et al. Relationships between lung computed tomographic density, gas exchange, and PEEP in acute respiratory failure. Anesthesiology. 1988;69(6):824–832. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198812000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gattinoni L., Caironi P., Cressoni M., et al. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(17):1775–1786. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gattinoni L., Pesenti A., Avalli L., Rossi F., Bombino M. Pressure-volume curve of total respiratory system in acute respiratory failure: computed tomographic scan study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136(3):730–736. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.3.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caironi P., Gattinoni L. How to monitor lung recruitment in patients with acute lung injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13(3):338–343. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32814db80c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dantzker D.R., Lynch J.P., Weg J.G. Depression of cardiac output is a mechanism of shunt reduction in the therapy of acute respiratory failure. Chest. 1980;77(5):636–642. doi: 10.1378/chest.77.5.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briel M., Meade M., Mercat A., et al. Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(9):865–873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amato M.B., Meade M.O., Slutsky A.S., et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):747–755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1410639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan E., Del Sorbo L., Goligher E.C., et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/Society of Critical Care Medicine clinical practice guideline: mechanical ventilation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(9):1253–1263. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0548ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alhazzani W., Møller M.H., Arabi Y.M., et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):854–887. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chauvelot L., Bitker L., Dhelft F., et al. Quantitative-analysis of computed tomography in COVID-19 and non COVID-19 ARDS patients: a case-control study. J Crit Care. 2020;60:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiumello D., Busana M., Coppola S., et al. Physiological and quantitative CT-scan characterization of COVID-19 and typical ARDS: a matched cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(12):2187–2196. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06281-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ball L., Robba C., Maiello L., et al. Computed tomography assessment of PEEP-induced alveolar recruitment in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03477-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beloncle F.M., Pavlovsky B., Desprez C., et al. Recruitability and effect of PEEP in SARS-Cov-2-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00675-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grieco D.L., Bongiovanni F., Chen L., et al. Respiratory physiology of COVID-19-induced respiratory failure compared to ARDS of other etiologies. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):529. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03253-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauri T., Spinelli E., Scotti E., et al. Potential for lung recruitment and ventilation-perfusion mismatch in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome from coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(8):1129–1134. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan C., Chen L., Lu C., et al. Lung recruitability in COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: a single-center observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(10):1294–1297. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0527LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perier F., Tuffet S., Maraffi T., et al. Effect of positive end-expiratory pressure and proning on ventilation and perfusion in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(12):1713–1717. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202008-3058LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grasso S., Mirabella L., Murgolo F., et al. Effects of positive end-expiratory pressure in “high compliance” severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(12):e1332–e1336. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grasselli G., Tonetti T., Protti A., et al. Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicentre prospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(12):1201–1208. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30370-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herrmann J., Mori V., Bates J.H.T., Suki B. Modeling lung perfusion abnormalities to explain early COVID-19 hypoxemia. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4883. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18672-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel B.V., Arachchillage D.J., Ridge C.A., et al. Pulmonary angiopathy in severe COVID-19: physiologic, imaging, and hematologic observations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(5):690–699. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1412OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ARDS Definition Task Force. Ranieri V.M., Rubenfeld G.D., et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cressoni M., Gallazzi E., Chiurazzi C., et al. Limits of normality of quantitative thoracic CT analysis. Crit Care. 2013;17(3):R93. doi: 10.1186/cc12738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puybasset L., Gusman P., Muller J.C., Cluzel P., Coriat P., Rouby J.J. Regional distribution of gas and tissue in acute respiratory distress syndrome. III. Consequences for the effects of positive end-expiratory pressure. CT Scan ARDS Study Group. Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(9):1215–1227. doi: 10.1007/s001340051340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nieszkowska A., Lu Q., Vieira S., Elman M., Fetita C., Rouby J.J. Incidence and regional distribution of lung overinflation during mechanical ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1496–1503. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000130170.88512.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coppola S., Froio S., Marino A., et al. Respiratory mechanics, lung recruitability, and gas exchange in pulmonary and extrapulmonary acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(6):792–799. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pelosi P., D’Andrea L., Vitale G., Pesenti A., Gattinoni L. Vertical gradient of regional lung inflation in adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(1):8–13. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.1.8111603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haudebourg A.F., Perier F., Tuffet S., et al. Respiratory mechanics of COVID-19- versus non-COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):287–290. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1226LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smit M.R., Beenen L.F.M., Valk C.M.A., et al. Assessment of lung reaeration at 2 levels of positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with early and late COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Thorac Imaging. 2021;36(5):286–293. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kummer R.L., Shapiro R.S., Marini J.J., Huelster J.S., Leatherman J.W. Paradoxically improved respiratory compliance with abdominal compression in COVID-19 ARDS. Chest. 2021;160(5):1739–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rezoagli E., Bastia L., Grassi A., et al. Paradoxical effect of chest wall compression on respiratory system compliance: a multicenter case series of patients with ARDS, with multimodal assessment. Chest. 2021;160(4):1335–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dambrosio M., Roupie E., Mollet J.J., et al. Effects of positive end-expiratory pressure and different tidal volumes on alveolar recruitment and hyperinflation. Anesthesiology. 1997;87(3):495–503. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199709000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rouby J.J., Lu Q., Goldstein I. Selecting the right level of positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(8):1182–1186. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.8.2105122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crotti S., Mascheroni D., Caironi P., et al. Recruitment and derecruitment during acute respiratory failure: a clinical study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(1):131–140. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.1.2007011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cressoni M., Cadringher P., Chiurazzi C., et al. Lung inhomogeneity in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(2):149–158. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1567OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terragni P.P., Rosboch G., Tealdi A., et al. Tidal hyperinflation during low tidal volume ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(2):160–166. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-915OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jonson B., Richard J.C., Straus C., Mancebo J., Lemaire F., Brochard L. Pressure-volume curves and compliance in acute lung injury: evidence of recruitment above the lower inflection point. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(4 Pt 1):1172–1178. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9801088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen L., Del Sorbo L., Grieco D.L., et al. Potential for lung recruitment estimated by the recruitment-to-inflation ratio in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(2):178–187. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201902-0334OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiumello D., Marino A., Brioni M., et al. Lung recruitment assessed by respiratory mechanics and computed tomography in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: what is the relationship? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(11):1254–1263. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1413OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amato M.B., Santiago R.R. The recruitability paradox. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(11):1192–1195. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201601-0178ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cressoni M., Chiumello D., Carlesso E., et al. Compressive forces and computed tomography-derived positive end-expiratory pressure in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2014;121(3):572–581. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gattinoni L., D’Andrea L., Pelosi P., Vitale G., Pesenti A., Fumagalli R. Regional effects and mechanism of positive end-expiratory pressure in early adult respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA. 1993;269(16):2122–2127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gattinoni L., Pelosi P., Crotti S., Valenza F. Effects of positive end-expiratory pressure on regional distribution of tidal volume and recruitment in adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(6):1807–1814. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.6.7767524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Protti A., Greco M., Filippini M., et al. Barotrauma in mechanically ventilated patients with Coronavirus disease 2019: a survey of 38 hospitals in Lombardy, Italy. Minerva Anestesiol. 2021;87(2):193–198. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.20.15002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi H., Han X., Jiang N., et al. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):425–434. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grasselli G., Greco M., Zanella A., et al. Risk factors associated with mortality among patients with COVID-19 in intensive care units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1345–1355. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.