Abstract

Comorbid depression and insomnia are ubiquitous mental complaints among women going through the perimenopausal stage of life and can result in major decline in quality of life. Antidepressive agents combined with/without hypnotics, and/or hormone therapy are currently the most common treatment for perimenopausal depression (PMD) and insomnia (PMI). Balancing the benefits of these pharmacotherapies against the risk of adverse events (AEs) is a difficult task for both clinicians and women. There has been a growing body of research regarding the utilization of acupuncture for treatment of PMD or PMI, whereas no studies of acupuncture for comorbid PMD and PMI have appeared. In this review, we summarize the clinical and preclinical evidence of acupuncture as a treatment for PMD or PMI, and then discuss the potential mechanisms involved and the role of acupuncture in helping women during this transition. Most clinical trials indicate that acupuncture ameliorates not only PMD/PMI but also climacteric symptoms with minimal AEs. It also regulates serum hormone levels. The reliability of trials is however limited due to methodological flaws in most studies. Rodent studies suggest that acupuncture prolongs total sleep time and reduces depression-like behavior in PMI and PMD models, respectively. These effects are possibly mediated through multiple mechanisms of action, including modulating sex hormones, neurotransmitters, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis/hypothalamic-pituitary-ovary axis, oxidative stress, signaling pathways, and other cellular events. In conclusion, acupuncture is a promising therapeutic strategy for comorbid depression and insomnia during perimenopause. Neuroendocrine modulation is likely to play a major role in mediating those effects. High-quality trials are required to further validate acupuncture’s effectiveness.

Keywords: acupuncture, perimenopause, insomnia, depression, comorbid, mechanisms

Background

Perimenopause is a universal phenomenon that marks a mid-life transition from fertility to infertility in women’s lives.1 It is a stage during which women are particularly vulnerable to the onset of depression,2–4 even without any previous history of depressive disorders.2 A large quantity of studies also link both insomnia and vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and night sweating) to perimenopausal depression (PMD),3,5,6 while insomnia is correlated more strongly and consistently with depression than vasomotor symptoms are.7–9 The prevalence of comorbid depression and insomnia in perimenopause is approximately 31.5%.9

The Comorbidity of Perimenopausal Insomnia and Depression is More Than a “Domino” Effect

The interaction between depression and insomnia, and its contribution to psychosomatic impairments, is clear.10 In comparison to women without sleep disturbances, women with sleep disturbance are 10 times more likely to experience depression; and women with depression are more vulnerable to insomnia, particularly waking during the night and having difficulty falling asleep again.11,12 In various insomnia patterns, depression is highly associated with difficulty falling asleep and waking up earlier than desired.10 Women in the menopausal transition are at increased risk for sleep-disordered breathing, which can also contribute to both depressed mood and poor sleep.3 In light of the actigraphy data, perimenopausal insomniacs with comorbid depression show longer sleep onset latency, shorter sleep duration, and lower sleep efficiency (but not number of awakenings or wakefulness after sleep onset), in comparison to women with insomnia only.10 Depression and insomnia are not only a mental burden for perimenopausal women but they also increase the difficulty of treating menopause-related somatic issues such as cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis.13 Anticipation of symptom self-healing might be futile as untreated PMD can increase medical morbidity after menopause, including risks of endocrine and cardiovascular disease.14

It is challenging to find an established theoretical basis for interpreting intertwined phenomenon of insomnia and depression as women transit menopause, although the two are commonly co-encountered.4,11 Two kinds of “domino” theory are sometimes asserted to partially explain this bidirectionality, or even link this bidirectionality to vasomotor symptoms: 1) PMD due to climacteric vasomotor symptoms or other psychosocial risk factors decreases sleep quality and quantity and 2) frequent night hot flushes may be tied to disrupted sleep patterns, and in turn, trigger the development of depressive symptoms.4,5 The complicated interrelationships between these three symptoms (depression, insomnia, and vasomotor complaints), however, may far exceed the “domino” explanation, because not all women with hot flushes develop depression, insomnia, or both; and many perimenopausal women suffer from depression and/or insomnia in the absence of hot flushes.10

Current Management Strategies for Comorbid Depression and Insomnia During Perimenopause

It is imperative for women in mid-life to find effective strategies to manage comorbid depression and insomnia, and maximize their well-being. Because of the co-occurrence or overlap, interdependent and interactional relationship,6,15 management of insomnia is also recommended as part of treatment for PMD, in “Guidelines for the Evaluation and Treatment of Perimenopausal Depression” issued by the Board of Trustees for The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and Mood Disorders Task Force of the National Network of Depression Centers (NNDC).6 According to NAMS and NNDC, antidepressants and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are the front-line antidepressant treatments for PMD.6 However, antidepressant medications have some relatively minor adverse events (AEs) that include but are not limited to dryness of mouth, digestive upsets, drowsiness, and fatigue, and some more major AEs such as rapid weight gain and sexual dysfunction.5,16–18 Similarly, sedatives and hypnotics have side effects that patients may find uncomfortable19 and are not recommended for longer term treatment of insomnia. CBT is highly recommended for the treatment of both depression and insomnia, but an impediment to its wider utilization is a lack of suitably trained psychologists.20 Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) can be an effective treatment for perimenopausal syndrome, while it is not FDA-approved to treat perimenopausal mood disturbance.6

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has many proponents and supporters3 and has been sought to treat depression16 and insomnia19 associated with perimenopause. As previously reported, during peri- to post-menopause up to 50% of the women worldwide seek assistance from CAM approaches, including herbal medicine, yoga, massage therapy, dietotherapy, as well as acupuncture for symptomatic relief.3,21 Acupuncture has a long tradition of usage for the treatment of various menopause-related symptoms, including PMI and PMD, dating back thousands of years.22 Its clinical efficacy has been investigated for natural menopause and chemical-/surgery-induced menopause.22 It has also been reported that menopausal women sustaining insomnia as a major complaint tend to select CAM approaches, particularly body therapies, as their first choice of remedy.23,24 A menopausal epidemiological study carried out in the US indicated that in women who primarily used alternative therapies including acupuncture to manage menopause-related depression, 1.0% were completely symptom free, 84.6% made symptoms get a little to a lot better, 12.5% showed no change in symptoms, and 1.9% reported the worsening of symptoms, which was slightly less effective than the conditions in women who primarily used anti-depressive or anti-anxiety agents for menopause-related depression (5.6% were completely symptom free, 88.6% made symptoms get a little to a lot better, 3.9% showed no change in symptoms, and 1.9% reported the worsening of symptoms).25 However, due to the limited evidence and uncertainty about its effectiveness and mechanism of action in physiological terms, acupuncture is still striving for general scientific recognition and support.

This review aims to summarize and assess existing clinical and preclinical evidence of acupuncture as a treatment for perimenopausal insomnia and depression, as well as discuss the potential mechanisms involved. We aim to provide an evidence-base for decision-making for clinical practitioners to recommend (or for perimenopausal to women select) acupuncture as a potential therapy.

Effects and Safety of Acupuncture on Depression and Insomnia

Acupuncture is one of the simplest, popular, and safest CAM procedures.19,26,27 It is derived from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and has a history of use in medicine of at least 4000 years under the influence of oriental philosophical theories.28 It is a clinical treatment modality in which targeted proposed specific locations of the body, the acupuncture points (also called acupoints) have thin, solid, metallic needles inserted deeply for therapeutic purposes. The therapeutic efficacy is more effectively manifested when the pierced needles are manipulated manually with slight rotation (back-and-forth motion) and/or pistoned (up-and-down motion) or other complex combinations (manual acupuncture, MA), or are stimulated by the electric current via an impulse generator (electro-acupuncture, EA).27–30 As illustrated in neuroimaging reports, acupuncture can cause a wide array of central nervous system (CNS) responses involving the hippocampus, amygdala, cerebellum, hypothalamus, and other limbic structures.31 Dysfunction or disorder in these cerebral regions has been previously implicated in the development of depression32,33 and/or insomnia.34,35 Both clinical and basic studies indicate these two forms of acupuncture (MA and EA) are different with regard to outcomes and underlying physiological mechanisms, it is however difficult to conclude which one is more efficacious.29 Furthermore, patterns of usage of MA or EA usually vary by condition treated, stimulus demand, and/or acupuncturist preference.29

Patients are attracted to acupuncture in part by its reputation for being low-risk. Several prospective surveys with large sample sizes have suggested that acupuncture-related AEs mainly involve minor local reactions at the site of needling, such as bruising, pain, or minor bleeding, and the incidence of these events is generally very low (no more than 3%).36,37 No serious AEs requiring hospital visits or resulting in permanent disability or death have been reported from acupuncture.36,37 Twelve prospective studies involving several Asian and European countries validated that the incidence of the acupuncture-related serious AEs (ie, life threatening, hospital admission required or prolongation of existing hospital stay, persistent or significant disability or incapacity, death, etc) was estimated to be 0.55 per 10,000 patients, and 0.05 per 10,000 treatment sessions.32,38 Given its non-pharmacological basis, acupuncture also obviates the concerns with respect to toxicity and AEs that commonly occur when using hypnotics/sedatives, such as hangover, tolerance, increased alertness, and even endocrinological, hematological or cardiovascular events,39 and concerns regarding common side effects of contemporary antidepressive agents, such as dry mouth, cardiovascular/gastrointestinal side effects, seizure, bleeding, sexual dysfunction, weight gain, and even suicidality.40 Acupuncture also does not increase the metabolic burden of the liver and kidney. It is thus a potentially safe, promising and attractive remedy in the management of comorbid depression and insomnia associated with perimenopause. But, the question remains as to whether it is really effective?

As of March 2019, there were at least 31 systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses (SRs/MAs) regarding acupuncture treatment for depression.41 As of September 2018, there were at least 34 SRs/MAs regarding acupuncture treatment for insomnia.30 Although the included primary randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are less than well-powered and have some methodological flaws, the available evidence is in favor of acupuncture’s effectiveness and safety, and supports it as a monotherapy or adjuvant therapy for patients with depression or insomnia, particularly those who are intolerant to Western medications.30,41 In China, acupuncture has even been added as a routine remedy in the latest Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Insomnia formulated by the Chinese Sleep Research Society (CSRS).30 The clinical guidelines issued by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Depression Work Group recommended acupuncture as a third-line treatment with “Level 2 Evidence” for the adjunctive treatment of mild-to-moderate depression.41,42

How is Acupuncture for Perimenopausal Depression and Insomnia Conceptualised in TCM

TCM looks upon human life as a holistic, dynamic, spiritual, and functional unity, and the development of disease mainly as the result of a disordered state of the human functional balance (imbalance in the forces between Yin and Yang).26,28,43 Therefore, the basic protocol of preventing and/or treating disease in TCM is to restore the imbalance state and achieve Yin-Yang harmony via various remedies (eg, herbal medicine, acupuncture, moxibustion, Tui-na, etc) depending upon the individual and the malady.26,28,43

In clinical setting, acupuncture is ubiquitously applied based on the basic theory of TCM, which emphasizes the concept of “syndrome pattern”.44 “Treatment based on Syndrome Differentiation” is the essential principle of TCM. That is, patients are classified into different TCM syndrome patterns according to their clinical symptoms and signs, and then corresponding treatments, including acupuncture, are prescribed.44,45 According to the concept and theory of TCM gynecology, all perimenopausal diseases and disorders including PMI/PMD can be classified into the main category of “Juejing-Qianhou-Zhuzheng” (绝经前后诸症, meaning “symptoms and signs associated with perimenopause”, which is similar to “perimenopausal syndrome” in Western medicine) for treatment.46 In light of different symptoms, patients with PMI/PMD are generally further divided into different syndrome patterns within the scope of perimenopausal syndrome, and then receive corresponding TCM therapies. This strategy is the embodiment and process of “Treatment based on Syndrome Differentiation”. PMI/PMD is usually classified into different syndrome patterns in different published studies.47,48 Based on bibliometric analysis,47,48 we listed the top six syndromes of each of these two disorders and the proportion of patients in each pattern, respectively (see Table 1; organs in the syndrome pattern correspond to the TCM understanding). It is interesting to identify that in three out of nine patterns, PMI and PMD overlap. The pattern with the highest proportion of patients in both conditions is consistent, that is, the pattern of “depression of Liver and deficiency of kidney”. Given that TCM prescriptions (eg, acupuncture, herbal medicine, etc) are highly dependent on patterns, establishing standardized pattern classifications of PMI/PMD is essential for research and improved clinical practice.

Table 1.

Common TCM Syndrome Patterns of PMI and PMD

| Syndrome Patterns | Major Symptoms | Tongue | Pulse | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMI | PMD | ||||

| Depression of liver and deficiency of kidney | Insomnia or dreamful sleep, depressed mood, fatigue, chest distress and preference for sighing, hot flushes and sweating, frequent urination or dribbling urination | Red tongue with little coating | Stringy and thready, or stringy and rapid | 60.78% | 30.42% |

| Liver depression and spleen deficiency | Depression or irritability, poor sleep, poor appetite, abdominal distension, loose stool | White coated tongue | Stringy and slow | 24.02% | – |

| Stagnation of Qi due to depression of liver | Depression or irritability, preference for sighing, hypochondrium distress and/or pain, distending pain of breasts | Thin whitish coating of the tongue | Stringy | – | 18.80% |

| Imbalance between heart-Yang and kidney-Yin | Irritability and insomnia, palpitation, dizziness and tinnitus, loss of memory, dry mouth, soreness and weakness of waist and knees | Red tongue with little coating | Thready and rapid | – | 13.46% |

| Spleen–kidney Yang deficiency | Insomnia due to nocturia, soreness and weakness of waist and knees, chilly sensation and the cold limbs, diarrhea before dawn or loose stools, edema in the extremities | Pale and slight corpulent tongue with whitish and slippery fur | Deep and retarded without strength | 4.31% | – |

| Deficiency of both kidney Yin and kidney Yang | Poor sleep, sometimes hot flushes and sweating and sometimes chilly sensation and the cold limbs, soreness and weakness of waist and knees, dizziness and tinnitus | Pale tongue with thin coating | Stringy and thready | 4.31% | – |

| Heart-Gallbladder Qi deficiency | Palpitation, timidity, feeling fearful, difficulty in falling asleep, tendency to sleep lightly, nightmares, depressed mood, short of breath, spontaneous perspiration | Pale tongue with whitish coating | Stringy and thready | 3.70% | 6.72% |

| Heart–spleen deficiency | Insomnia, dreamful sleep, worry beyond measure, palpitation, poor appetite, loose stool, fatigue, sallow complexion, loss of memory | Pale tongue with whitish coating | Thin and weak | 2.87% | 6.11% |

| Hyperactivity of fire due to Yin deficiency | Vexation, irritable and depressed mood, dry mouth, tidal reddening of the cheeks, dysphoria in chest palms-soles | Red tongue with little coating | Stringy and rapid | – | 4.65% |

Table 1 is not a direct quote from any paper, but is compiled by us from data in two published papers (Ref 47 & 48 of this manuscript); Similarly, Table 3 is compiled by us from data in two published papers (Ref 19 & 50 of this manuscript); The rest of the tables and figures are original and do not require reference. 47 and 48.

Despite a lack of standardized pattern classification, perimenopausal symptoms including PMI/PMD are closely related to liver and kidney in TCM clinical practice.47,49 Hence, herbal medicines (or acupoints) associated with regulating liver (or Liver Meridian of Foot-Jueyin) and kidney (or Kidney Meridian of Foot-Shaoyin) are often selected for treating depression and insomnia associated with perimenopause.47,49 Smoothing liver (smooths liver and regulates Qi) and nourishing kidney (nourishes kidney and enriches essence) are regarded as the general principles for perimenopausal disorders.47,49

Evidence from Clinical Trials

Does the existing clinical evidence support acupuncture as a safe and effective therapy for comorbid PMI and PMD, and is the evidence reliable? To answer this question, a comprehensive literature search with no restrictions for research types was carried out. Unfortunately, no RCTs, cohort studies or case studies within this theme were retrieved, reflecting a significant research and practice gap. Our team thereby is currently carrying out an RCT focusing on this theme. This trial has been registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (No. ChiCTR2100043054), and the results are expected to be published in 2022. However, we retrieved many RCTs and some SRs/MAs focusing on acupuncture treatment for PMD alone or PMI alone. Those SRs/MAs involved several modified modalities of acupuncture for which mechanisms of action differ from those for MA/EA and were not discussed in this review; therefore, only eligible original RCTs in those SRs/MAs were extracted.

Our team has published two SRs/MAs19,50 within related fields (15 RCTs in SR/MA of PMI; 25 RCTs in SR/MA of PMD) where we covered our retrieval strategy in detail (retrieval in 2020), as well as our quality evaluation and interpretation of the evidence. Based on updated retrieval (July 2021), we have included more RCTs recently published (22 RCTs of PMI; 25 RCTs of PMD). The critical information and major findings of each RCT were extracted and summarized in Table 2. The results of meta-analyses cited from our SRs/MAs are displayed in Table 3, and detailed analysis process can be referred to in our published articles.19,50 Given that this review is not an SR, a narrative summary on the findings followed by comments on the methodology and implications for future research of these studies is provided. We expect that these summaries will help clinicians and policymakers judge the role of acupuncture, and its potential and feasibility for the management of depression and insomnia associated with perimenopause.

Table 2.

Summary of Clinical Trials Investigating the Effects and Safety of Acupuncture on PMI and PMD

| Author/Year | Study Groups/No. of Participants | Disease (Diagnostic System) | TCM Syndrome Pattern | Acupuncture Interventions | Acupoints | Controls | Outcome Measures | Results (Compared with the Control Group) at Post-Treatment | Follow-Up | Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fu et al 201751 | - MA/n=37 - placebo-MA/n=37 |

PMI (ICSD-3) | NR | 20 min/day for 10 sessions | BL18, BL23, GB25, LR14 | Streitberger placebo-needle control | PSQI, ISI, PSG (SOL, TST, WASO, SE, Arl, N1%, N2%, N3%, REM%) | (i) Lower PSQI and ISI in MA group (ii) Shorter SOL and WASO, longer TST, higher SE, lower Arl, lower N1%, and higher REM% in MA group; no differences in N2% and N3% between two groups |

No follow-up | - MA/n=0 - placebo-MA/n=4 (worsening of insomnia) |

| Wang 201552 | - EA/n=30 - placebo-EA/n=30 |

PMI (ICSD-3) | NR | 30 min/day, 3 days/week for 8 weeks | BL15, BL18, BL23, CV3, CV4, CV6, CV12, EX-HN3, GV3, GV4, GV14, GV20, HT7, KI3, LR3, PC6, SP6, ST36 | Streitberger placebo-needle control | PSQI, MRS, Men-QoL | No differences in PSQI, MRS and MEN-QoL between two groups | (1) No difference in PSQI and Men-QoL between two groups at 4-week follow-up (2) Lower MRS in EA group at 4-week follow-up |

No adverse events |

| Lin et al 201753 | - MA/n=33 - waitlist-control/n=32 |

PMI (CCMD-3, CDTE-TCM) | NR | 30 min/day, 3 days/week for 4 weeks | CV4, CV6, CV12, EX-HN3, GV20, GV24, HT7, PC6, SP6, ST36 | Waitlist | PSQI, KI | Lower PSQI and KI in MA group | No follow-up | NR |

| Li et al 2020a54 | - EA/n=42 - placebo-EA/n=42 |

PMI (ICSD-3) | Kidney Yin/Yang deficiency | − 30 min/day for 18 days (3 days/week for 4 weeks + 2 day/week for 2 weeks + 1 day/week for 2 weeks) - continuous wave, 2.5 Hz, 4–5 mA |

BL23, CV4, CV6, EX, EX-HN3, GV4, GV20, GV24, HT7, KI3, KI7, SP6 | Streitberger placebo-needle control | PSQI, MEN-QoL, Actigraphy (TST, WASO, SE, ATs, AA), ISI, SAS, SDS | (i) Lower PSQI, ISI, MEN-QoL, SAS in EA group; no differences in SDS between two groups (ii) Longer TST, higher SE, and less AA in EA group; no differences in ATs and WASO between two groups |

Lower PSQI and Men-QoL in EA group at 4- and 12- week follow-ups | - EA/n=2 [mild bleeding (1); mild pain (1)] - placebo-EA/n=1 (mild pain) |

| Wang et al 201555 | - MA/n=33 - sham-MA/n=33 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | NR | 30 min/day, 3 days/week for 8 weeks | KI6, LU7, PC6, SP4 | Sham-MA [shallow puncture (2.5–5 mm), no De-qi, no retention of the needle] | SDS, Men-QoL | Lower SDS and Men-QoL in MA group | (i) Lower SDS in MA group at 4-week follow-up (ii) no difference in Men-QoL between two groups |

NR |

| Li 2015a56 | - EA/n=30 - sham-EA/n=30 - Escitalopram/n=30 |

PMD (ICD-10) | NR | − 30 min/day, 3 days/week for 12 weeks - dense-sparse wave, 10/50 Hz, 0.5–1 mA |

CV4, EX-CA1, EX-HN3, GV20, LI4, LR3, SP6, ST25 | (i) Sham-MA [shallow puncture (3 mm), no De-qi, no current output] (ii) Escitalopram 10 mg/day for 12 weeks |

HAMD, Men-QoL, FSH, E2, LH | (i) Lower HAMD and Men-QoL in EA group, compared with sham-EA; no differences in HAMD and Men-QoL between EA and escitalopram groups (ii) No differences in FSH, LH and E2 levels between two groups (vs sham-EA or vs escitalopram) |

(i) Lower HAMD in EA group in 4-week and 12-week follow-ups (vs sham-EA); no difference in HAMD between EA and escitalopram groups in 4-week and 12-week follow-ups (ii) Lower Men-QoL in EA in 4-week follow-up (vs sham-EA or vs escitalopram); Men-QoL from low to high (EA < escitalopram < sham-EA) at 8-week and 12-week follow-ups |

- EA/n=2 (hematoma) - sham-EA/n=0 - Escitalopram/n=25 [fatigue (17); headache (2); sleep disturbance (7); dizziness (7); palpitation (4); sweating (10); dry mouth (14); constipation (8)] |

| Ma 201797 | - EA/n=37 - Progynova + Medroxyprogesterone acetate/n=36 |

PMI (CCMD-2-R) | NR | − 30 min/day, 3 days/week for 12 weeks - sparse-dense wave, 2/15 Hz |

CV4, EX-CA1, EX-HN3, HT7, SP6, ST25 | A total of 3 treatment cycles. Each treatment cycle includes Progynova 1mg daily for 21 consecutive days (with Medroxyprogesterone acetate 10mg daily added from day 14 to day 21) and then stop medication for 7 days | PSQI, KI, Men-QoL, FSH, E2 | (i) Lower PSQI in EA group; no differences in KI and Men-QoL between two groups (ii) No differences in FSH level between two groups; higher E2 level in EA group |

(i) Lower PSQI in EA group at 12-week follow-up (ii) No differences in KI MENQOL, and FSH and E2 levels between two groups |

- EA/n=3 [hematoma (2); mild dizziness (1)] - Progynova + Medroxyprogesterone acetate/n=4 [breast tenderness (2); mild headache (1); colporrhagia (1)] |

| Chen et al 201357 | - EA/n=38 - Alprazolam/n=32 |

PMI (DSM-IV) | NR | − 30 min/day for 20 days (7 days off every 10 days) - continuous wave, 0.7 Hz |

EX, GV20, HT7, KI3, KI7, KI10, LR3, PC6, SP6, SP9, SP10 | Alprazolam 0.4 mg/day for 20 days | AIS | Lower AIS in EA group | No follow-up | - EA/n=0 - Estazolam/n=8 (development of drug dependence after treatment) |

| Luo 202058 | - MA/n=30 - Estazolam/n=30 |

PMI (CCMD-3, CDTE-TCM) | Incoordination between heart and kidney | 30 min/day, 5 days/week for 12 weeks | BL15, BL23, BL62, EX, EX-HN1, GV20, KI3, KI6, PC6, SP6 | Estazolam 1 mg/day, 3 days/week for 12 weeks | PSQI | No differences in PSQI between two groups | No follow-up | - MA/n=0 - Estazolam/n=5 [dizziness (2); nausea and vomiting (2); skin rashes (1)] |

| Du et al 201759 | - EA/n=41 - Estazolam/n=41 |

PMI (CCMD-3) | NR | − 30 min/day, 6 days/week for 4 weeks - continuous wave, >50 Hz |

PC6, SP6, Sishenzhen (1.5 Cun apart from GV20), Dingshenzhen (0.5 Cun up to EX-HN3, and 0.5 Cun up to GB14) | Estazolam 1 mg/day, 7 days/week for 4 weeks | PSQI, KI, WHOQOL-BREF, FSH, E2 | (i) Lower PSQI and KI, and higher WHOQOL-BREF in EA group (ii) Higher E2 levels, and lower FSH levels in EA group |

No follow-up | - EA/n=6 (mild tension before EA) - Estazolam/n=26 [dizziness (26); daytime sleepiness (26)] |

| Kang 201560 | - MA/n=31 - Estazolam/n=33 |

PMI (CCMD-3) | Heart and Gallbladder Qi deficiency | 40 min/day, 6 days/week for 4 weeks | EX, EX-HN1, GB13, GB15, GV16, GV20, GV24, scalp acupoint (1 Cun up to GB15) | Estazolam 1 mg/day, 7 days/week for 4 weeks | PSQI, KI | Lower PSQI and KI in MA group | No follow-up | - MA/n=0 - Estazolam/n=1 (mild nausea) |

| Lai 201661 | - MA/n=34 - Eszopiclone/n=33 |

PMI (CCMD-3) | Incoordination between heart and kidney | 30 min/day, 6 days/week for 3 weeks (acupuncture on specific time) | BL62, KI6, LU7, SI3 | Eszopiclone 3 mg/day, 7 days/week for 3 weeks | PSQI, KI | (i) Lower KI in MA group; no differences in PSQI between two groups | No follow-up | - MA/n=2 (hematoma) - Eszopiclone/n=3 [dizziness (1); dry mouth (2)] |

| Li 201462 | - MA/n=120 - Estazolam/n=120 |

PMI (CCMD-3) | NR | 30 min/day for 30 days | SP6, SP8, Shenguan (Tianhuangfuxue) | Estazolam 2 mg/day for 30 days | PSQI | Lower PSQI in MA group | No follow-up | NR |

| Li et al 2018a63 | - MA/n=60 - Alprazolam/n=62 |

PMI (CDTE-TCM) | NR | 30–40 min/day, 5 days/week for 9 weeks | BL13, BL15, BL17, BL18, BL20, BL23, HT7 | Alprazolam 0.4–0.8 mg/day, 7 days/week for 9 weeks | PSQI, FSH, E2, LH | (i) Lower PSQI in MA group (ii) Higher E2 levels, and lower FSH and LH levels in MA group |

Follow-up 30 days; NR for valid data | NR |

| Lu et al 201449 | - MA/n=52 - Estazolam/n=52 |

PMI (CCMD-3, ICD-10) | NR | 30 min/day for 30 days | CV12, EX-HN1, GB20, GV20, HT7, LR3, LR14, SP6, SP15 | Estazolam 1 mg/day for 30 days | PSQI | Lower PSQI in MA group | No follow-up | NR |

| Ma 201464 | - EA/n=45 - Estazolam/n=45 |

PMI (CCMD-2) | Any TCM syndrome pattern according to CDTE-TCM | − 30 min/day, 3 days/week for 4 weeks - continuous wave, >50 Hz |

PC6, SP6, Sishenzhen (1.5 Cun apart from GV20), Dingshenzhen (0.5 Cun up to EX-HN3, and 0.5 Cun up to GB14) | Estazolam 1 mg/day, 7 days/week for 4 weeks | PSQI, HAMD | Lower PSQI and HAMD in EA group | No follow-up | No adverse events |

| Qin 201865 | - MA/n=34 - Estazolam/n=33 |

PMI (CCMD-3, ICD-10) | Deficiency of kidney and hyperactivity of liver | 30 min/day, 5 days/week for 4 weeks | BL17, BL18, BL23, EX, EX-HN1, GV20, KI3, LR3 | Estazolam 1–2 mg/day, 7 days/week for 4 weeks | PSQI, HAMA MSMSMS (REM%) | (i) Lower PSQI in MA group (ii) Higher REM% in MA group |

No follow-up | - MA/n=3 (hematoma) - Estazolam/n=7 [dizziness (2); daytime sleepiness (2); fatigue (3)] |

| Yang et al 201766 | - MA/n=81 - Estazolam/n=81 |

PMI (CCMD-2) | Liver and kidney Yin deficiency | 30 min/day, 15 days/month (one treatment every other day) for 3 months | CV12, HT7, KI3, PC6, ST36, ST40, four scalp acupoints (middle 1/3 of frontal apical band, posterior 1/3 of frontal apical band, anterior 1/3 of skull base band, middle 1/3 of skull base band) | Estazolam 1 mg/day, 10 days/month for 3 months | PSQI, FSH, E2, LH | (i) Lower PSQI in MA group (ii) Higher FSH levels, and lower E2 and LH levels in MA group |

No follow-up | NR |

| Zhang et al 201767 | - MA/n=31 - Estazolam/n=30 |

PMI (DTICA, CDTE-TCM) | Six syndrome patterns with liver as the core | 30 min/day, 5 days/week for 4 weeks | BL17, BL18, EX, EX-HN1, GV20, LR3 | Estazolam 1 mg/day, 7 days/week for 4 weeks | PSQI, KI, HAMA, HAMD | Lower PSQI, KI, HAMA and HAMD in MA group | No follow-up | - MA/n=1 (hematoma) - Estazolam/n=4 [dizziness (2); fatigue and daytime sleepiness (2); memory loss (2)] |

| Yan et al 202168 | - MA/n=42 - Estazolam/n=43 |

PMI (CCMD-3) | NR | 30 min/day, 7 days/week for 12 weeks | CV4, CV6, GV20, GV24, HT7, SP6 | Estazolam 1 mg/day, 7 days/week for 12 weeks | PSQI, Men-QoL | Lower PSQI and Men-QoL in MA group | No follow-up | - MA/n=4 [dizziness (3); hematoma (1)] - Estazolam/n=3 [dizziness (1); fatigue and daytime sleepiness (2)] |

| Li et al 2018b69 | - EA/n=116 - Escitalopram/n=105 |

PMD (DSM-V, ICD-10) | NR | − 30 min/day, 3 days/week for 12 weeks - dilatational wave, 50 Hz, 0.5–1 mA |

CV4, EX-CA1, EX-HN3, GV20, LI4, LR3, SP6, ST25 | Escitalopram 10mg/day for 12 weeks | HAMD, Men-QoL, FSH, E2, LH | (i) No differences in HAMD and Men-QoL between two groups (ii) No differences in FSH, E2 and LH levels between two groups |

(i) Lower HAMD in EA group at 4-and 12-week follow-ups (ii) Lower Men-QoL in EA group in 4-, 8-and 12-week follow-ups |

- EA/n=14 (hematoma) - Escitalopram/n=18 (dizziness, palpitation, stomachache) |

| Chi et al 201170 | - MA/n=30 - Fluoxetine/n=30 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | NR | 30 min/day for 4 weeks | EX-HN1, EX-HN3, GV20, KI3, LR3, LR14, SP6, ST36 | Fluoxetine 20 mg/day for 4 weeks | HAMD | Lower HAMD in MA group | No follow-up | - MA/n=0 - Fluoxetine/n=3 [dizziness (1); nausea (2)] |

| Deng 200871 | - MA/n=29 - Deanxit/n=29 |

PMD (ICD-10) | NR | 20–30 min/day, after 3 consecutive days of treatment, once treatment every 3 days for total 4 weeks | CV3, CV4, CV6, CV10, CV12, KI17, Qipang (0.5 Cun beside CV6), Xiafengshidian (1 Cun below and beside ST26) | Deanxit 20mg/day for 4 weeks | HAMD, KI, 5-HT | (i) No differences in HAMD and KI between two groups (ii) No differences in 5-HT levels between two groups |

(i) Lower HAMD in MA at 2-week follow-up (ii) No difference in HAMD between two groups at 4-week follow-up (iii) No difference in KI between two groups at 2-and 4-week follow-ups |

- MA/n=3 [changes of character of stool (2); palpitation (1)] - Deanxit/n=32 [changes of character of stool (6); dry mouth and halitosis (9); dysphoria (6); dreaminess (6); breast distending pain (5)] |

| Dong 201585 | - MA/n=30 - Nilestriol + Fluoxetine/n=30 |

PMD (CCMD-3, CDTE-TCM) | NR | 30 min/day for 30 days | BL13, BL15, BL17, BL18, BL20, BL21, BL23 | Nilestriol 2mg/15days for 30 days + Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 30 days | HAMD | Lower HAMD in MA group | No follow-up | NR |

| Li 2015b72 | - MA/n=32 - Fluoxetine/n=32 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | Liver stagnation and kidney deficiency | 30 min/day, 6 days/week for 12 weeks | BL15, BL18, BL23, EX-HN1, EX-HN3, GV20, GV24, PC6 | Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 12 weeks | HAMD, KI | Lower HAMD and KI in MA group | Follow-up for 12 weeks; no data of HAMD and KI global scores for follow-up | - MA/n=0 - Fluoxetine/n=8 [nausea and vomiting (2); dry mouth (1); indigestion (1); diarrhea (1); dizziness (1); headache (1)] |

| Ma et al 200973 | - MA/n=30 - Fluoxetine/n=30 |

PMD (CCMD-3, CDTE-TCM) | NR | 30 min/day, 5 days/week for 8 weeks | EX-HN1, EX-HN3, GV20, HT7, PC6, PC7, SP6, ST36 | Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 8 weeks | HAMD | No differences in HAMD between two groups | No follow-up | - MA/n=0 - Fluoxetine/n=6 [nausea (2); dizziness (2)] |

| Niu et al 201774 | - MA/n=41 - Fluoxetine/n=41 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | Stagnation of liver Qi | 30 min/day, 5 days/week for 6 weeks | BL13, BL15, BL17, BL18, BL20, BL23 | Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 6 weeks | HAMD | Lower PSQI in MA | No follow-up | - MA/n=7 [dizziness (2); palpitation (1); dry mouth (1); nausea (3)] - Fluoxetine/n=6 [dizziness (1); palpitation (2); dry mouth (2); nausea (1)] |

| Qian et al 200775 | - MA/n=33 - Fluoxetine/n=30 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | NR | 25 min/day, 5 days/week for 6 weeks | BL13, BL15, BL17, BL18, BL20, BL23 | Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 6 weeks | HAMD | No differences in HAMD between two groups | No follow-up | - MA/n=2 [dizziness (1); palpitation (1)] - Fluoxetine/n=9 [insomnia (1); akathisia (1); dry mouth (1); nausea (1); palpitation (1); skin symptom (1); excitation and agitation (2)] |

| Qiang 200876 | - MA/n=30 - Fluoxetine/n=30 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | NR | 25 min/day, 5 days/week for 6 weeks | BL15, BL18, BL23, EX-HN1, GB20 | Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 6 weeks | HAMD | No differences in HAMD between two groups | No follow-up | NR |

| Shi et al 201877 | - EA/n=30 - Escitalopram/n=30 |

PMD (DSM-V) | NR | − 30 min/day, 3 days/week for 12 weeks - dense-sparse wave, 10/50Hz, 0.5–1.0mA |

CV4, EX-CA1, EX-HN3, GV20, LI4, LR3, SP6, ST25 | Escitalopram 10mg/day for 12 weeks | HAMD | Lower HAMD in EA group | Lower HAMD in EA at 4- and 12- week follow-ups | NR |

| Sun et al 201578 | - EA/n=21 - Escitalopram/n=21 |

PMD (DSM-V) | NR | − 30 min/day, 3 days/week for 12 weeks - dense-sparse wave, 10/50Hz, 0.5–1.0mA |

CV4, EX-CA1, EX-HN3, GV20, LI4, LR3, SP6, ST25 | Escitalopram 10mg/day for 12 weeks | HAMD | Lower HAMD in EA group | No follow-up | NR |

| Wang et al 201079 | - MA/n=21 - Deanxit/n=21 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | NR | 30 min/day, after 3 consecutive days of treatment, once treatment every 3 days for total 4 weeks | CV3, CV4, CV6, CV10, CV12, KI17 | Deanxit 10 mg/day for 4 weeks | HAMD | No differences in HAMD between two groups | Lower HAMD in MA at 2- and 4- week follow-ups | - MA/n=3 [changes of character of stool (2); palpitation (1)] - Deanxit/n=15 [dry mouth and halitosis (9); dysphoria, dreaminess, or breast distending pain (6)] |

| Zhang 201086 | - EA/n=44 - Nilestriol+ Fluoxetine/n=46 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | NR | − 30 min/day, 5 days/week for 12 weeks - dilatational wave, 8–9 mA, 6V |

BL13, BL15, BL17, BL20, BL23, GV20, KI3, LR3, PC6, SP6 | Nilestriol 2mg/14 days for 30 days + Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 12 weeks | HAMD, KI, FSH, E2, LH | (i) No differences in HAMD and KI between two groups (ii) No differences in FSH, LH and E2 levels between two groups |

No follow-up | - EA/n=5 (sweating, dizziness, vomiting) - Nilestriol+ Fluoxetine/n=23 [dry mouth and halitosis (5); nausea (6); dysphoria (2); constipation (6); dreaminess (2); breast distending pain (2)] |

| Zhang 201387 | - MA/n=94 - Premarin + Provera + Fluoxetine/n=94 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | NR | 30 min/day, 7 days/week for 12 weeks | EX-HN1, GB13, GV20, GV24, HT7 | Premarin 0.625mg/day and Provera 6mg/day + Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 12 weeks | HAMD, FSH, E2, LH | (i) Lower HAMD in MA group (ii) No differences in FSH, LH and E2 levels between two groups |

No follow-up | - MA/n=2 (feeling pain when inserting needle) - Premarin + Provera + Fluoxetine/n=12 [dizziness (5); nausea and vomiting (4); hypersomnia (3)] |

| Zheng et al 201088 | - MA/n=60 - Premarin + Provera + Fluoxetine/n=60 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | NR | 30 min/day, 7 days/week for 12 weeks [needle retaining time for 8 hour in three acupoints (BL8, GV19, GV21) per session] |

BL8, BL18, BL23, GV19, GV21, KI3, LR3, SP6 | Premarin 0.625mg/day for 20 days + and Provera 6mg/day + Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 12 weeks | HAMD, KI, FSH, E2, LH | (i) No differences in HAMD and KI between two groups (ii) No differences in FSH and LH levels between two groups; Lower E2 level in MA group |

Lower HAMD and KI in MA at 24-week follow-up | - MA/n=2 (feeling pain when inserting needle) - Premarin + Provera + Fluoxetine/n=18 [loss of appetite (5); dizziness (4); diarrhea (3); breast distending pain (3); leukorrhagia (2); spasmus (1)] |

| Ding et al 200780 | - MA/n=39 - Fluoxetine/n=39 |

PMD (CCMD-2-R) | NR | 30 min/day, 6 days/week for 4 weeks | BL15, BL18, BL20, BL23, GV20, HT7, LR3, SP6 | Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 4 weeks | HAMD, KI | No differences in HAMD between two groups; Lower KI in MA group | No follow-up | NR |

| Li et al 2020b81 | - EA/n=30 - Fluoxetine/n=30 |

PMD (CDTE-TCM) | NR | − 25 min/day, 3 days/week for 6 weeks - dilatational wave, 15 Hz, 1 mA |

EX-HN1, EX-HN3, GV20, HT7, LI4, PC6, SP6, ST36 | Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 6 weeks | HAMD, HAMA | No differences in HAMD between two groups; Lower HAMA in EA group | No follow-up | NR |

| Zhang 201582 | - MA/n=29 - Deanxit/n=29 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | NR | 30 min/day, after 3 consecutive days of treatment, once treatment every 3 days for total 4 weeks | CV3, CV4, CV6, CV10, CV12, KI17 | Deanxit 20 mg/day for 4 weeks | HAMD | No differences in HAMD between two groups | Lower HAMD in MA at 2- and 4- week follow-ups | NR |

| Xing 201183 | - MA/n=120 - Fluoxetine/n=120 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | Stagnation of liver Qi, heart and spleen deficiency; liver depression and phlegm-heat | 20 min/day, 7 days/week for 6 weeks | GV26, PC5 | Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 6 weeks | HAMD | No differences in HAMD between two groups | No follow-up | NR |

| Zhou et al 200784 | - MA/n=30 - Fluoxetine/n=28 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | Liver and kidney Yin deficiency, spleen and kidney Yang deficiency, stagnated Qi transforming into fire, stagnation of phlegm and Qi | 30 min/day, 6 days/week for 6 weeks | BL15, BL18, BL23, EX-HN1, GB13, GV24, SP6, ST36 | Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 6 weeks | HAMD, 5-HIAA, NE, DA | (i) Lower HAMD in MA group (ii) No differences in 5-HIAA and NE levels between two groups; Lower DA level in MA group |

No follow-up | NR |

| Gao et al 201489 | - MA + Estazolam/n=32 - Estazolam/n=32 |

PMI (CCMD-3) | NR | 20 min/day, 6 days/week for 4 weeks | EX-B2 | Estazolam 2 mg/day for 4 weeks | PSQI | Lower PSQI in MA + Estazolam group | No follow-up | NR |

| Xu 202090 | - MA + Alprazolam/n=50 - Alprazolam/n=50 |

PMI (CDTE-TCM) | NR | 30 min/day, 7 days/week for 9 weeks | EX-HN1, GV24, HT7, KI3, LR3, PC6, SP6, ST36 | Alprazolam 0.4–0.8 mg/day, 7 days/week for 9 weeks | PSQI | Lower PSQI in MA + Alprazolam group | No follow-up | NR |

| Ma 201691 | - MA + Estazolam/n=35 - Estazolam/n=35 |

PMI (CCMD-3) | NR | 7 days/week for 4 weeks | EX, HT7, KI3, KI7, KI10, LR3, SP6, SP10, ST36 | Estazolam 2 mg/day, 7 days/week for 4 weeks | PSQI, FSH, E2 | (i) Lower PSQI in MA + Estazolam group (ii) Higher E2 levels, and lower FSH levels in MA + Estazolam group |

No follow-up | NR |

| Zhu et al 201692 | - MA + Estazolam/n=37 - Estazolam/n=37 |

PMI (CCMD-3) | Heart and Spleen deficiency | 20 min/day, 5 days/week for 4 weeks | CV12, EX, EX-HN1, GV20, GV24, HT7, KI3, LR3, SP9, ST25 | Estazolam 1 mg/day, 5 days/week for 4 weeks | PSQI | No differences in PSQI between two groups | No follow-up | NR |

| Ma et al 201195 | - EA + Paroxetine/n=55 - Paroxetine/n=50 |

PMD (CCMD-3) | NR | − 45 min/day, 7 days/week for 6 weeks - dilatational wave, 8–9 mA |

EX-HN3, GV20, LI4, PC6, ST36 | Paroxetine 10mg/day for 6 weeks | HAMD | No differences in HAMD between two groups | No follow-up | - EA + Paroxetine/n=2 [dizziness (1); nausea (1)] - Paroxetine/n=3 [dizziness (1); elevated blood pressure (2)] |

| Liu et al 201993 | - MA + Sertraline/n=40 - Sertraline/n=40 |

PMD (CCMD-3, ICD-10) | NR | 30 min/day, 3 days/week for 12 weeks | BL23, CV4, HT7, KI3, LI4, LR3, SP6 | Sertraline 50mg/day for 6 weeks | HAMD, FSH, E2, 5-HT, GABA | (i) Lower HAMD in MA + Sertraline group (ii) Lower FSH level in MA + Sertraline group; higher E2, 5-HT and GABA levels in MA + Sertraline group |

No follow-up | NR |

| Ning 201594 | - MA + Nilestriol + Fluoxetine/n=45 - Nilestriol + Fluoxetine/n=45 |

PMD (Psychiatry textbook) | NR | 30 min/day, 7 days/week for 12 weeks | BL13, BL15, BL18, BL20, BL23, GV20, HT7, KI3, LI4, LR3 | Nilestriol 2mg/15days + Fluoxetine 20mg/day for 12 weeks | HAMD, TESS | Lower HAMD and TESS in MA + Nilestriol + Fluoxetine group | No follow-up | NR |

Abbreviations: NR, no report; MA, manual acupuncture; EA, electroacupuncture; PMI, perimenopausal insomnia; PMD, perimenopausal depression; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition); ICSD-3, International classification of sleep disorders (Third Edition); CCMD-2-R, revised Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (Second Edition); CCMD-3, Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (Third Edition); ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases (10th edition); DTICA, Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Insomnia in Chinese Adults (2012 Edition); CDTE-TCM, Criteria of Diagnosis and Therapeutic Effect of Diseases and Syndromes in TCM; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; AIS, Athens Insomnia Scale; KI, Kupperman Index; MRS, Menopause Rating Scale; Men-QoL, Menopause-Specific Quality of Life; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Scale; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Scale; SAS, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; SDS, Self-Rating Depression Scale; WHOQOL-BREF, World Health Organization’s quality of life scale-brief form questionnaire; TESS, Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale; PSG, polysomnography; MSMSMS, micromovement sensitive mattress sleep monitoring system; SOL, sleep onset latency; WASO, wake after sleep onset; TST, total sleep time; SE, sleep efficiency; ATs, awakening times; AA, average awakening; ArI, arousal index; REM, rapid eye movement; N1(2, 3, 4), 1st(2nd, 3rd, 4th) period of non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM); FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; E2, estradiol; 5-HT, 5-hydroxy tryptamine; NE, norepinephrine; DA, dopamine; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; six syndrome patterns with liver as the core [liver stagnation (stasis); excessive liver fire due to emotional suppression; Disturbance of liver Yang; deficiency of kidney and hyperactivity of liver; liver depression invading the stomach; liver depression invading the heart]; five TCM syndrome patterns according to CDTE-TCM [excessive liver fire due to emotional suppression; disturbance of Heart due to phlegm heat; Yin deficiency leading to excessive fire; Heart and Spleen deficiency; Heart and Gallbladder Qi deficiency]; BL8, Luoque; BL13, Feishu; BL15, Xinshu; BL17, Geshu; BL18, Ganshu; BL20, Pishu; BL21, Weishu; BL23, Shenshu; BL62, Shenmai; CV3, Zhongji; CV3, Zhongji; CV4, Guanyuan; CV6, Qihai; CV10, Xiawan; CV12, Zhongwan; EX, Anmian; EX-B2, Jiaji; EX-CA1, Zigong; EX-HN1, Sishencong; EX-HN3, Yintang; GB13, Benshen; GB14, Yangbai; GB15, Toulinqi; GB20, Fengchi; GB25, Jingmen; GV3, Yaoyangguan; GV4, Mingmen; GV14, Dazhui; GV16, Fengfu; GV19, Houding; GV20, Baihui; GV21, Qianding; GV24, Shenting; GV26, Shuigou; HT7, Shenmen; KI3, Taixi; KI6, Zhaohai; KI7, Fuliu; KI10, Yingu; KI13, Qixue; KI17, Shangqu; LI4, Hegu; LR3, Taichong; LR14, Qimen; LU7, Lieque; PC5, Jianshi; PC6, Neiguan; PC7, Daling; SI3, Houxi; SP4, Gongsun; SP6, Sanyinjiao; SP8, Diji; SP9, Yinlingquan; SP10, Xuehai; SP15, Daheng; ST25, Tianshu; ST26, Wailing; ST36, Zusanli; ST40, Fenglong.

Table 3.

Results of Meta-Analyses for Existing RCTs

| Comparison | Study (n); Participants (n) | Outcomes | Mean/Std. Mean Difference IV, Random, 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acupuncture vs waitlist-control or placebo-/sham- acupuncture | RCTs (n = 4); PMI women (n = 283) | PSQI | MD = −4.03, 95% CI (−6.85, −1.21) | <0.01 |

| RCTs (n < 3, no meta-analysis); PMD women (n = 126) | - | - | - | |

| Acupuncture vs hypnotic | RCTs (n = 12); PMI women (n = 1204) | PSQI | MD = −2.24, 95% CI (−3.13, −1.36) | <0.01 |

| RCTs (n = 4); PMI women (n = 274) | KI | MD = −5.95, 95% CI (−10.68, −1.21) | 0.01 | |

| Acupuncture vs antidepressant/antidepressant + HRT | RCTs (n = 21); PMD women (n = 1842) | HAMD at post-treatment | SMD = −0.54, 95% CI (−0.91, −0.16) | <0.01 |

| RCTs (n = 3); PMD women (n = 169) | HAMD at 2-week follow-up | SMD= −0.64, 95% CI (−0.95, −0.33) | 0.01 | |

| RCTs (n = 6); PMD women (n = 504) | HAMD at 4-week follow-up | SMD = −1.36, 95% CI (−2.72, 0.00) | 0.05 | |

| RCTs (n = 3); PMD women (n = 341) | HAMD at 12-week follow-up | SMD = −2.73, 95% CI (−6.14, 0.67) | 0.12 | |

| RCTs (n = 5); PMD women (n = 410) | KI | MD= −2.80, 95% CI (−5.60, −0.01) | 0.05 | |

| Acupuncture + hypnotics vs hypnotics | RCTs (n = 4); PMI women (n = 308) | PSQI | MD = −2.80, 95% CI (−4.23, −1.37) | <0.01 |

| Acupuncture + antidepressant/antidepressant + HRT vs antidepressant or antidepressant + HRT | RCTs (n = 3); PMD women (n = 275) | HAMD at post-treatment | SMD = −0.82, 95% CI (−1.07, −0.58) | <0.01 |

Note: Data from references 19 and 50.

Abbreviations: PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; KI, Kupperman Index; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Scale; HRT, hormone replacement therapy.

Effectiveness and Efficacy of Acupuncture for PMI and PMD

We classified the retrieved RCTs into two categories: acupuncture as an independent or as an adjuvant to standard care in the management of PMI/PMD.

In the first category, six RCTs confirmed significant improvements acupuncture produced on sleep duration and quality51–54 as well as depressed mood,55,56 when compared with waitlist or placebo controls. Thirteen RCTs compared the effects between acupuncture and various hypnotics including Estazolam, Alprazolam, and Eszopiclone.49,57–68 All these studies reported that acupuncture reduced global scores of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)/Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) more effectively than hypnotics, except for two trials58,61 that reported the sleep-promoting effects between the two therapies were equivalent. Twelve out of these 13 trials employed the PSQI as an outcome measure, and the results of meta-analysis favored acupuncture [MD = −2.24, 95% CI (−3.13, −1.36), p< 0.01]. Twenty-one RCTs compared the effects between acupuncture and antidepressants including escitalopram, fluoxetine, and deanxit,56,69–84 or the effects between acupuncture and antidepressants combined with HRT.85–88 All trials adopted the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) as an outcome measure. The results of meta-analysis favored acupuncture in reducing the HAMD global scores [SMD= −0.54, 95% CI (−0.91, −0.16), p< 0.01]. Some of these RCTs also reported that the effects of acupuncture remained no weaker than those of Western medications at 2-, 4-, and 12-week follow-ups, suggesting an intermediate- to long-term antidepressive efficacy of acupuncture (Table 3).

In the second category, the meta-analysis pooled the effects of four RCTs89–92 and supported a better effect of acupuncture combined with hypnotics in reducing PSQI global score, in comparison with hypnotics alone [MD = −2.80, 95% CI (−4.23, −1.37), p < 0.01]. Two RCTs93,94 indicated that acupuncture combined with antidepressants produced lower HAMD scores than antidepressants alone. Although another RCT95 found no statistically significant differences in HAMD scores between the two therapies at post-treatment, the clinical effectiveness rate (calculated based on the HAMD reduction rate) favored the combination therapy (acupuncture + Paroxetine 90.91% vs Paroxetine alone 78.00%). The meta-analysis based on these three RCTs favored the combination therapy in reducing HAMD global scores as well [SMD = −0.82, 95% CI (−1.07, −0.58), p < 0.01] (Table 3).

Safety of Acupuncture for PMI and PMD

The incidence of AEs associated with each intervention in the included RCTs is summarized in Appendix 1 (in order of highest % for acupuncture). Consistent with the previous studies that acupuncture is safe to manipulate,36,37 there appears to be few risks associated with utilizing acupuncture in the management of PMI/PMD as the AEs caused by acupuncture were minimal and very mild. Hematoma (7.72%), the most frequent complaint, usually faded within a few days.19,50 The incidence of other acupuncture-related AEs was less than 4%, with the exception of sweating (6.76%). The latter however is likely to be related to menopause rather than acupuncture as this is a common symptom for perimenopausal women.13,96 The incidence and severity of AEs associated with psychotropic agents (hypnotics or antidepressants) far exceeded those of acupuncture. The most common of these were daytime sleepiness and/or fatigue (29.38%), breast tenderness (22%) and night-time sleep disturbance (18.18%). These findings are noteworthy given the problem of PMI/PMD and suggest that some of these treatments may exacerbate rather than alleviate the symptoms. Only one RCT97 used HRT alone as a control but still identified at least three types of AEs.

These findings are highly supportive of the use of acupuncture as a therapeutic strategy in PMI and/or PMD. The data suggest that it does not matter whether the therapeutic effect of acupuncture is better or only equivalent to that of HRT and/or hypnotics/antidepressants, acupuncture can be supported as a front-line, first-choice therapeutic because of its exemplary safety profile.

Implications for Clinical Practice

This section discusses the meaningfulness and feasibility of acupuncture for PMI and PMD. In addition to improving sleep or depression outcomes, acupuncture also showed positive effects on indices of climacteric symptoms (ie, Kupperman Index, Menopause Rating Scale, etc), quality of life in menopause (ie, Menopause-Specific Quality of Life, World Health Organization’s quality of life scale-brief form questionnaire, etc), and/or anxiety symptoms (ie, Hamilton Anxiety Scale, etc). (Tables 2 and 3) These findings suggest that women with PMI/PMD as their chief complaint benefited from acupuncture in a broad range of signs and symptoms associated with life change. This finding is consistent with the “holistic medicine” concept highlighted in the TCM, which views the body as a complete entirety.43,44,98 “Healthy” in TCM does not simply mean “disease free”; it means that all Zang and Fu (organs), meridians and collaterals are working in harmony, and the flow of Qi, blood and body fluids is at ease, and emotions and spiritual state are in balance.26,28,43 In terms of TCM theory, a diseased condition is not only a problem in a local part of the body but a local reflection of disharmony of the entire body.43,44 Hence, TCM therapies generally address a diseased condition (condition with an imbalance between Yin and Yang) by regulating and mobilizing the entire body rather than just regulating a single factor (one symptom or one part/organ of the body).43,44,98 As suggested, any potential climacteric condition (eg, nocturnal hot flushes, chronic pain, neuropsychiatric problems, etc) that may adversely affect sleep and/or mood should be considered when menopausal women seek medical advice.23 This circumstance is in line with the “holistic medicine” theory of TCM, which makes acupuncture more worthy of being recommended.

Limited evidence suggests acupuncture is likely to have an add-on effect to hypnotic and/or antidepressive drugs. However, in seven trials focusing on acupuncture combined with standard care, only one study95 reported the AEs; no trials included follow-up (Tables 2 and 3). Consequently, the safety and long-term effects of this integrative remedy is still less well understood. Consumers who are not familiar with acupuncture may not be willing to give up drug-based medicines immediately.19 Whether reduced use of conventional drugs can be made up by the addition of acupuncture is a topic with important clinical significance because reduction of dosage in conventional drugs means fewer risks of side effects. Likewise, this add-on effect of acupuncture is also of importance in personalized medicine. Given the efficacy for all therapies may be hampered by the fact that women respond differently to each, acupuncture is ideal to be recommended as the first therapy in a layered approach, so that if acupuncture is ineffective then lower dose Western medication (eg, HRT, psychotropic agents, etc) could be tried in combination with the acupuncture prior to direct usage of pharmacotherapy or higher dose of pharmacotherapy. This treatment strategy may be particularly suitable for those women with PMI/PMD who are intolerant of drugs.

Acupoint selection is one of the decisive factors affecting the clinical effectiveness of acupuncture.99 As illustrated in Table 2, the three most commonly used acupoints for PMI were Sanyinjiao (SP6), Baihui (GV20), and Shenmen (HT7), while the three most commonly used acupoints for PMD were GV20, SP6, and Yintang (EX-HN3). According to “Indications of Acupuncture Points [GB/T 30233–2013]” (National Standard of People’s Republic of China, 2013 Version),100 GV20, HT7, and EX-HN3 are classic acupoints for the treatment of psychiatric and psychological disorders. SP6 is the preferred acupoint for gynaecological disorders, and together with HT7, it promotes sleep. Based on TCM syndrome patterns, for any deficient patterns, the Back-shu are used as these acupoints where the Qi of the internal organs is accumulated, and are used to strengthen the corresponding organs.100 Ganshu (BL18), the Back-shu of liver, as well as Shenshu (BL23), the Back-shu of kidney, were selected in many trials (Table 2), which is consistent with the aforementioned findings that smoothing liver and nourishing kidney is the general principle for all perimenopausal disorders. In treating comorbid PMI and PMD, practitioners are hence recommended to select Back-shu of liver and kidney, and/or acupoints of Liver Meridian of Foot-Jueyin and Kidney Meridian of Foot-Shaoyin, in addition to the classical acupoints utilized for mental disease/disorders. Both MA and EA showed significant clinical benefits for PMI/PMD (Table 2). However, no study has compared MA with EA. The differences in clinical effects and underlying mechanisms of MA and EA should be explored in future clinical trials and animal studies.

Our comprehensive retrieval of literature failed to identify any RCT carried outside of China, reflecting the extremely inadequate awareness and attention paid to acupuncture in PMI/PMD management among Western researchers, despite well-documented evidence supporting the growing widespread use of CAM therapy for psychiatric complaints among Western populations.23,101 Meanwhile, some surveys alluded that most Western women may also underestimate the value and role of acupuncture as a management strategy for PMI and/or PMD. As reported, only 4.8% women in Australia have visited an acupuncturist due to menopausal symptoms;102 In the UK, 6.4% climacteric women utilize aromatherapy, reflexology, or acupuncture to reduce symptoms.103 This review thereby is expected to evoke awareness of the potential of acupuncture among both perimenopausal women and clinicians working in this field (ie, gynaecologists, psychiatrists, and naturopaths) in Western countries. Given all the participants in the included RCTs were Chinese women, generalizing the currently optimistic results to women of other races requires some further evidence.104 According to the differences in awareness, perception, and tolerance of acupuncture between Westerners and Chinese, limited modification to the nature acupuncture prescription/protocol summarized in published Chinese studies may also enhance the acceptance and applicability of acupuncture among Western perimenopausal women.

Another issue that has not yet been addressed is whether interventions can be provided during pre-menopause to prevent or reduce the occurrence of PMI and/or PMD. Women with a history of depression105 or experiencing stressful events6 at pre-menopause are at high risk for PMD. Women with a history of severe premenstrual syndrome and/or psychological disturbances may benefit from preventive treatments for reducing the likelihood of PMI or ameliorating the symptoms.10 These women may be a target group for preventive acupuncture (also called “acupuncture pre-treatment”), which is in line with the idea of “preventive treatment of disease” (治未病, prevent individuals from being trapped by diseases) in TCM theory.44 Despite the lack of direct evidence, acupuncture pre-treatment may have positive preventive effects for perimenopausal symptoms. Most research in this area has been based on animal models. Acupuncture pre-treatment was observed to reduce oxidative stress levels,106,107 inhibit the hyperactivity of hypothalamic-pituitary-ovary (HPO) axis,106 as well as regulate the inflammatory response and disorders of the immune system108 in either ageing female rats or rats that were ovariectomized to mimic menopause. Li et al reported that EA pre-treatment (EA was provided 10 days before chronic stress) effectively prevented the depression-like behavior of rats after undergoing chronic unpredicted mild stress (CUMS).109

Implications for Research

The data from the few clinical trials discussed here appears to be promising, it is however too early to draw any definitive conclusions. Many RCTs have missing components in their methodology, which dilutes and weakens the quality of evidence, and may hinder the development of acupuncture as a form of evidence-based healthcare for comorbid depression and insomnia during perimenopause.

We have summarized the common deficiencies among these RCTs and listed the potential negative consequences in Table 4. Detailed assessment and analysis on quality of evidence is described in our published SRs/MAs.19,50 As reported, poor-quality acupuncture studies usually show a higher proportion of positive results than high-quality studies.104 Well-designed trials with robust methodology and high-quality reporting quality are warranted in future research.

Table 4.

Common Defects of Study Design and Reporting Quality Among Current RCTs

| Items | Limitations | Potential Negative Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | Lack of appropriate sample size estimation | Diminishment of credibility of the results; reduction in likelihood of finding an effect of the treatment |

| Lack of sham-/placebo- acupuncture as parallel control in trials comparing acupuncture with Western medications | Potential bias and uncertainty on the placebo effects of acupuncture | |

| Without appropriate statistics (ie intention-to-treat analysis, etc) for data of those withdrawal/dropout patients | Increased risk of an overestimation/underestimation of the efficacy of acupuncture or Western medications | |

| Lack of follow-ups | Unable to evaluate medium- and long- term effects/safety of acupuncture | |

| Objective indices (ie, polysomnography, actigraphy, etc) is seldom used in PMI studies | (i) Unable to understand the effects of acupuncture on sleep architecture (ii) A biased judgement or even a question on acupuncture’s real efficacy due to a mismatch between the subjective and objective sleep-wake duration |

|

| No discussion of the effects of acupuncture responding to specific/each TCM syndrome pattern (all TCM syndrome patterns are mixed for efficacy assessment) | Difficult to judge the real therapeutic effect of acupuncture | |

| Reporting quality | Lack of reports on if or how allocation concealment and blinding of patients/outcome assessments are performed | Inadequate blinding is associated with an exaggeration of the estimated efficacy |

| Lack of description and in-depth analysis of the specific causes of withdrawal/dropout | Unable to understand patient’s compliance and acceptance of acupuncture, placebo or Western medications | |

| Protocols and/or registration Information are not always available | Greatly weakens the reliability of the evidence | |

| Incomplete descriptions of needling details and/or treatment regimen, as well as acupuncturists’ background | (i) Poor reproducibility of the trial results (ii) Hinder the clinical promotion of effective acupuncture prescription |

Underlying Mechanisms of Acupuncture’s Effects Against Depression and Insomnia During Perimenopause

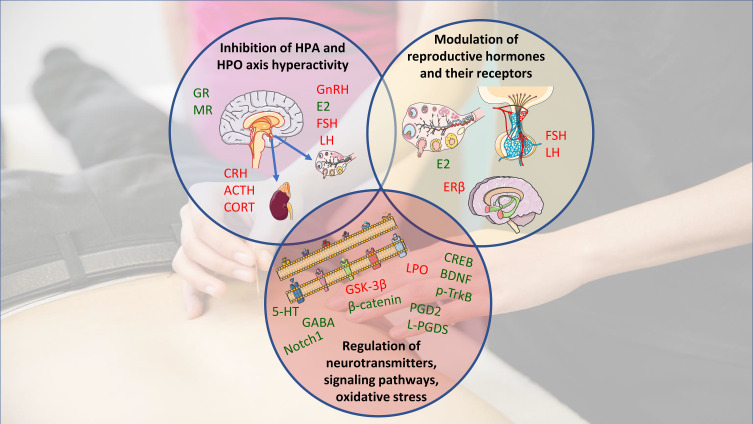

It is challenging to explore the mechanisms underlying the effects of acupuncture on depression and insomnia during the transition to menopause in only RCTs. To enhance our understanding, investigation via animal studies is a valuable option. Together with clinical findings, animal studies can shed light on the mechanisms of action of acupuncture (Figure 1) as well as give an insight into the direction of further research. Findings of animal studies are summarized in Table 5.

Figure 1.

Potential mechanisms by which acupuncture may improve perimenopausal depression and insomnia. Manual- and/or electro-acupuncture may alter hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and -ovarian hyperactivity; modulate reproductive hormones and their receptors, or regulate neurotransmitters, signaling pathways, and oxidative stress. Green indicates an upregulation/increase by acupuncture (↑); red indicates a downregulation/decrease (↓). Acupuncture may also improve perimenopausal depression and insomnia by improving vasomotor symptoms, while this indirect effect is not shown. Images are adapted from Servier Medical Art under Creative Commons CC-BY license.

Abbreviations: HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; HPO, hypothalamic-pituitary-ovary; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; E2, estradiol; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; CORT, cortisol; ERβ, estrogen receptor beta; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; GABA, gamma-amino butyric acid; CREB, cAMP-response element-binding protein; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; p-TrkB, phosphorylated-TrkB; PGD-2, prostaglandin D2; L-PGDS, lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase; LPO, lipid peroxidation; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta.

Table 5.

Summary of Animal Studies Determining the Mechanisms Underlying Acupuncture on PMI and PMD

| Author/Year | Animals | Disease Models | Methods of Modeling | Study Groups/No. of Participants | Interventions | Acupuncture Protocol | Acupoints | Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cao et al 2019152 | SD rats, 280–320g, 12 months | PMI | (i) OVX (ii) Electrical stimulation |

- EA/n= 12 - Model/n= 12 - Sham-surgery/n= 12 |

- EA/OVX + electrical stimulation + EA - Model/OVX + electrical stimulation - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX + electrical stimulation |

− 20 min/day for 14 days - Dense wave, 50Hz |

SP6 | (i) MER (REM, SWS) (ii) 5-HT, 5-HIAA, 5-HT1A in hippocampus |

(i) EA increased REM and SWS (ii) EA increased 5-HT and 5-HT1A levels; no significant change in 5-HIAA level |

| Cao et al 2020136 | Wistar rats, 230–270g, 5–7 months | PMI | (i) OVX (ii) Electrical stimulation |

- EA/n= 10 - Model/n= 10 - Sham-surgery/n= 10 |

- EA/OVX + electrical stimulation + EA - Model/OVX + electrical stimulation - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX + electrical stimulation |

− 15 min/day for 21 days - Dense wave, 50Hz |

EX-HN1, HT7 | (i) MER (TST, REM, SWS, LS) (ii) L-PGDS, PGD2, PGE2 in CSF (iii) GABA in VLPO |

(i) EA increased REM, SWS; no significant change in TST and LS (ii) EA increased L-PGDS and PGD2 levels; no significant change in PGE2 level (iii) EA increased GABA level |

| Jin et al 2010189 | SD rats, 230–270g, 3 months | PMI | (i) OVX (ii) Electrical stimulation |

- EA/n= 30 - Model/n= 30 - Sham-surgery/n= 30 |

- EA/OVX + electrical stimulation + EA - Model/OVX + electrical stimulation - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX + electrical stimulation |

− 30 min/day for 7 days - Continuous wave, 15Hz, 2mA |

BL23, SP6 | (i) SOL and TST (ii) Heat-resistant time (iii) Energy (iv) Times of locomotor activity |

(i) EA increased TST and reduced SOL (ii) EA increased heat-resistant time (iii) EA increased energy (iv) No significant change in times of locomotor activity (v) The earlier the intervention of EA in the perimenopausal period, the better the effect |

| Jin et al 2011190 | SD rats, 150–180g | PMI | (i) OVX (ii) Electrical stimulation |

- EA/n= 30 - Model/n= 30 - Sham-surgery/n= 30 |

- EA/OVX + electrical stimulation + EA - Model/OVX + electrical stimulation - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX + electrical stimulation |

− 30 min/day for 7 days - Continuous wave, 15Hz, 2mA |

BL23, SP6 | (i) SOL and TST (ii) Heat-resistant time (iii) Energy |

(i) EA increased TST and reduced SOL (ii) EA increased heat-resistant time (iii) EA increased energy (iv) The earlier the intervention of EA in the perimenopausal period, the better the effect |

| Xie 2013116 | SD rats, 216–245.8g, 6–8 weeks | PMI | OVX | - EA/n= 25 - Model/n= 25 - Sham-surgery/n= 25 - Sham-EA/n= 25 |

- EA/OVX + EA - Model/OVX - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX -Sham-EA/OVX + sham-EA |

− 15 min/day for 7 days - Continuous wave, 2Hz |

BL23, EX | (i) EEG/EMG recording systems for rats and mice (WASO, REM, NREM) (ii) Serum FSH, E2 (iii) Estrogen receptor in VLPO and TMN (iv) Weight |

(i) EA increased NREM, and reduced WASO and REM (ii) EA increased E2 and decreased FSH levels (iii) No significant change in estrogen receptor (iv) EA reduced weight |

| Yu 2012117 | SD rats, 230–270g, 6–8 weeks | PMI | OVX | - EA/n= 12 - Model/n= 12 - Sham-surgery/n= 12 - Sham-EA/n= 12 |

- EA/OVX + EA - Model/OVX - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX - Sham-EA/OVX + sham-EA |

− 15 min every other day for 7 days - Continuous wave, 2Hz |

EX | (i) EEG/EMG recording systems for rats and mice (WASO, REM, NREM) (ii) Serum FSH, E2, LH |

(i) EA increased NREM and reduced WASO; no significant change in REM; EA alleviated sleep fragmentation during the daytime (ii) EA increased E2 and reduced FSH levels; no significant change in LH level |

| Yang 2017121 | SD rats, 230–270g, 6–8 weeks | PMI | OVX | - EA/n= 40 - Model/n= 40 - Sham-surgery/n= 40 - Sham-EA/n= 40 |

- EA/OVX + EA - Model/OVX - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX - Sham-EA/OVX + sham-EA |

− 15 min/day for 7 days - Continuous wave, 15Hz |

BL23, EX | (i) EEG/EMG recording systems for rats and mice (WASO, REM, NREM) (ii) serum E2 and 5-HT (iii) Adrenocortical E2 (iv) Hypothalamic 5-HT, NE, ER-α mRNA, ER-β mRNA |

(i) EA increased NREM, and reduced WASO and REM; EA alleviated sleep fragmentation during the daytime (ii) EA increased E2 and 5-HT levels (iii) EA increased E2 level (iv) EA increased 5-HT, and decreased NE and ERβmRNA; no significant change in ERαmRNA |

| Jing et al 2020174 | SD rats, 190–210g, 56–62days | PMD | (i) OVX (ii) CUMS |

- EA/n= 10 - Control/n= 10 - Model/n= 10 - Sham-surgery/n= 10 - Clomipramine/n= 10 |

- EA/OVX + CUMS + EA - Control/no treatment - Model/OVX + CUMS - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX + CUMS - Clomipramine/OVX + CUMS + Clomipramine |

− 20 min/day for 28 days-isperse-dense wave, 4/20Hz, 18V | BL23, GV20, SP6 | (i) Behavioral tests (OFT, SPT) (ii) Serum E2, LH, GnRH (iii) GSK-3β mRNA, β-catenin mRNA in hippocampus (iv) β-Catenin protein, p-β-catenin protein in hippocampus |

(i) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral tests (ii) EA increased E2, and decreased LH and GnRH levels (iii) EA decreased GSK-3β mRNA and increased β-catenin mRNA expression (iii) EA increased β-catenin protein and decreased p-β-catenin protein expression |

| Guo et al 2019145 | KM mice, 18–22g | PMD | (i) OVX (ii) CUMS |

- EA/n= 10 - Control/n= 10 - Model/n= 10 - Clomipramine/n= 10 |

- EA/OVX + CUMS + EA - Control/no treatment - Model/OVX + CUMS - Clomipramine/OVX + CUMS + Clomipramine |

− 20 min/day for 28 days- disperse-dense wave, 2/10Hz, 18V |

BL23, GV20, SP6 | (i) Behavioral tests (FST, IAT, ADE, TSE) (ii) Serum E2, FSH, LH (iii) 5-HT, NE, DA in hippocampus |

(i) EA improved mice’ depression-like behavior in behavioral tests (ii) EA increased E2 and decreased LH and FSH levels (ii) EA increased 5-HT, NE and DA levels |

| Seo et al 2018170 | SD rats, 250–300g | PMD | OVX | - EA/n= NR - Model/n= NR - Sham-surgery/n= NR -Sham-EA/n= NR |

- EA/OVX + EA - Model/OVX - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX - Sham-EA/OVX + sham-EA |

60 seconds/day for 4 days | SP6 | (i) Behavioral tests (FST, OFT, EPM) (ii) E2 and estrogen receptor expression in plasma and hippocampus (iii) BDNF and p-TrkB receptor in hippocampus (iv) NPY in hippocampus |

(i) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral tests (ii) no significant change in E2 level or estrogen receptor expression (iii) EA increased BDNF and p-TrkB receptor levels (iv) EA increased NPY levels |

| Deng et al 2017185 | SD rats, 190–210g, 56–62days | PMD | (i) OVX (ii) CUMS |

- EA/n= 12 - Control/n= 12 - Model/n= 12 - Clomipramine/n= 12 |

- EA/OVX + CUMS + EA - Control/no treatment - Model/OVX + CUMS - Clomipramine/OVX + CUMS + Clomipramine |

− 20 min/day for 28 days- disperse-dense wave, 4/20Hz, 18V |

BL23, GV20, SP6 | (i) Behavioral tests (FST, OFT) (ii) MAP-2, Notch1, Jagged1, Hes1 in hippocampus (iii) MAP-2 mRNA, Notch1 mRNA, Jagged1 mRNA, Hes1 mRNA in hippocampus |

(i) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral tests (ii) EA increased MAP-2 protein and Notch1 protein levels, and decreased Jagged1 protein and Hes1 protein levels (ii) EA increased MAP-2 mRNA and Notch1 mRNA expression, and decreased Jagged1 mRNA and Hes1 mRNA expression |

| Deng 2017177 | SD rats, 190–210g, 56–62days | PMD | (i) OVX (ii) CUMS |

- EA/n= 10 - Control/n= 10 - Model/n= 10 - Sham-surgery/n= 10 - Clomipramine/n= 10 |

- EA/OVX + CUMS + EA - Control/no treatment - Model/OVX + CUMS - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX + CUMS - Clomipramine/OVX + CUMS + Clomipramine |

− 20 min/day for 28 days- disperse-dense wave, 4/20Hz, 18V |

BL23, GV20, SP6 | (i) Behavioral tests (FST, OFT, SPT) (ii) GSK-3β, β-catenin in hippocampus (iii) β-catenin protein, p-β-catenin protein in hippocampus (iv) GSK-3β mRNA, β-catenin mRNA in hippocampus |

(i) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral tests (ii) EA decreased GSK-3β and increased β-catenin contents (iii) EA increased β-catenin protein expression; no significant change in p-β-catenin protein expression (iv) EA decreased GSK-3β mRNA and increased β-catenin mRNA expression |

| Huangfu 2018129 | SD rats, 190–210g, 56–62days | PMD | (i) OVX (ii) CUMS |

- EA/n= 10 - Control/n= 10 - Model/n= 10 - Clomipramine/n= 10 |

- EA/OVX + CUMS + EA - Control/no treatment - Model/OVX + CUMS - Clomipramine/OVX + CUMS + Clomipramine |

− 20 min/day for 28 days- disperse-dense wave, 4/20Hz, 18V |

BL23, GV20, SP6 | (i) Behavioral tests (FST, OFT, SPT, TSE) (ii) Glucocorticoid receptor, mineralocorticoid receptor in hippocampus |

(ii) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral tests (ii) EA increased glucocorticoid receptor and mineralocorticoid receptor levels |

| Jiang 2017124 | SD rats, 190–210g, 56–62days | PMD | (i) OVX (ii) CUMS |

- EA/n= 12 - Control/n= 12 - Model/n= 12 - Sham-surgery/n= 12 - Clomipramine/n= 12 |

- EA/OVX + CUMS + EA - Control/no treatment - Model/OVX + CUMS - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX + CUMS - Clomipramine/OVX + CUMS + Clomipramine |

− 20 min/day for 28 days- disperse-dense wave, 4/20Hz, 18V |

BL23, GV20, SP6 | (i) Behavioral tests (FST, SPT, TSE) (ii) Serum E2, FSH, LH, GnRH, CRH, ACTH, CORT, β-EP |

(i) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral tests (ii) EA increased E2 andβ-EP, and decreased FSH, LH, GnRH, CORT, ACTH and CRH levels |

| Jiang et al 2017127 | SD rats, 190–210g, 8–9 weeks | PMD | (i) OVX (ii) CUMS |

- EA/n= 12 - Control/n= 12 - Model/n= 12 - Sham-surgery/n= 12 - Clomipramine/n= 12 |

- EA/OVX + CUMS + EA - Control/no treatment - Model/OVX + CUMS - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX + CUMS - Clomipramine/OVX + CUMS + Clomipramine |

− 20 min/day for 28 days- disperse-dense wave, 4/20Hz, 18V |

BL23, GV20, SP6 | (i) Behavioral test (SPT) (ii) Serum E2, LH, GnRH, β-EP |

(i) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral test (ii) EA increased E2 andβ-EP, and decreased LH and GnRH levels |

| Jing et al 2018178 | SD rats, 180–220g, 17 weeks | PMD | (i) OVX (ii) CUMS |

- EA/n= 12 - Control/n= 12 - Model/n= 12 - Clomipramine/n= 12 |

- EA/OVX + CUMS + EA - Control/no treatment - Model/OVX + CUMS - Clomipramine/OVX + CUMS + Clomipramine |

− 20 min/day for 28 days- disperse-dense wave, 2/10Hz, 18V |

BL23, GV20, SP6 | (i) Behavioral test (TSE) (ii) E2, NE in hippocampus (iii) DKK1, LRP-5, LRP-6 in hippocampus |

(i) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral test (ii) EA increased E2 and NE levels (iii) EA decreased DKK1, and decreased LRP-5 and LRP-6 expression |

| Zhou et al 2015146 | SD rats, 220–260g | PMD | (i) OVX (ii) CUMS |

- MA/n= 9 - Model-1/n= 9 - Model-2/n= 8 - Sham-surgery/n= 6 - Nilestriol + Fluoxetine/n= 9 |

- MA/OVX + CUMS + MA - Model-1/OVX + CUMS - Model-2/OVX - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX - Nilestriol + Fluoxetine/OVX + CUMS + Nilestriol + Fluoxetine |

20 min/day for 21 days | BL23, GV20, SP6 | (i) Behavioral test (OFT) (ii) 5-HT, NE, DA in hypothalamus |

(i) MA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral test (ii) MA increased 5-HT level; no significant changes in NE and DA levels |

| Shi et al 2012147 | SD rats, 300–350g, 4 months | PMD | (i) OVX (ii) CUMS |

- MA/n= 10 - Model/n= 5 - Sham-surgery/n= 5 - Estradiol benzoate/n= 10 |

- MA/OVX + CUMS + MA - Model/OVX + CUMS - Sham-surgery/sham-OVX + CUMS - Estradiol benzoate/OVX + CUMS + Estradiol benzoate |

30 min/session, once session every 2 days for total 30 sessions | CV4, CV6, LI4, LR3, PC6, SP6, ST36 | (i) Serum E2 (ii) 5-HT in hypothalamus |

(i) EA increased E2 level (ii) EA increased 5-HT level |

| Sun 2009118 | (i) SD rats, 250–300g, 11–15 months (n= 45) (ii) Young SD rats, 150–200g, 4 months (n= 10) |

PMD | CUMS | - EA/n= 15 - Model/n= 15 - Clomipramine/n= 15 - Young/n= 10 |

- EA/CUMS + EA - Model/CUMS - Clomipramine/CUMS + Clomipramine - Young/CUMS |

− 20 min/day for 7 days- disperse-dense wave, 4/20Hz, 2V |

BL18, BL23, GV20, SP6 | (i) Behavioral tests (OFT) (ii) Serum E2, NE |

(i) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral test (ii) EA increased E2 and NE levels |

| Wang et al 2016171 | SD rats, 220–260g, 17weeks | PMD | (i) OVX (ii) CUMS |

- EA/n= 10 - Control/n= 10 - Model/n= 10 - Clomipramine/n= 10 |

- EA/OVX + CUMS + EA - Control/no treatment - Model/OVX + CUMS - Clomipramine/OVX + CUMS + Clomipramine |

− 20 min/day for 28 days- disperse-dense wave, 2/10Hz |

BL23, GV20, SP6 | (i) Behavioral test (OFT) (ii) CREB, BDNF in hippocampus |

(i) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral test (ii) EA increased BDNF and CREB levels |

| Wu 2012148 | (i) SD rats, 260–471g, 11–13 months (n= 73) (ii) Young SD rats, 140–191g, 4 months (n= 20) |

PMD | CUMS | - EA/n= 18 - Model/n= 19 - Clomipramine/n= 18 - Herbal medicine/n= 18 - Young/n= 20 |

- EA/CUMS + EA - Model/CUMS - Clomipramine/CUMS + Clomipramine - Herbal medicine/ CUMS + XiaoYao-Pill - Young/CUMS |

− 20 min/day for 10 days- disperse-dense wave, 2/15Hz, 2V |

BL18, BL23, GV20, SP6, ST36 | (i) Behavioral test (OFT) (ii) Serum E2 (iii) 5-HT2A mRNA, p-ERK 1/2 in hippocampus |

(i) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral test (ii) EA increased E2 level (ii) EA decreased 5-HT2A mRNA expression; EA increased p-ERK 1/2 expression |

| Zhang 2009128 | (i) SD rats, 250–300g, 11–15 months (n= 45) (ii) Young SD rats, 150–200g, 4 months (n= 10) |

PMD | CUMS | - EA/n= 15 - Model/n= 15 - Clomipramine/n= 15 - Young/n= 10 |

- EA/CUMS + EA - Model/CUMS - Clomipramine/CUMS + Clomipramine - Young/CUMS |

− 20 min/day for 7 days- continuous wave, 20Hz, 2V |

BL18, BL23, GV20, SP6 | (i) Behavioral test (OFT) (ii) Serum E2 (iii) β-EP in hippocampus |

(i) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral test (ii) EA increased E2 level (ii) EA increased β-EP level |

| Zhao et al 2011149 | (i) SD rats, 260–471g, 11–13 months (n= 66) (ii) Young SD rats, 140–191g, 4 months (n= 20) |

PMD | CUMS | - EA/n= 15 - Model/n= 18 - Clomipramine/n= 17 - Herbal medicine/n= 16 - Young/n= 20 |

- EA/CUMS + EA - Model/CUMS - Clomipramine/CUMS + Clomipramine - Herbal medicine/ CUMS + XiaoYao-Pill - Young/CUMS |

− 20 min/day for 28 days | BL18, BL23, GV20, SP6, ST36 | (i) Behavioral test (OFT) (ii) Serum 5-HT, HDL |

(i) EA improved rats’ depression-like behavior in behavioral test (ii) EA increased 5-HT and HDL levels |

| Song et al 2021119 | KM mice, 18–22g, 5–6 weeks | PMD | (i) OVX (ii) Ice-water swimming stimulation (I-WSS) |

- EA/n= 10 - Control/n= 10 - Model/n= 10 |

- MA/OVX + I-WSS + MA - Control/I-WSS - Model/OVX + I-WSS |

− 30 min/day, 6 days/week for 4 weeks | CV4, KI3, KI15, SP6, SP10, ST36 | Serum E2 | EA increased E2 level |