Abstract

Objective of the present investigation comprised of the application of in silico methods to discover novel natural product (NP) based potential inhibitors for carbohydrate mediated diseases. Structure based drug design studies (molecular docking and structure based pharmacophore analysis) were carried out on a series of natural product compounds to identify significant bioactive molecules to inhibit α-mannosidase (I and II) and β-galactosidase enzymes. Furthermore, protein ligand interaction fingerprint analysis, molecular dynamics simulations and molecular access system (MACCS) fingerprint analysis were performed to understand the binding behaviors of the studied molecules. The results derived from these analyses showed that the identified compounds exhibit significant binding interactions with the active site residues. The compounds, NP-51, NP-81 and NP-165 have shown significant docking score against the studied enzymes (α-mannosidases-I, α-mannosidases-II and β-galactosidases). The fingerprint studies showed that the presence of rings (aromatic or aliphatic) with sulfur atoms, nitrogen atoms, methyl groups, etc. have favorable effects on the α-mannosidase II inhibitory activity. However, the presence of halogen atoms substituted in the molecules have reduced inhibitory ability against α-mannosidase II. The compound, NP-165 has significant activity against both enzymes (α-mannosidases and β-galactosidases). These studies accomplished that the compounds identified through in silico methodologies can be used to develop semisynthetic derivatives of the glycosidase inhibitors and can be screened for the treatment of different carbohydrate mediated diseases.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40203-021-00115-9.

Keywords: Mannosidase II inhibitors, β-galactosidase, Docking, Structure based pharmacophore analysis, MD simulations, Natural products

Introduction

The discovery of bioactive compounds for the treatment of carbohydrate mediated diseases is one of the important research areas in medicinal chemistry. Carbohydrate digesting enzymes are vital targets for the discovery of medicines for the treatment of diabetics, cancer, HIV, etc. Glycosidase family enzymes play important role in the biosynthesis of many important biomolecules, such as N-linked oligosaccharides, glycoproteins, glycolipids, etc. The inhibitors of glycosidases are known to possess a large number of therapeutic effects, such as antitumor, antidiabetics, antiviral, immunoregulatory, etc. In endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the process starts with the attachment of Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 to a nascent protein, subsequently α-glucosidases (EC 3.2.1.20) (I and II) remove two glucose units. After trimmed, the Glc1Man9GlcNAc2 epitope passes through calnexin/calreticulin cycle for folding of proteins, while the unfolded proteins undergo degradation by the ER mannosidases (Moorthy et al. 2012a; Caramelo and Parodi 2008; Helenius and Aebi 2004; Ieyama et al. 2011). α-Mannosidase I (EC 3.2.1.113) trims the oligosaccharide precursor to Man8GlcNAc2 and in Golgi apparatus, the remaining α-linked mannose residues are removed by α-mannosidase II (EC 3.2.1.114). The α-mannosidase cleaves the α-linked mannose residues from the non-reducing end during the ordered degradation of N-linked glycoproteins (Moorthy et al. 2012b; Park et al. 2008; Rawling et al. 2009; Olszewska et al. 2012). α-Galactosidase (EC 3.2.1.22) is a homodimeric glycoprotein that hydrolyses the terminal α-galactosyl moieties from polysaccharides, glycolipids and glycoproteins (Liu et al. 2007; Olsson and Clausen 2008). In humans, the absence of functional α-galactosidase leads to the accumulation of galactosylated substrates in the tissues, leading to Fabry disease (Guce et al. 2010; Garman and Garboczi 2004). β-Galactosidase (EC 3.2.2.23) is a glycoside hydrolase enzyme localized in the lysosome, which catalyzes the hydrolysis and transglycosylation of β-d-galactosidases in oligosaccharide chains of glycolipids, glycoproteins and glycosaminoglycans (Husain 2010; Douglas et al. 2012). These biosynthesised products mediate several diseases, hence the inhibition of these enzymes can block its biosynthesis. The in silico studies on these targets and the inhibitory effects by molecules can provide important informations required for the design and development of novel molecules.

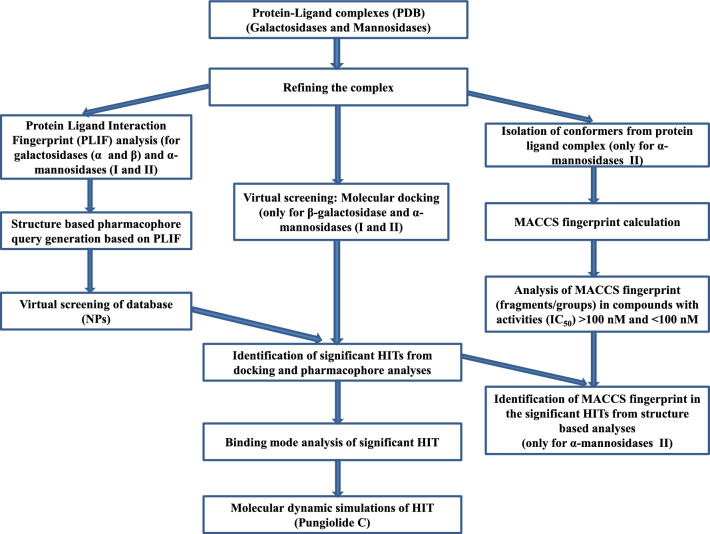

Computer based screening of large chemical (drug) databases may yield significant HITs in a fast and reliable way. Generally, ligand and structure based virtual screening approaches are used to screen large databases with the aid of different softwares. Now a days commercial and many open access softwares are available for drug design, bioinformatics and biomolecular studies. Sanchez-Linares et al. (2012) has used BINDSURF virtual screening methodology to scan whole protein surface to identify hotspots and binding sites of the proteins. The Lead Finder Docking Program has been utilized to investigate ligand–protein coupling mode and to deliver oxaliplatin in cancer cells and the METADOCK program has been used to virtual screen compounds under parallel metaheuristic scheme (Ceron-Carrasco et al. 2014; Imbernon et al. 2017). Further MOE, Schrodinger, Flex screen docking software package, etc. are used for virtual screen and design of novel molecules (Martinez-Ballesta et al. 2016; Perez-Sanchez et al. 2016; Navarro-Fernandez et al. 2012; Moorthy et al. 2014). With the consideration of the above informations, in the present investigation, we have screened (in silico) a dataset comprised of natural product molecules (NPs) against galactosidase and mannosidase enzymes. Traditionally NPs have played an important role in drug discovery and were the basis for most of the early medicine development. In the world market, NPs and NP-derived drugs are represented as one of the top selling ethical drugs and have been used in therapeutic areas such as oncology, immunosuppression, metabolic diseases, etc. (Butler 2004, 2005; Moorthy et al. 2014). In the present study, the structure based (docking, structure based pharmacophore and PLIF) and MACCS fingerprint analysis were applied as per the protocol presented in Fig. 1 (Moorthy et al. 2015; Loving et al. 2009; Sanders et al. 2011).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for the present investigation

Methodology

Molecular docking (virtual screening)

The X-ray crystallographic structures of β-galactosidase (1JYX code at 1.75 Å of resolution), α-mannosidase I (1FO2 code at 2.4 Å of resolution) and α-mannosidase II (1HWW code at 1.9 Å of resolution) were retrieved from Protein Data Bank [http://www.rcsb.org]. These enzymes complexed with IPTG, 1-deoxymannojirimycin and swainsonine molecules respectively. All crystallographic water and ligand molecules were removed to obtain the unbound geometries of enzymes. Hydrogen atoms were added to the enzymes in order to have the residues in their physiological protonation state. Ligand–protein docking calculations were performed with the VsLab software (Cerqueira et al. 2011) that uses the AutoDock 4.2 software (Morris et al. 1998) and VMD 1.8.6 program was used for visual inspection and analysis (Humphrey et al. 1996). The docking protocols for both α-mannosidase I (Man I) and α-mannosidase II (Man II) enzymes have already been tested and validated in our previous work (Moorthy et al. 2012b). KIF and DMNJ to the a-mannosidase I active site, as well as the DMNJ and SWA inhibitors to the a-mannosidase II active site to validate the docking study. The average RMSD values obtained for a-mannosidase I complex with KIF and DMNJ inhibitors, as well as a-mannosidase II complex with DMNJ and SWA drugs were 0.974 ± 0.003 Å and 0.822 ± 0.003 Å, 0.866 ± 0.019 Å and 0.468 ± 0.001 Å, respectively (Moorthy et al. 2012b).

Hence, the similar protocol was used to dock NPs into these enzymes. Kollman partial charges were assigned to all atoms in the protein, while for the magnesium and sodium ions, formal charges of + 2 and + 1 were applied, respectively. The grid maps were centered into the ligand molecule and comprised 51 × 51x51 points of 0.375 Å spacing. The Lamarckian genetic algorithm was employed with the following parameters: population size of individuals: 150; maximum number of energy evaluations: 2.5 × 106 and maximum number of generations: 27,000. For all the calculations, 50 docking rounds were performed with a step sizes of 2.0 Å for translations and with orientations and torsions of 5.0°. Docked conformations were clustered within 2.0 Å root-mean-square-deviations (RMSD) to prevent similar poses, and visual analysis was also used to eliminate unfavorable poses and interactions.

In order to validate the docking protocol for the β-galactosidase study, we have performed an initial docking of the crystallographic ligand (IPTG) into its active site pocket. Figure SI-1 in Supporting Information shows the superposition of both geometries (X-ray and best predicted docking solution). A very similar pose was obtained with the RMSD value of 3.0 Å (1.7 Å for the sugar ring), which is a suitable value for sugar molecule due to the presence of their various flexible hydroxyl groups. In this specific case, the sugar ring and the sulfur atom are in the correct position, but the orientation of the bulky -CH(CH3)2 group is slightly different, and subsequently, increased the RMSD values. However, the monosaccharide ring possessed the correct pose and it has considered that this docking protocol is able to predict the binding mode of inhibitors (including NPs) into the β-galactosidase active site.

Protein ligand interaction fingerprint (PLIF) analysis

PLIF analysis was performed with the X-ray crystallographic structures obtained from Protein Data Bank using MOE software (MOE 2011). The ligand interacting residues obtained from the pdb were used for the structure based pharmacophore generation. PLIF possesses a composition of seven visible fingerprint bits [side chain hydrogen bond donor (D), side chain hydrogen bond acceptor (A), backbone hydrogen bond donor (d), backbone hydrogen bond acceptor (a), solvent hydrogen bond (O), ionic interaction (I) and surface contact (C)] (MOE 2011).

In this analysis, the following glycosidase enzymes and protein ligand complexes (pdb codes) were used for the PLIF calculations: α-Galactosidase: 3 structures (3GXP, 3GXT and 4NXS); β-Galactosidase (human): 6 structures (3THC, 3THD, 3WEZ, 3WF0, 3WF1 and 3WF2); β-Galactosidase (E coli): 4 structures (1JYX, 1JZ5, 1JZ6 and 1JZ7); α-Mannosidase I: 3 structures (1FO2, 1FO3 and 1X9D); and α-Mannosidases II: 41 structures (1HTY, 1HWW, 1HXK, 1PS3, 1QWN, 1R33, 1R34, 1TQS, 1TQT, 1TQU, 1TQV, 1TQW, 2ALW, 2F1A, 2F1B, 2F7O, 2F7P, 2F7Q, 2F7R, 2F18, 2FYV, 2OW6, 2OW7, 3D4Y, 3D4Z, 3D50, 3D51, 3D52, 3DDF, 3DDG, 3DX0, 3DX1, 3DX2, 3DX3, 3DX4, 3EJP, 3EJQ, 3EJR, 3EJS, 3EJT and 3EJU). The protonated complexes were superimposed and the common interaction fingerprints were calculated.

Structure based pharmacophore development and virtual screening

Structure based pharmacophore contours were developed for each enzymes separately. It considers the interaction fingerprint retrieved directly from the protein–ligand interactions in 3D space. The pharmacophore query generator tool in the module was used to generate pharmacophore contours. The pharmacophore feature points were grouped and filtered according to their interaction and the groups which have sufficiently tight binding can be converted into a pharmacophore contours. The excluded volume of the pharmacophore feature was also included in the structure based virtual screening of the molecules. The pharmacophore queries used for the virtual screening is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pharmacophore query points and its radius considered for virtual screening

| Code | α-Galactosidase | Human β-Galactosidase | E coli β-Galactosidase | α-Mannosidase I | α-Mannosidase-II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophores | Radius (Å) | Pharmacophores | Radius (Å) | Pharmacophores | Radius (Å) | Pharmacophores | Radius (Å) | Pharmacophores | Radius (Å) | |

| F1 | Don&Acc&ML | 2 | Don&Acc&ML | 2 | Acc&ML | 1.5 | Don&Acc&ML | 1.5 | Don&Acc&ML | 2 |

| F2 | Don&Acc&ML | 2.5 | Don&Acc&ML | 2 | Don&Acc&ML | 1.5 | Don&Acc&ML | 1.5 | Don&Acc&ML | 2 |

| F3 | Don&Acc | 2 | Don&Acc&ML | 2 | Don&Acc&ML | 2.5 | Don&Acc&ML | 2 | Don | 1.5 |

| F4 | Don | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Acc&ML|Don&Acc&ML | 2 |

| + V Excl | – | 1.5 | – | 1.5 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 |

+ V Excl is excluded volume

MACCS fingerprint analysis

Molecular access system (MACCS) fingerprints were calculated using PaDEL software (Yap 2011). It provides one of the 166 MACCS structural keys (fragments or groups) computed from the molecular graph.

Molecular dynamic (MD) simulations

Each protein:NP-165 complexes obtained from the molecular docking study were used as the starting point for the MD simulations. In order to neutralize the high negative charges, 31, 4 and 7 counter-ions (Na+) were employed for β-galactosidase (βGal), α-mannosidase I (ManI) and α-mannosidase II (ManII) systems, respectively using X-Leap tool. An explicit solvation model with pre-equilibrated TIP3P water molecules filling a truncated rectangular box with a minimum 12 Å distance between the box faces and any atom of the protein. The size of the three βGal:NP-165, ManI:NP-165 and ManII:NP-165 systems were approximately 189,000; 52,300 and 124,300 atoms, respectively. The antechamber tool was used to parameterize the NP-165 compound, which was optimized with the HF/6-31G(d) level of theory by using the Gaussian 09 suite of programs (Frisch et al. 2009). The RESP algorithm (Bayly et al. 1993) was used to recalculate the atomic charges. All geometry optimizations and MD simulations were performed with the parameterization adopted in AMBER 12.0 simulations package (Case et al. 2012), using the ff99SB (Hornak et al. 2006) and GAFF (Wang et al. 2004) force fields to characterize the proteins and the NP-165 compound, respectively. The initial geometry optimization of all systems occurred in two steps, in order to release the bad contacts in the crystallographic structures. First, the protein was kept fixed and only the position of the water molecules and counter-ions was minimized (500 steps using the steepest descent algorithm and 1500 steps were carried out using conjugate gradient). Second, the full system was minimized (5000 steps using the steepest descent algorithm and 10,000 steps carried out using conjugate gradient). Then, the MD simulation of 100 ps at constant volume and temperature, and considering periodic boundary conditions was run, followed by 25 ns of MD simulation with an isobaric-isothermal ensemble for each system. In these, the Langevin dynamics was used (collision frequency of 1.0 ps−1) to control the temperature at 310.15 K (Izaguirre et al. 2001) and the Berendsen Barostat to define a pressure of 1 atm. All simulations presented here were carried out using the PMEMD module, implemented in the AMBER 12.0 simulations package. Bond lengths involving hydrogen were constrained using the SHAKE algorithm and the equations of motion were integrated with a 2 fs time-step using the Verlet leapfrog algorithm (Ryckaert et al. 1977). The Particle-Mesh Ewald (PME) method (Essmann et al. 1995) was used to include the long-range interactions, and the non-bonded interactions were truncated with a 10 Å cutoff. The MD trajectory was saved every 2 ps and the MD results were analysed with the PTRAJ module of AMBER 12.0.

In silico ADMET studies

In silico ADMET studies were performed on the compounds using SwissADME free web tool (Daina et al. 2017; Daina and Zoete, 2016) and Pallas software (Pallas 2000).

Enzyme inhibitory activity

The enzymatic activities of α-mannosidase and β-galactosidase were determined colorimetrically by monitoring the release of p-nitrophenol from the P-Nitrophenyl-α-d-mannopyranoside and o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (Sigma, USA) respectively (Li et al. 2005). The release of p-nitrophenol and o-nitrophenol from a 1.5 mM solution (18 mg/mL stock solution) of P-Nitrophenyl-α-d-mannopyranoside and O-nitrophnyl-β-d-galactopyranoside respectively in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) at 65 °C. The substrate (1 mL) was pre-incubated at the required temperature and the reaction was initiated by the enzyme (0.125 U/mL). After 10 min of incubation, the reaction was stopped using 1 mL of 1 M sodium carbonate solution. The absorbance at 405 nm was determined by Shimadzu UV spectrophotometer (Japan) (Gholamhoseinian et al. 2008; Li et al. 2005; Guven et al. 2011).

Results and discussions

Molecular docking (virtual screening) and MD simulations

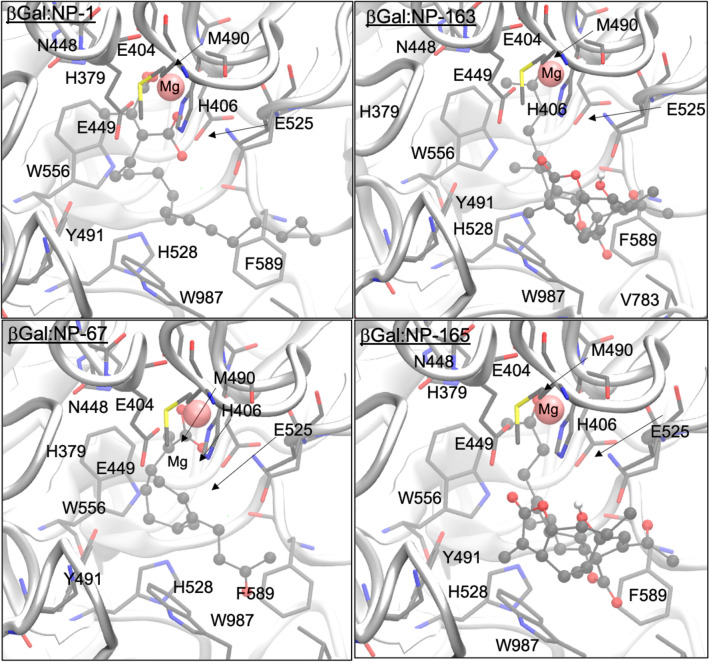

Virtual screening studies of a collection of 165 natural product molecules obtained from literatures (called here as NPs database) were carried out towards the β-galactosidase, α-mannosidase I and α-mannosidase II enzymes. The docked compounds were ranked according to their binding free energy values. Table SI-1 in Supporting Information shows the binding free energy and inhibitory constant values of best top-20 docking-predicted compounds against three glycosidase enzymes. The four best compounds interact to β-galactosidase enzyme are NP-1, NP-67, NP-163 and NP-165. Figure 2 shows the structural interactions established between the β-galactosidase and NPs. It has noticed that all these molecules interacted directly with the catalytic magnesium, which reinforcing the importance of this ion for substrates/compounds binding. The carboxylic groups (two) of NP-1 interacted with the divalent cation for its higher binding affinity. The NP-67 also interacted through carboxylic group, whilst the NP-163 and NP-165 molecules interacted with one carbonyl group. Furthermore, it was observed that the main hydrophilic residues that contribute to an efficient binding are the His406, Asn448 and Glu449. The interactions between compounds and Glu449 is especially important because it is the acid residue directly involved in the catalytic mechanism (Cerqueira et al. 2011; Bras et al. 2010). In addition, the residues involved in hydrophobic (VdW and π–π stacking) contacts with these four NPs are Val91, His379, Met411, Met490, Tyr491, His528, Trp556, Val783 and Trp987. Most of these residues are also involved in the substrate binding during the reaction mechanism, which suggests that interactions with them should improve the binding affinity.

Fig. 2.

Representation of the best Top-4 docking-predicted ranked for the βGal enzyme

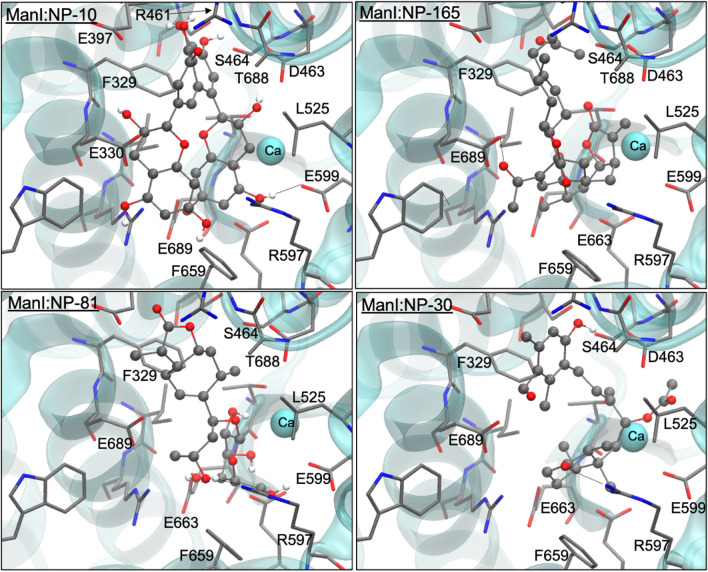

The best four molecules which inhibit α-mannosidase I are NP-10, NP-30, NP-81 and NP-165. Figure 3 shows the intermolecular interactions occurred in ManI:NP complex. As seen, all these compounds established many contacts with the residues present in the binding site of α-mannosidase I. They made several hydrophobic contacts with the Trp295, Phe329, Ile334, Leu595, Pro598 and Phe659 residues, and H-bonding interaction with Glu330, Arg334, Thr394, Glu397, Arg461, Asp463, Ser464, Leu525 (carbonyl of backbone), Arg597, Glu599, Glu663, Thr688 and Glu689 residues. In addition, they also electrostatically interacted with the structural calcium cation, which improve their binding affinity to this target. Interactions with the Asp463, Ser464, Glu602, Glu663 and Thr688 residues were also previously reported by Sivapriya et al. (2007) and Moorthy et al. (2012b) as being crucial for the binding of thiosugars and pyrrolidine derivative as potential inhibitors, respectively. Although the NP-10 does not interact directly to the cation, it is the compound with more hydroxyl groups, and subsequently, it establishes much more H-bonds with the active site residues (9 H-bonds). This may be the reason for its higher affinity for α-mannosidase I and the remaining compounds are in close contact with the calcium cation, which can enhance their binding affinity.

Fig. 3.

Representation of the best Top-4 docking-predicted ranked for the α-mannosidase I enzyme

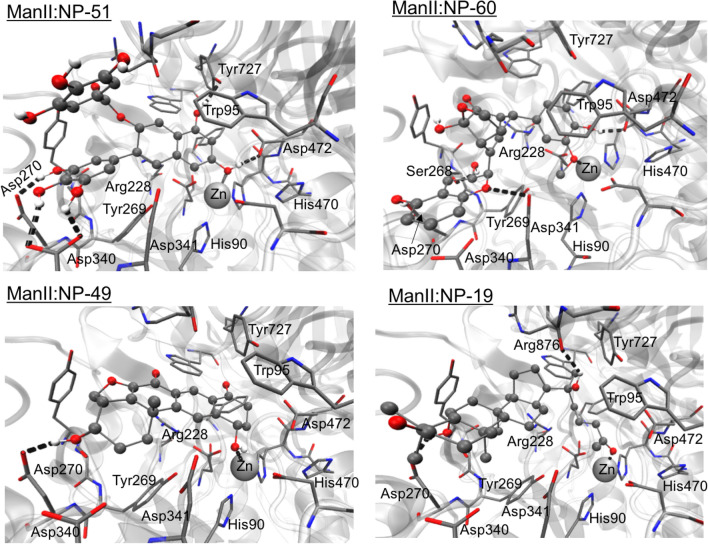

The four-top ranked compounds to α-mannosidase II binding are NP-19, NP-49, NP-51 and NP-60. Figure 4 shows the interactions established between these molecules and the binding site residues of α-mannosidase II. It was observed that the hydrophilic (H-bonds and electrostatic) interactions are established with Arg228, Asp240, Ser268, Tyr269, Asp270, Asp340, Asp341, Asp472, Tyr727 and Arg876 (carbonyl group) residues, and zinc (cation). Most of the hydrophobic contacts are established with the aromatic residues such as Phe206, Tyr267, Tyr269, Trp415 and Tyr727. NP-51 is a derivative of catechin polyphenolic family has three hydroxyl groups of its ring B (catechin nomenclature), make several H-bonds with the active site residues of this enzyme, as well as another hydroxyl group is directed to the zinc cation. These facts may be responsible for its higher binding efficiency. Both NP-19 and NP-49 compounds possess many hydrophobic rings and the NP-19 also has an extended aliphatic chain. Hence, binding of these compounds to α-mannosidase II occurs mainly by hydrophobic and dispersive contacts, in addition to the electrostatic contact to the divalent cation. This binding mode agrees with literature, in which Kuntz et al. (2009 and 2010) and Moorthy et al. (2012b) have pointed out that the interactions observed with the zinc cation and the residues. The hydrophobic binding cavity of α-mannosidase II is responsible for the strong binding affinity to this enzyme.

Fig. 4.

Representation of the best Top-4 docking-predicted ranked for the α-mannosidase II enzyme

The three enzymes (β-galactosidase, α-mannosidase I and α-mannosidase II) belong to the same glycosidase (GH) family and all these enzymes cleave the glycosidic bonds established between glucose or mannose monosaccharides. As expected, the characters of the residues present in the active sites of these enzymes are also similar, although they may have different catalytic mechanisms, all of them possess two carboxylic residues (Asp or Glu) and many aromatic residues (Tyr, Phe and Trp) around the binding pocket to pack the sugar rings of the substrates. For this reason, in general, a good inhibitor for one glycosidase enzyme is also able to bind and inhibits other glycosidases (it may show different affinities). This fact is observed in many well-known drugs for this kind of enzymes (Bras et al. 2014). In this context, we have analyzed the compounds of Table SI-1 that are common for the three enzymes. Table 2 shows the “common” top-10 docking-predicted compounds, in which the first four (highlighted in bold) are good potential inhibitors for the three enzymes and the last six compounds are potential inhibitors only for two of these enzymes. Figures SI-2, SI-3 and SI-4 display the interactions established between the NP-10, NP-51, NP-81 and NP-165 molecules and the binding pockets of β-galactosidase, α-mannosidase I and α-mannosidase II, respectively. The binding modes and intermolecular structural interactions adopted by these molecules within the enzymatic binding pockets are similar to the ones described previously. However, the NP-10, NP-51 and NP-81 compounds do not establish any electrostatic interaction with the magnesium cation of β-galactosidase. In addition, their size is bigger than NP-165, and some groups projected outside the β-galactosidase active site which interacted with the solvent molecules. These two facts may justify their lower binding affinities for this enzyme, in comparison with the interaction obtained for the NP-165. Concerning the α-mannosidase I, three of these “common” compounds belong to the top-4 rank that are specific to this enzyme. Since the NP-51 has many hydroxyl groups, it directs to the calcium ion. However, as NP-81 and NP-10 have high sizes, they also interact with solvent molecules that are around the binding pocket of α-mannosidase II.

Table 2.

Top-10 best docking-predicted NPs that are common for two or three of the studied glycosidases (β-galactosidase, α-mannosidase I and α-mannosidase II)

| NPs | β-Galactosidase | α-Mannosidase I | α-Mannosidase II | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Ki (µM) | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Ki (µM) | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Ki (µM) | |

| NP-165 | − 9.96 | 0.05 | − 8.81 | 0.35 | − 7.64 | 2.51 |

| NP-81 | − 9.32 | 0.15 | − 8.52 | 0.57 | − 7.49 | 3.23 |

| NP-51 | − 9.02 | 0.24 | − 8.43 | 0.66 | − 8.57 | 0.52 |

| NP-10 | − 8.80 | 0.35 | − 9.47 | 0.11 | − 7.53 | 3.02 |

| NP-99 | − 9.55 | 0.10 | − 7.20 | 5.27 | − 7.83 | 1.82 |

| NP-62 | − 7.77 | 2.01 | − 7.77 | 2.01 | − 7.81 | 1.88 |

| NP-76 | − 9.06 | 0.23 | − 7.92 | 1.56 | − 6.64 | 13.6 |

| NP-60 | − 7.98 | 1.41 | − 8.16 | 1.04 | − 8.46 | 0.63 |

| NP-55 | − 7.81 | 1.88 | − 8.16 | 1.04 | − 7.58 | 2.77 |

| NP-30 | − 8.43 | 0.66 | − 8.47 | 6.18 | − 7.57 | 2.82 |

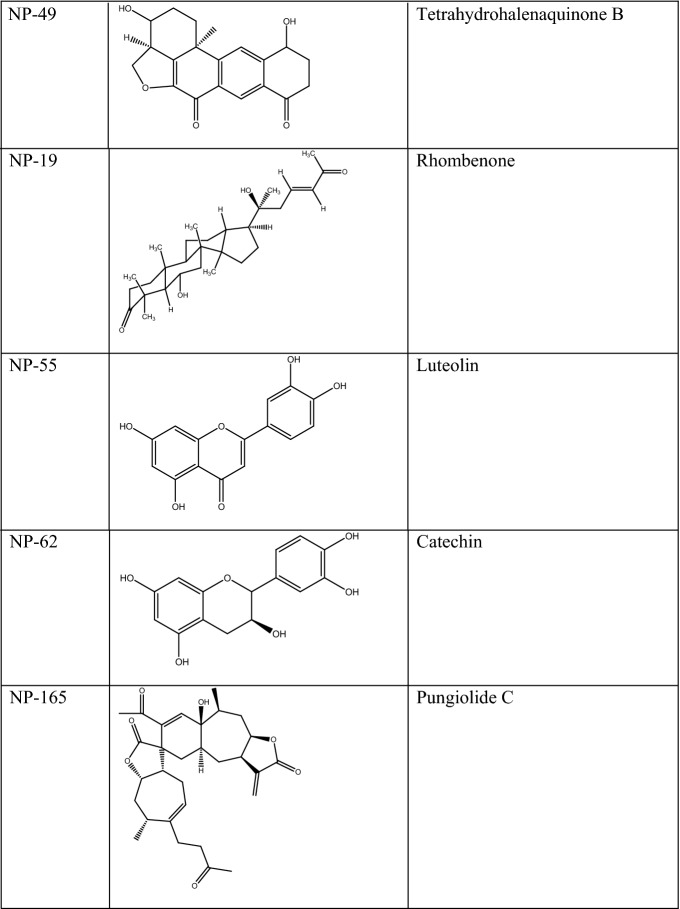

Interestingly, both NP-165 and NP-51 were identified as HIT molecules through the structure based approach, which enhances the importance of these two potential glycosidase inhibitors. The NP-51 is one of the analogues of epigallocatechin-3-gallate compound (has a carbon atom instead and the oxygen atom in the AC ring (catechin nomenclature), which is the ester of epigallocatechin and gallic acid. These molecules are most abundantly present in tea and they are pointed out as active molecules on different targets including cancer, HIV and infectious diseases. NP-165 corresponds to pungiolide C, which is a xanthanolide diol derivative that possesses antimicrobial and anticancer activities.

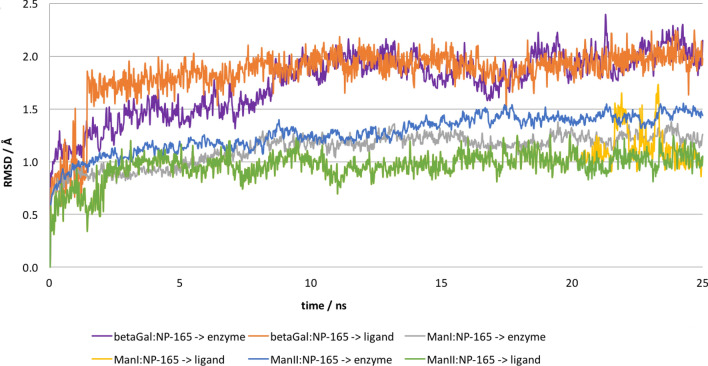

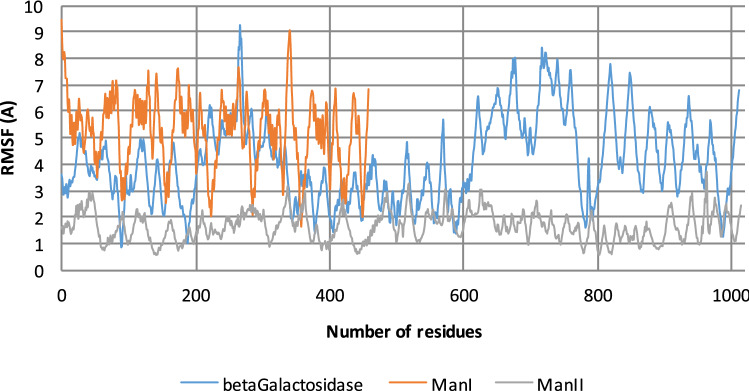

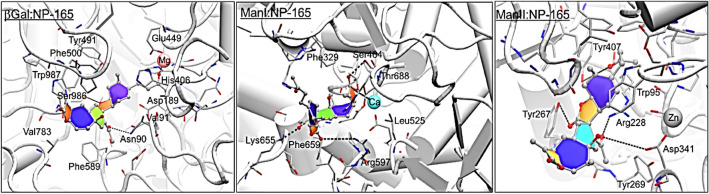

The best binding free energy value was obtained with the NP-165 compound, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations were also performed on glycosidases: NP-165 complexes in order to evaluate their stability along time. The MD analysis results revealed that the NP-165 compound remained in the glycosidases binding sites throughout the entire simulations (as evidenced by the RMSD values for the backbone of each enzyme and for NP-165 that are illustrated in Fig. 5). These small RMSD values (around 2.0 and 2.5 Å) suggest that NP-165 stabilises the intermolecular interactions within various glycosidase active sites. Figure 6 shows the root-mean-square-fluctuation (RMSF) values for each enzyme by residue number, along the entire MD simulations. According to this data, the residues that interacted with the NP-165 have low fluctuation, which reinforce the stability of the glycosidase:NP165 complexes. Figure 7 illustrates the closest to the average geometry of each βGal:NP-165, ManI:NP-165 and ManI:NP-165 complexes. In the βGal:NP-165 complex, the main H-bonds occur between the oxygen atoms and hydroxyl group of NP-165 and the hydrophilic groups of Asn90, His406, Asn448 and Glu449 and Ser986 residues. Many hydrophobic interactions also occur, such as a stacking effect of π–π interactions between the rings of NP-165 and Tyr491, Phe500, Trp556, Phe589 and Trp987, as well as dispersive contacts between the aliphatic groups of NP-165 and several non-polar residues of β-galactosidase (Val91, Met411, Met490 and Val783). All of these interactions strongly contributed to the high stability of the complex. The H-bond established with the Ser986 has the highest time occupancy during the MD simulation, which reinforces its key role in β-galactosidase inhibition by mimicking the binding mode of natural substrates.

Fig. 5.

Representation of the RMSD values obtained for backbone of all enzymes [βGal (purple), ManI (gray) and Man II (blue)] and for the NP-165 during the MD simulation of each complex [βGal:NP-165 (orange), ManI:NP-165 (yellow) and ManII:NP-165 (green)]

Fig. 6.

Representation of the RMSF values obtained by residues number, for β-Gal (blue), Man I (orange) and Man II (gray) enzymes during each respective MD simulation

Fig. 7.

Representation of the interactions established in the binding pockets of βGal:NP-165, ManI:NP-165 and ManI:NP-165 complexes (after MD simulations)

As observed, the main intermolecular interactions occurred through the MD simulations of ManI:NP-165 complex are similar (one additional H-bond with Arg655) to the ones observed in the docking solution. The potential inhibitor interacts with the structural calcium establishes several H-bonds with the Ser464, Arg597 (with the highest time occupancy during the MD simulation), Arg655 and Thr688 residues. The side chains of Phe329, Ile334, Leu525, Pro598 and Phe659 residues also made several vdW interactions and π-π stacking contacts with the ring and aliphatic groups of NP-165.

Throughout the MD simulations of ManII:NP-165 complex, the natural compound ceased to interact with the zinc cation and directs its carbonyl group towards the hydroxyl group of Tyr407. It also makes H-bonds with the Arg228, Tyr267 and Asp341 residues and their rings contact with the side chains of Trp95, Phe206, Tyr267, Tyr269, Leu295, Trp415 and Tyr727 residues by several hydrophobic interactions. The H-bond has highest time occupancy during the MD simulations which is stabilized with the Tyr267, which indicates that this residue has a key role for the ligand binding affinity. Other studies with known α-mannosidase inhibitors (e.g. mannostatin A) suggested that interactions with the zinc cation, Asp92, Trp95, Phe206, Arg228, Tyr269, Asp341, Trp415, Asp472, Tyr727 and Arg876 residues are important for an efficient binding and inhibitory activity (Kawatkar et al. 2006; Nour et al. 2009). Since the NP-165 interacted with most of these residues, which suggested that this compound has a strong affinity for this target and it may have a potential inhibitory effect.

In order to evaluate the interactions with the solvent, we also determined the number of water molecules that exist around the NP-165 compound in each MD simulations. Therefore, the natural compound of βGal:NP-165, ManI:NP-165 and ManII:NP-165 complexes has 23 ± 4, 31 ± 6 and 29 ± 3 in a radius of 3.5 Å; as well as 44 ± 6, 53 ± 9 and 50 ± 4 in a radius of 5.0 Å, respectively. These results showed that the binding pockets of mannosidase enzymes are superior and more exposed than β-galactosidase. A large number of water molecules around the potential inhibitor in the ManII:NP-165 agrees with our previous study, in which it was verified that the interaction with solvent molecules is relevant for the inhibition of ManII (Moorthy et al. 2012b). All these computational results provide very useful structural data to understand the affinity between natural molecules and the β-galactosidase, α-mannosidase I and α-mannosidase II enzymes.

PLIF analysis

Protein ligand interaction fingerprint analysis was performed for all the β-galactosidase and α-mannosidase enzymes (protein–ligand complex obtained from Protein Data Bank). The results derived from the PLIF analyses are provided in Table 3 and Table SI-2. The results showed that the side chain donor (ChDon) and the side chain acceptor (ChAcc) groups have intense interactions in all the enzymes studied. The α-galactosidase-ligand complexes (3 structures) show that the side chain donor group interacts with the Asp92, Asp93, Asp170, Glu203 and Asp231 residues and the side chain acceptor interaction occurs with Lys168 and Arg227 residues. An acidic residue, Asp170 also has an ionic type of interaction with the charged functional groups present in the molecules. The PLIF analyses for β-galactosidase-ligand complexes were performed with the enzymes obtained from E. coli (4 structures) and human (6 structures). Interestingly, the residues contributed for the interactions are quite different in both species. In human, Tyr83, Asn187, Tyr303 and Tyr306 residues do have side chain donor and acceptor interactions. In addition, the glutamic acid residue (Glu129) has side chain donor and ionic interaction and other residues such as Ile126 and Ala128 have backbone donor and acceptor interactions. The β-galactosidase-ligand complexes of E. coli have shown side chain donor and acceptor interactions and it does not show any backbone and ionic type of interactions. Asn102, His391 and His540 residues exhibited both side chain donor and acceptor type interactions, however, Asn460 and Trp568 possessed side chain acceptor interactions with the molecules.

Table 3.

The type of protein ligand interaction and the residues

| Type of interaction | Residues | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Galactosidase | β-Galactosidase (human) | β-Galactosidase beta (E. coli) | α-Mannosidase I | α-Mannosidase II | |

| Side chain Donor (ChDon) | Asp92, Asp93, Asp170, Glu203, Asp231 | Tyr83, Glu129, Asn187, Glu188, Glu268, Tyr306, Tyr333 | Asn102, Asp201, His391, Glu461, Glu537, His540, Asn604 | Asp463, Glu599, Glu663, Glu689 | His90, Asp92, Asp204, Tyr269, Asp340, Asp341, His471, Asp472, Tyr727 |

| Side chain Acceptor (ChAcc) | Lys168, Arg227 | Tyr83, Asn187, Tyr306, Tyr333 | Asn102, His391, Asn460, His540, Trp568 | Arg334, Arg597, Thr688, | Arg228, Tyr269, Asp341, His471, Asp472, Tyr727 |

| Ionic | Asp170 | Glu129 | – | Ca | His90, Asp204, Asp341 |

| Backbone donor (BkDon) | – | Ile126 | – | Thr688 | Arg876 |

| Backbone Acceptor (BkAcc) | – | Ala128 | – | – | – |

The PLIF analysis for α-mannosidase I complex was performed with three PDB structures. The calcium ions present in the enzyme provided ionic type of interactions with the O− ions present in the molecules. Further, the acidic residues such as Asp463, Glu599, Glu663 and Glu689 have shown side chain donor interactions and other residues such as Arg334, Arg597 and Thr688 have shown side chain acceptor interaction with the acceptor and donor functional groups in the molecules. It is noted that the Thr688 exhibited backbone donor interaction. α-Mannosidase II has 41 complexes, which were used for the PLIF analysis. The type of interaction of the enzyme with the molecules is different from α-mannosidase I. The acidic residue Asp341 has side chain donor, acceptor and ionic interactions with the molecules. However, Tyr269, His471, Asp472 and Tyr727 residues are having side chain donor and acceptor interactions. Only Arg876 has backbone donor interaction with the molecule. This PLIF analysis showed that the acidic residues such as aspartic acid and glutamic acids are having side chain donor, acceptor and ionic interactions. Aromatic amino acids have some surface interactions or hydrophobic interactions with the aromatic rings or hydrophobic groups in the molecules. Generally, it reveals that the active site of those entire enzymes is polar, which caused these side chain donor and acceptor interactions.

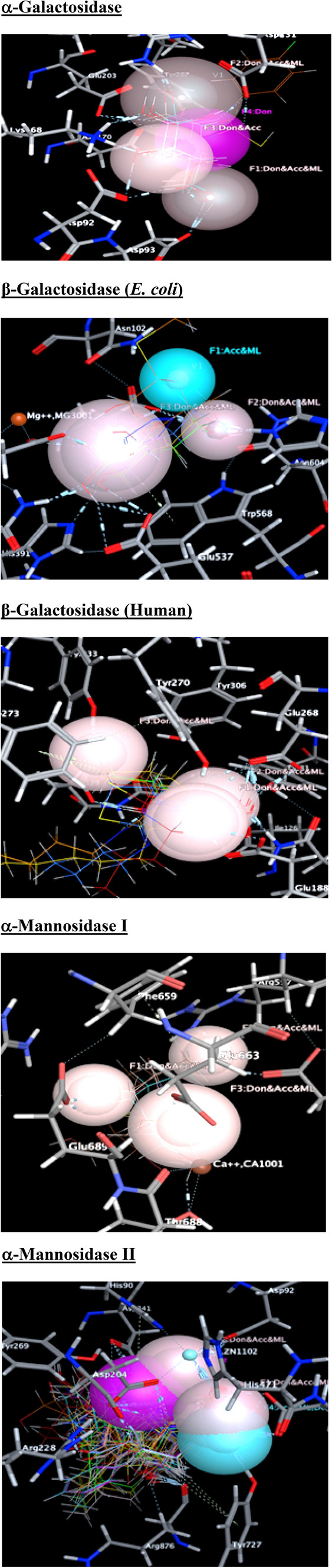

Structure based pharmacophore analysis

Pharmacophore based virtual screening of NPs were performed against different glycosidase enzymes such as α-galactosidase, β-galactosidase (human and E. coli), α-mannosidase-I and α-mannosidase-II. The pharmacophore contours generated through the PLIF analysis were used for the virtual screening analysis. The pharmacophoric feature points (contours) identified/generated on the basis of the residues interacted with the molecules. Those groups and residues exhibited sufficient interactions were grouped to create pharmacophore feature points. The important pharmacophore contours (query points) generated through the PLIF analysis are provided in Table 4 and are graphically represented in Fig. 8. The developed pharmacophore contours show that the donor and acceptor groups in the molecules and the residues make tight interactions and cause the bioactive centre for the molecules. The radius of the contours is between 1.5 and 2.5 Å and the excluded volume of the contours is between 1 and 1.5 Å. These contour features (radius of the query point and excluded volume) were used to virtual screening a data set comprised of 165 natural products. Initially, the pharmacophore contour radius was set as 3 Å to virtual screen the data set and the query structures have yielded more number of compounds as HITs. In order to prune the data set and to obtain significant HITs, the radius of the query points were adjusted. The HITs identified through all these queries are provided in Table 5.

Table 4.

Results derived from pharmacophore based virtual screening

| Compound code | RMSD values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Galactosidase | β-Galactosidase (E. coli) | β-Galactosidase (Human) | α-Mannosidase-I | α-Mannosidase-II | |

| NP-27 | 1.4336 | ||||

| NP-51 | 1.2925 | 1.6728 | 1.3255 | ||

| NP-59 | 1.2039 | ||||

| NP-60 | 1.5691 | 1.6709 | |||

| NP-61 | 1.7214 | 1.3325 | 1.4271 | 1.5927 | |

| NP-76 | 1.6872 | ||||

| NP-77 | 1.6858 | ||||

| NP-81 | 1.7509 | 1.1568 | 1.5032 | ||

| NP-82 | 1.6952 | ||||

| NP-99 | 1.3677 | ||||

| NP-133 | 1.8534 | ||||

| NP-165 | 1.9865 | 1.6565 | 1.9765 | 1.8965 | |

Fig. 8.

Structure based pharmacophore contours used for the virtual screening (Hydrogen bond donor (Don)/acceptor (Acc)/metal ligand (ML) interactions are indicated as light brown, donor (Don) is given as pink colour, hydrogen bond acceptor (Acc) is provided as blue colour)

Table 5.

Structure of the compounds identified as significant HITs through docking and pharmacophore hypothesis

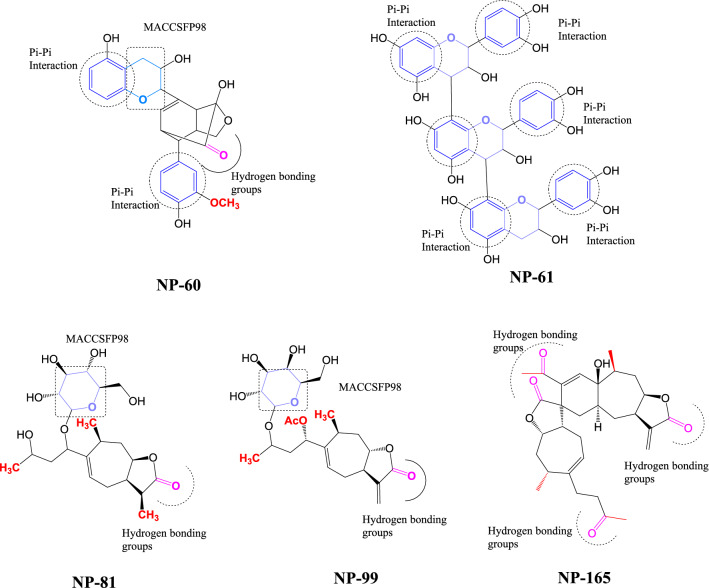

The pharmacophore based virtual screening results revealed that the compound NP-165 has been identified as remarkable HIT against all the targets studied (except E. coli β-galactosidase). The compound NP-61 has also been identified as a significant HIT against all the targets except β-galactosidase (human). Further, the compounds such as NP-51 (β-galactosidase (both species) and α-mannosidase I), NP-81 (α-galactosidase, α-mannosidase I and II) and NP-60 (β-galactosidase (E. coli) and α-mannosidase II) have been identified as HIT for multiple targets through this virtual screening study.

The results derived from the virtual screening studies (both docking and pharmacophores methods) showed that the compounds such as NP-51, NP-81 and NP-165 possessed significant interactions on the studied targets and the compounds NP-51 and NP-165 are considered as the best HIT among the studied compounds, which has been selected against all the targets in both methods. The compound NP-61 has been selected as better HIT in pharmacophore based studies but it does not consider as HIT in docking studies. However, compound NP-60 has been considered as good compound for α-mannosidase I and II inhibitory activity by docking studies, while the pharmacophore analysis provided that it is a better inhibitor for only α-mannosidase II enzyme. These results showed that the compound NP-165 is the utmost best inhibitor for the studied targets (except β-galactosidase in E. coli) and the compounds NP-51 and NP-81 are significant inhibitors for α-mannosidase I enzyme. Among the mannosidase II inhibitory activities, the compounds NP-165, NP-81 and NP-60 are selected through both virtual screening methods.

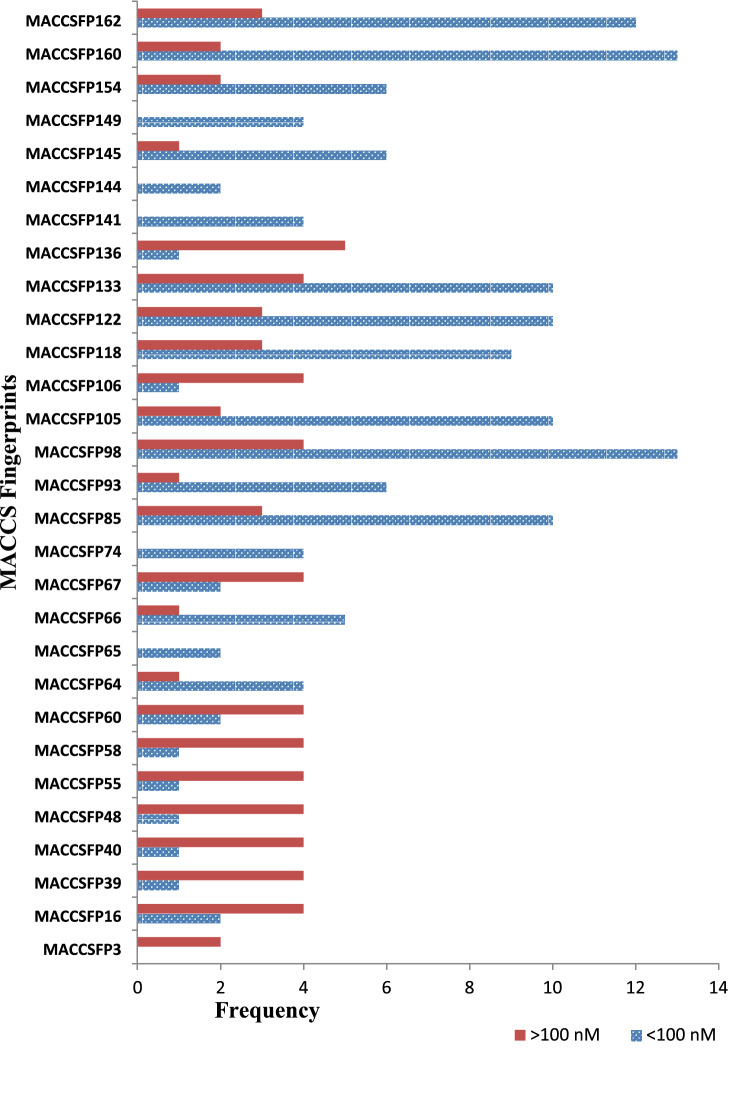

MACCS fingerprint analysis

MACCS fingerprints were calculated using the PaDEL software, which provided the type of structural features/groups present in the molecules. These fingerprints are used to identify the fragments which are responsible for favourable or unfavourable activities of a set of molecules. In this study, we have used 41 α-mannosidase II inhibitor-protein complexes obtained from protein data bank. In order to identify the presence of fragment/groups in high active or low active molecules, a threshold activity value of IC50 above 100 nM (> 100 nM) and below 100 nM (< 100 nM) are provided in Table 6. The fingerprints showed that the sulphur atom connected to other heteroatom especially oxygen atom through single or double bond is present in low active compounds. However, the presence of sulphur atom in the rings, nitrogen atoms, methyl groups, aromatic rings and aliphatic rings have favourable effect for the inhibitory activity. Additionally, the presence of halogen atoms in the molecules reduce the α-mannosidase II inhibitory activity.

Table 6.

Important fingerprints present in compounds with IC50 values > 100 nM and < 100 nM

| FP | All | < 100 nM | > 100 nM | Fingerprint description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACCSFP3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | Ge, As, Se, Sn, Sb, Te, Pb, Bi, Po |

| MACCSFP16 | 6 | 2 | 4 | Heteroatom + any 2 atoms + linkage to first atom |

| MACCSFP39 | 5 | 1 | 4 | OS (O) O |

| MACCSFP40 | 5 | 1 | 4 | S–O |

| MACCSFP48 | 5 | 1 | 4 | O + Heteroatoam (O) + O |

| MACCSFP55 | 5 | 1 | 4 | OSO |

| MACCSFP58 | 5 | 1 | 4 | Heteroatom + S + Heteroatom |

| MACCSFP60 | 6 | 2 | 4 | S = O |

| MACCSFP64 | 5 | 4 | 1 | Any atom + ring bond + any atom + non ring bond + S |

| MACCSFP65 | 2 | 2 | 0 | C aromatic bond N |

| MACCSFP66 | 6 | 5 | 1 | C + C + (C) + (C) + Any atom |

| MACCSFP67 | 6 | 2 | 4 | Hetero atom + S |

| MACCSFP74 | 4 | 4 | 0 | CH3 any atom CH3 |

| MACCSFP85 | 13 | 10 | 3 | CN (C)C |

| MACCSFP93 | 7 | 6 | 1 | Heteroatoms + CH3 |

| MACCSFP98 | 17 | 13 | 4 | Hetero atom + any 5 atoms + linkage to first atom |

| MACCSFP105 | 12 | 10 | 2 | Any atom + ring bond + any atom (ring bond + any atom) + ring bond + any atom |

| MACCSFP106 | 5 | 1 | 4 | Halogen + any atom (any atom) + any atom |

| MACCSFP118 | 12 | 9 | 3 | Any atom + CH2CH2 + any atom > 1 |

| MACCSFP122 | 13 | 10 | 3 | Any atom + N + (Any atom) + any atom |

| MACCSFP133 | 14 | 10 | 4 | Any atom + ring bond + any atom + non ring bond + N |

| MACCSFP136 | 6 | 1 | 5 | O = Any atom is > 1 |

| MACCSFP141 | 4 | 4 | 0 | CH3 > 2 |

| MACCSFP144 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 6M ring |

| MACCSFP145 | 7 | 6 | 1 | O > 2 |

| MACCSFP149 | 4 | 4 | 0 | CH3 > 1 |

| MACCSFP154 | 8 | 6 | 2 | C = O |

| MACCSFP160 | 15 | 13 | 2 | CH3 |

| MACCSFP162 | 15 | 12 | 3 | Aromatic |

The MACCS fingerprints explained the kind of fragments/groups present in the inhibitors and which have been compared with the HITs selected through structure based approaches. The kind of fragments in the HITs responsible for the α-mannosidase inhibitory activity as per the MACCS fingerprints is graphically represented in Figs. 9 and 10.

Fig. 9.

Graphical representation of MACCS fingerprints of α-Mannosidase-II inhibitors

Fig. 10.

Important structural features of selected HITs for α-Mannosidase-II inhibitory activity using MACCS fingerprints

In silico ADMET studies

In silico ADMET properties of the identified compounds were calculated using SwissADME and Pallas softwares and are provided in Table 7. It shows that the compound NP-165 has optimum lipophilicity (logP) and solubility values which revealed that the compound NP-165 may penetrate the biological membrane significantly and reach the site of action. None of the identified compounds have permeability in blood brain barrier and are substrate for CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6 (except NP-60) and CYP3A4 (except NP-165), showed that these compounds possessed limited metabolism with these metabolic enzymes. Except NP-81, all other molecules are substrate for P-glycoprotein, which reveals that these compounds may have multidrug resistance problems. Those compounds have very high and low logS values exhibited low GI absorption and are having lower Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) values. The hERG blocking activity predicted through Pallas software showed that all these identified compounds have less hERG blocking activity.

Table 7.

In silico ADMET properties of the identified compounds

| Comp. no. | GI absorption | TPSA | Log P | Log S | BBB permeant | Pgp substrate | CYP1A2 inhibitor | CYP2C19 inhibitor | CYP2C9 inhibitor | CYP2D6 inhibitor | CYP3A4 inhibitor | log Kp (cm/s) | Bioavailability Score | HERG (pIC50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP-60 | High | 125.68 | 1.61 | − 3.32 | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | − 8.29 | 0.55 | 2.2 |

| NP-61 | Low | 331.14 | 1.77 | − 9.94 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | − 9.24 | 0.17 | 2 |

| NP-81 | Low | 145.91 | 0.18 | − 2.38 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | − 9.09 | 0.55 | 2.1 |

| NP-99 | Low | 151.98 | 0.66 | − 2.98 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | − 9.01 | 0.55 | 1.8 |

| NP-165 | High | 106.97 | 3.41 | − 4.45 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | − 7.6 | 0.55 | 2.3 |

Biological evaluations

The in vitro biological activity of the identified compounds were evaluated and the Table 8 showed that the compound, NP-165 has significant activity against both α-mannosidase (0.5 µM) and β-galactosidase (0.2 µM) enzymes. The compound NP-51 has significant docking score, but has moderate activity against both enzymes. The compounds NP-60 also has considerable activity against both enzyme and NP-99 (2.3 µM) has considerable activity against α-mannosidase than the other tested compounds.

Table 8.

Enzyme inhibitory activity of the identified compounds

| Compound no. | Activity IC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|

| β-Galactosidase | α-Mannosidase | |

| NP-60 | 2.0 | 1.3 |

| NP-61 | 4.2 | 3.0 |

| NP-81 | 5.7 | 4.2 |

| NP-99 | 4.8 | 2.3 |

| NP-165 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Swainonine | – | 0.05 |

| Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride | 0.08 | – |

Conclusion

The present works showed that the virtual screening and the fingerprint analyses are used to identify lead compounds for further optimization of novel inhibitors. The PLIF and MACCS analysis were performed with the respective enzyme inhibitors and its experimental activities reported in the literature. The results have given sufficient informations for the design of novel molecules on the target. These natural product compounds have many biological activities and was reported in literatures, hence the designing of novel compounds with this lead compounds may have significant poly pharmacological activities. The virtual screening analysis by docking and pharmacophore analysis yielded xantholide (pungiolide C) (Nour et al. 2009), a significant compound which also showed inhibitory activities against β-galactosidases and α-mannosidases enzymes. Earlier research works showed that it possessed various activities especially in carbohydrate mediated diseases. However, inhibition of the activities of these studied enzymes by the HITs can inhibit the production of glycoprotein, glycolipid and liposaccharides biosynthesis. This reveals that these compounds can be used for the treatment of antiviral (including HIV), cancer, diabetics, etc. by inhibiting various glycosidase enzymes (glucosidase, galactosidase and mannosidases).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the European Union (FEDER funds POCI/01/0145/FEDER/007728) and National Funds (FCT/MEC, Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia and Ministério da Educação e Ciência) under the Partnership Agreement PT2020—UID/MULTI/04378/2013; and NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000024, supported by Norte Portugal Regional Operational Programme (NORTE 2020), under the PORTUGAL 2020 Partnership Agreement, through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). Natércia F. Brás and N.S.H.N. Moorthy would like to thank the FCT for their IF grant (IF/01355/2014) and Postdoc grant (SFRH/BPD/2008/44469), respectively. "Natércia F. Brás would like to thank the FCT for her CEEC grant (CEECIND/02017/2018)."

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Disclosure

No human participants or animals involved in this research work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

N. S. Hari Narayana Moorthy and Natércia F. Brás equally contributed the same.

References

- Bayly CI, Cieplak P, Cornell WD, Kollman PA. A well- behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges: the RESP model. J Phys Chem. 1993;97:10269–10280. doi: 10.1021/j100142a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bras NF, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ. QM/MM studies on the beta-galactosidase catalytic mechanism: hydrolysis and transglycosylation reactions. J Chem Theory Comput. 2010;6:421–433. doi: 10.1021/ct900530f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brás NF, Cerqueira NM, Ramos MJ, Fernandes PA. Glycosidase inhibitors: a patent review (2008–2013) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2014;24:857–874. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2014.916280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. The role of natural product chemistry in drug discovery. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:2141–2153. doi: 10.1021/np040106y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MS. Natural products to drugs: natural product derived compounds in clinical trials. Nat Prod Rep. 2005;22:162–195. doi: 10.1039/b402985m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramelo JJ, Parodi AJ. Getting in and out from calnexin/calreticulin cycle. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10221–10225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700048200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case DA, Cheatham TE, III, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Zhang RCW, Merz KM, Roberts B, Hayik S, Roitberg A, Seabra G, Swails J, Kolossváry AWGI, Wong KF, Paesani F, Vanicek J, Wolf RM, Liu J, Wu X, Steinbrecher SRBT, Gohlke H, Cai Q, Ye X, Wang J, Hsieh MJ, Cui G, Mathews DH, Seetin MG, Salomon-Ferrer R, Sagui C, Babin V, Luchko T, Kovalenko SGA, Kollman PA. Amber 12. San Francisco: University of California; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ceron-Carrasco JP, Cerezo J, Requena A, Zuniga J, Contreras-Garcıa J, Chavan S, Manrubia-Cobo M, Perez-Sanchez H. Labelling herceptin with a novel oxaliplatin derivative: a computational approach towards the selective drug delivery. Mol Model. 2014;20:2401–2407. doi: 10.1007/s00894-014-2401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira NMFSA, Ribeiro J, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ. vsLab—an implementation for virtual high-throughput screening using AutoDock and VMD. Int J Quant Chem. 2011;111:1208–1212. doi: 10.1002/qua.22738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A, Zoete V. A BOILED-Egg to predict gastrointestinal absorption and brain penetration of small molecules. ChemMedChem. 2016;11(11):1117–1121. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201600182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42717. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas JH, Brian MW, Reuben HE. LacZ β-galactosidase: Structure and function of an enzyme of historical and molecular biological importance. Protein Sci. 2012;21:1792–1807. doi: 10.1002/pro.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essmann U, Perera L, Berkowitz ML, Darden T, Lee H, Pedersen LG. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J Chem Phy. 1995;103:8577–8593. doi: 10.1063/1.470117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery Jr JA, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam MJ, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ, (2009) Gaussian 09, Revision B. 01, Gaussian Inc., Wallingford

- Garman SC, Garboczi DN. The molecular defect leading to Fabry disease: structure of human α-galactosidase. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:319–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholamhoseinian A, Fallah H, Sharifi-Far F, Mirtajaddini M. Alpha mannosidase inhibitory effect of some Iranian plant extracts. Int J Pharmacol. 2008;4:460–465. doi: 10.3923/ijp.2008.460.465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guce AI, Clark NE, Salgado EN, Ivanen DR, Kulminskaya AA, Brumer H, 3rd, Garman SC. Catalytic mechanism of human alpha-galactosidase. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3625–3632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.060145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guven RG, Kaplan A, Guven K, Matpan F, Dogru M. Effects of various inhibitors on β-galactosidase purified from the Thermoacidophilic Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius Subsp. Rittmannii isolated from Antarctica. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2011;16:114–119. doi: 10.1007/s12257-010-0070-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helenius A, Aebi M. Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:1019–1049. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, Simmerling C. Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins. 2006;65:712–725. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:27–28. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain Q. Beta galactosidases and their potential applications: a review. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2010;30:41–62. doi: 10.3109/07388550903330497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ieyama T, Gunawan-Puteri MDPT, Kawabata J. α-Glucosidase inhibitors from the bulb of Eleutherine Americana. Food Chem. 2011;128:308–311. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbernon B, Cecilia JM, Perez-Sanchez H, Gimenez D. METADOCK: a parallel metaheuristic schema for virtual screening methods. Int J High Perform Comput Appl. 2017;32(6):789–803. doi: 10.1177/1094342017697471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Izaguirre JA, Catarello DP, Wozniak JM, Skeel RD. Langevin stabilization of molecular dynamics. J Chem Phys. 2001;114:2090–2098. doi: 10.1063/1.1332996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawatkar SP, Kuntz DA, Woods RJ, Rose DR, Boons GJ. Structural basis of the inhibition of Golgi α-mannosidase II by mannostatin A and the role of the thiomethyl moiety in ligand-protein interactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8310–8319. doi: 10.1021/ja061216p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz DA, Zhong W, Guo J, Rose DR, Boons GJ. The molecular basis of inhibition of Golgi alpha-mannosidase II by mannostatin A. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:268–277. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz DA, Nakayama S, Shea K, Hori H, Uto Y, Nagasawa H, Rose DR. Structural investigation of the binding of 5-substituted swainsonine analogues to golgi α-mannosidase II. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:673–680. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wen S, Kota BP, Peng G, Li GQ, Yamahara J, Roufogalis BD. Punica granatum flower extract, a potent alpha-glucosidase inhibitor, improves postprandial hyperglycemia in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;99:239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QP, Sulzenbacher G, Yuan H, Bennett EP, Pietz G, Saunders K, Spence J, Nudelman E, Levery SB, White T, Neveu JM, Lane WS, Bourne Y, Olsson ML, Henrissat B, Clausen H. Bacterial glycosidases for the production of universal red blood cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:454–464. doi: 10.1038/nbt1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loving K, Salam NK, Sherman W. Energetic analysis of fragment docking and application to structure-based pharmacophore hypothesis generation. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2009;23:541–554. doi: 10.1007/s10822-009-9268-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Ballesta MC, Pérez-Sánchez H, Moreno DA, Carvajal M. Plant plasma membrane aquaporins in natural vesicles as potential stabilizers and carriers of glucosinolates. Colloids Surf, B. 2016;143:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOE (2011) Chemical Computing Group Inc. Montreal, H3A 2R7, Canada (2011)

- Moorthy NSHN, Bras NF, Ramos MJ, Fernandes PA. Virtual screening and QSAR study of some pyrrolidine derivatives as α-mannosidase inhibitors for binding feature analysis. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:6945–6959. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy NSHN, Ramos MJ, Fernandes PA. Studies on α-glucosidase inhibitors development: magic molecules for the treatment of carbohydrate mediated diseases. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2012;12:713–720. doi: 10.2174/138955712801264837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy NSHN, Bras NF, Ramos MJ, Fernandes PA. Binding mode prediction and identification of new lead compounds from natural products as renin and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. RSC Adv. 2014;4:19550–19568. doi: 10.1039/C4RA00856A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy NSHN, Cerquira NMFSA, Ramos MJ, Fernandes PA. Ligand based analysis on HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Chemom Intell Lab Sys. 2015;140:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.chemolab.2014.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19981115)19:14<1639::AID-JCC10>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Fernández J, Pérez-Sánchez H, Martínez-Martínez I, Meliciani I, Guerrero JA, Vicente V, Corral J, Wenzel W. In silico discovery of a compound with nanomolar affinity to antithrombin causing partial activation and increased heparin affinity. J Med Chem. 2012;55:6403–6412. doi: 10.1021/jm300621j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nour AMM, Khalid SA, Kaiser M, Brun R, Abdallah WE, Schmidt TJ. The antiprotozoal activity of sixteen asteraceae species native to Sudan and bioactivity-guided isolation of xanthanolides from Xanthium brasilicum. Planta Med. 2009;75:1363–1368. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson ML, Clausen H. Modifying the red cell surface: towards an ABO-universal blood supply. Br J Haematol. 2008;140:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewska E, Borzym-Kluczyk M, Rzewnicki I, Wojtowicz J, Rogowski M, Pietruski JK, Czajkowska A, Sieskiewicz A. Possible role of α-mannosidase and β-galactosidase in larynx cancer. Contemp Oncol (pozn) 2012;16:154–158. doi: 10.5114/wo.2012.28795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallas 3.1.1.2 (2000) ADME-Tox software, CompuDrug International Inc., USA

- Park H, Hwang KY, Kim YH, Oh KH, Lee JY, Kim K. Discovery and biological evaluation of novel alpha-glucosidase inhibitors with in vivo antidiabetic effect. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:3711–3715. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Sanchez H, Rezaei V, Mezhuyev V, Man D, Pena-Garcia J, den-Haan H, Gesing S. Developing science gateways for drug discovery in a grid environment. Springerplus. 2016;5:1300. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2914-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawling AJ, Lomas H, Adam WP, Marvin JRL, Dominic SA, Shane JSR, Sarah FJ, George WJF, Raymond AD, John HJ, Terry DB. Synthesis and biological characterisation of novel N-alkyl-deoxynojirimycin alpha-glucosidase inhibitors. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:1101–1105. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. Numerical- integration of Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints—molecular-dynamics of n-alkanes. J Comput Phy. 1977;23:327–341. doi: 10.1016/0021-9991(77)90098-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Linares I, Pérez-Sánchez H, Cecilia JM, García JM. High-throughput parallel blind virtual screening using BINDSURF. BMC Bioinform. 2012;13(Suppl 14):S13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-S14-S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MPA, Verhoeven S, de Graaf C, Roumen L, Vroling B, Nabuurs SB, de Vlieg J, Klomp JPG. Snooker: a structure-based pharmacophore generation tool applied to class a GPCRs. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:2277–2292. doi: 10.1021/ci200088d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivapriya K, Hariharaputran S, Suhas VL, Chandra N, Chandrasekaran S. Erythrocarpines A–E, new cytotoxic limonoids from Chisocheton erythrocarpus. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:5659–6002. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wolf RM, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA, Case DA. Development and testing of a general AMBER force field. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap CW. PaDEL-descriptor: an open source software to calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints. J Comput Chem. 2011;32:1466–1474. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.