Abstract

Objective

The increased reliance on digital technologies to deliver healthcare as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic has meant pre-existing disparities in digital access and utilisation of healthcare might be exacerbated in disadvantaged patient populations. The aim of this rapid review was to identify how this ‘digital divide’ was manifest during the first wave of the pandemic and highlight any areas which might be usefully addressed for the remainder of the pandemic and beyond.

Design

Rapid review and narrative synthesis.

Data sources

The major medical databases including PubMed and Embase and Google Scholar were searched alongside a hand search of bibliographies.

Eligibility criteria

Original research papers available in English which described studies conducted during wave 1 of the COVID pandemic and reported between 1 March 2020 and 31 July 2021.

Results

The search was described using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses and identified nine studies. The results are presented within a refined framework describing the three key domains of the digital divide: (1) digital access, within which one study described continuing issues with internet connectivity among vulnerable patients in the UK; (2) digital literacy, where seven studies described how ethnic minorities and the elderly were less likely to use digital technologies in accessing care; (3) digital assimilation, where one study described how video technologies can reduce feelings of isolation and another how elderly black males were the most likely group to share information about COVID-19 on social media platforms.

Conclusions

During the early phase of the pandemic in the developed world, familiar difficulties in utilisation of digital healthcare among the elderly and ethnic minorities continued to be observed. This is a further reminder that the digital divide is a persistent challenge that needs to be urgently addressed when considering the likelihood that in many instances these digital technologies are likely to remain at the centre of healthcare delivery.

Keywords: COVID-19, organisation of health services, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This rapid review provides timely information on the impact of COVID-19 on the digital divide during the first wave of the pandemic.

The findings were presented within a framework developed to provide a more comprehensive context for this and future explorations of the digital divide.

The search covered three key databases and was augmented by manual searches though the quality of the papers identified was not formally assessed.

Introduction

A growing range of digital tools have been developed to help patients track their condition, connect with peer and clinical support, enable self-management and aid more appropriate utilisation of health services.1 2 When coordinated with the appropriate digital infrastructure they appear well placed to meet the need for more effective personalised healthcare,3 which is capable of bridging the gap between increasing demand and restricted resource.4 The WHO’s recently launched global strategy for digital health confirmed the expected role of digital technologies in creating a more equitable future for healthcare by offering ‘effective clinical and public health solutions to accelerate the achievement of the health and well-being… leaving none behind, [whether] children or adults, rural or urban’.5

Implicit within the digital transformation of healthcare and its role in reducing inequalities is that the relevant technologies are available across all levels of society.6 7 However, persistent discrepancies exist across geographies and between communities in how they access and use digital technologies, differences compounded by the growing sophistication in the functionality of devices and connectivity.8–10 The result is that comparative advantages continue to be afforded to those groups that can maximise the capabilities of digital technologies.11 12 These societal differences in access and adoption are commonly referred to as the ‘digital divide’,12 a catch-all phrase which implies a simple dichotomy but in reality describes a complex range of users whose level of adoption changes over time influenced by infrastructure, socioeconomic environment and individual characteristics such as educational background and physical disability.13–17

Despite the acknowledged inequities in digital access and utilisation, measures introduced to reduce infection rates following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020 led to an acceleration of the reliance on digital health technologies both in Europe and the USA.6 18–20 Because the spread of COVID-19 was so rapid many of these digital interventions were introduced without the recommended periods of consultation and evaluation.21 22 This rapid introduction led to concerns that the new digitally reliant models of healthcare delivery will disproportionately affect the health of disadvantaged communities23–26 such as ethnic minorities,27 rural populations,28 the elderly29 and residents of care homes.30 These concerns were heightened when it became apparent that the same groups on the ‘wrong’ side of the digital divide were the most likely to experience severe symptoms and higher levels of mortality as a result of contracting the virus.23–26

Many of these novel digitally reliant processes that in March 2020 were considered a short-term fix are now becoming embedded in existing systems of care in the UK and elsewhere.19 31 Therefore, it is important to understand the implications of these new systems for patients and the quality and safety of the care they receive. This rapid review aims to explore how the digital divide manifested during the first wave of COVID-19-generating knowledge that can improve digital inclusion for the remainder of the pandemic and beyond.

Methods

Study design

Rapid reviews have previously been recommended by the WHO among others for their ability to provide timely and credible evidence for policymakers and practitioners in what is a dynamic and evolving public health crisis.32 33 We have used many of the principles of a systematic review process; our search terms were clearly defined using Boolean principles and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) described the search.34 The inclusion and exclusion criteria were also clearly defined and two reviewers agreed on the selection of the various papers. (The search terms can be found in online supplemental file 1.) However, the systematic review process was expedited by amending several steps, that is, drawing only on the major medical databases and forgoing a structured appraisal of the quality of selected studies in place of a transparent description of the characteristics of each within the results.

bmjopen-2021-053440supp001.pdf (70.1KB, pdf)

The results are presented within the three key domains of a framework (informed by Ai-Chi Loh and Chib’s35 work) to enable a more systematic description of the various aspects of the digital divide explored by each study (see table 1).

Table 1.

Framework for interpreting the digital divide in healthcare (after Ai-chi Loh and Chib35)

| Domain | Definition | Construct | Definition | Example |

| Digital access | The ability to access the necessary hardware, software and internet services associated with utilisation of digital technologies.114 | The types of device available. | The nature and functionality of the digital device.12 | The model of smartphone or desktop computer and any peripheral or supporting technology such as hard drives or printers. |

| The ease with which devices can be accessed. | How readily individuals can access digital devices.8 12 | Relying on the local library for access to a computer. | ||

| The autonomy and reliability of internet connectivity. | The degree of independence with which the internet can be reliably accessed.115 116 | Consistent access to the internet via a user’s home internet network. | ||

| Digital literacy | The degree of sophistication with which individuals are able to use digital technologies.117 | Digital skill set. | The confidence and ability of an individual to use a variety of digital technologies.118 | The ability to use and manage email. |

| Types of digital usage. | The ways in which digital technologies are used.119 | Using search engines to access information on current affairs. | ||

| Digital assimilation | The degree to which digital technologies are incorporated and used in everyday life.114 120 | Engagement with digital technologies. | The degree to which individuals use digital technologies to enhance social connections and values.121 | Establishing a community group on a social media platform to support elderly neighbours. |

| Social support. | Social connections that facilitate an individual’s engagement with digital technologies.118 | The availability of technical support in the use of digital technologies from a son or daughter. | ||

| Harnessing digital outcomes. | The ability to contextualise the use of digital technologies to achieve quantifiable outputs.122 123 | Using software apps to reach and maintain fitness goals. |

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, Embase and Google Scholar, alongside hand searches of bibliographies, to identify relevant manuscripts. In doing so, we used a combination of the search terms ‘COVID 19’ or ‘pandemic’ or ‘COVID’ and ‘digital health’ or ‘telemedicine’ or ‘remote access’ or ‘digital divide’ to identify studies which had explored the access or utilisation of information or communication technologies in relation to health and care since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Bibliographies within the publications we identified were searched alongside a manual search.

Inclusion criteria

To be included in our review, the manuscript must consist of original research specific to individuals using digital technologies in relation to their health or well-being since the beginning of the pandemic recognised by the WHO as March 2020 with any publication published from 1 March until 31 July 2021.36 This includes the diagnosis, monitoring or treatment of COVID-19 and any other condition or disease. The focus of our work was the provision of care within the developed world (ie, one which is predominantly industrialised and more economically developed with a higher individual income37) during the early phase of the pandemic to ensure relevance for policymakers, commissioners and providers in these areas and so we limited the papers included to those that were available in English.

Study selection

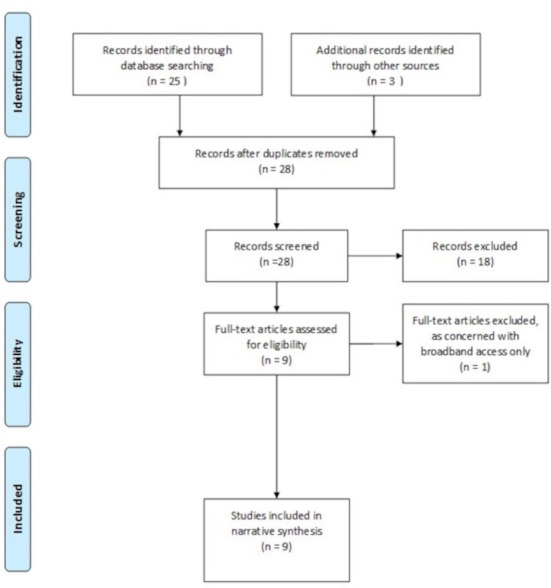

The process followed the four stages of PRISMA34: identification, screening, eligibility and final inclusion and the search data presented in the PRISMA diagram (see figure 1). This involved two reviewers (IL and SG) screening the titles, abstracts and, where appropriate, full texts against the inclusion criteria and the final selection of papers agreed by both.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram.

Analysis procedures

We developed a framework that built on the work of Ai-Chi Loh and Chib35 to reflect a more nuanced representation of the digital divide describing it within three key domains: digital access relating to the ability to access devices and internet; digital literacy describing the skill set of individuals; and digital assimilation addressing the degree to which digital technologies are incorporated into everyday life. Each domain consists of a series of related constructs and these are further defined and presented with examples of each in table 1. A descriptive summary of the characteristics of each included study was produced (see table 2) and the findings from the identified papers are analysed within each of the three domains of our refined framework.

Table 2.

Summary of study characteristics

| Authors | Study design | Country | Study population | Research question | Analytical framework | Findings |

| Campos-Castillo and Anthony44 | Cohort study | USA | 10 624 US-wide survey respondents | What are the characteristics of patients who used ICTs to connect with care providers in relation to COVID-19? | Logistic regression | Total of 17% of respondents self-reported using telehealth because of the pandemic. Black respondents were more likely than Whites to report using telehealth because of the pandemic (OR 1.42; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.88). |

| Campos-Castillo and Laestadius47 | Cohort study | USA | 10 541 US-wide survey respondents | What are the characteristics of patients posting COVID-19-related messages on social media? | Logistic regression | Respondents who identified as black (OR 1.29; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.64; p=0.03) or Latino (OR 1.66; 95% CI 1.36 to 2.04; p=0.03) had higher odds than respondents who identified as white of reporting that they posted COVID-19 content on social media. |

| Chunara et al40 | Cohort study | USA | 140 184 patients | What are the characteristics of patients who use telemedicine? | Descriptive statistics and logistic regression | Black patients nearly half as likely as white patients to access care through telemedicine (OR 0.6 times; 95% CI 0.58 to 0.63). |

| Eberly et al43 | Cohort study | USA | 2940 cardiovascular outpatients | What are the characteristics of patients who complete a telemedicine consultation? | Logistic regression | Being female and being non-English speaking were independently associated with less telemedicine use. |

| Gabbiadini et al46 | Cross-sectional | Italy | 465 respondents | Whether the use of ICT promoted perceptions of social support (mitigating the psychological effects of lockdown). | Separate multiple and simple regression models | The amount of technology use was a significant predictor of perceived social support (OR 2.40, p<0.02, 99% CI −0.01 to 0.31). |

| Hughes et al39 | Mixed methods | UK | 156 high-risk individuals and a further 1217 vulnerable patients over the age of 70 | Can medical students (general practitioner trainees) use teleconsultations to assess the needs of patients and support digital access to healthcare? | Descriptive statistical analysis. Thematic analysis of conversation issues arising, no theoretical framework named. |

A total of 22% high-risk patients and 44% of vulnerable patients reported connectivity issues. Participants reported who were confident in ordering medication online. |

| Runfola et al45 | Cohort study | Italy | 33 bariatric outpatients | What are the characteristics of patients who completed a telemedicine consultation? | Categorical data were compared using the Χ2 test. Continuous variables compared using the Student’s t-test. | 57.6%completed the consultation. No significant differences were found between participants and non-participants in terms of age and gender. |

| Weber et al41 | Cohort study | USA | 52 585 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 | What are the characteristics of patients who access care by telemedicine, ER or office visit? | Descriptive statistics and multinomial regression analysis | White patients had the highest predicted probabilities of using telehealth (46.7%). Black and Hispanic patients over 65 have the lowest predicted probability (11.3%). |

| Whaley et al42 | Cross-sectional | USA | Data from 5.6 to 6.8 million US individuals with employer health insurance between 2018 and 2020 | What are the characteristics of patients who use telemedicine? | Logistic regression | Patients living in postcodes with lower income or majority racial/ethnic minority populations had lower rates of adoption of telemedicine; ≥80% racial/ethnic minority postcode: −71.6 per 10 000 (95% CI −87.6 to −55.5); 79%–21% racial/ethnic minority postcode: −15.1 per 10 000 (95% CI −19.8 to −10.4). |

ER, emergency room; ICT, information and communication technology.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or members of the public were involved in the conceptualisation, design or undertaking of this rapid review.

Results

A total of 28 candidate articles were identified from a search of the named databases and hand searches from the bibliographies of these references. Ultimately, nine papers were selected for the analysis, the remaining papers were excluded as they were either opinion pieces that did not contain original research or despite being published after March 2020 referenced research conducted prior to the onset of the epidemic. One study looked at digital access; set in UK primary care it explored internet connectivity among vulnerable patients (including those who have received an organ transplant, are undertaking immunotherapy or an intense course of radiotherapy for lung cancer).38 39 It was also one of the seven studies that looked at digital literacy39 alongside five studies set in the USA that explored the use of digital technologies in accessing care among different ethnic groups40–44 and one study conducted in Italy that looked at the age and gender of patients using telemedicine.45 Two studies were concerned with digital assimilation, one set in Italy described the social support gained from using video messaging platforms46 and a second again set in the USA explored the characteristics of individuals posting COVID-related content on social media.47 The key characteristics of these papers are summarised in table 2.

Digital access

We identified one study concerned with the access of digital technologies, specifically the reliability of internet connectivity. It was conducted in UK primary care as part of a study whose overall aim was to explore whether vulnerable patients might be usefully supported by telecoaching in the use of digital health technologies, in this instance by general practitioner trainees.39 As part of these conversations a direct question was asked around internet connectivity and the authors reported that 22% of high-risk patients and 44% of vulnerable patients reported issues.39

Digital literacy

A total of seven studies addressed the domain of digital literacy and in particular an individual’s digital skill set, specifically in relation to the ways in which they accessed care. All provided comparisons of use between groups using descriptions of demographic characteristics that included age, gender and ethnicity.48 Two studies used routinely collected electronic health data, though were conducted independently of each other at two different sites in New York (USA).40 41 The first study used data gathered from patients at New York University Hospital collected over a 6-week period to determine whether they had received their COVID-19 diagnosis at an office visit or via video consultation. The authors described that the digital infrastructure of the service was well resourced and established and therefore attributed the reduced utilisation of telemedicine by black patients to factors unrelated to the digital capacity of the facility.40 The second study set in New York was also situated within a large healthcare centre and again compared the means of accessing healthcare between ethnic groups within the early months of the pandemic.41 They found that black and Hispanic patients were more likely to visit the emergency room (ER) or arrange an office visit than use telehealth than their white or Asian counterparts.41 In this instance, the authors recognised that the more extensive use of ER may be due to the disproportionate number of ethnic minorities that experienced severe COVID-related symptoms.41 Another study set in the USA compared the use of telemedicine among commercially insured patients from 2018 through to 2020.42 In doing so, they explored differences in both the nature of the care they received and the means of access in the first 2 months of the pandemic and described that though there was an increase in telemedicine it did not make up the shortfall in the number of visits in comparison to the usual levels of assessing preventative or elective care among ethnic minorities.42 Campos-Castillo and Anthony conducted a secondary analysis of of cross-sectional survey data from the Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel. This is a national, probability-based online panel of adults (18 or older) living in US households that they used to explore self-reported use of telemedicine. Following adjustment for socioeconomic status (SES), age and perceived level of threat to their health from the pandemic (no threat, minor or major), 44 they found black patients were actually more likely to contact care providers using information and communication technologies if they perceived their health was threatened by the virus.44

Two studies specifically explored whether there were differences in the characteristics of patients fulfilling prearranged or routine video consultations during the pandemic. One of these studies was also set in the USA and compared the characteristics of cardiovascular patients who ‘attended’ teleconsultations and found no differences in cancellation rates based on race, ethnicity or household income. However, differences between genders were observed with those completing telemedicine tending to be male and older.43 In Italy, Runfola et al explored the utilisation and subsequent satisfaction with video consultations among a group of bariatric patients. They found no significant differences in terms of age or gender between those who succeeded or failed to complete a video call.45 However, in terms of overall numbers just under 58% of patients fulfilled the video consultation and the authors felt that this was due to the absence of basic computer skills and a lack of self-efficacy in using video call systems.45 In relation to self-efficacy, the Hughes et al’s study set in the UK also assessed vulnerable patients’ confidence and ability to order medications online and reported they were comfortable and confident with the process.39

Digital assimilation

Two studies explored the use of digital technologies in relation to maintaining or interacting with a social network. One study set in Italy described how feelings of loneliness, boredom and irritability were all reduced as a result of regular utilisation of video calls, and the positive effects on maintaining meaningful relationships and mental health.46 Meanwhile, in the USA, another secondary analysis of the same cross-sectional survey data from the Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel was conducted to understand if there were differences in the characteristics of individuals who posted COVID-19-related content to social media platforms.47 The authors discovered that proportionally members of racial and ethnic minority groups and among these older black males were the most likely to contribute COVID-19-related content.47

Discussion

General findings

Our rapid review identified how pre-existing societal disparities in access to and utilisation of health-related digital technologies were accentuated by COVID-19. We identified nine studies that explored various constructs within the three domains of our digital divide framework. In relation to digital access, poor internet access among the elderly was reported39; as regards digital literacy lower levels of take-up of telemedicine among certain communities in the USA were described particularly among black and Hispanic patients.41–44 Within the domain of digital assimilation one study described how face-time technology can sustain relationships among dislocated peer groups,45 and another how black and elderly males, previously considered a group unprepared to share health information on social media platforms, were the demographic most likely to post content on the pandemic, an important consideration in understanding the emerging scepticism of the COVID-19 vaccine in ethnic groups.46

Strengths and weaknesses

Our search strategy was designed to capture the experiences and broader lessons that might be learnt by exploring the initial stages of the pandemic, including those of countries that had health services of sufficient maturity to initiate agile and integrated responses. We focused on the early phase of the pandemic in order to understand the impact of the rapid changes to service delivery on those most vulnerable to the digital divide with the intention of producing timely findings that might inform service delivery in subsequent phases. That our search uncovered so few studies can be attributed to two factors relating to the pandemic; first that the research capacity of healthcare organisations would have been compromised by dealing with the exceptional demand on their services49 50; second that the issue of the ‘digital divide’ which had previously failed to be considered a priority was unlikely to be addressed during the most serious public health crisis in a generation.51

Although our search initially uncovered numerous titles many were opinion or editorial pieces, demonstrating how widely recognised the phenomenon of the digital divide is but also its lack of priority as a subject for original research.24 28 52–54 The studies identified were conducted within only three countries at the time of the first wave they constituted three of the top four worst death rates from COVID-19 per capita.55 56

Our rapid review discovered only a small number of heterogeneous papers of limited geographic scope which precluded data synthesis and may have introduced a degree of bias. The lack of a theoretical underpinning in many of the papers limited generalisability56 and that two of the studies relied on self-reported data39 44 raised familiar issues regards their reliability.57 However, previous comparisons between systematic and rapid reviews have failed to find significant differences in the outcomes they report58 59 and all of our included studies offered valuable insight into how the digital divide was magnified by the changes to health delivery in the early stages of the pandemic.

Specific findings

Digital access

The Hughes et al’s paper provides the latest example of how discrepancies in reliable internet connectivity continue in England39 60 findings which were corroborated by the most recent surveys of digital access conducted in the UK which found that nearly 7% of homes in England and Wales did not have a reliable internet connection,61 62 a lack of connectivity that disproportionately affected the elderly, those of lower SES and the disabled.61–64

Despite the calls to harness digital technologies on a global scale,5 65–67 these also need to address the stubborn differences in digital access that remain within the developed world where significant divisions in digital connectivity and utility remain and continue to affect the most vulnerable members of society.8 65 68–75 The pandemic prompted broader acknowledgement of these differences in several health economies where a number of initiatives were introduced.54 76 For example, in the UK broadband providers lowered the prices and reduced data caps for the vulnerable,77 and in the USA roving buses were used to provide Wi-Fi access for unconnected communities.78

Digital literacy

The patterns in digital literacy relating to SES, age or race described in four of the studies we identified40 41 43 44 have been observed for nearly three decades.8 18–20 63 64 79–81 However, prior to the pandemic, using traditional methods of in-person access did not hold the same degree of risk as during a pandemic where airborne transmission led to widespread recommendations to minimise social contact.36 This may be due in part to variations in individual perception of risk influenced by personal experience, social values and the attitudes of friends and family.82 It also reflects the resistance of the digital divide to intervention. A number of previous attempts have been made to connect less technologically enabled patients to the appropriate care.53 83 84 However, the non-adoption and abandonment of telehealth technologies by the intended users is common,85–88 complicated by the influences of the provider organisation and the design and compatibility of the intervention.89 Self-efficacy, patient activation and motivation are also critical yet underexplored components of the uptake of digital technology90 as are the impact of patients’ knowledge of their condition; the expectations of the care they should receive, their social situation and the resources at their disposal.91

In attempting to unpick this complexity a number of theoretical frameworks have been developed, intended to support adoption and produce transferable learning for a range of digital innovations.92 There have also been calls for greater patient and public involvement in designing and developing digital healthcare to ensure the needs and preferences of the full range of patients are incorporated.93 94

Digital assimilation

For over a decade the internet has been recognised as a key source of health information for the public and patients, yet the precise role of social media in the communication of health-related information is less clear.95 Although limited, evidence tended to suggest that sharing health information online was favoured by the young96 and was less so among the elderly or those of lower SES.97 However, one study we found described how older black males were more likely to share information about COVID-19 through social media channels than other demographic groups.47 This may in part be due to the growing reluctance among black and ethnic minority groups to trust information provided by healthcare professionals or the mainstream media.98–100 That highlights how the growing consumption of health information through a largely unregulated network of social media platforms can have serious repercussions for public health.100–104 This is of particular concern when placed in the context of the growing scepticism about the COVID-19 vaccine in minority communities.105 106

Despite the potential for spreading misinformation, the work by Runfola et al observed benefits for mental health from the use of face-to-face digital contact during the pandemic45 and related work found benefits from the introduction of an online blog tailored for psychiatric patients.107 The last 5 years have seen a growing realisation that the responsible use of social media can be an effective means of alleviating depression and social isolation and improve mental well-being.108–110 In particular, the utilisation of face-time technologies has been shown to increase and enhance social interactions111 and engagement.112 During the pandemic, these benefits were recognised by the UK government in their scheme that provided free tablets to care homes to help connect isolating residents with their families and loved ones.113

Conclusions

The rapid incorporation of digital technologies into mainstream healthcare delivery due to the COVID-19 pandemic was widely understood and accepted by patients in the developed world unwilling to breach social distancing advice. However, not all patient groups were either willing or able to use the digital services made available nor maximise the reported benefits of face-time technology to alleviate the effects of isolation. Our findings provide further evidence that patient engagement with any model of digital healthcare is vulnerable to complex sociopolitical factors. If more are to reap the potential benefits of digital healthcare then improvements in infrastructure are needed as are more concerted efforts to train, equip and motivate all patients in its use.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: IL was responsible for the conception of the work and the design of the review. IL and SG reviewed the article and IL led the drafting of the article with input from SG and DS. Both SG and DS provided critical revisions. The final version was approved by all authors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available. This is a review article and all material has been previously published.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Bhavnani SP, Narula J, Sengupta PP. Mobile technology and the digitization of healthcare. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1428–38. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pagliari C, Detmer D, Singleton P. Potential of electronic personal health records. BMJ 2007;335:330. 10.1136/bmj.39279.482963.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cdl M, Martins JO. The future of health and long-term care spending, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rimmer A. Technology will improve doctors' relationships with patients, says Topol review. BMJ 2019;364:l661. 10.1136/bmj.l661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation . Digital health, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/health-topics/digital-health#tab=tab_2

- 6.Reeves JJ, Ayers JW, Longhurst CA. Telehealth in the COVID-19 era: a balancing act to avoid harm. J Med Internet Res 2021;23:e24785-e. 10.2196/24785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell RE, Henstenburg JM, Cooper G, et al. Patient perceptions of telehealth primary care video visits. Ann Fam Med 2017;15:225–9. 10.1370/afm.2095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Deursen AJ, van Dijk JA. The first-level digital divide shifts from inequalities in physical access to inequalities in material access. New Media Soc 2019;21:354–75. 10.1177/1461444818797082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhaskar S, Bradley S, Chattu VK, et al. Telemedicine across the Globe-Position paper from the COVID-19 pandemic health system resilience program (reprogram) International Consortium (Part 1). Front Public Health 2020;8:556720. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.556720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhaskar S, Bradley S, Chattu VK, et al. Telemedicine as the new outpatient clinic gone digital: position paper from the pandemic health system resilience program (reprogram) International Consortium (Part 2). Front Public Health 2020;8:410. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perrin A. Digital gap between rural and nonrural America persists. Pew Research Centre 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selwyn N. Reconsidering political and popular understandings of the digital divide. New Media Soc 2004;6:341–62. 10.1177/1461444804042519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullen R. The digital divide: a global and national call to action. Electronic Library 2003;21:247–57. 10.1108/02640470310480506 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, et al. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2018;24:4–12. 10.1177/1357633X16674087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox NJ. Health sociology from post-structuralism to the new materialisms. Health 2016;20:62–74. 10.1177/1363459315615393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Dijk J. Achievements and shortcomings. Poetics 2006;34:221–35. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai J, Widmar NO. Revisiting the digital divide in the COVID-19 era. applied economic perspectives and policy 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Evans C. The coronavirus crisis and the technology sector. Bus Econ 2020;55:253–66. 10.1057/s11369-020-00191-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thornton J. Covid-19: how coronavirus will change the face of general practice forever. BMJ 2020;368:m1279. 10.1136/bmj.m1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webster P. Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. Lancet 2020;395:1180–1. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30818-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Wet C, Bowie P, O’Donnell C. ‘The big buzz’: a qualitative study of how safe care is perceived, understood and improved in general practice. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19:83. 10.1186/s12875-018-0772-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman G, McCaughan D. The effect of organisational culture on patient safety. Nurs Stand 2013;27:50–6. 10.7748/ns2013.06.27.43.50.e7280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Good Things Foundation . Digital inclusion in health and care: lessons learned from the NHS widening digital participation programme (2017-2020) 2020.

- 24.Watts G. COVID-19 and the digital divide in the UK. Lancet Digit Health 2020;2:e395–6. 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30169-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramsetty A, Adams C. Impact of the digital divide in the age of COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020;27:1147–8. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De' R, Pandey N, Pal A. Impact of digital surge during Covid-19 pandemic: a viewpoint on research and practice. Int J Inf Manage 2020;55:102171. 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scanzera AC, Kim SJ, Paul Chan RV. Teleophthalmology and the digital divide: inequities highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Eye 2021;35:1529–31. 10.1038/s41433-020-01323-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JGL, LePrevost CE, Harwell EL, et al. Coronavirus pandemic highlights critical gaps in rural Internet access for migrant and seasonal farmworkers: a call for partnership with medical libraries. J Med Libr Assoc 2020;108:651–5. 10.5195/jmla.2020.1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martins Van Jaarsveld G. The effects of COVID-19 among the elderly population: a case for closing the digital divide. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:577427. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.577427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seifert A, Batsis JA, Smith AC. Telemedicine in long-term care facilities during and beyond COVID-19: challenges caused by the digital divide. Front Public Health 2020;8:601595. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.601595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Visram S, Hussain W, Goddard A. Towards future healthcare that is digital by default. Future Healthc J 2020;7:180. 10.7861/fhj.ed-7-3-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, et al. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langlois EV, Straus SE, Antony J, et al. Using rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems and progress towards universal health coverage. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001178. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ai-Chi Loh Y, Chib A. Reconsidering the digital divide: an analytical framework from access to appropriation. The 69th annual international communication association (ICa) conference, Washington DC 2019.

- 36.World Health Organisation . WHO announces COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic. World Health Organisation, 2020. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paprotny D. Convergence between developed and developing countries: a centennial perspective. Soc Indic Res 2021;153:193–225. 10.1007/s11205-020-02488-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.NHSE . Who is at high risk from coronavirus (clinically extremely vulnerable), 2020. Available: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/people-at-higher-risk/who-is-at-high-risk-from-coronavirus-clinically-extremely-vulnerable/

- 39.Hughes T, Beard E, Bowman A, et al. Medical student support for vulnerable patients during COVID-19 - a convergent mixed-methods study. BMC Med Educ 2020;20:377. 10.1186/s12909-020-02305-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chunara R, Zhao Y, Chen J, et al. Telemedicine and healthcare disparities: a cohort study in a large healthcare system in New York City during COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber E, Miller SJ, Astha V. Characteristics of telehealth users in NYC for COVID-related care during the coronavirus pandemic. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020;27:1949–54. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whaley CM, Pera MF, Cantor J, et al. Changes in health services use among commercially insured us populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2024984. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eberly LA, Khatana SAM, Nathan AS, et al. Telemedicine outpatient cardiovascular care during the COVID-19 pandemic: bridging or opening the digital divide? Circulation 2020;142:510–2. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campos-Castillo C, Anthony D. Racial and ethnic differences in self-reported telehealth use during the COVID-19 pandemic: a secondary analysis of a US survey of Internet users from late March. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2021;28:119-125. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Runfola M, Fantola G, Pintus S, et al. Telemedicine implementation on a bariatric outpatient clinic during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: an unexpected Hill-Start. Obes Surg 2020;30:5145–9. 10.1007/s11695-020-05007-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gabbiadini A, Baldissarri C, Durante F, et al. Together apart: the mitigating role of digital communication technologies on negative affect during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Front Psychol 2020;11:554678. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.554678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campos-Castillo C, Laestadius LI. Racial and ethnic digital divides in Posting COVID-19 content on social media among US adults: secondary survey analysis. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e20472. 10.2196/20472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lal Dey B, Binsardi B, Prendergast R, et al. A qualitative enquiry into the appropriation of mobile telephony at the bottom of the pyramid. Int Market Rev 2013;30:297–322. [Google Scholar]

- 49.England N. Standard operating procedure for for general practice in the context of coronavirus (COVID-19), 2020. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/publication/managing-coronavirus-covid-19-in-general-practice-sop/

- 50.Facher L. 9 ways Covid-19 may forever upend the U.S. health care industry 2020. Available: https://www.statnews.com/2020/05/19/9-ways-covid-19-forever-upend-health-care/

- 51.D2N2 . New European social fund call to help address the digital divide, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allman K. Covid-19 is increasing digital inequality in the Oxfordshire digital inclusion project, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Majid A. Covid-19 is magnifying the digital divide, 2020. Available: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/09/01/covid-19-is-magnifying-the-digital-divide/

- 54.Stanford University . Digital divide, 2020. Available: https://cs.stanford.edu/people/eroberts/cs181/projects/digital-divide/start.html

- 55.JHUo M. Mortality analyses, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, et al. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:228–38. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jerolmack C, Khan S. Talk is cheap: ethnography and the attitudinal fallacy. Soc Method Res 2014;43:178–209. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med 2015;13:224. 10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abou-Setta AM, Jeyaraman M, Attia A, et al. Methods for developing evidence reviews in short periods of time: a scoping review. PLoS One 2016;11:e0165903-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clarke CS, Round J, Morris S, et al. Exploring the relationship between frequent Internet use and health and social care resource use in a community-based cohort of older adults: an observational study in primary care. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sweney M. Slow digital services are marginalising rural areas, MPS warn. The Guardian 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oxford Internet Institute . Oxford Internet surveys, 2020. Available: https://oxis.oii.ox.ac.uk/

- 63.Lloyds Bank . Lloyds bank UK consumer digital index 2020, 2020. Available: https://www.lloydsbank.com/banking-with-us/whats-happening/consumer-digital-index.html

- 64.Office of National Statistics . Internet access – households and individuals, great Britain: 2018, 2019. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/bulletins/internetaccesshouseholdsandindividuals/2018 [Accessed Dec 2020].

- 65.James J. The global digital divide in the Internet: developed countries constructs and third World realities. J Inf Sci 2005;31:114–23. 10.1177/0165551505050788 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bhaskar S, Rastogi A, Menon KV, et al. Call for action to address equity and justice divide during COVID-19. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:559905. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.559905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Giansanti D, Veltro G. The digital divide in the era of COVID-19: an investigation into an important obstacle to the access to the mHealth by the citizen. Healthcare 2021;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kulkarni M. Digital accessibility: challenges and opportunities. IIMB Manag Rev 2019;31:91–8. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rich MJ, Pather S. A response to the persistent digital divide: critical components of a community network ecosystem. Inform Develop 2020;6 10.1177/0266666920924696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.BBC . 'Digital poverty' in schools where few have laptops, 2020. Available: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-52399589

- 71.Helsper E, Galacz A. Understanding the links between social and digital inclusion in Europe. The World Wide Internet: Changing Societies, Economies and Cultures 2009:146–78. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vasilescu MD, Serban AC, Dimian GC, et al. Digital divide, skills and perceptions on digitalisation in the European Union-Towards a smart labour market. PLoS One 2020;15:e0232032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Daniel E. Covid-19 highlights “crucial need” for digital infrastructure across the UK, 2020. Available: https://www.verdict.co.uk/uk-digital-infrastructure/

- 74.Lustria ML, Smith SA, Hinnant CC. Exploring digital divides: an examination of eHealth technology use in health information seeking, communication and personal health information management in the USA. Health Informatics J 2011;17:224–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hilbert M. The end justifies the definition: the manifold outlooks on the digital divide and their practical usefulness for policy-making. Telecomm Policy 2011;35:715–36. 10.1016/j.telpol.2011.06.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nominet . Digital access for all launches to help solve problem of digital exclusion, 2020. Available: https://www.nominet.uk/digital-access-for-all-launches-to-help-solve-problem-of-digital-exclusion/

- 77.Media P. Broadband providers to lift data caps during Covid-19 lockdown. The Guardian 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brookings . What the coronavirus reveals about the digital divide between schools and communities, 2020. Available: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2020/03/17/what-the-coronavirus-reveals-about-the-digital-divide-between-schools-and-communities/

- 79.Adler NE, Ostrove JM, Status S. and Health: What We Know and What We Don't. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;896:3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stringhini S, Carmeli C, Jokela M, et al. Socioeconomic status and the 25 × 25 risk factors as determinants of premature mortality: a multicohort study and meta-analysis of 1·7 million men and women. Lancet 2017;389:1229–37. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32380-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Keith RE, Crosson JC, O'Malley AS, et al. Using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: a rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation. Implement Sci 2017;12:15. 10.1186/s13012-017-0550-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dryhurst S, Schneider CR, Kerr J, et al. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J Risk Res 2020;23:994–1006. 10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Makri A. Bridging the digital divide in health care. Lancet Digit Health 2019;1:e204–5. 10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30111-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Protheroe J, Whittle R, Bartlam B, et al. Health literacy, associated lifestyle and demographic factors in adult population of an English City: a cross-sectional survey. Health Expect 2017;20:112–9. 10.1111/hex.12440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bentley CL, Powell LA, Orrell A, et al. Addressing design and suitability barriers to Telecare use: has anything changed? Technol Disabil 2014;26:221–35. 10.3233/TAD-150421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Clark J, McGee‐Lennon M. A stakeholder‐centred exploration of the current barriers to the uptake of home care technology in the UK. J Assist Technol 2011;5:12–25. 10.5042/jat.2011.0097 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zanaboni P, Wootton R. Adoption of routine telemedicine in Norwegian hospitals: progress over 5 years. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:496. 10.1186/s12913-016-1743-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Haidt J, Allen N. Scrutinizing the effects of digital technology on mental health. Nature 2020;578:226–7. 10.1038/d41586-020-00296-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cherns A. Principles of Sociotechnical design revisted. Human Relation 1987;40:153–61. 10.1177/001872678704000303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chalfont G, Mateus C, Varey S, et al. Self-Efficacy of older people using technology to Self-Manage COPD, hypertension, heart failure, or dementia at home: an overview of systematic reviews. Gerontologist 2021;61:e318–34. 10.1093/geront/gnaa045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gilbert AW, Jones J, Stokes M, et al. Factors that influence patient preferences for virtual consultations in an orthopaedic rehabilitation setting: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e041038. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, et al. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating Nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e367. 10.2196/jmir.8775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Islind AS, Lindroth T, Lundin J, et al. Co-designing a digital platform with boundary objects: bringing together heterogeneous users in healthcare. Health Technol 2019;9:425–38. 10.1007/s12553-019-00332-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.NHS Digital . Digital inclusion in health and social care, 2020. Available: https://digital.nhs.uk/about-nhs-digital/our-work/digital-inclusion/digital-inclusion-in-health-and-social-care

- 95.Hesse BW, Moser RP, Rutten LJ. Surveys of physicians and electronic health information. N Engl J Med 2010;362:859–60. 10.1056/NEJMc0909595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huo J, Desai R, Hong Y-R, et al. Use of social media in health communication: findings from the health information national trends survey 2013, 2014, and 2017. Cancer Control 2019;26:107327481984144. 10.1177/1073274819841442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Calixte R, Rivera A, Oridota O, et al. Social and demographic patterns of health-related Internet use among adults in the United States: a secondary data analysis of the health information national trends survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:6856. 10.3390/ijerph17186856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Glik DC. Risk communication for public health emergencies. Annu Rev Public Health 2007;28:33–54. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ranjit YS, Lachlan KA, Basaran A-MB, et al. Needing to know about the crisis back home: disaster information seeking and disaster media effects following the 2015 Nepal earthquake among Nepalis living outside of Nepal. Int J Dis Risk Reduct 2020;50:101725. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101725 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, et al. Social media use in healthcare: a systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:442. 10.1186/s12913-016-1691-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Garfin DR. Technology as a coping tool during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: implications and recommendations. Stress Health 2020;36:555–9. 10.1002/smi.2975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Phelan JC, Link BG, Diez-Roux A, et al. "Fundamental causes" of social inequalities in mortality: a test of the theory. J Health Soc Behav 2004;45:265–85. 10.1177/002214650404500303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Phelan JC, Link BG. Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annu Rev Sociol 2015;41:311–30. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav 2010;51 Suppl:S28–40. 10.1177/0022146510383498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bristol to tackle ‘skepticism’ about Covid-19 vaccine among BAME communities. Available: https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/news/bristol-news/bristol-tackle-skepticism-covid-19-4804469 [Accessed Dec 2020].

- 106.Jones Z. Why some black amerocans are sceptical of the covid-19 vaccine, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lehner A, Nuißl K, Schlee W, et al. Staying connected: reaching out to psychiatric patients during the Covid-19 lockdown using an online Blog. Front Public Health 2020;8:592618. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.592618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Seabrook EM, Kern ML, Rickard NS. Social networking sites, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review. JMIR Ment Health 2016;3:e50. 10.2196/mental.5842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Choi NG, Marti CN, Bruce ML, et al. Six-month postintervention depression and disability outcomes of in-home telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed, low-income homebound older adults. Depress Anxiety 2014;31:653–61. 10.1002/da.22242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Marsch LA, et al. The future of mental health care: peer-to-peer support and social media. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2016;25:113–22. 10.1017/S2045796015001067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mickus MA, Luz CC. Televisits: sustaining long distance family relationships among institutionalized elders through technology. Aging Ment Health 2002;6:387–96. 10.1080/1360786021000007009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Porges SW. Social engagement and attachment: a phylogenetic perspective. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003;1008:31–47. 10.1196/annals.1301.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.NHSx . Care homes to benefit from tech to help residents keep in touch with loved ones, 2020. Available: https://www.nhsx.nhs.uk/news/care-homes-benefit-tech-help-residents-keep-touch-loved-ones/

- 114.Wei K-K, Teo H-H, Chan HC, et al. Conceptualizing and testing a social cognitive model of the digital divide. Inform Sys Res 2011;22:170–87. 10.1287/isre.1090.0273 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Home LSS, School B. Public or mobile: variations in young Singaporeans' Internet access and their implications. J Computer-Med Com 2009;14:1228–56. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Brandtzæg PB. Towards a unified Media-User typology (mut): a meta-analysis and review of the research literature on media-user typologies. Comput Human Behav 2010;26:940–56. 10.1016/j.chb.2010.02.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hargittai E, Piper AM, Morris MR. From internet access to internet skills: digital inequality among older adults. Univers Access Inf Soc 2019;18:881–90. 10.1007/s10209-018-0617-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.DiMaggio P, Hargittai E, Neuman WR, et al. Social implications of the Internet. Annu Rev Sociol 2001;27:307–36. 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Fernández-de-Álava M, Quesada-Pallarès C, García-Carmona M. Use of ICTs at work: an intergenerational analysis in Spain / Uso de las tic en El puesto de trabajo: un análisis intergeneracional en España. Cultura y Educación 2017;29:120–50. 10.1080/11356405.2016.1274144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kirk CP, Swain SD, Gaskin JE. I’m proud of it: consumer technology appropriation and psychological ownership. J Market Theory Pract 2015;23:166–84. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stewart J. The social consumption of information and communication technologies (ICTs): insights from research on the appropriation and consumption of new ICTs in the domestic environment. Cogn Technol Work 2003;5:4–14. 10.1007/s10111-002-0111-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Selwyn N, Gorard S, Furlong J. Whose internet is it anyway?: exploring adults’ (Non) use of the internet in everyday life. Europ J Commun 2005;20:5–26. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Haugerud T. Student teachers learning to teach: the mastery and appropriation of digital technology. Nordic J Digi Lit 2011;6:226–38. 10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2011-04-03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-053440supp001.pdf (70.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. This is a review article and all material has been previously published.