Abstract

Chinese students’ issues and concerns of studying abroad amid the COVID-19 pandemic have been largely neglected in the tourism and hospitality education research. Based on the actor-network perspective, this paper explores the network of issues and concerns of Chinese students who have planned to study abroad. In-depth interviews, observations, and open-ended questionnaires are employed with a purposive sample of 16 hospitality students from a university in Macau. We identify five major concerns and issues namely health risk, dissatisfaction with online study, feeling difficult to get into a top university, discrimination of Chinese in the West, and perception of restricted opportunity to make a cross-cultural exchange.

Keywords: Chinese students, Study abroad, COVID-19, Parents, Higher education agent, Networks

1. Introduction

The demand for Western higher education has been growing in the recent decades in the People's Republic of China (hereafter China) since it is a source of accumulating cultural capital (Collins, 2013; Findlay, King, Smith, Geddes, & Skeldon, 2012; Ganotice Jr, Downing, Chan, & Yip, 2020); a compensation strategy to get into a prestigious university in China (Bodycott, 2009); improving employability (Beine, Noël, & Ragot, 2014; Fong, 2011; Waters, 2009); and a gateway to migration (Thieme, 2017). For instance, in the academic year 2018/2019, the UK attracted 120,385 students from China, accounting for 35% of all non-EU international students (UK Higher Educa tion Statistics Agency, 2020). As the COVID-19 pandemic has swept across the globe, yet showed little sign of diminishing, students, academic staff, universities, and many more actors are facing various challenges. From a global perspective, much focus is paid to the decrease of international student mobility (e.g., Mercado, 2020; Yıldırım, Bostancı, Yıldırım, & Erdoğan, 2021). The development of a virtual learning environment has become an agenda for universities (e.g., Carius, 2020; ICEF Monitor, 2020), which is challenging for international students who aim to experience a foreign culture. Yet the research direction of international students amid COVID-19 is place specific and multifaceted which requires academic investigation (Yuan, Sude, Chen, & Dervin, 2021).

Specifically, for Chinese students seeking to study abroad amid the current pandemic, several issues and challenges emerge in their decision-making process. In the literature, it is found that these issues and concerns exist in isolated entities. For example, some studies demonstrate Chinese students worrying about the safety issue in the UK and changing visa application policy (Yang, Mittelmeier, Lim, & Lomer, 2020); others point to the racial discrimination issues against Chinese in the States (Ma & Miller, 2020) while an emerging stream of studies sought to investigate how Chinese parents are emotionally involved in improving the well-being of their overseas child (Hu, Xu, & Tu, 2020). However, these studies largely ignore that network of relationships among the study abroad actors. This overlooked lacuna is the focus of this study as it contributes to the literature by connecting the human and material actors that have resulted in various concerns and issues in association with study abroad decisions. Important decisions made by the students in this research, in return, impact a given network of actors including their immediate universities, parents, friends, higher education (HE) agents, and receiving institutions abroad. To illustrate the interaction among the actors and subsequently the resulting issues and concerns, we adopt the Actor-Network Theory (ANT) (Latour, 2013; Park, Park, & Lee, 2020), which offers theoretical insights into study abroad among Chinese students. ANT is an analytical framework that acknowledges the agency possessed by all human and non-human actors (e.g., material, objects, technology, etc.) (Latour, 1987). These actors are relational and form a network that explains how they react to each other. The agents of this study, to name a few that could be overlooked in the literature that specifically explores the pandemic impact on Chinese studying abroad decision, include filial relations, the competitive job market in China, or the higher education agency's role in facilitating mass application. This study reveals the network of actors and concerns informed by empirical work.

This study is subject to a particular temporal and spatial context, considering the in-situ and ongoing development of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated local policies spanning across over a year (Agyeiwaah, Adam, Dayour, & Badu Baiden, 2021). Our respondents were final-year hospitality students studying in Macau, who were in the process of applying for postgraduate taught programmes commencing in September 2021. When the first phase interview was taking place, the three most popular destinations these students chose to further study experienced distinct degrees of challenges. To illustrate the context, the cumulative confirmed cases of three regions during the interview period is charted (i.e., between November 2020 and January 2021): There was one case in Macau (Center of Disease Control and Prevention, 2021); 5153 in Hong Kong (LKS Facu lty of Medicine School of Public Health, 2021) and 2,774,871 in the United Kingdom (Public Health England, 2021). In April this year, when we finally checked on the final decision of the respondents’ study choice, state-led vaccination programmes have been taking place, which understandably adds food for thought of the situation. In terms of the mode of course delivery, as of April this year, apart from most universities in Macau that have resumed face to face teaching since the term commencing in September 2020, universities in Hong Kong and United Kingdom are still employing either online or hybrid mode in managing the teaching and learning environment, with no guarantee that campus will re-open in September 2021. The in-situ research context is particularly significant during the pandemic era.

We probed into the decision-making process in association with the above phenomena. Given the exploratory nature of this study, a qualitative approach grounded in the interpretivism epistemology is employed to unpack the observed issues. The first phase of the investigation was made in November and December 2020. The authors conducted an in-depth interview with the final year students. We have updated the students’ decisions in April 2021 to capture the change in the decision and the latest development of their study plan. In short, we attempt to elaborate on the complexity and influence of various actors in student study abroad decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic. We aim to contribute to the literature that explores Chinese students studying abroad during the pandemic by addressing the research question: What are the issues and concerns of Chinese students studying abroad during the COVID-19 pandemic? Our finding illustrates the interaction among various human and non-human actors and how students calculate the gain and loss in making their decision. This research addresses the inadequate attention to the dynamic and complex inter-relationship in the study-abroad decision.

2. Literature review

This section constructs two sub-sections of the literature review. First, a review of actor-network theory in the hospitality context is presented. The section argues that within the hospitality epistemology, the research focus is heavily preoccupied with human actors; and non-human agency and materiality are largely side-lined (Chen & Wu, 2021; Park et al., 2020). Second, we identify all the “COVID-19” literature relevant to the issues of Mainland Chinese international students, in which there are reports on potential students’ study intentions and their concerns amid the pandemic.

2.1. Theoretical perspective: Actor-network theory and hospitality and tourism study abroad

Originating from sociological studies of science and technology in the 1980s, actor-network theory (ANT) has diffused into several contexts including tourism and hospitality research (Chen & Wu, 2021; Jóhannesson, 2005; Jørgensen, 2017; Park et al., 2020). ANT involves the examination of the actions that various actors employ to mobilize allies and resources and to construct diverse networks (Garrety, 1997; Latour, 1987). Such mobilisations are evident in both Latour's (1983) and Callon's (1984) works. For instance, Latour (1983) demonstrates how different actors were convinced by Pasteur to successfully enroll in a relational network to provide treatment and cure to Anthrax disease. On the other hand, Callon (1984) employed ANT to examine how to preserve a population of scallops, marine biologists enrolled local fishermen and scientific colleagues in a network of relations. Central to this examination is the emphasis on the ‘relational materiality’ of our environment (Law, 1992). Consequently, all objects, technologies, materials, and living things have agency, and any investigation must consider interactions with both human and non-human since actions are shaped by various living and non-living actors (Fountain, 1999; van der Duim, Ren, & Jóhannesson, 2017). Within the theory of ANT, there is a volitional actor, or preferably actant, who could be an agent, collective or individual, and could associate or otherwise dissociate with other agents. The engagement in any network associations defines actors and accord them with a substance, action, and intention. Each network comprises of processes and activities that actors perform as part of their relationship with other actors (Ritzer, 2007). A translation process allows the establishment of identities and conditions of interactions which enables the principal actor to transform heterogeneous entities into a cohesive network (Dedeke, 2017).

The heterogeneous and fragmented nature of the tourism and hospitality industry which extends into its educational sub-sector implies that the mechanisms of mobilizing study abroad programs in hospitality, leisure, sports, and tourism education must be grounded within actor-network theory. A growing body of research point out that study abroad consist of diverse network relations among humans (e.g., educational institutions, teachers, parents, students, and governments) and non-humans (e.g., homestay, transportation, language school, personal statements, resumes, and reference letters) connected to different but interdependent relational networks. For example, Collins (2008) reports the role of educational agents in mobilizing Korean students to study abroad in New Zealand through an established supply chain network (i.e., homestay, language school, transportation). These networks with educational agencies of study abroad is a well-established practice in both Nepal (Thieme, 2017) and China (Cebolla-Boado, Hu, & Soysal, 2018; Lan, 2020; Serra Hagedorn & Zhang, 2010). However, there is a dearth of studies exploring the networks of issues and concerns among this group in the context of COVID-disruptions within tourism and hospitality education.

Within tourism and hospitality education research, there has been an overwhelming emphasis on human actors ignoring the significant role of non-human actors despite recent arguments that non-human actors such as tourist attractions have agency (Chen & Wu, 2021; Park et al., 2020). For example, Chen, Dwyer, and Firth (2015) investigate the role Chinese students play in place branding in Australia and conclude their satisfaction and attachment to Australia are positively related to different behavioural outcomes. Davidson and King (2008) examine the perceptions and experiences of Chinese students in Australia and identify issues of course selection for a masters' degree course. While these studies are significant, there is a failure to examine the networks of relations among both human and non-human agents participating in students’ study abroad to provide a holistic view on the issues and concerns of this group. Nonetheless, the COVID-19 disruption has revealed the working of human and non-human agents, fabricating a network that reproduces a decision-making process of students who have long planned to further study abroad. Accordingly, we eschew reductionist frameworks in previous tourism and hospitality education research and employ ANT to recognize that both humans and non-humans have agency. Consequently, study abroad is a form of social practice that embodies and materially mediates humans (e.g., study abroad agents, students, university professors, teachers, and parents), non-humans (e.g., educational policy standards, reference letters, resumes, and COVID-19 pandemic), social institutions (e.g, government agencies), educational institutions (e.g., local universities and non-local universities) and social media platforms to form a relational study abroad network of tourism and hospitality education. Given such diversity of actants, ANT is an appropriate theoretical framework to understand the network of issues and concerns and the concomitant impacts of the disruptions created by COVID-19.

2.2. The COVID-19 pandemic and concerns of (potential) overseas Chinese students

Research on the intersection between the pandemic and study abroad on Mainland Chinese students could be broadly categorized by the different stages of the study abroad. Taking management and prospective approach, some papers investigate potential students’ attitude, concerns, and (un)willingness to study in a foreign land that is being or expected to be threatened by the pandemic (see Mok, Xiong, Ke, & Cheung, 2021; Yang et al., 2020). While some look at the issues in association with those students who are concurrently abroad. Within this category, it includes the well-being of the students who were once stranded overseas (see Ma & Miller, 2020; Ma & Zhan, 2020), Chinese students and parents performing emotional work during the home-fleeing process (Hu et al., 2020), the political economy of international study (Pan, 2020) and transnational identity struggle of Chinese students against the backdrop of growing intense relations between China and the West (Wang, 2020).

How the Covid-19 pandemic has affected or will affect, transnational mobility of Chinese students attracts research interest when the higher education sector in some Western economies has been increasingly dependent on the Chinese market. Between March and April 2020, British Council surveyed 11,000 Chinese students and found out that 22% were likely to cancel their study plans, while 39% were unsure about it (British Council, 2020). A smaller-scale survey conducted by academics in May 2020 shows a staggering result - out of the 1267 Mainland Chinese students answering whether they are “interested in studying abroad after the COVID-19 pandemic”, 91% said No (Mok et al., 2021, p. 5). The authors also report that popular choices of postgraduate study destinations will be switching from traditional Western countries (i.e., the USA and the UK) to Hong Kong, Japan, and Taiwan. However, according to UK's Universities and Colleges Admissions Service, a record high figure of 12,000 Chinese students have received an offer of a place to study the 2020/21 academic year – a 22% increase compared to the previous year (The Pie News, 2020). The UK higher education's final intake figures of Mainland Chinese students for the study year 2020/21 is not yet released, it is hard to comment whether the above survey results reflect the fear of the applicants when Europe and the States reported high death tolls and confirmed cases of the pandemic, or that these students have applied for postgraduate study before they did the survey.

For the 2021/22 academic year, Yang et al. (2020) conducted an in-depth investigation on Chinese students' concerns and intention to study in the UK. In general, from the responses of 35 Chinese higher education agencies and consultants, Chinese applicants' concerns are wide-ranging, including safety in the UK, the format of courses, unclear schedule of language tests and pre-sessional courses, possible change of visa application policy, and whether tuition fee could be adjusted. Nevertheless, the respondents believed that their clients were still intended to study in the UK. The reasons include the Chinese applicants' optimism that the pandemic will be contained eventually, their satisfaction with the open communication with the UK universities, and the conventional and perceived quality study and life experience in the UK. In other words, the online mode of course delivery is what they hoped to avoid. Yang et al. (2020) reveal two important actors in organizing student intention to study in the UK. The first one is certainly the Chinese higher education agent sector, which acts as a bridge between universities and students in circulating information and offers consultation to students. The second actor is parents, who are concerned about their children's safety and study environment, co-participating in communication with the HE agent and making decisions together with the students. This is particularly relevant to our study, as it aims to reveal the working of different actors in shaping their decision-making process.

From the perspective of health and well-being, Ma and Miller (2020) explore the anxiety of mainly Chinese students concurrently studying in the United States, in which the quantitative data was collected in April 2020, when the States had declared a national emergency. The worries and fear faced by the respondents come from not only the risk of the disease and their perceived racial discrimination in the States but also their family and friends who had expectations and pressing demands on the Chinese students. What has further puzzled these overseas students is that the advice and recommendations could contradict each other, such as going home to avoid the pandemic risk versus staying in the States to prevent infection during travel. Some students' academic performance was also affected by having to experience anxiety (Ma & Miller, 2020). Observing Chinese students in the UK, Hu et al. (2020) analyze how Chinese students' home-fleeing contingency has been passed to their families back in China. Particular attention is paid to the parents' painstaking effort in sourcing information and utilizing personal relations to secure a flight ticket (or more) for their loved one to come home safe. Such a process involved individuals performing to be emotionally engaged in the event while suppressing their worries and even anger, which is called, in the authors’ words, family-mediated infrastructure. This infrastructure is built on filial love, with which the emotional work “provides unique clues to highly dynamic relationships between family members in the infrastructure process, as they constantly shift between multiple roles as collaborators, parents, children, and liability guarantors” (Hu et al., 2020, p. 21).

Ma and Zhan (2020) connect the Sino-US tension to the reported suffering of Chinese students, arguing that it was the authority-led power that constructs the stigma through labelling Chinese as “the bearer of the coronavirus”. Their mask-wearing behaviour was not viewed as “normal” in mainstream society before the pandemic hit the States. Some Chinese students chose to skip the class to avoid being embarrassed and discriminated against. The actors involved in conditioning the wellbeing of overseas Chinese students, according to Ma and Zhan, include the government, their peers, and even professors on campus. From a political economy perspective, Pan (2020) argues that the Coronavirus exposes the ambiguity of the neoliberal model of international higher education. The argument is based on three reasons. First, the travel ban controls student mobility and universities receive a government subsidy. Second, for Chinese students, the more contentious political relations between China and the West results in growing scrutiny on their access to international education. Third, paying a high tuition fee for international study while having no control over the services under the pandemic has prompted Chinese customers to re-think the value of a Western diploma. Students were forced to move out from campus on very short notice, made to switch to online teaching, and given very limited financial and mental support from the institution. Wang (2020) argues that deglobalisation and growing nationalism have contributed to the unprecedented challenges faced by Chinese students. Chinese youngsters could be trapped in the ideological differences between the West and China. However, their presence as international students abroad was borne to develop a cosmopolitan identity through cross-cultural encounters, which might grapple with their strong national identity.

The Actor-network theory offers an analytical framework to understand how the complex human-induced international relations at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic have generated non-human ideologies as an agency that enters the cross-cultural and educational space. Materiality is involved in the pandemic outcome. For example, having Zoom class in a lock-down city. There have been actions of top-down measures in controlling international student mobility and experience. A network is formed when each actor performing its part of the established relationships with other actors (Ritzer, 2007) subsequently brings new environmental changes. These changes may come in the form of issues and concerns not only for those who are living the experience in a different political and cultural environment, but also those organizing potential Chinese individuals’ study abroad as part of accumulating social and cultural capitals. We explore these issues using qualitative methods of inquiry.

3. Methods

3.1. Reflexivity of the research purpose

Reflexivity in research is important to help methodological reflection and research purpose (Bourdeu, 2004). This section reflects the study purpose. This research idea originated when the authors observed the further education consumption patterns from their students who will be graduating in 2021 from one of the universities in Macau offering hospitality and tourism programmes. The authors observed that the international higher education agents are trusted by their final year students while parents are found to be involved from a small to great extent in the study-abroad decision as their children reflect on their study plan. These sets of empirical observations prompted us to explore the issues relevant to how the novel pandemic impacts decisions of studying abroad among Chinese youngsters. For these upcoming batch of fresh graduates, compared to their senior fellows, they wrestle between their persistent desire to get a second degree overseas and their worries about not only COVID-19, but the associated issues brought about by the pandemic, with which many human and non-human actors are involved. However, they are still facing the reality that a certificate from a prestigious university abroad represents a strong credential for them to compete in the Chinese job market, appealing to the employers who are coping with the ever-increasing supply of university degree holders (Hansen & Thøgersen, 2015).

3.2. Target population, qualitative instrument design, and data collection

This study targeted final year students in one of the universities in Macau offering tourism and hospitality programmes. For the anonymity purposes of the authors, the university name is omitted. We targeted final year students applying for study abroad programmes due to their lived experiences regarding the problem of interest to this study. Our criteria for the selection of the participants were that, first, the participant must be a tourism and hospitality student who has applied to study abroad. Second, they must be a student in the faculty of the researchers. The approach chosen in this study was qualitative. Qualitative approaches provide “rich descriptions of complex phenomena; track unique or unexpected events; and illuminate the experience and interpretation of events by actors with widely differing stakes and roles” (Sofaer, 1999, p. 1101). Based on the research question that explores the issues and concerns of Chinese students studying abroad during the COVID-19 pandemic, the research approach was grounded in an interpretivism epistemology. We employed three instruments including in-depth interviews, open-ended questions, and observations which are important qualitative instruments to obtain relevant data (Phellas, Bloch, & Seale, 2011). Our choice of initial in-depth interviews was appropriate to elicit detailed information that could not be ascertained with a structured questionnaire (Bryman, 2008; Creswell, 2013). The in-depth interview was further followed by open-ended questionnaires and observations in the second stage of data collection which are explained in the subsequent paragraphs. The data collection instrument was designed in both Chinese and English versions for students to choose their preferred language for participating. While all the students were Chinese, this bilingual design was due to two factors. First, the official language for teachers’ interaction with students in English, and second, one of the authors is non-Chinese who required the English language to participate in the interview discussions and probing. Given that the lead author was a native speaker (bilingual), it was easier to transition between both languages successfully. English was the original language that informed the interview design, and it was later translated into Chinese by the lead author who is native Chinese. The translated version was further examined by three bilingual post-graduate students to check the readability and comprehensibility of the statements. A bilingual instrument allowed both authors to understand the interview process during the data collection in two phases (Lee, Sulaiman-Hill, & Thompson, 2014).

The first phase was conducted in November–December 2020 at the early stages of students' applications to various universities in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Hong Kong. In this first instrument, our in-depth interview covered five main issues of relevance. The first section of the interview explored the places of choice for study abroad and how COVID-19 has impacted those choices. In this part, we probed how many schools have been applied, the programs, and countries. The second section of the instrument examined the mode of studies of these chosen universities in terms of online learning or the traditional mode of teaching. As part of this section, we probed further into their expectation of studying abroad in terms of the type of teaching and learning. We further probed into their preference of staying in nearby countries such as Macau or Singapore with relatively safe COVID-19 cases than other countries with higher COVID-19 cases. We also asked questions about the role their parents play in these choices. The third section sought to examine the value of study abroad during COVID-19 in relation to value for money and cultural enlightenment abroad. The fourth section focused on the concerns and anxiety of studying abroad during the pandemic. We, therefore, asked a simple question: “Are you worried” about studying abroad during this pandemic season? We further probed what are your worries and concerns? The fifth section sought to explore the agency's role in informing students about the study abroad school's COVID-19 regulations and mode of delivery. The interview lasted between 40 and 60mins for each student.

Following this first phase, the second phase of other important issues and follow-up open-ended questionnaires were designed and conducted in March–April 2021. This part also had five sections with the first part seeking to identify which of the offers have been received by students. We asked students to list all the schools they have received offers from. The second part explored their decision-making process. For example, what is their final decision on the offers received? The third section examined the deep thoughts of participants during these past three months of significant changes in the COVID-19 pandemic including vaccine rollout in many countries. We explored specific changes between the time we did the first interview and second stage data collection to understand their changing anxiety within this period of data collection. The fourth section specifically asked them about the influence of the COVID-19 vaccination on their study abroad decision-making. The fifth section examined students’ thoughts of enjoying travel to the UK amid the COVID-19 pandemic. We have also made further individual follow-up questions to some students to learn more about their decision. The duration of answering the open-ended questions was expected to be between 20 and 30 min and most students mailed it back the same day or the next day after receipt of the instruments. During both phases of data collection, further observations regarding reference letters and higher education agents' activities were done concurrently.

While the data collection of the first phase was done in person on the university campus, the second phase was mailed to students or shared via WeChat for students to respond and send back to the authors. This approach was used because at the time of the data collection in the second phase, most final year students were taking their internship outside Macau and COVID-19 restrictions made in-person interviews impossible. We purposively selected 16 respondents for both two phases of studies and compiled responses to be further analysed using qualitative management software. Although the sample size in qualitative research is contested, Sandelowski (1995) contends that the size should not be too little to impede data saturation and should not be too large for deeper analysis. Many methodologists suggest a sample size ranging between 10 and 30 are acceptable sizes (Bertaux, 1981; Marshall, Cardon, Poddar, & Fontenot, 2013; Sandelowski, 1995). We follow the sample size suggestion by Marshall et al. (2013) that 15–30 interviews are adequate for an in-depth analysis.

3.3. Qualitative data analysis

The data analysis proceeded once all data collection procedures were completed. We conduct a back-to-back translation for our Chinese responses while those in English were analysed directly. Our first phase interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim while the second phase was content analysed given that it was in a written format. We resorted to the QDA Miner, a qualitative data software, to facilitate further analysis of the transcripts of both phases of data collection. In line with the research question of this study, we began with a line-by-line coding by reviewing the transcript data and identifying key issues. We did this by following Corbin and Strauss's (1990) three coding procedures of open, axial, and selective coding in grounded theory. Accordingly, the initial open coding generated 30 codes. Some of our 30 open codes included stories regarding “higher education agents mediating students' study abroad”; students contacting these agents through WeChat; parents making decisions for their children using various networks”; students deciding which country to choose based on COVID-19 cases and what their parents think of those schools based on university ranking. This first stage of open coding was followed by a second stage axial coding where we sought to relate sub-categories to other major categories within the data to ensure coherency of emerging relationships in the data. We there analysed the network relationship within the data by identifying how educational agents are related to students and parents from a network of study abroad relationships in the data. Further relationships between human agents such as the educational agents and WeChat were also detected as agents employed social media as means to connect with students. The final stage of selective coding sought to organise the themes based on the broad research question regarding the issues and concerns of studying abroad. For example, we grouped “educational higher education agents, money and WeChat” as a broad theme to explain the issues and concerns regarding this theme identified in the study. This three-stage coding was aided by the QDA Miner software. The coding frequency, text retrieval, coding co-occurrences, and cluster analysis tools in QDA miner software facilitated this process.

The analysis process followed the reliability and validity process in qualitative research. Qualitative researchers have argued for the need for trustworthiness and rigor in qualitative research to ensure the results are valid and reliable. Lincoln and Guba (1985) argue that qualitative researchers must ensure trustworthiness through four criteria namely credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability. These four criteria suggestions were followed in this study to ensure the entire research process and the results presented are valid and reliable to tourism academia. In this study, we ensured data credibility through clear depiction and evidence of the transcribed text which reflects Chinese students' lived experiences. During data collection, respondents were allowed to reflect on their responses without any influence. To ensure data dependability, both researchers engaged in frequent dialogue after each interview on the responses provided to ensure they are dependable. The authors both reviewed each other's transcribed material to validate the emerging themes. Further triangulation was done to ensure data transferability among the research team. To ensure, confirmability, the entire research process involved the use of a reflexive journal to record notes and reflect on daily encounters with participants. Reflexivity and bracketing allowed both authors to be cautious of their own biases, assumptions, and beliefs that may influence the research process (Cypress, 2017). The outcome of this trustworthy analysis is presented and discussed subsequently.

4. Findings and discussion

Demographically, our data had more females (62.5%) than males (37.5%). Students have applied to universities abroad (e.g., UK, Switzerland, Australia, and Singapore) and within China (Hong Kong and Macau) (Table 1, Table 2 ). In general, the students we have interviewed perceive the health risk of COVID-19 from a small to a larger extent. COVID-19 health-related risk plays a role in the study-abroad decision-making of the respondents and their families. Therefore, the risk of the pandemic is anyway demonstrated in the whole analysis. The purpose of this finding is to chart the actors that influence our respondents' study plans not only in their own right but also in how they interact with other actors. Table 1 presents the profile of respondents. To retain the authenticity of the respondents’ narratives, we present the original verbal, written expressions and observations.

Table 1.

Study-abroad decisions and application particulars.

| Pseudonyms | Gender | Study decisions made in April 2021 | Total number of programmes respondents have applied | Study destinations of applied programmes |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | Australia | Switzerland | Singapore | Hong Kong | Macau | ||||

| P1 | Female | Keep study plan | 8 | 8 | |||||

| P2 | Female | 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| P3 | Female | 6 | 6 | ||||||

| P4 | Male | 10 | 8 | 2 | |||||

| P5 | Female | 9 | 9 | ||||||

| P6 | Male | Changed to take a gap year | 7 | 5 | 2 | ||||

| P7 | Female | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| P8 | Female | 5 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| P9 | Female | Undecided | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| P10 | Male | 5 | 5 | ||||||

| P11 | Female | 7 | 7 | ||||||

| P12 | Female | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| P13 | Female | 9 | 5 | 4 | |||||

| P14 | Male | 5 | 3 | 2 | |||||

| P15 | Male | 8 | 7 | 1 | |||||

| P16 | Male | No reply for the second investigation | 10 | 10 | |||||

Table 2.

Human and non-human agents, and the resulting issues and concerns of studying abroad.

| Human agents | Non-human agents | Issues/concerns: |

|---|---|---|

|

- Reference letter - university and programmes - World university ranking |

- Feeling difficult to get into top universities due to intense competitions - Mass application and diversification of study destination as ways to offer more possibilities |

|

- WeChat (social media platform) - Money |

|

|

- Filial love - One-child policy - Pandemic - Host country environment |

- Health risks - Racial discrimination |

|

- Vaccination - Online study - Host culture |

- Dissatisfaction of online study - Restricted opportunity of cross-cultural encounter |

|

- Internship - Chinese competitive study environment |

- Reflecting on the value of gaining industry experience and studying abroad |

|

- World university ranking - Competitive Chinese job market |

- Giving themselves a second chance to re-apply next year |

4.1. Reference letters, higher education agents, and lecturers

The Autumn term of the academic year always finds university professors moaning about their time being occupied by students, including the authors of this paper. It became worse in Autumn 2020. Between September and December 2020, both authors of this paper have received respectively 27 and 20 requests of being the referee of our final year students. On estimation, each student on average asked for five references, in an unlucky and extreme case, up to 10 references. Thus, a process of translation occurs where university professors are transformed into referees in this network of study abroad where they shape and reshape the potential future study of students (Dedeke, 2017; Jóhannesson, 2005). A good number of students would ask us to just sign our name on a completed letter manufactured by their agent. Being too responsible as a referee could have much time killed by the story-writing chore (if they can't stand the mechanical piece of sample and flamboyant description of their student). Referees have to further engage in talking and mentoring the students, and offering feedback with frustration to the CV and personal statement - the other two important pieces of documents for the study abroad programme assembled by their agent. Some wishy-washy minds who came to us were bothered by the pandemic while others were in discord with their parents over their study plan. In the references, we sometimes mentioned how students were coping well in the online study environment, or how they have overcome the hardship of study life alone at home and excelled. The reference letters and personal statements, in most cases, were sent via their agent to the many universities. All the students want to sit back and wait for as many offers as possible. With the help of higher education agents, mass application of postgraduate study at the time of COVID-19 is an obvious trend for our Mainland Chinese students. The reference letter containing the accolade of the student is not only used by the admission tutor to assess the applicant, but it is also integral to the semi-mass production of overseas postgraduate applications serving hundreds of thousands of Mainland Chinese students. Like humans, non-humans (e.g., reference letters, CVs, and personal statements) play influential roles of relational mediators by linking students, immediate university professors, and universities abroad (Latour, 1987; Paget, Dimanche, & Mounet, 2010).

4.2. Higher education agents, money and WeChat

Without the pandemic, Chinese students' consumption of higher education agents has been a growing trend in recent years. During the COVID-19 time, effective and efficient responses from the agent are especially demanded by the students, since they wanted to be updated on the latest COVID-news relevant to their study plan (Yang et al., 2020). A default social media platform in China, WeChat, is not only an actor that channels information, but it also allows students to make a prompt and timely decision. For instance, our respondents paid the agent fee via WeChat. In the UK study-abroad intermediary business, compared to the 2020/21 academic year, higher education agents this year have received considerably more inquiries from Chinese students and parents about how the study plan would be disrupted by pandemic uncertainties. Agents are also middlemen between university representatives and students (Yang et al., 2020). Some of our respondents were these inquirers, asking about the arrangement of course delivery and associated university policies. Certainly, no answers could satisfy the students, as the UK government just announced on April 13, 2021 that the earliest possible date for university students to return to campus is May 15, 2021, with further easing of restriction on social contact and reopening of indoor buildings (UK Parliament, 2020). One agent replied to our informant: “we all don't know the future, the only thing we can do is to get prepared.” The context of getting prepared is believed to be students having a good number of offers at hand, so they always have the opportunity to make a choice. All the agents used by our respondents have a package deal for their clients for making multiple programme applications. The agent fee is wide-ranging, depending on the size and profile of the company, and whether there is a personal relationship between the student and the company. Among the experience of our informants, the cheapest price is RMB7,000 (∼USD1,070) for seven programmes; while they mentioned that one student paid RMB30,000 (∼USD5,000) for six programmes. Making an application to more than one country involves another fee. Many students dedicate some quota to top-tier universities and leave some for lower-tier universities as “security options”. This consumption behaviour has begun for some years, but the COVID-19 has changed the mind of some of the students to increase the number of applications even further.

We have learned about two cases that are connected to the United States in a certain way. One male student's (P16) original plan was to study in the US, but he switched to the UK because he regarded the US as an ‘unsafe place’ due to COVID-19. His strategy was to apply for 10 programmes in UK universities. Another female student (P11) has already made seven UK applications when we first interviewed her. After four months, she was still anxiously waiting for her desirable offers from three top UK universities. She moaned that there are too many postgraduate applications to the UK this year. She told that she might apply for a few more programmes in the UK. This view is also circulated to one of our respondents from her agent, as the latter claimed: ‘there is still a lot of people applying to study abroad. Society needs master's students. Everybody needs it. It is so difficult to study a Master's in the US. It might add pressure to UK applicants, since people cannot go to the US’. This might be an explanation for the record-breaking UK offers received by Chinese students for the academic year 2020/2021 (The Pie News, 2020). However, for some respondents, the UK is still too risky, so they have also applied to other study destinations nearby as back-up choices. For example, one such cautious student (P2) applied for five programmes in the UK, one in Macau and one in Australia. Another student (P13) chose five universities in the UK and four in Hong Kong. While mass application among these students is not a new thing, the pandemic has exacerbated the rate of applications for the purpose of securing admission. In our study, we identify the higher education agent as a principal actor defining the process and requirements of study abroad similar to those in other tourism contexts where the government plays a major role in defining urban spaces (Chen & Wu, 2021). Mass application to postgraduate programmes and diversification of study destinations are adaptation strategies in response to the worries of uncertainty in the study plan, including health risk and increase competition of UK universities.

4.3. Chinese parents, Chinese filial relations, single-child policy

The involvement of Chinese parents in their child's study-abroad decision is predictable (Bodycott, 2009). Among the 16 interviewed students, only three of them did not mention their parents' involvement. We chose to report the decision of four students (P15, P12, P13 & P7) who have given up studying in the UK, in which their worrying parents have played a crucial role in such a big decision. One of the students, P15, will be staying in Mainland China while two others, P12 & P13, are juggling between studying in Hong Kong or taking a “gap year”. P7 has already decided to do a gap year. The COVID-19 development and the large-scale vaccination programmes in early 2021 have not given enough confidence to these Chinese parents. Considering the busy schedule of the final year students (almost all of them are doing a compulsory internship as part of our school requirement), we have decided not to burden our respondents to offer their narrative of how their family decision-making process was unfolded in the second phase's investigation. Instead, drawn from the finding from the first interview, we aim to disclose these Chinese parents' various extent of involvement in their child's study plans, which perhaps helps to understand this powerful actor in the network.

To start with an extreme case, P15 is the only respondent who wanted to stay in Mainland China while completing the UK degree through the virtual environment. Certainly, his plan might not be working out, but it appears that P15's parents made the major decision for him. P15 told us, “my parents insisted that I need to use an agent. They just don't believe my decision. They think I am childish”. P15's parents have chosen three top-tier UK universities and one Hong Kong university for him because they believe graduating from a high-ranked university is good for their son's future. But eventually, they still do not want P15 to risk studying either in the UK or Hong Kong. The story continues with P7's parents as they participated in the agent selection process and discussed with her which UK universities and programmes are suitable. Unfortunately, they did not allow their daughter to study in the UK, as P7 explains, “I am the only child in my family, so safety first”. P7 respected their decision and has decided to take a gap year.

For P12 who has long desired to study in the UK, she has to give up her plan, since her parents have decided that their daughter can only study in Asia. She always made study decisions together with her parents. She shared a scenario that her parents discussed the political issue of Hong Kong with her, explaining to her why they prefer Macau to Hong Kong. Compared to P13 & P7's parents, perhaps P12's family is more deliberative. With all these parental roles, P12 is now deciding between studying in Hong Kong or having a gap year. Unlike P12, the parents of another student (P13), wanted her to study in Macau or Hong Kong but will leave the final decision to their daughter. P13 stated that: “If it [COVID-19] is still serious, I will not go [to the UK]. I don't want them [my parents] to worry”. P13 also explained that her parents' concern was not only about the pandemic but about discrimination against Chinese people generally in the West. Their opinion confirms Ma and Zhan's (2020) observation in the United States where Chinese students were discriminated. P13 values her parents' feelings more than studying in the UK. She is juggling between Hong Kong or a gap year.

These four cases demonstrate how the filial relation shapes the decision-making process of changing the original study plan because of the pandemic (Mok et al., 2021). Parents are certainly an actor (Bodycott, 2009) who worry about the health risk, but it is the interaction among a number of human and non-human actors that conditions a decision during the pandemic (Chen & Wu, 2021; Dedeke, 2017). As explained by proponents of ANT (Callon, 1984; Latour, 1987), in the case of study abroad, if each actant plays their role and everything goes according to plan, the process of study abroad should lead to a final admission and enrolment. However, this process is fluid and changing such that a study abroad could change into a gap year due to the disruptions created by COVID-19 (Agyeiwaah et al., 2021).

4.4. Vaccination, online study, and host culture

From the perspective of decision-making of study plan in the COVID-19 era, the respondents could be categorized into three groups (see Table 1). As of April, five students (P1–P5) have insisted to keep their study plan; while three have decided to take a gap year; and seven remain undecided. Their decision-making timeline and dynamics could be different, but all of them either have undergone or are in the process of calculating the gain and loss. The dynamics of this calculation are non-linear and multi-faceted. We have analysed the students' responses and identified a few patterns of dynamics that demonstrate the interaction among actors. The large-scale vaccination has offered a sense of security to P2 and P5 to study in the UK. Having given up a bunch of UK university offers and decided to study in a safer country, Switzerland, P4 still expressed that the vaccines have made him less worried. In stark contrast, P3 has never been moved by the pandemic. Even though she dislikes online teaching, it is an inevitable trade-off. When asked what she would do if she is recommended to enrol in online learning upon arrival in her chosen school abroad, P3 stated that: “I will be disappointed. That would be just like studying in a university in China. I just want to go to the UK, I like the UK, it is like an adventure”. But she lamented that in a worst-case scenario where COVID-19 is still serious, her ‘decision will be risky - just like gambling’. When probed if online teaching is the only option to study in the UK, P3 stated that “Maybe I will do online … it is better than staying in my own home … I think it is acceptable, anyway I will be physically in the UK”.

When the above response given in December 2020 is compared with P3's written reply in April 2021, she has not changed her mind and vaccination has no role to play in her decision, as she expresses: “it is my dream since I was in primary school and at the same time, I can develop myself for better career and life”. For this student, COVID-19 itself is less undesirable than the online teaching brought about by the pandemic. These potential problems are not enough to stop her from fulfilling her long-term wish to study abroad. Likewise, P1 will join P3 to study in the UK, but her main motive is about the opportunity to experience life in the country, which is articulated in her written reply:

The vaccination programme in the UK will make me feel secured. But actually, based on British population density, Durham University's epidemic prevention and domestic vaccine were established in October last year. I am not concerned about this pandemic as I keep avoiding close contact with other people and I wear a mask all the time (P1).

P1 further explained that:

Being able to enjoy travelling in the UK is very important. I am interested in British traditional culture. And in my view, if I cannot experience British culture directly, the value of studying abroad would be reduced. The experiences include traveling in Europe, contacting local residents face-to-face, and exploring different cultures and their thinking patterns (P1).

P1's concern of the pandemic is balanced by her careful evaluation of the risk of her chosen city, but the determining force is her wish to have cross-cultural encounters in the UK. The actor, host culture, provides a ‘lived cultural experience in itself, in line with the increasingly dominant imaginaries of active and mobile’ (Cebolla-Boado et al., 2018, p. 376). This same actor has interestingly induced another thought for P8 who will have a gap year, as she explains her decision that study abroad is “more about integrating with local culture, academic atmosphere and getting along with the local people. However, the instability of the epidemic may be a big and unpredictable obstacle”. These findings indeed confirm current literature the COVID-19 is threatening study abroad among students since it disrupts the opportunity to experience different cultures through deglobalisation (Mok et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2020; Wang, 2020).

4.5. Internship and Chinese competitive study environment

For the three students (P6, P7, and P8) who have already prepared to take a gap year, as well as P13 who are still thinking about this option, they all mentioned how their internship experience plays a part in their decision. We have selected three replies to demonstrate how the pandemic has prompted students’ reflection on the value of internship in a competitive Chinese study environment.

My thoughts have changed during the internship. I think many students may have the same thoughts as me. I am not sure what to do upon graduation, so I want to continue to study. The internship changed my thoughts. The first time I decide to have one “gap year” is when I received this offer from the company as an intern. My thought also keeps developing when I worked with more departments and people … I want to say that Covid-19 played an important role in my decision. When the pandemic started, I did not think it will be such long-lasting. But when I started my internship, I have taken more things into consideration to finally decide to have one gap year (P6).

I realized that my internship experience and some English scores were not enough for me to get the offer of my ideal school. Through the gap year, I hope to gain more work experience related to marketing, enhance my professional skills and broaden my horizon in different industries. Such experience will help me to establish a more solid foundation for my future career planning (P8).

The internship (HR department) makes me think that further study is not a better choice. During the internship, my workability, learning ability (not only about the academic result), requires a long period of training. Hence, I do not need to follow most of my classmates who want to study abroad (P13)

These reflections cannot be prompted without the hard work, bodily experience, and enjoyment these students have been receiving in their internship, during the time and space co-created by the pandemic and the internship in early 2021. Talking to our students, we felt that taking a gap year during the COVID-19 time has become a normalising option. Fear of being left behind is a noticeable mentality of our students - competing for a high GPA score or gaining extra-curricular activities to enrich their CV, needless to say, their desire to get a second degree. COVID-19 has perhaps offered leeway for students to be “left behind” in an acceptable and rational matter. These gap-year students are determined to come back strong for the next academic year. The Chinese competitive study environment is a subtle actor, but it does constitute a factor to the decision of the academic environment for a year, induced by the spatial and temporal actors of internship-pandemic (Chen & Wu, 2021; Jóhannesson, 2005).

4.6. World universities ranking, competitive Chinese job market

In P8's account earlier, we have noticed another dimension in her decision to give up leaving for the UK this year. She wanted a second chance to perform better in the English language test which together with the internship she has accumulated will give her a higher possibility to go to an ideal school. In other words, the elite universities are ranked in the top 100 of the world universities' league table. This irresistible factor is evidently and explicitly found in our students' accounts in which most of them are anxiously waiting for their “dream offers”. P10 and P11 exemplify the importance of university ranking for Mainland Chinese students. For instance, P10 stated that:

I want to decorate myself with a master's degree […] so I think the university ranking is important. I promised my parents, I will go to Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) top 100 universities. This is my standard and willingness to succeed. If my university is not within the QS100 ranking, I will not go, as I am concerned about the money (P10).

P11 elaborated that:

After I have decided to study abroad, I asked my senior colleagues to give me some advice about the schools. I realised they have a similar experience with me in terms of my university choice. For example, they chose KCL and Warwick. I found that applying for G5 schools is difficult. I also want to apply to the QS top 100 (P11).

When P10 was asked what he meant by “decorate,” he explained it implies “a coat of gold.” This decoration reflects the demands of the Chinese job market which according to P11 the human resources in mainland China are obsessed with. This attitude was obtained from the respondent's close relatives who have had similar experiences. This shows the relevance of the academic ranking of universities abroad to Chinese students as many want to stay competitive. However, COVID-19 presents some disruptions to such ambitions. When we followed up with P10 in 2021, this disruption was evident:

I am still waiting for the offer from the University of Manchester. If I get the offer, I will go to study in the UK. Otherwise, I will find some ways to prove the feasibility of my entrepreneurial idea and if it works, I will delay my master's degree and work on starting a business with my friends. But, if it does not work, I will take a gap year (P10).

For P10 and P11, and some other students who have yet to make a final decision, the critical moment is whether it is an acceptance or rejection from top-tier universities. The university league table is a non-human actor that has been internalised among Chinese students. A degree holder from a Western elite university is equivalent to a competitive player in the Chinese job market, “a coat of gold” for them to distinguish themselves from other graduates from “ordinary universities”. They are deciding to study abroad next year due to COVID-19 in their pursue of an elite certificate.

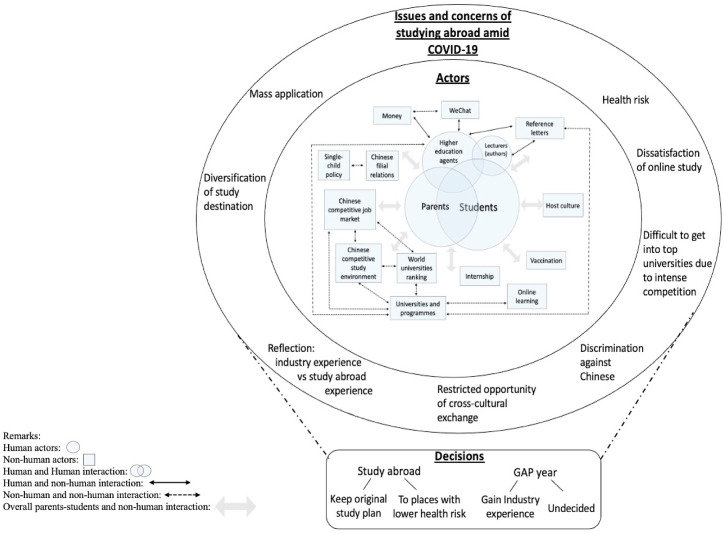

Fig. 1 summarises the issues and concerns of studying abroad amid COVID-19. It also indicates the relations between human and non-human actants as well as the resulting decision. There is a limitation of using a two-dimensional diagram to present results employing actor-network theory. The multi-dimensional inter-relations between actors could overload the diagram. To overcome this problem, we just use a set of bigger arrows to indicate that all non-human actors connect students and parents, who are often co-decision makers, according to our findings.

Fig. 1.

Actor-Network Theory of study abroad in a pandemic.

5. Theoretical implications: Actor-network theory of study abroad in a pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has interrupted the life of current and potential international students. The body of literature relevant to this subject often treats COVID issues and concerns as isolated entities. This study employed a qualitative approach to deconstructing the study abroad dynamics of Chinese students. Based on the actor-network theory, we analyze the key concerns and issues of Chinese students seeking to study abroad and the key role both human and non-human actants play in changing the final decision of a postgraduate study abroad enrolment into studying in a place with lower COVID risk or taking a gap year. We develop a novel framework to explain this complex network of relationships (Fig. 1) that is informed by the contextual finding. ANT offers a holistic framework revealing the possibility of showcasing some structural and contingent agencies. We found that the network of relations comprises not only humans but non-humans interacting and impacting each other in this network of study abroad. This approach is different from previous studies, for example, Yang et al.’s (2020) identification of two actors, namely higher educational agents and parents. Study abroad research within hospitality and tourism and the broader educational literature have treated both actants independently without delving into the participation of both actors in the success of study abroad or otherwise (e.g., Cebolla-Boado et al., 2018; Davidson & King, 2008; Thieme, 2017). This study contributes to a holistic understanding of the gamut of network relations and issues within the entity of study abroad. Specifically, unpacking each network reveals even more actants and their interactions (Chen & Wu, 2021; Jóhannesson, 2005). For example, within the educational sector, some students need reference letters to top universities recommended by educational agents. These reference letters are non-human actant but can influence admission to top universities and their absence changes the entire network. Students' contextual factors such as being a product of single child policy and the Chinese competitive job environment drive the need for highly ranked universities. The contextual factors lead many parents to take a key role in making sure their children are positioned to compete for a better job. However, these key roles are a major concern as they may force students to study close to home or take a gap year particularly in the context of COVID-19 disruption. COVID-19, though a non-human actant, is interacting with humans and other humans to influence decisions (Fig. 1). Consequently, COVID-19 possesses an agency of disrupting the study abroad process and converting the final enrolment decision into studying in a less COVID risk region or taking a gap year to gain industry experience. For some students, the pandemic year has given them a second chance to improve their language test and enrich their CV, with the hope to get into a top-ranked university in the coming year.

6. Practical implications

The preceding theoretical understanding of both networks of human and non-actors has practical implications for stakeholders within the education sector. Educational agents and study abroad institutions must provide regular and accessible information on the COVID-19 measures to facilitate decision-making and parental guidance. This is because such non-human information can influence the students' future. Moreover, overcoming the issues and concerns in the context of COVID-19 requires universities abroad to provide clear learning strategies and cultural opportunities for studying abroad during the pandemic and measures put in place to ensure students’ safety learning in the various universities. For the higher education agent sector, this research has manifested that parents are equally important, if not more influential in some cases than students in making study abroad decisions. The question for the sector is how to gather and disseminate to both parents and students very updated and relevant information about the pandemic policies released by universities and authorities. It is expected that more students will choose to delay their further study. In that situation, students could use the “pandemic year” to work in the hospitality sector to improve their C.V. From the industry perspective, how would they utilise the talents of these fresh graduates? Do they have different motivations and plans compared to their cohorts who wanted to settle in their graduate job? This research offers an implication that the industry should look into a variety of factors that have driven students to choose another pathway that appears not a popular option for most graduates.

7. Conclusion

Employing the network-actor theory, this study has portrayed a network of actors that mediate a group of Chinese students' decision to study (or not) abroad amid the COVID-19 disruptions. The interactions among the actors, in various spatial and temporal contexts, illustrate the issues and concerns of the final year students who study hospitality and tourism in Macau. The 16 students have revealed their concerns and worries, and they are calculating their gains and loss when deciding their study plans for the academic year 2021/22. This research captures such a dynamic between late 2020 to April 2021. The higher education agent sector plays an ever more important role to help students increase the number of applications and diversify their postgraduate study destination since the applicants are worried about COVID disruptions that have created intense competition in the UK. Immediate university Professors and Lecturers are perhaps in a peripheral position in influencing students' decisions, but they offer their support to the students during their COVID adversary through a non-human actor, the reference letter. Most respondents' parents are participative actors (some even being the contact person with the HE agent). Some are a decisive actor who determines whether our respondents can study abroad or not. The two non-human actors, namely the one-child policy and the Chinese filial relations, are directly connected to the parent-child interaction. The parents’ worries are also related to their evaluation of the health risk and large-scale vaccination programmes in the study destination. There are also parents feeling discomfort to hear reports on discrimination against Chinese in some countries.

It is observed that students make calculations on favourable actors (host culture experience to be gained, vaccination offering safety, and progress in the competitive Chinese study environment) and unfavourable actors (COVID health risk, and dislike of online teaching). Students are being challenged by a powerful actor – world universities ranking. They are desperately waiting for offers from top universities. In case they failed to be accepted, COVID-19 offers a refuge for them to work hard and try again next year. The worship of an elite certificate is given rise by the bonding between two actors, namely the world universities ranking and the competitive Chinese job market. Some students have undergone a reflection on their study and work, driven by their internship experience. They have already decided to take a year to gain industry experience and improve themselves. Again, without COVID-19, it could be viewed as an unconventional and bold decision.

8. Limitations and future scope

In addition to sharing these unique findings, we acknowledge some limitations of the study. First, we acknowledge the fluidity of the interactions between these actors and recognize that there could be changes in these relations as the COVID-19 pandemic mutates. Hence, further studies are warranted as a follow-up to capture new emerging concerns. Second, this study focused on Chinese students within a specific university in Macau. Hence, an extension to other universities in China is warranted as part of developing a complete actor-network theory on study abroad among Chinese students.

Authorship statement

Manuscript title: Exploring Chinese students’ issues and concerns of studying abroad amid COVID-19 pandemic: An actor-network perspective.

Please note that all authors have been listed below and they all acknowledge their contributions to this paper as presented in the table below. We all confirm that this paper has not been submitted to any journal and is not under publication in any journal. There is no conflict of interest.

Contributions of authors.

| Man Tat Cheng | Contributions include developing the theoretical work, writing up the introduction, literature review (more on how the pandemic affects Chinese students overseas), data collection, data analysis, and discussion and conclusion. |

|---|---|

| Elizabeth Agyeiwaah | Contributions include developing the theoretical work, writing up the introduction, literature review (especially paid much effort on the Actor-Network Theory), methodology, data collection, critical review of data analysis and, discussion and conclusion. |

References

- Agyeiwaah E., Adam I., Dayour F., Badu Baiden F. Perceived impacts of COVID- 19 on risk perceptions, emotions, and travel intentions: Evidence from Macau higher educational institutions. Tourism Recreation Research. 2021;46(2):195–211. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2021.1872263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beine M., Noël R., Ragot L. Determinants of the international mobility of students. Economics of Education Review. 2014;41:40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bertaux D. In: Biography and society: The life history approach in the social sciences. Bertaux D., editor. Sage; London: 1981. From the life-history approach to the transformation of sociological practice; pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bodycott P. Choosing a higher education study abroad destination: What mainland Chinese parents and students rate as important. Journal of Research in International Education. 2009;8(3):349–373. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeu P. Polity Press; United Kingdom: 2004. Science of science and reflexivity. [Google Scholar]

- British Council HE institutions face ‘battle’ for Chinese students as 39 per cent of applicants unsure about cancelling study plans. 2020. https://www.britishcouncil.org/contact/press/higher-education-chinese-students-covid-report

- Callon M. Some elements of a sociology of translation: Domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. The Sociological Review. 1984;32(1_suppl):196–233. [Google Scholar]

- Carius A.C. Network education and blended learning: Cyber University concept and Higher Education post COVID-19 pandemic. Research, Society and Development. 2020;9(10) doi: 10.33448/rsd-v9i10.9340. e8209109340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cebolla-Boado H., Hu Y., Soysal Y.N.l. Why study abroad? Sorting of Chinese students across British universities. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 2018;39(3):365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Center of Disease Control and Prevention Special webpage against epidemics. 2021. https://www.ssm.gov.mo/apps1/PreventCOVID-19/ch.aspx#clg17046

- Chen N., Dwyer L., Firth T. Factors influencing Chinese students' behavior in promoting Australia as a destination for Chinese outbound travel. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. 2015;32(4):366–381. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2014.897299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-S., Wu S.-T. An exploration of actor-network theory and social affordance for the development of a tourist attraction: A case study of a Jimmy-related theme park, Taiwan. Tourism Management. 2021;82:104206. [Google Scholar]

- Collins F.L. Bridges to learning: International student mobilities, education agencies and inter‐personal networks. Global Networks. 2008;8(4):398–417. [Google Scholar]

- Collins F.L. Regional pathways: Transnational imaginaries, infrastructures and implications of student mobility within Asia. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal. 2013;22(4):475–500. [Google Scholar]

- Cypress B.S. Rigor or reliability and validity in qualitative research: Perspectives, strategies, reconceptualization, and recommendations. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 2017;36(4):253–263. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson M.C.G., King B.E.M. The purchasing experiences of Chinese tourism and hospitality students in Australia. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Education. 2008;20(1):30–37. doi: 10.1080/10963758.2008.10696910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dedeke A.N. Creating sustainable tourism ventures in protected areas: An actor-network theory analysis. Tourism Management. 2017;61:161–172. [Google Scholar]

- van der Duim R., Ren C., Jóhannesson G.T. Ant: A decade of interfering with tourism. Annals of Tourism Research. 2017;64:139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Findlay A.M., King R., Smith F.M., Geddes A., Skeldon R. World class? An investigation of globalisation, difference and international student mobility. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 2012;37(1):118–131. [Google Scholar]

- Fong V. 1st ed. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 2011. Paradise redefined: Transnational Chinese students and the quest for flexible citizenship in the developed world. [Google Scholar]

- Fountain R.-M. Socio-scientific issues via actor network theory. Journal of Curriculum Studies. 1999;31(3):339–358. [Google Scholar]

- Ganotice F.A., Jr., Downing K., Chan B., Yip L.W. Motivation, goals for study abroad and adaptation of Mainland Chinese students in Hong Kong. Educational Studies. 2020:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Garrety K. Social worlds, actor-networks and controversy: The case of cholesterol, dietary fat and heart disease. Social Studies of Science. 1997;27(5):727–773. doi: 10.1177/030631297027005002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen A.S., Thøgersen S. The anthropology of Chinese transnational educational migration. Journal of Current Chines Affairs. 2015;44(3):3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Xu C.L., Tu M. Family-mediated migration infrastructure: Chinese international students and parents navigating (im)mobilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chinese Sociological Review. 2020:1–26. doi: 10.1080/21620555.2020.1838271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ICEF Monitor US: COVID-19 impacts include campus closures and recruiting challenges. 2020. https://monitor.icef.com/2020/03/us-covid-19-impacts-include-campus-closures-and-recruiting-challenges/

- Jóhannesson G.T. Tourism translations: Actor–network theory and tourism research. Tourist Studies. 2005;5(2):133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen M.T. Reframing tourism distribution-activity theory and actor-network theory. Tourism Management. 2017;62:312–321. [Google Scholar]

- Lan S. Youth, mobility, and the emotional burdens of youxue (travel and study): A case study of Chinese students in Italy. International Migration. 2020;58(3):163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Latour B. In: Science observed: Perspectives on the social study of science. Knorr-Cetina K., Mulkay M., editors. Sage Publications; Beverly Hills: 1983. Give Me a laboratory and I will raise the world; pp. 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Latour B. Harvard university press; 1987. Science in action: How to follow scientists and engineers through society. [Google Scholar]

- Latour B. Reassembling the social. An introduction to actor-network-theory. Journal of Economic Sociology. 2013;14(2):73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Law J. Notes on the theory of the actor-network: Ordering, strategy, and heterogeneity. Systems Practice. 1992;5(4):379–393. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.K., Sulaiman-Hill C.R., Thompson S.C. Overcoming language barriers in community-based research with refugee and migrant populations: Options for using bilingual workers. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2014;14(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-14-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y., Guba E. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- LKS Faculty of Medicine School of Public Health Cumulative statistics. 2021. https://covid19.sph.hku.hk/

- Ma H., Miller C. Trapped in a double bind: Chinese overseas student anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Communication. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1775439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall B., Cardon P., Poddar A., Fontenot R. Does sample size matter in qualitative research?: A review of qualitative interviews in IS research. Journal of Computer Information Systems. 2013;54(1):11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Zhan N. To mask or not to mask amid the COVID-19 pandemic: How Chinese students in America experience and cope with stigma. Chinese Sociological Review. 2020:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado S. International student mobility and the impact of the pandemic. 2020. https://bized.aacsb.edu/articles/2020/june/covid-19-and-the-future-of-international-student-mobility

- Mok K.H., Xiong W., Ke G., Cheung J.O.W. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on international higher education and student mobility: Student perspectives from mainland China and Hong Kong. International Journal of Educational Research. 2021;105:101718. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paget E., Dimanche F., Mounet J.-P. A tourism innovation case: An actor-network approach. Annals of Tourism Research. 2010;37(3):828–847. [Google Scholar]

- Pan S. COVID-19 and the neo-liberal paradigm in higher education: Changing landscape. Asian Education and Development Studies. 2020;10(2):322–335. doi: 10.1108/AEDS-06-2020-0129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park K., Park S., Lee T.J. Analysis of a spatial network from the perspective of actor‐network theory. International Journal of Tourism Research. 2020;22(5):653–665. [Google Scholar]

- Phellas C.N., Bloch A., Seale C. Structured methods: Interviews, questionnaires and observation. Researching Society and Culture. 2011;3(1):23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England Official UK Coronavirus dashboard. 2021. https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/cases Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK.

- Ritzer G. Vol. 1479. Blackwell Publishing; New York, NY, USA: 2007. The Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health. 1995;18(2):179–183. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra Hagedorn L., Zhang L.Y. The use of agents in recruiting Chinese undergraduates. Journal of Studies in International Education. 2010;15(2):186–202. doi: 10.1177/1028315310385460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sofaer S. Qualitative methods: What are they and why use them? Health Services Research. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1101–1118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Pie News Significant portion of Chinese students “unsure” about UK study plans. 2020. https://thepienews.com/news/uk-chinese-university-students-may-cancel-or-delay-study-plans/

- Thieme S. Educational consultants in Nepal: Professionalization of services for students who want to study abroad. Mobilities. 2017;12(2):243–258. [Google Scholar]

- UK Higher Education Statistics Agency Higher education student statistics: UK, 2018/19 - where students come from and go to study. 2020. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/16-01-2020/sb255-higher-education-student-statistics/location

- Wang T. The COVID-19 crisis and cross-cultural experience of China's international students: A possible generation of Glocalized citizens? ECNU Review of Education. 2020:1–6. [Google Scholar]