Abstract

The last two decades have been marked by devastating global challenges that threaten the international problem-solving activities of intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), which have guided global interactions for decades. They offer collective actions by member countries, but come with pressures to create and sustain integrative IGO policies implemented by all members. If these globally focused IGO policies (supranational institutions) misalign with related country-focused national policies (national institutions), an institutional schism exists. We study different levels of institutional schisms and their impact on member countries and national/international business environments. Building on institutional theory/new institutional economics and insights from political science, we conceptualize the different levels of schisms based on the strength of a member country’s national institutions and the degree of compliance with IGO-specific national and supranational institutions. The developed concept allows identifying the impact of IGOs on countries and the global business environment, which is critical for policymakers and practitioners alike.

Keywords: institutional theory, global institutions, Europe, conceptualization, institutional schisms, intergovernmental organizations

INTRODUCTION

Intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), such as the World Bank, the United Nations Council for Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the European Union (EU), or the International Monetary Fund (IMF), have guided the global political and business environment for decades. However, the last two decades have been marked with devastating global challenges that threaten IGOs, with their global problem-solving activities, and international business activities (Dau & Moore, 2020a, 2020b; Puffer et al., 2020). Spikes in global terrorism after 09/11, the global COVID-19 pandemic, and economic tumults like the great recession of 2008 led to high political, social, and economic uncertainties and a concurrent rise in protectionist policies and nationalism (Abrahms et al., 2019; Dau, Moore, & Abrahms, 2018, Dau, Moore, Barreto & Robson, 2019). To foster interdependence and solidarity among member countries (Bearce & Bondanella, 2007) and to promote development (Fausett & Volgy, 2010; Volgy et al., 2008), IGO activities continue to face extreme challenges (Nahem & Sending, 2017; Snidal, 1992) despite the benefits they bring to both global politics and the global business environment. Thus, a reassessment of IGOs and their impact on countries, governments, and business environments is needed.

The assessment is essential, as member countries willingly forego portions of their sovereignty and commit to supporting missions and objectives of the organizations (Pease, 2012; Tallberg, 2004a, 2004b), which implies that governments agree to follow the IGOs’ established policies, rules, and regulations. Especially in times of uncertainty, this loss of sovereignty is challenging for governments and policymakers. While the IGO’s policies, rules, and regulations aim to promote stability, development, and security for member countries and their citizens (Barnett & Finnemore, 2004), they also incite equal policy and regulation alignment of all (and often diverse) IGO member countries.

According to new institutional economics ala North (1990, 1991), formalized policies, rules, and regulations are defined as formal institutions. Applying this terminology to the national country and the IGO context, policies, rules, and regulations created by governments for their nation are national institutions, and those created by IGOs for their supranational collaborative members are supranational institutions. Signing and ratifying to the IGO means that member countries agree to align their national institutions with the supranational institutions of the IGO. However, national institutions related to the IGO’s specific subject can change quickly, are unique, and country dependent, and do not always align with these supranational institutions (e.g., Epstein & Rhodes, 2018), which creates a misalignment. This misalignment of the two sets of institutions has been referred to as an institutional schism (Moore, Brandl, & Dau, 2019).

An example of an institutional schism was evident in the restrictive trade policies implemented by the US against China under the Trump administration (Lai, 2019; Swanson, 2020). Both countries are part of the WTO and ratified to adhere to the trade-enhancing policies of the organization. However, the Trump administration implemented various trade restricting policies, i.e., tariffs, quotas, and bans, resulting in misalignment with WTO policies. As the example shows, institutional schisms are dynamic and can have various levels of intensity, but little is known about them, especially their impact on IGO member countries and national and international business environments. Thus, the objective of this study is to provide a conceptualization of the levels of institutional schisms and their expected impact on member countries and national/international business environments.

We theoretically ground our conceptualization in international relations and institutional theory arguments, i.e., new institutional economics (e.g., North, 1990, 1991). We use the theoretical foundation to conceptualize the existence of institutional schisms and their characteristics. There are various reasons why institutional schisms exist despite the country signing and ratifying the terms of the IGO and accepting adherence to supranational institutions. Schisms can be influenced by political uncertainty and pressures from inside and outside member countries, rapidly changing government and political perspectives, or national institutional environments that are still in flux and imbalanced (Barnett & Finnemore, 2004; Iriye, 2004).

Moreover, due to various countries and IGOs, institutional schisms have different intensities with different impacts on business environments. We argue that the level of institutional schisms is based on (1) the strength of a country’s national institutions and (2) the degree of compliance with the IGO’s related national and supranational institutions. National institutional strength is based on the national institutional environment of the country and the implementation and control of national institutions. Further, compliance captures the nature of IGOs and the degree to which member countries are following the rules and bylaws of the IGOs. To illustrate our conceptualization, we discuss institutional schisms in the European Union (EU). Specifically, we outline the impacts of the different levels of schisms on the member countries and national/international business activities. We postulate that the higher the institutional schisms level, the higher the uncertainty and mistrust in the system, resulting in more challenges for firms in these environments and a less attractive international business environment.

Our research offers several significant contributions to literature and policy. First, we provide a conceptual perspective for IB and policy scholars to understand the importance of IGOs and their impact on countries and the global business environment. This insight is essential, as IGOs are an integral part of the contemporary world order but have faced significant challenges due to the many uncertainties of recent years. If the status of IGOs is changing, for example, due to the loss of credibility or considerable non-compliance, the entire world order would be affected.

We contest that the strength of national institutions and the level of national-to-supranational institutional compliance have significant ramifications for the degree to which a country aligns, or not, with IGOs. We use arguments from international relations (e.g., Pease, 2012) to outline the relationship between IGOs and countries and their respective institutions. We theorize the impact of these supranational institutions on national institutional environments by applying new institutional economics (North, 1990, 1991), i.e., the impact of external pressures on national institutional environments. The arguments and identification of different levels of institutional schisms are novel to institutional theory and precisely institutional theory in IB (Aguilera & Grøgaard, 2019; Moore et al., 2019). Thus, it provides the IB field with a novel perspective of conflicting global institutions and their subsequent impacts on business environments.

Second, these findings also contribute to the international relations literature that has given little consideration to the impact of IGOs on the business environment and its actors. Despite the rich tradition of the international relations literature studying IGOs, namely why countries join them and what the benefits are of membership (Tallberg, 2004a, 2004b), there is a considerable gap in connecting this discussion of IGOs to IB. We thereby also provide critical insights for policymakers facing pressures, both domestically and internationally, to balance the international community and economic stability. Our theorization indicates that even for lesser developed countries that currently cannot build and maintain strong domestic institutions, there is a benefit for positive engagement with IGOs.

BACKGROUND AND THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

Intergovernmental Organizations

The international relations field in political science has long studied IGOs and their impact on the behavior of international actors (Buzan, 1993; Keohane, 1998; Keohane & Nye, 1997). This literature emphasizes the interplay between national actors and the global system in which they co-exist (Sending & Neumann, 2006). These organizations do so by facilitating collaborations between member countries (Powell, 1991; Snidal, 1992), which create networks and enhanced communication, information transfer, and transparency among members, especially when dealing with challenging global agendas (Taninchev, 2015). What distinguishes IGOs from other multilateral agreements and collaborations (e.g., free trade areas/agreements) is the free-standing established organization created and funded by member countries. The collective budget is used to fund, for example, a physical presence, offices, office equipment, salaries of administrative staff, assembly expenditures, and to support programs and initiatives that promote stability and development across all member countries. The operating budget of the World Bank was reported to be US $190 million in 2020 (World Bank, 2019), of the International Labor Organization (ILO) US $784 million in 2019 (ILO, 2019b) and of the WTO CHF 197mil in 2020 (» US $212 million) (WTO Annual Report, 2020).

To address different global problems, IGOs create global policies, rules, and regulations related to the IGO’s agenda and subject matter that transcend state borders (Boehmer & Nordstrom, 2008; Johnson, 2011). These are created to add solidarity and standardization to the supranational and intergovernmental system (Boehmer & Nordstrom, 2008). When countries sign and ratify membership to an IGO, they formally and willingly relinquish portions of their sovereignty to the IGO by promising to follow the IGO’s supranational policies, rules, and regulations (Johnson, 2011; Volgy et al., 2008). This is not to suggest that once countries join IGOs they no longer control their own decisions (Johnson, 2011; Machida, 2009), but rather that they experience immense supranational pressures that influence their policy processes and structures. The objective is to promote a global regulatory framework through shared governance and policies that align across all member countries (Johnson, 2011). Thus, it is worth reiterating that joining IGOs is an active policy choice, as is the decision to align domestic regulations. In sum, functionally, IGOs carry out concrete operations by providing a forum for coalition and knowledge sharing, increasing protection and security, and supervising the enforcement of the regulatory standards put in place, all of which motivate countries to stay in IGOs (Anderson & Reichert, 1995; Ekman, 2009; Kahler, 2013). Indeed, compliance with IGOs and international accords is a critical barrier to the functional benefits of global interdependencies (Wells & Ahmed, 2007). Normatively, they shape and define the supranational policies, rules, and regulations that members have to adhere to (Abbott, 1999; Buzan, 1993).

While these overall objectives and activities of IGOs are generally the same, each IGO has a unique focus and subject, also leading to special membership requirements (e.g., the EU requires its members to follow a democratic political system), working systems (e.g., the IMF's Managing Directors appointment process and tenure), and policies and regulations (e.g., the WTO requires the compliance with Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) regulations). This diversity is often an issue when studying IGOs, as generalization can be challenging to achieve. Despite the diversity, however, the underlying commonality of IGOs is collective problem-solving activities and cross-border interdependence. IGOs offer policy advice for members, help solve international disputes, provide legal expertise, and offer various other safeguards for complex relationships between countries (Busch, 2007; Ruggie, 1972). While some countries, such as least developed or developing countries, could potentially benefit more from IGO membership, or the upholding of international standards, than others, the summative argument by international relations scholars (e.g., Buzan, 1993) is that every member sees the potential to gain before joining.1 While IGOs are often studied in the international relations literature, focusing on how they impact countries from a political and social perspective, there has been limited attention in the IB literature to understand how they influence the global business environment (Moore et al., 2019).

National and Supranational Institutions

The institutional theory strand of new institutional economics classifies formalized and codified policies, rules, and regulations as formal institutions (North, 1990, 1991). On the country level, national governments influence these institutions by creating national institutions (national policies, rules, and regulations) to guide and direct political, social, and economic functions within their country. Depending on a variety of factors, such as social, economic, and political conditions and internal and external pressures, these national institutions differ from country to country (Williamson, 2009).

Applied to an IGO context, the policies, rules, and regulations created by IGOs for their members create supranational institutions. Signing and ratifying to the IGO means that member countries will agree to align their national institutions with the supranational institutions of the IGO. All member countries create these supranational institutions via a variety of different channels within the organizations. For example, the International Labor Organization (ILO) creates Conventions or Protocols based on international labor concerns created by a committee of member country representatives (government, employer, and worker delegates). A two-thirds majority vote of the 187 ILO constituents are needed to adopt the Convention, and once ratified and implemented, regular reports secure the enforcement, while representation and complaint procedures can be initiated against countries if enforcement is deemed unsatisfactory. There are currently 189 Conventions and six Protocols dating back as far as 1919 (ILO, 2019b).

Indeed, a structural benefit of most IGOs is that they give all member states a voice and vote in the decision-making process. However, this does not suggest that power dynamics do not come into play,2 as we describe later. While various IGOs have established enforcement and dispute systems to ensure repercussions if IGO misalignment occurs, even if no system is in place, many members still maintain their membership due to the available services of IGOs and the increase of legitimacy of member states (Lupu, 2016). Thus, the interplay between national and supranational institutions is a co-evolutionary and dynamic process that merits further attention.

INSTITUTIONAL SCHISMS

The supranational institutions of IGOs are binding for member countries that ratify and agree to follow the IGO’s policies and regulations. However, each member country’s national institutions are dependent on a variety of country internal/external factors that can influence the alignment process of the two institutions. If a country’s national institutions that relate to the IGO-specific subject misalign with supranational institutions of the IGO, an institutional schism exists (Moore et al., 2019). Each misalignment represents one institutional schism, and the country can have a variety of institutional schisms, due to its membership in multiple IGOs.

There are various reasons why institutional schisms exist despite the country signing to the IGO and ratifying its supranational institutions. While these reasons are connected, they also merit individual distinction. First, national institutions are dynamic, as governments are regularly changing in most democratic countries, leading to (sometimes even very rapid) changes in the national institutional environment of countries (Milewicz & Elsig, 2020). Although countries might have been part of IGOs for many years, political changes can challenge the willingness of countries to align with IGOs (Thompson, 2015) fully. The resulting misalignments are anticipated, known, and conceded by policymakers and the government.

An example is the US and the policies and regulations implemented during the Trump administration (2016–2020). Among other policy and regulation changes, the US applied trade measures against certain Chinese goods for various reasons that generally aligned with the administration's nationalistic economic policies, increasing political tensions. As both countries are part of the WTO, which has supranational institutions that largely restrict tariffs and duties against other IGO members, the US measures reflected misalignments of national and supranational institutions. China (and various other WTO member countries as third parties) reported these schisms to the WTO in April 2018 (case DS543), August 2018 (case DS565), and September 2019 (case DS587), claiming that the US violated several articles of the GATT 1994 agreement. The WTO dispute settlement system, specifically the panel dealing with the case, agreed with the complainants on September 2020 (WTO, 2018a, 2018b, 2019), reflecting an institutional schism related to the WTO's subject of global trade enhancements.

Second, the internal and external pressures are too intense for a government, and full compliance of national and supranational institutions is difficult to achieve even if the government and policymakers aim to do so. Internal pressures and external pressures include social movements, political forces, and lobbying efforts. These pressures are exceptionally high in less developed countries with institutional limitations, leading to institutional lethargy. Developing countries' institutions are often still forming and developing (Cuervo-Cazurra & Dau, 2009; Dau, 2013; Dau & Cuervo-Cazurra, 2014; Dau et al., 2015). Governments often struggle to form institutions while simultaneously trying to progress the country, leading to weak implementation and enforcement possibilities of institutions (Kwon, 2012; Swank, 2002). Thus, the alignment of national and supranational institutions might create imbalances between the independent national and the centralized supranational institutions (Diehl & Frederking, 2010; Drezner, 2009). For example, in March 2018, the ILO established a Commission of Inquiry to examine Venezuela’s national policies related to minimum wage, labor standards, and the protection of the right to organize. The complaint was filed in June 2015 by employer delegates at the ILO’s annual international labor conference (ILO, 2019a). The development level of Venezuela and its weak national institutions did not align with the ILOs supranational institutional requirements, creating institutional schisms on the ILO subject of labor standards and rights.

Lastly, countries facing extreme global and political uncertainty may become less compliant with IGOs over time based on contextual factors and events that change the country's political, social, and economic environments (e.g., COVID-19 or war). Thus, while global and political uncertainty may result in additional pressures, they are distinct as they are categorized as a period of intense and severe, but not permanent, difficulties. Specifically, in crises, country governments and policymakers take actions that do not always align with the IGO as they prioritize the national over the supranational context. We saw this focus in many developed countries, such as the USA, during the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine distribution. Various country governments prioritized their vaccine distribution, which countered WHO objectives and policies. The IGO called for shared and equal distributions of vaccines under the COVAX initiative and implemented related policies, such as evidence-based immunization policies (WHO, 2021). Despite this stance by the WHO, the USA and other developed countries devised their independent vaccination policies (Beaubien, 2020).

All three reasons, i.e., dynamic changes, internal/external pressures, and global/political uncertainty, can also be evident, interact, and simultaneously lead to institutional schisms in countries. For example, the concurrent political protests and civil unrests, a long history of government defaults, and many leadership changes resulting in political instability reversed Argentina’s developmental status and impacted its national institutions (Campos et al., 2012; Peréz, 2019). While Argentina is still part of various IGOs like the WTO, UN, WHO, and IMF, their compliance records to these IGOs indicate that the country has had chronic trouble with aligning national and supranational institutions with various subjects since its economic crisis in the early 2000s (Moore et al., 2019). For example, Argentina reported IMF debt of over $300 billion accumulated over years and several other violations against IMF conditions (Bloomberg, 2019). This example highlights the complexity of institutional schisms as it shows that a particular country can have multiple IGO memberships and institutional schisms and that those schisms can be caused by a variety of single or interconnected reasons.

The outlined examples are far from extensive and only provide selected simplified insights. However, they trace the complexities of institutional schisms and their dependency on the IGOs, member countries, and the dynamism of institutional changes (North, 1991). Further, they evidence and emphasize the importance of two critical dimensions of institutional schisms; (1) the strength of national institutions (country-specific factors) and (2) the degree of compliance of national institutions with the IGO’s subject-specific supranational institutions (IGO-specific factors).

Country-Specific Factors Impacting the Level of Institutional Schisms

Each country has a unique national institutional environment based on various factors and historical path dependencies, influenced by its political, social, legal, and economic systems (North, 1990). National institutions are founded on various policies covering a broad range of social, economic, legal, environmental, and political areas. While each area is important in different ways to countries and governments, each also contributes to the country's national institutions. This is an important aspect, as specific policies have long-term or short-term implications, are more critical for the country, its population, business environment, and government, or are more often changed and modified than others.

Moreover, the development level of a country plays a significant role in the degree of implementation and control of national institutions (Williamson, 2009). In highly developed countries, the performance and control of national institutions are comparably strong, while in many developing and least developed countries, institutional voids prevail (Khanna & Palepu, 1997), challenging the implementation and control of institutions (Williamson, 2009). These conditions make developing countries’ institutional environment more vulnerable to exogenous influences (Brandl et al., 2021; Williamson, 2009), such as pressures from IGOs or foreign firms and global crises (Brandl et al., 2019; Dau et al., 2020). While we generally consider country-specific national institutions, we must acknowledge that countries could also have different institutional strength levels within their borders, i.e., at different regions, areas, or cities (Goldin, 2019). All these influencing factors indicate that national institutions can change and are dynamic, but the totality of these policies is an essential indicator of the strength of the national institutional environment of a country.

In sum, national institutions are unique, context-dependent, dynamic, and offer different degrees of robust guidelines. Each of these factors plays an essential role in determining the strength of a country’s overall national institutional environment and in distinguishing the strength levels into high and low.

IGO-Specific Factors Impacting the Level of Institutional Schisms

Although governments are well aware of the required compliance when signing and ratifying to IGOs, there are still different degrees of this compliance due to the unique nature of each IGO and their supranational institutions and the reasons and objectives of participation by member countries (Szasz, 2002). The nature of IGOs and connected supranational institutions are dependent on the agenda and subject of the IGO, the power dynamics within the IGO that influence the institutions, as well as the expected and executed implementation strategy of the supranational institutions (Merlingen, 2003).

IGOs can be very broad in their subjects, leading to general supranational institutions that are easier to comply with (Simmons, 2010). IGOs with more specific subjects are more challenging to comply with, as they typically have particular compliance metrics that can challenge the enforceability of the policies (Chayes & Chayes, 1991, 1993). Moreover, depending on the agenda and the subject of the IGO, different actors have special interests in the institutions' compliance. These actors can influence the compliance with lobbying work or protest if unsatisfied with the compliance or non-compliance. Further differences are also based on the compliance and dispute systems in place if non-compliance is evident; some are stricter than others and imply more serious repercussions (Ingram et al., 2005).

Moreover, various IGOs are more prominent in the current globalized world, including countries' expectations to participate in them, while others are less prominent, resulting in fewer participation pressures (Karns et al., 2004). IGOs with 50 plus members (e.g., the WTO) have a very different agenda and organizational structure than IGOs with a few countries (e.g., Regional Center on Small Arms). While larger organizations pressure countries to participate in not being global ‘outsiders,’ they make it more challenging for countries to actively influence the development of supranational institutions (Donno, 2010). In these cases, power dynamics often plays a role in shaping the agenda of the IGOs and the construction of supranational institutions.

Despite the theoretically equal power of all members in good standing, practical global legitimacy and associated power within the IGO is still dependent on the economic and political dominance of some member countries (Bearce & Bondella, 2007; Machida, 2009) and their influence within the IGO (Shanks et al., 1996). Similarly, while all member countries pay dues that contribute to the budget of IGOs, highly developed countries often contribute more significant sums while less developed countries contribute less (Novosad & Werker, 2019). This difference has important implications for power dynamics within IGOs and influences on supranational institutions (ibid). These supranational institutions are technically standardized for all IGO member countries, but some IGOs have special requirements or concessions for specific countries, often least developed or developing countries. For example, the Trade-Related Aspect of Intellectual Property and Services (TRIPS) at the WTO allows member countries that classify themselves as developing to apply concessions that result in a variety of implementation processes (Brandl et al., 2016, Brandl, Darendeli, & Mudambi, 2018). As a consequence of these differences, there are various levels of institutional compliance of countries at different times.

In sum, the nature of IGOs and the reasons and objectives of countries to join IGOs influences the degree of compliance of the IGOs supranational institutions and the national institutions of countries that directly relate to the IGOs subject. Thus, the IGO specificity plays an essential role in determining the degree of compliance (low or high).

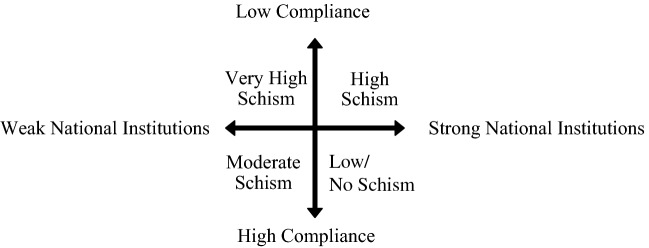

INSTITUTIONAL SCHISM LEVELS AND IB

Due to the outlined dependencies on country- and IGO-specific factors, institutional schisms are not just binary (existence or non-existence). They have different levels, ranging from a comprehensive opposition of institutions (very high institutional schism) to a high level of misalignment (high institutional schism) to moderately intense misalignment (moderate institutional schism), and minor to no divergences of institutions (low/no institutional schism) (see Figure 1). Thus, country- and IGO-specific factors can lead to a unique nexus and level of institutional schism, impacting IGO member countries and national/international business environments.

Figure 1.

Conceptualization of the level of institutional schisms.

Source author’s own

While conceptualizing the different levels of institutional schisms, we use the European Union (EU) as an example. We consider the EU an IGO with very strong regional power dynamics and participation pressures for countries geographically located within the area. Further, the international relations literature has also used the EU as a focal point when theorizing and examining IGO membership decisions and benefits (Tallberg, 2004a). We consider the subject of the EU as an economic union to mainly trade and business-related. Moreover, various IGOs utilize the EU as a benchmark or organizational goal, further supporting our use of the EU as an illustration.

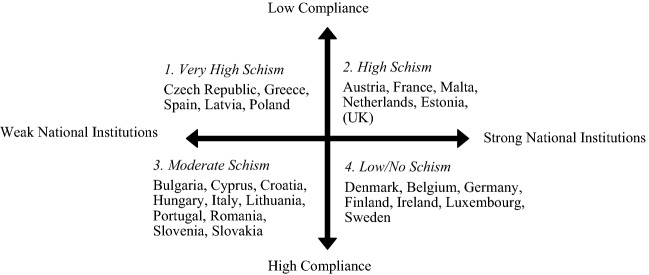

We use secondary, publicly available data to identify the different levels of institutional schisms and distinguish the national institutions and compliance of EU-related national and supranational institutions. To determine the strength of national institutions in EU member countries, we build on prior IB literature (e.g., Dau et al., 2020) that uses elements of the World Bank Governance Indicators (WBGI) dataset (WBGI, 2020b). We can distinguish EU countries into countries with strong national institutions (e.g., Denmark, Germany, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands) and weak national institutions (e.g., Cyprus, Romania, Poland, and Hungary). To identify the compliance of EU-specific national and supranational institutions, we use the European Commission’s (2020) Single Market Scoreboard (see more information in Appendix 1). The scoreboard measures the compliance of EU countries with EU regulations, infringements of member countries, violations against regulations, and the interaction and communication of member countries related to a variety of activities (e.g., legal, policing, trade of goods/services, FDI). Thus, the compliance measures allow identifying the different activities of the EU and the executed implementation strategy of the EU supranational institutions in member countries. We use the Single Market Scoreboard rankings to identify EU countries’ compliance with EU institutions, allowing us to distinguish EU members into countries with low institutional compliance (e.g., France, Italy, and Greece) and high institutional compliance (e.g., Cyprus, Lithuania, Spain, and Belgium). We provide a complete categorization of all 27 (+ 1) EU member countries in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Level of institutional schisms of EU member countries. We use measures from 2019 and thus, include the UK in this discussion before their official EU exit on January 1, 2020. In the vague of dynamic political changes, we expect some countries to change quadrant in 2020/2021, for example Hungary.

Source WB (2020b) and EU Monitor (2020)

Very High Institutional Schisms

Very high institutional schisms are evident in environments with generally low institutional compliance and weak national institutions. In these environments, there is a lack of control of national institutions, potentially due to existing institutional voids (Khanna & Palepu, 1997) or the desire of political leaders to purposefully misalign to create uncertainties, as populist leaders often do (Bronk & Jacoby, 2020). While supranational institutions could provide some guidance for the national institutional environment, compliance is low as the countries’ weak institutional environment make it challenging to implement the IGO agenda and fully commit. In these environments, the power dynamics of countries can have a strong influence, and/or the unique country context might significantly challenge the subject of the IGO. As a result, the country does not experience the benefits of IGO membership.

Moreover, dynamic political changes and the personal agenda of politicians (Hartwell & Devinney, 2021) can lead to purposeful misalignment of national and supranational institutions while remaining weak national institutions. Poland is an example of an EU country with a very high institutional schism. The country demonstrates weak national institutions due to low regulatory quality and the rule of law (60–80 percentile, WB, 2020). Moreover, out of seven indicators on the EU Commission’s Scoreboard, Poland is below average on three, scores average on two, and above average on three (EU Monitor, 2020).

In environments with very high institutional schisms, the weak national institutions of these countries have various impacts on domestic and international business activities related to the IGO subject. They indicate that locally operating firms might face more challenges due to added uncertainties and a lack of protection. However, it also allows room for institutional exploitation, at least more so than in countries that have strong national institutions. The lack of compliance indicates that the benefits of the IGOs supranational regulations (e.g., the standardization of labor laws, movement of capital, and resources across borders) are not as secure and not realized fully. It also means that these uncertainties allow for the exploitation of regulations, such as labor laws or the unregulated/less regulated movement of capital and resources. This environment is volatile and less predictable for foreign firms and, thus, is generally riskier for international business activities. While allowing various benefits, significant threats pose challenges for foreign firms’ international business activities. The preceding logic leads to the proposition:

P1: In countries with weak national institutions and low compliance between IGO-specific supranational institutions and national institutions, (a) very high institutional schisms exist which have (b) significant negative impacts on domestic and international business activities.

High Institutional Schisms

High institutional schisms are evident in countries with strong national institutions and low institutional compliance. In these environments, national institutions are well established and implemented and provide a strong institutional environment. The strength of the national institutions may influence domestic policymakers to accept low compliance with IGOs to maintain domestic sovereignty and control of institutions. Thus, the lack of compliance could be caused by time sensitivity and the lag between the signature, ratification, and full compliance with IGO agendas, by unique member requirements that might make it challenging to implement policies (Brandl et al., 2018), or, most likely, by a lack of acknowledgment of the IGO. Due to the already strong national institutions, the government could intentionally or unintentionally choose to misalign with supranational institutions to remain sovereign or accept the misalignment since they do not need the structural benefits of the IGO. France is an example of an EU member with a high institutional schism. The country demonstrates strong national institutions, with high regulatory quality and high levels of the rule of law (80–100 percentile) (WB, 2020). France also shows high non-compliance with EU policies; out of seven compliance measures of the EU Commission’s Scoreboard, France performs very poorly and below the average of EU members in five categories, performs average in one category, and above average in only two categories (EU Monitor, 2020).

In environments with high institutional schisms, business activities related to the IGO subject are somewhat challenged. Although the strong national regulations offer domestic and foreign firms some security, their misalignments with IGOs have important implications for the domestic business environment. These countries may have the capacity and power to influence the agenda of IGOs and supranational institutions, but this power also allows non-compliance with the institutions. Violations can result in fines for both the countries and the businesses in their markets. Continued violations can also result in sanctions or restrictions being put on countries, restricting international business activities. For firms looking to do business in these environments, the misalignment means that the country prioritizes its institutions over supranational ones, causing policy uncertainties and the need to understand the national institutional environment fully. These uncertainties often result in a lack of trust of foreign firms in the domestic business environment and its systems (Nye et al., 1997). Although domestic firms may experience it to a lesser degree, international firms that have to navigate various institutional environments may suffer from the competing institutional forces.

The preceding logic leads to the proposition:

P2: In countries with strong national institutions and low compliance between IGO-specific supranational institutions and national institutions, (a) high institutional schisms exist, which have (b) negative impacts on domestic and international business activities.

Moderate Institutional Schisms

Moderate institutional schisms are evident in environments with high institutional compliance and weak national institutions. In these environments, the national institutions are not well established and primarily implemented yet. Since these countries have low institutional quality, they have the most to gain from aligning with IGOs and their policies (Dau et al., 2016a, 2016b). These countries are often more willing to converge and create national institutions that align closely with supranational institutions (Fausett & Volgy, 2010; Reimann, 2006). As a result, the IGOs can help the local governments establish institutions, albeit they cannot fully support their implementation and control.

Moreover, by aligning with supranational institutions promoted by the IGOs, these countries signal the international community's readiness to relinquish their sovereignty and align with the IGOs. This conformity boosts the reputation and legitimacy of these countries. Moreover, this alignment is intended to improve these countries' security and stability, both politically and economically. Cyprus is an example of an EU country with a moderate institutional schism. The country demonstrates generally weak national institutions due to low regulatory quality and low levels of the rule of law (60–80 percentile, WB, 2020). However, it is a leader in EU policy compliance; out of seven potential categories, Cyprus is above average in six categories, average in one category, and tops the EU compliance metrics (EU Monitor, 2020).

In environments with moderate institutional schisms, weak national institutions can challenge foreign firm activities related to the IGO subject. However, the strong alignment with IGO regulations allows foreign firms to overcome some of the uncertainties created through weak national institutions because they can rely on the supranational institutions for guidance, which directly benefits international business activities. Thus, this supranational institutional alignment increases certainty and creates more transparent regulations that firms can follow. Moreover, this can help international businesses, mainly because standardized borders facilitate doing business in multiple countries. Specifically, when countries comply with EU law, firms can take advantage of the free movement of labor, goods, services, and capital, all of which facilitate international business activities. For firms looking to internationalize into a country with moderate or low schisms, the low degree of institutional misalignment makes the country a more desirable location for investments. The benefits are identifiable rules and regulations that are followed and can be used as guideposts for the firms, which provides stability and security.

The preceding logic leads to the proposition:

P3: In countries with weak national institutions and high compliance between IGO-specific supranational institutions and national institutions, (a) moderate institutional schisms exist which have (b) some negative impacts on domestic and international business activities.

Low/No Institutional Schisms

Low/No institutional schisms are evident in environments with high institutional compliance and strong national institutions. In these environments, countries have a highly developed institutional environment with strong national well-implemented and controlled national institutions. Moreover, these institutions are aligned with the supranational institutions due to the country having dominant decision-making power in the IGO (Kahler, 2013) and often set the agenda. Although they may be less willing to relinquish sovereignty to align with the supranational institutions, less or no alignment is necessary since the institutions being promoted by the IGOs are influenced by these countries in the first place and align naturally. Thus, compliance is generally high between the national agenda and the IGO agenda, and the implementation strategy is easily executable, if not already in place, when signing and ratifying to the IGO. Denmark is an example of an EU country with a low institutional schism. The country demonstrates strong national institutions, with high regulatory quality and high levels of the rule of law (80–100 percentile, WB, 2020). It also shows reasonably high compliance with EU policies; out of seven potential categories, Denmark is above average in five categories, average in two categories, and measures poorly in only one (EU Monitor, 2020).

In environments with low/no institutional schisms, the most positive institutional environment for international business related to the IGO subject can be found. These environments indicate the highest degree of synergy between the countries and the IGO’s supranational institutions. The strong national institutions and high compliance allow certainty about institutional environments for business activities. This certainty enhances the trust and security of the country and its business environment. Moreover, the compliance will enable countries and firms to realize and capture the full benefits of membership. Thus, foreign firms will have a high interest in operating under these conditions. The preceding logic leads to the proposition:

P4: In countries with strong national institutions and high compliance between IGO-specific supranational institutions and national institutions, (a) low/no institutional schisms exist, which have (b) minor/no negative impacts on domestic and international business activities.

CONCLUDING DISCUSSION

We set out to conceptualize the levels of institutional schisms, i.e., the level of misalignment of national and supranational institutions and their expected impact on IGO member countries’ national business environment and the international business environment. We argue that the level of institutional schisms is contingent on the strength of national institutions, based on the implementation and control of institutions in the country, and on the compliance of IGO-subject related national and supranational institutions, which is influenced by the nature of IGOs and the reasons and objectives of member countries joining them. We postulate that the higher the schism, the higher the uncertainty and mistrust in the system, resulting in more challenges for firms. Thus, institutional schisms generally add barriers for domestic and international business activities, emphasizing the benefits of IGOs on countries and business environments. Of course, we have to acknowledge that some firms (domestic and international) could also benefit from these uncertain environments as they use the instability of the systems to their advantage. For example, some firms may recognize the misalignment and take it as an opportunity to violate (supranational and national) regulations or find legal loopholes when defending their activities.

More specifically, we propose that very high institutional schisms exist in environments with national institutions that are too weak to implement supranational institutions. These countries are often still developing and struggle with their compliance. High institutional schisms exist in member countries with strong national institutions that come with power, which can afford them the purposeful misalignment with supranational institutions. These countries, marked with strong national institutions and often higher levels of economic development, can offset some of the potential disadvantages of non-compliance because they offer domestic stability in terms of regulations. However, while we argue that very high institutional schisms offer the most uncertainty for international business activity, the countries with high institutional schisms pose the most threat to IGOs because the power and leverage allow them to challenge the supranational institutions. Indeed, this can be seen with Brexit, which was the radical conclusion of misalignments between the UK and the EU and was influenced by the leverage of the UK to carry out leaving the IGO. Schisms are less evident in environments with high compliance, especially when institutions are also strong to secure their implementation. In weak institutional environments, the supranational institutions the country complies with support the strength of the national institutional environment, providing a more supportive and stable business environment. Thus, low and moderate levels of schisms offer more security and certainty and have, in comparison, fewer negative implications on national and international business environments.

While we study an individual IGO and the alignment/misalignment of its supranational institutions with national institutions, we need to restate that countries can be members of multiple IGOs and that IGOs have different scopes, setups, and strict rules. While countries might have institutions that misalign and create schisms with the supranational institutions of one IGO, they might align with supranational institutions of other IGOs. Considering the differing importance and power IGOs have on some countries compared to others, the different levels of institutional schisms can have diverse impacts on the business environment. To allow for a conceptualization of institutional schisms, we generalized some of the arguments. This conceptualization and related arguments can be operationalized in various ways. The distinction of the different levels of institutional schisms allows identifying institutional challenges resulting from IGO membership. Highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the importance of the World Health Organization, the need for cooperative international efforts is reinvigorated. Thus, it is essential to fully understand the impact of IGOs in the contemporary global business environment. Although we use the EU as an example, operationalization can be applied to any IGO and country context. The uniqueness of the IGO is acknowledged by the degree of compliance (IGO-specific factors), as is the country context with the consideration of national institutional strength (country-specific factors). The conceptualization can be used to map countries and identify the level of institutional schisms, which allows determining the impact IGOs have on business environments. To measure these levels, information on the formal institutional strength of a country must be captured (e.g., as exemplified by the WBGI data in our EU example), and the compliance of national and supranational institutions (e.g., illustrated in our EU example by violation/dispute recognition). At the same time, this approach is easier for IGOs with internal processes for monitoring compliance; nevertheless, it can and should be calculated for any IGO when obtaining the correct information from the organization.

Implications

These findings offer various implications for research. The research aligns with institutional theory research in IB that has traditionally focused on institutions at the national level. Combining the national and supranational institutional framework allows for a more appropriate analysis of the contemporary global business environment that international actors have increasingly influenced. This nexus is beginning to receive increased attention in the IB field (cf. Moore et al., 2021) but needs more development. The international relations field traditionally deals with the creation of institutions in the international community (Park, 2005) and an extended discussion of why and when countries join IGOs, while institutional theory considers predominantly national institutions (North, 1990, 1991). Combining a global perspective and a national-centered theory allows identifying how IGOs, i.e., international actors related to supranational institutions, impact countries and their actors, i.e., national actors related to national institutions. Thus, we identify and theorize a direct connection of supranational level activities on national level activities in the international business environment. We link the global environment and political science with the national business environment and its actors, which has been called for by various researchers (e.g., Buckley et al., 2017)

Moreover, the combination of both neighboring disciplines enables the conceptualization of institutional schisms as the misalignment of supranational and national institutions. The concept helps understand the interaction between competing governance bodies as they shape the institutions that influence business environments. Thus, we contribute to institutional theory, specifically new institutional economics (North, 1990, 1991), with insights on factors, especially country external factors, that influence national institutions and, as a result, a country's business environment. Unlike the institutional voids’ perspective, which deals with market inefficiencies within countries, schisms help us understand governance misalignments through differing global and national institutional environments, going beyond the often-chosen domestic perspective of institutions (e.g., Dau et al., 2020). This perspective is critically important as there is a heightened sense of uncertainty around the world that challenges the existing global system. Although previous research has taken a similar perspective and has focused on the impacts of IGOs on the global community (e.g., Ingram et al., 2005; McCormick & Kihl, 1979), scholars have suggested that IGOs affect the international system, as they help make sense of power structures in play (McCormick, 1980; Merlingen, 2003).

Moreover, distinguishing the different levels of schisms rather than considering them as one-dimensional allows a nuanced understanding of the impact of IGOs on business environments. This insight is essential as there appears to be an increase in non-compliance of member countries to some IGOs, such as to the WTO (see the WTO dispute settlements up to 2021, WTO, 2021). Even IGOs that are not primarily focused on business or the economy almost always indirectly impact business environments.

Our findings are valuable for practitioners and policymakers, especially now as the world faces severe global uncertainties. Understanding the role of IGOs is essential for policymakers that influence whether or not a country stays or becomes a member of an IGO and its supranational institutions. Indeed, this strategic choice of IGO membership is more pressing now than ever before. IGOs are increasing in size and scope to combat global problems that do not stop at national borders (e.g., terrorism, economic collapse, and health pandemics like COVID-19). While it may seem straightforward for governments to join IGOs and enjoy the benefits of collaborative problem solving, the decision is complicated. Policymakers have to worry about the issues of sovereignty when joining or the efficacy of IGO membership; we conceptually show that different levels of institutional schisms can also create challenges for the member country. The higher the institutional schisms, the more negative is the effect on the business environment. Thus, policymakers are encouraged to understand the impact of institutional schisms and act accordingly. Our conceptualization argues that low/no levels of institutional schisms result in a business environment that best supports local and international business activities. With the alignment of national and supranational institutions, policymakers have the opportunity to provide the best possible business environment for their country. While this argument applies to all countries, it is essential for lesser economically developed countries. Their policymakers are tasked with improving economic conditions, stimulating economic growth, and providing local and foreign businesses stability.

To align their national policies with supranational institutions as best as possible, policymakers need to understand them and their objectives fully. With the wide variety of IGOs and their unique regulations, this might be challenging, specifically when countries are members of multiple IGOs. To support this alignment, IGOs provide support systems to members that need assistance. These support systems are based on collaborative actions of members and allow policymakers to fall back on a source of experience, knowledge, and support programs, i.e., educational and training platforms aimed at helping policymakers understand the functional benefits of membership. IGOs also provide support through summits, regular meetings, and transparency. These support systems help disseminate information and allow policymakers and country delegates to make collective and collaborative decisions.

Moreover, to align institutions, policymakers have to convince the country’s population of their benefits. This is no easy task in the ages of nationalism and populism; during crises, when IGOs are needed the most, policymakers often face challenges in conveying the benefits of IGOs to convince their constituents. The collaborative and social focus of IGOs is at the heart of this discourse and is strongly dependent on the induvial policymakers’ leadership (Hartwell & Devinney, 2021). Thus, to promote alignment even in crises, policymakers have the added responsibility of transparency and information sharing; for example, decisions made at global summits or IGO meetings are often not effectively communicated to the general public. To help bolster support for institutional alignment, policymakers should be as transparent and informative as possible.

The alignment allows certainty for the business environments related to the IGO subject. If compliance is low, the only way to overcome the challenges is through strong national institutions. However, it is essential to remember that policy construction is an active and iterative process in which institutions are dynamic and ever-changing, and individuals have agency (Hartwell & Devinney, 2021). Countries with very high institutional schisms may behoove these countries to increase compliance and actively engage with IGOs to reap membership benefits. IGOs, like the EU, can offer institutional supports, collaborative networks, and interdependencies. Over time and with increased engagement, these countries may enjoy the functional benefits of compliance and improve their domestic institutions through policy transfer (Moore et al., 2020; Stone, 2012).

Business actors need to understand the impact of institutional schisms on their activities and the environment of operation. We provide insights on the expected outcomes of IGO involvement on business environments. For example, we theorize that the lowest levels of institutional schisms cultivate the most positive environment for domestic and international firms. These countries offer domestic regulatory stability and facilitate the full advantage of the benefits of IGO membership (e.g., cross-border flows of people, products, and capital, information sharing, increased security, and peace). Conversely, countries with the highest levels of institutional schisms not only offer a challenging domestic environment but also do not allow firms to utilize the potential benefits of IGOs that might offset these challenges.

Thus, managers need to understand the implications of institutional schisms and act accordingly. From a market strategy perspective, firms need to understand how to navigate and exploit institutional schisms if operating in such environments. To this end, firms need to be attuned to the social and political movements and changes within countries to try and forecast whether or not the country they are operating in is likely to align with the IGOs or not. Since schisms are dynamic, managers must be aware of changes to the administration. However, there are also non-market perspectives to consider as firms can and do influence policy. We suggest that firms can play two critical roles. First, MNEs can push for global standards to influence and shape policy. By signaling compliance to global initiatives and signing onto international protocols, MNEs can signal to various stakeholders (including home and host country governments) that there is a need for global regulation. This can put pressure on governments and policymakers to better align with supranational institutions. Additionally, MNEs can serve as active policy advocates within the countries they operate in to influence policymakers to align with global standards and organizations. Although not all MNEs will have the same influence, managers who are actively interested in promoting global standardization and cooperation can engage in lobbying and coalition building.

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations can be identified and built upon in future research. While we discuss the importance of IGOs and how their supranational institutions impact member countries and business activities, we do not (and cannot) discuss their future existence and, thus, refrain from any speculations on their future. However, we hope that our research sparks interest in further research on the connection of IGOs and (international) business. Similarly, we acknowledge various additional IGO related limitations: we are not able to discuss, in detail, the legitimacy of IGOs and perceive them to be equally legitimate; we only restrictedly acknowledge that it may be more critical for a country to align with some IGOs than others and that they also can falsely align (see Siegel, 2005 for a firm comparison on this topic); and we do not acknowledge potentially conflicting or competing IGOs, a scenario which may arise when a state is a member of multiple IGOs with potentially divergent interests. Thus, we are aware that our view is limited and only allows restricted insights but argue that our conceptualization permits enough room to acknowledge the uniqueness of each IGO and, with it, the complexity of legitimacy and importance. This is primarily an important point in countries, which are members of multiple IGOs. A different institutional theory strand that focuses on institutional legitimacy would allow such a perspective and provide further insights.

We only use narrative examples to illustrate our conceptually derived concepts and arguments and encourage future research to test and measure these. We strongly urge scholars to analyze and test different levels of institutional schisms to enhance IB scholarship. We consider the notion of institutional schisms significant for the IB field and other disciplines, as it allows identifying supranational impacts on countries and their business environments. Future research could expand upon the measures of IGO involvement by attempting to assess the depth and weight of this involvement and by applying research methods that allow a more descriptive identification of different levels of institutional schisms. Our derived propositions could be a starting point for this discussion. Our conceptualization provides a template for how to measure institutional schisms. In particular, we outline the need to measure both compliances with IGO regulations and domestic institutional strength. We demonstrate how to carry this out within the EU.

However, future scholars can, and we hope they do, follow this process for multiple IGOs. Detecting compliance records of IGOs might be easier for some organizations than for others, as records may not be readily accessible. Nonetheless, together with the formal regulatory strength of countries, which could be gained from the WBGI, it is possible to measure institutional schisms across IGOs or countries. Researchers, for example, could focus on one country by looking at the country’s regulatory quality and IGO membership and compliance over time. Further, although assigning weights to different IGOs and considering power would be challenging, it is possible with follow up work; doing so would add significant value as weighted IGO measures could then be used to develop testable hypotheses to examine the severity of schisms on countries and how different intensity levels of schisms impact firm-level strategy, behavior, and performance. We hope that future scholarship sees this research as a call for follow-up studies looking at institutional schisms and their impact on the global business environment.

Finally, we focus on the alignment of one IGO and its supranational institutions with the national institutions of a country, rather than an accumulated perspective of all IGOs, and emphasize the categorical level of this schism. Thereby, we acknowledge that the distinction and categorization of levels of institutional schisms into very high, high, moderate and low/no schisms mandates future scholarly efforts. Currently, we do not fully recognize the compliance across multiple IGOs that have different amounts of global power. Like many academic frameworks, we balance generalizability and applicability of the concept for future scholarship. While we believe our work provides a critical foundation in understanding how to categorically measure institutional schisms with one IGO, we recognize and hope future researchers continue to build on our concept with additional theoretical and methodological specifications on the concept of institutional schisms.

Notes

We recognize that there are three major paradigms within the IR literature that typically debate IGOs and that each of these paradigms may offer a different explanation as to why countries join IGOs. While this discussion falls outside of the scope of our research, we recognize that other scholars may find these differences useful in future research.

While we acknowledge the importance of power dynamics for IGOs and theorize about the role power plays in shaping supranational institutions, the full extent of the discussion of power falls beyond the scope of this paper and has a rich history in the international relations literature.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the editors Timothy Devinney and Sarianna Lundan, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their supportive feedback on this article. We are also very grateful for the support of Bettina Álvarez Canelón, Alyssa Cecchetelli, Denisse Jiménez, Ania Palka Dau, Larissa Marchiori Pacheco, Karen Moore, Gary Moore, and various conference and seminar participants. We are also grateful for the financial support of Northeastern University’s Global Resilience Institute, Center for Emerging Markets, and DiCenso Professorship; University of Reading Henley Business School’s Dunning Visiting Fellowship; and University of Leeds Business School’s Buckley Visiting Fellowship.

Biographies

Elizabeth M. Moore

is an Assistant Teaching Professor of International Business & Strategy at the D’Amore-McKim School of Business, Northeastern University. Her research, which has won numerous awards at top management and business conferences, focuses on formal and informal entrepreneurship, corporate social responsibility, institutional changes, institutional disruptions, transnational institutions, pro-market reforms, firm performance, emerging market firms, global strategy, and international organizations.

Kristin Brandl

is an Associate Professor of International Business at the Gustavson School of Business, University of Victoria. Her research focuses on the nexus of institutional environments and business activities, predominantly in emerging economies and on service management and value chains. She is a fellow of the Center for Global Studies, University of Victoria.

Luis Alfonso Dau

is an Associate Professor of International Business and Strategy and the Robert and Denise DiCenso Professor at Northeastern University. His research focuses on the effects of institutional processes and changes on the strategy and performance of emerging market firms. He is also a Dunning Visiting Fellow at University of Reading and a Buckley Visiting Fellow at the University of Leeds.

Appendix 1

European Commission Single Market Scoreboard

Performance indicators

Transposition consists of the conversion of EU institutions into the national institutions of member countries. Monitoring transposition ensures their proper implementation by revealing transposition deficits (difference between directives adopted by EU and directives transposed by members) and conformity deficits (incorrectly transposed directives). Overall transposition performance is calculated based on scores for five indicators: [1] Transposition deficit (% of all directives not transposed, [2] Change in number of non-transposed directives over the last 12 months, [3] Long-overdue directives (2 + years), [4] Total transposition delay (in months) for overdue directives, [5] Conformity deficit (% of all directives transposed incorrectly).

Infringement procedures are initiated when member countries fail to implement EU law and the Commission takes legal action against them. Monitoring infringements helps to ensure that members continue to properly implement the Single Market law to achieve their goals. Overall performance for infringements is based on the sum of the four indicators: [1] Number of pending infringement procedures, [2] Change in the number of infringement cases over the last 12 months, [3] Duration of infringement proceedings (in months), [4] Duration since Court’s ruling (in months).

The EU Pilot facilitates informal communication between the Commission and member countries regarding potential non-compliance with EU law before formal infringement procedures are initiated. Performance is based solely on the average time taken for each member to respond to queries checked against a 70-day time limit.

The International Market System (IMI) is a platform for national, regional, and local authorities across the EU to communicate with each other and to get access to information and other services. Overall performance of the IMI is based on the following five indicators: [1] Speed in accepting requests (% accepted within 7 days), [2] Speed in answering requests (average number of days taken to answer), [3] Requests answered by the date agreed in IMI (%), [4] Timeliness of replies as rated by counterpart (% of negative evaluations), [5] Efforts made as rated by counterparts (% of negative evaluations).

eCertis is a reference database used by parties participating in procurement procedures or contract bids. It supports bidders and buyers by providing information on what evidence and documents are required from both sides and any other information needed. Overall performance is based on two indicators with two sub-indicators as follows: [1] Criteria completeness (% of criteria set at EU level recorded in eCertis for each country), [2] Evidence recorded (# of items of evidence).

EURES is a website for Europe-wide job searches and recruitment opportunities with offered support from advisors. Its main goal is to facilitate the free movement of workers. Overall performance is based on the five following indicators: [1] Compliance with the EURES Performance Measurement System (%), [2] IT compliance for the EURES Portal, [3] Labor market share (%), [4] User satisfaction with EURES services, [5] Job placement vs. labor mobility.

Your Europe is an online portal providing information to those moving to or doing business in the EU. It contains two separate sections for Citizens and for Business and has content provided by EU institutions and national governments. Overall performance is based on the three following indicators: [1] Answers received by the Editorial Board from their national administration to requests for information for Your Europe, [2] Attendance at two Editorial Board meetings during the reporting period, [3] Traffic from government pages to Your Europe and promotional activity requested by members of the Editorial Board.

SOLVIT is provided by national administrations and offers faster and less formal methods of solving issues arising from incorrectly applied EU legislation by public authorities in other Member States. It is used by citizens and business whose rights have been compromised. Overall performance is based on the following seven indicators: [1] Home center sending an initial reply within the 7-day target, [2] Home center submitting case to lead center within 30-day target, [3] Home center accepting a proposed solution within 7-day target, [4] Home center not accepting a complaint within 30-day target, [5] Lead center accepting a case within 7-day target, [6] Lead center handling a case within 10-week target, [7] Lead center resolution time.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Accepted by Timothy Devinney, Consulting Editor, 6 August 2021. This article has been with the authors for two revisions.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth M. Moore, Email: e.moore@northeastern.edu

Kristin Brandl, Email: kbrandl@uvic.ca.

Luis Alfonso Dau, Email: l.dau@northeastern.edu.

REFERENCES

- Abbott K. International relations theory, international law, and the regime governing atrocities in internal conflicts. American Journal of International Law. 1999;931:361–380. doi: 10.2307/2997995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahms M, Dau LA, Moore EM. Terrorism and corporate social responsibility: Testing the impact of attacks on CSR behavior. Journal of International Business Policy. 2019;23:237–257. doi: 10.1057/s42214-019-00029-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera RV, Grøgaard B. The dubious role of institutions in international business: A road forward. Journal of International Business Studies. 2019;501:20–35. doi: 10.1057/s41267-018-0201-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C. J., & Reichert, M. S. 1995. Economic benefits and support for membership in the EU: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Public Policy, 231–249.

- Barnett M, Finnemore M. Rules for the world: International organizations in world politics. 1. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bearce DH, Bondanella S. Intergovernmental organizations, socialization and member-state interest convergence. International Organization. 2007;614:703–733. [Google Scholar]

- Beaubien, J. 2020. President Trump Announces that the U.S. Will Leave WHO. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2020/05/29/865685798/president-trump-announces-that-u-s-will-leave-who

- Bloomberg. 2019. One Country Nine-Defaults.https://www.bloomberg.com/news/photo-essays/2019-09-11/one-country-eight-defaults-the-argentine-debacles

- Boehmer C, Nordstrom T. Intergovernmental organization memberships: Examining political community and the attributes of international organizations. International Interactions. 2008;343:282–309. doi: 10.1080/03050620802495000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandl K, Darendeli I, Hamilton RD, Mudambi R. Impact of international business. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2016. The impact of actors and the aspect of time in institutional change processes in a developing country context; pp. 62–76. [Google Scholar]

- Brandl K, Darendeli I, Mudambi R. Foreign actors and intellectual property protection regulations in developing countries. Journal of International Business Studies. 2019;550:826–846. doi: 10.1057/s41267-018-0172-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandl K, Moore E, Meyer C, Doh J. The impact of multinational enterprises on community informal institutions and rural poverty. Journal of International Business Studies. 2021;2021:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bronk, R., & Jacoby, W. 2020 The Epistemics of Populism and the Politics of Uncertainty February 17, 2020. LSE ‘Europe in Question’ Discussion Paper Series, LEQS Paper No. 152/2020 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3539587 or 10.2139/ssrn.3539587

- Buckley PJ, Doh JP, Benischke MH. Towards a renaissance in international business research? Big questions, grand challenges, and the future of IB scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies. 2017;489:1045–1064. doi: 10.1057/s41267-017-0102-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Busch ML. Overlapping institutions, forum shopping, and dispute settlement in international trade. International Organization. 2007;614:735–761. [Google Scholar]

- Buzan B. From international system to international society: Structural realism and regime theory meet the English school. International Organization. 1993;473:327–352. doi: 10.1017/S0020818300027983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campos NF, Karanasos MG, Tan B. Two to tangle: Financial development, political instability and economic growth in Argentina. Journal of Banking & Finance. 2012;361:290–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2011.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chayes A, Chayes AH. Compliance without enforcement: State behavior under regulatory treaties. Negotiation Journal. 1991;73:311–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1571-9979.1991.tb00625.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chayes A, Chayes AH. On compliance. International Organization. 1993;47:175–205. doi: 10.1017/S0020818300027910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo-Cazurra A, Dau LA. Promarket reforms and firm profitability in developing countries. Academy of Management Journal. 2009;526:1348–1368. doi: 10.5465/amj.2009.47085192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dau, L.D., & Moore, E.M. 2020b. Local business recovery and resilience in New England: Response to COVID-19. FEMA White Paper.

- Dau, L.D., & Moore, E.M. 2020a. A global disruption requires a global response: Policies for building international business resilience for this and future pandemics. FEMA White Paper.

- Dau LA. Learning across geographic space: Pro-market reforms, multinationalization strategy, and profitability. Journal of International Business Studies. 2013;443:235–262. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2013.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dau LA, Cuervo-Cazurra A. To formalize or not to formalize: Entrepreneurship and pro-market institutions. Journal of Business Venturing. 2014;295:668–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dau LA, Moore EM, Abrahms M. Global security risks, emerging markets and firm responses: Assessing the impact of terrorism. In: Castellani D, Narula R, Nguyen QT, Surdu I, Walker JT, editors. Contemporary issues in international business. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; 2018. pp. 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Dau LA, Moore EM, Barreto AA, Robson MA. Economic nationalism and international business. In: Chandan HC, Christiansen B, editors. International firms’ economic nationalism and trade policies in the globalization era. Hershey: IGI Global; 2019. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dau LA, Moore EM, Bradley C. Institutions and international entrepreneurship. International Business: Research, Teaching and Practice. 2015;91:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dau LA, Moore EM, Kostova T. The impact of market based institutional reforms on firm strategy and performance: Review and extension. Journal of World Business. 2020;554:101073. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2020.101073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dau LA, Moore EM, Soto M. Lessons from the great recession: At the crossroads of sustainability and recovery. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2016. The great recession and emerging market firms: Unpacking the divide between Global and National Level Sustainability Expectations; pp. 165–187. [Google Scholar]

- Dau LA, Moore EM, Soto M, LeBlanc C. How globalization sparked entrepreneurship in the developing world: The impact of formal economic and political linkages. In: Christiansen B, editor. Corporate espionage, geopolitics, and diplomacy issues in international business. 1. Hershey: IGI Global; 2016. pp. 72–91. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl P, Frederking B. The politics of global governance: International organizations in an interdependent world. 4. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishing Co.; 2010. [Google Scholar]