Abstract

The Korean Intermittent Exotropia Multicenter Study (KIEMS), which was initiated by the Korean Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, is a collaborative multicenter study on intermittent exotropia in Korea. The KIEMS was designed to provide comprehensive information, including subjective and objective findings of intermittent exotropia in a large study population. A total of 65 strabismus specialists in 53 institutions contributed to this study, which, to date, is one of the largest clinical studies on intermittent exotropia. In this article, we provide a detailed methodology of the KIEMS to help future investigations that may use the KIEMS data.

Keywords: Intermittent exotropia, Korean Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, Korean Intermittent Exotropia Multicenter Study, Methods, Multicenter study

Introduction

The Korean Intermittent Exotropia Multicenter Study (KIEMS), which was initiated by the Korean Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, is a nationwide, cross-sectional study to investigate intermittent exotropia in Korea. Intermittent exotropia is the most common form of strabismus in pediatric populations in Korea [1,2] and in several other Asian countries [3–6]. It is a clinical entity that shows diverse and variable clinical characteristics. There have been numerous studies that described clinical characteristics of intermittent exotropia, but the findings of those studies were insufficient in providing comprehensive information about the condition due to relatively small sample sizes, a lack of detailed questions on disease history or observations in daily life, and inadequate investigative methods and parameters. This study aimed to describe overall symptomatologic information and clinical features of intermittent exotropia in a large population of Korea.

KIEMS Overview

Study summary

This study was a retrospective, observational, cross-sectional, and multicenter study. The participants were recruited from March 1, 2019 to February 29, 2020 by 65 strabismus specialists in 53 institutions, of which secondary or tertiary referral centers accounted for 98.1%, in Korea. This study protocol conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of each institution. Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. Questionnaires and examination forms were pre–distributed to the investigators for the standardization of collected data. Each investigator collected the questionnaires and examination forms from every first visited intermittent exotropia patient. The data collection was conducted in accordance with the Personal Information Protection Act. After private information in the questionnaires and examination forms were anonymized and encrypted (e.g., intended deletion of some privacy information to keep reproducing prior to data collection), the questionnaires and examination forms were collected by the KIEMS committee and were handled centrally.

Inclusion criteria

This study included patients diagnosed with 8 prism diopters or more exodeviation at distant or near fixation, regardless of age or fusion control (including exophoria, intermittent exotropia, and constant exotropia). We excluded patients with congenital ocular anomalies or ocular myopathies. Patients with limitation of ocular motility resulting in incomitant strabismus, including neurologic or paralytic disorders, previous ocular surgical history, including strabismus and visually affecting surgeries, or any conditions affecting the central visual acuity, including anterior segment abnormality, cataracts, retinal diseases, or blepharoptosis (ocular sensory disorders), were excluded. When a patient was suspected to visit multiple institutions, only the first reported data were used to avoid redundancy.

Questionnaires

This study collected disease-related information from patients or their guardians using questionnaires. The questions were as follows: the reason for visiting the specialist; the first person who noticed associated symptoms; onset of symptoms; frequency of manifested exotropia noticed per day; guardian’s recognition of the exotropia manifestations (direction of deviation and ocular dominance) [7]; associated symptoms (abnormal head posture, photophobia, glare, reading difficulty, headache, ocular pain, micropsia, or blurring) [8–10]; frequency of diplopia (at distant or near viewing conditions) [11]; history of occlusion therapy (duration, frequency, and laterality); history of wearing glasses; systemic diseases; history of developmental delay; childbirth history (type of delivery, gestational age, and birth weight) [12]; perinatal medical conditions (birth complications); and history of exotropia in parents and siblings (including a history of strabismus surgery history) [12]. Questionnaires were constructed as a combination of open-ended and multiple-choice questions. An English version of the questionnaire was provided in Supplement 1.

Ophthalmic exams

Ophthalmic exams were done by the investigators according to pre-distributed standardized guidelines and formats. The ophthalmic exams included best corrected visual acuity and cycloplegic refraction data. Strabismus angles were measured at distant (6 m) and near fixation (33 cm) in primary, right-, left-, up-, and down-gaze, and right and left head-tilted position using alternate prism and cover test. If the exotropic angle at distant fixation measured 10 prism diopters or more than at near fixation, exotropic angles at distant and near fixation in the primary position were remeasured after one eye was covered with a patch for 30 minutes to 1 hour (occlusion test of Scobee-Burian) [13]. After the occlusion test, the +3.00 diopter spherical lens test was followed to measure accommodative convergence/accommodation ratio at near fixation [13]. Superior and inferior oblique muscle functions were graded as +1 to +4 for overaction and -1 to -4 for underaction based on the standard photographs [14]. Fusion control was measured both at distant and near fixation, and were graded as “good”, “fair”, or “poor” [14]. Ocular dominance was also assessed at distant and near fixation conditions. For assessing binocular sensory status, Worth four-dot test was done at 6 m of distance, and either Titmus stereotest or random-dot stereograms was done at 40 cm of distance [15]. To investigate the variability of treatment plans among the investigators, investigators were asked to select desirable treatment plans (surgery methods, prescription of glasses, occlusion therapy, or observation plans) for a specific patient. An English version of examination form was provided in Supplement 2.

Study populations

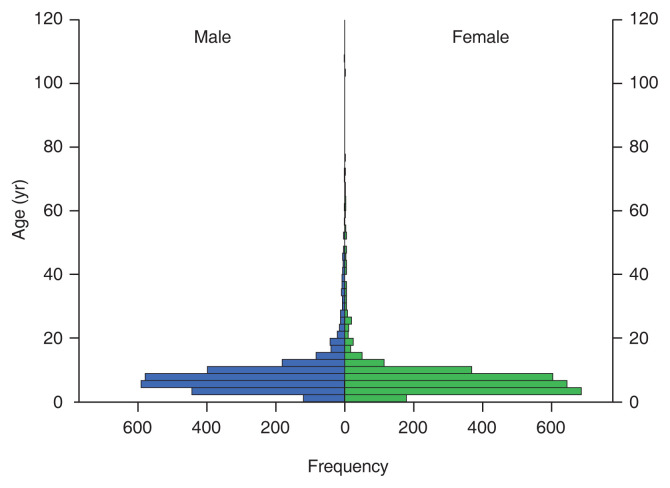

A total of 5,837 cases were collected. The cases missing essential information (individual-identifying information or deviation angle in primary position, 156 cases) or suspected to be redundant (suspected to visit two or more institutions collecting individual-identifying information, 296 cases) were excluded during the review process by the KIEMS committee. The remaining 5,385 cases were included for comprehensive analysis. Male and female participants were 2,592 (48.1%) and 2,793 cases (51.9%), respectively, showing female preponderance, which was similar to a previous study [16]. The mean age of all the included participants was 8.2 ± 7.6 years (mean ± standard deviation). The mean age of the male participants was 8.6 ± 7.3 years, which was higher than that of female participants (7.8 ± 7.8 years) (independent t-test, p < 0.001). Ninety-five percent of the subjects were under 19 years of age, which meant most patients with intermittent exotropia were diagnosed in their childhood, similar with the findings of a previously reported study [17] population-based cohort. PARTICIPANTS: All pediatric (<19 years old. The age distribution of the subjects is depicted in Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Study population pyramids. Most of the study participants were in their 1st or 2nd decade of life. The female participants were found to be younger than the male subjects (p < 0.001, independent t-test).

Table 1.

Distribution of study population according to age and sex

| Age (yr) | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 5 | 689 (40.5) | 1,014 (59.5) | 1,703 |

| 5 to <10 | 1,298 (49.4) | 1,330 (50.6) | 2,628 |

| 10 to <15 | 380 (58.1) | 274 (41.9) | 654 |

| 15 to <20 | 97 (61.8) | 60 (38.2) | 157 |

| 20 to <40 | 99 (58.6) | 70 (41.4) | 169 |

| 40 to <60 | 24 (44.4) | 30 (55.6) | 54 |

| 60 or more | 5 (25.0) | 15 (75.0) | 20 |

| Total | 2,592 (48.1) | 2,793 (51.9) | 5,385 |

Values are presented as number (%) or number.

Conclusion

The KIEMS study is one of the largest clinical studies on intermittent exotropia ever conducted. The study was conducted by experienced strabismus specialists in multiple institutions in Korea, with pre-planned and standardized study protocols. The questionnaires and investigating items covered almost all symptoms and characteristics ever described or reported in intermittent exotropia. Therefore, the KIEMS study can provide objective, detailed, and standardized information about symptomatology and clinical features of intermittent exotropia in Korea. This article can explain the detailed methodology for future research using the KIEMS data.

Acknowledgements

The KIEMS study was initiated and financially supported by the Korean Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental materials are available from: https://doi.org/10.3341/kjo.2021.0097.

Questionnaire form

Examination form

References

- 1.Choi KW, Koo BS, Lee HY. Preschool vision screening in Korea: results in 2003. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2006;47:112–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han KE, Baek SH, Kim SH, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of strabismus in children and adolescents in South Korea: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2008–2011. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuo T, Matsuo C. The prevalence of strabismus and amblyopia in Japanese elementary school children. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2005;12:31–6. doi: 10.1080/09286580490907805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chia A, Dirani M, Chan YH, et al. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in young Singaporean Chinese children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:3411–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan CW, Zhu H, Yu JJ, et al. Epidemiology of intermittent exotropia in preschool children in China. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93:57–62. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goseki T, Ishikawa H. The prevalence and types of strabismus, and average of stereopsis in Japanese adults. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2017;61:280–5. doi: 10.1007/s10384-017-0505-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han KE, Lim KH. Discrepancies between parental reports and clinical diagnoses of strabismus in Korean children. J AAPOS. 2012;16:511–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campos EC, Cipolli C. Binocularity and photophobia in intermittent exotropia. Percept Mot Skills. 1992;74(3 Pt 2):1168–70. doi: 10.2466/pms.1992.74.3c.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirota M, Kanda H, Endo T, et al. Relationship between reading performance and saccadic disconjugacy in patients with convergence insufficiency type intermittent exotropia. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2016;60:326–32. doi: 10.1007/s10384-016-0444-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirota M, Kanda H, Endo T, et al. Binocular coordination and reading performance during smartphone reading in intermittent exotropia. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:2069–78. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S177899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang FM, Chryssanthou G. Monocular eye closure in intermittent exotropia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:941–2. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060140087030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maconachie GD, Gottlob I, McLean RJ. Risk factors and genetics in common comitant strabismus: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:1179–86. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kushner BJ, Morton GV. Distance/near differences in intermittent exotropia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:478–86. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenbaum AL, Santiago AP. Clinical strabismus management: principles and surgical techniques. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1999. pp. 17–165. [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Noorden GK, Campos EC. Examination of the patient V. In: von Noorden GK, Campos EC, editors. Binocular vision and ocular motility. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002. pp. 298–307. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nusz KJ, Mohney BG, Diehl NN. Female predominance in intermittent exotropia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:546–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Govindan M, Mohney BG, Diehl NN, Burke JP. Incidence and types of childhood exotropia: a population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:104–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Questionnaire form

Examination form