Abstract

Background

Interprofessional communication (IPC) is integral to interprofessional teams working in the emergency medicine (EM) setting. Yet, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has laid bare gaps in IPC knowledge, skills and attitudes. These experiences underscore the need to review how IPC is taught in EM.

Purpose

A systematic scoping review is proposed to scrutinize accounts of IPC programs in EM.

Methods

Krishna's Systematic Evidence-Based Approach (SEBA) is adopted to guide this systematic scoping review. Independent searches of ninedatabases (PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, PsycINFO, ERIC, JSTOR, Google Scholar and OpenGrey) and “negotiated consensual validation” were used to identify articles published between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2020. Three research teams reviewed the data using concurrent content and thematic analysis and independently summarized the included articles. The findings were scrutinized using SEBA's jigsaw perspective and funneling approach to provide a more holistic picture of the data.

Results

In total

18,809 titles and abstracts were identified after removal of duplicates, 76 full-text articles reviewed, and 19 full-text articles were analyzed. In total, four themes and categories were identified, namely: (a) indications and outcomes, (2) curriculum and assessment methods, (3) barriers, and (4) enablers.

Conclusion

IPC training in EM should be longitudinal, competency- and stage-based, underlining the need for effective oversight by the host organization. It also suggests a role for portfolios and the importance of continuing support for physicians in EM as they hone their IPC skills.

Highlights

• IPC training in EM is competency-based and organized around stages.

• IPC competencies build on prevailing knowledge and skills.

• Longitudinal support and holistic oversight necessitates a central role for the host organization.

• Longitudinal, robust, and adaptable assessment tools in the EM setting are necessary and may be supplemented by portfolio use.

Keywords: emergency medicine, interprofessional, communication, medical education

Introduction

Interprofessional communication (IPC) is defined as the “sharing of information among members of different health care professionals to influence patient care positively” - highlighting the role of effective communication and collaboration within teams of health care professionals including physicians, nurses, technicians, administrative staff, and community service providers. 1 IPC enhances empathetic, sensitive and appropriate communications2–2 and facilitates history taking, 6 team working,7–7 patient compliance, 10 and clinical outcomes.11–13 Effective IPC also improves patient satisfaction,14–18 professional accountability and responsibility, 19 better-informed consent and reduced medical errors and harm.20–28

Perhaps nowhere is the value of IPC more evident than in emergency medicine (EM). An academic speciality since the 1960s, IPC training is now an integral aspect of many EM training curricula. Yet, such development has not been consistent globally. 29 Up to 2012, two-fifths of EU countries did not recognize EM as a specialty.29, 30 The impact of this delay has limited IPC training for staff working in EM's fast-paced,21, 31–37 stressful, high stakes,11–13, 25 overcrowded, 38 and often disruptive setting.21, 32 The impact of these gaps in training are further underscored amidst growing public attention on bed crises, overcrowding, and mounting waiting times.21, 39–42

With a consistent approach to IPC training in EM continuing to elude practice,43–46 and guided by the importance placed upon it by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)20, 23 and the Institute of Medicine,11, 25, 26, 47–50 we seek to evaluate regnant accounts of IPC training in EM to attend to this gap in understanding27, 51 and guide efforts to design a setting specific training approach.11, 52–55

Methods

To overcome concerns as to the transparency and reproducibility of systematic scoping reviews (SSR)s, Krishna's Systematic Evidence-Based Approach (SEBA) is adopted. SSRs in SEBA adopt a constructivist perspective enabling them to map a complex topic from multiple angles 56 while a relativist lens helps account for the context-specific, sociocultural sensitive and user-dependent nature of IPC training.57–60

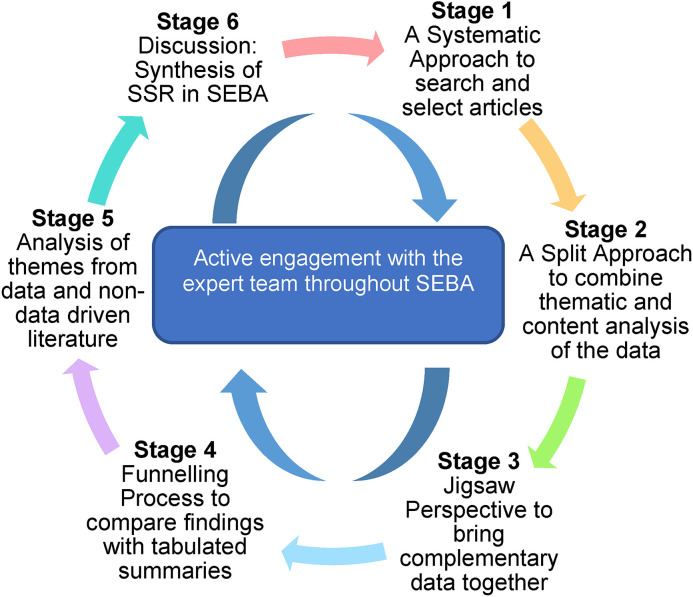

To provide a balanced review and enhance accountability, SSRs in SEBA undergo a 6-staged process. Each stage involves input from an expert team consisting of a medical librarian from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) at the National University of Singapore (NUS), clinicians specialized in EM at the National University Hospital and Singapore General Hospital, and local education experts and clinicians at the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, YLLSoM, and Duke-NUS Medical School. The expert team fulfills several roles, such as reviewing, questioning, and challenging the findings of the research team to ensure a robust and evidence-based driven position as well as aiding with reflexivity and trustworthiness.61, 62

The research and expert teams adopt an interpretivist approach as they proceed through the 6 stages of SEBA57–60 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Systematic Evidence-Based Approach (SEBA) process was employed to identify patterns and relationships among studies.

Stage 1 of SEBA: Systematic Approach

Identifying the Research Question

Ensuring a systematic approach to the synthesis of SSRs in SEBA, the research and expert teams agreed upon the goals, population, context, and concept to be evaluated. The two teams then determined the primary research question to be “what is known about IPC training for physicians in EM?” and the secondary research question to be “what are the characteristics of these IPC programs?”

Inclusion Criteria

These questions were designed on the population, concept, and context elements of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 63 using a Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study (PICOS) format (Table 1).

Table 1.

PICOS, inclusion criteria, and exclusion criteria applied to database search.

| PICOS | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Comparison |

|

|

| Outcome |

|

|

| Study design |

|

Searching

Six members of the research team carried out independent searches of eight bibliographic databases (PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied HealthLiterature (CINAHL), Scopus, Psychological Information Database (PsycINFO), Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Journal Storage (JSTOR), Google Scholar) and one gray literature database (OpenGrey). In keeping with Pham et al's 64 recommendations on ensuring a viable and sustainable research process, the research team confined the searches to articles published between January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2019 to account for prevailing manpower and time constraints. Additionally, another search was conducted on June 26, 2021 to update articles that were published from January 21, 2020 to December 31, 2020. The PubMed search strategy can be found in Supplemental Material A.

Study Selection and Data Charting

The research team independently screened the title and abstracts identified and created individual lists of titles to be included. These were discussed at online meetings. Consensus was achieved on the final articles to be included using Sandelowski, Barroso's 65 “negotiated consensual validation” approach which sees “research team members articulate, defend, and persuade others of the 'cogency' or 'incisiveness' of their points of view or show their willingness to abandon views that are no longer tenable". Eight members of the research team independently reviewed all the full-text articles featured on the final lists, discussed their individual lists at online meetings and reached an agreement once more.

In keeping with the SEBA methodology, the research team then evaluated the references of the included articles. This “snowballing” of references was carried out to ensure a more comprehensive review.

Stage 2 of SEBA: Split Approach

Three teams of researchers simultaneously and independently reviewed the included full-text articles. Here, the combination of independent reviews by various members of the research teams using different methods of analyses provided triangulation 66 while detailing the analytical process improved audits and enhanced the authenticity of the research. 62

The first team summarized and tabulated the included full-text articles in keeping with recommendations drawn from Wong et al's 67 “RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews” and Popay et al's 56 “Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews.” The tabulated summaries ensured that key aspects of the included articles were not lost. These tabulated summaries also included quality appraisals using the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument 68 and the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative (COREQ) 69 studies (Supplemental Material B).

Concurrently, the second team analyzed the included articles using Braun and Clarke's 70 approach to thematic analysis. In Phase 1, the research team carried out independent reviews, actively reading the included articles to find meaning and patterns in the data.72–76 In Phase 2, “codes” were constructed from the “surface” meaning and collated into a codebook to code and analyze the rest of the articles using an iterative step-by-step process. As new codes emerged, these were associated with previous codes and concepts. In Phase 3, the categories were organized into themes that best depict the data. An inductive approach allowed themes to be “defined from the raw data without any predetermined classification”. 75 In Phase 4, the themes were refined to best represent the whole data set. In Phase 5, the research team discussed the results of their independent analyses online and at reviewer meetings. “Negotiated consensual validation” was used to determine if saturation was achieved and establish the final themes. These involved members articulating and defending their analyses where discrepancies arose until consensus was reached.

The third team of researchers employed Hsieh and Shannon's 77 approach to directed content analysis which involved “identifying and operationalizing a priori coding categories.”

The research team drew codes from Miller's 83 treatise entitled “The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance” to guide the coding of the articles. Any data not captured by these codes were assigned a new code. In keeping with deductive category application, coding categories were reviewed and revised as required.

Findings were then discussed online until consensus was reached. The final codes were compared and discussed with the final author who checked the primary data sources to ensure that the codes made sense and were consistently employed. Any differences in coding were resolved between the research team and the final author. “Negotiated consensual validation” was used as a means of peer debrief in allthree teams to further enhance the validity of the findings. 84

The narrative produced was guided by the Best Evidence Medical Education Collaboration guide 85 and the Structured approach to the Reporting In health care education of Evidence Synthesis statement. 86

Stage 3 of SEBA: Jigsaw Perspective

As part of SEBA's reiterative process, the themes and categories identified were discussed with the expert team. Here, the themes and categories are viewed as pieces of a jigsaw puzzle and areas of overlap allow these pieces to be combined to create a wider andholistic view of the overlying data. The combined themes and categories are referred to as themes/categories.

Creating themes/categories relied on the use of Phases 4 to 6 of France et al's 88,89 adaptation of Noblit and Hare's seven phases of meta-ethnography.92 Themes and categories were contextualized by reviewing them against primary codes and subcategories and/or subthemes they were drawn from.87, 88 Reciprocal translation was used to determine if the themes and categoriescould be used interchangeably.

Stage 4 of SEBA: The Funnelling Process

The funneling process sees the themes/categories identified compared with the tabulated summaries.

To provide structure to the funneling process, we employed Phases 3 to 5 of France et al'sadaptation and described the nature, main findings and conclusions of the articles.

Adapting Phase 5, reciprocal translation was used to juxtapose the themes/categories with key messages identified in the tabulated summaries. The verified themes/categories from the Funnelling Process then formed “the line of argument” in the discussion synthesis, in Stage 6 of the SSR in SEBA.

Results

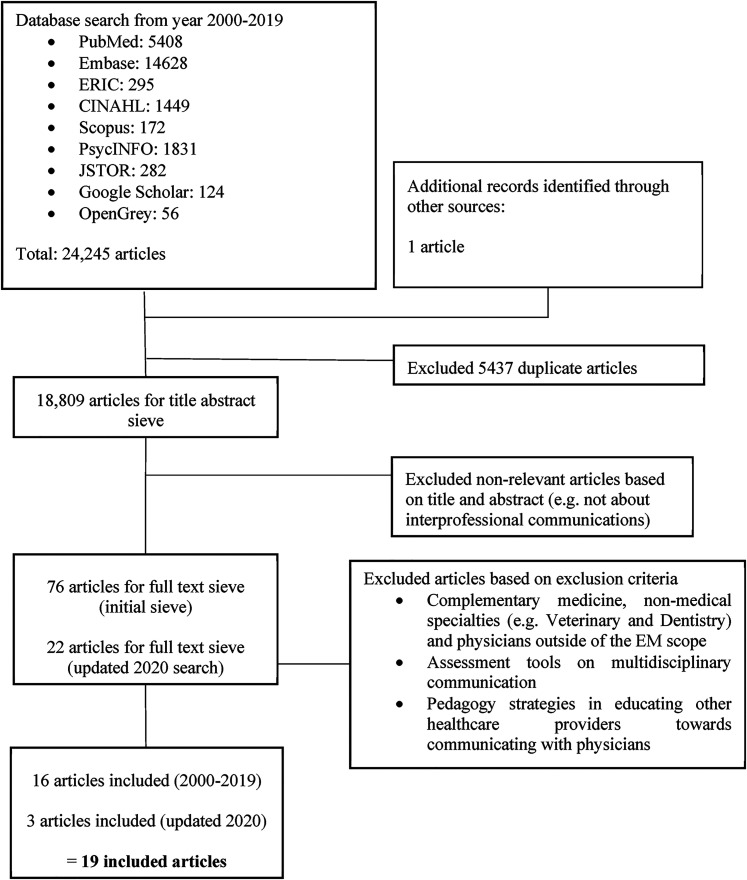

In total, 18,809 titles and abstracts were identified after the removal of duplicates, 98 full-text articles reviewed, and 19 full-text articles analyzed (Figure 2: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart).

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow chart.

Themes/Categories

The final themes/categories identified were:

Indications for IPC programs.

Curriculum and assessment.

Outcomes of IPC programs.

Barriers to IPC programs in ED.

Enablers for successful IPC programs.

Indications for IPC Programs

Given that these themes/categories were not discussed and often merely listed in the included articles, they are summarized in Table 2 for ease of review.

Table 2.

Perceived role and indications in EM training.

| Indications for the need for effective IPC | References |

|---|---|

| Failure leads to medical errors/poor patient outcomes | 25, 50, 92–101 |

| Intensity of EM setting | 20, 92–94, 96, 99, 100, 102 |

| Complex nature of the job as EM physician | 20, 52, 103 |

| Integral to delivering high-quality patient care/positive patient outcomes | 20, 99, 101, 104 |

Abbreviations: EM, emergency medicine; IPC, interprofessional communication.

Curriculum and Assessment

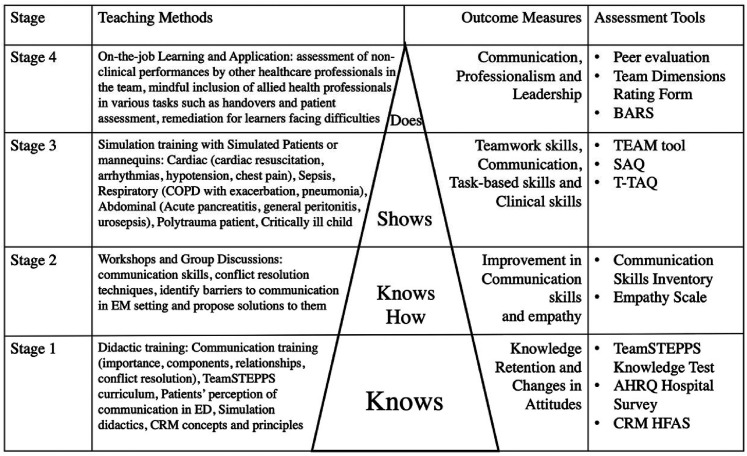

IPC training often begins with didactic teaching that serve to introduce foundational knowledge in both core or elective-based curriculum content.52, 92, 94, 96, 97, 105 This new-found knowledge is then applied in high fidelity simulations with mannikins,93, 96, 97 virtual patients, 93 and/or simulations in-situ.95, 103 Simulations improve team dynamics by providing a “controlled, adaptable environment,” 93 that facilitates mutual understandingand changes in attitude, instils respect 96 and overcomes “social constructs of hierarchy” and “silo mentality.” 93

A gradation in training knowledge, skills and attitudes is summarized in Figure 3 built upon the four stages of Miller’s pyramid and complemented by a variety of assessment tools. These include the use of the Human Factors Attitude Survey to evaluate attitudinal shifts posttraining 106 , as well as the TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitude Questionnaire and other behaviorally anchored rating scales to assess teamwork. 50

Figure 3.

IPC in EM curriculum and assessmment mapped onto Miller's pyramid.

Abbreviations: AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; BARS, behaviorally anchored rating scales; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRM, crisis resource management; HFAS, Human Factors Attitude Survey; EM, emergency medicine; IPC, interprofessional communication; SAQ, short answer questions; T-TAQ, Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire.

Each stage of the learning process is accompanied by outcome measures and assessment tools which are also summarized in Supplemental Material C.

Outcomes of IPC Programs

The outcome measures for effective IPC also take a long-term perspective as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Outcomes in EM IPC training.

| Outcomes of IPC training | References |

|---|---|

| Host organization | |

| Improved host organization outcomes (hospital performance and reimbursement, patient safety outcomes) | 96–98, 102 |

| Reduction in adverse events and errors | 25, 50, 98, 100 |

| Liability cost savings | 50 |

| Participants and colleagues | |

| Improvements in attitudes and behavior towards IPC, teamwork, and internal communications | 52, 95–97, 101, 103, 104, 106 |

| Increased safety attitudes | 95, 103 |

| Patients | |

| Greater satisfaction in the quality of staff and patient communications | 52, 96 |

| Reduced communication issues between staff and patients | 52 |

| Reduced length of hospital stay | 97 |

| Improved patient experience | 52 |

Abbreviations: EM, emergency medicine; IPC, interprofessional communication.

Barriers to IPC Programs in ED

The long-term nature of the goals of IPC programs in EM is reflected in the obstacles to achieving them.92, 93 These include frequent turnover of staff, staff of various backgrounds, skills, experience and clinical specialities, shift work, high patient load, rapid and complex decision-making and past negative interactions with other health care professionals.20, 92 In turn, these barriers hinder culture change, shifts in institutionalized power dynamics and flattening of the hierarchical nature within ED. 107

Enablers for Successful IPC Programs

Enablers to a successful IPC program similarly reflect its long term goals and include the sustained support of the host organization, 96 the provision of tutor training and compensation, mandating attendance, ensuring effective assessments of learning outcomes and effective provision of feedback. 96

Stage 5 of SEBA: Analysis of Themes From Data and Nondata Driven Literature

With concerns over the potential impact of unevidenced, often opinion-led data from gray literature, the research team undertook a comparison of themes identified from gray literature and those from research-driven articles to enhance the accountability and the reproducibility of Stage 6 of SEBA. The results from the gray literature were found to be congruent with those from peer-reviewed research-based articles.

Discussion

Stage 6 of SEBA: Synthesis of SSR in SEBA

In answering its primary research question on “what is known about IPC training for physicians in EM?” ,this SSR in SEBA of IPC training in EM suggests that IPC training occurs in stages. This begins with the use of didactic training that then progresses to the application of the physician’s new knowledge. Practice in the clinical situation follows, culminating in the formation of attitudes and behaviors that value IPC communications. Supporting this premise that IPC competencies develop on prevailing knowledge and skills is the presence of a variety of assessment tools aimed at assessing IPC skills and attitudes along with this longitudinal development.

Having established the presence of a longitudinal training and assessment process that corresponds with Miller’s Pyramid of Clinical Competence as shown in Figure 3, it is possible to deduce specific stages in the development of IPC skills. In addressing its secondary research question, this SSR in SEBA suggests that IPC programs in EM are characterized by competency-based stages in the training and development of IPC knowledge, skills and attitudes among EM physicians. The achievement of skills in each stage is assessed by the corresponding tools suggesting the presence of competency-based stages thatalign with the competencies set out by ACGME20, 23 and the Institute of Medicine. 11 Such developments are also consistent with the stated outcomes of these programs and may also be inferred from the enablers and barriers to IPC programs.

Here, the presence of stages underscores the importance of the host organization in ensuring an effective assessment of the various stages, curricula topics and providing assiduous program oversight and support. 97 This also underlines the need for training and assessments to be carried out at appropriate junctures in the development of EM trainees to ensure they achieve requisite competencies in core topics before venturing to secondary content.

This further highlights the need for the IPC training program specific assessment process to account for the personalized needs of varied learners.108, 109 To this end, portfolios may be suitable learning and evaluation tools for IPC in EM due to their flexible and holistic nature—allowing for multisource feedback, documentation and reflection of learning activities and assessment scores in one convenient central location. This would offer a comprehensive overview of the learners’ progress, enabling easy identification of areas for improvement.110–112

Overall, this SSR in SEBA highlights the need for greater awareness of the competency-based stages in the development of IPC skills and urges more holistic and longitudinal consideration of its effects upon the physician.

Limitations

Despite efforts to enhance the reproducibility and transparency of the SSR through SEBA, we still face gaps in our methodology and analysis. While we have conducted a two-tiered searching strategy, through both independent searching of selected databases by our expert team and repeated sieving of reference lists of publications, there maybe important papers that have been omitted. Similarly, while use of the split approach and tabulated summaries in SEBA allowed for triangulation and ensured that a holistic picture was constructed from different and diverse perspectives, inherent biases among the reviewers may still have impacted the analysis of the data and construction of themes. Lastly, drawing conclusions from a limited pool of largely North American and European-centric accounts, further narrowed by focusing upon publications in English, may limit the applicability of the findings to other cultural and geographical contexts.

Conclusion

Data on the stages of training forwarded by this SSR will be of interest to educationalists and program designers involved in IPC training in EM, where teamwork and communication are instrumental in the provision of safe and effective care for patients, especially in global health emergencies such as the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. A stage-based curriculum suggests that trainers need to be aware of the level of experience and abilities of physicians in training and cater their training approach and assessments to meet these personalized needs. Development of skills and abilities needed for effective IPC should begin in medical school and junior residency programs, underlining the role of portfolios to capture their competencies and reflections on their training thus far. Gaps in understanding and supporting trainers, guiding the host organization, and the lack of effective oversight of the stage-wise development of IPC competencies underline areas for further study if IPC training is to achieve its goals of improving safety and patient experience in EM.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to late Dr S Radha Krishna whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this study. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose advice and feedback greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Kilner E, Sheppard LA. The role of teamwork and communication in the emergency department: a systematic review. Int Emerg Nurs. 2010;18(3):127-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grudzen CR, Emlet LL, Kuntz J, et al. EM Talk: communication skills training for emergency medicine patients with serious illness. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2016;6(2):219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacLeod RD. On reflection: doctors learning to care for people who are dying. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(11):1719-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park I, Gupta A, Mandani K, Haubner L, Peckler B. Breaking bad news education for emergency medicine residents: a novel training module using simulation with the SPIKES protocol. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3(4):385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart M, Brown JB, Boon H, Galajda J, Meredith L, Sangster M. Evidence on patient-doctor communication. Cancer. 1999;25(1999):30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenzweig S, Brigham TP, Snyder RD, Xu G, McDonald AJ. Assessing emergency medicine resident communication skills using videotaped patient encounters: gaps in inter-rater reliability. J Emerg Med. 1999;17(2):355-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parush A, Mastoras G, Bhandari A, et al. Can teamwork and situational awareness (SA) in ED resuscitations be improved with a technological cognitive aid? Design and a pilot study of a team situation display. J Biomed Inform. 2017;76:154-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bok C, Ng CH, Koh JWH, et al. Interprofessional communication (IPC) for medical students: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng CH, Ong ZH, Koh JWH, et al. Enhancing interprofessional communications training in internal medicine. Lessons drawn from a systematic scoping review from 2000 to 2018. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2020;40(1):27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spandorfer JM, Karras DJ, Hughes LA, Caputo C. Comprehension of discharge instructions by patients in an urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25(1):71-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. In: Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. National Academies Press (US); 2000. Copyright 2000 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pham JC, Story JL, Hicks RW, et al. National study on the frequency, types, causes, and consequences of voluntarily reported emergency department medication errors. J Emerg Med. 2011;40(5):485-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reader TW, Flin R, Mearns K, Cuthbertson BH. Developing a team performance framework for the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(5):1787-1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boudreaux ED, Cruz BL, Baumann BM. The use of performance improvement methods to enhance emergency department patient satisfaction in the United States: a critical review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(7):795-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lau FL. Can communication skills workshops for emergency department doctors improve patient satisfaction? J Accid Emerg Med. 2000;17(4):251-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer TA, Cates RJ, Mastorovich MJ, Royalty DL. Emergency department patient satisfaction: customer service training improves patient satisfaction and ratings of physician and nurse skill. J Healthc Manag. 1998;43(5):427-440. discussion 441–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercer LM, Tanabe P, Pang PS, et al. Patient perspectives on communication with the medical team: pilot study using the communication assessment tool-team (CAT-T). Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(2):220-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan HQM, Chin YH, Ng CH, et al. Multidisciplinary team approach to diabetes. An outlook on providers’ and patients’ perspectives. Prim Care Diabetes. 2020;14(5):545-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies C. Getting health professionals to work together: there’s more to collaboration than simply working side by side. BMJ. 2000;320(7241):1021–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alameddine M, Mufarrij A, Saliba M, Mourad Y, Jabbour R, Hitti E. Nurses’ evaluation of physicians’ non-clinical performance in emergency departments: advantages, disadvantages and lessons learned. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chisholm CD, Collison EK, Nelson DR, Cordell WH. Emergency department workplace interruptions Are emergency physicians “interrupt-driven” and “multitasking”? Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(11):1239-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2004;13(suppl 1):i85-i90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lockyer J. Multisource feedback in the assessment of physician competencies. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003;23(1):4-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manser T. Teamwork and patient safety in dynamic domains of healthcare: a review of the literature. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53(2):143-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morey JC, Simon R, Jay GD, et al. Error reduction and performance improvement in the emergency department through formal teamwork training: evaluation results of the MedTeams project. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1553-1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Risser DT, Rice MM, Salisbury ML, et al. The potential for improved teamwork to reduce medical errors in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34(3):373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherbino J, Bandiera G, Frank JR. Assessing competence in emergency medicine trainees: an overview of effective methodologies. Cjem. 2008;10(4):365-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young G, Charns M, Desai K, Daley J, Henderson W, Khuri S. Patterns of coordination and clinical outcomes: a study of surgical services. Paper presented at Academy of Management Proceedings; 1997. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suter RE. Emergency medicine in the United States: a systemic review. World J Emerg Med. 2012;3(1):5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Totten V, Bellou A. Development of emergency medicine in Europe. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(5):514-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castelao EF, Boos M, Ringer C, Eich C, Russo SG. Effect of CRM team leader training on team performance and leadership behavior in simulated cardiac arrest scenarios: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eisenberg EM, Baglia J, Pynes JE. Transforming emergency medicine through narrative: qualitative action research at a community hospital. Health Commun. 2006;19(3):197-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes CW, Rhee A, Detsky ME, Leblanc VR, Wax RS. Residents feel unprepared and unsupervised as leaders of cardiac arrest teams in teaching hospitals: a survey of internal medicine residents. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(7):1668-1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hjortdahl M, Ringen AH, Naess A-C, Wisborg T. Leadership is the essential non-technical skill in the trauma team-results of a qualitative study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobsson M, Hargestam M, Hultin M, Brulin C. Flexible knowledge repertoires: communication by leaders in trauma teams. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2012;20(1):44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leenstra NF, Jung OC, Johnson A, Wendt KW, Tulleken JE. Taxonomy of trauma leadership skills: a framework for leadership training and assessment. Acad Med. 2016;91(2):272-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marsch SC, Muller C, Marquardt K, Conrad G, Tschan F, Hunziker PR. Human factors affect the quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in simulated cardiac arrests. Resuscitation. 2004;60(1):51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Åström K, Duggan C, Bates I. Evaluating an intervention to improve communication between healthcare professionals within secondary care. Pharm Educ. 2007;7(4):325–333. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Axon DR, Lim RHM, Lewis PJ, et al. Junior doctors’ communication with hospital pharmacists about prescribing: findings from a qualitative interview study. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2018;25(5):257-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nijjer S, Gill J, Nijjer S. Effective collaboration between doctors and pharmacists. Hosp Pharm London. 2008;15(5):179. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sullivan AF, Bachireddy C, Steptoe AP, Oldfield J, Wilson T, Camargo CA, Jr. A profile of freestanding emergency departments in the United States, 2007. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(6):1175-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coiera EW, Jayasuriya RA, Hardy J, Bannan A, Thorpe ME. Communication loads on clinical staff in the emergency department. Med J Aust. 2002;176(9):415-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmitt M, Blue A, Aschenbrener CA, Viggiano TR. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: reforming health care by transforming health professionals’ education. Acad Med. 2011;86(11):1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zwarenstein M, Reeves S, Barr H, Hammick M, Koppel I, Atkins J. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;1:CD002213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barrett J, Gifford C, Morey J, Risser D, Salisbury M. Enhancing patient safety through teamwork training. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2001;21(4):57-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients: results of the harvard medical practice study I. 1991. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(2):145-151. discussion 151–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nielsen PE, Goldman MB, Mann S, et al. Effects of teamwork training on adverse outcomes and process of care in labor and delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(1):48-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shapiro M, Morey J, Small S, et al. Simulation based teamwork training for emergency department staff: does it improve clinical team performance when added to an existing didactic teamwork curriculum? BMJ Qual Saf. 2004;13(6):417-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salas E, Rosen MA, King H. Managing teams managing crises: principles of teamwork to improve patient safety in the emergency room and beyond. Theor Issues Ergon Sci. 2007;8(5):381-394. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cinar O, Ak M, Sutcigil L, et al. Communication skills training for emergency medicine residents. Eur J Emerg Med. 2012;19(1):9-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Croskerry P, Shapiro M, Campbell S, et al. Profiles in patient safety: medication errors in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(3):289-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jain S, Basu S, Parmar VR. Medication errors in neonates admitted in intensive care unit and emergency department. Indian J Med Sci. 2009;63(4):145–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patanwala AE, Warholak TL, Sanders AB, Erstad BL. A prospective observational study of medication errors in a tertiary care emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(6):522-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Developing guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(Suppl 1):A7 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pring R. The ‘false dualism’of educational research. J Phil Educ. 2000;34(2):247-260. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crotty M. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ford DW, Downey L, Engelberg R, Back AL, Curtis JR. Discussing religion and spirituality is an advanced communication skill: an exploratory structural equation model of physician trainee self-ratings. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(1):63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schick-Makaroff K, MacDonald M, Plummer M, Burgess J, Neander W. What synthesis methodology should I use? A review and analysis of approaches to research synthesis. AIMS Public Health. 2016;3(1):172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alvesson M, Sköldberg K. Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research. Sage; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cleland J, Durning SJ. Researching medical education. John Wiley & Sons; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peters MGC, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. 2015. Accessed April 29, 2019.

- 64.Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer publishing company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tavakol M, Sandars J. Quantitative and qualitative methods in medical education research: AMEE guide No 90: part I. Med Teach. 2014;36(9):746–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES Publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reed DA, Beckman TJ, Wright SM, Levine RB, Kern DE, Cook DA. Predictive validity evidence for medical education research study quality instrument scores: quality of submissions to JGIM’s medical education special issue. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):903-907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ng YX, Koh ZYK, Yap HW, et al. Assessing mentoring: a scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sawatsky AP, Parekh N, Muula AS, Mbata I, Bui T. Cultural implications of mentoring in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2016;50(6):657-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Voloch K-A, Judd N, Sakamoto K. An innovative mentoring program for Imi Ho’ola post-baccalaureate students at the university of Hawai’i John A. Burns school of medicine. Hawaii Med J. 2007;66(4):102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cassol H, Pétré B, Degrange S, et al. Qualitative thematic analysis of the phenomenology of near-death experiences. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0193001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stenfors-Hayes T, Kalén S, Hult H, Dahlgren LO, Hindbeck H, Ponzer S. Being a mentor for undergraduate medical students enhances personal and professional development. Med Teach. 2010;32(2):148-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Neal JW, Neal ZP, Lawlor JA, et al. What makes research useful for public school educators?. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2018;45(3):432-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wagner-Menghin M, de Bruin A, van Merriënboer JJ. Monitoring communication with patients: analyzing judgments of satisfaction (JOS). Adv Health Sci Educ. 2016;21(3):523-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2004;1:159-176. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Humble ÁM. Technique triangulation for validation in directed content analysis. Int J Qual. 2009;8(3):34-51. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9):S63-S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marušić A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. Jama. 2006;296(9):1103-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haig A, Dozier M. BEME Guide no. 3: systematic searching for evidence in medical education--part 2: constructing searches. Med Teach. 2003;25(5):463-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Frei E, Stamm M, Buddeberg-Fischer B. Mentoring programs for medical students-a review of the PubMed literature 2000-2008. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.France EF, Wells M, Lang H, Williams B. Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis. Syst Rev. 2016;5:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.France EF, Uny I, Ring N, et al. A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.France EF, Wells M, Lang H, Williams B. Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.France EF, Uny I, Ring N, et al. A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Noblit GW, Hare RD, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Vol 11. SAGE; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cameron KA, Engel KG, McCarthy DM, et al. Examining emergency department communication through a staff-based participatory research method: identifying barriers and solutions to meaningful change. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(6):614-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chung HO, Medina D, Fox-Robichaud A. Interprofessional sepsis education module: a pilot study. Cjem. 2016;18(2):143-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lisbon D, Allin D, Cleek C, et al. Improved knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors after implementation of TeamSTEPPS training in an academic emergency department: a pilot report. Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(1):86-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Paltved C, Bjerregaard AT, Krogh K, Pedersen JJ, Musaeus P. Designing in situ simulation in the emergency department: evaluating safety attitudes among physicians and nurses. Adv Simul. 2017;2(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sweeney LA, Warren O, Gardner L, Rojek A, Lindquist DG. A simulation-based training program improves emergency department staff communication. Am J Med Qual. 2014;29(2):115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wong AH, Gang M, Szyld D, Mahoney H. Making an “attitude adjustment": using a simulation-enhanced interprofessional education strategy to improve attitudes toward teamwork and communication. Simul Healthc. 2016;11(2):117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wong A, Gang M, Wing L, Ng G, Szyld D, Mahoney H. Team training for success: an interprofessional curriculum for the resuscitation of emergency and critical patients. MedEdPORTAL. 2014;10. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rixon A, Rixon S, Addae-Bosomprah H, Ding M, Bell A. Communication and influencing for ED professionals: a training programme developed in the emergency department for the emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(4):404-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Truta TS, Boeriu CM, Copotoiu S-M, et al. Improving nontechnical skills of an interprofessional emergency medical team through a one day crisis resource management training. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(32):e11828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rider AC, Anaebere TC, Nomura M, Duong D, Wills CP. A structured curriculum for interprofessional training of emergency medicine interns. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(1):149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Azizoddin DR, Vella Gray K, Dundin A, Szyld D. Bolstering clinician resilience through an interprofessional, web-based nightly debriefing program for emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Interprof Care. 2020;34(5):711-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Couto TB, Kerrey BT, Taylor RG, FitzGerald M, Geis GL. Teamwork skills in actual, in situ, and in-center pediatric emergencies: performance levels across settings and perceptions of comparative educational impact. Simul Healthc. 2015;10(2):76-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Keshmiri F, Rezai M, Tavakoli N. The effect of interprofessional education on healthcare providers’ intentions to engage in interprofessional shared decision-making: perspectives from the theory of planned behaviour. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(4):1153-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Olde Bekkink M, Farrell SE, Takayesu JK. Interprofessional communication in the emergency department: residents’ perceptions and implications for medical education. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:262-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Grogan EL, Stiles RA, France DJ, et al. The impact of aviation-based teamwork training on the attitudes of health-care professionals. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(6):843-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Calhoun AW, Boone MC, Porter MB, Miller KH. Using simulation to address hierarchy-related errors in medical practice. Perm J. 2014;18(2):14-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zich DK, Adams JG. Teaching the intangibles: professionalism and interpersonal skills/communication. In: Rogers RL, Amal M, Winters ME, Martinez JP, Mulligan TM. eds. ,Practical Teaching in Emergency Medicine. Wiley-Blackwell; 2009:137-150. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yaow CYL, Mok HT, Ng CH, Devi MK, Iyer S, Chong CS. Difficulties faced by general surgery residents. A qualitative systematic review. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(6):1396-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.O’Sullivan P, Greene CJ. Portfolios: possibilities for addressing emergency medicine resident competencies. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(11):1305-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mathers N, Challis M, Howe A, Field NJ. Portfolios in continuing medical education–effective and efficient?. Med Educ. 1999;33(7):521-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Challis M. AMEE Medical education guide No. 11 (revised): portfolio-based learning and assessment in medical education. Med Teach. 1999;21(4):370-386. [Google Scholar]