Abstract

Background/Aims

Constipation is a common gastrointestinal problem in the elderly. Because of the limitations of life style modifications and the comorbidity, laxative use is also very common. Therefore, this study reviews the latest literature on the effect and safety of laxative in the elderly.

Methods

A systematic review of randomized controlled trials investigating the effectiveness and safety of laxatives for constipation in elderly patients over 65 years old were performed using the following databases PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library.

Results

Twenty-three randomized controlled trials were included in this review. Among the selected studies, 9 studies compared laxative with placebo and 5 studies compared laxatives of the same type. Four studies compared different types of laxatives or compared combination agents. Five studies compared novel medications such as prucalopride, lubiprostone, and elobixibat with placebo. Psyllium, calcium polycarbophil, lactulose syrup, lactitol, polyethylene glycol, magnesium hydroxide, stimulant laxative with or without fiber, and other medications were more effective than placebo in elderly constipation patients in short-term. Generally, the frequency and severity of adverse effects of laxative were similar between the arms of studies.

Conclusions

Bulk laxative, osmotic laxative, stimulant laxative with or without fiber, and other medications can be used in elderly patients in short-term within 3 months with reasonable safety. However, the quality of included studies was not high and most of studies was conducted in a small number of patients. Among these laxatives, polyethylene glycol seems to be safe and effective in long-term use of about 6 months in elderly patients.

Keywords: Aged, Constipation, Laxatives, Systematic review

Introduction

Constipation is a common functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder. Incidence of constipation increases with advancing age, particularly after 65 years of age.1 Studies have reported that the prevalence of constipation in the elderly ranges from 24% to 30% depending on the definition used and population studied.2-5 The severity of constipation in the older people also shows gender differences and severe constipation is more common in elderly women, with rates of constipation 2 times to 3 times higher than that in elderly men.6 Laxative use due to constipation symptom is very common. Daily laxative uses are reported to be 10% of community dwelling older adults and 50% of nursing home residents.7,8 Constipation in the elderly seems to cause a serious deterioration in quality of life and appears to have a particularly negative impact on mental health. Study of constipation and health status among older adults have shown that mental status was poorer and psychological distress was greater in constipated than non-constipated elderly.9 In a survey of community-dwelling older adults with Medical Outcome Study Short-Form 36 (SF-36), O’Keefe et al10 reported that respondents with constipation had lower SF-36 scores for physical functioning, mental health, general health perception, and bodily pain than respondents without constipation. Therefore, the recognition, prevention, and treatment of constipation plays an important role in raising the quality of life of elderly patients and in preventing complications such as fecal impaction.

Reduced physical activity and polypharmacy are considered important causes of constipation in elderly.11,12 Life style modification (such as increased fluid, fiber, and exercise) and discontinuation of unnecessary medications are recommended as the first steps in the treatment of constipation in elderly. Unfortunately, it is not always possible to reduce the number of medications in elderly patients and it is very difficult to increase their physical activity in the short-term. Therefore, it is important to provide effective and safe pharmacologic treatments for the elderly constipation patients. Although constipation is a common problem, the satisfaction with the treatment of constipation is not high. In a large survey study, nearly half (47%) were not completely satisfied, mainly because of efficacy (82%) and safety (16%) concerns.13 Efficacy is the most important factor in laxative selection. However, elderly patients have many comorbidities and polypharmacy, so special attention should be paid to safety of medications. Many studies have reported the efficacy and safety of laxatives in elderly populations. Literature review of laxatives in older patients published by Fleming and Wade14 in 2010 have concluded that higher-quality trials in older patients are needed to create more definitive recommendations in this population. After this review, new medications such as prucalopride and linaclotide have been studied and have been actively used in current practice. Therefore, this systematic review aims to include evidences for a new medications that has not been previously covered in reviews for elderly constipation patients. In addition, this review focuses on the evidences for the safety of medications, especially for long-term use.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Search Term

We performed systematic search of the literatures using PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. There was no language restriction placed on the electronic searches and database was searched from their inception to 31 December 2020. A manual search of relevant reviews and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was also conducted to identify additional studies not found in the electronic searches. The following search terms were used in connection in the search process: “constipation,” “chronic constipation,” “laxatives,” “fiber,” “bulk laxatives,” “bulking agent,” “stimulant laxatives,” “bisacodyl,” “senna,” “osmotic laxatives,” “lactulose,” “polyethylene glycol (PEG),” “stool softener,” “lubiprostone,” “linaclotide,” “prucalopride,” “elobixibat,” “velusetrag,” “management,” “treatment,” “elderly,” “geriatrics,” “senior,” “long-term care,” “nursing home,” “residential care,” and “institutionalized.” Alternative terms were used according to the databases and Boolean connectors were used as appropriate. This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis and has been exempted from an approval of Institutional Review Board because it has nearly no harm to humans.

Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

This review included RCTs and post hoc analysis of RCTs which assessed the efficacy and safety of medical treatment for chronic constipation in elderly (65 years and above) as whole population or subpopulation compared with placebo or other laxatives. The pharmacologic treatments included only bulk laxatives, osmotic laxatives, stimulant laxatives, and new medications, such as prucalopride, lubiprostone, linaclotide, velusetrag, and elobixibat. On the other hand, studies on dietary supplements, prebiotics, and probiotics were excluded. Herbal preparations that are used only in some areas and have non-formatted ingredients and capacities and only diet-based interventions for fiber were also excluded. Based on the type of research, this review excluded animal studies, review articles, pharmacologic studies, case reports, and observational studies. However, conference abstracts of RCTs and post hoc analysis of RCTs are included if key clinical data can be extracted from the conference abstracts. Diagnosis of constipation was limited to those defined by Rome criteria or other specific criteria (such as number of defecations of less than 3 times a week). The studies with self-reported constipated patients or normal elderly population and trials that studied acute constipation, postoperative constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, and opioid-induced constipation were also excluded from this review. Studies from which important data cannot be extracted because full-text was not available or could not be interpreted in English even if it was available were excluded.

The study selection was done in 2 steps following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for review: selection based on reviewing titles and abstracts, and then full-text articles.15 After removal of duplicates, 2 reviewers (S.J.K. and Y.S.C.) independently screened all titles and abstracts. Discrepancy between reviewers was resolved by discussion. Then, full-text of articles were independently assessed by the aforementioned 2 reviewers, who made the final decision for inclusion.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (S.J.K. and Y.S.C) independently performed data extraction and assessed methodological risk of bias. Discrepancies in data extraction and assessment of bias were discussed during a consensus meeting. A standardized data abstraction tool was used for data collection for each included study. The data were summarized in Table 1 that included the following elements: study design, population studied, the number of participants, baseline characteristics, outcome measures, and summary of the overall results. The quality of RCTs with parallel design was evaluated using domain-based risk of bias as recommended by the Cochrane collaboration.16 This approach requires studies to be assessed across 6 domains, including sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. For the RCTs with cross-over design, the 9 items based on the Cochrane handbook and expert comments were applied to evaluate the risk of bias in: appropriate cross-over design, the randomized order of receiving treatment, carry-over effects, unbiased data, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other biases.17 All items were judged as high, unclear, or low risk of bias based on the study methods in the original articles.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Studies Comparing Laxative With Placebo or Comparing Laxatives of Same Types

| Study, country | Comparison | Design | Eligible population | Constipation criteria | Intervention and duration | Number of patients and mean age | Primary outcome | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk laxatives | ||||||||

| Ewerth et al18 (1980), Sweden | Bulk vs Placebo | Double-blind cross-over study | Constipated patients with diverticuli | Infrequent (3-4 day interval) and painful defecation |

|

|

|

|

| Finlay19 (1988), UK | Bulk vs Placebo | Open, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel study | Elderly patients with chronic constipation in continuing care | Chronic constipation with need for regular laxative, suppositories and/or manual evacuation |

|

|

|

|

| Rajala et al20 (1988), Finland | Bulk vs Placebo | Randomized, double-blind study | Hospitalized elderly patients | Defecation less than once daily and with difficulty |

|

|

|

|

| Cheskin et al21 (1995), USA | Bulk vs Placebo | Single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study | Community-living older men and women with chronic constipation | < 3 BMs/wk and/or feeling of incomplete evacuation and/or hard stool with straining > 25% of time |

|

|

|

|

| Chokhavatia et al22 (1988), USA | Bulk vs Bulk | Unblinded, randomized study | Outpatients age range 55-81 yr | Regular laxative use |

|

|

|

|

| Osmotic laxatives | ||||||||

| Wesselius-De Casparis et al23 (1968), Netherland | Osmotic vs Placebo | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel study | Elderly patients with chronic constipation | Regular laxative use |

|

|

Treatment success if the patient needed no laxatives at all or only once in 21 day | A: 86% B: 60%a |

| Sanders24 (1978), USA | Osmotic vs Placebo | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel study | Elderly constipated patients living in nursing home | ≤ 3 BM/wk and ≥ 1 constipation related symptom |

|

|

|

|

| Vanderdonckt et al25 (1990), Belgium | Osmotic vs Placebo | Double-blind, cross-over study | Elderly patients with chronic constipation | ≤ 3 BMs per wk without laxative use and ≥ 1 symptom such as hard stools, pain |

|

|

|

|

| Dipalma et al26 (2007), USA | Osmotic vs Placebo | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel study | Adults and elderly who met defined criteria for chronic constipation | Modified Rome criteria |

|

|

Relief of modified Rome criteria for constipation for 50% or more | |

| Lederle et al27 (1990), USA | Osmotic vs Osmotic | Randomized, double-blind, cross-over study | Men aged 65 yr to 86 yr with chronic constipation | ≤ 3 SBM/wk, ≤1 BM/day with current laxatives and at least one related chronic symptom such as straining, hard stool |

|

|

|

|

| Seinelä et al28 (2009), Finland | Osmotic vs Osmotic | Randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study | Elderly institutionalized, constipated patients who have used PEG with electrolyte at a stable dose | Regular use of PEG |

|

|

|

|

| Chassagne et al29 (2017), France | Osmotic vs Osmotic | Randomized, single-blind, parallel-group study | Patients aged 70 yr and older with a history of chronic constipation | Rome I criteria |

|

|

|

|

| Softener | ||||||||

| Hyland and Foran30 (1968), UK | Softener vs Placebo | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study | Hospitalized elderly patients in geriatric ward | Chronic constipation |

|

|

|

|

| Fain et al31 (1978), USA | Softener vs Softener | Randomized, single-blinded, parallel study | Institutionalized elderly patients | Chronic functional constipation dependent on laxative use |

|

|

|

aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, cP < 0.001.

F, female; M, male; qd, once a day; bid, 2 times a day; tid, 3 times a day; qid, 4 times a day; BMs, bowel movements; NS, not significant; AEs, adverse effects; SBMs, spontaneous bowel movements; PEG, polyethylene glycol; DSS, dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate; DCS, dioctly calcium sulfosuccinate.

Results

Results of Systematic Search and Characteristics of Included Studies

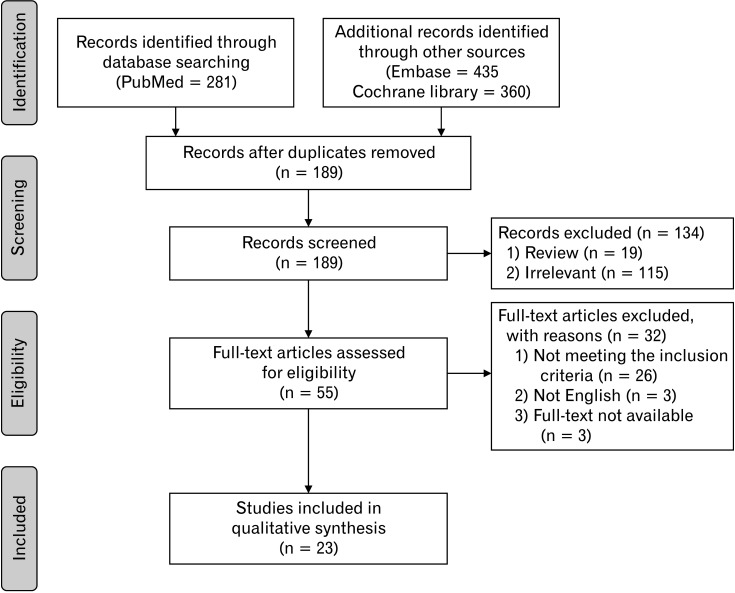

The PRISMA flow diagram of the selection for the studies is shown in Figure 1. From combined literature search using 3 databases and manual search, a total of 968 studies were identified. After removing duplicates (n = 802), the aforementioned 2 reviewers screened the potentially relevant studies (n = 166) from titles and abstracts independently. Review articles (n = 19) and irrelevant articles (n = 93) were excluded from screening. Full-text was not available for 3 studies. Full-text was reviewed for the 52 eligible articles. The full-text review excluded 26 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria and 3 studies that were not in English. The excluded studies from full-text review and studies of which full-texts were not available are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Finally, 23 RCTs which met the inclusion criteria were selected for systematic review.18-40 Main characteristics of studies were shown in Tables 1-3. Adverse effects (AEs) of laxatives are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart of the systematic literature review and selection of literature.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Studies Comparing Different Types of Laxatives or Using Combination Agents

| Study, country | Comparison | Design | Eligible population | Constipation criteria | Intervention and duration | Number of patients and mean age | Primary outcome | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinnunen and Salokannel32 (1987), Finland | Bulk vs Osmotic | Randomized, cross-over study | Geriatric long-stay patients aged 65 yr or older | Patients using laxatives |

|

|

|

|

| Kinnunen et al33 (1993), Finland | Bulk + stimulant vs Osmotic | Open, randomized controlled, cross-over study | Geriatric long-stay patients aged 65-94 yr with constipation | BMs < 2/wk for more than 3 mo |

|

|

|

|

| Passmore et al34 (1993), UK | Bulk + stimulant vs Osmotic | Randomized, double-blind, cross-over study | Long stay elderly patients or nursing home care with a history of chronic constipation | History of chronic constipation (< 3 BMs/wk) or need for regular laxatives |

|

|

|

|

| Pers and Pers35 (1983), Sweden | Bulk + stimulant vs Bulk + stimulant | Open, randomized, controlled, cross-over study | Hospitalized elderly patients with constipation | Chronic constipation necessitating laxative treatment |

|

|

BMs/wk | A: 3.3 B: 3.9a |

aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01.

F, female; BMs, bowel movements; qd, 4 times a day; bid, 2 times a day; NS, not significant.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Studies Comparing Novel Medications With Placebo

| Study, country | Comparison | Design | Eligible population | Constipation criteria | Intervention and duration | Number of patients and mean age | Primary outcome | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camilleri et al36 (2009), USA and Belgium | Prucalopride vs Placebo | Randomized, double-blind, Phase II, placebo-controlled, dose escalation study | Elderly (> 65 yr) patients with constipation residing in a nursing facility | Patients who had a history of constipation, having received treatment for constipation at any time during the 4 wk preceding entry into the study |

|

|

|

See Table 4 |

| Müller-Lissner et al37 (2010), Germany and Belgium | Prucalopride vs Placebo | Multicenter, parallel-group, placebo-controlled Phase III trial | Chronic constipation patients aged > 65 yr | Two or fewer SCBMs per wk in the past 6 mo and one or more of the following for at least a quarter of the symptoms |

|

|

|

|

| Ueno et al38 (2006), USA | Lubiprostone vs Placebo | Pooled analysis of elderly subjects in 3 RCTs | Chronic constipation patients aged ≥ 65 yr | Rome II criteria for functional constipation |

|

|

|

|

| Nakajima et al39 (2019), Japan | Elobixibat vs Placebo | Post hoc analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials | Patients with severe constipation | ≤ 2 SBMs per wk and ≤ 3 Bristol Stool Form Scale score |

|

|

Additional SBMs/wk compared with placebo | |

| Menees et al40 (2020), USA | Plecanatide vs Placebo | Pooled analysis of 4 RCTs | Chronic constipation and IBS-C | Rome III criteria |

|

|

|

|

aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01.

F, female; qd, once a day; bid, 2 times a day; AEs, adverse effects; QTc, corrected QT interval; SCBMs, spontaneous complete bowel movements; SBMs, spontaneous bowel movements; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome constipation type.

Table 4.

Adverse Effects of Laxatives From Randomized Controlled Trials

| RCTs | Comparison | Intervention | Duration | Adverse events | Drop out |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-class comparisons | |||||

| Ewerth et al18 (1980), Sweden | Bulk vs Placebo |

|

8 wk |

|

10% (1/10) |

| Finlay19 (1988), UK | Bulk vs Placebo |

|

6 wk | One patient reported difficulty in swallowing bran | 14.3% (2/14) (one due to swallowing difficulty and the other due to refusal of bran) |

| Rajala et al20 (1988), Finland | Bulk vs Placebo |

|

2 wk | No significant changes were observed in blood glucose, serum cholesterol or triglyceride, body weights or fecal pH values in either group | Not described |

| Cheskin et al21 (1995), USA | Bulk vs Placebo |

|

4 wk | No difference between groups | 30.0% (3/10) (cannot tolerate the repeated perfused catheter for anorectal manometry) |

| Chokhavatia et al22 (1988), USA | Bulk vs Bulk |

|

3 wk | Not described | 7.0% (3/42) (all unrelated to the study medication) |

| Wesselius-De Casparis et al23 (1968), Netherland | Osmotic vs Placebo |

|

3 wk | The only AEs sometimes observed was transient gas formation and intestinal bloating | Not described |

| Sanders24 (1978), USA | Osmotic vs Placebo |

|

12 wk |

|

10.6% (5/47) |

| Vanderdonckt et al25 (1990), Belgium | Osmotic vs Placebo |

|

4 wk | All reported adverse effects were abdominal symptoms, such as bloating and flatulence, compatible with the administration of a non-absorbable sugar | 8.7% (4/46) |

| Dipalma et al26 (2007), USA | Osmotic vs Placebo |

|

6 mo | No treatment emergent safety differences betweenPEG and placebo over the course of the 6-mo study except for gastrointestinal complaints (PEG 39.7%, placebo 25%)a Most of these events were mild or moderate. There were no clinically significant laboratory changes | 0.7% (2/306) (randomization error, noncompliance) |

| Lederle et al27 (1990), USA | Osmotic vs Osmotic |

|

4 wk | There were no significant differences between sorbitol and lactulose in any outcome measured except nausea, which increased with lactulosea | 3.2% (1/31 while receiving lactulose) |

| Seinelä et al28 (2009), Finland | Osmotic vs Osmotic |

|

4 wk |

|

|

| Chassagne et al29 (2017), France | Osmotic vs Osmotic |

|

6 mo |

|

|

| Stern 1966, USA | Stimulant vs Placebo |

|

3 wk | Watery stool in 1 treated patient (4%, 1/25) | Not described |

| Hyland and Foran30 (1968), UK | Softener vs Placebo |

|

4 wk | Not described | 13.0% (6/46, 5 unrelated deaths, 1 patient could not tolerate placebo tablet) |

| Fain et al31 (1978), USA | Softener vs Softener |

|

3 wk |

|

2.0% (1/47) |

| Inter-class comparisons | |||||

| Kinnunen and Salokannel32 (1987), Finland | Bulk vs Osmotic |

|

8 wk | Serum magnesium 2.92 mEq/L in a patient with impaired renal function and 2.74 mEq/L in a patient with normal creatinine but lowered creatinine clearance after the magnesium hydroxide treatment | 5.1% (3/59, 3 unable to swallow bulk laxative) |

| Kinnunen et al33 (1993), Finland | Bulk + Stimulant vs Osmotic |

|

5 wk | No adverse effects and changed in laboratory parameters in both treatments | 20.0% (6/30) (1 myocardial infarction, 1 fatal pneumonia in Agiolax group, 1 weakening of general condition and 1 ineffectiveness of medication in lactulose group, 2 referrals to other hospitals) |

| Passmore et al34 (1993), UK | Bulk+Stimulant vs Osmotic |

|

2 wk | 24 (31.2%) with Agiolax group and 21 (27.3%) with lactulose group (NS). Flatulence, urgency, and cramps were the most common AEs | 9.4% (8/85) (3 withdrawn after first treatment period, 3 unacceptable compliance, 1 deteriorating health, and 1 incomplete data) |

| Pers and Pers35 (1983), Sweden | Bulk + Stimulant vs Bulk + Stimulant |

|

2 wk | No AEs were seen with either of the preparations | 5.0% (1/20) (severe diarrhea not related with the medication) |

| Novel medications | |||||

| Camilleri et al36 (2009), USA and Belgium | Prucalopride vs Placebo |

|

4 wk |

|

A 22.2% (4/18, 2 other reason, 2 withdrawal of consent) B 14.3% (3/21, 3 due to AEs) C 12.5% (3/24, 1 due to AEs, 1 withdrawal of consent, 1 noncompliance) D 7.7% (2/26, 1 other reason, 1 withdrawal of consent) |

| Müller-Lissner et al37 (2010), Germany and Belgium | Prucalopride vs Placebo |

|

4 wk |

|

A 10.0% (7/70) B 9.2% (7/76) C 10.7% (8/75) D 13.9% (11/79) |

| Ueno et al38 (2006), USA | Lubiprostone vs Placebo |

|

4 wk |

|

Not identified |

| Nakajima et al39 (2019), Japan | Elobixibat vs Placebo |

|

52 wk |

|

Not identified |

| Menees et al40 (2020), USA | Plecanatide vs Placebo |

|

12 wk |

|

A 4.3%, B 6.7%, C 7.3% |

aP < 0.05.

bid, 2 times a day; qd, once a day; AEs, adverse effects; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; PEG, polyethylene glycol; mEq/L, milliequivalent per liter; QTc, corrected QT interval.

Quality Assessment of Included Studies

Of the 23 articles found in the literature search, 13 were parallel studies and 10 were cross-over design. For the parallel study, the quality was assessed using risk of bias recommended by the Cochrane collaboration and results are shown in Supplementary Figure. Two studies were not double blind studies.19,31 For the remaining double-blind studies, only about half of studies documented the details of the blind methods. In cases of randomization, only 4 studies described the detailed methods.26,29,37,39 The quality assessment of cross-over studies was based on the methods based on the Cochrane handbook and expert recommendations.17 The results of the quality assessment of the cross-over studies are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. The quality of most studies is considered moderate or low because they lacked a description of randomization and allocation concealment, did not evaluate the carry-over effects, and did not present and analyze the results of the first and second periods, respectively.

Randomized Controlled Trials Comparing Laxative With Placebo or Comparing Laxatives of Same Types

Bulk laxative

The literature search results showed that there were 4 studies comparing bulk laxatives (psyllium and bran) with placebo, and 1 comparing calcium polycarbophil with psyllium. Two studies which compared psyllium with placebo were cross-over designs and covered a small number of patients with fewer than 10 patients.18,21 Bowel movements per week tended to increase in the psyllium group, but was not statistically significant in 2 studies because of low statistical power due to small number of patients. Two studies with parallel design comparing bran with placebo showed similar results.19,20 Defecation frequency was not significantly different and the need for rescue medication in the bran group was not significantly decreased compared with the placebo group. However, bran improved consistency and overall symptoms. There was 1 study comparing bulk laxatives, which compared calcium polycarbophil 2 g per day and psyllium 9.5 g per day.22 The defecation frequency was slightly higher in the psyllium group, but not statistically significant, and the improvement of consistency and patient preference was significantly higher in the calcium polycarbophil group. Patients preferred polycarbophil as it produced less gas than psyllium.

Osmotic laxative

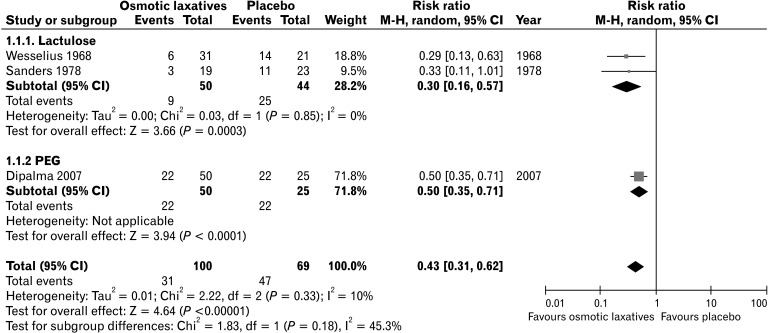

As a result of literature search, there were 4 studies comparing osmotic laxative with placebo, and 3 studies comparing 2 osmotic laxatives. In 2 RCTs, lactulose significantly increased the defecation frequency compared with placebo and significantly decreased the need for laxative use.23,24 Lactitol also significantly increased the number of defecations, improved stool consistency, and decreased laxative use compared with placebo.25 PEG also significantly increased the proportion of patients showing the relief of modified Rome criteria for constipation for 50% or more relative to placebo (difference of proportion 46%, P < 0.01).26 A forest plot showing the risk ratio of studies comparing osmotic laxatives and placebo is presented in Figure 2. In the comparison between osmotic laxatives, 2 studies comparing 2 osmotic laxatives (lactulose vs sorbitol, PEG 4000 without electrolyte vs PEG 4000 with electrolyte) showed no significant difference in terms of number of bowel movements and stool consistency.27,28 However, in a study comparing PEG 4000 and lactulose syrup for a 6-month duration, PEG 4000 resulted in significant increases of the number of defecations per week and more improved stool consistency compared with the lactulose syrup.29

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing risk ratio of studies comparing osmotic laxatives and placebo in the relief of constipation. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

Stimulant Laxative and Stool Softener

The literature search found 2 studies comparing stimulant laxative and placebo. However, the study by Marchesi et al was excluded because it was written in Italianand full-text could not be found as shown in Supplementary Table 1. Since cascarin was excluded from the Food and Drug Administration formulate lists in 2002, the study comparing cascarin with placebo was also excluded. No studies have compared bisacodyl to placebo in elderly patients with constipation.

There was one study comparing stool softener and placebo, using cross-over design and involving 40 elderly hospitalized patients by Hyland and Foran.30 Bowel movements per week in the stool softener group and placebo group were 3.3 and 2.5, respectively, which revealed difference of marginal degree (P = 0.060). However, overall symptom improvement was significantly greater in the dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (DSS) group. Other research compared 2 types of stool softener (DSS and dioctyl calcium sulfosuccinate [DCS]) and different doses of DSS.31 Only DCS preparation significantly increased the frequency of bowel movements than placebo. Similar to the study by Hyland and Foran,30 DSS showed no significant improvement in defecations compared to placebo.

Randomized Controlled Trials Comparing Different Types of Laxatives or Using Combination Agents

The characteristics of studies comparing different types of laxatives or studies comparing combination agents are summarized in Table 2. One study by Kinnunen and Salokannel32 compared bulk laxative with osmotic laxative, magnesium hydroxide. Magnesium hydroxide significantly increased the number of defecation per week (3.3 vs 2.6, P = 0.040), improved stool consistency score (1.0 vs 0.8, P < 0.01), and decreased the need for laxatives during 4 weeks (2.3 vs 3.3, P < 0.01) relative to bulk laxative.32

A comparison between Agiolax (Plantaginis ovata + isphagula husk + senna) and lactulose syrup was made in 2 studies. Agiolax significantly increased the number of defecations (4.5 vs 2.2, P < 0.05 in Kinnunen et al33 and 5.6 vs 4.2, P < 0.01 in Passmore et al34), and improved stool consistency. Both studies were cross-over designs and each medication was used for 2 weeks34 and 5 weeks.33 A study comparing the bulk and stimulant laxative mixtures showed that agents with higher senna content was more effective in increasing the frequency of bowel movements.35

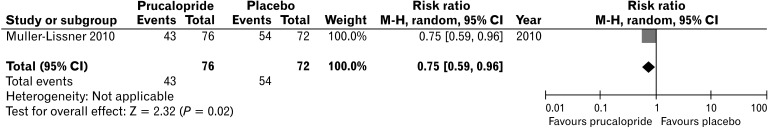

Randomized Controlled Trials Comparing Novel Medications With Placebo

Table 3 shows the characteristics of studies comparing novel medications with placebo. Other medications included prucalopride, lubiprostone, elobixibat, and plecanatide. Prucalopride is a selective agonist of serotonin (5-HT4) receptors and accelerates colon transit time. A clinical study which involved patients aged 65 years older showed that the percentage of patients who achieved ≥ 3 spontaneous complete bowel movements (SCBMs)/week was significantly higher in the prucalopride group compared with placebo group (26.1% in placebo group vs 42.1-48.7% in prucalopride group, P < 0.05).37 Spontaneous bowel movements (SBMs) per week also significantly increased in the prucalopride 1 mg group (4.5 to 6.9, P < 0.05). A forest plot showing the risk ratio of the study comparing prucalopride and placebo is presented in Figure 3. Lubiprostone and plecanatide are classified as secretagogues. Lubiprostone activates type 2 chloride channels on the apical membrane of epithelial cells, and plecanatide is guanylate cyclase C activators that induce fluid secretion into the GI tract via an increase in cyclic guanosine monophosphate.41 A study of lubiprostone in the elderly can be found in 1 conference abstract. In a pooled analysis of 3 clinical trials, lubiprostone significantly increased additional SBMs/week in constipated patients 65 years of age and older compared to placebo (4.6-5.4 vs 1.3-2.3, P < 0.05).38 In pooled analysis of 4 RCTs, plecanatide significantly increased SCBM and SBM in elderly patients.40 The recently developed ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT) inhibitor, elobixibat, has been shown to be effective in elderly patients in a subgroup analysis of RCT.39 Additional SBM increase per week was 6.0 (95% CI, 1.8-10.2) compared with placebo. However, the number of subjects was only 5 and 6 in placebo and elobixibat group, respectively.

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing risk ratio of studies comparing prucalopride and placebo in the relief of constipation. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Adverse Effects of Laxatives in Elderly From Randomized Controlled Trials

The frequency and types of AEs of each laxative are summarized in Table 4. Most studies reported AEs, but only 6 of 23 studies reported AEs using standardized techniques for assessing AEs by organs.26,28,29,36,37,39 Other studies have reported only common AEs. Bulk laxative had no clinical and laboratory AEs in the studies, except that it was difficult to swallow in 5.1% to 14.3% of patients.19,32 Magnesium hydroxide (82.5 mg/mL) with a dose of 25 mL/day had elevated the blood level of magnesium above the normal range in 2 patients when used in 64 elderly patients (3.1%) for 8 weeks.32 Both patients had abnormal renal function and no clinical symptoms associated with elevated blood magnesium were reported. For long-term use of PEG, treatment-related AEs over the course of 6 months was not different between PEG and placebo, except for GI complaints, such as flatulence and loose stool.26 Also, most of these GI AEs were mild to moderate. In a study of 6 months of long-term use of PEG and lactulose syrup, 11.5% of patients treated with lactulose syrup and 16.9% of patients with PEG showed potentially treatment-related AEs, which was not statistically different between the groups.29 Bronchitis (12.6%) and diarrhea (9.4%) were the first and second most common AEs in the lactulose group, respectively. Bronchitis (9.3%) and diarrhea (9.3%) were most common AEs which were followed by abdominal pain (7.6%) in the PEG group. AEs leading to drug discontinuation were 8 cases (6.3%) in the lactulose group and 3 cases (2.5%) in the PEG group, which was not significantly different. One study comparing PEG without electrolyte (hypotonic PEG) and PEG with electrolyte (isotonic PEG) in the elderly for 4 weeks showed significant difference of plasma sodium levels between the groups (137.7 milliequivalent/L in PEG without electrolyte vs 138.9 milliequivalent/L in PEG with electrolyte, P = 0.010). However, none of these showed any clinical significant symptoms and did not require any interventions.

In 2 studies using prucalopride for 4 weeks, there was no significant difference between the severe AE and discontinuation of treatment due to AEs in the prucalopride group and placebo group. For cardiovascular safety, there was no difference in the frequency of corrected QT interval prolongation (defined as > 450 msec in men and > 470 msec in women) on electrocardiogram (ECG) and in the significant arrhythmia in 24-hour Holter monitoring.36 Lubiprostone showed less frequent AEs than placebo during the 4-week study period (46.2% [12/26] in the lubiprostone group vs 61.3% [19/31] in placebo group, P < 0.05).38 However, there were no reports on frequency of AEs according to the organ system, serious AEs, and discontinuation due to AEs of lubiprostone. In the long-term study of elobixibat for 52 weeks, the incidence of AEs in patients 65 years and older was 12.0% diarrhea and 4.0% abdominal pain.39 It was remarkable that the frequency of abdominal pain was significantly lower than in patients under 65 years of age. However, the number of elderly patients over 65 years was relatively small (n = 26) in this long-term follow-up study.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we have found that many laxatives are effective in alleviating constipation in elderly patients, especially recently developed medications. Although the number of RCTs on the effects of laxatives in elderly constipation patients were not small, the following limitations were observed to produce recommendations with a high level of evidence. Study design, definition of constipation, and outcome measures were heterogeneous among studies. The quality of most studies was not high. Sample sizes were small. Treatment duration was usually short.

Bulk laxatives contain fiber and increase the weight and water-absorbent properties of the stool.42 In elderly patients, there were 4 placebo-controlled trials in bulk laxatives, 2 using psyllium and 2 using bran. Psyllium significantly decreased the total gut transit time and improved stool consistency in 10 elderly patients.21 However, RCTs with psyllium or bran did not show significant increases in the number of bowel movements or decreased the use of laxatives. Since all 4 studies were conducted in a small number of patients less than 20 in each group, the statistical power to detect the difference may be low. In a systematic review which analyzed the effect of fiber in chronic constipation performed by American College of Gastroenterology, it was concluded that psyllium was the only a fiber agent with sufficient clinical evidences. There was insufficient evidence with other fiber formulations such as calcium polycarbophil, methylcellulose, and bran.43 In a study comparing calcium polycarbophil and psyllium by Chokhavatia et al,22 the effects of the 2 drugs were similar, but many patients showed a preference for calcium polycarbophil because they produced less gas. Psyllium is classified as a soluble intermediate fermentable fiber, and calcium polycarbophil is an insoluble and non-fermentable fiber.44 Because the colon transit time in the elderly is much longer in the elderly than that in younger adults, even an intermediate fermentable fiber can cause flatulence. Therefore, when using fiber for the elderly with constipation, it is recommended to remove the hard stool with other laxative first and then use a fiber with small dose.45

When compared with osmotic laxatives, bulk laxative was inferior to magnesium hydroxide in terms of bowel movement frequency and improvement in consistency in elderly patients. A study in the general adult population has shown similar results. In a RCT with adult constipated patients, PEG with electrolytes was more effective at increasing the number of bowel movements than psyllium.46 Regarding the side effects, bulk laxative was reported to be generally well-tolerated although there were a few RCTs that reported AEs systematically. However, in 5-16% of patients, difficulty in swallowing bulk laxative led to a withdrawal from the study. In the recent consensus report of elderly constipation patients, fiber is considered as a primary treatment in general, but syrup-type osmotic laxative is recommended first if swallowing difficulty is present.11

All 3 RCTs comparing osmotic laxatives and placebo showed that osmotic laxative was effective in increasing defecation frequency and improving consistency. In comparison between osmotic laxatives, the efficacies of lactulose syrup and sorbitol (lactitol) were similar. However, in a 6-month study comparing PEG and lactulose, PEG was more effective in alleviating constipation symptoms than lactulose, and the frequency of AEs was not different between the 2 groups. In a network meta-analysis study of the effects of PEG published in 2016, PEG and PEG with electrolyte increased bowel movement 1.8 (95% CI, 0.0-3.5) and 1.9 (95% CI, 0.2-3.6) fold, respectively compared to lactulose.47 In terms of safety, a study using PEG and lactulose in the elderly for 6 months revealed that 12.6% of patients (16/127) in the lactulose group and 19.5% (23/118) in the PEG group showed serious AEs, none of which were considered treatment related. AEs that led to permanent drug discontinuation presented in 6.3% and 2.5% of patients in lactulose group and PEG group, respectively. This study indicated that long-term use of PEG and lactulose about 6 months is considered to be relatively safe in elderly constipation patients. Most guidelines suggest that osmotic laxative is second only to the use of fibers because it is effective, has fewer side effects, and is cheap, which can also be thought as same recommendation for older patients.48-50 In some guidelines, PEG is preferred over lactulose within osmotic laxatives.51 One thing to note in osmotic laxatives is that there was an increase in blood magnesium level in 5.6% (2/36) patients using magnesium hydroxide, all of whom had abnormal renal function. Although there were no symptoms associated with hypermagnesemia, magnesium levels should be monitored periodically when using in elderly patients with impaired renal function.

Prucalopride is the highly selective serotonin (5-HT4) receptor agonist. Large scale RCTs showed that prucalopride treatment resulted in ≥ 3 SCBM per week in 30.9% of those receiving 2 mg of prucalopride as compared with 12.0% in the placebo group (P < 0.01).52 In a study that collected all 2484 subjects from 6 RCTs using prucalopride, significantly more patients achieved a mean of ≥ 3 SCBM per week over 12 weeks of treatment in the prucalopride group (27.8%) than in the placebo group (13.2%; OR, 2.68 [95% CI, 2.16-3.33]).53 In this analysis, there were 374 elderly patients over 65 years of age (15.4%), the effect of prucalopride in elderly group was not analyzed separately. As a result of literature search, there were 2 RCTs for elderly constipated people over 65 years old. One study was only for analysis of AEs, especially cardiovascular AEs, and the other analyzed the efficacy in constipation. The latter study showed that prucalopride increased bowel movements per week significantly. The effect was largest and significant during the first week of treatment. Regarding the safety of prucalopride in elderly patients, the incidence of treatment-emergent AEs in the treatment group was similar to the incidence in the placebo group. The most frequent AEs of prucalopride were headaches and GI events including abdominal pain, diarrhea, and nausea. Relative to placebo, there were no differences in ECG QTc, ECG morphology parameters, or incidence of supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmias on Holter monitoring. Effectiveness and safety of prucalopride in elderly constipation patients has been demonstrated by 2 well-designed RCTs, although they were short-term studies of less than 4 weeks and the number of subjects in studies was not large. Pruclopride can be recommended in elderly patients who do not satisfactorily respond to fiber, osmotic laxatives, and stimulant laxatives, as suggested in a recent guideline.11

Chloride channel activators stimulate intestinal fluid secretion without increasing serum electrolyte levels.42 Lubiprostone which is the first chloride change activator approved in the United States significantly improved the severity of constipation and stool consistency shown in meta-analyses of data from 9 trials.54 Nausea and diarrhea were more common in the lubiprostone group (both 14.5%) compared with placebo group (1.6% and 0.0%, respectively) in RCT performed in Japan (P < 0.02).55 Effectiveness and safety in elderly patients were shown only in 2 conference abstracts. Lubiprstone treatment significantly increased bowel movements and improved stool consistency relative to placebo. Unlike RCTs in adult patients, the incidence of AEs did not differ between the 2 groups. However, this study involved only 57 subjects (26 in lubiprostone group and 31 in placebo group) and duration of study was less than 4 weeks. For strong recommendation in older constipation patients, more studies involving large number of subjects are necessary, and if used, it seems necessary monitor the occurrence of GI AEs such as nausea.

Linaclotide and plecanatide are minimally absorbed peptide agonists of the guanylate cyclase-C receptor that stimulates intestinal fluid secretion and transit.56 Linaclotide significantly increased bowel movement in 2 trials with different duration (4 weeks and 12 weeks) and the incidence of AEs was similar between the study groups, with the exception of diarrhea.57,58 In a RCT with 12 weeks duration, the number of elderly patients aged 65 years or older was 13.0% (55/424). However, the effects and AEs in older patients were not analyzed separately by subgroup analysis. In contrast, in the case of plecanatide, a separate analysis of the elderly showed that CSBM was significantly increased at a dose of 3 mg. Common AEs included diarrhea, headache, and arthralgia. Unlike younger patients, the 6 mg dose appears to be ineffective, so low dose administration seems effective and safe for elderly patients.

Elobixibat is a locally acting IBAT inhibitor and have shown to be effective in constipation compared with placebo in a 2-week randomized trial.59 Abdominal pain and diarrhea was more frequent in the elobixibat group than placebo, but the majority of the GI AEs were mild (95.0%). In this review, post-hoc analysis of this RCT and long-term open label trial was included. Elobixibat was effective in alleviating symptoms in elderly patients as in younger patients, with fewer AEs in elderly patients. However, the number of elderly patients included in this study was only 11 (5 in placebo and 6 in elobixibat), and the duration of treatment was 2 weeks, which seems insufficient as an evidence for recommending elobixibat in elderly patients.

The quality of studies was assessed using the risk of bias by the Cochrane collaboration for the study of parallel design and the quality assessment standard of cross-over study suggested by the Cochrane handbook for the study of cross-over design. This review included 3 studies from the 1960s, 2 studies from the 1970s, and 6 studies from the 1980s. The quality of these older studies was moderate to low when using the current rigorous standards. The quality of RCTs has steadily improved over time, adopting evidence-based approaches such as the Consolidated Standards for Reporting of Trials (CONSORT) statement.60 Most of the cross-over studies included in this review did not seem to perform well with allocation concealment and blinding, and poorly evaluate the carry-over effects. It is well known that allocation bias can result in a 13.0% increased estimate of benefit in the treatment group when compared to other trials that used appropriate allocation concealment.61 Among the laxatives included in this review, PEG and prucalopride have demonstrated their effectiveness and safety by high-quality RCTs targeting a relatively large number of elderly patients.26,28,29,36,37 In particular, PEG may be recommended on a high level of evidence as 2 RCTs have showed effectiveness and safety in 6 months of relatively long-term use.26,29

Some limitations need to be mentioned. First, as there many old studies from the literature search, there were 3 studies where full-text was not available. During full-text review, there were 3 studies that cannot be interpreted in English, so the results of these studies were not reflected in the results. However, since these studies are usually old studies with small number of patients and studies of laxatives such as herbal medications, they may not have had a significant influence on the review results. Second, as pointed earlier, there were not many high quality studies, especially long-term follow-up studies. Long-term, well-designed RCTs involving more patients are needed for recommendations in the treatment of elderly constipation patients with high quality of evidence. Third, bisacodyl is a very commonly used stimulant laxative, but there has been no studies in elderly patients. There are few studies on bisacodyl, but most guidelines recommend that it can be used if there is no response to the treatment of bulk laxative or osmotic laxative.43,62 However, it is recommended to use it for a short period of time within several months, as there is a risk of causing loss of water and electrolytes, steatorrhea, and protein-losing enteropathy when used for a long period of time.62 Lastly, types of patient population (long-term care setting, hospitalized setting, and community setting), constipation definition, and the endpoint of study were all heterogeneous. Therefore, it was not possible to apply techniques such as network meta-analysis to compare the effectiveness of laxatives.

From the review of 23 RCTs, bulk laxative, osmotic laxative, stimulant laxative, and other medications such as prucalopride, lubiprostone, and elobixibat were more effective than placebo in the elderly constipation patients in short-term with reasonable safety. However, the quality of studies was not high and most of studies was conducted in a small number of patients. Among these laxatives, PEG seems to be safe and effective in long-term use of about 6 months in elderly patients.

Supplementary Materials

Note: To access the supplementary tables and figure mentioned in this article, visit the online version of Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility at http://www.jnmjournal.org/, and at https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm20210.

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

Conflicts of interest: None.

Author contributions: Seung Joo Kang and Young Sin Cho: collecting data and drafting the manuscript; Tae Hee Lee, Seong-Eun Kim, Seon-Young Park, and Yoo Jin Lee: interpreting data and revising the article; Han Seung Ryu: supervising analysis and revising articles; Jung-Wook Kim: collecting data and revising the article; and Jeong Eun Shin: designing research.

References

- 1.Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:750–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talley NJ, O'Keefe EA, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:895–901. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90175-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wald A, Scarpignato C, Mueller-Lissner S, et al. A multinational survey of prevalence and patterns of laxative use among adults with self-defined constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:917–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donald IP, Smith RG, Cruikshank JG, Elton RA, Stoddart ME. A study of constipation in the elderly living at home. Gerontology. 1985;31:112–118. doi: 10.1159/000212689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamura A, Tomita T, Oshima T, et al. Prevalence and self-recognition of chronic constipation: results of an internet survey. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:677–685. doi: 10.5056/jnm15187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vazquez Roque M, Bouras EP. Epidemiology and management of chronic constipation in elderly patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:919–930. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S54304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruby CM, Fillenbaum GG, Kuchibhatla MN, Hanlon JT. Laxative use in the community-dwelling elderly. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2003;1:11–17. doi: 10.1016/S1543-5946(03)80012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harari D, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, Choodnovskiy I, Minaker KL. Constipation: assessment and management in an institutionalized elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:947–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitehead WE, Drinkwater D, Cheskin LJ, Heller LJ, Schuster MM. Constipation in the elderly living at home. Definition, prevalence, and relationship to lifestyle and health status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:423–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb02638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Keefe EA, Talley NJ, Tangalos EG, Zinsmeister AR. A bowel symptom questionnaire for the elderly. J Gerontol. 1992;47:M116–M121. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.4.M116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emmanuel A, Mattace-Raso F, Neri MC, Peterson KU, Rey E, Rogers J. Constipation in older people: a consensus statement. Int J Clin Pract. 2017;71:e12920. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennison C, Prasad M, Lloyd A, et al. The health-related quality of life and economic burden of constipation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:461–476. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:599–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleming V, Wade WE. A review of laxative therapies for treatment of chronic constipation in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8:514–550. doi: 10.1016/S1543-5946(10)80003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:ED000142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding H, Hu GL, Zheng XY, Chen Q, Threapleton DE, Zhou ZH. The method quality of cross-over studies involved in cochrane systematic reviews. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ewerth S, Ahlberg J, Holmström B, Persson U, Udén R. Influence on symptoms and transit-time of Vi-SiblinR in diverticular disease. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1980;500:49–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finlay M. The use of dietary fibre in a long-stay geriatric ward. J Nutr Elder. 1988;8:19–30. doi: 10.1300/J052v08n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajala SA, Salminen SJ, Seppänen JH, Vapaatalo H. Treatment of chronic constipation with lactitol sweetened yoghurt supplemented with guar gum and wheat bran in elderly hospital in-patients. Compr Gerontol A. 1988;2:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheskin LJ, Kamal N, Crowell MD, Schuster MM, Whitehead WE. Mechanisms of constipation in older persons and effects of fiber compared with placebo. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:666–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chokhavatia S, Phipps T, Anuras S. Comparative laxation of calcium polycarbophil with psyllium mucilloid in an ambulatory geriatric population. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1988;44:1013–1019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wesselius-De Casparis A, Braadbaart S, Bergh-Bohlken GE, Mimica M. Treatment of chronic constipation with lactulose syrup: results of a double-blind study. Gut. 1968;9:84–86. doi: 10.1136/gut.9.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanders JF. Lactulose syrup assessed in a double-blind study of elderly constipated patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1978;26:236–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1978.tb01967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanderdonckt J, Coulon J, Denys W, Ravelli GP. Study of the laxative effect of lactitol (importalr) in an elderly institutionalized, but not bedridden, population suffering from chronic constipation. J Clin Exp Gerontol. 1990;12:171–189. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dipalma JA, Cleveland MV, McGowan J, Herrera JL. A randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of polyethylene glycol laxative for chronic treatment of chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1436–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lederle FA, Busch DL, Mattox KM, West MJ, Aske DM. Cost-effective treatment of constipation in the elderly: a randomized double-blind comparison of sorbitol and lactulose. Am J Med. 1990;89:597–601. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90177-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seinelä L, Sairanen U, Laine T, Kurl S, Pettersson T, Happonen P. Comparison of polyethylene glycol with and without electrolytes in the treatment of constipation in elderly institutionalized patients: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:703–713. doi: 10.2165/11316470-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chassagne P, Ducrotte P, Garnier P, Mathiex-Fortunet H. Tolerance and long-term efficacy of polyethylene glycol 4000 (Forlax®) compared to lactulose in elderly patients with chronic constipation. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21:429–439. doi: 10.1007/s12603-016-0762-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyland CM, Foran JD. Dioctyl sodium sulphosuccinate as a laxative in the elderly. Practitioner. 1968;200:698–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fain AM, Susat R, Herring M, Dorton K. Treatment of constipation in geriatric and chronically ill patients: a comparison. South Med J. 1978;71:677–680. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197806000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinnunen O, Salokannel J. Constipation in elderly long-stay patients: its treatment by magnesium hydroxide and bulk-laxative. Ann Clin Res. 1987;19:321–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinnunen O, Winblad I, Koistinen P, SaloKannel J. Safety and efficacy of a bulk laxative containing senna versus lactulose in the treatment of chronic constipation in geriatric patients. Pharmacology. 1993;47(suppl 1):253–255. doi: 10.1159/000139866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Passmore AP, Wilson-Davies K, Stoker C, Scott ME. Chronic constipation in long stay elderly patients: a comparison of lactulose and a senna-fibre combination. BMJ. 1993;307:769–771. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6907.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pers M, Pers B. A crossover comparative study with two bulk laxatives. J Int Med Res. 1983;11:51–53. doi: 10.1177/030006058301100111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Camilleri M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Robinson R, Vandeplassche L. Safety assessment of prucalopride in elderly patients with constipation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:1256–e117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Müller-Lissner S, Rykx A, Kerstens R, Vandeplassche L. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of prucalopride in elderly patients with chronic constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:991–998. e255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ueno R, Joswick TR, Wahle A, et al. Efficacy and safety of lubiprostone for the treatment of chronic constipation in elderly vs non-elderly subjects. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:A189. doi: 10.14309/00000434-200609001-01273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakajima A, Taniguchi S, Kurosu S, Gillberg PG, Mattsson JP, Camilleri M. Efficacy, long-term safety, and impact on quality of life of elobixibat in more severe constipation: post hoc analyses of two phase 3 trials in Japan. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31:e13571. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menees SB, Franklin H, Chey WD. Evaluation of plecanatide for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome with constipation in patients 65 years or older. Clin Ther. 2020;42:1406–1414. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bharucha AE, Lacy BE. Mechanisms, evaluation, and management of chronic constipation. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1232–1249. e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tack J, Müller-Lissner S. Treatment of chronic constipation: current pharmacologic approaches and future directions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:502–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force, author. An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(suppl 1):S1–S4. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50613_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eswaran S, Muir J, Chey WD. Fiber and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:718–727. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McRorie JW., Jr Evidence-based approach to fiber supplements and clinically meaningful health benefits, part 2: what to look for and how to recommend an effective fiber therapy. Nutr Today. 2015;50:90–97. doi: 10.1097/NT.0000000000000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang HJ, Liang XM, Yu ZL, Zhou LY, Lin SR, Geraint M. A randomised, controlled comparison of low-dose polyethylene glycol 3350 plus electrolytes with ispaghula husk in the treatment of adults with chronic functional constipation. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24:569–576. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200424100-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katelaris P, Naganathan V, Liu K, Krassas G, Gullotta J. Comparison of the effectiveness of polyethylene glycol with and without electrolytes in constipation: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:42. doi: 10.1186/s12876-016-0457-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bharucha AE, Dorn SD, Lembo A, Pressman A American Gastroenterological Association, author. American gastroenterological association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:211–217. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shin JE, Jung HK, Lee TH, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic functional constipation in Korea, 2015 revised edition. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:383–411. doi: 10.5056/jnm15185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Serra J, Pohl D, Azpiroz F, et al. European society of neurogastroenterology and motility guidelines on functional constipation in adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32:e13762. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mounsey A, Raleigh M, Wilson A. Management of constipation in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92:500–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, Vandeplassche L. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2344–2354. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Camilleri M, Piessevaux H, Yiannakou Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of prucalopride in chronic constipation: an integrated analysis of six randomized, controlled clinical trials. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:2357–2372. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4147-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li F, Fu T, Tong WD, et al. Lubiprostone is effective in the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:456–468. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fukudo S, Hongo M, Kaneko H, Takano M, Ueno R. Lubiprostone increases spontaneous bowel movement frequency and quality of life in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:294–301. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eswaran S, Guentner A, Chey WD. Emerging pharmacologic therapies for constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipation. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:141–151. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2014.20.2.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lembo AJ, Kurtz CB, Macdougall JE, et al. Efficacy of linaclotide for patients with chronic constipation. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:886–895. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lembo AJ, Schneier HA, Shiff SJ, et al. Two randomized trials of linaclotide for chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:527–536. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakajima A, Seki M, Taniguchi S, et al. Safety and efficacy of elobixibat for chronic constipation: results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial and an open-label, single-arm, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:537–547. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L. Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials: a comparative before-and-after evaluation. JAMA. 2001;285:1992–1995. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Savovic J, Turner RM, Mawdsley D, et al. Association between risk-of-bias assessments and results of randomized trials in cochrane reviews: the ROBES meta-epidemiologic study. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187:1113–1122. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim SJ, Park KS. [Pharmacotherapy in patients with chronic constipation]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2017;70:64–71. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2017.70.2.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.