Abstract

Background

Stroke can affect people’s ability to swallow, resulting in passage of some food and drink into the airway. This can cause choking, chest infection, malnutrition and dehydration, reduced rehabilitation, increased risk of anxiety and depression, longer hospital stay, increased likelihood of discharge to a care home, and increased risk of death. Early identification and management of disordered swallowing reduces risk of these difficulties.

Objectives

Primary objective

• To determine the diagnostic accuracy and the sensitivity and specificity of bedside screening tests for detecting risk of aspiration associated with dysphagia in people with acute stroke

Secondary objectives

• To assess the influence of the following sources of heterogeneity on the diagnostic accuracy of bedside screening tools for dysphagia

‐ Patient demographics (e.g. age, gender)

‐ Time post stroke that the study was conducted (from admission to 48 hours) to ensure only hyperacute and acute stroke swallow screening tools are identified

‐ Definition of dysphagia used by the study

‐ Level of training of nursing staff (both grade and training in the screening tool)

‐ Low‐quality studies identified from the methodological quality checklist

‐ Type and threshold of index test

‐ Type of reference test

Search methods

In June 2017 and December 2019, we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database via the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; the reference lists of included studies; and grey literature sources. We contacted experts in the field to identify any ongoing studies and those potentially missed by the search strategy.

Selection criteria

We included studies that were single‐gate or two‐gate studies comparing a bedside screening tool administered by nurses or other healthcare professionals (HCPs) with expert or instrumental assessment for detection of aspiration associated with dysphagia in adults with acute stroke admitted to hospital.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened each study using the eligibility criteria and then extracted data, including the sensitivity and specificity of each index test against the reference test. A third review author was available at each stage to settle disagreements. The methodological quality of each study was assessed using the Quality Assessment of Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy (QUADAS‐2) tool. We identified insufficient studies for each index test, so we performed no meta‐analysis. Diagnostic accuracy data were presented as sensitivities and specificities for the index tests.

Main results

Overall, we included 25 studies in the review, four of which we included as narratives (with no accuracy statistics reported). The included studies involved 3953 participants and 37 screening tests. Of these, 24 screening tests used water only, six used water and other consistencies, and seven used other methods. For index tests using water only, sensitivity and specificity ranged from 46% to 100% and from 43% to 100%, respectively; for those using water and other consistencies, sensitivity and specificity ranged from 75% to 100% and from 69% to 90%, respectively; and for those using other methods, sensitivity and specificity ranged from 29% to 100% and from 39% to 86%, respectively. Twenty screening tests used expert assessment or the Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability (MASA) as the reference, six used fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), and 11 used videofluoroscopy (VF). Fifteen screening tools had an outcome of aspiration risk, 20 screening tools had an outcome of dysphagia, and two narrative papers did not report the outcome. Twenty‐one screening tests were carried out by nurses, and 16 were carried out by other HCPs (not including speech and language therapists (SLTs)).

We assessed a total of six studies as low risk across all four QUADAS‐2 risk of bias domains, and we rated 15 studies as low concern across all three applicability domains.

No single study demonstrated 100% sensitivity and specificity with low risk of bias for all domains. The best performing combined water swallow and instrumental tool was the Bedside Aspiration test (n = 50), the best performing water plus other consistencies tool was the Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS; n = 30), and the best water only swallow screening tool was the Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test (TOR‐BSST; n = 24). All tools demonstrated combined highest sensitivity and specificity and low risk of bias for all domains. However, clinicians should be cautious in their interpretation of these findings, as these tests are based on single studies with small sample sizes, which limits the estimates of reliability of screening tests.

Authors' conclusions

We were unable to identify a single swallow screening tool with high and precisely estimated sensitivity and specificity based on at least one trial with low risk of bias. However, we were able to offer recommendations for further high‐quality studies that are needed to improve the accuracy and clinical utility of bedside screening tools.

Plain language summary

Screening for aspiration risk associated with dysphagia in acute stroke

Question

How accurate are swallow screening tools for detecting when food and drink enter the airway in people with acute stroke?

Background

Stroke often affects a person’s ability to swallow, allowing food and drink into the airway. This can cause choking, chest infection, malnutrition, dehydration, and reduced rehabilitation, with increased risk of anxiety, depression, discharge to a care home, and death. Early identification and management of disordered swallowing through the most accurate testing reduces these risks. If the test fails to identify swallowing difficulties, the person will continue oral intake and may experience the difficulties identified above. If the test incorrectly identifies swallowing difficulties, the person may not be given anything to eat or drink, significantly impacting quality of life, until a more detailed assessment is undertaken (usually the next day).

Study characteristics

We identified 25 studies that used a total of 37 tools. Seven tools did not use water or other consistencies, 24 used only water, and six considered water and other consistencies.

Key results

We were unable to identify a tool that could accurately identify everyone with food and drink entering their airway, as well as detect all those who definitely did not. Many studies involved different healthcare professionals, food and fluid testing consistencies, and time between stroke onset and the screening test, so it is unclear which tool is best. We were unable to directly compare the different tools because most studies used different methods.

We were able to identify the tools most able to detect people with and without risk of swallowing difficulties from studies with good quality evidence. The best combined water swallow and instrumental test was the Bedside Aspiration test, the best water plus other consistencies tool was the Gugging Swallowing Screen, and the best water only tool was the Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test. However, clinicians should be cautious in their interpretation of these findings, as these tests are based on single studies with small sample sizes.

Quality of the evidence

Most included studies were poorly conducted or were unclear in reporting what they did (i.e. unclear or high risk of bias).

Conclusion

We were unable to identify a single tool with combined high levels of accuracy and good quality evidence. However, we are able to offer recommendations for further high‐quality studies that are needed to improve the accuracy and clinical utility of swallow screening tools.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Review criteria and findings.

| Review question | What is the diagnostic accuracy of screening tools for aspiration risk associated with dysphagia in acute stroke? |

| Importance | A simple and reliable screening tool for identification of aspiration associated with dysphagia would reduce diagnostic delay and the risk of developing pneumonia in acute stroke patients |

| Patients/population | Patients (over the age of 18) who have been admitted to an acute hospital setting, where there is a clinical diagnosis of stroke. Patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage were excluded from the study |

| Settings | Stroke units or hospital wards where acute stroke patients are admitted |

| Index tests | Bedside swallowing screening tools carried out by healthcare professionals (excluding SLTs) |

| Reference standards | Expert assessment, including the MASA VF FEES |

| Studies | 25 studies were included, 4 of which are presented as narratives (with no accuracy statistics reported). The included studies reported 37 screening tests |

| Risk of bias | Overall judgement: poor quality for the majority of studies – only 6 studies were at low risk across all 4 risk of bias domains, and 2 studies were at low risk of bias for 3 domains |

| Patient selection bias: high risk = 12 studies; unclear risk = 11 studies; low risk = 2 studies | |

| Index test interpretation bias: high risk = 14 studies; unclear risk = 10 studies; low risk = 1 study | |

| Reference standard interpretation bias: high risk = 16 studies; unclear risk = 8 studies; low risk = 1 study | |

| Flow and timing selection bias: high risk = 13 studies; unclear risk = 6 studies; low risk = 6 studies | |

| Applicability concern | Concerns regarding patient selection: high risk = 16 studies; unclear risk = 4 studies; low risk = 5 studies |

| Concerns regarding index test: high risk = 20 studies; unclear risk = 4 studies; low risk = 1 study | |

| Concerns regarding reference standard: high risk = 22 studies; unclear risk = 3 studies; low risk = 0 studies | |

| Overall findings | The best performing swallow screening tools were the Combined WST and Oxygen Saturation Test (Lim 2001a), GUSS (Trapl 2007b), and TOR‐BSST (Martino 2009). The best water only swallow screening test was the TOR‐BSST (Martino 2009). All demonstrate a combined highest sensitivity and specificity and low risk of bias across all domains. These tools may be considered useful in clinical practice |

| The water plus various consistencies (n = 6) performed better than the water‐only tools in terms of sensitivity and specificity | |

| Only a few studies (e.g. GUSS) (Trapl 2007b) gave direction on what food and drink consistencies should be given to an individual following the screen | |

| The quality of evidence varied. Studies often failed to distinguish between dysphagia and aspiration as the primary outcome. Some did not identify the time interval between stroke onset or admission to hospital and the screen, or the time interval between index test and reference test. Training required by different healthcare professionals to implement the screening tool was not reported well. This has implications for future research |

FEES: fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing. MASA: Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability. SLT: speech and language therapist. VF: videofluoroscopy. WST: water‐swallowing test.

Summary of findings 2. Screening tests.

| Screening test | N participants (studies) | Reference standard | Diagnostic estimates (95% CI) | Implications |

| Water‐only tests | 2914 (13) | |||

| Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test (TOR‐BSST): Martino 2009 Study 1 | 24 (1) | VFSS | Sens = 1.00 (0.75 to 1.00) spec = 0.64 (0.31 to 0.89) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

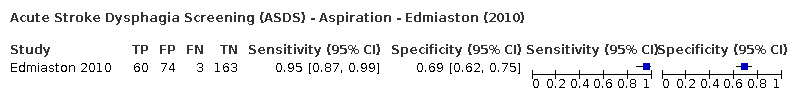

| Acute Stroke Dysphagia Screening (ASDS) Aspiration: Edmiaston 2010 | 300 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.95 (0.87 to 0.99) spec = 0.69 (0.62 to 0.75) | Large study with unclear risk of bias and low applicability concerns |

| Barnes‐Jewish Hospital‐Stroke Dysphagia Screen (BJH‐SDS) Aspiration: Edmiaston 2014 | 223 (1) | VFSS | Sens = 0.95 (0.86 to 0.99) spec = 0.50 (0.42 to 0.58) | Large study with unclear/low risk of bias and low applicability concerns |

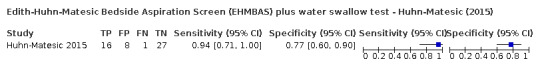

| Edith‐Huhn‐Matesic Bedside Aspiration Screen (EHMBAS) followed by simple water swallow test: Huhn‐Matesic 2015 | 52 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.94 (0.71 to 1.00) spec = 0.77 (0.60 to 0.90) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

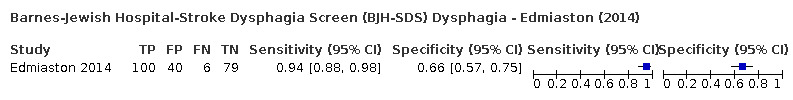

| Barnes‐Jewish Hospital‐Stroke Dysphagia Screen (BJH‐SDS) Dysphagia: Edmiaston 2014 | 225 (1) | VFSS | Sens = 0.94 (0.88 to 0.98) spec = 0.66 (0.57 to 0.75) | Large study with low risk of bias and low applicability concerns. |

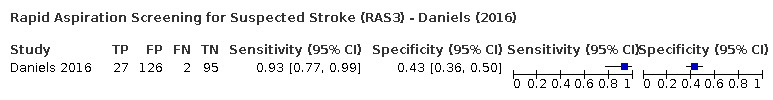

| Rapid Aspiration Screening for Suspected Stroke (RAS3): Daniels 2016 | 250 (1) | VFSS | Sens = 0.93 (0.77 to 0.99) spec = 0.43 (0.36 to 0.50) | Large study with low risk of bias and low applicability concerns. |

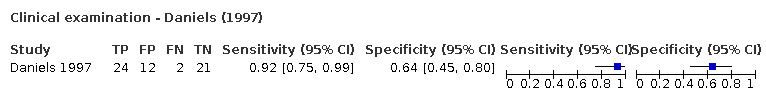

| Clinical examination: Daniels 1997 | 59 (1) | VFSS | Sens = 0.92 (0.75 to 0.99) spec = 0.64 (0.45 to 0.80) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

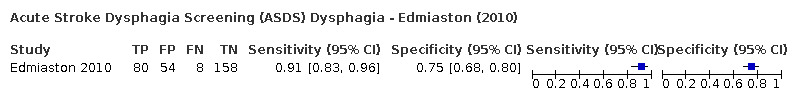

| Acute Stroke Dysphagia Screening (ASDS) Dysphagia: Edmiaston 2010 | 300 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.91 (0.83 to 0.96) spec = 0.75 (0.68 to 0.80) | Large study with unclear risk of bias and low applicability concerns |

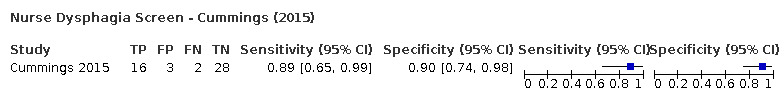

| Nurse Dysphagia Screen: Cummings 2015 | 49 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.89 (0.65 to 0.99) spec = 0.90 (0.74 to 0.98) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

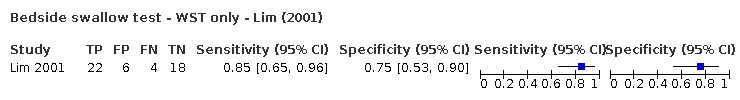

| Bedside swallow test ‐ WST only: Lim 2001 | 50 (1) | FEES | Sens = 0.85 (0.65 to 0.96) spec = 0.75 (0.53 to 0.90) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

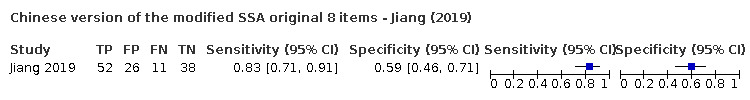

| Chinese version of the modified SSA – original 8 items: Jiang 2019 | 127 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.83 (0.71 to 0.91) spec = 0.59 (0.46 to 0.71) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

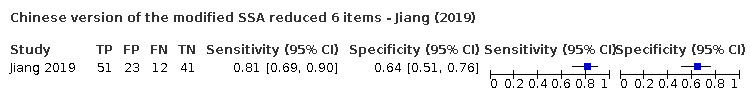

| Chinese version of the modified SSA – reduced 6 items: Jiang 2019 | 127 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.81 (0.69 to 0.90) spec = 0.64 (0.51 to 0.76) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

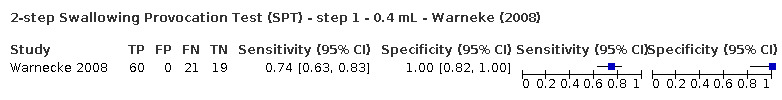

| 2‐step swallowing provocation test (SPT) ‐ step 1 ‐ 0.4 mL: Warnecke 2008 | 100 (1) | FEES | Sens = 0.74 (0.63 to 0.83) spec = 1.00 (0.82 to 1.00) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

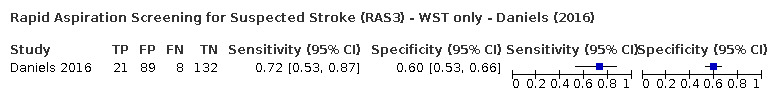

| Rapid Aspiration Screening for Suspected Stroke (RAS3) ‐ WST only: Daniels 2016 | 250 (1) | VFSS | Sens = 0.72 (0.53 to 0.87) spec = 0.60 (0.53 to 0.66) | Large study with low risk of bias and low applicability concerns. |

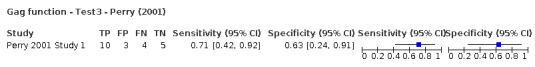

| Gag function ‐ Test3: Perry 2001 Study 1 | 22 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.71 (0.42 to 0.92) spec = 0.63 (0.24 to 0.91) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

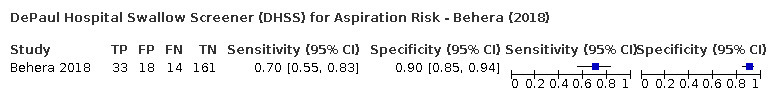

| DePaul Hospital Swallow Screener (DHSS) Aspiration: Behera 2018 | 226 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.70 (0.55 to 0.83) spec = 0.90 (0.85 to 0.94) | Large study with unclear risk of bias and unclear applicability concerns |

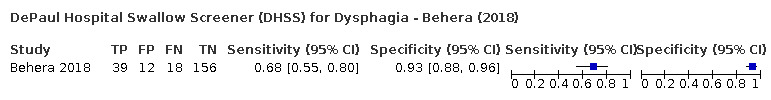

| DePaul Hospital Swallow Screener (DHSS) Dysphagia: Behera 2018 | 225 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.68 (0.55 to 0.80) spec = 0.93 (0.88 to 0.96) | Large study with unclear risk of bias and unclear applicability concerns |

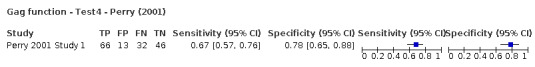

| Gag function ‐ Test4: Perry 2001 Study 1 | 157 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.67 (0.57 to 0.76) spec = 0.78 (0.65 to 0.88) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

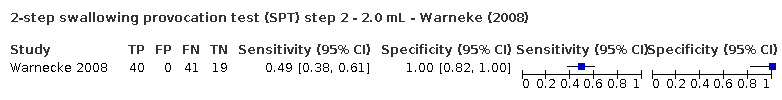

| 2‐step swallowing provocation test (SPT) ‐ step 2 ‐ 2.0 mL: Warnecke 2008 | 100 (1) | FEES | Sens = 0.49 (0.38 to 0.61) spec = 1.00 (0.82 to 1.00) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

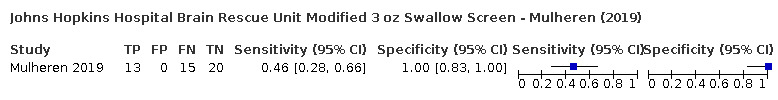

| Johns Hopkins Hospital Brain Rescue Unit Modified 3 oz Swallow Screen: Mulheren 2019 | 48 (1) | VFSS | Sens = 0.46 (0.28 to 0.66) spec = 1.00 (0.83 to 1.00) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

| Water plus consistencies tests | 412 (5) | |||

| Registered Dietitian (RD) Dysphagia Screening tool: Huhmann 2004 | 32 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 1.00 (0.69 to 1.00) spec = 0.86 (0.65 to 0.97) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

| Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS) ‐ Group2: Trapl 2007 | 30 (1) | FEES | Sens = 1.00 (0.77 to 1.00) spec = 0.69 (0.41 to 0.89) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

| Standardized Swallowing Assessment tool (SSA) – Test2: Perry 2001 Study 1 | 68 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.97 (0.86 to 1.00) spec = 0.90 (0.74 to 0.98) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

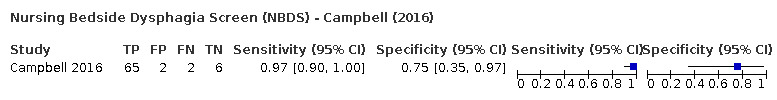

| Nursing Bedside Dysphagia Screen (NBDS): Campbell 2016 | 75 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.97 (0.90 to 1.00) spec = 0.75 (0.35 to 0.97) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

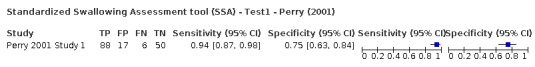

| Standardized Swallowing Assessment tool (SSA) ‐ Test1: Perry 2001 Study 1 | 161 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.94 (0.87 to 0.98) spec = 0.75 (0.63 to 0.84) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

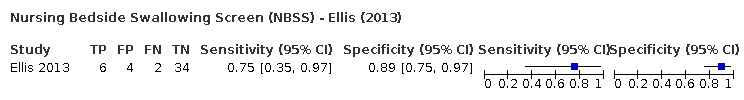

| Nursing Bedside Swallowing Screen (NBSS): Ellis 2013 | 46 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.75 (0.35 to 0.97) spec = 0.89 (0.75 to 0.97) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

| Other tests | 627 (5) | |||

| Bedside aspiration ‐ Combined WST & Oxygen Saturation: Lim 2001 | 50 (1) | FEES | Sens = 1.00 (0.87 to 1.00) spec = 0.71 (0.49 to 0.87) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

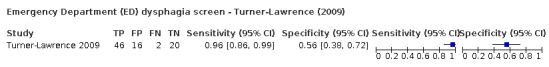

| Emergency Department (ED) dysphagia screen: Turner‐Lawrence 2009 | 84 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.96 (0.86 to 0.99) spec = 0.56 (0.38 to 0.72) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

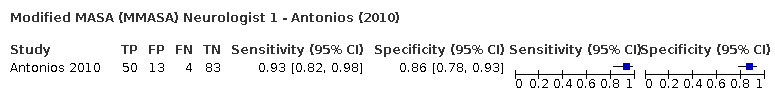

| Modified MASA (MMASA) Neurologist 1: Antonios 2010 | 150 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.93 (0.82 to 0.98) spec = 0.86 (0.78 to 0.93) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

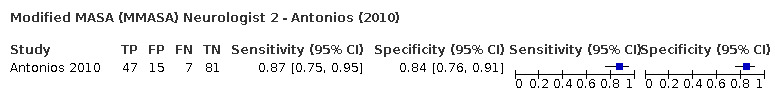

| Modified MASA (MMASA) Neurologist 2: Antonios 2010 | 150 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.87 (0.75 to 0.95) spec = 0.84 (0.76 to 0.91) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

| Oxygen saturation ≥ 2% ‐ Test2 for Aspiration: Smith 2000 | 53 (1) | VFSS | Sens = 0.87 (0.60 to 0.98) spec = 0.39 (0.24 to 0.57) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

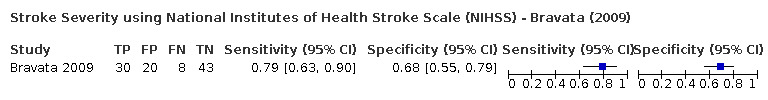

| Stroke Severity using National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS): Bravata 2009 | 101 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.79 (0.63 to 0.90) spec = 0.68 (0.55 to 0.79) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

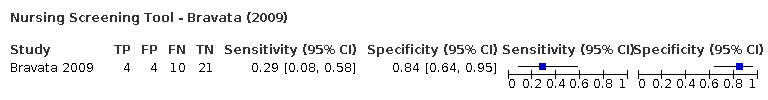

| Nursing Screening Tool: Bravata 2009 | 39 (1) | Expert assessment and MASA | Sens = 0.29 (0.08 to 0.58) spec = 0.84 (0.64 to 0.95) | Insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions |

FEES: fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing. MASA: Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability. sens: sensitivity. spec: specificity. VFSS: videofluoroscopic swallowing study. WST: water‐swallowing test.

Background

Stroke is the second most common cause of death worldwide (Katan 2018), and it is the largest cause of complex preventable disability in adults (WHF 2016). Over 13.7 million new strokes are reported globally each year (Johnson 2019), with a projected increase in incidence due to an ageing population (Avan 2019).

The reported incidence of dysphagia (swallowing difficulties) following acute stroke varies between 37% and 78% (Martino 2005); this is related to type and severity of stroke and individual characteristics (e.g. comorbidities). It is also related to the type of diagnostic assessment used to detect dysphagia and time from admission to that assessment. Dysphagia may lead to aspiration, defined as food or fluid entering the airway below the level of the vocal cords (Blitzer 1988), then into the trachea. People with dysphagia are three times, and those with aspiration 11 times, more likely to develop pneumonia (Kumar 2010; Rofes 2011), which is a significant cause of further morbidity leading to increased hospital stay and risk of death (Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party 2012).

Stroke‐associated pneumonia is more common if identification of dysphagia is delayed because of aspiration of food, drink, medications, and oral secretions (Bray 2016). Therefore, early screening for dysphagia may be an important avenue for reducing deaths from acute stroke (Bray 2016; Donovan 2013).

Internationally, different clinical guidelines are available for detecting swallowing difficulties in acute stroke. Identification of dysphagia is a criterion that is considered for obtaining Stroke Unit accreditation by the European Stroke Organisation. Within the UK, Europe, Canada, the USA, and Australia, guidelines state that on admission to hospital, people with acute stroke should have their swallowing screened promptly following admission (European Stroke Organisation 2015; Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party 2016; National Stroke Foundation 2010; Powers 2019; Teasell 2019).

Diagnostic methods such as videofluoroscopy (VF) and fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) are available. However, these methods have significant limitations when used for early identification of dysphagia in acute stages of stroke. Limitations may be patient specific (patients may be unable to comply with instructions due to poor posture, cognition, medical state, or fluctuating swallowing ability); organisational (speech and language therapists (SLTs) may not be available in the acute setting, and in most hospitals, instrumental examinations such as VF and FEES can be requested only after SLT evaluation; furthermore, not all staff are trained to interpret the results of these reference tests); or procedural (specialist equipment is not available in all acute settings) (Boaden 2011). Therefore, screening tools are needed to identify those likely to have dysphagia, who might be at greater risk of aspiration, so that interventions can be put in place to reduce morbidity until access to specialist equipment and staff is available for assessment and/or until the patient is fit enough to undergo the procedures. These screening tools are called bedside swallow screening tools.

Bedside swallow screening tools must be quick and easy to administer. To be clinically useful, screening tools must accurately identify those with dysphagia with its associated risk of aspiration (sensitivity), without leading to unnecessary restrictions (e.g. withholding food and drinks) for those who do not have dysphagia (specificity). The outcome of a screening test is binary (present or not), although it is acknowledged there may be different levels of severity of swallowing difficulty and subsequent management. A positive test should lead to a referral for more definitive assessment to confirm the presence of dysphagia or not, when this is available. Screening tools also need to be acceptable and feasible for use in people with a range of sequelae following stroke (e.g. different levels of consciousness, cognitive levels, postural difficulties). Screening tools must be undertaken prior to any oral intake and therefore need to be administered by staff members who are at the bedside throughout a 24‐hour period.

There is wide variation in available screening tools. Some swallow screening tools rely on questionnaires, whilst others use food and drink as testing materials. Swallow screening tools vary in the types of foods and fluids tested. Water swallow tools, such as the Standardised Swallow Assessment (Perry 2001 Study 1), or the Massey Bedside Swallow Screen (Massey 2002), are very similar in that they offer people different quantities of fluids from assorted utensils; some studies use water plus a range of consistencies to prescribe food and drink consistency management plans. This group of swallow screening tests are more dissimilar from each other as they offer a variety of food and drink, give different consistencies, trial different volumes, and alter the order in which foods and drinks are offered. One concern is that some of these tools have been developed and assessed with various reference tests and different professional groups not routinely available at the bedside, which limits their clinical utility.

There is no universally accepted screening tool for identification and management of aspiration associated with dysphagia, and a wide range of screening tests are used in clinical practice throughout the world. A false‐negative result is much worse than a false‐positive result. If the swallow screening test fails to identify swallowing difficulties, the person will continue oral intake and may experience the difficulties identified above. If the swallow screening test erroneously identifies swallowing difficulties, the patient is placed 'nil by mouth', with significant impact on quality of life, until the SLT undertakes a more detailed assessment (usually the next day). So a bedside swallow screening tool should be chosen while taking into account this simple clinical reality. Hence, there is a need to identify the most clinically useful screening test or tools that most accurately identify the presence or absence of aspiration associated with dysphagia, and to prescribe a food and drink consistency management plan for individuals with aspiration to improve their medical, social, and psychological outcomes.

Target condition being diagnosed

Aspiration risk associated with dysphagia in people who have had an acute stroke.

Index test(s)

In this review, bedside swallowing screening tests not administered by SLTs are the index tests. A wide range of index tests (swallow screening tests) are used at the bedside by healthcare professionals for recognition or determination of whether the patient is at risk of aspirating food and fluids.

Clinical pathway

Bedside swallow screening tests are commonly used in the typical care pathway in compliance with clinical guidelines for stroke. However, there are varying degrees of compliance. Usually these tests are implemented by allied healthcare professionals (mainly nurses) following admission to the acute care sector. Patients who are identified as at risk of swallowing difficulties are often placed 'nil by mouth' while awaiting an expert assessment or a further reference test. The care pathway for patients who have a negative test result usually allows patients to continue to eat and drink orally.

Prior test(s)

No tests to assess swallowing are conducted on patients before hospital admission.

Role of index test(s)

Index tests, that is, bedside screening tests not administered by SLTs, have the potential to improve the identification of people with risk of aspiration associated with dysphagia following stroke. Therefore, these tests may reduce the need for SLT evaluation and for more complex, invasive, and more expensive imaging methods, such as VF, FEES, or scintigraphy, which may not be available in some healthcare settings.

Alternative test(s)

Other index tests include questionnaires that rely on self‐reported dysphagia symptoms. However, these tools, for example, the Sydney Swallow Questionnaire (SSQ) and the Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire (SDQ), were used or designed and validated for use in patient populations such as those with head and neck cancer or Parkinson’s disease. These are not considered in this review.

Rationale

We reviewed the diagnostic accuracy of currently available swallow screening tests. A systematic review of published evaluations of these screening tests will assist practitioners to identify those that have undergone rigorous development and testing. This review will also identify gaps in evidence for further research.

Healthcare professionals within acute stroke care settings are responsible for deciding which bedside swallow screening test they will use to detect people at risk of aspiration associated with dysphagia in adult acute stroke patients. When a bedside swallow screening test is considered, a test with high sensitivity and specificity is paramount. False‐negative results may lead to serious consequences within the clinical context, as continued oral intake may precipitate aspiration pneumonia and death. High specificity is also beneficial, as false‐positive results may result in patients being designated ‘nil by mouth’ and provided with clinically assisted nutrition and hydration unnecessarily. This adversely affects the well‐being of the patient and incurs unnecessary costs. However, false‐positive results are less dangerous, in that usually an SLT will see the patient within 24 hours.

A recent systematic review of bedside swallow screening tests provided a descriptive analysis of the different elements within screening tests but did not compare these with a reference standard (Almeida 2015). Other reviews have not specifically focused on a stroke population (Brodsky 2016; O'Horo 2015), have included studies in which screening was not undertaken in a timely manner (Schepp 2012), have focused on individual clinical determinants or behaviours associated with aspiration (Daniels 2012), have reviewed only multi‐consistency tests (Benfield 2020), or have accepted delays longer than 24 hours between the index test and the reference standard (Daniels 2012). The results of this review will help guide policy makers and healthcare workers in acute hospital settings on selection of the most appropriate bedside swallow screening test from those currently available and might also identify the research agenda going forward.

Objectives

Primary objective

To determine the diagnostic accuracy and the sensitivity and specificity of bedside screening tests for detecting risk of aspiration associated with dysphagia in people with acute stroke

Secondary objectives

-

To assess the influence of the following sources of heterogeneity on the diagnostic accuracy of bedside screening tools for dysphagia

Patient demographics (e.g. age, gender)

Time post stroke that the study was conducted (from admission to 48 hours) to ensure only hyperacute and acute stroke swallow screening tools are identified

Definition of dysphagia used by the study

Level of training of nursing staff (both grade and training in the screening tool)

Low‐quality studies identified from the methodological quality checklist

Type and threshold of index test

Type of reference test

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered single‐gate and two‐gate studies if they compared the accuracy of a bedside screening tool administered by nursing staff or other healthcare professionals (excluding SLTs) with identified reference tests (VF, FEES, scintigraphy, expert assessment). We applied no restrictions in terms of language of publication.

Participants

We included studies if they involved adults (aged 18 and over) who had been admitted to an acute hospital setting with a clinical diagnosis of stroke. We considered studies that were inclusive of people with subarachnoid haemorrhage and we excluded this sample subgroup from the analysis, when possible. We excluded studies that included only patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. We also excluded studies that admitted patients with trauma.

Index tests

We included studies if they evaluated a bedside swallow screening test, used by nursing staff or other healthcare professionals (excluding SLTs who have expert knowledge in this area), for recognition or determination of whether patients were at risk of aspiration associated with dysphagia.

Target conditions

We included studies if they reported the accuracy of the bedside screening tool for identification of the risk of aspiration owing to dysphagia post stroke.

Reference standards

We included studies if a bedside swallow screening test, carried out by nursing staff or other healthcare professionals, was compared with VF, FEES, scintigraphy, or an expert assessment. Videofluoroscopy is an X‐ray video of swallowing, allowing the swallow to be analysed in real time. FEES involves insertion of a fibreoptic flexible endoscope that is passed through the nasal passages to view the throat pre‐swallows and post‐swallows for secretion management, residue, and aspirated material. Scintigraphy uses radioisotopes that are swallowed, and the emitted radiation is captured by external detectors (gamma cameras) to form images of swallowed material. Expert assessments included assessments conducted by dysphagia‐trained professionals such as SLTs. All reference standards are not equally valid and available (the SLT is not usually available in the acute setting and is not available 24 hours each day and seven days a week), and some procedures are more invasive than others. Expert assessment was included as a reference standard owing to the lack of immediate access to imaging or instrumental assessment in many centres, and to the inability of some patients to co‐operate with these assessments. However, expert assessments have limitations in their ability to identify at bedside those patients who have swallowing difficulties owing to silent aspiration when the patient demonstrates no clinical signs of aspiration.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The search strategy used was developed with the help of the Cochrane Stroke Group Information Specialist. We searched relevant electronic databases for eligible diagnostic studies from inception until 9 December 2019: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 12), in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE Ovid (from 1946); Embase Ovid (from 1980); the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) EBSCO (from 1937 onward), and the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database via the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (University of York). The search strategy for MEDLINE is presented in Appendix 1 and was adapted for CENTRAL (Appendix 2), Embase (Appendix 3), CINAHL (Appendix 4), and HTA (Appendix 5).

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all included studies, and we performed a cited reference search using Science Citation Index, to identify additional relevant studies and systematic reviews. We also contacted experts in the field to identify ongoing studies and those potentially missed by the search strategy.

We searched targeted grey literature sources, which we identified from the the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) Grey Matters document (CADTH 2018). A full list of the grey literature sources searched is displayed in Appendix 6.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors from the team (EB, JB, HR, DD) independently screened all titles and abstracts identified by the electronic database searches and excluded duplications and irrelevant records. Conflicts were resolved by involvement of a third review author (PD, AA). We then obtained full‐text articles for the remaining studies, which were independently assessed for inclusion by two review authors (EB, ML, HR, PD) using the eligibility criteria described above. Disagreements were resolved by consensus meetings, with arbitration provided by a third review author (AA) who had not initially reviewed the paper. When multiple papers used the same cohort of patients, we used the paper with the most complete and up‐to‐date data. When we identified relevant conference abstracts, we looked for the corresponding full‐text article. If we found no full‐text article, we contacted the authors of the conference abstract. We excluded conference abstracts with insufficient data to calculate the 2 × 2 table. The selection process is detailed in the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1.

1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (JB, EM) designed a bespoke data extraction form to collect details from the included studies. We piloted the form on other diagnostic accuracy studies related to acute stroke management that are beyond the scope of this review. For each study, we extracted information related to characteristics of the study, the patient population, index tests, reference standards, and any relevant outcomes.

Among a group of review authors (JB, AC, LH, CEL, ML, CW), two independently extracted the data to ensure adequate reliability and quality. These two review authors then met to agree on final data extractions for each included study. When there was disagreement between the two review authors, a third review author from the group acted as an arbitrator. Once data extraction was complete, we entered the information into RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014).

Assessment of methodological quality

Two review authors from the group (JB, AC, LH, CEL, ML, CW) independently reviewed the methodological quality of each included study, using criteria from the Quality Assessment of Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy (QUADAS‐2) tool, as recommended by Cochrane (Appendix 7). As with previous diagnostic test accuracy reviews (Gupta 2016), we changed the QUADAS‐2 question "Was a case‐control design avoided?" to "Was a two‐gate design avoided?".

We piloted the QUADAS‐2 to promote agreement in interpretation within the team. We resolved disagreements with a third review author. We rated the QUADAS‐2 criteria as ’yes’, ’no’, or ’unclear’ for each included study. As stated in our protocol, guidance indicates that criteria 1, 2, 3, and 9 should receive particular attention regarding definitions used as the basis for decisions. The other criteria are more self‐explanatory with regards to their interpretation.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

From each index test, the parameters of interest were sensitivity and specificity. For a majority of index tests, these were calculated from the 2 × 2 tables. For other index tests, information from reported parameters (sensitivity, specificity, or predictive values) was used to inform the 2 × 2 table, yielding true‐positive, false‐positive, true‐negative, and false‐negative values. From available information, sensitivities, specificities, and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated by RevMan 5 and plotted in forest plots and summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) plots. In the absence of sufficient data, to calculate the 2 × 2 tables, we contacted study authors for further information. If this information remained unavailable, we included the study in the review as a narrative study.

Data from a single study were used only once in each analysis. We checked all studies to see if all patients were included, or if the number of patients was fixed, a priori in the design, from a condition (from the reference test) or from the index test. If the numbers of patients were fixed, the formulae for sensitivity and specificity would be different. No included studies used such numbers fixed a priori.

Pooling of sensitivity and specificity results was intended for each index test. However, due to the small number of studies using the same index test (three or fewer), we did not perform any meta‐analyses of diagnostic accuracy data. Pooling of screening tests by general categories was performed as part of the descriptive analysis, presented along with sensitivity and specificity.

Investigations of heterogeneity

Possible co‐variates of interest were patient demographics (e.g. age, gender), time post stroke that the study was conducted, and level of training of nursing staff. However, the potential influence of these co‐variates could not be investigated due to the small number of studies for each index test. The definitions of dysphagia used by the study could have been grouped, and the type and quality of the reference test, as well as the type of index test, investigated as sources of heterogeneity. For the same reason, no subgroup analyses were performed involving age, gender, time post stroke of the index test, or index test type, and whether there had been a significant change in the participant’s condition between performance of index and reference tests. Index tests were pooled by broad categories (by index test type, by healthcare professional (HCP), by outcome, and by reference test), and graphical comparisons were made. We therefore performed only a narrative review running exploratory analysis in RevMan 5 to show graphically if the co‐variates of interest are likely to be related to test accuracy, displayed using forest plots and SROC plots.

Sensitivity analyses

We did not carry out any sensitivity analyses due to the small number of studies for each index test. We had proposed to exclude low‐quality studies and possibly reporting a delay in time between index and reference tests due to potential changes in patient consciousness and cognitive state.

Assessment of reporting bias

Since no methods are available to quantify publication bias in diagnostic test accuracy reviews, we did not conduct an assessment of reporting bias.

Results

Results of the search

We conducted two searches ‐ the first in June 2017 and the same search in December 2019. We identified 26,701 papers through database searches, and we found two additional studies by handsearching the references of existing systematic reviews, for a total of 20,567 articles once duplicates were removed. After titles and abstracts of articles had been screened, we assessed the full texts of 233 articles against the eligibility criteria. Of these, we excluded 208 articles ‐ 35 because they did not compare appropriate index and reference tests, 24 because they did not involve consecutive acute stroke patients, 16 because they did not relate to screening for dysphagia, eight because index tests were carried out by experts, three because they involved only patients with dysphagia or aspiration and so sensitivity and specificity could not be calculated, two because they were not single‐gate or two‐gate studies, and one because not all patients received the same reference test (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Additionally, we excluded 57 references that were conference abstracts, 38 that were not primary research studies, 12 that were duplicate papers, six that had been withdrawn or were unavailable, three that were research protocols or trial registrations, two that were Master's or PhD theses, and one that was not relevant. Twenty‐five articles went through to data extraction and were included in the final review. Four of the included articles did not include enough detail for calculating the diagnostic accuracy of the index test, thus we included these in narrative descriptions only. More detail is shown in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1).

We checked the reference lists of included studies, but this did not reveal additional eligible papers. Details on participants, index tests, reference tests, and sensitivity and specificity of each index test are displayed in the Characteristics of included studies table.

The 25 included studies investigated a total of 37 screening tools, most of which were different tools. All 25 studies are single‐gate studies. Of 37 screening tools, 21 were used by nurses and 16 by other HCPs. The other HCPs were doctor or physician (n = 6), dietician (n = 1), neurologist (n = 2), multiple HCPs (n = 4), and HCP not recorded (n = 3). Of the 37 screening tools, four could not be included in an available quantitative analysis as 2 × 2 tables could not be constructed to estimate sensitivity or specificity (Eren 2019;Martino 2014;Nishiwaki 2005;Zhou 2011). Training was given for screening tools used by 17 (81%) nurses and by four (25%) other HCPs.

Demographic information and characteristics of all 37 screening tests (including the four narrative tests) are given in Table 3. When reported, mean age was 58.6 years to 76.8 years, the percentage of males in the study was 35% to 100%, and the start date of study recruitment was between 1995 and 2016. Twenty‐two (59%) tests were conducted in the USA and Canada, eight (22%) in the UK and Europe, and six (16%) in other countries; in one (3%) study, the country was not recorded. Only two (5%) studies used an established classification system to record the location of the stroke. The median sample size was 100, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 50 to 161; 16 (48%) screening tools had a sample size less than 100.

1. Description of screening tests.

| Tests (percentage) (n = 37 tests) |

||

| Complete or narrative | Complete ‐ 2 × 2 table data extracted | 33 (89%) |

| Narrative ‐ 2 × 2 table data not available | 4 (11%) | |

| Participants | ||

| Na | Median (IQR) 100 (50 to 161) | Min = 22, max = 300 |

| N with dysphagia/aspirationa | Median (IQR) 38 (17 to 63) | Min = 8, max = 106 |

| Mean age | Median (IQR) 67.6 (64.75 to 71.4) | Min = 58.6, max = 76.8 |

| Sex % male | Median (IQR) 54.7 (49 to 65.6) | Min = 35, max = 100 |

| Year recruitment started | Min = 1995, max = 2016 | |

| Country | UK and Europe | 8 (22%) |

| USA and Canada | 22 (59%) | |

| Other | 6 (16%) | |

| Not recorded | 1 (3%) | |

| Study design | ||

| Admission to index test | ≤ 24 hours | 16 (43%) |

| > 24 hours and < 72 hours | 6 (16%) | |

| ≥ 72 hours | 2 (5%) | |

| Not recorded | 13 (35%) | |

| Order tests applied | Index then reference | 28 (76%) |

| Reference then index | 1 (3%) | |

| Mixed or not specified | 5 (14%) | |

| Not recorded | 3 (8%) | |

| Index/reference time interval | ≤ 24 hours | 18 (49%) |

| > 24 hours | 10 (27%) | |

| Not recorded | 9 (24%) | |

| Index test training given | Yes | 21 (57%) |

| Not recorded | 16 (43%) | |

| Index test type | Water only | 24 (65%) |

| Water plus other consistencies | 6 (16%) | |

| Other | 7 (19%) | |

| Index test HCP | Nurse | 21 (57%) |

| Other | 16 (43%) | |

| Outcome | Aspiration | 15 (41%) |

| Dysphagia | 20 (54%) | |

| NR | 2 (5%) | |

| Reference test | Expert assessment and MASA | 20 (54%) |

| FEES | 6 (16%) | |

| VF | 11 (30%) | |

aUsing complete studies only. FEES: fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing. HCP: healthcare professional. IQR: interquartile range. MASA: Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability. VF: videofluoroscopy.

For 16 (43%) tests, admission to index test time was ≤ 24 hours, for six (16%) between 24 hours and 72 hours, and for two (5%) ≥ 72 hours; for 13 (35%), this information was not recorded. For 28 (76%) tests the index test was applied before the reference test, for one (3%) the reference test was applied before the index test, for five (14%) the order was not specified or mixed, and for three (8%) this was not recorded. The time interval between index and reference tests was ≤ 24 hours for 18 (49%) tests, was > 24 hours for 10 (27%) tests, and was not recorded for nine (24%) tests.

Twenty‐four (64.9%) screening tools used water only (Behera 2018a; Behera 2018b; Cummings 2015; Daniels 1997; Daniels 2016a; Daniels 2016b; Edmiaston 2010a; Edmiaston 2010b; Edmiaston 2014a; Edmiaston 2014b; Eren 2019; Huhn‐Matesic 2015; Jiang 2019a; Jiang 2019b; Lim 2001b; Martino 2009 Study 1; Martino 2014; Mulheren 2019; Nishiwaki 2005; Perry 2001 Study 1a; Perry 2001 Study 1b; Warnecke 2008a; Warnecke 2008b; Zhou 2011), six (16.2%) used water and other consistencies (Campbell 2016; Ellis 2013; Huhmann 2004; Perry 2001 Study 1c; Perry 2001 Study 1d; Trapl 2007b), and seven (18.9%) used other methods. The other methods were evaluation of patient characteristics only (Antonios 2010a; Antonios 2010b; Bravata 2009a), notes review (Bravata 2009b), combined water swallow test and oxygen saturation (Lim 2001a), oxygen saturation (Smith 2000), and evaluation of patient characteristics followed by water swallow test and oxygen saturation (Turner‐Lawrence 2009). Several references reported use of more than one screening tool as detailed in Table 4.

2. Index test reference IDs.

| Test ID | Test name |

| Antonios 2010a | Modified MASA (MMASA) Neurologist 1: Antonios 2010 |

| Antonios 2010b | Modified MASA (MMASA) Neurologist 2: Antonios 2010 |

| Behera 2018a | DePaul Hospital Swallow Screener (DHSS) Aspiration: Behera 2018 |

| Behera 2018b | DePaul Hospital Swallow Screener (DHSS) Dysphagia: Behera 2018 |

| Bravata 2009a | Nursing Screening Tool: Bravata 2009 |

| Bravata 2009b | Stroke Severity using National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS): Bravata 2009 |

| Campbell 2016 | Nursing Bedside Dysphagia Screen (NBDS): Campbell 2016 |

| Cummings 2015 | Nurse Dysphagia Screen: Cummings 2015 |

| Daniels 1997 | Clinical examination: Daniels 1997 |

| Daniels 2016a | Rapid Aspiration Screening for Suspected Stroke (RAS3): Daniels 2016 |

| Daniels 2016b | Rapid Aspiration Screening for Suspected Stroke (RAS3) ‐ WST only: Daniels 2016 |

| Edmiaston 2010a | Acute Stroke Dysphagia Screening (ASDS) Aspiration: Edmiaston 2010 |

| Edmiaston 2010b | Acute Stroke Dysphagia Screening (ASDS) Dysphagia: Edmiaston 2010 |

| Edmiaston 2014a | Barnes‐Jewish Hospital‐Stroke Dysphagia Screen (BJH‐SDS) Aspiration: Edmiaston 2014 |

| Edmiaston 2014b | Barnes‐Jewish Hospital‐Stroke Dysphagia Screen (BJH‐SDS) Dysphagia: Edmiaston 2014 |

| Ellis 2013 | Nursing Bedside Swallowing Screen (NBSS): Ellis 2013 |

| Eren 2019 | Barnes‐Jewish Hospital Stroke Dysphagia Screen – Turkish version (BJH‐SDS) or (T‐BJH): Eren 2019 |

| Huhmann 2004 | Registered Dietitian (RD) Dysphagia Screening tool: Huhmann 2004 |

| Huhn‐Matesic 2015 | Edith‐Huhn‐Matesic Bedside Aspiration Screen (EHMBAS) followed by simple water swallow test: Huhn‐Matesic 2015 |

| Jiang 2019a | Chinese version of the modified SSA – original 8 items: Jiang 2019 |

| Jiang 2019b | Chinese version of the modified SSA – reduced 6 items: Jiang 2019 |

| Lim 2001a | Bedside aspiration ‐ Combined WST and Oxygen Saturation: Lim 2001 |

| Lim 2001b | Bedside swallow test ‐ WST only: Lim 2001 |

| Martino 2009 | Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test (TOR‐BSST): Martino 2009 Study 1 |

| Martino 2014 | TOR‐BSST water swallow item: Martino 2014 |

| Mulheren 2019 | Johns Hopkins Hospital Brain Rescue Unit Modified 3 oz Swallow Screen: Mulheren 2019 |

| Nishiwaki 2005 | Clinical swallowing tests: Nishiwaki 2005 |

| Perry 2001a | Gag function ‐ Test3: Perry 2001 Study 1 |

| Perry 2001b | Gag function ‐ Test4: Perry 2001 Study 1 |

| Perry 2001c | Standardized Swallowing Assessment tool (SSA) ‐ Test1: Perry 2001 Study 1 |

| Perry 2001d | Standardized Swallowing Assessment tool (SSA) – Test2: Perry 2001 Study 1 |

| Smith 2000 | Oxygen saturation ≥ 2% ‐ Test2 for Aspiration: Smith 2000 |

| Trapl 2007b | Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS) ‐ Group2: Trapl 2007 |

| Turner‐Lawrence 2009 | Emergency Department (ED) dysphagia screen: Turner‐Lawrence 2009 |

| Warnecke 2008a | 2‐step swallowing provocation test (SPT) ‐ step 1 ‐ 0.4 mL: Warnecke 2008 |

| Warnecke 2008b | 2‐step swallowing provocation test (SPT) ‐ step 2 ‐ 2.0 mL: Warnecke 2008 |

| Zhou 2011 | Clinical predicative scale of aspiration (CPSA): Zhou 2011 |

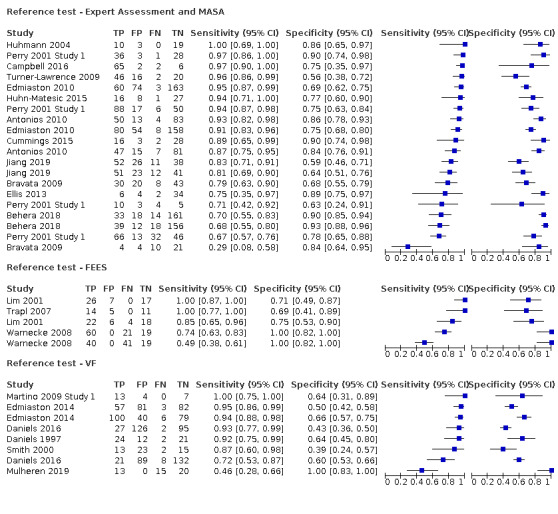

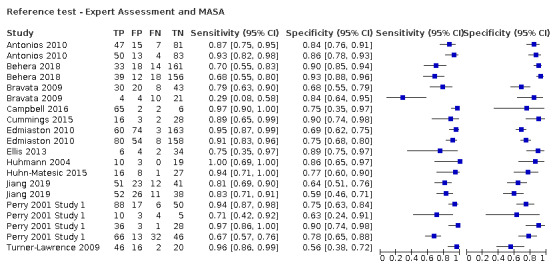

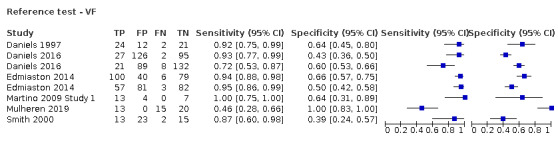

Expert assessment or the Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability (MASA) was utilised for 20 (54.1%) screening tools as the reference test (Antonios 2010a; Antonios 2010b; Behera 2018a; Behera 2018b; Bravata 2009a; Bravata 2009b; Campbell 2016; Cummings 2015; Edmiaston 2010a; Edmiaston 2010b; Ellis 2013; Huhmann 2004; Huhn‐Matesic 2015; Jiang 2019a; Jiang 2019b; Perry 2001 Study 1a; Perry 2001 Study 1b; Perry 2001 Study 1c; Perry 2001 Study 1d; Turner‐Lawrence 2009); six (16.2%) used FEES (Eren 2019; Lim 2001a; Lim 2001b; Trapl 2007b; Warnecke 2008a; Warnecke 2008b), and 11 (29.7%) used VF (Daniels 1997; Daniels 2016a; Daniels 2016b; Edmiaston 2014a; Edmiaston 2014b; Martino 2009 Study 1; Martino 2014; Mulheren 2019; Nishiwaki 2005; Smith 2000; Zhou 2011).

We identified 15 (40.5%) screening tools that had an outcome of aspiration risk (Behera 2018a; Daniels 1997; Daniels 2016a; Daniels 2016b; Edmiaston 2010a; Edmiaston 2014a; Huhn‐Matesic 2015; Lim 2001a; Lim 2001b; Nishiwaki 2005; Smith 2000; Trapl 2007b; Turner‐Lawrence 2009; Warnecke 2008a; Warnecke 2008b), and we found 20 (54.1%) that had an outcome of dysphagia (Antonios 2010a; Antonios 2010b; Behera 2018b; Bravata 2009a; Bravata 2009b; Campbell 2016; Cummings 2015; Edmiaston 2010b; Edmiaston 2014b; Ellis 2013; Eren 2019; Huhmann 2004; Jiang 2019a; Jiang 2019b; Martino 2009 Study 1; Mulheren 2019; Perry 2001 Study 1a; Perry 2001 Study 1b; Perry 2001 Study 1c; Perry 2001 Study 1d). Only two (5.4%) narrative papers did not record the outcome (Martino 2014; Zhou 2011).

Methodological quality of included studies

Risk of bias

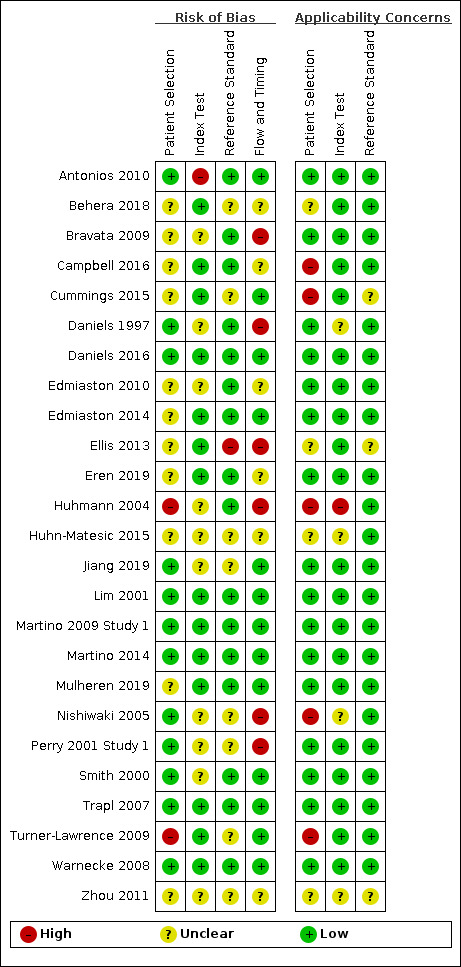

Results of the methodological quality assessment for each of the 25 included studies are shown in Figure 2. We considered six studies to be at low risk across all four risk of bias domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing (Daniels 2016; Lim 2001; Martino 2009 Study 1; Martino 2014; Trapl 2007; Warnecke 2008). Two studies were at low risk of bias for three domains (index test, reference standard, and flow and timing) but at uncertain risk for patient selection (Edmiaston 2014;Mulheren 2019).

2.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns summary: review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study.

A major concern for risk of bias across the other included studies was that they had not enrolled consecutive patients. We identified 12 studies that had enrolled consecutive patients (Antonios 2010; Daniels 1997; Daniels 2016; Jiang 2019; Lim 2001; Martino 2009 Study 1; Martino 2014; Nishiwaki 2005; Perry 2001 Study 1; Smith 2000; Trapl 2007; Warnecke 2008), but for 12 studies this was unclear (Behera 2018; Bravata 2009; Campbell 2016; Cummings 2015; Edmiaston 2010; Edmiaston 2014; Ellis 2013; Eren 2019; Huhmann 2004; Huhn‐Matesic 2015; Mulheren 2019; Zhou 2011), and one study employed a convenience sampling method (Turner‐Lawrence 2009). For 11 studies, it is unclear whether inappropriate exclusions had been avoided when participants were recruited (Behera 2018; Bravata 2009; Cummings 2015; Edmiaston 2010; Ellis 2013; Huhmann 2004; Huhn‐Matesic 2015; Martino 2014; Perry 2001 Study 1; Turner‐Lawrence 2009; Zhou 2011). Finally, it is unclear in eight studies whether there had been an appropriate time interval between the index test and the reference standard (Behera 2018; Bravata 2009; Edmiaston 2010; Ellis 2013; Huhmann 2004; Huhn‐Matesic 2015; Perry 2001 Study 1; Zhou 2011), and it was reported that the time interval was not appropriate in two studies (Daniels 1997; Nishiwaki 2005).

Applicability concerns

There were no applicability concerns for 15 studies across the three applicability domains: patient selection, index test, and reference standard (Antonios 2010; Bravata 2009; Daniels 2016; Edmiaston 2010; Edmiaston 2014; Eren 2019; Jiang 2019; Lim 2001; Martino 2009 Study 1; Martino 2014; Mulheren 2019; Perry 2001 Study 1; Smith 2000; Trapl 2007; Warnecke 2008). However, concern was high in five studies (Campbell 2016; Cummings 2015; Huhmann 2004; Nishiwaki 2005; Turner‐Lawrence 2009), and concern was unclear in four other studies (Behera 2018; Ellis 2013; Huhn‐Matesic 2015; Zhou 2011), which included patients that did not match the review question. Concern that the index test, its conduct, or its interpretation differs from the review question was high in Huhmann 2004 and unclear in four studies (Daniels 1997; Huhn‐Matesic 2015; Nishiwaki 2005; Zhou 2011).

Findings

Healthcare professionals’ level of training across studies

The level of training for healthcare professionals undertaking the index test in dysphagia and/or use of the index test was underreported, with only 21 of 37 screening tests stating that training was offered. Of those that detailed the training, there was variation in both length and content. Some index tests required 10 minutes of training (n = 4), some took several hours (n = 3), and two detailed two days of training. The content of training varied between training to use the test plus element of competence (n = 5), instructions on how to use the index test (n = 4), instructions with a practice component (n = 2), training in anatomy and physiology of swallowing, identification and management of dysfunction and five successful practice assessments (n = 2), on‐line training in swallowing anatomy and physiology (n = 1), clinical signs of dysphagia and aspiration (n = 1), and digitised examples of five stroke patients with a review of basic anatomy and physiology of swallowing (n = 1). Some index tests reported that training was offered but did not detail the contents (n = 5).

Synthesis of results

The high level of heterogeneity between studies as identified by the review means that statistical pooling of diagnostic accuracy data was not possible. We performed a descriptive analysis from extracted data (2 × 2 tables) and sensitivity and specificity for all but the four screening tests for which this data could not be extracted (Eren 2019;Martino 2014;Nishiwaki 2005;Zhou 2011); these four studies are not included from this point onwards.

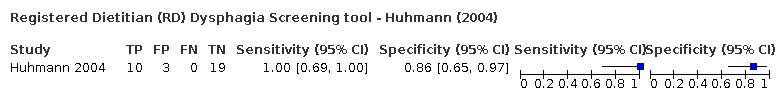

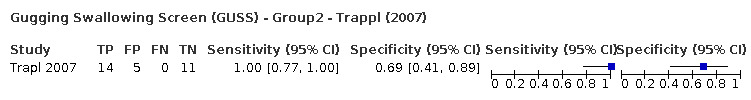

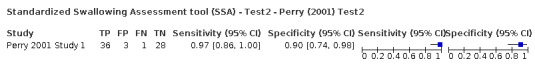

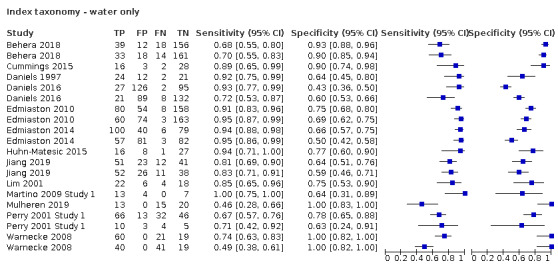

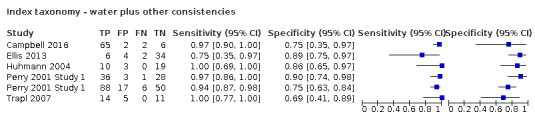

Values for sensitivity and specificity presented here include the point estimate (95% confidence interval (CI)). The criteria of both high sensitivity and high specificity indicate that the best performing test overall was the Standardized Swallowing Assessment tool (SSA) (Perry 2001 Study 1d) (n = 68), which had sensitivity of 0.97 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.00) and specificity of 0.90 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.98). However, Perry 2001 Study 1 performed poorly on the risk of bias assessment, showing, specifically, high risk of bias in the flow and timing domain and unclear risk of bias in both index test and reference standard domains, so this result should be interpreted with caution. Several tests performed better on sensitivity but less well on specificity: the Registered Dietician (RD) Dysphagia Screening tool (n = 32) had sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.86 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.97) (Huhmann 2004); the Bedside Aspiration test (n = 50) had sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.71 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.87) (Lim 2001a); the Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS) (n = 30) had sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.69 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.89) (Trapl 2007b); and the Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test (TOR‐BSST) (n = 24) had sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.64 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.89) (Martino 2009 Study 1).

Of the best performing screening tests, we have the most confidence in the following studies: Bedside Aspiration test (Lim 2001a), GUSS (Trapl 2007b), and TOR‐BSST (Martino 2009 Study 1), which we rated as having low risk of bias across all four QUADAS‐2 risk of bias domains. Of those with low risk of bias, the best performing screening test using only water was TOR‐BSST (Martino 2009 Study 1), and the best performing screening test using water plus other consistencies was GUSS (Trapl 2007b). A description of these tests is provided in Appendix 8. However, all of these screening tools had small sample sizes (n < 100), which limits interpretation of the estimates of reliability of these tests.

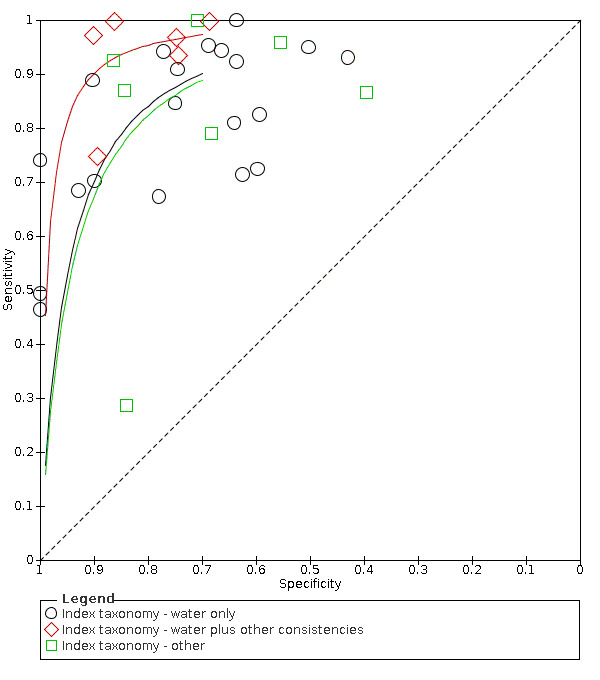

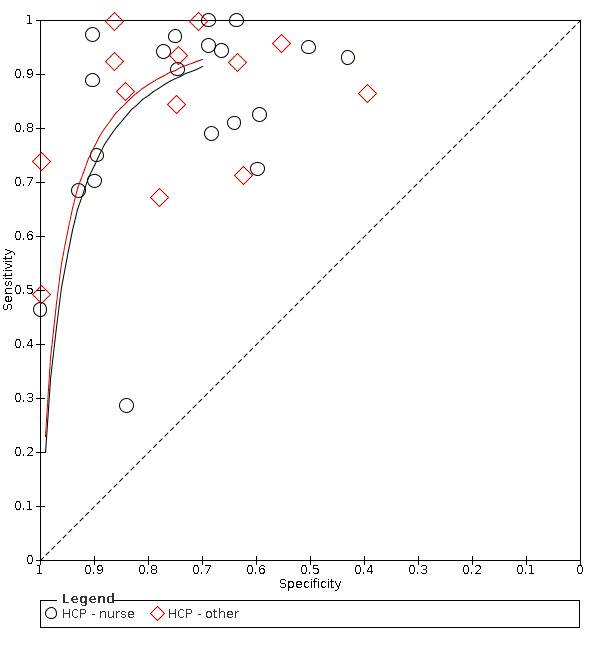

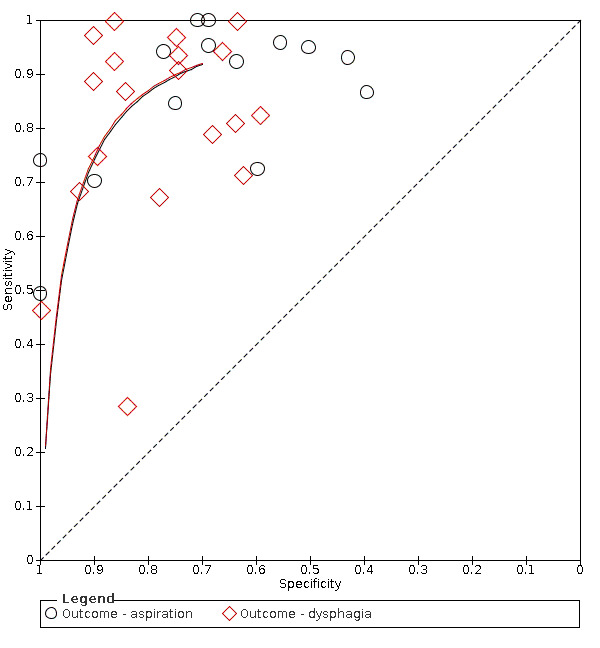

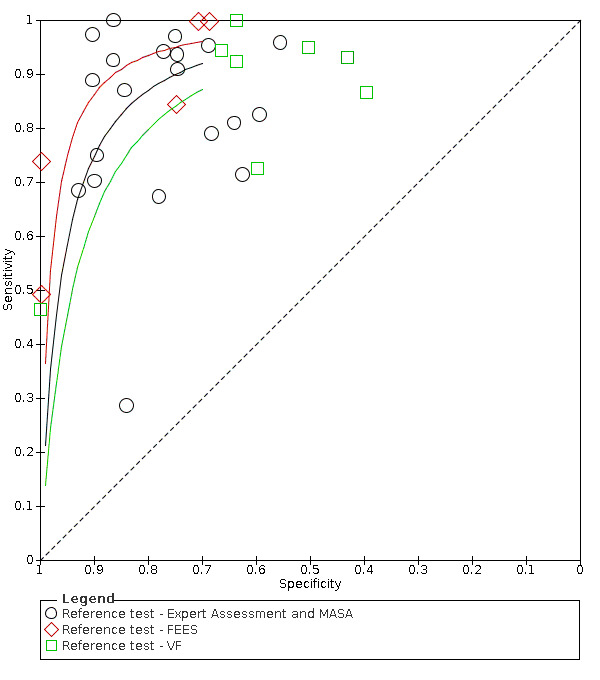

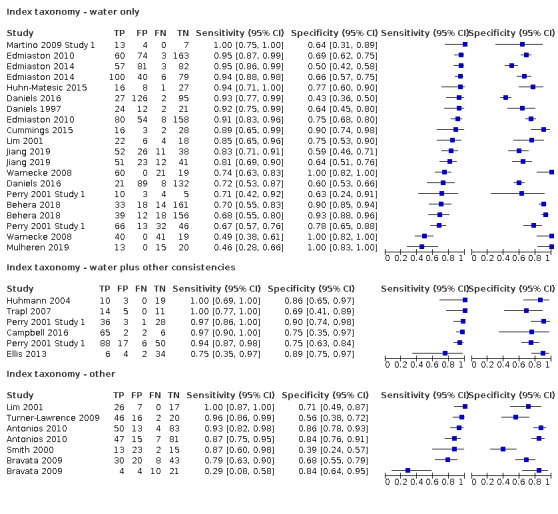

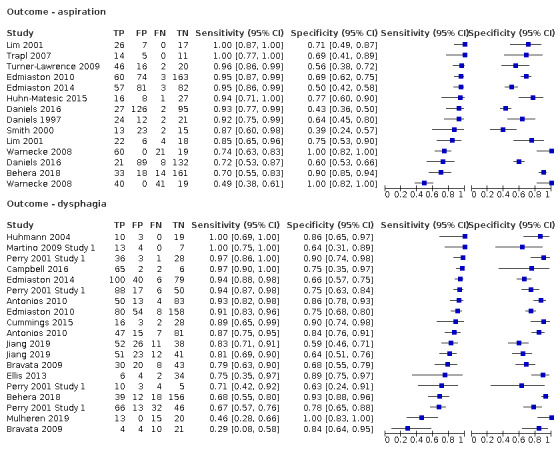

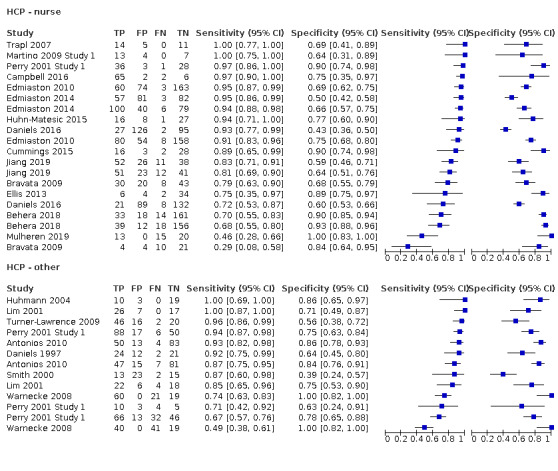

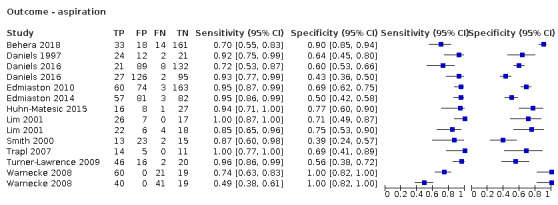

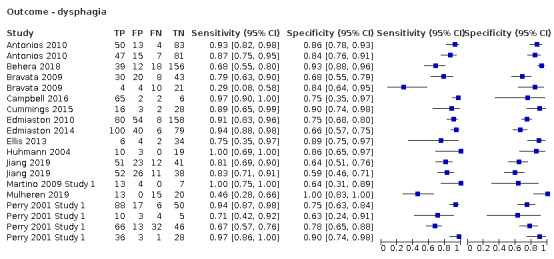

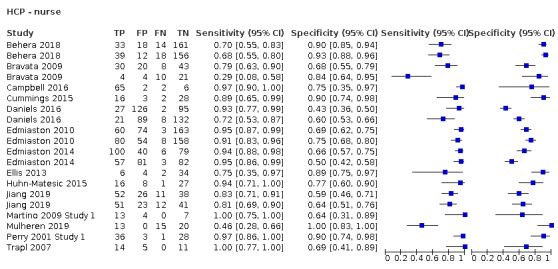

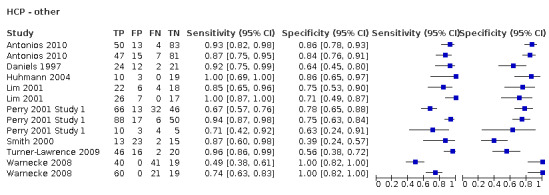

Screening tests were grouped into general categories according to taxonomy (water only tests, water plus other consistencies tests, and other tests), healthcare professionals who administered the test (nurses versus other healthcare professionals), types of outcomes (aspiration versus dysphagia), and types of reference standards (expert assessment or MASA versus VF versus FEES), and we generated related summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plots using RevMan 5 (see Figure 3; Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6). This informed the descriptive analysis, but no meta‐analysis was done because of the small number of studies identified for each individual screening test.

3.

Summary ROC plot of tests: Grouped by Index taxonomy ‐ water only, water plus bolus and other.

4.

Summary ROC plot of tests grouped by index test healthcare professional ‐ nurse and other.

5.

Summary ROC plot of tests: grouping index tests by outcome ‐ aspiration and dysphagia.

6.

Summary ROC plot of tests: index tests grouped by reference test used ‐ Expert Assessment, FEES and VS.

Type of test (water only tests versus water plus other consistencies tests versus other tests)

Screening tools that used water and other consistencies (accuracy ranged from sensitivity of 0.75 (95% CI 0.35 to 0.97) with specificity of 0.89 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.97), to sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.86 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.97)) generally were more accurate than screening tests that used only water (accuracy ranged from sensitivity of 0.46 (95% CI 0.28 to 0.66) with specificity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.00) to sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.64 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.89)). Those that used methods other than water only and water and other consistencies had mixed results; some performed as well as the water‐only tests, with the most accurate scoring sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.71 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.87)) (Figure 7). Others performed worse, with the least accurate scoring having sensitivity of 0.29 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.58) with specificity of 0.84 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.95)). Pooling of data by the screening test taxonomy confirmed that screening tests that used water plus other consistencies (participants n = 412) may be more sensitive with similar or better specificity than screening tests that used water only (participants n = 2914) or other methods (participants n = 627) (Figure 3). However, only six tests used this method. Screening tests that used only water had similar accuracy (in terms of sensitivity and specificity) compared with screening tests using other methods.

7.

Forest plot of tests grouped by Index Test Taxonomy ‐ Water only, Water plus other consistencies, and Other tests.

Type of reference standard (expert assessment or MASA versus VF versus FEES)

Screening tools showed better agreement with expert assessment or the MASA (accuracy ranged from sensitivity of 0.29 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.58) with specificity of 0.84 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.95) to sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.86 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.97)) than they did with the instrument‐based reference test of FEES (accuracy ranged from sensitivity of 0.49 (95% CI 0.38 to 0.61) with specificity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.00) to sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.71 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.87)) or VF (accuracy ranged from sensitivity of 0.46 (95% CI 0.28 to 0.66) with specificity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.00) to sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.64 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.89) (Figure 8). Pooling of screening tests by reference test (Figure 6) confirmed that screening tests that used expert assessment or the MASA (participants n = 2491) had the highest accuracy. This may be expected, as the screening tests will be more closely aligned to expert assessment methods than to instrumental assessment. Screening tests that used VF as a reference test had high sensitivity but lower specificity than those using expert assessment or the MASA. However, the number of index tests compared to instrument‐based reference tests was low: five were compared to FEES (participants n = 330) and eight were compared to VF (participants n = 1132).

8.

Forest plot of tests grouped by Reference Test ‐ Expert Assessment and MASA, FEES, and VF.

Type of primary outcome (aspiration versus dysphagia)

Screening tests with dysphagia as the primary outcome (accuracy ranged from sensitivity of 0.29 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.58) with specificity of 0.84 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.95) to sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.86 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.97)) generally performed better than screening tests for which the primary outcome was aspiration (accuracy ranged from sensitivity of 0.49 (95% CI 0.38 to 0.61) with specificity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.00) to sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.71 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.87)) (Figure 9). Pooling of screening tests by outcome (Figure 5) showed that screening tests with the greatest accuracy, with both high sensitivity and high specificity, had an outcome of dysphagia (participants n = 2126). This was to be expected, as dysphagia is more easily observed than aspiration. Several tests that detected aspiration risk (participants n = 1827) had high sensitivity but slightly lower specificity.

9.

Forest plot of tests grouped by Index Test Outcome ‐ aspiration and dysphagia.

Tests designed for nurses compared to tests designed for other healthcare professionals

Screening tools carried out by nurses (accuracy ranged from sensitivity of 0.29 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.58) with specificity of 0.84 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.95) to sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.69 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.89)) performed consistently better than those carried out by other HCPs (excluding SLTs) (accuracy ranged from sensitivity of 0.49 (95% CI 0.38 to 0.61) with specificity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.00) to sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.00) with specificity of 0.86 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.97)) (Figure 10). Generally, screening tests designed for use by nurses (participants n = 2785) performed equally well as those designed for use by other HCPs (excluding SLTs) (participants n = 1168) in terms of sensitivity and specificity (Figure 4).

10.

Forest plot of tests grouped by HCP ‐ nurse and other.

Other considerations

Screening tests with larger sample sizes (n > 200) were Behera 2018a, Behera 2018b, Daniels 2016a, Daniels 2016b, Edmiaston 2010a, Edmiaston 2010b, Edmiaston 2014a, and Edmiaston 2014b. Of these, screening tests with the greatest accuracy (both high sensitivity and high specificity) were Edmiaston 2010a, Edmiaston 2010b, and Edmiaston 2014b. All of these had narrow 95% CIs for estimates of sensitivity and specificity. Their lower 95% CIs for sensitivity had a higher value than for some of the overall best performing tests ‐ Lim 2001a, Trapl 2007b, and Martino 2009 Study 1. None of the tests with a larger sample size were assessed as low risk for all four QUADAS‐2 risk of bias (ROB) domains. Edmiaston 2010a and Edmiaston 2010b were unclear for three domains in the ROB and were low for one domain. Edmiaston 2014b was unclear for one domain in the ROB and was low for the other three domains. In summary, even though 95% CIs for estimates of sensitivity and specificity are narrower for the best performing screening tests, which used a larger sample size, their QUADAS‐2 risk of bias is not as low as that for the overall best performing tests.

Discussion

Numerous variables need to be systematically reported regarding training required by the healthcare professional undertaking the swallow screening tool, consistencies offered as part of the tool, and food and drink consistency management options available to the person undertaking the test post screen. From a clinical perspective, some bedside swallow screening tests are criticised for making recommendations for consistencies that have not been assessed. For example, water‐only tests allow normal dietary intake without assessment. Similarly water and other consistency screening tests show a discrepancy between diet and fluid consistencies tested and those recommended. Future studies should take these concerns into consideration.

Summary of main results

This review aimed to summarise the evidence regarding accuracy of swallow screening tests to detect aspiration risk associated with dysphagia in acute stroke. Studies did not always report sufficient information regarding study characteristics; therefore, it is not possible to explore the influence of sources of heterogeneity. Results show that a number of screening tools offered high sensitivity. However, we were unable to identify a swallow screening tool with concomitant high specificity. Furthermore, we were unable to identify a diagnostically accurate swallow screening tool that tests a variety of consistencies and offers immediate management advice for healthcare settings that do not have the facility to offer expert comprehensive assessments.

Population and setting

Although this review focused on acute stroke patients, some studies did not define the time period (from stroke onset or from admission) in which use of swallow screening tool was undertaken. Owing to fluctuation in swallow function within a 24‐hour period, it is incumbent on researchers to specify the time period to direct clinical practice (i.e. use of different screening tools at different time periods post stroke) and to allow for comparisons of sensitivity versus other studies. Screening tools that were used in the outpatient setting or in the rehabilitation setting were excluded from the review.

Index tests

The ideal balance of sensitivity and specificity may vary according to the care setting. For example, a very sensitive screening test may be appropriate for untrained staff who have professional backup to rapidly identify false‐positives. No screening test identified or excluded swallowing difficulties with perfect accuracy. We were able to identify tests with the best ability to detect people with and without risk of aspiration from studies providing good quality evidence. The best performing swallow screening tools were the Bedside Aspiration test (Lim 2001a), the Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS) (Trapl 2007b), and the Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test (TOR‐BSST) (Martino 2009 Study 1). Although screening tests with larger sample sizes (n > 200) had smaller confidence intervals (CIs) in estimates of sensitivity and specificity, they had higher risk of bias than the best performing tests so are not among the recommended screening tests. For clinicians with a variety of consistencies available, the best performing water plus other consistencies test was GUSS (Trapl 2007b). Although GUSS offers different consistencies as part of the assessment and offers a consistency management plan for clinicians to implement, the consistencies used are limited to puree, water, and solids, and the test does not include all the consistencies identified in the International Dysphagia Diet Standardised Initiative (International Dysphagia Diet Std Initiative 2017). Therefore, this test may not be suitable for implementation across all healthcare settings. The best water‐only swallow screening test was TOR‐BSST (Martino 2009 Study 1). Although all tests demonstrate a combined highest sensitivity and specificity and low risk of bias across all domains, clinicians should be cautious in their interpretation of these findings, as these tests are based on single studies with small sample sizes, which limits the interpretation of estimates of reliability for these screening tests.

Sensitivity is similar for tools with a primary outcome of dysphagia or aspiration, but tools with dysphagia as their outcome perform better in terms of specificity. This may be due to the greater number of clinical signs of difficulty (e.g. chewing function) that may be observed in dysphagia compared to aspiration, making it more easily detected.

There is general agreement between index tests that some degree of behavioural assessment (e.g. alertness), together with oromotor assessment, was fundamental before progression to a test of oral intake (either various sizes of water bolus or water plus various consistencies). Generally, water plus various consistencies (n = 6) performed better than water‐only tools in terms of sensitivity and specificity. The small number of index tests that did not use direct patient assessment (e.g. used national stroke scales to identify risk of swallowing difficulty) did not consistently perform well.

Only a few studies gave direction on what food and drink consistencies should be given to an individual following the screen (e.g. GUSS; Trapl 2007b). These studies will be useful in healthcare settings, nationally and internationally, when an expert assessment or an instrumental assessment is not available.

The best performing index tests are included in the group carried out by nurses. Index tests carried out by other HCPs are less consistent. This may be due to confounding factors regarding the amount of training received by nursing staff within studies rather than a reflection on the type of index test or professional group undertaking the test. Of the 21 index tests undertaken by nurses, 17 (81.0%) recorded some form of training; for other HCPs, only four (25.0%) papers reported a training element. Furthermore, papers that reported training was required often failed to present the elements included in the training. In future studies, the type of training delivered should be reported.

Reference standard

Reference tests were defined as either expert clinical assessments (usually undertaken by speech and language therapists (SLTs)) or instrumental assessments. A variety of reference tests were included to capture patients who could access different instrumental assessments. However, the reliability of instrumental assessments used to diagnostically identify aspiration is of clinical concern.

Following the SLT opinion, we considered the Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability (MASA) as equivalent to an expert clinical assessment and included the seven studies that used MASA as a reference test. Tools that used the MASA or expert assessment for reference testing had a better combined sensitivity and specificity than tools that used instrumental tests of fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) or videofluoroscopy (VF). This may be due to the similarity between index tests and reference tests of MASA/expert assessment in that both rely on clinical observations rather than on instrumental assessment.

From summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) plots, which plot sensitivity versus (1‐specificity), index tests that used FEES as the reference test generally had higher sensitivity but similar specificity than index tests that used VF or MASA as the reference test combined with expert assessment. Most of the studies that used FEES or VF report sensitivity greater than 85% but poorer specificity than those that used MASA or expert assessments as the reference test. No studies were compared to scintigraphy, which remains mainly a research tool.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of evidence varied across included studies. The most common reasons for reduced quality was considerable heterogeneity between studies that affected our ability to combine and directly compare results.

Studies often failed to distinguish between dysphagia and aspiration as the primary outcome. Some did not routinely identify time between stroke onset or admission to hospital and time the screen was undertaken. Similarly, some studies failed to report time between index test and reference test, and the swallow may have improved or deteriorated in the interval between tests. Many studies failed to report the training required by different healthcare professionals to implement the screening tool.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

Strengths

This DTA undertook the literature search from an International perspective and included all relevant studies irrespective of language of publication. Therefore we can be assured that no relevant publications were excluded from our searches. We were able to identify the best performing tools within each category of swallow screening tools that used water alone, water plus other bolus consistencies, and other methods. We included as narrative studies trials that did not report statistical results.

Weaknesses

Apart from one screening tool that was assessed by two studies, all remaining screening tools were assessed by single studies. This hampered the possibility to perform any meaningful meta‐analysis. Only descriptive analyses grouped by general categories were presented. Studies often failed to distinguish between dysphagia and aspiration as the primary outcome. Most studies had small sample sizes, which limits interpretation of the estimates of reliability of the screening tests. Some did not routinely identify time between stroke onset or admission to hospital and time the screen was undertaken. Similarly, some studies failed to report time between the index test and the reference test, and the swallow may have improved or deteriorated in the interval between tests. Many studies failed to report the training required by different healthcare professionals to implement the screening tool. This has had an impact on the quality of this review. We performed no formal assessment of the overall quality of the evidence, for example, by using GRADE. We have not included any ongoing studies.

Applicability of findings to the review question

This review demonstrates that currently, high‐quality evidence from research is insufficient to provide conclusive results regarding the accuracy of bedside swallow screening tools in identifying aspiration associated with dysphagia in the acute stage of stroke.

Applicability of evidence

The review authors are aware of ongoing international studies that are currently unpublished and are not included as part of this review. However, this review does identify currently available swallow screening tools that screen with water and those that screen with a variety of consistencies to offer an ongoing food and drink consistency management plan that may be implemented in the clinical setting.

Implications for research

High‐quality, appropriately statistically powered studies are needed to evaluate the accuracy of a swallow screening tool in identifying aspiration associated with dysphagia in acute stages of stroke.

Future research studies should clearly define their primary outcomes. They should provide more detail regarding participant inclusion and exclusion criteria, and when a study includes individuals with differing underlying aetiologies that precipitate swallowing difficulties, these data should be reported separately.

Future studies should provide greater detail on participant location and timing of the swallow screening tool used post stroke or post admission. This, together with a description of participant characteristics and swallow severity, would allow researchers to identify the accuracy of a screening tool within different time frames, revealing alterations in swallow function post stroke onset.