Abstract

In 2020, individuals of all ages engaged in demonstrations condemning police brutality and supporting the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Research that used parent reports and trends commented on in popular media suggested that adolescents under 18 had become increasingly involved in this movement. In the first large-scale quantitative survey of adolescents’ exposure to BLM demonstrations, 4,970 youth (meanage = 12.88 y) across the United States highlighted that they were highly engaged, particularly with media, and experienced positive emotions when exposed to the BLM movement. In addition to reporting strong engagement and positive emotions related to BLM demonstrations, Black adolescents in particular reported higher negative emotions when engaging with different types of media and more exposure to violence during in-person BLM demonstrations. Appreciating youth civic engagement, while also providing support for processing complex experiences and feelings, is important for the health and welfare of young people and society.

Keywords: Black Lives Matter, adolescents, demonstrations, race

Following the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in 2020, over 8,000 mass demonstrations across the United States occurred in protest against police brutality and racial injustice and in support of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement (1). Youth engagement with the BLM movement appeared to increase during this time. A national poll found that 8% of parents reported that their adolescent children (ages 13 to 18) participated in a public demonstration related to structural racism and police brutality (2). Compared to 24% of White parents, 50% of Black parents reported that thinking about racism and police brutality caused stress for their adolescent, consistent with evidence that Black individuals are more concerned about racial injustice (3), more likely to be subjected to discriminatory practices (4), and experience more mental health problems following racial violence (5) than White individuals.

Scholars have long documented the importance of civic engagement for youth development. Civic engagement during adolescence can provide youth with an outlet for identity exploration, promote socioemotional competency, and contribute to sustained civic engagement across the lifespan, as well as strengthen feelings of agency, healing, and unity among traumatized communities (6, 7). At the same time, engagement may increase adolescents’ vulnerability to harm and negative emotions (6, 8, 9). The majority of quantitative studies on engagement with BLM demonstrations include parent reports about their children or adults’ (18+ years old) accounts of their own experiences. However, beginning in early adolescence, youth are less likely to share their activities and emotions with parents, and as a result there tends to be a discrepancy between parent and youth report of behavior, including media use (10) and emotions (11).

To better understand youth engagement with BLM, we surveyed 4,970 11 to 15 y olds enrolled in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study [ABCD Study; (12)]. We asked about engagement mode (media, social media, in-person, knowing others who attend demonstrations) as research demonstrates that individuals, particularly adolescents, vary in the ways they civically engage and that mode can impact individuals differently (13, 14). We asked about feelings experienced as a result of engagement (e.g., anger, fear, inspiration, hope) in light of work showing that experiences generally, and specifically within civic engagement contexts, may differentially impact emotions within valence (9, 15) (see SI Appendix for survey questions). We present descriptive analyses and examine potential differences in engagement and experiences between Black adolescents and adolescents from other racial/ethnic groups.

Methods

Respondents were 2,510 male (50.5%) and 2,460 female (49.5%) youth aged 11 to 15 y (M = 12.88, SD = 0.87). For racial/ethnic group membership, 2,986 respondents identified as White (60%), 487 Black (9.8%), 825 Hispanic (17%), 148 Asian (3%), and 524 multiracial/other (11%; see SI Appendix for more information about the multiracial/other group). Inverse probability of completion weighting ensured survey respondents were sociodemographically representative of the full ABCD Study sample. In analyses examining racial/ethnic group differences, Black adolescents were used as the reference group, given the focus of the BLM movement on ensuring justice and equity for Black individuals.

Results

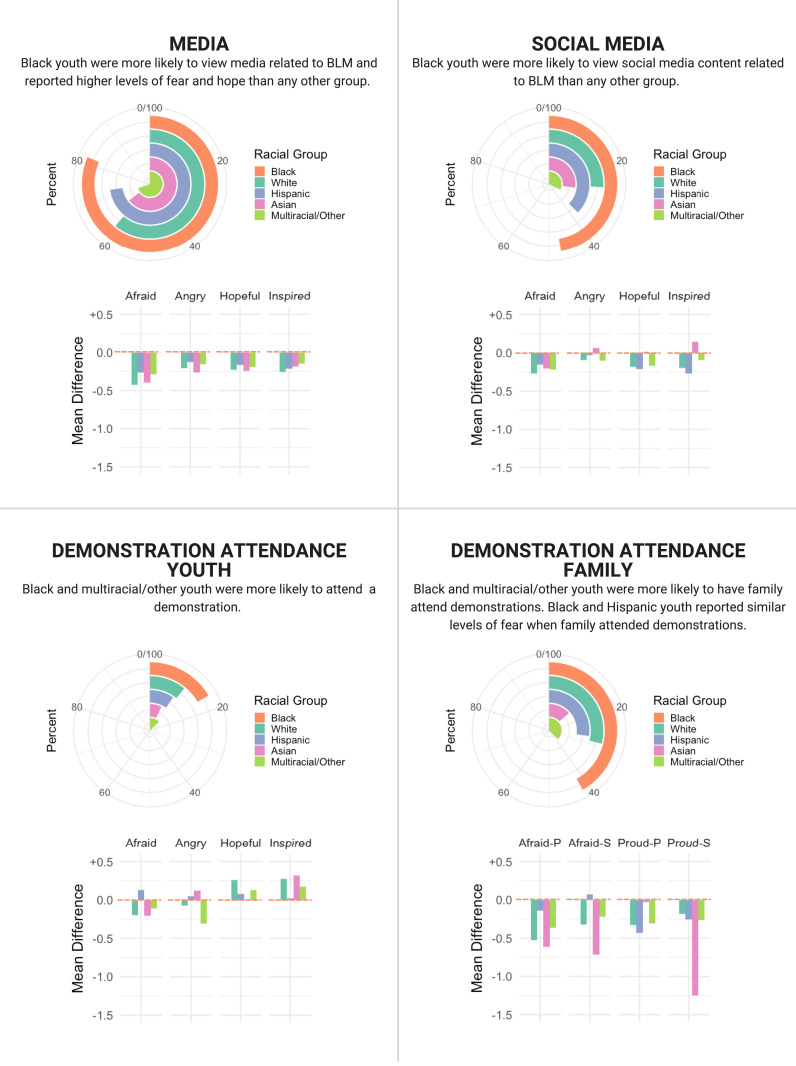

A sizable percent of adolescents engaged with the BLM movement (Fig. 1): 66% consumed TV/radio/Internet media, 30% used social media, 12% attended one or more demonstrations, and 35% reported knowing someone who attended a demonstration without them. Across media, social media, and in-person engagement, adolescents reported higher levels of positive (inspired: M = 2.48, SD = 1.16; hopeful: M = 2.64, SD = 1.12) than negative emotions (angry: M = 1.86, SD = 0.91; afraid: M = 1.57, SD = 0.61). For the 315 respondents who used media, social media, and attended demonstrations in person, levels of inspiration {F(2,626) = 6.30, 95% CI[0.04, 0.01]} and hope {F(2,626) = 6.32, 95% CI[0.04, 0.01]} were significantly higher when attending demonstrations in person than when engaging with media or social media, after controlling for mean engagement frequency. Levels of anger and fear did not significantly differ by engagement mode.* When thinking about parents or siblings attending BLM demonstrations without them, adolescents expressed feeling more pride (M = 3.21, SD = 0.98) than fear (M = 1.49, SD = 0.62). Adolescents who attended one or more BLM demonstrations witnessed demonstrators helping each other (49%), police helping demonstrators (29%), police using force (17%), and demonstrators perpetrating violence (13%).

Fig. 1.

Stacked donut plots display the frequency of engagement with TV/radio/Internet media, social media, in-person demonstration (recoded as attend/not attend for visualization), and family demonstration attendance (recoded to combine parent and sibling for visualization). Bar charts display the difference between the mean feelings for Black adolescents and each racial/ethnic group for each mode of engagement (0.0 on the y axis [orange] represents the Black adolescent mean; positive values indicate Black adolescents report lower levels of positive or negative feelings; negative values represent Black adolescents report higher levels of positive or negative feelings).

On several questions, Black adolescents reported more engagement and higher levels of positive and negative feelings than adolescents from other racial/ethnic groups (Fig. 1). Black adolescents were more likely to view BLM-related media {χ2 (5) = 468.4, P < 0.0001: Inverse-odds ratio (I-OR)White = 2.82, 95% CI[−1.30, −0.77]; I-ORHispanic = 1.64, 95% CI[−0.80, −0.20]; I-ORAsian = 2.44, 95% CI[−1.32, −0.46]; I-ORmultiracial/other = 1.92, 95% CI[−0.98, −0.33]} and use social media for BLM content {χ2 (5) = 687.3, P < 0.0001: I-ORWhite = 2.56, 95% CI[−1.15, −0.72]; I-ORHispanic = 1.49, 95% CI[−0.66, −0.15]; I-ORAsian = 2.38, 95% CI[−1.30, −0.45]; I-ORmultiracial/other = 1.89, 95% CI[−0.91, −0.35]} than adolescents from other racial/ethnic groups. When viewing media coverage of BLM, Black adolescents reported higher levels of fear (BWhite = −0.43, 95% CI[−0.54, −0.32]; BHispanic = −0.27, 95% CI[−0.40, −0.14]; BAsian = −0.39, 95% CI[−0.57, −0.22]; Bmultiracial/other = −0.29, 95% CI[−0.43, −0.14]) and hope (BWhite = −0.25, 95% CI[−0.38, −0.13]; BHispanic = −0.18, 95% CI[−0.33, −0.03]; BAsian = −0.27, 95% CI[−0.51, −0.02]; Bmultiracial/other = −0.21, 95% CI[−0.38, −0.04]) compared to adolescents from other racial/ethnic groups.

We highlight differences between Black and White adolescents based on research indicating Black and White individuals systematically differ in their views about and experiences with police and BLM (2, 16, 17). Compared to White adolescents, Black adolescents reported higher anger (BWhite = −0.22, 95% CI[−0.35, −0.10]) and inspiration (BWhite = −0.30, 95% CI[−0.42, −0.16]) when viewing BLM-related media; felt higher fear (BWhite = −0.25, 95% CI[−0.39, −0.12]), inspiration (BWhite = −0.22, 95% CI[−0.40, −0.05]), and hope (BWhite = −0.20, 95% CI[−0.37, −0.03]) when using social media for BLM content; attended more demonstrations (I-ORWhite = 1.89 (BWhite = −0.63), 95% CI[−0.92, −0.34])†; had a greater likelihood of witnessing police use of force at demonstrations (I-ORWhite = 3.33, 95% CI[−1.82, −0.66]) and demonstrators perpetrating violence (I-ORWhite = 3.57, 95% CI[−1.95, −0.63])‡; had a greater likelihood of parents (I-ORWhite = 1.56, 95% CI[−0.79, −0.10])§ attending demonstrations; had a greater likelihood of siblings (I-ORWhite = 1.64, 95% CI[−0.86, −0.12])¶ attending demonstrations; and, expressed higher levels of fear when parents (BWhite = −0.54, 95% CI[−0.82, −0.26])# and siblings (BWhite = −0.32, 95% CI[−0.61, −0.03]) attended demonstrations, as well as pride when parents attended demonstrations (BWhite = −0.30, 95% CI[−0.57, −0.02]). However, White compared to Black adolescents endorsed a greater likelihood of having friends attend demonstrations without them (ORWhite = 1.71, 95% CI[0.21, 0.86]).

Discussion

Adolescents reported high levels of engagement with the BLM movement, primarily through different modes of media. Contrary to portrayals of the BLM movement as harmful, adolescents on average reported positive emotions while engaging with the movement, especially when attending in-person demonstrations. However, engagement with the BLM movement was not wholly positive and differed in important ways between racial/ethnic groups.

While Black adolescents, compared to any other racial/ethnic group, reported more positive (e.g., feelings of hope and inspiration) aspects of their engagement, they also reported higher levels of negative feelings and experiences. For Black adolescents, it is important to consider the rewards and the risks of civic engagement. On the one hand, hope, inspiration, and anger can galvanize Black youth to take action and strive to eradicate the systems of oppression affecting Black communities (6). On the other hand, increased fear resulting from various modes of engagement and exposure to violence while attending demonstrations can have long-term impacts on their physical and mental health (6, 8). Thus, although the engagement of Black youth in movements germane to their racial identity and wellbeing can be empowering, it is important to create opportunities for them to process the stress and trauma related to these activities using culturally relevant methods (18).

The growing salience of the BLM movement has amplified the conversation about the future of US society and of the role to be played by all individuals, regardless of age or race/ethnicity. Youth are a critical part of this conversation (19), and we, as a society, need to provide more opportunities and proper support so that their voices are heard.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The ABCD Study is supported by the NIH and additional federal partners under awards U01DA041048, U01DA050989, U01DA051016, U01DA041022, U01DA051018, U01DA051037, U01DA050987, U01DA041174, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041028, U01DA041134, U01DA050988, U01DA051039, U01DA041156, U01DA041025, U01DA041120, U01DA051038, U01DA041148, U01DA041093, U01DA041089, U24DA041123, and U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners/. Additional support for this work was made possible from supplements to U24DA041123 and U24DA041147, the National Science Foundation (NSF 2028680), and Children and Screens: Institute of Digital Media and Child Development Inc. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/consortium_members/.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

*Racial/ethnic group did not moderate the within-subjects difference of engagement mode on feelings.

†Black adolescents were significantly more likely to attend one or more BLM demonstrations compared to Hispanic or Asian, but not multiracial/other adolescents.

‡Analyses with follow-up questions (e.g., experiences, feelings) controlled for the frequency of engagement.

§Black adolescents were significantly more likely to have parents attend BLM demonstrations without them compared to Hispanic or Asian, but not multiracial/other adolescents.

¶Black adolescents were significantly more likely to have siblings attend BLM demonstrations without them compared to Hispanic or Asian, but not multiracial/other adolescents.

#Black youth had significantly higher levels of fear when parents attended BLM demonstrations without them compared to Asian and multiracial/other, but not Hispanic youth.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2109860118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

The ABCD data used in this report is available at National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Data Archives, https://nda.nih.gov/study.html?&id=1225.

References

- 1.The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) , Demonstrations & Political Violence in America: New Data for Summer 2020. https://acleddata.com/2020/09/03/demonstrations-political-violence-in-america-new-data-for-summer-2020/. Accessed 3 January 2021.

- 2.Mott Poll , “Teen involvement in demonstrations against police brutality” (Mott Poll Rep., C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, Michigan Medicine) (2020).

- 3.Oosterhoff B., Wray-Lake L., Palmer C. A., Kaplow J. B., Historical trends in concerns about social issues across four decades among US adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 30 (suppl. 2), 485–498 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierson E., et al., A large-scale analysis of racial disparities in police stops across the United States. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 736–745 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtis D. S., et al., Highly public anti-Black violence is associated with poor mental health days for Black Americans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2019624118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anyiwo N., Palmer G. J., Garrett J. M., Starck J. G., Hope E. C., Racial and political resistance: An examination of the sociopolitical action of racially marginalized youth. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 35, 86–91 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennings L. B., Parra-Medina D. M., Hilfinger-Messias D. K., McLoughlin K., Toward a critical social theory of youth empowerment. J. Community Pract. 14, 31–55 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 8.First J. M., et al., Posttraumatic stress related to the killing of Michael Brown and resulting civil unrest in Ferguson, Missouri: Roles of protest engagement, media use, race, and resilience. J. Soc. Social Work Res. 11, 369–391 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stamps D., Mastro D., The problem with protests: Emotional effects of race-related news media. J. Mass Commun. Q. 97, 617–643 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fors P. Q., Barch D. M., Differential relationships of child anxiety and depression to child report and parent report of electronic media use. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 50, 907–917 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Los Reyes A., Kazdin A. E., Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychol. Bull. 131, 483–509 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang R., Data from "Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study (ABCD), Data Release: COVID Rapid Response Research (RRR) Survey Second data release #1225." NIMH Data Archive. https://nda.nih.gov/study.html?&id=1225. Accessed 7 January 2021.

- 13.Wray-Lake L., Abrams L. S., Pathways to civic engagement among urban youth of color. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 85, 7–154 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jugert P., Eckstein K., Noack P., Kuhn A., Benbow A., Offline and online civic engagement among adolescents and young adults from three ethnic groups. J. Youth Adolesc. 42, 123–135 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis M., Haviland-Jones J. M., Barrett L. F., Handbook of Emotions (Guilford Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reinka M. A., Leach C. W., Race and reaction: Divergent views of police violence and protest against. J. Soc. Issues 73, 768–788 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinka M. A., Leach C. W., Racialized images: Tracing appraisals of police force and protest. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 115, 763–787 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson R. E., Stevenson H. C., RECASTing racial stress and trauma: Theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in families. Am. Psychol. 74, 63–75 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watts R. J., Guessous O., “Sociopolitical development: The missing link in research and policy on adolescents” in Beyond Resistance! Youth Activism and Community Change: New Democratic Possibilities for Practice and Policy for America’s Youth, Cammarota J., Noguera P., Ginwright S., Eds. (Taylor & Francis, 2006), pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The ABCD data used in this report is available at National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Data Archives, https://nda.nih.gov/study.html?&id=1225.