Abstract

Background

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a leading infectious cause of hospitalization and death worldwide. Knowledge about the incidence and etiology of CAP in China is fragmented.

Methods

A multicenter study performed at 4 hospitals in 4 regions in China and clinical samples from CAP patients were collected and used for pathogen identification from July 2016 to June 2019.

Results

A total of 1674 patients were enrolled and the average annual incidence of hospitalized CAP was 18.7 (95% confidence interval, 18.5–19.0) cases per 10000 people. The most common viral and bacterial agents found in patients were respiratory syncytial virus (19.2%) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (9.3%). The coinfections percentage was 13.8%. Pathogen distribution displayed variations within age groups as well as seasonal and regional differences. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 was not detected. Respiratory virus detection was significantly positively correlated with air pollutants (including particulate matter ≤2.5 µm, particulate matter ≤10 µm, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide) and significantly negatively correlated with ambient temperature and ozone content; bacteria detection was opposite.

Conclusions

The hospitalized CAP incidence in China was higher than previously known. CAP etiology showed that differences in age, seasons, regions, and respiratory viruses were detected at a higher rate than bacterial infection overall. Air pollutants and temperature have an influence on the detection of pathogens.

Keywords: bacterial pneumonia, community-acquired pneumonia, environmental factor, etiology, respiratory tract infection, viral pneumonia

This study describes the epidemiological characteristics of community-acquired pneumonia in China, and provides the basis for the use of anti-infective drugs, vaccine development, and monitoring strategies.

Following the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) has remained a serious challenge for infectious disease prevention and control, and has caused high morbidity and treatment costs worldwide [1, 2]. Although the diagnosis and treatment of CAP have been improved over the past 2 decades, it has remained a health burden [3, 4]. Even in the United States, Canada, and other countries with high levels of medical care, CAP is a leading cause of death among infectious diseases [3].

The etiology of CAP is difficult to identify using clinical manifestations, imaging results, and routine laboratory test results. The distribution of major pathogens may vary from country to country. Recently, most of the data have been reported from western countries [5–8]. However, the last surveys of the etiology of CAP in China were carried out approximately 20 years ago [9, 10]. To gain additional insight into the epidemiology of CAP in China, estimated incidence and contemporary etiologic studies of CAP in the Chinese population are required. The investigation of the etiology of CAP is helpful to guide the use of anti-infective drugs and vaccines, and the formulation and implementation of respiratory infection prevention and control measures, so as to reduce the spread of respiratory viruses and bacteria. This will be an important part of global respiratory infection prevention and control as regards the frequent international travel of the Chinese population. Thus, we performed a prospective observational study of CAP etiology and estimated the incidence of CAP in China.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

We conducted a prospective observational study at 4 hospitals in 4 cities located in the east, south, west, and northwest regions of China, including Chengdu, Liaocheng, Dali, and Kashi (Supplementary Figure 1). Three different cohorts were defined. The first cohort was conducted in Chengdu across all age groups from July 2016 to June 2019. The second cohort was conducted for a 0- to 4-year-old age group in Chengdu and Liaocheng from July 2017 to June 2019. The third cohort included a ≥50-year-old age group in Chengdu, Dali, and Kashi from July 2017 to June 2019 (Supplementary Figure 2).

The hospitals selected to participate in the final study were all main large general hospitals in the regions, including Chengdu Fifth People’s Hospital in the Wenjiang District of Chengdu City, Liaocheng First People’s Hospital in Liaocheng City, Dali First People’s Hospital in Dali City, and Kashi First People’s Hospital in Kashi. These hospitals had the technical level to complete the project and receive the majority of local patients. During the study period, trained staff screened CAP patients for enrollment following uniform criteria for a diagnosis of CAP. Unified technical training, monthly teleconferences, enrollment reports, data audits, and annual study-site visits were conducted to ensure uniform procedures were being followed at the study sites. See the Supplementary Methods for detailed descriptions of study design, rationale, and overall conduct.

The criteria for a diagnosis of CAP were reported in the respiratory branch of the Chinese Medical Association Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of CAP [11]. A clinical diagnosis of CAP was established if a patient had any of the following: (1) symptoms of cough, expectoration, or original respiratory diseases that were recently aggravated, with the appearance of purulent sputum; (2) fever; (3) signs of pulmonary consolidation and/or moist rales; and/or (4) white blood cell count >10×109 cells/L or <4×109 cells/L; plus (5) chest radiograph that showed an infiltrative shadow or interstitial change. Patients were excluded if they had been recently hospitalized (<28 days for immunocompetent patients and <90 days for immunosuppressed patients), had been enrolled in other clinical investigation studies within the previous 28 days, or had a clear alternative diagnosis, including tuberculosis, lung tumors, noninfective pulmonary interstitial disease, pulmonary edema, atelectasis, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary eosinophilic infiltration, and/or pulmonary vasculitis.

The number of CAP patients with radiographic evidence in hospitals was found to be very large. Therefore, we selected 1 day (the 15th of each month) to collect patient samples that were included in this project. For example, in Wenjiang, Chengdu, there were 28030 CAP patients with radiographic evidence between July 2016 and June 2019, and 900 cases were included for pathogen detection in this study.

Patient Consent Statement

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral consent was processed by using a researcher-recorded oral consent template before providing information on the study, including sex, age, occupation, and date of onset. Only routinely obtained microbiology results were used and diagnostic strategy was not determined by the study design.

Specimen Collection and Laboratory Testing

Specimen collection and bacterial culture were performed according to standard methods [12]. Blood and urine samples were obtained from the patients as soon as possible after case presentation. In the case of patients with a productive cough, sputum was obtained. Pleural fluid, endotracheal aspirates, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples obtained for clinical care were analyzed. Only specimens obtained within 72 hours before or after admission were considered. Urinary antigen testing was performed for the detection of Legionella pneumophila and Streptococcus pneumoniae (BinaxNOW, Alere).

A real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay was performed using blood samples, pleural fluid, sputum, endotracheal aspirates, and quantified BAL specimens for the detection of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV; A and B), influenza virus (A, B, and 09fluH1), human rhinovirus (1–4), coronavirus (229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 [SARS-CoV-2]), parainfluenza virus (1–4), adenovirus, bocavirus, human metapneumovirus (HMPV), Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Legionella pneumophila, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae, as per previous reports [13–21].

Pathogen Detection

A bacterial pathogen was determined to be present if bacteria were detected in blood samples, sputum, pleural fluid, endotracheal aspirates, or BAL samples via culture, or in pleural fluid, endotracheal aspirates, or BAL samples via PCR assay; if Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, or L pneumophila were detected in sputum via PCR assay; or if L pneumophila or S pneumoniae were detected in urine via antigen detection.

A viral pathogen was determined to be present if viruses were detected in sputum, pleural fluid, endotracheal aspirates, or BAL samples via PCR assay.

Controls

In summer 2017 and winter 2018, we enrolled a sample of asymptomatic patients from Zigong, a city around Chengdu. Oropharyngeal swabs were obtained to assess the prevalence of respiratory pathogens among asymptomatic children and adults. Exclusion criteria were the same as those for patients with pneumonia, except that control patients were excluded if they exhibited fever or respiratory symptoms within 14 days before or after enrollment (based on information obtained during sample collection or if patients had received a live attenuated influenza vaccination within 7 days prior to enrollment).

Correlation Analysis of Related Environmental Factors

We collected ambient air pollutants data from Chengdu for the entire study period from China’s National Real-time Publishing Platform (http://106.37.208.233:20035/), including the daily 24-hour concentrations of particulate matter ≤10 µm (PM10), particulate matter ≤2.5 µm (PM2.5), ozone (O3), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and sulfur dioxide (SO2), and the monthly average concentration was calculated. Meteorological variables, including daily mean temperature (°C) and relative humidity (%) were obtained from the Sichuan Meteorological Service Center (http://sc.cma.gov.cn/), and the monthly average value for the weather variables were calculated.

Statistical Analysis

The differences in detection rates between different groups, including age and seasons, were compared using the χ2 test with the row×column table (McNemar test). Differences were considered statistically significant if P values were<.05.

Liner regression methods were fitted to explore the association of environmental factors with the positive rate of bacterial infection and virus infection during the same period [22]. The correlation coefficients with P values were used to assess the associations. Generalized additive models were used to derive the estimates adjusted for environmental factors.

Estimated annual incidence rates of hospitalization for CAP according to year of study and detected pathogen were analyzed based on 5000000 person-years of observation. Pathogen-specific incidence is calculated for the patients who showed radiographic evidence of pneumonia during the incidence period.

Research Questions and Outcome Measures

The incidence rate of CAP is estimated by the data of this study. The positive rate, age, and seasonal differences of each pathogen were counted and analyzed. Related environmental factors of CAP pathogen distribution were assessed.

RESULTS

Study Population

We conducted a multicenter study, and a total of 1674 patients were enrolled, including 900 patients spanning all ages in Chengdu (first cohort), 383 patients <5 year old in Liaocheng (second cohort), and 129 and 262 patients >50 years old in Dali and Kashi, respectively (third cohort) (Supplementary Table 1). All patients showed radiographic evidence of pneumonia.

Epidemic and Pathogen Distribution of CAP Using a Single-Center Survey in Chengdu

Between July 2016 and June 2019, 28030 CAP patients with radiographic evidence were diagnosed in Chengdu Fifth People’s Hospital located in the Wenjiang District of Chengdu City, which provides medical services to approximately 526000 people in the surrounding area (Supplementary Table 2). All patients were asked if they have symptoms of cough, expectoration, or original respiratory diseases that were recently aggravated, with the appearance of purulent sputum, and tested for fever, signs of pulmonary consolidation and moist rales, white blood cell count, radiographic examination of the chest and tuberculosis, lung tumors, noninfective pulmonary interstitial disease, pulmonary edema, atelectasis, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary eosinophilic infiltration, and pulmonary vasculitis, and then CAP was diagnosed according to the judgment criteria. During 2016–2019, 59.8% (538/900) of the enrolled patients were male, and the median age was 23.4 years (interquartile range, 1–54.0 years). The average annual incidence of hospitalized CAP was 177.6 cases per 10000 people (95% confidence interval [CI], 100.0–250.0). Pathogen-specific incidences ranged between 0.1 (95% CI, .0–.1) and 10.8 (95% CI, 10.5–11.0) per 10000 people (Supplementary Table 3).

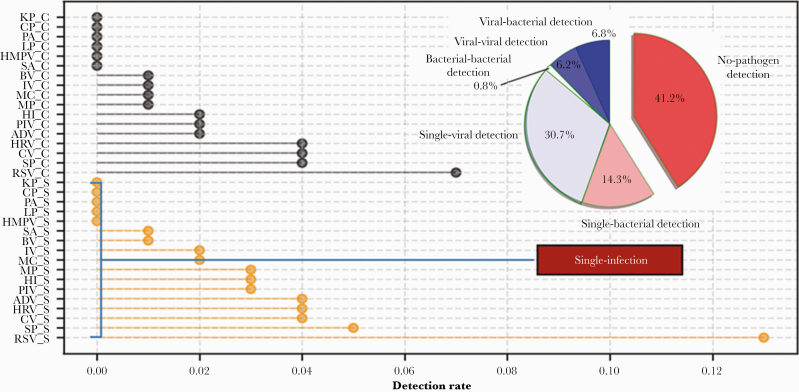

Overall, pathogens were identified in 58.8% (528/900) of patients in Chengdu (Figure 1). Single-viral and single-bacterial pathogens were detected in 30.7% and 14.3% of patients, respectively, whereas multiple pathogen co-detection was found in 13.8% of patients, including viral-bacterial (6.8%), viral-viral (6.2%), and bacterial-bacterial (0.8%). When monoinfections and coinfection were considered at the same time, RSV was the major cause of CAP (19.2% of patients), followed by S pneumoniae (9.3%), coronavirus (8.3%), human rhinovirus (7.4%), adenovirus (5.3%), parainfluenza virus (5.0%), H influenzae (4.8%), M pneumoniae (3.4%), M catarrhalis (3.1%), influenza virus (2.4%), bocavirus (1.4%), S aureus (1.0%), HMPV (0.8%), L pneumophila (0.7%), P aeruginosa (0.2%), K pneumoniae (0.1%), and C pneumoniae (0.1%). SARS-CoV-2 was not detected among the enrolled patients.

Figure 1.

Distribution of pathogens detected in 900 patients with community-acquired pneumonia from Chengdu, China, between July 2016 and June 2019. Abbreviations: ADV, adenovirus; BV, bocavirus; C, co-infection; CP, Chlamydia pneumoniae; CV, coronavirus; HI, Haemophilus influenzae; HMPV, human metapneumovirus; HRV, human rhinovirus; IV, influenza virus; KP, Klebsiella pneumoniae; LP, Legionella pneumophila; MC, Moraxella catarrhalis; MP, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; PA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; PIV, parainfluenza virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; S, single infection; SA, Staphylococcus aureus; SP, Streptococcus pneumoniae.

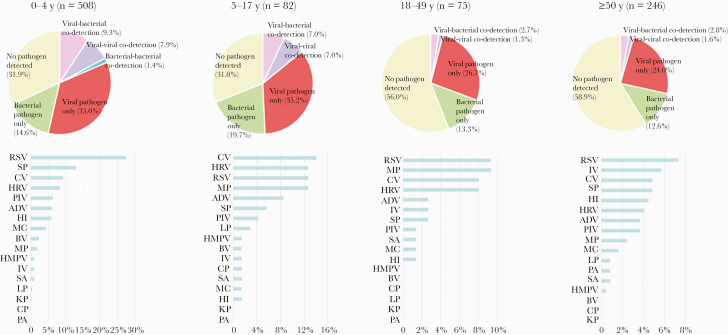

The etiology differed across ages (Figure 2). Overall, pathogen detection rates in the lower age groups were higher than the older age groups, including single viral and bacterial infection as well as coinfections with multiple pathogens (P<.05). In the younger age groups (0–4 years old and 5–17 years old), 49.6% and 54.9% of patients, respectively, showed at least 1 pathogen vs 40.0% and 36.6% in the older age groups (18–49 years old and ≥50 years old), respectively. RSV was the major etiology in the age groups 0–4, 18–49, and ≥50 years, and coronavirus in the 5–17 age group. Streptococcus pneumoniae, human rhinovirus, M pneumoniae, and influenza virus were the second-most frequently detected agents in the 0–4, 5–17, 18–49, and ≥50-year age groups, respectively (Figure 2). The older the age group, the lower the detection rate of RSV (27.36%, 12.68%, 9.33%, and 7.32% in the 0–4, 5–17, 18–49, and ≥50-year age groups, respectively), and the higher the detection rate of influenza virus (0.98%, 1.41%, 2.67%, and 5.69% in the 0–4, 5–17, 18–49, and ≥50-year age groups, respectively) (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 2.

Pathogen distribution across different age groups among 900 patients with community-acquired pneumonia from Chengdu, China, between July 2016 and June 2019. Abbreviations: ADV, adenovirus; BV, bocavirus; CP, Chlamydia pneumoniae; CV, coronavirus; HI, Haemophilus influenzae; HMPV, human metapneumovirus; HRV, human rhinovirus; IV, influenza virus; KP, Klebsiella pneumoniae; LP, Legionella pneumophila; MC, Moraxella catarrhalis; MP, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; PA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; PIV, parainfluenza virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SA, Staphylococcus aureus; SP, Streptococcus pneumoniae.

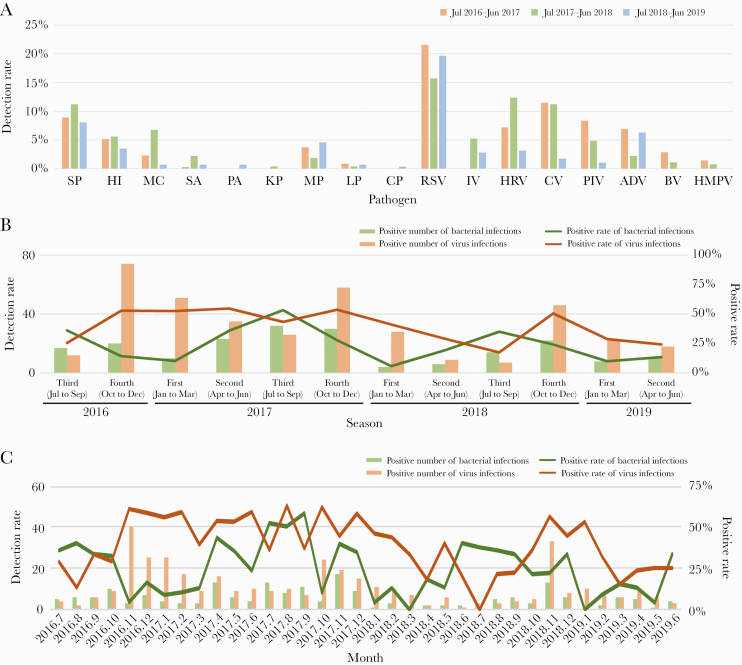

The dominant pathogens found in CAP in Chengdu were not observed to differ in years; however, seasonal differences were detected. RSV was the most frequently detected viral agent across all 3 epidemic years, and S pneumoniae was the most frequently identified bacterial pathogen across all 3 epidemic years (Figure 3A). Bacterial infections reached peak during the third quarter of the year and was lowest during the first quarter of the year (in all 3 years), whereas viral infections showed a less significant seasonal trend (Figure 3B). The detection rate of viruses decreased in the third quarter of the year, especially in January, November, and December (Figure 3C). Influenza virus infection peaked in January (Supplementary Figure 3). Likewise, RSV, coronavirus, adenovirus, and HMPV showed a similar trend (Supplementary Figure 3); additional peaks occurred in other months. However, there was no obvious peak of a single bacterium (Supplementary Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Comparison of positive rates of the different pathogens observed in patients with community-acquired pneumonia across 3 epidemic years based on year (A), quarter (B), and month (C). Abbreviations: ADV, adenovirus; BV, bocavirus; CP, Chlamydia pneumoniae; CV, coronavirus; HI, Haemophilus influenzae; HMPV, human metapneumovirus; HRV, human rhinovirus; IV, influenza virus; KP, Klebsiella pneumoniae; LP, Legionella pneumophila; MC, Moraxella catarrhalis; MP, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; PA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; PIV, parainfluenza virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SA, Staphylococcus aureus; SP, Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Multicentric Epidemic Characteristics of CAP Etiology

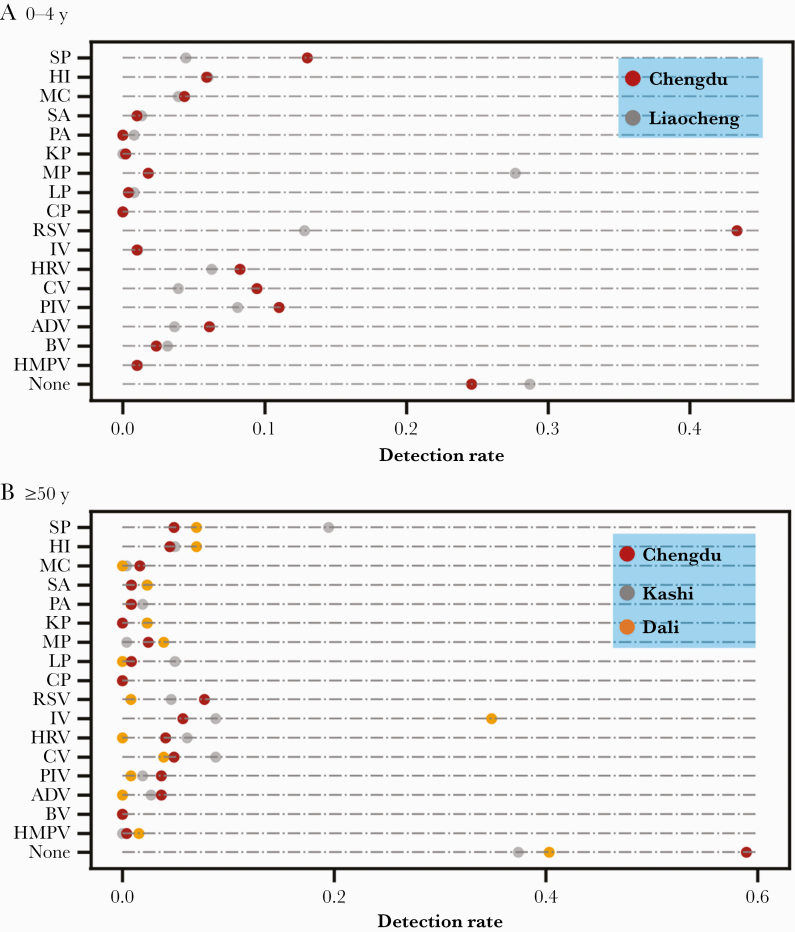

A 2-center study of CAP pathogens in the age group 0–4 years was performed between July 2017 and June 2019, with 508 and 383 patients recruited from Chengdu and Liaocheng, respectively. There were 16 pathogens detected in the patients from both centers (Figure 4A). RSV was the major etiology in Chengdu (27.4%) vs M pneumoniae in Liaocheng (27.6%). SARS-CoV-2 was not detected among the enrolled patients.

Figure 4.

Distribution of pathogens detected in patients aged 0–4 years (A) and ≥50 years (B) with community-acquired pneumonia in different cities in China. Abbreviations: ADV, adenovirus; BV, bocavirus; CP, Chlamydia pneumoniae; CV, coronavirus; HI, Haemophilus influenzae; HMPV, human metapneumovirus; HRV, human rhinovirus; IV, influenza virus; KP, Klebsiella pneumoniae; LP, Legionella pneumophila; MC, Moraxella catarrhalis; MP, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; PA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; PIV, parainfluenza virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SA, Staphylococcus aureus; SP, Streptococcus pneumoniae.

In addition, we performed a 3-center study of CAP pathogens in the ≥50-year-old age group between July 2017 and June 2019. There were 246, 129, and 262 patients recruited in Chengdu, Dali, and Kashi, respectively, and 14, 11, and 14 pathogens were detected, respectively (Figure 4B). The major etiologies in Chengdu, Dali, and Kashi were RSV (58.9%), influenza virus (34.9%), and S pneumoniae (19.5%). SARS-CoV-2 was not detected among the enrolled patients.

Control

Among the 595 asymptomatic control patients, 144 (24.2%) were 0–4 years of age, 271 (45.6%) were 5–17 years of age, 86 (14.5%) were 18–49 years of age, and 94 (15.8%) were ≥50 years of age (Supplementary Table 4). Among asymptomatic control patients, 2.6% and 1.2% of the age groups 5–17 and 18–49 years, respectively, tested positive for M pneumoniae, which was significantly lower than the proportion of CAP patients within the same age groups. Human rhinovirus was detected in 2.1% and 0.7% of the 0-to 4-year-old and 5- to 17-year-old controls, respectively, which was significantly lower than the proportion of CAP patients within the same age groups. No other pathogens were detected among the controls.

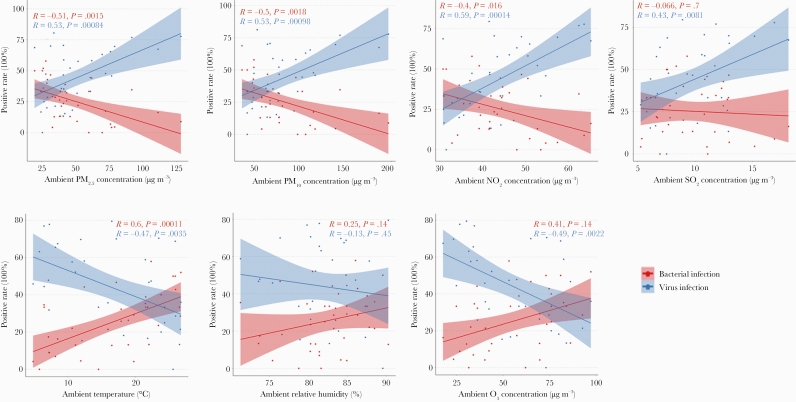

Environmental Factors of CAP Pathogen Distribution

Based on correlation analysis, the total detection rate of virus was significantly positively correlated with the 4 kinds of air pollutants, including PM2.5, PM10, NO2, and SO2, and significantly negatively correlated with ambient temperature and O3 content; bacteria detection was opposite (Figure 5, Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 5.

Association between positive rates of bacterial and viral infection and environmental factors (air pollutants and weather variables) across 3 epidemic years in Chengdu, China. Abbreviations: NO2, nitrogen dioxide; O3, ozone; PM2.5, particulate matter ≤2.5 µm; PM10, particulate matter ≤10 µm; SO2, sulfur dioxide.

Among the 17 pathogens, M pneumoniae, RSV, and H influenzae were most affected by weather variables (temperature, relative humidity, and O3). In addition, a significant correlation was observed between influenza virus and temperature. Overall, as weather variables increased, the rates of bacterial infection increased and virus detection decreased (Supplementary Figure 5). Bocavirus, HMPV, M pneumoniae, RSV, coronavirus, and parainfluenza virus were most affected by air pollutants (PM2.5, PM10, NO2, and SO2). Overall, as air pollutants increased, the rates of viral infection increased and bacterial detection decreased (opposite of weather variables) (Supplementary Figure 5).

SO2 showed the highest impact on the detection rate of bacteria and viruses; a 10 μg/m3 increase of SO2 led to a 4.20% increased rate of virus detection and a 21.73% increased rate of bacteria detection (Supplementary Table 6). The detection rates of bacteria (0.76%) increased and virus (1.11%) decreased when the temperature increased by 1°C (Supplementary Table 6).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we revealed the characteristics of CAP etiology in the Chinese population and the results demonstrate the differences in pathogens between regions and age groups. The detection rates of RSV in younger age groups were higher than in older age groups. Therefore, RSV is the key to reduce the CAP incidence in children. However, older age groups showed higher detection rates of influenza virus, which underscores the need for improving influenza vaccine uptake as well as vaccine effectiveness in adults and the elderly.

Our study found that S pneumoniae, H influenzae, M pneumoniae, and M catarrhalis were the main bacterial pathogens present in the enrolled patients, which was consistent with the results of 2 previous studies carried out in 2003–2004 and 2004–2005, and was supported by a small-scale survey data collected during the same period [23, 24]. Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major bacterial pathogen that causes CAP worldwide [5, 6, 25]. Pneumococcal vaccination should be focused on children and the elderly, as the detection rates of S pneumoniae in these 2 age groups were higher than in middle-aged groups. In our previous investigation, 3.85% of patients with severe pneumonia, due to unknown causes, tested positive for the L pneumophila serogroup 1 antigen [26]. In the present study, Legionella was detected in 3 cities, suggesting that Legionnaires’ disease may be an underestimated disease in China.

Previous studies on the relationship between respiratory viral infectious diseases and temperature have shown that increasing temperature can reduce the ability to spread both SARS and influenza, but not COVID-19 [22, 27, 28]. In the present study, increased temperature reduced the detection rate of viruses but increased the detection rate of bacteria. These findings suggest the occurrence of 2 types of infectious diseases during seasonal changes. A previous study presented a hypothesis as to why warmer seasons reduce the spread of viruses, which included higher vitamin D levels that may result in better immune responses [29]. The results of this study suggest that low temperature is helpful for virus survival and transmission, whereas bacteria prefer higher temperature, which is consistent with the difference of temperature sensitivity between these 2 types of pathogens.

Air pollution, including PM2.5, PM10, NO2, and SO2, have a serious impact on human health and increase the risk of hospital admission due to respiratory diseases [29]. However, in the present study, the total detection rate of bacteria was significantly negatively correlated with air pollutants, which may be related to the fact that generally people wear masks during high pollution days. This result is supported by our previous data that showed wearing masks could reduce bacterial infections from sources of air pollution [30]. One limitation of the present study was that no data on the incidence rates of CAP in different age groups were obtained. However, the overall incidence rate was similar to the incidence rate reported in the United States [5, 6]. This limitation might be attributed to the year and region that the analyses were performed, differences in the populations studied, and the differing criteria of CAP, as defined by different studies. Another limitation was that the detection methods of this study covered a limited number of CAP pathogens. Endemic fungal diseases (such as histoplasmosis), melioidosis, and other pathogens (such as Q fever) that are common in China (or at least in some regions) were not within the scope of the study. In the future study, more advanced detection methods should be included, such as broad-spectrum pathogen screening technologies, metagenomics next-generation sequencing technology and so on.

In conclusion, our study has provided a better understanding of the incidence, etiology, and related environmental factors of CAP in China, which is conducive to the clinical diagnosis and treatment, epidemiological monitoring, disease burden assessment, prevention, and control of CAP. In the future, it will be necessary to carry out nationwide routine monitoring to grasp the incidence and pathogenic changes of CAP in real time, followed by targeted prevention and control measures.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Elsevier Language Editing Services for language editing.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Pathogen Monitoring Capability Improvement Project from the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (grant number 131031102000150003 to B. K.); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81671985 to T. Q.); and the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (grant number 2018ZX10712001-007 to T. Q.) from the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China, Beijing Science and Technology Planning Project (grant number Z201100005420010 to H. T.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Prina E, Ranzani OT, Torres A.. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet 2015; 386:1097–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutiérrez F, Masiá M, Mirete C, et al. The influence of age and gender on the population-based incidence of community-acquired pneumonia caused by different microbial pathogens. J Infect 2006; 53:166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJL, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, et al. GBD 2013 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990-2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet 2015; 386:2145–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold FW, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, et al. CAPO authors. Mortality differences among hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia in three world regions: results from the Community-Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) International Cohort Study. Respir Med 2013; 107:1101–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. CDC EPIC Study Team. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:415–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, et al. CDC EPIC Study Team. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:835–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charles PG, Whitby M, Fuller AJ, et al. Australian CAP Study Collaboration. The etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in Australia: why penicillin plus doxycycline or a macrolide is the most appropriate therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:1513–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cillóniz C, Ewig S, Polverino E, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia in outpatients: aetiology and outcomes. Eur Respir J 2012; 40:931–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tao LL, Hu BJ, He LX, et al. Etiology and antimicrobial resistance of community-acquired pneumonia in adult patients in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012; 125:2967–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Chen M, Zhao T, et al. Causative agent distribution and antibiotic therapy assessment among adult patients with community acquired pneumonia in Chinese urban population. BMC Infect Dis 2009; 9:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao B, Huang Y, She DY, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Chinese Thoracic Society, Chinese Medical Association. Clin Respir J 2018; 12:1320–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, Carroll KC.. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 11th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. CDC protocol of realtime RTPCR for swine influenza A (H1N1). 2009. https://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/CDCrealtimeRTPCRprotocol_20090428.pdf. Accessed 4 June 2016.

- 14.Chidlow GR, Harnett GB, Shellam GR, Smith DW.. An economical tandem multiplex real-time PCR technique for the detection of a comprehensive range of respiratory pathogens. Viruses 2009; 1:42–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu A, Colella M, Tam JS, et al. Simultaneous detection, subgrouping, and quantitation of respiratory syncytial virus A and B by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41:149–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dare RK, Fry AM, Chittaganpitch M, et al. Human coronavirus infections in rural Thailand: a comprehensive study using real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J Infect Dis 2007; 196:1321–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van de Pol AC, van Loon AM, Wolfs TF, et al. Increased detection of respiratory syncytial virus, influenza viruses, parainfluenza viruses, and adenoviruses with real-time PCR in samples from patients with respiratory symptoms. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:2260–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heim A, Ebnet C, Harste G, Pring-Akerblom P.. Rapid and quantitative detection of human adenovirus DNA by real-time PCR. J Med Virol 2003; 70:228–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu X, Chittaganpitch M, Olsen SJ, et al. Real-time PCR assays for detection of bocavirus in human specimens. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:3231–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maertzdorf J, Wang CK, Brown JB, et al. Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay for detection of human metapneumoviruses from all known genetic lineages. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42:981–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang LX, Ren HY, Zhou HJ, et al. Simultaneous detection of 13 key bacterial respiratory pathogens by combination of multiplex PCR and capillary electrophoresis. Biomed Environ Sci 2017; 30:549–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao Y, Pan J, Liu Z, et al. No association of COVID-19 transmission with temperature or UV radiation in Chinese cities. Eur Respir J 2020; 55:2000517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao Z, Yuan X, Wang L, et al. The incidence and etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in fever outpatients. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2012; 237:1256–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu YF, Gao Y, Chen MF, et al. Etiological analysis and predictive diagnostic model building of community-acquired pneumonia in adult outpatients in Beijing, China. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13:309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engholm DH, Kilian M, Goodsell DS, et al. A visual review of the human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2017; 41:854–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin T, Ren H, Chen D, et al. National surveillance of Legionnaires’ disease, China, 2014–2016. Emerg Infect Dis 2019; 25:1218–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaakkola K, Saukkoriipi A, Jokelainen J, et al. KIAS-Study Group. Decline in temperature and humidity increases the occurrence of influenza in cold climate. Environ Health 2014; 13:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan KH, Peiris JS, Lam SY, et al. The effects of temperature and relative humidity on the viability of the SARS coronavirus. Adv Virol 2011; 2011:734690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aranow C. Vitamin D and the immune system. J Investig Med 2011; 59:881–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qin T, Zhang F, Zhou H, et al. High-level PM2.5/PM10 exposure is associated with alterations in the human pharyngeal microbiota composition. Front Microbiol 2019; 10:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.