Abstract

In 2019, the World Health Organization listed vaccine hesitancy, defined as the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate against preventable infectious diseases, as one of the top ten threats to global health. To address hesitancy, we must focus our attention on building vaccine confidence, trust in the vaccine itself, in providers who administer vaccines, and in the process that leads to vaccine licensure and the recommended vaccination schedule. Building vaccine confidence, particularly in communities that have higher levels of distrust of vaccines and low vaccination coverage rates, is a critical public health priority, particularly in the current climate as the United States and the global public health community grapple with the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. In this commentary, we focus on the central role that pharmacists play in promoting the health and wellness of the local communities in which they are embedded, how they are one of the most trusted sources for their communities when it comes to health information and care, and their unique position in making a profound contribution to building vaccine confidence. We propose to arm all health professionals with a tool, the ASPIRE framework, which serves as a series of actionable steps to facilitate conversations with communities. This framework is intended to assist pharmacists in communicating with community members who may have concerns about vaccines by sharing trustworthy health information about vaccines to increase vaccine adoption. We conclude that it is insufficient to merely relay accurate health information about vaccines to the public and expect dramatic increases to vaccination rates. Accurate health information needs to be conveyed by trusted sources. Open engagement and dialogue layered on top of fundamental facts and messages are central to building confidence. Pharmacists and other providers can use tools such as ASPIRE to guide their conversations with community members to increase vaccine adoption.

Key Points.

Background

-

•

Vaccine hesitancy is a major health threat that can undermine communities’ ability to attain herd immunity to protect against preventable illnesses.

-

•

Pharmacists are integral to promoting the health and wellness of their communities, including the delivery of vaccines.

-

•

They are trusted health information sources in the communities in which they are embedded.

Findings

-

•

There is a lack of simple tools to assist pharmacists in engaging with conversations about vaccines with community members.

-

•

We developed the ASPIRE framework, a 6-step action list, to support pharmacists in communicating with their community members who may have concerns about vaccines, sharing trustworthy health information with them about vaccines, and increasing vaccine adoption.

Pharmacists play a central role in promoting the health and wellness of the local communities in which they are embedded. Pharmacies are an integral part of communities across the nation, particularly in rural areas of the United States,1 and pharmacists are one of the most trusted sources for their communities when it comes to health information, health care, addressing vaccine concerns, answering questions, correcting misinformation, and strongly recommending vaccination.2, 3, 4, 5 Since the H1N1 influenza pandemic over a decade ago, pharmacists and pharmacies are increasingly integrated to deliver vaccinations.6 Before the H1N1 response, unlike hospitals and other health care facilities, many pharmacies did not have partnerships with public health. The H1N1 response changed this and moved public health officials to seek new partnerships. Pharmacies answered the call, offering convenience, accessibility, extended hours of operation, and health professionals who are licensed to vaccinate.

Pharmacies are uniquely positioned to meet the health care needs of the communities that they serve, given their strategic locations and flexible hours. Pharmacy locations are within reach of most Americans, averaging 2.11 pharmacists per 10,000 individuals in the United States.7 Moreover, approximately 90% of the population lives within 5 miles of a pharmacy.4 Pharmacists, particularly those who live and work in their communities, are often trusted sources of information and are relatively more accessible to patients (appointments are not needed to walk in to pick up medications) compared with other health professionals.

Vaccine confidence is defined as trust in the vaccine itself, in providers who administer vaccines, and in the process that leads to vaccine licensure and the recommended vaccination schedule. Building confidence requires a collective effort from all health care providers who engage with patients and communities. Pharmacists’ confidence in these areas and their ability to communicate effectively to the community is a key factor to building vaccine confidence.8 Pharmacists are often viewed as trusted sources of health information.5 As a trusted source, they are key actors involved in establishing, maintaining, and building confidence in vaccines because their credibility (expertise, trustworthiness, caring) can influence whether individuals accept health advice.9, 10, 11 It is important to equip trusted sources with the information and resources that they need to engage in vaccine conversations. Trust, attitudes and beliefs, health care provider confidence, and the information environment on vaccines are key factors that influence vaccine confidence.8

ASPIRE to have vaccine conversations

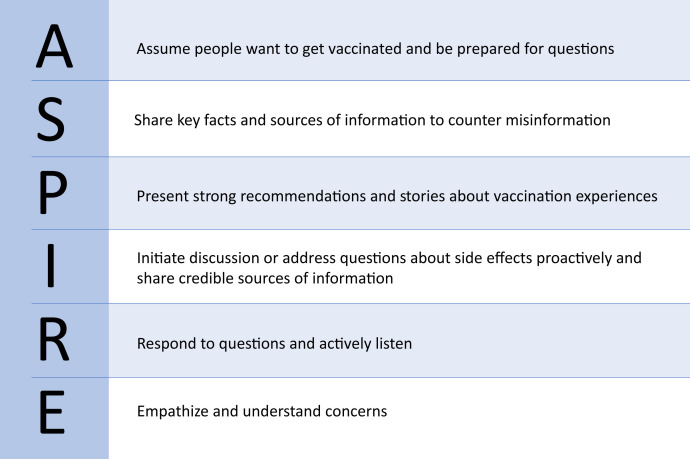

Toward this end, we offer a framework, ASPIRE, for pharmacists to effectively engage in vaccine conversations with their patients (Figure 1 ). Pharmacists can

-

•

assume that people want to get vaccinated and be prepared for questions,

-

•

share key facts and sources of information to counter misinformation,

-

•

present strong recommendations to vaccinate and stories about vaccination experiences,

-

•

initiate discussion or address questions about adverse effects proactively and share credible sources of information,

-

•

respond to questions and actively listen, and

-

•

empathize and understand concerns.

Figure 1.

ASPIRE communication framework for public engagement in vaccine messaging

Understanding hesitancy in communities is critical to maximizing community immunity by convincing those who remain unvaccinated to get vaccinated.12 Pharmacists work off protocols. The ASPIRE framework may be a useful protocol for patient engagement.13

-

•

Pharmacists can assume that people want to get vaccinated and be prepared for questions. Hearing from multiple trusted sources and having repeated conversations with patients are needed to influence the “moveable middle,” those in the population who can change their mind or who have not yet made up their mind about vaccination. Given the concerns around coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines, those hesitant to vaccinate often have many questions and concerns that can be effectively addressed by their pharmacist. Now that one COVID-19 vaccine is licensed for use and boosters are recommended for subpopulations, individuals continue to have questions about what is recommended for them.14 , 15

-

•

Pharmacists have been trained on what, when, and how to administer recommended vaccines. While doing so, they can share key facts and credible sources of information to counter misinformation. Many communities across the nation have been confused by messages about the pandemic and vaccines. Guidance on masks comes up top of mind—wear a mask, do not wear a mask, and wear a mask under certain circumstances.16 Moreover, early on in the U.S. vaccination program, in Spring 2021, confusion about where and how to access vaccination appointments flooded communities, as priority groups varied across the 64-jurisdictions in the nation, and not all states, cities, and localities followed national guidelines for priority groups.17

-

•

Individuals need to engage across multiple accessible channels and hear messages multiple times from various trusted sources. Pharmacists are an important touch point, and they can present strong recommendations to vaccinate and stories about vaccination experiences. Pharmacies offer a convenient and safe environment to have meaningful conversations in a familiar setting where patient consumers are comfortable asking questions within their own neighborhoods. Many pharmacists are already doing so as part of the nation’s COVID-19 pandemic response.18, 19, 20 Not only are pharmacies offering vaccines, but some are also holding special events or providing incentives for vaccination among their communities.21

-

•

The roles of the pharmacy and pharmacist have expanded beyond dispensing medications at the corner drugstore to delivering public health prevention and primary care.22 Pharmacists can proactively initiate conversations with their patients about vaccines, share credible sources of information, and engage with patients. Pharmacies today are hubs for consumer health care products and patient services, delivering simple, yet cost-effective interventions and preventive services (e.g., vaccination services, blood pressure screenings, smoking cessation programs, diabetes management) through a care model that supports population health while seeking to improve individual outcomes and control health care costs.22, 23, 24 Nearly half (48%) of community pharmacy customers have used at least one health and wellness–oriented service provided by their pharmacy in 2020, up 5% from 2019.24

-

•

For many communities, particularly among adults who may not have a regular primary care provider or live in a rural area where few providers are available, pharmacists serve as the primary care provider—managing medications, vaccinating community members, serving as a health educator, and as a trusted counsel on prevention and wellness. Pharmacists are well positioned to respond to patients’ questions and actively listen. Picking up routine medications from the pharmacist may be the only touchpoint with a health professional for those who do not regularly see a primary care provider. Therefore, these interactions offer a teachable opportunity to serve as a regular and familiar source of health information.

-

•

Trusted relationships between patients and their pharmacists are cultivated over years through repeated visits to pick up medications. This opportunity for pharmacists’ voices to resonate as vaccine advocates is unique. Pharmacists can use this safe space to share accurate health messages, empathize with patients’ concerns, and engage in dialogue about vaccination regularly.

Although the ASPIRE framework has yet to be validated, it can be used broadly as a guide to engage with the community and draws from much existing knowledge.25 Recent frameworks for effective conversations build on fundamental principles for effective communication (e.g., ensuring that materials are accessible, actionable, credible and trusted, relevant, timely, and understandable) while also providing context for vaccine conversations (e.g., be credible and clear and express empathy and show respect, while also meeting people where they are).25 , 26 The APSIRE framework builds on these common principles for effective conversations, tips for speaking, COVID-19 messaging, and existing toolkits and resources.27, 28, 29 It supports strategies for pharmacists who are trusted messengers with roots in communities.

Conclusion

Science, innovation, and public and private-sector collaboration enabled multiple vaccines for use in arguably the worst public health disaster in the modern era.30 , 31 This pandemic has been characterized by an infodemic of misinformation, an excessive amount of information that spread and confused much of the population. A constant flood of information can muddy the waters as it can be difficult to discern what is truth and what is conjecture, all of which can be confusing and can affect public vaccine confidence. Naturally, many patients need guidance in sorting through multiple streams of sometimes conflicting information. Trusted sources can be useful in managing this process and “refereeing” conflicting messages. (A. K. Shen, unpublished data, 2021)

For years, vaccine hesitancy was addressed by providing facts and correcting misconceptions. This long-standing strategy addressed some concerns in the community; however, the issues at hand are multi-faceted and complicated.6 , 12 Alan Leshner, former Chief Executive Officer of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, recently wrote in a perspective on trust and science, “Don’t just explain: engage.”32 Ultimately, health professionals must fully engage their communities in a meaningful way with tailored messages from credible and trusted sources. Pharmacists, who are anchored in their communities across the nation are essential to increasing vaccine confidence and can play a central role in what can be characterized as a “glocal” problem—a global issue that needs to be addressed at the local level.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Charlotte Moser and Stephan Foster for their thoughtful review of this manuscript.

Biographies

Angela K. Shen, ScD, MPH, Visiting Scientist, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Vaccine Education Center, Philadelphia, PA; Senior Fellow, Leonard David Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA; Associate Professor, University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine, Department of Medical Bioethics and Health Policy, Philadelphia, PA; and Immunization Action Coalition, St. Paul, MN

Andy S.L. Tan PhD, MPH, MBA, MBBS, Senior Fellow, Leonard David Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA and Associate Professor, University of Pennsylvania, Annenberg School for Communication, Philadelphia, PA

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest or financial relationships.

ORCID Angela K. Shen: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3761-0016

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security Serving the greater good: public health & community pharmacy partnerships. https://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/our-work/pubs_archive/pubs-pdfs/2017/public-health-and-community-pharmacy-partnerships-report.pdf Available at:

- 2.Reinhart R.J. Nurses continue to rate highest in honesty, ethics. https://news.gallup.com/poll/274673/nurses-continue-rate-highest-honesty-ethics.aspx Available at:

- 3.Brenan M. Nurses again outpace other professions for honesty, ethics. https://news.gallup.com/poll/245597/nurses-again-outpace-professions-honesty-%20ethics.aspx Available at:

- 4.Provider status for pharmacists: it’s about. Pharmacy Times; October 8, 2020. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/provider-status-for-pharmacists-its-about-time Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 5.AP NORC at the University of Chicago Most Americans Agree that Nurses and Aides are Underpaid, While Few Support Using Federal Dollars to Increase Pay for Doctors. https://apnorc.org/projects/most-americans-agree-that-nurses-and-aides-are-underpaid-while-few-support-using-federal-dollars-to-increase-pay-for-doctors/ Available at:

- 6.Institute of Medicine (US) National Academies Press (US); Washington, DC: 2010. Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events. The 2009 H1N1 Influenza Vaccination Campaign: Summary of a Workshop Series. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qato D.M., Zenk S., Wilder J., Harrington R., Gaskin D., Alexander G.C. The availability of pharmacies in the United States: 2007–2015. PLoS One. 2017;12(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assessing the State of Vaccine Confidence in the United States: recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee: approved by the National Vaccine Advisory Committee on June 9, 2015 [corrected] [published correction appears in. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(1):218] Public Health Rep. 2015;130(6):573–595. doi: 10.1177/003335491513000606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCroskey J.C., Teven J.J. Goodwill: A reexamination of the construct and its measurement. Commun Monogr. 1999;66(1):90–103. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pornpitakpan C. The persuasiveness of source credibility: A critical review of five decades’ evidence. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2004;34(2):243–281. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gehrau V., Fujarski S., Lorenz H., Schieb C., Blöbaum B. The impact of health information exposure and source credibility on COVID-19 vaccination intention in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4678. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubé E., Laberge C., Guay M., Bramadat P., Roy R., Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763–1773. doi: 10.4161/hv.24657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization How to respond to vocal vaccine deniers in public. https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2016/october/8_Best-practice-guidance-respond-vocal-vaccine-deniers-public.pdf Available at:

- 14.FDA COVID-19 vaccines. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines Available at:

- 15.CDC COVID-19 vaccines for moderately to severely immunocompromised people. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/immuno.html Available at:

- 16.MSN Conflicting school mask guidance sparks confusion. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/conflicting-school-mask-guidance-sparks-confusion/ar-AAMyc5X Available at:

- 17.Dal T. How to end the confusion of COVID-19 vaccine appointment scheduling Chicago Sun-Times. https://chicago.suntimes.com/2021/3/1/22307935/covid-19-vaccine-appointment-scheduling-preregistration-tingling-dal-the-conversation-op-ed Available at:

- 18.ASHP. Pharmacists promote COVID-19 vaccine. https://www.ashp.org/News/2021/05/21/Pharmacists-Promote-COVID-19-Vaccine-Acceptance-in-Rural-Locales?loginreturnUrl=SSOCheckOnly Available at:

- 19.ASHP. ASHP broadens vaccine confidence outreach. https://connect.ashp.org/blogs/paul-abramowitz/2021/05/14/ashp-broadens-vaccine-confidence-outreach?ssopc=1 Available at:

- 20.Ginder-Vogel K. School of Pharmacy volunteers help vaccinate underserved communities in vaccine equity effort. https://pharmacy.wisc.edu/school-of-pharmacy-volunteers-help-vaccinate-underserved-communities-in-vaccine-equity-effort/ Available at:

- 21.KGO Radio. Walgreens offers $25 with COVID-19 vaccination. https://www.kgoradio.com/2021/06/22/walgreens-offers-25-with-covid-19-vaccination/ Available at:

- 22.Shen A.K. Finding a way to address a wicked problem: vaccines, vaccination, and a shared understanding. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(5):1030–1033. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1695458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Commins J. Pharmacies see continued growth as primary care hubs. https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/strategy/pharmacies-see-continued-growth-primary-care-hubs Available at:

- 24.JD Power Recent retail pharmacy health and wellness services offer glimpse into future of healthcare, J.D. power finds. https://www.jdpower.com/business/press-releases/2020-us-pharmacy-study Available at:

- 25.National Academies of Sciences . The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2021. Engineering, and Medicine. Strategies for Building Confidence in the COVID-19 Vaccines. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO WHO Strategic Communications Framework for effective communications. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/communication-framework.pdf Available at:

- 27.WHO Best practice guidance: how to respond to vocal vaccine deniers in public. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/vaccines-and-immunization/publications/2016/best-practice-guidance-how-to-respond-to-vocal-vaccine-deniers-in-public-2017 Available at:

- 28.AMA. AMA COVID -19 Guide. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2021-02/covid-19-vaccine-guide-english.pdf. Accessed Sept 23, 2021.

- 29.AMA. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: 10 tips for talking with patients. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-19-vaccine-hesitancy-10-tips-talking-patients. Accessed Sept 23, 2021.

- 30.Lurie N., Saville M., Hatchett R., Halton J. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1969–1973. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization Status of COVID-19 vaccines within WHO EUL/PQ evaluation process. https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/sites/default/files/documents/Status_COVID_VAX_29June2021.pdf Available at:

- 32.Leshner A.I. Trust in science is not the problem. Issues Sci Technol. 2021;37(3):16–18. [Google Scholar]