Abstract

Pseudouridine (Ψ) is the most common noncanonical ribonucleoside present on mammalian noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), including rRNAs, tRNAs, and snRNAs, where it contributes ∼7% of the total uridine level. However, Ψ constitutes only ∼0.1% of the uridines present on mRNAs and its effect on mRNA function remains unclear. Ψ residues have been shown to inhibit the detection of exogenous RNA transcripts by host innate immune factors, thus raising the possibility that viruses might have subverted the addition of Ψ residues to mRNAs by host pseudouridine synthase (PUS) enzymes as a way to inhibit antiviral responses in infected cells. Here, we describe and validate a novel antibody-based Ψ mapping technique called photo-crosslinking-assisted Ψ sequencing (PA-Ψ-seq) and use it to map Ψ residues on not only multiple cellular RNAs but also on the mRNAs and genomic RNA encoded by HIV-1. We describe 293T-derived cell lines in which human PUS enzymes previously reported to add Ψ residues to human mRNAs, specifically PUS1, PUS7, and TRUB1/PUS4, were inactivated by gene editing. Surprisingly, while this allowed us to assign several sites of Ψ addition on cellular mRNAs to each of these three PUS enzymes, Ψ sites present on HIV-1 transcripts remained unaffected. Moreover, loss of PUS1, PUS7, or TRUB1 function did not significantly reduce the level of Ψ residues detected on total human mRNA below the ∼0.1% level seen in wild-type cells, thus implying that the PUS enzyme(s) that adds the bulk of Ψ residues to human mRNAs remains to be defined.

Keywords: epitranscriptomics, pseudouridine, HIV-1, post-transcriptional gene regulation

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic mRNAs are subject to a number of covalent modifications at the single nucIeotide level, collectively referred to as epitranscriptomic modifications, that can regulate the translation, stability, splicing, and/or immunogenicity of the mRNA (Gilbert et al. 2016; Roundtree et al. 2017; Tsai and Cullen 2020). For example, methylation of the N6 position of adenosine gives rise to m6A, the most common epitranscriptomic modification of cellular mRNAs, representing ∼0.4% of all adenosines (Meyer and Jaffrey 2014; Yue et al. 2015). Interestingly, m6A is detected at even higher levels on viral mRNAs, where it has been proposed to enhance viral mRNA function resulting in increased virus replication (Courtney et al. 2019a,b; Tsai and Cullen 2020). Another common epitranscriptomic RNA modification, called pseudouridine and abbreviated as Ψ, is an isomer of uridine found on a wide range of noncoding RNA (ncRNA) classes, including tRNAs, snRNAs and rRNAs (Borchardt et al. 2020). While Ψ is the most common noncanonical base detected in eukaryotic cells, representing 7%–9% of all uridine residues in total cellular RNA, Ψ is detected at more modest levels on cellular mRNAs, where it has been reported to represent ∼0.2%–0.3% of all uridines (Hughes and Maden 1978; Li et al. 2015). However, Ψ is of considerable virological interest as Ψ has been reported to inhibit the detection of exogenous RNA molecules by host innate immune factors including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) and RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) (Karikó et al. 2005, 2008; Anderson et al. 2010; Durbin et al. 2016). Overall, the presence of Ψ on exogenous mRNA molecules has been reported to not only prevent the induction of an interferon response but also increase mRNA stability and translation. As a result, synthetic mRNAs designed for use in vivo have Ψ, or more accurately N1-methylpseudouridine, exclusively in place of uridine, as seen for example in both the Moderna mRNA-1273 and the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 RNA vaccines for COVID-19 (Nance and Meier 2021). The reduced immunogenicity of mRNAs containing Ψ suggests that viruses might have coopted cellular mechanisms that deposit Ψ on their mRNAs in order to avoid host innate immune responses and facilitate viral gene expression and replication. However, to our knowledge this question has not been previously addressed.

Ψ residues are deposited on RNAs via two distinct mechanisms. Ψ residues on rRNAs and some snRNAs, representing the majority of cellular Ψ, are deposited by small nucleolar ribonucleoproteins (snoRNPs) guided by base-pairing between a box H/ACA snoRNA and the RNA target (Borchardt et al. 2020). However, only a handful of mRNA targets for Ψ addition via snoRNPs have been proposed and none have been confirmed by follow-up studies (Schwartz et al. 2014; Khoddami et al. 2019). The second mechanism for addition of Ψ to RNA transcripts depends on so-called stand-alone pseudouridine synthase (PUS) enzymes, of which 12 are known to exist in human cells (Rintala-Dempsey and Kothe 2017; Borchardt et al. 2020). Most PUS enzymes are localized either to mitochondria or nuclei and, in the latter case, are thought to modify RNAs cotranscriptionally (Martinez et al. 2020). Of the various PUS enzymes, PUS1 and PUS7 have been reported to be the predominant PUS enzymes for addition of Ψ to specific locations on mRNAs in yeast (Carlile et al. 2014; Schwartz et al. 2014) while in humans, Ψ has been reported to be added to mRNAs by not only PUS1 and PUS7 but also by TRUB1 (Li et al. 2015; Safra et al. 2017; Borchardt et al. 2020). However, at this point, few Ψ residues have been mapped on mRNAs expressed in human cells and for the majority of these, the responsible PUS enzyme remains undefined.

Here, we report the use of a novel antibody based Ψ mapping technology, termed photo-crosslinking-assisted Ψ sequencing (PA-Ψ-seq), to map Ψ residues deposited on transcripts encoded by HIV-1 as well as on cellular mRNAs in HIV-1 infected cells. We report that HIV-1 transcripts are indeed modified by the addition of Ψ at specific locations and describe efforts to define the origin of these Ψ residues using human cell lines in which PUS1, PUS7, or TRUB1 had been knocked out by gene editing using CRISPR/Cas. Unexpectedly, we observed that none of the Ψ residues detected on HIV-1 transcripts were lost when any of these three human PUS enzymes were deleted and moreover loss of these enzymes did not significantly reduce the level of detection of Ψ residues on total human mRNA below the ∼0.1% level seen in wild-type cells.

RESULTS

Previously, Ψ residues on cellular mRNAs have primarily been mapped using a chemical approach in which Ψ residues are selectively modified using N-cyclohexyl-N′(2-morpholinoethyl)-carbodiimide metho-p-toluenesulphonate (CMC), which induces a strong stop during reverse transcription (Carlile et al. 2015; Li et al. 2015; Safra et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2019). While this technique has the power to potentially not only map Ψ residues with single nucleotide precision but also quantify the level of Ψ at any given site, it requires large amounts of input RNA and, even then, has the tendency to give rise to a significant level of both false positives and false negatives, as recently discussed (Wiener and Schwartz 2021). We therefore decided to develop a simpler, alternative technique based on antibody recognition of Ψ residues that, while not as precise as CMC-based techniques, nevertheless would allow the mapping of Ψ residues with high, ∼30 nt precision using a much lower level of input mRNA.

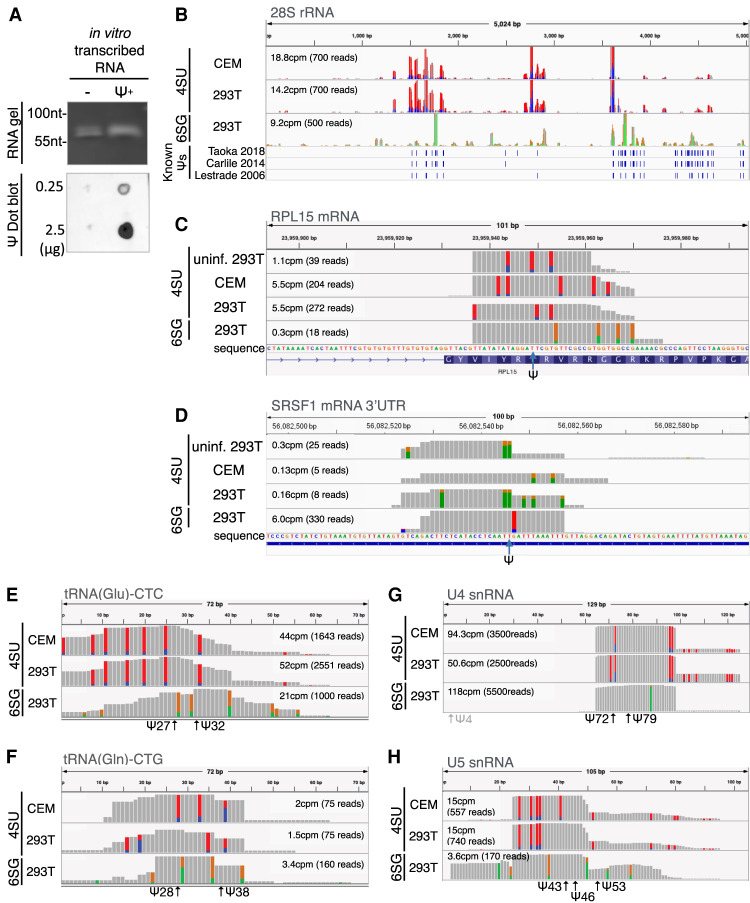

We and others have described the use of photo-assisted crosslinking of specific residues on mRNAs to a cognate antibody, followed by deep sequencing (PA-mod-seq), to precisely map the locations of m6A, m5C, and ac4C residues on viral and cellular RNAs (Chen et al. 2015; Kennedy et al. 2016; Courtney et al. 2019b; Tsai et al. 2020; Cullen and Tsai 2021) and we therefore asked whether a commercial Ψ-specific antibody could be used to map Ψ residues. We first tested the pseudouridine antibody selectivity by dot blot analysis using RNA oligonucleotides transcribed in vitro in the presence of either UTP or pseudo-UTP. As shown in Figure 1A, the anti-pseudouridine antibody specifically recognized only the Ψ-containing RNA oligonucleotide. Next, we investigated the accuracy of this novel technique, termed PA-Ψ-seq, by using it to detect known Ψ residues on cellular ncRNAs and mRNAs. Human CEM T cells or 293T cells were pulsed overnight with a photoactivatable ribonucleoside, either 4-thiouridine (4SU) or 6-thioguanosine (6SG), and total RNA harvested (Hafner et al. 2010). Total RNA was then subjected to a single round of poly(A)+ RNA isolation using oligo(dT) beads and the partially purified mRNA then mixed with the Ψ-specific antibody and crosslinked using UV light. RNA–protein complexes were then isolated and incubated with RNase T1. Protected RNA fragments were recovered by proteinase K treatment, ligated to adapters, reverse transcribed and subjected to deep sequencing. A summary of the sequencing depth of each of the 19 cDNA libraries used for this research is shown in Supplemental Table 1. A valuable aspect of this technique is that crosslinked 4SU and 6SG both induce the specific misincorporation of residues during reverse transcription, G in the case of 4SU and T in the case of 6SG, thus allowing non-cross-linked reads to be selectively removed during bioinformatic analysis (Hafner et al. 2010). We initially used the PA-Ψ-seq technique to map known Ψ residues on cellular 28S rRNA (Fig. 1B), on the cellular mRNAs encoding RPL15 (Fig. 1C) or SRSF1 (Fig. 1D) as well as on tRNAs (represented by tRNA-Glu [CTC] in Fig. 1E and tRNA-Gln [CTG] in Fig. 1F) and snRNAs (U4 in Fig. 1G and U5 in Fig. 1H). Interestingly, this technology worked equally well using either 4SU or 6SG as the photoactivatable ribonucleoside, a result which is consistent with the finding that 4SU retains the ability to undergo isomerization by PUS enzymes (Zhou et al. 2010). In order to validate the PA-Ψ-seq approach, we calculated the sensitivity, the specificity and the false positive rate (FPR) by mapping known pseudouridines in human rRNA (Lestrade and Weber 2006; Carlile et al. 2014; Taoka et al. 2018). We identified, 78, 87, and 72 of the previously reported 105 Ψ sites in human rRNA from three data sets (CEM 4SU [74.2%], 293T 4SU [82.9%], and 293T 6SG [68.6%]) (Supplemental Table 2), with an average specificity of 98%, and a false positive rate of 2.1%–2.6% (Supplemental Table 3). The sensitivity of the PA-Ψ-seq technique is therefore at least as good as the CMC-based mapping technique, which was previously reported to detect only 52 of the 105 Ψ sites reported on human rRNA, a sensitivity of <50% (Carlile et al. 2014). Moreover, a list of 73 previously reported Ψ sites on human cellular mRNAs that were also present in our data sets is shown in Supplemental Table 4; of note, a single Ψ-modification is detected as an ∼30 nt peak (Supplemental Fig. 1A–D), while several Ψ modifications located close to each other results in multiple overlapping peaks that seem as one peak that is significantly wider than 30 nt (Supplemental Fig. 1E,F). Altogether, these results show that the PA-Ψ-seq technique efficiently identifies pseudouridine modifications present on cellular RNAs.

FIGURE 1.

Validation of the novel PA-Ψ-seq mapping technique. (A) Validation of the Ψ antibody. A dot blot assay was performed using RNA in vitro transcribed with either UTP or pseudo-UTP (upper panel). RNA integrity was confirmed by gel electrophoresis (lower panel). (B) Comparison of PA-Ψ-seq-mapped rRNA Ψ sites with previously reported Ψ residues on human 28S rRNA in CEM T cells and 293T cells pulsed with 4SU or 6SG. The T > C conversions derived from 4SU crosslinking are shown as red/blue bars. On transcripts that are encoded in the reverse orientation to the reference genome, T > C conversions are shown as the reverse complement: A > G, as a green/orange bar. Similarly, 6SG crosslinking results in G > A conversions shown as orange/green bars, with C > T conversions shown as blue/red bars in the reverse orientation. Blue bars below the figure indicate the location of Ψ residues reported previously, as labeled. (C) Mapping of Ψ residues on human RPL15 mRNA in CEM T cells and 293T cells pulsed with 4SU or 6SG. The previously reported single Ψ residue is indicated by an arrow. (D) Similar to C, detection of a Ψ residue previously identified in SRSF1 mRNA. (E) Detection of previously reported Ψ residues in tRNA-Glu-CTC. (F) Similar to E, previously reported Ψ on tRNA-Gln-CTG. (G) Mapping the location of the two Ψ residues previously identified in U4 snRNA. The Ψ residue at position 4 is too close to the 5′ end of the U4 snRNA to be captured by the PA-Ψ-seq technique. (H) Similar to G, but mapping the location of the three Ψ residues previously identified in U5 snRNA.

Previously, Ψ residues on cellular mRNAs have been mapped predominantly to the coding sequence (CDS) as well as to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) using the above-referenced CMC mapping technique (Carlile et al. 2014; Li et al. 2015). In our hands, the majority of Ψ residues actually mapped to the 3′UTR, including proximal to the translation termination codon (Supplemental Fig. 2). While Ψ residues would not therefore be expected to have a major effect on codon usage, they could potentially affect the efficiency of translation termination, as has been previously suggested (Karijolich and Yu 2011).

Mapping Ψ residues on HIV-1 transcripts

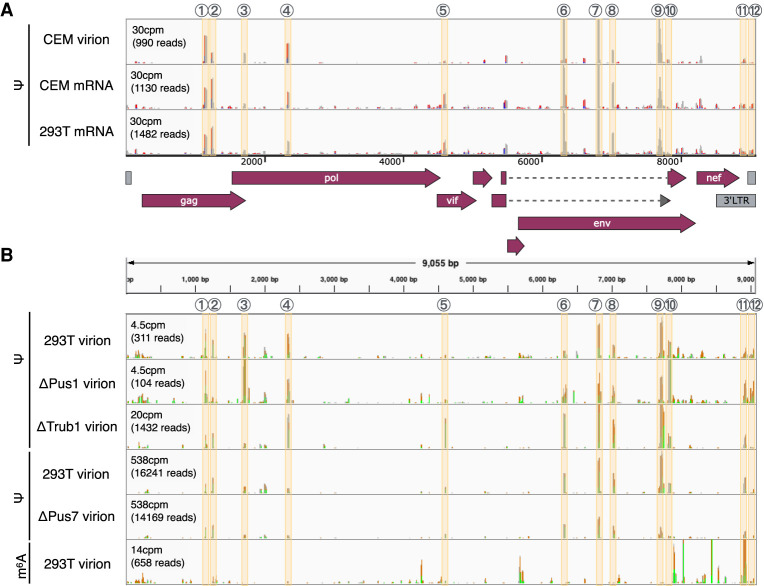

We next asked if we could detect Ψ residues on the genomic RNA or mRNAs encoded by HIV-1. As shown in Figure 2A, we were able to map at least 12 Ψ residues on viral transcripts in essentially every viral open reading frame (ORF) as well as in the 3′UTR. These Ψ residues were detected at the same locations in both virion and intracellular viral transcripts and on HIV-1 RNAs transcribed in CEM T cells and in 293T cells, thus implying that many sites of Ψ addition are not tissue specific (Fig. 2A). Of note, none of the mapped Ψ residues coincided with known important viral RNA structures such as the apical region of TAR, the RRE, or the Gag-Pol frameshift stem–loop.

FIGURE 2.

Using PA-Ψ-seq to map Ψ residues located on HIV-1 transcripts. (A) HIV-1-infected CEM T cells or 293T cells were pulsed with 4SU and virion RNA produced by CEM cells, or poly(A)+ RNA isolated from CEM or 293T cells, analyzed for the presence of Ψ using PA-Ψ-seq. (B) Similar to panel A, except that these data were obtained using total HIV-1 virion RNA isolated from virions released by 6SG-pulsed wild-type or PUS-KO 293T cells, as indicated. All these data used the PA-Ψ-seq technique except for the last lane, which used an m6A-specific antibody to perform the very similar PA-m6A-seq technique as a specificity control. Highly reproducible Ψ peaks are numbered and indicated by beige lines and are shown relative to a schematic of the ORFs present on the HIV-1 genome.

Derivation of 293T cell clones lacking individual PUS enzymes

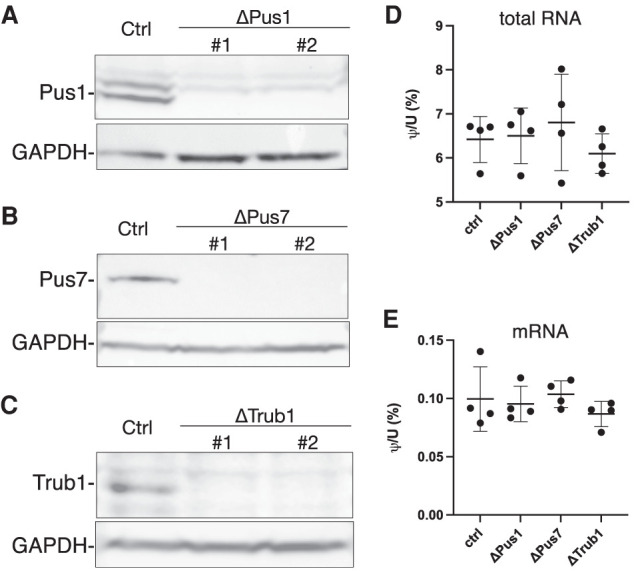

The key question is of course whether Ψ is able to regulate retroviral gene expression and replication, as we hypothesize. However, because most mapped Ψ residues on HIV-1 transcripts are located in ORFs, only a subset could in principle be mutated without affecting the underlying amino acid sequence and, given the complex alternative splicing pattern that is characteristic of HIV-1, even apparently silent mutations might disrupt one of the many viral splicing enhancer or suppressor sequences and thereby inhibit viral gene expression by a Ψ-independent mechanism. We therefore decided to focus instead on identifying the cellular PUS enzyme(s) responsible for the modification of HIV-1 transcripts using a gene editing approach, as our analysis did not reveal any significant homology of the region flanking the mapped Ψ residues to known H/ACA snoRNAs (not shown). Previous work from others has identified PUS1, PUS7, and TRUB1 (known as PUS4 in yeast) as the main PUS enzymes responsible for adding Ψ residues to mammalian mRNAs (Li et al. 2015; Safra et al. 2017; Borchardt et al. 2020) and we therefore individually knocked out each of these enzymes by gene editing using CRISPR/Cas. The resultant polyclonal cell lines were then subjected to single cell cloning and two clonal cell lines in which PUS1, PUS7, or TRUB1 was knocked out identified by western blot analysis (Fig. 3A–C) combined with Sanger sequencing of the PCR amplified genomic DNA target site (Supplemental Fig. 3). In none of the six clonal cell lines could the parental genomic sequence be recovered by PCR, thus confirming the absence of a functional PUS enzyme. Targeted gene editing resulted in the clonal cell line ΔPUS1-1, bearing a 22 nt deletion in exon 2 as well as a 336 nt deletion that removed all of exon 1, including the start codon, as well as ΔPUS1-2, bearing 5 and 64 nt deletions in exon 2. Similarly, the cell line ΔPUS7-1 had a 4 nt and an 8 nt deletion in exon 10 while ΔPUS7-2 had an 8 nt deletion. Finally, ΔTRUB1-1 had a 220 nt, a 219 nt or a 231 nt deletion in exon 1 while ΔTRUB1-2 had a 102 nt and two 220 nt deletions in exon 1, all of which removed part of the essential “motif 1” region in TRUB1 (Zucchini et al. 2003). The larger deletions seen in the ΔTRUB1 cell lines resulted from the fact that two TRUB1-specific sgRNAs were used simultaneously. Our ability to generate knockout cell lines for three different cellular PUS enzymes is perhaps surprising, as Ψ is thought to play a critical role in RNA metabolism and these PUS proteins potentially could have been essential. We did notice that all six clonal cell lines grew more slowly than the parental 293T cells and this effect was especially obvious for the two ΔPUS1 cell lines (Supplemental Fig. 4).

FIGURE 3.

Validation of cellular PUS enzyme knockout cell lines. (A) Western blot of WT and two ΔPUS1 clonal cell lines. (B) Western blot of WT and two ΔPUS7 clonal cell lines. (C) Western blot of WT and two ΔTRUB1 clonal cell lines. (D) Analysis of Ψ levels in total RNA samples derived from WT or PUS-deficient 293T clones using UPLC-MS/MS. N = 4 biological replicates with each PUS knockout cell line analyzed twice. Individual values, average and SD indicated. (E) Similar to D, except analyzing highly purified mRNA samples derived from the indicated WT or PUS-deficient 293T clones.

Quantification of Ψ levels in human mRNA

Armed with clonal cell lines lacking each of the cellular PUS enzymes PUS1, PUS7, or TRUB1, we asked whether any of these enzymes has an impact on the overall Ψ content of cellular RNA. To do this, we measured the Ψ content for both total cellular RNA and highly purified mRNA, using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). Polyadenylated mRNA was isolated by two rounds of oligo(dT) affinity purification using oligo(dT), followed by a RiboZero to eliminate any residual rRNA, since rRNA is highly enriched for snoRNA-dependent Ψ modifications. mRNA purity was assessed by bioanalyzer and measurements of both m6,6A and t6A (which are thought to be present only on rRNA and tRNA, respectively); both of these adenosine modifications were present at >100 fold the limit of detection in total RNA but undetectable in our mRNA samples (Supplemental Fig. 5). As shown in Figure 3, none of the KO cell lines showed a significant loss of overall Ψ content in either total cellular RNA (Fig. 3D) or highly purified mRNA (Fig. 3E). Of note, the amount of Ψ content detected on highly purified mRNA from our cell lines (∼0.1%) was somewhat lower than the 0.21% previously reported (Li et al. 2015), but our method differs in that it incorporates two stable-isotope-labeled spike-in nucleoside standards, and our results may therefore represent a more accurate estimation of the true Ψ content. Moreover, we note that Li et al. reported a level of 0.0017% of the rRNA-specific ribonucleoside m6,6A in their purified mRNA samples, which is at least fourfold higher that seen in our mRNA preparations (Supplemental Fig. 5) and implies a level of contamination of ∼1% rRNA in their mRNA preparation, which would be sufficient to increase the level of Ψ detected in that preparation by ∼0.07%

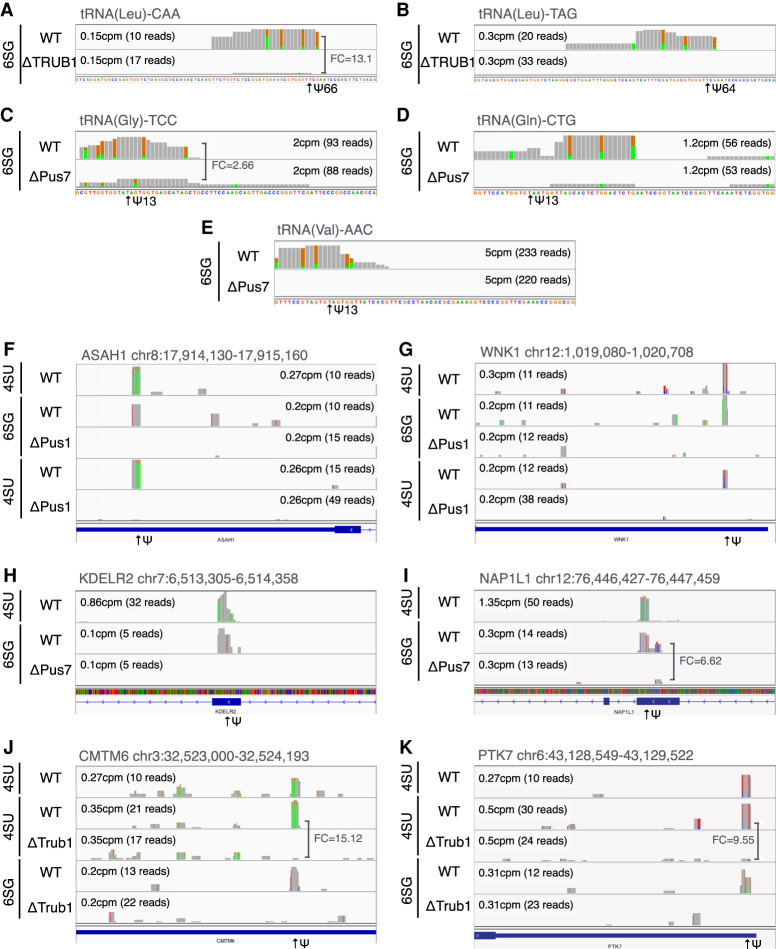

Although we did not detect any global changes to pseudouridine content in total cellular RNA or mRNA, we next asked if any of the mapped sites of Ψ addition on HIV-1 transcripts had been lost (Fig. 2B). However, we found that all 12 sites of Ψ addition on the HIV-1 RNA genome were still readily detectable in each of the KO cell lines. To further confirm the specificity of the PA-Ψ-seq technique, we performed the closely similar PA-m6A-seq technique using one of the same RNA samples (PA-m6A-seq is identical to PA-Ψ-seq except that an m6A-specific antibody is substituted for the Ψ-specific antibody) and observed the previously reported pattern of m6A sites on the HIV-1 RNA genome, with sites of m6A addition concentrated in the nef gene and the 3′ long terminal repeat (Kennedy et al. 2016). In the interest of further validating the ΔPUS KO cell clones, Ψ-sites were mapped on the residual tRNA remaining after selection for poly(A)+ RNAs. As shown in Figure 4, TRUB1 (panels A–B) (Schwartz et al. 2014) and PUS7 (panels C–E) dependent Ψ-sites (Schwartz et al. 2014; de Brouwer et al. 2018; Guzzi et al. 2018) reported on specific tRNAs were indeed lost in the KO cell lines when compared to WT cells. The presence of residual reads in some instances in PUS KO cell lines may imply a degree of functional redundancy among the PUS enzymes or may indicate the presence of an adjacent minor Ψ site that has not been previously reported.

FIGURE 4.

Representative PUS1, PUS7, and TRUB1-dependent Ψ residues on cellular RNAs. PA-Ψ-seq mapping of Ψ residues on human tRNAs known to be deposited by TRUB1 (A,B) or PUS7 (C–E). PA-Ψ-seq was used to identify de novo Ψ residues on cellular mRNAs that are dependent on PUS1 (F,G), PUS7 (H,I), or TRUB1 (J,K). The location of Ψ residues in mRNA exons (indicated by blue boxes) is indicated by arrows. Whenever the read counts in the Ψ site of the ΔPus or ΔTRUB lane was not zero, the sequencing depth-normalized fold change (FC) in site read count is shown.

We next sought to identify sites of Ψ addition to cellular mRNAs that were lost in one of the KO 293T cell lines using a very stringent bioinformatic approach. In fact, we were able to identify 12 high confidence PUS1-dependent Ψ sites, six high confidence TRUB1-dependent sites and 43 high confidence PUS7-dependent Ψ sites on a range of cellular mRNAs (Supplemental Tables 5–7). Of these, the PA-Ψ–seq data for two of the PUS1-dependent sites are shown in Figure 4F,G, for two of the PUS7-dependent sites in Figure 4H,I, and for two of the TRUB1-dependent sites in Figure 4J,K.

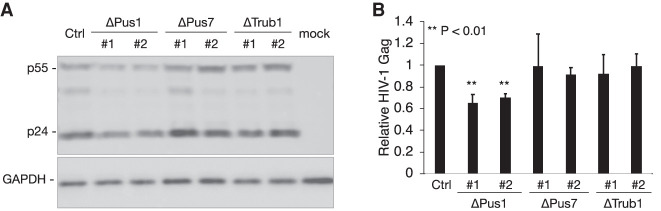

The unexpected finding that none of the mapped Ψ residues on the HIV-1 genome were lost in any of the three PUS KO cell lines meant that we could not use these cell lines to look at the effect in cis of Ψ residues on HIV-1 gene expression. Nevertheless, we reasoned that loss of one or more of these PUS enzymes might affect HIV-1 gene expression indirectly, for example by interfering with the expression of cellular RNAs. This hypothesis is tested in Figure 5A,B, which show that loss of PUS1 expression does indeed result in a modest but highly significant ∼30% decline in HIV-1 Gag protein expression, while loss of either PUS7 or TRUB1 had no detectable effect.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of loss of PUS enzymes on HIV-1 gene expression. (A) Western blot of p55 and p24 Gag produced after infection of WT or PUS mutant cell lines at 48 h post-infection (hpi) with VSV-G pseudotyped NL4-3ΔEnv virions. Cellular GAPDH was used as loading control. (B) Similar to A, except this shows the quantification of total (p55 plus p24) HIV-1 Gag production in HIV-1-infected WT or PUS mutant 293T cell lines at 48 hpi across three independent biological replicates. Data were normalized to cellular GAPDH and are given relative to the parental 293T cells, which were set at 1.0. (**) P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The original aims of the current study were to (i) develop and validate an antibody-based technique that would allow the accurate mapping of Ψ residues on mRNAs with a low input RNA requirement (Fig. 1A,B; Supplemental Tables 2, 3); (ii) map any Ψ residues present on HIV-1 transcripts; (iii) define the PUS enzyme(s) that deposit these Ψ residues on HIV-1 RNAs by genetic ablation of key human PUS enzymes; and (iv) define the phenotypic effect of loss of Ψ residues on HIV-1 RNA function and innate immune activation. We were indeed able to develop an antibody based Ψ mapping technique, called PA-Ψ-seq, and we were able to validate the accuracy of this technique by showing that PA-Ψ-seq not only allowed us to confirm the location of numerous previously reported Ψ residues on a range of ncRNAs and mRNAs (Fig. 1B–H; Supplemental Fig. 1; Supplemental Table 4) but also map Ψ residues on HIV-1 transcripts with high reproducibility in not only infected CD4+ T cells but also in infected 293T cells (Fig. 2). We chose to use previously published data sets, mapping Ψ residues on human ncRNAs and mRNAs, as the comparator for the PA-Ψ-seq technique and, given previous reports arguing that addition of Ψ to RNAs is dynamically regulated (Carlile et al. 2014; Schwartz et al. 2014), it could be argued that it would have been possible to achieve even greater congruence if we had instead performed CMC-based Ψ mapping in parallel on the same RNA samples. However, as recently noted (Wiener and Schwartz 2021), CMC-based Ψ mapping technologies are prone to both false positives and false negatives so that, for example, even in yeast, a less complex eukaryote where the large quantity of RNA required for the CMC mapping technique is easier to obtain, two studies that used CMC-based approaches to map the location of Ψ residues on mRNAs expressed in the same yeast strain grown under the same conditions had a <8% overlap (Carlile et al. 2014; Schwartz et al. 2014; Khoddami et al. 2019). Moreover, in human cells, a CMC-based Ψ mapping approach failed to detect over half of the 105 known Ψ sites on human rRNAs (Supplemental Table 2; Carlile et al. 2014). Given the relatively poor reproducibility of Ψ sites mapped on even highly expressed RNAs isolated from human cells, we therefore felt that any PA-Ψ-seq mapping data that we generated ourselves using a CMC-based approach would certainly also miss many sites of Ψ addition, while potentially also giving rise to a number of false positives. As such, we felt the addition of these data would not provide us with a more reliable comparator for the PA-Ψ-seq data than previously published and validated Ψ sites.

In addition to mapping numerous novel Ψ sites on human and viral transcripts, we were also able to derive human cell lines in which the three PUS enzymes previously reported (Li et al. 2015; Safra et al. 2017; Borchardt et al. 2020) to add Ψ residues to human mRNAs, PUS1, PUS7, and TRUB1, were individually knocked out using CRISPR/Cas (Fig. 3A–C; Supplemental Fig. 3). However, analysis of highly purified mRNA samples isolated from these knockout clones (Supplemental Fig. 5) failed to reveal a significant drop in the Ψ level on mRNA below the ∼0.1% level seen in WT cells (Fig. 3D) and we also did not detect the loss of any of the Ψ residues mapped on HIV-1 RNA (Fig. 2), though a small number of PUS1, PUS7, or TRUB1-dependent sites on cellular mRNAs could be identified (Fig. 4; Supplemental Tables 1–3). How these Ψ residues are added to HIV-1 transcripts, and whether their addition indeed positively affects HIV-1 gene expression and replication, as we hypothesize, therefore currently remains unclear. However, our data do indicate that the PUS enzymes that add the preponderance, that is more than 50%, of Ψ residues to cellular mRNAs are not PUS1, PUS7, or TRUB1, as previously proposed based largely on in vitro analysis or by analogy to yeast PUS enzymes (Carlile et al. 2014; Schwartz et al. 2014; Safra et al. 2017; Martinez et al. 2020), but rather remain to be identified. As we did not perform double or triple KO experiments, another possibility is that there is a degree of functional redundancy between different PUS enzymes, as perhaps implied by our observation that some Ψ sites assigned previously to TRUB1 or PUS7 are strongly reduced, but not fully eliminated, in the cognate KO cell lines (Fig. 4A,C). It also is possible that no single PUS enzyme is responsible for adding the majority of Ψ residues to mRNAs in human cells and that this in fact results from the combined efforts of several of the 12 known human PUS enzymes, including PUS1, PUS7, and TRUB1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

The Kidney epithelial cell line of human female origin HEK293T (CRL-11268) was cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 7% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco) at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Generation of PUS1, PUS7, and TRUB1 knockout 293T clones

PUS1, PUS7, and TRUB1 knockout (KO) cell lines were generated by transfecting 293T cells with pLentiCRISPRv2 (Addgene Cat #52961), encoding Cas9 and the following single guide RNAs (sgRNAs). Two PUS1 KO clones (ΔPUS1-1 and ΔPUS1-2) were generated using a single guide RNA (sgRNA) (5′-GAGCCGCATGCCCCCAGGAC-3′) that targets exon 2 in the PUS1 gene (Li et al. 2015); two PUS7 KO clones (ΔPUS7-1 and ΔPUS7-2) were generated using an sgRNA (5′-TTAATATTGAAACCCCGCTC-3′) obtained from the Gecko Library (Sanjana et al. 2014) that targets exon 10 in the PUS7 gene; two TRUB1 KO clones (ΔTRUB1-1 and ΔTRUB1-2) were generated using two sgRNAs (5′-CAAAAGTATGGCCGCTTCTG-3′ and 5′-TTCGCCGTGCACAAGCCCAA-3′) obtained from the Gecko Library (Sanjana et al. 2014) to delete a 240 bp region in exon 1 of the TRUB1 gene (Supplemental Fig. S1). Control cell lines were generated using a nontargeting sgRNA specific for GFP (5′-GTAGGTCAGGGTGGTCACGA-3′). The polyclonal cultures were then single cell cloned and assessed for target protein expression by western blot. To validate CRISPR mutations, the genomic DNA from all KO cell lines was extracted and the region flanking the Cas9 target site from each ΔPUS cell line PCR amplified and cloned into the EcoRI and HindIII sites of pGEM-3zf vector (Promega). The primers used to amplify the region flanking the Cas9 target sites were the following: PUS1 forward: 5′-GTCAGGGGTCAGAAGGAACAG-3′ and reverse: 5′-TCACCCTGATCACCGCAAAC-3′; PUS7 forward: 5′-ATGAGATGATGTAGGACCAGGTG-3′ and reverse: 5′-TCCTCAAGGTGTTTTTGCCAAGT-3′; TRUB1 forward: 5′-AAGGCCATGGACTACAATTC-3′ and reverse: 5′-CCTGGAGCAACTATTTAGAATT-3′. At least 10 independent clones were isolated and used for Sanger sequencing.

HIV-1 infections

Wild-type HIV-1 isolate NL4-3 was generated by transfection of 293T cells with pNL4-3 (NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Cat#114) using polyethylenimine (PEI). The media were replaced the next day, supernatant media collected at 72 h post-transfection (hpi) and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter before being used to infect cells. The pNL4-3ΔEnv plasmid expresses an NL4-3 provirus that is full length except that it bears a 943 bp deletion of the Env ORF that also introduces a frameshift mutation that inactivates the remaining ORF. This deletion removes Env amino acids (aa) 29 to 345, leaving only a vestigial 28aa product. pNL4-3ΔEnv DNA was cotransfected into 293T cells using PEI together with pMD2.G, which encodes the VSV-G glycoprotein. At 72 hpi, the virus containing supernatant medium was collected and passed through a 0.45 µM filter before use in subsequent infection experiments. A total of 500,000 293T cells (WT, ΔPUS1-1, ΔPUS1-2, ΔPUS7-1, ΔPUS7-2, ΔTRUB1-1, and ΔTRUB1-2) were resuspended in 1.5 mL of media either lacking or containing VSV-G pseudotyped pNL4-3ΔEnv virus. The infected cells were collected at 48 hpi and analyzed by western blot.

Western blots

Protein samples were collected at 48 hpi and lysed using Laemmli buffer. The samples were sonicated, denatured at 95°C for 10 min and separated on Tris-Glycine-SDS polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, blocked with 5% milk in PBS with 0.1% Tween (PBST), and then incubated with primary and secondary antibodies diluted in PBST. Western blots used the following antibodies: HIV-1 p24 (AIDS Reagent Program-6458), PUS1 (Proteintech, #11512-1-AP), PUS7 (Abcam, #ab226257), TRUB1 (Aviva Systems Biology, #ARP62931_P050), and GAPDH (Proteintech, #60004-11g) loading control.

Dot blot assay

The pGEM3Zf (+) plasmid (Promega) was linearized with Hind III and used as a template for in vitro transcription of a random 56 nt RNA using the HyperScribe T7 High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit (K1047-25, APExBIO). RNA ±pseudoUTP was transcribed in the presence of either UTP or pseudo-UTP (B7972, APExBIO). The transcribed RNA was DNase treated, acid phenol:chloroform extracted, and precipitated to remove DNA and unincorporated NTPs. The RNA was spotted onto GeneScreen Plus (NEF988001, PerkinElmer) and cross-linked to the membrane using a UV Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene). The membrane was probed with the primary anti-Pseudouridine mAb (D347-3, MBL) in TBS+0.1% Tween, washed and probed with anti-mouse IgG-Peroxidase (A9044, SIGMA) secondary antibody. The membranes were then incubated with a luminol-based enhanced chemiluminescent (ECL) substrate and signals visualized using a G:Box imaging system (Syngene). RNA integrity was visualized by Ethidium Bromide staining of the RNA after electrophoresis on a Criterion 10% TBE Urea Gel (345008, Bio-Rad).

PA-Ψ-seq

PA-Ψ-seq was performed as described previously (Chen et al. 2015; Courtney et al. 2019b; Tsai et al. 2020) with some modifications. The 293T, ΔPUS1, ΔPUS7, or ΔTRUB1 cell lines were transfected with 10 µg of a plasmid encoding CD4 (pcDNA-CD4). Next day, the media were replaced. Cells were split and infected with NL4-3 virus for 48 h and then pulsed with 100 µM of either 4SU (Carbosynth Cat #NT06186) or 6SG (Sigma Cat #858412) for a further 24 h. Total poly(A) RNA was purified using magnetic beads [Poly(A)Purist MAG Kit, Invitrogen #AM1922] following the manufacturer's instructions. The immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed using an antipseudouridine (anti-Ψ) antibody (MBL #347-3), while the m6A control was performed using an anti-m6A antibody (Synaptic Systems #202-003). An amount of 10 µg of Poly(A) RNA was incubated with 5 µg of the RNA modification specific antibody and RNasin (40 U/µL) for 2 h, crosslinked with UV 365 nm 2500 × 100 µJ/cm2 twice in a UV Stratalinker, and then treated with RNase T1 (0.1 U/µL) for 15 min at 22°C. Poly(A) RNA-antibody complexes were immunoprecipitated using Protein G magnetic beads (Thermo Dynabeads #10004D) for 1 h at 4°C in rotation. Next, RNA-antibody-protein G bead complexes were washed with IP buffer (3×) and incubated with RNase T1 (15 U/µL) for a further 15 min at 22°C. RNA end repair was performed by incubating the poly (A) RNA-antibody-protein G beads with CIP (0.5 U/µL) for 10 min at 37°C. After successive washes with phosphatase wash buffer (2×), and PNK buffer (2×), RNA was phosphorylated by adding T4-PNK (1 U/µL) in PNK buffer with DTT (5 mM) and ATP (10 mM) for 30 min at 37°C. The complexes were washed with PNK buffer (3×) and RNA was eluted from the beads by incubation with Proteinase K, 90 min at 55°C. RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen). The RNA recovered from the IP was used for cDNA library preparation using the NEB Next Small RNA Library Prep Set for Illumina (NEB, E7330S) according to the manufacturer instructions.

For virion RNA, HIV-1 virions were isolated as previously described (Eckwahl et al. 2016; Courtney et al. 2019b; Tsai et al. 2020). The supernatant from HIV-1 infected, 4SU/6SG pulsed 293T, ΔPUS1, ΔPUS7, or ΔTRUB1 cells was collected at 72 hpi, filtered through a 0.45 µm filter, and pelleted by ultracentrifugation (38,000 rpm for 90 min) through a 20% sucrose cushion. Total RNA was then extracted using TRIzol, and the IP and library preparation was performed as described above.

Sequencing libraries were sequenced using the Illumina NextSeq 500 or NovaSeq 6000 at the Duke Center for Genomic and Computational Biology (GCB) Sequencing and Genomic Technologies Shared Resource.

Bioinformatics

High-throughput sequencing data were analyzed as previously reported (Tsai et al. 2020). FastX Toolkit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/index.html) was used to remove adaptor sequences while reads shorter than 15 nt were discarded. Pass filter reads were then aligned to Human genome build hg19 using Bowtie (Langmead et al. 2009), allowing one mismatch. Unaligned reads were then aligned to HIV-1 NL4-3 with a single copy of the long terminal repeat (U5 on the 5′ end, and U3-R on the 3′ end, essentially 551–9626 nt of GenBank AF324493.2.), also allowing one mismatch. In-house Perl scripts were used only to retain aligned reads that contain the characteristic T > C or G > A mutations resulting from 4SU or 6SG incorporation. Finally, Samtools (Li et al. 2009) was used to convert alignment file formats to be suitable for visualization with IGV (Robinson et al. 2011).

PA-Ψ-seq was validated by aligning sequencing reads to human ribosomal 28S, 18S, and 5.8S rRNAs and compared to previously reported Ψ sites (Lestrade and Weber 2006; Carlile et al. 2014; Taoka et al. 2018). The sequences and the coordinates of previously reported Ψ sites in mRNA on the PIANO Database (Song et al. 2020) were compared to the Ψ sites present in our data sets. RNA reads were also aligned to tRNA and snRNA sequences (Lowe and Eddy 1997) and compared to previously reported Ψ sites (Jühling et al. 2009; Bohnsack and Sloan 2018). tRNA sequences used for alignment were from tRNAdb (Jühling et al. 2009), the rRNA sequence used was the same as used in snoRNABase (Lestrade and Weber 2006): 28S rRNA: GenBank #U13369 nts 7935–12969, 18S rRNA: X03205, 5.8S rRNA: U13369 nts 6623–6779. The snRNA sequences were downloaded individually from GenBank human genome build GRCh38.p13. Peak calling on cellular RNAs was performed using MACS2 (Zhang et al. 2008). The distribution of the Ψ sites on transcripts was analyzed using MetaplotR (Olarerin-George and Jaffrey 2017).

For de novo identification of PUS1/PUS7/TRUB1-dependent Ψ sites, sequencing reads from PA-Ψ-seq runs of cellular poly(A) RNA+ were aligned to the hg19 human transcriptome using TopHat (Trapnell et al. 2009) (transcript annotation file downloaded from the UCSC Genome Browser), allowing one mismatch. Discovery of Pus-dependent sites was done by subtracting the Ψ sites present in the KO data set from a paired WT control data set. To minimize the possibility of wrongly calling Ψ sites, where the local read depth was diminished but not gone in the Pus KO data set, as Pus-dependent, we took a conservative approach, using a higher peak calling threshold for the WT data sets than the KO data sets. To ensure a comparison of equal read depth between WT and KO data sets, the read depths of WT-KO pairs (IP'ed side by side) were normalized by downsampling the one with the higher total read depth to the same as the one with a lower read depth using the “randsample” function of MACS2. All peak calling was done using MACS2 allowing a Q value (maximum false discovery rate) of 0.0005 (macs2 callpeak –nomodel -q 0.0005 –extsize 32 –shift 0 –keep-dup 5 -g hs), while allowing a Q value of 0.05 for all KO data sets. The MACS2 called site lists were then passed through a filter while converting the xls file to a bed file (awk ‘{if($1!=“#” && $1!=“chr” && $6>=5 && $8>=5) {print $1 “\t” $2-1 “\t” $3 “\t” $10 “\t” $6 “\t.”}}’ peaks.xls > filtered_peaks.bed), only allowing sites with at least 5× pileup and 5× fold enrichment and trashing all other sites. For KO data sets, this filter criteria were loosened to allow sites with more than 1× pileup read count and 3× fold enrichment. Using the intersect function of BEDTools (Quinlan 2014), we first looked for Ψ sites consistent across an earlier independent run and the KO-paired WT run, to only consider repeatable sites. These repeatable sites were then again screened for KO-absent sites using bedtools intersect. All Ψ site overlaps defined as at least 33% overlap. Lastly, the PUS/TRUB-dependent site list was manually curated by the following criteria: PUS7-dependent sites were listed only if there were zero reads in the KO. PUS1/TRUB1-dependent sites were listed only if the read depth normalized read count KO/WT ratio of both repeats (4SU&6SG) was <0.2

RNA modification quantification by UPLC-MS/MS

Poly(A)+ mRNA was isolated from total RNA using two rounds of oligo(dT) affinity purification [NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module], followed by RiboZero treatment (Illumina). RNA quality was assessed using a Bioanalyzer 2100 with RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Agilent). An amount of 500 ng of total RNA or mRNA for each sample were then digested to single nucleosides as previously described (Courtney et al. 2019b). Briefly, RNA was incubated with nuclease P1 (Sigma, 2U) in buffer containing 25 mM NaCl and 2.5 mM ZnCl2 for 2 h at 37°C, followed by incubation with Antarctic Phosphatase (NEB, 5U) for an additional 2 h at 37°C. UPLC-MS/MS quantification of modified and unmodified nucleosides was modified from a previously published protocol (Basanta-Sanchez et al. 2016). Stable isotope-labeled internal standards 13C5-adenosine (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, CLM-3678-PK) and 15N3-cytidine (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, NLM-3797-PK) were spiked into each sample at a final concentration of 100 nM. UPLC-MS/MS was performed using a Waters Acquity UPLC and Xevo TQ-XS mass spectrometer in MRM mode, with the following details: 2.1 × 50 mm HSS T3 C18 1.7 µm column, 0.01% formic acid in water as mobile phase A with a gradient to 50/50 MeCN/Water containing 0.01% formic acid with mobile phase B. Calibration curves for modified and unmodified nucleoside standards were linear over five orders of magnitude.

DATA DEPOSITION

Deep sequencing data from the PA-Ψ-seq assays have been deposited at the NCBI GEO database under accession number GSE172136.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH grant R01-DA046111) to B.R.C. and a Duke University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR, P30-AI064518) pilot award to K.T. B.R.C. was supported by the Center for HIV RNA Studies (CRNA, NIH award U54-AI15047). The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: HIV-1 p24 Gag Monoclonal (#24-3) from Michael Malim. C.M.C. was funded in part by the Mexican National Science and Technology Council (CONACyT) fellowship: 711023/740541. We thank the Duke University School of Medicine for the use of the Proteomics and Metabolomics Shared Resource, which provided UPLC-MS/MS services.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.078940.121.

REFERENCES

- Anderson BR, Muramatsu H, Nallagatla SR, Bevilacqua PC, Sansing LH, Weissman D, Karikó K. 2010. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA enhances translation by diminishing PKR activation. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 5884–5892. 10.1093/nar/gkq347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basanta-Sanchez M, Temple S, Ansari SA, D'Amico A, Agris PF. 2016. Attomole quantification and global profile of RNA modifications: epitranscriptome of human neural stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res 44: e26. 10.1093/nar/gkv971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack MT, Sloan KE. 2018. Modifications in small nuclear RNAs and their roles in spliceosome assembly and function. Biol Chem 399: 1265–1276. 10.1515/hsz-2018-0205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchardt EK, Martinez NM, Gilbert WV. 2020. Regulation and function of RNA pseudouridylation in human cells. Annu Rev Genet 54: 309–336. 10.1146/annurev-genet-112618-043830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlile TM, Rojas-Duran MF, Zinshteyn B, Shin H, Bartoli KM, Gilbert WV. 2014. Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature 515: 143–146. 10.1038/nature13802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlile TM, Rojas-Duran MF, Gilbert WV. 2015. Pseudo-seq: genome-wide detection of pseudouridine modifications in RNA. Methods Enzymol 560: 219–245. 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Lu Z, Wang X, Fu Y, Luo GZ, Liu N, Han D, Dominissini D, Dai Q, Pan T, et al. 2015. High-resolution N6 -methyladenosine (m6A) map using photo-crosslinking-assisted m6A sequencing. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 54: 1587–1590. 10.1002/anie.201410647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney DG, Chalem A, Bogerd HP, Law BA, Kennedy EM, Holley CL, Cullen BR. 2019a. Extensive epitranscriptomic methylation of A and C residues on murine leukemia virus transcripts enhances viral gene expression. MBio 10: e01209-19. 10.1128/mBio.01209-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney DG, Tsai K, Bogerd HP, Kennedy EM, Law BA, Emery A, Swanstrom R, Holley CL, Cullen BR. 2019b. Epitranscriptomic addition of m5C to HIV-1 transcripts regulates viral gene expression. Cell Host Microbe 26: 217–227.e216. 10.1016/j.chom.2019.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen BR, Tsai K. 2021. Mapping RNA modifications using photo-crosslinking-assisted modification sequencing. Methods Mol Biol 2298: 123–134. 10.1007/978-1-0716-1374-0_8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Brouwer APM, Abou Jamra R, Körtel N, Soyris C, Polla DL, Safra M, Zisso A, Powell CA, Rebelo-Guiomar P, Dinges N, et al. 2018. Variants in PUS7 cause intellectual disability with speech delay, microcephaly, short stature, and aggressive behavior. Am J Hum Genet 103: 1045–1052. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin AF, Wang C, Marcotrigiano J, Gehrke L. 2016. RNAs containing modified nucleotides fail to trigger RIG-I conformational changes for innate immune signaling. MBio 7: e00833-16. 10.1128/mBio.00833-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckwahl MJ, Arnion H, Kharytonchyk S, Zang T, Bieniasz PD, Telesnitsky A, Wolin SL. 2016. Analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus-1 RNA packageome. RNA 22: 1228–1238. 10.1261/rna.057299.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert WV, Bell TA, Schaening C. 2016. Messenger RNA modifications: form, distribution, and function. Science 352: 1408–1412. 10.1126/science.aad8711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzi N, Cieśla M, Ngoc PCT, Lang S, Arora S, Dimitriou M, Pimková K, Sommarin MNE, Munita R, Lubas M, et al. 2018. Pseudouridylation of tRNA-derived fragments steers translational control in stem cells. Cell 173: 1204–1216 e1226. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M, Jungkamp AC, Munschauer M, et al. 2010. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell 141: 129–141. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DG, Maden BE. 1978. The pseudouridine contents of the ribosomal ribonucleic acids of three vertebrate species. Numerical correspondence between pseudouridine residues and 2′-O-methyl groups is not always conserved. Biochem J 171: 781–786. 10.1042/bj1710781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jühling F, Mörl M, Hartmann RK, Sprinzl M, Stadler PF, Pütz J. 2009. tRNAdb 2009: compilation of tRNA sequences and tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 37: D159–D162. 10.1093/nar/gkn772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karijolich J, Yu YT. 2011. Converting nonsense codons into sense codons by targeted pseudouridylation. Nature 474: 395–398. 10.1038/nature10165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karikó K, Buckstein M, Ni H, Weissman D. 2005. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity 23: 165–175. 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karikó K, Muramatsu H, Welsh FA, Ludwig J, Kato H, Akira S, Weissman D. 2008. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol Ther 16: 1833–1840. 10.1038/mt.2008.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy EM, Bogerd HP, Kornepati AV, Kang D, Ghoshal D, Marshall JB, Poling BC, Tsai K, Gokhale NS, Horner SM, et al. 2016. Posttranscriptional m6A editing of HIV-1 mRNAs enhances viral gene expression. Cell Host Microbe 19: 675–685. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoddami V, Yerra A, Mosbruger TL, Fleming AM, Burrows CJ, Cairns BR. 2019. Transcriptome-wide profiling of multiple RNA modifications simultaneously at single-base resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci 116: 6784–6789. 10.1073/pnas.1817334116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10: R25. 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lestrade L, Weber MJ. 2006. snoRNA-LBME-db, a comprehensive database of human H/ACA and C/D box snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 34: D158–D162. 10.1093/nar/gkj002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhu P, Ma S, Song J, Bai J, Sun F, Yi C. 2015. Chemical pulldown reveals dynamic pseudouridylation of the mammalian transcriptome. Nat Chem Biol 11: 592–597. 10.1038/nchembio.1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 955–964. 10.1093/nar/25.5.955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez NM, Su A, Nussbacher JK, Burns MC, Schaening C, Sathe S, Yeo GW, Gilbert WV. 2020. Pseudouridine synthases modify human pre-mRNA co-transcriptionally and affect splicing. bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.08.29.273565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. 2014. The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15: 313–326. 10.1038/nrm3785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nance KD, Meier JL. 2021. Modifications in an emergency: the role of N1-methylpseudouridine in COVID-19 vaccines. ACS Cent Sci 7: 748–756. 10.1021/acscentsci.1c00197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olarerin-George AO, Jaffrey SR. 2017. MetaPlotR: a Perl/R pipeline for plotting metagenes of nucleotide modifications and other transcriptomic sites. Bioinformatics 33: 1563–1564. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan AR. 2014. BEDTools: the Swiss-army tool for genome feature analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 47: 11 12 11–11 12 34. 10.1002/0471250953.bi1112s47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rintala-Dempsey AC, Kothe U. 2017. Eukaryotic stand-alone pseudouridine synthases—RNA modifying enzymes and emerging regulators of gene expression? RNA Biol 14: 1185–1196. 10.1080/15476286.2016.1276150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. 2011. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol 29: 24–26. 10.1038/nbt.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, He C. 2017. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell 169: 1187–1200. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safra M, Nir R, Farouq D, Vainberg Slutskin I, Schwartz S. 2017. TRUB1 is the predominant pseudouridine synthase acting on mammalian mRNA via a predictable and conserved code. Genome Res 27: 393–406. 10.1101/gr.207613.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjana NE, Shalem O, Zhang F. 2014. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat Methods 11: 783–784. 10.1038/nmeth.3047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Bernstein DA, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, Herbst RH, León-Ricardo BX, Engreitz JM, Guttman M, Satija R, Lander ES, et al. 2014. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals widespread dynamic-regulated pseudouridylation of ncRNA and mRNA. Cell 159: 148–162. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B, Tang Y, Wei Z, Liu G, Su J, Meng J, Chen K. 2020. PIANO: a web server for pseudouridine-site (Ψ) identification and functional annotation. Front Genet 11: 88. 10.3389/fgene.2020.00088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoka M, Nobe Y, Yamaki Y, Sato K, Ishikawa H, Izumikawa K, Yamauchi Y, Hirota K, Nakayama H, Takahashi N, et al. 2018. Landscape of the complete RNA chemical modifications in the human 80S ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res 46: 9289–9298. 10.1093/nar/gky811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. 2009. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-seq. Bioinformatics 25: 1105–1111. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai K, Cullen BR. 2020. Epigenetic and epitranscriptomic regulation of viral replication. Nat Rev Microbiol 18: 559–570. 10.1038/s41579-020-0382-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai K, Jaguva Vasudevan AA, Martinez Campos C, Emery A, Swanstrom R, Cullen BR. 2020. Acetylation of cytidine residues boosts HIV-1 gene expression by increasing viral RNA stability. Cell Host Microbe 28: 306–312.e6. 10.1016/j.chom.2020.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener D, Schwartz S. 2021. The epitranscriptome beyond m6A. Nat Rev Genet 22: 119–131. 10.1038/s41576-020-00295-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y, Liu J, He C. 2015. RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation. Genes Dev 29: 1343–1355. 10.1101/gad.262766.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, et al. 2008. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol 9: R137. 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Eckwahl MJ, Zhou KI, Pan T. 2019. Sensitive and quantitative probing of pseudouridine modification in mRNA and long noncoding RNA. RNA 25: 1218–1225. 10.1261/rna.072124.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Liang B, Li H. 2010. Functional and structural impact of target uridine substitutions on the H/ACA ribonucleoprotein particle pseudouridine synthase. Biochemistry 49: 6276–6281. 10.1021/bi1006699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucchini C, Strippoli P, Biolchi A, Solmi R, Lenzi L, D'Addabbo P, Carinci P, Valvassori L. 2003. The human TruB family of pseudouridine synthase genes, including the Dyskeratosis Congenita 1 gene and the novel member TRUB1. Int J Mol Med 11: 697–704. 10.3892/ijmm.11.6.697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.