ABSTRACT

Our study aimed to describe the population pharmacokinetics (PK) of piperacillin and tazobactam in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), with and without renal replacement therapy (RRT). We also aimed to use dosing simulations to identify the optimal dosing strategy for these patient groups. Serial piperacillin and tazobactam plasma concentrations were measured with data analyzed using a population PK approach that included staged testing of patient and treatment covariates. Dosing simulations were conducted to identify the optimal dosing strategy that achieved piperacillin target exposures of 50% and 100% fraction of time free drug concentration is above MIC (%fT>MIC) and toxic exposures of greater than 360 mg/liter. The tazobactam target of percentage of time free concentrations of >2 mg/liter was also assessed. Twenty-seven patients were enrolled, of which 14 patients were receiving concurrent RRT. Piperacillin and tazobactam were both adequately described by two-compartment models, with body mass index, creatinine clearance, and RRT as significant predictors of PK. There were no substantial differences between observed PK parameters and published parameters from non-ECMO patients. Based on dosing simulations, a 4.5-g every 6 hours regimen administered over 4 hours achieves high probabilities of efficacy at a piperacillin MIC of 16 mg/liter while exposing patients to a <3% probability of toxic concentrations. In patients receiving ECMO and RRT, a frequency reduction to every 12 hours dosing lowers the probability of toxic concentrations, although this remains at 7 to 9%. In ECMO patients, piperacillin and tazobactam should be dosed in line with standard recommendations for the critically ill.

KEYWORDS: dosing, ECMO, pharmacokinetics, penicillin, antibiotics, neurotoxicity, continuous renal replacement therapy

INTRODUCTION

Despite the increasing use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in the adult intensive care unit (ICU), robust research to support drug dosing in this patient group remains absent. Furthermore, the invasive nature of ECMO exposes patients to an elevated risk of developing nosocomial infections (1). As such, effective antimicrobial therapy is a significant determinant of survival for this group of patients (2). However, this goal is often challenged by extreme pathophysiological changes (3) that can alter antimicrobial pharmacokinetics (PK) and, consequently, antimicrobial exposure and dosing requirements (4). The introduction of ECMO may further derange antimicrobial PK and impact therapeutic outcomes (5). ECMO is hypothesized to predominantly affect the PK of antimicrobials by circuit sequestration leading to increased volume of distribution (V) and altered drug clearance (CL) (6). Previous preclinical and neonatal studies have demonstrated that lipophilic and highly protein-bound drugs are mostly vulnerable to these PK alterations (7–10). However, the PK of neonates is significantly different from adults, and therefore, specific adult clinical PK data are needed to guide effective antimicrobial dosing in this patient population.

Piperacillin and tazobactam is a combination of two antimicrobials consisting of an extended-spectrum beta-lactam antimicrobial (piperacillin) and a beta-lactamase inhibitor (tazobactam) that is frequently used for nosocomial infections (11). Piperacillin is relatively hydrophilic, has a plasma protein binding of 30%, and is predominantly cleared via renal elimination (11, 12). Piperacillin exhibits time-dependent bactericidal activity where the percentage of time that the free (unbound) concentration of piperacillin remains above the MIC (%fT>MIC) best describes its antimicrobial activity (13). Preclinical studies have correlated 40 to 50% fT>MIC to be associated with optimal activity (13, 14). However, recent clinical data suggest that critically ill patients may benefit from longer (e.g., 100% fT>MIC) beta-lactam exposures than those previously described (15–18). The tazobactam pharmacodynamic target has been defined as %fT greater than threshold concentration (CT). In the context of low, moderate, and high beta-lactamase expression, different tazobactam CT values have been identified as 0.25, 0.5, and 2 mg/liter, respectively (19).

In patients with normal renal function, piperacillin and tazobactam is typically dosed 4.5 g every 6 hours by intermittent infusion (11, 18, 20). Due to its potential neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity, piperacillin and tazobactam should be dosed with caution in patients with renal impairment (21). Dosing regimens should be tailored to the degree of impairment such that a dose reduction to 4.5 g every 12 hours is often used for a creatinine clearance (CrCL) of <20 ml/min (22).

There are currently little data to guide effective and safe piperacillin and tazobactam dosing in critically ill adults receiving ECMO. The Antibiotic, Sedative and Analgesic Pharmacokinetics during Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ASAP ECMO) study was designed to address this gap by describing the PK of commonly used drugs in critically ill adult patients receiving ECMO (23). The aims of this paper were to describe the population PK of piperacillin and tazobactam in critically ill adults receiving ECMO with and without RRT and to provide dosing recommendations for this group of patients.

RESULTS

Population characteristics.

Twenty-seven patients were enrolled and contributed 242 plasma samples for analysis. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics, clinical information of the patients, and relevant ECMO data. Eight patients did not have tazobactam concentrations assayed (a total of 146 tazobactam samples analyzed). The median (interquartile range [IQR]) age was 53 (40 to 58) years, and 70% (17/27) of the cohort was male. Fifty-one percent (14/27) of the patients received concurrent RRT, with the non-RRT group exhibiting a median CrCL of 99 ml/min.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics, clinical information of the studied populationa, and relevant ECMO data

| Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|

| Demographic data | |

| Male (no. [%]) | 19 (70) |

| Age (median [IQR] [yrs]) | 53 (41–59) |

| Wt (median [IQR] [kg]) | 80 (75–93) |

| Ht (median [IQR] [cm]) | 175 (172–180) |

| Body mass index (median [IQR] [kg/m2]) | 26 (24–30) |

| No. (%) of patients on RRT | 14 (52) |

| CVVHDF | 11 (79) |

| CVVHD | 3 (21) |

| No. (%) of patients by indications for ECMO | |

| Cardiogenic shock | 7 (26) |

| Cardiac arrest | 5 (19) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 4 (15) |

| Pneumonia | 4 (15) |

| Lung transplant | 2 (7) |

| Heart transplant | 2 (7) |

| Decompensated heart failure | 2 (7) |

| Post-CABG | 1 (4) |

| Illness severity score (median [IQR]) | |

| APACHE II (on admission) | 19 (15–27) |

| SOFA score (on sampling day) | 9 (6–12) |

| Native CrCL (median [IQR] [ml/min])b | 99 (65–114) |

| Albumin (median [IQR] [g/liter]) | 27 (22–30) |

| Bilirubin (median [IQR] [μmol/liter]) | 20 (13–49) |

| Total protein (median [IQR] [g/liter]) | 53 (49–59) |

| Urea (median [IQR] [mmol/liter]) | 11 (7–17) |

| No. of patients by piperacillin and tazobactam dosing regimena | |

| 4.5 g every 8 hours (no RRT) | 8 (30) |

| 4.5 g every 6 hours (no RRT) | 5 (19) |

| 4.5 g every 8 hours (on RRT) | 4 (15) |

| 4.5 g every 6 hours (on RRT) | 10 (37) |

| ECMO circuit data | |

| No. (%) of veno-venous/no. (%) of veno-arterial | 9 (33)/18 (67) |

| Type of pump (no. [%]) | |

| Jostra Rotaflow | 16 (59) |

| Cardiohelp | 9 (33) |

| Levitronix CentriMag | 1 (4) |

| Medtronic Affinity | 1 (4) |

| Type of oxygenator (no. [%]) | |

| Maquet Quadrox | 24 (89) |

| Medos hilite | 3 (11) |

| Flow rate (median [IQR] [liter/min]) | 3.3 (2.9–4.0) |

| No. of days on ECMO before sampling (median [IQR]) | 6 (3.5–7.8) |

Data are for 27 patients.

Estimated creatinine clearance only included those patients not on renal replacement therapy. RRT, renal replacement therapy; CVVHD, continuous venovenous hemodialysis; CVVHDF, continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration; CABG, coronary artery bypass surgery; APACHE II, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (II) score; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

Of the 14 patients on RRT, 11 were on continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) and 3 on continuous venovenous dialysis (CVVHD). The median (IQR) effluent and blood flow rate were 2,700 (800 to 3,000) ml/h and 200 (200 to 225) ml/min, respectively.

PK model building.

The final PK model for piperacillin (PIP) was a two-compartment model with body mass index (BMI) included as a covariate on volume of distribution of the central (Vc) and peripheral (Vp) compartment (normalized to the mean BMI, 29 kg/m2), as well as CrCL on CL (normalized to mean CrCL, 121 ml/min). An additional CL parameter was included to represent nonrenal CL (CLNR).

The final PK model for tazobactam was also a two-compartment model with BMI included as a covariate on Vc and Vp (normalized to the mean BMI, 29 kg/m2), as well as CrCL on CL (normalized to mean CrCL, 139 ml/min). The addition of CLNR did not improve the tazobactam model and was therefore excluded from the final model.

Both models produced acceptable fits. The equations below are mathematical calculations used to generate the individual BMI-scaled Vc and Vp. The total CL (CLT) was a summation of either renal (CLR) or clearance in the presence of RRT (CLRRT) and CLNR.

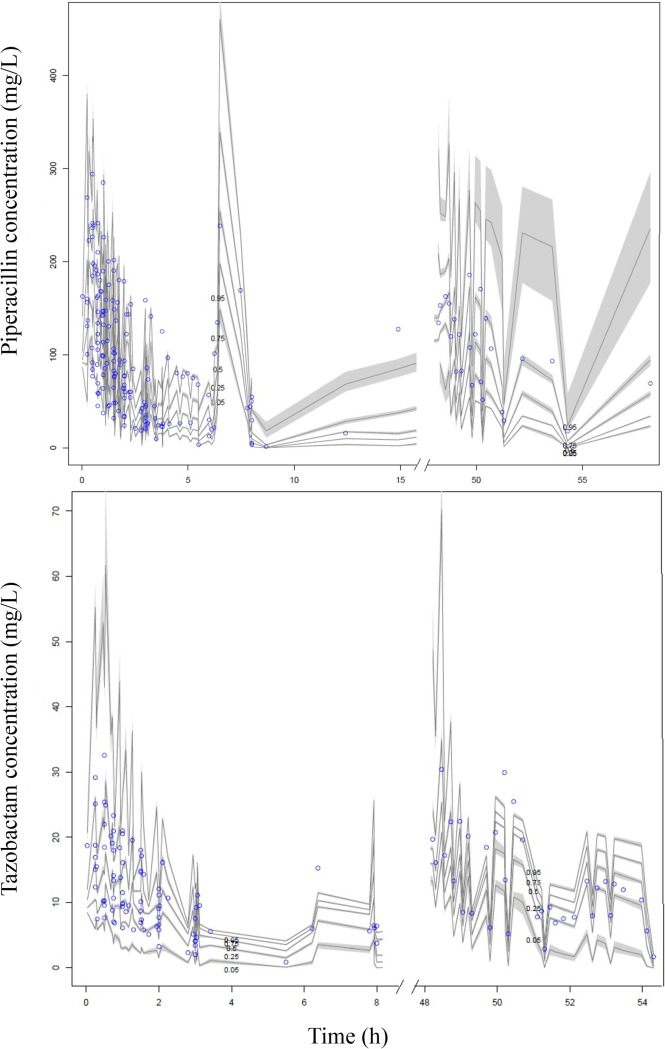

Figure 1 shows the visual predictive plots and diagnostic plots for the piperacillin model generated from 27 patients and for the tazobactam model generated from 19 patients.

FIG 1.

visual predictive check for the piperacillin (top) and tazobactam (bottom) models; n = 1,000 simulations of plasma data. Open circles represent observed data, and the lines represent the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles based on simulations of the pharmacokinetic model.

Table 2 shows the PK parameter estimates of the final PK model for both drugs.

TABLE 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameter estimates for the final piperacillin and tazobactam modelsa

| Parameter | Mean | SD | Coefficient of variation (%) | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piperacillin | ||||

| CLR (liter/h) | 9.01 | 8.24 | 91.46 | 9.36 |

| CLNR (liter/h) | 3.01 | 4.10 | 136.45 | 0.83 |

| CLRRT (liter/h) | 4.32 | 4.11 | 95.10 | 4.27 |

| Vc (liter) | 16.39 | 13.68 | 83.46 | 15.49 |

| Q (liter/h) | 23.56 | 16.08 | 68.25 | 20.33 |

| Vp (liter) | 24.13 | 17.60 | 72.94 | 16.97 |

| Tazobactam | ||||

| CLR (liter/h) | 12.59 | 3.35 | 26.59 | 12.82 |

| CLRRT (liter/h) | 3.34 | 1.77 | 52.97 | 4.65 |

| Vc (liter) | 11.62 | 8.70 | 74.86 | 8.93 |

| Q (liter/h) | 39.40 | 14.81 | 37.60 | 49.99 |

| Vp (liter) | 24.53 | 14.15 | 57.66 | 14.18 |

CLR, renal clearance; CLNR, piperacillin nonrenal clearance; CLRRT, dialytic clearance; Vc, volume of distribution of the central compartment; Q, intercompartmental clearance; Vp, volume of distribution of the peripheral compartment.

Dosing simulations.

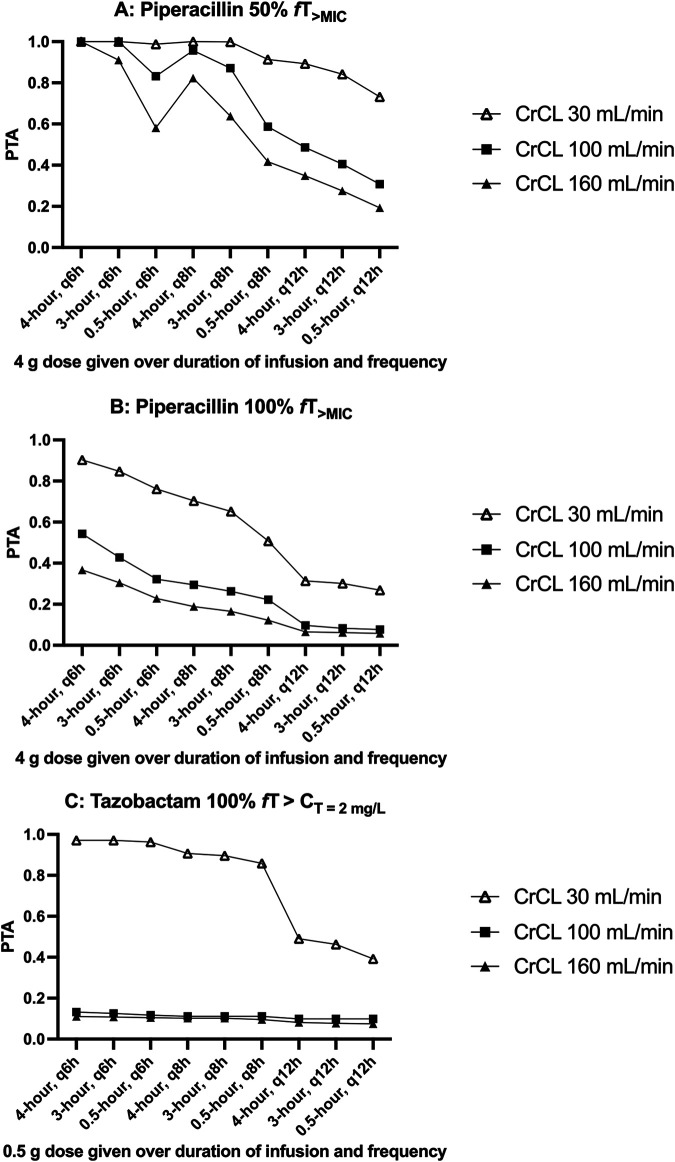

Figure 2A and B show the probabilities of target attainment (PTA) for 50% fT>MIC and 100% fT>MIC (MIC of 16 mg/liter) of various piperacillin dosing regimens for a patient with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 with various degrees of native renal function (CrCL of 30 ml/min, 100 ml/min, and 160 ml/min) at steady state (72 hours of therapy). PTA of toxicity (minimum concentration of drug in serum [Cmin] > 360 mg/liter) was not included in Fig. 2, as simulated probabilities were all below 3%. In ECMO patients not requiring RRT, a 4.5-g every 6 hours dosing regimen administered over 4 hours achieved the highest probability of efficacy (100% at 50%fT>MIC and 37 to 90% at 100%fT>MIC). Figure 2C shows the PTA for a CT of >2 mg/liter of various tazobactam regimens. Simulations suggest that PTA is low with most of the simulated scenarios.

FIG 2.

Probability of target attainment (PTA) at targets 50%fT>MIC (A) and 100%fT>MIC (B) at an MIC of 16 mg/liter for piperacillin and 100% fT>CT of 2 mg/liter for tazobactam (C), with different dosing regimens in patients with various degrees of renal function (CrCL of 30 ml/min, 100 ml/min, and 160 ml/min) at steady state with various regimens of 4.5 g piperacillin and tazobactam.

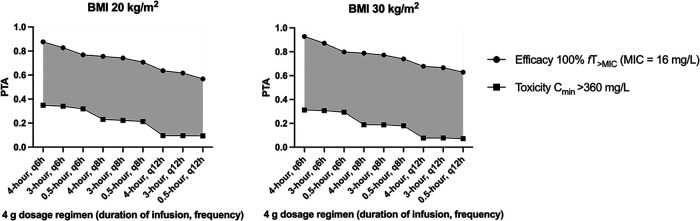

Figure 3 shows the PTAs of efficacy at 100%fT>MIC (MIC of 16 mg/liter) and toxicity (Cmin > 360 mg/liter) in a patient on RRT with no native renal function (CrCL of 0 ml/min) with various BMIs (20 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2) at steady state (72 h of therapy) with various regimens of piperacillin. In ECMO patients requiring concurrent RRT, a 4.5-g every 12 hours dosing regimen administered over 4 hours achieved the widest difference in probability of efficacy (64 to 68%) and toxicity (8 to 10%).

FIG 3.

Probability of target attainment (PTA) at 100%fT>MIC at an MIC of 16 mg/liter and toxicity at Cmin of ≥360 mg/liter for piperacillin dosing regimens in a patient with various body mass index (20 and 30 kg/m2) at steady state with various intermittent piperacillin dosing regimens in an anuric (native CrCL of 0 ml/min) patient on ECMO and RRT. Gray areas demonstrate the therapeutic window, which is the difference in the probability of attaining concentrations of efficacy and toxicity.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we observed comparable piperacillin PK parameters in ECMO patients to values from PK studies in critically ill patients not on ECMO. These results suggest that dosage adjustments to account for ECMO are not required. Based on our dosing simulations, a 4.5-g every 6 hours dosing regimen administered over a 4-hour extended infusion achieved high probabilities of efficacy with low probabilities of toxicity in ECMO patients not on RRT. Our simulations suggest that ECMO patients on concomitant RRT are at elevated risks of exceeding neurotoxic concentrations, and therefore, a reduced dosing frequency to every 12 hours is recommended.

Two-compartment PK models adequately described piperacillin and tazobactam in our study. We could not find any association between ECMO-related settings and piperacillin or tazobactam PK. In a case-control study, Donadello et al. investigated the piperacillin PK differences between ECMO and non-ECMO adult patients (24). Donadello et al. reported no significant differences in V between ECMO and non-ECMO patients. Our study observed a higher V (Vc + Vp) of 0.51 liter/kg and a higher total CL of 12.02 liters/hour (CLR + CLNR) than Donadello’s reported parameters (V of 0.38 to 0.46 liter/kg and CL of 7.92 to 8.46 liters/hour, respectively). This slight difference may be attributed to the method of PK sampling applied in the two studies. Our study used an intensive PK sampling strategy (9 versus 2 blood samples per dosing interval). Our approach is likely to better describe distribution kinetics and thus the ability to characterize a multiple-compartment PK model. The piperacillin PK parameters generated from our study were generally consistent with published estimates generated from critically adult patients not on ECMO (25–28). El-Haffaf et al. conducted a review on 10 piperacillin (with or without tazobactam) population PK studies in the critically ill, suggesting a wide estimation of piperacillin CL, ranging between 3.12 and 19.9 liters/hour, and V, ranging between 0.14 and 0.56 liter/kg (17). The estimates generated from our study were within, albeit on the higher end of, this published range. This is possibly attributable to the higher degree of critical illness in this subset of critically ill patients. It has been well reported that increasing severity of critical illness may increase V and CL secondary to systemic inflammation and augmented renal clearance (18). Our study supports the findings from Donadello et al. that ECMO was not a significant predictor for V or CL (24). We conclude that the PK changes observed were likely attributable to an increasing degree of critical illness rather than ECMO-drug interactions. Our study presented findings which support the notion that tazobactam and piperacillin PK follow the same relationship (29). There is a sparsity of tazobactam-specific PK studies. However, the parameters generated from our study were found to be higher than a population PK study with sparse sampling conducted in critically ill patients (CL, 12.59 liters/hour versus 5.27 liters/hour; V, 0.45 liter/kg versus 0.29 liter/kg) (30). This once again is likely to be due to the selection of patients with the highest degree of critical illness for ECMO therapy and differences in PK model structure. Our dosing simulations described a low PTA for tazobactam targets, suggesting higher doses of tazobactam may be required to maximize beta-lactamase inhibitor activity. Nonetheless, since tazobactam is currently only administered in combination with piperacillin, its administration method is inevitably dependent on that used for piperacillin. Overall, dosing of piperacillin and tazobactam should be guided by CrCL, BMI, and the presence of RRT as per accepted recommendations for critically ill patients not on ECMO (31). Due to the small range of BMI within our cohort (median, 26 kg/m2; IQR, 24 to 30), our dosing simulations demonstrated slight differences in PTA between a BMI of 20 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2. These slight differences did not result in a need for dosage adjustments between these two groups. Based on dosing simulations at MIC of 16 mg/liter in a patient with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 with various degrees of renal function, a dosing regimen of 4.5 g every 6 hours administered as a 4-hour extended infusion achieved the highest probability of efficacy (100% at 50%fT>MIC and 37 to 90% at 100%fT>MIC). Higher PTAs were identified with extended infusions at 4 hours compared with shorter infusion times, supporting previous studies showing advantages of extended infusions in the critically ill population (30, 32). However, higher doses or continuous infusion may still be required to improve probabilities of efficacy in patients with augmented renal clearance requiring 100%fT>MIC.

The results from our dosing simulations also suggest that the concomitant use of RRT in ECMO patients increases the probability of reaching toxic concentrations. Based on our simulations, a reduction in frequency from every 6 hours to every 12 hours dosing reduced the probability of toxicity from 31 to 35% to 8 to 10%. Therapeutic-drug monitoring (TDM)and close neurological monitoring are therefore recommended for maintenance therapy in ECMO patients receiving RRT.

Several limitations should be noted for this study. First, total piperacillin concentrations were used for PK modeling and dosing simulations. Protein binding characteristics were mathematically corrected based on previous studies suggesting consistent piperacillin protein binding kinetics in critically ill adult patients (33). Second, plasma concentrations were used as a surrogate for infection site concentrations. Due to the difficulty in measuring infection site drug concentrations, a higher PK target of 100% fT>MIC was chosen to mitigate the risks of lower drug exposures at infection site. Third, the neurotoxic threshold of Cmin of >360 mg/liter was derived from a study reporting an associated 50% risk of developing a neurotoxicity event (21). Therefore, clinicians should note that neurotoxicity may be possible below this threshold; neurological monitoring and/or TDM should therefore be used if available. Fourth, dosing simulations were only conducted for dosing regimens contributing to the PK model. Finally, our study was not powered to provide a clear description of the RRT-related changes to PK. The binary nature (RRT or no RRT) of our PK equations does not describe the intricacies of RRT variables on PK, and thus, future studies may wish to investigate specific ECMO-RRT relationships with a greater sample size.

In conclusion, this study suggests that the PK of piperacillin and tazobactam is not significantly affected by the introduction of ECMO. Dosing of piperacillin and tazobactam should be guided by CrCL, BMI, and the presence of RRT as per dosing standard recommendations for critically ill patients not on ECMO. Where possible, maintenance therapy in these patients should be guided by TDM and supported by close neurological monitoring.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting.

The ASAP ECMO study was a prospective, open-labeled, multicenter PK study that was conducted at five ICUs across Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and Switzerland from November 2012 to November 2019. A detailed study protocol and general noncompartmental results have been published elsewhere and are only discussed briefly here (23). Ethical approval was provided by the lead site (The Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, Australia; HREC/11/QPCH/121) with individual institutional approval obtained according to local protocols. Written informed consent was acquired from the participant’s next of kin.

Study population.

ICU patients aged between 18 and 90 years old who were receiving piperacillin and tazobactam while undergoing ECMO for respiratory and/or cardiac dysfunction were eligible for inclusion. Patients who had a known allergy to the study drug, were pregnant, had bilirubin >150 μmol/liter, received ongoing massive blood transfusion (>50% blood volume) in the preceding 8 hours, or received therapeutic plasma exchange in the preceding 24 hours were excluded.

Piperacillin and tazobactam dosing and administration.

Piperacillin and tazobactam was reconstituted and administered intravenously as intermittent infusions according to local hospital protocol.

Study procedures/protocol.

PK sampling was performed on one or two dosing occasions after the patient was stabilized on ECMO. Blood samples were drawn from an existing arterial line and were collected into 2-ml lithium-heparinized tubes at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 180, 360, and 480 min postcommencement of infusion.

Blood samples were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min to separate plasma. Plasma samples were frozen at the study site at −80°C. All frozen plasma samples were then couriered to and assayed at the central bioanalysis laboratory at the University of Queensland Centre of Clinical Research (UQCCR), Brisbane, Australia.

Clinical and demographic data were collected and deidentified by trained research staff. Each study site maintained an electronic database for their participants, which was subsequently consolidated into a single database.

Piperacillin and tazobactam assay.

Piperacillin and tazobactam concentrations were measured in plasma by a validated ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectroscopy (UHPLC-MS/MS) method on a Shimadzu Nexera 2 UHPLC system coupled to a Shimadzu 8030+ triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) (34). Clinical samples were assayed in batches alongside plasma calibrators and quality controls and were subject to batch acceptance criteria (39). Piperacillin and tazobactam detection was monitored at 580 to 143 nm and 299 to 138 nm, respectively. Linearity was validated over the concentration range of 0.5 to 500 for piperacillin and 0.625 to 62.5 mg/liter for tazobactam. Precision and accuracy were within 5.8% and 10% for piperacillin and within 7.0% and 7.6% for tazobactam. The lowest limits of quantification were 0.5 and 0.625 mg/liter for piperacillin and tazobactam, respectively.

Population pharmacokinetic analysis.

One-, two- and three-compartment PK models were tested using the nonparametric adaptive grid algorithm within Pmetrics package for R (Los Angeles, CA, USA) (35). Both lambda (additive) and gamma (multiplicative) error models were tested for inclusion. Biologically plausible variables tested were actual body weight, BMI, age, serum creatinine, CrCL, ECMO mode and flow rate, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (II) (APACHE II), and sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores. These variables were added onto Vc, Vp, and CL in a forward stepwise manner. In non-RRT patients, estimated CrCL (eCrCL) was calculated via the Cockcroft-Gault equation (36) found below:

If the inclusion of a variable resulted in an increase in the coefficient of determination of the linear regression (R2) and in a reduction of the bias of the goodness-of-fit plots as well as a statistically significant reduction in the log likelihood (P < 0.05), the covariate was supported for inclusion.

(i) Population pharmacokinetic model diagnostics.

The R2 and the bias of the observed versus predicted plots as well as the log likelihood of each run were considered for the goodness-of-fit evaluation. Predictive performance evaluation was based on mean predicted error (bias) and the mean bias-adjusted prediction error (imprecision) of the population and individual prediction models (37). The visual predictive check plot and the normalized prediction distribution errors were used to test the suitability of the final covariate models.

(ii) Dosing simulations.

Different piperacillin and tazobactam dosing regimens in patients with various BMIs (20 and 30 kg/m2) and native CrCL (0 ml/min with RRT, 30 ml/min, 100 ml/min, and 160 ml/min) were evaluated using Monte Carlo dosing simulations (n = 1,000) in Pmetrics. Dosing regimens evaluated were 4.5 g administered every 6 hours to every 12 hours as a 0.5- to 4-hour infusion. Extended infusions over 3 and 4 hours were included to assess potential advantages of target attainment over traditional intermittent bolus dosing regimens (32). Total concentrations were corrected by 30% to account for protein binding (12). A piperacillin Cmin of 16 mg/liter was chosen as the efficacy target, as it represents the European Committee of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) MIC breakpoint for Pseudomonas aeruginosa (38). A Cmin greater than 360 mg/liter was chosen as the piperacillin toxicity threshold where patients have been reported to be at a 50% risk of developing a neurotoxic event (21). For tazobactam, a CT of >2 mg/liter was tested. For each dosing regimen, the probability of target attainment (PTA) after 72 h of therapy was calculated as the percentage of patients achieving a 50% and 100% time the free drug concentration remains above an MIC of 16 mg/liter and a tazobactam CT of >2 mg/liter. Tazobactam toxicity was not tested, as the threshold has not yet been well defined. The optimal dosing regimen was defined as the regimen that provided the lowest probability of achieving toxicity and highest probability of achieving efficacious exposures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Juthani BK, Macfarlan J, Wu J, Misselbeck TS. 2018. Incidence of nosocomial infections in adult patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Heart Lung 47:626–630. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garnacho-Montero J, Ortiz-Leyba C, Herrera-Melero I, Aldabo-Pallas T, Cayuela-Dominguez A, Marquez-Vacaro JA, Carbajal-Guerrero J, Garcia-Garmendia JL. 2007. Mortality and morbidity attributable to inadequate empirical antimicrobial therapy in patients admitted to the ICU with sepsis: a matched cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother 61:436–441. 10.1093/jac/dkm460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdul-Aziz MH, Lipman J, Mouton JW, Hope WW, Roberts JA. 2015. Applying pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic principles in critically ill patients: optimizing efficacy and reducing resistance development. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 36:136–153. 10.1055/s-0034-1398490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jamal JA, Economou CJ, Lipman J, Roberts JA. 2012. Improving antibiotic dosing in special situations in the ICU: burns, renal replacement therapy and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Curr Opin Crit Care 18:460–471. 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32835685ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts JA, De Waele JJ, Dimopoulos G, Koulenti D, Martin C, Montravers P, Rello J, Rhodes A, Starr T, Wallis SC, Lipman J. 2012. DALI: Defining Antibiotic Levels in Intensive care Unit patients: a multi-centre point of prevalence study to determine whether contemporary antibiotic dosing for critically ill patients is therapeutic. BMC Infect Dis 12:152. 10.1186/1471-2334-12-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shekar K, Roberts JA, Ghassabian S, Mullany DV, Wallis SC, Smith MT, Fraser JF. 2013. Altered antibiotic pharmacokinetics during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: cause for concern? J Antimicrob Chemother 68:726–727. 10.1093/jac/dks435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shekar K, Roberts JA, Barnett AG, Diab S, Wallis SC, Fung YL, Fraser JF. 2015. Can physicochemical properties of antimicrobials be used to predict their pharmacokinetics during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation? Illustrative data from ovine models. Crit Care 19:437. 10.1186/s13054-015-1151-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shekar K, Roberts JA, McDonald CI, Ghassabian S, Anstey C, Wallis SC, Mullany DV, Fung YL, Fraser JF. 2015. Protein-bound drugs are prone to sequestration in the extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuit: results from an ex vivo study. Crit Care 19:164. 10.1186/s13054-015-0891-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatt-Mehta V, Johnson CE, Schumacher RE. 1992. Gentamicin pharmacokinetics in term neonates receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pharmacotherapy 12:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen P, Collart L, Prober CG, Fischer AF, Blaschke TF. 1990. Gentamicin pharmacokinetics in neonates undergoing extracorporal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Infect Dis J 9:562–566. 10.1097/00006454-199008000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi Y, Roberts JA, Paterson DL, Lipman J. 2010. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of piperacillin-tazobactam. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 6:1017–1031. 10.1517/17425255.2010.506187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sörgel F, Kinzig M. 1993. The chemistry, pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of piperacillin/tazobactam. J Antimicrob Chemother 31:39–60. 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_A.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craig WA. 1998. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin Infect Dis 26:1–10. 10.1086/516284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lodise TP, Lomaestro BM, Drusano GL, Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. 2006. Application of antimicrobial pharmacodynamic concepts into clinical practice: focus on β-lactam antibiotics. Pharmacotherapy 26:1320–1332. 10.1592/phco.26.9.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li C, Du X, Kuti JL, Nicolau DP. 2007. Clinical pharmacodynamics of meropenem in patients with lower respiratory tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:1725–1730. 10.1128/AAC.00294-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aitken SL, Altshuler J, Guervil DJ, Hirsch EB, Ostrosky-Zeichner LL, Ericsson CD, Tam VH. 2015. Cefepime free minimum concentration to minimum inhibitory concentration (fCmin/MIC) ratio predicts clinical failure in patients with Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 45:541–544. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Haffaf I, Caissy JA, Marsot A. 2021. Piperacillin-tazobactam in intensive care units: a review of population pharmacokinetic analyses. Clin Pharmacokinet 60:855–875. 10.1007/s40262-021-01013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdul-Aziz MH, Alffenaar JC, Bassetti M, Bracht H, Dimopoulos G, Marriott D, Neely MN, Paiva JA, Pea F, Sjovall F, Timsit JF, Udy AA, Wicha SG, Zeitlinger M, De Waele JJ, Roberts JA, Infections in the ICU and Sepsis Working Group of International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (ISAC). 2020. Antimicrobial therapeutic drug monitoring in critically ill adult patients: a position paper. Intensive Care Med 46:1127–1153. 10.1007/s00134-020-06050-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crass RL, Pai MP. 2019. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of β-lactamase inhibitors. Pharmacotherapy 39:182–195. 10.1002/phar.2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, Napolitano LM, O'Grady NP, Bartlett JG, Carratala J, El Solh AA, Ewig S, Fey PD, File TM, Jr., Restrepo MI, Roberts JA, Waterer GW, Cruse P, Knight SL, Brozek JL. 2016. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis 63:e61–e111. 10.1093/cid/ciw353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imani S, Buscher H, Marriott D, Gentili S, Sandaradura I. 2017. Too much of a good thing: a retrospective study of β-lactam concentration-toxicity relationships. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:2891–2897. 10.1093/jac/dkx209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perry CM, Markham A. 1999. Piperacillin/tazobactam. Drugs 57:805–843. 10.2165/00003495-199957050-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shekar K, Roberts JA, Welch S, Buscher H, Rudham S, Burrows F, Ghassabian S, Wallis SC, Levkovich B, Pellegrino V, McGuinness S, Parke R, Gilder E, Barnett AG, Walsham J, Mullany DV, Fung YL, Smith MT, Fraser JF. 2012. ASAP ECMO: antibiotic, sedative and analgesic pharmacokinetics during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a multi-centre study to optimise drug therapy during ECMO. BMC Anesthesiol 12:29. 10.1186/1471-2253-12-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donadello K, Antonucci E, Cristallini S, Roberts JA, Beumier M, Scolletta S, Jacobs F, Rondelet B, de Backer D, Vincent JL, Taccone FS. 2015. Beta-lactam pharmacokinetics during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy: a case-control study. Int J Antimicrob Agents 45:278–282. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ulldemolins M, Martín-Loeches I, Llauradó-Serra M, Fernández J, Vaquer S, Rodríguez A, Pontes C, Calvo G, Torres A, Soy D. 2016. Piperacillin population pharmacokinetics in critically ill patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome receiving continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration: effect of type of dialysis membrane on dosing requirements. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:1651–1659. 10.1093/jac/dkv503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts JA, Kirkpatrick CM, Roberts MS, Dalley AJ, Lipman J. 2010. First-dose and steady-state population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of piperacillin by continuous or intermittent dosing in critically ill patients with sepsis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 35:156–163. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sukarnjanaset W, Jaruratanasirikul S, Wattanavijitkul T. 2019. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of piperacillin in critically ill patients during the early phase of sepsis. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 46:251–261. 10.1007/s10928-019-09633-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Udy AA, Lipman J, Jarrett P, Klein K, Wallis SC, Patel K, Kirkpatrick CM, Kruger PS, Paterson DL, Roberts MS, Roberts JA. 2015. Are standard doses of piperacillin sufficient for critically ill patients with augmented creatinine clearance? Crit Care 19:28. 10.1186/s13054-015-0750-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buck C, Bertram N, Ackermann T, Sauerbruch T, Derendorf H, Paar WD. 2005. Pharmacokinetics of piperacillin-tazobactam: intermittent dosing versus continuous infusion. Int J Antimicrob Agents 25:62–67. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalaria SN, Gopalakrishnan M, Heil EL. 2020. A population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic approach to optimize tazobactam activity in critically ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e02093-19. 10.1128/AAC.02093-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akers KS, Niece KL, Chung KK, Cannon JW, Cota JM, Murray CK. 2014. Modified augmented renal clearance score predicts rapid piperacillin and tazobactam clearance in critically ill surgery and trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 77:S163–70. 10.1097/TA.0000000000000191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdul-Aziz MH, Lipman J, Akova M, Bassetti M, De Waele JJ, Dimopoulos G, Dulhunty J, Kaukonen KM, Koulenti D, Martin C, Montravers P, Rello J, Rhodes A, Starr T, Wallis SC, Roberts JA, Group DS, DALI Study Group. 2016. Is prolonged infusion of piperacillin/tazobactam and meropenem in critically ill patients associated with improved pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic and patient outcomes? An observation from the Defining Antibiotic Levels in Intensive care Unit patients (DALI) cohort. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:196–207. 10.1093/jac/dkv288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong G, Briscoe S, Adnan S, McWhinney B, Ungerer J, Lipman J, Roberts JA. 2013. Protein binding of beta-lactam antibiotics in critically ill patients: can we successfully predict unbound concentrations? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:6165–6170. 10.1128/AAC.00951-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naicker S, Guerra Valero YC, Ordenez Meija JL, Lipman J, Roberts JA, Wallis SC, Parker SL. 2018. A UHPLC–MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of piperacillin and tazobactam in plasma (total and unbound), urine and renal replacement therapy effluent. J Pharm Biomed Anal 148:324–333. 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neely MN, van Guilder MG, Yamada WM, Schumitzky A, Jelliffe RW. 2012. Accurate detection of outliers and subpopulations with Pmetrics, a nonparametric and parametric pharmacometric modeling and simulation package for R. Ther Drug Monit 34:467–476. 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31825c4ba6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chuck SK, Raber SR, Rodvold KA, Areff D. 2000. National survey of extended-interval aminoglycoside dosing. Clin Infect Dis 30:433–439. 10.1086/313692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheiner LB, Beal SL. 1981. Some suggestions for measuring predictive performance. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 9:503–512. 10.1007/BF01060893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 2020. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. EUCAST, Växjö, Sweden. https://mic.eucast.org/search/?search%5Bmethod%5D=mic&search%5Bantibiotic%5D=-1&search%5Bspecies%5D=411&search%5Bdisk_content%5D=-1&search%5Blimit%5D=50.

- 39.U.S. FDA. 2018. Bioanalytical method validation: guidance for industry. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD. https://www.fda.gov/media/70858/download.