Abstract

The global Covid-19 crisis reveals the very nature of the mobilized and interconnected risk society. Media discourse, everyday talk, science and arts process daunting questions such as Can we live a “normal” life, again?, What exactly will happen when the Corona pandemic becomes less dangerous? Can business, public and everyday life go back to how they used to be?

These questions open up possibilities to rethink current forms of urban planning. In many ways this needs sophisticated methodologies for scenario building and modelling the possible paths for cities, collaboration, innovation, and creativity in finding appropriate solutions able to cope with pandemic situations.2 See Traditional and up to now functional divisions of labour and disciplinary boundaries between stakeholders need to be re-assessed.

From 2014 to 2016 the authors conducted the explorative research project ‘Mobilities Futures and the City’ aiming to investigate the potentials of combining the methodology of future workshops with art-based co-creation approaches in order to create storylines about the future of cities and mobilities. The methodological approach developed in the project was tested in two 5-day future workshops, in Denmark and Germany respectively. Against the backdrop of the Covid-19 situation, the article presents the methodological parts of the project since it has innovative potential with respect to urban planning and rethinking the relations of mobilities and the city. The paper documents results from the workshops and discusses them towards lessons learned for transdisciplinary approaches in urban mobility planning.

Keywords: Urban mobilities, Risk society, COVID-19, Social science based mobility research, Methodological innovation, Future workshop, Transdisciplinarity

1. Introduction

The design of sustainable and resilient cities has been on the agenda for decades and mobility and transport have always played an essential role. But too often technology has been seen as the main driver and one-best-way strategy to making mobilities more sustainable, rather than altering systems, social practices and behavioral patterns. This view is supported by existing approaches to data, models and calculations in transportation research, focusing on aggregated stabilities before exploring potentials for change (Büscher et al., 2020). However, new technologies alone will not deliver the transformations into resilient and healthy cities needed, they must be accompanied with new planning and design methodologies and approaches (Chen et al., 2015; Miciukiewicz & Vigar, 2012).

With the global Covid-19 crisis the very nature of the mobilized and interconnected risk society has been revealed. The risky nature of globally connected and hypermobile societies and economies becomes visible and tangible in everyday life in the “raging standstill” (Virilio, 1977) that people experience in lockdowns. This standstill created a common experience around the globe and “ (…) the COVID-19 outbreak and extended lock-down measures have shown a previously unimaginable image of modern cities”. (Shokouhyar et al., 2021, p. 2). What will happen on the other side of the pandemic is still an open question but it is likely that some degree of pandemic thinking and acting will shape the new normal (Cresswell, 2020). What we see now is for instance that businesses are starting saving rent by downsizing office space due to experiences with digital working and meeting. Former unavailable space (like parking spaces) are now used so that cafés and restaurants can have outdoor seating etc (Freudendal-Pedersen & Kesselring, 2021). At the same time the boom of delivery services, the rise in logistics and in some places the fear of public transport have changed mobilities visibly.

This opens up opportunities to rethink and utilise resources differently and it provides a moment to reconsider assumptions taken for granted.. But in order to gain momentum and impact, universities, organizations, companies and administrations need to move out of their disciplinary and sectoral silos and comfort zones. Intellectual resources and capacities, coming from different disciplines, cultures and worldviews, working together in creating more sustainable and resilient cities, may be used and activated innovatively.

In line with (Sheller & Urry, 2016) we argue that transdisciplinary research in mobilities can play an eminent role in grounding the contemporary global complexities of today. Transdisciplinary approaches are less occupied with conventional disciplines, instead they focus on the challenges and the knowledge needed to understand and change these issues. Its innovative potentials and understandings of mobilities as fundamental structuring elements in societies can open up new perspectives for reaching sustainability and resilience in modern societies and economies. Taking this as an ontological outset the article is based on a research project aiming at opening up new ways of thinking about the future of cities and their mobilities. We conducted the explorative research project ‘Mobilities Futures and the City’ (MFC) (Freudendal-Pedersen & Kesselring, 2016) to experimentally investigate the potentials of combining the methodology of future workshops with art-based co-creation approaches in order to create storylines about the future of cities and mobilities (Kjaerulff et al., 2017; Witzgall et al., 2013). The concept was tested in two future workshops, each five days long. One took place in Southern Denmark and one in the German southeast, in Bavaria. Against the backdrop of the Covid-19 situation the methodological parts of the project have acquired an additional topicality. The project was designed as an applied contribution to the debate of reflexive planning for the “mobile risk society” (Freudendal-Pedersen et al., 2018; Kesselring, 2008a). It intentionally challenged predominant rationalities within planning and decision-making through close interactions with artists and their ways of working and researching.

The two workshops were facilitated to give space to “powerful stories for the good mobile urban life of the future”, as we wrote to the participants beforehand. Planners, decision-makers from politics and industry, scientists, designers, musicians and visual artists were put together to imagine the future of mobility. As a consequence of the sample criteria, the configuration of participants was privileged. People needed to be able to afford the 5 days away from their actual work. Nevertheless, the methodological outset, the framing and the orchestration of the workshops was closely in line with critical utopian action research and its ontological critique of elitist planning processes (Svensson & Nielsen, 2006). This tradition uses the strength of utopian thinking for the design of desirable, realistic and human scale futures, since utopias open up for a critique of the existing through thinking in desirable futures.

Conceptual elements of the ‘argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning’ (Fischer et al., 1993) have been used to unfold planning as the narrative activity of storytelling, mostly in words. Artistic representation is strongly based on visualisations and researching and learning through creating, rather than through verbal activity. Throughout the workshops we invited the participants to use visual, auditive and haptic techniques of expressing ideas. Further we developed r separate phases in the workshop for games, plays and all sorts of creativity. As an outcome, the social situation created gave way to re-thinking mobility and the city. The artists introduced an inspiring ‘functional perplexity’ into a setting most often dominated by words and verbal eloquence as a technique to act powerfully and convincing.

Here, we discuss the potentials of combining the different methodologies in order to stimulate new articulations for highly complex problems, interdependent and heterogeneous relationships and the attempts to give access to divergent rationalities and interpretations. What we present in this paper is some of the fears, utopias and visualizations that seem even more relevant and timely today.

In order to get there, the paper is structured in the following parts:

-

1

We briefly outline the main theoretical ideas of what we call the mobile risk society and its relevance for the argumentative turn in planning.

-

2

We briefly introduce critical utopian action research and artistic representation as a way into the methodological choices made in the workshops.

-

3

We focus on the methodological setup of the workshops, their different phases and reflections on combining methodologies.

-

4

We discuss two projects resulting from the workshops to show how the methodology leads to a deeper and more complex understanding of futures and the connections between mobilities and the modern ideas of the good life.

-

5

The final conclusions elaborate on the future of participative methodologies and their role in creating storylines for possible new mobilities futures and the city in the light of Covid-19.

The reflections and quotes from the workshop participants used in the article mostly stem from two evaluation dinners, each three months after the workshops. In other cases it is marked in the text, i.e. when quotes come from interviews.

2. The mobile risk society and the argumentative turn

One signifier of “second modernity” (Beck, 1992) is living with risks threatening modern lifestyles, identities, livelihoods and whole existences. The omnipresence of risks has made reflexivity an inevitable part of late-modern lives (Beck et al., 2003; Kesselring, 2019). This entails no ontological certainty or blind belief in a positive outlook for future and progress. We cannot know how social change will turn out, and thus dystopian visions of the future become increasingly realistic. As a consequence, we plan for transitions based on the present, instead of developing positive visions of desirable futures. The ‘new mobilities paradigm’ emphasizes the understanding of movement as something more than an instrumental issue. Movement plays a constitutive role in modern lives. It has a strong influence on social, political and economic processes and the organization of societies. The city can be understood as a complex of diverse mobilities where “[…] multiple senses, imaginative travel, movements of images and information, vitality and physical movement, [are] materially reconstructing the ‘social as society’ into the ‘social as mobility’’ (Urry, 2000, p. 2).

The concept of the “mobile risk society” (Kesselring, 2008b) combines elements from the “theory of reflexive modernization” (Beck, 1992) and the ‘new mobilities paradigm’ (Sheller & Urry, 2016). It emphasizes the unintended and exponentially growing side effects of mobility and transport and the vulnerability of modern mobility systems. Quantitatively, modern societies do not necessary entail more risks than earlier ones. But, what is more salient, is the qualitative aspects of those systems due to their global and networked character and the increased perceived risks due to increased mobilities. Societies’ capacities for instant communication and real-time information have made risks a permanent component in everyday life. Choices have to be made under constant and immense time pressure (Eriksen, 2001). Mobility has become a highly reflexive and ambivalent phenomenon. Throughout the last century mobility has become the signifier for a frictionless speed as that which creates happy and wealthy cities and lives (Jensen & Freudendal-Pedersen, 2012), and positive social and economic impacts in terms of connectivity, international collaboration and the expansion of social network. What we see clearly today in concepts as smart cities, are the powerful ideas and imaginaries of a ‘zero-friction society’ (Hajer, 1999) with the promise of seamless mobility. On the other hand we also see an up to now dominance of side-effects, materializing in congestion, pollution, noise and environmental problems that cities all over the world are fighting to re-conciliate. Systems of mobilities, their speed and outreach, have been contributing to making mobile working and living part of many lives. Through the extension of mobilities, interaction with almost every place and person in the world has become potentially possible. However, the growth of individuals’ activity spaces has huge consequences of increased energy use and CO2-emissions (World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2004). These are all problems that individuals and modern institutions do not have routines and instruments to handle. In other words: there is no one-best-way of tackling mobility-induced problems - neither on the societal and institutional nor on the individual and family-based level. Even if we notice that people start questioning and avoiding the use of aircrafts and that there is a slow increase in cycling in cities around the world, global CO2 emissions from transport are still on the same level as they were at the time of the 1992 UN summit for sustainable development in Rio de Janeiro..

In line with Beck (1992) we can say, the modern project of increasing mobility – socially, culturally but mainly spatially - has been successful. The stability of the transport-related CO2 footprint is also a product of more wealth and changing travel patterns in the lower and middle classes. In many wayswe also have the mobility the modernists of the early 20th century wanted. But the problem is, all this comes along with massive negative side effects. And in parallel, in the big picture, contemporary cities and their infrastructures and architectures look the way modernists such as Le Corbusier dreamed of. Cities as Brasilia and Los Angeles are iconic urban phenomena where modernist ideas are still alive and dominating urban planning (Gehl, 2010). The private car has become the cornerstone of the modern city with its sophisticated division of labour between spaces and functions. Nevertheless, it is the unintended side effects that have driven the cities until now. Increasingly, congestion, pollution, noise, social segregation and uneven access to mobility and the degradation of urban and public spaces are on top of the urban agendas. Instead of celebrating the power of modernity, the crucial questions of urbanism has become: how can we manage risks and the unforeseen side effects of urban mobilities to make them livable places - again?

Urban theorists such as Leonie Sandercock, Patsy Healey and Marten Hajer suggest storytelling as a communicative planning practice to reconciliate the past and the future. By understanding practices of planning and policy making as storytelling, they build upon the tradition of Habermasian ‘communicative action planning’ (Healey, 1993; Sandercock, 2003). These approaches take seriously that we need new kinds of powerful stories to initiate change and to give direction to transition processes. There are myriads of practice examples that show the power of storytelling practices and the impact on urban planning and design (i.e. Chen et al., 2015; Deckha, 2003; Kesselring & Tschoerner, 2016). But first of all, problem definitions need to be modified and thereby also the social constructions of solution finding strategies for future cities. The ‘system of automobility’ (Urry, 2004) is deeply rooted in the modernist planning paradigm. To rethink ‘business as usual’, planners and urban stakeholders have to create different spaces where thinking out of the box is possible and can go in unimagined directions. These spaces need different methodologies and methods that can handle ambivalence since “uncertainties, ambiguities, unpredictabilities and unexpected consequences have become the defining features of our increasingly turbulent times” (Fischer et al., 2012, p. 4).

3. Critical utopian action research and artistic representation

This is where critical utopian action research comes into the picture. From its early beginnings, it has been challenging the elitist modern expert planning paradigm (Svensson & Nielsen, 2006). Today, action research has many strands, but the work of German social psychologist Kurt Lewin from the 1940s has been the first serious attempt to democratize research (Egmose et al., 2020; Nielsen and Nielsen 2006). The common idea within this tradition is that the researchers are co-creators of new knowledge. The production of knowledge occurs in ‘co-operation with social actors based on trust and a free agreement to participate’(Svensson & Nielsen, 2006). For these authors it is the functionality and strength of utopian thinking that has the potential for designing desirable and realistic futures and for stepping out of rigid path dependencies (Bladt & Nielsen, 2013; Tofteng & Husted, 2011). For many years, utopian thinking has been marginalized within social science. This has changed, not least through the writings of critical theorists and practitioners (Harvey, 2000; Healey, 2002; Jensen & Freudendal-Pedersen, 2012; Pinder, 2005). Methodologically, utopias empower citizens, stakeholders and academics to formulate a critique of the existing through developing clear ideas about desirable and sustainable futures.

Critical utopian action research departs from the assumption that utopian potentials in policies and the process of envisioning play key roles within transition processes. Cities worldwide are in a transition phase. The limits of contemporary urban practices in mobility, energy, consumption and so forth become visible. Innovative ways of thinking about the future of urban mobility are needed. The MFC project aimed at finding ways of envisioning ”future image(s) with transformative characteristics” (Grin et al., 2010, p. 206).

As Sandercock (2011) puts it, art can play a key role in urban planning since it can be understood as non-verbal storytelling. She underlines how the potential of collaboration between planners and artists in encouraging and facilitating storytelling has scarcely been tapped. When art is set free from being the production of the artist, it is sometimes able to transcend into a potential democratic, transformative and utopian space (Lefebvre, 1996; Pinder, 2002, 2008). Speaking in terms of action research, participatory art transforms from being traditional art to an audience and into being art from and about the participants involved (Westlander, 2006). Art in relation to the urban has primarily focused on the works designed to enhance public spaces aesthetically as a part of cultural strategies of urban space regeneration (Pinder, 2008). But it can also be the ‘arts of urban exploration’ (Pinder, 2005), where urban space is explored through artistic practices. Pinder (2005) advocates for strengthening the dialogue between urban and spatial theory as well as artistic and cultural practices. Hesuggests exploring the potentials of cross-disciplinary collaborations between planners, architects and artists for a powerful policy of space. Creativity and imagination are not a monopoly of artists. But being educated as an artist means to develop professional skills in creating imaginary spaces. Opening up and staging, shaping and sculpturing visions is part of the artistic process. The German artist Joseph Beuys describes seeing art as a process of creating a ‘social sculpture’ that links the artistic production process to social practice and society (Harlan et al., 1976). By involving artists and art in different ways, the research project aimed to establish and enable dialogue between different rationalities and perceptions of reality.

4. The “Mobilities Futures and the City” workshops

The ‘Mobilities Futures and the City’ project (MFC) contributes to the development of a reflexive methodology for urban planning and policymaking. As Mitteregger et al. (2020) put it, urban spaces are facing huge technological transformations in the near future. They see a “paradigm shift in mobility” arising through autonomous, connected and cooperative mobilities.

The MFC project aimed at testing out possibilities for creating an environment for planners, decision-makers from politics and industry, and artists where new powerful ‘stories’ about the good mobile life in cities could be developed that are not merely driven by techno-centric narratives but rather integrate the human scale in imagining the future. The participants of the workshops were chosen for working together in an open-minded way in a setting of low hierarchies with a minimum set of rules. Those few but strict rules were created to secure a democratic arena where everybody has the possibility to participate on equal terms (Freudendal-Pedersen et al., 2017). When we made this choice, it was made to take into account the experimental artistic outset of the workshops. The aim was as much to develop new methodologies as working on real-world societal problems. The duration of the workshops was five days (3+2), with a month in-between the Copenhagen and the Munich workshop. To build up trustful and productive arenas in the workshops, all participants were asked to participate the first three days, but the subsequent creative two-day retreat was optional. This was based on the knowledge that five days is a lot of time for professionals to commit to a project outside of their usual tasks. The open invitation meant that several of the participants rearranged their plans and stayed.

The workshops were conducted in secluded locations to create safe and decelerated working situations. For each workshop the groups had to drive at least 1.5 hours, in the German case the last mile had to be crossed over by ferry to reach an island. This resulted from previous experiences with busy professionals where meetings could often be squeezed in and got disrupted by short in-between meetings outside of the workshops. The locations created a ‘luxurious situation’ of peaceful surroundings and produced a sort of bubble away from daily chores. It helped participants to focus, relax and become open-minded. Quickly, cell phones were left behind in the rooms, only used during breaks.

Three months after the workshops, we invited the participants for an evaluation dinner. The discussion about the secluded place stimulated deep thinking and philosophical reflections on time and space, physical and social distance and the culture of ‘here and there’. The following formulation from a member of the local Munich transport provider stands for most of the comments:

‘(…) I think one of the reasons why the workshops actually worked out has been the setting of this environment. It was a good choice to go there. Beforehand I thought why do they have to go there!? It's so long to get there (…). I was really sceptical. But in the end, it was the setting that made it possible, since there wasn't much distraction.’

The participants of the two workshops were chosen based on the following criteria:

-

•

their impact on local urban agendas (we called them “influential movers”),

-

•

different disciplinary and professional backgrounds (local planning, politics, architecture, arts and social science),

-

•

confident in talking English and

-

•

being familiar with the local Copenhagen or Munich context.

The role of the participants is essential in these workshops. They need to be able to fill the space the method is offering and they need to be able to handle its incremental uncertainties and insecurities. But the participants also saw this as a learning opportunity, and access to new perspectives, knowledge and skills as this quote from the evaluation dinner shows:

‘People you meet normally are your friends or people in your field. Situations like the workshops never happen, this sort of exclusiveness. I am thinking back to how amazing this is and I may think this might never happen again in my life.’

A participant of the Danish workshop mentioned the fact that ‘as a designer I am used to draw but not that much to talk. But in this setting with all these different people I talked a lot.’ Following up on this, a Danish architect emphasized the meaning of language and the fact that the transdisciplinary constellation of people enforced in some ways that

‘I have learned a lot about language. At the first days, I am usually good at talking about architecture in a language that everybody understands. But when I was talking, you guys looked at me as if you didn't understand. And if we are working in such transdisciplinary environments, we need to be better aware of what language we are using. Afterwards, I had a couple of experiences where I was more sensitized for the language I was using. I tried to be more precise and careful. This was a very good experience.’

In other words: Within the collaborative, playful and inspiring atmosphere new experiences and transformative knowledge arose for the participants. This was already initiated beforehand since a week in advance a ‘book of inspiration’ was sent to the participants. The book was created to inspire reflections upon the field of mobilities. It consisted of pictures and art pieces as well as quotes from books and songs. The participants were asked to bring an object that symbolized mobilities for them. In the first phase of the workshop, the object became part of the conversations and games to show the different understandings of mobilities among participants. To activate the creative sides of the individuals we set up a ‘material lab’. It was designed as an open space where people could pick materials to work with, illustrate, tinker, discuss or present their ideas. We asked the artists in advance which materials they would like to have available.

The future workshop, as developed by Jungk and Müllert (1987), entails three phases: critique, utopia and realisation. In the MFC workshops we framed this in-between two additional phases: building common ground and the creative retreat.

4.1. First additional phase – Building common ground

The first add-on phase ‘Building common ground’ was made to create trust and confidence between a group of people that normally does not work together. Through games and discussions we started building up a free space where a collaborative clarification of language could be developed. We used different tools to achieve this:

-

1

Speed dating: everyone meets and tells why they agreed to attend the workshop and what they hoped to get out of it.

-

2

Mistakes I made and what I learned from them: participants decide themselves if they want to talk about personal and/or professional mistakes.

-

3

Objects of mobility: people explain what the mobility artefact (i.e. a small bike, a stone, a song, an art piece etc.) they brought along symbolizes to them.

-

4

The Thing from the Future: A card game developed and designed by scientist Stuart Candy and artist Jeff Watson from The Situation Lab (www.situationlab.org).

The green card describes different kinds of possible futures such as grow, collapse, discipline or transform with a time horizon attached. The blue card describes contexts where the thing from the future is placed. The pink card describes the form of the thing for the future. Lastly, the purple card describes the emotions it evokes. In the game the participants draw a card from each color and work in groups towards imagining different futures based on this.

In this phase participants articulated different and sometimes contradictory perspectives and rationalities. The playful procedure initiated a process where people clarified their attendance for themselves and others, but they also formulated their own intentions for the others and themselves. Not everybody was fully aware of their own motives and drivers. This created a lively and reflexive group dynamic, since some of them knew each other from other professional occasions and met in a new and sometimes surprising way. As a result, participants generated a common story on future issues of cities and mobilities, expressed here by one member of the German group:

“The first day brought the group very much together. It helped to build a trustful basis between us. I became quite relaxed with the others and it took away some of my fears that I had in advance.”

4.2. The future workshop methodology phases

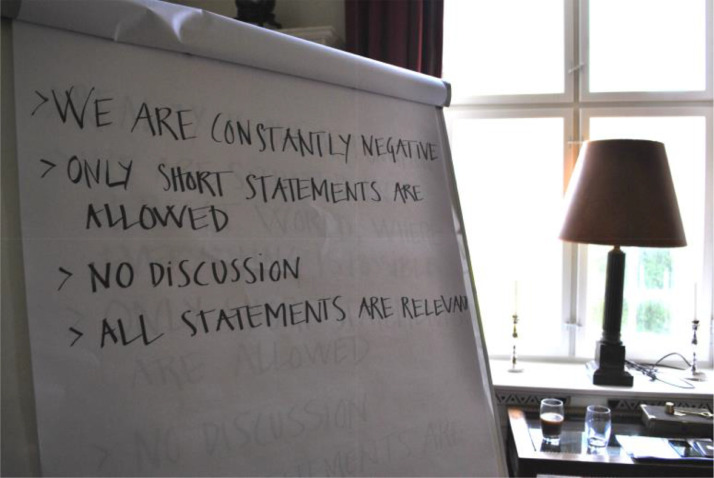

After this initial phase, we applied Jungk and Müllert (1987) main approach to future creating workshops, the ‘classical’ three phases. Those are the critique, the utopia and the realization phases. For those, specific communication rules have been formulated and put up visibly for all members of the workshop. More than 30 years ago, Jungk and Müllert (1987) developed them to create social innovation and participation - as democratic and equal as possible. This set of rules empowers a self-learning environment where opinions and worldviews can be exchanged freely. The facilitators – in this case the authors, here as researchers and co-producers of knowledge – can never interfere or judge any of the participants’ statements. They can help clarifying imprecisions and support sharper formulations. But in the end, what counts are only the participants’ words. To make a smooth transition between the different phases and to keep an open, respectful and friendly atmosphere, different interactive games were played (see below).

The critique phase was very openly structured. We invited the participants to articulate all aspects of mobilities and cities they found problematic. They individually decided on the relevance of the issues. By so doing, we followed the method strictly: every kind of frustration, anger or annoyance was welcome. This provides the opportunity to voice any negative feelings about the current situation. In line with Jungk and Müllert (1987), the validity and legitimacy was not open for discussion. If someone disagreed, a counter statement could be posed, but without discussing what is right or wrong. When the critique is off the chest, it is less likely to ‘disturb’ the following vision phase. This creates a common overview of the problems and challenges and from there, fruitful future scenarios can be developed (Freudendal-Pedersen et al., 2010; Nielsen, 2006). In order to stay within the frames of the phases, the communication rules were put visibly in the room.

The process for the critique phase is as follows:

-

•

Brainstorm, short sentences written on wallpaper (plenary)

-

•

Voting for most important critiques, each participant gets three votes (plenary)

-

•

Giving substance to the most important critiques (group work)

-

•

Presentations in plenary session.

The brainstorm is an open process where participants come up with what they already have in mind. Long periods of silence where participants reflect are welcome and purposeful. A statement has to be constructed in a way that the facilitators can write it on wallpaper. In this way, a wall full of different critiques is being constructed. It stays visible throughout the workshop. As many different critiques come up, the participants are asked to vote for three statements they find to be the most important or relevant ones. Based on the votes, groups were formed and the participants chose which critique to work with. The groups present their understanding of what this critique entails through a silent play by using the materials of our lab. Through the silent play the opportunity arises to develop and expand the understanding of a specific critical statement. This step followed the play discussed with the other participants.

The utopian phase focuses on stimulating the imaginary and creative potentials of the group. The guiding question in this phase was: “We know the critique, what should we do differently?”

There are no limitations to relevance and importance of an idea or perspective. Again, short statements were written on wallpaper and the communication rules were visible in the room:

-

•

There is no such thing as reality.

-

•

Everything is possible.

-

•

Only short statements are allowed.

-

•

No comments on or discussions of statements.

-

•

All statements are relevant.

The process follows the same steps as the critique phase:

-

•

Brainstorm, short sentences written on wall paper (plenum)

-

•

Voting for the most important utopia, each participant gets three votes (plenum)

-

•

Giving substance to the most important utopia (group work)

-

•

Presentation (plenum).

Several utopias with many votes emerged. In order to make groups with 4-6 participants, the facilitators coupled utopias and the participants renegotiated new compilations. Participants chose utopias and worked with them for two hours with free choice of presentation and access to the material lab. After the presentations, participants discussed the utopias presented and selected those to work with in the realization phase.

The realization phase focuses on creating strategies and policies by thinking through which pathways to follow for action and impact. In this phase of a future workshop, the work is centred on what can be done to make a utopia viable by creating a step-by-step plan with specific actions. The tool used here was back casting where a timeline would illustrate what had to happen when for the realization of the utopia. Through this the ideas are turn into stories and narratives that are more concrete and tangible. The main aim is to transform these utopias into several concrete steps and the visions and scenarios into something more realistic to work towards. The phase has the following structure:

-

1

Deciding which utopias to continue with (plenum)

-

2

Group work (groups)

-

3

Advocacies

-

4

Presentation (plenum)

Participants themselves decide which utopias they wish to move on with in the realisation phase. We suggested to build the groups as diverse as possible, but we also accepted sympathyand interest as important elements in group work. While working with the realisations, we presented the groups with ‘advocacies’. These are put in as disruptive elements in working with the utopias and it is up to the groups if they want to implement them. The advocacies were focused on inequality, law and economies, all of which issues often coming up when the future of mobilities and cities is discussed. The method used was showing short movies or filmed interviews with different experts. Through the confrontation with the advocacies, the participants get trained in explaining and defending their ideas and maybe also in integrating some of the aspects into their project. This phase ended with presenting the realization of the utopia through many different media, words, short films, web programs, art installations and so forth.

4.3. The second additional phase – the creative retreat

The aim of the creative retreat was to facilitate an opportunity space for the participants to move on with presenting their visions and ideas; also to detail them and to use methods from arts, science or visualization techniques to materialize and shape them. To have time to create visualizations, texts, models etc. that could be used to discuss or convince other experts from the innovative character of the ideas. As facilitators, we were available for discussions but to a high degree the participants had taken over the process from there. We did not structure the activities more than through short plenary meetings to catch up on the current status of work. In detail the process was structured in:

-

1

Deciding which realizations to work on (plenum),

-

2

Working on presentations (individual and/or in groups),

-

3

Short plenary meetings.

-

4

Presentations of products (plenum).

The creative days were very casual and informal. The common meeting points were the regular meals and short meetings to discuss the work twice a day. The pace during the creative days was much slower, with time for focus, exchange and inspiration. The work literally turned into a creative retreat of concentrated productivity.

The concluding presentations and the joint travel back home became the highlights and the formal finale of the workshops.

5. Results: the storylines on futures created in the workshops

Throughout the two workshops the participants created a number of different narratives (stories). In comparison to other previously conducted workshops with professionals from transport planning, these workshops unlocked a new and unexpected level of complexity. In the critique phase it was framings like the following that got the most votes: ‘Increased segregation’, ‘lack of trust and communities’, ‘dramatic increase of conflicts in urban space’. The utopian phase generated framings like: ‘Kindness’, ‘circular economy’, ‘less mobility – better lives?’. This lead into realizations quite different to what we have seen from previous projects. The then realizations were more instrumental in the way of i.e. ‘In the future we will have a mobility ministry’, ‘In the future people choose transport modes based on specific errands’ (Freudendal-Pedersen et al., 2017).

In the following, we focus on two of the projects developed in the realization phase and visualized in the creative retreat. The reflections on the projects are a compilation of the discussions we had with the participants when the project was presented to them.

5.1. The circular city

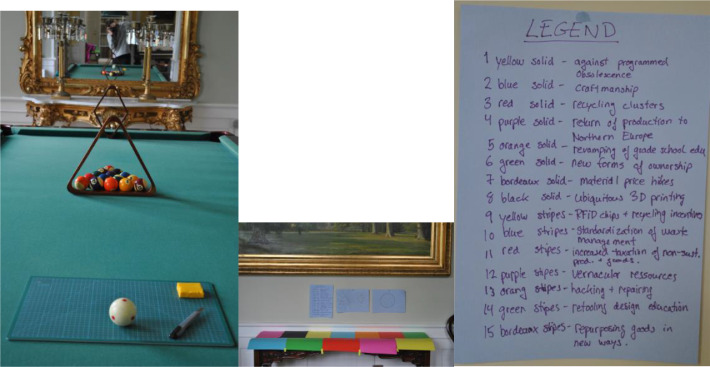

This project developed during the workshop in Denmark. It focuses on reordering the flows of materials and resources and the way of production towards sustainability. It was one member of the group driving the project in collaboration with others. The aim was to create cities that produce the materials needed to uphold ways of living while always making sure that everything can flow back into the city's metabolism.

The overall focus was on the production and supply chains behind and attached to material products. The group working in it followed the rationale that many work steps and activities can stay within the urban space, such as the cleaning, sorting, packing of materials and the actual process of producing things (like clothes). Outside of the city e.g. the crop is cultivated that is needed to produce sweaters or trousers. The production of raw materials is the backbone that guarantees the materials being used in the city. Recycling and the mobility of different materials was on a very advanced level in the model developed by the participants. They aimed at reducing the unsustainability of the mobility in the production process.

The key idea of the model was to recycle waste for new productions and applications and to have new materials coming from nature while maintaining biodiversity. Of course, this is not a completely new idea, thinking for instance of cradle to cradle flows of production and consumption. But the group put this together with the process of synthetic biology as one of the production forms. The industrial designer part of this realization was already working with growing natural materials. This could for instance be growing proteins based on a bacteria base on a smaller scale, e.g. silk from honeybees or from spiders. One of the ideas was a growing plant where materials grow into a specific shape. This presented new ways of re-thinking production. The idea came from the challenges that a lot of materials are actually produced and invented in natural science, but there is not enough exchange and interaction between engineers, planners, designers and architects. Instead of using synergies and experience that others have in the field, business as usual was predominant. This aspect strongly demands for new ways of organizing knowledge transfer and collaboration. It shows that competition is very often counter-productive when it comes to sustainability issues. This idea liberates an amazing amount of resources in relation to energy use and less mobilities of goods. Most of the imagined products are not only biodegradable, they are also biocompatible.

One of the artists involved in this project decided to create an art installation by using only materials already present in the rooms where the workshop took place. A pool table became the center of the installation where all the elements of the circular city were contained. The discussions amongst the participants revealed very individual interpretations of the circular economy based on this spin-off art project.

The pool balls and papers indicate elements talked about during the different phases in the workshop. When the balls are placed at the table in random order they can constantly be reorganized. They have the same meaning (defined by their color). but their effect and the interpretation changes when they are placed randomly or consciously in new sequences. The papers in different colors extrapolate ideas and notions of the circular economy; it is up to the audience to tie them on to the elements on the table. The cutting board symbolizes the building or modeling of something, but the ball pushes it into the shape and changes the configuration. Mobilities are always present to change things. The legend is taken from the timeline made in the realization phase, it thus becomes a scrambling of time, information and elements. Everybody can see and move the pool balls, the sheds of paper and the words differently. But there are also skills involved in how the timeline and table of circular economies unfold. The shapes look like something you need to put the ball in, but it is unattainable. There are strong obstacles framing the resources. Thereby, it becomes more an object of contemplation than a game and as an observer one gets to a point where thoughts are interacting with the object. In other words: The complexity steps in.

The holes in the pool table can be interpreted as holes we need to be careful not to fall into when we become too mono-disciplinary and loose the overview. Things and perceptions change when you pick up a ball and touch it. The installation can be read as the ability to govern, how to handle all these different pieces and their interplay. Also how would things look entirely differentl if the balls were shaped by the strange triangle, it symbolizes systems taken for granted and the path dependencies of planning and mobilities. The question becomes: what would change if we modified the form and with it the framing?

At the evaluation dinner in Copenhagen many of the participants referred to the Circular City project. One of the participants, a designer, part of creating this idea, said

‘Well, [the workshop] basically gave me a new perspective on my own work. I haven't expected that at all. I expected to learn and to hear new things. But I haven't expected this workshop to make me consider what I am doing from a new angle. And that was really interesting.’

In the follow-up discussion she reported ‘the workshop made me realize how important mobility is’ and that it is ‘present in my daily work’. During the workshop she has been working on the concept of the Circular City and figured out that a lot of it has to do with the management and the structuration of mobility from logistics and infrastructures to the consumption and the reuse of products. After the workshop she decided to start a PhD, since she learned how many open questions she still had on the topics. Her PhD has been finished and published in the meantime.

The argument here is not that the reflexive methodology is the full answer on the complex questions of the transition of cities towards sustainable mobility. It is also not to say that the two workshops alone could initiate lasting and deep-going social and political transformations. What we want to emphasize instead is: The data shows a significant potential to initiate processes that can facilitate such changes. Since talk on change management is omnipresent these days, discursive processes aiming at the transformation of urban mobility systems, the automotive industry or towards a sustainable mobility culture have made it to the top of the political agenda. The work presented here marks a different perspective. It indicates that serious conceptual and practical change needs time, space and resources for changing perspectives.

The advanced workshop structure with five instead of three phases gave the opportunity for a deeper understanding and more sophisticated investigation of the complexities of the circular economy idea – without being merely academic. Since real social innovation often is based on individual sensory and haptic experiences, the advanced methodology opens up opportunity spaces for new ideas and the design of innovative policies. In light of the Covid-19 pandemic, this way of thinking about circles of production as well as the learning in-between different disciplines becomes highly relevant. The socially innovative ideas generated in the realization phase can be grounded more substantially and open up perspectives for new development paths.

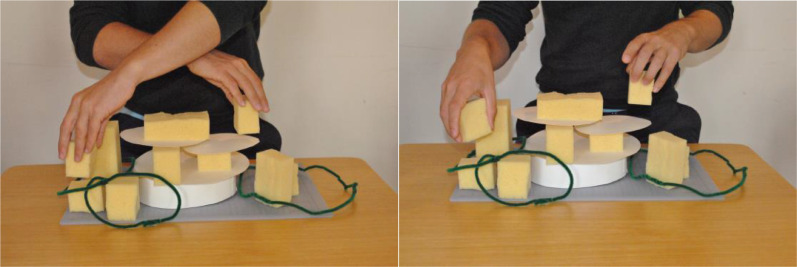

5.2. The Cube City Manifesto for a randomized city

The second project was developed on the German workshops and is abstract in a different way than the circular city project. It shows the radical character of art-based research methods and their capacity to push people literally to thinking out of the box and into new directions. This realisation, developed by a team of two artists and one scientist, was titled Cube City Manifesto. It pushes ideas of mobile architecture, of mobile urban life, movable and flexible urban elements and structures to the end and to an extreme. The manifesto pleads for a city that intentionally breaks up given social structures with hierarchies, families, communities, neighbourhoods and belongings and continuously renews social configurations. This forces people to permanently change and readjust points of view and eliminates social situations of standstill and inertia.

The group developed a screenplay for a Cube City film based on a manifesto with five essential premises:

Manifesto for a Randomized City.

-

1

We must build a randomized city!

-

2

The city has mobile architectural elements and structures that are disrupting given social contexts.

-

3

The city must continuously renew our points of view and enrich our lives!

-

4

The city must supply a self-moving system for transportation and living.

-

5

The city must continuously vibrate!

With their manifesto the authors critically refer to postmodern concepts of mobility and the mobilities turn in social science (Benjamin, 1983; Deleuze & Guattari, 1987; Jensen et al., 2019; Sheller & Urry, 2016). They challenge traditional ways of seeing cities as places of identity, belonging and rootedness. In fact, they consciously ignore sociological knowledge and disciplinary state-of-the-art assumptions about the human need for social embeddedness and the critique of the “liquid modernity” (Bauman, 2000; Beck, 2018; Giddens, 1991). Instead, they emphasize how the Cube City as a sort of perpetuum mobile enriches the lives of the observers and the people inhabiting them. A key aspect of the Cube City is its self-sustaining movements and the continuous flows of in- an outgoing materials, people, ideas, signs and information. The Cube City, as the authors consider it, is a never sleeping, ‘constantly vibrating’ complex. There is steady movement between its different elements which define the urban in different ways. As an example, homes are places on the move together with other basic spaces, such as hospitals, grocery stores, etc. from richer parts of the city to the poorer parts. As the manifesto puts it, the Cube City should be reorganized and reconfigured on a specific day – every year. On this day citizens are required to stay in their homes, the ‘boxes’, while they are being removed to an unknown randomized destination. The essential elements of citizens’ lives remain with them when being moved. Non-essential elements will be shifted and transferred on that specific day and this generates new experiences and interactions with new and so far unknown people. If people love their partners and children, they will stay together on the moving day. If they are bored, however, and do not strongly connect with them, this movement will allow them to experience new things, new opportunities to let go of non-essential elements and to take up more essential ones. This artistic project unraveled some deep layers of the discourse on mobilities and the urban. It raised ontological questions and problems of modern lives: what is identity, belonging? Why do people need stability and reliability? How much insecurity, uncertainty and mobility can people manage and bear? How much movement and change can people handle in urban environments? And what is the backbone of society, the social glue?

For some of the participants these ideas felt quite extreme and some chose to opt out of the presentation and discussion. What we mentioned as the radical character of artistic methods before, became literally perceptible and tangible. We saw participants running in an out of the room before they decided to stay or to leave the presentation. The Cube City project unfolded its radical and provocative character by putting the ontological questions from above centre-stage.

The Cube or Randomised City is a permanently growing autopoietic system of modular mobile dwellings. Its housing units are identical in scale and correspond to a specifically developed system. Every single one can thus be removed from its current housing block and be exchanged with other units – similar to boxes in a systematized warehouse or on a container ship. The traffic system consists of a ground similar to a belt conveyor that enables travellers to make use of services, coffee shops, libraries, etc. while driving to their destination. In short, the traffic system itself offers a quality of stay in the public domain. The units in city houses, their resident(s) and all belongings apart from kitchens, bathrooms, balconies and so forth are different from the other building systems. At the end of each year, the whole unit will be transported to another, completely random position in the urban building system and in a completely different neighbourhood. The system makes sure that if you stay with your small kids, the facilities in relation to your box will fit the families’ needs. This means that there will be no need to rebuild or add to the existing housing. The system makes public domain vibrate incessantly so that the residents are constantly reminded of the “thrownness” of their own existence and at the same time permanently subliminally sexually aroused which engenders a noticeably corporeal sense of community. When the city becomes randomized again and again, it means that the divisions between rich and poor, young and old, successful and in need, long-established and non-native, etc. is turned completely upside down. It is no longer possible to gather in ‘ghettos’ or bubbles with like-minded people and peers. This effectively prevents gentrification since family ties, long-established neighbourhoods, gridlocked acquaintances are constantly forced into radical new beginnings and ways of thinking.

As mentioned before, to some participants this was very provocative within the workshop situation. But at the evaluation dinner it was mentioned as a significant learning experience as the following statement from one of the workshop participants shows:

‘The first thing that pops into my mind from the workshop is the Randomized City project. On the one hand, it is so far away from reality, but on the other side it is so obvious. It's not a solution but it was a mind-blowing moment and a thing that opened up new lines of thought.’

Following up on this he puts his statement into perspective by saying

‘I need to say, it doesn't help me in my daily work and life. Ok, I need to … move on.’

But then he ended up by saying

‘(…) it was really, oh, wow! I've never looked at this like you guys. This was also, really…. And I think, in real life, in research and scientific discussions and hopefully in the future also in the industry, more of these cross-, inter-disciplinary topics are needed. Otherwise you are just losing the focus on who really needs solutions. Not only we as mobility specialists but in general.’

To a certain extent this statement proves the project's main assumption: by using a reflexive approach in future research it is possible to initiate changes of perspective and the abandoning of traditional ways of thinking. Interestingly enough the Randomized City was quite difficult to handle for several of the participants. Only the facilitators stayed until the very end of the presentation. We interpret this as a reaction to the massive dystopian energy of this project. It gives access to a level of understanding and experience of the emotional, social and cultural dimension of the hypermobile city that cannot be reached by other methods and forms of investigation. This is frightening, but as we could see during the evaluation dinner, it also stimulates deep reflections that can be used for identifying new policies and approaches. The power of art comes through in its way of making a point, making an impression that stays strong and prompts reflections for a long time. The Cube City project systematically radicalizes and rethinks the postmodern culture of mobility to an end and to a point where the social, cultural and disrupting aspects of a hyper-mobilized society become visible. This way, art can give access to a level of experience that traditional forms of science (such as modeling, scientific analysis and quantitative trend analysis) cannot open up. In a situation where transition and transformation towards sustainability is on top of urban agendas, methodological approaches are needed that can redirect lines of thoughts, rationales up to urban strategies and policies into new directions beyond path dependencies (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 1.

Applied Method.

Fig. 2.

The thing from the future card game.

Fig. 3.

Communication rules.

Fig. 4.

Circular city.

Fig. 5.

Circular city art work.

Fig. 6.

Randomized city art work.

6. Concluding remarks

With the Corona crisis the relations between mobilities and urban life become a new twist. Suddenly, transportation networks from local public transport to global aeromobilities do not guarantee the spatial integration of societies any more. Rather, mobility became an even higher risk than it was perceived before. Digital communication networks revealed as yet unexploited potentials for keeping social life and business up and running, even reducing health risks at the same time. Staycation, Stay safe, stay at home and so forth became private and public policies of the moment. Everything got altered – not in a randomized way – but suddenly people where bound to their little boxes and big parts of society was turned into “motile hybrids” (Kesselring, 2008a: 93). In a form of “mobile immobility” (Bonß & Kesselring, 2001) many people were forced to stay put at home while being highly active and present somewhere else for teaching, business, consultancy, coaching, in the media and elsewhere. Again, not randomized but still very different from the taken for granted organisation of everyday lives, millions of people became mobility pioneers by practicing forms of interaction at a distance (Kesselring, 2006).

How much of the new culture of “mobile immobility” will remain after Corona will keep us all and thousands of researchers busy for the next couple of years? The inequality of mobilities has especially been highlighted and the mobile immobility does not apply to many migrant workers for instance where the actual physical mobility on foot or in busses entails even more health risks than their working conditions alone. These and many other issues of inequality have been resealed from COVID-19.

In many ways COVID-19 can function as an eye-opener and create momentum, not least in relation to what we want to do with the future of our cities. Environmentally sustainable and socially resilient cities have long been on the agenda. But post COVID-19 might create openings towards new methodologies: to re-think ways of planning the future of societies. The transdiciplinary approach has long been discussed; but still planning of the future often falls back into silo thinking. Through the two workshops facilitated in Denmark and Germany a big amount of rich data shows the potential for activating transdiciplinarity in a reflexive methodology that opens up a different discursive level and create another view into mobilities, the good life and the future of cities.

The methodological innovation of the ‘common ground phase’ and the ‘creative retreat’ can be seen as a sensible and efficient modification of the original method. It literally contributes to building up common ground and a trustful fundament for the three phases of the future workshop and the subsequent retreat. Following the usual three phases of future workshops, the creative retreat gave room to elaborating and strengthening the results from the realization phase. It provided the space for preparing knowledge transfer and translating the results. Transferring knowledge into policy is an ongoing challenge for research. With the specific group chosen for the workshops we attempted to address elites already having a voice, being in municipal planning and policy, research, consultancies or art. Evaluating the two workshops, we could see that the ways of working, defining problems and addressing issues has changed for some of the participants. We are aware of the limitations of the data and it needed follow-up research to proof the hypotheses. But the project clearly showed a possible way into facilitating transformation and also what a change in urban planning could look like and how taken-for-granted assumptions and procedures can be modified.

The project has been developed and conducted in the tradition of critical action research. The article here systematically discusses its contribution to develop further the debate on methodologies. It points out the innovative value and the transformative quality of the approach. The role of utopian as well as dystopian stories as a key element in critical utopian action research was strongly influenced by artistic interventions. They used provocation as an intended technique, enforcing reflection to re-adjust taken-for-granted elements of the world and (planning) concepts.

Thus there were a lot of promising results from the project, but they also need to be put into perspective. The scope and outreach of two five day workshops is limited, even if five days are quite a long time. Each workshop worked as a micro-cosmos for experiments. However, to look for answers to all the complicated questions of reflexive future planning would be stretching it too far. Planning is a social and ideally a collaborative process that builds up networks of shared expertise and responsibility.

The Mobilities Futures & the City workshops have been social experiments with transdisciplinary, inter-discursive communication, the social construction of trust and a capacity to envision the future. The aim of the project was to investigate how it is possible to find an organizational setting for enabling a group of actors to think differently about the future of mobilities and the city. To sum it up: there is no doubt, the different utopias and projects have quite some potential. Some of them even seriously challenge taken-for-granted ways of understanding the future of urban mobilities and re-conceptualize things radically – literally: ‘from the roots’.

The participants approached each other with a high level of respect and recognition. This could be the basis for designing solutions and policies which are not primarily following an expert rationality, but are deeper rooted within societies and the urban context. This is exemplified in the following statement by a Danish architect:

‘It was a kind of eye-opener to see how mobility transformed throughout the time that we spent together into different other fields. Even as it wasn't upfront and always present.’

One of the people in the workshop, strongly involved in administrative and political routines and processes, emphasized how this created a new space for innovative thinking:

‘Just by going there (…) and meeting all you people, gave me more than spending three days in the office. (…) This is the biggest problem in my working life that we are doing something here and there and then we start something at a different place. This is so ineffective and we jump from one job to another. Everybody at my office wants to have more time to focus. And this is what this method does, it generates concentration. This is so efficient, we should be trained in this. This would make a difference as well as innovative ideas.’

This project shows great possibilities of the approach but it also reveals some weak points. One is that the dynamics and energy generated in a process like this can easily fall flat after a while. Providing this kind of opportunity for new forums and spaces for reflection, discussion and co-creation entails the responsibility for taking care of the results. If we want to use them for planning and designing alternative futures for urban mobilities, we need to take their character for serious as social interactive processes. We need to think about having these activities in a steady sequence and help them to become stronger. Roughly said we started a process with the workshops, we engaged people and we got them to invent alternative futures. But since the project ended we could not be part of the continuation of the concepts. Nevertheless, this being said, the results show that it is possible to handle the complexities of a reflexive setting of actors, expertise and orientation. But, to generate results strong enough to be policy-relevant and ready for reality-check, the process needs to be perpetuated and put into a framework that allows an iterative process from the initial ideas to policy recommendations, instruments, measures, products and services.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors do not have any competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Comment: Color pictures being used in the text can be reproduced in b/w.

See i.e. Melkonyan et al., 2020; Broo et al., 2021.

References

- Bauman Z. Polity Press; Cambridge: 2000. Liquid modernity. [Google Scholar]

- Beck U. Sage (Theory, culture and society); London: 1992. Risk society. Towards a new modernity. translated by Mark Ritter. [Google Scholar]

- Beck U. In: Exploring networked urban mobilities: Theories, concepts, ideas. 1st. Freudendal-Pedersen M, Kesselring S, editors. Routledge (Networked urban mobilities series, volume 1); New York, NY: 2018. Mobility and the cosmopolitan perspective; pp. 140–152. [Google Scholar]

- Beck U., Bonss W., Lau C. The theory of reflexive modernization. Theory, Culture & Society. 2003;20(2):1–33. doi: 10.1177/0263276403020002001. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin W. Suhrkamp; Frankfurt/Main: 1983. Das Passagenwerk. [Google Scholar]

- Bladt M., Nielsen K.A. Free space in the processes of action research. Action Research. 2013;11(4):369–385. doi: 10.1177/1476750313502556. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonß W., Kesselring S. In: Die Modernisierung der Moderne. 1. Aufl. Beck U, editor. Suhrkamp (Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft, 1508); Frankfurt am Main: 2001. Mobilität am Übergang; pp. 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Broo D.G., Lamb K., Ehwi R.J., Pärn E., Koronaki A., Makri C., Zomer T. Built environment of Britain in 2040: Scenarios and strategies. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2021;65 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Büscher M., Freudendal-Pedersen M., Kesselring S., Kristensen N.G. Edward Elgar Publishing (Handbooks of Research Methods and Applications Series); Northampton: 2020. Handbook of research methods and applications for mobilities. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Acey C., Lara J.J. Sustainable futures for Linden Village: A model for increasing social capital and the quality of life in an urban neighborhood. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2015;14:359–373. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2014.03.008. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell T. Valuing mobility in a post COVID-19 world. Mobilities. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1080/17450101.2020.1863550. In. 0 (0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deckha N. Insugent urbanism in a railway quarter: Scalar citizenship at King's Cross, London. ACME An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies. 2003;1(2):33–56. http://www.acme-journal.org/vol2/Deckha.pdf In. Available online at. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze G., Guattari F. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis: 1987. A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. [Google Scholar]

- Egmose J., Gleerup J., Nielsen B.S. Critical utopian action research: Methodological inspiration for democratization? International Review of Qualitative Research. 2020;13(2):233–246. doi: 10.1177/1940844720933236. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen T.H. Pluto Press; London, Sterling, Va: 2001. Tyranny of the moment. Fast and slow time in the information age. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Frank, Forester, John . Univ. College London; London: 1993. The argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Frank, Gottweis, Herbert . Duke University Press; Durham, N.C., London: 2012. The argumentative turn revisited. Public policy as communicative practice. ebrary, Inc.http://site.ebrary.com/lib/alltitles/docDetail.action?docID=10571137 (Eds.) Available online at. [Google Scholar]

- Freudendal-Pedersen M., Hartmann-Petersen K., Kjærulff A.A., Nielsen D., Lise Interactive environmental planning: Creating utopias and storylines within a mobilities planning project. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 2017;60(6):941–958. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2016.1189817. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freudendal-Pedersen M., Hartmann-Petersen K., Nielsen L.D. In: Mobile methodologies. Fincham B, McGuinness M, Murray L, editors. Palgrave Macmillan; Basingstoke: 2010. Mixing methods in the search for mobile complexity; pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Freudendal-Pedersen M., Kesselring S. Mobilities, futures & the city: Repositioning discourses - changing perspectives - rethinking policies. Mobilities. 2016;11(4):575–586. doi: 10.1080/17450101.2016.1211825. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freudendal-Pedersen, Malene, Kesselring, Sven . In: Exploring networked urban mobilities: Theories, concepts, ideas. 1st. Freudendal-Pedersen M., Kesselring S., editors. Routledge (Networked urban mobilities series, volume 1); New York, NY: 2018. Networked urban mobilities; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Freudendal-Pedersen M., Kesselring S. What is the urban without physical mobilities? COVID-19-induced immobility in the mobile risk society. Mobilities. 2021;16(1):81–95. doi: 10.1080/17450101.2020.1846436. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gehl J. Island Press; Washington and Covelo and London: 2010. Cities for people.http://site.ebrary.com/lib/academiccompletetitles/home.action Available online at. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. Polity Press; Cambridge: 1991. Modernity and self-identity. Self and society in the late modern age. [Google Scholar]

- Grin J., Rotmans J., Schot J., Geels F.W. Routledge (Routledge Studies in Sustainability Transitions, 1); New York, NY: 2010. Transitions to sustainable development: New directions in the study of long term transformative change.http://www.gbv.de/dms/zbw/608517992.pdf Available online at. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer M.A. Zero-friction society. Urban Design Quarterly. 1999;71:29–34. In. [Google Scholar]

- Harlan V., Rappmann R., Schata P. Achberger Verlagsanstalt; Achberg: 1976. Soziale Plastik. Materialien zu Joseph Beuys. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. Edinburgh University Press; Edinburgh: 2000. Spaces of hope. [Google Scholar]

- Healey P. In: The argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning. Fischer F, Forester J, editors. Duke University Press (Duke backfile); Durham, N.C.: 1993. Planning through debate: The communicative turn in planning theory; pp. 233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Healey P. On creating the 'city' as a collective resource. Urban Studies. 2002;39(10):1777–1792. doi: 10.1080/0042098022000002957. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O.B., Freudendal-Pedersen M. In: Utopia. Social theory and the future. Jacobsen M.H., Keith T., editors. Ashgate (Classical and contemporary social theory); Farnham: 2012. Utopias of mobilities; pp. 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O.B., Kesselring S., Sheller M. Routledge; London and New York: 2019. Mobilities and complexities. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Jungk R., Müllert N. Institute for Social Inventions; London: 1987. Future workshops. How to create desirable futures. [Google Scholar]

- Kesselring S. Pioneering mobilities: New patterns of movement and motility in a mobile world. Environment and Planning A. 2006;38(2):269–279. doi: 10.1068/a37279. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kesselring S. In: Tracing mobilities: Towards a cosmopolitan perspective. Canzler W., Kaufmann V., Kesselring S., editors. Ashgate; Aldershot and Burlington: 2008. The mobile risk society; pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kesselring S. In: Tracing mobilities. Towards a cosmopolitan perspective. Canzler W., Kaufmann V., Kesselring S., editors. Ashgate; Aldershot: 2008. The mobile risk society. (Transport and society) [Google Scholar]

- Kesselring S. In: Das Risik. Gedanken übers und ins Ungewisse. Interdisziplinäre Aushandlungen des Risikophänomens im Lichte der Reflexiven Moderne. Eine Festschrift für Wolfgang Bonss. 1st. Pelizäus H., Nieder L., editors. Springer VS (Research (Wiesbaden, Germany)); Wiesbaden: 2019. Reflexive Mobilitäten; pp. 155–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kesselring S., Tschoerner C. The deliberative practice of vision mobility 2050: Vision-making for sustainable mobility in the region of munich? Transportation Research Procedia. 2016;19:380–391. doi: 10.1016/j.trpro.2016.12.096. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaerulff, Aamot A., Kesselring S., Peters P., Hannam K. Routledge Taylor and Francis (Networked Urban Mobilities Series, volume 3); New York and London: 2017. Envisioning networked urban mobilities. Art, performances, impacts. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre H. Blackwell Publishers; Oxford: 1996. Writings on cities. With assistance of Eleonore Kofman, Elizabeth Lebas. [Google Scholar]

- Melkonyan A., Koch J., Lohmar F., Kamath V., Munteanu V., Schmidt J.A., Bleischwitz R. Integrated urban mobility policies in metropolitan areas: A system dynamics approach for the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan region in Germany. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2020;61 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102358. In. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miciukiewicz K., Vigar G. Mobility and social cohesion in the splintered city: Challenging technocentric transport research and policy-making practices. Urban Studies. 2012;49(9):1941–1957. doi: 10.1177/0042098012444886. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitteregger M., Bruck E.M., Soteropoulos A., Stickler A., Berger M., Dangschat J.S., et al. Springer Vieweg; Berlin, Germany: 2020. AVENUE21 - automatisierter und vernetzter Verkehr: Entwicklungen des urbanen Europa. [1. Auflage] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen K.A., Nielsen B.S. In: Action research and interactive research. Beyond theory and practice. Svensson L., Nielsen K.A., editors. Shaker Publishing; Maastricht: 2006. Methodologies in action research; pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen L.D. In: Action research and interactive research. Beyond theory and practice. Svensson L., Nielsen K.A., editors. Shaker Publishing; Maastricht: 2006. The methods and implications of action research: A comparative approach to search conferences, dialogue conferences and future workshops; pp. 89–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pinder D. In defence of utopian urbanism: Imagining cities after the ‘end of utopia’. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography. 2002;84(3-4):229–241. doi: 10.1111/j.0435-3684.2002.00126.x. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder D. Routledge; New York: 2005. Visions of the city. Utopianism, power and politics in twentieth-century urbanism. [Google Scholar]

- Pinder D. Urban interventions: Art, politics and pedagogy. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2008;32(3):730–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00810.x. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandercock L. Out of the closet: The importance of stories and storytelling in planning practice. Planning Theory & Practice. 2003;4(1):11–28. doi: 10.1080/1464935032000057209. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandercock L. In: Multiculturalism. Baumann G., Vertovec S., editors. Routledge (Critical concepts in sociology); London: 2011. Transformative planning practices. How and why cities change; pp. 158–183. [Google Scholar]

- Sheller M., Urry J. Mobilizing the new mobilities paradigm. Applied Mobilities. 2016;1(1):10–25. doi: 10.1080/23800127.2016.1151216. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shokouhyar S., Shokoohyar S., Sobhani A., Jafari G., Amirsalar Shared mobility in post-COVID era: New challenges and opportunities. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2021;67 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.102714. In. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson L., Nielsen, Kurt A. Shaker Publishing; Maastricht: 2006. Action research and interactive research. Beyond theory and practice. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson Lennart, Nielsen Aagaard., editors. Action research and interactive research. Beyond practice and theory. Arbetslivinstitutet i Sverige; Stockholm: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tofteng D., Husted M. Theatre and action research: How drama can empower action research processes in the field of unemployment. Action Research. 2011;9(1):27–41. doi: 10.1177/1476750310396953. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Urry J. Routledge (International Library of Sociology0); London, New York: 2000. Sociology beyond societies. Mobilities for the twenty-first century. [Google Scholar]

- Urry J. The ‘system’ of automobility. Theory, Culture & Society. 2004;21(4-5):25–39. doi: 10.1177/0263276404046059. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Virilio, P. (1977).: Vitesse et politique. Paris: Galilée (Collection l'espace critique).

- Westlander G. In: Action research and interactive research. Beyond theory and practice. Svensson L., Nielsen K.A., editors. Shaker Publishing; Maastricht: 2006. Researchers roles in action research; pp. 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Witzgall S., Vogl G., Kesselring S. Ashgate; Burlington VT: 2013. New mobilities regimes: The analytical power of the social sciences and arts. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development . World Business Council for Sustainable Development (The Sustainable Mobility Project); 2004. Mobility 2030:MEeting the challenges to sustainability.http://docs.wbcsd.org/2004/06/Mobility2030-ExSummary.pdf Available online at. checked on 1/11/2021. [Google Scholar]