Abstract

There is abundant evidence demonstrating the association between gut dysbiosis and neurogenic diseases such as hypertension. A common characteristic of resistant hypertension is the chronic elevation in sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity accompanied by increased release of norepinephrine (NE), indicating a neurogenic component that contributes to the development of hypertension. Factors that modulate the sympathetic tone to the cardiovascular system in hypertensive patients are still poorly understood. Research has identified an interaction between the brain and the gut, and this interaction plays a possible role in the mechanism of heart damage-induced hypertension. Data, however, remain scarce, and further study is required to define the role of microbiota in sympathetic neural function and its relationship with heart damage and blood pressure (BP) control. Experimental evidence has pointed toward a bidirectional relationship between alterations in the types of bacteria present in the gut and neurogenic diseases, such as hypertension. Our published data showed that miR-204, a microRNA that plays an important role in the CNS function, is affected by gut dysbiosis. Therefore, miR-204 could be a key element that regulates normal sinus rhythm and neuronal hypertension. In this review, we will shed light on the potential mechanism by which microbiota affects hypothalamic miR-204, which in turn, could hinder the sympathetic nerve drive to the cardiovascular system leading to arrhythmia and hypertension.

Keywords: cardiac arrhythmia, high blood pressure, cardiac electrophysiology, hypothalamic mir-204, sympathetic nerve activity

Introduction and background

The most common form of hypertension is neurogenic hypertension, which is defined as high blood pressure (BP) with sympathetic overdrive along with raised vasomotor tone and increased cardiac afterload [1]. Recently, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) has gained a lot of attention in hypertension. For instance, it has been shown that sympathetic abnormalities can influence the development and progression of cardiovascular damage. Furthermore, recent studies are demonstrating that sympathetic activation has an adverse prognostic effect in terms of morbidity and mortality on a variety of cardiovascular diseases [2]. This underlines the importance of modulating sympathetic activation as a goal for non-pharmacological as well as pharmacological interventions aimed at lowering elevated BP and decreasing heart damage.

Review

Previous research has established a bidirectional relationship between alterations in the types of bacteria present in the gut and neurogenic diseases such as hypertension and arrhythmia [3-6]. As well, several studies have shown that fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from hypertensive human and rat donors elevates the BP of recipient normotensive mice and rats, respectively, pointing out that gut dysbiosis plays a possible contributing role in hypertension [7-9]. Other studies also reported a close relationship between gut microbiota dysbiosis and the pathogenesis of arrhythmia [5, 10]. Data, however, remain scarce, and further investigation is required to define the role of gut dysbiosis on sympathetic function and its involvement in BP control and normal heart rate.

Recent literature shows that microbiota can regulate microRNAs (miRNAs) in the brain [3]. However, the exact mechanism through which the gut microbiota influences the expression of miRNAs remains unclear. miRNAs, a class of small, non-coding RNAs that target complementary messenger RNAs to either destabilize their structure or repress protein translation [11], regulate many cellular processes and human diseases such as hypertension, cancer, diabetes, arrhythmia, heart failure, and obesity [12]. MiR-204 is robustly expressed in many regions of the CNS [13, 14]. The absence of commensal bacteria results in the downregulation of miR-204 in the amygdala [15]. Moreover, germ-free conditions induce a transcriptional profile in the amygdala consistent with upregulation in neural activity and synaptic transmission [15]. Given the relationship between gut microbiota, the CNS, and miR-204 on one hand, and the importance of neuronal signals in regulating hypertension and heart rate on the other hand, we decided in this review to discuss whether miR-204 in the CNS regulates sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) and therefore functions as a molecular relay that converts gut bacterial signals into a neural output that affects cardiac electrophysiology and hypertension. Understanding the mechanism by which microbiota and hypothalamic miR-204 mediates SNA, heart function, and hypertension may lead to novel treatment strategies conferring the benefits of SNA control while also circumventing the potential risks of delivering live biologics.

Hypothalamic miR-204 and sympathetic nerve output

Increased sympathetic activity is a key factor in the development of hypertension and a major contributor to cardiovascular diseases [16, 17]. Neural control of BP is mediated by a core network of hypothalamic and brain stem nuclei [18]. The paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus plays an important role in regulating SNA [19]. Recent studies showed that increased levels of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the PVN led to increased sympathetic activity, BP, and arrhythmia [20-23]. Interestingly, miR-204 is highly expressed in the hypothalamus. Recent research has shown that decreased level of miR-204 is associated with an increased level of BDNF [24, 25]. Therefore, reducing the level of miR-204 in the PVN might lead to SNA via overexpressing BDNF.

Additionally, a study by Li DP and Pan HL showed enhanced glutamatergic synaptic input to PVN sympathetic neurons in hypertension [26]. In silico data showed that glutamate receptor (Grin2b) is a potential target for miR-204; therefore, new findings of glutamatergic synaptic plasticity in the PVN and miR-204 not only improve understanding of molecular mechanisms involved in the heightened activity of the SNS but also propose new therapeutic targets for treating drug-resistant neurogenic hypertension. Finally, accumulating evidence suggests that miR-204 downregulation in the hypothalamus could influence SNS and increase the SNA leading to hypertension.

SNA and cardiac electrophysiology

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays an essential role in regulating normal cardiac electrophysiology [27]. The sinoatrial (SA) node, the heart's natural pacemaker, consists of a cluster of cells situated in the upper part of the right atrium wall [28]. The SA node generates electrical impulses in the heart and is innervated by the SNS [29]. The ANS increases sympathetic outflow to the SA node in order to increase heart rate [29]. Alterations in autonomic tone may induce changes in local cellular electrophysiology that can manifest clinically as changes in heart rate and rhythm which eventually evolve into arrhythmia [29].

The parasympathetic division also innervates the SA node [30], and together, the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions play a critical role in fine-tuning heart rate [31]. An increase in SNA is often associated with a decrease in parasympathetic nerve activity (PSNA) [32]. The vagus nerve is a PSN known to innervate the heart and regulate its rhythm [33, 34]. A chronic decrease in vagal nerve activity will lead to an uncontrolled increase in heart rate, creating a high risk for arrhythmia [35]. Chronic increased sympathetic activity, decreased parasympathetic activity and cardiac electrophysiology alteration are significant factors in developing hypertension [34].

Noradrenaline (NE) released by activating sympathetic nerve fibers to the SA node in the heart acts through the beta-adrenergic receptor 1 (β1) to increase SA node firing, thus increasing heart rate and contractility [29, 36]. As suggested above, a decrease in miR-204 can significantly increase the SNA leading to more NE secretion, which eventually may lead to an alteration of normal cardiac electrophysiology.

As well, the vagus nerve also innervates the SA node and acts on the firing rate leading to a slower heart rate. The parasympathetic division releases acetylcholine (Ach) that binds to the muscarinic receptor (M2) in the SA node [36]. The M2 receptor is a Gi-coupled protein that , once activated by Ach, will delay the firing of the SA node [29, 37-39].

Based on this evidence, it would be interesting to study the effect of hypothalamic miR-204 deletion on sympathetic and parasympathetic activity, heart electrophysiology, and hypertension. Hypothalamic miR-204 downregulation can increase the level of BDNF and Grin2b, leading to increased SNA and decreased PSNA. This, in turn, can induce heart electrophysiology damage eventually leading to hypertension.

SNA and vasomotor function

ANS is also known to control the vasomotor activity of large arteries and small resistance arteries [40]. Literature has strongly established that sympathetic activity and vascular function are key factors in the development and prognosis of cardiovascular events and disease [40]. NE activates the alpha 1 (α1) adrenergic receptor, located in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC), to induce vasoconstriction [29, 41-43]. This, in turn, increases systemic vascular resistance and afterload [44]. The sympathetic nerves that innervate the vasculature display a physiological level of vascular tone activity. Increasing sympathetic outflow beyond this physiological level can cause more vasoconstriction that eventually leads to hypertension. Since we showed evidence that hypothalamic miR-204 downregulation leads to increased SNA, it would also be interesting to study the effect of this downregulation on vascular tone damage-induced hypertension.

Microbiota central miR-204 and cardiac electrophysiology

Commensal bacteria that inhabit the gut can modulate BP [45]. Interestingly, normotensive animals become hypertensive when transplanted with gut microbiota from hypertensive animals and vice versa [9]. Furthermore, patients with hypertension show specific alterations in gut microbial flora, suggesting that changes in gut microbial load and diversity (dysbiosis) contribute to the pathogenesis of hypertension [46-48]. Studies have shown that gut microbiota and its metabolites can play an important role in regulating cardiovascular diseases [49-51]. Recently, the potential role of the gut in the pathophysiology of arrhythmia and heart failure (HF) has received more attention [10, 52]. It has been shown that changing the composition of gut microbiota regulates the risk of HF [53, 54]. While more studies are needed to depict the mechanisms by which the microbiome regulates heart function, based on the previous evidence, we cannot overlook the fact that it also can affect the heart through the brain, thus leading to arrhythmia and hypertension.

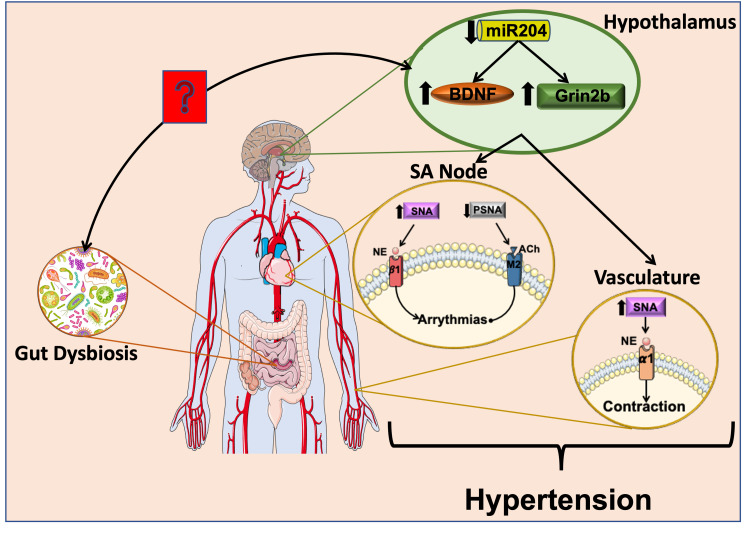

The gut microbiota is implicated in health and diseases through the regulation of host miRNAs [55]. In a previous study, we demonstrated that altering microbiota using antibiotics downregulated miR-204 in the vasculature [56]. Additionally, the absence of commensal bacteria resulted in the downregulation of miR-204 in the amygdala [15]. Altogether, these data indicate that microbiota can regulate miR-204 systematically as well as in the CNS, although the mechanism by which microbiota regulates miR-204 is yet to be determined. Yet, taken together, if the gut can affect hypothalamic miR-204, it will indeed affect the cardiovascular system function through the imbalance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve activity. The precise mechanisms on the above interactions and connections have not been fully elucidated and, thus, developing the proposed hypothesis in this review will open the door to a new concept of gut-brain axis miRNAs and cardiovascular diseases (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanistic model.

Gut dysbiosis decreases miR-204 level in the hypothalamus. Decreased miR-204 in the hypothalamus increases BDNF and Grin2B. These hypothalamic changes cause: 1) more SNA leading to pathophysiological levels of NE. NE acts on the ß1 receptor on the SA node and α1 receptor on the vasculature to produce cardiac and vessel contraction, respectively; and 2) less PSNA leading to a lower level of Ach. Ach activates the M1 receptor to reduce cardiac contraction. Deregulation in the level of NE and Ach will induce abnormalities in the heart and vessels, ultimately resulting in hypertension.

BDNF: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor; Grin2b: Glutamate receptor 2b; SNA: Sympathetic nerve activity; PSNA: Parasympathetic nerve activity; NE: Noradrenaline; Ach: Acetylcholine; ß1: Beta 1 receptor; M1: Muscarinic receptor 1; α1: alpha 1 receptor; SA: sinoatrial node.

Future directions

More attention should also be paid to the fact that electric pulses are not only controlled by the SA node. The atrioventricular (AV) node is part of the heart’s electrical conduction system [57]. The signal generated by the SA node passes through the AV node to the ventricles, causing them to contract in order to pump blood into the circulatory system [58]. Disturbance anywhere along this electrical pathway can cause arrhythmia. Like the SA node, the AV node is innervated by both SNS and PSNS [59, 60]. In the AV node, conduction velocity is markedly increased by NE [61]. Chronic SNA can lead to sustained increases in conduction velocity and lead to arrhythmias. Parasympathetic activation manifested by Ach release from the vagal nerve decreases conduction velocity at the AV node by decreasing membrane action potential [29]. Since hypothalamic miR-204 might regulate the SNS and the PSNS, it would be interesting to study its downregulation effect on the AV node function as well.

More studies should also investigate the microbiota effect on hypothalamic miR-204 and the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS). Renin is synthesized in juxtaglomerular cells (JC) in the kidneys [62], and it is already known that renin secretion is regulated by NE release [63]. Decreased levels of hypothalamic miR-204 can lead to increased renal SNA. Therefore, more NE will bind to the ß1 receptor on the JC and lead to higher levels of renin secretion. Renin is the major determinant of the angiotensinogen II (AngII) production rate [64]. AngII is a key component in regulating BP [65]. Consequently, when renin is increased, AngII will also increase. A chronic increase in AngII will lead to hypertension and heart remodeling that might lead to arrhythmia and HF [66].

Conclusions

Despite a wealth of studies over the last decade that has provided major insights into the gut-brain axis, miRNAs, and cardiovascular system control, we still have significant gaps in our knowledge. Thus, the central hypothesis of this review lies at the intersection of gut dysbiosis, miR-204, heart and vessels, and hypertension. It posits that gut dysbiosis, through reduction of hypothalamic miR-204, is a key driver of increased sympathetic overdrive to the heart and its vessels, leading to hypertension. It also puts forth the hypothesis that parasympathetic activity is reduced due to hypothalamic miR-204 reduction. Therefore, hypothalamic miR-204 is speculated to play a key role in a microbiota-gut-brain crosstalk and heart damage-induced hypertension.

The hypothesis discussed in this review is highly novel and, if accomplished, will lay the foundation for microRNA-based and/or microbiota-based therapeutics to prevent or treat heart damage-induced hypertension.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.The autonomic nervous system and hypertension. Mancia G, Grassi G. Circ Res. 2014;114:1804–1814. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The sympathetic nervous system alterations in human hypertension. Grassi G, Mark A, Esler M. Circ Res. 2015;116:976–990. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gut microbiome in health and disease: linking the microbiome-gut-brain axis and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of systemic and neurodegenerative diseases. Ghaisas S, Maher J, Kanthasamy A. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;158:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Impaired autonomic nervous system-microbiome circuit in hypertension. Zubcevic J, Richards EM, Yang T, Kim S, Sumners C, Pepine CJ, Raizada MK. Circ Res. 2019;125:104–116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.313965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Disordered gut microbiota and alterations in metabolic patterns are associated with atrial fibrillation. Zuo K, Li J, Li K, et al. GigaScience. 2019;8:0. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giz058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Different types of atrial fibrillation share patterns of gut microbiota dysbiosis. Zuo K, Yin X, Li K, et al. mSphere. 2020;5 doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00071-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alterations in the gut microbiota can elicit hypertension in rats. Adnan S, Nelson JW, Ajami NJ, Venna VR, Petrosino JF, Bryan RM Jr, Durgan DJ. Physiol Genomics. 2017;49:96–104. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00081.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Li J, Zhao F, Wang Y, et al. Microbiome. 2017;5:14. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0222-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lactobacillus fermentum improves tacrolimus-induced hypertension by restoring vascular redox state and improving eNOS coupling. Toral M, Romero M, Rodríguez-Nogales A, et al. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2018;62:0. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201800033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gut microbial composition in patients with atrial fibrillation: effects of diet and drugs. Tabata T, Yamashita T, Hosomi K, et al. Heart Vessels. 2021;36:105–114. doi: 10.1007/s00380-020-01669-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Role of specific microRNAs in regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation and the response to injury. Song Z, Li G. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3:246–250. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9163-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MicroRNAs in human diseases: from cancer to cardiovascular disease. Ha TY. Immune Netw. 2011;11:135–154. doi: 10.4110/in.2011.11.3.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MicroRNA: small RNA mediators of the brains genomic response to environmental stress. Hollins SL, Cairns MJ. Prog Neurobiol. 2016;143:61–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emerging roles of miRNAs in brain development and perinatal brain injury. Cho KH, Xu B, Blenkiron C, Fraser M. Front Physiol. 2019;10:227. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The microbiome regulates amygdala-dependent fear recall. Hoban AE, Stilling RM, Moloney G, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Clarke G, Cryan JF. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:1134–1144. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sympathetic neural mechanisms in human cardiovascular health and disease. Charkoudian N, Rabbitts JA. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2009;84:822–830. doi: 10.4065/84.9.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The sympathetic nervous system and blood pressure in humans: implications for hypertension. Fisher JP, Paton JF. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26:463–475. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hypothalamic and inflammatory basis of hypertension. Khor S, Cai D. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017;131:211–223. doi: 10.1042/CS20160001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The role of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in the regulation of cardiac and renal sympathetic nerve activity in conscious normal and heart failure sheep. Ramchandra R, Hood SG, Frithiof R, McKinley MJ, May CN. J Physiol. 2013;591:93–107. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.236059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.BDNF downregulates β-adrenergic receptor-mediated hypotensive mechanisms in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Thorsdottir D, Cruickshank NC, Einwag Z, Hennig GW, Erdos B. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2019;317:0. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00478.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cruickshank NC. 2017. The Effects of Hypothalamic Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor on Catecholaminergic Regulation of Cardiovascular Function. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inhibition of BDNF signaling in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus lowers acute stress-induced pressor responses. Schaich CL, Wellman TL, Einwag Z, Dutko RA, Erdos B. J Neurophysiol. 2018;120:633–643. doi: 10.1152/jn.00459.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates angiotensin signaling in the hypothalamus to increase blood pressure in rats. Erdos B, Backes I, McCowan ML, Hayward LF, Scheuer DA. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308:0. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00776.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MiR-132, miR-204 and BDNF-TrkB signaling pathway may be involved in spatial learning and memory impairment of the offspring rats caused by fluorine and aluminum exposure during the embryonic stage and into adulthood. Ge QD, Tan Y, Luo Y, Wang WJ, Zhang H, Xie C. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2018;63:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MicroRNA-204-5p mediates sevoflurane-induced cytotoxicity in HT22 cells by targeting brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Liu H, Wang J, Yan R, et al. Histol Histopathol. 2020;35:1353–1361. doi: 10.14670/HH-18-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glutamatergic regulation of hypothalamic presympathetic neurons in hypertension. Li DP, Pan HL. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19:78. doi: 10.1007/s11906-017-0776-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The autonomic nervous system in cardiac electrophysiology: an elegant interaction and emerging concepts. Kapa S, Venkatachalam KL, Asirvatham SJ. Cardiol Rev. 2010;18:275–284. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181ebb152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quantitative proteomics and single-nucleus transcriptomics of the sinus node elucidates the foundation of cardiac pacemaking. Linscheid N, Logantha SJ, Poulsen PC, et al. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2889. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10709-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Autonomic and endocrine control of cardiovascular function. Gordan R, Gwathmey JK, Xie LH. World J Cardiol. 2015;7:204–214. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i4.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Characterization of sinoatrial parasympathetic innervation in humans. Quan KJ, Lee JH, Geha AS, Biblo LA, Van Hare GF, Mackall JA, Carlson MD. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:1060–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Changes in heart rate and its regulation by the autonomic nervous system do not differ between forced and voluntary exercise in mice. Lakin R, Guzman C, Izaddoustdar F, Polidovitch N, Goodman JM, Backx PH. Front Physiol. 2018;9:841. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Role of parasympathetic inhibition in the hyperkinetic type of borderline hypertension. Julius S, Pascual AV, London R. Circulation. 1971;44:413–418. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.44.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardiac autonomic nerve distribution and arrhythmia. Liu Q, Chen D, Wang Y, Zhao X, Zheng Y. Neural Regen Res. 2012;7:2834–2841. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.35.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pharmacological modulation of vagal nerve activity in cardiovascular diseases. Liu L, Zhao M, Yu X, Zang W. Neurosci Bull. 2019;35:156–166. doi: 10.1007/s12264-018-0286-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Role of the autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation: pathophysiology and therapy. Chen PS, Chen LS, Fishbein MC, Lin SF, Nattel S. Circ Res. 2014;114:1500–1515. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Effects of acetylcholine and noradrenalin on action potentials of isolated rabbit sinoatrial and atrial myocytes. Verkerk AO, Geuzebroek GS, Veldkamp MW, Wilders R. Front Physiol. 2012;3:174. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.A multiplicity of muscarinic mechanisms: enough signaling pathways to take your breath away. Nathanson NM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6245–6247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The M2 muscarinic receptor, in association to M1 , regulates the neuromuscular PKA molecular dynamics. Cilleros-Mañé V, Just-Borràs L, Tomàs M, Garcia N, Tomàs JM, Lanuza MA. FASEB J. 2020;34:4934–4955. doi: 10.1096/fj.201902113R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The autonomic nervous system regulates the heart rate through cAMP-PKA dependent and independent coupled-clock pacemaker cell mechanisms. Behar J, Ganesan A, Zhang J, Yaniv Y. Front Physiol. 2016;7:419. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sympathetic regulation of vascular function in health and disease. Bruno RM, Ghiadoni L, Seravalle G, Dell'oro R, Taddei S, Grassi G. Front Physiol. 2012;3:284. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The functional role of the alpha-1 adrenergic receptors in cerebral blood flow regulation. Purkayastha S, Raven PB. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43:502–506. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.84950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calcium dynamics in vascular smooth muscle. Amberg GC, Navedo MF. Microcirculation. 2013;20:281–289. doi: 10.1111/micc.12046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Signaling in muscle contraction. Kuo IY, Ehrlich BE. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7:0. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vascular smooth muscle contraction in hypertension. Touyz RM, Alves-Lopes R, Rios FJ, Camargo LL, Anagnostopoulou A, Arner A, Montezano AC. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114:529–539. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gut microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease. Tang WH, Kitai T, Hazen SL. Circ Res. 2017;120:1183–1196. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alterations of the gut microbiome in hypertension. Yan Q, Gu Y, Li X, et al. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:381. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gut microbiota composition and blood pressure. Sun S, Lulla A, Sioda M, et al. Hypertension. 2019;73:998–1006. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gut microbiota in hypertension and atherosclerosis: a review. Verhaar BJ, Prodan A, Nieuwdorp M, Muller M. Nutrients. 2020;12:2982. doi: 10.3390/nu12102982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Role of gut microbiota in cardiovascular diseases. Novakovic M, Rout A, Kingsley T, et al. World J Cardiol. 2020;12:110–122. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v12.i4.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gut microbiota and cardiovascular disease: opportunities and challenges. Kazemian N, Mahmoudi M, Halperin F, Wu JC, Pakpour S. Microbiome. 2020;8:36. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00821-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gut microbiota and cardiovascular disease. Witkowski M, Weeks TL, Hazen SL. Circ Res. 2020;127:553–570. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.The gut microbiome in coronary artery disease and heart failure: current knowledge and future directions. Trøseid M, Andersen GØ, Broch K, Hov JR. EBioMedicine. 2020;52:102649. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duration of persistent atrial fibrillation is associated with alterations in human gut microbiota and metabolic phenotypes. Zuo K, Li J, Wang P, et al. mSystems. 2019;4 doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00422-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gut microbes role in heart failure explored. Kuehn BM. Circulation. 2019;140:1217–1218. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.The roles of the gut microbiota-miRNA interaction in the host pathophysiology. Li M, Chen WD, Wang YD. Mol Med. 2020;26:101. doi: 10.1186/s10020-020-00234-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vascular microRNA-204 is remotely governed by the microbiome and impairs endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation by downregulating Sirtuin1. Vikram A, Kim YR, Kumar S, Li Q, Kassan M, Jacobs JS, Irani K. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12565. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Electrophysiologic properties of the atrioventricular node in pediatric patients. Cohen MI, Wieand TS, Rhodes LA, Vetter VL. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:403–407. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00487-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farzam K, Ahmad T. Treasure Island, Florida: StatPearls Publishing; 2019. Sudden Death in Athletes. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.The distribution of sympathetic nerve fibres in the AV node and AV bundle of the bovine heart. Forsgren S. Histochem J. 1986;18:625–638. doi: 10.1007/BF01675298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.The influence of the parasympathetic nervous system on atrioventricular conduction. Martin P. Circ Res. 1977;41:593–599. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.5.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.[Pathophysiology of cardiac arrhythmias involving autonomic transmitters] Antoni H. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2881402/ Z Kardiol. 1986;75:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.The role of calcium in the regulation of renin secretion. Beierwaltes WH. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:0. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00143.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Control of renin synthesis and secretion. Kurtz A. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:839–847. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Classical Renin-Angiotensin system in kidney physiology. Sparks MA, Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Mirotsou M, Coffman TM. Compr Physiol. 2014;4:1201–1228. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Role of angiotensin II in blood pressure regulation and in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disorders. Fyhrquist F, Metsärinne K, Tikkanen I. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8583476/ J Hum Hypertens. 1995;9:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Angiotensin II-induced sudden arrhythmic death and electrical remodeling. Fischer R, Dechend R, Gapelyuk A, et al. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:0. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01400.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]