Abstract

The sex steroid hormones (SSHs) play several roles in regulation of various processes in the cardiovascular, immune, muscular and neural systems. SSHs affect prenatal and postnatal development of various brain structures, including regions associated with important physiological, behavioral, cognitive, and emotional functions. This action can be mediated by either intracellular or transmembrane receptors. While the classical mechanisms of SSHs action are relatively well examined, the physiological importance of non-classical mechanism of SSHs action through membrane-associated and transmembrane receptors in the brain remains unclear. The most recent summary describing the role of SSHs in different body systems is lacking. Therefore, the aim of this review is to discuss classical and non-classical signaling pathways of testosterone and estradiol action via their receptors at functional, cellular, tissue level and to describe the effects on various body systems and behavior. Particular emphasis will be on brain regions including the hippocampus, hypothalamus, frontal cortex and cerebellum.

Keywords: Sex steroids, Gonadal hormones, Brain structures, Intracellular receptors, Transmembrane receptors, Classical/non-classical signaling

1. Introduction

The sex steroid hormones (SSHs) are known not only as regulators of sexual differentiation, secondary sex characteristics, sexual behaviors, reproduction, but also affect various systems such as skeletal, immune, muscular, and cardiovascular. In addition, SSHs play a pivotal role in brain structure formation and cognitive function (Bhatia et al., 2014; Campbell & Jialal, 2020; Carson & Manolagas, 2015; dos Santos et al., 2014; McEwen & Milner, 2017). Furthermore, SSHs exert pleiotropic effects in the central nervous system promoting neurogenesis and neuroprotection, as well as learning and memory (Diotel et al., 2018; Frick & Kim, 2018; Sun et al., 2019). These effects are mediated not only via intracellular or membrane-associated receptors (such as the androgen receptor (AR), estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), estrogen receptor beta (ERβ)) but also via transmembrane receptors (such as zinc transporter protein 9 (ZIP9), G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1)). While the classical effects of SSHs via AR, ERα, ERβ are relatively well described, the physiological importance of rapid, non-classical actions of SSHs via membrane-associated (AR, ERα, ERβ) and transmembrane – GPCR steroid receptors (ZIP9, GPER1) is not well understood.

SSHs shape the brain during the critical prenatal and perinatal periods of development (organizational windows) when hormones interact with an immature neural substrate. In this period of life, exposure to SSHs can cause permanent sex differences in brain structures and their functions, which are responsible for the sexual differentiation of the brain and behavior (Cooke et al., 1998; Williams, 1986). Prenatal and perinatal effects of SSHs determine the brain’s response to steroids later in life. In addition, another “organizational window” during the postnatal period of life exists as well – puberty and adolescence (Schulz & Sisk, 2016; Vigil et al., 2016). Besides the organizational effects, SSHs also have activational effects on mature brain structures. Activational effects are acute, reversible and evoke transient behavioral or physiological responses throughout life (Cooke et al., 1998; Williams, 1986). In general, the activational effects of SSHs appear post puberty and act independently or in combination with organizational effects (Schulz & Sisk, 2016). Therefore, both activational and organizational effects of SSHs on the brain could affect behavioral outcomes later in life.

However, a current summary of results of experimental or clinical studies describing the role of testosterone (T) and estrogen (E, mostly estradiol (E2)) via classical and non-classical receptors and their role in different body systems is lacking. In this review, we aimed to sum up what is known and update the latest knowledge regarding the role of T and E2 in various tissues and body systems with specific focus on the brain via classical and non-classical signaling pathways. First, we discuss the specific effects of T and E (E2) via different receptors (AR, ERα, ERβ, ZIP9, GPER1) on various body systems. Subsequently, we describe the role of T and E2 in hippocampus (HIP), hypothalamus (HYP), frontal cortex (FC), and cerebellum (CER) – selected brain regions associated with important physiological, behavioral, cognitive, and emotional functions.

2. Androgens and estrogens

There are three major classes of sex steroid hormones – androgens, estrogens and progestogens. Androgens are known as primary “male sex hormones” because of their masculinizing effects and Es, together with progestins, as primary “female sex hormones”. However, all of these hormones are synthesized in both, females and males in different concentrations. Testosterone (T), the major androgen, is aromatized to estradiol by the enzyme aromatase and also reduced to the non-aromatizable androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by 5α-reductase (Celotti et al., 1997).

As mentioned previously in the introduction, these hormones play a crucial role throughout the development and exert diverse physiological functions in the body (Bhatia et al., 2014; Campbell & Jialal, 2020; Carson & Manolagas, 2015; Diotel et al., 2018; dos Santos et al., 2014; Frick & Kim, 2018; McEwen & Milner, 2017; Sun et al., 2019). Moreover, SSHs are also implicated in the development of the neurodevelopmental, neurodegenerative, and affective disorders (Crowley, 2017; McHenry et al., 2014; Morrell et al., 2005; Pinares-Garcia et al., 2018; Vadakkadath Meethal & Atwood, 2005). To exert these effects, SSHs must activate the signaling cascade via binding to appropriate intracellular, membrane-associated, or transmembrane receptors.

2.1. Receptors for androgens and estrogens

The actions of androgens and estrogens were historically thought to be slow, nuclear processes mediated through hormone receptors located in the cytoplasm complexed to chaperons or in the nucleus, i.e. intracellular AR and ERs (Walters et al., 1981). These processes of intracellular hormone receptors usually result in transcription of specific genes (genomic actions) which may take several hours. For such gene transcriptional responses, the ligand-receptor complex must be localized in the nucleus (Métivier et al., 2003). Later, it has been discovered that ligand-intracellular receptor complexes might be associated with the plasma membrane and can stimulate fast, non-classical processes in the cytoplasm occurring within seconds or minutes (Morley et al., 1992). These actions include various extranuclear downstream cascades regulating different cellular responses, such as DNA synthesis, cell proliferation, migration or survival (Schwartz et al., 2016). Thus, the same intracellular receptor may be responsible for both genomic and rapid responses. The shape and conformational flexibility of the ligands and ligand-binding domains (LBD), e.g. the open/closed position of helix-12, determines whether the accommodated ligand will be agonist/antagonist of the genomic or rapid action (Norman et al., 2001, 2004; Zinn & Schnell, 2018). According to the X-ray structure analysis, there are numerous different LBDs of nuclear steroid-hormone-receptors described in the Protein Data Bank (Bourguet et al., 2000). In several steroid receptors, the presence of a classical and a putative alternative binding site has been identified, mediating the genomic or rapid actions, respectively (Norman et al., 2004). It has been shown that some inter-molecular interactions, such as interactions with a scaffold-proteins or membrane proteins in the caveolae (Fridolfsson et al., 2014), as well as the occupancy of the classical ligand pocket and the absence of the coactivator protein (Bálint et al., 2017) may facilitate conformational changes of the receptor favoring the accommodation of the ligand in the alternative binding site.

Moreover, in the past couple of decades, rapid signaling through 7-transmembrane GPCR receptors, including the androgen receptor ZIP9 and GPER1 has been discovered (Berg et al., 2014; Carmeci et al., 1997; Revankar et al., 2005; Thomas et al., 2014). The role of GPCR receptors are well described in the gonads of both, males and females – apoptosis, spermatogenesis, signaling in Sertoli cells in case of ZIP9, and the proper function of Leydig cells in testes or uterus and reproduction in case of GPER1 (Berg et al., 2014; Kotula-Balak et al., 2018; Olde & Lee, 2009; Thomas et al., 2017a, 2014).

There are numerous studies describing the molecular signaling pathways of these receptors and the effects of SSHs via these receptors on the brain, body and behavior (Table 1). The results of these studies have brought new insights into the neurobehavioral effects of SSHs. On the other hand, additional questions have arisen, such as the sex-, age- and tissue-specific role of rapid, non-classical mechanisms involving the GPCR ZIP9 and GPER1 receptors in the brain.

Table 1.

The classical and non-classical actions of SSHs through their receptors in the cytoplasm, those attached to membrane (AR, ERs) and through transmembrane GPCR receptors (ZIP9, GPER1).

| H. | R. | Type | Signaling pathway | Effect on the brain | Effect on the other body systems or on the behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Membrane-associated | PI3K/AKT; PKA, PKC; Src/p85α/PI3K; Src/Shc/ERK; Src/p85α/p110/AKT/FOXO, Bad; ERK/MAPK; Src/p85α/MAPK/Elk1/CREB (Baron et al., 2004; Duarte et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2004; Kousteni et al., 2001; Lucas-Herald et al., 2017; Sukocheva et al., 2015) | ↑ cell survival and proliferation (Liao et al., 2013) | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Membrane-associated | MAPK, AKT (171); PI3K, PKC, Ca2 influx, ERK; MD+M2/P53/Bcl2/Bax; P21/P27; GSK-3β/CyclinD1; Bad/Caspase9; NF-KB (Barone et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2017), | ↑ endothelial NO synthase activity (Lu et al., 2004)↑ glycerol release, lipolysis, induce beiging of adipocytes (Santos et al., 2018)↓cardiac reperfusion injury in endothelial cells (Menazza et al., 2017)bone growth, fracture healing (Iravani et al., 2017; Santos et al., 2018) | ||||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||

2.1.1. Intracellular/membrane-associated AR

The binding of T and DHT to nuclear AR was first described in 1968 (Bruchovsky & Wilson, 1968a, 1968b). The expression of AR was detected in various brain areas including HIP, HYP, FC, CER, amygdala and striatum (Mhaouty-Kodja, 2017; Tobiansky et al., 2018b), but also in pancreas (Díaz-Sánchez et al., 1995), prostate (Lee et al., 1995), fibroblasts (Jacobson et al., 1995) or adipose tissue (Dieudonne et al., 1998). The expression of AR was also detected in presumptive pronephros and olfactory placodes of embryos, in pineal organ anlage and retina (3–5 days post-fertilization), and in several other regions of telencephalon, preoptic area and paraventricular nucleus of HYP in adult zebrafishes (Gorelick et al., 2008). The actions via AR signaling pathways are also involved in regulation of many processes in various body systems such as cardiovascular (Ikeda et al., 2005), immune (Gubbels Bupp & Jorgensen, 2018) and hemopoietic systems, glucose and fat metabolism (Lin et al., 2005), prostate epithelial homeostasis (Zhang et al., 2016), bone healing (Komrakova et al., 2020), muscle fast-twitch and hypertrophy (Davey et al., 2017; Morton et al., 2018), and brain masculinization (Sato et al., 2004). Signaling via AR is also involved in prostate (Debes & Tindall, 2002), and breast cancer (Giovannelli et al., 2018), where it promotes the growth of the tissue. Regarding the memory, in intact male mice, the memory consolidation seemed to be protected via AR activation after infusion of aromatase inhibitor letrozole into dorsal HIP in object recognition and object placement tasks in comparison to gonadectomized male mice (Koss & Frick, 2019). The emotional memory, dependent largely on the HIP and amygdala, was tested in the orchiectomized adolescent male rats with or without T or DHT treatment by the inhibitory avoidance test. Orchiectomized rats spent significantly less time in the illuminated box after foot-shock training and had reduced AR-immunoreactivity in amygdala/hippocampal CA1 region in comparison to sham-operated males. The treatment of these male rats with both T and DHT reversed these effects which suggest that androgens enhance inhibitory avoidance memory probably by binding to AR (Islam et al., 2021).

The classical and non-classical signaling pathways via this receptor are activated through androgen hormone ligands, predominantly T and DHT (but also androstenedione, androstenediol, dehydroepiandrosterone) in the cytoplasm (Roy et al., 1999). In the classical signaling cascade, the ligand-receptor complex translocates into the nucleus, where the receptor dimerizes, binds to DNA as a transcription factor together with other proteins, and expresses target genes (Heemers & Tindall, 2007).

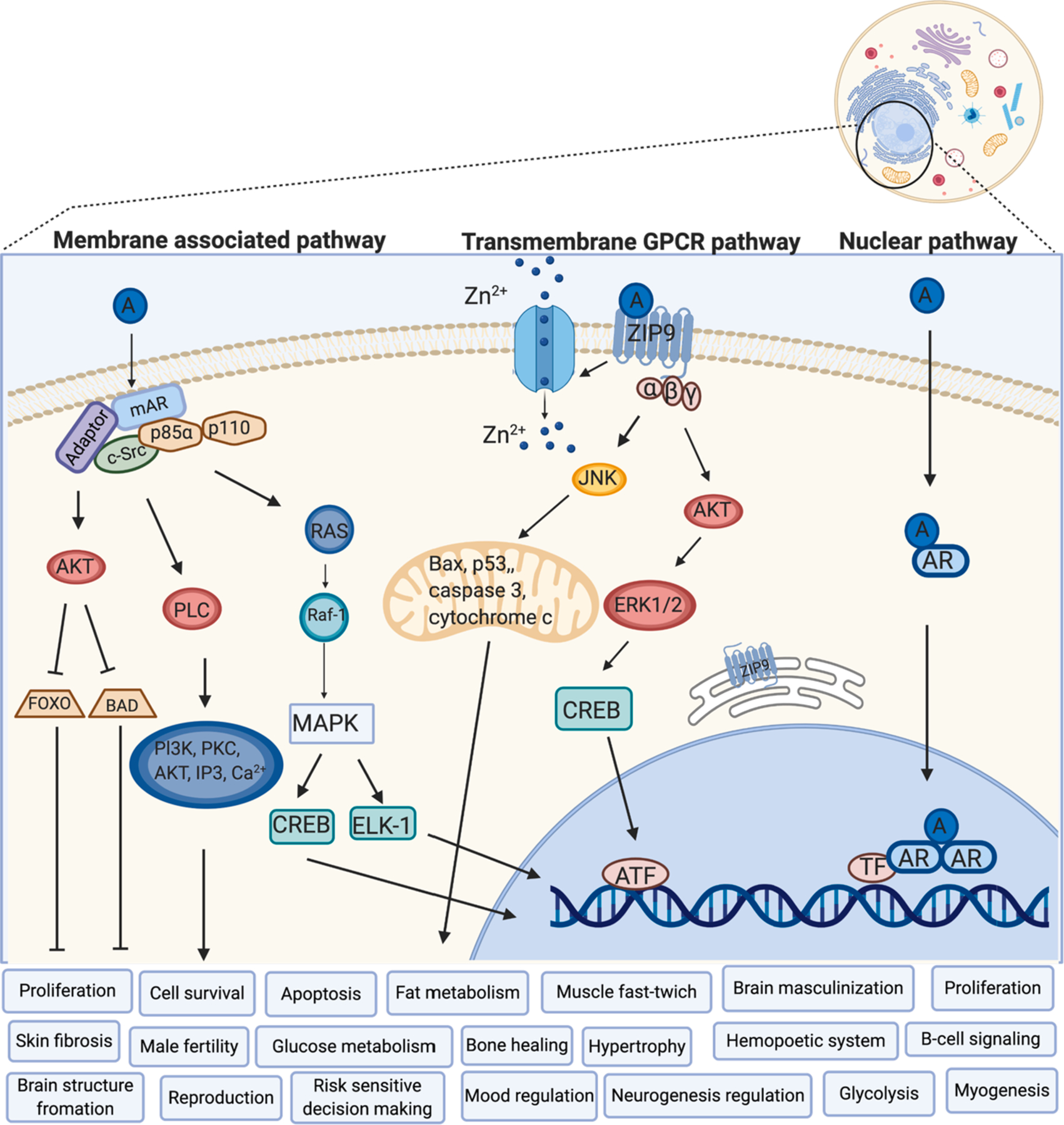

Fast, non-classical actions mediated by AR associated with the membrane in a complex with caveolin 1 have been already discovered (Heinlein & Chang, 2002; Lu et al., 2001; Lutz et al., 2003; Papakonstanti et al., 2003). These actions activate second messenger pathways including a) phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) leading to phosphorylation of AKT (known as protein kinase B) in the androgen-sensitive epithelial cells and osteoblasts (Baron et al., 2004; Kang et al., 2004) or activation of b) Src/Shc/ERK (proto-oncogene c-Src/Src homology 2 domain containing/Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase) in osteoblasts, osteocytes, embryonic fibroblasts and HeLa cells (Kousteni et al., 2001), and c) MAPK signaling cascade in androgen-sensitive human prostate adenocarcinoma LNCaP cells (Heinlein & Chang, 2002). The non-classical signaling pathway of AR could result in cell survival and cell proliferation through Src/p85α/phosphoinositide 3-kinase further activating MAPK and AKT pathways. ERK is also able to phosphorylate the intracellular AR leading to activation of transcriptional coactivators and transcription itself in the nucleus (Liao et al., 2013). Both, the classical and non-classical signaling of AR are involved in the protective mechanisms in the brains of patients suffering from Alzheimer disease as reviewed in Pike et al. (2008) (Pike et al., 2008). While activation of the classical pathway results in decreased β-amyloid plaques, activation of non-classical signaling pathway led to reduced apoptosis (Pike et al., 2008). The potential signaling mechanisms (intracellular and membrane-associated) via AR and their effects on various body systems are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Intracellular, membrane-associated and transmembrane GPCR receptors of androgens.

A – Androgen, AR – Androgen Receptor, mAR – membrane-associated Androgen Receptor, ZIP9 – Zinc transporter protein 9, Zrt- and Irt-like protein 9, c-Src – protooncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src, MAPK – Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase, ELK-1 – transcription activator, CREB – cAMP Response Element-Binding protein, AKT – protein kinase B, RAS – small GTPases, RAF-1 – proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase, FOXO – Forkhead transcription factors of the O class, BAD – Bcl2 Associated Agonist Of Cell Death, PI3K – PhospoInositide 3-Kinase, PLC – PhosphoLipase C, Bax – Bcl2 Associated X, JNK – c-Jun N-terminal kinases, ATF – Activating Transcription Factors, ERK – Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinases, TF – Transcription Factor, Zn2+ – Zinc (adapted from (Carrier et al., 2015; Leung & Sadar, 2017; Thomas et al., 2017b) and created with BioRender.com).

2.1.2. Intracellular/membrane-associated ERs

Intracellular ERs were first identified in 1958 (Jensen, 2012). Their expression was detected in various brain regions such as HIP, HYP, FC, CER, amygdala, olfactory bulb, cerebral cortex, basal forebrain, thalamus, pons Varolii, medulla oblongata, stria terminalis and periventricular preoptic nucleus (Almey et al., 2015; Foster, 2012; Pérez et al., 2003). Within HIP, the expression of ERs was reported in hippocampal pyramidal cells of Ammon’s horn and DG as soon as the 15th gestational week to adulthood. Furthermore, in adulthood, there is more ERβ than ERα in HIP and cerebral cortex (González et al., 2007). In addition, both ERs are expressed in fetal neurons, but only ERα is expressed in the Cajal-Retzius cells of marginal zones (layer I) in developing cerebral cortex and immature hippocampus, which suggest that each of the ERs may play a different role during prenatal development of HIP (González et al., 2007). Regarding other body systems, the expression of ERs was detected in the gastrointestinal tract (Lange & Meyer, 2003), kidney medulla and cortex, liver (Mizutani et al., 1994), lung, spleen, muscles, heart (Lange et al., 2001), mammary gland (Schams, 2003), ovary, uterus, testes, adrenal glands (Hutson et al., 2019) or adipose tissue (Mizutani et al., 1994).

The concentrations of ERs are the highest during the critical or sensitive periods of life (mainly prenatal/neonatal period and puberty), which supports the important role of E in the organization of hippocampal structure during its development (O’Keefe & Handa, 1990). The cellular localization of ERs was detected not only in the neurons but also in glia of the HIP (Mitterling et al., 2010). On the ultrastructural level, 50% of ERα was found in neuronal axons and axon terminals, 25% was detected in neuronal dendritic spines and remaining 25% was observed in astrocytes (Milner et al., 2001). ERβ immunoreactivity was reported in the perikarya and proximal dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal and granule cells, as well as in non-principal cells of CA3 region of HIP. At the subcellular level, ERβ was affiliated with endomembranes, mitochondria and plasma membranes. Its immunoreactivity was also observed in both, dendritic shafts and spines, preterminal axons and axon terminals associated with synaptic vesicles (Milner et al., 2005). Similar to the AR, ERs are intracellular receptors influencing gene expression via hormone response elements occurring within hours or days (Bagamasbad & Denver, 2011). In addition, rapid, non-classical mechanism of E action dependent on membrane ERs has been previously described (Soltysik & Czekaj, 2013). It has been shown that binding of caveolin-1 is fundamental step of ERα and ERβ joining of cell membrane and a so-called palmitoylation of the receptor is necessary for ERs localization to caveolaes (cell membrane invaginations) (Acconcia et al., 2005; Pedram et al., 2007; Schlegel et al., 1999).

ERs can be localized at the plasma membranes in association with receptor tyrosine kinases (EGFR, IGF), G-proteins, striatin or Src tyrosine kinases (Levin, 2005; Xu et al., 2017). There are currently known two isoforms of intracellular ER receptors: ERα and ERβ. Both act as homodimers (β/β, α/α), but can also create a heterodimer (α/β) (Li et al., 2004). Different combinations of these units can be activated by various ligands and, in turn, exert tissue-specific actions mediated by binding to different transcriptional coactivators and corepressor proteins, leading to either agonist or antagonist action (selective ER modulators) (Kansra et al., 2005). Various estrogens have different affinities to these ERs: 17β-estradiol (E2) has equal affinity to both, whereas estrone preferentially binds to ERα and estriol to ERβ (Zhu et al., 2006).

ERα is crucial for the physiological development and functions of many organs and systems, such as reproductive, central nervous, cardiovascular and skeletal systems (Menazza et al., 2017; Ruiz et al., 2020; Vidal et al., 1999). The stress response induced by corticosterone can be modulated by the activation of ERα in the brain, ovary and uterus (Niranjan & Srivastava, 2019). ERα signaling has a pivotal role in the regulation of metabolic processes as it enhances insulin resistance, energy metabolism and mitochondrial function in an ovariectomized mouse model of metabolic syndrome (Hamilton et al., 2016). Obesity, specifically fat accumulation, can be prevented through the activation of ERα, which leads to enhancement of the energy expenditure (Arao et al., 2018). Moreover, the importance of ERα in regulation of obesity has been shown in female ERα knockout mice displaying worsened insulin resistance and higher adiposity, and in turn, enlarged size of early atherosclerotic lesions. Thus, ERα signaling could serve as a control point of atherosclerosis in females, because it can promote HDL function, liver cholesterol uptake and whole-body cholesterol removal. Moreover, the signaling cascade of ERα can protect females against the development of atherosclerosis (Zhu et al., 2018). In a mouse model of obesity, the features of metabolic syndrome, such as adiposity, plasma triglycerides, and oxidative stress, were reduced following administration of the grape seed extract enriched in the flavan-3-ols procyanidin dimers (the most effective red wine polyphenol on the endothelium) partially via ERα (Leonetti et al., 2018). Regarding the learning and memory, administration of the ERα selective agonist PPT (propyl pyrazole triol) to ovariectomized mice result in failure to learn the socially acquired preference of food. This outcome suggests, that ERα signaling could be impairing the memory for the socially acquired food preference (Clipperton et al., 2008).

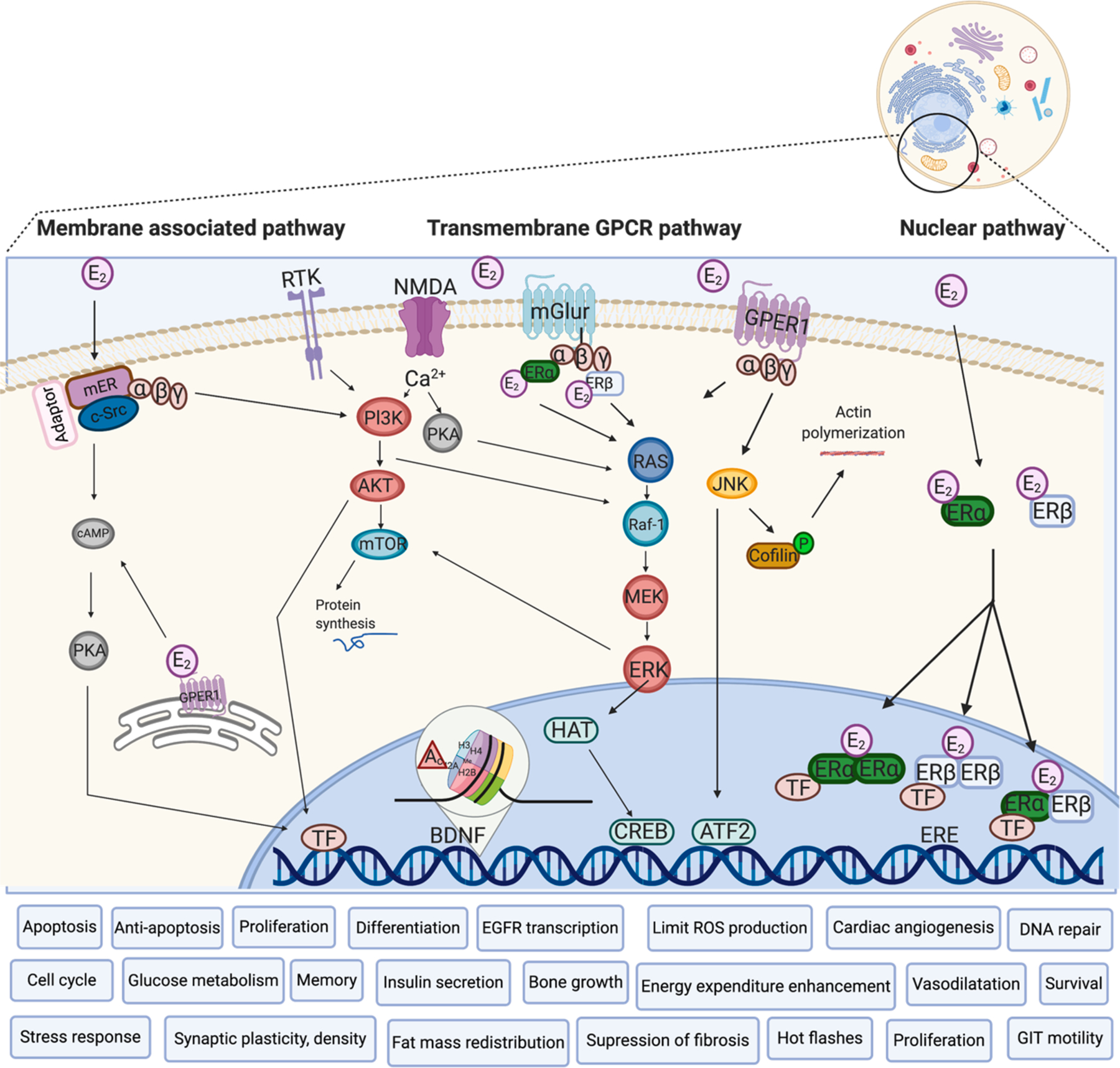

As well as AR, ERα can activate the non-classical, rapid signaling cascade through its association with the cell plasma membrane. This signaling, together with the caveolin-binding protein striatin, activates MAPK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt kinase in the vascular endothelial cells leading to higher activity of endothelial NO synthase (Lu et al., 2004). These rapid actions can also increase glycerol release, lipolysis and induce beiging of adipocytes (Santos et al., 2018). In addition, reduction of cardiac ischemia reperfusion injury in endothelial cells of ovariectomized mice was observed following an estrogen-dendrimer conjugate treatment, which selectively activates non-classical ERα, in comparison to control mice (Menazza et al., 2017). Moreover, membrane-associated ERα signaling has an important role in bone growth (Iravani et al., 2017) and in vibration-induced effects of bone fracture healing (Santos et al., 2018). ERs rapidly affect neural plasticity (within 1 h), in a rapid learning experiment, the ovariectomized mice were tested within 40 min after ERα agonist PPT or ERβ agonist DPN (diarylpropionitrile) administration for social recognition, object recognition, or object placement learning. Results from this experiment showed that PPT administration improved social recognition, promoted object recognition and placement, and increased dendritic spine density in the stratum radiatum and lacunosum- molecular, which suggest that rapid E mediated learning enhancements may predominantly be mediated via ERα (Phan et al., 2011).

ERβ is important for migration of neurons and glial cells, or neural differentiation of embryonic stem cells, especially for differentiation of midbrain neurons (Varshney et al., 2017). Furthermore, dysregulation of ERβ signaling could have a negative effect on development of neurological disorders, such as dyslexia, through DNA de-methylation actions (Varshney & Nalvarte, 2017). ERβ also mediates calcium-induced mitochondrial permeability transition pore caused by ischemic brain injury through cyclophilin D and ATPase interaction (Burstein et al., 2018). In cancer research, ERβ seems to be a potential therapeutic target for colorectal or breast cancer, because its activation represses oncogenesis and metastasis (Austin et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2016). ERβ increases protein p53 signaling, leading to DNA repair (Weige et al., 2012), apoptosis and reduced proliferation (Hsu et al., 2006). In addition, the activation of ERβ signaling supports innate immunity resulting in the suppression of the cancer metastasis in lungs (Zhao et al., 2018). Concerning the other roles of this receptor, ERβ is involved in fat metabolism, where its activation induces fat mass redistribution and regulates hepatic triglyceride composition, which leads to tissue-specific and sex-dependent response to metabolic adaptation to overfeeding (González-Granillo et al., 2020). With reference to social learning, the ovariectomized mice treated with the ERβ selective agonist WAY-200070 (benzoxazole) showed a 2-fold prolonged preference for food eaten by their demonstrator. The results after the ERβ selective agonist treatment suggest that the enhancing effects on social learning may be due to the action of ERβ on submissive behavior (Clipperton et al., 2008). Another selective ERβ agonist - ISP358–2 (A-C estrogen), seems to be a potent candidate for enhancing memory consolidation in postmenopausal women (Hanson et al., 2018).

Concerning the non-classical effects of ERβ, in cardiovascular system, especially in cardiomyocytes, ERβ activation stimulates PI3 kinase which increase the modulatory calcineurin-interacting protein 1 gene and protein expression, which subsequently inhibits calcineurin activity increased by angiotensin II and prevent the hypertrophy (Pedram et al., 2008). The classical effects of ERβ are also involved, where the transcription of the natriuretic peptide genes (ANP, BNP) are stimulated, whose as a proteins inhibit hypertrophy (activated by angiotensin II) via ERK signaling (Pedram et al., 2008). ERβ signaling also reverts pre-existing severe heart failure by stimulation of cardiac angiogenesis, suppression of fibrosis, and restoration of hemodynamic parameters. It has also been reported that ERβ membrane-associated receptors can mediate the reward circuitry in the brain and affect motivated behavior in females (Iorga et al., 2018). In older women, the period of the menopause is known not only for decline in cognitive function and impaired memory, but also for so called “hot flashes” that can be modified through ERβ activation. Administration of the selective agonist of ERβ - EGX358, reduced the senktide-mediated increase in tail skin temperature and enhanced memory in the object recognition and object placement tasks in ovariectomized mice. Thus, this ERβ agonist seems to be a promising in research of drugs for reducing menopause-related hot flashes or memory dysfunction (Fleischer et al., 2020). The possible signaling pathways of intracellular and membrane-associated ERs are summarized in Fig. 2. Besides intracellular or membrane associated receptors, E2 as well as T, binds to GPCR receptors.

Fig. 2. Intracellular, membrane-associated and transmembrane GPCR receptors of estrogens.

E2 – Estradiol, ERα – Estrogen Receptor Alpha, ERβ– Estrogen Receptor Beta, mER – membrane-associated Estrogen Receptor, GPER1 – G-Protein Coupled Estrogen Receptor 1, mGLUR – metabotropic Glutamate Receptor, NMDA – N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor, RTK – Receptor Tyrosine Kinase, ERE – Estrogen Responsive Element, c-Src – protooncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src, MEK – Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase, AKT – protein kinase B, RAS – small GTPases, RAF-1 – proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase, CREB – cAMP Response Element-Binding protein, PI3K – PhospoInositide 3-Kinase, BDNF – Brain-Derivated Neurotrophic Factor, HAT – Histon AcetylTansferase, Ac – Acetyl group, mTOR – mammalian Target of Rapamycin, cAMP – cyclic Adenosine MonoPhosphate, PKA – Protein Kinase A, JNK – c-Jun N-terminal Kinases, ATF – Activating Transcription Factors, ERK – Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinases, TF – Transcription Factor, Ca2+ – Calcium (Adapted from (Carrier et al., 2015; Frick, 2015; Kim et al., 2019a; Pedram et al., 2008; Tu & Jufri, 2013) and created with BioRender.com).

2.1.3. GPCR receptors for androgens and estrogens

The discovery of SSHs actions through GPCR transmembrane receptors is relatively new. A transmembrane AR called AR2 was discovered in the brain and gonads in 1999 (Sperry & Thomas, 1999). In 2014, was AR2 identified in Atlantic croaker ovaries as Zinc transporter protein 9/Zrt- and Irt-like protein 9 (ZIP9) 7-transmembrane G-protein coupled receptor (Berg et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2014). G-protein coupled estrogen receptor (GPER1) was discovered in 1997 in ER-positive breast carcinoma cell lines and was initially called G protein-coupled receptor 30 (Carmeci et al., 1997). In 2005, it was established that this 7-transmembrane G-protein coupled receptor has a high affinity for E2 (Revankar et al., 2005), and thus, it was renamed GPER1.

2.1.3.1. ZIP9xxx.

ZIP9, also known as zinc transporter protein, is a part of the 14-member ZIP family and is located in plasma and mitochondrial membrane, nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum (Thomas et al., 2014). ZIP proteins belong to the solute carrier family that manage membrane transport of zinc and regulates its cytoplasm concentration. Part of the zinc transporters regulate the efflux of zinc out of the cell and into vesicles (solute carrier 30) and other zinc transporters control the influx of zinc from outside the cell and from vesicles (solute carrier 39A or ZIP 1–14) (Berg et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2014). The ZIP9 gene is mostly expressed in gonadal tissue and the brain (Berg et al., 2014). ZIP9 transmembrane receptor contains a ligand-binding groove for T which binds with high affinity to this receptor. Interestingly, there is a suggestion that monomeric ZIP9 might not represent the physiological state of its action in cells and that receptor needs to dimerize for T agonistic action (Kalyvianaki et al., 2019).

Regarding the signaling pathways, ZIP9 induces the phosphorylation of AKT and ERK through inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase, which leads to activation of B-cell receptor signaling in DT-40 cells (Taniguchi et al., 2013). ZIP9 can also induce the phosphorylation of ERK 1/2 and transcription factors – cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and activating transcription factor 1 (ATF1) – in Sertoli cells leading to claudin expression and tight junction formation. This ZIP9 cascade may be crucial for male fertility (Bulldan et al., 2016) because the Sertoli cells have a central role in spermatogenesis (Griswold, 1998). Upstream regulation of ZIP9 is controlled by inhibition of Notch signaling, which increases the expression of membrane ZIP9 and intracellular AR receptors as well as androgen-regulated claudin-5, claudin-11 and cAMP in mouse Sertoli cells (Kaminska et al., 2020). Epigenetics also plays a role in the regulatory effects of ZIP9, e.g. in skin, radiation-induced DNA-methylation leads to skin fibrosis via the ZIP9 and TGFβ signaling pathway (Qiu et al., 2020). Interestingly, before ZIP9 identification, it was shown that androgens can modulate zinc homeostasis in the mouse brain. Although the temporal and spatial zinc homeostasis in the brain is modulated by SSHs, the mechanisms and potential involvement of ZIP9 are still unknown (Beltramini et al., 2004).

2.1.3.2. GPER1xxx.

GPER1 is mainly localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (Revankar et al., 2005), but is also located in the plasma membrane (Filardo et al., 2007). In brain, expression of GPER1 was detected in the cortex, HYP (paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei), HIP, specific nuclei of midbrain (the pontine nuclei, locus coeruleus), trigeminal nuclei, CER (Purkinje layer) and pituitary gland (anterior, intermediate, and neural lobes). The expression was detected also in other body systems such as cardiovascular (Almey et al., 2015; Hazell et al., 2009; Meyer et al., 2012), both female and male reproductive systems (Plante et al., 2012; Sandner et al., 2014), excretory system (Hazell et al., 2009) and gastrointestinal tract (Liu et al., 2019b).

The impact of GPER1 signaling on the brain development and functions is not clear, but GPER1 is highly expressed in the nervous system, and its activation shows beneficial, cell specific effects in various brain disorders (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease) (Roque et al., 2019; Sheppard et al., 2018). It has been found that GnRH secretion in the HPG axis is modulated by GPER1 (Chimento et al., 2014). The signaling cascade through activation of GPER1 includes various non-classical actions that seem to be tissue specific. The stimulation of GPER1 activates Ca2+ release, ERK1/2, PI3K action and stimulation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) transcription in breast cancer cell lines (Filardo et al., 2000). In the dorsal HIP of female mice, GPER1 does not activate ERK1/2, but rather signals through c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) phosphorylation instead (Filardo et al., 2000). GPER1 stimulation in the hippocampus can lead to better performance in spatial working memory tasks in ovariectomized rats (Hammond et al., 2009) and can improve object and spatial memory consolidation in ovariectomized mice (Kim et al., 2016c). However, unlike ERα and ERβ, GPER does not activate ERK in the dorsal HIP nor is dorsal HIP ERK activation necessary for GPER to influence object recognition and spatial memory consolidation in ovariectomized mice (Kim et al., 2016a). Regarding the epilepsy and HIP, the reduction of seizures’ severity has been observed after GPER1 activation (Zuo et al., 2020). Moreover, higher concentrations of GPER1 in the dorsal prefrontal cortex of monkeys was associated with greater dendritic spine synapse density in this area, suggesting an important role for GPER1 in synaptic plasticity (Crimins et al., 2016).

E2 binds GPER1 with high affinity and this activation leads to ERK phosphorylation, PI3K stimulation, intracellular Ca2+ increase, and cAMP production in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line, which occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor and results in proliferation (Filardo et al., 2000). Although, GPER1 mediates proliferation in the human breast epithelial cells in normal and malignant breasts, GPER1 knockout mice do not show any overt mammary phenotype similar to ERβ knockout mice. It means that both GPER1 and ERβ operate breast tissue proliferation but only ERα signaling is crucial for breast development (Scaling et al., 2014). In males, GPER1 has a critical role in spermatogenesis, where it controls proliferation and apoptosis (Chimento et al., 2014).

GPER1 signaling seems to have plenty of more functions in different body systems. For example, it preserved degeneration of retinal ganglion cells and acute ocular hypertension through the PI3K/AKT pathway (Jiang et al., 2019). Through the AKT/mTOR/GLUT pathway, GPER1 manages glucose metabolism and insulin secretion in β-cells of rats (Bian et al., 2019b). In myenteric neurons of the gastrointestinal tract the GPER1, as well as ERs, plays a role in motility (Liu et al., 2019a). In the endothelium of blood vessels, GPER1 activation leads to vasodilatation (Meyer et al., 2012). Furthermore, GPER1 seems to be a potential therapeutic target for females after menopause suffering from salt-sensitive hypertension (Gohar et al., 2020). In cardiac cells (cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, mast cells), GPER1 signaling inhibits the gene expression of components (cyclin B1, CDK1) involved in proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts and mast cells, and prevents hypertrophic remodeling (Deschamps & Murphy, 2009; Ogola et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2012). Cardiovascular and kidney protection via GPER1 has been studied by the examination of angiotensin II-induced hypertension and oxidative stress in GPER1 knockout mice. Estrogen signaling through GPER1 suppresses the transcription of NADPH oxidase 4 by increasing cAMP, thereby limiting the production of reactive oxygen species which avoids stiffening of the arteries (Ogola et al., 2019).

Effects of GPER1 signaling in the brain and other organs are summarized in Table 1. In the next part of the review, the effects of T and E2 signaling in selected brain regions (HIP, HYP, FC, and CER) will be discussed.

3. The effect of T and E2 on brain structures

During fetal development, the brain is already being influenced by sex hormones (T, E, Progesterone) and neurons throughout the entire nervous system already have receptors for these sex hormones (Karaismailoğlu & Erdem, 2013; Miranda & Sousa, 2018; Swaab & Garcia-Falgueras, 2009). Prenatal and early postnatal SSHs exposure organizes the brain in a male-typical or female-typical pattern. These sex-typical differences in brain structures are partially results of the organizational effects of SSHs that can have long-term influence on dendritic spine remodeling, myelination, neuronal pruning, apoptosis, and/or epigenetic changes later in adulthood. SSHs have also activational effects on aforementioned changes in the brain (dendritic spine remodeling, myelination, etc.) later in life and those are dependent on hormone concentration in adulthood. The behavioral outcomes, such as copulation, spatial abilities or memory, are the consequences of both organizational and activational effects of SSHs (Vigil et al., 2016). The other important factors that regulate the sex-specific action of T and E2 are the enzymes converting T to E2 (aromatase) or DHT (5α-reductase). The dissimilarities in concentrations of androgens, estrogens, aromatase, and 5α-reductase, as well as in expression of SSH receptors (AR, ERs, ZIP9, GPER1) in specific areas of the brain contribute to behavioral heterogeneity between males and females (Colciago et al., 2005; Roselli et al., 1985). The role of androgens and estrogens in selected brain regions related to behavior, including the HIP, HYP, FC, and CER, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The role of T and E2 in HIP, HYP, FC, and CER, brain regions related to cognition – experimental studies.

| Hippocampus | Hypothalamus | Frontal cortex | Cerebellum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone – effect on brain structures |

|

|

|

|

| Testosterone – effect on behavior |

|

|

|

|

| Estradiol–effect on brain structures |

|

|

|

|

| Estradiol – effect on behavior |

|

|

|

|

3.1. T and E2 in hippocampus

Androgens influence the structural development of the HIP by increasing and maintaining spine synaptic density in both males and females (Leranth et al., 2004, 2003; MacLusky et al., 2006). In male and female rats, testosterone proprionate rescues gonadectomy-induced reductions in CA1 spine synaptic density in a manner that partially depends on afferent subcortical input from fimbria-fornix, however, some of the effects are still present after fimbria-fornix transection (Kovacs et al., 2003). Moreover, T, as well as E2, increases cell density by stimulating neuronal cell proliferation in the HIP (Smeeth et al., 2020). As well as in early development and in puberty, neurogenesis provoked by T (or DHT) can occur during adulthood in both sexes (Okamoto et al., 2012; Spritzer & Roy, 2020). However, there are sex differences in early development of the HIP, where cell proliferation during the first postnatal week is approximately 2-times higher in male compared to female rodents (Bowers et al., 2010). Moreover, neonatal male rats have a significantly higher number of cells in the HIP than female rats (Zhang et al., 2008). T can also increase synaptic density in the dentate gyrus and promote neurogenesis in HIP of male, but not female, mice (Fattoretti et al., 2019).

In males, synaptic plasticity in CA1 pyramidal neurons is affected by androgens through AR (Islam et al., 2020). Furthermore, the activation of AR-dependent signaling in the dentate gyrus increases survival of adult-born neurons in male rats (Hamson et al., 2013). In another experiment, the replacement of T in gonadectomized male rats alleviated impaired memory caused by a reduction of AR-immunoreactive neurons in the male HIP (Moghadami et al., 2016). In hippocampal primary neuron cultures, T treatment rapidly increased spine density through non-classical cascades such as increased expression of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and CREB, but not the p38 and JNK (Guo et al., 2020). In addition, T-stimulated synaptic plasticity in the HIP could be mediated through brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Atwi et al., 2014). Concerning clinical studies, in middle-aged males with higher cortisol concentrations, plasma T concentrations were positively associated with hippocampal volume and memory performance (episodic memory), suggesting that T also exerts neuroprotective effects in men (Panizzon et al., 2018). Based on these studies, T seems to be important for many hippocampal functions and deserves attention as a regulator of synaptic plasticity and memory.

Regarding the actions of E2 in the HIP, dorsal hippocampal administration of E2 rapidly enhances object recognition and spatial memory consolidation through many mechanisms, including increased acetylation of histone 3 at several Bdnf promoters and lower expression of histone deacetylase proteins (Fortress et al., 2014; Tuscher et al., 2018). The activation of GPER1 by direct infusion of GPER1 agonist G1 into the dorsal HIP facilitates object recognition memory and hippocampal-dependent spatial memory in ovariectomized female mice via phosphorylation of JNK, which leads to cofilin-mediated actin polymerization and spinogenesis (Kim et al., 2019a, 2016a). The important role of ERα during the early developmental period, as in development of reproductive tissue, but also a non-reproductive role in developing brain, has been emphasized (Bondesson et al., 2015). The hippocampal ERα signaling activation stimulates glutamatergic synapse formation during development (Jelks et al., 2007). Additionally, the expression of ERα (Solum & Handa, 2001) and the colocalization of ERα and BDNF in pyramidal cells of CA3 and CA1 subregions of HIP occurs. This interaction between ERα and BDNF could modify the physiology of HIP during development (Solum & Handa, 2002). Concerning ERα-mediated gene transcription in the nucleus, ERβ seems to be a negative regulator of this action (Bean et al., 2014). On the other hand, studies of long-term treatment with an ERβ agonist (diarylpropionitrile) have shown that ERβ signaling contributes to regulation of neurogenesis, neuro-modulation and neuroprotection in the hippocampal formation of ovariectomized middle-aged rats (Sárvári et al., 2016).

3.2. T and E2 in hypothalamus

The most important role of the HYP is linking the nervous system to the endocrine system through the anterior (adenohypophysis) and posterior (neurohypophysis) parts of the pituitary gland (hypothalamo-pituitary axis); therefore, it supports body homeostasis by regulation of endocrine system and autonomic behavior (Namwanje & Brown, 2016; Vadakkadath Meethal & Atwood, 2005). Neurons in HYP are also necessary for various types of learning and memory (Burdakov & Peleg-Raibstein, 2020). Moreover, the HYP has an important role in regulation of metabolism, energy expenditure and gastrointestinal tract via the brain-gut-microbiota axis. There are suggestions that interaction between mental stress and gut microbiota may affect the development of hypothalamic–pituitaryadrenal axis itself (Frankiensztajn et al., 2020).

Androgens can also stimulate morphological maturation of hypothalamic aromatase-immunoreactive neurons in mouse embryos and, therefore, may influence the synaptic plasticity and connectivity in hypothalamic aromatase-system (Beyer & Hutchison, 1997). It has been shown that aromatase activity in male HYP neurons is similar to that of females, but that males have a higher percentage of neurons expressing aromatase (Beyer et al., 1994). In rats, T, but also the nonsteroidal antiandrogen (flutamide), administered both prenatally and postnatally affected the development of sexually dimorphic nuclei in HYP by increasing cell volume and length (Lund et al., 2000). The T-mediated regulation of the expression of AR, ERs and aromatase in the HYP is age dependent. In adolescence, the corticosterone release is regulated mostly by conversion of T to E2, while in adulthood greater conversion of T to DHT occurs in male rats (Green et al., 2019).

Sex chromosomes (especially XY) manage early development of HYP neurons. This management involves the sex specific neuritogenesis and regulation of the process of neuritogenic factor neurogenin 3 expression stimulated by ERα signaling in the HYP (Cisternas et al., 2020). It was also shown that neonatal E administration can modify the synapse formation of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (Arai & Matsumoto, 1978).

E2 promotes many actions in the HYP. For example, it increases the expression of glial cell neurotrophic factor in hypothalamic neurons, but not in astrocytes, through non-classical E action (calcium, cAMP/PKA) (Ivanova et al., 2002). E2 also stimulates caspase-dependent cell death in the developing HYP and regulates tyrosine hydroxylase-labelled dopaminergic neurons in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus of the HYP, in which intracellular hormone receptors are abundant (Waters & Simerly, 2009). Moreover, neonatal administration of E2 can elevate the number of axodendritic synapses in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (Matsumoto & Arai, 1976). In addition, E2 stimulates axogenesis in male HYP via ERK1/2 and ryanodine receptors-dependent intracellular calcium rise (Cabrera Zapata et al., 2019).

3.3. T and E2 in frontal cortex

Androgens seem to be critical modulators of executive functions in the mesocorticolimbic area, including the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Tobiansky et al., 2018a). Early exposure (postnatal day 10) to T leads to hyperactivity, higher impulsivity and attention deficit behavior in individuals who already have the genetic predisposition for these behaviors (King et al., 2000). During puberty, there is a shift of emotional control from the pulvinar nucleus of the thalamus and amygdala to the anterior PFC caused by T (Tyborowska et al., 2016). T can also affect emotions in the PFC of psychopathic offenders, where patients, especially those with high endogenous T concentration, show less emotional control-related anterior PFC activity and anterior PFC-amygdala coupling during the tests of emotional actions (Volman et al., 2016). High concentrations of T have been associated with lower cortical density in the left hemisphere, especially in the PFC of prepubertal boys, and these effects are associated with higher aggression and lower executive function. In addition, Nguyen et al. (2016) have found that T-specific modulation of the covariance between the amygdala and medial PFC could influence and predict aggressive behavior from childhood to adulthood (Nguyen et al., 2016). Moreover, elevated concentrations of T are associated with increased risk-taking in both genders, independent of age. More risk-taking is associated with a smaller orbitofrontal cortex in males and larger orbitofrontal cortex in females (Peper et al., 2013).

Unlike higher concentration of T, DHEA is associated with a prepubertal increase in neuron density in various cortical regions, which can positively facilitate cortical functions such as attention and working memory (Nguyen, 2018). Male anabolic–androgenic steroid users have thinner PFC areas involved in inhibitory control and emotional regulation (Hauger et al., 2019). Furthermore, long-term anabolic–androgenic steroid use results in executive dysfunction, including ADHD symptoms or psychological distress (Hauger et al., 2019), and also anxiety, depression, aggressive or antisocial behavior (Kashkin & Kleber, 1989).

The early expression of ERs and GPER1 was detected in the dorsal FC, ventral FC and the HIP during the developmental period spanning embryonic to late prenatal (Denley et al., 2018). Moreover, prenatal E2 modulates the development of catecholamine activity during neonatal period in male FC (Stewart & Rajabi, 1994). Puberty presents another sensitive period in brain development. The organizational effects of E2 and progesterone promote the maturation and increase of inhibitory neurotransmission in FC in pubertal females (males not studied here) (Piekarski et al., 2017). Moreover, Chung et al. (2019) have found age-dependent association between E2 concentrations and emotional activity in dorsolateral PFC, where adolescents with higher E2 concentrations showed positive reconsideration of negative emotions (Chung et al., 2019). In adults, the medial PFC together with the dorsal HIP is responsible and critical for object memory and spatial memory consolidation mediated by E2 (Tuscher et al., 2019).

The sex dependent impact on cognitive and synaptic function may be attributed to the fact that females PFC contain higher concentrations of aromatase than males. Higher E concentration in the PFC protects females against harmful effects of repeated stress in comparison to males (Yuen et al., 2016). E2 concentration in FC could also affect executive function, such as working memory, organization, planning and sustained attention (Hampson, 2018; Shanmugan & Epperson, 2014). Moreover, executive functioning in the PFC depends on E2 concentrations, together not only with molecules such as dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, and acetylcholine, but also with genetic conditions, stress, early life experiences and lifestyle choices (Shanmugan & Epperson, 2014).

3.4. T and E2 in cerebellum

In the CER, Purkinje cells have been identified as the main site of neurosteroid synthesis in the cerebellum of most vertebrates (Tsutsui, 2012). Moreover, the expression of AR in Purkinje neurons has been found, and the AR concentration can be modified by systemic T, through alteration of AR in specific regions, and by sexual behavior-induced reductions of AR in the posterior vermis (Perez-Pouchoulen et al., 2016b). The density of AR is also altered in the posterior CER after prenatal administration of valproic acid, which influenced the development of CER in both males and females age-dependently (Perez-Pouchoulen et al., 2016a).

It has been also reported that the volume of the CER negatively correlates with neurotic personality traits in adolescents and young adults, where higher endogenous T concentration was related to thicker CER gray matter volume and lower neuroticism score (Schutter et al., 2017). T seems to have protective effects on cerebellar neurons. For example, T treatment can reverse the age-related increase in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in the male CER (Day et al., 1998). Moreover, T displays protective effect on CER granule cells against the oxidative stress through the AR (Ahlbom et al., 2001). Regarding neurodegenerative disorders, T seems to be an appropriate biomarker of spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 progression, where 35% reduction of T concentration in male patients was detected (Almaguer-Mederos et al., 2020).

The most potent estrogen, E2, has a higher impact on the developing brain (dendritic spinogenesis, synapse formation, cell proliferation and apoptosis, neuronal differentiation) in comparison to adulthood (McCarthy, 2008). At the second hour of life, concentrations of E2 are higher in the FC, HYP, and preoptic area (but not in the CER, HIP and brainstem) of male rats, and highest in the female rat HIP in comparison to other brain regions of female rats. During the first PND, the concentrations of E2 decreased in the majority of brain regions and the only sex difference remained in its hypothalamic concentrations (Amateau et al., 2004).

ERβ signaling is involved in regulation of cell growth during cell differentiation in the developing CER of male and female rat pups (Jakab et al., 2001). Moreover, early childhood inflammation in the CER supports synthesis of E2 during sensitive periods (windows), which begin at about 1 year of age (Wright et al., 2019). During this sensitive period, the synthesis of E2 plays a crucial role in cerebellar Purkinje cells. This process can be disrupted by inflammation with long-term consequences, but has been observed only in males (Hoffman et al., 2016). Furthermore, endogenous E2 has been shown to affect microglial phagocytosis during the sensitive window of postnatal development of the CER (Perez-Pouchoulen et al., 2019). E2 also regulates the neurotransmission of parallel fibers to Purkinje cells in the CER (Hedges et al., 2018). E2 is expressed in cerebellar granule cells (Belcher, 1999) and has a trophic effects on these cells in both, males and females (Montelli et al., 2017). In the experiment with chicken cerebellar granule neurons, E2 can protect these granule cells against glutamate-induced toxicity both, acutely and long-term, depending on E2 concentrations (Sørvik & Paulsen, 2017). The E2 can also modulate motor memory formation in the adult male CER (Dieni et al., 2018). De novo synthesized E2 modulates CER functions through cerebellar neurotransmission and CER-dependent learning (Dieni et al., 2020). Furthermore, the improvement of cerebellar memory by E2 is mediated through ERβ (Andreescu et al., 2007).

4. Conclusions

SSHs are crucial for the proper development and function of the body in both, males and females. The research regarding the effect of SSHs on different organs and body systems, especially the brain, is moving forward very quickly, and it is important to stay abreast of the latest developments. The present review summarizes the latest information on the effects of SSHs (e.g. T and E2) via their classical or non-classical pathways at functional, cellular, and tissue levels, with the main focus on brain regions involved in cognition, including the HIP, HYP, FC and CER. The role of SSHs in modulation of behavior in both humans and laboratory animals is described. SSHs are involved in regulation of many body systems such as reproductive, immune, muscular, cardiovascular, skeletal and neural. SSHs affect these systems differently via different receptors. Although the actions of intracellular AR are central for example for bone healing, glucose and fat metabolism and β-amyloid plaque reduction, the role of membrane-associated AR is pivotal in process of neuronal apoptosis, cell survival and cell proliferation. ERα plays an important role in energy metabolism, insulin resistance, fat accumulation or atherosclerosis. On the other hand, the fast, non-classical actions of ERα result in endothelial NO activation, lipolysis, bone growth and beiging of adipocytes. Intracellular ERβ is involved in neural differentiation and in oncogenesis and metastasis suppression, whereas non-classical ERβ signaling can reverse pre-existing heart failure or inhibit hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes. Concerning transmembrane GPCR receptors, ZIP9 is crucial for male fertility, spermatogenesis, or apoptosis, whereas GPER1 is responsible for proper functioning of gonads in both males and females.

Regarding the effects of T or E2 on HIP, HYP, FC and CER, activation of the appropriate receptor triggers changes in both brain structures and behavior. For example, T increases synaptic spine density and neurogenesis in HIP, and increases synaptic plasticity and connectivity. In addition, it modulates the morphological maturation of HYP, cortical density in the FC and increases the gray matter volume in the CER. In addition, T improves working and spatial or episodic memory (HIP), increases male sexual or aggressive behavior (HYP), regulates executive functions and control of emotions (FC), and decreases neuroticism and regulation of male sexual behavior (CER). E2 increases glutaminergic synapse formation and neurogenesis in HIP, modulates synapse formation, increases axodendritic synapses and axogenesis in HYP, and regulates neurotransmission in the FC and cell growth in the CER. E2 also improves object recognition and spatial memory consolidation (HIP, FC), controls aggressive behavior and anorectic actions in females (HYP), and regulates modulates motor memory formation (CER).

Both classical and non-classical actions of T and E2 in the brain confirm the importance of these SSHs in regulation of structural changes in the brain with an impact on behavior and cognitive function. Plenty of studies have been published describing the molecular signaling pathways of SSHs receptors and their effects on the brain, body systems and behavior. The results of these studies have brought new insights into the neurobehavioral effects of T and E2. However, additional questions have arisen, such as the sex-, age- and tissue-specific role of rapid, non-classical mechanisms involving the GPCR ZIP9 and GPER1 receptors, mainly the brain. The answers to these questions will provide a more complete picture of how SSHs regulate the functional of neural and non-neural systems.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Grant Agency of Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic VEGA 1/0635/20, as well as National Institutes of Health (USA) grants R01MH107886, 2R15GM118304-02, and 1F31MH118822-01A1, and National Scholarship Programme of Slovak Republic, scholarship of Ľudmila Sedlárová – Rabanová, and scholarship “Hlavička” from SPP foundation. Institutional support was provided by PROGRES Q35/LF1/2 project by Charles University. We would like to thank native English speakers - Alyssa L. Lovely and Thomas T. Lovely - for the English language proofread.

References

- Acconcia F, Ascenzi P, Bocedi A, Spisni E, Tomasi V, Trentalance A, Visca P, Marino M, 2005. Palmitoylation-dependent estrogen receptor alpha membrane localization: regulation by 17beta-estradiol. Mol. Biol. Cell 1. 10.1091/mbc.e04-07-0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlbom E, Prins GS, Ceccatelli S, 2001. Testosterone protects cerebellar granule cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death through a receptor mediated mechanism. Brain Res 2 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)03155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almaguer-Mederos LE, Aguilera-Rodríguez R, Almaguer-Gotay D, Hechavarría-Barzaga K, Álvarez-Sosa A, Chapman-Rodríguez Y, Silva-Ricardo Y, Gonźalez-Zaldivar Y, Vázquez-Mojena Y, Cuello-Almarales D, Rodríguez-Estupiñán A, 2020. Testosterone levels are decreased and associated with disease duration in male spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 patients. The Cerebellum 4 10.1007/s12311-020-01134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almey A, Milner TA, Brake WG, 2015. Estrogen receptors in the central nervous system and their implication for dopamine-dependent cognition in females. Horm Behav 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amateau SK, Alt JJ, Stamps CL, McCarthy MM, 2004. Brain estradiol content in newborn rats: sex differences, regional heterogeneity, and possible de novo synthesis by the female telencephalon. Endocrinology 6. 10.1210/en.2003-1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreescu CE, Milojkovic BA, Haasdijk ED, Kramer P, De Jong FH, Krust A, De Zeeuw CI, De Jeu MT, 2007. Estradiol improves cerebellar memory formation by activating estrogen receptor β. J. Neurosci 40, doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai Y, Matsumoto A, 1978. Synapse formation of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus during post-natal development in the female rat and its modification by neonatal estrogen treatment. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1 10.1016/0306-4530(78)90039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arao Y, Hamilton KJ, Lierz SL, Korach KS, 2018. N-terminal transactivation function, AF-1, of estrogen receptor alpha controls obesity through enhancement of energy expenditure. Mol Metab 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argente J, Chowen-Breed JA, Steiner RA, Clifton DK, 1990. Somatostatin messenger RNA in hypothalamic neurons is increased by testosterone through activation of androgen receptors and not by aromatization to estradiol. Neuroendocrinology 4. 10.1159/000125618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwi S, McMahon D, Scharfman H, MacLusky NJ, 2014. Androgen modulation of hippocampal structure and function. The Neuroscientist 1 10.1177/1073858414558065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin D, Hamilton N, Elshimali Y, Pietras R, Wu Y, Vadgama J, 2018. Estrogen receptor-beta is a potential target for triple negative breast cancer treatment. Oncotarget 74 10.18632/oncotarget.26089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baez-Jurado E, Rincón-Benavides MA, Hidalgo-Lanussa O, Guio-Vega G, Ashraf GM, Sahebkar A, Echeverria V, Garcia-Segura LM, Barreto GE, 2019. Molecular mechanisms involved in the protective actions of selective estrogen receptor modulators in brain cells. Front. Neuroendocrinol 10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagamasbad P, Denver RJ, 2011. Mechanisms and significance of nuclear receptor auto- and cross-regulation. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol 1 10.1016/j.ygcen.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bálint M, Jeszenői N, Horváth I, Ábrahám IM, Hetényi C, 2017. Dynamic changes in binding interaction networks of sex steroids establish their non-classical effects. Sci. Rep 1 10.1038/s41598-017-14840-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron S, Manin M, Beaudoin C, Leotoing L, Communal Y, Veyssiere G, Morel L, 2004. Androgen receptor mediates non-genomic activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase in androgen-sensitive epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem 15 10.1074/jbc.M306143200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone I, Brusco L, Fuqua SAW, 2010. Estrogen receptor mutations and changes in downstream gene expression and signaling. Clin. Can. Res.: Off. J. Am. Assoc. Can. Res 10 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumler E, Strickland L, Privitera L, 2019. Molecular Underpinnings of Estradiol-Mediated Sexual Dimorphism of Synaptic Plasticity in the Hippocampus of Rodents. J Neurosci 12 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2894-18.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean LA, Ianov L, Foster TC, 2014. Estrogen receptors, the hippocampus, and memory. The Neuroscientist 5, doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher SM, 1999. Regulated expression of estrogen receptor α and β mRNA in granule cells during development of the rat cerebellum. Dev. Brain Res 1 10.1016/S0165-3806(99)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsham DD, Evangelou A, Roy D, Duc VL, Brown TJ, 1998. Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) gene expression by 5alpha-dihydrotestosterone in GnRH-secreting GT1–7 hypothalamic neurons. Endocrinology 3. 10.1210/endo.139.3.5846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsham DD, Lovejoy DA, 2005. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone: gene evolution, expression, and regulation. Vitam Horm 10.1016/S0083-6729(05)71003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltramini M, Zambenedetti P, Wittkowski W, Zatta P, 2004. Effects of steroid hormones on the Zn, Cu and MTI/II levels in the mouse brain. Brain Res 1 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg AH, Rice CD, Rahman MS, Dong J, Thomas P, 2014. Identification and characterization of membrane androgen receptors in the ZIP9 zinc transporter subfamily: I. Discovery in female atlantic croaker and evidence ZIP9 mediates testosterone-induced apoptosis of ovarian follicle cells. Endocrinology 11. 10.1210/en.2014-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermond B, Mos J, Meelis W, van der Poel AM, Kruk MR, 1982. Aggression induced by stimulation of the hypothalamus: Effects of androgens. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 1 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer C, Green SJ, Hutchison JB, 1994. Androgens influence sexual differentiation of embryonic mouse hypothalamic aromatase neurons in vitro. Endocrinology 3. 10.1210/endo.135.3.8070366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer C, Hutchison JB, 1997. Androgens stimulate the morphological maturation of embryonic hypothalamic aromatase-immunoreactive neurons in the mouse. Dev. Brain Res 1 10.1016/S0165-3806(96)00170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia A, Sekhon HK, Kaur G, 2014. Sex hormones and immune dimorphism. ScientificWorldJournal 10.1155/2014/159150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian C, Bai B, Gao Q, Li S, Zhao Y, 2019a. 17beta-estradiol regulates glucose metabolism and insulin secretion in rat islet beta cells through GPER and Akt/mTOR/GLUT2 pathway. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 10.3389/fendo.2019.00531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian C, Bai B, Gao Q, Li S, Zhao Y, 2019b. 17β-estradiol regulates glucose metabolism and insulin secretion in Rat Islet β cells through GPER and Akt/mTOR/GLUT2 pathway. Front. Endocrinol 10.3389/fendo.2019.00531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondesson M, Hao R, Lin C-Y, Williams C, Gustafsson J-Å, 2015. Estrogen receptor signaling during vertebrate development. BBA 2. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourguet W, Germain P, Gronemeyer H, 2000. Nuclear receptor ligand-binding domains: three-dimensional structures, molecular interactions and pharmacological implications. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 10 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01548-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers JM, Waddell J, McCarthy M, 2010. A developmental sex difference in hippocampal neurogenesis is mediated by endogenous oestradiol. Biology of sex differences 10.1186/2042-6410-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisken C, O’Malley B, 2010. Hormone action in the mammary gland. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol 12 10.1101/cshperspect.a003178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchovsky N, Wilson JD, 1968a. The conversion of testosterone to 5-alpha-androstan-17-beta-ol-3-one by rat prostate in vivo and in vitro. J Biol Chem 8, doi. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchovsky N, Wilson JD, 1968b. The intranuclear binding of testosterone and 5-alpha-androstan-17-beta-ol-3-one by rat prostate. J Biol Chem 22, doi. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulldan A, Bartsch JW, Konrad L, Scheiner-Bobis G, 2018. ZIP9 but not the androgen receptor mediates testosterone-induced migratory activity of metastatic prostate cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 12 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulldan A, Dietze R, Shihan M, Scheiner-Bobis G, 2016. Non-classical testosterone signaling mediated through ZIP9 stimulates claudin expression and tight junction formation in Sertoli cells. Cell. Signal 8 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdakov D, Peleg-Raibstein D, 2020. The hypothalamus as a primary coordinator of memory updating. Physiol. Behav 10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.112988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein SR, Kim HJ, Fels JA, Qian L, Zhang S, Zhou P, Starkov AA, Iadecola C, Manfredi G, 2018. Estrogen receptor beta modulates permeability transition in brain mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 6 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera Zapata LE, Bollo M, Cambiasso MJ, 2019. Estradiol-Mediated Axogenesis of Hypothalamic Neurons Requires ERK1/2 and Ryanodine Receptors-Dependent Intracellular Ca(2+) Rise in Male Rats. Front. Cell. Neurosci 10.3389/fncel.2019.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M, Jialal I, 2020. Physiology. Endocrine Hormones, StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeci C, Thompson DA, Ring HZ, Francke U, Weigel RJ, 1997. Identification of a Gene (GPR30) with Homology to the G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Superfamily Associated with Estrogen Receptor Expression in Breast Cancer. Genomics 3. 10.1006/geno.1997.4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RSE, 2019. Concurrent Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Dorsal Hippocampal Activity Is Required for Estradiol-Mediated Effects on Object Memory and Spatial Memory Consolidation. eNeuro 4, doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0271-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier N, Saland SK, Duclot F, He H, Mercer R, Kabbaj M, 2015. The anxiolytic and antidepressant-like effects of testosterone and estrogen in gonadectomized male rats. Biol. Psychiatry 4. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson JA, Manolagas SC, 2015. Effects of sex steroids on bones and muscles: similarities, parallels, and putative interactions in health and disease. Bone 10.1016/j.bone.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celotti F, Negri-Cesi P, Poletti A, 1997. Steroid metabolism in the mammalian brain: 5alpha-reduction and aromatization. Brain Res. Bull 4, doi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisternas CD, Cabrera Zapata LE, Mir FR, Scerbo MJ, Arevalo MA, Garcia-Segura LM, Cambiasso MJ, 2020. Estradiol-dependent axogenesis and Ngn3 expression are determined by XY sex chromosome complement in hypothalamic neurons. Sci. Rep 1 10.1038/s41598-020-65183-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clipperton AE, Spinato JM, Chernets C, Pfaff DW, Choleris E, 2008. Differential effects of estrogen receptor alpha and beta specific agonists on social learning of food preferences in female mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 10 10.1038/sj.npp.1301625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colciago A, Celotti F, Pravettoni A, Mornati O, Martini L, Negri-Cesi P, 2005. Dimorphic expression of testosterone metabolizing enzymes in the hypothalamic area of developing rats. Dev. Brain Res 2 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke B, Hegstrom CD, Villeneuve LS, Breedlove SM, 1998. Sexual differentiation of the vertebrate brain: principles and mechanisms. Front. Neuroendocrinol 4, doi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimins JL, Wang AC-J, Yuk F, Puri R, Janssen WGM, Hara Y, Rapp PR, Morrison JH, 2016. Diverse synaptic distributions of g protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 in monkey prefrontal cortex with aging and menopause. Cereb. Cortex 3. 10.1093/cercor/bhw050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley S, 2017. Exercise, depression-anxiety disorders and sex. Hormones 171–191.28742505 [Google Scholar]

- Davey RA, Clarke MV, Russell PK, Rana K, Seto J, Roeszler KN, How JMY, Chia LY, North K, Zajac JD, 2017. Androgen action via the androgen receptor in neurons within the brain positively regulates muscle mass in male mice. Endocrinology 10. 10.1210/en.2017-00470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JR, Frank AT, O’Callaghan JP, Jones BC, Anderson JE, 1998. The effect of age and testosterone on the expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein in the rat cerebellum. Exp. Neurol 2 10.1006/exnr.1998.6801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debes JD, Tindall DJ, 2002. The role of androgens and the androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Cancer Lett 1–2 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denley MCS, Gatford NJF, Sellers KJ, Srivastava DP, 2018. Estradiol and the development of the cerebral cortex: an unexpected role? Front. Neurosci 10.3389/fnins.2018.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps AM, Murphy E, 2009. Activation of a novel estrogen receptor, GPER, is cardioprotective in male and female rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 5 10.1152/ajpheart.00283.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Sánchez V, Morimoto S, Morales A, Robles-Díaz G, Cerbón M, 1995. Androgen receptor in the rat pancreas: genetic expression and steroid regulation. Pancreas 3, doi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieni CV, Contemori S, Biscarini A, Panichi R, 2020. De Novo synthesized estradiol: a role in modulating the cerebellar function. Int. J. Mol. Sci 9 10.3390/ijms21093316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieni CV, Sullivan JA, Faralli M, Contemori S, Biscarini A, Pettorossi VE, Panichi R, 2018. 17 beta-estradiol synthesis modulates cerebellar dependent motor memory formation in adult male rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem 10.1016/j.nlm.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieudonne M, Pecquery R, Boumediene A, Leneveu M, Giudicelli Y, 1998. Androgen receptors in human preadipocytes and adipocytes: regional specificities and regulation by sex steroids. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol 6, doi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diotel N, Charlier TD, Lefebvre d’Hellencourt C, Couret D, Trudeau VL, Nicolau JC, Meilhac O, Kah O, Pellegrini E, 2018. Steroid Transport, Local Synthesis, and Signaling within the Brain: Roles in Neurogenesis, Neuroprotection, and Sexual Behaviors. Front Neurosci 10.3389/fnins.2018.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez R, Zitting M, Liu Q, Patel A, Babadjouni R, Hodis DM, Chow RH, Mack WJ, 2018. Estradiol Protects White Matter of Male C57BL6J Mice against Experimental Chronic Cerebral Hypoperfusion. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 7 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos RL, da Silva FB, Ribeiro RF Jr., Stefanon I, 2014. Sex hormones in the cardiovascular system. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2 10.1515/hmbci-2013-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte-Guterman P, Yagi S, Chow C, Galea LA, 2015. Hippocampal learning, memory, and neurogenesis: Effects of sex and estrogens across the lifespan in adults. Horm Behav 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte AC, Hrynchak M, GonÁalves I, Quintela T, and Santos C, 2016. Sex Hormone Decline and Amyloid ≤ Synthesis, Transport and Clearance in the Brain. Journal of neuroendocrinology [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans PD, 2019. Rapid signalling responses via the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor, GPER, in a hippocampal cell line. Steroids 10.1016/j.steroids.2019.108487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattoretti P, Malatesta M, Mariotti R, Zancanaro C, 2019. Testosterone administration increases synaptic density in the gyrus dentatus of old mice independently of physical exercise. Exp. Gerontol 10.1016/j.exger.2019.110664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo E, Quinn J, Pang Y, Graeber C, Shaw S, Dong J, Thomas P, 2007. Activation of the novel estrogen receptor G protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) at the plasma membrane. Endocrinology 7. 10.1210/en.2006-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Bland KI, Frackelton AR Jr., 2000. Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Mol Endocrinol 10 10.1210/mend.14.10.0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fındıklı E, Camkurt MA, Karaaslan MF, Kurutas EB, Altun H, İzci F, Fındıklı HA, Kardas S, 2016. Serum levels of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1) in drug-naive patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Res 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer AW, Schalk JC, Wetzel EA, Hanson AM, Sem DS, Donaldson WA, Frick KM, 2020. Chronic oral administration of a novel estrogen receptor beta agonist enhances memory consolidation and alleviates vasomotor symptoms in a mouse model of menopause. Alzheimer’s & Dementia S9 10.1002/alz.047645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortress AM, Kim J, Poole RL, Gould TJ, Frick KM, 2014. 17β-Estradiol regulates histone alterations associated with memory consolidation and increases Bdnf promoter acetylation in middle-aged female mice. Learning & Memory 9, doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TC, 2012. Role of estrogen receptor alpha and beta expression and signaling on cognitive function during aging. Hippocampus 4 10.1002/hipo.20935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankiensztajn LM, Elliott E, Koren O, 2020. The microbiota and the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis, implications for anxiety and stress disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 10.1016/j.conb.2019.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick KM, 2015. Molecular mechanisms underlying the memory-enhancing effects of estradiol. Horm. Behav 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick KM, Kim J, 2018. Mechanisms underlying the rapid effects of estradiol and progesterone on hippocampal memory consolidation in female rodents. Horm Behav 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick KM, Kim J, Tuscher JJ, Fortress AM, 2015. Sex steroid hormones matter for learning and memory: estrogenic regulation of hippocampal function in male and female rodents. Learn Mem 9 10.1101/lm.037267.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridolfsson HN, Roth DM, Insel PA, Patel HH, 2014. Regulation of intracellular signaling and function by caveolin. FASEB J 9 10.1096/fj.14-252320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea LAM, Roes MM, Dimech CJ, Chow C, Mahmoud R, Lieblich SE, Duarte-Guterman P, 2018. Premarin has opposing effects on spatial learning, neural activation, and serum cytokine levels in middle-aged female rats depending on reproductive history. Neurobiol Aging 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RB, Gabor R, 2003. Estrogen and cognition: applying preclinical findings to clinical perspectives. J Neurosci Res 5 10.1002/jnr.10811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannelli P, Di Donato M, Galasso G, Di Zazzo E, Bilancio A, Migliaccio A, 2018. The Androgen Receptor in Breast Cancer. Front. Endocrinol 10.3389/fendo.2018.00492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohar EY, Daugherty EM, Aceves JO, Sedaka R, Obi IE, Allan JM, Soliman RH, Jin C, De Miguel C, Lindsey SH, Pollock JS, Pollock DM, 2020. Evidence for G-Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor as a Pronatriuretic Factor. J Am Heart Assoc 10 10.1161/JAHA.119.015110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Granillo M, Savva C, Li X, Ghosh Laskar M, Angelin B, Gustafsson J-Å, Korach-André M, 2020. Selective estrogen receptor (ER)β activation provokes a redistribution of fat mass and modifies hepatic triglyceride composition in obese male mice. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 10.1016/j.mce.2019.110672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]