Abstract

Objectives

To compare the diagnostic performance of [18F]FDG PET/MRI, MRI, CT, and bone scintigraphy for the detection of bone metastases in the initial staging of primary breast cancer patients.

Material and methods

A cohort of 154 therapy-naive patients with newly diagnosed, histopathologically proven breast cancer was enrolled in this study prospectively. All patients underwent a whole-body [18F]FDG PET/MRI, computed tomography (CT) scan, and a bone scintigraphy prior to therapy. All datasets were evaluated regarding the presence of bone metastases. McNemar χ2 test was performed to compare sensitivity and specificity between the modalities.

Results

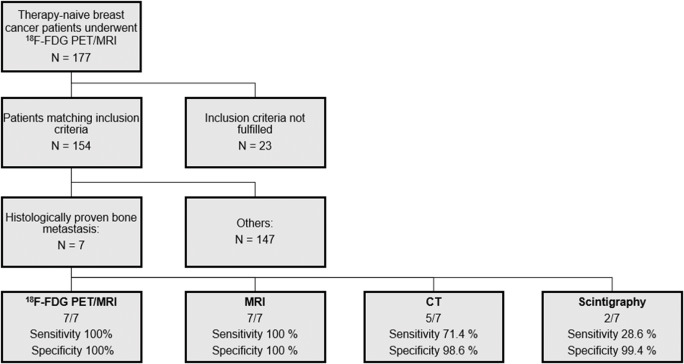

Forty-one bone metastases were present in 7/154 patients (4.5%). Both [18F]FDG PET/MRI and MRI alone were able to detect all of the patients with histopathologically proven bone metastases (sensitivity 100%; specificity 100%) and did not miss any of the 41 malignant lesions (sensitivity 100%). CT detected 5/7 patients (sensitivity 71.4%; specificity 98.6%) and 23/41 lesions (sensitivity 56.1%). Bone scintigraphy detected only 2/7 patients (sensitivity 28.6%) and 15/41 lesions (sensitivity 36.6%). Furthermore, CT and scintigraphy led to false-positive findings of bone metastases in 2 patients and in 1 patient, respectively. The sensitivity of PET/MRI and MRI alone was significantly better compared with CT (p < 0.01, difference 43.9%) and bone scintigraphy (p < 0.01, difference 63.4%).

Conclusion

[18F]FDG PET/MRI and MRI are significantly better than CT or bone scintigraphy for the detection of bone metastases in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Both CT and bone scintigraphy show a substantially limited sensitivity in detection of bone metastases.

Key Points

• [18F]FDG PET/MRI and MRI alone are significantly superior to CT and bone scintigraphy for the detection of bone metastases in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer.

• Radiation-free whole-body MRI might serve as modality of choice in detection of bone metastases in breast cancer patients.

Keywords: Multimodal imaging; Positron emission tomography; Tomography, X-ray; Radionuclide imaging; Breast neoplasms

Introduction

Breast cancer is by far the most common solid neoplasm in women worldwide and with 15% the leading cause of tumor-related deaths in women every year [1]. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, the prognosis of disease depends largely on the stage of its spread and choice of an adequate therapy. Additionally to the assessment of the extent of the primary tumor in the breast and locoregional lymph node involvement, the detection of distant metastases is crucial, since this can result in an extension of the irradiation field or an adjustment of chemotherapy and eventually in a change to a palliative therapy concept [2]. Therefore, imaging-based whole-body staging plays a pivotal role in the primary diagnostics of breast cancer patients with a high risk for the presence of distant metastases.

Despite the advances in the treatment of breast cancer, up to 30% of patients still develop distant metastases over the course of the disease [3]. Herein, the skeleton is the most frequent site of distant metastases in breast cancer patients, accounting for 50–70% of all metastases [3–7]. The affection of the bone can cause various complications such as pain, pathological fractures, spinal cord compression, and hypercalcemia, which often have a major impact on patients’ morbidity and mortality [8–10]. Early detection can help to better control the disease, minimize complications, and, as a result, achieve a better quality of life [9].

As the initial staging has become increasingly important in recent years, the diagnostic algorithm was adapted and a thoraco-abdominal CT as well as bone scintigraphy was implemented [11]. If available, a PET/CT examination can also be used in primary staging, but has been rarely applied so far due to its low availability and higher costs. Therefore, bone scintigraphy in combination with CT are widely considered to be the gold standard for the detection of bone metastases, and are also recommended as the methods of choice in current guidelines [12–14]. However, previous studies have suggested that MRI provides advantages in the detection of bone lesions when compared to bone scan and might top CT as most beneficial whole-body staging examination [9, 15]. Accordingly, MRI has been discussed as an alternative staging tool for breast cancer patients and has already been added as a method of choice in patients with neurological symptoms and signs which suggest the possibility of spinal cord compression in the latest 2018 and 2020 European Society For Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines [12, 14], but is rarely used in everyday clinical routine [16].

The application of hybrid imaging techniques has proven to be of additional benefit in this context [17–20]. However, the impact of a [18F]FDG PET/MRI examination for the detection of bone metastases in primary breast cancer patients has been scarcely investigated so far [21–23], and to the best of our knowledge, there is only a small cohort study investigating its role in comparison to conventional imaging for the detection of bone metastases in the initial staging of breast cancer [23].

Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate and compare the diagnostic value of [18F]FDG PET/MRI, MRI alone, CT, and bone scintigraphy for the detection of bone metastases in the initial staging of primary breast cancer patients.

Material and methods

Patients

This prospective study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Duisburg-Essen (study number 17-7396-BO) and Düsseldorf (study number 6040R) and performed in conformance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Written informed consent form was obtained from all patients. The present study is a sub-analysis of a prospective, super-ordinate, main study (BU3075/2-1), and the research question of the present sub-analysis is markedly different from the main study. Inclusion criteria were defined as follows: (1) newly diagnosed, treatment-naive T2 tumor or higher T-stage, or (2) newly diagnosed, treatment-naive triple-negative tumor of every size, or (3) newly diagnosed, treatment-naive tumor with molecular high risk (T1c, Ki67 > 14%, HER2-new over-expression, G3). Exclusion criteria were contraindications to MRI or MRI contrast agents, missing imaging of a modality, pregnancy or breast-feeding, and former malignancies in the last 5 years. Inclusion criteria were chosen according to clinical ESMO guidelines to set elevated pre-test probability for distant metastases [12, 14]. Between March 2018 and March 2020, a total of 177 consecutive breast cancer patients underwent a [18F]FDG PET/MRI whole-body examination prior to therapy. Twenty-three patients had to be excluded from this study, because a comparable CT examination was missing in 7 patients and a bone scintigraphy in 17 patients, mainly due to patients not attending the examination appointment or the examination was performed in other medical institutions and were not available for evaluation. This resulted in a study cohort of 154 women (mean age 53.8 ± 11.9, range 30–82 years) (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow-chart showing process of inclusion and patient-based specificity and sensitivity of each modality. of non-fulfilment of inclusion criteria are described in the text

Table 1.

Histopathological data

| N | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 154 | |

| Menopause status | Pre | 63 |

| Peri | 11 | |

| Post | 80 | |

| Family risk profile | Positive | 42 |

| Negative | 112 | |

| BRCA-1 | Positive | 4 |

| Negative | 25 | |

| Unknown | 125 | |

| BRCA-2 | Positive | 2 |

| Negative | 26 | |

| Unknown | 126 | |

| Ki 67 | Positive (> 14%) | 141 |

| Negative (< 14%) | 13 | |

| PR status | Positive | 107 |

| Negative | 47 | |

| ER status | Positive | 115 |

| Negative | 39 | |

| HER2-neu expression | 0 | 55 |

| 1+ | 50 | |

| 2+ | 23 | |

| 3+ | 26 | |

| Subtype | Luminal A | 7 |

| Luminal B | 116 | |

| HER2-enriched | 3 | |

| Basal-like | 28 | |

| Tumor grade | G1 | 6 |

| G2 | 82 | |

| G3 | 66 | |

| Histology | Ductal invasive/NST | 136 |

| Lobular invasive | 13 | |

| Mucinous invasive | 1 | |

| Mixed type | 1 |

PET/MRI

All patients underwent a [18F]FDG PET/MRI examination on an integrated 3.0-Tesla Biograph mMR scanner (Siemens Healthineers) with a mean delay of 64 ± 17 min after [18F]FDG application. Prior to intravenous injection of a body weight–adapted dosage of [18F]FDG (4 MBq/kg body weight, mean activity: 254.4 ± 43.6 MBq), blood samples were obtained to ensure blood glucose levels below 150 mg/dl. All patients received a whole-body [18F]FDG PET/MRI from head to the mid-thigh in headfirst supine position.

PET images were obtained simultaneously with the MRI data with an acquisition time of 3 min per bed position in four or five positions (axial FOV: 25.8 cm; matrix size: 344 × 344; pixel size 2.09 × 2.09 mm). An iterative 3D ordinary Poisson ordered-subset expectation maximization (3D OP-OSEM) algorithm was conducted for reconstruction of PET images utilizing 3 iterations and 21 subsets, a Gaussian filter FWHM 4.0 mm, and a scatter correction. Depending on the patient’s height, up to 6-channel flex body coils, a dedicated 16-channel head-and-neck radiofrequency (RF) coil, and a 24-channel spine array RF coil were applied for MR imaging.

For tissue attenuation correction (AC) and scatter correction, a two-point (fat, water) transaxial acquired high-resolution CAIPIRINHA (CAIPI)-accelerated T1-weighted three-dimensional (3D) Dixon-VIBE (volume interpolated breath hold examination) sequence was acquired to generate a coronal four-compartment model attenuation map (umap, background air, lungs, fat, muscle). In addition, a bone atlas correction and a truncation correction as proposed by Blumhagen et al [24] was applied. Please see Table 2 for MRI protocol parameters. The PET/MRI scanner used was not time-of-flight (TOF) capable.

Table 2.

Sequence parameters for the diagnostic MR-sequences and CT in staging of primary breast cancer patients

| CT | Region | Contrast agent | Orientation | mAs | kV | Speed (s per rotation) | Silence thickness (mm) | FOV (mm) |

| Attenuation correction | Whole-body | No | Axial | 80 | 120 | 0.75 | 4.0 | 600 |

| Diagnostic CT | Thoraco-abdominal | Yes | Axial | 210 | 120 | 0.75 | 4.0 | 350 × 459 |

| MR sequence | Region | Contrast agent | Orientation | TR (ms) | TE (ms) | Matrix size | Slice thickness (mm) | FOV (mm) |

| EPI-DWI | Whole-body | No | Axial | 11,900 | 86 | 192 × 144 | 5.0 | 380 × 285 |

| T2w HASTE | Whole-body | No | Axial | 1500 | 117 | 320 × 259 | 7.0 | 450 × 366 |

| T1w fs VIBE | Whole-body | Yes | Axial | 4.08 | 1.51 | 512 × 307 | 3.5 | 400 × 300 |

Computed tomography

Two CT scanners (Definition Edge and Definition Flash, Siemens Healthineers) were used for thoraco-abdominal multi-slice contrast-enhanced CT using automated tube current modulation and tube voltage selection (CareDose 4D and CareKV, Siemens Heathineers). CTs were acquired in portal venous phase after intravenous application of a body weight–adapted dosage of non-ionic contrast agent (Table 2). The arms of the patients were placed upwards. Accordingly, only parts of the limbs that were pictured in the FOV of all modalities were included in the evaluation.

Bone scintigraphy

Bone scintigraphy was performed according to a clinical routine protocol with planar whole-body scans using a dual-headed gamma camera equipped with low-energy high-resolution collimator (Symbia S, Siemens Healthineers). Three hours after intravenous injection of an average amount of 700 MBq of [99mTc]-labeled polyphosphonate (HDP), anterior and posterior view scans were acquired with an acquisition time of 20 to 35 min. In all cases of uncertain radionuclide accumulations on bone scan, additional target images were taken or SPECT/CT images were acquired.

Image analysis

In each patient, all examinations were performed over a 3-week period and prior to any oncologic therapy. The CT and PET/MRI datasets were analyzed separately and in random order by two radiologists experienced in hybrid and conventional imaging with a reading gap of 4 weeks to avoid recognition bias. Additionally, PET/MRI datasets and bone scintigraphy were also examined by a nuclear medicine physician. Discrepant findings were resolved by consensus decision-making in a separate session between the readers. For the evaluation of the MRI, images were separated from PET datasets. A picture archiving and communication system (Centricity; General Electric Medical Systems) and a dedicated image processing software OsiriX (Version 9.0.2, Pixmeo SARL) were used for image analysis. The readers were aware of the diagnosis but blinded to results of prior imaging.

The following criteria were applied to determine the presence of a bone metastasis in CT: a focal cortical destruction or increase of bone density, a focal bone expansion, periosteal reaction, pathological fractures, and contrast enhancement. In MRI signal intensity typical of metastasis in conventional MRI sequences, pathological contrast enhancement, diffusion restriction, pathological fractures, and bone edema were signs of malignancy. In [18F]FDG PET/MRI and on bone scan, a visually detectable focal uptake above background signal was considered a sign of malignancy. Besides lesion count, localization, and characterization (benign or malignant), the diagnostic confidence of every lesion in terms of its characterization as benign or malignant (5-point ordinal scale, 1 = very low confidence, 2 = low confidence, 3 = indeterminate confidence, 4 = high confidence, 5 = very high confidence) was assessed with each modality. The body volumes examined were chosen identically for each modality and covered the body from the thorax to mid-thighs.

Reference standard

In all 154 women, diagnosis of primary breast cancer was confirmed histopathologically. Furthermore, in all patients with suspected osseous metastasis in any of the imaging modalities, at least one osseous lesion was histologically sampled. Due to clinical and ethical standards, a histological confirmation of some malignant lesions was not available, and a surrogate reference standard was applied taking into account all follow-up imaging. In all patients with suspected metastases, CT or MRI was performed as follow-up examination (mean delay 3.8 ± 1.3 month). In total, follow-up examinations were performed in 60 women, comprising 33 thoraco-abdominal CT, 22 whole-body MRI, and 5 patients receiving both examinations (mean delay 7.4 ± 5.1 month). The remaining patients, who did not undergo follow-up imaging, have been showing no clinical signs of bone metastases. Any increase of size or a decrease of size of suspicious lesions after therapy or newly occurred cortical destruction were regarded as signs of malignancy.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 24™ (IBM). Descriptive analysis was performed, and all data are presented as mean ± standard deviation including confidence intervals (CIs). To avoid statistical errors caused by clustered data (i.e., multiple observations within the same patient), all data were analyzed calculating sensitivity and specificity on a per-patient and a per-lesion basis. In addition, CIs have been adjusted using a ratio estimator, as described by Gender et al [25]. The lesion-based analysis was performed because knowledge of the exact number and localization of metastases can have large therapeutic impact, as solitary or oligometastases can be treated selectively with radiotherapy or surgery. For the comparison of sensitivity and specificity between the modalities, a McNemar χ2 test was performed. To assess the differences regarding the diagnostic confidence, a Wilcoxon signed rank test was applied. A p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patient-based analysis

According to the reference standard, bone metastases were present in 7/154 patients of the study cohort (4.5%). Both [18F]FDG PET/MRI and MRI alone were able to detect all of these patients. No false-positive patients were described by these two modalities. This resulted in a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI: 59.0–100.0) and a specificity of 100% (CI: 97.6–100.0). CT detected 5 of the 7 patients. In one patient with a single osteolytic metastasis, this was not visible on CT and in the other patient a small osteoblastic metastasis was misinterpreted as bone marrow island. Moreover, CT revealed false-positive findings in 2 non-metastasized patients, misinterpreting degenerative or posttraumatic lesions as malignant. This resulted in a sensitivity of 71.4% (CI: 35.9–91.8) and a specificity of 98.6% (CI: 95.2–99.6). Bone scintigraphy identified 2 of the 7 patients with bone metastases and showed a false-positive finding in a non-metastasized patient, resulting in a sensitivity of 28.6% (CI: 8.2–64.1) and a specificity of 99.4% (CI: 96.4–99.9). The McNemar χ2 test yielded a not significant difference in favor of [18F]FDG PET/MRI and MRI in comparison to CT in detecting true-positive patients (100% vs. 71.4%, p = 0.094) and in specificity (100% vs. 98.6%, p = 0.15) and a significant difference in sensitivity comparing [18F]FDG PET/MRI and MRI to bone scan (100% vs. 28.6%, p < 0.001). The difference between CT and bone scan yielded no statistical significance (71.4% vs. 28.6%, p = 0.076).

Lesion-based analysis

A total of 45 bone lesions in 7 patients were included in the final evaluation, comprising 41 (91.1%) bone metastases and 4 (8.9%) benign bone lesions. One of the patients showed a diffuse infiltration of the entire axial skeleton, which was counted as 1 lesion. Twenty-three of the 41 metastases were classified as lytic, and 18 as sclerotic. Table 3 shows the localizations of all bone metastases. At least one lesion was confirmed by histopathological sampling in each patient; the remaining bone metastases were confirmed by follow-up imaging, according to the reference standard.

Table 3.

Locations of all 41 bone metastases and number of detected lesions in each modality in comparison to the reference standard (in brackets). Most metastases affected the vertebrae and the pelvic bones. Mainly osteolytic metastases were missed/misinterpreted by CT and bone scan. Note that in CT arms were positioned upward and in PET/MRI besides the body. Only parts of the limbs that are pictured in the FOV of all modalities were evaluated

| PET/MRI and MRI | CT | Bone scan | Reference standard | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lytic | Sclerotic | Lytic | Sclerotic | Lytic | Sclerotic | Histology | CT | MRI | |

| Vertebrae | 9(9) | 8(8) | 4(9) | 8(8) | 1(9) | 4(8) | 1 | 12 | 4 |

| Pelvic bones | 6(6) | 4(4) | 2(6) | 4(4) | 3(6) | 3(4) | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Ribs | 4(4) | 1(1) | 1(4) | 0(1) | 1(4) | 0(1) | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Limbs | 4(4) | 5(5) | 1(4) | 3(5) | 2(4) | 1(5) | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Total | 23(23) | 18(18) | 8(23) | 15(18) | 7(23) | 8(18) | 8 | 23 | 10 |

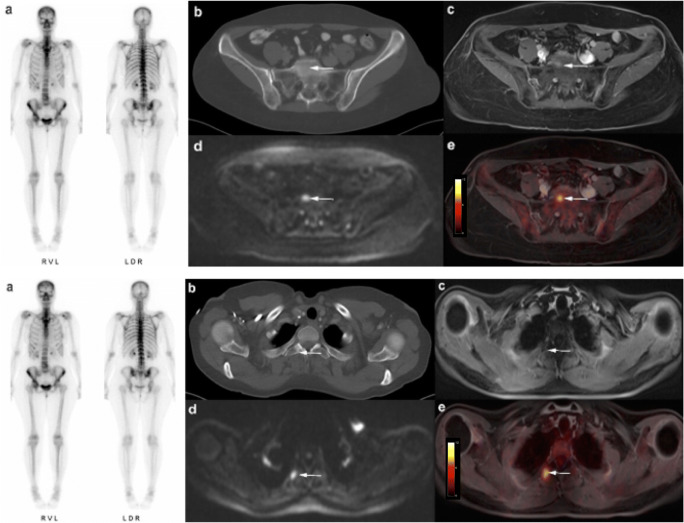

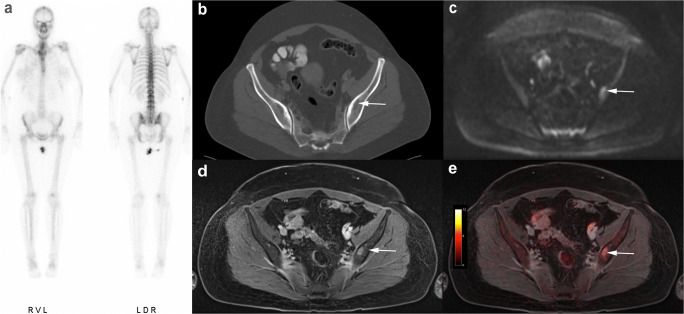

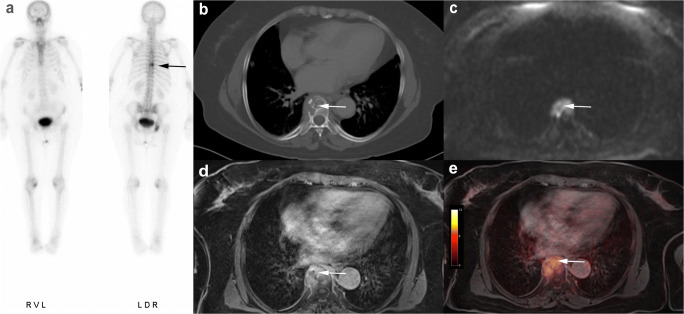

[18F]FDG PET/MRI did not miss any of the 41 malignant lesions (sensitivity 100%, CI: 79.0–100.0). All metastases showed a focal [18F]FDG uptake. There were no false-positive findings by [18F]FDG PET/MRI. MRI alone was also able to correctly identify all 41 metastases (sensitivity 100%, CI: 79.0–100.0), but misinterpreted one degenerative benign lesion as malignant. On MRI alone, the correct identification of 5 metastases was only possible through DWI, as they did not show a clear correlate on conventional morphologic MRI sequences (see Fig. 2). In comparison to that, CT detected 23 of 41 malignant bone lesions (sensitivity 56.1%, CI: 43.7–68.5; 8 lytic, 15 sclerotic). Fifteen malignant lesions were missed by CT and 3 sclerotic metastases were misinterpreted as bone islands. Especially osteolytic lesions of the bone marrow showing no signs of a tumor infestation such as cortical thinning or destruction were difficult to detect and often remained unrecognized on CT (Figs. 2, 3, and 4). Furthermore, there were 4 false-positive findings in CT, as 3 lesions in the axial skeleton and 1 lesion in a rib turned out to be degenerative or posttraumatic in histology and follow-up examination. Bone scintigraphy detected 15/41 bone metastases (sensitivity 36.6%, CI: 22.1–51.1; 7 lytic, 8 sclerotic) (Figs. 2, 3, and 4). Two of the lytic metastases detected with bone scintigraphy in one patient were not visible on CT. In addition, two posttraumatic lesions in the sternum and distal humerus in one patient were considered metastases in bone scintigraphy due to increased bone metabolism.

Fig. 2.

Fifty-eight-year-old woman with breast cancer and histologically proven bone metastases in the os sacrum and the second right rib. Clear evidence of metastatic infestation in fused [18F]FDG PET/MRI (e) and in DWI-sequences (d). In T1 fs Vibe the lesions are hard to detect (c). No signs of malignancy were seen in CT and bone scintigraphy (a, b)

Fig. 3.

Forty-eight-year-old woman with breast cancer and a single histologically confirmed osteolytic metastasis in the left iliac bone. In the absence of cortical destruction, CT and bone scintigraphy yielded false-negative results (a, b). Clear identification of metastasis in MRI alone (c, d) and in fused [18F]FDG PET/MRI (e)

Fig. 4.

Seventy-five-year-old woman with breast cancer and histologically confirmed osteolytic bone infestation in thoracic vertebral body T8. All modalities show clear evidence of metastasis: focal accumulation in bone scintigraphy (a), cortical destruction and osteolysis in CT (b), diffusion restriction and contrast enhancement in MRI (c, d), and tracer uptake in fused [18F]FDG PET/MRI (e)

The McNemar χ2 test yielded statistical significance when comparing sensitivities in lesion detection of [18F]FDG PET/MRI with CT (p < 0.01, difference 43.9%, CI: 30.7–57.1) and MRI alone with CT (p < 0.01, difference 43.9%, CI: 30.7–57.1) as well as comparing [18F]FDG PET/MRI and MRI alone with bone scintigraphy (p < 0.01, difference 63.4%, CI: 40.7–76.1). The CT showed a statistically significant superiority in comparison to bone scintigraphy (p = 0.039, difference 19.5%, CI: 0.01–0.38).

Diagnostic confidence

[18F]FDG PET/MRI showed a significantly higher overall diagnostic confidence in lesion nature ratings compared to MRI alone (4.16 ± 0.71 vs. 3.3 ± 0.65, p < 0.0001), CT (4.16 ± 0.71 vs. 3.04 ± 0.85, p < 0.0001), and bone scintigraphy (4.16 ± 0.71 vs. 3.93 ± 0.26, p = 0.0003). The difference of diagnostic confidence of MRI alone in comparison to CT did not reach statistical significance (3.3 ± 0.65 vs. 3.04 ± 0.85, p = 0.058).

Discussion

In our study, [18F]FDG PET/MRI and MRI alone both outperform CT and bone scintigraphy when assessing bone metastases in the initial staging of patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer. On a lesion-based analysis, these modalities reveal a considerable advantage especially in the detection of osteolytic metastases. [18F]FDG PET/MRI shows no differences to MRI alone in sensitivity but offers a higher diagnostic confidence in correctly rating bone metastases. Bone scintigraphy achieved significantly worse results than CT in the detection of bone metastases.

Although the spectrum of available therapeutic options for breast cancer has significantly improved in recent years, distant metastases are still detectable in approximately one-third of patients during the course of the disease [3]. Bone metastases are by far the most frequent localization, accounting for 50–70% of distant metastases in the early phase of the disease [3–5]. Hence, a reliable initial staging has become increasingly important, as this allows for an individualized therapy regimen and early detection of patients with bone metastases to reduce skeletal morbidity by adjustment of chemotherapy, use of bisphosphonates, or targeted irradiation. Accordingly, the initial staging examination has recently been amended in guidelines, now including a thoraco-abdominal CT scan and a bone scintigraphy [12, 13]. Bone scintigraphy is still widely considered to be the gold standard in the detection of bone metastases, although a large number of studies in recent years have shown advantages of MRI as well as of hybrid imaging techniques [9, 15, 19, 20].

The results of our study raise the questions, whether a default bone scintigraphy is actually necessary in the primary staging of breast cancer patients when a CT is already performed and whether these two examinations should even remain the first choice considering the preeminent performance of PET/MRI or MRI alone. There have been various studies indicating that CT is superior to bone scintigraphy in detection of breast cancer metastases [21, 26, 27], and according to the results of a study by Bristow et al [27] comparing CT and bone scintigraphy in 44 patients with bone metastases from breast cancer, the routine bone scan may not be required. One advantage of our study is the relatively large, prospectively enrolled patient cohort undergoing initial staging based on current ESMO guidelines, hence reflecting clinical routine. Our results show that only 4% of patients have bone metastases in the initial breast cancer staging, which further questions the importance of bone scintigraphy in addition to thoraco-abdominal CT, also because breast cancer patients tend to be rather young and radiation dose should be considered. Nevertheless, in a clinical setting, review of both examinations is advisable in any case, especially since CT can facilitate the differentiation of benign and malignant radionuclide accumulations detected on bone scans [26].

Several studies have reported a superiority of whole-body MRI over CT and bone scintigraphy in bone lesions [15, 28], although it is rarely used for initial staging examinations of breast cancer in current clinical routine [16]. A major advantage of MRI is the possibility to directly visualize metastatic tissue in the bone marrow. Consequently, especially osteolytic metastases could be detected earlier than with CT and usually before cortical bone destruction has occurred [29, 30]. Furthermore, the early detection of a solitary bone metastasis might offer the opportunity of a curative approach by application of a local radiation therapy. According to our results, the visualization of osteolytic bone metastases with sole medullary involvement is highly limited both with CT and bone scintigraphy. Depending on the location, osteolytic metastases are detectable by bone scintigraphy only when approximately 50% of the bone marrow is already destroyed [21, 31]. This also has an influence on the therapy decisions. The earlier the metastases are discovered, the better they can be treated. As a result, this might prevent tumor-related osteolysis or fractures and reduce pain or other comorbidities [30]. MRI offers further advantages, such as the lack of ionizing radiation, or the higher soft tissue contrast, which might be beneficial for the detection of non-osseous lesions. In our study, diffusion-weighted MR imaging (DWI) revealed multiple metastases that would otherwise have been missed; hence, it should be considered part of the imaging protocol.

The ability of hybrid imaging to detect bone metastases in different tumor entities has been investigated extensively in recent years. PET/CT has already proven to be advantageous in cancer staging in comparison to CT and bone scintigraphy [20, 32–35].

The comparison of PET/CT and MRI has yielded conflicting results so far [36, 37]. In a study by Jambor et al with 26 high risk breast cancer patients, both modalities are described to be equally suitable for the detection of bone metastases with sensitivities of 93% and 91% [37]. The introduction of fully integrated PET/MRI in 2011 has enabled simultaneous acquisition of PET and high soft-tissue contrast morphological and functional MRI. In this study, the high sensitivity in detection of bone metastases is primarily caused by the [18F]FDG PET, but the combination with MRI offers the advantage of a high anatomical resolution and functional imaging. When comparing PET/CT and PET/MRI, available data is inconsistent. While Löfgren et al [38] did not see clear advantages of either one modality in the evaluation of bone metastases, studies of Sawicki et al [35] and Catalano et al [22] postulated a superiority of PET/MRI in recurrent breast cancer attributed to the higher soft tissue contrast and added information from functional imaging such as DWI.

Additionally to the mere detection of lesions, a high diagnostic confidence, allowing for a reliable differentiation between benign and malignant lesion nature, is relevant in daily routine. Although PET/MRI and MRI alone were able to detect all malignant bone lesions, our study emphasizes the level of diagnostic confidence achieved by hybrid imaging based on the ability to visualize pathologically increased glucose metabolism of malignant lesions [39].

This study has limitations. Despite the rather large study population with primary breast cancer, the number of patients with bone metastases was small. Second, in most cases, just one biopsy site has been chosen to histologically secure bone metastasis, since a histological sampling of all detected metastases is usually not required for determining the oncologic treatment concept. Therefore, the reference standard was also based on follow-up examinations using CT and MRI. Third, an adequate determination of a lesion-based specificity was not possible, since not all initially detected benign lesions were followed up with imaging. Fourth, up to 10% of osseous metastases in patients with breast cancer are located in the distal limbs and skull [40]. In this study, only lesions that could be detected by all modalities were included in the analysis. The thoracoabdominal CT had a slightly smaller FOV than the PET/MRI as the arms were raised above the head and were partly outside the FOV, while in PET/MRI the arms were lowered beside the body. So potential areas of metastasis may be excluded in this analysis, because of the limited FOV. Regardless, an additional separate evaluation of the complete FOV of each modality was performed but no additional metastases were found.

In conclusion, both [18F]FDG PET/MRI and MRI alone have shown to be significantly superior to CT and bone scintigraphy for the detection of bone metastases in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer in our lesion-based analysis. MRI alone and [18F]FDG PET/MRI identified equivalent numbers of bone metastases. Considering the relatively low prevalence of bone metastases at initial diagnosis, the high number of patients at a relatively young age undergoing the clinical staging algorithm, and the therapeutic impact of bone metastases, radiation-free whole-body MRI might serve as modality of choice. In contrast, the use of currently recommended CT and bone scintigraphy for the detection of bone metastases seems questionable.

Abbreviations

- AC

Attenuation correction

- ADC

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- CI

Confidence interval

- CT

Computed tomography

- DWI

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- EPI

Echo-planar imaging

- ESMO

European Society For Medical Oncology

- FDG

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- FOV

Field of view

- FWHM

Full-width at half maximum

- HASTE

Half Fourier acquisition single shot turbo spin echo

- HDP

Hydroxydiphosphonate

- HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OSEM

Ordered-subset expectation maximization

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- RF

Radiofrequency

- VIBE

Volume interpolated breath-hold examination

- WHO

World Health Organization

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The study is funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), the German Research Foundation (BU3075/2-1). The funding foundation was not involved in trial design, patient recruitment, data collection, analysis, interpretation or presentation, writing or editing of the reports, or the decision to submit for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had all responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. We want to thank Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for financially promoting this research project.

Declarations

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Nils-Martin Bruckmann, MD.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Statistics and biometry

Institute of Medical Informatics, Biometry and Epidemiology, University Hospital of Essen, Germany; Prof. Andreas Stang, head of the department.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee of the University Duisburg-Essen (study number 17-7396-BO) and Düsseldorf (study number 6040R) and with the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Methodology

• prospective

• diagnostic or prognostic study

• performed at two institutions

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Nils Martin Bruckmann and Julian Kirchner contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.The Global Cancer Observatory G Breast cancer. Source: Globocan 2018. World Health Organ. 2018;876:2018–2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wockel A, Festl J, Stuber T, et al. Interdisciplinary screening, diagnosis, therapy and follow-up of breast cancer. Guideline of the DGGG and the DKG (S3-level, AWMF registry number 032/045OL, December 2017) - part 2 with recommendations for the therapy of primary, recurrent and advanced breast cancer. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2018;78:1056–1088. doi: 10.1055/a-0646-4630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkes A, Clifton K, Al-Awadhi A, et al. Characterization of bone only metastasis patients with respect to tumor subtypes. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2018;4:2. doi: 10.1038/s41523-018-0054-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman RE, Rubens RD. The clinical course of bone metastases from breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1987;55:61–66. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liede A, Jerzak KJ, Hernandez RK, Wade SW, Sun P, Narod SA. The incidence of bone metastasis after early-stage breast cancer in Canada. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;156:587–595. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3782-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brockton NT, Gill SJ, Laborge SL, et al. The breast cancer to bone (B2B) metastases research program: a multi-disciplinary investigation of bone metastases from breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:512. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung SY, Rosenzweig M, Sereika SM, Linkov F, Brufsky A, Weissfeld JL. Factors associated with mortality after breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:103–112. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9859-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hortobagyi GN, Theriault RL, Lipton A, et al. Long-term prevention of skeletal complications of metastatic breast cancer with pamidronate. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2038–2044. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.6.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu T, Cheng T, Xu W, Yan W-L, Liu J, Yang H-L. A meta-analysis of 18FDG-PET, MRI and bone scintigraphy for diagnosis of bone metastases in patients with breast cancer. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:523–531. doi: 10.1007/s00256-010-0963-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossi L, Longhitano C, Kola F, Del Grande M (2020) State of art and advances on the treatment of bone metastases from breast cancer: a concise review. Chin Clin Oncol 9:18. 10.21037/cco.2020.01.07 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Senkus E, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, et al. Primary breast cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 5):v8–v30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardoso F, Senkus E, Costa A, et al. 4th ESO-ESMO International Consensus Guidelines for Advanced Breast Cancer (ABC 4)dagger. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1634–1657. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Balassanian R, et al. Breast cancer, version 4.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:310–320. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardoso F, Paluch-Shimon S, Senkus E, et al. 5th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5) Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1623–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohlmann-Knafo S, Pickuth D, Kirschbaum M, Fenzl G. Diagnostic value of whole-body MRI and bone scintigraphy in the detection of osseous metastases in patients with breast cancer - a prospective double-blinded study at two hospital centers. RoFo. 2009;181:255–263. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1109104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hausmann D, Kern C, Schröder M, et al. Whole-body MRI in preoperative diagnostics of breast cancer-a comparison with [corrected] staging methods according to the S 3 guidelines. Rofo. 2011;183:1130–1137. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hildebrandt MG, Gerke O, Baun C, et al. [181F] fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) in suspected recurrent breast cancer: a prospective comparative study of dual-time-point FDG-PET/CT, contrast-enhanced CT, and bone scintigraphy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1889–1897. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.5185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bitencourt AGV, Andrade WP, da Cunha RR, et al. Detection of distant metastases in patients with locally advanced breast cancer: role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography and conventional imaging with computed tomography scans. Radiol Bras. 2017;50:211–215. doi: 10.1590/0100-3984.2015-0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park S, Yoon J-K, Lee SJ, Kang SY, Yim H, An Y-S. Prognostic utility of FDG PET/CT and bone scintigraphy in breast cancer patients with bone-only metastasis. Medicine (United States) 2017;96:e8985. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahn S, Heusner T, Kümmel S, et al. Comparison of FDG-PET/CT and bone scintigraphy for detection of bone metastases in breast cancer. Acta Radiol. 2011;52:1009–1014. doi: 10.1258/ar.2011.100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heindel W, Gübitz R, Vieth V, et al. The diagnostic imaging of bone metastases. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:741–747. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Catalano OA, Nicolai E, Rosen BR, et al. Comparison of CE-FDG-PET/CT with CE-FDG-PET/MR in the evaluation of osseous metastases in breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1452–1460. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonni I, Minamimoto R, Baratto L, et al. Simultaneous PET/MRI in the evaluation of breast and prostate cancer using combined Na[18F] F and [18F]FDG: a focus on skeletal lesions. Mol Imaging Biol. 2020;22:397–406. doi: 10.1007/s11307-019-01392-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumhagen JO, Ladebeck R, Fenchel M, Scheffler K. MR-based field-of-view extension in MR/PET: B0 homogenization using gradient enhancement (HUGE) Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:1047–1057. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genders TSS, Spronk S, Stijnen T, Steyerberg EW, Lesaffre E, Hunink MGM. Methods for calculating sensitivity and specificity of clustered data: a tutorial. Radiology. 2012;265:910–916. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muindi J, Coombes RC, Powles GSTJ, Khan O, Husband J. The role of computed tomography in the detection of bone metastases in breast cancer patients. Br J Radiol. 1983;56:233–236. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-56-664-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bristow AR, Agrawal A, Evans AJ, et al. Can computerised tomography replace bone scintigraphy in detecting bone metastases from breast cancer? A prospective study. Breast. 2008;17:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engelhard K, Hollenbach HP, Wohlfart K, et al. Comparison of whole-body MRI with automatic moving table technique and bone scintigraphy for screening for bone metastases in patients with breast cancer. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-1968-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avrahami E, Tadmor R, Dally O, Hadar H. Early MR demonstration of spinal metastases in patients with normal radiographs and CT and radionuclide bone scans. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989;13:598–602. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198907000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinborn M, Tiling R, Heuck A, et al. Diagnosis of bone marrow metastases with MRI. Diagnostik der metastasierung im knochenmark mittels MRT. Radiologe. 2000;40:826–834. doi: 10.1007/s001170050830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rybak LD, Rosenthal DI. Radiological imaging for the diagnosis of bone metastases. Q J Nucl Med. 2001;45:53–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hildebrandt M, Falch K, Baun C, et al. Imaging of bone metastases in suspected recurrent breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:560. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.149732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mavriopoulou E, Zampakis P, Smpiliri E, et al. Whole body bone SPET/CT can successfully replace the conventional bone scan in breast cancer patients. A prospective study of 257 patients. Hell J Nucl Med. 2018;21:125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris PG, Lynch C, Feeney JN, et al. Integrated positron emission tomography/computed tomography may render bone scintigraphy unnecessary to investigate suspected metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3154–3159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.5743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sawicki LM, Grueneisen J, Schaarschmidt BM, et al. Evaluation of 18F-FDG PET/MRI, 18F-FDG PET/CT, MRI, and CT in whole-body staging of recurrent breast cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heusner T, Gölitz P, Hamami M, et al. “One-stop-shop” staging: should we prefer FDG-PET/CT or MRI for the detection of bone metastases? Eur J Radiol. 2011;78:430–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jambor I, Kuisma A, Ramadan S, et al. Prospective evaluation of planar bone scintigraphy, SPECT, SPECT/CT, 18F-NaF PET/CT and whole body 1.5T MRI, including DWI, for the detection of bone metastases in high risk breast and prostate cancer patients: SKELETA clinical trial. Acta Oncol (Madr) 2016;55:59–67. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1027411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Löfgren J, Mortensen J, Rasmussen SH, et al. A prospective study comparing99mTc-hydroxyethylene-diphosphonate planar bone scintigraphy and whole-body SPECT/CT with18F-fluoride PET/CT and18F-fluoride PET/MRI for diagnosing bone metastases. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:1778–1785. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.189183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sawicki LM, Kirchner J, Umutlu L, et al. Comparison of 18F–FDG PET/MRI and MRI alone for whole-body staging and potential impact on therapeutic management of women with suspected recurrent pelvic cancer: a follow-up study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;45:622–629. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3881-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kakhki VRD, Anvari K, Sadeghi R, et al. Pattern and distribution of bone metastases in common malignant tumors. Nucl Med Rev. 2013;16:66–69. doi: 10.5603/NMR.2013.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]