Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to highlight both global interconnectedness and schisms across place, context and peoples. While countries such as Australia have securitised their borders in response to the global spread of disease, flows of information and collective affect continue to permeate these boundaries. Drawing on interviews with Australian healthcare workers, we examine how their experiences of the pandemic are shaped by affect and evidence ‘traveling’ across time and space. Our analysis points to the limitations of global health crisis responses that focus solely on material risk and spatial separation. Institutional responses must, we suggest, also consider the affective and discursive dimensions of health-related risk environments.

Keywords: COVID-19, Australia, Risk, Affect, Healthcare workers, Media

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has vividly reconfigured forms of global connectedness. Its spread has demanded responses at local, national and global scales (Andrews et al., 2021a), transforming socio-spatial relations (Rose-Redwood et al., 2020). For Australia, a key component of the pandemic response has been the securitisation of space, restricting movement across internal and international borders (Bissell 2021). While movements of people into and out of Australia have been severely disrupted, other forms of global connection, especially those mediated by news, social media and personal communications, have intensified. The widespread pivot to online platforms in the workplace, and in social spheres, has enabled flows of information and affect to quickly traverse international borders. In healthcare, this has meant rapid sharing (and contestation) of information and evidence, especially around diagnostics; personal protective equipment (PPE); ‘best practice’ infection control and prevention (including changing clinical guidelines); and potential treatments and vaccines (Caly et al., 2020). As scientific evidence has emerged and travelled, it has shaped policies, guidelines and treatments. At the same time, as evidence has evolved and been contested in public and professional spheres, uncertainty, fear and anger have also proliferated.

This paradox of contraction (of movement) and intensification (of informational exchange) represents a central tension in the Australian pandemic experience: while bio-securitisation measures have, to a certain extent, created spaces of managed pandemic safety, such measures do not restrict the flows of information, emotion and communication that shape experiences and perceptions of risk. What does this mean for those working on the front lines of pandemic care? In this paper we draw on interviews with Australian healthcare workers to explore the intertwining of evidence and affect across space, and ask how this shapes how healthcare workers prepare for and deliver pandemic care. More specifically, we examine how such emotions as fear, uncertainty, dread and solidarity structure the risk environment of a particular place (e.g. an Australian hospital) during a pandemic as it spreads (unevenly) across the globe. We suggest these emotions are a collective production, emergent from both ‘local’ interpersonal moments and the circulation of concern and narrative accounts from elsewhere, which are mediated by social and global news media. Understanding the nuances of the risk environment experienced by healthcare workers may help calibrate appropriate communication and policy responses to ongoing and future global health crises.

2. Background

2.1. COVID-19 in Australia

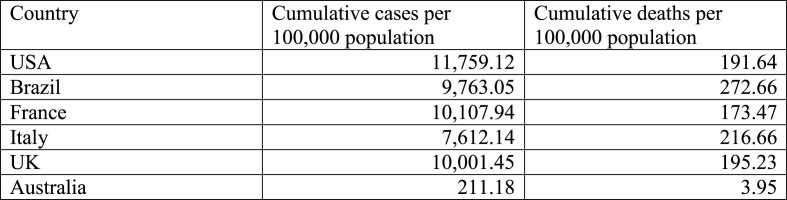

Compared to many countries, Australia has so far seen relatively few COVID-19 cases and deaths. For example, while the USA has had over 11,700 infections and over 191 deaths per 100,000 population, Australia's figures are 211 and under 4, respectively (see Fig. 1 ).1

Fig. 1.

A comparison of cumulative COVID-19 cases and deaths. (Figures correct as of 2 September 2021 – WHO COVID-19 Dashboard (World Health Organization, 2020)) .

It is important to remember, however, that such a trajectory was never guaranteed. Indeed, at the time of writing, Australia is in the midst of a significant new outbreak. Following the first confirmed case in Australia on 25 January 2020 (Caly et al., 2020), there was significant disruption and reorganisation of Australian healthcare and public life more broadly (Andrikopoulos and Johnson 2020). On 1 February 2020, the Australian Government barred foreign nationals who had been in China from entering Australia and required Australian citizens to self-quarantine for 14 days. On 20 March 2020, Australia closed its borders to all non-residents and non-Australian citizens, with limited exceptions, and restricted its citizens' ability to travel out of the country. Compulsory hotel quarantine for overseas arrivals followed. In the months that followed, other measures such as lockdowns, physical distancing, and internal border restrictions fluctuated in intensity as case numbers fell then rose in sporadic outbreaks (Stobart and Duckett 2021). Currently, Australia's international borders remain closed, with limited exemptions (Department of Home Affairs, 2021), and ‘stay at home orders’ have been reintroduced across large parts of Australia.

Although caseloads have remained relatively low by global standards, the Australian experience of the pandemic has not been shaped by epidemiology alone. As scholarship from the sociologies of affect (e.g. Ahmed 2004, 2010; Pedwell 2014) and risk (e.g. Beck 2011; Müller-Mahn et al., 2018), media and communications (e.g. Chouliaraki 2006) and relational and affective geography (e.g Cummins et al., 2007; Anderson 2009), suggests, affect shapes experience in contingent and varied ways. We therefore draw on these bodies of literature – and more recent pandemic-specific scholarship – to help illuminate how Australian healthcare workers’ experiences have been shaped not just by case numbers, but also by processes of collective affect, transnational communication, and knowledge co-production, at the nexus of the local and global.

2.1.1. Place, practice and risk

In its focus on connections, flows and networks, our paper draws on concepts of place and connection from relational and affective geography scholarship (e.g. Cummins et al., 2007; Neely and Nading 2017; Thien 2005). A relational approach identifies ‘places’ as “nodes in local, regional and transnational ‘flows’ of information and other resources” (Cummins et al., 2007: 1832), rather than as geographically bounded, and conceptualises distance/proximity as socio-relational rather than (merely) physical. Thus, the two Australian hospitals, which are the key research sites for this study, are positioned here as nodes in flows of affect, information and evidence. Other salient places-as-nodes for this study include hospital wards in Australia and overseas, and digital spaces such as Facebook groups. Proceeding from an understanding of the internet as “embedded, embodied and everyday” (Hine 2015), we consider both online and offline spaces as part of the socio-geography of knowledge production (Massey 2005: 143) and affective experience.

In thinking about how specific spaces – as constituted by different material configurations, relationships, practices and connections – can give rise to particular affective assemblages and perceptions of safety/risk, the concept of riskscapes, as outlined by Müller-Mahn et al. (2018) is helpful. The concept of riskscapes facilitates a multi-dimensional consideration of risk environments, considering both material threats and how people perceive, communicate, produce, and respond to them (Müller-Mahn et al., 2018). It also orients us towards the spatial dynamics of risk (Gee and Skovdal 2017). Insights from posthuman geographies highlight that riskscapes are relational ‘more than human’ assemblages of objects, bodies and forces (Andrews 2019; Duff 2018). In this paper, we particularly focus on how affects circulate in networks or assemblages, attaching to human and nonhuman bodies/objects that transform (and are transformed by) healthcare workers' relationships and activities. To this, we add time as integral to the production of riskscapes (Müller-Mahn et al., 2018, drawing on Massey 2005) and explore how riskscapes are produced in relation to an unfolding present and imminent potential futures (Neisser and Runkel 2017). Attending to these “cross temporal linkages” (Müller-Mahn et al., 2018: 207), and foregrounding connections across space and scale, provides a useful framework for examining the experiences of healthcare workers during an unfolding global health crisis.

2.1.2. Affective connection across space

Affect scholars have proposed various ways of understanding interactions between human/non-human agents and environments. As a means of understanding the affective environment created by entanglements of bodies, spaces, conditions and objects, the concept of “affective atmosphere” (Anderson 2009; Bissell 2010; Duff 2016) suggests both a nebulous yet powerfully felt sense or mood (Asker et al., 2021), and a relational “propensity” for future actions and feelings (Bissell 2010: 273). Appropriately for the temporal and spatial dynamism of a global pandemic, affective atmospheres are, in Anderson's words, “perpetually forming and deforming, appearing, and disappearing, as bodies enter into relation with one another” (2009: 79). While many conceptualisations of affective atmosphere emphasise the importance of close encounters between bodies in particular spaces (Bissell 2010; Duff 2016), we expand the “spatialised affective field” (Bissell 2010) to encompass transnational and geographically dispersed human and non-human actors. Specifically, we contemplate how emotions circulate through local, national and transnational spaces connecting healthcare workers, how they feel risk, fear or empathy, and are thus drawn into (and out of) collectivities sometimes across vast geographic distances.

We draw on the work of affect scholars who emphasise the importance of examining how emotions circulate and what emotions do (Ahmed 2004; Pedwell 2014). More than individually embodied feelings, affects, as theorised in this way, are collective, instructive, and productive. Thus, affect has a spatial dimension, in the sense that affects such as fear, hate, and belonging can variously bind together or drive apart (Ahmed, 2004). Writing in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States of America, Ahmed contemplates global “affective economies”, reflecting on how fear shifts identifications and alignments, borders and mobilities in concrete and particular ways, and how objects and spaces (e.g. flags and homes) become “sticky signs” of coherence and “fellowship”. While not wishing to conflate a pandemic with acts of terrorism, commonalities emerge, including the role of the global media in eliciting a sense of affective proximity, crystallising imagined communities of existential risk, shaping empathetic (mis)alignments and reshaping everyday practices.

2.1.3. Digital connectivity and instantaneous proximity

Social media, and global news media, are critical players in the choreography of global risk imaginaries, acting as the vehicles for the transmission and co-production of information and affect that “jump the scale” (Swyngedouw 1997) from global to local and vice versa. In the context of the 2003 SARS epidemic, Schillmeier notes, “the world became a multiplicity of emergency rooms” as global media networks documented and displayed SARS in the manner of a live drama (2008: 185). Similarly, in the COVID-19 context, emerging evidence and emotional testimonies (including stories of health system breakdown, shortages of safety equipment, and illness and death among healthcare workers) circulate between globally dispersed collectivities. In a situation of shared threat and potentially shared destiny, media scholar Chouliaraki (also referencing September 11) argues that news media configure the “sufferer-spectator relationship” within “a ‘universal’ psycho-geography” in which spectators identify with the sufferers, affectively and intensely engaging with their “misfortune” (2006: 181). Spatially separated but brought together in affective connections, spectator and sufferer thus inhabit “the space-time of instantaneous proximity” (Chouliaraki 2006: 179).

Digital storytelling, both curated and spontaneous, has amplified and distributed specific pandemic narratives, enabling people to communicate their experiences of care and harm, and share insights on diverse responses to risk (McLean and Maalsen 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has been described as “the Twitter pandemic” (Rosenberg et al. 2020), acknowledging the role of the platform in mediating the co-production of knowledge, hearsay and affect. Although the H1N1 pandemic and Ebola epidemic were also discussed on Twitter and other social media (Fung et al., 2016, Chew and Eysenback, 2010), Twitter has been used widely by medical professionals to share COVID-19-related experiences, resources, advice, and research (Mills et al., 2020, Prager et al., 2021; Kudchadkar and Carroll 2020; O'Glasser et al., 2020).

Healthcare institutions have also sought to use digital platforms to connect holders of expertise and creators of incipient evidence in global knowledge networks (Wilson et al., 2021) and “communities of practice” (Lave and Wenger 1991). Communities of practice have been proposed as a means to generate knowledge and foster “collective moral resilience” in healthcare workers faced with extraordinary (e.g. pandemic) circumstances (Delgado et al., 2021). In Australia, the New South Wales State Government established multidisciplinary clinical groupings called “communities of practice” to support their COVID-19 response. These groups met regularly via video-conference to share strategies, identify issues and provide expert clinical advice (NSW Department of Health, 2020). During a global health crisis, virtual communities of practice enable the mobility of knowledge across space and scale (e.g. regional or global). Whether structured by clinical specialty, hierarchy or geography, these virtual encounters can evoke affective atmospheres (e.g. of fear/hope, trust/mistrust, resilience/distress, solidarity/antagonism) and modes of interprofessional working in extraordinary times (Goldman and Xyrichis 2020).

Drawing together these insights around affect, risk communications and communities of practice, we propose that news media, digital platforms and electronic personal communications are integral to the circulation of affect and evidence during the current pandemic. These dynamics, as they intersect with concepts of risk and place, are key to understanding how pandemics are experienced on the frontlines of healthcare, with important implications for supporting healthcare workers’ wellbeing and resilience.

3. Methods

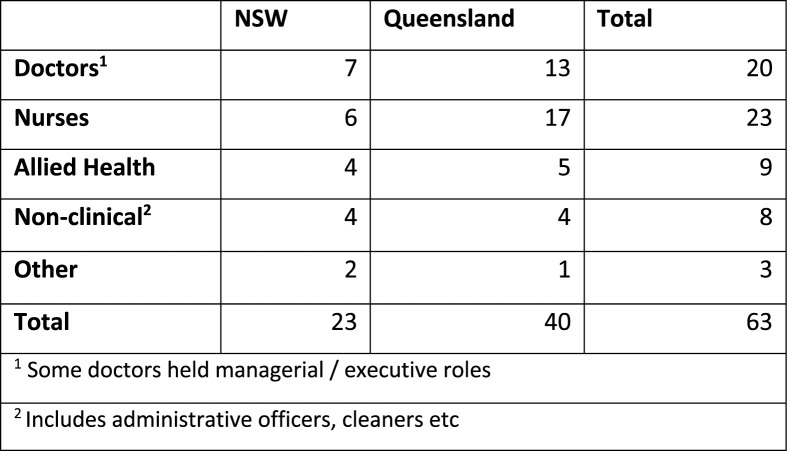

This article draws on in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 63 frontline healthcare workers across two hospital sites in the Australian states of New South Wales and Queensland. The interviews were conducted between September 2020 and March 2021, as part of a broader multi-methods qualitative study into healthcare workers’ experiences of infection prevention and control during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ethics approval was granted for both hospital sites. Participants were recruited across a range of specialties, including infectious diseases, infection prevention and control, emergency medicine, intensive care, anaesthetics, radiology, respiratory medicine, and public health, focusing on people with experiences of preparing for, overseeing or delivering care for COVID-19 patients, across a range of roles and seniority levels (see Fig. 2 ). The interviews explored a variety of issues, including everyday lived experiences; practices, policies, and guidelines; processes of accountability and decision-making; and the broader social significance of the pandemic. Interviews were conducted via Zoom and telephone, were audio recorded and fully transcribed for analysis.

Fig. 2.

Participants by site and role.

Drawing on interpretive traditions within qualitative research, we viewed the accounts as attempts to construct meaning, identities, and practices in a changing and uncertain context. Authors LWV, AB, and KK led the analysis, reading and re-reading transcripts, looking for patterns, constellations, and contradictions in the data. We took a developmental approach, using later interviews to expand, challenge or compare with the tentative knowledge generated in earlier interviews, considering the shifting context in which both interviews and analysis took place. We sought to retain the complexity of participants’ responses, documenting conflicts and contradictions within the data as well as coherent themes and recurring ideas. The final step involved revisiting the literature and seeking out additional conceptual tools that could help make sense of the patterns that had emerged from the data (Ezzy, 2002).

4. Findings

We identified three key elements of Australian healthcare workers’ experiences of affect and evidence: firstly, the circulation of affect (specifically, fear) across space and scale, facilitated by global, local, personal and professional connections; secondly, the attachment of these circulating affects to particular material objects (e.g. masks); and finally, the alignment of healthcare workers within/against collegial groupings, producing “imagined communities of risk” (Beck 2011) and potential venues for co-production of knowledge.

4.1. Fear travels

The uneven spread of infection across the world meant that for many healthcare workers in Australia, the early months of 2020 were characterised by anticipatory fear as they watched their counterparts overseas struggle to contain, and then manage, infections with the novel coronavirus. An infectious diseases doctor, drawing on memories of previous pandemics and news from Italy and the US, recalled a sense of “impending doom, like a tsunami or whatever; you're waiting for it to come at you because you know what could happen.” Anticipatory fear circulated through global news and social media and personal connections, and continued to circulate within physically proximate workspaces and local communications networks. This facilitated a sense of threat based on a situation unfolding thousands of kilometres away, which nonetheless was experienced as affectively proximate. As one senior anaesthetist recalled:

“At one point early on in the pandemic, a colleague came into my office and said that, at this stage, it looked likely that one of us would die by the end of the year based on the way it was going in Europe.” (Anaesthetist, NSW)

Numerous participants cited news media as a primary vehicle for transmission of fear:

“Fear. Absolute fear. That's all it was. Fear of the unknown. You've watched the media of 400,000 deaths in America from COVID.” (ICU nurse, NSW)

“It was all the news from Italy and England and all the people dying, the death rate per day and I'm thinking, ‘Oh god, I'm coming back to this. And this is my ward, this is my area, and it's going to be us.’” (Respiratory nurse, Queensland)

The “mediated immediacy” of television news (Chouliaraki 2006: 21) and the “reflexive identification” (p.157) between the spectator in Australia and sufferer in the US, Italy or England creates “the space-time of instantaneous proximity” in which the spectator is overwhelmed by empathy and imaginatively shares the same humanity, threat, and destiny as the sufferer (p.181). In the midst of an early COVID-19 outbreak in Australia, one radiographer looked around the emergency department and mental images of overwhelmed hospitals from the news elicited anxious thoughts of an imagined shared future:

“… all hell was breaking loose and every single resuscitation room that we have was full of COVID patients, and there was a major trauma flying in from a helicopter and we didn't have anywhere to put them. And everything's out of the room. People have taken everything out of the room to stop it getting contaminated and piled it up in the hallways, and so there's 30 people out in these hallways, there's piles of equipment, and it looks like a war zone. And I just had this moment of those pictures that you see from the New York Times or whatever, of hospitals in America flashing up in your brain and going, ‘This is not dissimilar. Are we going where they're going?’” (Radiographer, NSW)

In that moment, the spatially distant U.S. hospital ward is “loomingly present as the affective fact of the matter” (Massumi 2010: 54); the two wards affectively connected across time and space. The affective atmosphere of the Australian emergency department is generated by the present materiality of their working environment, as well as by vivid imaginaries of pandemic chaos elsewhere. Collectively generated, yet experienced as intensely personal (Anderson 2009), the affective atmosphere resonated through the radiographer's body in the panic attacks they described experiencing on their commute to and from the hospital.

In addition to news media, participants described how fear travelled through transnational professional and personal networks, particularly for the many migrant healthcare workers in Australia:

“There was a lot of fear and anxiety from everyone, […] and you're hearing horror stories from overseas. Because the medical network is so close nowadays. We've all got friends on Twitter and you're getting tweeted a horror story of people in the US splitting ventilators and things.” (Anaesthetist, NSW)

“Probably more than half, I would say, of the consultants, and probably about half of the registrars are UK-trained originally […]. There's quite a big expat [community]– and so there's a degree of shared emotional risk from that point of view.” (Emergency doctor, Queensland)

Here, the entanglement of the “known” (what is happening elsewhere, to others) and the “unknown” (what will happen here, to us) shapes these participants’ perception of risk and their local affective environment. Conversely, this affective intensity increases their sense of belonging to “a social or symbolic transnational field” (Wise and Velayutham 2017: 127).

Globalised fears spread via local interactions in an affective mirroring of the anticipated infection. A respiratory nurse cited ad hoc interactions with hospital colleagues “in the hallway” as the primary source of her “fear of the potential of what was going to happen”:

“Definitely the medical officers, infection control, the ID doctors, consultants. Even the respiratory consultants were very much like, ‘We're two weeks away from Italy. We're this away from that.’”

The overwhelmed Italian hospital ‘haunts’ the hospital hallway in Queensland, and shapes visions of an imagined shared future. Time and space collapse in the healthcare workers' perceptions of (imminent) risk, creating an affective atmosphere dominated by fear.

As workplaces increasingly pivoted to online platforms, these spaces also became important nodes of anxious communication and speculation:

“There were a few ICU Facebook Messenger pages and people were stressing out about, ‘Oh my god, we need to get masks. Where are we going to get masks from? What if we're out of masks?’ […] So they were the places that people were initially talking to each other about, ‘Oh my god, it's happening,’ and, ‘How are we going to do this?’ and, ‘We haven't got enough masks,’ and that sort of thing, and ‘I can't do it because I've got a wife that's got cancer,’ or sharing all those things.” (ICU nurse, Queensland)

The physical space of the hospital hallway and the online space of the Facebook group both constitute nodes in affective networks, which enable perceptions of pandemic conditions in geographically distant places to shape healthcare workers’ riskscapes. Recognising the role of these informal venues in the circulation of fear amongst their colleagues, senior staff initiated more formal venues for communication such as online meetings, email bulletins or outdoor “huddles”, corralling discussions into the realms of guidelines, protocols and research findings.

4.2. Masks: a microcosm of global-local dynamics of affect and evidence

The excerpts above show how fear circulated across place and scale in global and local networks. Fear also took root in particular material objects, adding a further layer of socio-materiality to the affective atmosphere of Australian hospitals (Bille et al., 2015; Lupton et al., 2021). Masks became a focal point for anxiety as Australian healthcare workers anticipated the shortages seen elsewhere:

“I personally didn't want to be in the state of getting to Italy, as the organisation's talking about, and not having the right PPE or wearing masks four days in a row etc, which is what we were definitely talking about.” (Respiratory nurse, Queensland)

Echoing the rhetoric of bio-securitisation, one anaesthetist spoke of “quarantining” the “most appropriate PPE” for colleagues “at the coalface of risk” in anticipation of shortages. Uncertainty about Australian PPE stocks amid disrupted global supply chains (OECD 2020) exacerbated fears prompted by reports of overseas peers caring for patients with inadequate PPE (see Kea et al., 2021):

“That's another fear people had, is how much PPE do we actually have. […] We asked the federal government, who's supposed to control the federal stockpiles, [and they] didn't know. That was information that we – we wouldn't withhold it but we certainly took our time telling people that information so as not to raise mass panic.” (Anaesthetist, NSW)

Quarantining PPE and information about (possible lack of) supplies can be seen as an attempt to control both material and affective elements of the local riskscape. As Gee and Skovdal (2017) note, (mis)trust and (mis)communication are as central to the structuring of pandemic riskscapes as physical boundaries and materials. Indeed, the provision of masks perceived as lower quality was interpreted as a failure to care on the part of healthcare organisations:

“A lot of people have said, ‘It looks like a painter's mask,’ ‘they're going cheaper,’ ‘they don't care,’ that sort of thing. A lot of anger, I guess.” (Respiratory nurse, Queensland)

Masks are a form of material safety. They are also a “signifier of value” (Willis and Smallwood 2021) in the relationship between a healthcare institution and its personnel, and a site of affective displacement; a focal node for more nebulous anxieties during an unfolding and novel pandemic. Changing guidelines around the type of mask that should be worn, by whom, and in what situation, was a significant point of tension in relations between frontline staff and managers. An infection control nurse in Queensland noted her colleagues had “lost all control” in the unfolding pandemic, and ascribed their demands around PPE to an attempt to regain a sense of control: “that was what they could control in the past.” In this way, masks are polysemous and symbolically potent or, as Ahmed (2004) puts it, “sticky signs” (Ahmed 2004: 130) representing and eliciting feelings of fear, safety, care, anger, courage, and (lack of) control (Brown and Sáez, 2021. See also Jones 2021; Lupton et al., 2021; Lynteris 2018).

The micro-site of the mask represents a microcosm of the intersection of global and local, of affect and evidence, which shaped the pandemic riskscapes of Australian healthcare workers. Narratives of scarcity (here and elsewhere) interweave with narratives of care and value. Even at this micro-level of bio-securitisation (Hinchliffe and Bingham 2008), shadows of global experience haunt the scene. Shared uncertainty around the evidence and availability of masks affectively aligns healthcare workers in dramatically different local contexts. Imagined futures manifest as affective presence, highlighting an affective proximity that collapses both spatial and temporal distance.

4.1. Collective alignments of affect and evidence

Ahmed suggests that emotions “align individuals with communities – or bodily space with social space – through the very intensity of their attachments” (2004: 119). In this study, interviews highlighted how the affective intensity of the pandemic shaped healthcare workers’ sense of belonging to a specialised transnational social field (Wise and Velayutham 2017) and an imagined community of global risk (Beck 2011). Empathetic identification with healthcare workers overseas created affective collectives that crossed national borders. Witnessing their direct counterparts in more affected countries amplified a sense of their own vulnerability.

“There was a lot of people very anxious and fearful because they were reading lots of stories from Italy of consultant anaesthetists being in intensive care and dying. So they were obviously pretty fearful.” (Anaesthetist, NSW)

“There are some subspecialty risk groups, like ENT surgeons, who … very early on in the pandemic overseas there were some deaths in ENT surgeons in the UK, which really spooked a lot of people.” (Senior Anaesthetist, NSW)

As noted above, this identification sometimes manifested as a spatialised ‘haunting’ in which healthcare workers imaginatively transposed the overseas workplace onto their own, conjuring an imagined future of uncontrolled spread of disease, overwhelmed health services and personal loss or death.

At the same time, in positioning themselves within these imagined communities of risk, healthcare workers aligned themselves against other colleagues in what one infectious diseases specialist called “a splintering of professional groups”. For example, infectious disease specialists spoke about being “treated as redundant and not necessary” or being seen by colleagues as “rule-makers, without actually being risk-takers”. A senior emergency physician described the difficulty of finding consensus among colleagues in the context of circulating fears, contested evidence, and fractured trust:

“We had lots and lots of meetings with the Infectious Diseases Director trying to find a middle ground based on evidence to reassure people. But because everything's so connected in social media, both mainstream media, but also medical feeds and stuff, we could never get everyone on the same page. There was always a group of colleagues, medical, nursing, whatever, that were never happy with the advice around the PPE. There was always one group that were going to the union around not feeling safe.” (Emergency physician/clinical director, Queensland)

On the ground, fear fractured solidarities between and within professional groups. Staff associated with wards treating (suspected) COVID-19 patients were seen by other staff as “risky bodies” (Bennett 2021): one nursing manager reported that support staff on the COVID ward had been asked not to enter their usual break room. Another nurse manager described feeling “shocked” and “disappointed” when colleagues refused to work in the ICU because of their perception of ICU pandemic nursing as “risky work” (Willis and Smallwood 2021).

On the other hand, the imagined copresence of spatially distanced localities also facilitated information sharing, which helped healthcare workers prepare for what might be ahead. While Italy, China, the UK and US were spectral presences of pandemic catastrophe, they were also positioned as sites of expertise. Participants described how they drew on personal and professional connections to gather emerging evidence:

“Very early on we tapped into some video conferences from some of the intensivists from Italy, and while the numbers are pretty disturbing, it also helped us work out where to go and what not to do.” (Senior Anaesthetist, NSW).

“We had a consultant here that had family in China and people in Melbourne and people in the United States that were obviously giving us information […]. We had a lot of literature coming out of China. So we based our practices around that.” (Nurse Unit Manager, NSW)

Incipient knowledge was shared, tested and iteratively improved in formal scientific journals, government websites and pronouncements by recognised authorities (e.g. WHO and the UK Resuscitation Council) as well as in informal spaces such as specialist online discussion forums, video conferences, personal communications and social media, particularly Twitter. Emerging evidence circulated through social media networks, channelled through hashtags such as #medtwitter and relationships of trust between friends and colleagues:

“As you had more and more cases around the world, we also had our colleagues in ICU and ED contacting their colleagues, as much as we were, in the UK, Ireland, Germany, wherever, and information sharing with your mates on email or else, again, #MedTwitter. Again, there's some great videos on there, which showed you what were good ideas and bad ideas. That definitely progressed things quite rapidly. The only downfall is that if you just take the video clip that you watch as absolute fact, you can get yourself in a world of trouble. So, we tried everything, basically!” (Anaesthetist, NSW)

As this anaesthetist describes, incipient knowledge was brought into the workplace, refined, and returned to the network for further distribution and refinement. In a pandemic, access to speedy information is important, and healthcare workers drew on the affordances of social media to facilitate this. From a management perspective, however, these multiple ‘unauthorised’ sources can provide conflicting narratives which coalesce in affective atmospheres dominated by confusion and fear, as described above.

Governmental and other institutions operating in diverse locations and across different scales (e.g. local, state, national, international) have attempted to direct this sharing of expertise into official channels. At a hospital level, as seen above, managers attempted to ‘securitise’ (contain and govern) healthcare workers' pandemic affect by relocating discussions within more formal and localised platforms. At a state level, the NSW Government's “communities of practice” operated in similar ways to corral and operationalise the expertise held by clinicians and researchers geographically dispersed across the state. An infectious diseases doctor explained that their experience of sharing and co-producing knowledge in managed online spaces had been:

“a real learning about what my colleagues do and what their risks are and how to make those safe recommendations. You need to be very aware of what others do. And I think that that had been missing for a long time. I know that I had never considered it, and I don't think I'm the only one. And it was actually very interesting seeing specialist colleagues, surgical colleagues, really investigating the scientific reasoning behind why we think their colleagues were developing infection and dying. […] Obviously, there can be a lot of assumptions made between specialist groups, which are not always very helpful. And I have found that the way I've worked with them, collaborated with them, has improved based on this.” (Infectious diseases doctor, NSW)

These comments, in conjunction with the observations above relating to globally dispersed knowledge networks, illustrate how digital communications across in/formal arrangements worked to move evidence and expertise across geographical distances and to create spaces for knowledge co-production and interprofessional working by drawing together dispersed expertise. The infectious diseases doctor also articulates the entanglements of empathy and evidence that structured their riskscape: understanding the practices and fears of colleagues beyond their immediate specialty or hospital has the potential to repair the fracturing of empathy described earlier in the paper, with potentially long-lasting effects for practice.

5. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic and its inexorable spread across the globe is both a tangible manifestation, and temporary disruptor, of the transnational interconnectedness of contemporary global society. In particular, the “time-space compression” (Harvey 1990) created by contemporary information technologies enables news and its affective corollaries to spread instantaneously, creating a kind of “global intimacy” (Chouliaraki 2006) at a time of physical distancing and isolation. Judith Butler's contention that “vulnerability may be a function of openness, that is, of being open to a world that is not fully known or predictable” (2014: 114) gains renewed salience in a global pandemic. Our analysis indicates that the vulnerability in question relates not only to infective risk but also to emotions, such as fear, which also meaningfully shape the riskscapes that healthcare workers inhabit.

From the vantage point of late 2020, when these interviews were conducted, participants expressed broadly positive views of the measures taken by national and state governments, recognising that border closures and lockdowns had avoided the health system overload and loss of life they had seen in reports from overseas. For many healthcare workers, hope had replaced fear: hope that Australia might continue to experience manageable outbreaks with minimal loss of life; hope that hand hygiene and other everyday infection control practices might endure among healthcare workers and the public; hope for an effective vaccine; hope that future pandemics might be better managed due to lessons learned (see Andrews 2018 on hope and health geographies). Tensions remained, however, at a local level, over staffing levels and funding, guidelines for PPE use, and a sense that hospital executives had not adequately responded to the vulnerability felt by frontline staff.

The affective intensity of an unfolding pandemic contracts distance and time, bringing the present ‘elsewhere’ to the present ‘here’ as both affective fact (Massumi 2010) and spectral future – an imagined copresence (Wise and Velayutham 2017: 120) of spatially and temporally distant locations. The pandemic experiences of Australian healthcare workers highlight health practice as “a complexly inter-scaled networked global phenomenon” (Andrews et al., 2021b: 34). Underestimating the significance of the affective globalisation of healthcare workers during a pandemic may lead to institutional responses (e.g. communication and support measures) inadequate for producing a sense of material and psychological safety for staff, even when local epidemiological conditions may not match the worst affected regions. At a local level, these shifting “imagined communities of risk” (Beck 2011) may hinder the interprofessional collaborations that have been central to hospitals' crisis pandemic responses (Xyrichis and Williams 2020). In our study settings, multidisciplinary communities of practice, interprofessional simulation teams (Failla and Macauley, 2014), and interdepartmental COVID committees were convened to share expertise and shape the hospitals' response. Nevertheless, fear, mistrust and confusion continued to permeate participants' responses, particularly those participants on the peripheries of institutional power.

Metaphorical language has been prominent in communications about the novel phenomenon of COVID-19 and responses to it (Kearns, 2021; Panzeri et al., 2021; Semino 2021). Viral metaphors have also been used to draw attention to social phenomena related to the pandemic. As early as February 2020, the WHO warned of the “infodemic” of misinformation spreading via social media (Zarocostas 2020). Pre-dating the pandemic, metaphors of contagion have been common in affect scholarship (Ahmed 2010; Gibbs 2001; Pile, 2010). As Ahmed notes (2010), this kind of conceptualisation has its uses, in “showing how affects pass between bodies, affecting bodily surfaces”. However, Ahmed also cautions us not to “underestimate the extent to which affects are contingent” (p.36). In healthcare, the affective atmospheres experienced by those on the peripheries of power, yet close to potential viral exposure (the junior radiographer in the emergency department; COVID ward nurses, cleaners and orderlies; clerical staff in clinical areas) may differ from those experienced by senior colleagues, or those less involved in hands-on care of COVID patients. Bringing together the concepts of affective atmosphere and riskscapes facilitates an understanding of how individual and collective perceptions of risk – and the emotions associated with them – are shaped by local, national and global material conditions and policies, structured by power and technology, and produced by social practices, including acts of identification and empathy that transcend local conditions.

At the same time as these interconnections produced riskscapes in which fear was often the dominant affective mode, they produced pathways to knowledge and evidence, which may help manage the immediate risk (e.g. disseminating information about the efficacy of treatments and infection mitigation measures), create new empathetic and evidentiary alignments, and point to a pathway out of the pandemic. Across multiple scales, from hospital ward to nation-state, networks and connections present both challenges and opportunities for those trying to manage healthcare workers’ infective and affective risk environments.

Funding acknowledgement

The project was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), through an emergency response proposal co-ordinated by APPRISE, The Australian Partnership for Preparedness Research for Infectious Disease Emergencies (Grant Variation APPRISE COVID-19 Emergency Response APP1116530).

Footnotes

Statistics for individual Australian states vary widely, as outbreaks have remained relatively localised due to internal border controls and locally differentiated public health measures.

References

- Ahmed S. Affective economies. Soc. Text. 2004;22(2):117–139. doi: 10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S. In: The Affect Theory Reader. Gregg M., Seigworth G., editors. Duke University Press; 2010. Happy objects. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B. Affective atmospheres. Emotion. Space Soc. 2009;2(2):77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2009.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G.J. Health geographies I: the presence of hope. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2018;42(5):789–798. doi: 10.1177/0309132517731220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G.J. Health geographies II. The posthuman turn’ Progress in Human Geography. 2019;43(6):1109–1119. doi: 10.1177/0309132518805812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G.J., Crooks V.A., Pearce J.R., Messina J.P. Springer International Publishing; 2021. ‘Introduction’ in COVID-19 and Similar Futures; pp. 1–19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G.J., Peter E., Rowland E. Springer; Cham: 2021. Place and Professional Practice : the Geographies in Healthcare Work. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrikopoulos S., Johnson G. The Australian response to the COVID-19 pandemic and diabetes - lessons learned. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020;165:108246. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asker C., Lucas G., Lea J. In: COVID-19 and Similar Futures. Global Perspectives on Health Geography. Andrews G.J., Crooks V.A., Pearce J.R., Messina J.P., editors. Springer; Cham: 2021. Non-representational approaches to COVID-19; pp. 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Beck U. Cosmopolitanism as imagined communities of global risk. Am. Behav. Sci. 2011;55(10):1346–1361. doi: 10.1177/0002764211409739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J.A. Everyday life and the management of risky bodies in the COVID-19 era. Cult. Stud. 2021;35(2–3):347–357. doi: 10.1080/09502386.2021.1898015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bille M., Bjerregaard P., Sørensen T.F. Staging atmospheres: materiality, culture, and the texture of the in-between. Emotion, Space Soc. 2015;15:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2014.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bissell D. A changing sense of place: geography and COVID-19. Geogr. Res. 2021;59:150–159. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bissell D. Passenger mobilities: affective atmospheres and the sociality of public transport. Environ. Plann. Soc. Space. 2010;28(2):270–289. [Google Scholar]

- Brown H., Sáez M. Ebola separations: trust, crisis, and ‘social distancing’ in West Africa. J. Roy. Anthropol. Inst. 2021;27(1):9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. Bodily vulnerability, coalitions, and street politics. Crit. Stud. 2014;37:99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Caly L., Druce J., Roberts J., Bond K., Tran T., Kostecki R., Yoga Y., Naughton W., Taiaroa G., Seemann T., Schultz M.B., Howden B.P., Korman T.M., Lewin S.R., Williamson D.A., Catton M.G. Isolation and rapid sharing of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) from the first patient diagnosed with COVID-19 in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2020;212(10):459–462. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouliaraki L. SAGE; 2006. The Spectatorship of Suffering. [Google Scholar]

- Chew C., Eysenbach G. Pandemics in the age of twitter: content analysis of tweets during the 2009 H1N1 outbreak. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e14118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S., Curtis S., Diez-Roux A.V., Macintyre S. Understanding and representing ‘place’ in health research: a relational approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007;65(9):1825–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado J., Siow S., de Groot J., McLane B., Hedlin M. Towards collective moral resilience: the potential of communities of practice during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J. Med. Ethics. 2021;47:374–382. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Home Affairs . 2021. Travel Restrictions | COVID-19 and the Border.https://covid19.homeaffairs.gov.au/travel-restrictions viewed 11 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Duff C. In: Routledge Handbook of Health Geography. Andrews G.J., Pearce J., Crooks V.A., editors. Taylor and Francis; 2018. After posthumanism: health geographies of networks and assemblages; pp. 138–143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duff C. Atmospheres of recovery: assemblages of health. Environ. Plann.: Econ Space. 2016;48(1):58–74. doi: 10.1177/0308518X15603222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzy D. Routledge; 2002. Qualitative Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Failla K.R., Macauley K. Interprofessional simulation: a concept analysis. Clin. Simulat. Nurs. 2014;10(11):574–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ecns.2014.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fung I.C., Duke C.H., Finch K.C., Snook K.R., Tseng P.L., Hernandez A.C., Gambhir M., Fu K.W., Tse Z.T.H. Ebola virus disease and social media: a systematic review. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2016;44(12):1660–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee S., Skovdal M. Navigating 'riskscapes': the experiences of international health care workers responding to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Health Place. 2017;45:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs A. Contagious feelings: Pauline Hanson and the epidemiology of affect. Aust. Humanit. Rev. 2001;24(Dec) [Google Scholar]

- Goldman J., Xyrichis A. Interprofessional working during the COVID-19 pandemic: sociological insights. J. Interprof. Care. 2020;34(5):580–582. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1806220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. Blackwell; Oxford: 1990. The Condition of Postmodernity : an Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliffe S., Bingham N. Securing life: the emerging practices of biosecurity. Environ. Plann. 2008;40(7):1534–1551. [Google Scholar]

- Hine C. Routledge; 2015. Ethnography for the Internet: Embedded, Embodied and Everyday. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. In: Viral Discourse. Jones R., editor. Cambridge University Press; 2021. The veil of civilization and the semiotics of the mask. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kea B., Johnson A., Lin A., Lapidus J., Cook J.N., Choi C., Chang B.P., Probst M.A., Park J., Atzema C., Coll-Vinent B., Constantino G., Pozhidayeva D., Wilson A., Zell A., Hansen M. An international survey of healthcare workers use of personal protective equipment during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Phys. Open. 2021;2(2) doi: 10.1002/emp2.12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns R. Narrative and metaphors in New Zealand’s efforts to eliminate COVID-19. Geographical Research. 2021;59:324–330. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kudchadkar S.R., Carroll C.L. Using social media for rapid information dissemination in a pandemic: #PedsICU and coronavirus disease 2019. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2020;21(8):e538–e546. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lave J., Wenger E. Cambridge University Press; 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton D., Southerton C., Clark M., Watson A. De Gruyter; 2021. The Face Mask in COVID Times. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynteris C. Plague masks: the visual emergence of anti-epidemic personal protection equipment. Med. Anthropol. 2018;37(6):442–457. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2017.1423072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey D. Sage; 2005. For Space. [Google Scholar]

- Massumi B. In: The Affect Theory Reader. Gregg M., Seigworth G., editors. Duke University Press; 2010. The future birth of the affective fact: the political ontology of threat; pp. 52–70. [Google Scholar]

- McLean J., Maalsen S. In: COVID-19 and Similar Futures. Global Perspectives on Health Geography. Andrews G.J., Crooks V.A., Pearce J.R., Messina J.P., editors. Springer; Cham: 2021. Geographies of digital storytelling: care and harm in a pandemic; pp. 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Mills J., Li C., Fullerton S., Chapman M., Jap J., Sinclair C., Collins A., Campbell E. Staying connected and informed: online resources and virtual communities of practice supporting palliative care during the novel coronavirus pandemic. Prog. Palliat. Care. 2020;28(4):251–253. doi: 10.1080/09699260.2020.1759876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Mahn D., Everts J., Stephan C. Riskscapes revisited - exploring the relationship between risk, space and practice. Erdkunde. 2018;72(3):197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Neely A., Nading A. Global health from the outside: the promise of place-based research. Health Place. 2017;45:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisser F., Runkel S. The future is now! Extrapolated riskscapes, anticipatory action and the management of potential emergencies. Geoforum. 2017;82:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NSW Department of Health . 2020. Communities of Practice.https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/covid-19/communities-of-practice/Pages/default.aspx [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2020. The Face Mask Global Value Chain in the COVID-19 Outbreak: Evidence and Policy Lessons.https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-face-mask-global-value-chain-in-the-COVID-19-outbreak-evidence-and-policy-lessons-a4df866d/ [Google Scholar]

- O'Glasser A.Y., Jaffe R.C., Brooks M. To tweet or not to tweet, that is the question. Semin. Nephrol. 2020;40(3):249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2020.04.003. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzeri F., Di Paola S., Domaneschi F. Does the COVID-19 war metaphor influence reasoning? PLoS One. 2021;16(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250651. e0250651–e0250651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedwell C. Palgrave Macmillan; 2014. Affective Relations: the Transnational Politics of Empathy. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pile S. Emotions and affect in recent human geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 2010;35(1):5–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2009.00368.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prager R., Pratte M.T., Unni R.R., et al. Content analysis and characterization of medical tweets during the early covid-19 pandemic. Cureus. 2021;13(2) doi: 10.7759/cureus.13594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg H., Syed S., Rezaie S. The Twitter pandemic: the critical role of Twitter in the dissemination of medical information and misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. CJEM. 2020;22(4):418–421. doi: 10.1017/cem.2020.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Redwood R., Kitchin R., Apostolopoulou E., Rickards L., Blackman T., Crampton J., et al. Geographies of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2020;10(2):97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Schillmeier M. Globalizing risks – the cosmo-politics of SARS and its impact on globalizing sociology. Mobilities. 2008;3(2):179–199. [Google Scholar]

- Semino E. “Not soldiers but fire-fighters” – metaphors and covid-19. Health Commun. 2021;36(1):50–58. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1844989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stobart A., Duckett S. Australia's response to COVID-19. Health Econ. Pol. Law. 2021;1–29 doi: 10.1017/S1744133121000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw E. In: Spaces of Globalization: Reasserting the Power of the Local. Cox K., editor. Guilford Press; 1997. Neither global nor local: ‘Glocalization’ and the politics of scale; pp. 137–166. [Google Scholar]

- Thien D. After or beyond feeling? A consideration of affect and emotion in geography. Area. 2005;37(4):450–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2005.00643a.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willis K., Smallwood N. In: The COVID-19 Crisis. Lupton D., Willis K., editors. Routledge; 2021. Risky work: providing healthcare in the age of COVID-19; pp. 168–180. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K., Dennison C., Strumminger B., Armistad A., Osuka H., Montoya E., Padoveze M.C., Arora S., Park B., Lessa F.C. Clinical Infectious Diseases; 2021. Building a Virtual Global Knowledge Network during COVID-19: the Infection Prevention and Control Global Webinar Series. ciab320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise A., Velayutham S. Transnational affect and emotion in migration research. Int. J. Sociol. 2017;47(2):116–130. doi: 10.1080/00207659.2017.1300468. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. WHO COVID-19 Dashboard.https://covid19.who.int [Google Scholar]

- Xyrichis A., Williams S. Strengthening health systems response to COVID-19: interprofessional science rising to the challenge. J. Interprof. Care. 2020;34(5):577–579. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1829037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarocostas J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]