Abstract

HIV prevention is critically important during pregnancy, however, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is underutilized. We conducted a survey of pregnant and non-pregnant women in a high HIV prevalence community in Washington D.C. to evaluate determinants of PrEP initiation during pregnancy. 201 pregnant women and a reference population of 1103 non-pregnant women completed the survey. Among pregnant women, mean age was 26.9 years; the majority were Black with household-incomes below the federal poverty level. Despite low perceived risk of HIV acquisition and low prior awareness of PrEP, 10.5% of respondents planned to initiate PrEP during pregnancy. Pregnant women identified safety, efficacy, and social network and medical provider support as key factors in PrEP uptake intention. The belief that PrEP will “protect (their) baby from HIV” was associated with PrEP uptake intention during pregnancy. Concerns regarding maternal/fetal side effects, and safety in pregnancy or while breastfeeding were not identified as deterrents to uptake intention. When compared to a nonpregnant sample, there were no significant differences in uptake intention between the two samples. These findings support the need for prenatal educational interventions to promote HIV prevention during pregnancy, as well as interventions that center on the role of providers in the provision of PrEP.

Keywords: Behavioral intention, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), HIV prevention, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), pregnancy, Integrated Model of Behavior Prediction, psychosocial determinants, women, high prevalence, reasoned action approach

Introduction

HIV prevention during pregnancy is critical for both mother and fetus. HIV incidence among pregnant and postpartum women is double to quadruple rates outside of pregnancy (Gray et al., 2005; Keating et al., 2012; Moodley et al., 2009; Mugo et al., 2011; Thomson et al., 2018). This increased incidence is attributed to behavioral and biological changes during pregnancy (Gray et al., 2005; Groer et al., 2010; Moodley et al., 2009; Mugo et al., 2011). Behaviorally, without motivation to avoid pregnancy condom use is markedly decreased during this period (Gray et al., 2005; Keating et al., 2012; Onah et al., 2002). Greater biological susceptibility in pregnancy is attributed to increased innate and suppressed adaptive immunity, increased genital tract inflammation, alterations in vaginal microbiota, decreased vaginal epithelium integrity, and gross and micro-trauma to the genital tract during delivery (Groer et al., 2010; Hapgood et al., 2018; Mugo et al., 2011). Although the increased incidence of HIV in pregnancy and postpartum has primarily been demonstrated in sub-Saharan Africa, the pregnancy-associated increased biological and behavioral susceptibility transcends geographic boundaries. HIV prevention during pregnancy is critically important in high resource settings, especially settings with high HIV prevalence. Prevention of HIV is especially critical during pregnancy secondary to the risk of perinatal transmission; data from high and low resource settings demonstrate that perinatal transmission is 9–15 fold higher in women newly diagnosed with HIV during pregnancy compared to with chronic infection (22% vs 1.8%) (Birkhead et al., 2010; Drake et al., 2014).

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine reduces HIV acquisition by up to 92% when adherence is high (Baeten et al., 2012; Murnane et al., 2013; Thigpen et al., 2012). The most recent guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the World Health Organization offer consensus that all viable prevention options should be made available to women at risk for HIV, including during pregnancy and lactation (Committee on Gynecologic Practices, 2014; WHO, 2017). Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine has been shown to be safe (for both treatment and prevention of HIV) (AIDSinfo, n.d.; Flynn et al., 2011; Heffron et al., 2016; Heffron et al., 2017, 2018; Joseph Davey et al., 2020; Kourtis et al., 2018; Mirochnick et al., 2014; Mofenson et al., 2017; Nachega et al., 2017; Pintye et al., 2017; Salvadori et al., 2018) during pregnancy, however, PrEP remains underutilized.

Determinants of PrEP uptake and continuation among women in the United States (US) are poorly understood. Despite the need for HIV prevention in pregnancy, we found no published data on attitudes towards and acceptability of PrEP, nor determinants of PrEP uptake during pregnancy in resource rich settings. To address this gap in knowledge, we conducted a survey of pregnant women in a high prevalence HIV community in Washington D.C. (DC) to understand awareness of, attitudes towards, and beliefs about PrEP, and to model the psychosocial and behavioral determinants of PrEP uptake intention during pregnancy in order to identify potential interventions to address inequities in PrEP use. This study is a critical first step to better understanding limited uptake among women specifically during pregnancy, given the increased risk of HIV acquisition during pregnancy and postpartum and the potential for perinatal transmission. To contextualize these data in on-going pregnancies and to understand what, if any, factors influencing PrEP initiation were unique to pregnancy, we compare the responses from this survey to those of women seeking reproductive healthcare without on-going pregnancies.

Materials and methods

Study design and survey methodology

We conducted an anonymous survey of a convenience sample of pregnant women receiving prenatal care at a tertiary care center in DC, serving an inner-city and high HIV prevalence community. Prior to study initiation, we obtained institutional review board (IRB) approval (#2017–166). We approached women in the waiting room of the obstetrics and gynecology clinic from June 2017 to January 2019; after informed consent, women completed the survey on a tablet in the exam room while waiting for their provider. The instrument included a five-minute Centers for Disease Control informational video on PrEP (CDC, n.d.) and 117-question survey assessing demographics, a priori awareness of PrEP, and PrEP uptake intention during and after pregnancy. Participants were reimbursed with a gift card. We provided a referral and a provider-to-provider warm hand-off for participants interested in starting PrEP.

Given the lack of literature on the attitudes towards PrEP among women during pregnancy, this research was hypothesis generating, rather than hypothesis driven. As this research was exploratory, the projected sample size (N = 200) was based upon review of literature in non-pregnant patient populations (Garfinkel et al., 2017; Patel et al., 2019; Willie et al., 2017). We selected a cross-sectional, quantitative design to evaluate perceived risk of and behavioral risk factors for HIV acquisition, to assess awareness of PrEP and intention to initiate PrEP, and to model the psychosocial and behavioral determinants of PrEP initiation among women during pregnancy. Although cross-sectional design precludes relating psychosocial determinants of PrEP uptake intention to behavioral outcomes, substantial research supports the association between intentions and behaviors, especially when environmental barriers are low (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010).

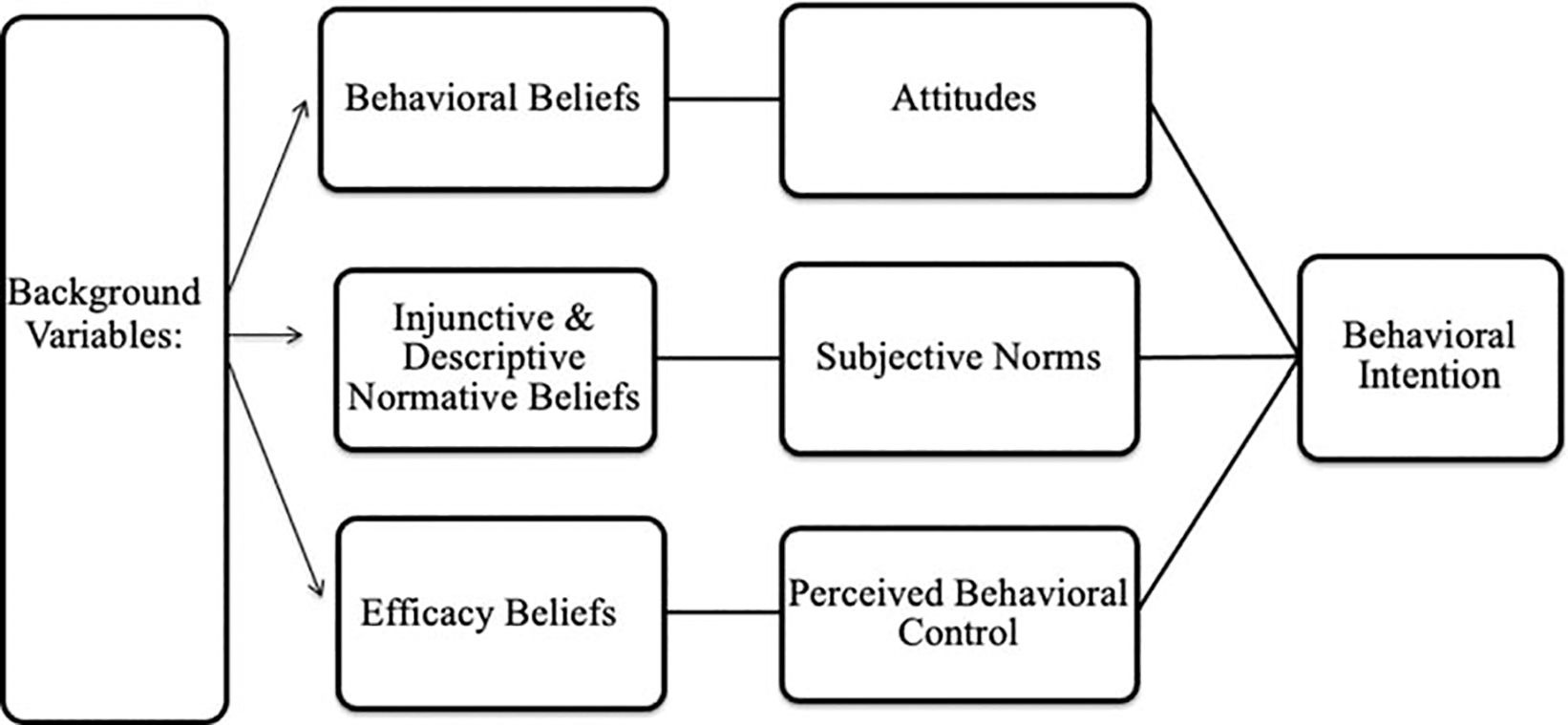

The survey, which was guided by the Integrated Model of Behavioral Prediction (IMBP) (Fishbein, 2009; Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010; Yzer, 2012), was previously psychometrically validated in a demographically and geographically commensurate population (Hull et al., 2017) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of PrEP uptake intention using the Integrated Model of Behavioral Prediction (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010).

We assessed behavioral intentions by specifying the target of the behavioral intention (i.e., the survey participant), action (i.e., using PrEP), context (i.e., to prevent HIV), and time (i.e., during pregnancy and in the next 12 months) (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). We measured behavioral intention using three questions: Do you plan to use PrEP to reduce your risk of getting HIV in the next 12 months? Do you plan to take PrEP during pregnancy to reduce your risk of getting HIV? Do you plan to take PrEP after pregnancy to reduce your risk of getting HIV?

In line with the IMBP, we assessed the psychosocial predictors of behavioral intentions (i.e., attitudes, norms, self-efficacy) at both the global and belief levels (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Global measures assessed participants overall perceptions of favorability (i.e., attitudes), social acceptability (i.e., norms) and agency (i.e., self-efficacy). Belief level measures assessed specific outcome expectations (e.g., safety, efficacy, side-effects), specific normative referents supportiveness (e.g., medical providers, family members, peers) and ones’ ability to overcome specific barriers (e.g., taking the medication, even if side effects are present, remembering to take the pill).

For the reference population of women without continuing pregnancies, subsequently referred to as the “non-pregnant” population, we used survey data from a contemporary, cross-sectional study of women seeking family planning and/or sexual health services between July 2018 and 2019, using identical data collection procedures (IRB# 2017–0870). Non-pregnant women completed with surveys while seeking reproductive health care at a Department of Health sexual health clinic or a family planning and preventative services clinic, offering termination and contraceptive services.

Study setting

DC is an epicenter of the HIV epidemic in the US. The prevalence of HIV among women in DC is 1209 per 100,000, nearly seven-fold the national average (170 per 100,000) (Bowser et al., 2020; Magnus et al., 2014). DC Health estimates that the prevalence of HIV among women of reproductive age is 1.9%; with even higher prevalence among women of color (Bowser et al., 2020). All three clinical sites from which the participants were recruited offer education on HIV prevention and prescriptions for PrEP to women as part of standard of care. PrEP is covered by all major commercial and government-sponsored insurance plans in DC and DC Health supplies PrEP medication and offers associated follow-up visits and laboratory tests free of charge to uninsured patients and to patients who do not have prescription coverage.

Data analysis

We analyzed the survey results of the pregnant sample using descriptive statistics, including demographic characteristics, perceived HIV risk, attitudes, efficacy, norms, and PrEP uptake intention, and a comparative analysis of characteristics and trimester by PrEP intention (both during pregnancy and within 12 months). We performed bivariate analyses to evaluate barriers and facilitators of intention to initiate PrEP using Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and Student’s t-test, when appropriate. We then performed the same for the non-pregnant sample. Additionally, we compared pregnant vs non-pregnant sample by characteristics and by PrEP intentions. Lastly, to examine intention to initiate PrEP between the pregnant and non-pregnant cohort, we used a multivariable logistic regression model, in which PrEP intention was the main outcome; the main explanatory variable of interest was pregnancy status, other explanatory variables included marital status, education level, income, and risk behavior. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS 9.4 Software | SAS, n.d.).

Results

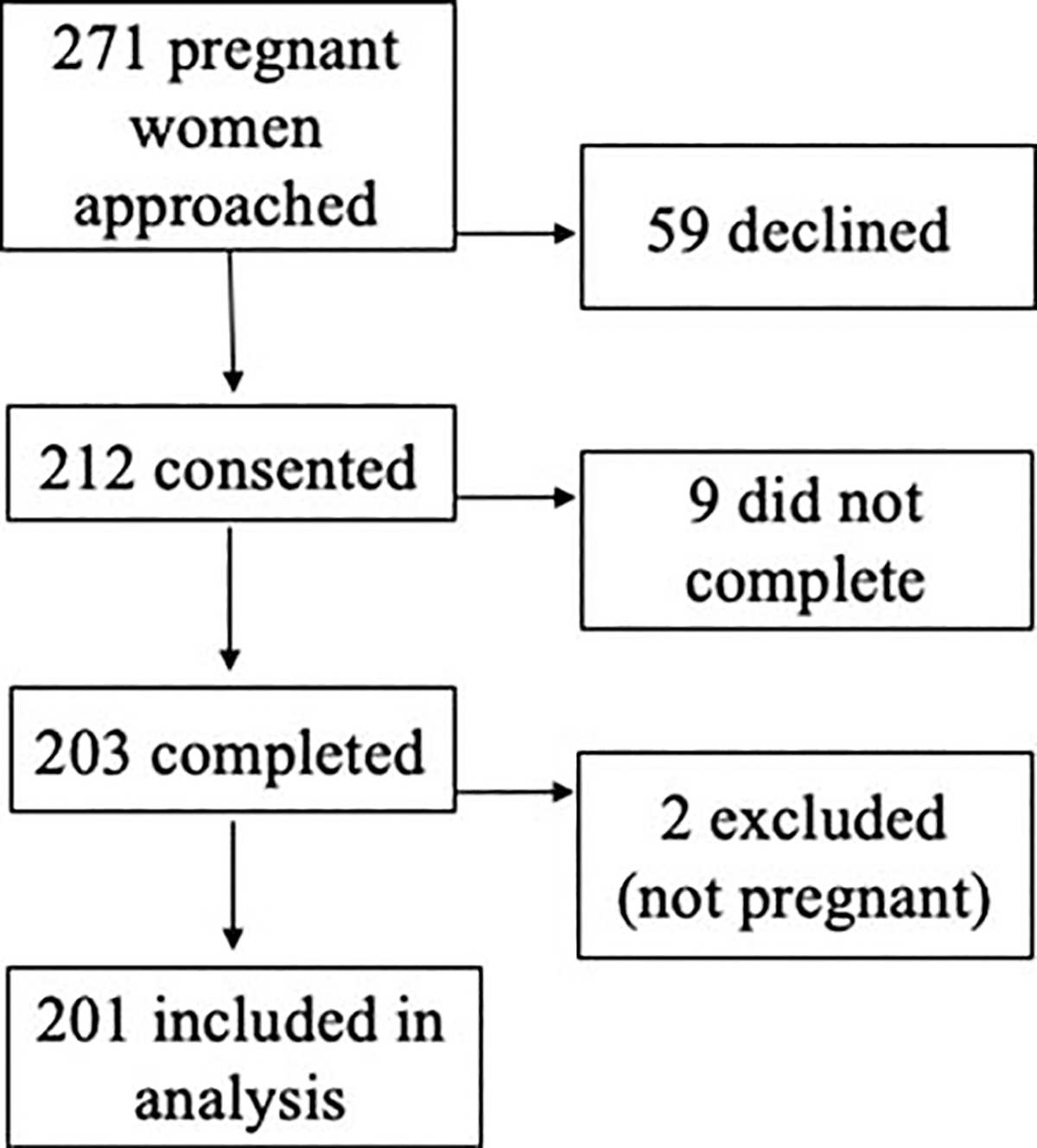

We included 201 completed questionnaires in this analysis; Figure 2 depicts the study flow. The reference population of non-pregnant women included 1103 observations.

Figure 2.

CONSORT flow diagram of survey recruitment in pregnant population.

Sample characteristics

In the pregnant population (N = 201), mean age was 26.9 (±5.6) and the majority of respondents were African-American/Black (86.1%) (Table 1). Thirty (14.9%) were in their first trimester, 62 (30.9%) in their second trimester, and 109 (54.2%) in their third. Approximately half reported being unmarried or “single” (51.7%) and half (47.2%) married or living together. The vast majority of women had completed ≥ 12th grade/GED (91.1%). Although 54.2% reported full or part-time employment, 74.6% reported government-sponsored health insurance (Medicaid), indicating household incomes below the federal poverty level. The only demographic or socioeconomic difference by trimester was in distribution of reported income; more women in their first trimester reported an annual household income of ≤$4,999, compared to women in the other trimesters (data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of pregnant and non-pregnant participants

| Pregnant population (Np = 201)a |

Non-pregnant population (Nn = 1103)b |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)c | No PrEP uptake intention (n = 180) | PrEP uptake intention during pregnancy (n = 21) | p-valued | n (%) | No PrEP uptake intention (n = 844) | PrEP uptake intention in next 12 months (n = 259) | p-valued | p-valuee | |

| (A) Demographic characteristics | |||||||||

| Age (mean(SD)) | 26.88 (5.57) |

27.09 (5.33) | 25.05 (7.23) | 0.22 | 28.80 (9.68) |

28.82 (9.78) | 28.72 (9.40) | 0.88 | <0.01 |

| Trimester | 0.15 | N/Af | |||||||

| First | 30 (14.93) | 24 (13.33) | 6 (28.57) | ||||||

| Second | 62 (30.85) | 58 (32.22) | 4 (19.05) | ||||||

| Third | 109 (54.23) | 98 (54.44) | 11 (52.38) | ||||||

| Race (Np = 194; Nn = 1087) | 0.29 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| White/Caucasian | 3 (1.55) | 3 (1.73) | 0(0) | 104 (9.57) | 100 (12.03) | 4 (1.56) | |||

| Black/African American | 167 (86.08) | 148 (85.55) | 19 (90.48) | 765 (70.38) | 559 (67.27) | 206 (80.47) | |||

| FHispanic | 16 (8.25) | 16 (9.25) | 0(0) | 147 (13.52) | 116 (13.96) | 31 (12.11) | |||

| Others | 8 (4.12) | 6 (3.47) | 2 (9.5) | 71 (6.53) | 56 (6.74) | 15 (5.86) | |||

| Marital status (Nn = 1096) | 0.04 | 0.16 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Married or living together | 95 (47.26) | 89 (49.44) | 6 (28.57) | 140 (12.77) | 116 (13.83) | 24 (9.34) | |||

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 2 (1.00) | 1 (0.56) | 1 (4.76) | 67 (6.11) | 52 (6.20) | 15 (5.84) | |||

| Single or never married | 104 (51.74) | 90 (50.00) | 14 (66.67) | 889 (81.11) | 671 (79.98) | 218 (84.82) | |||

| Education completed (Nn = 1098) | 0.73 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Grades 9–11 | 18 (8.96) | 16 (8.89) | 2 (9.52) | 76 (6.92) | 45 (5.35) | 31 (12.06) | |||

| FHigh school or GED | 89 (44.28) | 77 (42.78) | 12 (57.14) | 303 (27.60) | 210 (24.97) | 93 (36.19) | |||

| Some college, associate degree, or technical degree | 78 (38.81) | 72 (40.00) | 6 (28.57) | 410 (37.34) | 325 (38.64) | 85 (33.07) | |||

| Bachelor’s Degree | 10 (4.98) | 9 (5.00) | 1 (4.76) | 216 (19.67) | 184 (21.88) | 32 (12.45) | |||

| Post-graduate studies | 6 (2.99) | 6 (3.33) | 0 (0.00) | 93 (8.47) | 77 (9.16) | 16 (6.23) | |||

| Employment status (Nn = 1076) | 0.90 | 0.06 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Employed full-time | 72 (35.82) | 65 (36.11) | 7 (33.33) | 474 (44.05) | 370 (44.96) | 104 (41.11) | |||

| Employed part-time | 37 (18.41) | 32 (17.78) | 5 (23.81) | 231 (21.47) | 179 (21.75) | 52 (20.55) | |||

| Student | 10 (4.98) | 9 (5.00) | 1 (4.76) | 101 (9.39) | 83 (10.09) | 18 (7.11) | |||

| Unable to work or Unemployed | 82 (40.8) | 74 (41.11) | 8 (38.10) | 270 (25.09) | 191 (23.21) | 79 (31.23) | |||

| Income level (Np = 175; Nn = 962) | 0.28 | <0.01 | 0.04 | ||||||

| 0–$14,999 | 80 (45.71) | 68 (43.87) | 12 (60.00) | 403 (41.89) | 284 (38.64) | 119 (52.42) | |||

| $15,000–29,999 | 42 (24.00) | 40 (25.81) | 2 (10.00) | 174 (18.09) | 136 (18.50) | 38 (16.74) | |||

| $30,000–49,999 | 35 (20.00) | 32 (20.65) | 3 (15.00) | 222 (23.08) | 171 (23.27) | 51 (22.47) | |||

| ≥$ 50,000 | 18 (10.29) | 15 (9.68) | 3 (15.00) | 162 (16.94) | 144 (19.59) | 19 (8.37) | |||

| Health insurance status (Nn = 1066) | 0.13 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| No insurance | 9 (4.48) | 9 (5.00) | 0(0) | 274 (25.70) | 200 (24.57) | 74 (29.37) | |||

| Prívate | 10 (4.98) | 9 (5.00) | 1 (4.76) | 229 (21.48) | 198 (24.32) | 31 (12.30) | |||

| Medicaid | 150 (74.63) | 137 (76.11) | 13 (61.90) | 442 (41.46) | 317 (38.94) | 125 (49.60) | |||

| Medicare | 15 (7.46) | 11 (6.11) | 4 (19.05) | 12 (1.13) | 11 (1.35) | 1 (0.40) | |||

| Others | 17 (8.46) | 14 (7.78) | 3 (14.29) | 109 (10.23) | 88 (10.81) | 21 (8.33) | |||

| Homeless | 0.28 | N/A | |||||||

| Yes | 12 (5.97) | 10 (83.33) | 2 (9.52) | ||||||

| Maybe | 5 (2.49) | 4 (2.22) | 1 (4.76) | ||||||

| No | 184 (91.54) | 166 (92.22) | 18 (85.71) | ||||||

| (B) Risk behaviors and perceived risk | |||||||||

| Condomless sex with partners with FIIV or unknown FIIV status | 12 (5.97) | 10 (5.56) | 2 (9.52) | 0.36 | N/A | ||||

| STI in the last year (Np = 195; Nn = 1061) | 18 (9.23) | 15 (8.62) | 3 (14.29) | 0.42 | 156 (14.70) | 95 (11.70) | 61 (24.50) | <0.01 | 0.04 |

| Inconsistent condom use (Nn = 884) | 155 (77.11) | 143 (79.44) | 12 (57.14) | 0.03 | 769 (86.99) | 578 (86.14) | 191 (89.67) | 0.20 | <0.01 |

| >1 Sex partner (Nn = 1071) | 37 (18.41) | 30 (16.67) | 7 (33.33) | 0.08 | 579 (54.06) | 434 (52.86) | 145 (58.00) | 0.17 | <0.01 |

| Sharing needles/injection equipment (Nn = 1096) | 1 (0.50) | 1 (0.56) | 0(0) | >.99 | 53 (4.84) | 32 (3.81) | 21 (8.17) | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Sex with casual partner (s) (Nn = 1099) | 91 (45.27) | 81 (45.00) | 10 (47.62) | 0.82 | 303 (27.57) | 217 (25.83) | 86 (33.20) | 0.02 | <0.01 |

| Transactional Sex (Nn = 1087) | 3 (1.49) | 2 (1.11) | 1 (4.76) | 0.28 | 32 (2.94) | 19 (2.28) | 13 (5.10) | 0.03 | 0.34 |

| Perceived lifetime HIV risk | 0.03 | <0.01 | |||||||

| No chance | 132 (65.67) | 119 (66.11) | 13 (61.90) | 503 (47.23) | 380 (46.51) | 123 (49.60) | |||

| Low chance | 59 (29.35) | 52 (28.89) | 7 (33.33) | 459 (43.10) | 365 (44.68) | 94 (37.90) | |||

| Moderate chance | 8 (3.98) | 7 (3.89) | 1 (4.76) | 94 (8.83) | 68 (8.32) | 26 (1.48) | |||

| High chance | 2 (1.00) | 2 (1.11) | 0(0) | 8 (0.75) | 3 (0.37) | 5 (2.02) | |||

| Certainty | 0(0) | – | – | 1 (0.09) | 1 (0.12) | 0(0) | |||

| Perceived HIV risk in the next 12 months | 0.72 | 0.33 | <0.01 | ||||||

| No chance | 167 (83.08) | 150 (83.33) | 17 (80.95) | 685 (64.62) | 523 (64.33) | 162 (65.59) | |||

| Low chance | 26 (12.94) | 23 (12.78) | 3 (14.29) | 328 (30.94) | 258 (31.73) | 70 (28.34) | |||

| Moderate chance | 6 (2.99) | 5 (2.78) | 1 (4.76) | 42 (3.96) | 29 (3.57) | 13 (5.26) | |||

| High chance | 2 (1.00) | 2 (1.11) | 0(0) | 5 (0.47) | 3 (0.37) | 2 (0.81) | |||

| Certainty | 0(0) | – | – | 0(0) | – | – | |||

| (C) Awareness | |||||||||

| Previous awareness of PrEP to reduce the risk of HIV? (Nn = 1068) | 28 (13.93) | 25 (13.89) | 3 (14.29) | >.99 | 422 (39.51) | 329 (40.07) | 93 (37.65) | 0.51 | <0.01 |

| Heard about PrEP from a doctor | 7 (25.00) | 3 (13.64) | 4 (66.67) | 0.02 | 104 (24.64) | 68 (20.67) | 36 (38.71) | <0.01 | >0.99 |

| Discussion with a healthcare provider about initiating PrEP in the past 12 months (Nn = 419) | 1 (3.57) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (16.67) | 0.21 | 90 (21.48) | 53 (16.16) | 37 (40.66) | <0.01 | 0.03 |

| Received PrEP medication or a prescription for the medicine in the past 12 months | 1 (100) | 0(0) | 1 (100) | 26 (28.89) | 7 (13.21) | 19 (51.35) | <0.01 | 0.30 | |

A total of 201 observations for pregnant group (Np) were included in the analysis unless specified in the first column due to missing values.

A total of 1103 observations for non-pregnant group Nn were included in the analysis unless specified in the first column due to missing values.

Number of observation (n) with percent (%) are presented unless specified in the first column.

The p-value of statistical testing between women with and without PrEP update intention.

Pa indicates the p-value of statistical testing between pregnant and non-pregnant groups.

Information is not available for the analysis.

Behavioral risk factors

In the past year, 18 (9.2%) pregnant participants reported a sexually transmitted infection (STI) and 3 (1.5%) reported exchanging sex for drugs or money; 1 participant (0.05%) reported a recent history of injection drug use (Table 1). Women reported a median of 1 (10th percentile: 90th percentile = 1:2) sexual partners in the past 12 months; 18.4% reported >1 sexual partner. Condom use was inconsistent with both casual and main sexual partners. Only 22.9% “always” used condoms; 9 (4.5%) participants reported sex without a condom with men with unknown HIV status, and 5 (2.5%) participants reported sex without a condom with men with known HIV infection in the past year (data not shown). Consistent with national recommendations for HIV screening in pregnancy, the vast majority (81.1%) of respondents reported “definitely” or “probably” having a (negative) HIV test in the last year. There was no difference in risk factors or in the proportion of women tested for HIV by trimester.

Perceived risk of HIV

Only 4% of pregnant women surveyed reported perceived moderate to high risk of HIV acquisition in the next year; 5% reported moderate to high lifetime risk (Table 1). There was no difference in perceived risk by trimester. There was no association between the number of behavioral risk factors and perceived risk of HIV acquisition in the next year (p = 0.64) or lifetime risk (p = 0.53) by Spearman’s correlation.

Awareness of PrEP

Only 28 (13.9%) of respondents had previously heard of PrEP and those who had most frequently reported that they learned of PrEP from their physician (25%) (Figure 2). Only one participant reported having started PrEP in the past year. There was no difference in awareness of PrEP by trimester.

PrEP uptake intention

Despite low prior awareness of PrEP and low perceived risk of HIV, 10.5% (n = 21) of participants reported plans to initiate PrEP during pregnancy and 19.4% (n = 39) within the next year. There were no significant associations between PrEP uptake intention and race, age, education level, employment status, health insurance status, awareness of PrEP, or trimester (Table 1). Sex with partners with known HIV or unknown HIV status and a history of a recent STI were also not associated with PrEP uptake intention in pregnancy. Short term and/or long-term perceived risk of HIV acquisition and behavioral risk factors for HIV were not associated with PrEP uptake intention either during pregnancy or in the next 12 months (Table 1).

Though income was not associated with PrEP uptake intention during pregnancy, lower income was associated with higher PrEP uptake intention in the next 12 months (p = 0.02) (data not shown). Pregnant women with higher PrEP uptake intention during pregnancy were more likely to be single (p = 0.04) and use condoms consistently (p = 0.03).

Attitudes.

Positive attitudes towards PrEP were associated with PrEP uptake intention (p < 0.01), specifically that: PrEP is “safe” (p < 0.01), “effective” (p < 0.01) and will “make (women) feel in control of (their) health” (p < 0.01). (Table 2) The belief that taking PrEP will “protect (their) baby from HIV” was positively associated with PrEP uptake intention during pregnancy (p = 0.03). Pregnant women reported need for additional education about PrEP use in pregnancy, specifically needing more information about maternal side effects (41.29%), fetal side effects (38.81%), and safety during pregnancy (37.31%) and breastfeeding (35.82%) (Table 2). These concerns were not significantly negatively associated with PrEP uptake intention.

Table 2.

Attitudes, norms, self-efficacy and pregnancy-specific concerns by PrEP uptake intention in pregnancy

| No intention to initiate PrEP in pregnancy n (%)a (n = 180) | Intention to initiate PrEP in pregnancy n (%) (n = 21) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Attitudes | |||

| Overall, would you say that using PrEP daily to prevent HIV is a good or a bad thing? | 0.01 | ||

| Extremely bad | 8 (4.44) | 1 (4.76) | |

| Somewhat bad | 7 (3.89) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Neither good nor bad | 46 (25.56) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Somewhat good | 47 (26.11) | 1 (4.76) | |

| Extremely good | 72 (40.00) | 15 (71.43) | |

| Using daily PrEP to prevent HIV would make me feel in control of my health | <0.01 | ||

| No – Strongly disagree | 26 (14.44) | 4 (19.05) | |

| No – Somewhat disagree | 13 (7.22) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 70 (38.89) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Yes – Somewhat agree | 32 (17.78) | 6 (28.57) | |

| Yes – Strongly agree | 39 (21.67) | 9 (42.86) | |

| PrEP is a safe way to prevent HIV infection | 0.01 | ||

| No – Strongly disagree | 16 (8.89) | 4 (19.05) | |

| No – Somewhat disagree | 3 (1.67) | 1 (4.67) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 66 (36.67) | 1 (4.76) | |

| Yes – Somewhat agree | 43 (23.89) | 7 (33.33) | |

| Yes – Strongly agree | 52 (28.89) | 8 (38.10) | |

| PrEP is an effective tool to prevent HIV infection | <0.01 | ||

| No – Strongly disagree | 15 (8.33) | 2 (9.52) | |

| No – Somewhat disagree | 6 (3.33) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 67 (37.22) | 1 (4.76) | |

| Yes – Somewhat agree | 40 (22.22) | 5 (23.81) | |

| Yes – Strongly agree | 52 (28.89) | 11 (52.38) | |

| (B) Norms | |||

| Thinking about the people who are important to you – would they support or not support your using PrEP for HIV prevention in the next 12 months? | 0.08 | ||

| Strongly not support | 14 (7.78) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Somewhat not support | 14 (7.78) | 0 (0.00) | |

| They wouldnť care | 36 (20.00) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Somewhat support | 52 (28.89) | 3 (14.29) | |

| Strongly support | 64 (35.56) | 14 (66.67) | |

| Top five important people – median (10%, 90%) | |||

| Doctor | 8 (0,10) | 10 (4,10) | 0.02 |

| Children | 5.5 (−2,10) | 10 (4,10) | 0.02 |

| Main sex partner | 6 (−2,10) | 10 (2,10) | 0.12 |

| Mother | 5 (0,10) | 10 (3,10) | 0.02 |

| Sister | 4.5 (−1,10) | 10 (4,10) | <0.01 |

| Thinking about people who are similar to you – how likely would they be to use PrEP for HIV prevention in the next 12 months? | <0.01 | ||

| Extremely likely | 23 (12.78) | 14 (66.67) | |

| Somewhat likely | 49 (27.22) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Neither likely nor unlikely | 54 (30.00) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Somewhat unlikely | 29 (16.11) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Extremely unlikely | 25 (13.89) | 1 (4.76) | |

| People would shame me if they learned that I was taking PrEP | 0.57 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 97 (53.89) | 14 (66.67) | |

| Somewhat disagree | 15 (8.33) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 48 (26.67) | 3 (14.29) | |

| Somewhat agree | 11 (6.11) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Strongly agree | 9 (5.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| (C) Self-efficacy | |||

| If I really wanted to, I could use PrEP daily for HIV prevention | 0.10 | ||

| No – Strongly disagree | 14 (7.78) | 3 (14.29) | |

| No – Somewhat disagree | 5 (2.78) | 1 (4.76) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 44 (24.44) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Yes – Somewhat agree | 52 (28.89) | 3 (14.29) | |

| Yes – Strongly agree | 65 (36.11) | 12 (57.14) | |

| If I really wanted to, I could remember to take the pill every day | 0.02 | ||

| No – Strongly disagree | 14 (7.78) | 3 (14.29) | |

| No – Somewhat disagree | 15 (8.33) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 39 (21.67) | 1 (4.76) | |

| Yes – Somewhat agree | 51 (28.33) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Yes – Strongly agree | 61 (33.89) | 13 (61.90) | |

| If I really wanted to, I could take the pill every day, even if it gave me a stomachache | 0.33 | ||

| No – Strongly disagree | 41 (22.78) | 4 (19.05) | |

| No – Somewhat disagree | 33 (18.33) | 4 (19.05) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 52 (28.89) | 3 (14.29) | |

| Yes – Somewhat agree | 30 (16.67) | 4 (19.05) | |

| Yes – Strongly agree | 24 (13.33) | 6 (28.57) | |

| I know where to start the process if I want to use PrEP for HIV prevention | 0.25 | ||

| No – Strongly disagree | 22 (12.22) | 6 (28.57) | |

| No – Somewhat disagree | 12 (6.67) | 1 (4.76) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 42 (23.33) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Yes – Somewhat agree | 51 (28.33) | 5 (23.81) | |

| Yes – Strongly agree | 53 (29.44) | 7 (33.33) | |

| I could use PrEP for HIV prevention, even if my main partner didnť want me to | 0.02 | ||

| No – Strongly disagree | 20 (11.11) | 4 (19.05) | |

| No – Somewhat disagree | 7 (3.89) | 1 (4.76) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 41 (22.78) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Yes – Somewhat agree | 45 (25.00) | 3 (14.29) | |

| Yes – Strongly agree | 67 (37.22) | 13 (61.90.) | |

| I just can’t take pills | 0.08 | ||

| No – Strongly disagree | 79 (43.89) | 12 (57.14) | |

| No – Somewhat disagree | 25 (13.89) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 47 (26.11) | 1 (4.76) | |

| Yes – Somewhat agree | 18 (10.00) | 3 (14.29) | |

| Yes – Strongly agree | 11 (6.11) | 3 (14.29) | |

| (D) Pregnancy specific concerns | |||

| If I take PrEP, my baby will be protected from HIV | 0.03 | ||

| No – Strongly disagree | 18 (10.00) | 2 (9.52) | |

| No – Somewhat disagree | 5 (2.78) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 81 (45.00) | 3 (14.29) | |

| Yes – Somewhat agree | 37 (20.56) | 7 (33.33) | |

| Yes – Strongly agree | 39 (21.67) | 9 (42.86) | |

| When it comes to making a decision about your using PrEP for HIV prevention, what do you need more information about? | |||

| Side effects for me | 75 (41.67) | 8 (38.10) | 0.82 |

| Side effects for my baby | 67 (37.22) | 11 (52.38) | 0.24 |

| Safety during pregnancy | 689 (37.78) | 7 (33.33) | 0.81 |

| Safety during breastfeeding | 66 (36.67) | 6 (28.57) | 0.63 |

Number of observation (n) with percent (%) are presented unless specified in the first column.

Norms.

Perceived injunctive norms, namely perceptions of support from important others, including medical providers, partner, mother, best friend, and sister were significantly associated with PrEP uptake intention within 12 months (p < 0.01); during pregnancy this association did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.08). Perceived descriptive norms, specifically the perception that peers would be likely to initiate PrEP in the next year, were positively associated with uptake intention (p < 0.01). (Table 2) We did not find differences in associations between norms and PrEP uptake intention by trimester.

Self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy was not associated with uptake intention; we did not find differences in associations between self-efficacy by trimester. (Table 2).

Comparison with the non-pregnant sample

When we compared the socio-demographics of pregnant and non-pregnant populations, we found the non-pregnant population to be slightly older (Mean = 28.8 years; p < 0.001), with a higher proportion of Caucasians (9.6% vs 1.6%, p < 0.01), and women who identified as single (81.1% vs 51.7%, p < 0.01). Additionally, the non-pregnant population reported higher levels of education (65.5% vs 46.8% ≥12th grade/GED, p < 0.01), income (40.0% vs 30.3% household income ≥$30,000, p = 0.04), and unemployment (25.1% vs 40.8%, p < 0.01) (Table 1). The non-pregnant population reported more and different behavioral risk factors for HIV than the pregnant population (Table 1). In the non-pregnant sample, the number of behavioral risk factors for HIV was associated with perceived risk based on Spearman’s correlation (next year: rs = 0.31, p < 0.01; lifetime: rs = 0.37, p < 0.01). A significantly higher proportion of non-pregnant women were aware of PrEP compared to the pregnant sample (40%; p < 0.01). There was no difference in PrEP uptake intention in the next 12 months between the pregnant and non-pregnant samples (p = 0.24). We performed a multi-variable analysis controlling for differences in income, marital status, education, and behavioral risk factors for HIV acquisition, and found no significant differences in PrEP uptake intention in the pregnant and non-pregnant populations (aOR = 0.828; 95% CI: 0.504–1.359). There was no significant difference in perceptions of PrEP (global attitude) between the pregnant and non-pregnant samples (p = 0.40), however, non-pregnant women showed stronger agreement with the safety and effectiveness of using PrEP than pregnant women (p < 0.01)(data not shown). We did not find differences in associations between norms or self-efficacy and PrEP uptake intention between the pregnant and non-pregnant populations based on the bi-variate analysis.

Discussion

Principle findings

Despite access to and availability of PrEP in DC, very low numbers of women have initiated PrEP and even fewer have continued PrEP. This survey of pregnant women evidences low prior awareness of PrEP in conjunction with high community prevalence and demonstrable risk (i.e., behavioral; self-reported). To complicate matters, the population demonstrates low perceived risk for HIV, indicating a dire need to raise awareness of PrEP in ways that are relevant to the populations who may benefit from and want to use it. Our findings suggest that PrEP is desirable to some pregnant women. Perceptions of the safety and efficacy were over-whelmingly positive; 11% of women expressed PrEP uptake intention during pregnancy and 19% within the next year.

PrEP uptake intention was not associated with perceived risk of HIV acquisition, or demographic or behavioral differences. PrEP uptake intention was, however, associated with being single and with consistent condom use; we speculate that this association may be part of a pattern of STI/HIV prevention in this subset of women who did not perceive themselves as being in a stable relationship. The belief that PrEP would protect their fetus against HIV was associated with PrEP uptake intention during pregnancy; concerns regarding maternal or fetal side effects and safety during pregnancy or breastfeeding were not deterrents. Desire for further edification on PrEP safety in pregnancy speaks to a need for improved HIV prevention and PrEP education during prenatal care. Positive attitudes towards PrEP and supportive social norms were also associated with PrEP uptake intention. Self-efficacy was not a predictor of intention to initiate PrEP, but this may be due to high reported self-efficacy across the sample. There were no significant differences in PrEP uptake intention nor in the determinants of PrEP initiation between the pregnant and non-pregnant samples.

Results in the context of what is known

There is a dearth of published literature on the determinants of PrEP uptake intention and initiation during pregnancy, especially in resource rich settings. Consistent with the published literature in non-pregnant women (Kwakwa et al., 2016), our survey demonstrated low perceived risk of HIV acquisition relative to behavioral risk factors. Only 8% of women presenting for STI screening in Philadelphia assessed themselves to be at moderate or high risk for HIV acquisition, compared to 60% when assessed by an independent assessor (Kwakwa et al., 2016). Given the high community level prevalence and reported HIV risk factors, this finding sheds light on an important disconnect between perceived and actual HIV risk with important implications for HIV prevention practice.

PrEP was highly acceptable, but as with the broader population of US women (Bradley et al., 2019), awareness of PrEP was troublingly low. Barriers to PrEP use among non-pregnant women include lack of awareness of PrEP, low perceived HIV risk, cost, stigma, and access (Aaron et al., 2018; Auerbach et al., 2015; Bradley et al., 2019; Calabrese et al., 2018; Garfinkel et al., 2017; Goparaju et al., 2017; Kwakwa et al., 2016; Ojikutu et al., 2018; Patel et al., 2019). PrEP remains acutely underutilized, especially among women of color, who bear a disparate burden of HIV infection in the US (AIDSVu, n.d.; Smith et al., 2018). The results of this study echo these findings. We demonstrate that, when made aware of PrEP, women express positive attitudes toward PrEP and willingness to use it (Auerbach et al., 2015). Unfortunately, uptake among women remains slow and women remain under-protected, even more markedly during pregnancy.

Clinical implications

Widespread and equitably distributed awareness of the full array of HIV prevention options is critical to ending the epidemic. Critically low awareness of PrEP highlights the unmet need for HIV prevention and PrEP provision as part of routine prenatal care in high HIV prevalence communities. PrEP is known to be safe in pregnancy and PrEP uptake intention in pregnancy was not deterred by concerns for maternal or fetal safety. Pregnancy, when most women are captured in medical care and receive opt-out HIV screening, presents a unique opportunity to evaluate HIV behavioral risk and educate women about HIV prevention and PrEP – with potentially lasting protective effects. This time is an aperture for provider-initiated discussions of HIV risk and prevention. In such, there is a critical need to address environmental and structural barriers for PrEP initiation in pregnancy, such as low provider awareness and comfort with PrEP provision (Blackstock et al., 2017; Bradley et al., 2019; Castel et al., 2015; Petroll et al., 2017).

Research implications

This research highlights the importance of increasing the availability of evidence-based communication about HIV risk and prevention that resonates with this audience. Patient-provider communication is a crucial avenue to improve inequities in PrEP education and raise awareness of HIV risk that is contextually grounded.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first research that we are aware of to explore the determinants of PrEP uptake intention among pregnant women in a high HIV prevalence, US community. This exploratory study is the critical first step towards understanding and addressing women’s HIV prevention needs during a physiologically and socially vulnerable time with regard HIV risk. Still, this study is not without limitations. The relatively small number of participants (21) who planned to initiate PrEP in pregnancy restricted statistical power to draw conclusions about the determinants of PrEP uptake intentions. Additionally, as previously noted the cross-sectional design precludes relating psychosocial determinants to behavioral outcomes, substantial research, however, supports the association between intentions and behaviors (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). We did not collect data on clinical outcomes, including actual PrEP uptake. Lastly, as our study queried women in a high prevalence community in DC, results are only generalizable to similar settings.

Conclusions

Pregnancy is a critically vulnerable period of increased risk for HIV acquisition. Despite this, we found no substantive differences in the determinants of women’s willingness to use PrEP in commensurate pregnant and non-pregnant populations. The factors that matter most to women are the safety and efficacy of PrEP, and support from their social network and medical provider. During prenatal care, women are engaged in regular clinical care with a healthcare provider. As such, prenatal care is a crucial time to address HIV prevention and to educate women about PrEP and the potential role of prenatal providers in HIV prevention cannot be understated.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Patricia Moriarty, Patricia Tanjutco, and Ron Migues for their administrative support, as well as MedStar Gradulate Medical Education.

Funding

Research support was provided by MedStar Washington Hospital Center Graduate Medical Education [grant number: N/A]. The non-pregnant comparison group referenced is from an investigator-sponsored research award from Gilead Sciences [grant number: ISR-17-10227].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aaron E, Blum C, Seidman D, Hoyt MJ, Simone J, Sullivan M, & Smith DK (2018). Optimizing delivery of HIV preexposure prophylaxis for women in the United States. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 32(1), 16–23. 10.1089/apc.2017.0201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AIDSVu. (n.d.). Mapping PrEP: First ever data on PrEP users across the U.S. Retrieved November 5, 2019, from https://aidsvu.org/prep/

- Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, & Charles V (2015). Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 29(2), 102–110. 10.1089/apc.2014.0142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, Tappero JW, Bukusi EA, Cohen CR, Katabira E, Ronald A, Tumwesigye E, Were E, Fife KH, Kiarie J, Farquhar C, John-Stewart G, Kakia A, Odoyo J, … Celum C (2012). Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(5), 399–410. 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkhead GS, Pulver WP, Warren BL, Hackel S, Rodríguez D, & Smith L (2010). Acquiring human immunodeficiency virus during pregnancy and mother-to-child transmission in New York: 2002–2006. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 115(6), 1247–1255. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e00955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock OJ, Patel V. v., Felsen U, Park C, & Jain S (2017). Pre-exposure prophylaxis prescribing and retention in care among heterosexual women at a community-based comprehensive sexual health clinic. AIDS Care, 29(7), 866–869. 10.1080/09540121.2017.1286287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowser M, Young RM, Nesbitt LS, & Kharfen M (2020). Annual epidemiology & surveillance report. Data through December 2019. District of Columbia Department of Health HAHSTA. www.dchealth.dc.gov/hahsta [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E, Forsberg K, Betts JE, DeLuca JB, Kamitani E, Porter SE, Sipe TA, & Hoover KW (2019). Factors affecting pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation for women in the United States: A systematic review. Journal of Women’s Health (2002), 28(9), 1272–1285. 10.1089/jwh.2018.7353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, Dovidio JF, Tekeste M, Taggart T, Galvao RW, Safon CB, Willie TC, Caldwell A, Kaplan C, & Kershaw TS (2018). HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis stigma as a multidimensional barrier to uptake among women who attend planned parenthood. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 79(1), 46–53. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel AD, Feaster DJ, Tang W, Willis S, Jordan H, Villamizar K, Kharfen M, Kolber MA, Rodriguez A, & Metsch LR (2015). Understanding HIV care provider attitudes regarding intentions to prescribe PrEP. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 70(5), 520–528. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (n.d.). PrEP | HIV basics | HIV/AIDS. Retrieved January 16, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/prep.html

- Committee on Gynecologic Practices. (2014). Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 123(5), 1133–1136. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000446855.78026.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake AL, Wagner A, Richardson B, & John-Stewart G (2014). Incident HIV during pregnancy and postpartum and risk of mother-to-child HIV transmission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 11(2), e1001608. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M (2009). An integrative model for behavioral prediction and its application to health promotion. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-19878-008 [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, & Ajzen I (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn PM, Mirochnick M, Shapiro DE, Bardeguez A, Rodman J, Robbins B, Huang S, Fiscus SA, van Rompay KKA, Rooney JF, Kearney B, Mofenson LM, Watts DH, Jean-Philippe P, Heckman B, Thorpe E, Cotter A, Purswani M, & PACTG 394 Study Team. (2011). Pharmacokinetics and safety of single-dose tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine in HIV-1-infected pregnant women and their infants. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 55(12), 5914–5922. 10.1128/AAC.00544-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel DB, Alexander KA, McDonald-Mosley R, Willie TC, & Decker MR (2017). Predictors of HIV-related risk perception and PrEP acceptability among young adult female family planning patients. AIDS Care, 29(6), 751–758. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1234679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goparaju L, Praschan NC, Jeanpiere LW, Experton LS, Young MA, & Kassaye S (2017). Stigma, partners, providers and costs: Potential barriers to PrEP uptake among US women. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 8(9). 10.4172/2155-6113.1000730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray RH, Li X, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Brahmbhatt H, Wabwire-Mangen F, Nalugoda F, Kiddugavu M, Sewankambo N, Quinn TC, Reynolds SJ, & Wawer MJ (2005). Increased risk of incident HIV during pregnancy in Rakai, Uganda: A prospective study. The Lancet, 366(9492), 1182–1188. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67481-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groer M, El-Badri N, Djeu J, Harrington M, & van Eepoel J (2010). Suppression of natural killer cell cytotoxicity in postpartum women. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology (New York, N.Y. : 1989), 63(3), 209–213. 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00788.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapgood JP, Kaushic C, & Hel Z (2018). Hormonal contraception and HIV-1 acquisition: Biological mechanisms. Endocrine Reviews, 39(1), 36–78. 10.1210/er.2017-00103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffron R, Mugo N, Hong T, Celum C, Marzinke MA, Ngure K, Asiimwe S, Katabira E, Bukusi EA, Odoyo J, Tindimwebwa E, Bulya N, Baeten JM, & Partners Demonstration Project and the Partners PrEP Study Teams. (2018). Pregnancy outcomes and infant growth among babies with in-utero exposure to tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention. Aids (london, England), 32(12), 1707–1713. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffron R, Ngure K, Odoyo J, Bulya N, Tindimwebwa E, Hong T, Kidoguchi L, Donnell D, Mugo NR, Bukusi EA, Katabira E, Asiimwe S, Morton J, Morrison S, Haugen H, Mujugira A, Haberer JE, Ware NC, Wyatt MA, … Hendrix C (2017). Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-negative persons with partners living with HIV: Uptake, use, and effectiveness in an open-label demonstration project in East Africa. Gates Open Research, 1, 10.12688/gatesopenres.12752.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffron R, Pintye J, Matthews LT, Weber S, & Mugo N (2016). PrEP as peri-conception HIV prevention for women and men. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 13(3), 131–139. 10.1007/s11904-016-0312-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull SJ, Bowleg L, Perez C, & Sichone-Cameron M (2017). Psychosocial and environmental factors affecting Black women’s consideration of PrEP as a viable prevention tool: Implications for strategic communication abstract 4038.0. APHA. https://apha.confex.com/apha/2017/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/376849 [Google Scholar]

- Joseph Davey DL, Pintye J, Baeten JM, Aldrovandi G, Baggaley R, Bekker LG, Celum C, Chi BH, Coates TJ, Haberer JE, Heffron R, Kinuthia J, Matthews LT, McIntyre J, Moodley D, Mofenson LM, Mugo N, Myer L, Mujugira A, … John-Stewart G (2020). Emerging evidence from a systematic review of safety of pre-exposure prophylaxis for pregnant and postpartum women: Where are we now and where are we heading? Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23(1), e25426. 10.1002/jia2.25426. John Wiley and Sons Inc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating MA, Hamela G, Miller WC, Moses A, Hoffman IF, & Hosseinipour MC (2012). High hiv incidence and sexual behavior change among pregnant women in Lilongwe, Malawi: Implications for the risk of hiv acquisition. PLoS ONE, 7(6), e39109. 10.1371/journal.pone.0039109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourtis AP, Wiener J, Wang L, Fan B, Shepherd JA, Chen L, Liu W, Shepard C, Wang L, Wang A, & Bulterys M (2018). Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate use during pregnancy and infant bone health. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 37(11)2018, e264–e268. 10.1097/INF.0000000000002152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwakwa HA, Bessias S, Sturgis D, Mvula N, Wahome R, Coyle C, & Flanigan TP (2016). Attitudes toward HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in a United States urban clinic population. AIDS and Behavior, 20(7), 1443–1450. 10.1007/s10461-016-1407-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus M, Phillips G, Kuo I, Peterson J, Rawls A, West-Ojo T, Jia Y, Opoku J, & Greenberg AE (2014). HIV among women in the District of Columbia: An evolving epidemic? AIDS and Behavior, 18(3), 256–265. 10.1007/s10461-013-0514-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirochnick M, Taha T, Kreitchmann R, Nielsen-Saines K, Kumwenda N, Joao E, Pinto J, Santos B, Parsons T, Kearney B, Emel L, Herron C, Richardson P, Hudelson SE, Eshleman SH, George K, Fowler MG, Sato P, Mofenson L, & HPTN 057 Protocol Team. (2014). Pharmacokinetics and safety of tenofovir in HIV-infected women during labor and their infants during the first week of life. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 65(1), 33–41. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a921eb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mofenson LM, Baggaley RC, & Mameletzis I (2017). Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate safety for women and their infants during pregnancy and breastfeeding. AIDS, 31(2), 213–232. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moodley D, Esterhuizen TM, Pather T, Chetty V, & Ngaleka L (2009). High HIV incidence during pregnancy: Compelling reason for repeat HlV testing. AIDS, 23(10), 1255–1259. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832a5934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugo NR, Heffron R, Donnell D, Wald A, Were EO, Rees H, Celum C, Kiarie JN, Cohen CR, Kayintekore K, & Baeten JM (2011). Increased risk of HIV-1 transmission in pregnancy: A prospective study among African HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. AIDS (London, England), 25(15), 1887–1895. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834a9338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnane PM, Celum C, Mugo N, Campbell JD, Donnell D, Bukusi E, Mujugira A, Tappero J, Kahle EM, Thomas KK, Baeten JM, & Partners PrEP Study Team. (2013). Efficacy of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention among high-risk heterosexuals: Subgroup analyses from a randomized trial. AIDS (London, England), 27(13), 2155–2160. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283629037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachega JB, Uthman OA, Mofenson LM, Anderson JR, Kanters S, Renaud F, Ford N, Essajee S, Doherty MC, & Mills EJ (2017). Safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-based antiretroviral therapy regimens in pregnancy for HIV-infected women and their infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 76(1), 1–12. 10.1097/qai.0000000000001359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojikutu BO, Bogart LM, Higgins-Biddle M, Dale SK, Allen W, Dominique T, & Mayer KH (2018). Facilitators and barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among black individuals in the United States: Results from the National Survey on HIV in the Black Community (NSHBC). AIDS and Behavior, 22(11), 3576–3587. 10.1007/s10461-018-2067-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onah HE, Iloabachie GC, Obi SN, Ezugwu FO, & Eze JN (2002). Nigerian male sexual activity during pregnancy. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 76(2), 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AS, Goparaju L, Sales JM, Mehta CC, Blackstock OJ, Seidman D, Ofotokun I, Kempf MC, Fischl MA, Golub ET, Adimora AA, French AL, Dehovitz J, Wingood G, Kassaye S, & Sheth AN (2019). Brief report: PrEP eligibility among at-risk women in the Southern United States: Associated factors, awareness, and acceptability. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 80(5), 527–532. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroll AE, Walsh JL, Owczarzak JL, McAuliffe TL, Bogart LM, & Kelly JA (2017). PrEP awareness, familiarity, comfort, and prescribing experience among US primary care providers and HIV specialists. AIDS and Behavior, 21(5), 1256–1267. 10.1007/s10461-016-1625-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintye J, Baeten JM, Celum C, Mugo N, Ngure K, Were E, Bukusi EA, John-Stewart G, & Heffron RA (2017). Maternal tenofovir disoproxil fumarate use during pregnancy is not associated with adverse perinatal outcomes among HIV-infected East African women: A prospective study. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 216 (12), 1561–1568. 10.1093/infdis/jix542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvadori N, Fan B, Teeyasoontranon W, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Phanomcheong S, Luvira A, Puangsombat A, Suwannarat A, Srirompotong U, Putiyanun C, Cressey TR, Decker L, Khamduang W, Harrison L, Tierney C, Shepherd JA, Kourtis AP, Bulterys M, Siberry GK, … Kham C (2018). Maternal and infant bone mineral density 1 year after delivery in a randomized, controlled trial of maternal tenofovir disoproxil fumarate to prevent mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 144(1), 144–150. 10.1093/cid/ciy982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS 9.4 Software | SAS. (n.d.). Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://www.sas.com/en_us/software/sas9.html

- Smith DK, van Handel M, & Grey J (2018). Estimates of adults with indications for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by jurisdiction, transmission risk group, and race/ethnicity, United States, 2015. Annals of Epidemiology, 28(12), 850–857.e9. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AIDSinfo. (n.d.). Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Viread, TDF) | nucleoside and nucleotide analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors | perinatal. Retrieved October 22, 2019, from https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/3/perinatal/197/tenofovir-disoproxil-fumarate–viread–tdf-

- Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, Henderson FL, Pathak SR, Soud FA, Chillag KL, Mutanhaurwa R, Chirwa LI, Kasonde M, Abebe D, Buliva E, Gvetadze RJ, Johnson S, Sukalac T, Thomas VT, … TDF2 Study Group. (2012). Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(5), 423–434. 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson KA, Hughes J, Baeten JM, John-Stewart G, Celum C, Cohen CR, Ngure K, Kiarie J, Mugo N, & Heffron R (2018). Increased risk of female HIV-1 acquisition throughout pregnancy and postpartum: A prospective per-coital act analysis among women with HIV-1 infected partners. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 218(1), 16–25. 10.1093/infdis/jiy113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie T, Kershaw T, Campbell JC, & Alexander KA (2017). Intimate partner violence and PrEP acceptability among low-income, young black women: Exploring the mediating role of reproductive coercion. AIDS and Behavior, 21(8), 2261–2269. 10.1007/s10461-017-1767-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2017). WHO technical brief: Preventing HIV during pregnancy and breastfeeding in the context of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). http://apps.who.int/bookorders

- Yzer M (2012). The integrative model of behavioral prediction as a tool for designing health messages. In Health communication message design: Theory and practice (pp. 21–40). https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=9(5zAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA21&dq=Yzer,+M.+(2012).+The+integrative+model+of+behavioral+prediction+as+a+tool+for+designing+health+messages.+Health+communication+message+design:+Theory+and+practice,+21-40.&ots=J4qoXe [Google Scholar]