Abstract

We study the effect of the temporary closure of Danish schools as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020 on students' reported levels of well-being and test whether the effect varies among students of different socioeconomic status. To this end, we draw on panel data from the mandatory annual nationwide Danish Student Well-being Survey (DSWS) and exploit random variation in whether students answered the 2020 survey before or during the spring lockdown period. This enables us to compare reported levels of student well-being for selected measures – whether students “like school” and whether they “feel lonely” – among students in grades 6–9 to their responses from previous years. We use an event-study design with individual as well as year, month, and grade fixed effects. Our results indicate, firstly, that students' well-being with respect to liking school improved during the lockdown, even if students who answered during vs. before the lockdown were not on parallel trends in terms of previous levels of reported well-being. Secondly, school closures seemed to not affect students’ reported levels of loneliness. Thirdly, the spring lockdown might have had a more positive impact among students of lower socioeconomic status.

Keywords: COVID-19, School lockdown, Student well-being, Inequality in school, Event study

Highlights

-

•

Use of nation-wide panel data on grade 6–9 students' well-being at school.

-

•

Using timing of student responses before or during the 2020 spring lockdown.

-

•

The lockdown increased students' experience of liking school.

-

•

The lockdown did not affect students' reported levels of loneliness.

-

•

The impact was more positive for students of lower socioeconomic status.

1. Introduction

Few events in recent history have shaped education as profoundly as the COVID-19 pandemic. According to statistics from the United Nations, school closures have affected virtually all (94 percent) the world's students at all levels of education (United Nations, 2020), meaning that extended periods of online teaching or homeschooling have become regular occurrences in the lives of students across the globe. These COVID-19 induced lockdowns have led to serious concerns regarding students' academic progress and their well-being. At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic can exacerbate existing patterns of social inequalities in education (Grasso et al., 2021, p. 7). Initial studies of the effects of the spring 2020 lockdown in the Netherlands demonstrated that the learning loss due to closed schools is more pronounced among students of lower socioeconomic status (SES) (Engzell et al., 2021; Nationaal Cohort Onderzoek Onderwijs, 2021).

While most scholars would agree that students will learn less if they are taught remotely, predictions regarding the effects of school closures on students' well-being are less straightforward. On the one hand, students might enjoy that they can spend more time with their parents at home (Mondragon et al., 2021). On the other hand, prolonged levels of social isolation can be linked to increased levels of loneliness and worse mental health outcomes for school students and young adults (Bu et al., 2020; Loades et al., 2020). Most existing studies on students' well-being during the initial lockdowns have been based on cross-sectional designs without baseline measurements of students' well-being before the lockdown, which makes it difficult to gauge the impact of school closures on students’ well-being (Racine et al., 2020).

Against this background, we study the effect of the temporary closure of Danish schools in the spring of 2020 (subsequently labeled “spring lockdown”) on students’ reported levels of well-being and test whether the effect varies for students of different SES. To this end, we draw on panel data from the mandatory annual nationwide Danish Student Well-being Survey (DSWS) and exploit random variation in whether students answered the survey before or during the spring 2020 lockdown period. This enables us to compare reported levels of student well-being for selected measures – whether students “like school” and whether they “feel lonely” – among students in grades 6–9 to their responses from previous years. We use an event-study design with individual as well as year, month, and student grade fixed effects.

2. Schools and student well-being

Schools have the potential to influence students' well-being positively, as they provide an important context for students’ friendships and create opportunities for success and self-fulfillment (Graham et al., 2016; Holfve-Sabel, 2014; Konu et al., 2002). Furthermore, attending school provides students with daily routines and structure, which might be particularly supportive for students with mental health issues (Lee, 2020). However, schools can also be the cause of burnout, distress, and depression due to academic pressure and bullying (Hoferichter et al., 2021; Steinmayr et al., 2016; Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, 2013). At the negative extreme, school attendance has even been associated with increased rates of suicide, with suicide rates among students dropping during school holidays (Hansen & Lang, 2011; Plemmons et al., 2018).

Because schools can have divergent effects on student well-being, it is unclear how school closures might be expected to impact student well-being, with previous studies addressing well-being during the initials lockdowns showing mixed results. In a Danish survey-based study for example, students reported that they missed their friends and felt lonely during the spring 2020 lockdown (Wistoft et al., 2020), while a qualitative Spanish study indicated that students had mixed experiences. On the one hand they were happy to spend time with their families, but on the other hand they also missed their peers and felt lonely and deprived of fresh air (Mondragon et al., 2021). One British study suggested there had been an increase in depression symptoms among children aged 8–12 (Bignardi et al., 2020), while a Dutch study did not find any effect on children's (10–13 years old) externalizing or internalizing behavior (Achterberg et al., 2021). However, these studies have various methodological limitations, such as a reliance on cross-sectional data (Mondragon et al., 2021; Wistoft et al., 2020), limited longitudinal designs that did not adequately account for how student well-being develops with students' age and varies during the school year (Bignardi et al., 2020), or small sample size (Achterberg et al., 2021). These limitations make it difficult to evaluate the impact of the initial lockdowns on students' well-being.

In contrast to research on youth and student populations, several studies addressing the impact of the initial lockdowns on the well-being of the adult population have used larger-scale longitudinal research designs which provide a better basis for drawing causal conclusions. Nevertheless, these studies' findings echo those of studies addressing the impact on students’ well-being. Some studies found that the initial lockdowns led to reduced levels of well-being in the adult population (Ettman et al., 2020; Huebener et al., 2021; Peretti-Watel et al., 2020), while others found an improvement in well-being (Andersen et al., 2021; Recchi et al., 2020; Sachser et al., 2021). As noted by Andersen et al. (2021), a possible explanation for these differences can be related to the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic in different countries, with Denmark being at the lower end of the scale.

Given the divergent effects of schooling on students' well-being and the mixed results of previous research on the effect of the initial lockdowns on well-being among both students and adults, our first research question (R1) is: Did the spring lockdown increase or decrease students’ well-being?

2.1. Heterogeneous impact of lockdowns according to students’ SES

Previous research has established that students from more highly educated and higher-income families not only perform better in school (Jackson, 2013), they also experience “greater satisfaction with school and higher social and psychological well-being” (Loft & Waldfogel, 2021, p. 1). Multiple factors can contribute to SES gradients in school-related well-being. It can be assumed that SES differentials in academic performance will, to some degree, influence how students from different backgrounds feel about schooling given that there seems to be a reciprocal relationship between well-being at school and academic achievement (Ng et al., 2015). Research has also shown that the quality of the teacher-student relationship is strongly associated with academic outcomes (Baker, 2006; OECD, 2015) and high-SES students often experience having a more positive relationship with their teachers (Xuan et al., 2019). Furthermore, compared to their low-SES peers, high-SES students are less often the victims of bullying at school (Jansen et al., 2012; Tippett & Wolke, 2014).

Sociological research applying a so-called “seasonal” or “summer-learning” perspective has established that inequalities in student learning tend to increase when students are not in school since attending school offers low-SES students a more favorable learning environment compared to staying at home (Alexander et al., 2001; Downey et al., 2004; Downey, Alcaraz, & Quinn, 2019). Following this perspective, one can assume that high-SES parents are typically in a position to offer more parental support navigating remote schooling and thus provide a more agreeable homeschooling experience. For parents from lower-SES strata, supporting their children during the spring-lockdown might have been more difficult not least because they are less likely to have employment that allows for remote work from home. Furthermore, one can assume that the negative financial impact of the shutdown affected low-SES families to a greater degree. For example, there was a surge in unemployment due to the pandemic in March 2020 in Denmark (Styrelsen for Arbejdsmarked og Rekruttering, 2020), which low-SES families were likely more exposed to – potentially leading to negative effects for children from these families (Brand, 2015).

A contrasting perspective can be formulated based on findings from the literature examining the development of students' non-cognitive skills during the school holidays. Downey, Workman, and von Hippel (2019) found, for example, that SES-related gaps in social and behavioral skills at the start of kindergarten did not increase during school holidays. Potentially, the factors discussed above leading to an SES gradient in well-being, such as more negative interactions with teachers or bullying, might be absent or reduced when students stay at home. Furthermore, given that high-SES students spend more time on homeschooling activities than their lower-SES peers (Dietrich et al., 2020), the latter group might have more time to pursue leisure activities, which might increase their well-being. Finally, the spring lockdown did not only cause closing of schools but also of all after-school activities, such as participation in organized sports or music programs. Given SES gradients in the participation in these activities (Coulangeon, 2018; Lareau, 2011), the everyday lives of students from high-SES backgrounds might have been more disrupted by the cancellation of these activities compared to low-SES students, who were less likely to participate in the first place. Overall, the cancellation of after-school activities during the spring-lockdown might have negatively affected all students’ well-being – but potentially even more so the higher SES students. In summary, these arguments lead to the following research question (R2): Will existing SES-based differences in student well-being be magnified or reduced during the spring lockdown?

3. The Danish context

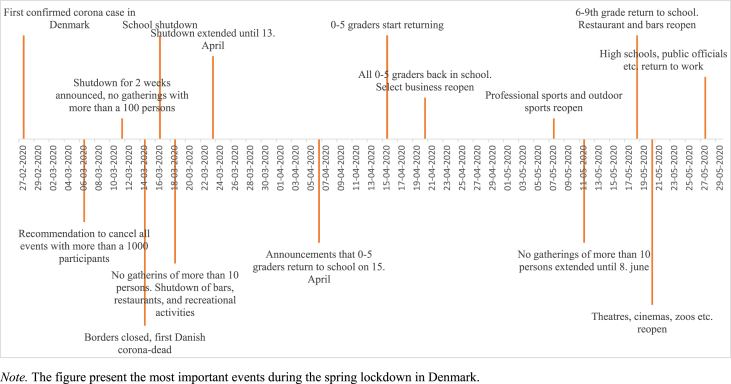

Fig. 1 presents a timeline and overview of the most important restrictions and events related to the pandemic during spring 2020 in Denmark. On March 11, a nationwide lockdown was announced in Denmark, including the closure of schools and many other public institutions – measures that were in full effect by March 16 (Statsministeriet, 2020). The Danish Government began to ease lockdown restrictions on April 15, with all students from grades 0–5 allowed to return to school by April 20. On May 18, students in grades 6–9 were also allowed back to school.

Fig. 1.

Timeline over corona-restrictions in Denmark.

While students in grades 6–9 ended up having to stay at home for nine weeks, the lockdown was initially announced as only lasting for two weeks. The repeated extensions of the restrictions might have tempered the initial negative impact on well-being, as parents and students believed they only had to stay at home for a short period. Furthermore, the school closures coincided with a closure of most public and private establishments offering leisure activities such as libraries, swimming pools, or museums, which also might have influenced students' well-being. Finally, it is important to note that, while schools and many other parts of society were locked down, small social gatherings below 10 persons were still allowed, and there was no curfew or other restrictions in terms of leaving one's residence, unlike in many other countries.

Another factor worthy of mention is that 95.4% of all households in Denmark have access to the internet (8th highest worldwide), and 93.1% of all households have a computer at home (6th highest) (OECD, 2021), providing a strong foundation for the necessary switch to online teaching and learning. It is also important to note that Denmark is an educational system with so-called “late-tracking” and all students attend compulsory school (folkeskole) together from grades 0–9 indicating that students in grades 6–9 are not sorted or streamed in different tracks.

4. Data

We combine data from the Danish Student Well-being Survey (DSWS) with the Danish administrative registers (Statistics Denmark, 2021). Data were merged using unique personal identification numbers. The DSWS is a mandatory survey for all students in public primary and lower secondary schools. The survey has been conducted annually since 2014/2015. A more limited survey is used for students in grades 0–3 compared to those attending grades 4–9. We focus on students in grades 4–9 and further restrict our sample to students in grades 6–9 in 2020 as this group was at home for nine weeks while younger students returned to school after five weeks. The survey was conducted during the spring semester, but the exact timing of the survey has varied over the years. In 2020, the first schools started conducting the survey on January 20 at the beginning of the lockdown, 75% of students had completed the survey, with 10% doing so during the lockdown and the remaining 15% after returning to school. It is important to note that there is variation across schools for the timing of the survey as each school decides when to initiate the survey; there can also be timing variation within each school as some schools stagger the timing for the different grades.

The Danish administrative registers contain detailed background information on students and their parents, providing accurate and reliable measures of parents' SES, which is preferable compared to self-reported answers. The combination of the mandatory DSWS survey and population registers provides us with information on everyone in our study population, including students who likely would not participate in a voluntary survey study. This is particularly important in the context of the lockdown, as systematic nonresponse might be more likely among students with lower levels of well-being or engagement with school. Furthermore, we can link students' annual survey responses across years and thus analyze students’ well-being trajectories.

We exclude students attending schools for students with special needs as at least some of the special needs schools were kept open during the lockdown. Furthermore, we also exclude students who are two or more years above or below the designated age for their grade, as these age values likely occur if the students are special needs students attending an integrated school (Loft & Waldfogel, 2021). Additionally, students who answered the survey after schools had reopened were also excluded. Furthermore, we exclude 10 students who answered the survey 10 weeks before all other students in 2018, and 26 students who answered several weeks later in 2017 to reduce possible bias connected to the timing of the survey in previous years. Moreover, students with missing values and students who had answered they did not want to answer the specific questions (5.7%) were also excluded. In total, we include 123,932 students in our analysis from a total sample of 179,724 students. Of the 123,932 students 14,765 answered during the lockdown, while the remaining 109,167 answered before.

4.1. Measures

4.1.1 Dependent variables. Overall, student well-being is a multidimensional concept that can be conceived of as having psychological, physical, social, material, and cognitive dimensions (Borgonovi & Pál, 2016, p. 10). The DSWS was developed to assess multiple dimensions1 of student well-being in school or relation to school, with questions such as “Are you afraid of being made fun of at school?”, “How often do you feel safe at school?” and “Have you been bullied during the current school year?” However, it can be problematic to use many of these survey questions in a situation where students are not physically attending school. Consequently, we selected two items from the DSWS that seem equally applicable in a normal situation vs. enforced homeschooling. These two items are (1) “Do you feel lonely? and (2) “Do you like your school?” We believe these two items capture central aspects of students' psychological (liking school) and social (feeling lonely) well-being. Furthermore, in recent years, loneliness has been identified as a serious public health concern that is associated with multiple negative health outcomes (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, 2018). Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that these two items are associated with each other and both capture aspects of students’ social well-being.2 All of the items used in the analysis are based on a five-point Likert scale: Liking school is coded so 1 denotes a negative response and 5 a positive response, while loneliness is reverse-coded so 1 denotes not feeling lonely and 5 denotes feeling lonely. All dependent variables are standardized to a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. Before standardization, liking school had a mean of 4.1 and a standard deviation of 0.83, the mean for loneliness was 1.8 and it had a standard deviation of 0.90.

4.1.2 The lockdown: The DSWS contains timestamps for when the students answered the survey. We assign lockdown status to students who answered the annual DSWS survey between the first official day of the lockdown, March 16, 2020, and the last day of the initial lockdown on May 18, 2020.

4.1.3 Socioeconomic status: We use data from the administrative registers concerning the mother's highest formal level of educational attainment and the parents' average disposable income. We chose mother's level of education instead of a measure based on either parent, or the father only, mainly due to a comparatively higher percentage of missing values for father's education. Mother's highest level of formal education was dummy coded as college degree/no college degree. Parents' disposable income was coded into a dummy for above or below the median.

4.2. Method

The data presented above enabled application of an event study design, which nests a difference-in-differences design. The event study design can produce a valid estimate of a causal effect when working with observational data and studying a phenomenon such as the spring-lockdown of schools in Denmark, where a randomized controlled trial was not applicable. The key identifying assumption for the event study design is that the treatment-group and control-group were on parallel trends prior to the treatment (Cunningham, 2021). In the present context, this means that the well-being of students, who answered during the lockdown, followed a similar trend compared to the students, who answered before the lockdown in the years leading up to 2020. If the treatment group and control group were not on parallel trends, any change in well-being during the lockdown can potentially be attributed to these pre-trend differences, leading to biased estimates of the effect of the lockdown on student well-being. An additional threat to validity in our approach is that individuals anticipate the treatment and change their behavior prior to the actual treatment. Parents could have elected to keep their children at home before the lockdown was set in place. However, because the lockdown measures were put into effect very suddenly in Denmark, we find it unlikely that parents preemptively kept their children at home before the announcement of the lockdown measures. We examine the change in well-being from previous years for students who answered the survey during the lockdown compared to students who answered before the lockdown. We estimate:

| (1) |

where is the outcome for student i, in grade g, in year t, and month m. The variable equals 1 if student i answered the survey during the lockdown, and 0 otherwise. measures the effect of the lockdown in 2020. measures placebo pre-treatment leads, which tests whether an effect of the treatment can be detected in previous years. If these coefficients are statistically different from each other, it indicates the treatment group and control group did not follow a similar trend prior to the lockdown. Nevertheless, the test does not guarantee parallel trends (Cunningham, 2021). The omitted category is r = 2019, the year before the lockdown. Therefore, each estimate of indicates the change in well-being relative to 2019.

The model also includes individual-level fixed effects (), year fixed effects (), month fixed effects (), and fixed effects for the grade the students attend (). The individual-level fixed effects account for observed and unobserved time-invariant characteristics of the individual, such as socioeconomic status, gender, and ethnicity. The year fixed effects account for time-varying exposure to factors that might have influenced all students' well-being in previous years irrespective of whether they answered during the lockdown. The month fixed effects control for common factors in the months that might impact students’ well-being, such as the transition from winter and early spring to late spring. is the error term. Finally, to test the existence of an SES gradient, we introduce an interaction term in the model. We test interactions with the different treatment indicators and the two variables for parental SES.

5. Analysis

5.1. Descriptive analysis

In Table 1, we compare the characteristics of students who answered before and during the spring-lockdown of schools in Denmark. Overall, the groups are very similar across the observed socio-demographic background indicators, suggesting no systematic selection bias.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Control-Group | Lockdown | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.01 |

| Immigration-status | |||

| Danish | 0.89 | 0.90 | −0.01 |

| First generation immigrant | 0.035 | 0.032 | 0.00 |

| Second generation immigrant | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Income Quartiles | |||

| 0–25 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.00 |

| 25–50 | 0.25 | 0.26 | −0.01 |

| 50–75 | 0.26 | 0.27 | −0.01 |

| 75–100 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.02 |

| Mother's highest level of education | |||

| Compulsory | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| Upper Secondary | 0.38 | 0.39 | −0.01 |

| Tertiary | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.00 |

| Higher | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| N | 109.167 | 14.765 | |

Note. The descriptive statistics are based on students, who had valid answers on the two outcomes in 2020. Tertiary education refers to short cycle or BA degrees, higher education refers to MA degrees, PhD or higher.

A key identification assumption in our study is that whether students participated in the DSWS before or during the spring lockdown was random. While the students themselves did not decide when to take part in the survey, their schools did. In Table 2, we examine the timing of survey participation in previous years for the lockdown and control groups. A slightly larger percentage of students who answered during the lockdown in 2020 answered during the last month in 2018 and 2019 than was the case for the control group. We also report Spearman's rank-order correlations to test how the timing of schools participating in the survey correlates between years (Table 3). As students within the same schools do not answer at the same time, we use the mode for each school for each year to identify the week where the most students answered the survey at the given school. The results presented in Table 3 show relatively weak correlations in terms of survey timing between years. Overall the results reported in Table 2, Table 3 do not suggest a systematic pattern in the timing of survey participation. This leads us to believe that the timing of survey participation in 2020 was more or less random.

Table 2.

Timing of answers in previous years.

| 2015 | Control | Lockdown | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| February | 0.35 | 0.38 | −0.03 |

| March |

0.62 |

0.60 |

0.02 |

| 2016 | |||

| January | 0.13 | 0.14 | −0.01 |

| February | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.01 |

| March | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.00 |

| April |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

| 2017 | |||

| January | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| February | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.01 |

| March |

0.57 |

0.59 |

−0.02 |

| 2018 | |||

| March | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.0 |

| April | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.04 |

| May | 0.48 | 0.53 | −0.05 |

| June |

N/A |

N/A |

|

| 2019 | |||

| May | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.05 |

| June | 0.37 | 0.42 | −0.05 |

Note. A few students answered in June 2018, but the numbers are too small to report for some groups.

Table 3.

Rank-correlation between timing of DSWS survey answers across years.

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 1 | |||||

| 2016 | 0.13 | 1 | ||||

| 2017 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 1 | |||

| 2018 | 0.016 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1 | ||

| 2019 | 0.013 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1 | |

| 2020 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 1 |

Note. Based on mode survey answers for each school.

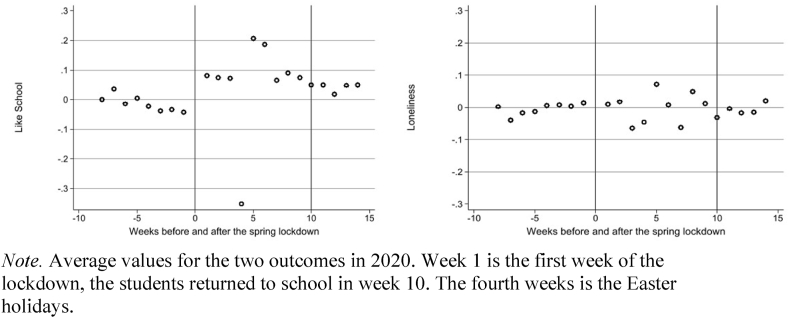

Fig. 2 illustrates trends for the two outcomes liking school and feeling lonely throughout the spring of 2020. We see that liking school was trending slightly downwards before the spring lockdown. After the lockdown, there was a sharp increase in levels of liking school among student responses, which remained stable during the first three weeks of the lockdown. The fourth week of lockdown corresponded with the 2020 Easter holiday, which could explain the very low level in this week, with students likely to have been displeased at having to perform a school-related task during their holidays. The much higher levels of liking school among student responses in weeks 5 and 6 may have been ‘boosted’ by students having enjoyed their holidays, but could also be attributable to statistical noise given the comparatively low N in this period.3 There was a return to a level of liking school similar to the first three weeks after the lockdown.

Fig. 2.

Development of liking school and loneliness in 2020.

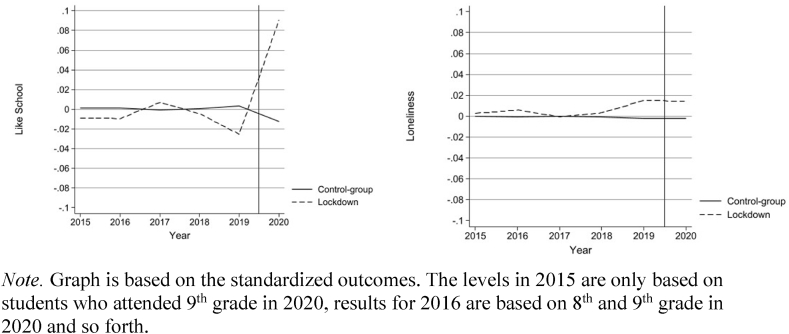

Fig. 3 presents trends for how the two outcomes from 2015 to 2020 for both the lockdown and control groups developed. For both outcomes, the levels for the control group are relatively stable. However, for the lockdown group, a slight downward trend for liking school can be observed from 2017 to 2019. For 2020, we see a sharp reversal of this trend, with students who answered the survey during the lockdown period reporting higher levels of liking school. The reported levels of loneliness for the lockdown group varied over time, which indicates some noise in the measurement, and the change in 2020 does not exceed swings in some of the previous years.

Fig. 3.

Trends in outcomes.

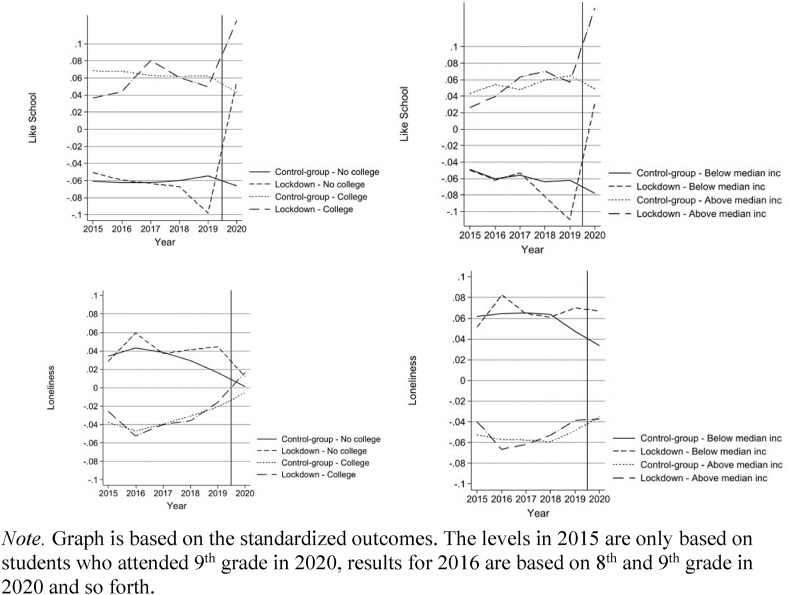

Next, we examine the development of students' well-being across students’ SES (Fig. 4). The figure shows a considerable stable SES gradient for both outcomes across time. Students with lower SES in both the lockdown group and the control group consistently report lower levels of well-being in previous years than students in the high-SES group. The results for liking school are similar to the overall trends across both SES measures, with a downward trend prior to 2020 for the lockdown-group, and a strong increase in 2020. The increase in liking school seems to be larger for students with less educated mothers and for students from below-median income households, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Trends in outcomes by parental SES.

For loneliness, there is a relatively stable difference between students whose parents have income below the median and students whose parents have income above the median across years, which persists into 2020. For students from the no-college group, loneliness was somewhat downward trending, while students with college-educated mothers were trending upward. These two trends persist into 2020 but are stronger for the lockdown students.

5.2. Event study analysis of the spring lockdown

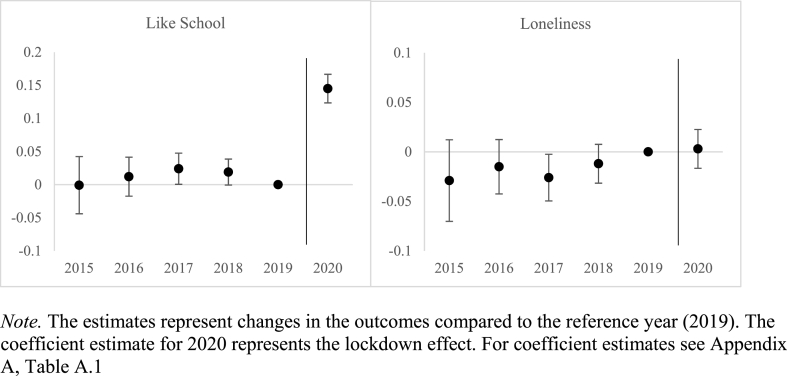

In Fig. 5, the results of the event study are presented, with the figure showing how students’ well-being differed compared to the reference year (2019), both in previous years and during the lockdown.

Fig. 5.

Event study estimates with 95% confidence intervals.

The figure shows that the students reported slightly higher levels of liking school in 2017 and 2018 compared to the 2019 level, suggesting a downward trend consistent with the trends depicted in Fig. 3. Concerning student loneliness, the results show a statistically significant lower level in 2017. Overall, the event study indicates that the groups were not on a parallel trend before the school closures, meaning that the estimates of the lockdown's effect on the outcomes are likely biased. Nevertheless, the analysis shows a sharp increase in reported levels of liking school during the lockdown period that far exceeds the observed difference in prior levels. No such change was found for student loneliness.

5.2.1. Robustness checks

In addition to including leads in the model to test the parallel trends assumption, we perform three further analyses to address the robustness of our findings. First, we create a placebo treatment group in both 2019 and 2018, testing if students, who answered the survey at a similar time as the lockdown group in 2020 experience a change in their well-being. The use of a placebo treatment group is considered a credible approach to addressing the validity of findings in an event-study design (Cunningham, 2021). Because the timing of the DSWS survey varied across years, we define the placebo treatment groups with respect to the relative timing of answering the survey. Using 2020 as a reference we define the first 75% of students who answered the survey to be the placebo control group and those who answered in the interval from 75% to 85% as the placebo lockdown group while the last 15% (the post lockdown group) are dropped. Finding an effect for the actual lockdown, but also the placebo treatment group, would suggest that a lockdown effect could be attributed to other unobserved factors related to the timing of the survey, such as increased exposure to hours of sunlight or the summer holidays coming closer. The placebo analysis is presented in Appendix B and shows no statistically significant change for these two placeboes treatments. However, the placebo treatment group in 2019 shows non-parallel trends concerning student loneliness and the placebo treatment group in 2018 shows non-parallel trends for liking school. The fact that we do not find any change for the placebo treatment groups provide some credibility to the validity of our findings. The fact that we also find non-parallel trends in previous years for the placebo could indicate that the difference in trends can be attributed to noisy measurement rather than the lockdown group being systematically different from the control group.

Second, we reduce the dataset to schools (516 out of 1288) where some of the students answered during the lockdown and others before. Our motivation for doing this is to address a potential bias related to the fact that schools that decide to initiate the survey later than other schools might differ on unobserved factors, which interact with students' well-being. Results of this analysis indicate a similar change in students’ reported levels of liking school (Appendix C). Furthermore, the results no longer indicate non-parallel trends. The replication of the increase in liking school provides further credibility to the results of our overall analysis. Taken together, the two robustness checks indicate that the non-parallel trends might have not only been due to noise in our measurements but also applicable to some school-level factors.

Third, another potential limitation of the presented analysis is that students who answered during the lockdown interpret the question regarding ‘liking school’ not with reference to the current situation but retrospectively, e.g. with a pre-lockdown situation in mind. Alternatively, students who indicated that they like school during the spring lockdown might simply have missed attending regular school. We, therefore, test the effect of the spring lockdown on two indicators of students' somatic complaints that are also included in the DSWS survey and that might be less susceptible to retrospective reporting biases: Students' reports of headaches and stomach pains, both of which might be expected to increase in cases where students feel stressed or unwell (Dooley et al., 2005; Shapiro & Nguyen, 2010). The results are reported in Appendix D and suggest a reduction in the frequency of reports concerning both headaches and stomach pains during the spring lockdown. This, in turn, suggests that the positive effect of the spring lockdown on students' reported levels of liking school seems to be a valid finding not affected by students' (mis)understanding of the survey question.

5.3. SES differentials

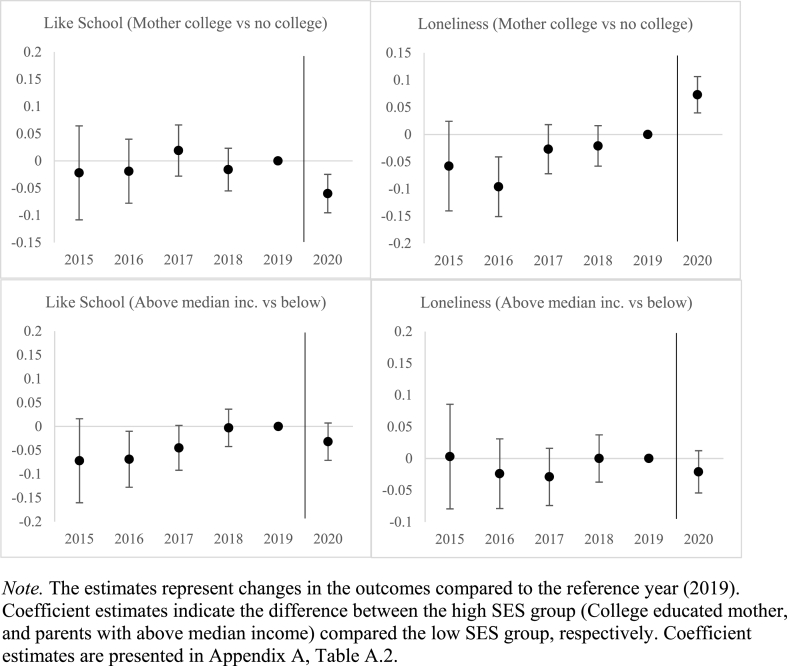

While bivariate results presented in Fig. 4 indicated that students from lower SES origins seem to have experienced relatively larger gains in liking school, we now provide parametric tests of possible differences between the SES groups in the event study framework.

Starting with the mother's level of education, results reported in Fig. 6 suggest that students in the lockdown and control groups whose mothers have a college degree were on parallel trends prior to 2020 concerning whether they reported liking school. For students' reported levels of loneliness, there is an indication that students in the lockdown and control group whose mothers have a college degree were not on parallel trends as the lockdown group had a statistically significant lower level in 2016 compared to their 2019-level. However, the statistically significant difference for loneliness occurs only in 2016, perhaps suggesting that the lockdown and control groups were more similar in the years closer to 2020. While the results suggest parallel trends, the statistical power of the analysis is also reduced as we are looking at smaller groups, leading to larger standard errors for each year.

Fig. 6.

Event study estimates for different socioeconomic status with 95% confidence intervals.

The results in Fig. 6 show a lower reported level of liking school and a higher reported level of loneliness in 2020 for students whose mothers have a college degree. To be more precise, the results suggest that the lockdown's overall positive effect on liking school was weaker for students with college-educated mothers than for students with non-college-educated mothers. Furthermore, the results suggest that students with college-educated mothers felt lonelier during the lockdown compared to students whose mother did not have a college degree.

For parental income, we found no difference in the lockdown's impact whether above or below the median at the 5% significance level.

In Appendix E, we replicate the results with more fine-grained definitions of SES. Overall, the findings are largely the same. Interestingly, the results show that the differentials reported above for students' mothers' educational attainment are primarily driven by students whose mothers have a master's degree or higher. This finding suggests that students with highly educated mothers, who potentially participate in many after-school activities compared to their less privileged peers, experienced the largest disruption of their everyday life. Alternatively, we cannot rule out that ceiling effects also play a role here as this privileged group of students already had high levels of well-being to begin with and thus less room for improvements in well-being compared to their lower SES peers.

6. Discussion

Our findings add to a growing body of research concerned with the well-being of school students during the time of extended school closings during the Covid-19 pandemic. Our results suggest an increase in students' reported levels of liking school during the spring lockdown even though those students who answered the survey during the spring lockdown period seem to differ from those who answered before the lockdown in terms of their responses in previous years – violating the parallel trends assumption. However, the results of a number of robustness analyses did not suggest systematic differences between our treatment and control group which would invalidate the finding that levels of liking school increased during the spring-lockdown. No systematic effects emerged concerning students' reported levels of loneliness. Furthermore, the results indicate that the spring lockdown did not magnify inequalities in students’ well-being. We even found a slightly less positive impact for students with more educated mothers compared to students with less-educated mothers even if this finding must be interpreted with caution due to the possibility of ceiling effects.

One central concern in relation to the analysis is that the items we selected might be insufficient or incomplete to capture students' well-being during the period of school closures. However, given that additional analysis based on students' reported somatic complaints follows the same pattern, i.e. pointing towards increased well-being during the spring lockdown, the chosen indicators seem to have sufficient validity. This does not preclude that other aspects of students’ well-being were more affected during the lockdown, such as missing their friends (Wistoft et al., 2020).

As noted, the lockdown measures implemented during spring 2020 in Denmark were less restrictive than in many other countries; for example, small social gatherings were still allowed and no curfew was in force. Furthermore, infection and mortality rates, even during the first wave in spring 2020, were relatively moderate from an international comparative perspective. It follows that studies of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on students' – or the general population's – well-being need to be situated in their geographical and temporal context. Denmark seems to be a country where the spring 2020 lockdown did not lead to a drastic decrease in students' or adults' well-being.

Another central issue related to our finding is how the observed increase in students' well-being, in terms of liking school can be reconciled with the emerging literature on learning losses related to school closings and remote schooling during the Covid-19 pandemic. Numerous studies have established that well-being at school is positively related to student learning (Gibbons & Silva, 2011; Hampden-Thompson & Galindo, 2017). A possible learning loss due to the nine weeks of homeschooling for grade 6–9 students, might thus have been attenuated by the fact that students' well-being did not decrease – or even increased during that time. Another possibility is that the established relationship between well-being at school and student learning cannot be transferred to the context of homeschooling. Potentially, the factors leading to an increase in students’ well-being – such as having more free time – are also the factors leading to learning losses, which are more concentrated among lower-SES students (Engzell et al., 2021).

Ethics approval statement

The data was anonymized and de-identified by Statistics Denmark before it was made available to the researchers. Under Danish law the data can be used for research purposes by individuals affiliated with a Danish research institution, without the need for ethical approval of the specific study.

Author statement

Simon Skovgaard Jensen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Revisions.

David Reimer: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Revisions.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jesper Fels Birkelund, Jesper Eriksen, Christopher Ozuna and Emil Smith for valuable comments on previous drafts of this paper.

This work was partially supported by the Velux Foundation, Denmark (Grant No 00017032) as well as the Lifetrack project, which is part of the NORFACE Joint Research Programme on Dynamics of Inequality Across the Life-course, which is co-funded by the European Commission through Horizon 2020 (grant agreement No 724363).

The founding sources had no involvement in the present study.

Footnotes

The DSWS includes items with the goal of measuring the following dimensions of students' well-being: Social well-being, academic well-being, support and inspiration, and disciplinary climate (in Danish “ro and orden”) (Ministry of Children and Education, 2016).

Niclasen et al. (2018) provide a detailed psychometric analyses of the DSWS items and found, that “liking school” and “feeling lonely” load on the same factor which they label “school connectedness”.

The number student responses were distributed the following way across the 9 lockdown weeks: Week 1: 6,024, Week 2: 1,213, Week 3: 590, Week 4: 15, Week 5: 220, Week 6: 298, Week 7 177, Week 7: 2,478, Week 9: 3750.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100945.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Achterberg M., Dobbelaar S., Boer O.D., Crone E.A. Perceived stress as mediator for longitudinal effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on wellbeing of parents and children. Scientific Reports. 2021;11(1):2971. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81720-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander K.L., Entwisle D.R., Olson L.S. Schools, achievement, and inequality: A seasonal perspective. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 2001;23(2):171–191. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen L.H., Fallesen P., Bruckner T.A. Risk of stress/depression and functional impairment in Denmark immediately following a COVID-19 shutdown. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):984. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11020-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J.A. Contributions of teacher-child relationships to positive school adjustment during elementary school. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;44(3):211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Bignardi G., Dalmaijer E.S., Anwyl-Irvine A.L., Smith T.A., Siugzdaite R., Uh S., Astle D.E. Longitudinal increases in childhood depression symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2020;106(8):791–797. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgonovi F., Pál J. A framework for the analysis of student well-being in the PISA 2015 study : Being 15 in 2015. OECD Education Working Papers. 2016;140 [Google Scholar]

- Brand J.E. The far-reaching impact of job loss and unemployment. Annual Review of Sociology. 2015;41(1):359–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu F., Steptoe A., Fancourt D. Social science & medicine loneliness during a strict lockdown : Trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38 , 217 United Kingdom adults. Social Science & Medicine. 2020;265(November):113521. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J.T., Cacioppo S. The growing problem of loneliness. The Lancet. 2018;391(10119):426. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulangeon P. The impact of participation in extracurricular activities on school achievement of French middle school students: Human capital and cultural capital revisited. Social Forces. 2018;97(1):55–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham S. Causal inference: The mixtape. Yale University Press; 2021. Difference-in-differences; pp. 406–510. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich H., Patzina A., Lerche A., Lerche A. Social inequality in the homeschooling efforts of German high school students during a school closing period. European Societies. 2020:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley J.M., Gordon K.E., Wood E.P. Self-reported headache frequency in canadian adolescents: Validation and follow-up. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2005;45(2):127–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey D.B., Alcaraz M., Quinn D.M. The distribution of school quality : Do schools serving mostly white and high-SES children produce the most learning. Sociology of Education. 2019;92(4):386–403. [Google Scholar]

- Downey D.B., von Hippel P.T., Broh B.A. Are schools the great equalizer? Cognitive inequality during the summer months and the school year. American Sociological Review. 2004;69(5):613–635. [Google Scholar]

- Downey D.B., Workman J., von Hippel P. Socioeconomic, ethnic, racial, and gender gaps in children's social/behavioral skills: Do they grow faster in school or out? Sociological Science. 2019;6:446–466. doi: 10.15195/v6.a17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engzell P., Frey A., Verhagen M.D. Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021;118(17):1–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2022376118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettman C.K., Abdalla S.M., Cohen G.H., Sampson L., Vivier P.M., Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(9) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons S., Silva O. School quality, child wellbeing and parents ’ satisfaction. Economics of Education Review. 2011;30(2):312–331. [Google Scholar]

- Graham A., Powell M.A., Truscott J. Facilitating student well-being: Relationships do matter. Educational Research. 2016;58(4):366–383. [Google Scholar]

- Grasso M., Klicperová-baker M., Koos S., Kosyakova Y., Petrillo A., Vlase I. The impact of the coronavirus crisis on European societies . What have we learnt and where do we go from here ? – introduction to the COVID volume. European Societies. 2021;23(sup1):S2–S32. [Google Scholar]

- Hampden-Thompson G., Galindo C. School-family relationships, school satisfaction and the academic achievement of young people. Educational Review. 2017;69(2):248–265. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen B., Lang M. Back to school blues : Seasonality of youth suicide and the academic calendar. Economics of Education Review. 2011;30(5):850–861. [Google Scholar]

- Hoferichter F., Hirvonen R., Kiuru N. The development of school well-being in secondary school : High academic buoyancy and supportive class- and school climate as buffers. Learning and Instruction. 2021;71(July 2020):101377. [Google Scholar]

- Holfve-Sabel M.A. Learning, interaction and relationships as components of student well-being: Differences between classes from student and teacher perspective. Social Indicators Research. 2014;119(3):1535–1555. [Google Scholar]

- Huebener M., Waights S., Siegel N.A., Wagner G.G., Spiess C.K. Parental well-being in times of Covid-19 in Germany. Review of Economics of the Household. 2021;19(1):91–122. doi: 10.1007/s11150-020-09529-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M. In: Determined to succeed? Performance, choice and education. Jackson M., editor. Stanford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen P.W., Verlinden M., Berkel A.D., Mieloo C., Ende J. Van Der, Veenstra R., Verhulst F.C., Jansen W., Tiemeier H. Prevalence of bullying and victimization among children in early elementary school: Do family and school neighbourhood socioeconomic status matter. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konu A.I., Lintonen T.P., Rimpelä M.K. Factors associated with schoolchildren's general subjective well-being. Health Education Research. 2002;17(2):155–165. doi: 10.1093/her/17.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A. 2nd ed. University of California Press; 2011. Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. with an update a decade later. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Reflections features mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health. 2020;4(6):421. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loades M.E., Chatburn E., Higson-Sweeney N., Reynolds S., Shafran R., Brigden A., Linney C., Niamh McManus M., Borwick C., Crawley E. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loft L., Waldfogel J. Socioeconomic Status gradients in young children's well‐being at school. Child Development. 2021;92(1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Children and Education . 2016. Metodenotat: Beregning af indikatorer i den nationale trivselsmåling i folkeskolen. [Google Scholar]

- Mondragon N.I., Sancho N.B., Dosil M., Munitis A.E. Struggling to breathe : A qualitative study of children ’ s wellbeing during lockdown in Spain. Psychology and Health. 2021;36(2):179–194. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2020.1804570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nationaal Cohort Onderzoek Onderwijs . 2021. Minder leergroei door eerste schoolsluiting. Report.https://www.nationaalcohortonderzoek.nl/uploads/2021/03/poster_minder_leergroei_covid19_crisis.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ng Z.J., Huebner S.E., Hills K.J. Life satisfaction and academic performance in early adolescents : Evidence for reciprocal association. Journal of School Psychology. 2015;53(6):479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niclasen J., Keilow M., Obel C. Psychometric properties of the Danish student well-being questionnaire assessed in >250,000 student responders. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2018;46(8):877–885. doi: 10.1177/1403494818772645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD Do teacher-student relations affect student's well-being at school? PISA in Focus. 2015;(April):1–4. 04. [Google Scholar]

- OECD 2021. Internet access (indicator) [DOI]

- Peretti-Watel P., Alleaume C., Léger D., Beck F., Verger P. Anxiety, depression and sleep problems: A second wave of COVID-19. General Psychiatry. 2020;33(5):1–4. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plemmons G., Hall M., Stephanie D., Gay J., Brown C., Browning W., Casey R., Freundlich K., Johnson D.P., Lind C., Rehm K., Thomas S., Williams D. Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008–2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine N., Korczak D.J., Madigan S. Evidence suggests children are being left behind in COVID-19 mental health research. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01672-8. 0123456789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recchi E., Ferragina E., Helmeid E., Pauly S., Safi M., Sauger N., Schradie J. Research in social stratification and mobility the “ Eye of the Hurricane ” paradox : An Unexpected and unequal rise of well-being during the Covid-19 lockdown in France. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 2020;68(May):100508. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachser C., Olaru G., Pfeiffer E., Brähler E., Clemens V., Rassenhofer M., Witt A., Fegert J.M. The immediate impact of lockdown measures on mental health and couples' relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic - results of a representative population survey in Germany. Social Science & Medicine. 2021;278:113954. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro M.A., Nguyen M.L. Psychosocial stress and abdominal pain in adolescents. Mental Health in Family Medicine. 2010;7:65–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Denmark Data for research. 2021. https://www.dst.dk/en/TilSalg/Forskningsservice August 25.

- Statsministeriet . 2020. Pressemøde om COVID-19 den 11. marts 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmayr R., Crede J., McElvany N., Wirthwein L. Subjective well-being, test anxiety, academic achievement: Testing for reciprocal effects. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;6(JAN):1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styrelsen for Arbejdsmarked og Rekruttering . Aktuel overvågning af situationen på arbejdsmarkedet. Status søndag den 10. maj 2020. (Issue april) Styrelsen for Arbejdsmarked og Rekruttering; 2020. Aktuel overvågning af situationen på arbejdsmarkedet. [Google Scholar]

- Tippett N., Wolke D. Socioeconomic status and bullying: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(6):48–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . 2020. Education during COVID-19 and beyond (UN policy briefs) 26. [Google Scholar]

- Upadyaya K., Salmela-Aro K. Development of school engagement in association with academic success and well-being in varying social contexts: A review of empirical research. European Psychologist. 2013;18(2):136–147. [Google Scholar]

- Wistoft K., Christensen J.H., Qvortrup L. Elevernes trivsel og mentale sundhed - hvad har vi lært af nødundervisningen under coronakrisen. Learning Tech – Tidsskrift for Læremidler, Didaktik Og Teknologi. 2020;5(7):40–65. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan X., Xue Y.I., Zhang C., Luo Y., Jiang W., Qi M., Wang Y. Relationship among school socioeconomic status, teacher-student relationship, and middle school students' academic achievement in China: Using the multilevel mediation model. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.