Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization, the United States Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, the Food and Drugs Administration, and the Centers for Disease Control recommend COVID-19 vaccination to lactating mothers without discontinuity of breastfeeding. Despite this recommendation, willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine and its determinant factors among lactating mothers were not studied in Ethiopia. Hence, this study aimed to assess willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine and its determinant factors among lactating mothers in Ethiopia.

Methods

An institutional-based cross-sectional study design was employed in southern Ethiopia from February 1 up to March 15, 2021. Multistage sampling technique was used to select study participants. Structured and face-to-face interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. Data were clean, coded, and entered into Epi-Data version 4.2.0 and exported to SPSS version 23 software package for analysis. Bivariable and multivariable analysis were used to identify associated factors. Adjusted odds ratio along with 95% CI was used to measure the strength of association.

Results

The prevalence of willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination was found to be 61% (95% CI; 56.9–65.1%). Urban residence [AOR=2.5, (95% CI; 1.62–3.91)], having secondary and above maternal educational status [AOR=2.8, (95% CI; 1.51–4.21)] mothers who had got immunization counselling [AOR=3.4, (95% CI; 1.95–5.91)], good knowledge about vaccine [AOR=2.6, (95% CI; 1.84–3.47)], and good adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures [AOR=3.2, (95% CI; 1.91–5.63)] were determinant factors of willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine.

Conclusion

Urban residence, secondary and above maternal education status, immunization counselling, good knowledge about the vaccine, and good adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures were determinant factors of willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine. Therefore, health professionals should counsel about the merits of COVID-19 vaccination, and enhance maternal awareness about the vaccine is recommended.

Keywords: willingness, lactating mothers, COVID-19 vaccine, determinant factors, Ethiopia

Introduction

The newly emerged coronaviruses disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, was first detected in China, in December 2020.1 The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 as a global pandemic on 11 March 2020.2 As of 28 May 2021, COVID-19 infects 168,599,045+ confirmed cases, 545,102+ new cases, and 3,507,477+ deaths were reported globally.3 In Ethiopia, as of September 2021, COVID-19 infects 339,658+ and 5,331+ deaths were reported.4

As of March 1, 2021, in the United States alone 73,600+ infections and 80+ maternal deaths were reported among infected pregnant women.5 COVID-19 has negatively affected the pregnancy outcome by increasing the risk for preterm birth, the risk of intensive care unit admission by 3 times, mechanical ventilation by 2.9 times, and death by 1.7 times higher among COVID-19 infected pregnant mothers compared to uninfected pregnant mothers.6,7

To date, more than 2.01 billion doses of vaccines have been administered globally.8 In Ethiopia, as of 22 September 2021, a total of 3,281,470+ vaccine doses have been administered.4 Several international guidelines9–13 recommend COVID-19 vaccine (ie Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, Astra Zeneca, and Janssen vaccine)14–17 to lactating women without discontinuity of breastfeeding. Evidence showed that COVID-19 vaccination generated robust immunity (IgA antibody and IgG antibody) in pregnant and lactating women.18,19 Serious adverse events after COVID-19 vaccination were not reported in lactating women.19 However, a study conducted by Kerri Bertrand and his colleagues reported that >85% of participants develop minor local symptoms.20

Vaccine hesitancy is one of the top ten global health traits. It is defined as a delay in acceptance or refusal of receiving vaccination despite the availability of the vaccine.21 A systematic review conducted on vaccine hesitancy showed that the highest vaccine acceptance rate >90% was reported in Ecuador, Malaysia, Indonesia, and China.22,23 Likewise, the lowest acceptance rate 23.6% to 54.9% was reported in Kuwait, Jordan, Italy, and Russia.22 Thus, vaccine hesitancy becomes an obstacle to global and national efforts to escalate the COVID-19 transmission.22 Concern about vaccine’s side effects and risks, lack of vaccine knowledge effectiveness of the vaccine, and spreading of misinformation in social media were factors that increase vaccine hesitancy.23,24

Although lactating mothers were recommended to receive COVID-19 vaccination, studies regarding willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine and its determinant factors were not studied in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study aimed to assess willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination and its determinant factors among lactating mothers in Southern Ethiopia. The finding of this study will have paramount importance for health care workers, policy makers, and the Ethiopia COVID-19 vaccination program that can be used to inform local communications campaigns.

Methods and Materials

Study Design, Area, and Period

An institutional-based cross-sectional study design was employed among selected lactating mothers in Southern Ethiopia from February 1 up to March 15, 2021. Gurage zone is found 153 km southwest of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. It is one of the zones in the southern part of Ethiopia. It has 13 districts and Wolkite town is the administrative centre of the Zone. Report from the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA) in 2007, this Zone has a total population of 1,279,646, of whom 622,078 are men and 657,568 women. There are six hospitals, 72 health centre, and 402 health posts that provide health care services for the general population. According to the main Ethiopian Mini Demographic and Health Survey report in 2019, 69.4% of mothers had at least one antenatal care visit, 47.6% of a mother gave birth at a health institution and 32% of mothers had postnatal care follow-up, in Southern Nation Nationalities and Peoples region.25

Source Population and Study Population

All lactating mothers attending immunization clinics in selected hospitals were considered as source population. All lactating mothers attending immunization clinic and who were selected using systematic random sampling techniques during the data collection period were considered as the study population.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All lactating mothers attending immunization clinics at selected hospitals during data collection period were included. Lactating mothers who were critically ill and unable to respond during the study period were excluded.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedure

The required sample size for this study was determined using a single population proportion formula by considering the following assumption; the proportion of lactating mothers willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination (p= 50%, since there was no published evidence on lactating mothers during the development of the proposal), a margin of error (d=5%), at 95% CI (Zα/2=1.96), design effect 1.5, and 10% of the non-respondent rate. The final sample size was 633 for this study. Multistage sampling technique was used. Gurage Zone has a total of six hospitals namely Bue Hospital, Atat Hospital, Butajira Hospital, Quantie Hospital, Wolkite University Hospital, and Gunchire Hospital. By using a simple random sampling technique, 3 hospitals were selected (ie Atat Hospital, Butajira Hospital, Wolkite University Hospital). Secondly, in the secondary stage expanded program of immunization (EPI) registration book was used as a sampling frame. A sample size of 630 study participants was selected using a systematic random sampling technique. Proportional allocation was used for each selected hospital to withdraw study participants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of sampling procedure.

Data Collection Tools and Data Collection Procedure

The questionnaires were adopted after reviewing relevant literature on the problem under study.26–29 The tool was first prepared in the English language and translated to the Amharic language by language experts and then back to the English language to maintain its consistency. The questionnaire was divided into four parts: firstly, socio-demographic characteristics; secondly; knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine; thirdly, attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination; fourthly, adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures, and lastly willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination if it becomes available. A total of 10 health professionals; 9 BSc midwife undergraduate data collectors and 1 MSc holder supervisor participated in the data collection process. Data collectors and supervisor were informed to follow the WHO COVID-19 infection mitigation protocols such as wearing a face mask, maintaining physical distancing, and using hand sanitizer during data collection time.

Data Quality Control

To ensure the quality of data, three days (two days theoretical and one day practical) training was given for both data collectors and supervisor on the objective of the study, on data collection processes such as on respondent rights, informed consent, and technique of interview. The principal investigator was closely following the data collection process throughout the data collection period. A pretested, structured, and face-to-face interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. A pre-test of the questionnaires (5%) was done in non-selected hospitals of similar study participants. Necessary modification was done on the questionnaires before the actual data collection period based on the finding of pre-test results. Every day after data collection, supervisor was reviewed data, checked for completeness, accuracy, and clarity.

Study Variables and Measurements

Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine: It is defined as those mothers who had responded “Yes” for a question “Do you accept COVID-19 vaccination if it is available right now?” coded as “0” and those who responded “No” were considered as vaccine hesitancy and coded as “1”.29

Adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures: Those mothers who practiced more than or equal to 80% of COVID-19 infection mitigation measures practice-related questions correctly were interpreted as having good adherence whereas those mothers who had responses less than 80% was interpreted as having poor adherence.30

Knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine: Those mothers who had scored less than 70% of knowledge related items were coded as poor knowledge and those who had scored greater than or equal to 70% were coded as good knowledge.31

Attitude towards the COVID-19 vaccine: Attitude is the way lactating mothers view the COVID-19 vaccine. Those mothers who had scored less than 70% were coded as an unfavourable attitude and those who had scored greater than or equal to 70% were coded as favourable attitude.31

Data Processing and Analysis

All the questionnaires were checked manually for completeness, then entered into Epi-Data version 4.2.0, and exported to SPSS version 23 software package for further analysis. Descriptive analysis results were presented in the form of tables, figures, and pie charts. Text using frequencies and summary statistics such as mean, standard deviation, and percentage were used. In this study, the outcome variable was a willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine. For the independent variables, comprehensive knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine was computed from summing up all relevant knowledge items. Thus, the internal consistency and reliability were checked using SPSS version 23 software (Cronbach’s alpha (α) =0.79). Similarly, adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures internal consistency and reliability was checked (Cronbach’s alpha (α) =0.72).

Bivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the association of each independent variable with the outcome variable by using binary logistic regression. The goodness of fit was tested by Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic and Omnibus tests. The direction and strength of statistical association were measured by odds ratio with 95% CI. Adjusted odds ratio along with 95% CI is estimated to identify predictors of willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination by using multivariate analysis in the binary logistic regression model. In this study P-value <0.05 was considered to declare a result as a statistically significant association.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from Wolkite University, the college of medicine, and health science ethical review committee. Next, Official letter was submitted to Gurage Zone health office. And then, from health office cooperation letter was written to selected hospitals. Informed, voluntary, and written consent was obtained from each study subject prior to data collection process preceded. Study participants who were not willing to participate in the study have the right to refuse, withdraw their part in the study.

Result

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

A total of 630 lactating mothers were involved in this study, which made a response rate of 99.4%. The mean age of study participants was 25±0.42 years. The majority 95% of study participants were married and 79.8% of mothers were Gurage ethnicity. About 55% of study participants were orthodox religion followers. Regarding the educational status, 52.7% were completed primary education. More than half, 57% of study participants resided in a rural area (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants in Southern Ethiopia, 2021 (n=630)

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | <25 | 291 | 46.2 |

| ≥25 | 339 | 53.8 | |

| Marital status | Married | 600 | 95.2 |

| Single | 12 | 1.9 | |

| Widowed/divorced | 18 | 2.9 | |

| Ethnicity | Gurage | 503 | 79.8 |

| Amhara | 82 | 13.1 | |

| Oromo | 45 | 7.1 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 348 | 55.2 |

| Muslim | 145 | 23.1 | |

| Protestant | 62 | 9.8 | |

| Catholic | 75 | 11.9 | |

| Maternal educational status | No formal education | 53 | 8.4 |

| Primary education | 332 | 52.7 | |

| Secondary and above | 245 | 38.9 | |

| Maternal occupation | House wife | 357 | 56.7 |

| Merchant | 129 | 20.5 | |

| NGO employee | 12 | 1.9 | |

| Government employee | 132 | 21.0 | |

| Residence | Rural | 270 | 43.0 |

| Urban | 360 | 57.0 |

Obstetric Health Care Service Utilization

Out of the total respondents, 68% and 64% were multigravida and multiparous respectively. Regarding antenatal care follow-up, 82.7% of mothers had antenatal care visits. Of these, 39% of mothers had ≥4 times ANC visit. Concerning medical illness, 5.7% of mothers had document previous history of medical illness. Regarding infant sex and age, 63% and 79.7% were male and below 6 months respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetric Characteristics of Study Participants in Southern Ethiopia, 2021 (n=630)

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gravidity | Primigravida | 202 | 32.0 |

| Multigravida | 428 | 68.0 | |

| Parity | Primiparous | 226 | 36.0 |

| Multiparous | 404 | 64.0 | |

| History of ANC visit | Yes | 521 | 82.7 |

| No | 109 | 17.3 | |

| If yes how many times | 1 | 42 | 8.1 |

| 2 | 62 | 11.9 | |

| 3 | 214 | 41.1 | |

| ≥4 | 203 | 39.0 | |

| Mothers medical illness | Yes | 36 | 5.7 |

| No | 594 | 94.3 | |

| Types of medical illness | Hypertension | 12 | 33.3 |

| Diabetes | 10 | 27.8 | |

| Kidney problems | 14 | 38.9 | |

| Place of birth | Home | 31 | 4.9 |

| Health institution | 599 | 95.1 | |

| Infant sex | Male | 232 | 36.8 |

| Female | 398 | 63.2 | |

| Children age | <6 month | 502 | 79.7 |

| ≥6 month | 128 | 20.3 | |

| Immunization counselling | Yes | 450 | 71.4 |

| No | 180 | 28.6 |

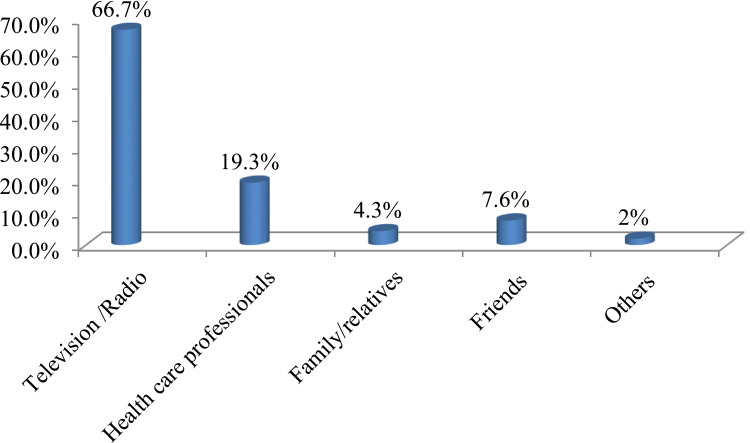

Maternal Source of Information About COVID-19 Vaccine

Out of 420 lactating mothers who had heard about the COVID-19 vaccine, nearly two-third, 66.7% of study participants heard from the mass media (television/radio) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Maternal source of information about COVID-19 vaccine among study participants in Southern Ethiopia, 2021 (n=630).

Knowledge About COVID-19 Among Study Participants

Among 630 study participants, 66.7% of respondents recognize the availability of the COVID-19 vaccine, 51.9% know the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine to control the pandemic. Overall, 51.9% (95% CI; 47.6–57%), of study participants had good knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine.

Adherence to COVID-19 Mitigation Measures

Out of 630 study participants, 64.8% utilized face masks, 81.9% covered the mouth during coughing, and 83.2% practiced regular hand washing. Overall, 63.2% (95% CI; 56.7–69.8%) of study participants had good adherence towards COVID-19 mitigation measures.

Attitude Towards COVID-19 Vaccination

Out of 630 study participants, 42.1% (95% CI; 39.2–45.8%) of study participants have a favourable attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination.

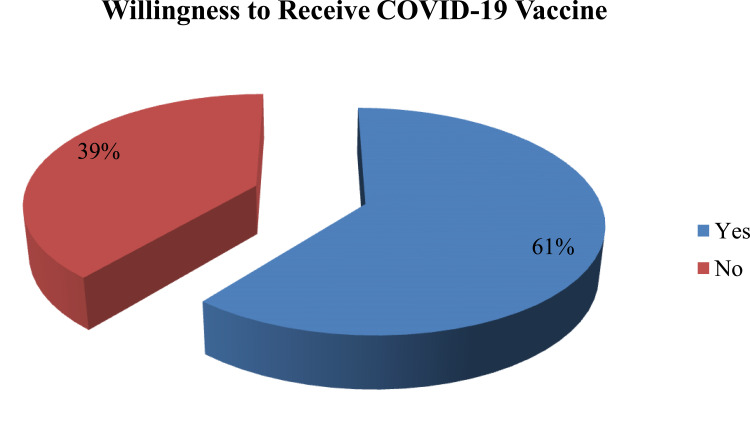

Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine

The finding of this study showed that 61% (95% CI; 56.9–65.1%) of lactating mothers had willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination if it is available (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination among study participants in Southern Ethiopia, 2021 (n=630).

Factors Associated with Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccination

Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were carried out to identify factors associated with willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination if it is available. All variables with a p-value of less than 0.25 were included in the multivariable regression model.

The result of bivariate logistic regression analysis showed that urban residence, maternal medical illness, having secondary and above educational status, giving birth at health institution, immunization counseling, good knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine, and good adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures were factors associated with willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination.

In multivariable logistic regression, all significant variables in binary logistic regression were adjusted. The result showed that mothers resided in the urban area, secondary and above educational status, immunization counseling, good knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine, and good adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures were factors associated with willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bivariate and Multivariable Analyses to Identify Factors Associated with Lactating Mothers Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccination in Southern Ethiopia, 2021 (630)

| Variables | Categories | Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccination | COR(95% CI) | AOR(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (246) | Yes (384) | ||||

| Maternal age | <25 | 122(42%) | 169(58%) | 1 | 1 |

| ≥25 | 124(36.6%) | 215(63.4%) | 1.25(0.33–1.92) | 0.48(0.29–1.58) | |

| Residence | Rural | 84(31%) | 186(69%) | 1 | 1 |

| Urban | 162(45%) | 198(55%) | 1.81(1.12–2.81)* | 2.51(1.62–3.91)* | |

| Maternal medical illness | Yes | 11(30.6%) | 25(69.4%) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 235(39.6%) | 359(60.4%) | 1.49(1.33–2.64)* | 1.28(0.93–1.84) | |

| Maternal educational status | No formal education | 21(39.6%) | 32(60.4%) | 1 | 1 |

| Primary | 103(31%) | 229(69%) | 0.69(0.56–1.96) | 0.91(0.86–2.31) | |

| Secondary and above | 122(49.8%) | 123(50.2%) | 1.51(1.38–2.01)* | 2.83(1.51–4.21)* | |

| Place of birth | Home | 11(35.5%) | 20(64.5%) | 1 | 1 |

| Health institution | 235(39.2%) | 364(60.8%) | 1.17(1.01–2.99)* | 0.81(0.79–1.52) | |

| Immunization counselling | Yes | 148(33%) | 302(67%) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 98(54.4%) | 82(45.6%) | 2.44(1.47–4.22)* | 3.44(1.95–5.91)** | |

| Knowledge | Poor knowledge | 108(35.6%) | 195(64.4%) | 1 | 1 |

| Good knowledge | 138(42.2%) | 189(57.8%) | 1.32(1.04–1.94)* | 2.62(1.84–3.47)* | |

| Attitude | Unfavourable attitude | 118(32.3%) | 247(67.7%) | 1 | 1 |

| Favourable attitude | 128(48.3%) | 137(51.7%) | 1.96(0.89–2.31) | 1.82(0.71–3.64) | |

| Adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures | Poor adherence | 67(29%) | 165(71%) | 1 | 1 |

| Good adherence | 179(45%) | 219(55%) | 2.0(1.62–4.81)* | 3.2(1.91–5.63)* | |

Notes: 1=reference, *p=<0.05, **P=0.001.

Abbreviations: AOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; COR, Crude Odds Ratio.

Discussion

The present study showed that 51.9% of study participants demonstrated good knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine. The finding was comparable with a study conducted in Bangladesh 57%.27 However, it was lower than a study conducted among the young Lebanese population 67.1%.32 The possible discrepancy might be due to differences in study population and study period. The level of adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures was found to be 63.2% which was higher than a study conducted in Dirashe district 12.3%33 and Gondar 51%34 among the general population. The possible cause of the discrepancy might be due to the study area and study period difference. For instance, the present study was conducted in a health institution that makes lactating mothers should adhere to some of the COVID-19 mitigation measures such as wearing face masks, maintaining physical distancing, and practice hand washing. In this study, about 57.5% of study participants had unfavourable attitude towards the COVID-19 vaccination. The finding was much lower than a study conducted in India (83.6%).35 The possible explanation might be India was one of the countries that were severely affected by the pandemic following the USA, Brazil, and Mexico.36 Thus, individuals might have a positive attitude towards vaccination to escalate the transmission of COVID-19 and to eliminate COVID-19 related morbidity and mortality.

The prevalence of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination in this study was (61%) which was lower than a study conducted in Somali (76.8%) and China (>90%) of the general population.22,29 The possible justification might be due to the difference in the study population and study design. For example, the study population in Somali was almost 80% of study participants were from the university. However, the finding was higher than studies conducted in Kuwait 53.1% and Jordan 37.4% among the general public.37,38 The possible explanation for the discrepancy might be due to frequent health care facility visiting; for instance, in our study, lactating mothers have visited a health facility for their child vaccination, which might increase their awareness regarding the COVID-19 vaccine.

The odds of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine among lactating mothers who resided in urban areas were 2.5 times higher than lactating mother’s resided in rural areas. The finding was in line with a study conducted in India.35 The possible explanation might be those lactating mothers who had resided in urban areas have better access to quality health care services. The odds of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination among lactating mothers who had secondary and above educational status were 2.8 times higher than their counterparts. The finding was consistent with a study conducted in Uganda.39 This could be explained that having higher educational status makes them have better awareness regarding the benefits of vaccination. The odds of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination among lactating mothers who had received immunization counselling during EPI visits were 3 times higher than their counterparts. The possible justification might be due to health care workers counselling mothers about the benefits of vaccination.

Mothers who had good knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine were 2.6 times higher than those who had poor knowledge. The result was in line with studies conducted in Vietnam and Addis Ababa.40,41 The possible justification might be those mothers who had good knowledge regarding the COVID-19 vaccine have better information on the merits of vaccination. Similarly, the odds of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination among lactating mothers who had good adherence towards COVID-19 mitigation measures were 3 times higher than those mothers who had poor adherence. The finding was consistent with a study conducted in Somalia.29

Strength and Limitation of the Study

The strength of this study is identifying the determinant factors of willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine that can provide good information for policymakers and different stakeholders. However, it was not void of limitations, since the study was conducted in health institutions; study participants must adhere to COVID-19 mitigation measures that might inflate the finding particularly, the level of adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures.

Conclusion

Mothers who were resided in urban areas, having secondary and above education status, counselling during EPI visits, good knowledge about the vaccine, and good adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures were determinant factors of lactating mothers’ willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccination. Therefore, health professionals should counsel about the merits of COVID-19 vaccination and enhance their awareness about vaccine is recommended.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for Wolkite University, data collectors, study participants, and each individual who were supporting to accomplish this research project.

Funding Statement

All cost was covered by researcher.

Abbreviations

ACIP, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice; ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; ABM, Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine; COVID-19, coronaviruses disease 2019; EPI, Expanded Program of Immunization; FDA, Food and Drugs Administration; CDC, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; SMFM, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; SAGE, Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

Author Contributions

The author made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Song F, Shi N, Shan F, et al. Emerging 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-NCoV) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295(1):210–217. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march–2020. Accessed August 14, 2021.

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed May 29, 2021.

- 4.World Health Organization. Ethiopia - WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/et. Accessed September 24, 2021.

- 5.Gray KJ, Bordt EA, Atyeo C, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine response in pregnant and lactating women: a cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(3):303.e1–303.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zambrano LD, Ellington S, Strid P, et al. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status — United States, January 22–October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(44):1641–1647. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.More than 2.01 billion shots given: Covid-19 tracker. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/covid-vaccine-tracker-global-distribution/. Accessed June 4, 2021.

- 9.Society for maternal-fetal medicine (SMFM) statement: SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in pregnancy. Available from: https://s3.amazonaws.com/cdn.smfm.org/media/2591/SMFM_Vaccine_Statement_12-1-20_(final).pdf. Accessed June 1, 2021.

- 10.ABM. Academy of breastfeeding medicine statement; considerations for COVID-19 vaccination in lactation. Available from: https://www.bfmed.org/abm-statement-considerations-for-covid-19-vaccination-in-lactation. Accessed October 7, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.ACIP. Advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) vaccine recommendations and guidelines. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/index.html. Accessed May 2, 2021.

- 12.ACOG. Vaccinating pregnant and lactating patients against COVID-19. Available from: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/12/vaccinating-pregnant-and-lactating-patients-against-covid–19. Accessed June 3, 2021.

- 13.Middleton EL. Fact sheet for healthcare providers administering vaccine (vaccination providers) emergency use authorization (eua) of the pfizer-biontech covid-19 vaccine to prevent coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19). 2019;2019:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Background Document on the Janssen Ad26.COV2.S (COVID-19) Vaccine. World Health Organization. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Background Document on the mRNA-1273 Vaccine. Vol. 2. World Health Organization. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Background document on the mRNA vaccine BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) against COVID-19. WHO. 2021;2(January):1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. COVID-19 vaccine explainer COVID-19 vaccine ChAdOx1-S [recombinant], developed by Oxford University and AstraZeneca. 2021;1222:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray KJ, Bordt EA, Atyeo C, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine response in pregnant and lactating women: a Cohort Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perl SH, Uzan-Yulzari A, Klainer H, et al. SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies in breast milk after COVID-19 vaccination of breastfeeding women. JAMA. 2021;325(19):2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertrand K, Honerkamp-Smith G, Chambers C. Maternal and child outcomes reported by breastfeeding women following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. medRxiv. 2021;1:2021.04.21.21255841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacDonald NE, Eskola J, Liang X, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sallam M. Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9(2):1–15. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Razai MS, Chaudhry UAR, Doerholt K, Bauld L, Majeed A. Covid-19 vaccination hesitancy. BMJ. 2021;373:n1138. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cerda AA, García LY. Hesitation and refusal factors in individuals’ decision-making processes regarding a coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination. Front Public Health. 2021;9(April). doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.626852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CSA. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mose A, Yeshaneh A. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and its associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic in southwest Ethiopia: Institutional-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:2385–2395. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S314346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saiful Islam M, Siddique AB, Akter R, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions towards COVID-19 vaccinations: a cross-sectional community survey in Bangladesh. medRxiv. 2021:2021.02.16.21251802. doi: 10.1101/2021.02.16.21251802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tao L, Wang R, Han N, et al. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women in China: a Multi-Center Cross-Sectional Study based on health belief model. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1892432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed MAM, Colebunders R, Gele AA, et al. Covid-19 vaccine acceptability and adherence to preventive measures in Somalia: results of an online survey. Vaccines. 2021;9(6):1–11. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasemy ZA, Bahbah WA, Zewain SK, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward COVID-19 among Egyptians. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020;10(4):378–385. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.200909.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elhadi M, Alsoufi A, Alhadi A, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and acceptance of healthcare workers and the public regarding the COVID-19 vaccine: a Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–21. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10987-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakr S, Ghaddar A, Sheet I, Eid AH, Hamam B. Knowledge, attitude and practices related to COVID-19 among young Lebanese population. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10575-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bante A, Mersha A, Tesfaye A, et al. Adherence with COVID-19 preventive measures and associated factors among residents of Dirashe district, southern Ethiopia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:237–249. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S293647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azene ZN, Merid MW, Muluneh AG, et al. Adherence towards COVID-19 mitigation measures and its associated factors among Gondar City residents: a Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study in Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15(12 December):1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumari A, Ranjan P, Chopra S, et al. Knowledge, barriers and facilitators regarding COVID-19 vaccine and vaccination programme among the general population: a cross-sectional survey from one thousand two hundred and forty-nine participants. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2021;15(3):987–992. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.COVID: Brazil has more than 4000 deaths in 24 hours for first time. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world–latin–america–56657818. Accessed October 7, 2021.

- 37.Alqudeimat Y, Alenezi D, AlHajri B, et al. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and its related determinants among the general adult population in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(3):262–271. doi: 10.1159/000514636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Elimat T, AbuAlSamen MM, Almomani BA, Al-Sawalha NA, Alali FQ. Acceptance and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines: a cross-sectional study from Jordan. PLoS One. 2021;16(4 April):1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Echoru I, Ajambo PD, Keirania E, Bukenya EEM. Sociodemographic factors associated with acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine and clinical trials in Uganda: a Cross-Sectional Study in western Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoque AM, Alam AM, Hoque M, Hoque ME, Van HG. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 of pregnant women at a primary health care facility in South Africa. Eur J Med Health Sci. 2021;3(1):50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dereje N, Tesfaye A, Tamene B, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a Mixed-Methods Study. medRxiv. 2021:2021.02.25.21252443. Availble from: https://medrxiv.org/cgi/content/short/2021.02.25.21252443. Accessed October 7, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]