Abstract

Background:

Aorta and carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) is a measure of subclinical atherosclerosis and useful to assess cardiometabolic risk in the young. The in utero milieu may involve cardiometabolic programing and the development of cardiometabolic risk factors in children. Maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, and micronutrient deficiencies during pregnancy influence the development of the cardiovascular system through a process of DNA methylation.

Aim:

To explore an association between maternal smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy and intima media thickness in 5-year-old children for a low-income setting.

Methods:

Data were collected from 500 mother–child pairs at antenatal clinic visit, at birth, and at age 5 years. Anthropometric measurements were collected at birth and again at age 5 years. As well as clinical and ultrasound measurements at age 5 years. Clinical measurements, at age 5 years, included blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, and heart rate. Ultrasound measurements of the aorta and carotid arteries IMT were performed at age 5 years. Main outcome of interest was effect of dual teratogen exposure on the ultrasound measures IMT as indication of cardiometabolic risk.

Results:

cIMT was significantly higher in children exposed to both alcohol and nicotine during pregnancy compared to those not exposed (p = .008). In separate linear models, dual in utero exposure (beta = 0.12; p = .01) and male sex (beta = 0.14; p = .01) were associated with higher right cIMT values (F(6,445) = 5.20; R2 = 0.07, p < .01); male sex (beta = 0.13; p = .01) and low birth weight (beta = 0.07; p = .01) with higher left cIMT value (F(4,491) = 4.49; R2 = 0.04; p = .01); and males sex (beta = 0.11; p = .02) with higher aorta IMT (F(6,459) = 5.63; R2 = 0.07; p< .01). Significant positive correlations between maternal measures of adiposity, maternal MUAC (r = 0.10; p = .03), and maternal BMI (r = 0.12; p< .01) and right cIMT measurements adjusted for the BMI of the child at age 5 years as covariate. Blood pressure measurements at age 5 years were not significantly associated with IMT but, instead, correlated significantly and positively with the BMI of the child at age 5 years (p< .01).

Conclusion:

Children exposed to both maternal smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy presented with cardiometabolic risk factors 5 years after birth. In addition, maternal adiposity, male sex, and low birth weight were associated with higher IMT at age 5 years.

Keywords: Anthropometry, cardiometabolic risk factors, intima media thickness, intrauterine teratogen exposure, pediatrics

Introduction

Cardiometabolic diseases are associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and decreased quality of life. The management of these diseases and the associated complications place considerable financial strain on health systems, necessitating early intervention to mitigate the burden and decrease healthcare costs [1,2]. In many cases, end organ vascular complications including myocardial infarction and stroke occur years or even decades following the establishment of a formal diagnosis or clinical recognition of the associated risk factors [3–5]. In addition, there is growing recognition of cardiometabolic risk as an important clinical issue in the pediatric population [6]. In this context, longitudinal studies support an association between cardiometabolic risk factors present during childhood and the development of vascular insults or complications during adulthood [7].

The developing world is facing a dual pandemic of obesity and malnutrition [8]. On the one hand, poverty and food insecurity are associated with underweight status and nutritional deficiencies in adults and children [9]. On the other, low levels of education and unemployment are associated with consumption of cheaper, less nutrient-dense foods, which in turn increase risk for development of obesity and obesity related illnesses such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and CVD [10–13]. In addition, maternal obesity and excessive weight gain during pregnancy have been associated with higher birth weights and adiposity in female offspring [14] and predisposition of insulin resistance during childhood [15].

Moreover, developing countries struggle with high rates of in utero alcohol and nicotine exposure which are associated with micronutrient deficiencies and mechanisms such as endothelial dysfunction [16,17] and abnormal fetal angiogenesis implicated in the development of cardiometabolic diseases later in life [13,18]. The combined deleterious effects of in utero exposure to both alcohol and nicotine awn fetal growth are more severe than the effects of either smoking or drinking alone [19,20]. In utero teratogen exposure may be further compounded by poor maternal nutrition during pregnancy [8,20]. In this context, maternal antenatal health may predispose the child to development of cardiometabolic diseases later in life [16] particularly if compounded by poor childhood diet and sedentary lifestyle [6]. These findings support the importance of both maternal health and early life insults as determinants of cardiometabolic risk in the pediatric population.

In South Africa, there is paucity of prospective studies investigating the effects of in utero teratogen exposure on the longitudinal development and progression of cardiometabolic risk factors during early childhood. In addition, studies to date have been limited to adult studies as well as underrepresentation of diverse ethnic groups, which warrants investigation given the proposed genetic underpinnings of cardiometabolic risk. In a previous study (unpublished data), we demonstrated increase adiposity values and cardio-metabolic risk factors in a cohort of 500 children from a low-income South African community. In the present study, we sought to build on these existing findings by exploring the effects of in utero alcohol and nicotine exposure on aorta and carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) over the first 5 years of life in the same cohort of 500 children. In addition, we aimed to investigate to what extent maternal adiposity contributed to the development of these risk factors in children during early life. In particular, we focused on ultra-sonographic aorta and carotid IMT measurements associated with adiposity indices.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

Ethics approval for the present study was obtained from the Health and Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of Stellenbosch University (SU) and Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BMREC) of the University of the Western Cape (UWC). Voluntary written informed consent was obtained from the mother or caregiver of the child. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (Declaration of Helsinki. Bull World Health Organ, 2001).

Study design

The present substudy drew on longitudinal data collected as part of the larger descriptive Safe Passage Study (SPS), designed to obtain more information on the role of antenatal exposure to alcohol in stillbirths and sudden unexplained infant deaths [21]. In the present analysis, we used maternal information obtained prospectively for the SPS during antenatal clinic visits, as well as prospective data on pediatric health obtained from assessment of the child at birth and again at 5 years of age.

Selection of study participants

The present study was conducted at Stellenbosch University Obstetric and Gynaecology SPS Unit at Tygerberg Hospital, Cape Town over an 18-month period (June 2016 to December 2017). Pregnant women were recruited from the Belhar antenatal clinic or Bishop Lavis Midwife Obstetric Unit (MOU) and had prenatal research follow-up at Tygerberg Hospital. Data from antenatal visits were obtained from pregnant women who attended Bishop Lavis antenatal clinic enrolled for the SPS. All pregnant women booking for antenatal care were invited to be part of the study. For infant follow up, we excluded twins and children with congenital abnormalities at birth. Children age 5 years with severe features of fetal alcohol syndrome as well as other forms of severe metal restriction were excluded from the study.

Participant assessments

Maternal assessments

A study questionnaire was used to document sociodemographic information during antenatal visits, as well as data on nutrition, pregnancy history, and use of alcohol as well as nicotine [21]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from measurements collected at the first antenatal visit and calculated as the body weight in kilograms divided by the height in meters squared. Midupper arm circumference (MUAC) was also measured as the circumference of the right upper arm measured at the midpoint between the tip of the shoulder and the tip of the elbow (olecranon process and the acromium) using a tape measure.

Pediatric assessments

BMI was measured at birth and age five. Weight was measured using an electronic Mellerware, Munich scale to the nearest 0.01 kg. Height was measured without shoes using a mechanical Panamedic stadiometer fixed to a wall. MUAC was measured from children at birth, 1 month, and at 1 year of age. Triceps (tSFT) and subscapular skin fold thickness (sSFT) were measured in millimeters using a Holtain caliper. Subscapular SFT was measured from the left side of the body to the nearest 0.1 mm while the fingers continued to hold the skinfold. The actual measurement was read from the caliper about 3 s after the caliper tension was released. Measurements were taken at the following sites: (a) triceps, halfway between the acromion process and the olecranon process and (b) subscapular, approximately 20 mm below the tip of the scapula, at an angle of 45° to the lateral side of the body. Waist circumference was calculated at year five as measured around the waist at the midpoint between the last rib and the iliac crest using a tape measure. Each child was measured three times and mean values were obtained from the three measurements. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and heart rate (HR) were measured at 5 years of age. Blood pressure was measured in the right upper arm in a sitting position using a validated CAS Medical Systems, Inc. (Branford, CT), 740 MAXNIBP automated digital sphygmomanometer. A size-appropriate blood pressure cuff was used and all measurements were repeated three times.

Ultrasonography was performed on children at 5 years of age using a Voluson E8 ultrasound system (GE Healthcare, Kretz ultrasound, Zipf, Austria) equipped with a RAB4-8D (3.1–8 MHz) convex 3D/4D transabdominal transducer and a 9L-D (3.1–10 MHz) linear array transducer specific for vascular and pediatric application. Left and right carotid (cIMT) as well as aorta intimal-medial thickness were measured at age five using existing recommended international protocols such as the Mannheim Consensus [22]. The decision to measure cIMT was motivated by superficial location of the carotid in the neck and easily visualized by noninvasive quality of ultrasound [23].

Statistical analysis

SPSS® software (version 21.0 for Windows; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses. Quantitative data were described as the means along with SD for normally distributed data and medians with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for skewed data. Categorical variables were presented as percentages. Independent samples t-tests and analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used for comparisons between groups. To explore the effects of alcohol and nicotine exposure on outcome variables, comparisons were performed between four groups, i.e. (1) mothers who did not use alcohol or nicotine during pregnancy (33%), (2) mothers who used both alcohol and nicotine during pregnancy (28%), mothers who used alcohol but not nicotine during pregnancy (9%), and (3) mothers who used nicotine but not alcohol during pregnancy (29%). Post hoc LSD, Tukey, or Bonferroni tests were used to indicate differences between exposure groups. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to describe linear relationships between continuous variables. Separate linear regression models were constructed to illustrate the independent association between in utero exposure to alcohol and nicotine and cIMT measurements with adjustment for BMI, sex of the child, and aIMT; these outcome variables were entered: modeling for alcohol and nicotine exposure, adjusting for exposure, sex, maternal MUAC, BW as well as weight at 5 years as covariates. Statistical significance was set at p< .05.

Results

The characteristics of the study group are described in Tables 1 and 2. Baseline maternal and neonatal characteristics are presented according to the alcohol consuming and smoking status of the mother (Table 1) and pediatric characteristics at end-point, age 5 years, are described separately (Table 2) and compared between the four exposure groups, controls (n = 146), dual exposed to alcohol and nicotine (n = 154), alcohol only exposed (n = 33), and nicotine only exposed (n = 167).

Table 1.

Maternal and neonatal baseline characteristics according to maternal smoking and alcohol consumption.

| Age (years) | MUAC (cm) | BMI (kg/m2) | GA at enrollment (days) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics at enrollment | ||||

| Control group |

N = 147 25.6 (6.1) |

N = 143 27.3 (7.1) |

N = 145 29.2 (5.4) |

N = 147 126.2 (44.7) |

| Smoking and alcohol group |

N = 354 24.7 (5.9) |

N = 346 25.3 (5.7) |

N = 348 27.4 (4.5) |

N = 354 139.9 (48.1) |

| p Value | .16 | <.01 | <.01 | <.01 |

| Weight (kg) | Length (cm) | MUAC (cm) | GA at delivery (days) | |

| Pediatric neonatal characteristics at birth | ||||

| Control Group |

N = 147 3.1 (0.5) |

N = 126 49.1 (2.1) |

N = 124 10.5 (0.9) |

N = 147 274.1 (13.8) |

| Smoking and alcohol group |

N = 353 3.0 (0.6) |

N = 289 48.5 (2.3) |

N = 288 10.5 (1.0) |

N = 354 271.2 (14.8) |

| p Value | .18 | .01 | .14 | .04 |

MUAC: midupper-arm circumference; BMI: body mass index; GA: gestational age.

Data are expressed as mean (SD) and comparison between smoking and alcohol consuming mothers and controls.

Bold values represents as significance level p < than .01

Table 2.

Pediatric end point characteristics at age 5 years according to the four exposure groups.

| Controls N = 146 |

Dual exposed N = 154 |

Alcohol exposed N = 33 |

Smoking exposed N = 167 |

p Value | F | df | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric measurements | |||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 15.4 ± 2.1 | 15.2 ± 1.5 | 15.1 ± 1.7 | 15.1 ± 1.4 | .48 | 0.82 | 3, 497 |

| tSFT (cm) | 10.1 ± 3.8 | 9.4 ± 2.7 | 9.6 ± 4.4 | 9.3 ± 2.7 | .11 | 2.03 | 3, 497 |

| sSFT (cm) | 7.7 ± 4.2 | 7.0 ± 1.9 | 7.6 ± 3.9 | 6.9 ± 2.3 | .12 | 1.97 | 3, 496 |

| WC (cm) | 51.9 ± 5.2 | 51.4 ± 3.9 | 51.2 ± 3.7 | 50.7 ± 3.5 | .08 | 2.27 | 3, 466 |

| Clinical measurements | |||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 106.5 ± 10.7 | 107.1 ± 10.0 | 105.8 ± 11.7 | 104.3 ± 9.3 | .07 | 2.41 | 3, 496 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 65.3 ± 9.1 | 65.7 ± 9.1 | 65.6 ± 11.4 | 63.9 ± 9.0 | .29 | 1.24 | 3, 496 |

| MAP | 78.8 ± 9.5 | 79.4 ± 9.3 | 79.3 ± 11.3 | 77.3 ± 9.3 | .20 | 1.55 | 3, 496 |

| HR (b/min) | 91.7 ± 12.4 | 92.5 ± 14.4 | 91.8 ± 8.7 | 91.4 ± 13.3 | .90 | 0.20 | 3, 496 |

| Ultrasound measurements | |||||||

| Left cIMT (mm) | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | .52 | 0.76 | 3, 493 |

| Right cIMT (mm) | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 0.33 ± 0.04 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | <.01 | 5.92 | 3, 494 |

BMI: body mass index; tSFT: triceps skin fold thickness; sSFT: subscapular skin fold thickness; WC: waist circumference; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; MAP: mean arterial pressure; HR: heart rate; RT cIMT: right carotid intima-media thickness; LT cIMT: left carotid intima-media thickness.

Data are expressed as mean (SD) and comparisons between smoking and alcohol consuming mothers, alcohol only, nicotine only and controls.

Bold values represents as significance level p < than .01

Maternal age did not differ significantly between the controls and the smoking and alcohol consuming mothers. However, MUAC, BMI, and GA at enrollment were significantly lower and later for the smoking, alcohol consuming group (MUAC: 25.3 ± 5.7 cm, p < .01; BMI: 27.4 ± 4.5 kg/m2, p < .01 and GA at enrollment: 139.9 ± 48.1 days) compared to the control group (MUAC: 27.3 ± 7.1 cm, p < .01; BMI: 29.2 ± 5.4 kg/m2, p < .01 and GA at enrollment: 126.2 ± 44.7 days) (Table 1). At birth, infants born to smoking and alcohol consuming mothers had significantly lower body length (48.5 ± 2.3 cm, p = .01) compared to controls (49.1 ± 2.1 cm, p = .01). The infants from smoking, alcohol consuming mothers were also delivered at a significantly earlier GA (271.2 ± 14.8 days, p = .04) compared to controls (274.1 ± 13.8 days, p = .04). Body weight and MUAC at birth did not differ significantly between infants born to smoking, alcohol consuming mothers and controls (Table 1). In addition, the mothers of LBW infants had significantly lower maternal MUAC (26.5 ± 4.2 cm; p < .01) and BMI (24.2 ± 5.3 kg/m2; p < .01) at enrollment when compared to the mothers of NBW infants (MUAC: 28.2 ± 4.9 cm and BMI: 26.3 ± 6.3 kg/m2). Furthermore, BW also differed significantly between the four maternal exposure groups, with lowest BW noted for the nicotine and dual exposure groups (2.98 ± 0.59 kg and 2.98 ± 0.57 kg; p = .04) compared to controls (3.06 ± 0.52 kg).

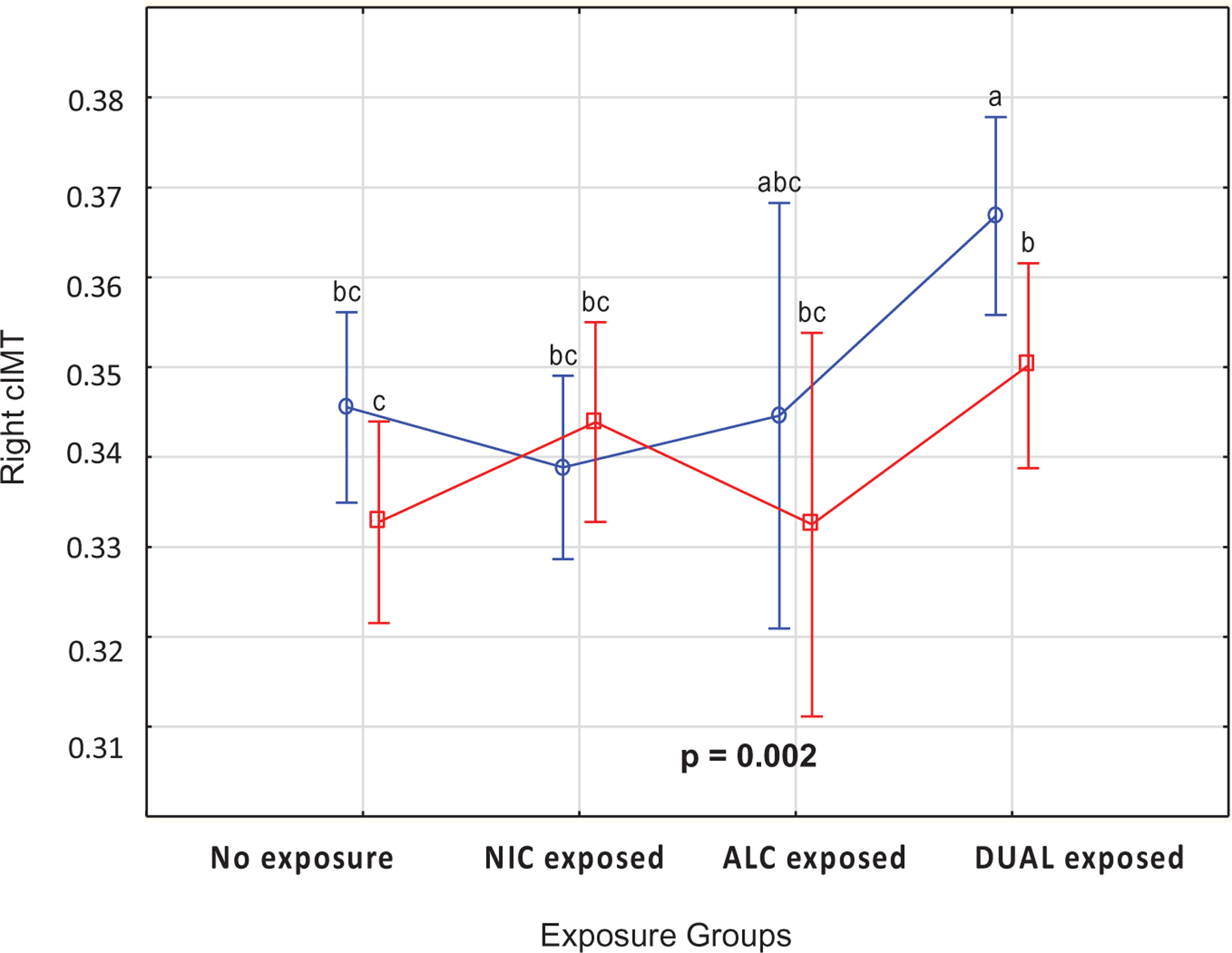

Anthropometric, clinical, and ultrasound measurement at age 5 years did not differ significantly between the four exposure groups except for the ultrasound measurement of the right cIMT. The right cIMT measurements for the dual exposed groups were significantly higher (0.36 ± 0.05 mm) compared to controls (0.34 ± 0.04 mm) F(3,494) = 5.92; p < .01 (Table 2 and Figure 1). The left cIMT and aorta IMT measurements did not differ significantly between the four exposure groups F(3493) = 0.76; p = .52 and F(3, 493) = 0.08; p = .97. However, at age 5 years, the left cIMT measurements were significantly lower for the females (0.35 ± 0.05 mm) compared to males (0.36 ± 0.05 mm) and t(495) = 3.07; p < .01 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Mean values for right carotid intima-media thickness (mm) according to the four exposure groups (p < .01) and compared between males and females at age 5 years as measured by ultrasound.

Figure 2.

Mean values for left carotid intima-media thickness (mm) compared between males and females (p< .01) at age 5 years as measured by ultrasound.

In addition, blood pressure, MAP and HR did not differ significantly between the four exposure groups. For SBP, (F(3,496) = 2.41 at p = .07), DBP (F(3,496) = 1.24 at p = .29), MAP (F(3, 496) = 1.55 at p = .20), and HR (F(3,496) = 0.20 at p = .90).

Furthermore, right cIMT correlated significantly and positively with maternal MUAC (r = 0.11; p = .02), maternal BMI (r = 0.11; p = .02), body weight of the child at 5 years (r = 0.12; p = .01), BMI of the child at 5 years (r = 0.10; p = .04), and WC (0.12; p = .01) at age 5 years. After controlling for the BMI of the child at 5 years, maternal MUAC (r = 0.10; p = .03) and maternal BMI (r = 0.12; p < .01) correlated significantly and positively with right cIMT. However, after controlling for the BMI of the child at age 5 years, the relationship between right cIMT and body weight and WC of the child was no longer significant. Left cIMT correlated significantly and positively with birth weight (r = 0.10; p = .02) and weight of the child at age 5 years (r = 0.09; p = .05). Aorta IMT correlated significantly and positively with body weight (r = 0.21; p < .01), BMI (r = 0.21; p < .01), subscapular SFT (r = 0.10; p = .03), and WC (r = 0.13; p = .01) of the child at age 5 years (Table 3). After controlling for the BMI of the child, the relationship between body weight of the child (r = 0.10; p = .03) and aIMT at age five was still significant but not with subscapular SFT (r = 0.01; p = .87) or WC (r = 0.08; p = .08).

Table 3.

Associations between maternal and child adiposity indices and left and right cIMT expressed as Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r).

| Left cIMT |

Right cIMT |

Aorta IMT |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | n | r | p | n | r | p | n | |

| Maternal MUAC | 0.05 | .27 | 489 | 0.11 | .02 | 490 | 0.07 | .10 | 489 |

| Maternal BMI | 0.06 | .18 | 485 | 0.11 | .02 | 486 | 0.07 | .14 | 485 |

| BW | 0.10 | .02 | 496 | 0.04 | .37 | 497 | 0.05 | .28 | 495 |

| Weight at 5 years | 0.09 | .05 | 497 | 0.12 | .01 | 497 | 0.21 | <.01 | 496 |

| BMI at 5 years | 0.07 | .12 | 497 | 0.10 | .04 | 497 | 0.21 | <.01 | 496 |

| Triceps SFT | 0.01 | .85 | 498 | −0.05 | .31 | 499 | 0.06 | .19 | 498 |

| Subscapular SFT | −0.04 | .40 | 497 | −0.01 | .77 | 498 | 0.10 | .03 | 497 |

| WC | 0.07 | .12 | 466 | 0.12 | .01 | 467 | 0.13 | .01 | 466 |

MUAC: mid-upper-arm circumference; BMI: body mass index; BW: infant weight at birth; SFT: skin fold thickness; WC: waist circumference.

Bold values represents as significance level p < than .01

Left and right cIMT correlated significantly and negatively with HR (r = ‒0.09; p = .05 and r = ‒0.10; p = .03), but not with SBP, DBP or MAP. Aorta IMT did not correlate significantly with any of the BP measurements, nor with HR (r = 0.05; p = .31) (Table 4). BMI at age 5 years correlated significantly and positively with SBP (r = 0.16; p < .01), DBP (r = 0.18; p < .01), and MAP (r = 0.17; p < .01) but not with HR (r = 0.03; p = .48) (Table 5). Furthermore, after controlling for the BMI of the child, these negative relationships between left and right cIMT and HR were still significant (r = ‒0.10; p = .04 and r = ‒0.10; p = .02).

Table 4.

Associations between blood pressure measurements and left, right cIMT and aIMT at age 5 years expressed as Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r).

| Left cIMT |

Right cIMT |

Aorta IMT |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | n | r | p | n | r | p | n | |

| SBP | 0.02 | .61 | 496 | 0.04 | .37 | 497 | 0.04 | .35 | 495 |

| DBP | −0.02 | .73 | 496 | 0.01 | .78 | 497 | 0.04 | .33 | 495 |

| MAP | 0.03 | .45 | 496 | 0.05 | .31 | 497 | 0.03 | .51 | 495 |

| HR | −0.09 | .05 | 496 | −0.10 | .03 | 497 | 0.05 | .31 | 495 |

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; MAP: mean arterial pressure; HR: heart rate; cIMT: carotid intima media thickness; aIMT: aorta intima media thickness.

Bold values represents as significance level p < than .01

Table 5.

Associations between BMI at age 5 years and blood pressure measurements expressed as Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r).

| BMI (kg/m2) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | n | |

| SBP | 0.16 | <.01 | 496 |

| DBP | 0.18 | <.01 | 496 |

| MAP | 0.17 | <.01 | 496 |

| HR | 0.03 | .48 | 500 |

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; MAP: mean arterial pressure; HR: heart rate; BMI: body mass index.

Bold values represents as significance level p < than .01

In a separate linear models, adjusting for maternal MUAC, maternal BMI, current body weight and WC of the child at age 5 years, in utero exposure to alcohol and nicotine (0.12; p = .01), and sex of the child (0.14; p = .01) were significantly associated with right cIMT measurements (F(6,445) = 5.20, R2 = 0.07, p < .01). In a second linear model, adjusting for current body weight of the child at age 5 years and in utero exposure to alcohol and nicotine, birth weight (0.07, p = .01), and sex of the child (0.13, p = .01), were significantly associated with left cIMT measurements (F(4,491) = 4.49, R2 = 0.04, p = .01). In a third linear model (F(6,459) = 5.63, R2 = 0.07, p < .01), adjusting for current body weight, BMI, WC, and subscapular SFT of the child at age 5 years, sex of the child (0.11, p = .02) were significantly and independently associated with aorta IMT measurements (Table 6).

Table 6.

Linear Models for aorta, right, and left carotid intima media thickness incorporating in utero exposure, sex, maternal MUAC, maternal BMI, weight, WC, subscapular skin fold thickness, and BMI of the child at age 5 years.

| F | df | p Value | R 2 | Beta | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model: RT cIMT | 5.20 | 6, 445 | <.01 | 0.07 | ||

| IDV: exposure | 0.12 | .01 | ||||

| Sex | 0.14 | .01 | ||||

| MAT. MUAC | −0.10 | .44 | ||||

| MAT. BMI | 0.21 | .10 | ||||

| Weight at 5 years | 0.12 | .24 | ||||

| WC at 5 years | 0.02 | .81 | ||||

| Model: LT cIMT | 4.49 | 4, 491 | .01 | 0.09 | ||

| IDV: sex | −0.13 | <.01 | ||||

| BW | 0.07 | .01 | ||||

| Exposure | 0.06 | .19 | ||||

| Weight at 5 years | 0.07 | .13 | ||||

| Model: aorta IMT | 5.63 | 6, 459 | <.01 | 0.07 | ||

| IDV: SSC SFT at 5 years | 0.02 | .74 | ||||

| Sex | −0.11 | .02 | ||||

| Exposure | −0.03 | .59 | ||||

| BMI at 5 years | 0.02 | .86 | ||||

| Weight at 5 years | 0.13 | .21 | ||||

| WC at 5 years | 0.09 | .47 |

RT cIMT: right carotid intima-media thickness; LT cIMT: left carotid intima media thickness; BMI: body mass index of the child at age 5 years; WC: waist circumference; IMT: intima media thickness; SSC SFT: subscapular skin fold thickness.

Bold values represents as significance level p < than .01

In the present study, 352 children were exposed to maternal smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy and 146 were not exposed (controls). From the 124 children who had right cIMT measurements above 0.365 mm, 98 (79%) were exposed to smoking and alcohol during gestation. The odds of having a higher than 0.365 mm right cIMT was 1.78 times greater for an exposed child compared to controls with 95% CI: 1.1–2.9 and significant at p = .02.

Discussion

The main finding from this study was dual alcohol and nicotine exposure during pregnancy, as well as maternal MUAC and male sex were associated with significantly higher right cIMT values in children 5 years of age. In contrast, in utero alcohol and nicotine exposure was not significantly associated with either higher left cIMT or aorta IMT values in children aged five. However, male sex and low birth weight were significantly associated with higher left cIMT values in children aged 5 years. Male sex was significantly and independently associated with higher aorta IMT values at aged 5 years. Secondary findings included, maternal adiposity indicators, MUAC and BMI, as well as adiposity indicators of the child were related to higher cIMT values, irrespective of the in utero exposure to alcohol and nicotine. Our results are in agreement with previous studies which demonstrated a positive correlation between higher cIMT and LSE status. Liu et al. [13] were the first to demonstrate an association between children from LSE communities and higher cIMT values in midchildhood. In the present study, higher cIMT values were observed in a younger study population. Findings from the present study are in line with those of many other studies utilizing the measurement of IMT as an early marker of vascular changes due to the atherosclerosis process and fatty deposits [24–26]. Furthermore, our findings were in agreement with findings by Geerts et al. where higher cIMT measurements are associated with maternal smoking during pregnancy [27]. Our findings suggest, in addition to possible other pathogenic mechanisms, in utero exposure to both alcohol and nicotine might have a compounding effect on cIMT in contrast to nicotine alone. Moreover, animal as well as human studies describe enhanced vascular dysfunction caused by nutrient restriction, placental insufficiency as well as male sex as risk for cardiometabolic disease later in life [28,29]. Nutrient deficiencies during pregnancy, leading to endothelial dysfunction, might be the underpinning mechanism resulting in higher cIMT values in 5-year-old children from low-income settings. Our study population, being one from a low-income setting, experiences high rates of nutrient deficiencies [30]. In addition, maternal adiposity markers (MUAC and BMI) were not only related to child adiposity (BMI, WC, SFT) but also with higher right cIMT values in their 5-year-old offspring. These findings are consistent with those of a studies by Cornelius et al. [19] and Victora et al. who demonstrated the strong positive association between maternal BMI and child BMI as well as findings by Park et al. [31] who concluded strong associations between adiposity and cIMT measurements. Our findings are in agreement with several other studies; however, these studies were conducted mostly in Western Europe and the USA [31]. In these studies, primarily older age groups were utilized, illustrating the associations between adiposity and cIMT measurements as cardiometabolic risk in adolescents’ subjects. Unlike these studies, our study method allowed for prospective examination of associations between adiposity indexes and higher cIMT values without the effects of confounders such as smoking and a sedentary lifestyle which are normally associated with older study populations.

In the present study, using the maternal BMI and MUAC at enrollment, smoking mothers were significantly shorter and smaller compared to the mothers of the control group. The shorter smoking mother might be a type of mother who tends to have shorter children. More importantly, a mother who smokes and consumes alcohol and who continues to smoke and consume alcohol during her pregnancy, differs from a mother who abstains [20]. The association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and LBW infants was first reported in 1957 [19], subsequently Butler et al. [32] and Perkins et al. [33] also described these effect of in utero nicotine exposure and LBW. In the present study, exclusive alcohol consumption without smoking during pregnancy was not related to LBW or lower BL. These findings are consistent with those of other studies were BW was not affected by in utero alcohol exposure [34,35]. However, findings from the present study, are consistent with the findings of Butler et al. [32] and Perkins et al. [33]. Furthermore, in the present study, BP measurements were not significantly associated with higher IMT values but, instead, BP measurements correlated significantly with the child’s BMI, indicating an association between BP and adiposity. This finding is in agreement with findings by other studies [36]. Edstedt Bonamy et al. [36] described an association between in utero exposure to nicotine as well as male sex and higher IMT values in an adolescent population but also no association with BP.

Furthermore, in the present study, the LBW children remained smaller and shorter at age 5 years. They had significantly lower weight, height, skin fold thickness, and WC as well as left cIMT values at age 5 years. More importantly, measures of adiposity including SFT and WC at age 5 years, were significantly associated with higher aorta and carotid IMT values. This finding not only illustrates the importance of adiposity but also suggests body composition [19,37] might be more sensitive measurement than BMI alone in cardio-metabolic risk assessment.

Furthermore, maternal smoking during pregnancy is related to preterm birth and IUGR which in turn is associated to higher IMT in offspring [36,38–40]. Several other studies [25,26,41] describe the association between higher IMT values and a high cardiometabolic risk profile including HPT, DM type I, and hypercholesterolemia in children.

Interestingly, the present study found dual in utero exposure was significantly associated with higher right cIMT, but not left cIMT values. Anatomically, the left carotid artery arises directly from the aortic arch and the expected pressure on the left side is higher compared to the right carotid artery which arises from the brachiocephalic artery and the expected pressure might be lower [42]. This lower pressure might contribute to development of atherosclerosis more easily in the right carotid artery. Contrasting, according to several studies [42], the left carotid artery is more vulnerable for the development of atherosclerosis because of its anatomy and hemodynamics. Furthermore, HR measurements at age five correlated significantly and negatively with higher cIMT values.

Pereira et al. [43] also found an association between carotid atherosclerosis and impaired cardiac autonomic control, leading to decreased HR, in high risk individuals [43].

Strength and limitations

Some of the limitations need to be addressed. First, maternal prepregnancy weight as well as weight gain during pregnancy was not recorded. Second, data on fathers were not available. Although other studies confirm cardiovascular risk factors in offspring to be positively associated with risk factors from both mother and father, this disputes against in utero exposure and more in favor of a genetic predisposition of cardiovascular risk factors in offspring which was not the scope of this study. Lastly, cardiovascular function was not tested and food frequency questionnaire, physical activity of the children as well as information on exposure to environmental endocrine disrupters were not recorded. Several studies have examined the effects of passive smoking and endocrine disrupters to impact on the development of obesity, in addition to in utero exposure to nicotine. Strengths of this study are the sample size, availability of prospective data from the SPS and the high follow up and good compliance rate.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings suggest that dual alcohol and nicotine exposure, as well as the sex of the child and maternal adiposity (MUAC and BMI), are associated with higher cIMT values in pediatric patients, of our study population, at 5 years of age. From converging lines of evidence, our study confirms the detrimental effects of in utero alcohol and nicotine exposure on the development of early atherosclerotic changes in high-risk children from a low-income setting.

Acknowledgements

We would to thank all the participants and the mothers/caregivers of the research study for their participation.

Funding

The Safe Passage Study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders: [U01 HD055154], [U01 HD045935], [U01 HD055155], [U01 HD045991], and [U01 AA016501]. The present study was partly funded by the South African Sugar Association. We would also like to acknowledge Paulson for the donation received.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Phaswana-Mafuya N, Peltzer K, Chirinda W. Self-reported prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases and associated factors among older adults in South Africa. Glob Health Action 2013;6(1):20936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Balakumar P, Maung UK, Jagadeesh G. Prevalence and prevention of cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol Res 2016;113(A):600–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sachdev HS, Fall CH, Osmond C, et al. Anthropometric indicators of body composition in young adults: relation to size at birth and serial measurements of body mass index in childhood in the New Delhi birth cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82(2): 456–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lorber D Importance of cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther 2014;7: 169–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Benschop L, Schalekamp-Timmermans S, Roeters van Lennep JE, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors track from mother to child. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7(19): e009536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rodrigues AN, Abreu GR, Resende RS, et al. Cardiovascular risk factor investigation: a pediatric issue. Int J Gen Med 2013;6:57–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Daniels SR, Pratt CA, Hayman LL, et al. Reduction of risk for cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents. Circulation 2011;124(15):1673–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 2008;371(9609):340–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Black C, Moon G, Baird J. Dietary inequalities: what is the evidence for the effect of the neighbourhood food environment? Health Place 2014;27:229–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Winickoff JP, Nabi-Burza E, Chang Y, et al. Implementation of a parental tobacco control intervention in pediatric practice. Pediatrics 2013;132(1): 109–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jones NRV, Conklin AI, Suhrcke M, et al. The growing price gap between more and less healthy foods: analysis of a novel longitudinal UK dataset. PLoS One 2014;9(10):e109343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pechey R, Monsivais P, Ng YL, et al. Why don’t poor men eat fruit? Socioeconomic differences in motivations for fruit consumption. Appetite 2015;84: 271–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liu RS, Mensah FK, Carlin J, et al. Socioeconomic position is associated with carotid intima-media thickness in mid-childhood: the longitudinal study of Australian children. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6(8):e005925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mitanchez D, Jacqueminet S, Nizard J, et al. Effect of maternal obesity on birthweight and neonatal fat mass: a prospective clinical trial. PLoS One 2017; 12(7):e0181307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yajnik CS, Fall CHD, Coyaji KJ, et al. Neonatal anthropometry: the thin-fat Indian baby. The Pune Maternal Nutrition Study. Int J Obes 2003;27(2):173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brands B, Demmelmair H, Koletzko B, et al. How growth due to infant nutrition influences obesity and later disease risk. Acta Paediatr 2014;103(6):578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Haugen AC, Schug TT, Collman G, et al. Evolution of DOHaD: the impact of environmental health sciences. J Dev Orig Health Dis 2015;6(2):55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stanner SA, Bulmer K, Andrès C, et al. Does malnutrition in utero determine diabetes and coronary heart disease in adulthood? Results from the Leningrad siege study, a cross sectional study. Br Med J 1997; 315(7119):1342–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cornelius MD, Day NL. The effects of tobacco use during and after pregnancy on exposed children. Alcohol Res Health 2000;24(4):242–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hamułka J, Zielińska MA, Chądzyńska K. The combined effects of alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy on birth outcomes. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 2018;69(1):45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dukes KA, Burd L, Elliott AJ, et al. The safe passage study: design, methods, recruitment, and follow-up approach. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2014;28(5): 455–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Touboul PJ, Hennerici MG, Meairs S, et al. Mannheim carotid intima-media thickness and plaque consensus (2004–2006–2011). An update on behalf of the advisory board of the 3rd, 4th and 5th watching the risk symposia, at the 13th, 15th and 20th European Stroke Conferences, Mannheim, Germany, 2004, Brussels, Belgium, 2006, and Hamburg, Germany, 2011. Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;34(4):290–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pauciullo P, Iannuzzi A, Sartorio R, et al. Increased intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery in hypercholesterolemic children. Arterioscler Thromb 1994;14(7):1075–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Berenson GS, Srinivasan SR, Bao W, et al. Association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in children and young adults. The Bogalusa Heart Study. N Engl J Med 1998;338(23): 1650–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Järvisalo MJ, Jartti L, Näntö-Salonen K, et al. Increased aortic intima-media thickness: a marker of preclinical atherosclerosis in high-risk children. Circulation 2001; 104(24):2943–2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Harrington J, Peña AS, Gent R, et al. Aortic intima media thickness is an early marker of atherosclerosis in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr 2010;156(2):237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Geerts CC, Bots ML, Grobbee DE, et al. Parental smoking and vascular damage in young adult offspring: is early life exposure critical? The atherosclerosis risk in young adults study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008;28(12):2296–2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chen M, Zhang L. Epigenetic mechanisms in developmental programming of adult disease. Drug Discov Today 2011;16(23–24):1007–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jones JE, Jurgens JA, Evans SA, et al. Mechanisms of fetal programming in hypertension. Int J Pediatr 2012;2012:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Shisana O, Labadarios D, Rehle T, et al. SANHANES-1 team. The South African National Health and Nutrition Examination survey 2012: SANHANES-1: the health and nutritional status of the nation Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Park MH, Skow Á, De Matteis S, et al. Adiposity and carotid-intima media thickness in children and adolescents: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr 2015; 15(1):161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Butler NR, Goldstein H, Ross EM. Cigarette smoking in pregnancy: its influence on birth weight and perinatal mortality. Br Med J 1972;2(5806):127–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Perkins SL, Belcher JM, Livesey JF. A Canadian Tertiary Care Centre Study of maternal and umbilical cord cotinine levels as markers of smoking during pregnancy: relationship to neonatal effects. Can J Public Health 1997;88(4):232–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gallo PV, Weinberg J. Organ growth and cellular development in ethanol-exposed rats. Alcohol 1986; 3(4):261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chen Y, Dangardt F, Osika W, et al. Age- and sex-related differences in vascular function and vascular response to mental stress. Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies in a cohort of healthy children and adolescents. Atherosclerosis 2012;220(1):269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Edstedt Bonamy AK, Bengtsson J, Nagy Z, et al. Preterm birth and maternal smoking in pregnancy are strong risk factors for aortic narrowing in adolescence. Acta Paediatr 2008;97(8):1080–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Weber DR, Leonard MB, Zemel BS. Body composition analysis in the pediatric population. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2012;10(1):130–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Cosmi E, Visentin S, Fanelli T, et al. Aortic intima media thickness in fetuses and children with intrauterine growth restriction. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 114(5):1109–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zanardo V, Fanelli T, Weiner G, et al. Intrauterine growth restriction is associated with persistent aortic wall thickening and glomerular proteinuria during infancy. Kidney Int 2011;80(1):119–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gomez-Roig MD, Mazarico E, Valladares E, et al. Aortic intima-media thickness and aortic diameter in small for gestational age and growth restricted fetuses. PLoS One 2015;10(5):e0126842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Slyper AH. The pediatric obesity epidemic: causes and controversies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89(6): 2540–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ionescu A-M, Carciumaru N, Chirila S. Carotid artery disease – left vs right. ARS Med Tomitana 2016;22(3): 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Pereira VL, Dobre M, dos Santos SG, et al. Association between carotid intima media thickness and heart rate variability in adults at increased cardiovascular risk. Front Physiol 2017;8(248):248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]