Abstract

Purpose

Despite curative resection, the 5-year survival for patients with resectable pancreatic cancer is less than 20%. Recurrence occurs both locally and at distant sites and effective multimodality adjuvant treatment is needed.

Materials and Methods

Patients with curatively resected stage IB-IIB pancreatic adenocarcinoma were eligible. Treatment consisted of chemotherapy with gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 and cisplatin 60 mg/m2 on day 1 every 3 weeks for two cycles, followed by chemoradiotherapy (50.4 Gy/28 fx) with weekly gemcitabine (300 mg/m2/wk), and then gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks for four cycles. The primary endpoint was 1-year disease-free survival rate. The secondary endpoints were disease-free survival, overall survival, and safety.

Results

Seventy-four patients were enrolled. One-year disease-free survival rate was 57.9%. Median disease-free and overall survival were 15.0 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 11.6 to 18.4) and 33.0 months (95% CI, 21.8 to 44.2), respectively. At the median follow-up of 32 months, 57 patients (77.0%) had recurrence including 11 patients whose recurrence was during the adjuvant treatment. Most of the recurrences were systemic (52 patients). Stage at the time of diagnosis (70.0% in IIA, 51.2% in IIB, p=0.006) were significantly related with 1-year disease-free survival rate. Toxicities were generally tolerable, with 53 events of grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicity and four patients with febrile neutropenia.

Conclusion

Adjuvant gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy with gemcitabine and maintenance gemcitabine showed efficacy and good tolerability in curatively resected pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: Pancreatic neoplasms, Chemoradiotherapy, Gemcitabine, Cisplatin

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is a disease with dismal prognosis even after curative resection and adjuvant treatments [1]. Most patients present with advanced disease at diagnosis, with only 10%–20% of patients have resectable disease. With the improvement in operative techniques, postoperative complication and mortality has declined significantly, however, despite curative resection for pancreatic cancer, the survival rate in these patients still remains poor. Five-year overall survival (OS) for pancreatic cancer is less than 10%, ranked at the lowest survival across all cancer types [2].

Chemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) has been tested in the adjuvant setting after resection, but results differ with trials showing positive (GITSG) [3], no (EORTC) [4], or negative (ESPAC-1) [5] effects on survival. But ESPAC-1 trial has been criticized for possible selection bias derived from its original 2×2 factorial design, a concern of suboptimal radiotherapy without adequate quality assurance, lack of post-radiotherapy adjuvant chemotherapy, and allowing the final radiotherapy dose to be left to the judgement of the treating physician [1,6]. Also, the high risk of local failure after resection of pancreatic cancer, which ranges from 19.3% to 34.0% [4,7–10], and the high rate of positive retroperitoneal margins constitutes the rationale for chemoradiotherapy as an adjuvant treatment. Furthermore, the potential therapeutic benefit of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy has been reported [11,12].

Recent trials of adjuvant chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer showed prolonged disease-free survival (DFS) and OS with intensified multi-agent regimens such as FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine/capecitabine [7,8,13,14]. In the era of the proven benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy, the benefit of chemoradiotherapy when added to chemotherapy remains less understood [15]. Indeed, recent guidelines still include chemoradiotherapy as a viable option for patients with curatively resected pancreatic cancer [16,17]. Disease recurrence of pancreatic cancer occurs both locally and at the distant sites; thus, appropriate combination of local and systemic modalities is needed. This study was designed to test the efficacy and safety of postoperative adjuvant treatment regimen consisting of initial gemcitabine plus cisplatin chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy with gemcitabine followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine. This study was designed before the results of intensified chemotherapy as an adjuvant treatment are available and the optimal treatment remained controversial [7,8,13,14]. Initial chemotherapy was designed to eliminate micrometastasis, to spare unnecessary chemoradiotherapy in patients with early progression who develop metastasis shortly after operation, and to allow for recovery of nutritional balance and surgical healing. Gemcitabine plus cisplatin was chosen based on preclinical data and clinical efficacy in pancreatic cancer [18,19]. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy were intended to prevent both local and systemic recurrences.

Materials and Methods

1. Patients

Patients who had R0 resection of a stage IB-IIB pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma according to American Joint Committee on Cancer staging 6th edition, with 18–75 years of age, and of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status grade 0–2 were eligible.

Treatment had to start within 8 weeks from surgery; adequate bone marrow (leukocytes at least 3,000/mm3 or absolute neutrophil count at least 1,500/mm3. Platelet count at least 100,000/mm3), liver (aspartate aminotransferase less than 3 times upper limit of normal [ULN]), and kidney (creatinine no greater than 1.5 times ULN) functions were required.

Patients were excluded if they were exposed to prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy, had recurrent or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Those with previous or concurrent malignancies except for cured basal cell carcinoma of skin and carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix, active infections or heart failure, body weight reduction more than 10% from pre-morbid baseline, and pregnant or breast feeding women were also excluded.

Patients were enrolled from Seoul National University Hospital and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital.

2. Treatment plan

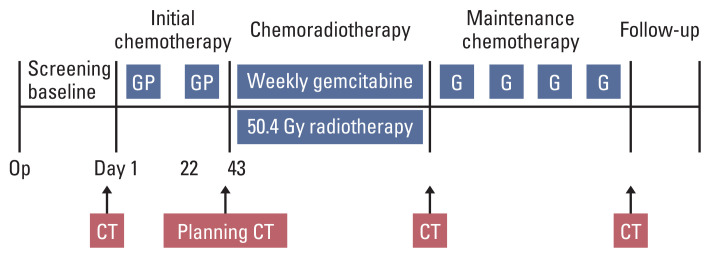

Initial chemotherapy started 4–8 weeks after R0 resection of pancreatic cancer. Patients received two cycles of gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 and cisplatin 60 mg/m2 on day 1 repeated every 3 weeks. Then concurrent chemoradiotherapy of 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions (field reduction at 45 Gy and boost field radiation 5.4 Gy) with weekly gemcitabine 300 mg/m2 was given after completion of initial chemotherapy, no later than 16 weeks after the operation. Chemoradiotherapy was followed by maintenance chemotherapy with four cycles of gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks. Overall treatment scheme is as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Treatment scheme. CT, computed tomography; G, gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks; GP, gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 and cisplatin 60 mg/m2 on day 1 repeated every 3 weeks; Weekly gemcitabine, gemcitabine 300 mg/m2 every week.

3. Statistical methods

Primary endpoint was the probability of being disease-free at 1 year from surgery (1-year DFS rate), and secondary endpoints were 2-year DFS rate, median DFS, OS, and also safety data. DFS and OS were measured from the date of surgery to the date of disease recurrence or death, or to the last follow-up assessment, as appropriate.

The null hypothesis was 1-year DFS rate of 40%, and the alternative hypothesis was that of 55%, and 63 patients were needed for significance level of 0.05, statistical power of 0.80 and a one-sided test. Considering drop-out rate of 10%, calculated accrual goal was 70 patients. The intention-to-treat population comprised all eligible patients. The survival analyses were performed by the Kaplan-Meier method. All the probability values were from 2-sided tests.

Relative dose intensity (RDI, %) was calculated as delivered dose intensity (DDI)/planned dose intensity (PDI)×100. DDI was calculated as (delivered total dose, in mg/m2)/(actual time to complete chemotherapy with imputation for missed cycles, in days). PDI was calculated as (planned total dose, in mg/m2)/(standard time to complete chemotherapy, in days).

Results

1. Patients’ characteristics

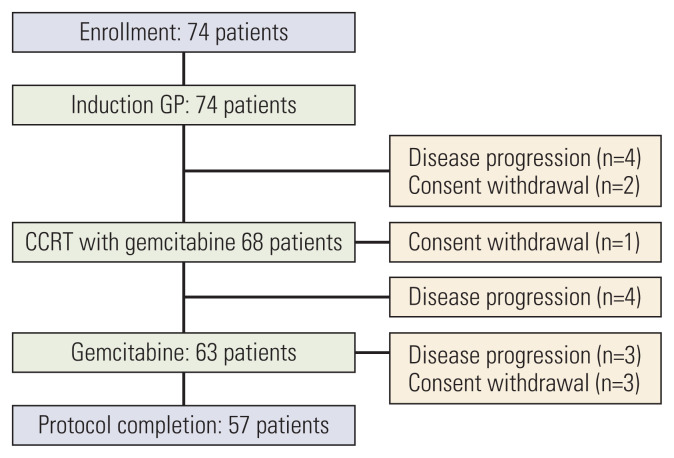

Between October 2005 and September 2009, 74 patients were enrolled; whose median age was 61 years old (range, 35 to 76 years). Baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients are shown in Table 1. The median time from resection to the start of adjuvant treatment was 6.4 weeks (range, 3.4 to 8 weeks). Chemoradiotherapy with gemcitabine was given to 68 patients, excluding four patients who had relapsed after two cycles of initial chemotherapy and two patients who withdrew the consent. Sixty-three patients underwent maintenance gemcitabine, as four patients had recurrent disease found after the chemoradiotherapy, and one patient withdrew consent with grade 3 nausea and vomiting during chemoradiotherapy. Finally, 57 patients completed the planned treatment, as three patients had recurrent cancer during maintenance chemotherapy and three withdrew consent due to one gastrointestinal bleeding, one urosepsis, and one unknown cause (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range, yr) | 61 (35–76) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 26 (35.1) |

| Male | 48 (64.9) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 37 (50.0) |

| 1 | 36 (48.6) |

| 2 | 1 (1.4) |

| Stage | |

| IB | 1 (1.4) |

| IIA | 30 (40.5) |

| IIB | 43 (58.1) |

| Primary tumor (T category) | |

| 2 | 2 (2.7) |

| 3 | 72 (97.3) |

| Nodal status (N category) | |

| 0 | 31 (41.9) |

| 1 | 43 (58.1) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Fig. 2.

Disposition of the patients. CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; GP, gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 and cisplatin 60 mg/m2 on day 1 repeated every 3 weeks.

RDI for gemcitabine and cisplatin during initial chemotherapy was 81.3% and 83.7%, respectively. RDI for gemcitabine during chemoradiotherapy and maintenance chemotherapy was 83.7% and 88.9%, respectively.

2. DFS and OS

Median follow-up time was 32 months (range, 6 to 115 months), and 57 patients (77.0%) had recurrence of pancreatic cancer, 52 with systemic metastases, and five with locoregional relapse. Among five patients with locoregional relapse, one could not commence chemoradiotherapy due to disease progression after initial chemotherapy and the others finished the planned treatment. Among patients with distant metastases, involved organs were liver in 29 patients, lung in eight, distant intra-abdominal lymph nodes in eight, peritoneum in 12, and others in five. One patient had recurrent cancer in both local and distant site.

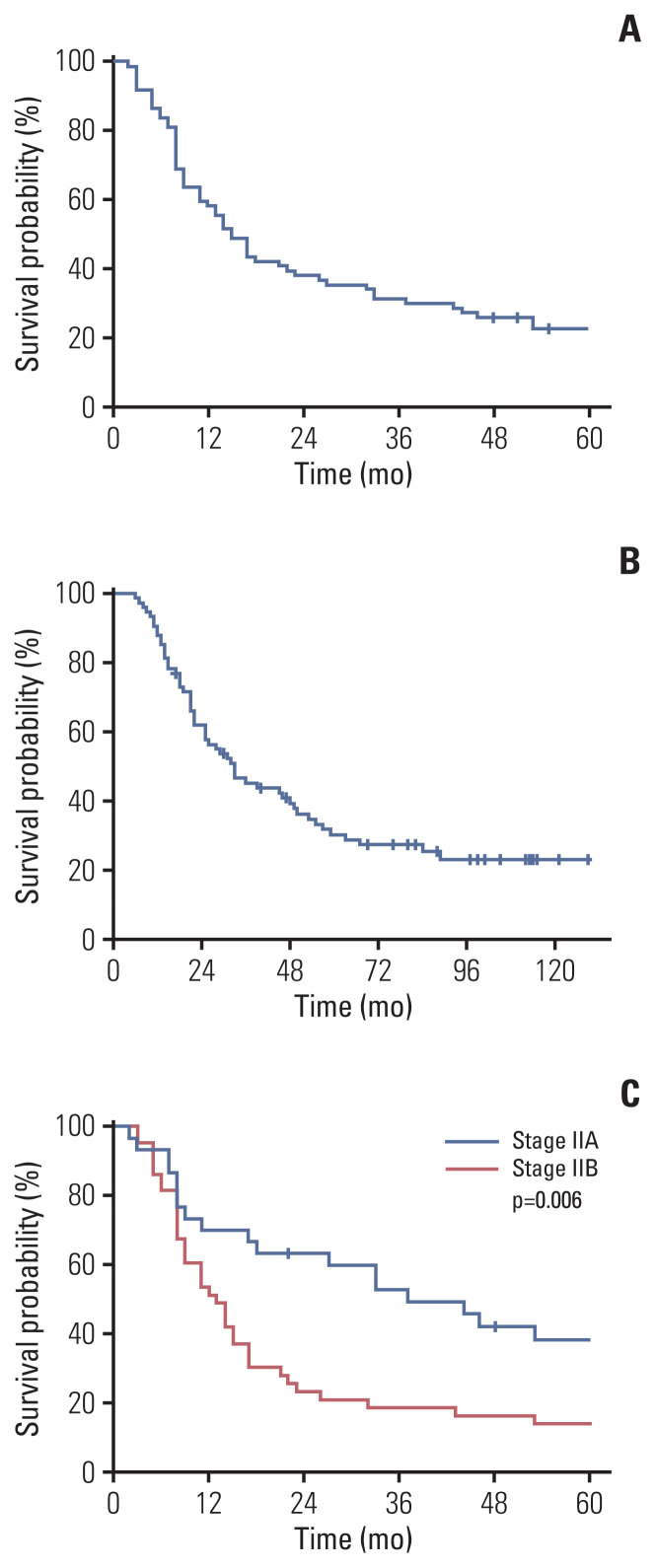

Kaplan-Meier curve for DFS and OS are presented in Fig. 3A and B, respectively. One-year DFS rate, which was the primary endpoint, was 57.9%. Two-year DFS rate was 36.7%. Median DFS was 15.0 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 11.6 to 18.4). DFS was significantly associated with stage (p=0.006). One-year DFS rate for stage IIA patients was 70.0 %, and 51.2 % for stage IIB (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier plots of disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). (A) DFS of patients. One-year DFS rate, which was the primary endpoint, was 57.9%. Median disease-free survival was 15.0 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 11.6 to 18.4). (B) OS of patients. Median OS was 33.0 months (95% CI, 21.8 to 44.2). (C) DFS according to stage (stage IIA vs. IIB). One-year DFS rate for stage IIA and IIB was 70.0% and 51.2%, respectively (p=0.006).

Fifty-four patients (73.0%) died and median OS was 33.0 months (95% CI, 21.8 to 44.2). Median OS for stage IIA and IIB was 46 months (95% CI, 24.5 to 67.5) and 26 months (95% CI, 17.2 to 34.8), respectively (p=0.189).

3. Safety

Neutropenia was the most common side effect throughout the study treatment. Twenty-three patients (31.1%) suffered from transient grade 3–4 neutropenia during initial chemotherapy period, nine (13.2%) during chemoradiotherapy, and 13 (20.6%) during maintenance gemcitabine. However, there were only four events (5.4%) of febrile neutropenia and the study treatment was generally tolerable. Febrile neutropenia occurred during initial and maintenance chemotherapy, and not during chemoradiotherapy. Safety data are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Toxicities according to the treatment phase

| Grade | Initial gemcitabine/cisplatin (74 patients) | CCRT with gemcitabine (68 patients) | Maintenance gemcitabine (63 patients) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematologic | ||||

| Neutropeniaa) | 3 | 17 (23.0) | 9 (13.2) | 8 (12.7) |

| 4 | 6 (8.1) | 0 | 5 (7.9) | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 2 (3.2) |

| Anemia | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 (6.3) |

| Non-hematologic | ||||

| Nausea/Vomiting | 3 | 2 (2.8) | 3 (4.4) | 1 (1.6) |

| Anorexia | 3 | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 3 | 1 (1.4) | 3 (4.4) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 3 | 0 | 3 (4.4) | 0 |

| GI bleeding | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.6) |

Values are presented as number (%). CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; GI, gastrointestinal.

Febrile neutropenia: 4 events.

Discussion

Optimal adjuvant therapy remains a challenge and better strategies to decrease both local and distant recurrences are eagerly needed for patients suffering from pancreatic cancer. We evaluated the efficacy of the combined modality treatment comprised of initial chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy and maintenance chemotherapy. DFS rate at 1 year, which is the primary endpoint, of 57.9% is numerically high in the context of previous adjuvant trials in pancreatic cancer (Table 3), although direct comparison is not feasible.

Table 3.

Summary of recent adjuvant trials

| Trial | Regimen of adjuvant therapy | Median OS (mo) | 1-Year survival (%) | 2-Year survival (%) | 3-Year survival (%) | 5-Year survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GITSG [27] | RT/FU | 21 | - | 43 | - | 19 |

| EORTC [9] | RT/FU | 17.1 | - | 34 | - | - |

| ESPAC-1 [5] | CCRT/FU | 15.9 | - | 29 | - | 13 |

| CCRT/FU+FL | 19.9 | - | - | - | 10 | |

| CONKO-001 [10] | Gemcitabine | 22.1 | 72.5 | 47.5 | 34 | 22.5 |

| RTOG 97-04 [4] | Gemcitabine+CCRT/FU+gemcitabine | 20.5 | - | - | 31 | - |

| ESPAC-3 [28] | Gemcitabine | 23.6 | 80.1 | 49.1 | - | - |

| FL | 23 | 78.5 | 48.1 | - | - | |

| JASPAC-01 [8] | S-1 | - | - | 59.7 | - | 44.1 |

| Gemcitabine | - | - | 38.8 | - | 24.4 | |

| PRODIGE [13] | Modified FOLFIRINOX | 54.4 | - | - | 63.4 | - |

| Gemcitabine | 35.0 | - | - | 48.6 | - | |

| ESPAC-4 [7] | Gemcitabine/Capecitabine | 28.0 | 84.1 | 53.8 | - | - |

| Gemcitabine | 25.5 | 80.5 | 52.1 | - | - | |

| APACT [14] | Nab-paclitaxel/Gemcitabine | 40.5 | - | - | - | - |

| Gemcitabine | 36.2 | - | - | - | - | |

| Present study | GP+CCRT/gemcitabine+gemcitabine | 33.0 | 91.6 | 63.5 | 47.0 | - |

CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; FL, fluorouracil and leucovorin; FU, fluorouracil; GP, gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 and cisplatin 60 mg/m2 on day 1 repeated every 3 weeks; OS, overall survival; RT, radiotherapy.

Our study combines both initial and maintenance chemotherapy before and after the chemoradiotherapy with gemcitabine. The purpose of initial chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin doublet is to eradicate micrometastasis earlier in the adjuvant treatment period, to allow patient’s postoperative recovery period before chemoradiotherapy, and also to screen out patients with early relapse not requiring chemoradiotherapy. In the present study, there were four patients with relapse out of 74 enrolled patients during the initial period. Chemoradiotherapy with gemcitabine was intended to reduce locoregional recurrences, and local recurrences were present in only six patients (8.1%), including one with both local and distant recurrences. The local recurrence rate in this study is much lower than those in the other studies ranging from 19.3% to 34.0% [4,7–10]. Although direct comparison is not possible due to different enrollment criteria, especially the inclusion of patients with positive resection margin, the efficacy of chemoradiotherapy is shown by the low local recurrence rate. Maintenance chemotherapy with gemcitabine was intended to reduce both local and distant recurrences and gemcitabine is considered as one of standard adjuvant treatment currently.

Present study used gemcitabine in combination with radiation. Gemcitabine has been shown to be a potent radiosensitizer and easily combined with radiation in pancreatic cancer [20–22]. Recommended doses for phase II trials range from 150 to 400 mg/m2/wk depending on radiation volume and timing of gemcitabine administration. But no data indicate a dose-response relationship of radiosensitizing effect of gemcitabine [23]. To minimize toxicities of the concurrent gemcitabine and radiation, gemcitabine was preferably given on the beginning of each radiation treatment week at a dose of 300 mg/m2/wk. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with gemcitabine was well tolerated with no grade 4 or higher toxicity in the present study.

Cisplatin, when combined with antimetabolites such as gemcitabine or 5-FU, showed more favorable response rate and progression-free survival, although failed to demonstrate the OS benefit compared with gemcitabine in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma [24–26]. Gemcitabine plus cisplatin provides the response rate of 11%–31% and median survival of 7.1–9.6 months in advanced pancreatic cancer [19]. Intensified initial regimens are needed early in the course of adjuvant therapy for eradication of micrometastatic disease, and we adopted gemcitabine and cisplatin. The doublet regimen was feasible and tolerable for the patients after receiving operation as shown in the present study.

Survival results of the present study is numerically better than other adjuvant trials (Table 3), although direct comparison is not feasible. These trials included patients regardless of R0 or R1 resection, including patients with microscopic residual disease. In contrast, only patients with R0 resection were eligible in the present study, excluding patients with microscopic residual disease. Moreover, our study enrolled only physically fit patients, as those with more than 10% reduction of body weight from pre-morbid usual weight were excluded. These could have contributed to the homogeneity of enrolled patients and better outcome compared to the previous studies. On the other hand, the effect of local modality such as chemoradiotherapy could have been underestimated in these patients whose cancer had been completely resected.

In the present study, initial chemotherapy was designed to eliminate micrometastasis and to spare unnecessary chemoradiotherapy in patients with early progression who develop metastasis shortly after operation. In the present study, however, patients with disease progression during initial phase was only about 5% (4 out of 74). Another potential benefit of upfront chemotherapy is earlier delivery of adjuvant treatment. Systemic chemotherapy can be instituted somewhat sooner in the postoperative period than radiotherapy to the upper abdomen. In the past, it was not uncommon to have chemoradiotherapy delayed to the 7th or 8th postoperative week to allow for recovery of nutritional balance and surgical healing. Upfront chemotherapy could allow earlier initiation of therapy with minimal delay for chemoradiotherapy. In fact, for patients starting chemotherapy in postoperative week 4, it is likely that chemoradiotherapy will begin in postoperative week 10, resulting in little delay over standard practice whatsoever and with a significantly earlier onset of postoperative therapy as a whole.

Stage is one of the most important prognostic indicator in pancreatic cancer. Moreover, DFS is known to be a surrogate endpoint for OS in adjuvant trials of pancreatic cancer [29]. Indeed, we observed significant difference in DFS according to the stage at diagnosis in our homogenous patients. Although the median OS for stage IIA was numerically longer than stage IIB (46 months vs. 26 months), the difference in OS was not significant (p=0.189), which might reflect the lack of statistical power to validate OS according to the stage in these homogeneous population. The DFS curves diverged widely according to the stage in the present study (Fig. 3C) than in the previous reports [30]. One explanation could be the effectiveness of the treatment regimen in node-negative patients, which could not be fully analyzed in this single-arm study.

In conclusion, adjuvant gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy with gemcitabine and maintenance gemcitabine showed efficacy and good tolerability in curatively resected pancreatic cancer.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to the memory of the late Professor Sung W. Ha, without whom this study would not have been completed. His dedication to improving cancer treatment will continue to inspire us all. Gemcitabine was provided by Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, IN).

Footnotes

Ethical Statement

The protocol was approved by the local ethics committees of the participating institutions (IRB No H-0412-138-006 and No B-0412/015-006) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of good clinical practice, the ethical principles stated in the current revision of the Declaration of Helsinki, and local legal and regulatory requirements. Written, informed consent was obtained from all patients. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT013966-81).

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the analysis: Chie EK, Im SA, Kim JH, Oh DY, Jang JY, Kim JS, Bang YJ, Kim SW, Ha SW.

Collected the data: Lee KH, Kim JH, Kwon J, Jang JY.

Contributed data or analysis tools: Lee KH, Chie EK, Im SA, Kim JH, Han SW, Oh DY, Jang JY, Kim JS, Kim TY, Bang YJ, Kim SW, Ha SW.

Performed the analysis: Lee KH, Chie EK, Kwon J.

Wrote the paper: Lee KH, Chie EK.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflict of interest relevant to this article was not reported.

References

- 1.Saif MW. Controversies in the adjuvant treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. JOP. 2007;8:545–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalser MH, Ellenberg SS. Pancreatic cancer: adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection. Arch Surg. 1985;120:899–903. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390320023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams RA, Safran H, Hoffman JP, Konski A, et al. Fluorouracil vs gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1019–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, Bassi C, Dunn JA, Hickey H, et al. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1200–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz MH, Fleming JB, Lee JE, Pisters PW. Current status of adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15:1205–13. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, Psarelli EE, Valle JW, Halloran CM, et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1011–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32409-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uesaka K, Boku N, Fukutomi A, Okamura Y, Konishi M, Matsumoto I, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy of S-1 versus gemcitabine for resected pancreatic cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial (JASPAC 01) Lancet. 2016;388:248–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, van Pel R, Couvreur ML, Veenhof CH, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg. 1999;230:776–82. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199912000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, Gellert K, Langrehr J, Ridwelski K, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:267–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corsini MM, Miller RC, Haddock MG, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, Nagorney DM, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy for pancreatic carcinoma: the Mayo Clinic experience (1975–2005) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3511–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herman JM, Swartz MJ, Hsu CC, Winter J, Pawlik TM, Sugar E, et al. Analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: results of a large, prospectively collected database at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3503–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, Ben Abdelghani M, Wei AC, Raoul JL, et al. FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2395–406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tempero MA, Reni M, Riess H, Pelzer U, O’Reilly EM, Winter JM, et al. APACT: phase III, multicenter, international, open-label, randomized trial of adjuvant nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine (nab-P/G) vs gemcitabine (G) for surgically resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15 Suppl):4000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liao WC, Chien KL, Lin YL, Wu MS, Lin JT, Wang HP, et al. Adjuvant treatments for resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1095–103. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, version 1. 2020 [Internet] Plymouth Meeting, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2020. [cited 2020 Feb 20]. Available from: https://www2.tri-kobe.org/nccn/guideline/pancreas/english/pancreatic.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khorana AA, Mangu PB, Berlin J, Engebretson A, Hong TS, Maitra A, et al. Potentially curable pancreatic cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2541–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.5553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters GJ, Ruiz van Haperen VW, Bergman AM, Veerman G, Smitskamp-Wilms E, van Moorsel CJ, et al. Preclinical combination therapy with gemcitabine and mechanisms of resistance. Semin Oncol. 1996;23(5 Suppl 10):16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Philip PA. Gemcitabine and platinum combinations in pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2002;95(4 Suppl):908–11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blackstock AW, Bernard SA, Richards F, Eagle KS, Case LD, Poole ME, et al. Phase I trial of twice-weekly gemcitabine and concurrent radiation in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2208–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Laethem JL, Demols A, Gay F, Closon MT, Collette M, Polus M, et al. Postoperative adjuvant gemcitabine and concurrent radiation after curative resection of pancreatic head carcinoma: a phase II study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:974–80. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crane CH, Wolff RA, Abbruzzese JL, Evans DB, Milas L, Mason K, et al. Combining gemcitabine with radiation in pancreatic cancer: understanding important variables influencing the therapeutic index. Semin Oncol. 2001;28(3 Suppl 10):25–33. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2001.22536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGinn CJ, Lawrence TS, Zalupski MM. On the development of gemcitabine-based chemoradiotherapy regimens in pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2002;95(4 Suppl):933–40. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colucci G, Giuliani F, Gebbia V, Biglietto M, Rabitti P, Uomo G, et al. Gemcitabine alone or with cisplatin for the treatment of patients with locally advanced and/or metastatic pancreatic carcinoma: a prospective, randomized phase III study of the Gruppo Oncologia dell’Italia Meridionale. Cancer. 2002;94:902–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, Gonnermann M, Schonekas H, Rost A, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3946–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ducreux M, Rougier P, Pignon JP, Douillard JY, Seitz JF, Bugat R, et al. A randomised trial comparing 5-FU with 5-FU plus cisplatin in advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1185–91. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Further evidence of effective adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection of pancreatic cancer. Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. Cancer. 1987;59:2006–10. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870615)59:12<2006::aid-cncr2820591206>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, Ghaneh P, Cunningham D, Goldstein D, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1073–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nie RC, Zou XB, Yuan SQ, Chen YB, Chen S, Chen YM, et al. Disease-free survival as a surrogate endpoint for overall survival in adjuvant trials of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of 20 randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:421. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06910-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, Ritchey J, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, et al. Validation of the 6th edition AJCC Pancreatic Cancer Staging System: report from the National Cancer Database. Cancer. 2007;110:738–44. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]