Abstract

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a common microvascular complication in the late stages of diabetes. Currently, the etiology and pathogenesis of DN are not well understood. Even so, available evidence shows its development is associated with metabolism, oxidative stress, cytokine interaction, genetic factors, and renal microvascular disease. Diabetic nephropathy can lead to proteinuria, edema and hypertension, among other complications. In severe cases, it can cause life-threatening complications such as renal failure. Patients with type 1 diabetes, hypertension, high protein intake, and smokers have a higher risk of developing DN. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) regulates several human processes essential for normal development. Even though FGF has been implicated in the pathological development of DN, the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. This review summarizes the role of FGF in the development of DN. Moreover, the association of FGF with metabolism, inflammation, oxidative stress and fibrosis in the context of DN is discussed. Findings of this review are expected to deepen our understanding of DN and generate ideas for developing effective prevention and treatments for the disease.

Keywords: fibroblast growth factor, diabetic nephropathy, signaling pathways, pharmacological action, renal fibrosis

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder associated with chronic microvascular and macrovascular complications. Diabetes leads to numerous serious complications including diabetic retinopathy, diabetic foot ulcers and diabetic nephropathy (DN).1 DN is one of the most common and severe chronic microvascular complications associated with diabetes, and the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the world.2 About 20–50% of people with diabetes may develop DN.3 In addition, about 50% of DN patients develop ESRD, which substantially increasing the mortality rate of patients with DN.4

The main pathological features of DN include morphological, ultrastructural, and functional changes in diabetic kidneys, glomerular hypertrophy, proteinuria, decreased glomerular filtration rate and renal fibrosis, all of which disrupt renal function.5 Clinically, DN syndrome is characterized by microalbuminuria or albuminuria. The disease progresses through five stages: initial glomerular hyperfiltration and renal hypertrophy, post-exercise microalbuminuria, persistent microalbuminuria, renal dysfunction, and renal failure. The onset of DN is difficult to detect, and once albuminuria sets in, disease progression is irreversible. DN patients are 14 times more likely to progress to end-stage renal disease, relative patients with other kidney diseases.6 Presently, DN treatment relies on reducing cardiovascular risk and blood glucose, blood pressure management, and inhibition of angiotensin enzyme activity.7 In China, the prevalence of diabetes in recent years has parallelled the increase in diabetes-related chronic kidney diseases, distinct from those associated with glomerulonephritis.8 Although therapeutic interventions can delay development and progression of DN, numerous patients still develop ESRD. The enormous social and economic burden imposed by DN continues to increase year by year. The limited knowledge on the pathogenesis of DN has complicated control and treatment efforts against the disease. This underlines the need to explore the pathogenesis as well effective prevention and treatment of DN.

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family is a group of structurally identical and multifunctional signal molecules that regulate numerous developmental, physiological and pathological processes in humans. FGFs regulate numerous biological and pathophysiological processes including angiogenesis, wound healing, embryonic development, and metabolism via the paracrine or endocrine system.9 In recent years, research focuses on understanding the mechanism underlying the relationship between FGF and diabetes as well as associated complications. At present, the treatment of DN relies on hypoglycemic drugs, which often results in serious side effects such as hypoglycemia. Given that FGF cannot cause hypoglycemia, it is potentially a safe therapeutic candidate for diabetes treatment. Previous studies have shown that FGF can alleviate inflammation, regulate lipid metabolism, reduce oxidative stress and improve insulin resistance. On the other hand, these factors are essential in the development of diabetes and related complications. However, the mechanism underlying this relationship remains to be validated.10–13 Overall, this paper reviews research progress on the relationship between FGF in DN.

Fibroblast Growth Factor Family

The FGF family consists of 23 members (FGF1-FGF23). In humans, only 22 FGFs have been described. FGF15 has not been reported in humans, similar to FGF19 which is also absent in rodents such as mice and rats. FGF19 is thought to be homologous to FGF15 in vertebrates.14 Among the 22 FGFs in mammals, FGF11 subfamily (FGF11, FGF12, FGF13, FGF14) are intracellular proteins that do not bind to FGF receptors (FGFRs).15 According to the sequence homology and phylogeny, remaining 18 FGFs can be divided into six subfamilies, including subfamily FGF1 (FGF1, FGF2), FGF4 (FGF4, FGF5, FGF6), FGF7 (FGF3, FGF7, FGF10, FGF22), FGF 8 (FGF8, FGF17, FGF18), FGF9 (FGF9, FGF16, FGF20) and FGF19 (FGF19, FGF21, FGF23), who all regulate the endocrine system.16 In mammals, FGF signaling pathway regulates binding, activation and interaction of tyrosine kinase FGFRs with four signal molecules (FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3 and FGFR4). But the FGF11 subfamily does not secrete signals and has no definite interaction with FGFRs. It is a cofactor for voltage-gated sodium channels and other molecules17 (Table 1).

Table 1.

FGFs and Its Specific FGF Receptors

| FGF Subfamily | FGF | Cofactor | FGF Receptor Activity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paracrine Subfamily | FGF1 subfamily | FGF1 | HS | All FGFRs |

| FGF2 | FGFR1c,3c>2c,1b,4 | |||

| FGF4 subfamily | FGF4 | FGFR1c,2c>3c,4 | ||

| FGF5 | FGFR1c,2c>3c,4 | |||

| FGF6 | FGFR1c,2c>3c,4 | |||

| FGF7 subfamily | FGF3 | FGFR2b>1b | ||

| FGF7 | FGFR2b>1b | |||

| FGF10 | FGFR2b>1b | |||

| FGF22 | FGFR2b>1b | |||

| FGF8 subfamily | FGF8 | FGFR3c>4>2c>1c≫3b | ||

| FGF17 | FGFR3c>4>2c>1c≫3b | |||

| FGF18 | FGFR3c>4>2c>1c≫3b | |||

| FGF9 subfamily | FGF9 | FGFR3c>2c>1c,3b≫4 | ||

| FGF16 | FGFR3c>2c>1c,3b≫4 | |||

| FGF20 | FGFR3c>2c>1c,3b≫4 | |||

| Endocrine Subfamily | FGF19 subfamily | FGF19 | β-Klotho | FGFR1c,2c,3c,4 |

| FGF21 | FGFR1c,3c | |||

| FGF23 | α-Klotho | FGFR1c,2c,3c,4 | ||

| Non-signal FGFs Subfamily | FGF11 subfamily | FGF11 | Is not combined with FGFRs | |

| FGF12 | ||||

| FGF13 | ||||

| FGF14 | ||||

FGF signaling pathway regulates numerous fundamental cellular processes in different fashions based on the cell type and maturation stage. Initially, FGFs were thought to exclusively regulate proliferation of fibroblasts. However, emerging evidence shows that proliferation of fibroblasts is regulated by numerous cells including keratinocytes, immature osteoblasts, oligodendrocyte precursor cells, and endothelial cells. That aside, FGF also participates in differentiation and apoptosis of numerous cells,18 growth and development and protects tissues against fibrosis.19–21 Numerous studies have shown that FGF regulates almost all human growth and developmental as well as several physiological processes.

FGFR activates several signal transduction pathways such as embryonic development, tumor growth, angiogenesis, wound healing, and physiology during growth and developmental stages of mammals. Activation of FGFR is regulated by heparin, heparan sulfate or other glycosaminoglycans following specific binding between FGF and FGFRs.22 Unlike other growth factors, activation of FGFRs and induction of pleiotropic response is mediated synergistically by heparin and heparin sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG).23 Receptor dimerization is central to FGF signal transduction. Receptor dimerization activates its intrinsic tyrosine kinase to phosphorylate several tyrosine residues on the receptor. The resultant signal complex is assembled and recruited to the active receptor after a series of phosphorylation.24 Heparin plays a significant role in the process of receptor dimerization. FGF and helper heparin molecule preferentially bind to the open and dimerized complex, which shifts the equilibrium to the FGFR dimer, resulting in autophosphorylation and stimulation of tyrosine protein kinase (PTK) activity. Without heparin, the FGF-mediated and direct receptor–receptor interaction are insufficient to produce significant dimerization, underlining the critical role heparin cofactor plays in FGF signal transduction and regulation.23,25,26

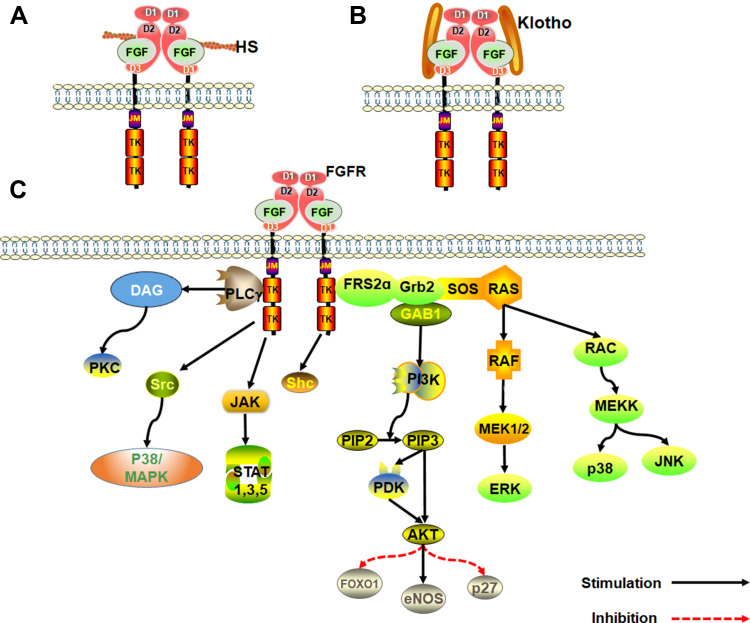

Klotho family of proteins are other key cofactors in FGF signal transduction. Because heparin-binding domain is absent in endocrine FGFs, they have a low affinity for heparan sulfate. As such, Klotho protein cofactor is essential in endocrine FGFs for the formation of FGF-FGFR-Klotho ternary complex.27,28 The Klotho family is composed of α and β-Klotho proteins. FGF19 and FGF21 binds β-Klotho protein, whereas FGF23 binds the α-Klotho protein. The FGF-Klotho endocrine axis regulates several physiological processes such as phosphate, glucose, fatty acid and bile acid metabolism, energy production, circadian rhythm and sympathetic activity as well as stress and aging. Accordingly, Klotho endocrine axis is a potential therapeutic target for treatment of multitudinous chronic diseases29,30 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An overview of the FGF signaling pathways. (A) Activation of FGFRs by FGFs via the paracrine pathway, mediated by HS cofactor. (B) Activation of FGFR by FGF-Klotho-FGFR ternary complex. The complex formation is regulated via the Endocrine pathway, mediated by Klotho protein cofactor. (C) Regulation of functioning of various signal transduction pathways such as growth and development in the human body by FGF-activated FGFR.

Development and Progression of DN

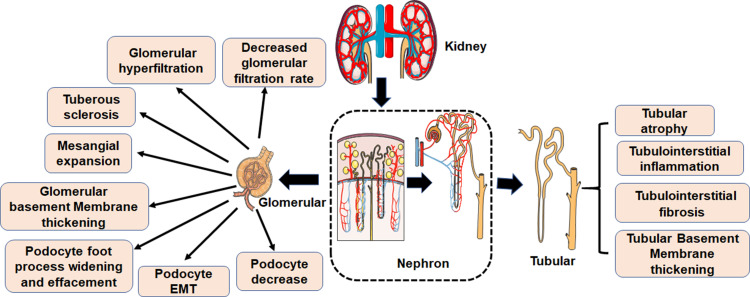

Microvascular and macrovascular complications and neuropathy are the main disorders associated with diabetes. They significantly disrupt the normal daily life of diabetics, and can even lead to disability or death. There are numerous diabetes-related complications, characterized by complex etiologies. The common pathologies are however related to blood glucose, inflammation, protein modification and turnover, gene regulation, redox imbalance, dyslipidemia, blood pressure, and many other factors. Even so, the pathogenesis of diabetes-related complications is not well understood.31 DN is the major complication related to diabetes and the main cause of ESRD. The clinical pathological manifestations of DN are mainly renal fibrosis and albuminuria. The major histological feature of classical diabetic nephropathy is diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Widening of the glomerular basement membrane, mesangial matrix accumulation, podocyte foot process widening and effacement, and loss of podocytes all occur (Figure 2). Mechanism underlying occurrence and development of DN are very complex, but include glomerular insulin resistance, glucose and lipid metabolism disorder, oxidative stress, inflammation, podocyte injury, and vascular endothelial dysfunction.32–34

Figure 2.

Pathological characteristics of DN. The first clinical manifestation of classical DN is the increase of urinary albumin excretion. The glomerular filtration rate is normal or even increased before urinary albumin excretion, but the glomerular filtration rate decreases after continuous urinary proteinuria, and eventually even developed into ESRD. And with increased urinary albumin excretion and an independent decline in glomerular filtration function, the patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease increases. According to the Tervaert classification of DN, the glomerular lesions of DN can be divided into four grades. I: Irregular thickening of the glomerular basement membrane was observed under an electron microscope. II: Mesangial hyperplasia and mesangial dilatation occur. III: There is at least one recognized tuberous sclerosis. IV: Advanced diabetic glomerulosclerosis of glomeruli.

Inflammation and the Development of DN

Increasing evidence shows that glomerular and tubulointerstitial inflammation plays a fundamental role in the development of DN. Therefore, exploring the relationship between renal inflammation and the occurrence and development of DN can uncover ways of preventing the occurrence of DN.35,36 Prolonged inflammation resulting from sustained renal injury may promote DN development. Glomerular endothelial cell injury is often accompanied by the expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines, resulting in infiltration of macrophage into renal tissues.37

Numerous studies show that moderate but chronic inflammation activates the innate immunity, which mediates the DN pathogenesis. Cytokines are the main regulatory and effector molecules in the inflammatory process. Meanwhile, inflammation is a critical process in the occurrence and development of diabetes and related complications. Several molecules and pathways related to inflammation participate in the occurrence and development of DN.38 Additionally, mild but prolonged inflammation and associated disorders including insulin resistance, high oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction and increased urinary albumin excretion participate in DN development.39 Kidney cells synthesize pro-inflammatory cytokines. Interestingly, chemokines and adhesion molecules are over-expressed in kidney cells of diabetic patients and animals. These molecules can attract circulating leukocytes such as monocytes, neutrophils and lymphocytes to the renal tissue, which causes mild renal injury. Cytokines and other inflammatory mediators secreted by the infiltrating immune cells exacerbate the renal injury, and sustain inflammatory response.40 Given the intricate relationship, therapeutic options for DN targeting inflammatory disease have been widely explored.

Oxidative Stress: Important Factor for DN

Numerous studies have shown that oxidative stress participates in the development of diabetic microvascular and cardiovascular complications. In particular, super-oxides activate several key pathways linked to diabetes complications.41 In DN, oxidative stress activates renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), polyol pathway, protein kinase C (PKC), advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and other pathways that damage the kidney. Oxidative stress that damage the kidney can be induced by other pathways such hyperglycemia, autophagy, inflammation.42 Accordingly, antioxidants are promising therapeutic potential against DN resulting from oxidative stress. However, the high renal perfusion rate limits the delivery and application of antioxidants.43 Nevertheless, anti-oxidative stress is still an important research direction in the treatment of DN.

Insulin Resistance

Insulin regulates glucose metabolism and biological function of specific cells and tissues. Insulin resistance and relative deficiency causes hyperglycemia, which participates in the development of diabetes and associated complications.44 For instance, insulin resistance is closely related to occurrence and progression of DN, through unclear mechanisms.45,46

The Main Pathogenesis of DN

DN development is mainly regulated via three pathways: 1) polyol and activation of PKC pathway is central to DN development DN. Particularly, the activation of PKC pathway increases capillary permeability, induces cellular stress and expression of both extracellular matrix (ECM) and transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), aggravating kidney injury.47 Besides, activation of the polyol pathway disrupts the intracellular tension, increases glycation, reduces anti-oxidation and enhances oxidative cell damage through varied mechanisms.48 2) Production of AGEs in a high-glucose environment disrupts glomerular functioning and activates the macrophages. Binding of AGEs and AGE receptors (RAGE) in kidney tissue induces oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, which ultimately damage the kidney.49 3) Hyperglycemia causes glomerulus glomerular hyper filtration and intraglomerular hypertension by activating the local RAAS. The high blood pressure in the glomerulus accelerates renal vascular complications. Moreover, angiotensin II produced by the RAAS can cause podocyte injury by increasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).50

DN is a complex process involving numerous but specific cells and molecules. Hyperglycemia drives progression of DN into ERSD. In hyperglycemia, complex changes in cell function, extracellular activity and hemodynamic effects production of AGES, hexosamine, polyol, ROS, and angiotensin II through different metabolic pathways. The molecules trigger several serious events which activate PKC, ERK, p38, JNK/SAPK, AGE-RAGE signaling pathways, as well as production of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and TGF-β1 to a crosstalk network. These processes lead to DN, characterized by kidney enlargement, mesangial matrix dilatation, glomerular basement membrane thickening, podocyte reduction, basement membrane thickening, interstitial fibrosis and eventually proteinuria.51 However, accumulating evidence shows that genes related to DN pathology are not just regulated through classical signaling pathways, but also epigenetically.52

The aforementioned mechanisms only represent a small fraction of the complex DN pathogenesis. At present, DN treatment mainly targets the aforementioned pathways. In clinical trials, the relationship between FGF and insulin resistance, fibrosis, RAAS, chronic kidney disease has been studied. However, there is still a lack of clinical drug research on FGF in DN (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ongoing Human Clinical Trials of FGF

| Status | Study | Sponsor | Condition | Intervention | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruiting | FGF23 and Angiotensin-(1-7) in Hypophosphatemia (GAP) | Wake Forest University Health Sciences | Hypophosphatemia; X-linked Hypophosphatemia; Renin-angiotensin System; Left Ventricular Hypertrophy |

Diagnostic Test: Ang II and Ang-(1-7) Diagnostic Test: FGF23 and klotho |

NA |

| Completed | Phosphate Intake’s Effect on the Skeletal System - Pilot | University of California, San Francisco | Healthy; Kidney Failure, Chronic |

Behavioral: dietary phosphorus | NA |

| Completed | Modulation of Insulin Sensitivity by Betaine Upregulation of FGF21 | UNC Nutrition Research Institute | Insulin Sensitivity | Dietary Supplement: Betaine Dietary Supplement: Dextrose |

NA |

| Active, not recruiting | A Study of Experimental Medication BMS-986036 in Adults With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) and Stage 3 Liver Fibrosis (FALCON 1) | Bristol-Myers Squibb | Liver Fibrosis; Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD); Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis |

Drug: BMS-986036 (PEG-FGF21) Other: Placebo |

Phase II |

| Recruiting | Effect of Weekly High-dose Vitamin D3 Supplementation on the Association Between Circulatory FGF-23 and A1c Levels in People With Vitamin D Deficiency: A Randomized Controlled 10-weeks Follow-up Trial. | Applied Science Private University | Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2 Kidney Diseases | Dietary Supplement: Soft gelatin capsules each contains 50,000 IU VD3 (cholecalciferol) equivalents to 1.25 mg. | NA |

| Unknown | Safety Study of Topical Human FGF-1 for Wound Healing | Phage Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Diabetic Foot Ulcers | Drug: FGF-1141 | Phase I |

| Completed | FGF-23 and Endothelial Dysfunction in Diabetic Proteinuric Patients | Gulhane School of Medicine | Proteinuria; Diabetic Nephropathy; Chronic Kidney Disease |

Drug: Ramipril | Phase IV |

Note: Sources: www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

The Relationship Between Fibroblast Growth Factor and Diabetic Nephropathy

FGFs maintain the general dynamic homeostasis by regulating autocrine, paracrine and endocrine systems that participate in numerous processes that mediate the development of diabetes and related complications including angiogenesis, oxidative stress, immune inflammation, tissue repair and islet resistance.53–57 Consequently, FGFs are potential therapeutic targets for diabetes and related complications. Overall, the current consensus is that FGF participates in DN development.

FGF1

Initially classified under mitogens of brain and pituitary fibroblasts, FGF1 is released by damaged cells or via endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi independent exocytosis pathways. FGF1 is widely expressed in developing and mature tissues and regulates numerous biological activities.58 It can interact with heparin or heparan sulfate proteoglycan, bind to four tyrosine kinase FGF receptors, and participate in the regulation of various physiological processes such as development, angiogenesis, wound healing, lipogenesis and neurogenesis. FGF performs these functions by regulating multiple signaling pathways including RAS/Raf/MEK/ERK, JNK and p38 MAPK, STAT3 and NF-κB pathways.59

FGF1 are potential therapeutic targets for diabetes.60 For instance, Jonker et al found that a high-fat diet induces over-expression of FGF1.61 Contrarily, FGF1 gene knockout results in severe diabetes in mice, accompanied by abnormal swelling after feeding on following high-fat diet. These findings demonstrate that FGF1 improves lipid metabolism and suppresses the development of diabetes. In Jonker’s experiments, luciferase activity and chip sequence analyses further confirmed that increase in FGF1 expression following a high-fat diet intake is regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR γ) via the PPAR response element in the promoter region of FGF1 gene. PPAR γ maintains metabolic homeostasis by selectively binding FGF1 on adipocytes. In a related study, it was found that prolonged intake of recombinant FGF1 (rFGF1) leads to persistent hypoglycemia, systemic insulin sensitivity and under secretion of several inflammatory cytokines including eosinophil chemokines, inflammatory proteins and interleukin (IL). FGFR1-mediated signal transduction is necessary for hypoglycemic and insulin-sensitization by FGF1. In addition, the hypoglycemic effect of rFGF1 is insulin dose-dependent and does not lead to hypoglycemia. Compared with current insulin sensitization therapies, continuous hypoglycemic and insulin sensitization using rFGF1 does not result in serious adverse side effects such as body weight gain, liver steatosis and loss of bone mass.62 In a related research, FGF1 treatment was found to significantly improve secretion of inflammatory cytokines induced by obesity and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), modulate inflammation and improve induced pancreatic islet resistance. FGF-1 performs these functions by weakening JNK signal transduction, inhibiting TNF-α secretion and regulating phosphorylation of C-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). These processes are mediated by transforming growth factor β-activated kinase 1(TAK1)-TAK1 binding protein 1(TAB1).63 However, it is not clear whether these pathways are the primary mechanisms with which FGF1 ameliorates DN.

FGF1 potentially protects against renal dysfunction. Bioinformatics analyses have revealed that FGF1is under-expressed in the kidney of DN patients.64 Aqueous extract of Phyllanthus niruri leaves modulates the expression of FGF1 in the renal tubules and FGF in the kidney of DN patients.65 FGF1 is a therapeutic candidate for DN. FGF1 reduces urinary albumin excretion, glomerular sclerosis, expression of proteins related to fibrosis in renal tissues, expression of high glucose-induced podocyte pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-ɑ (TNF-ɑ) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) as well as glomerulonephritis in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. It is thought FGF1 relieves renal inflammation in DN patients by inhibiting JNK activity and hyperglycemia-induced NF-κB expression.66

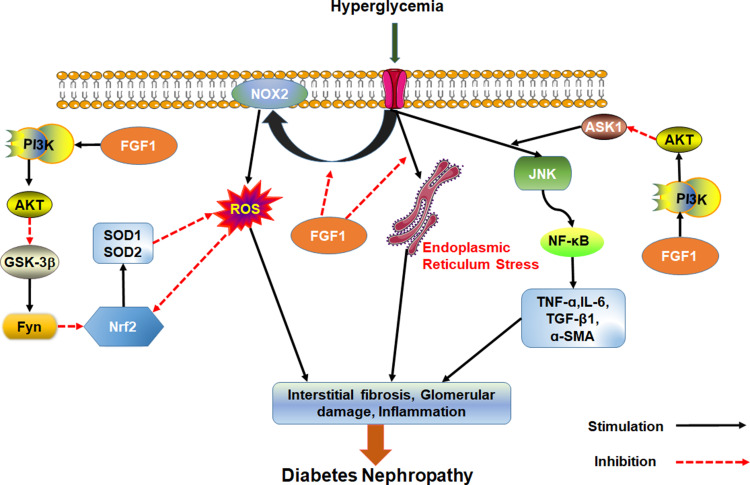

Wang et al found that FGF1 knockdown inhibits inflammation and oxidative stress during DN development.67 These findings suggest that FGF1 knockdown inhibits oxidative stress and inflammatory response by over activating GSK-3β/Nrf2 signaling pathway but inhibiting ASK1/JNK1 signaling pathway, both of which are regulated by PI3K/AKT signaling. Possibly, AKT is an upstream regulator of oxidative stress and inflammation in chronic nephropathy. Furthermore, treatment with FGF1 can inhibit over-expression of NADPH oxidase (NOX)2 in DN, reduce the production of peroxide and reverse down-regulated expression of signal nuclear factor E2 related factor 2 (Nrf2) following anti-inflammatory and oxidative damage in diabetics. Overall, these processes alleviate diabetes induced oxidative stress in kidneys.68

FGF1 is an effective treatment of kidney injury. It can prevent renal hypertrophy and DN without causing adverse side effects such as loss of body weight and hyper/hypoglycemia. FGF1 also prevents DNA damage, cellular stress, production of vasoactive factors and angiotensinogen and dysregulated expression of endothelial NO after diabetes. Even if FGF1 does not inhibit the expression of TGF-β1, it prevents renal fibrosis by inhibiting production of fibronectins.69 To sum up, FGF1 can effectively prevent kidney injury, inhibit renal inflammation and oxidative stress, and prevent development of DN independent of hypoglycemic activity (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of FGF1 on DN. FGF1 can ameliorate cell stress, inflammation, fibrosis and kidney injury.

FGF2

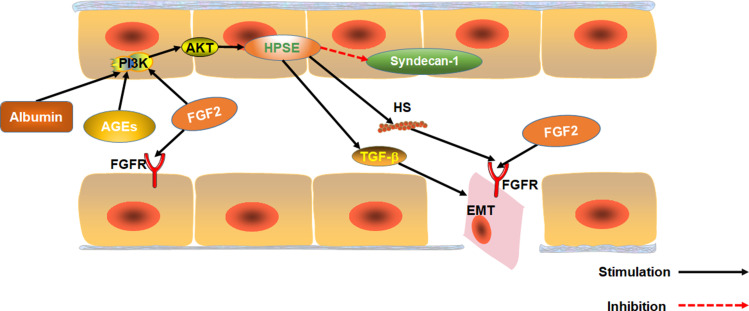

FGF2 is over-expressed in the serum of patients with any DN.70 FGF2 is a growth factor that regulates angiogenesis and participates in hyperglycemia-induced vascular dysfunction in diabetics.71 Substantial evidence suggests that FGF2 participates in the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) of renal tubular epithelial cells and renal fibers. EMT is one of the key events in the process of renal interstitial fibrosis.72,73 Over-expression of FGF2 stimulates proliferation of fibroblasts, and to some extent, extracellular matrix production, which promotes renal tubulointerstitial damages in diabetes.74 FGF2 can also induce EMT by stably activating the PI3K/AKT pathway. Heparanase-1 (HPSE) mediates FGF2-induced EMT. HPSE is also a precursor for stable activation of PI3K/AKT pathway by FGF2.75 Moreover, albuminuria as well as AGE and FGF2 activation via the PI3K/AKT pathway upregulates HPSE expression.76,77 HPSE is essential for the signaling of TGF-β1. HPSE-deficiency inhibits FGF2-mediated expression of TGF-β1 in renal tubular cells. Also, HPSE down-regulates expression of transmembrane HS proteoglycan syndecan-1, which regulates FGF2 signaling.78 Therefore, HPSE and FGF2 are potential targets for DN treatment. Inhibiting HPSE from blocking EMT has been used for the treatment of chronic kidney diseases.77 Also, FGF2 can exacerbate acute and chronic podocyte injury, which worsens glomerular damage.79

Interestingly, however, research shows that FGF2 can ameliorate both CKD and DN.49,80 Expression of Heparan sulfate proteoglycan glypican-5 (GCP5) is thought to predispose diabetic patients to DN. Meanwhile, over expression of GCP5, FGFR3 and FGFR4 under high glucose increases the accumulation of glomerular FGF2, leading to fibrosis.81 Although FGF2 is present in glomerular capillaries of normal mice, it is under-expressed in glomerular epithelial cells.82 Therefore, we speculate low-dose FGF2 can treat DN because it does not accumulate in the glomeruli. However, over-expression of FGF2 in DN patients accumulates FGF2 in the glomeruli, aggravating renal fibrosis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The effect of FGF2 on EMT in renal tubular epithelial cells. The effect of Albuminuria, AGEs and FGF2 on PI3K/AKT pathway mediated expression of HPSE. HPSE can hydrolyze HSPG to generate HS fragments and inhibit the overexpression of multiligand proteoglycan-1, essential for FGF2 activation of. In addition, HPSE regulate the expression and activity of TGF-β.

FGF21

FGF21 is a member of the endocrine gene family mainly expressed in the liver, which is secreted by hepatocytes in response to a variety of stresses. Serum circulating fibroblast growth factor 21 levels in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) increase from the early stage of disease progression, and the progressive increase of FGF21 may be a response to survival stress. Although the increase of FGF21 increases the cardiovascular risk, it is necessary for the survival of CKD mice.54,83,84 Furthermore, the analysis results of clinical samples of diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease showed that when glomerular filtration rate was high, serum FGF21 levels increased with proteinuria but were relatively low in the kidneys. The elevated levels of FGF21 in patients with DN may be due to the increased secretion of the body for protection purposes under the stimulation of stress responses such as inflammation and oxidative stress. However, with the development of DN, renal function is decreased, leading to the accumulation of FGF21 in the body.85–87 Therefore, the circulating FGF21 levels are considered as a potential biomarker for predicting the development of DN.86,88–90 Administration of FGF21 can reduce nephritis, oxidative stress, fibrosis and lipid accumulation caused by diabetes, which reduce kidney cell apoptosis and protect the kidney.91–94

FGF21 ameliorates DN by improving insulin resistance.95,96 Prostaglandin (PGE1) protects renal tissues against hyperglycemia. For instance, PGE1 inhibits autophagy-induced mitochondrial stress or dysfunction, up-regulates FGF21 expression induced by ATF4, improves renal tubular insulin resistance and prevents DN development.97,98

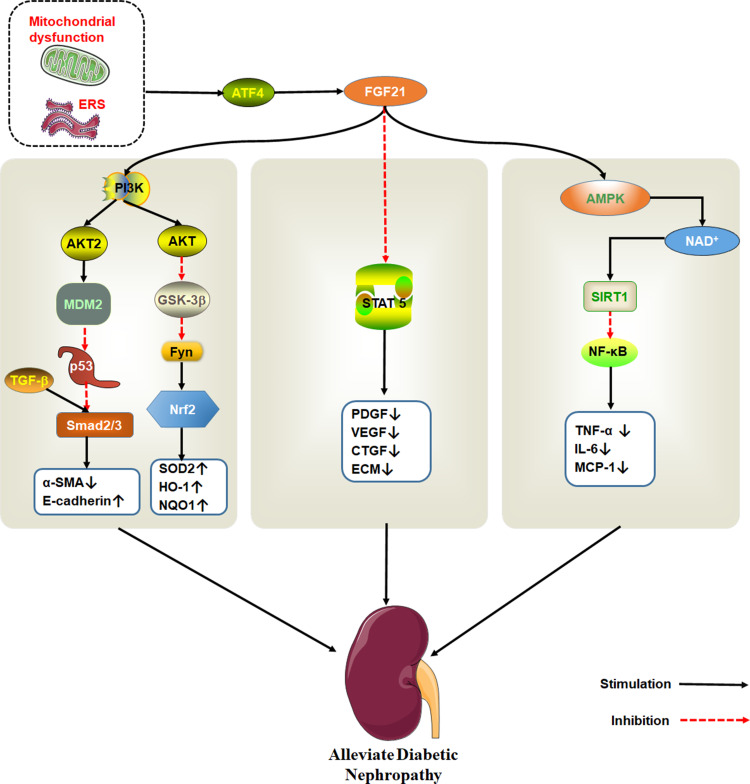

Regarding DN, the anti-fibrous mechanism of FGF21 is very complex. It is thought that FGF21 exerts its anti-fibrosis effect in DN by inhibiting signal transduction and transcriptional activator (STAT) 5 signaling pathway.99 However, in a separate study, mice models revealed that FGF21 can effectively modulate nephropathy and renal inflammation in type 1 diabetics with DN via the renal adenylate activated protein kinase (AMPK)-Sirtuin1 (SIRT1) pathway.93,100 AMPK activation inhibits expression of NF-κB. On the other hand, FGF21 inhibits the activation of NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasomes. Meanwhile, NOD-like receptor 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes are related to DN pathogenesis.101,102 FGF21also inhibits the activity of tumor suppressor protein p53 by activating PI3K/AKT/MDM2 signaling pathway and by inhibiting Smad2/3 nuclear transport. The protein also protects against kidney damage.103

Fenofibrate is a common lipid-lowering drug that prevents renal dysfunction and pathological changes caused by diabetes, renal fibrosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis by activating PPAR α. Fenofibrate protects kidney damage by up-regulating the expression of FGF21, which activates the PI3K/Akt2/GSK-3β/Fyn-mediated Nrf2 and AMPK pathways104,105 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The therapeutic effect of FGF21 on DN. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates ATF4, which induce FGF21 expression. FGF21 protects kidney damage by activating multiple signaling pathways. PI3K/AKT pathway is shown to the left, STAT5 pathway in the middle and AMPK/SIRT1 on the right.

FGF23

FGF23 is a protein secreted by bone cells and is a crucial hormone for regulating phosphate homeostasis. The primary targets of FGF23 are the kidney and parathyroid. It functions by binding FGFR using α-Klotho protein as a cofactor.106 Both fundamental and clinical studies with CKD indicate that circulating levels of serum FGF23 begin to increase early in CKD progression. Up-regulation of FGF23 is a risk biomarker of progressive diabetic nephropathy. Excessive FGF23 is associated with rapid progression of CKD and increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, making it a prognostic marker of CKD.107–111 Nevertheless, in order to maintain phosphate homeostasis, the FGF23-aKlotho endocrine axis is needed to reduce phosphate reabsorption and increase phosphate excretion. However, this compensatory response may accelerate the progression of CKD. Phosphate excretion per nephron was positively correlated with the severity of the renal tubular injury and interstitial fibrosis. The increase in phosphate excretion per nephron increases the phosphate concentration in the renal tubular fluid. However, due to the decrease in renal function, the ability of the kidney to excrete urine phosphate is reduced, resulting in the accumulation of phosphate in the renal tubules, leading to tubular injury and interstitial fibrosis. Therefore, an increase in FGF23 is also considered a risk for renal tubular injury and interstitial fibrosis.112,113 Compared with patients with CKD without diabetes, patients with diabetic kidney disease have higher levels of serum phosphate, PTH, and FGF23, and the disorder of mineral metabolism is more serious.114,115 In recent years, elevated FGF23 is not only considered as a predictor of cardiovascular risk and mortality in CKD and ESRD. However, it may also be a potential biomarker for early diagnosis of renal dysfunction and prediction of chronic complications and progression of DN.85,116,117

Numerous studies show that high FGF23 levels induces inflammation in DN patients.118–120 The competitive antagonist of FGF23 (FGF23C-tail) ameliorates DN by reducing inflammation and fibrosis.121 Elsewhere, the renal impairment of FGF23 was reported to be associated with endothelial dysfunction. High FGF-23 levels reduce the risk of early development of kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the absence of other intervening risk factors.122 It is thought that FGF23 induces inflammation by disrupting phosphate metabolism. Inhibition of FGF-23 relieves DN by increasing peripheral insulin sensitivity and enhancing subcutaneous glucose tolerance.123

FGF23 causes kidney endothelial dysfunction, a significant risk factor for renal disease and an established regulator of local angiotensin II in the kidney by inducing phosphate metabolism and inhibiting nitric oxide (NO) production.124 Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors protect against renal damage in DN patients partly by modulating levels of plasma FGF23 and secretion of FGF23 in the kidney while up-regulating Klotho expression.125,126 Hesperidin modulates inflammation, hyperglycemia and promotes anti-oxidation. Also, rat models revealed that Hesperidin down-regulate FGF23 levels in diabetics and up-regulate that of α-Klotho protein, thereby ameliorating DN. Even so, additional studies are needed to explore the relationship between blood.127

Others FGFs

FGF11 participates in renal injury in DN patients by promoting proliferation and fibrosis of mesangial cells. Even though overwhelming evidence shows that circRNAs-miRNA-mRNA axis is central to DN development, it has also been linked with FGF.128,129 Circular RNA_0080425 is over-expressed in DN patients, and activates FGF11 expression. On the other hand, inhibition of FGF11 expression using miR-24-3p modulates proliferation and fibrosis of mesangial cells. However, impairing miR-24-3p function blocks the inhibition of FGF11 by small interference annular RNA_0080425, suggesting that competitive binding of cyclic RNA_0080425 to miR-24-3p induces FGF11 release. Even though this inhibits miR-24-3p function, it exacerbates DN.130

In the latest research, Md Dom et al reported that angiopoietin-1 (ANGPT1), FGF 20, tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 12 (TNFSF12) are related to protecting diabetic nephropathy from progressing to ESRD. The lower the concentration of these proteins, the higher the risk of progression to ESRD. Meanwhile, FGF20 can be used as biomarkers to predict the risk of DN progression to ESRD and delay or prevent ESRD.131 FGF20 is selectively expressed in the brain and is almost absent in healthy peripheral tissues. There are few studies on it in the kidney, but some studies have found that FGF20 can maintain the stem cell characteristics of embryonic nephron progenitor cells and maintain normal kidney development.132,133 The protective effect of FGF20 on the progression of DN to ESRD needs further investigation.

Interaction Between FGF and Other Signal Pathways in DN

During DN development, FGF regulates several inter-related signaling pathways such as STAT, AMPK and PI3K/AKT, among others. These findings pathways that the regulatory role of FGF in DN are not well understood.

FGF and the PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway

Numerous studies have shown that FGFs perform their functions in DN via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which also regulates inflammation, oxidative stress, and EMT.134,135 As such, FGF alleviates inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis by activating the PI3K/Akt signal transduction pathway.136,137 PI3K is a heterodimer composed of p85, a regulatory subunit and p110, a catalytic subunit. PI3K is ubiquitous in cytoplasm. Phosphatidylinositol kinase and serine/threonine protein kinase play a pivotal role in (PI3K/Akt) pathway.138 Akt is a protein kinase encoded by a homolog of intracellular retrovirus. Because of its high homology with protein kinase A (PKA) and PKC, Akt is also known as protein kinase B (PKB). Tyrosine kinase activates PI3K to produce PIP3 in the plasma membrane. PIP3 then interacts with Akt PH domain, which aggregates Akt on the membrane. Thereafter, 3-phosphate inositol-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1) phosphorylates and activates Akt threonine (Thr) 308.

AKT is a downstream target of PI3K and participates in sundry cellular processes such as proliferation, migration and apoptosis of cells, glucose metabolism and transcription. Activated Akt inactivates GSK-3 β by phosphorylating its serine (Ser) 9 residue, which inactivates Fyn kinase. This relieves ubiquitin-mediated inhibited Nrf2 expression while also strengthening cellular defense mechanism.139,140 Activated AKT also inhibits ASK1 activity, preventing glomerulosclerosis and glomerulonephritis progression, thus improving renal function.141,142 (Akt) is thought to perform its function by inhibiting p38/JNK signaling. ASK1 can promote inflammatory response and cell death by activating p38/JNK signaling pathway. Inhibition of ASKI activation can suppress renal inflammation and fibrosis, reduce renal injury.143

PI3K/AKT regulates EMT process. Hyperglycemia-induced ROS disrupts the TGF-β1/Smad/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, in which the downstream mTOR signal promotes EMT of renal tubules, aggravating diabetic kidney injury.144,145 Whether renal fibrosis caused by FGF2 activating PI3K/AKT in DN patients is related to mTOR remains to be validated. However, PI3K/AKT activation by FGF21 inhibits TGF-β1/smad2/3 activation and reduces fibrosis in DN patients.103 The TGF-β1/Smad pathway is closely related to renal fibrosis. Meanwhile, p53 mediates functions of TGF-β1/Smad pathway.146,147 Activated AKT phosphorylates MDM2, inhibits p53 activity, and disrupts renal protective effect of TGF-β1/Smad2/3.103,148 Previously, we have proposed that FGF21 can protect kidney by activating AKT2. However, the activation of PI3K/AKT by FGF2 aggravates the mechanism of renal fibrosis, a which seems to be related to the activation of AKT3.The PI3K/AKT3 also regulates cell proliferation and fibrosis. Even so, the described relationships need further investigation.105,149

FGF and the AMPK Pathway

Adenosine 5´-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a highly conserved serine/threonine kinase that regulates glucose and lipid metabolism. Inhibition of AMPK activity leads to insulin resistance.150 SIRT1 is an NAD+-dependent lysine deacetylase, shown to protect kidney damage in DN patients.151 SIRT1 in proximal tubules disrupts functioning of podocytes by increasing the levels of nicotinamide mononucleotides around the glomerulus, thus preventing albuminuria in diabetics.152,153 SIRT1 is the downstream effector of AMPK. Activated AMPK activates SIRT1 by up-regulate NAD+ expression. SIRT1 has something in common with AMPK in metabolism and cell survival.154 SIRT1 regulates inflammatory responses by deacetylating target molecule, which downregulates transcription of inflammation-related genes by inhibiting the activity of transcription factor NF-κB.155 Therefore, over-whelming evidence shows that AMPK/SIRT1 activation reduces renal inflammation, oxidative stress and podocyte apoptosis in DN patients, thus protecting against kidney damages.156,157

AMPK and SIRT1 are downstream kinases for FGF21. Activation of AMPK stimulates glucose metabolism and oxidation of fatty acids in patients with diabetes mellitus. AMPK activation protects against kidney damage by modulating NOX4/TGF-β1 signaling in DN, which reduces oxidative stress and fibrosis.150,157,158 FGF1 also activates AMPK by binding FGFR4, further activating the Nrf2-mediated anti-oxidation but inhibiting lipogenesis. These processes improve liver lipid metabolism in patients with diabetes while also modulating liver oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis.159 The therapeutic potential of these interrelationships for DN treatment remains to be studied.

FGF and STAT5 Signaling Pathway

STAT5 is a transcription factor that participates in signal transduction pathways of minor hormones and cytokines. STAT5 has been implicated in the pathological process of glomerular mesangial cell injury in DN.160 Inhibition of STAT5 using FGF21 results in a negative feedback.161 FGF21 can modulate the expression of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF). FGF21 performs its function by inhibiting the STAT5 signaling pathway, which improves hyperglycemia-induced mesangial cell fibrosis, thus reducing the expression of extracellular matrix (ECM).99 STAT5 phosphorylation is up-regulated in patients with DN, thus alleviating renal interstitial fibrosis by inhibiting the STAT5 pathway.162,163 Besides, mice models show that STAT5 participates in glucose and lipid metabolism, promotes glycogen xenogenesis and reduces insulin sensitivity.164

Conclusion and Future Direction

Overwhelming evidence has demonstrated the close relationship between FGF and DN. Understanding the intricate pathogenesis and FGF changes during DN opens a new frontier into prevention and treatment of DN. FGF is a potential therapeutic target for DN management. DN increases the expression of serum FGF21 and FGF23 levels, the two most important metabolism-related FGF family members, which positively correlates with gradual renal damage. As such, FGF21 and FGF23 are reliable biomarkers for predicting progression of renal disease, especially in the early stage of DN.

The pathogenesis of DN is a complex process involving numerous molecules. DN development is also regulated by multiple factors. FGFs manifold participates in many ways in the occurrence and development of DN. At present, drugs such as recombinant human fibroblast growth factor 21 (rhFGF21) and mutant modified human acidic fibroblast growth factor targeting FGF have been shown to be effective against DN. FGF drugs can effectively regulate several DN processes such as inflammation, glucose and lipid metabolism, oxidative stress and kidney injury. However, regarding limitations, the pharmacokinetics of FGF is lacking, it has a very short half-life and it needs frequent administration. As such, the development of FGF drugs for DN can follow two aspects: 1) Construction of recombinant FGF with better pharmacokinetic characteristics, longer of half-life, plasma stability, and clinical efficacy. 2) Target regulation of activation and secretion of FGF. Even though non-coding RNA can regulate expression and activity of FGF, whether they can relieve DN remains unclear. Thus, future research can explore this perspective. Proper administration of FGFs can enhance their efficacy. Centrally administered FGF1 can enhance the hypoglycemic effect of FGF1 and ensure sustained relief from diabetes. However, whether the route of administration can enhance the efficacy of other FGFs remains to be validated. Additionally, the role and mechanism of FGF in DN are not very clear. Therefore, further studies should explore the mechanisms to reveal therapeutic avenues for the prevention and treatment of DN.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81960741, 82160770, 81560712), the Guizhou Provincial Natural Science Foundation (QKH-J-2020-1Z070), the Special Funding for Postdoctoral Research Projects in Chongqing (Xm2019061), Guizhou Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Funding (QZYY2017-080).

Abbreviations

DN, diabetic nephropathy; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; FGFRs, fibroblast growth factor receptors; HSPG, heparin sulfate proteoglycan; PTK, tyrosine protein kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; ECM, extracellular matrix; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β1; AGEs, advanced glycation end products; RAGE, AGE receptors; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ERK, extracellular regulated protein kinases; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-B; PPAR γ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; STAT, signal transducers and activators of transcription; rFGF1, long-term administration of recombinant FGF1; IL, interleukin; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; JNK, C-Jun N-terminal kinase; TAK1, transforming growth factor β-activated kinase 1; TAB1, TAK1 binding protein 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor E2 related factor 2; NOX, NADPH oxidase; EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition; HPSE, heparanase-1; GCP5, glypican-5; CKD, chronic kidney disease; PGE1, prostaglandin; AMPK, the adenosine 5´-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor 3; MDM2, mouse double minute 2; PKB, protein kinase B; PDK1,3, phosphate inositol-dependent protein kinase 1; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Zhang H, Nie X, Shi X, et al. Regulatory mechanisms of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in diabetic cutaneous ulcers. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1114. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gnudi L, Coward RJM, Long DA. Diabetic nephropathy: perspective on novel molecular mechanisms. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2016;27(11):820–830. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selby NM, Taal MW. An updated overview of diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis, prognosis, treatment goals and latest guidelines. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(Suppl 1):3–15. doi: 10.1111/dom.14007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giorda CB, Carna P, Salomone M, et al. Ten-year comparative analysis of incidence, prognosis, and associated factors for dialysis and renal transplantation in type 1 and type 2 diabetes versus non-diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2018;55(7):733–740. doi: 10.1007/s00592-018-1142-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhattacharjee N, Barma S, Konwar N, Dewanjee S, Manna P. Mechanistic insight of diabetic nephropathy and its pharmacotherapeutic targets: an update. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;791:8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han Q, Zhu H, Chen X, Liu Z. Non-genetic mechanisms of diabetic nephropathy. Front Med. 2017;11(3):319–332. doi: 10.1007/s11684-017-0569-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umanath K, Lewis JB. Update on diabetic nephropathy: core curriculum 2018. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(6):884–895. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L, Long J, Jiang W, et al. Trends in chronic kidney disease in China. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):905–906. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1602469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui Q, Jin Z, Li X, Liu C, Wang X. FGF family: from drug development to clinical application. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(7):1875. doi: 10.3390/ijms19071875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Yeung DC, Karpisek M, et al. Serum FGF21 levels are increased in obesity and are independently associated with the metabolic syndrome in humans. Diabetes. 2008;57(5):1246–1253. doi: 10.2337/db07-1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Wu D, Tian Y. Fibroblast growth factor 19 protects the heart from oxidative stress-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy via activation of AMPK/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;502(1):62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang N, Xu TY, Zhang X, et al. Improving hyperglycemic effect of FGF-21 is associated with alleviating inflammatory state in diabetes. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;56:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.01.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho JM, Yang EH, Quan W, Nam EH, Cheon HG. Discovery of a novel fibroblast activation protein (FAP) inhibitor, BR103354, with anti-diabetic and anti-steatotic effects. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):21280. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77978-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itoh N, Ornitz DM. Fibroblast growth factors: from molecular evolution to roles in development, metabolism and disease. J Biochem. 2010;149(2):121–130. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvq121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beenken A, Mohammadi M. The FGF family: biology, pathophysiology and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(3):235–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belov AA, Mohammadi M. Molecular mechanisms of fibroblast growth factor signaling in physiology and pathology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(6):a015958. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a015958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ornitz DM, Itoh N. The fibroblast growth factor signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2015;4(3):215–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dailey L, Ambrosetti D, Mansukhani A, Basilico C. Mechanisms underlying differential responses to FGF signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16(2):233–247. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.House SL, Branch K, Newman G, Doetschman T, Schultz Jel J. Cardioprotection induced by cardiac-specific overexpression of fibroblast growth factor-2 is mediated by the MAPK cascade. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(5):H2167–H2175. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00392.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun S, Auf Dem Keller U, Steiling H, Werner S, Brockes JP, Martin P. Fibroblast growth factors in epithelial repair and cytoprotection. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1445):753–757. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupte VV, Ramasamy SK, Reddy R, et al. Overexpression of fibroblast growth factor-10 during both inflammatory and fibrotic phases attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(5):424–436. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200811-1794OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Ibrahimi OA, Olsen SK, Umemori H, Mohammadi M, Ornitz DM. Receptor specificity of the fibroblast growth factor family. The complete mammalian FGF family. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(23):15694–15700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601252200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eswarakumar VP, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16(2):139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2010;141(7):1117–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlessinger J, Plotnikov AN, Ibrahimi OA, et al. Crystal structure of a ternary FGF-FGFR-heparin complex reveals a dual role for heparin in FGFR binding and dimerization. Mol Cell. 2000;6(3):743–750. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00073-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlessinger J. Signal transduction. Autoinhibition control. Science. 2003;300(5620):750–752. doi: 10.1126/science.1082024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Potthoff MJ, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. Endocrine fibroblast growth factors 15/19 and 21: from feast to famine. Genes Dev. 2012;26(4):312–324. doi: 10.1101/gad.184788.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith ER, McMahon LP, Holt SG. Fibroblast growth factor 23. Ann Clin Biochem. 2013;51(2):203–227. doi: 10.1177/0004563213510708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degirolamo C, Sabba C, Moschetta A. Therapeutic potential of the endocrine fibroblast growth factors FGF19, FGF21 and FGF23. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(1):51–69. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuro-o M. The Klotho proteins in health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15(1):27–44. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0078-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):137–188. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magee C, Grieve DJ, Watson CJ, Brazil DP. Diabetic nephropathy: a tangled web to unweave. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2017;31(5–6):579–592. doi: 10.1007/s10557-017-6755-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Wen Z, Han L, et al. Research progress on the pathological mechanisms of podocytes in diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Res. 2020;2020:7504798. doi: 10.1155/2020/7504798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sifuentes-Franco S, Padilla-Tejeda DE, Carrillo-Ibarra S, Miranda-Díaz AG. Oxidative stress, apoptosis, and mitochondrial function in diabetic nephropathy. Int J Endocrinol. 2018;2018:1875870. doi: 10.1155/2018/1875870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang SCW, Yiu WH. Innate immunity in diabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(4):206–222. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0234-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang -T-T, Chen J-W. The role of chemokines and chemokine receptors in diabetic nephropathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3172. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wada J, Makino H. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Clin Sci (Lond). 2013;124(3):139–152. doi: 10.1042/CS20120198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luis-Rodriguez D, Martinez-Castelao A, Gorriz JL, De-alvaro F, Navarro-Gonzalez JF. Pathophysiological role and therapeutic implications of inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. World J Diabetes. 2012;3(1):7–18. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v3.i1.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rivero A, Mora C, Muros M, Garcia J, Herrera H, Navarro-Gonzalez JF. Pathogenic perspectives for the role of inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Sci (Lond). 2009;116(6):479–492. doi: 10.1042/CS20080394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Navarro-Gonzalez JF, Mora-Fernandez C, Muros de Fuentes M, Garcia-Perez J. Inflammatory molecules and pathways in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7(6):327–340. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giacco F, Brownlee M, Schmidt AM. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res. 2010;107(9):1058–1070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tavafi M. Diabetic nephropathy and antioxidants. J Nephropathol. 2013;2(1):20–27. doi: 10.5812/nephropathol.9093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forbes JM, Thorburn DR. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(5):291–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stumvoll M, Goldstein BJ, van Haeften TW. Type 2 diabetes: principles of pathogenesis and therapy. Lancet. 2005;365(9467):1333–1346. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61032-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orchard TJ, Chang Y-F, Ferrell RE, Petro N, Ellis DE. Nephropathy in type 1 diabetes: a manifestation of insulin resistance and multiple genetic susceptibilities?: further evidence from the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complication Study. Kidney Int. 2002;62(3):963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dib SA. [Insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in type 1 diabetes mellitus]. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2006;50(2):250–263. Portugese. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27302006000200011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noh H, King GL. The role of protein kinase C activation in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl. 2007;72(106):S49–S53. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung SS, Ho EC, Lam KS, Chung SK. Contribution of polyol pathway to diabetes-induced oxidative stress. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(8 Suppl 3):S233–236. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000077408.15865.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanajou D, Ghorbani Haghjo A, Argani H, Aslani S. AGE-RAGE axis blockade in diabetic nephropathy: current status and future directions. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;833:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kang JS, Lee SJ, Lee JH, et al. Angiotensin II-mediated MYH9 downregulation causes structural and functional podocyte injury in diabetic kidney disease. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7679. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44194-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kanwar YS, Sun L, Xie P, Liu FY, Chen S. A glimpse of various pathogenetic mechanisms of diabetic nephropathy. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:395–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kato M, Natarajan R. Epigenetics and epigenomics in diabetic kidney disease and metabolic memory. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15(6):327–345. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0135-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Callaghan MJ, Chang EI, Seiser N, et al. Pulsed electromagnetic fields accelerate normal and diabetic wound healing by increasing endogenous FGF-2 release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(1):130–141. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000293761.27219.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.So WY, Leung PS. Fibroblast growth factor 21 as an emerging therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med Res Rev. 2016;36(4):672–704. doi: 10.1002/med.21390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang H, Feng A, Lin S, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-21 prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy via AMPK-mediated antioxidation and lipid-lowering effects in the heart. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(2):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Donate-Correa J, Martín-Núñez E, Ferri C, et al. FGF23 and klotho levels are independently associated with diabetic foot syndrome in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Med. 2019;8(4):448. doi: 10.3390/jcm8040448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katoh M. Therapeutics targeting FGF signaling network in human diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37(12):1081–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Itoh N, Ornitz DM. Evolution of the Fgf and Fgfr gene families. Trends Genet. 2004;20(11):563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raju R, Palapetta SM, Sandhya VK, et al. A network map of FGF-1/FGFR signaling system. J Signal Transduct. 2014;2014:962962. doi: 10.1155/2014/962962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gasser E, Moutos CP, Downes M, Evans RM. FGF1 - a new weapon to control type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(10):599–609. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jonker JW, Suh JM, Atkins AR, et al. A PPARγ–FGF1 axis is required for adaptive adipose remodelling and metabolic homeostasis. Nature. 2012;485(7398):391–394. doi: 10.1038/nature10998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Suh JM, Jonker JW, Ahmadian M, et al. Endocrinization of FGF1 produces a neomorphic and potent insulin sensitizer. Nature. 2014;513(7518):436–439. doi: 10.1038/nature13540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fan L, Ding L, Lan J, Niu J, He Y, Song L. Fibroblast growth factor-1 improves insulin resistance via repression of JNK-mediated inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Z, Liu J, Wang W, Zhao Y, Yang D, Geng X. Investigation of hub genes involved in diabetic nephropathy using biological informatics methods. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(17):1087. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-5647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giribabu N, Karim K, Kilari EK, Salleh N. Phyllanthus niruri leaves aqueous extract improves kidney functions, ameliorates kidney oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis and apoptosis and enhances kidney cell proliferation in adult male rats with diabetes mellitus. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;205:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liang G, Song L, Chen Z, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 1 ameliorates diabetic nephropathy by an anti-inflammatory mechanism. Kidney Int. 2018;93(1):95–109. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang D, Jin M, Zhao X, et al. FGF1(ΔHBS) ameliorates chronic kidney disease via PI3K/AKT mediated suppression of oxidative stress and inflammation. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(6):464. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1696-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu Y, Li Y, Jiang T, et al. Reduction of cellular stress is essential for Fibroblast growth factor 1 treatment for diabetic nephropathy. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22(12):6294–6303. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pena AM, Chen S, Feng B, et al. Prevention of diabetic nephropathy by modified acidic fibroblast growth factor. Nephron. 2017;137(3):221–236. doi: 10.1159/000478745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Perlman AS, Chevalier JM, Wilkinson P, et al. Serum inflammatory and immune mediators are elevated in early stage diabetic nephropathy. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2015;45(3):256–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stephan CC, Chang KC, LeJeune W, et al. Role for heparin-binding growth factors in glucose-induced vascular dysfunction. Diabetes. 1998;47(11):1771–1778. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.11.1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Strutz F, Zeisberg M, Hemmerlein B, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor expression is increased in human renal fibrogenesis and may mediate autocrine fibroblast proliferation. Kidney Int. 2000;57(4):1521–1538. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00997.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Strutz F, Zeisberg M, Ziyadeh FN, et al. Role of basic fibroblast growth factor-2 in epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Kidney Int. 2002;61(5):1714–1728. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vasko R, Koziolek M, Ikehata M, et al. Role of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) in diabetic nephropathy and mechanisms of its induction by hyperglycemia in human renal fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296(6):F1452–F1463. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90352.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Masola V, Gambaro G, Tibaldi E, et al. Heparanase and syndecan-1 interplay orchestrates fibroblast growth factor-2-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in renal tubular cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(2):1478–1488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.279836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Masola V, Zaza G, Onisto M, Lupo A, Gambaro G. Impact of heparanase on renal fibrosis. J Transl Med. 2015;13:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Masola V, Zaza G, Gambaro G. Sulodexide and glycosaminoglycans in the progression of renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(Suppl 1):i74–i79. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Masola V, Zaza G, Secchi MF, Gambaro G, Lupo A, Onisto M. Heparanase is a key player in renal fibrosis by regulating TGF-β expression and activity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2014;1843(9):2122–2128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Floege J, Kriz W, Schulze M, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor augments podocyte injury and induces glomerulosclerosis in rats with experimental membranous nephropathy. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(6):2809–2819. doi: 10.1172/JCI118351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Villanueva S, Contreras F, Tapia A, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor reduces functional and structural damage in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306(4):F430–441. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00720.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Okamoto K, Honda K, Doi K, et al. Glypican-5 increases susceptibility to nephrotic damage in diabetic kidney. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(7):1889–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Floege J, Hudkins KL, Eitner F, et al. Localization of fibroblast growth factor-2 (basic FGF) and FGF receptor-1 in adult human kidney. Kidney Int. 1999;56(3):883–897. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00637.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Holland WL, Adams AC, Brozinick JT, et al. An FGF21-adiponectin-ceramide axis controls energy expenditure and insulin action in mice. Cell Metab. 2013;17(5):790–797. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nakano T, Shiizaki K, Miura Y, et al. Increased fibroblast growth factor-21 in chronic kidney disease is a trade-off between survival benefit and blood pressure dysregulation. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19247. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55643-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Looker HC, Colombo M, Hess S, et al. Biomarkers of rapid chronic kidney disease progression in type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2015;88(4):888–896. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yu W, Zhu H, Chen X, et al. Genetic variants flanking the FGF21 gene were associated with renal function in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2019;2019:9387358. doi: 10.1155/2019/9387358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lin Z, Zhou Z, Liu Y, et al. Circulating FGF21 levels are progressively increased from the early to end stages of chronic kidney diseases and are associated with renal function in Chinese. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee CH, Hui EY, Woo YC, et al. Circulating fibroblast growth factor 21 levels predict progressive kidney disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and normoalbuminuria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(4):1368–1375. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gamrot Z, Adamczyk P, Świętochowska E, Roszkowska-Bjanid D, Gamrot J, Szczepańska M. Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) in children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease. Physiol Res. 2020;69(3):451–460. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.934307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yamamoto S, Koyama D, Igarashi R, et al. Serum endocrine fibroblast growth factors as potential biomarkers for chronic kidney disease and various metabolic dysfunctions in aged patients. Intern Med. 2020;59(3):345–355. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.3597-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jian WX, Peng WH, Jin J, et al. Association between serum fibroblast growth factor 21 and diabetic nephropathy. Metabolism. 2012;61(6):853–859. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Esteghamati A, Khandan A, Momeni A, et al. Circulating levels of fibroblast growth factor 21 in early-stage diabetic kidney disease. Ir J Med Sci. 2017;186(3):785–794. doi: 10.1007/s11845-017-1554-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang C, Shao M, Yang H, et al. Attenuation of hyperlipidemia- and diabetes-induced early-stage apoptosis and late-stage renal dysfunction via administration of fibroblast growth factor-21 is associated with suppression of renal inflammation. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Angel GM, Paola VV, Froylan David MS, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 is associated with increased serum total antioxidant capacity and oxidized lipoproteins in humans with different stages of chronic kidney disease. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2021;12:20420188211001160. doi: 10.1177/20420188211001160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iglesias P, Selgas R, Romero S, Diez JJ. Biological role, clinical significance, and therapeutic possibilities of the recently discovered metabolic hormone fibroblastic growth factor 21. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167(3):301–309. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kim HW, Lee JE, Cha JJ, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 improves insulin resistance and ameliorates renal injury in db/db mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154(9):3366–3376. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim KH, Jeong YT, Oh H, et al. Autophagy deficiency leads to protection from obesity and insulin resistance by inducing Fgf21 as a mitokine. Nat Med. 2013;19(1):83–92. doi: 10.1038/nm.3014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wei W, An XR, Jin SJ, Li XX, Xu M. Inhibition of insulin resistance by PGE1 via autophagy-dependent FGF21 pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18427-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Li S, Guo X, Zhang T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 ameliorates high glucose-induced fibrogenesis in mesangial cells through inhibiting STAT5 signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;93:695–704. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.06.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Weng W, Ge T, Wang Y, et al. Therapeutic effects of fibroblast growth factor-21 on diabetic nephropathy and the possible mechanism in type 1 diabetes mellitus mice. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44(4):566–580. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2019.0089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu M-H. FGF-21 alleviates diabetes-associated vascular complications: inhibiting NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammation? Int J Cardiol. 2015;185:320–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen K, Zhang J, Zhang W, et al. ATP-P2X4 signaling mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation: a novel pathway of diabetic nephropathy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(5):932–943. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lin S, Yu L, Ni Y, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 attenuates diabetes-induced renal fibrosis by negatively regulating TGF-beta-p53-Smad2/3-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via activation of AKT. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44(1):158–172. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2018.0235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cheng Y, Zhang J, Guo W, et al. Up-regulation of Nrf2 is involved in FGF21-mediated fenofibrate protection against type 1 diabetic nephropathy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;93:94–109. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cheng Y, Zhang X, Ma F, et al. The role of Akt2 in the protective effect of fenofibrate against diabetic nephropathy. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(4):553–567. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.40643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Xie Y, Su N, Yang J, et al. FGF/FGFR signaling in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rodelo-Haad C, Santamaria R, Muñoz-Castañeda JR, Pendón-ruiz de Mier MV, Martin-Malo A, Rodriguez M. FGF23, biomarker or target? Toxins. 2019;11(3):175. doi: 10.3390/toxins11030175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Muñoz-Castañeda JR, Rodelo-Haad C, Pendon-ruiz de Mier MV, Martin-Malo A, Santamaria R, Rodriguez M. Klotho/FGF23 and Wnt signaling as important players in the comorbidities associated with chronic kidney disease. Toxins. 2020;12(3):185. doi: 10.3390/toxins12030185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Buchanan S, Combet E, Stenvinkel P, Shiels PG. Klotho, aging, and the failing kidney. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:560. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nowak N. Protective factors as biomarkers and targets for prevention and treatment of diabetic nephropathy: from current human evidence to future possibilities. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11(5):1085–1096. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bouma-de Krijger A, Bots ML, Vervloet MG, et al. Time-averaged level of fibroblast growth factor-23 and clinical events in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(1):88–97. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kuro OM. Klotho and endocrine fibroblast growth factors: markers of chronic kidney disease progression and cardiovascular complications? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34(1):15–21. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Komaba H, Fukagawa M. The role of FGF23 in CKD–with or without Klotho. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(8):484–490. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wahl P, Xie H, Scialla J, et al. Earlier onset and greater severity of disordered mineral metabolism in diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(5):994–1001. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Garland JS, Holden RM, Ross R, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with fibroblast growth factor-23 in stage 3–5 chronic kidney disease patients. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28(1):61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Agarwal R, Duffin KL, Laska DA, Voelker JR, Breyer MD, Mitchell PG. A prospective study of multiple protein biomarkers to predict progression in diabetic chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(12):2293–2302. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lu X, Hu MC. Klotho/FGF23 axis in chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease. Kidney Dis (Basel). 2017;3(1):15–23. doi: 10.1159/000452880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.David V, Martin A, Isakova T, et al. Inflammation and functional iron deficiency regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 production. Kidney Int. 2016;89(1):135–146. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Francis C, David V. Inflammation regulates fibroblast growth factor 23 production. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2016;25(4):325–332. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Czaya B, Faul C. FGF23 and inflammation-a vicious coalition in CKD. Kidney Int. 2019;96(4):813–815. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhang X, Guo K, Xia F, Zhao X, Huang Z, Niu J. FGF23(C-tail) improves diabetic nephropathy by attenuating renal fibrosis and inflammation. BMC Biotechnol. 2018;18(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s12896-018-0449-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Farias-Basulto A, Martinez-Ramirez HR, Gomez-Garcia EF, et al. Circulating levels of soluble klotho and fibroblast growth factor 23 in diabetic patients and its association with early nephropathy. Arch Med Res. 2018;49(7):451–455. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2019.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Titan SM, Zatz R, Graciolli FG, et al. FGF-23 as a predictor of renal outcome in diabetic nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(2):241–247. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04250510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Silswal N, Touchberry CD, Daniel DR, et al. FGF23 directly impairs endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation by increasing superoxide levels and reducing nitric oxide bioavailability. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;307(5):E426–E436. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00264.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yilmaz MI, Sonmez A, Saglam M, et al. Ramipril lowers plasma FGF-23 in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Am J Nephrol. 2014;40(3):208–214. doi: 10.1159/000366169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zanchi C, Locatelli M, Benigni A, et al. Renal expression of FGF23 in progressive renal disease of diabetes and the effect of ACE inhibitor. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Dokumacioglu E, Iskender H, Musmul A. Effect of hesperidin treatment on α-Klotho/FGF-23 pathway in rats with experimentally-induced diabetes. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:1206–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ge X, Xi L, Wang Q, et al. Circular RNA Circ_0000064 promotes the proliferation and fibrosis of mesangial cells via miR-143 in diabetic nephropathy. Gene. 2020;758:144952. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Mou X, Chenv JW, Zhou DY, et al. A novel identified circular RNA, circ_0000491, aggravates the extracellular matrix of diabetic nephropathy glomerular mesangial cells through suppressing miR‑101b by targeting TGFβRI. Mol Med Rep. 2020;22(5):3785–3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Liu H, Wang X, Wang ZY, Li L. Circ_0080425 inhibits cell proliferation and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy via sponging miR-24-3p and targeting fibroblast growth factor 11. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(5):4520–4529. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Md Dom ZI, Satake E, Skupien J, et al. Circulating proteins protect against renal decline and progression to end-stage renal disease in patients with diabetes. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:600. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abd2699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Huh SH, Ha L, Jang HS. Nephron progenitor maintenance is controlled through fibroblast growth factors and sprouty1 interaction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(11):2559–2572. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020040401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]