Abstract

Replicating or distilling information from psychological interventions reported in the scientific literature is hindered by inadequate reporting, despite the existence of various methodologies to guide study reporting and intervention development. This article provides an in-depth explanation of the scientific development process for a mental health intervention, and by doing so illustrates how intervention development methodologies can be used to improve development reporting standards of interventions. Intervention development was guided by the Intervention Mapping approach and the Theoretical Domains Framework. It relied on an extensive literature review, input from a multi-disciplinary group of stakeholders and the learnings from projects on similar psychological interventions. The developed programme, called the “Be Well Plan”, focuses on self-exploration to determine key motivators, resources and challenges to improve mental health outcomes. The programme contains an online assessment to build awareness about one’s mental health status. In combination with the exploration of different evidence-based mental health activities from various therapeutic backgrounds, the programme teaches individuals to create a personalised mental health and wellbeing plan. The use of best-practice intervention development frameworks and evidence-based behavioural change techniques aims to ensure optimal intervention impact, while reporting on the development process provides researchers and other stakeholders with an ability to scientifically interrogate and replicate similar psychological interventions.

Keywords: wellbeing, intervention research, intervention development, mental health promotion and prevention, mental health – state of emotional and social well-being

Introduction

Psychological interventions, being activities or groups of activities aimed to change behaviours, feelings and emotional states (Hodges et al., 2011), come in many shapes and sizes. A popular delivery method is in the form of programmes consisting of several interacting components and procedures, which per definition makes them “complex interventions” (Moore et al., 2015). This complexity is often lost in academic publications, as articles for instance are bound to word limits or have a primary focus on presenting outcome data as opposed to theoretical rationale and methodological insights (O’Cathain et al., 2019). Despite various welcome initiatives such the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) the intervention literature typically lacks in-depth descriptions of psychological interventions and the way they were created (Pino et al., 2012; Candy et al., 2018).

These reporting challenges are problematic for the scientific method as they make it difficult to replicate interventions, interpret which underlying intervention components are effective and draw robust conclusions about how these interventions have been developed (Chalmers and Glasziou, 2009; Hoffmann et al., 2017). More importantly, these challenges are avoidable as robust intervention development methodologies already exist that can be used to scientifically describe the components of complex behavioural and psychological interventions (Michie et al., 2011b; Eldredge et al., 2016; Garba and Gadanya, 2017). Scientific articles that purely describe the development of interventions using such methodologies can mainly be found in research on health behaviours, including smoking (van Agteren et al., 2018b), nutrition (Rios et al., 2019), physical activity (Boekhout et al., 2017), AIDS (Wolfers et al., 2007), and oral hygiene (Scheerman et al., 2018) to name a few. Despite their potential merit, the application of similar methodologies has yet to receive traction in psychological science.

Rigour in reporting standards is particularly important for new and emerging scientific areas in gaining scientific credibility and facilitating replication. The last decades have seen the introduction of a range of new psychological interventions, as well as the re-purposing of existing interventions, specifically aimed at promoting mental wellbeing, as opposed to addressing mental disorder per se (Slade, 2010). Improving outcomes of mental wellbeing is a protective factor against the onset of mental illness (Keyes et al., 2010; Iasiello et al., 2019), aids in disease recovery and chronic disease self-management and is associated with improved health service utilisation (Lamers et al., 2012; Slade et al., 2017). Above all, feeling mentally well is an important outcome in its own right, for individuals, families, communities, and society (Diener and Seligman, 2018; Diener et al., 2018). As a result, psychological interventions are increasingly in demand by health organisations, educational providers, workforces, and governments looking at wellbeing initiatives. Considering this interest, the individual and societal benefits of improving wellbeing, and fair criticism that have been drawn toward the lack of rigour in wellbeing research (Heintzelman and Kushlev, 2020), it is important to adequately describe the development of any interventions aimed at improving outcomes of mental wellbeing (Diener, 2003; Gable and Haidt, 2005; Kristjánsson, 2012).

The aim of the current article is to be a case study that firstly describes the application of a rigorous intervention development framework, the Intervention Mapping (IM) approach (Eldredge et al., 2016), to guide development of a theory- and evidence-based mental health intervention, designed to be used with both clinical and non-clinical populations. Secondly, as a result, it aims to act as a case study on the complexity that underpins scientific mental health interventions, and the detail that needs to be considered when aiming to replicate or modify them.

Materials and Methods

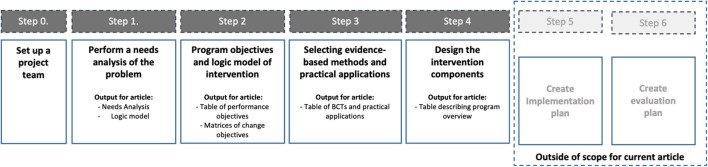

The IM approach guides intervention development in a series of six steps. This article follows the standard structure of the IM methodology. The methods below explain each of the four steps and how they were used for the development of the intervention in this article: the Be Well Plan. For a description of the methodology see Kok et al. (2016). Figure 1 visualises the methodology steps and its outputs at each stage, which are presented in the results below. The large bulk of programme development across the four steps was conducted by a small project team (JA, MI, KA, DF, and GF) who interacted with a larger multi-disciplinary project working group that among others included psychologists, counsellors, mental health researchers, and end-users, throughout the development life cycle. This group was crucial in informing and validating each of the IM steps, such as the exact objectives of the programme. The role for each of the members is described in more detail in Supplementary Appendix 1.

FIGURE 1.

Visualisation of the Intervention Mapping process and the outputs at each of the steps covered in the intervention development methodology.

Step 1: Determine the Problem That Needs to Be Solved by the Intervention via a Thorough Needs Analysis

The first step of IM involved performing a needs analysis related to the problem that the programme aims to solve. The needs analysis focuses on determining the problem that needs to be changed and subsequently defining the exact scope of the intervention. The needs analysis firstly draws on an extensive study of the scientific literature on mental health and wellbeing interventions. Secondly, it is underpinned by findings and data (published and unpublished) from previous wellbeing studies our research group conducted across population groups including in the general community, within workforces such as health professionals, with older adults, carers, and disadvantaged youths (Raymond et al., 2018, 2019; van Agteren et al., 2018a; Bartholomaeus et al., 2019). All data that was being used to underpin the needs analysis was subject to ethics approvals issued by the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee (SBREC), project numbers (PN) 7834, 7891, 7350, 7358, 7221, 7218, and 8579.

The IM framework uses the PRECEDE-PROCEED model (Gielen et al., 2008) to summarise and structure the results of the needs analysis into an actionable logic model. In highly simplified terms, the model gets you to (1) determine the key problem that the needs analysis indicates one needs to solve, (2) the overarching behavioural and environmental outcomes (or targets) one needs to meet to improve the problem, and (3) defining the underlying determinants of those behavioural and environmental outcomes. An example could be, “people with problematic mental health (the problem), may not consistently use psychological activities in their day-to-day lives (the outcome/target) as they do not have enough knowledge (the determinant) of the benefits of using such activities.”

Rather than arbitrarily coming up with determinants that we wished to change, we relied on the Theoretical Domains Framework (Cane et al., 2012) to guide our choice. The TDF is a framework that synthesises 14 unique determinants (e.g., knowledge, skills, and beliefs) stemming from 33 behaviour change and implementation theories. It provides a comprehensive and intuitive theory-based overview of relevant behaviour change determinants that intervention developers can use. IM requires developers to prioritise and choose only the relevant TDF determinants by assigning which determinants (1) are actually related to the problem and (2) can actually be changed. An explanation for the choice of each determinant is provided in Supplementary Appendix 1.

The result of step 1 is a logic model of change that summarises the problem, the outcomes and the determinants, which will be used to underpin the intervention.

Step 2: Define the Objectives the Intervention Needs to Meet and What the Intervention Needs to Change to Meet Those Objectives

After determining the problem that needs to be addressed, IM continuous to delineate what needs to change to solve the problem. Firstly, each target area (e.g., the lack of participation in psychological activities) identified in the needs analysis were rewritten into desired behavioural and environmental outcomes (e.g., engaging in regular use of psychological activities). Secondly, these outcomes were subsequently broken into sub-objectives called performance objectives (e.g., demonstrates knowledge on how to improve mental health). Finally, these performance objectives were broken down further into so-called change objectives. These are very specific objectives that need to be achieved in order for the performance objective to be realised (e.g., increasing knowledge of malleability of mental health). A change objective consisted of linking performance objective with determinants from the Theoretical Domains Framework (e.g., knowledge, skill, and beliefs about capabilities). The final output of step 2 was a collection of matrices, so-called matrices of change, depicting each change objective per performance objective (placed in the rows) and determinant (placed in the columns).

Step 3: Select Behaviour Change Techniques and Practical Applications of Those Techniques That Will Be Used to Achieve the Change Objectives

In step 3, a new table is created by placing the change objectives on individual rows and matching them with evidence-based “behaviour change techniques” (BCTs) (Kok et al., 2016). BCTs are theoretical strategies (e.g., goal setting, modelling, and active learning) that have been empirically proven to be able to change individual behaviour. The IM framework comes with an extensive summary of BCTs and how they can be used to create impactful interventions. It gets programme developers to match their change objectives with individual BCTs, thereby aiming to improve the chance that actual behaviour and environmental change in line with the change objective will be achieved.

The final part of step 3 is translating the theoretical BCTs into so-called “practical applications,” referring to the proposed real-world application of each BCT. For example, to achieve the change objective “Demonstrating knowledge on malleability of mental health,” the programme draws on the BCT “active learning” which can be achieved via the “practical application” of showing an engaging video on epigenetic changes that can alter our mental health (Schiele et al., 2020). The result is a line-by-line itemised list (or blueprint) of practical applications that need to be incorporated into the programme design in step 4.

Step 4: Design and Develop the Actual Intervention Components Based of the Practical Applications Identified in the Previous Step

In step 4, the programme designers created the actual intervention based on the blueprint established in step 3. This process was guided via various project team meetings. A subgroup of project team members (JA, MI, KA, DF, LW, and GF) created a programme delivery framework, outlining the proposed intervention sessions, their underpinning rationale and the delivery format. This framework was evaluated and approved by the larger multi-disciplinary project team that included end-users over a series of meetings. The subgroup continued by creating a detailed narrative for the programme, which was subsequently translated into an interactive programme. The narrative and programme content is presented in the results below.

After developing the first iteration of the programme, two small-scale in-person test runs with university students (n = 30) and colleagues of the project team members (n = 7) were conducted by JA, MI, KA, GF, and AH. Feedback from these test runs was used to iterate the programme delivery, not to determine impact on outcomes (i.e., they were test runs not evaluation studies). After iteration, each of the five session sessions were recorded on video and the programme was subsequently tested in an online delivery format, i.e., delivered via video conferencing software, resulting in the programme presented in this manuscript.

Steps 5 and 6: Adoption, Implementation, and Evaluation Plans

After finishing the design and development of the intervention, IM concludes with two additional steps, the development of an adoption and implementation plan (step 5) as well as an evaluation plan (step 6). These two steps are outside the scope of this article, as the aim here is to describe the development and design process. The actual evaluation of the programme on outcomes will be covered in subsequent publications, including a pre-post pilot study in university students and general community members (n = 89; van Agteren et al., 2021a) and a randomised controlled study in university students. A brief description of the evaluation approach is provided in the discussion of this manuscript.

Results

Step 1: The Needs Analysis of the Be Well Plan Programme

The results from the needs analysis are presented in a narrative format, combining the findings from the literature review and interrogation of qualitative and quantitative data from previous projects on wellbeing interventions our project team conducted. The needs analysis for this specific programme is structured around four distinct themes, which are outlined below. Supporting material underpinning the needs analysis can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Theme 1: There Is a Need for Mental Health Interventions to Incorporate a Specific Focus on Positive and Adaptive States, in Addition to Taking Psychological Distress Into Account

Psychological interventions for mental health are often thought of to be synonymous to interventions aimed at treating or preventing mental illness or psychological distress. This is reflected in research on psychological interventions such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and mindfulness, with studies largely focussing on their effectiveness in improving outcomes of illness and psychological distress (Hofmann et al., 2010, 2012; Swain et al., 2013). There is however general agreement that optimal mental health does not equate to a mere absence of symptoms of mental illness as it also requires participants to demonstrate high levels of mental wellbeing, e.g., finding meaning in life, working on positive relationships, and building positive emotions (Jahoda, 1958; Smith, 1959; Fontana et al., 1980; Wilkinson and Walford, 1998; Greenspoon and Saklofske, 2001; Keyes, 2003, 2005; Suldo and Shaffer, 2008). A significant body of research has found that mental wellbeing should not be seen as the mere opposite of mental illness (Iasiello et al., 2020). Studies in Western and non-Western populations demonstrate that people who exhibit psychological distress or show symptoms of mental illness have varying levels of mental wellbeing (Peter et al., 2011; Seow et al., 2016; Bariola et al., 2017; Teismann et al., 2017; Xiong et al., 2017).

There are numerous ways of building outcomes of mental wellbeing, including spending time in nature (Howell et al., 2011; Korpela et al., 2016; Passmore and Holder, 2017), being physically active (Penedo and Dahn, 2005; Windle, 2014), doing yoga (Ivtzan and Papantoniou, 2014; Sharma et al., 2017), and spending more time engaging in social relationships (Keyes, 1998; Gallagher and Vella-Brodrick, 2008) among others. Psychological interventions such as CBT, ACT and mindfulness in addition to be effective for outcomes of mental illness (Hofmann et al., 2012; Öst, 2014; Goldberg et al., 2018) have joined this list in being able to improve outcomes of mental wellbeing, in addition to being effective for distress. A recent systematic review conducted by authors of the current article examined 419 studies (n = 53,288 included in meta-analysis) which clearly demonstrated their impact in both healthy populations and populations with mental illness or physical illness (van Agteren et al., 2021b). The significant findings were dependent on the specific target population (e.g., clinical versus non-clinical populations) and other moderators, most notably intervention intensity.

Psychological interventions are not simply beneficial for improving mental health outcomes in the moment. For instance, by improving outcomes of wellbeing, they can both increase the likelihood of recovery from mental illness or can prevent the onset of illness in the future (Keyes et al., 2010; Wood and Joseph, 2010; Grant et al., 2013; Lamers et al., 2015; Iasiello et al., 2019). By focussing on improving wellbeing it makes them a viable avenue for individuals seeking to reduce symptoms of distress (Gilbert, 2012; Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2019) and to build resilience to future adversity (Fritz et al., 2018). In other words, by teaching psychological skills that take future distress and wellbeing into account, participants can be taught techniques that aim to help them withstand adversity or stress (i.e., cope with) without succumbing to more serious mental health problems (Davydov et al., 2010; Harms et al., 2018). A deliberate focus on developing this resilience, or in other words improving adaptative states, could strengthen the impact of mental health interventions, for those with and without current distress (Roy et al., 2007; Fritz et al., 2018).

Theme 2: There Is a Need for Mental Health Interventions to Target Malleable Non-psychological Determinants of Mental Health in Psychological Interventions

Our mental health is not simply determined by our thinking patterns, but rather is influenced by a myriad of bio-psycho-social influences. While not all these influences are within the control of behavioural or psychological interventions, or feasible in light of the focus for our intervention, the team determined that two aspects were. Firstly, stimulating positive change related to our physical health will be beneficial to our mental health, as both are intrinsically linked, which is demonstrated by a considerable body of scientific evidence on the importance of health promotive factors such as physical activity, nutrition and sleep, all of which can be positively addressed using behavioural interventions (Valois et al., 2004; Penedo and Dahn, 2005; Chu and Richdale, 2009; Deslandes et al., 2009; Oddy et al., 2009; Rethorst et al., 2009; Nanri et al., 2010; Gradisar et al., 2011; Rienks et al., 2013; Bernert et al., 2014; Dalton and Logomarsino, 2014; Jacka et al., 2015). Inclusion of, at minimum, rudimentary techniques that could be used to stimulate positive health behaviours was deemed necessary for our intervention. Secondly, the training needed to incorporate elements of our social environment into the intervention. Stimulating small positive change in our social environment can lead to improved mental health (Kawachi and Berkman, 2001; Santini et al., 2015; Verduyn et al., 2017). Similarly, feeling isolated and lonely exerts strong negative influence on wellbeing and mental health (Arslan, 2018; Wang et al., 2018).

Theme 3: Personalising the Mental Health Intervention to Match Individual Participant Needs Will Drive Impact and Is Feasible in Scalable Intervention Formats

In-person psychological mental health interventions outside the clinical setting tend to come in predictable formats. They often are delivered in groups (as this cost-effective), are delivered over multiple sessions, with content tending to come from (a combination of compatible) therapeutic paradigms. The content typically tends to be similar for all participants, despite the fact that personalising or tailoring interventions to individual needs might improve outcomes of interventions or improve the feasibility of its implementation (Norcross and Wampold, 2011). To improve tailoring, intervention developers often adjust the content of interventions to fit specific target populations such as students, older adults, or workforces (Waters, 2011; Shiralkar et al., 2013; Proyer et al., 2014; Robertson et al., 2015). While tailoring to group-needs is a right step in the direction, it is still removed from addressing the needs and preferences of individuals within each population group (Schork, 2015).

One potential way to achieve tailoring to individual needs is to allow participants to work on specific resources and barriers that are relevant to their unique lives. Rather than utilising an approach based on a singular therapeutic model (e.g., CBT versus ACT) the intervention could focus on modelling the approach by recent innovations such as process-based interventions; the intervention could incorporate a range of effective intervention techniques that target known “theoretically derived and empirically supported processes that are responsible for positive treatment change” rather than focussing on a specific illness, medical diagnosis or set therapeutic paradigm (Hayes and Hofmann, 2018; Hofmann and Hayes, 2019). These techniques can come from varying evidence-based interventions, for instance those identified in our systematic review on psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing (van Agteren et al., 2021b).

By facilitating tailoring to individual circumstances engagement with the intervention can be stimulated, as participants in mental health training offerings may resonate differently to different components of an intervention. This is reflected in responses to training feedback in previous projects the team conducted, see Supplementary Appendix 1. The training delivered in these projects consisted of skills stemming from CBT, mindfulness techniques and positive psychology. At the end of the training participants voices different preferences for different skills, with an eclectic response pattern noted. Allowing participants to experiment with different evidence-based techniques in an effective manner has furthermore become much more within reach with the rise of technology (Clough and Casey, 2015; Dinesen et al., 2016; Naslund et al., 2016; Naslund, 2017; Berrouiguet et al., 2018). For instance, technology can help guide activity recommendations based on an individual’s response to scientific questionnaires for mental health and wellbeing. This can allow a participant to experiment with different techniques, without the requirement for a trainer or therapist to guide choice of activities, ultimately facilitating them to independently form a personalised strategy for good mental health and wellbeing.

Theme 4: In Order to Facilitate Lasting Change, There Is a Need for Mental Health Interventions to Leverage a Focus on Behaviour Change

In order for mental health interventions to “stick,” individual participants need to change their behaviour, aligned to the goals of the intervention (Kok et al., 2016). Simply providing activities to build resources and remove challenges to good mental health may not be sufficient, for example, due to a discrepancy between intention to change behaviour and actual behaviour change (Atkins et al., 2017). Reliance on the IM approach stimulated an explicit focus on behaviour change, ultimately asking intervention developers to select key underpinning determinants that are related to the problem behaviour.

Interventions can broach this in numerous ways, depending on the determinants they consider to be the focus for the intervention. As part of the needs analysis, the project team focused on several determinants that were (1) deemed important for mental health and (2) were considered to be malleable and within reach of the current intervention. For instance, teaching skills to deal with stressors, adversity or negative social influence aids in improving the chance of engaging in wellbeing activities (Fritz et al., 2018). Knowledge has been found to be one of the essential ingredients for psychological skills to be developed (Jorm, 2012; Oades, 2017), and self-efficacy helps in the execution of skills (Leamy et al., 2011; Trompetter et al., 2017). Often there is resistance or stigma toward mental health and wellbeing activities (Clement et al., 2015; Thornicroft et al., 2016), indicating the need to focus on changing beliefs about the effectiveness of wellbeing behaviours and beliefs about the consequences of implementing those behaviours (Sheeran et al., 2016). Finally, goal-setting aids in strategy formation and achievement of physical health improvements as well as behavioural regulation via self-monitoring (Wollburg and Braukhaus, 2010; Michie et al., 2011a). A further justification for why the project team chose these determinants over others can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Use the Needs Analysis to Craft a Visual Logic Model for the Intervention

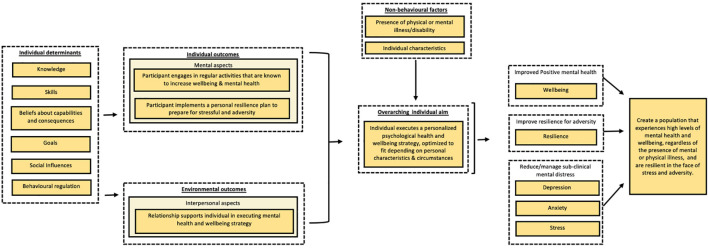

The project team subsequently set out to construct a logic model for the intervention based on the findings from the needs analysis, see Figure 2. The team followed the general structure for logic models as set out in IM and the PRECEDE-PROCEED model (Green and Kreuter, 1999). The key focus for the intervention was to help participants promote their mental health, pointing to the need for an intervention that would be able to target positive, adaptive, and distress states. The needs analysis pointed to the desire for an intervention that allowed participants to develop a personalised mental health and wellbeing strategy or “plan,” allowing participants to take their unique characteristics and health status into account. The key objective was to get participants to change their behaviour by actively engaging in evidence-based activities. These activities firstly should allow individuals to build or leverage resources that can promote mental health in the now and secondly build resources that can help the individual cope with stressors in the future. It should thirdly aim to engage the social environment as a mechanism to support the individual. To achieve the objective, and ultimately behaviour change, the intervention would target specific behaviour change determinants that were derived from the Theoretical Domains Framework Domains (Atkins et al., 2017), including knowledge, skills, beliefs about capabilities and consequences, goals, social influences, and behavioural regulation.

FIGURE 2.

Simplified overview of the needs analysis for the Be Well Plan. The specific explanatory role of variables (e.g., mediating or moderating) is not taken into account in this figure. The model merely serves to outline the variability of behaviours and determinants that influence wellbeing and resilience using the PRECEDE-PROCEED model outline. Determinants are based on the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF).

Step 2: Definition of Programme Objectives

Step 2 required the project team to create programme outcomes based on the needs analysis and the logic model. The outcomes were: participant engages in regular activities that are known to increase wellbeing and mental health, participant implements a personal resilience plan to prepare for stressful periods and adversity, participant engages relationship supports in executing their mental health and wellbeing strategy. These outcomes were further specified into performance objectives, see Table 1. Change objectives were formulated for each of the performance objectives in line with the chosen TDF determinants mentioned earlier. All matrices of change can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1.

TABLE 1.

Behavioural and environmental outcomes, and performance objectives (PO) for Complete Mental Health.

| Behavioural outcome 1: Engages in regular activities that are known to increase the mental health and wellbeing of the individual | |

| PO 1.1 | Develops understanding of mental health, and its relationship to mental illness and mental wellbeing |

| PO 1.2 | Understands that good psychological health can actively be achieved via different intervention types, regardless of physical or mental illness |

| PO 1.3 | Understands that personal characteristics influence which interventions should be selected to improve mental health |

| PO 1.4 | Understands that good psychological health requires a life-course approach |

| PO 1.5 | Is aware of personal psychological health profile (wellbeing, resilience, and psychological distress) |

| PO 1.6 | Creates overview of resources and challenges for their psychological health |

| PO 1.6.1 | Determines which resources and challenges are currently present, which can be improved on using the programme and which ones are out of scope |

| PO 1.6.2 | Determines when other programmes or services for mental health and mental wellbeing need to be considered |

| PO 1.7 | Determines personal motivators for wanting to engage in activities that promote psychological health |

| PO 1.8 | Develops a personal psychological health strategy |

| PO 1.8.1 | Identifies barriers and enablers to implementing a personal psychological health strategy |

| PO 1.9 | Maintains use of personal psychological health strategy over time |

| PO 1.10 | Evaluates implementation of psychological health strategy |

| PO 1.10.1 | Judges whether psychological health strategy is being executed successfully |

| PO 1.10.2 | Re-evaluates psychological health strategy, if not effective achieving personal outcomes |

| PO 1.10.3 | Contacts professional care when mental health and wellbeing symptoms impact personal life |

| PO 1.10.4 | Adjusts psychological health strategy and returns to PO 1.8 |

| Behavioural outcome 2: Implements a personal resilience plan to prepare for stressors and adversity | |

| PO 2.1 | Understands the concept of resilience and its relationship to psychological health |

| PO 2.2 | Understands the impact of different stressor types or adversities on psychological health (chronic versus acute, foreseen versus unforeseen) |

| PO 2.3 | Understands how effective use of psychological health strategies can lead to post adversity growth and better psychological health |

| PO 2.4 | Understand that their personal characteristics influence which interventions they should be considering to build resilience |

| PO 2.5 | Is aware of personal resilience status |

| PO 2.6 | Identifies potential resources and challenges for their resilience |

| PO 2.6.1 | Determines which resources and challenges are currently present, which can be improved on using the programme and which ones are out of scope |

| PO 2.7. | Identifies personal motivators for regularly engaging in resilience strategy |

| PO 2.8 | Develops a personal resilience plan |

| PO 2.9 | Practices resilience strategies on a regular basis regardless of presence of adversity |

| PO 2.10 | Uses resilience strategies when facing personal adversity |

| PO 2.11 | Evaluates implementation of resilience plan |

| PO 2.11.1 | Judges whether resilience strategy is being executed successfully |

| PO 2.11.2 | Re-evaluates resilience strategies if they are not effective |

| PO 2.11.3 | Contacts professional care when mental health symptoms impact personal life |

| PO 2.11.4 | Adjusts resilience strategy and returns to PO 2.8 |

| PO 2.12 | Identifies personal strength and growth in dealing with adversity |

| Environmental outcome 1: Identified relationship support helps individual in executing their mental health and wellbeing strategy | |

| PO 3.1 | Identified relationship support develops an understanding of the personal psychological health strategy of the training participant |

| PO 3.2 | Identified relationship support participates in individual’s psychological health activities when requested |

| PO 3.4 | Identified relationship support checks up if individual is practicing use of strategies over time |

| PO 3.5 | Identified relationship support reminds individual of thinking about mental health strategies when stress or adversity hits |

| PO 3.6 | Identified relationship support determines whether engaging in training may be beneficial for themselves |

Step 3: Evidence-Based Behaviour Change Techniques and Practical Applications

The change objectives developed for each of the performance objectives in step 2 were placed in a new table. In step 3 these change objectives were matched to evidence-based BCT’s (10) in Table 2. The table mentions each specific BCT as well as the psychological theories they come from. For each BCT, the programme team then constructed practical applications that were to be implemented in the programme. The result is a line-by-line theoretical blueprint for the programme.

TABLE 2.

Combined table for behavioural outcome 1 (engages in regular activities that are known to increase wellbeing and mental health of the individual), behavioural outcome 2 (practices resilience activities to prepare for times of stress and adversity), and environmental outcome 1 (relationship supports individual in striving for more wellbeing and resilience).

| PO | Change objectives | BCT | Theory | Practical applications | |

| Demonstrates understanding of (higher order comprehension) | |||||

| K1.1a | – Mental health, wellbeing and mental illness | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Elaboration (6.6) 3. Using Imagery (6.6) 4. Arguments (6.9) 5. Repeated Exposure (6.9) 6. Cultural Similarity (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. IPT, ELM 3. TIP 4. CPM, ELM 5. TL 6. CPM |

1. An image/video/text that displays the relationship of mental health, wellbeing & mental illness. Use real-world examples throughout to make it easier to comprehend. 2. Provide facts about psychological health and how it affects everyone on a day-to-day basis (includes definitions) and getting participants to relate this to their own psychological health. 3. Use physical fitness and physical health as analogies to the relationship between mental illness and wellbeing. 4. Discuss the evidence that underpins dual-factor models, wellbeing and mental illness individually (includes definitions) and get participant to understand the differences and how these differences apply to their own mental health. 5. Show visualisation of mental health, wellbeing and mental illness repeatedly throughout the programme and reaffirm notion that psychological health is relevant to all of us irrespective of clinical symptoms during different sessions. 6. Where possible use examples, statistics and support material that is relevant to the participant group (e.g., students, workforces, etc.). |

|

| K1.2b | – The way different intervention types influence psychological health | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Active learning (6.5) 3. Elaboration (6.6) 4. Using Imagery (6.6) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. ELM, SCT 3. IPT, ELM 4. TIP |

1. Provide a brief explanation how different intervention types improve relevant outcomes, and what their scientific evidence is (on a high level). 2. Ask participants to guess which intervention type across the board influences most mental health outcomes. 3. Provide explanatory videos that shed insight into background mechanics of interventions (e.g., video on epigenetic influences on our life). 4. Use examples of healthy pot-plants versus garden-grown plants to explain that psychological health can be influenced by genetics and environment, and that this impacts intervention impact. |

|

| K1.2c | – Current evidence-status for individual intervention types on improving psychological health | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Advance Organisers (6.6) 3. Arguments (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TIP 3. CPM, ELM |

1. Give a general evidence overview of the main intervention types and their impact on psychological health. Include information about the benefits of improving psychological health for everyone. 2. Use symbols, way of organising and colours to indicate evidence status for individual techniques. 3. Provide high level summary of evidence for each activity proposed, split per main target outcome. Provide access to background research and get participants to realise that different types of interventions have a different impact depending on the outcome and other characteristics. |

|

| K1.3a | – Personal characteristics that have a proven association with psychological health | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Elaboration (6.6) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. IPT, ELM |

1. Briefly list scientific evidence on personal characteristics that impact psychological health and their relation. 2. Use videos (e.g. on impact of stress) to indicate that biopsychosocial influences all play a role in how we feel. |

|

| K1.3b | – Personal characteristics that are known to impact interventions for psychological health | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Advance Organisers (6.6) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TIP |

1. Provide explanation on differential response for different people and the need for one-size fits all solutions based on background research. Place in larger frame of resources and challenges. 2. Create groupings were possible to make information processing easier (e.g., psychological, health, interpersonal). |

|

| K1.4a | – The presence of fluctuations in psychological health outcomes throughout life | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Active learning (6.5) 3. Elaboration (6.6) 4. Using Imagery (6.6) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. ELM, SCT 3. IPT, ELM 4. TIP |

1. Provide high-level scientific evidence on daily mood and wellbeing fluctuations. 2. Embed measurement and reporting on mental health into programme, showing fluctuations over time. 3. Stimulate conversation between attendees regarding observed fluctuations. 4. Use the example of the weather and climate or alternatively progress in sports and physical health to explain how individual fluctuations in mental health work. |

|

| K1.4b | – Psychological health over the life-course requires a committed approach | 1. Active learning (6.5) 2. Modelling (6.5) 3. Using Imagery (6.6) |

1. ELM, SCT 2. SCT, TL 3. TIP |

1. Ask participants to reflect on whether anything that plays a big role in life comes overnight. 2. Get trainers to talk about their own life course approach to building mental health. 3. Use analogy of marathon (or other big accomplishment) to explain that this journey is long. Use imagery to explain it is not a linear trajectory and that we will have wins and losses in this journey. |

|

| K1.5b | – Psychological health consists of different personal outcomes | 1. Arguments (6.9) 2. Advance Organisers (6.6) |

1. CPM, ELM 2. TIP |

1. Use definitions on mental health and distinct sub-outcomes to indicate the role that each outcome plays. 2. Break up definitions and guide participants through each relevant sub-outcome to create understanding of differences. |

|

| K1.6d | – Importance of social relationships | 1. Persuasive communication (6.5) 2. Repeated Exposure (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TL |

1. Provide clear rationale for the importance of social environment in our mental health and wellbeing, by referring to theories, evidence and examples throughout the programme. 2. Repeat importance of social environment throughout sessions. |

|

| K1.6.1a | – Scope of the programme | 1. Persuasive communication (6.5) 2. Repeated Exposure (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TL |

1. Clearly articulate that the main focus of the programme is to build mental health, not to focus on mental illness. Explain the difference between those concepts clearly. 2. Repeat information on scope throughout course. |

|

| K1.6.1b | – Types of challenges that cannot be altered by a psychological skills training | 1. Persuasive communication (6.5) | 1. CPM, ELM, DIT | 1. Provide clear rationale for focus on mental health and not mental illness or other problems that may contribute to problems in mental health (e.g. housing, finances) from start of the programme. Point to presence of external influences that can shape mental health and indicate that improvement potential differs per person and their environment. | |

| K1.7b | – The role that values play in steering positive human behaviours | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Active Learning (6.6) 3. Discussion (6.6) 4. Using Imagery (6.6) 5. Arguments (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. ELM, SCT 3. ELM 4. TIP 5. CPM, ELM |

1. Give insight into scientific evidence on role of values and life goals, and how values relate to positive health behaviours and goal attainment. Share different theories that they play a role in (e.g. ACT). 2. Get participants to identify their own values in past behaviour and link this to new goals they set related to their mental health and wellbeing. 3. Talk through individual values with other participants. 4. Ask participants to think about a time when they relied on their values to steer positive behaviour. 5. Provide scientific arguments for the role of values in positive human behaviour and indicate that everybody has certain values they hold, which they can use to influence their mental health. |

|

| K1.8a | – The importance of developing a strategy of sufficient intensity | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Elaboration (6.6) 3. Using Imagery (6.6) 4. Arguments (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. IPT, ELM 3. TIP 4. CPM, ELM |

1. Provide scientific evidence on developing a strategy of sufficient intensity across different outcomes. Rhetorically, ask participants to think of the last time they nailed an important life skill (driving a car, having sex, learning a new language) in one go. 2. Ask participants to place the importance of investing in their mental health by developing a strategy of sufficient intensity in the context of their own life, motivations, and values. 3. Use physical activity as an example to explain how it is important to train sufficiently when trying to run a marathon (your life). Alternatively use medicine as an example. 4. Provide the results of the systematic review to develop scientific trust in presented findings and need to fully commit to developing a strategy. |

|

| K.1.8.1 | – How barriers can influence successful execution of the psychological health strategy | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Repeated Exposure (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TL |

1. Provide information on various barriers, both theoretical and from the trainer’s own experience, and how participants need to be aware of them to be successful in executing the strategy. 2. Repeat information and cues on reflecting on barriers throughout the programme (e.g. during reflection on how previous weeks went at start of each session). |

|

| K1.9 | – Improving or maintaining psychological health requires an ongoing commitment | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Using Imagery (6.6) 3. Arguments (6.9) |

1. CPM ELM, DIT 2. TIP 3. CPM, ELM |

1. Provide information on typical trajectory of improvement, indicating that sometimes a deterioration may happen before positive change occurs. 2. Use analogies of sports or other areas to indicate that improvement comes with ups and downs. 3. Provide realistic optimism as an approach to indicating that success can happen despite failures, but requires ongoing commitment. |

|

| K1.10.1a | Different people require different strategies to see effective change in outcomes | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Active Learning (6.5) 3. Modelling (6.5) 4. Using Imagery (6.6) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. ELM, SCT 3. SCT, TL 4. TIP |

1. Provide examples of difference in people responding to different strategies, both in effectiveness as well as implementation and liking. 2. Let people interact with their own wellbeing scores and compare changes with other participants. 3. Over course of the programme get participants to discuss their personal strategy, showing that individuals will gravitate to and need different activities depending on their life’s circumstances 4. Provide analogy of the way psychologists and counsellors work in finding ways to work with their clients. |

|

| K1.10.3a, K2.8.2b, K2.11.3a | Personal situation/outcome that warrants professional support | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Using Imagery (6.6) 3. Consciousness Raising (6.7) 4. Personalise Risk & framing (6.7) 5. Repeated Exposure (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TIP 3. HBM, PAPM, TTM 4. PAPM 5. TL |

1. Provide scientific evidence on differing levels of symptoms and the effectiveness of different techniques on dealing with symptoms, leading participants to understand they can’t take everything on themselves. 2. Use analogy of going to the GP and ED for severe physical illness and the need to go to the pharmacy yourself when it is minor. Use analogy of various fires to indicate that you can deal with some fires but not with all (i.e. you need to call the fire department). 3. Make it clear that not understanding about severity of symptoms can impact them in forming an effective strategy and thus in being able to improve their mental health. 4. Provide information on the long-term impact of not acting on their mental health, and how this may impact the participant’s future 5. Repeat symptoms message and need to know which symptoms can be manageable or not throughout programme. |

|

| K1.10.4 | Adjusting a strategy may lead to better outcomes over the life-course | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Using Imagery (6.6) 3. Repeated Exposure (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TIP 3. TL |

1. Ensure that the participant knows that creating and tweaking a strategy is the core principle of the programme and generally underpins growth. 2. Provide analogies such as sports and adjusting training to improve outcomes. 3. Reinforce the message each session by allowing participants to experiment with their strategy. |

|

| K2.1b | – Resilience as an outcome | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Active learning (6.5) 3. Discussion (6.6) 4. Elaboration (6.6) 5. Arguments (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. ELM, SCT 3. ELM 4. IPT, ELM 5. CPM, ELM |

1. Provide scientific definitions of resilience and place in context of its malleability (i.e. resilience as an outcome you can change). 2. Ask participants to think of a time where they felt they were resilient to stress or stressful events. 3. Get participants to talk through learned information on resilience and other mental health outcomes. 4. Get participants to reflect on concept of resilience and how this relates to their life. 5. Throughout programme provide scientific information on why resilience is malleable. |

|

| K2.2c | – How stress can lead to growth | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Modelling (6.5) 3. Elaboration (6.6) 4. Using Imagery (6.6) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. SCT, TL 3. ELM 4. TIP |

1. Provide information on scientific evidence regarding post stress growth and the positive consequences of stress 2. Get trainers to provide an example where they felt they went through stress and grew afterward. 3. Ask people to think about a time where they felt they grew after going through stress 4. Use bushfires as an analogue of a completely destructive force, but nature recovering afterward. Alternatively use examples of physical activity when someone suffered an injury and miraculously recovered. |

|

| K2.6b | That resources and barriers for resilience can change over time | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Modelling (6.5) 3. Using Imagery (6.6) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. SCT, TL 3. TIP |

1. Provide information on the transient nature of resources and barriers in one’s life and that we can actively work on them. 2. The trainer will provide the group with an example where their own resources and barriers shifted in life and how it impacted an outcome. 3. Use analogy of the life course to show that we all evolve and as a consequence our resources shift. |

|

| K2.8b | What stressor types can and cannot be managed individually | 1. Facilitation (6.5) 2. Modelling (6.5) 3. Using Imagery (6.6) |

1. SCT 2. SCT, TL 3. TIP |

1. Recommendations based on clinical cut-offs are presented within online measurement and accompanied by explanatory text. They indicate which symptom levels recommend being seen a professional 2. Trainer provides example from their own life in which they had to decide whether to get help or not to deal with stressors (where applicable). 3. Use medical or fire analogy to indicate that some events can be managed personally and some benefit from professional help. |

|

| K2.10b | Individual differences in capacity to deal with adversity | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Using Imagery (6.6) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TIP |

1. Provide scientific literature that indicates individual differences in coping and their determinants (e.g., genomics video) and the role of perception in stress. 2. Use analogy from nature that highlights differences between people and being able to deal with stress. |

|

| K2.10c | That individual judgement may need to be supplemented with input from social environment | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) | 1. CPM, ELM, DIT | 1. Provide scientific evidence on important role of social support and positive relationships, as well as the environment in general. Explain the role that the mind plays in interpreting symptoms and that an outsider’s perspective can help in overcoming biases. | |

| Lists/describes (descriptive knowledge) | |||||

| K1.1b | – Behavioural and non-behavioural factors and outcomes that are associated with good psychological health outcomes | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Active learning (6.5) 2. Arguments (6.9) 3. Repeated exposure (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. ELM, SCT 3. CPM, ELM 4. TL |

1. List various scientifically derived behavioural and non-behavioural factors. 2. Ask participants to choose from a large set of associated variables and ask which ones they care about or has impacted their own personal lives. 3. Provide scientific evidence that indicates the role of each factor in relationship to psychological health via links to resources page. 4. Repeat behavioural and non-behavioural factors information throughout course. |

|

| K1.1c | – Positive outcomes associated with good psychological health | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Advance organisers (6.6) 3. Active learning (6.5) 4. Arguments (6.9) 2. Repeated Exposure (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 3. TIP 4. ELM, SCT 5. CPM, ELM 6. TL |

1. List scientific evidence to support positive outcomes of working on good psychological health. 2. Break the positive outcomes down into subsets of groups to facilitate better information processing. 3. Ask participants to choose from a large set of associated variables and ask which ones they care about or has impacted their own personal lives. 4. Provide scientific references that indicate their association with psychological health. 5. Repeat information on positive outcomes throughout sessions. |

|

| K1.2a | – Evidence-based psychological interventions to build psychological health | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Advance Organisers (6.6) 3. Active learning (6.5) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TIP 3. ELM, SCT |

1. List scientific evidence on evidence-based intervention types to build psychological health. 2. Group interventions into different sub-types to aid in retention. 3. Create a short puzzle/quiz that gets people to reflect on the impact of specific interventions on specific outcomes. |

|

| K1.6a | – Common resources and challenges for good psychological health | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Advance organisers (6.6) 3. Active learning (6.5) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TIP 3. ELM, SCT |

1. List scientific evidence on commonly understood resources and challenges. 2. Group resources and challenges into clearly understandable groups. 3. Ask participants to reflect on resources and challenges and their importance to the participant. |

|

| K1.7a | – List of motivators that drive human (health) behaviour | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Active learning (6.5) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. ELM, SCT |

1. List common motivators for health behaviour change and their scientific evidence. 2. Ask participants to think of their own motivators related to psychological health and refer back to these motivations throughout the course. |

|

| K1.7b | – Values that drive human (health) behaviour | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) | 1. CPM, ELM, DIT | 1. Provide list of values including the definition of values. Provide scientific background to values, virtues and strengths and how they lead to improved mental health. | |

| K1.7c | – What a growth mindset is and how it aids in mental health improvement | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Arguments (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. CPM, ELM |

1. Provide examples on a growth mindset versus a fixed mindset and how both relate to improvements in outcomes. Focus is on malleability, not the theory per se. 2. Relate growth mindset back to scientific evidence on change in mental health outcomes and role of nature/nurture (e.g. via epigenetics video) |

|

| K1.8a | – Different activities that can be used to improve resources and offset barriers to psychological health | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Advance organisers (6.6) 3. Arguments (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TIP 3. CPM, ELM |

1. List variety of recommended activities that are known to improve psychological health. 2. Group activities into easily understood topic areas (feeling, doing, communicating, thinking). 3. Provide scientific rationale for each individual activity and the way we currently understand they impact mental health (outcomes). |

|

| K1.8d | – Possible strategies they can consider to grow social connections as part of strategy | 1. Facilitation (6.5) | 1. SCT | 1. Provide examples and exercises that participants can use to involve their social network in the programme. | |

| K1.10.3b, K2.11.3b | – Contact information for professional support | 1. Facilitation (6.5) 2. Repeated Exposure (6.9) |

1. SCT 2. TL |

1. Provide clear overview of professional support contacts. 2. Repeatedly show the contact information for professional support throughout the programme. |

|

| K2.1a, K2.2a | – The concept of stress and stressors, and their consequences | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Repeated Exposure (6.9) Elaboration (6.6) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TL 3. TIP, ELM |

1. Provide the definition of stress and a variety of examples ranging from mild to big adversity, and how they impact individuals differently. 2. Repeat definitions throughout the course. 3. Explore concept of eustress and how this applies to the individual. |

|

| K2.1c | – Positive outcomes associated with improved resilience | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Repeated Exposure (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 3. TL |

1. Provide scientific evidence on positive outcomes associated with resilience. 2. Repeatedly frame the benefits of high resilience being a positive outcome. |

|

| K2.2b | – How stressors can be appraised differently and how this impacts stress levels | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) | 1. CPM, ELM, DIT | 1. Touch upon various stressors and the fact that stressors influence people differently, which partly depends on their level of severity and other variables. | |

| K2.3b | – Evidence-based activities that can boost resilience | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Advance organisers (6.6) 3. Repeated Exposure (6.9) 2. Facilitation (6.5) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TIP 3. TL 4. SCT |

1. Provide scientific evidence for list of activities that boost resilience. 2. Group activities into categories (feeling and thinking, doing, communicating). 3. Refer to different activities throughout course. 4. Provide overview of evidence via website or other resources. |

|

| K2.3c | – Positive effects associated with engaging in resilience activities | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Repeated Exposure (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TL |

1. Provide scientific evidence on positive outcomes associated with resilience and their flow-on effects on other mental health outcomes. 2. Repeatedly frame the benefits of resilience and the fact that it is malleable. |

|

| K2.4 | – Role of biology, psychology and social circumstances on resilience | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Active Learning (6.5) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. ELM, SCT |

1. Provide scientific evidence on characteristics that influence resilience (and other mental health outcomes). 2. Integrate knowledge by linking resilience to other videos on mental health used in the programme. |

|

| K2.6a | – Common resources and challenges for resilience | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Repeated Exposure (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TL |

1. Provide scientific evidence on common resources and challenges for resilience and coping with stress. 2. Repeat the common resources and challenges throughout the course. |

|

| K2.8a | – Activities that can be used for personal resilience strategy | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Advance Organisers (6.6) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. TIP |

1. List scientific evidence on evidence-based interventions types to build resilience. 2. Group interventions into different sub-types to aid in retention. |

|

| K2.8b | – What stressor types can and cannot be managed individually | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) | 1. CPM, ELM, DIT | 1. Provide information on aspects that are in scope and out of scope to be self-managed. | |

| K2.10a | – The mental and physical health symptoms associated with unhealthy reactions to stress | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Active Learning (6.5) 3. Repeated Exposure (6.9) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. ELM, SCT 3. TL |

1. List scientifically derived symptoms that can come from adversity and stress. 2. Use video to explain symptoms associated with stress. 3. Repeat information on stress symptoms throughout programme. |

|

| K2.11.2 | – Barriers to executing psychological health strategies | 1. Active Learning (6.5) 2. Repeated Exposure (6.6) |

1. IPT, ELM 3. TL |

1. Ask participants to reflect on barriers that have inhibited them from executing health behaviours in the past. 2. Repeat the need to reflect on barriers throughout the programme. |

|

| Explains (procedural knowledge) | |||||

| K1.5a, K2.5 | – How to access psychological outcome assessment methods to build psychological profile and resilience | 1. Advance organisers (6.6) 2. Modelling (6.5) 3. Guided practice (6.11) |

1. TIP 2. SCT, TL 3. SCT, TSR |

1. Break up steps of accessing the platform into simple steps. 2. Have a trainer explain how to access the measurement tools. 3. Develop video that explains how to access the platform and how to conduct the measurement. |

|

| K1.6.1c | – Where to find help for psychological issues out of scope of the programme | 1. Advance Organisers (6.5) 2. Facilitation (6.5) |

1. TIP 2. SCT |

1. Create a process for participants to find information on additional out-of-scope resources. 2. Create overview for relevant professional support references. |

|

| K1.8b | – How to access activities that can be used improve psychological health | 1. Advance Organisers (6.6) 2. Guided practice (6.11) 3. Modelling (6.5) |

1. TIP 2. SCT, TSR 3. SCT, TL |

1. Visualise the steps of accessing the activities in a simple diagram. Use colours, ordering and symbols to guide participants to activities within the booklet. 2. Have trainers demonstrate how to access each activity and use it to form a strategy. 3. Have trainers demonstrate use of the support material to the participant. |

|

| Identifies | |||||

| K1.6b, K1.6c, K2.6c, K2.6d | – Personal resources and barriers for their psychological health and resilience | 1. Tailoring (6.5) 2. Modelling (6.5) 3. Providing Cues (6.6) 2. Framing (6.7) 3. Public commitment (6.8) 4. Arguments (6.9) |

1. TTM, PAPM, PMT, CPM 2. SCT, TL 3. TIP 4. PMT 5. TAIHB 6. CPM, ELM |

1. Ask participants to reflect on personal circumstances and select different types of resources and barriers that apply to their own life. 2. Let trainers select types of barriers and resources that applied to their own psychological health out of list of options. 3. Indicate the consequence of not identifying personal resources, i.e., they can still do the course, but the results will be suboptimal. 4. Use a gain frame to indicate that identifying resources will lead to positives and that not identifying it will come at a cost. 5. Get participants to talk to other participants about their own resources and how it shaped their strategy. 6. Provide scientific rationale for the importance of selecting personal resources and barriers. |

|

| K1.8c | – Specific strategies that contribute positively to their psychological health | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Modelling (6.5) 3. Discussion (6.6) 4. Consciousness Raising (6.7) 5. Framing (6.7) 6. Public Commitment (6.8) |

1. CPM, ELM, DIT 2. SCT, TL 3. ELM 4. HBM, PAPM, TTM 5. PMT 6. TAIHB |

1. Provide scientific rationale for individual psychological strategies and when to consider them. 2. Have a trainer demonstrate how they selected a strategy that was matched to their own wellbeing profile. 3. Share one of the strategies the participant chose with another participant and explain why this was matched to their personal circumstances. 4. Point to consequences of not selecting strategies that relate to their own psychological health (e.g., suboptimal outcomes) and their wellbeing profile. 5. Use a gain frame to indicate that identifying strategies will lead to positives and that not identifying it will come at a cost. 6. Get participants to pledge to identify and explore tailored strategies on a weekly basis. |

|

| K1.8.1 | – How barriers can influence successful execution of the psychological health strategy | 1. Discussion (6.6) 2. Consciousness Raising (6.7) 3. Arguments (6.9) |

1. ELM 2. HBM, PAPM, TTM 3. CPM, ELM |

1. Share one of the barriers the participant chose with another participant and explain how this affected their strategy. 2. Point to consequences of not selecting personal barriers that relate to their own psychological health (e.g., suboptimal outcomes) and their wellbeing profile. 3. Provide rationale for the importance of selecting personal resources and barriers. |

|

| K1.10.1, K2.10.1 | – Personal criteria for successful execution of psychological health strategy | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) | 1. CPM, ELM, DIT | 1. Provide information on the importance of determining what success looks like, how to measure it and how to use it in the context of the programme. | |

| Demonstrates ability to | |||||

| S1.1, S2.1, S2.2 | – Process information on psychological health | 1. Facilitation (6.5) 2. Set Graded tasks (6.11) |

1. SCT 2. SCT, TSR |

1. Facilitate the creation of workbooks and the opportunity to access the materials. Provide sufficient time to allow ability to master information. Ensure access to in-person resources and space to participate in the training. 2. Gradually build complexity of information in programme to facilitate better processing of information. |

|

| S1.2, S2.3, S2.4b | – To critically interpret evidence on interventions to improve psychological health | 1. Facilitation (6.5) 2. Guided practice (6.11) |

1. SCT 2. SCT, TSR |

1. Create access to evidence on interventions to improve psychological health in slides and course material. Transform scientific formats into laymen friendly resources. Provide access to scientific resources where possible. 2. Demonstrate how to interpret evidence related to personal situation. Use an example to get the participants to interpret the evidence. |

|

| S1.3, S1.6, S1.7, S2.4a, S2.6, S2.7 | – Reflect on personal characteristics that apply to the individual | 1. Facilitation (6.5) 2. Provide contingent rewards (6.11) 2. Modelling (6.5) |

1. SCT 2. TL, TSR 3. SCT, TL |

1. Provide safe opportunity and space to reflect on individual characteristics without causing resistance of the individual. Create exercises that are specifically designed to reflect on personal lives. 2. Praise and encourage participation even though it may require people to reflect on difficult subjects. 3. Use trainer examples to highlight how reflection is done in the context of the programme. |

|

| S1.6.1 | Which resources and challenges can be managed or improved by themselves | 1. Facilitation (6.5) | 1. SCT | 1. Use online measurement to indicate whether symptom levels are higher than should be self-managed. Get participants to link resources and challenges to symptoms level. | |

| S1.10.3c | Compare the objectives of existing programme to other services | 1. Facilitation (6.5) | 1. SCT | 1. Provide overview of focus areas for the programme, what is in and out of scope and point to other services to handle out of scope objectives. | |

| S1.7, S2.7 | – Identify personal motivators to improve psychological health and resilience | 1. Tailoring (6.5) 2. Modelling (6.5) 3. Consciousness Raising (6.7) 4. Framing (6.7) 5. Discussion (6.5) 6. Arguments (6.9) 7. Facilitation (6.5) |

1. TTM, PAPM, PMT, CPM 2. SCT, TL 3. HBM, PAPM, TTM 4. PMT 5. ELM 6. CPM, ELM 7. SCT |

1. Ask participants to reflect on personal circumstances and motivators, and reflect on what motivates them in general life. 2. Let trainers demonstrate their own motivators and drivers in life. 3. Indicate the consequence of not identifying motivators, i.e., they can still do the course, but the results will be suboptimal. 4. Use a gain frame to indicate that identifying motivators will lead to positives and that not identifying it will come at a cost. 5. Ask participants to share their own motivators. 6. Provide scientific rationale for the importance of selecting personal resources and barriers 7. Provide resources to reflect on personal motivators, e.g., self-reflection exercises |

|

| S1.5b, S2.5b | – Ability to interpret scores on psychological health assessment methods | 1. Facilitation (6.5) | 1. SCT | 1. Facilitate access to assessment criteria and their interpretation to ensure the participant understand current profile, without the need for a professional to help explore scores. Provide clear explanation via slides on how to interpret scores when in-person training is taught. | |

| S1.8d | – Match intervention activities to personal needs | 1. Tailoring (6.5) 2. Facilitation (6.5) |

1. TTM, PAPM, PMT, CPM 3. SCT |

1. Create tailored recommendations for interventions based on psychological profile and identified needs 2. Facilitate resources (online/offline) that match recommendations with intervention recommendations. Match booklet recommendations to wellbeing profile generated by platform, e.g., activity finders. |

|

| S1.10.1a, S2.11.1 | – Reflect on whether strategy activities are leading to change | 1. Self-monitoring (6.11) 2. Facilitation (6.5) |

1. TSR 2. SCT |

1. Patient is prompted to keep track of use of strategy (e.g., in diary) on weekly basis and to reflect on their personal experience with the strategies. 2. The training will provide resources to enable reflection and self-monitoring, including access to a self-monitoring too (i.e. the online platform). |

|

| S1.10.2b | – Explain psychological health strategy to social supporter | 1. Modelling (6.5) 2. Facilitation (6.5) |

1. SCT, TL 2. SCT |

1. Use personal stories where the trainer or models explain how they talked to their relationships. 2. Provide a specific exercise that gets participants to share their strategy with their social supporter. |

|

| S1.10.3b, S2.11.3 | – Reach out to professional support | 1. Facilitation (6.5) 2. Set graded tasks (6.11) |

1. SCT 2. SCT, TSR |

1. Provide access to support contact information in training and resources. 2. Tell participants to come up to trainer in case they are unsure of how to broach problems or where to go with challenges. |

|

| S2.10 | – Recognise stress when faced with it | 1. Self-monitoring (6.11) 2. Facilitation (6.5) |

1. TSR 2. SCT |

1. Allow function where participant can monitor stressors over a set period when revising and checking their strategy. 2. Provide for self-monitoring functionality in course content as well as measurement platform. Allow participants to practice recognising stressors. |

|

| S2.6.1 | – To identify stressors which can and cannot be managed personally | 1. Self-monitoring (6.11) 2. Facilitation (6.5) |

1. TSR 2. SCT |

1. Allow diary function where participant can monitor stressors over a monthly period when revising and checking their strategy. 2. Provide for self-monitoring functionality in course content. |

|

| S1.5a, S2.5a | Can complete psychological health assessment methods | 1. Facilitation (6.5) | 1. SCT | 1. Embedding the psychological health assessment as part of the training in an online environment that can be accessed with any device that adheres to modern web standards. | |

| Practices | |||||

| S1.8a, S2.8a | – The use of psychological health activities during the training | 1. Modelling (6.5) 2. Feedback (6.5) 3. Reinforcement (6.5) 4. Facilitation (6.5) 5. Guided practice (6.11) 6. Verbal persuasion (6.11) |

1. SCT, TL 2. TL, GT, SCT 3. TL, SCT 4. SCT, TSR 5. SCT, TSR 6. SCT, TSR |

1. The trainer displays certain activities during the training. Videos with appropriate models are embedded within the activities were possible. 2. The trainer provides feedback on execution or practice of tasks. 3. The trainer provides praise to general group after completing an activity. 4. Individual practices activities during training time, guided by explanations or by modelling activities by the trainers. Examples are provided in course material. 5. Participants are asked to highlight tasks they have difficulty with and can act as models in a simulation to both get feedback and provide information to other participants. 6. Provide information about the fact that all skills are designed to be used by anyone, regardless of their individual knowledge and skill level. |

|

| S1.8b, S2.8b | – The use of psychological health activities after training | 1. Modelling (6.5) 2. Feedback (6.5) 3. Reinforcement (6.5) 4. Facilitation (6.5) 5. Guided practice (6.11) 6. Verbal persuasion (6.11) |

1. SCT, TL 2. TL, GT, SCT 3. TL, SCT 4. SCT, TSR 5. SCT, TSR 6. SCT, TSR |

1. Trainer gives examples on how they used the activities outside of the training. They provide examples of how they embedded the activities within their own life. 2. The trainer provides feedback on execution or practice of tasks at subsequent sessions. 3. The trainer provides praise after successfully practicing the activities during previous weeks. Emails are sent as reinforcement. 4. Provide course materials and activity sheets to allow practicing at home. Provide tips and tricks on how to embed activities within their own life. 5. Implementation within normal life of skills is stimulated. 6. The trainer provides examples of how they practiced skills within their normal life. |

|

| S1.8.1b, S2.11.2 | Develops strategy to overcome barriers to using psychological health activities | 1. Reinforcement (6.5) 2. Facilitation (6.5) 3. Planning coping responses (6.11) |

1. TL, SCT 2. SCT, TSR 3. ATRPT, TSR |

1. Provide verbal reinforcement to continue to work through barriers that are encountered during the programme 2. Provide resources to allow participants to reflect on barriers. 3. Provide potential examples that participants can consider when devising a plan to overcome the barriers. Provide exercise that gets participants to reflect on future barriers. |

|

| S1.8c | Develops competency in use of psychological health activities in day-to-day life | 1. Reinforcement (6.5) 2. Facilitation (6.5) 3. Guided practice (6.11) |

1. TL, SCT 2. SCT, TSR 3. SCT, TSR |

1. Provide praise throughout the course when activities and exercises are completed. Allow reflection after each session to reinforce progress. 2. Provide resources that permit rehearsing activities. 3. The trainer selects specific skills and demonstrates it in the course. The coursebook refers to multimedia context that further explains skills so the participant can practice. |

|

| S1.9b | Recognises when to use specific activities to improve psychological health | 1. Guided practice (6.11) 2. Facilitation (6.5) 3. Self-monitoring (6.11) |

1. SCT, TSR 2. SCT 3. TSR |

1. Participant practices recognising symptoms or activities that warrant them using their strategy. 2. The course content will prompt participants to match activities to life events, stressors and outcomes (symptoms). 3. The course material provides ability to reflect on specific triggers that warrant the use of activities. |

|

| Express positive attitude | |||||

| BI1.1, BI1.2, BI2.2 | - Toward learning about psychological health and learning about different interventions to build psychological health | 1. Belief selection (6.5) 2. Consciousness Raising (6.7) 3. Personalise Risk (6.7) 4. Framing (6.7) 5. Self-reevaluation (6.7) 6. Environmental reevaluation (6.7) |

1. TPB, RAA 2. HBM, PAPM, TTM 3. PACM 4. PMT 5. TTM 6. TTM |

1. Ask participants to determine why the training would have personal value and follow this with examples of benefits of attending the training in each potential category. 2. Indicate the scientific evidence on the importance of good psychological health for individuals, their work, their family and other drivers. Provide evidence on malleability of psychological health. 3. Relate information on psychological health back to the participant’s personal situation. 4. Explain that not participating in the training will lead to a loss, whereas participating will lead to a gain. 5. Ask participants to reflect on how their life would benefit if they were to learn about psychological health. 6. Ask participants why participating in the training would be beneficial for their loved ones. |

|

| BI1.3, BI2.4 | – Toward interrogating personal characteristics and needs | 1. Consciousness Raising (6.7) 2. Modelling (6.5) |

1. HBM, PAPM, TTM 2. SCT, TL |

1. Provide scientific information and personal examples to highlight the benefits of interrogating personal needs. Indicate that this leads to better results in the programme. 2. Let trainers provide examples of where reflection on personal needs led to benefits for the trainer. |

|

| B1.5a, BI2.5a | – Toward validity of psychological health assessment methods | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Consciousness Raising (6.7) |

1. CAPM, ELM, DIT 2. HBM, PAPM, TTM |

1. Provide scientific evidence on reliability and validity of assessment tools and their use in everyday life. Explain how they are used in other health settings. 2. Provide overview of benefits of using the assessment tools in relationship to the course and their general life. |

|

| B1.5b, BI2.5b | – Toward measuring their psychological health profile over time | 1. Verbal Persuasion (6.11) 2. Consciousness Raising (6.7) 3. Using Imagery (6.6) |

1. SCT, TSR 2. HBM, PAPM, TTM 3. TIP |

1. Provide information on fluctuations of outcomes throughout life and the need to repeat measurements. 2. Provide overview of benefits of using the assessment tools in relationship to the course and their general life. 3. Use analogy of physical health or weight to show how we fluctuate over time. Or alternatively use the weather and climate analogy. |

|

| BI1.7a, BI2.7a | – That psychological health training will be beneficial | 1. Persuasive Communication (6.5) 2. Consciousness Raising (6.7) |

1. CAPM, ELM, DIT 2. HBM, PAPM, TTM |

1. Provide evidence on how training can lead to important benefits in people’s life across a number of domains. 2. Get participants to reflect on why training will be relevant to their own personal life and motivators. |

|

| BI1.8a, BI2.8a | – That psychological health strategy will be beneficial | 1. Consciousness raising (6.7) 2. Self-reevaluation (6.7) |

1. HBM, PAPM, TTM 2. TTM |

1. Provide information on benefits of executing psychological health activities. 2. Encourage the participants to think about the benefits of enacting the strategy and what personal loss it would be to not complete the strategy. |

|

| BI1.6 | – Expanding social support | 1. Consciousness raising (6.7) 2. Self-reevaluation (6.7) |

1. HBM, PAPM, TTM 2. TTM |