Abstract

Tests that detect the presence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) antigen in clinical specimens from the upper respiratory tract can provide a rapid means of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) diagnosis and help identify individuals who may be infectious and should isolate to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission. This systematic review assesses the diagnostic accuracy of SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection in COVID-19 symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals compared to quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and summarizes antigen test sensitivity using meta-regression. In total, 83 studies were included that compared SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen-based lateral flow testing (RALFT) to RT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2. Generally, the quality of the evaluated studies was inconsistent; nevertheless, the overall sensitivity for RALFT was determined to be 75.0% (95% confidence interval: 71.0–78.0). Additionally, RALFT sensitivity was found to be higher for symptomatic vs. asymptomatic individuals and was higher for a symptomatic population within 7 days from symptom onset compared to a population with extended days of symptoms. Viral load was found to be the most important factor for determining SARS-CoV-2 antigen test sensitivity. Other design factors, such as specimen storage and anatomical collection type, also affect the performance of RALFT. RALFT and RT-qPCR testing both achieve high sensitivity when compared to SARS-CoV-2 viral culture.

Keywords: test sensitivity, SARS-CoV-2, diagnostic accuracy, rapid antigen testing, RT-PCR, meta-regression analysis, systematic review and meta-analysis, viral culture

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the highly transmissible viral agent responsible for the development of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19; Carlos et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Based on measurements from specimen swabs, the viral load in infected individuals peaks around the time of symptom onset (approximately 2–3 days following infection; Walsh et al., 2020). This time point coincides with the highest rate of SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility. Transmissibility usually tapers off within 8 days following symptom onset (He et al., 2020). Asymptomatic individuals account for 40–45% of all infections and can transmit the virus for up to 14 days following infection (Oran and Topol, 2020). Therefore, rapid accurate diagnostic testing has been a key component of the response to COVID-19, as identification of SARS-CoV-2-positive individuals facilitates both appropriate treatment and reduced communal spread of the virus (La Marca et al., 2020).

Molecular testing using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) platforms has become the primary diagnostic method for COVID-19 diagnosis (Wang and Taubenberger, 2010; Food and Drug Administration, 2011; Centers for Disease Control, 2020; Tahamtan and Ardebili, 2020). The major advantage of RT-qPCR testing is its high analytical sensitivity (translating to few false-negative results; Giri et al., 2021). However, large-scale clinical laboratory testing requires a dedicated infrastructure and specialized technician training. In addition, due to the specimen transport and processing time, results for standard RT-qPCR can take days to obtain, depending on the catchment area and the demand for testing (Bustin and Nolan, 2020).

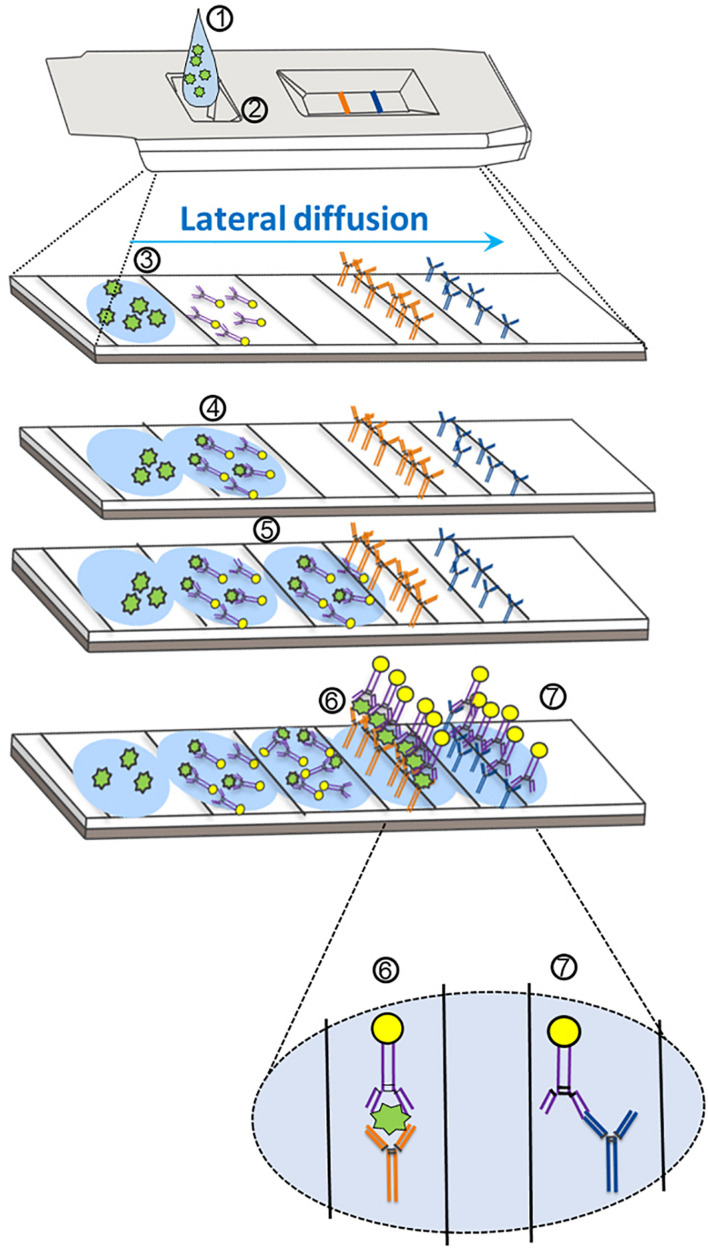

Antigen-based testing involves the application of specific SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (Figure 1) in several formats, including lateral flow immunofluorescent sandwich assays, chromatogenic digital immunoassay, lateral flow immunoassay with visual read, and microfluidic immunofluorescence assays (Rezaei et al., 2020). Antigen testing for SARS-CoV-2 can be utilized either in conjunction with RT-qPCR as a first-line screening test or in decentralized health care settings in which RT-qPCR testing may not be conducive for rapid result turnaround (Rezaei et al., 2020). Rapid antigen-based lateral flow testing for SARS-CoV-2, as with influenza, has been implemented globally to achieve rapid accurate results for COVID-19 diagnosis (Peeling et al., 2021). Although the majority of antigen-based tests share a common mechanism for detection of SARS-CoV-2 protein, the reported sensitivities of both Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Emergency Use Authorization (EUA)-approved and non-EUA-approved antigen-based tests have varied greatly in the literature (Brümmer et al., 2021). Multiple meta-analyses and systematic reviews have reported large inter-study heterogeneity related to SARS-CoV-2 antigen-based testing (Dinnes et al., 2020; COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group Rapid Evidence Report, 2020; Brümmer et al., 2021). Although reliable antigen test performance coincides with a high specimen viral load (Brümmer et al., 2021), study heterogeneity could impact our conclusions about antigen test performance. Factors that could affect overall antigen test performance include analytical sensitivity (i.e., antibody/antigen binding affinity) of the assay, which likely varies for tests across manufacturers (Mina et al., 2020), biases occurring from the study design (e.g., blinding, test order, etc.), the study population [e.g., symptomatic vs. asymptomatic, days from symptom onset (DSO), etc.], the anatomical collection site (e.g., nasopharyngeal vs. anterior nares), and specimen storage conditions (Lijmer et al., 1999; Griffith et al., 2020; Accorsi et al., 2021).

FIGURE 1.

Mechanism of action for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) antigen detection through lateral flow assay design. (1) The specimen analyte, containing SARS-CoV-2 antigen suspended in assay buffer, is deposited in the sample well (at 2). (3) The analyte (containing antigen; in green) is absorbed into the sample pad and begins to diffuse across the reaction chamber into the conjugate pad. (4) The analyte comes into proximity of a SARS-CoV-2-specific antigen antibody that is conjugated to a tag (usually consisting of gold, latex, or a fluorophore). (5) The antigen–antibody complex migrates via diffusion across the nitrocellulose membrane. (6) The SARS-CoV-2 antigen–antibody complex comes into proximity of a second SARS-CoV-2 antigen antibody (different epitope) that is covalently bound to the device pad, and an antibody–antigen–antibody complex forms, resulting in the test line. Further diffusion of excess SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (unbound to antigen) results in association of a second covalently bound antibody that is specific for the first SARS-CoV-2 antibody. (7) An antibody–antibody complex forms resulting in the control line.

As others have noted previously, a wide range of reported sensitivities has been documented for rapid antigen testing (Dinnes et al., 2020; Brümmer et al., 2021). The main objective of this meta-analysis was to explore possible causes of the high degree of heterogeneity of assay sensitivity estimates across different studies. Data were summarized and analyzed from over 80 articles and manufacturer instructions for use (IFU) to provide results on sensitivity for SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing from more than 25 individual assays.

Materials and Methods

The methods for conducting research and reporting results for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which are outlined by the Cochrane Collaboration Diagnostic Test Accuracy Working Group and by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, were employed for this study (Gatsonis and Paliwal, 2006; Leeflang, 2014; Page et al., 2020). This study protocol was registered with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews in 2021 (PROSPERO CRD42021240421; Booth et al., 2011).

The PICO (Participants, Intervention, Comparator, and Outcomes) of this meta-analysis was as follows: Participants were individuals undergoing SARS-CoV-2 testing in a healthcare setting (at least eight cases); Intervention (primary) was the index test consisting of a SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection platform utilizing immunobiological mechanisms, such as a sandwich ELISA, combined with spatial resolution (e.g., immunochromatographic assay); Intervention (secondary) was testing for SARS-CoV-2 using antigen and RT-qPCR testing (indices 1 and 2); Comparator (primary) was RT-qPCR as the reference test for detecting SARS-CoV-2 genomic RNA (any target gene); Comparator (secondary) was SARS-CoV-2 viral culture as the reference method for identifying specimens with infectious viral particles; and Outcome was the determination of antigen test sensitivity across independent variables.

Search and Selection Criteria

Eligible studies/sources included diagnostic studies of any design type (i.e., retrospective, prospective, randomized, blinded, and non-blinded) that specifically involved the detection of SARS-CoV-2. The primary outcome was sensitivity for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in a healthcare setting by rapid antigen testing as compared with RT-qPCR. Both MEDLINE and MedRxiv electronic databases were searched across dates ranging from January 1, 2020, to February 1, 2021, with the following search terms: (1) [(Antigen test and (sars-cov-2 OR COVID-19)] OR ((antigen[title/abstract] AND test) OR (Antigen[title/abstract] and assay)) AND (SARS-CoV-2[title/abstract] OR COVID-19[title/abstract])) and (2) ‘‘SARS-CoV-2 and antigen test or COVID-19 and antigen test.’’ In addition, a search was performed on the FDA database1 for all EUA SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests. All retrieved sources were assessed for relevance using predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria consisted of the following: (1) SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic target; (2) Sensitivity as a performance outcome; (3) Compares antigen testing performance with RT-qPCR as reference; (4) Population includes symptomatic and/or asymptomatic participants; (5) Human study; (6) English language; and (7) Any region, country, or state. Secondary inclusion subcriteria for analyses included the following: (S1) Index performance results that were stratified by viral load or by RT-qPCR (reference) cycle threshold (Ct); (S2) Delineated specimens for reference and index testing between symptomatic and asymptomatic participants; (S3) Delineated the anatomical site for specimen collection prior to reference and index testing; (S4) Delineated whether the specimen was frozen prior to reference testing; (S5) Specified whether the specimen was frozen prior to index testing; (S6) Analytical limit of detection (LOD) information was available for the reference assay; and (S7) The index test manufacturer information was available. The exclusion criteria included the following: (1) Article/source from a non-credible source; (2) Article/source contains an unclear or indistinct research question; (3) Does not contain performance data specific to SARS-CoV-2; (4) Does not identify or does not involve standard upper respiratory SARS-CoV-2 specimens (e.g., contains other specimen types such as serum or saliva); (5) Contains no RT-qPCR reference results for comparison; (6) Data were collected in an unethical manner; (7) The index test involves a mechanism other than SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection involving a lateral flow (or similar) design; (8) Data not conducive for extraction required for analysis; and (9) No data regarding true-positive and false-negative rates for the index test relative to the reference test. Additional secondary exclusion criteria included (S1) Article/source not in the English language; and (S2) Study did not involve humans.

Full-text reviews of the articles that passed initial screening were performed to identify sources that met inclusion/exclusion criteria involving study methodologies, specimen collection, SARS-CoV-2 test details, data type (sensitivity, specificity values, etc.) and format [raw data, only point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) included, etc.]. The information was then entered into data extraction tables to document study characteristics and to record raw data with calculated point estimates and 95% CIs. A modified Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used to evaluate the risk of bias (individual study quality; Wells et al., 2011), which included the following bias domains: detection (measurement of test result), reporting (failure to adequately control confounding, failure to measure all known prognostic factors), and spectrum (eligibility criteria, forming the cohort, and selection of participants). Risk of bias summary assessments for individual studies were categorized as “high,” “moderate,” or “low.” The overall quality of evidence for the risk estimate outcomes (all included studies) was obtained using a modified Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (Schunemann et al., 2013) methodology for observational diagnostic studies.

The seven domains used to ascertain the overall study quality and strength across the six independent variables were (1) Confounder effect; (2) Consistency; (3) Directness; (4) Magnitude of effect; (5) Precision; (6) Publication bias; and (7) Risk of bias (ascertained from individual studies). Study subgroups were considered high quality when ≥4 of seven domains received a green rating, with no red ratings, and <3 unclear ratings; otherwise, it was considered moderate quality. Study subgroups were considered moderate quality when three domains were green with <3 red domains; or when two domains were green and <3 domains were red with <4 domains unclear; or when one domain was green with <2 red domains and <3 domains were unclear; or when no domains were green, no domains were red, and <2 domains were unclear. Any other combination of ratings resulted in a classification of quality as low.

Subgroup meta-analysis was performed for the following factors: (1) viral load with fixed cutoff values; (2) symptomatic vs. asymptomatic; (3) ≤7 DSO vs. any DSO; (4) anatomical collection type for specimens used for both index and reference testing (anterior nares/mid-turbinate vs. nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal); (5) specimen storage conditions (fresh vs. frozen); (6) analytical sensitivity of the reference RT-qPCR test [detection cutoff < 500 genomic copies/ml (cpm) vs. ≥500 cpm]; and (7) assay manufacturer.

Data Analysis

Data extraction was accomplished by two reviewers/authors with any discrepancies adjudicated by a third reviewer/author. An independent author performed all statistical methods. All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.0.2) (R Core Team, 2020) along with the meta (Balduzzi et al., 2019) and metaphor (Viechtbauer, 2010) packages. For each study, the sensitivity of the index test along with 95% Clopper–Pearson CI was calculated. Logit-transformed sensitivity values were combined to obtain random effect estimates of overall sensitivity. The same method was applied to subgroup meta-analyses; subgroups were defined by disease status, reference and test collection type, reference and test storage (fresh/frozen), study spectrum bias, reference analytical sensitivity (high and low), and manufacturer. Q-tests for heterogeneity based on random-effects models with common within-group variability were used to evaluate statistical differences between subgroups (univariate analysis). Moderators with significant heterogeneity in the subgroup analysis were included in a meta-regression mixed-effects model. Forest plots were generated for all subgroup analyses; a funnel plot of all logit-transformed sensitivities was generated without taking into account study characteristics, and another funnel plot of residual values was generated after fitting the meta-regression model. Separately, for articles where viral load information was available, subgroup meta-analysis by viral load (either measured by RT-PCR Ct of 25 or 30 or a viral cpm of 1 × 105) and symptomatic status was performed. The minimum number of studies required for synthesis is n = 3.

Results

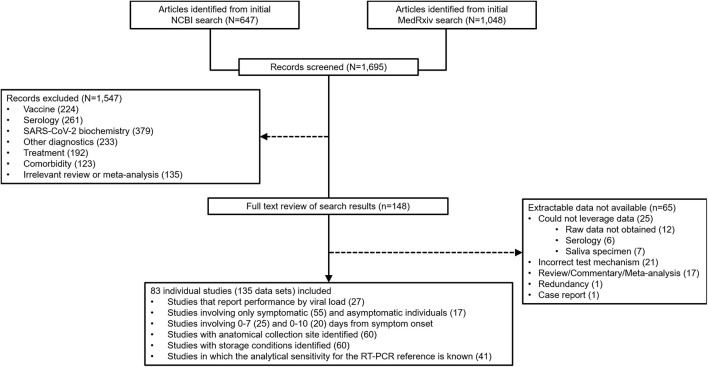

At the outset, 1,695 sources were identified during the database search (Figure 2). From that group of candidate sources, screening was performed by title and abstract, and the potential pool of articles was reduced, and 148 underwent full-text review for data extraction. 83 articles/sources of the 148 were chosen for meta-analysis (Table 1) based upon further exclusion criteria (see section “Materials and Methods”). Note that a list of excluded sources with their specific exclusion criteria is available upon request from the authors. Of the 83 source studies, 76 (91.6%) involved a cross-sectional study design. Data from 12 of the sources were from validation studies as part of EUA from the FDA and can be found in each, respective, manufacturer IFU. 22 of the studies were conducted in the United States, nine in Spain, seven each from Germany and Japan, six from Italy, four from China, three each from France, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, and two each from Belgium and Chile; the rest of the countries represented in this study had only one. 135 individual data sets were utilized in total from the 83 articles/sources; 30 articles provided more than one data set. The overall combined number of specimens from participants, across all 83 studies, was 53,689; the overall total number of RT-qPCR reference positive results for estimating sensitivity from all 135 data sets was 13,260.

FIGURE 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for reconciliation of articles/sources included in this study.

TABLE 1.

Information characterizing data sources involving SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing for analyses described in this report.

| RFID | Source RFID | Country | Total N | Reference (+) | Index (Antigen) test | Index manufacturer | Ref. (RT-PCR) test | Ref. manufacturer |

| 1 | Abdelrazik et al., 2020 | Egypt | 310 | 190 | BIOCREDIT COVID-19 Antigen Test | RapiGen Inc., South Korea | Not available | Not available |

| 2 | Abdulrahman et al., 2020 | Bahrain | 4,183 | 734 | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | TaqPathTM COVID-19 Multiplex Kit | Thermo Fisher, United States |

| 3 | Albert et al., 2020 | Spain | 412 | 56 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | TaqPathTM COVID-19 Multiplex Kit | Thermo Fisher, United States |

| 4 (sx/asx) | Alemany et al., 2021 | Spain | 1,406 | 954 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Not available | Not available |

| 5 | Aoki et al., 2020 | Japan | 510 | 26 | Lumipulse® SARSCoV-2 Ag kit | Fujirebio Inc., Tokyo, Japan | TaqMan® Fast Virus 1-Step | Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States |

| 6 | Aoki et al., 2021 | Japan | 129 | 66 | Espline® SARS-CoV-2 | Fujirebio Inc., Japan | TaqMan® Fast Virus 1-Step | Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States |

| 7 | Beck et al., 2021 | United States | 346 | 63 | Quidel Sofia® SARS FIA | Quidel, San Diego, CA, United States | Cepheid Xpert® Xpress | Cepheid, United States |

| 8a | Berger et al., 2020 | Switzerland | 535 | 126 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 8b | 529 | 193 | STANDARD QTM COVID-19 Ag Test | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | ||

| 9 (sx/asx) | Bulilete et al., 2020 | Spain | 1,369 | 155 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | TaqPath COVID-19 Multiplex Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States |

| 10 | Cerutti et al., 2020 | Italy | 330 | 107 | STANDARD QTM COVID-19 Ag Test | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Seegene Allplex® 2019 n-CoV Assay | Seegene Inc., South Korea |

| 11 | Chaimayo et al., 2020 | Thailand | 454 | 63 | STANDARD QTM COVID-19 Ag Test | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Seegene Allplex® 2019 n-CoV Assay | Seegene Inc., South Korea |

| 12 | Ciotti et al., 2021 | Italy | 50 | 43 | COVID-19 Ag Respi-Strip | Coris BioConcept, Belgium | Seegene Allplex® 2019 n-CoV Assay | Seegene Inc., South Korea |

| 13 | Colavita et al., 2020 | Italy | 941 | 208 | STANDARD FTM COVID-19 Ag FIA | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 14 | Courtellemont et al., 2021 | France | 248 | 125 | COVID-VIRO® | AAZ, France | TaqPath COVID-19 Multiplex Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States |

| 15 | Diao et al., 2020 | China | 251 | 205 | SARS-CoV-2 AntigenFIC Assay (in house) | In-house | TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Kit | Da An Gene, China |

| 16 | Drain et al., 2020 | United States; United Kingdom | 512 | 186 | LumiraDxTM SARS-CoV-2 Ag Test | LumiraDx, United Kingdom | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 17a (sx/asx) | Drevinek et al., 2020 | Czech R. | 591 | 596 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Seegene Allplex® 2019 n-CoV Assay | Seegene Inc., South Korea |

| 17b (sx/asx) | STANDARD FTM COVID-19 Ag FIA | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Seegene Allplex® 2019 n-CoV Assay | Seegene Inc., South Korea | ||||

| 18a (sx/asx) | Favresse et al., 2021 | Belgium | 188 | 101 | Biotical SARS-CoV-2 Ag card | Biotical Health, SLU, Spain | LightMix® | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 18b (sx/asx) | 101 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | LightMix® | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | |||

| 18c (sx/asx) | 100 | Coronavirus Ag Rapid Test Cassette | Healgen Scientific, LLC, United States | LightMix® | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | |||

| 18d (sx/asx) | 100 | Roche SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Test | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | LightMix® | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | |||

| 18e (sx/asx) | 101 | VITROS SARS-CoV-2 Antigen test | Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, United States | LightMix® | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | |||

| 19 (sx/asx) | Fenollar et al., 2021 | France | 341 | 208 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Vita PCR SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Credo Diagnostics, Singapore |

| 20 | Gremmels et al., 2021 | Netherlands; Aruba | 1,369 | 206 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Seegene Allplex® 2019 n-CoV Assay | Seegene Inc., South Korea |

| 21 | Hirotsu et al., 2020 | Japan | 313 | 61 | Lumipulse® SARS-CoV-2 Ag kit | Fujirebio Inc., Japan | TaqMan Fast Virus 1-Step Master Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States |

| 22 | Hirotsu et al., 2021 | Japan | 27 | 23 | Lumipulse® SARS-CoV-2 Ag kit | Fujirebio Inc., Japan | Not available | Not available |

| 23 | Hoehl et al., 2020 | Germany | 711 | 9 | RIDA® QUICK SARS-CoV-2 Antigen test | R-Biopharm, Darmstadt, Germany | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 24 | Houston et al., 2021 | United Kingdom | 728 | 284 | Innova SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Rapid Test | Lotus Global Company, United Kingdom | Not available | Not available |

| 25a | Jääskeläinen et al., 2021 | Finland | 188 | 152 | Quidel Sofia® SARS FIA | Quidel, San Diego, CA | Not available | Not available |

| 25b | 189 | 162 | STANDARD QTM COVID-19 Ag Test | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Not available | Not available | ||

| 25c | 190 | 156 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Not available | Not available | ||

| 26 (sx/asx) | Jakobsen et al., 2021a | Denmark | 196 | 148 | STANDARD QTM COVID-19 Ag Test | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Luna One-step RT-qPCR kit | New England Biolabs, United States |

| 27 (sx/asx) | James et al., 2021 | United States | 2,339 | 156 | BinaxNOWTM COVID-19 Ag Card test kit | Abbott Diagnostics Inc., United States | PerkinElmer SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR | PerkinElmer, Inc., United States |

| 28 | Kashiwagi et al., 2020 | Japan | 16 | 26 | ESPLINE® SARS-CoV-2 test | Fujirebio Inc., Japan | Not available | Not available |

| 29a | Kohmer et al., 2021 | Germany | 100 | 76 | RIDA® QUICK SARS-CoV-2 Antigen test | R-Biopharm, Darmstadt, Germany | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 29b | Roche SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Test | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | Roche cobas SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | ||||

| 29c | NADAL® COVID-19 Ag Test | Nal von Minden GmbH, Germany | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | ||||

| 29d | LumiraDxTM SARS-CoV-2 Ag Test | LumiraDx, United Kingdom | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | ||||

| 30a | Krüger et al., 2020 | Germany; United Kingdom | 417 | 11 | COVID-19 Ag Respi-Strip | Coris BioConcept, Belgium | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 30b | 727 | 18 | BIOEASYTM 2019-nCoV Ag Rapid Test | BIOEASY Technology, China | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | ||

| 30c | 1,267 | 50 | STANDARD QTM COVID-19 Ag Test | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | ||

| 31 | Krüttgen et al., 2021 | Germany | 150 | 77 | Roche SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Test | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | Real Star SARS-CoV-2 RT PCR Kit | Altona, Germany |

| 32 | Lambert-Niclot et al., 2020 | France | 138 | 96 | COVID-19 Ag Respi-Strip | Coris BioConcept, Belgium | Multiple tests used | Multiple manufacturers used |

| 33 | Linares et al., 2020 | Spain | 141 | 90 | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Seegene Allplex® 2019 n-CoV Assay | Seegene Inc., South Korea |

| 34 | Lindner et al., 2020 | Germany | 287 | 41 | STANDARD QTM COVID-19 Ag Test | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 35 | Lindner et al., 2021 | Germany | 146 | 82 | STANDARD QTM COVID-19 Ag Test | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 36 | Liotti et al., 2020 | Italy | 359 | 107 | STANDARD FTM COVID-19 Ag FIA | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Multiple tests used | Multiple manufacturers used |

| 37 | Liu et al., 2021 | China | 99 | 17 | In-house assay | Not applicable | Not available | Not available |

| 38a | Mak et al., 2020 | China | 140 | 143 | COVID-19 Ag Respi-Strip | Coris BioConcept, Belgium | Not available | Not available |

| 38b | NADAL® COVID-19 Ag Test | Nal von Minden GmbH, Germany | Not available | Not available | ||||

| 38c | STANDARD QTM COVID-19 Ag Test | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Not available | Not available | ||||

| 39 | Mak et al., 2021 | China | 105 | 108 | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Not available | Not available |

| 40 (sx/asx) | Masiá et al., 2020 | Spain | 913 | 40 | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 41 | Menchinelli et al., 2021 | Italy | 594 | 196 | Lumipulse® SARS-CoV-2 Ag kit | Fujirebio Inc., Japan | Seegene Allplex® 2019 n-CoV Assay | Seegene Inc., South Korea |

| 42 | Merino-Amador et al., 2020 | Spain | 958 | 361 | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Not available | Not available |

| 43 | Möckel et al., 2021 | Spain | 473 | 115 | Roche SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Test | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 44 | Nalumansi et al., 2020 | Uganda | 262 | 94 | STANDARD QTM COVID-19 Ag Test | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Not available | Not available |

| 45 | Ngo Nsoga et al., 2021 | Switzerland | 402 | 169 | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 46 | Okoye et al., 2021 | United States | 2,638 | 46 | BinaxNOWTM COVID-19 Ag Card test kit | Abbott Diagnostics, Inc., United States | TaqPath COVID-19 Multiplex Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States |

| 47a | Osterman et al., 2021 | Germany | 445 | 192 | STANDARD FTM COVID-19 Ag FIA | SD Biosensor, South Korea | RealAccurate® Quadruplex SARS CoV-2 PCR Kit | PathoFinder®, Netherlands |

| 47b | 259 | Roche SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Test | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland | RealAccurate® Quadruplex SARS CoV-2 PCR Kit | PathoFinder®, Netherlands | |||

| 48 | Pekosz et al., 2021 a | United States | 251 | 38 | BD VeritorTM SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen test | Becton, Dickinson and Company, United States | Lyra® RT-PCR Assay | Quidel Corporation, United States |

| 49a | Peto, 2021 | United Kingdom | 940 | 198 | Innova SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Rapid Test | Lotus Global Company, United Kingdom | Not available | Not available |

| 49b | 100 | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Not available | Not available | |||

| 50 (sx/asx) | Pilarowski et al., 2020a | United States | 878 | 131 | BinaxNOWTM COVID-19 Ag Card test kit | Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough, Inc., United States | Not available | Not available |

| 51 (sx/asx) | Pilarowski et al., 2020b | United States | 3,302 | 134 | BinaxNOWTM COVID-19 Ag Card test kit | Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough, Inc., United States | Renegade XPTM | RenegadeBio, United States |

| 52 | Pollock et al., 2021b | United States | 226 | 139 | S-PLEX® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Meso Scale Discovery, United States | Not available | Not available |

| 53 (sx/asx) | Pollock et al., 2021a | United States | 2,308 | 295 | BinaxNOWTM COVID-19 Ag Card test kit | Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough, Inc., United States | CRSP SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR | Harvard University, United States |

| 54 | Porte et al., 2020 | Chile | 127 | 83 | BIOEASYTM 2019-nCoV Ag Rapid Test | BIOEASY Technology, China | Genesig® Real-Time PCR assay | Primerdesign Ltd., United Kingdom |

| 55 (sx/asx) | Pray et al., 2021 | United States | 1,098 | 59 | Quidel Sofia® SARS FIA | Quidel, San Diego, CA | Multiple tests used | Multiple manufacturers used |

| 56 (sx/asx) | Prince-Guerra et al., 2021 | United States | 3,419 | 226 | BinaxNOWTM COVID-19 Ag Card test kit | Abbott Diagnostics, Inc., United States | Multiple tests used | Multiple manufacturers used |

| 57 | Rastawicki et al., 2021 | Poland | 167 | 38 | PCL COVID−19 Ag rapid immunoassay | PLC, South Korea | Multiple tests used | Multiple manufacturers used |

| 58a | Schwob et al., 2020 | Switzerland | 928 | 113 | STANDARD QTM COVID-19 Ag Test | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Not available | Not available |

| 58b | 123 | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Not available | Not available | |||

| 58c | 139 | COVID-VIRO® | AAZ, France | Not available | Not available | |||

| 59 (sx/asx) | Scohy et al., 2020 | Belgium | 148 | 93 | COVID-19 Ag Respi-Strip | Coris BioConcept, Belgium | Genesig® Real-Time PCR assay | Primerdesign Ltd., United Kingdom |

| 60 | Stokes et al., 2021 | Canada | 145 | 140 | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Not available | Not available |

| 61 | Strömer et al., 2020 | Germany | 134 | 126 | NADAL® COVID-19 Ag Test | Nal von Minden GmbH, Germany | Not available | Not available |

| 62 (sx/asx) | Takeuchi et al., 2021 | Japan | 771 | 74 | Quick NaviTM-COVID 19 Ag Rapid Test | Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Japan | Not available | Not available |

| 63 | Toptan et al., 2020 | Germany | 67 | 61 | RIDA® QUICK SARS-CoV-2 Antigen test | R-Biopharm, Darmstadt, Germany | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 64 | Torres et al., 2021 | Spain | 634 | 80 | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | TaqPath COVID-19 Multiplex Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States |

| 65 (sx/asx) | Turcato et al., 2020 | Italy | 3,410 | 227 | STANDARD QTM COVID-19 Ag Test | SD Biosensor, South Korea | Not available | Not available |

| 66 | Van der Moeren et al., 2020 | Netherlands | 352 | 125 | BD VeritorTM SARS−CoV−2 Rapid Antigen test | Becton, Dickinson and Company, United States | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 67 | Villaverde et al., 2021 | Spain | 1,620 | 79 | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Jena, Germany | Abbott Diagnostic GmbH, Germany | Not available | Not available |

| 68a | Weitzel et al., 2020 | Chile | 111 | 81 | Biocredit COVID-19 Antigen Test | RapiGen Inc., South Korea | Genesig® Real-Time PCR assay | Primerdesign Ltd., United Kingdom |

| 68b | 80 | Huaketai New Coronavirus | Savant Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China | Genesig® Real-Time PCR assay | Primerdesign Ltd., United Kingdom | |||

| 68c | 82 | BIOEASY 2019-nCoV Ag Rapid Test | BIOEASYTM Technology, China | Genesig® Real-Time PCR assay | Primerdesign Ltd., United Kingdom | |||

| 69 | Yamamoto et al., 2021 | Japan | 608 | 130 | In-house assay | Not applicable | Not available | Not available |

| 70 | Young et al., 2020 b | United States | 226 | 32 | BD VeritorTM SARS−CoV−2 Rapid Antigen test | Becton, Dickinson and Company, United States | Lyra® RT-PCR Assay | Quidel Corporation, United States |

| 71 | Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough Inc, 2020a | United States | 460 | 120 | BinaxNOWTM COVID-19 Ag Card test kit | Abbott Diagnostics, Inc., United States | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 72 | Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough Inc, 2020b | United States | 53 | 27 | BinaxNOWTM COVID-19 Ag Card test kit | Abbott Diagnostics, Inc., United States | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 73 | Access Bio, 2020 | United States | 126 | 46 | CareStartTM COVID-19 Rapid Test | Access Bio, Inc., United States | Not available | Not available |

| 74 | Ellume Limited, 2020 | United States | 198 | 40 | Ellume COVID-19 Home Test | Ellume Limited, United States | Not available | Not available |

| 75 | Luminostics Inc, 2020 | United States | 166 | 35 | Clip COVID-Rapid Antigen Test | Luminostics, Inc., United States | Not available | Not available |

| 76 | LumiraDx UK Ltd, 2020 | United Kingdom | 257 | 86 | LumiraDxTM SARS-CoV-2 Ag Test | LumiraDx, United Kingdom | Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland |

| 77 | Quidel Corporation, 2020a | United States | 156 | 61 | QuickVue® SARS Antigen Test | Quidel Corporation, United States | Not available | Not available |

| 78 | Celltrion, 2020 | United States | 72 | 39 | SampinuteTM COVID-19 Antigen MIA | Celltrion, United States | Not available | Not available |

| 79 | Quidel Corporation, 2020b | United States | 209 | 33 | Quidel Sofia® SARS FIA | Quidel, United States | Lyra® RT-PCR Assay | Quidel Corporation, United States |

| 80 | Quidel Corporation, 2020c | United States | 165 | 45 | Quidel Sofia® SARS FIA | Quidel, United States | Lyra® RT-PCR Assay | Quidel Corporation, United States |

| 81 | BD, 2020a | United States | 226 | 32 | BD VeritorTM SARS−CoV−2 Rapid Antigen test | Becton, Dickinson and Company, United States | LyraTM RT-PCR Assay | Quidel Corporation, United States |

| 82 | BD, 2020b | EU | 251 | 38 | BD VeritorTM SARS−CoV−2 Rapid Antigen test | Becton, Dickinson and Company, United States | Lyra® RT-PCR Assay | Quidel Corporation, United States |

| 83 | BD, 2020c | United States | 115 | 61 | BD VeritorTM SARS−CoV−2 Rapid Antigen test | Becton, Dickinson and Company, United States | Lyra® RT-PCR Assay | Quidel Corporation, United States |

sx/ask, symptomatic/asymptomatic; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2.

EU, European Union; IFU, manufacturer instructions for use; RFID, reference ID; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

aPekosz 2021 was only used as a data source for sensitivity analysis with Ct score stratification and for sensitivity analysis using cell culture as a reference.

bYoung 2020 was only used as a data source for sensitivity analysis for Ct score stratification.

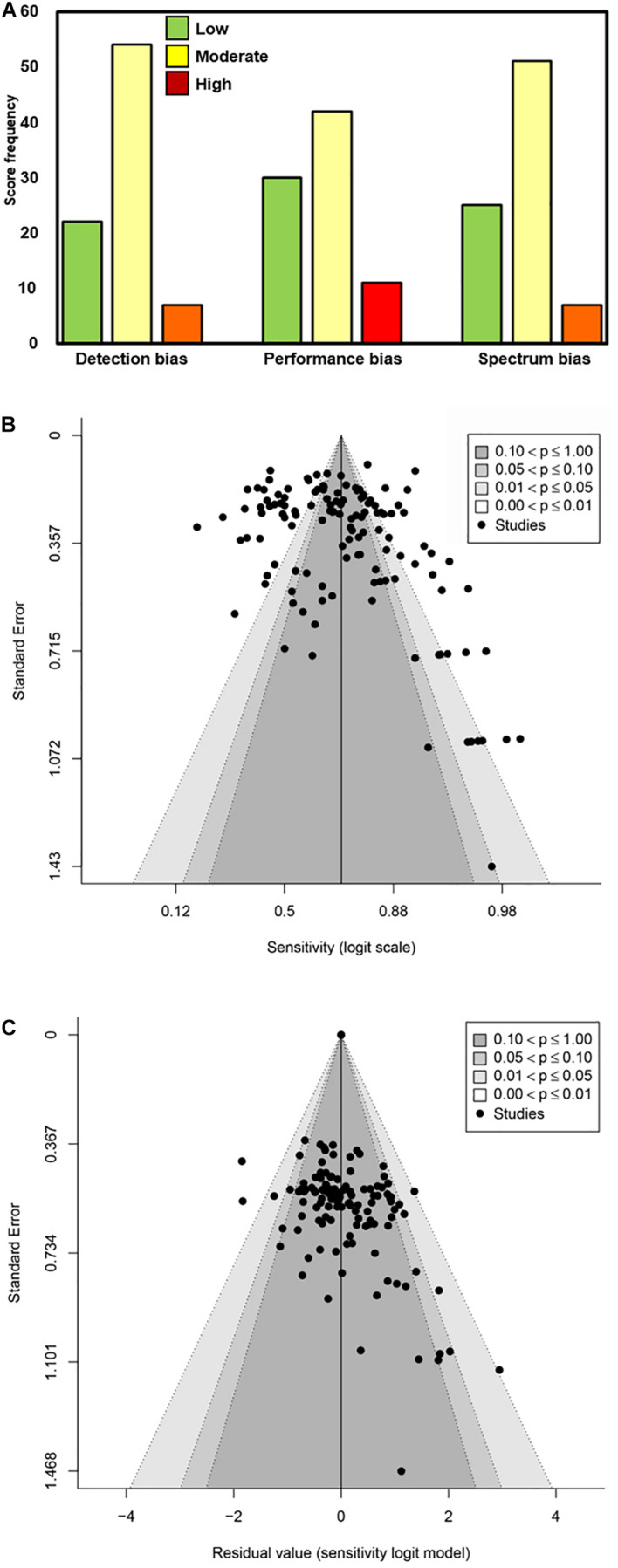

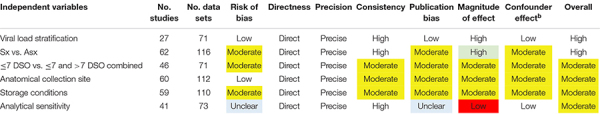

A modified Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used to rate biases of detection, performance, and participant selection (spectrum bias; Figure 3). The majority of studies were associated with low or moderate bias of detection (89.1%; 74/83), bias of performance (85.5%; 71/83), and spectrum bias (87.9%; 73/83). All included articles/sources had acceptable reference standards (that was an inclusion criterion), appropriate delay between index and reference testing, and no incorporation bias between the index and reference tests. The two most common weaknesses associated with study design for the included articles/sources were improper blinding and spectrum bias associated with participant enrollment (Lijmer et al., 1999). Across the six primary factors (viral load, symptomatic vs. asymptomatic, DSO, anatomical collection site, storage condition, and analytical sensitivity of the reference RT-qPCR assay) analyzed here, the quality of evidence was largely a mixture of high and moderate (Table 2).

FIGURE 3.

Determination of bias associated with the source articles/documents included in this meta-analysis. (A) Scoring as Low, Moderate, and High was performed for Detection bias, Performance bias, and Spectrum bias associated with each data source included. The frequency of the scores is plotted along the Y-axis. (B,C) Funnel plots of logit-transformed sensitivity in a model without any moderators (B) and with moderators included (C).

TABLE 2.

Overall quality of evidence for outcomesa (modified GRADE; Schunemann et al., 2013).

|

GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; Sx, symptomatic; Asx, asymptomatic; DSO, days from symptom onset.

aEach independent variable (e.g., Viral Load Stratification), was rated according to seven quality domains, with an overall quality rating in the last column. The overall quality rating was established based on the overall number of green (indicating high quality), yellow (indicating moderate quality), and red (indicating low quality) domains; blue shading indicates that the quality rating for that domain was unclear. For example, low Publication Bias and high Consistency are both rated as high quality, whereas a low Magnitude of Effect resulted in a low quality rating. Please see the Methods and Materials section for further description of the overall quality ranking.

bCounfounder effect characterizes the degree to which all plausible confounders would tend to increase confidence in the estimated effect.

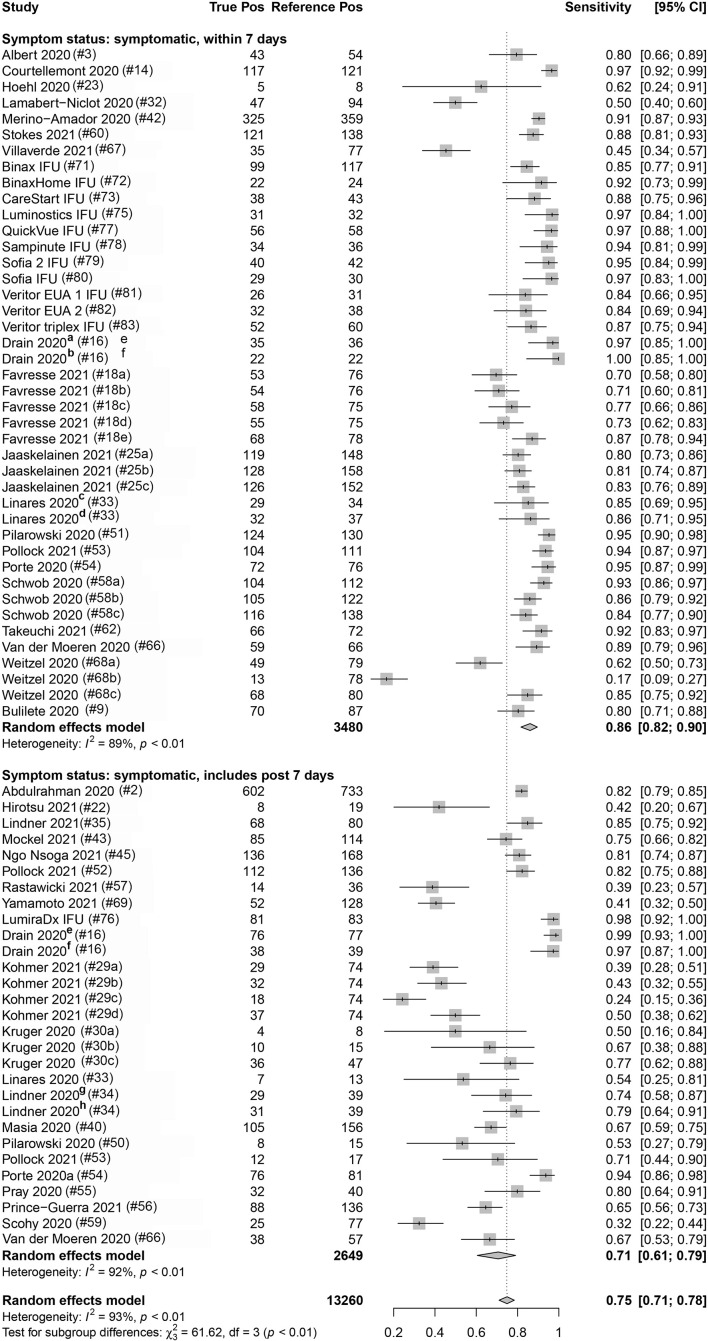

Eighty-three percent (112/135) and 16.3% (22/135) of the data sets provided data from COVID-19 symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, respectively. The index test sensitivity point estimate (with 95% CI) for the symptomatic group [80.1% (95% CI: 76.0, 83.7); reference positive n = 9,351] was significantly greater (p-value < 0.001) than that for index test sensitivity for the asymptomatic group [54.8% (95% CI: 48.6, 60.8); reference positive n = 1,723]. Of the 112 symptomatic data sets, 37.5% (42) included participants that were ≤7 DSO, and 25.9% (29) included individuals that were a mix of ≤7 DSO and >7 DSO; 36.6% (41) had a DSO status that was unknown. A significant difference (p-value = 0.001) was observed when studies reporting on symptomatic individuals were subgrouped by DSO; a sensitivity point estimate of 86.2% (95% CI: 81.8, 89.7) for the ≤7 DSO subgroup (reference positive n = 3,480) compared to 70.8% (95% CI: 60.7, 79.2) for the group including both ≤7 DSO and >7 DSO (reference positive n = 2,649; Figure 4 and Table 3).

FIGURE 4.

Forest plots containing calculated sensitivity values for index [severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) antigen test] testing compared to reference [SARS-CoV-2 quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR assay)] test. Data are stratified by days from symptom onset.

TABLE 3.

Diagnostic performance (sensitivity) for antigen testing, with RT-qPCR as reference, stratified by different population and experimental factors.

| Variable category | Variable group | No. data sets | Total reference (+) | Sensitivity (%) | 95% CI | Univariatea | Multivariate |

| RT-qPCR Ct value | ≥105 cpm | 18 | 1,278 | 93.8 | [87.1, 97.1] | p < 0.001 | n/a |

| <105cpm | 18 | 781 | 28.6 | [16.2, 45.3] | |||

| Ct value ≤ 25 | 16 | 897 | 96.4 | [94.3, 97.7] | p < 0.001 | n/a | |

| Ct value > 25 | 16 | 673 | 44.9 | [33.0, 57.4] | |||

| Ct value ≤ 30 | 37 | 2,536 | 89.5 | [85.3, 92.5] | p < 0.001 | n/a | |

| Ct value > 30 | 37 | 679 | 18.7 | [12.9, 26.3] | |||

| Symptom status | Symptomatic | 95 | 9,351 | 80.1 | [76.0, 83.7] | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| Asymptomatic | 23 | 1,723 | 54.8 | [48.6, 60.8] | |||

| Missing information | 15 | 2,186 | 65.3 | [56.4, 73.3] | |||

| ≤7 DSO | 42 | 3,480 | 86.2 | [81.8, 89.7] | |||

| ≤7 DSO + > 7 DSO | 29 | 2,649 | 70.8 | [60.7, 79.2] | |||

| Anatomical site (ref.) | Nasal swab | 25 | 1,654 | 82.7 | [74.7, 88.5] | p = 0.037 | p = 0.023 |

| NPS | 97 | 10,607 | 73.1 | [68.5, 77.2] | |||

| Missing | 11 | 999 | 71.6 | [55.7, 83.6] | |||

| Specimens storage (index) | Fresh | 101 | 9,666 | 75.3 | [70.8, 79.3] | p = 0.375 | |

| Frozen | 23 | 3,307 | 70.9 | [61.0, 79.1] | |||

| Missing | 9 | 287 | 81.5 | [69.3, 89.5] | |||

| Analytical sensitivity (Ref.) | High (≤500 cpm) | 53 | 4,531 | 74.2 | [66.9, 80.4] | p = 0.650 | |

| Low (>500 cpm) | 22 | 2,582 | 76.8 | [67.2, 84.2] | |||

| Missing | 58 | 6,147 | 75.0 | [69.8, 79.5] | |||

| Study spectrum bias | High/Moderate | 52 | 5,524 | 81.4 | [75.5, 86.1] | p = 0.004 | p = 0.757 |

| Low | 81 | 5,871 | 70.4 | [65.4, 74.9] | |||

| All sources combined | n/a | 133 | 13,260 | 75.0 | [71.0, 78.0] |

CI, confidence interval; DSO, days from symptom onset; Ct, cycle threshold; cpm, genomic copies/ml; NPS, nasopharyngeal swab; and RT-qPCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

aQ-test p-value for heterogeneity among subgroups calculated from random-effects meta-analysis.

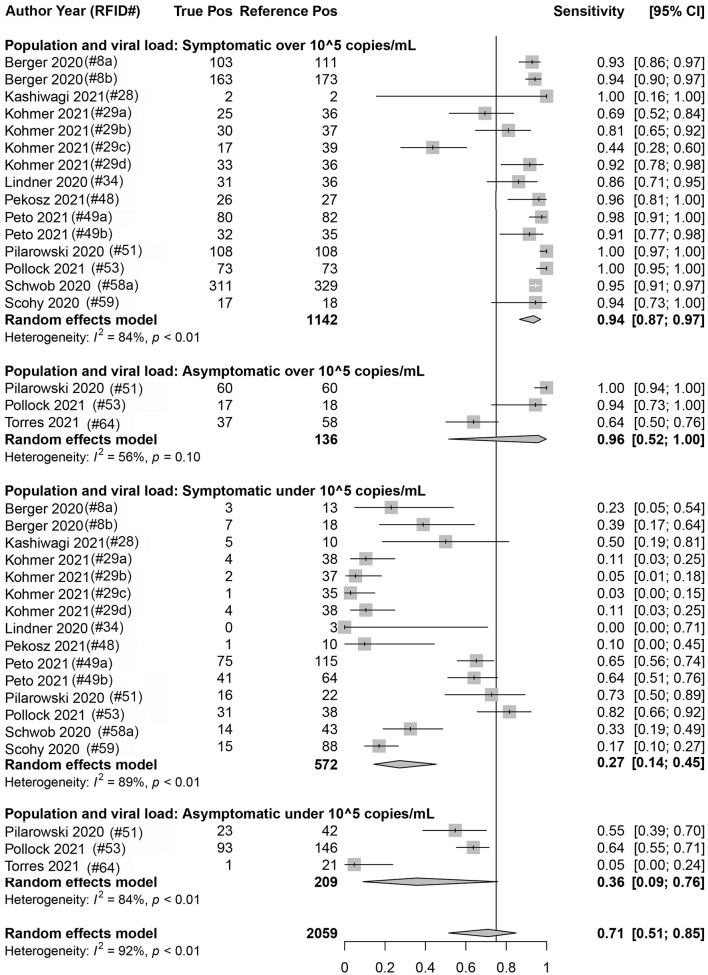

Eighteen data sets reported true positives and false negatives by viral load in the specimen; 37 and 16 data sets reported values by a Ct value of 30 and 25, respectively, for the RT-qPCR (reference) assay. When data were stratified by ≥1 × 105 cpm (n = 1,278 reference positive results) vs. <1 × 105 cpm (n = 781 reference positive results), a significant difference was observed (p < 0.001) between the sensitivity point estimates [93.8% (95% CI: 87.1, 97.1) and 28.6% (95% CI: 16.2, 45.3), respectively]. Similar findings were associated with studies that were stratified by a Ct value of ≤30 (n = 2,536 reference positive results) and >30 (n = 679 reference positive results) [89.5% (95% CI: 85.3, 92.5) and 18.7% (95% CI: 12.9, 26.3), respectively] and those that were stratified by a Ct value of ≤25 (n = 897 reference positive results) and >25 (n = 673 reference positive results) [96.4% (95% CI: 94.3, 97.7) and 44.9% (95% CI: 33.0, 57.4), respectively]. Within a given viral load category, there were no statistical differences between studies performed with symptomatic subjects vs. studies performed with asymptomatic subjects; this was true regardless of the exact definition of viral load category: Ct of 25, Ct of 30, or cpm of 105 (Figure 5 and Table 3).

FIGURE 5.

Forest plots containing calculated sensitivity values for index [severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) antigen test] testing compared to reference [SARS-CoV-2 quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR assay)] test. Data are stratified by viral load [genomic copies/ml (cpm)] and by symptomatic or asymptomatic status.

True positives and false negatives by anatomic collection site were obtained from 97 data sets that included reference nasopharyngeal specimens and from 25 data sets that included nasal reference specimens. Antigen testing was usually paired from the same specimen type, only six data sets being non-paired (antigen nasal, reference nasopharyngeal) specimens. When analysis was performed on data stratified by anatomic collection site of the reference specimen, antigen test sensitivity was higher with a nasal specimen [82.7% (95% CI: 74.7, 88.5, p = 0.037); reference positive n = 1,654] compared to a nasopharyngeal specimen [73.1% (95% CI: 68.5, 77.2); reference positive n = 10,607] (Table 3).

Storage condition of the collected specimens was also analyzed as one factor that could affect antigen test sensitivity. True positives and false negatives by test storage condition of the specimen that underwent antigen testing were obtained from 133 data sets. When analysis was focused on storage condition for index testing, antigen test sensitivity was 75.3% (95% CI: 70.8, 79.3; reference positive n = 9,666) for fresh specimens and 70.9% (95% CI: 61.0, 79.1; reference positive n = 3,307) for frozen specimens. This observed difference was not, however, statistically significant (p = 0.375; Table 3).

Analytical sensitivity of the reference method (RT-qPCR) was determined using the manufacturer’s IFU when it was identified in the source documents and used to stratify true-positive and false-negative results associated with SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing. The LOD threshold for low and high analytical sensitivity was 500 cpm, which was the median (mean = 582) LOD value for the analytical sensitivity from all of the reference methods included in this subanalysis. Sensitivity values for antigen testing when stratified by high (reference positive n = 4,468) and low (reference positive n = 2,645) analytically sensitive reference methods were similar: 74.2% (95% CI: 66.9, 80.4) and 76.8% (95%CI: 67.2, 84.2), respectively (Table 3).

Manufacturer (Supplementary Table 1) and study spectrum bias were also significant factors in subgroup meta-analyses; higher sensitivity was reported in studies with large/moderate spectrum bias (Table 3). A mixed-effects meta-regression model with moderators including symptom status, anatomical collection site, study selection/spectrum bias, and manufacturer was fit to the studies. All factors remained significant in the multivariate analysis, except study spectrum bias (multivariate p = 0.757). The moderators accounted for 72% of study heterogeneity (model R2 = 0.722). Visual inspection of unadjusted and multivariate-adjusted funnel plots for effect estimates from individual sources against study size was performed (Figure 3). The funnel plot asymmetry revealed possible reporting/publication bias reflecting fewer studies than expected that could be characterized by a small group number and a low sensitivity estimate for the index. Overall, study heterogeneity could largely be accounted for by the independent variables identified through subgroup analysis in this study.

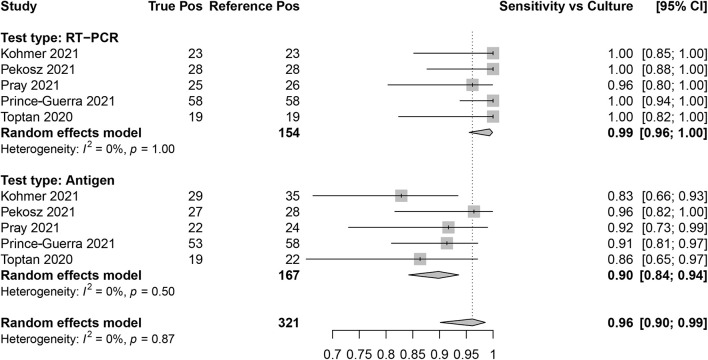

Culture as the Reference

Sensitivity for SARS-CoV-2 antigen and RT-qPCR assays was determined as compared with SARS-CoV-2 viral culture as the reference method. There were five data sets that contained RT-qPCR (reference positive n = 154) and antigen test (reference positive n = 167) results. The overall sensitivity for RT-qPCR was 99.0% (95% CI: 96.0, 100) and for antigen testing was 90.0% (95% CI: 84.0, 94.0; Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Forest plots containing calculated sensitivity values for index [severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) antigen test and SARS-CoV-2 quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR assay)] testing compared to reference (SARS-CoV-2 viral culture) test.

Specificity

Raw data for false-positive and true-negative rates were extracted from 63 of 81 of the included studies; the overall specificity across the included studies was 99.4% (95% CI: 99.3, 99.4) for antigen testing compared to RT-qPCR as the reference.

Discussion

The positive percent agreement point estimate (sensitivity) for antigen testing, spanning the entire 135 data sets included here, was 75.0% (95% CI: 71.0, 79.0). We found that factors including specimen viral load, symptom presence, DSO, anatomical collection site, and the storage conditions for specimen collection could all affect the measured performance of SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1). In addition, our meta-analysis revealed that antigen test sensitivity [96.0% (95% CI: 90.0, 99.0)] was highest in SARS-CoV-2-positive individuals with an increased likelihood of being infectious at the time of testing (e.g., culture positive; Pekosz et al., 2021). Although specificity data were not extracted for every study included in this meta-analysis, SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing had high specificity as published previously (Brümmer et al., 2021). Experimental factors such as anatomical collection site, specimen storage conditions, analytical sensitivity of reference, and composition of the study population with respect to symptomology all varied across the field of studies included here.

This meta-analysis adds to the conclusions of others that viral load is clearly the most important factor that influences sensitivity for SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing. Two related meta-analyses have been published to date. The first by Dinnes et al. (2020) had the following key differences: (1) Dinnes et al. (2020) utilized numerous categories of point-of-care tests beyond antigen-based testing; (2) Dinnes et al. (2020) included five articles for antigen testing in their work; and (3) Dinnes et al. (2020) did not stratify the meta-analysis results for antigen testing by study design/viral load as is performed in this work. The second by Brümmer et al. (2021) had the following key differences: (1) Brümmer et al. (2021) focused on commercial rapid antigen tests; (2) Brümmer et al. (2021) only included 48 articles for antigen testing in their work; and (3) Brümmer et al. (2021) did not stratify the meta-analysis results for antigen test performance by study design characteristics as is performed in this work.

Test sensitivity was stratified by RT-qPCR Ct value (using both 25 cycles and 30 cycles as the cutoff); an inverse relationship was shown between Ct value and SARS-CoV-2 antigen test sensitivity. Both the ≤25 Ct group and the ≤30 Ct group had significantly higher sensitivities than their >25 Ct and >30 Ct counterparts, respectively, regardless of subjects’ symptom status. These results are consistent with those from previous studies (COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group Rapid Evidence Report, 2020; Dinnes et al., 2020; Brümmer et al., 2021). However, Ct value has been shown by different groups to have a low correlation between different RT-qPCR assays and platforms (Ransom et al., 2020; Rhoads et al., 2020). RT-qPCR assays have different analytical sensitivities; a universal Ct value reference has not been established that can be used to define the optimal sensitivity/specificity characteristics for antigen testing. In addition to stratification by Ct value, analysis was also performed for SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing sensitivity by absolute viral load (using 1 × 105 as the cutoff). When data were analyzed using this strategy, similar results were observed as for stratification by Ct value. The viral load threshold utilized here was determined by a consensus value that appeared with regular frequency from the source articles and represented a viral threshold that consistently delineated a zone across which the false-positive rate increased for most antigen tests. It is generally accepted that viral loads of less than 1 × 105 cpm correlate with non-culture-positive levels. However, whether 1 × 105 cpm is the most accurate threshold by which to measure antigen test performance is still a topic for debate. Some studies suggest that viral loads closer to 1 × 106 cpm might be a more appropriate threshold, which would act to minimize false-positive rates (Berger et al., 2020; Larremore et al., 2020; La Scola et al., 2020; Quicke et al., 2020; van Kampen et al., 2020; Wolfel et al., 2020).

Several factors identified here that affect SARS-CoV-2 antigen test performance have been identified in previous studies to affect specimen viral load. For example, a significant difference in sensitivity for detection was noted here between symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. However, stratification in both symptomatic and asymptomatic specimen groups by high viral load has a similar effect of increasing test sensitivity. Our data show that 84% of SARS-CoV-2-positive specimens from symptomatic individuals corresponded to a high viral load, whereas only 56% of SARS-CoV-2-positive specimens from asymptomatic individuals qualified as high viral load in this analysis. This bias may be due to the difficulty of estimating the timing of peak viral load in asymptomatic individuals when attempting to compare the natural history of viral load trajectory in symptomatic vs. asymptomatic individuals (Smith et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the presence of symptoms probably overlaps with a higher specimen viral load, which subsequently affects the antigen test sensitivity. Anatomical collection type of the index and/or reference test method can affect the measured sensitivity estimates of antigen testing during a clinical trial, also through a mechanism that involves increased/decreased viral load on the specimen swab. Evidence suggests that viral loads may be higher with nasopharyngeal than with nasal collection (Pinninti et al., 2020). This difference may explain why measured antigen assay performance appears to be higher in studies that use a nasal RT-qPCR reference method.

Another factor identified here as potentially influencing measured antigen assay sensitivity was specimen storage, particularly with regard to the use of fresh vs. frozen (i.e., “banked”) specimens. It is likely that protein antigen may, as the result of freeze/thawing, experience some degree of structural damage potentially leading to loss of epitope availability or a reduction in the affinity of epitope/paratope binding. Ninety-six data sets involved fresh specimens for antigen testing, and 23 data sets included freeze/thawed specimens for antigen testing. Although no statistically significant difference was detected between sensitivities for antigen test conducted on fresh vs. frozen specimens, possibly due to the low data set group number in the frozen antigen group, a trend toward lower sensitivity was observed for tests performed on frozen specimens [75.3% (95% CI: 70.8, 79.3) for fresh vs. 70.9% (95% CI: 61.0, 79.1) for frozen]. In contrast, no similar trend was observed for specimen storage condition related to RT-qPCR testing [75.4% (95% CI: 70.6, 79.6) for fresh vs. 77.7% (95% CI: 69.3, 84.3) for frozen]. Additional results from in-house (i.e., a BD-IDS laboratory) testing with two different EUA authorized antigen assays demonstrate reduced immunoassay band intensity following freeze–thaw cycles, thus further supporting the findings from the meta-analysis that a freeze–thaw cycle could reduce analytical sensitivity for SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing (Supplementary Figure 2).

The analytical sensitivity associated with the reference RT-qPCR assay was also investigated here as a possible variable that could affect the false-negative rate of SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing. We hypothesized that relatively high analytical sensitivity for the reference RT-qPCR assay would impose a detection bias and result in decreased clinical sensitivity due to increased false negatives occurring near the RT-qPCR LOD. However, stratification by reference analytical sensitivity resulted in no difference in SARS-CoV-2 antigen test clinical sensitivity. It is likely that the analytical sensitivity of RT-qPCR, regardless of the manufacturer, is high enough that even relatively low sensitivity RT-PCR assays are still well below the corresponding LOD for antigen testing. On the other hand, some manufacturers evaluate antigen test performance in a manner that involves sensitivity above and below a set Ct value. It is possible that analysis involving stratification by RT-qPCR analytical sensitivity could reveal differences in antigen test performance if all antigen test performances were determined in a similar manner that involves predetermined high/low viral load categories.

Several population- and study design-specific factors were identified to be associated with higher measured assay sensitivity likely due to the association with higher viral loads. This meta-analysis demonstrates that these factors exist in various combinations across studies in an inconsistent way, thus making comparisons of assay performance across these studies impossible. The lack of consistency across study designs makes it very difficult to compare point estimates between antigen tests to judge their relative clinical efficacy. The introduction of different forms of bias into the study design, and during study conduct, could explain why discrepancies have been noted, for example, between sensitivity values listed in manufacturers’ IFUs and those obtained during independent evaluation of the same antigen test. Ultimately, direct comparison between antigen tests should be the most reliable approach for obtaining relative performance characteristics with any certainty. Here, we stratified SARS-CoV-2 antigen test sensitivity by spectrum bias associated with each of the data sources. We found that those studies rated with higher spectrum bias also had higher antigen test sensitivities. In addition, the funnel plot analysis that was performed for this meta-analysis shows obvious publication bias, which implicated a lack of publication of studies with low study group number and low sensitivity.

Clinical trials and studies involving diagnostics are vulnerable to the introduction of bias, which can alter test performance results and obstruct an accurate interpretation of clinical efficacy or safety. For example, antigen testing appears to have a higher sensitivity when compared to SARS-CoV-2 viral culture as the reference than when compared to RT-PCR. However, these two reference methods measure different targets: RNA only vs. infectious virus. Therefore, their use as a reference method should be intended to answer different scientific questions rather than artificially inflating apparent sensitivity point estimates. If the intent of a diagnostic test is determining increased risk of infectiousness through the presence of replicating virus, the high analytical sensitivity of RT-qPCR, which cannot distinguish RNA fragments from infectious virus, renders this diagnostic approach vulnerable to the generation of false-positive results, particularly at later time points following symptom onset. At time points beyond 1 week from symptom onset, a positive RT-qPCR result more likely indicates that an individual has been infected but is no longer contagious and cannot spread infectious virus. This is especially true for those with a SARS-CoV-2-negative cell culture result. Previous reports have shown that performance values for rapid antigen tests and SARS-CoV-2 viral culture exhibit better agreement than do results from RT-qPCR compared to viral culture in symptomatic individuals, thus making it a good test to identify individuals who are likely to be shedding infectious virus and therefore have potential to transmit SARS-CoV-2 (Pekosz et al., 2021). With this current analysis, we further show that antigen testing is also able to reliably identify asymptomatic individuals with viral load indicative of shedding infectious virus (1 × 105 cpm and/or a Ct score ≤30).

This work focused on factors that can affect antigen test sensitivity for detection of SARS-CoV-2. RT-qPCR testing and other forms of testing (such as molecular point-of-care assays or serological testing) have been characterized and described as diagnostic approaches for SARS-CoV-2 elsewhere (Carter et al., 2020). Several assay characteristics, including time to result (Peeling et al., 2021), analytical sensitivity (Mak et al., 2020), cost per test (Neilan et al., 2020; Kepczynski et al., 2021; Love et al., 2021; Jakobsen et al., 2021b), infrastructure requirements for testing (Augustin et al., 2020), and volume of testing (Carter et al., 2020), need to be considered before determining the most appropriate testing strategy. As the priorities for specific test characteristics differ between testing sites, so does the overall value of a given diagnostic test.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it was difficult to obtain reliable information across the sources, in a consistent manner, about disease severity in order to perform a meta-analysis on this aspect of COVID-19 diagnostics. Additionally, the studies included in this meta-analysis did not contain sufficient information to explore the potential effect of factors previously demonstrated to be associated with higher viral loads such as disease severity and community prevalence.

Conclusion

In addition to viral load, several factors including symptom status, anatomical collection site, and spectrum bias all influenced the sensitivity for SARS-CoV-2 detection by antigen-based testing. This heterogeneity of factors found to influence measured assay sensitivity, across studies, precludes comparison of assay sensitivity from one study to another. Future consideration regarding standardization of these factors for antigen assay performance studies is warranted in order to aid in results interpretation and relative performance assessment.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Author Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the United States Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflict of Interest

VP, DG, Y-CL, DM, LC, JM, JA, and CC are employees of Becton, Dickinson and Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Eckert (Becton, Dickinson and Company, BD Life Sciences–Diagnostic Systems) for her input on the content of this manuscript and editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Funding

This study was funded by Becton, Dickinson and Company, BD Life Sciences–Integrated Diagnostic Solutions. Non-BD employee authors received research funds to support their work for this study. YCM received salary support from the National Institutes of Health grant funding (U5411090366, U54EB007958-12, and 3U54HL143541-02S2).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.714242/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough Inc (2020a). BinaxNOWTM COVID-19 Ag CARD HOME TEST[package insert, EUA]. Scarborough, ME: Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough Inc (2020b). BinaxNOWTM COVID-19 Ag CARD [package insert, EUA]. Scarborough, ME: Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelrazik A. M., Elshafie S. M., Abdelaziz H. M. (2020). Potential use of antigen-based rapid test for SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory specimens in low-resource settings in egypt for symptomatic patients and high-risk contacts. Lab. Med. 52 e46–e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulrahman A., Mustafa F., Alawadhi A. I., Alansari Q., Alalawi B., Alqahtani M. (2020). Comparison of SARS-COV-2 nasal antigen test to nasopharyngeal RT-PCR in mildly symptomatic patients. medRxiv [Preprint] 10.1101/2020.11.10.20228973 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Access Bio (2020). CareStartTM COVID-19 Atigen-Rapid Diagnostic Test for the Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Antigen [package insert, EUA]. Somerset, NJ: Access Bio, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Accorsi E. K., Qiu X., Rumpler E., Kennedy-Shaffer L., Kahn R., Joshi K., et al. (2021). How to detect and reduce potential sources of biases in studies of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 36 179–196. 10.1007/s10654-021-00727-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert E., Torres I., Bueno F., Huntley D., Molla E., Fernández-Fuentes M., et al. (2020). Field evaluation of a rapid antigen test (PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device) for COVID-19 diagnosis in primary healthcare centres. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 27 472.e7–472.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemany A., Baró B., Ouchi D., Rodó P., Ubals M., Corbacho-Monné M., et al. (2021). Analytical and clinical performance of the panbio COVID-19 antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic test. J. Infect. 82 186–230. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.12.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki K., Nagasawa T., Ishii Y., Yagi S., Kashiwagi K., Miyazaki T., et al. (2021). Evaluation of clinical utility of novel coronavirus antigen detection reagent, Espline§SARS-CoV-2. J. Infect. Chemother. 27 319–322. 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki K., Nagasawa T., Ishii Y., Yagi S., Okuma S., Kashiwagi K., et al. (2020). Clinical validation of quantitative SARS-CoV-2 antigen assays to estimate SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in nasopharyngeal swabs. J. Infect. Chemother. 27 613–616. 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin M., Schommers P., Suárez I., Koehler P., Gruell H., Klein F. (2020). Rapid response infrastructure for pandemic preparedness in a tertiary care hospital: lessons learned from the COVID-19 outbreak in Cologne, Germany, February to March 2020. Euro Surveill. 25:2000531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balduzzi S., Rücker G., Schwarzer G. (2019). How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid. Based Ment. Health 22 153–160. 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BD (2020a). BD VeritorTM System for Rapid Detection of SARS-CoV-2 [package insert, EUA]. Franklin Lakes, NJ: Becton, Dickinson and Company. [Google Scholar]

- BD (2020b). BD VeritorTM System for Rapid Detection of SARS-CoV-2 [package insert, CE Mark]. Franklin Lakes, NJ: Becton, Dickinson and Company. [Google Scholar]

- BD (2020c). BD VeritorTM Triplex System for Rapid Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and Flu A/B [package insert, EUA]. Franklin Lakes, NJ: Becton, Dickinson and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Beck E. T., Paar W., Fojut L., Serwe J., Jahnke R. R. (2021). Comparison of the Quidel Sofia SARS FIA test to the Hologic Aptima SARS-CoV-2 TMA test for diagnosis of COVID-19 in symptomatic outpatients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 59:e2727-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger A., Ngo Nsoga M. T., Perez-Rodriguez F. J., Aad Y. A., Sattonnet-Roche P., Gayet-Ageron A. (2020). Diagnostic accuracy of two commercial SARS-CoV-2 Antigen-detecting rapid tests at the point of care in community-based testing centers. medRxiv [Preprint] 10.1101/2020.11.20.20235341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Moher D., Petticrew M., Stewart L. (2011). An international registry of systematic-review protocols. Lancet 377 108–109. 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60903-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brümmer L. E., Katzenschlager S., Gaeddert M., Erdmann C., Schmitz S., Bota M. (2021). The accuracy of novel antigen rapid diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 18:e1003735. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulilete O., Lorente P., Leiva A., Carandell E., Oliver A., Rojo E., et al. (2020). Evaluation of the PanbioTM rapid antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 in primary health care centers and test sites. medRxiv [Preprint] 10.1101/2020.11.13.20231316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin S. A., Nolan T. (2020). RT-qPCR testing of SARS-CoV-2: a primer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:3004. 10.3390/ijms21083004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlos W. G., Dela Cruz C. S., Cao B., Pasnick S., Jamil S. (2020). Novel Wuhan (2019-nCoV) Coronavirus. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 201 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter L. J., Garner L. V., Smoot J. W., Li Y., Zhou Q., Saveson C. J. (2020). Assay techniques and test development for COVID-19 diagnosis. ACS Cent. Sci. 6 591–605. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celltrion (2020). SampinuteTM COVID-19 Antigen MIA [package insert, EUA]. Jersey City, NJ: Celltrion. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (2020). Interim Guidance for Antigen Testing for SARS-CoV-2. Available Online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html (accessed May 24, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti F., Burdino E., Milia M. G., Allice T., Gregori G., Bruzzone B., et al. (2020). Urgent need of rapid tests for SARS CoV-2 antigen detection: evaluation of the SD-Biosensor antigen test for SARS-CoV-2. J. Clin. Virol. 132:104654. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaimayo C., Kaewnaphan B., Tanlieng N., Athipanyasilp N., Sirijatuphat R., Chayakulkeeree M., et al. (2020). Rapid SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection assay in comparison with real-time RT-PCR assay for laboratory diagnosis of COVID-19 in Thailand. Virol. J. 17:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang D., Lin M., Wei L., Xie L., Zhu G., Dela Cruz C. S., et al. (2020). Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus infections involving 13 patients outside Wuhan, China. JAMA 323 1092–1093. 10.1001/jama.2020.1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciotti M., Maurici M., Pieri M., Andreoni M., Bernardini S. (2021). Performance of a rapid antigen test in the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Med. Virol. 93 2988–2991. 10.1002/jmv.26830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colavita F., Vairo F., Meschi S., Valli B., Lalle E., Castilletti C., et al. (2020). COVID-19 antigen rapid test as screening strategy at the points-of-entry: experience in Lazio Region, Central Italy, August-October 2020. medRxiv [preprint] 10.1101/2020.11.26.20232728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group Rapid Evidence Report (2020). Available Online at: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/ppih/if-ppih-covid-19-sag-performance-and-feasibility-of-rapid-covid-19-tests-rapidreview.pdf (accessed May 24, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Courtellemont L., Guinard J., Guillaume C., Giaché S., Rzepecki V., Seve A., et al. (2021). High performance of a novel antigen detection test on nasopharyngeal specimens for SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis: a prospective study. medRxiv [Preprint] 10.1101/2020.10.28.20220657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao B., Wen K., Zhang J., Chen J., Han C., Chen Y., et al. (2020). Accuracy of a nucleocapsid protein antigen rapid test in the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 27 289.e1–289.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinnes J., Deeks J. J., Adriano A., Berhane S., Davenport C., Dittrich S., et al. (2020). Rapid, point-of-care antigen and molecular-based tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8:Cd013705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drain P. K., Ampajwala M., Chappel C., Gvozden A. B., Hoppers M., Wang M., et al. (2020). A rapid, high-sensitivity SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid immunoassay to aid diagnosis of acute COVID-19 at the point of care. medRxiv [preprint] 10.1101/2020.12.11.20238410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevinek P., Hurych J., Kepka Z., Briksi A., Kulich M., Zajac M., et al. (2020). The sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests in the view of large-scale testing. medRxiv [preprint] 10.1101/2020.11.23.20237198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellume Limited (2020). Ellume COVID-19 Home Test [package insert, EUA]. Australia: Ellume Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Favresse J., Gillot C., Oliveira M., Cadrobbi J., Elsen M., Eucher C., et al. (2021). Head-to-head comparison of rapid and automated antigen detection tests for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Clin. Med. 10:265. 10.3390/jcm10020265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenollar F., Bouam A., Ballouche M., Fuster L., Prudent E., Colson P., et al. (2021). Evaluation of the Panbio COVID-19 rapid antigen detection test device for the screening of patients with COVID-19. J. Clin. Microbiol. 59:e2589-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration (2011). Establishing the Performance Characteristics of In Vitro Diagnostic Devices for the Detection or Detection and Differentiation of Influenza Viruses - Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff. Available Online at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/establishing-performance-characteristics-vitro-diagnostic-devices-detection-or-detection-and (accessed May 24, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Gatsonis C., Paliwal P. (2006). Meta-analysis of diagnostic and screening test accuracy evaluations: methodologic primer. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 187 271–281. 10.2214/ajr.06.0226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri B., Pandey S., Shrestha R., Pokharel K., Ligler F. S., Neupane B. B. (2021). Review of analytical performance of COVID-19 detection methods. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 413 35–48. 10.1007/s00216-020-02889-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gremmels H., Winkel B. M. F., Schuurman R., Rosingh A., Rigter N. A. M., Rodriguez O., et al. (2021). Real-life validation of the PanbioTM COVID-19 antigen rapid test (Abbott) in community-dwelling subjects with symptoms of potential SARS-CoV-2 infection. EClinicalMedicine 31:100677. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith G. J., Morris T. T., Tudball M. J., Herbert A., Mancano G., Pike L., et al. (2020). Collider bias undermines our understanding of COVID-19 disease risk and severity. Nat. Commun. 11:5749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Lau E. H. Y., Wu P., Deng X., Wang J., Hao X., et al. (2020). Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26 672–675. 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsu Y., Maejima M., Shibusawa M., Amemiya K., Nagakubo Y., Hosaka K., et al. (2021). Analysis of a persistent viral shedding patient infected with SARS-CoV-2 by RT-qPCR, FilmArray respiratory Panel v2.1, and antigen detection. J. Infect. Chemother. 27 406–409. 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsu Y., Maejima M., Shibusawa M., Nagakubo Y., Hosaka K., Amemiya K., et al. (2020). Comparison of automated SARS-CoV-2 antigen test for COVID-19 infection with quantitative RT-PCR using 313 nasopharyngeal swabs, including from seven serially followed patients. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 99 397–402. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehl S., Schenk B., Rudych O., Göttig S., Foppa I., Kohmer N., et al. (2020). At-home self-testing of teachers with a SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen test to reduce potential transmissions in schools. medRxiv [preprint] 10.1101/2020.12.04.20243410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houston H., Gupta-Wright A., Toke-Bjolgerud E., Biggin-Lamming J., John L. (2021). Diagnostic accuracy and utility of SARS-CoV-2 antigen lateral flow assays in medical admissions with possible COVID-19. J. Hosp. Infect. 110 203–205. 10.1016/j.jhin.2021.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jääskeläinen A. E., Ahava M. J., Jokela P., Szirovicza L., Pohjala S., Vapalahti O., et al. (2021). Evaluation of three rapid lateral flow antigen detection tests for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Clin. Virol. 137:104785. 10.1016/j.jcv.2021.104785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen K. K., Jensen J. S., Todsen T., Lippert F., Martel C. J.-M., Klokker M., et al. (2021a). Detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection by rapid antigen test in comparison with RT-PCR in a public setting. medRxiv [preprint] 10.1101/2021.01.22.21250042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen K. K., Jensen J. S., Todsen T., Tolsgaard M. G., Kirkby N., Lippert F., et al. (2021b). Accuracy and cost description of rapid antigen test compared with reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Dan Med. J. 68:A03210217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James A. E., Gulley T., Kothari A., Holder K., Garner K., Patil N. (2021). Performance of the BinaxNOW COVID-19 Antigen Card test relative to the SARS-CoV-2 real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay among symptomatic and asymptomatic healthcare employees. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 10.1017/ice.2021.20 Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi K., Ishii Y., Aoki K., Yagi S., Maeda T., Miyazaki T., et al. (2020). Immunochromatographic test for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva. medRxiv [Preprint] 10.1101/2020.05.20.20107631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepczynski C. M., Genigeski J. A., De Regnier D. P., Jadhav E. D., Sohn M., Klepser M. E. (2021). Performance of the BD Veritor system SARS-CoV-2 antigen test among asymptomatic collegiate athletes: a diagnostic accuracy study. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharmacy 3 100047–100047. 10.1016/j.rcsop.2021.100047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]