Abstract

Depression is common following HIV infection and often improves after ART initiation. We aimed to identify distinct dimensions of depression that change following ART initiation in persons with HIV(PWH) with minimal comorbidities(e.g., illicit substance use) and no psychiatric medication use. We expected that dimensional changes in improvements in depression would differ across PWH. In an observational cohort in Rakai, Uganda, 312 PWH(51% male; mean age=35.6 years) completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression(CES-D) scale before and up to two years after ART initiation. Twenty-two percent were depressed(CES-D scores ≥16) pre-ART that decreased to 8% after ART. All CES-D items were used in a latent class analysis to identify subgroups with similar change phenotypes. Two improvement phenotypes were identified: affective-symptom improvement(n=58, 19%) and mixed-symptom improvement(effort, appetite, irritability; n=41, 13%). The affect-improvement subgroup improved on the greatest proportion of symptoms(76%). A third subgroup was classified as nosymptom changes(n=213, 68%) as they showed no difference is symptom manifestation from baseline (93% did not meet depression criteria) to post-ART. Factors associated with subgroup membership in the adjusted regression analysis included pre-ART self-reported functional capacity, CD4 count, underweight BMI, hypertension, female sex(P’s<0.05). In a subset of PWH with CSF, subgroup differences were seen on Aβ-42, IL-13, and IL-12. Findings support that depression generally improves following ART initiation; however, when improvement is seen the patterns of symptom improvement differ across PWH. Further exploration of this heterogeneity and its biological underpinning is needed to evaluate potential therapeutic implications of these differences.

Keywords: HIV, global health, antiretroviral, depression, heterogeneity

Introduction

Clinically significant depressive symptoms are common following an HIV infection diagnosis and may even be more common among those with preexisting depression. Several studies (Eaton et al, 2017; Hellmuth et al, 2017; Manne-Goehler et al, 2019), but not all (Gold et al, 2014), indicate that depression decreases following suppressive antiretroviral therapy (ART). Nevertheless, the post-ART rates of depression among people with HIV (PWH) (Rubin and Maki, 2019) often remain higher than the general population (Bing et al, 2001; Cook et al, 2018; Do et al, 2014; Orlando et al, 2002). Delineating the cause and effect in the entangled relationship between HIV and depression remains elusive (Cournos et al, 2005; Triesman and Angelino, 2004). Focusing on dimensions of depression that improve after ART may provide a more optimal framework for understanding the biological mechanisms and social factors (e.g., entering HIV care) contributing to depression improvement after ART initiation.

The phenotypic expression of depression is highly heterogeneous with depressed individuals often exhibiting markedly different profiles of somatic (e.g., sleep, appetite) and non-somatic (e.g., affective) symptoms (Goldberg, 2011). The multidimensionality of depression (Gibbons et al, 1993) should be considered generally in PWH and how ART initiation changes these symptoms also warrants investigation. The effects of ART itself and the subsequent viral suppression on depressive symptoms may contribute to significant heterogeneity, particularly given evidence of variation in the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of depression in this group such as varying changes in monoamine levels and neurotrophic pathways (Treisman et al, 2001).

In this study, we aimed to examine changes in overall depression rates and changes in dimensions of depression following ART initiation in a rural Ugandan cohort of PWH with minimal comorbidities (e.g., illicit substance use, obesity) and no psychiatric medication use. Similar to other studies, we expected that depression overall would improve after ART initiation; however, we hypothesized that dimensional changes in depression would differ across PWH. We also aimed to examine factors associating with dimensional changes in depression including socio-demographic, clinical, behavioral, and CSF cytokines and neurodegenerative biomarkers.

Methods

Participants

We evaluated 312 PWH before and approximately two-years after initiating ART at the Rakai Health Sciences Program (RHSP) supported HIV clinics and the Rakai Community Cohort Study. This open, community-based cohort includes participants residing in 40 communities in rural Rakai District, Uganda. Eligible participants were ART-naïve PWH, over the age of 20 with advanced immunosuppression (n=147, CD4 < 200 cells/μL) or moderate immunosuppression (n=165, CD4 350-500 cells/μL) at the time of enrollment. Additional exclusion criteria for the overall study included severe cognitive or psychiatric impairment precluding written consent (participants answered several questions about the study to demonstrate their ability to understand the nature of the study and their competency to provide informed consent), physical disability preventing travel to the RHSP clinic for study procedures, known CNS opportunistic infections, or prior CNS disease.

Study procedures

Participants were enrolled between August 2013 and July 2015. They completed a sociodemographic survey, including self-reported substance use, and behavioral interview, mental health and neurological screeners (e.g., International HIV Dementia Scale-IHDS (Sacktor et al, 2005)), neuropsychological test battery (Rubin et al, 2019), functional status assessments (e.g., Patient Assessment of Own Functioning Inventory-PAOFI (Richardson-Vejlgaard et al, 2009), a neuromedical evaluation by a Ugandan medical officer, and peripheral blood draw to assess HIV status (CD4 cell count, HIV RNA). A subset of participants (n=61) consented to receive an optional lumbar puncture at enrollment, and CSF levels of 17 cytokines/chemokines (Human 17-Plex Panel, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and 20 biomarkers of neurodegeneration (Milliplex Catalog: HMMP1-55K-03; HMMP2-55K-05; HNDG4MAG-36K-05; HND1MAG-39K-07; HNDG3MAG-36K-10) were measured by multiplex assays using with the Luminex-200® system in combination with Luminex manager software (Bioplex manager 5·0, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) (Abassi et al, 2017).

Depressive Symptomatology

We used the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a 20-item questionnaire measuring how often (0 “rarely” to 3 “most of the time”) participants experience depressive symptomatology including emotional, somatic, and interpersonal symptoms in the two weeks before assessment (Radloff, 1977). Emotional symptoms on the CES-D include negative affect (e.g. depressed, lonely) and positive affect (or absence of, anhedonia)(e.g. hopefulness, feelings that life is enjoyable), while somatic symptoms include unpleasant or worrisome bodily sensations, including sleep, appetite, and concentration (Kapfhammer, 2006). Finally, interpersonal symptoms on the CES-D reflect interpersonal challenges (e.g. feeling as though people were unfriendly or disliked oneself). The CES-D has excellent reliability, validity, and factor structure (Radloff, 1977) and is commonly used in studies involving PWH in sub-Saharan Africa (Bernard et al, 2017; Kemigisha et al, 2019; Nakasujja et al, 2010). A CES-D total score ≥16 was considered clinically significant depressive symptoms. However, the primary outcomes used for analysis were the item-level responses rather than a total score or factor analytic driven composite symptom scores (e.g., negative, lack of positive affect, somatic) as the correlation patterns (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2) did not align with prior studies (Kim et al, 2011).

The CES-D was translated into the predominant local language of Luganda and then back-translated into English for accuracy. The tool was then administered in the participants’ preferred language which, for the majority of participants, was the local language of Luganda.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Participants gave written informed consent for study participation. The study was approved by Western Institutional Review Board, the Uganda Virus Research Institute Research and Ethics Committee, and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology.

Statistical Analysis

Using the pre- and post-ART CES-D item responses, a reliable change index was calculated for each item and participant (Busch et al, 2011) using the standard error of the difference formula from Jacobson and Truax (Jacobson and Truax, 1991), and the test-retest reliability from PWH (Supplemental Table 3). The reliable change index is a standardized difference score that allows a threshold to be set for change which is considered reliable, meaning not due to measurement error alone. A reliable change index cutoff at 1.645 per-item was considered clinically meaningful change (Brouillette et al, 2016; Norman et al, 2003). We only focused on clinically meaningful improvement for each CES-D item as clinically meaningful decline was rare with less than 5% of participants demonstrating significant decline on any of the 20 CES-D items. There was no missing data at the item-level for participants and RCI for each item were normally distributed prior to dichotomizing into categories of either present of absent clinically meaningful improvement (reliable change index cutoff of 1.645).

Each of the CES-D items (20) that had been dichotomized (clinically meaningful change vs. not) were then used in a latent class analysis (LCA) to identify homogenous subgroups of PWH with similar dimensional changes in depressive symptoms after ART initiation. LCA is a latent variable statistical technique used to identify a few mutually exclusive latent (unobservable) classes of individuals (Hagenaars and McCutcheon, 2002). These classes are based on the individuals’ responses to a set of measured (observed) continuous variables - in this case, performance on the CES-D. Advantages of LCA include: 1) use of an objective approach (model-based, relies on probabilities, and model fit statistics), 2) consideration of all variables jointly (e.g., changes in all 20 items simultaneously after ART initiation; Supplemental Table 4) 3) ability to capture complex patterns of variables, and 4) ability to handle a high degree of multi-collinearity (Stanley et al, 2017). Five separate LCA solutions were examined and consisted of 2- to 4- clusters each. To determine the best fitting model in terms of balancing fit and parsimony several standard model fit statistics were used, including Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC; lower = better model fit), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; lower = better model fit), entropy (higher suggests better class separation, ideally >0.80), and interpretability of the models. The posterior probability of an individual’s membership in each latent class was extracted from the best fitting model. Individuals were assigned to the latent class in which their posterior probability of membership was highest. The subtype names used in the results are based on the predominant symptom changes observed in each latent class.

Group membership was then used as the primary predictor variable for all subsequent analyses to probe differences among classes. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests were used for continuous and categorical variables respectively. A single generalized estimating equation (GEE) model was conducted to examine group membership differences in the pre-ART CSF biomarker panel. LCA analyses were done with Mplus statistical software (version 7.4). All other analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC). Significance was set at p<0.05; trends were noted at p>0.05 and p<0.10.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Participants included 312 PWH, of whom 51% were male and had an average age of 35.6 years (Table 1). Pre-ART, 47% had a CD4 count ≤200, 53% between 350 and 500, and HIV RNA ranged from undetectable to 6.6 log copies[cp]/ml (median=4.6 log cp/ml, IQR=1.2). Twenty-two percent of the overall sample met CES-D criteria for depression pre-ART and 8% met depression criteria post-ART. Cardiovascular comorbidities were minimal, and participants did not report using common neuropsychiatric medications including antidepressants, at the pre- or post-ART visit. Forty-three percent of participants used alcohol, 15% smoked tobacco, and narcotic use was rare (n=7, 2.2%). Post-enrollment, the most common ART regimen that PWH were on was on Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)+Lamivudine (3TC)+Efavirenz (EFV) (n=260, 83%). Additional regimens included: TDF+3TC+Nevirapine (NVP)(n=12; 4%), Zidovudine (AZT)+3TC+NVP (n=7; 2%), AZT+3TC+EFV (n=4; 1%), TDF+3TC+Lopinavir (n=1; <1%); Abacavir+EFV (n=1; <1%), and 27 (9%) did not know the name of their ART regimen. At the two-year follow-up, the median CD4 count was 394 (IQR=254), and 85% (n=262) had undetectable viral loads (cut-off 40 copies/ml). The subset of participants who had consented to give CSF samples (n=61) was similar demographically to the overall subset of participants (P’s>0.25; Supplemental Table 5).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics in the overall sample and as a function of changes in depression from pre- to post-antiretrovirals (ART).

| Overall Sample (N=312) N (%) |

Never depressed (n=235; 75%) n (%) |

Depressed to not depressed (n=52; 17%) n (%) |

Not depressed to depressed (n=8; 3%) n (%) |

Always depressed (n=17; 5%) n (%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ART | ||||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 35.6 (8.5) | 35.0 (8.0) | 37.3 (10.5) | 32.9 (6.0) | 38.8 (6.9) | 0.09 |

| Education, mean (SD) | 5.4 (3.3) | 5.6 (3.3) | 4.9 (3.4) | 4.6 (2.9) | 4.3 (2.8) | 0.20 |

| Female sex | 154 (49) | 107 (45) | 31 (60) | 7 (87) | 9 (53) | 0.04 |

| Married | 200 (64) | 152 (65) | 31 (60) | 5 (62) | 12 (70) | 0.85 |

| BMI | 22.1 (3.5) | 22.1 (3.3) | 21.8 (3.7) | 24.3 (7.4) | 22.6 (3.3) | 0.26 |

| Underweight | 27 (9) | 14 (6) | 12 (23) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 0.001 |

| Overweight/obese | 45 (14) | 31 (13) | 9 (17) | 2 (25) | 3 (18) | 0.68 |

| Tobacco use | 46 (15) | 33 (14) | 7 (13) | 0 (0) | 6 (35) | 0.06 |

| Alcohol use | 157 (50) | 125 (53) | 17 (33) | 4 (50) | 11 (65) | 0.03 |

| Narcotic use | 7 (2) | 5 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) | 0.04 |

| Hypertension | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.02 |

| High cholesterol | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.93 |

| PAOFI total, mean (SD) | 146.9 (18.7) | 151.1 (14.0) | 135.5 (25.1) | 146.0 (16.9) | 124.8 (24.5) | <0.001 |

| IHDS total, mean (SD) | 9.2 (1.8) | 9.3 (1.7) | 8.9 (2.0) | 8.9 (1.2) | 8.1 (2.2) | 0.03 |

| CD4 count, mean (SD) | 268.2 (166.9) | 278.2 (166.3) | 215.6 (158.6) | 277.1 (160.4) | 287.3 (186.1) | 0.07 |

| Log viral load (cp/ml), mean (SD) | 4.5 (1.0) | 4.5 (0.9) | 4.6 (1.2) | 4.1 (0.8) | 4.5 (0.9) | 0.51 |

| HIV subtype† | 0.92 | |||||

| A1 | 30 (43) | 25 (44) | 4 (40) | - | 1 (33) | |

| D | 40 (57) | 32 (56) | 6 (60) | - | 2 (67) | |

| ART-medication initiated | ||||||

| EFV | 265 (85) | 195 (83) | 49 (94) | 7 (87) | 14 (82) | 0.23 |

| TDF+3TC+EFV | 260 (83) | 191 (81) | 48 (92) | 7 (87) | 14 (82) | 0.28 |

| CPE, mean (SD) | 5.6 (1.9) | 5.6 (2.0) | 5.8 (1.2) | 5.2 (2.1) | 6.2 (0.4) | 0.48 |

| Post-ART | ||||||

| Undetectable viral load (<40cp/ml) | 262 (85) | 197 (85) | 43 (84) | 7 (87) | 15 (88) | 0.98 |

| ∆ Pre- to Post-ART, mean (SD) | ||||||

| PAOFI total | −6.4 (16.2) | −4.6 (13.5) | −12.9 (21.9) | −6.2 (6.8) | −11.2 (23.4) | 0.005 |

| IHDS total | −0.7 (1.9) | −0.7 (1.9) | −0.7 (2.0) | −0.3 (1.1) | −0.7 (2.2) | 0.94 |

| BMI | 0.7 (2.1) | 0.5 (2.0) | 1.7 (2.5) | 0.3 (2.4) | −0.2 (2.1) | 0.001 |

| CD4 count | 144.1 (163.1) | 141.2 (169.2) | 170.0 (150.6) | 126.1 (124.4) | 114.0 (120.6) | 0.57 |

Note. ∆ = change values 3TC=Lamivudine; BMI=body mass index; CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Depression Scale; CPE= central nervous system penetration effectiveness score; EFV= Efavirenz; PAOFI=Patient Assessment of Own Functioning Inventory; IHDS=International HIV Dementia Scale; SD=standard deviation; TDF= Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Group differences on continuous variables (normally distributed) were examined using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and group differences on categorical variables were examined using chi-square analysis.

subtype only available on N=70.

Patterns of Depression Changes in the Overall Sample after ART Initiation

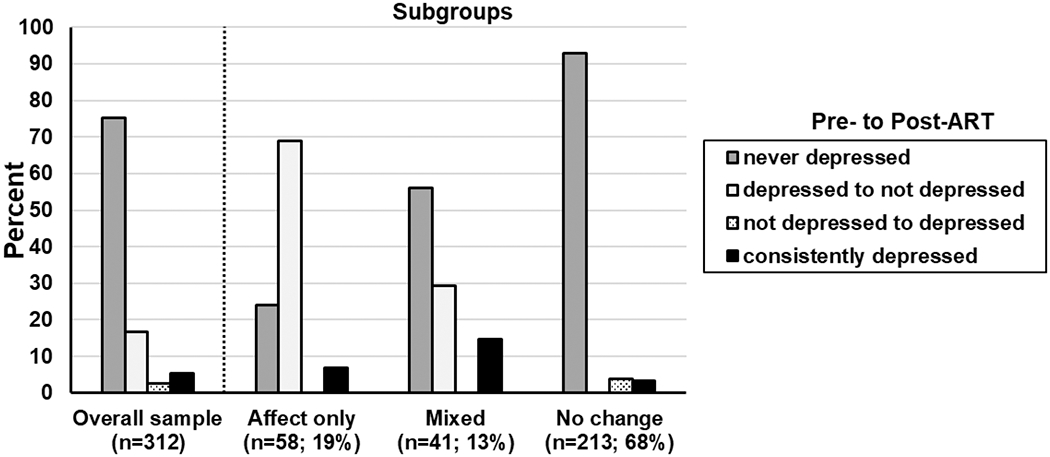

Of the 312 PWH, 75% were never depressed, 17% were depressed pre-ART but not post-ART, 3% were not depressed pre-ART but depressed post-ART, and 5% were depressed both pre- and post-ART (Figure 1). The four groups differed by sex, body mass index (BMI), alcohol, narcotic use, hypertension, PAOFI scores (higher=more subjective functional impairment), IHDS scores (lower=possible dementia) with trends observed with CD4 count and tobacco use (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Patterns of changes in depression in the overall sample and by subgroup.

Dimensional Changes in Depressive Symptoms after ART initiation

The three-class solution provided the best fit to the observed data in terms of entropy (3-class=0.83 vs. 2-class =0.81 and 4-class=0.80), AIC (3-class=4176 vs. 2-class =4214 and 4-class=4155), and BIC (3-class=4408 vs. 2-class=4368 and 4-class=4466) and was clinically interpretable. A Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test revealed that the 3-class model had a significantly better fit than the 2-class model (P<0.05) but not the 4-class model (P= 0.78). Subgroup 1 included 18.5% (n=58), subgroup 2 included 13% (n=41), and subgroup 3 included 68% (n=213) of the individuals.

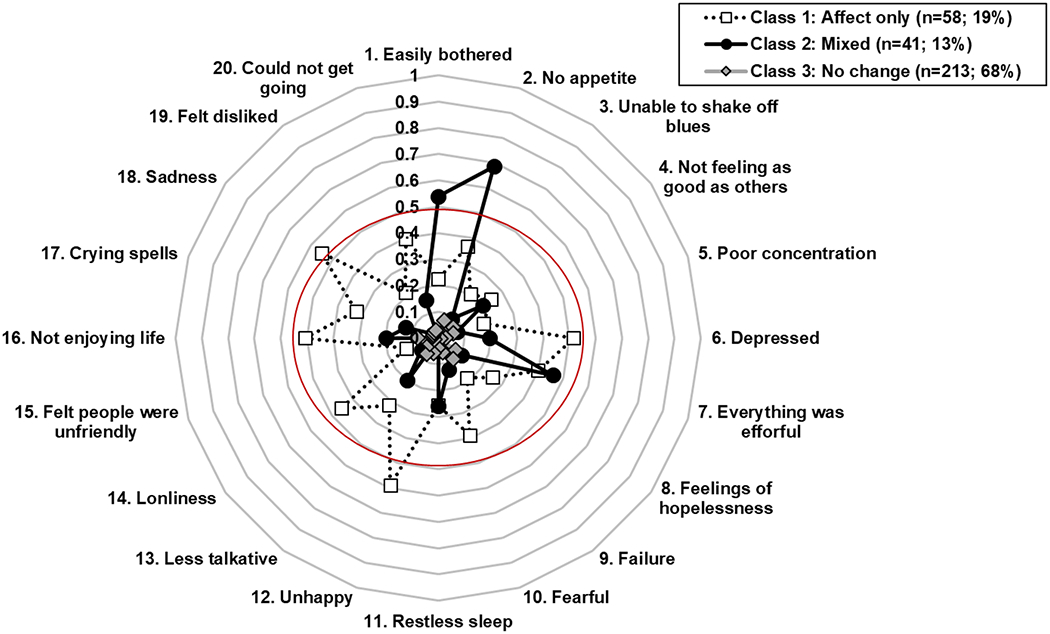

Figure 2 depicts the item-response probabilities for each subgroup. Responses where a group member was more likely to demonstrate clinically significant improvements on a specific CES-D item after ART would have values greater than 0.50. After ART, subgroup 1 individuals demonstrated less sadness, unhappiness, depression, and enjoying life more (affect-only change subgroup). Subgroup 2 individuals demonstrated less irritability, a better appetite, and not feeling that everything was an effort (mixed-symptom change subgroup). Subgroup 3 demonstrated no improvement in CES-D items (no-change subgroup).

Fig. 2.

Three-latent-class model of antiretroviral (ART)-related depressive symptom improvement. Probability of Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) item level symptom improvement for each subgroup.

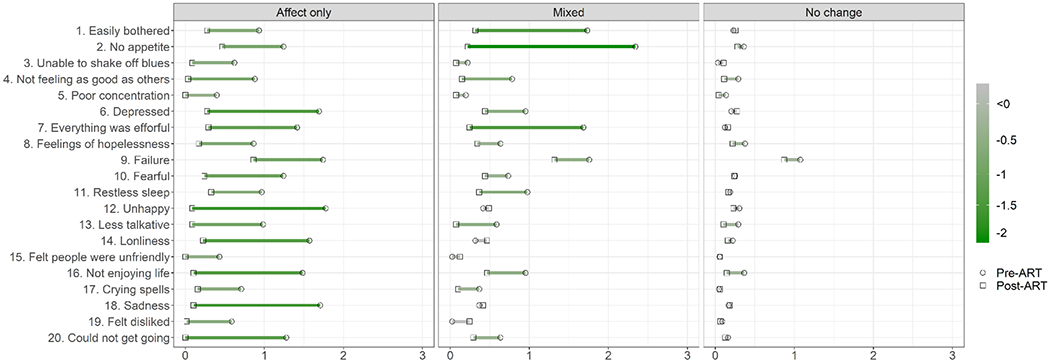

When the proportion of PWH meeting criteria for depression at both the pre-ART and post-ART visit was examined by subgroups (Figure 1), the affect-only change subgroup had the highest percent of PWH endorsing clinically significant depressive symptoms (76%) pre-ART followed by the mixed-symptom change subgroup (44%) and then the no-change subgroup (3%). Both the affect- and mixed-symptom-change subgroups demonstrated significant reductions in depressive symptoms from pre- to post-ART assessment. Figure 3 provides the average score for each CES-D item by subgroup to understand the degree of symptom severity pre-ART initiation and the degree of symptom change post-ART. The affect-only change subgroup was on average symptomatic pre-ART on several items that included mostly affect symptoms (e.g., depressed, feelings of failure and fearfulness, unhappy, sadness) and some somatic symptoms (appetite), and effort. The mixed-symptom change subgroup was on average symptomatic pre-ART on being easily bothered, having no appetite, lacking effort, and feelings of failure. Although the no-change subgroup had minimal depressive symptoms generally pre-ART, they were high on feelings of being a failure which remained high post-ART.

Fig. 3.

Average CES-D item scores for each subgroup pre- and post-antiretroviral (ART). Green corresponds to symptom improvement with ART and magenta with symptom exacerbation with ART.

Factors and CSF Markers Differing Across the Subgroups of Individuals showing Similar Changes in Depressive Symptoms after ART initiation

Subgroups

Table 2 provides socio-demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics as well as laboratory profiles (CD4 count, HIV RNA) by the three subgroups. Specifically, the mixed-symptom change subgroup had the highest proportion of smokers pre-ART, followed by the affect-only change subgroup and then the no-change subgroup (P’s<0.05). The mixed-symptom and affective symptom-only change subgroups had a higher percentage of PWH that were underweight, had higher PAOFI scores, and had higher log serum viral loads pre-ART compared to the no-change subgroup (P’s<0.05). The affect-only change subgroup had a higher percentage of females than the no-change subgroup (P=0.03). The mixed-symptom change subgroup trended to have lower IHDS scores than the no-change subgroup (P=0.06), and the mixed-symptom change and affective symptom-only change subgroups trended to have a higher percentage of PWH with hypertension than the no-change subgroup (P’s=0.05).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics in the overall sample and as a function of subgroup.

| Affect only (n=58; 19%) n (%) |

Mixed (n=41; 13%) n (%) |

No change (n=213; 68%) n (%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ART | ||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 36.9 (9.2) | 36.8 (9.8) | 35.0 (7.9) | 0.18 |

| Education, mean (SD) | 4.6 (3.4) | 5.4 (3.3) | 5.6 (3.2) | 0.13 |

| Female sex | 36 (62) | 22 (54) | 96 (45) | 0.05 |

| Married | 36 (62) | 28 (68) | 136 (64) | 0.81 |

| BMI | 22.2 (3.8) | 21.6 (4.0) | 22.2 (3.3) | 0.57 |

| Underweight | 9 (15) | 9 (22) | 9 (4) | <0.001 |

| Overweight/obese | 10 (17) | 6 (15) | 29 (14) | 0.79 |

| Tobacco use | 5 (9) | 11 (27) | 30 (14) | 0.04 |

| Alcohol use | 25 (43) | 18 (44) | 114 (53) | 0.25 |

| Narcotic use | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | 4 (2) | 0.55 |

| Hypertension | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.09 |

| High cholesterol | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 0.31 |

| PAOFI total, mean (SD) | 134.6 (25.6) | 147.8 (14.6) | 150.1 (15.7) | <0.001 |

| IHDS total, mean (SD) | 9.1 (1.9) | 8.6 (1.8) | 9.3 (1.8) | 0.08 |

| CD4 count, mean (SD) | 256.6 (160.8) | 180.2 (156.7) | 288.4 (165.3) | 0.001 |

| Log viral load (cp/ml) | 4.7 (1.0) | 4.8 (1.1) | 4.4 (0.9) | 0.03 |

| HIV subtype† | 0.36 | |||

| A1 | 7 (44) | 1 (17) | 22 (46) | |

| D | 9 (56) | 5 (83) | 26 (54) | |

| ART-medication initiated | ||||

| EFV | 54 (93) | 35 (85) | 176 (83) | 0.10 |

| TDF+3TC+EFV | 53 (91) | 35 (85) | 172 (81) | 0.12 |

| CPE, mean (SD) | 5.7 (1.4) | 5.5 (1.8) | 5.6 (2.0) | 0.77 |

| Post-ART | ||||

| Undetectable viral load (<40cp/ml) | 47 (82) | 35 (85) | 180 (85) | 0.83 |

| Δ Pre- to Post-ART, mean (SD) | ||||

| PAOFI total | −14.6 (23.0) | −1.9 (17.6) | −5.0 (12.6) | <0.001 |

| IHDS total | −0.6 (2.0) | −0.6 (2.2) | −0.8 (1.8) | 0.70 |

| BMI | 1.2 (2.5) | 1.2 (2.3) | 0.4 (1.9) | 0.01 |

| CD4 count | 163.3 (147.9) | 170.9 (183.2) | 133.9 (162.4) | 0.26 |

Note. ∆ = change values; 3TC=Lamivudine; BMI=body mass index; CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Depression Scale; CPE= central nervous system penetration effectiveness score; EFV= Efavirenz; PAOFI=Patient Assessment of Own Functioning Inventory; IHDS=International HIV Dementia Scale; TDF= Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Group differences on continuous variables (normally distributed) were examined using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and group differences on categorical variables were examined using chi-square analysis.

subtype only available on N=70.

There were also significant subgroup differences in pre- to post-ART changes in mean BMI and PAOFI scores. Specifically, the mixed-symptom and affective symptom-only change subgroups demonstrated greater increases in BMI and greater improvements in PAOFI scores than the no-change subgroup (P’s=0.05). As noted above, these two subgroups had a higher percentage of underweight individuals with higher PAOFI scores compared to the no-change subgroup. Thus, initiating ART appears to have normalized BMI and functional status in the mixed-symptom and affective symptom-only change subgroups.

Incorporating all of the factors that differed between the subgroups at P<0.10 into a single generalized logistic regression model indicated that the combination of the pre-ART variables that included PAOFI score, CD4 count, underweight BMI, hypertension, and female sex were significant predictors of post-ART subgroup membership (P’s<0.01).

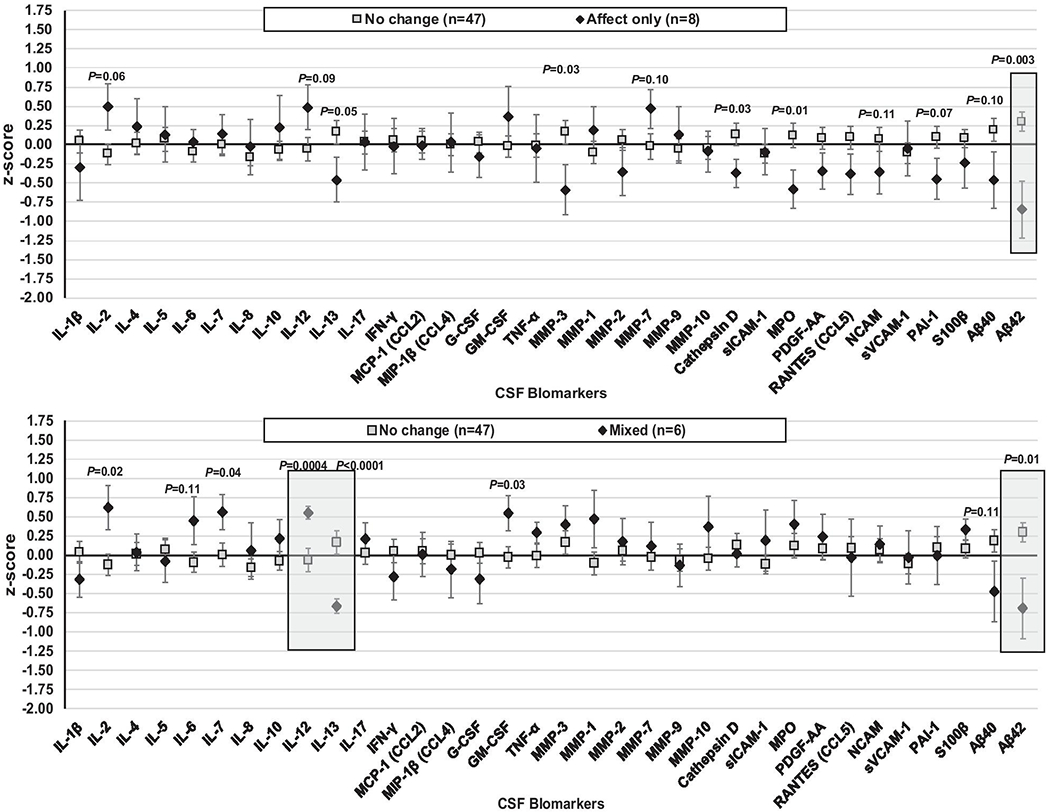

Following a false discovery rate (FDR) correction (Benjamini-Hochberg procedure; FDR set at 15%), significant subgroup differences emerged on three CSF biomarkers when comparing the mixed-symptom or affective-only change subgroups versus the no-change subgroup (Figure 4). The affect and mixed-symptom change subgroups had lower beta amyloid 42 (Aβ42) compared to the no-change group (P’s<0.05). The mixed-symptom change subgroup also demonstrated lower IL-13 and higher IL-12 than the no-change subgroup (P’s<0.001).

Fig. 4.

Pre-antiretroviral CSF estimated mean (standard error) biomarker levels (log-transformed and z-scored) showing significant differences between the subgroups demonstrating affect or somatic symptom improvement compared to the no-change subgroup. Note. Shaded regions meet statistical significance following a false discovery rate correction.

Discussion

Depression was prevalent in this ART-naïve, rural Ugandan cohort at a rate higher than HIV-uninfected individuals assessed at the same time (11%)(Vecchio et al, in press). The rates decreased following ART-initiation. After ART-initiation, a majority of the cohort showed no change in depression symptoms. Of those who showed improvement, there were distinct differences in the pattern of depression symptom changes, specifically with individuals tending to show either improved affective or improved mixed symptoms.

Overall, the prevalence of depression at baseline (22%) was consistent with other studies of PWH in sub-Saharan Africa and the United States (Asrat et al, 2020; Chibanda et al, 2016; Monahan et al, 2009; Rubin and Maki, 2019). At the start of HIV infection, high rates of depression are associated with delayed engagement in HIV care, internalized HIV-related stigma, reduced energy and substance abuse (Cholera et al, 2017; Mayston et al, 2015; Nash et al, 2016; Sudfeld et al, 2017). Here depression was more common in females and associated with alcohol use, low BMI, hypertension and lower cognitive function pre-ART. Most of these cases improved following ART, with a low rate of incidence while on study. The prevalence of depression after viral suppression (8%) approaches the estimated rate of depression of the general regional population (Bitew, 2014; Moledina et al, 2018) and was similar to or lower than HIV-uninfected individuals in Rakai assessed as part of this cohort (11%)(Vecchio et al, in press). Although the determinants of depression are multifactorial and vary substantially from one depressed individual to another, the demographic, behavioral and associated comorbidities seen here were consistent with previous research (Chibanda et al, 2016; Monahan et al, 2009; Nakimuli-Mpungu et al, 2012; Rubin and Maki, 2019).

Depression is a heterogeneous disorder manifested by a spectrum of emotional, cognitive, somatic, and interpersonal symptomatology (Goldberg, 2011). Variations in depressive symptomatology have been associated with sociodemographic and environmental factors (Kim et al, 2011). A unique aspect of this analysis is understanding changes in dimensions of depressive symptoms after ART in a cohort with low rates of confounding factors including cardiovascular risk factors, illicit substance use, and non-ART medications, in particular the meager rates of psychotropic medications such as antidepressants. Since the majority of the cohort were already depression free pre-ART, it was not surprising to find that most of the participants (68%) did not demonstrate improvement on CES-D items.

Eighty-five percent of the overall sample was on an EFV-based regimen. Here we found that depressive symptoms improved after initiating an EFV-based regimen which aligns with some previous studies in ART-naïve PWH (Robertson et al, 2019) and those in Uganda on EFV based regimens (Chang et al, 2018), but not all (Gazzard et al, 2010; Gutierrez et al, 2005; Marzolini et al, 2001; Silveira et al, 2012; Sumari-de Boer et al, 2018).

Those who did show improvement in affective or mixed symptoms had higher viral loads at baseline and were more likely to have gained weight and to demonstrate improved cognitive performance following ART initiation. Although general health improvement could account for some of these changes, lower levels of Aβ42 were also seen at baseline in both the affective and mixed symptom improvement subgroups compared to the no-change subgroup. Low Aβ42 levels are associated with an increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease (Fink et al, 2020; Vergallo et al, 2019). Thus, the finding of lower Aβ42 levels among the two subgroups demonstrating depression symptom improvement was unexpected and requires further examination in future studies.

The subgroup demonstrating mixed-symptom improvement also demonstrated lower IL-13 and higher IL-12 levels pre-ART compared with the no-change subgroup. Although studies much more strongly implicate IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and interferon-γ as mechanisms of mood dysregulation (Dantzer et al, 2008), IL-12 and IL-13 have also been found to be dysregulated in depression (Kohler et al, 2018) and IL-12 found to normalize after antidepressant treatment in people without HIV (Lee and Kim, 2006; Sutcigil et al, 2007). Additional work is needed to better understand the importance of these two markers in relation to depressive symptom improvement in PWH after ART initiation.

Study strengths include the longitudinal study design, examination of somatic and non-somatic depressive symptomatology, and minimal confounding from comorbidities that are common in large cohorts in the United States, including co-infections, illicit substance use, and non-ART medications with known adverse neuropsychiatric effects. However, there remain several study limitations, including that only a limited number of PWH in the overall analyses had pre-ART CSF levels to examine differences in biomarkers by subgroups. There are also limitations to the specific analysis model utilized, including multiple comparisons by subgroup for the exploratory secondary analysis. Finally, there are limitations to using the CES-D including its content redundancy within and across dimensions. For example, apathy includes two items (“I could not get going” and “I felt that everything I did was an effort”). Affective disturbance includes three items (“I was happy”, “I felt sad”, “I felt that I could not shake off the blues even with the help of my family and friends”). The redundancy leads to inflated scores at the group level and inconsistent sensitivity related to the psychometrics. This point warrants further consideration for the field of neuropsychiatry.

In conclusion, our study found heterogeneity in depression symptomatology in PWH followed for two years after initiation of ART. While most participants showed improvement in depression symptomatology, changes were heterogeneous, with some individuals improving primarily in affective and others in mixed symptoms. We also identified differences in CSF biomarkers between these groups. These differences need further investigation in larger cohorts as, if these differences are concerned, they may have therapeutic implications in that targeting different pathophysiologic mechanisms in each group may result in more effective treatment of their depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by the NIH (MH120693; MH099733, MH075673, MH080661, L30NS088658, NS065729-05S2) with additional funding from the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health. This study was also supported in part by the Division of Intramural Research, NIAID, NIH. Dr. Kevin Robertson who contributed to the conceptualization, conduction, supervision and analysis if this study sadly passed on before the final draft of the manuscript. We would also like to thank Dr. Raha Dastgheyb for helping us to create Figure 3 and Dr. Robert Paul for his insight into addressing the second round of revisions. We would also like to thank the participants and staff of the Rakai Health Sciences Program for their time and effort in the successful conduction of this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest/Financial disclosures

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abassi M, Morawski BM, Nakigozi G, Nakasujja N, Kong X, Meya DB, Robertson K, Gray R, Wawer MJ, Sacktor N, Boulware DR (2017). Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders in HIV-infected individuals in Rakai, Uganda. J Neurovirol 23: 369–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asrat B, Schneider M, Ambaw F, Lund C (2020). Effectiveness of psychological treatments for depressive symptoms among people living with HIV/AIDS in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 270: 174–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C, Dabis F, de Rekeneire N (2017). Prevalence and factors associated with depression in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 12: e0181960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, Turner BJ, Eggan F, Beckman R, Vitiello B, Morton SC, Orlando M, Bozzette SA, Ortiz-Barron L, Shapiro M (2001). Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58: 721–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitew T (2014). Prevalence and risk factors of depression in Ethiopia: a review. Ethiop J Health Sci 24: 161–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouillette MJ, Yuen T, Fellows LK, Cysique LA, Heaton RK, Mayo NE (2016). Identifying Neurocognitive Decline at 36 Months among HIV-Positive Participants in the CHARTER Cohort Using Group-Based Trajectory Analysis. PLoS One 11: e0155766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch AM, Wagener TL, Gregor KL, Ring KT, Borrelli B (2011). Utilizing reliable and clinically significant change criteria to assess for the development of depression during smoking cessation treatment: the importance of tracking idiographic change. Addict Behav 36: 1228–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JL, Tsai AC, Musinguzi N, Haberer JE, Bourn Y, Muzoora C, Bwana M, Martin JN, Hunt PW, Bangsberg DR, Siedner MJ (2018). Depression and Suicidal Ideation Among HIV-Infected Adults Receiving Efavirenz Versus Nevirapine in Uganda: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med 169: 146–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibanda D, Verhey R, Gibson LJ, Munetsi E, Machando D, Rusakaniko S, Munjoma R, Araya R, Weiss HA, Abas M (2016). Validation of screening tools for depression and anxiety disorders in a primary care population with high HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe. J Affect Disord 198: 50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholera R, Pence BW, Gaynes BN, Bassett J, Qangule N, Pettifor A, Macphail C, Miller WC (2017). Depression and Engagement in Care Among Newly Diagnosed HIV-Infected Adults in Johannesburg, South Africa. AIDS Behav 21: 1632–1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA, Burke-Miller JK, Steigman PJ, Schwartz RM, Hessol NA, Milam J, Merenstein DJ, Anastos K, Golub ET, Cohen MH (2018). Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Correlates of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders and Associations with HIV Risk Behaviors in a Multisite Cohort of Women Living with HIV. AIDS Behav. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cournos F, McKinnon K, Wainberg M (2005). What can mental health interventions contribute to the global struggle against HIV/AIDS? World Psychiatry 4: 135–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW(2008). From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 9: 46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do AN, Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, Beer L, Strine TW, Schulden JD, Fagan JL, Freedman MS, Skarbinski J (2014). Excess burden of depression among HIV-infected persons receiving medical care in the united states: data from the medical monitoring project and the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. PLoS One 9: e92842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton EF, Gravett RM, Tamhane AR, Mugavero MJ (2017). Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation and Changes in Self-Reported Depression. Clin Infect Dis 64: 1791–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink HA, Linskens EJ, Silverman PC, McCarten JR, Hemmy LS, Ouellette JM, Greer NL, Wilt TJ, Butler M (2020). Accuracy of Biomarker Testing for Neuropathologically Defined Alzheimer Disease in Older Adults With Dementia: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzard B, Balkin A, Hill A (2010). Analysis of neuropsychiatric adverse events during clinical trials of efavirenz in antiretroviral-naive patients: a systematic review. AIDS Rev 12: 67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Clark DC, Kupfer DJ (1993). Exactly what does the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale measure? J Psychiatr Res 27: 259–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JA, Grill M, Peterson J, Pilcher C, Lee E, Hecht FM, Fuchs D, Yiannoutsos CT, Price RW, Robertson K, Spudich S (2014). Longitudinal characterization of depression and mood states beginning in primary HIV infection. AIDS Behav 18: 1124–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D (2011). The heterogeneity of “major depression”. World Psychiatry 10: 226–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez F, Navarro A, Padilla S, Anton R, Masia M, Borras J, Martin-Hidalgo A (2005). Prediction of neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with long-term efavirenz therapy, using plasma drug level monitoring. Clin Infect Dis 41: 1648–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenaars JA, McCutcheon AL (2002). Applied latent class analysis. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth J, Colby D, Valcour V, Suttichom D, Spudich S, Ananworanich J, Prueksakaew P, Sailasuta N, Allen I, Jagodzinski LL, Slike B, Ochi D, Paul R, Group RSS (2017). Depression and Anxiety are Common in Acute HIV Infection and Associate with Plasma Immune Activation. AIDS Behav 21: 3238–3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P (1991). Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 59: 12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapfhammer HP (2006). Somatic symptoms in depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 8: 227–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemigisha E, Zanoni B, Bruce K, Menjivar R, Kadengye D, Atwine D, Rukundo GZ (2019). Prevalence of depressive symptoms and associated factors among adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in South Western Uganda. AIDS Care 31: 1297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, Decoster J, Huang CH, Chiriboga DA (2011). Race/ethnicity and the factor structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: a meta-analysis. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 17: 381–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CA, Freitas TH, Stubbs B, Maes M, Solmi M, Veronese N, de Andrade NQ, Morris G, Fernandes BS, Brunoni AR, Herrmann N, Raison CL, Miller BJ, Lanctot KL, Carvalho AF (2018). Peripheral Alterations in Cytokine and Chemokine Levels After Antidepressant Drug Treatment for Major Depressive Disorder: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mol Neurobiol 55: 4195–4206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KM, Kim YK (2006). The role of IL-12 and TGF-beta1 in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder. Int Immunopharmacol 6: 1298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne-Goehler J, Kakuhikire B, Abaasabyoona S, Barnighausen TW, Okello S, Tsai AC, Siedner MJ (2019). Depressive Symptoms Before and After Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation Among Older-Aged Individuals in Rural Uganda. AIDS Behav 23: 564–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzolini C, Telenti A, Decosterd LA, Greub G, Biollaz J, Buclin T (2001). Efavirenz plasma levels can predict treatment failure and central nervous system side effects in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 15: 71–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayston R, Patel V, Abas M, Korgaonkar P, Paranjape R, Rodrigues S, Prince M (2015). Determinants of common mental disorder, alcohol use disorder and cognitive morbidity among people coming for HIV testing in Goa, India. Trop Med Int Health 20: 397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moledina SM, Bhimji KM, Manji KP (2018). Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depression in an Asian Community in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Psychiatry J 2018: 9548471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan PO, Shacham E, Reece M, Kroenke K, Ong’or WO, Omollo O, Yebei VN, Ojwang C (2009). Validity/reliability of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 depression scales among adults living with HIV/AIDS in western Kenya. J Gen Intern Med 24: 189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakasujja N, Skolasky RL, Musisi S, Allebeck P, Robertson K, Ronald A, Katabira E, Clifford DB, Sacktor N (2010). Depression symptoms and cognitive function among individuals with advanced HIV infection initiating HAART in Uganda. BMC Psychiatry 10: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Bass JK, Alexandre P, Mills EJ, Musisi S, Ram M, Katabira E, Nachega JB (2012). Depression, alcohol use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS Behav 16: 2101–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash D, Tymejczyk O, Gadisa T, Kulkarni SG, Hoffman S, Yigzaw M, Elul B, Remien RH, Lahuerta M, Daba S, El Sadr W, Melaku Z (2016). Factors associated with initiation of antiretroviral therapy in the advanced stages of HIV infection in six Ethiopian HIV clinics, 2012 to 2013. J Int AIDS Soc 19: 20637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW(2003). Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 41: 582–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M, Burnam MA, Beckman R, Morton SC, London AS, Bing EG, Fleishman JA (2002). Re-estimating the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a nationally representative sample of persons receiving care for HIV: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 11: 75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1: 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson-Vejlgaard R, Dawes S, Heaton RK, Bell MD (2009). Validity of cognitive complaints in substance-abusing patients and non-clinical controls: the Patient’s Assessment of Own Functioning Inventory (PAOFI). Psychiatry Res 169: 70–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson KR, Jiang H, Kumwenda J, Supparatpinyo K, Marra CM, Berzins B, Hakim J, Sacktor N, Campbell TB, Schouten J, Mollan K, Tripathy S, Kumarasamy N, La Rosa A, Santos B, Silva MT, Kanyama C, Firhnhaber C, Murphy R, Hall C, Marcus C, Naini L, Masih R, Hosseinipour MC, Mngqibisa R, Badal-Faesen S, Yosief S, Vecchio A, Nair A, Group ACT (2019). Human Immunodeficiency Virus-associated Neurocognitive Impairment in Diverse Resource-limited Settings. Clin Infect Dis 68: 1733–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LH, Maki PM (2019). HIV, Depression, and Cognitive Impairment in the Era of Effective Antiretroviral Therapy. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LH, Saylor D, Nakigozi G, Nakasujja N, Robertson K, Kisakye A, Batte J, Mayanja R, Anok A, Lofgren SM, Boulware DR, Dastgheyb R, Reynolds SJ, Quinn TC, Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Sacktor N (2019). Heterogeneity in neurocognitive change trajectories among people with HIV starting antiretroviral therapy in Rakai, Uganda. J Neurovirol 25: 800–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacktor NC, Wong M, Nakasujja N, Skolasky RL, Selnes OA, Musisi S, Robertson K, McArthur JC, Ronald A, Katabira E (2005). The International HIV Dementia Scale: a new rapid screening test for HIV dementia. AIDS 19: 1367–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira MP, Guttier MC, Pinheiro CA, Pereira TV, Cruzeiro AL, Moreira LB (2012). Depressive symptoms in HIV-infected patients treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. Braz J Psychiatry 34: 162–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley L, Kellermanns FW, Zellweger TM (2017). Latent profile analysis: understanding family firm profiles. Family Business Review 30: 84–102. [Google Scholar]

- Sudfeld CR, Kaaya S, Gunaratna NS, Mugusi F, Fawzi WW, Aboud S, Smith Fawzi MC (2017). Depression at antiretroviral therapy initiation and clinical outcomes among a cohort of Tanzanian women living with HIV. AIDS 31: 263–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumari-de Boer M, Schellekens A, Duinmaijer A, Lalashowi JM, Swai HJ, de Mast Q, van der Ven A, Kinabo G (2018). Efavirenz is related to neuropsychiatric symptoms among adults, but not among adolescents living with human immunodeficiency virus in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Trap Med Int Health 23: 164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcigil L, Oktenli C, Musabak U, Bozkurt A, Cansever A, Uzun O, Sanisoglu SY, Yesilova Z, Ozmenler N, Ozsahin A, Sengul A (2007). Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine balance in major depression: effect of sertraline therapy. Clin Dev Immunol 2007: 76396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman GJ, Angelino AF, Hutton HE (2001). Psychiatric issues in the management of patients with HIV infection. JAMA 286: 2857–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triesman GJ, Angelino AF (2004). The Psychiatry of AIDS: A Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchio A, Robertson K, Saylor S, Nakigozi G, Nakasujja N, Kisakye A, Batte J, Mayanja R, Anok A, Reynolds SJ, Quinn TC, Gray R, Wawer MJ, Sacktor N, Rubin LH (in press). Neurocognitive effects of antiretroviral initiation among people living with HIV in rural Uganda JAIDS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergallo A, Megret L, Lista S, Cavedo E, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Vanmechelen E, De Vos A, Habert MO, Potier MC, Dubois B, Neri C, Hampel H, group IN-ps, Alzheimer Precision Medicine I (2019). Plasma amyloid beta 40/42 ratio predicts cerebral amyloidosis in cognitively normal individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 15: 764–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DW, Li Y, Dastgheyb R, Fitzgerald KC, Maki PM, Spence AB, Gustafson DR, Milam J, Sharma A, Adimora AA, Ofotokun I, Fischl MA, Konkle-Parker D, Weber KM, Xu Y, Rubin LH. Associations between Antiretroviral Drugs on Depressive Symptomatology in Homogenous Subgroups of Women with HIV. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2020. January 13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.