Key Points

Question

Are seizures more likely to occur during rewarming after hypothermia, and are they are associated with abnormal outcomes in asphyxiated neonates receiving hypothermia therapy?

Findings

This cohort study reports higher odds of electrographic seizure during the rewarming phase after hypothermia associated with increased relative risk of death or disability at 2-year follow-up.

Meaning

Study findings support the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society’s Guidelines for continuous electroencephalography monitoring of neonates with suspected perinatal asphyxia during hypothermia and further suggest that monitoring should be continued until normothermia is completed and seizure control is assured.

This cohort study evaluates whether electrographic seizures are more likely to occur during rewarming compared with the preceding period and whether they are associated with abnormal outcomes in asphyxiated neonates receiving hypothermia therapy.

Abstract

Importance

Compared with normothermia, hypothermia has been shown to reduce death or disability in neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy but data on seizures during rewarming and associated outcomes are scarce.

Objective

To determine whether electrographic seizures are more likely to occur during rewarming compared with the preceding period and whether they are associated with abnormal outcomes in asphyxiated neonates receiving hypothermia therapy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

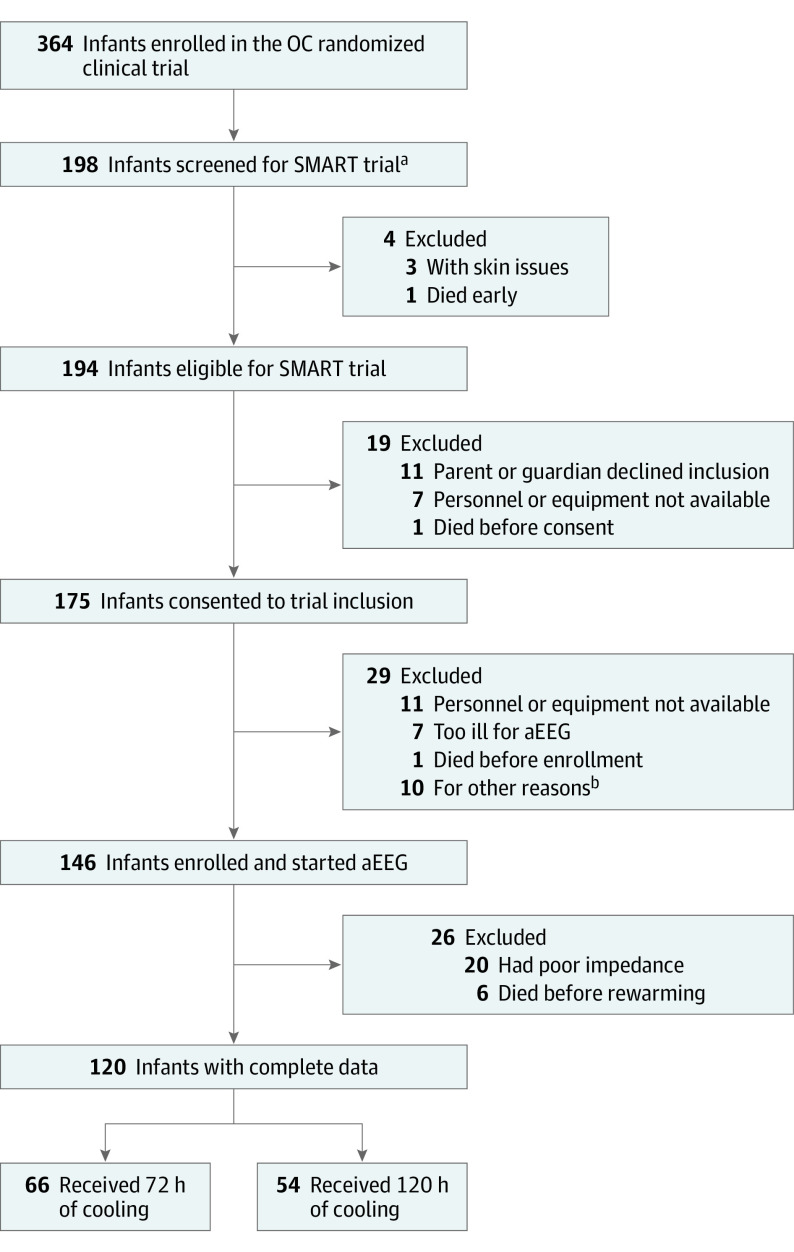

This prespecified nested cohort study of infants enrolled in the Optimizing Cooling (OC) multicenter Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network trial from December 2011 to December 2013 with 2 years’ follow-up randomized infants to either 72 hours of cooling (group A) or 120 hours (group B). The main trial included 364 infants. Of these, 194 were screened, 10 declined consent, and 120 met all predefined inclusion criteria. A total of 112 (90%) had complete data for death or disability. Data were analyzed from January 2018 to January 2020.

Interventions

Serial amplitude electroencephalography recordings were compared in the 12 hours prior and 12 hours during rewarming for evidence of electrographic seizure activity by 2 central amplitude-integrated electroencephalography readers blinded to treatment arm and rewarming epoch. Odds ratios and 95% CIs were evaluated following adjustment for center, prior seizures, depth of cooling, and encephalopathy severity.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the occurrence of electrographic seizures during rewarming initiated at 72 or 120 hours compared with the preceding 12-hour epoch. Secondary outcomes included death or moderate or severe disability at age 18 to 22 months. The hypothesis was that seizures during rewarming were associated with higher odds of abnormal neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Results

A total of 120 newborns (70 male [58%]) were enrolled (66 in group A and 54 in group B). The mean (SD) gestational age was 39 (1) weeks. There was excellent interrater agreement (κ, 0.99) in detection of seizures. More infants had electrographic seizures during the rewarming epoch compared with the preceding epoch (group A, 27% vs 14%; P = .001; group B, 21% vs 10%; P = .03). Adjusted odd ratios (95% CIs) for seizure frequency during rewarming were 2.7 (1.0-7.5) for group A and 3.2 (0.9-11.6) for group B. The composite death or moderate to severe disability outcome at 2 years was significantly higher in infants with electrographic seizures during rewarming (relative risk [95% CI], 1.7 [1.25-2.37]) after adjusting for baseline clinical encephalopathy and seizures as well as center.

Conclusions and Relevance

Findings that higher odds of electrographic seizures during rewarming are associated with death or disability at 2 years highlight the necessity of electroencephalography monitoring during rewarming in infants at risk.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01192776

Introduction

Neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) remains a major public health problem that afflicts millions of newborns worldwide, often resulting in cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, learning disabilities, and death.1,2 There is room for optimization of care, as 29% of infants currently continue to have abnormal outcomes at age 18 to 22 months despite hypothermia therapy.3,4

The rewarming phase is the least studied aspect of therapeutic hypothermia and could affect or predict outcomes. The rewarming regimen has been uniformly set in all neonatal hypothermia trials to increase the core body temperature by 0.5 °C per hour until normothermia is achieved despite the lack of empirical data to support such a regimen.5,6 Monitoring for seizures during rewarming can identify infants who have a more severe injury with impaired autoregulation leading to hemodynamic mismatch between oxygen delivery and metabolic demands.7,8,9 A number of small studies using electroencephalography (EEG) or amplitude integrated EEG (aEEG) have described late or rebound seizures during rewarming after 72 hours of hypothermia.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 To our knowledge, none of the prior large randomized trials of hypothermia for moderate or severe HIE included EEG or aEEG during the rewarming phase.18,19,20,21,22,23 The recent Optimizing Cooling (OC) trial was conducted at 18 centers of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network (NRN) to test the effect of longer (72 vs 120 hours) and deeper (32 °C vs 33.5 °C) hypothermia on outcomes.24 This Systematic Monitoring of EEG in Asphyxiated Newborns During Rewarming After Hypothermia Therapy (SMART) nested cohort study aims to assess whether electrographic seizures occur during rewarming at 72 or 120 hours and their association with neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years. The hypothesis for this study was that seizure activity increases during rewarming and is associated with higher odds of abnormal neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Methods

Study Design

SMART was a nested prespecified prospective study conducted by the NICHD from December 2011 to December 2013 within the OC for Neonatal HIE Randomized Clinical Trial.23,24 The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of the respective centers. Neonates older than 36 weeks’ gestation who were enrolled in OC were eligible after a separate written consent for SMART was obtained from parents or legal guardians. Criteria of the OC trial for eligibility and details of cooling and rewarming are as published.24 This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. Neonates were randomly assigned and stratified by center and encephalopathy severity in a 2 × 2 factorial design to a cooling depth of 33.5 °C or 32.0 °C and a cooling period of 72 hours or 120 hours. Cooling was achieved using the Blanketrol II Hyper-Hypothermia system (Cincinnati Sub-Zero). Rewarming was begun at either 72 or 120 hours (per OC randomization) after initiation of hypothermia using the same rewarming protocol whereby the set point of the automatic control of the cooling system was increased by 0.5 °C per hour until the esophageal temperature reached 36.5 °C for 4 consecutive hours. At that point, the esophageal temperature probe was removed and temperature was servo-controlled per standard care. Data on sex, race, and ethnicity were collected from parents or guardians by multiple choice as part of the study predefined characteristics. Data were analyzed from January 2018 to January 2020.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the change in electrographic seizures (Δ seizure) using aEEG analysis between the 2 consecutive 12-hour intervals prior to and during rewarming. The OC parent trial allowed the opportunity for the SMART study to evaluate 2 durations of cooling and to assess death or moderate or severe disability at age 18 to 22 months using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development III and the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) as in the OC trial.24 Other prespecified secondary outcomes included differences during rewarming in the seizure severity score and background patterns.

Intervention

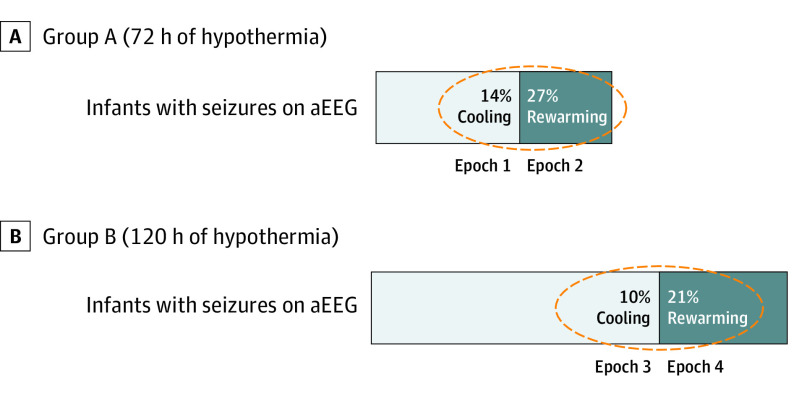

aEEG recordings were obtained using a BrainZ BRM3 Cerebral Function Monitor (Natus Medical). Serial aEEGs were recorded during hypothermia rewarming and focused on four 12-hour epochs before and after the initiation of rewarming (Figure 1). Epoch 1 was the pre-rewarming phase for group A (60 to 72 hours) and epoch 2 the rewarming phase for group A (72 to 84 hours). Epoch 3 was the pre-rewarming phase for group B (108 to 120 hours) and epoch 4 the rewarming phase for group B (120 to 132 hours).

Figure 1. Consortium Flowchart.

The Systematic Monitoring of EEG in Asphyxiated Newborns During Rewarming After Hypothermia Therapy (SMART) study started 1 year following the Optimizing Cooling (OC) trial initiation and 16 of 18 OC trial sites participated in SMART. A total of 120 infants (82%) met the predefined inclusion criteria of completed ambulatory electroencephalography (aEEG) during rewarming with good impedance and 112 (90%) had complete data for death or disability.

aThe SMART study period began in January 2012.

bOther reasons included parent withdrawal of consent, lack of access, clinical aEEG in place, and poor impedance.

Immediately after birth, the occurrence of seizures is primarily confounded by the severity of the asphyxia insult. We therefore targeted the epoch immediately preceding rewarming to facilitate comparison using similar durations and enable detection of the effect of increasing temperature.

Five disposable aEEG hydrogel electrodes were placed in the C3-P3 and C4-P4 locations on the respective left and right sides of the head with an additional ground lead starting within the first 6 hours. Electrodes were left in place and the impedance (less than 7.5μvolt) was checked daily by study research nurses. The aEEG recording was stored as a digital file for offline analysis. The bedside nurse recorded any procedures that could result in artifacts in the aEEG recording. To mask the central readers, the aEEG recordings were sent to the data coordinating center for deidentification of each of the epochs. Each aEEG was analyzed by 2 investigators (L.C.F. and A.P.) independently masked to treatment assignment and epochs.

Electrographic activity on the aEEG was confirmed using the raw EEG tracing showing simultaneous spike and wave, with a gradual buildup and then decline in frequency and amplitude of repetitive spikes or sharp waves. The frequency and severity of seizures was quantitated using a validated seizure score,12 which was calculated by the blinded central readers every hour as follows: 0 indicated no seizures; 1, 1 seizure of 3- to 10-minute duration; 2, more than 1 seizure and/or total duration less than 30 minutes (ie, no status epilepticus); 3, multiple seizures with overall cumulative duration greater than 30 minutes and/or status epilepticus. A seizure severity score (0 to 36) was calculated hourly for each predefined 12-hour monitoring epoch.

∆ Seizure was defined as the change in seizure severity score and calculated from the epochs before and during rewarming. If aEEG artifacts were present, epochs were normalized to a 12-hour duration and analyzed for comparison. Baseline seizures were defined a priori by the presence of any clinical or aEEG seizures prior to randomization at age 6 hours.

Data Categorization

The cross-cerebral (P3-P4) channel was evaluated using a combined approach of visual and offline digital analysis (BrainZ Analyze program). aEEG recordings with high impedance (greater than 7.5μvolt) or with a recording duration of less than 50% of the total epoch (less than 6 hours) were excluded from the analysis. The program provided raw EEG data and voltages of the aEEG band of activity allowing calculation of aEEG parameters (percent discontinuity, upper border, lower border, difference between upper and lower border voltage [span width], and sleep wake cycles).25 The predominant pattern was assigned using Hellström-Westas pattern classification.26 Differences in interpretation of seizures were adjudicated between the 2 central readers with oversight from the Research Triangle Institute (RTI) International, Raleigh, North Carolina, and the NRN Program Scientist. The adjudicated values were used when differences occurred. Adjustments for baseline seizure prevalence, severity of the clinical encephalopathy, and birth center were performed a priori based on the standard analysis protocol by RTI to control for modifiers that are known to influence the neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years.

Statistical Analysis

A sample of 100 or more infants with artifact-free tracings was selected a priori based on the knowledge that there is a lack of data for rewarming periods to estimate effect size. Kappa values were calculated for the 2 readers for seizure detection. Characteristics were compared for infants enrolled in the SMART study and compared with the remaining infants in the OC trial, using χ2 or exact tests for categorical variables, and t tests or Wilcoxon nonparametric tests for continuous variables. Prior to analysis, the data of different depths of hypothermia (33.5 °C vs 32.0 °C) were pooled based on the time of rewarming, as the rate of rewarming was the same for all infants. Models were additionally adjusted for depth of hypothermia (33.5 °C vs 32.0 °C) as a sensitivity analysis. Maternal and neonatal characteristics were compared for infants undergoing rewarming at 72 hours (group A) vs 120 hours (group B), using χ2 or exact tests for categorical variables and t tests or Wilcoxon nonparametric tests for continuous variables. The change in seizure frequency was explored using generalized linear mixed modeling, odds ratios (ORs), and 95% CIs adjusting for baseline seizure prevalence, severity of encephalopathy, and clinical center. Controlling for center differences was as per standard practice for the multicenter clinical studies to account for typically wide center differences in clinical practice and case mix.

Change in seizure severity score was explored using mixed modeling, adjusting for the same covariates as in seizure frequency. Relative risk for the secondary composite abnormal 2-year outcome was obtained using generalized estimating equation models with log link, adjusting for baseline levels of encephalopathy and anticonvulsant use as well as for the random effect of center.

Results

Of the 364 infants in the OC trial, 120 were enrolled in the SMART study from December 2011 to December 2014 (Figure 1). Infants were randomized to different durations of treatment (66 in group A and 54 in group B) and 112 (90%) completed 2 years of neurodevelopmental assessments. Maternal characteristics of the SMART patients were comparable with those in the overall OC cohort (Table 1) with the exception of fewer Black participants and more cord problems in the SMART cohort. Neonates enrolled in SMART were less likely to have pulmonary hypertension or liver dysfunction, had less severe HIE, and were less likely to require inotropes, nitric oxide, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Hospital mortality during the study period was also lower in those enrolled in the SMART study.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Systematic Monitoring of EEG in Asphyxiated Newborns During Rewarming After Hypothermia Therapy (SMART) Cohort.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A: 72 h of hypothermia (n = 66) | Group B: 120 h of hypothermia (n = 54) | Total (N = 120) | ||

| Maternal | ||||

| Raceb | .39 | |||

| Black | 15 (23) | 12 (23) | 27 (23) | |

| White | 47 (72) | 34 (65) | 81 (69) | |

| Otherc | 3 (5) | 6 (12) | 9 (7) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 28.6 (6.31) | 28.2 (7.43) | 28.4 (6.81) | .58 |

| Pregnancy complications | ||||

| Chronic hypertension | 13 (20) | 12 (23) | 25 (21) | .70 |

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 9 (14) | 4 (8) | 13 (11) | .38 |

| Intrapartum complications | ||||

| Fetal decelerations | 52 (79) | 43 (83) | 95 (81) | .60 |

| Cord problem | 11 (17) | 14 (26) | 25 (21) | .21 |

| Uterine rupture | 4 (6) | 2 (4) | 6 (5) | .69 |

| Maternal pyrexia (≥37.6 °C) | 5 (8) | 8 (15) | 13 (11) | .20 |

| Shoulder dystocia | 5 (8) | 6 (11) | 11 (9) | .54 |

| Maternal hemorrhage | 11 (17) | 6 (11) | 17 (14) | .39 |

| Emergency cesarean | 45 (68) | 30 (56) | 75 (63) | .15 |

| Neonatal | ||||

| Gestational age, mean (SD), wk | 38.5 (1.51) | 38.9 (1.22) | 38.7 (1.39) | .23 |

| Outborn | 44 (67) | 34 (63) | 78 (65) | .67 |

| Female | 30 (45) | 20 (37) | 50 (42) | .35 |

| Male | 36 (55) | 34 (63) | 70 (58) | .35 |

| Apgar score ≤5 | ||||

| 5 min | 58 (89) | 43 (81) | 101 (86) | .22 |

| 10 min | 38 (67) | 33 (70) | 71 (68) | .70 |

| Intubation in delivery room | 49 (74) | 39 (74) | 88 (74) | .94 |

| Resuscitation >10 min | 54 (82) | 47 (89) | 101 (85) | .30 |

| Time to respirations >10 min | 24 (39) | 19 (38) | 43 (39) | .89 |

| Cord blood, mean (SD) | ||||

| pH | 6.92 (0.21) | 6.97 (0.17) | 6.95 (0.20) | .26 |

| Base deficit | 17.9 (8.2) | 15.1 (5.6) | 16.4 (7.1) | .23 |

| Anticonvulsant | 34 (55) | 24 (46) | 58 (51) | .36 |

| Hypothermia (33.5 vs 32.0 °C) | 39 (59) | 28 (52) | 67 (56) | .46 |

| Encephalopathy | .62 | |||

| Moderate | 54 (82) | 46 (85) | 100 (83) | |

| Severe | 12 (18) | 8 (15) | 20 (17) | |

P values are from χ2 test or Kruskal-Wallis test. Fisher exact test was used when data were sparse.

Data on race were retrieved from the parent study to control for any differences.

Other included individuals reporting as follows: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and multiple race. These were consolidated to deidentify data due to small numbers.

The maternal and neonatal characteristics of neonates enrolled in the SMART study were comparable between the groups rewarmed at 72 hours (group A) and at 120 hours (group B) (eTable in the Supplement). There were similar allocations of infants with moderate vs severe encephalopathy as well as temperature depth in SMART, reflecting the parent OC randomization.

In this cohort study, 28 of 120 infants (23%) had electrographic seizures during rewarming. Agreement regarding the presence of seizures was high between the 2 central readers (κ, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-1.00). Of the 28 infants with electrographic seizures at rewarming, 6 (21%) had clinical manifestations requiring phenobarbital treatment. Of these, 19 (68%) had a prior seizure either before or during maintenance of hypothermia therapy. When compared with the directly preceding epoch, new onset of rewarming seizures were noted in 8 infants (12%) in group A and 7 (13%) in group B.

Within each group, more infants had seizures during the rewarming epoch compared with its immediately preceding epoch (group A epoch 2 vs 1, 17 [27%] vs 9 [14%]; group B epoch 4 vs 3, 11 [21%] vs 5 [10%]; P < .05) (Figure 2). The adjusted OR (95% CI) for having a seizure during rewarming was 2.7 (1.0-.5) for group A and 3.2 (0.9-11.6) for group B. Analysis of rewarming at 72 vs 120 hours showed no differences in number of infants with seizures (17 [27%] vs 11 [21%], respectively; P = .11) or seizure severity score (Table 2). These associations were not altered after adjusting models for the depth of hypothermia (33.5 vs 32.0 °C), nor did they occur at any particular time of the rewarming phase.

Figure 2. Epochs of Electroencephalography (EEG) Monitoring.

Boxes include the electrographic seizure occurrence epoch 1 (60-72 h), epoch 2 (72-84 h), epoch 3 (108-120 h), and epoch 4 (120-132 h).

Table 2. Primary Outcome: Seizures During Rewarming in Group A (72 Hours of Hypothermia) and Group B (120 Hours of Hypothermia).

| aEEG data | Group A: rewarming at 72 h (n = 66) | Group B: rewarming at 120 h (n = 54) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoch 1 | Epoch 2 | P value | Epoch 3 | Epoch 4 | P value | |

| Any detection of electrographic seizure frequency, No. (%) | 9 (14) | 17 (27) | NA | 5 (10) | 11 (21) | NA |

| Difference in seizure frequency, mean (SE), % | 12.7 (4.2) | NA | .008 | 11.5 (5.2) | NA | .03 |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) for detected seizure frequency during the rewarming vs prior epocha | 2.7 (1.0-7.5) | NA | .05 | 3.2 (0.9-11.6) | NA | .07 |

| Mean seizure severity score (95% CI) | 2.0 (0.8-4.6) | 2.8 (1.5-5.2) | NA | 0.9 (0.3-3.3) | 1.9 (0.8-4.3) | NA |

| Δ Seizure severity score (95% CI) | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) | NA | .22 | 0.5 (0.2-1.6) | NA | .23 |

Abbreviations: aEEG, amplitude integrated electroencephalography; NA, not applicable.

Seizure frequency was analyzed using mixed modeling and seizure severity score using generalized estimating equations with a negative binomial distribution function. The odds ratio and CIs for seizure frequency during rewarming were analyzed using generalized linear mixed modeling. All models were adjusted for baseline levels of encephalopathy and anticonvulsant use, as well as for the random effect of individual within center.

An abnormal composite outcome of death or disability at age 18 to 22 months occurred in 13 neonates (46%) who had seizures during rewarming compared with 20 (25%) without seizures at rewarming (P < .001). Death prior to 18 to 22 months occurred in 6 infants with seizures during rewarming and in 8 without rewarming seizures. Baseline characteristics of infants who had seizures during rewarming were similar to those of infants who had no seizures except for a higher incidence of outborn birth and abnormal background aEEG (Table 3). A suppressed background (burst suppression, low voltage, and flat tracing) occurred in 15 of the 28 infants who had seizures at rewarming vs 18 of 87 in the group that did not have seizures (OR, 5.9; 95% CI, 2.3-14.8; P < .001). Although there was no significant difference in the overall percentage of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) abnormalities, infants with rewarming seizures had a twice higher incidence of basal ganglia-thalamic vs white matter injury pattern compared with those without seizures at rewarming.

Table 3. Characteristics of Infants Who Had Seizures During Rewarming.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seizures at rewarming (n = 28) | No seizures with rewarming (n = 87) | ||

| Gestational age, mean (SD), wk | 38.6 (1.57) | 38.8 (1.34) | .61 |

| Outborn | 24 (86) | 50 (57) | .007 |

| Female | 14 (50) | 37 (39) | .31 |

| Male | 14 (50) | 53 (61) | .31 |

| Apgar score ≤5 | |||

| 5 min | 25 (93) | 72 (84) | .35 |

| 10 min | 18 (75) | 50 (67) | .44 |

| Intubation in delivery room | 23 (85) | 61 (70) | .14 |

| Resuscitation >10 min | 24 (89) | 73 (87) | .76 |

| Cord blood, mean (SD) | |||

| pH | 6.97 (0.22) | 6.93 (0.19) | .50 |

| Base deficit | 14.94 (5.67) | 16.81 (7.59) | .46 |

| Anticonvulsant administration (any seizures before 72 h) | 15 (58) | 41 (49) | .46 |

| Clinical encephalopathy | .12 | ||

| Moderate | 21 (75) | 76 (87) | |

| Severe | 7 (25) | 11 (13) | |

| Abnormal brain MRI, No./No. (%)b | 19/26 (73) | 57/82 (70) | .73 |

| White matter injury | 4/19 (21) | 29/57 (51) | |

| Basal ganglia, thalamus injury | 8/19 (42) | 10/57 (18) | |

| Cerebellar involvement | 2/19 (11) | 2/57 (4) | |

| Cerebral involvement | 4/19 (21) | 7/57 (12) | |

| Amplitude EEG | <.001b | ||

| Continuous pattern | 2 (7) | 56 (64) | |

| Discontinuous pattern | 9 (32) | 13 (15) | |

| Burst suppression | 2 (7) | 7 (8) | |

| Low voltage | 12 (43) | 10 (11) | |

| Flat tracing | 3 (11) | 1 (1) | |

| Composite, death or disability at age 18-22 mo | 13 (46) | 20 (25) | .001a |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | 1.72 (1.25-2.37) | NA | |

Abbreviations: EEG, electroencephalography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

P values are from χ2 test or Kruskal-Wallis test; Fisher exact test was used when data were sparse.

108 infants completed a brain MRI after the end of rewarming.

The composite death or disability outcome at age 18 to 22 months was different in infants who had seizures during rewarming compared with those who did not (relative risk, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.25-2.37) and remained significant even after adjusting for clinical encephalopathy and prior seizures needing anticonvulsants, as well as for any center association.

Discussion

This nested cohort of the OC trial provides the largest study to date to systematically assess electrographic seizures during the rewarming phase in hypothermia therapy in asphyxiated neonates. Key findings were higher odds of seizures during rewarming, which were associated with increased relative risk of death or disability at 2 years.

Although some of the prior randomized TH trials27,28 have included aEEG as part of their entry criteria, they did not use EEG during rewarming to allow direct comparisons with the current study findings. Isolated electrographic seizures are well described in neonates toward the end of the rewarming phase but do not provide a comparison group to differentiate the distinct association of increasing temperature from the association of the initial insult severity.10,29 Similar to our study findings, Thoresen11 reported electrographic seizures in 23% of infants during rewarming following whole body hypothermia for 72 hours. Another single-institution study using head cooling reported aEEG seizures during rewarming in 20% of infants.12 The current study further demonstrates that longer cooling to 120 hours did not reduce seizure frequency.

Early translational preclinical studies have demonstrated that initiating rewarming at 48 hours was associated with increased seizures, which prompted the 72-hour cooling period set for trials.30,31 Seizures were also reported in piglets with hypoxia ischemia following 24 hours of TH.32,33 Others subsequently described rebound seizure activity with spontaneous rewarming following 72 hours of TH.34 Recent studies of hypoxia ischemic swine models conducted after the clinical trials were completed confirmed that rewarming at a rate of 0.5 °C per hour following hypothermia was associated with apoptosis in the motor cortex and with neuronal death. These effects were exacerbated by faster rewarming.35,36 Rapid rewarming is associated with caspase cleavage and histological brain injury.34,37,38 In contrast, slower rewarming over 24 hours was associated with improved electrographic EEG power in a sheep model.38,39 Of note, the preclinical studies had different durations of TH, making it difficult to disentangle the effect of longer duration of neuroprotective therapy from the specific effects of the rate of temperature elevation during rewarming.38,40

Reperfusion injury after HIE is an evolving process that in severe cases can extend over days to weeks and manifests as seizures at the discontinuation of therapy and initiation of rewarming.31 Our study design comparing seizures immediately pre- and post-rewarming was selected to highlight any effect of increased temperature and to distinguish the effect of increased temperature from the severity of insult at birth, the seizure activity of which typically resolves within 48 hours.

MRI is a recognized surrogate marker of outcomes with well-defined HIE signature patterns of a basal ganglia–thalamic pattern that results from acute profound asphyxia and a watershed pattern occurring after partial prolonged asphyxia.41 Our finding of predominantly suppressed background EEG and basal ganglia–thalamic MRI injury patterns in those who had rewarming seizures suggest the presence of a severe insult at birth.

The mechanisms of the observed rewarming seizures are likely temperature dependent. Temperature increments during rewarming are associated with increased heart rate, cardiac output, and altered hemoglobin-oxygen affinity that can result in discordance between oxygen delivery and consumption.42 Increased metabolic demands have also been described in other models, such as postoperative rewarming following cardiac bypass surgery.43 Increased cerebral blood flow velocity and decreased internal jugular venous oxygen saturation were also reported in experimental cardiopulmonary bypass models indicating a discrepancy between blood flow and the metabolic demands associated with rapid rewarming.44 Multiple investigations have described impaired cerebral autoregulation during rewarming to be associated with MRI injury and abnormal outcomes at 2 years.9,45,46,47 Clinically, the increased metabolic demands and higher energy consumption during rewarming may exacerbate hypoglycemia and shifts in electrolytes that may alter seizure threshold.48 Additionally, cardiovascular instability has been described in reports of clinical rewarming,49 as well as decreased mean arterial blood pressure with rewarming, but in the absence of seizures preservation of cardiac output has been described through increased heart rate.50

We can only postulate about the underlying mechanisms behind the observed association with neurodevelopmental outcomes. This association is likely owing to a combination of overall seizure burden51 and that even small changes in temperature can have important biological effects on the integrity of the blood-brain barrier, hemodynamics, and neuronal viability.52

Only 21% of infants with electrographic seizures were clinically recognized, which indicates that a clinical diagnosis of seizures does not adequately reflect the seizure burden in newborns as only one-third of neonatal EEG seizures have clinical correlates.53,54 aEEG is useful, as it facilitates the detection of subclinical seizures and seizure trends over prolonged periods of monitoring.55,56 Findings underscore the necessity of either continuous EEG or aEEG monitoring during rewarming as most seizures detected were subclinical and would have be missed otherwise. The low-voltage span and discontinuous patterns observed in this cohort at 72 hours reflect the encephalopathy severity.17,57 Secondary aEEG analysis showed no significant effect of rewarming on background voltage activity congruent with other studies showing that a temperature above 32 °C does not influence these parameters.57,58

Limitations

This study has limitations. We acknowledge that continuous EEG monitoring is the criterion standard tool for detecting electrographic seizures.59,60,61 However, as demonstrated by Shah et al,62 the combination of a 2-channel aEEG with conventional EEG signal allows for the identification of most seizures in at-risk newborn infants. Therefore, aEEG combined with a raw EEG signal reading as performed in this study permits better seizure detection than aEEG alone, despite the possibility for underreporting brief or focal seizures. This does not confound the findings, as the same aEEG method was used before and during rewarming. The possibility of underreported seizures owing to a limited montage and the lower recruitment of the sickest unstable infants in SMART emphasizes the importance of performing EEG monitoring throughout the rewarming phase.59,63 Another limitation was the lack of hemodynamic assessments to confirm the underlying mechanisms of intensified seizures (eg, mismatch in oxygen delivery and consumption). Additionally, the rate of rewarming was not modified, so we cannot comment on its effect on seizures.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the largest multicenter study to date to address electrographic seizure burden during rewarming in association with neurodevelopmental outcomes. Strengths include the prospective study design, predefined outcomes, masked central aEEG readers with a high concordance rate in readings, and the standardized study protocols, including assessments at age 18 to 22 months by certified examiners masked to trial group assignment.

Study findings of higher odds of seizures during rewarming associated with higher risk of abnormal outcomes at age 18 to 22 months support the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society’s Guidelines of continuous electroencephalography monitoring of neonates with suspected perinatal asphyxia at high risk.13 In addition to the standard 72-hour duration of hypothermia, this study suggests that monitoring should be continued during rewarming until normothermia is completed and seizure control is assured.

eTable. Characteristics of SMART vs the Optimizing Cooling (OC) trial not in SMART

Members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network

References

- 1.Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Black RE; WHO Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group . WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. Lancet. 2005;365(9465):1147-1152. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71877-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawn J, Shibuya K, Stein C. No cry at birth: global estimates of intrapartum stillbirths and intrapartum-related neonatal deaths. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(6):409-417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shankaran S, Pappas A, McDonald SA, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network . Childhood outcomes after hypothermia for neonatal encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(22):2085-2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shankaran S, Natarajan G, Chalak L, Pappas A, McDonald SA, Laptook AR. Hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: NICHD Neonatal Research Network contribution to the field. Semin Perinatol. 2016;40(6):385-390. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins RD, Raju TN, Perlman J, et al. Hypothermia and perinatal asphyxia: executive summary of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop. J Pediatr. 2006;148(2):170-175. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins RD, Raju T, Edwards AD, et al. Hypothermia and other treatment options for neonatal encephalopathy: an executive summary of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD workshop. J Pediatr. 2011;159(5):851-858. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grigore AM, Murray CF, Ramakrishna H, Djaiani G. A core review of temperature regimens and neuroprotection during cardiopulmonary bypass: does rewarming rate matter? Anesth Analg. 2009;109(6):1741-1751. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c04fea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ueda Y, Suehiro E, Wei EP, Kontos HA, Povlishock JT. Uncomplicated rapid posthypothermic rewarming alters cerebrovascular responsiveness. Stroke. 2004;35(2):601-606. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000113693.56783.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton VJ, Gerner G, Cristofalo E, et al. A pilot cohort study of cerebral autoregulation and 2-year neurodevelopmental outcomes in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy who received therapeutic hypothermia. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:209. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0464-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Battin M, Bennet L, Gunn AJ. Rebound seizures during rewarming. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1369. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thoresen M. Supportive care during neuroprotective hypothermia in the term newborn: adverse effects and their prevention. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35(4):749-763, vii. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yap V, Engel M, Takenouchi T, Perlman JM. Seizures are common in term infants undergoing head cooling. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41(5):327-331. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shellhaas RA, Chang T, Tsuchida T, et al. The American Clinical Neurophysiology Society’s guideline on continuous electroencephalography monitoring in neonates. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;28(6):611-617. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e31823e96d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuchida TN, Wusthoff CJ, Shellhaas RA, et al. ; American Clinical Neurophysiology Society Critical Care Monitoring Committee . American Clinical Neurophysiology Society standardized EEG terminology and categorization for the description of continuous EEG monitoring in neonates: report of the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society critical care monitoring committee. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;30(2):161-173. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e3182872b24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah DK, Wusthoff CJ, Clarke P, et al. Electrographic seizures are associated with brain injury in newborns undergoing therapeutic hypothermia. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99(3):F219-F224. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glass HC, Wusthoff CJ, Shellhaas RA, et al. Risk factors for EEG seizures in neonates treated with hypothermia: a multicenter cohort study. Neurology. 2014;82(14):1239-1244. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen YJ, Chiang MC, Lin JJ, et al. Seizures severity during rewarming can predict seizure outcomes of infants with neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy following therapeutic hypothermia. Biomed J. 2020;43(3):285-292. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2020.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monod N, Pajot N, Guidasci S. The neonatal EEG: statistical studies and prognostic value in full-term and pre-term babies. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972;32(5):529-544. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90063-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe K, Miyazaki S, Hara K, Hakamada S. Behavioral state cycles, background EEGs and prognosis of newborns with perinatal hypoxia. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1980;49(5-6):618-625. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(80)90402-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burdjalov VF, Baumgart S, Spitzer AR. Cerebral function monitoring: a new scoring system for the evaluation of brain maturation in neonates. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):855-861. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hellström-Westas L, Rosén I. Electroencephalography and brain damage in preterm infants. Early Hum Dev. 2005;81(3):255-261. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2005.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellström-Westas L, Rosén I. Continuous brain-function monitoring: state of the art in clinical practice. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11(6):503-511. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Pappas A, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Effect of depth and duration of cooling on deaths in the NICU among neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2629-2639. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Pappas A, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Effect of depth and duration of cooling on death or disability at age 18 months among neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(1):57-67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sommers R, Tucker R, Harini C, Laptook AR. Neurological maturation of late preterm infants at 34 wk assessed by amplitude integrated electroencephalogram. Pediatr Res. 2013;74(6):705-711. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hellstrom-Westas L. Amplitude-integrated EEG classification and interpretation in preterm and term infants. NeoReviews. 2006;7(2):e76-e87. doi: 10.1542/neo.7-2-e76 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gluckman PD, Wyatt JS, Azzopardi D, et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9460):663-670. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17946-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azzopardi D, Brocklehurst P, Edwards D, et al. ; TOBY Study Group . The TOBY study. whole body hypothermia for the treatment of perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2008;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-8-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kendall GS, Mathieson S, Meek J, Rennie JM. Recooling for rebound seizures after rewarming in neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):e451-e455. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunn AJ, Battin M, Gluckman PD, Gunn TR, Bennet L. Therapeutic hypothermia: from lab to NICU. J Perinat Med. 2005;33(4):340-346. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2005.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunn AJ, Gunn TR. The ‘pharmacology’ of neuronal rescue with cerebral hypothermia. Early Hum Dev. 1998;53(1):19-35. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3782(98)00033-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwata O, Thornton JS, Sellwood MW, et al. Depth of delayed cooling alters neuroprotection pattern after hypoxia-ischemia. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(1):75-87. doi: 10.1002/ana.20528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunn AJ, Thoresen M. Animal studies of neonatal hypothermic neuroprotection have translated well in to practice. Resuscitation. 2015;97:88-90. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerrits LC, Battin MR, Bennet L, Gonzalez H, Gunn AJ. Epileptiform activity during rewarming from moderate cerebral hypothermia in the near-term fetal sheep. Pediatr Res. 2005;57(3):342-346. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000150801.61188.5F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang B, Armstrong JS, Reyes M, et al. White matter apoptosis is increased by delayed hypothermia and rewarming in a neonatal piglet model of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Neuroscience. 2016;316:296-310. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.12.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang B, Armstrong JS, Lee JH, et al. Rewarming from therapeutic hypothermia induces cortical neuron apoptosis in a swine model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35(5):781-793. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Draghi V, Wassink G, Zhou KQ, Bennet L, Gunn AJ, Davidson JO. Differential effects of slow rewarming after cerebral hypothermia on white matter recovery after global cerebral ischemia in near-term fetal sheep. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):10142. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46505-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davidson JO, Wassink G, Draghi V, Dhillon SK, Bennet L, Gunn AJ. Limited benefit of slow rewarming after cerebral hypothermia for global cerebral ischemia in near-term fetal sheep. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2019;39(11):2246-2257. doi: 10.1177/0271678X18791631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davidson JO, Battin M, Gunn AJ. Evidence that therapeutic hypothermia should be continued for 72 hours. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019;104(2):F225. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-315844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davies A, Wassink G, Bennet L, Gunn AJ, Davidson JO. Can we further optimize therapeutic hypothermia for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy? Neural Regen Res. 2019;14(10):1678-1683. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.257512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller SP, Ramaswamy V, Michelson D, et al. Patterns of brain injury in term neonatal encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2005;146(4):453-460. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gebauer CM, Knuepfer M, Robel-Tillig E, Pulzer F, Vogtmann C. Hemodynamics among neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy during whole-body hypothermia and passive rewarming. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):843-850. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Linden J, Ekroth R, Lincoln C, Pugsley W, Scallan M, Tydén H. Is cerebral blood flow/metabolic mismatch during rewarming a risk factor after profound hypothermic procedures in small children? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1989;3(3):209-215. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(89)90068-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enomoto S, Hindman BJ, Dexter F, Smith T, Cutkomp J. Rapid rewarming causes an increase in the cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen that is temporarily unmatched by cerebral blood flow. a study during cardiopulmonary bypass in rabbits. Anesthesiology. 1996;84(6):1392-1400. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199606000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Massaro AN, Govindan RB, Vezina G, et al. Impaired cerebral autoregulation and brain injury in newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy treated with hypothermia. J Neurophysiol. 2015;114(2):818-824. doi: 10.1152/jn.00353.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howlett JA, Northington FJ, Gilmore MM, et al. Cerebrovascular autoregulation and neurologic injury in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatr Res. 2013;74(5):525-535. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tekes A, Poretti A, Scheurkogel MM, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient scalars correlate with near-infrared spectroscopy markers of cerebrovascular autoregulation in neonates cooled for perinatal hypoxic-ischemic injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(1):188-193. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forni AA, Rocchio MA, Szumita PM, Anger KE, Avery KR, Scirica BM. Evaluation of glucose management during therapeutic hypothermia at a tertiary academic medical center. Resuscitation. 2015;89:64-69. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thoresen M, Whitelaw A. Cardiovascular changes during mild therapeutic hypothermia and rewarming in infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 1):92-99. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu TW, Tamrazi B, Soleymani S, Seri I, Noori S. Hemodynamic changes during rewarming phase of whole-body hypothermia therapy in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2018;197:68-74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kharoshankaya L, Stevenson NJ, Livingstone V, et al. Seizure burden and neurodevelopmental outcome in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(12):1242-1248. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laptook A. The importance of temperature on the neurovascular unit. Early Hum Dev. 2014;90(10):713-717. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shellhaas RA, Soaita AI, Clancy RR. Sensitivity of amplitude-integrated electroencephalography for neonatal seizure detection. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):770-777. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shellhaas RA, Gallagher PR, Clancy RR. Assessment of neonatal electroencephalography (EEG) background by conventional and two amplitude-integrated EEG classification systems. J Pediatr. 2008;153(3):369-374. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toet MC, van der Meij W, de Vries LS, Uiterwaal CS, van Huffelen KC. Comparison between simultaneously recorded amplitude integrated electroencephalogram (cerebral function monitor) and standard electroencephalogram in neonates. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5):772-779. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shalak LF, Laptook AR, Velaphi SC, Perlman JM. Amplitude-integrated electroencephalography coupled with an early neurologic examination enhances prediction of term infants at risk for persistent encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):351-357. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burnsed J, Quigg M, Zanelli S, Goodkin HP. Clinical severity, rather than body temperature, during the rewarming phase of therapeutic hypothermia affect quantitative EEG in neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;28(1):10-14. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e318205134b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Horan M, Azzopardi D, Edwards AD, Firmin RK, Field D. Lack of influence of mild hypothermia on amplitude integrated-electroencephalography in neonates receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(2):69-75. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rennie JM, de Vries LS, Blennow M, et al. Characterisation of neonatal seizures and their treatment using continuous EEG monitoring: a multicentre experience. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019;104(5):F493-F501. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-315624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murray DM, Boylan GB, Ali I, Ryan CA, Murphy BP, Connolly S. Defining the gap between electrographic seizure burden, clinical expression and staff recognition of neonatal seizures. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93(3):F187-F191. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.086314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boylan GB, Rennie JM, Pressler RM, Wilson G, Morton M, Binnie CD. Phenobarbitone, neonatal seizures, and video-EEG. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;86(3):F165-F170. doi: 10.1136/fn.86.3.F165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shah DK, Mackay MT, Lavery S, et al. Accuracy of bedside electroencephalographic monitoring in comparison with simultaneous continuous conventional electroencephalography for seizure detection in term infants. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):1146-1154. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wusthoff CJ, Shellhaas RA, Clancy RR. Limitations of single-channel EEG on the forehead for neonatal seizure detection. J Perinatol. 2009;29(3):237-242. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Characteristics of SMART vs the Optimizing Cooling (OC) trial not in SMART

Members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network