This systematic review and meta-analysis investigates the association of behavioral interventions with development of social functioning and social cognitive skills among children and adolescents with social deficits.

Key Points

Question

Are behavioral interventions associated with improvement in social function and social cognition among children and adolescents experiencing social challenges?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 2163 participants in 33 randomized clinical trials, significantly greater gains in social function and social cognition were found among children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental or mental health diagnoses who received behavioral intervention than among comparator control groups.

Meaning

The findings suggest that children and adolescents with social deficits may benefit from social skills training regardless of their neurodevelopmental or mental health diagnosis.

Abstract

Importance

Social deficits are a common and disabling feature of many pediatric disorders; however, whether behavioral interventions are associated with benefits for children and adolescents with social deficits is poorly understood.

Objective

To assess whether behavioral interventions in children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental or mental health disorders are associated with improvements in social function and social cognition, and whether patient, intervention, and methodological characteristics moderate the association.

Data Sources

For this systematic review and meta-analysis, the PsycINFO, MEDLINE, and PubMed electronic databases were searched in December 2020 for randomized clinical trials published from database inception to December 1, 2020, including terms related to neurodevelopmental or mental health disorders, social behavior, randomized clinical trials, and children and adolescents. Data were analyzed in January 2021.

Study Selection

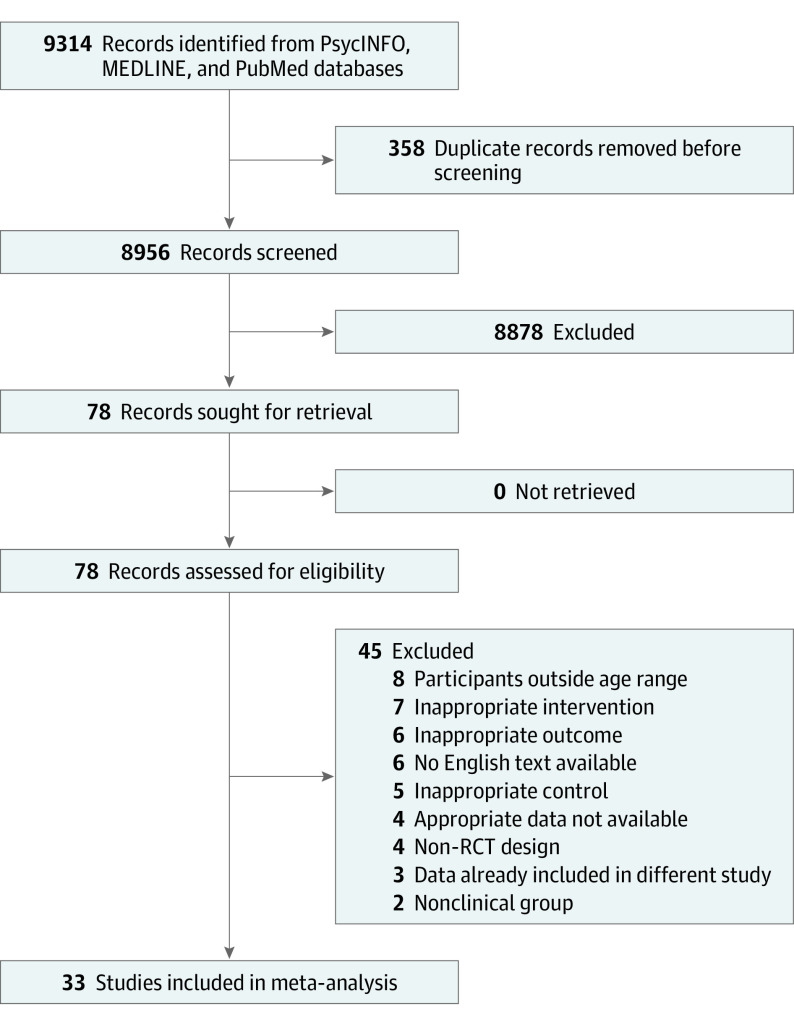

Randomized clinical trials that enrolled participants aged 4 to 17 years with social deficits and examined the efficacy of a clinician-administered behavioral intervention targeting social functioning or social cognition were included. A total of 9314 records were identified, 78 full texts were assessed for eligibility, and 33 articles were included in the study; 31 of these reported social function outcomes and 12 reported social cognition outcomes.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Articles were reviewed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment for randomized clinical trials. Data were independently extracted and pooled using a weighted random-effects model.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome was the association of behavioral intervention with social function and social cognition. Hedges g was used to measure the standardized mean difference between intervention and control groups. Standardized effect sizes were calculated for the intervention group vs the comparison group for each trial.

Results

A total of 31 trials including 2131 participants (1711 [80%] male; 420 [20%] female; mean [SD] age, 10.8 [2.2] years) with neurodevelopmental or mental health disorders (autism spectrum disorder [ASD] [n = 23], attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [n = 4], other conditions associated with social deficits [n = 4]) were analyzed to examine differences in social function between the intervention and control groups. Significantly greater gains in social function were found among participants who received an intervention than among the control groups (Hedges g, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.40-0.83; P < .001). The type of control condition (wait list vs active control vs treatment as usual) was a significant moderator of effect size (Q2, 7.11; P = .03). Twelve studies including 487 individuals with ASD (48 [10%] female; 439 [90%] male; mean [SD] age, 10.4 [1.7] years) were analyzed to examine differences in social cognition between intervention and control groups. The overall mean weighted effect was significant (Hedges g, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.39-0.96; P < .001), indicating the treatment groups had better performance on social cognitive tasks.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, significantly greater gains in social function and social cognition were reported among children and adolescents who received behavioral interventions for social deficits compared with participants receiving the control conditions. These findings suggest that children and adolescents with social deficits might benefit from social skills training regardless of their specific neurodevelopmental or mental health diagnosis.

Introduction

Humans are inherently social beings, and the quality of social relationships has a key role in many facets of children’s lives, including school performance,1 mental2 and physical health,3 and overall well-being.4 Participation in successful social relationships requires the development of social cognitive skills that enable children to dynamically interact with peers. These include interpreting facial expressions, gestures, and vocal intonation, which helps children to infer what others are thinking and feeling, understand pragmatic language, predict behavior, and modify their own behavior according to the social context.5 These skills emerge throughout childhood and adolescence as a result of a complex interplay between biological and environmental factors.5 Disruptions to these processes are associated with impairments in social competency, which may result in difficulties making and maintaining friendships, challenges at school, and strained familial relationships. Social deficits are associated with many neurodevelopmental disorders (eg, autism spectrum disorder [ASD]6 and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]7), mental health disorders (eg, social phobia8), and chronic illnesses (eg, cancer9). Global estimates suggest social deficits are experienced by up to 50% of children with neurodevelopmental disorders10 and 10% of children in the general population.11 Left unaddressed, social deficits are associated with poor functional outcomes and quality of life.12

Behavioral interventions are commonly used to improve social deficits. These interventions typically include didactic instruction, modeling social behavior, practicing skills with feedback, and reinforcement in socially decontextualized situations.13,14 Although preliminary evidence suggests that social interventions are effective,15,16 several meta-analyses have shown minimal to no clinical benefits.17,18,19,20 These discrepancies may be attributed to patient characteristics such as age, sex, and diagnosis or disorder17,21; intervention characteristics including intervention frequency22; and methodological considerations such as reporting source, control-group type, and outcome measures.23 Whereas the aforementioned studies suggested a benefit of social interventions in particular populations (eg, adolescents or individuals with specific neurodevelopmental disorders)16 or settings (eg, using a specific outcome measure21 or in a group format),21,24 to our knowledge, none considered transdiagnostic social interventions or explored the association of patient, intervention, or methodological characteristics with intervention efficacy.

To address these limitations, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis investigating whether behavioral interventions in children and adolescents with social challenges were associated with improvements in social outcomes. We conducted separate analyses for trials targeting social functioning and social cognitive skills. We examined whether patient characteristics (age, diagnosis, IQ, and sex), intervention characteristics (intervention length, mode of intervention delivery, and parent involvement), and methodological characteristics (time from treatment to follow-up, reporting source, type of control group, and risk of bias) moderated the association.

Methods

Search Methods

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched 3 online databases (PsycINFO, MEDLINE, and PubMed) in December 2020 for randomized clinical trials (RCTs) published from database inception to December 1, 2020. Search terms were optimized for each database and were related to the following topics: neurodevelopmental or mental health disorders, social behavior, RCTs, and children and adolescents (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The initial search yielded 9314 records (Figure 1). Duplicates were removed, and the remaining study titles were inspected by 4 authors (S.J.D., M.G., N.P.R., and A.K.C.) for relevance. Two authors (S.J.D. and M.G.) screened the abstracts of 8956 potentially eligible studies. After screening, 78 full articles were assessed for eligibility (M.G., N.P.R., and J.M.P.). The list of retained articles was settled by discussion and agreement of all authors. This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram.

RCT indicates randomized clinical trial.

Studies were deemed eligible if they (1) were an RCT, (2) only included participants aged 4 to 17 years, (3) examined the efficacy of a child-directed intervention delivered by a clinician that targeted social function or social cognition, (4) enrolled participants with social problems from clinical populations, (5) used a primary outcome with established reliability and validity, and (6) included means and SDs or data to calculate effect sizes of treatment and control groups. The decision to exclude school-delivered or community-delivered interventions and younger children was made to limit the heterogeneity of study populations and interventions. All included studies had received ethical approval and their participants had provided informed consent. A description of intervention characteristics is provided in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Outcome Measures

Social Function

Data reported from the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) or SRS–second edition (SRS-2) or the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS) or Social Skills Improvement System Rating Scale (SSIS-RS) were prioritized given the well-established psychometric properties of these scales.25,26 If more than 1 of these questionnaires was used, SRS or SRS-2 data were preferentially extracted. When data were not available for either instrument, a group consensus involving all authors was reached regarding selection of the most relevant measure. If both parent and teacher ratings were available, the former were selected because parents were the most frequent informants.

Social Cognition

Social cognitive outcomes were defined as task-based tools that directly assess socially related skills. When more than 1 social cognitive outcome was reported, the most relevant or psychometrically sound test was selected using the aforementioned group consensus.

For investigation of plausible moderators of the association of the intervention with outcomes, relevant characteristics of participants or interventions were extracted.27 These included age, IQ, proportion of male individuals, intervention length, time from treatment to follow-up, diagnosis (ASD, ADHD, or other), reporting source (parent or teacher), mode of intervention delivery (individual or group), substantial parental involvement (yes or no), and type of control (wait list, treatment as usual, or active control). If 2 control groups were used, the active-control condition was prioritized.

Risk of Bias

Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment for RCTs (eTable 3 in the Supplement).28 Because most studies were deemed to have at least 1 area of high risk of bias, studies were classified as higher risk or lower risk. Lower-risk studies had 1 area or less of high risk of bias, whereas higher-risk studies had 1 area of high risk of bias plus 1 or more areas of high risk of bias or some concern of bias.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed in January 2021 using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, version 3.0.29 The Hedges g statistic was used as a measure of the standardized mean difference between intervention and control groups.30 Standardized effect sizes were calculated for the intervention group vs the comparison group for each study. When raw data were not available, the effect size was computed from the available statistical information. A single effect size was calculated for each of the social function and social cognition domains to prevent repetition and statistical dependence.31 If required, data were transformed so that a positive effect size favored the intervention.

A weighted random-effects model was used to account for differences in the true effect size across studies.30 Heterogeneity was examined with forest plots and Q and I2 statistics.32 We also calculated τ2 and τ to examine the dispersion of underlying true effect sizes.30 If nontrivial (≥20%) effect-size heterogeneity was detected, we conducted random-effects metaregressions to investigate continuous moderators of the association between treatment and outcomes.33 Categorical moderator analyses were conducted according to the mixed-effects model to allow for differing variances across subgroups. If a metaregression identified significant moderator variables, these were further investigated with a meta-analysis.

Two meta-analytic techniques were used to evaluate the association of social interventions with social function and social cognition. For our primary approach, we used the pretest-posttest with control method, which takes baseline status into account and is the gold standard for intervention studies because it corrects for preexisting group differences despite random allocation.34,35,36 Because not all the studies had the test-retest reliability values required for pretest-posttest with control analyses, we used conservative correlation values of 0.75 (social function domain) and 0.6 (social cognition domain), which were based on a best-estimate calculation from available data. Sensitivity analyses using the posttest only with control method were also conducted.

Publication bias was examined with funnel plots, the Egger regression asymmetry test,37 and Duvall and Tweedie trim-and-fill technique.38 In addition, outlier analyses were performed by excluding studies in which the 95% CI was outside the aggregated 95% CI of all studies30 and recalculating the weighted mean effect size. Significance was set at 2-tailed P = .05.

Results

A total of 33 studies with 2163 participants (1743 [81%] male; 420 [19%] female; mean [SD] age, 10.7 [2.1] years) were included in this study. Characteristics of included studies16,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70 are outlined in the Table. Overall, 154 participants (7%) were lost to follow-up, with no differential dropout by treatment group.

Table. Summary of Study Characteristics.

| Study | Patient characteristics | Intervention characteristics | Methodological characteristics | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Intervention group, No. | Control group, No. | Age, ya | Male, % | IQ data | Format (duration, min) | Substantial parent involvement | Delivery agent | Control condition | Outcome type | Primary outcome measures | Outcome rater | ||

| Adams et al,51 2012 | ASD | 59 | 28 | 6-10 | 86 | Normal range | Up to 20 sessions, 3 × 1-h session/wk; 6-mo follow-up (1080) | N | Therapist (Ind) | TAU | SF | CCC2-Prag | Parent | |

| Andrews et al,66 2013 | ASD | 29 | 29 | 7-12 | 90 | IQ >79 | 5 wk, 5 × 2-h Sessions; 3-mo follow-up (600) | N | Therapist (G) | WL | SF | SCPQ | Parent | |

| Antshel and Remer,44 2003 | ADHD | 80 | 40 | 8-12 | 75 | NR | 8 wk; 3-mo Follow-up (720) | N | Therapist (G) | WL | SF | SSRS | Parent | |

| Baghdadli et al,65 2013 | ASD | 7 | 7 | Mean (SD), 0.7 (1.8) intervention group; 11.5 (1.2) control group | 100 | VIQ >70 | 6 mo (1800) | N | Therapist (G) | AC | SC | DANVA-2, adult and child faces | Parent | |

| Beaumont and Sofronoff,56 2008 | ASD | 26 | 23 | 7-11 | 90 | IQ >85 | 7 wk, 1 × 2-h Session/wk; 5-mo follow-up (495) | Y | Computer and small-group parent sessions (Tech) | WL | SF and SC | SSQ and FER from photos | Parent | |

| Begeer et al,60 2011 | ASD | 19 | 17 | 8-13 | 92 | FSIQ >70 | 16 wk (1440) | N | Therapist (G) | WL | SF and SC | CSBQ and ToM | Parent | |

| Begeer et al,61 2015 | ASD | 52 | 45 | 7-12 | 93 | VIQ within normal range | 8 wk, 8 × 1-h Sessions; 6-mo follow-up (480) | N | Therapist (G) | WL | SF and SC | SRS and ToM | Parent | |

| Choque Olsson et al,55 2017 | ASD | 150 | 146 | 8-17 | 70 | FSIQ >70 | 12 Weekly sessions; 3 -mo follow-up (876) | N | Therapist (G) | TAU | SF | SRS | Parent | |

| Dekker et al,52 2019 | ASD | 94 | 22 | 9-13 | 84 | IQ >80 | 15 Weekly 90-min sessions and 3 booster sessions of 90 min 2-6 mo later; 6-mo follow-up (1350) | Y | Therapist (G) | TAU | SF | SSRS | Parent | |

| Frankel et al,67 2010 | ASD | 33 | 35 | 2nd Grade to 5th grade | 85 | VIQ >60 | 12 Weekly 1-h sessions for parents and children (720) | Y | Therapist (G) | WL | SF | SSRS | Parent | |

| Fraser et al,39 2004 | Other (conduct problems, peer rejection) | 45 | 41 | 6-12 | 63 | NR | Total, 1680 min | Y | Therapist (G) | WL | SF | CCC and prosocial behavior | Teacher | |

| Hannesdottir et al,45 2017 | ADHD | 15 | 14 | 8-10 | 67 | IQ >70 | 5 wk, 2 × 2-h Sessions/wk (1200) | N | Therapist and computerized WM training (G) | WL | SF | SSRS | Parent | |

| Hopkins et al,49 2011 | ASD-HF | 13 | 11 | 6-15 | 90 | IQ >70 | 6 wk, ≤12 Sessions (210) | N | Computer (Tech) | AC | SF and SC | SSRS and FER from photos and drawings | Parent, blinded | |

| Jonsson et al,53 2019 | ASD | 23 | 27 | 8-17 | 70 | IQ >70 | 24 Weekly sessions (1800) | N | Therapist (G) | TAU | SF | SRS-2 | Parent | |

| Kasari et al,43 2012 | ASD | 44 | 15 | 6-11 | 90 | IQ >65 | 6 wk, 12 Sessions (240) | N | Therapist (Ind) | WL | SF | SNS | Peer | |

| Koenig et al,68 2010 | ASD | 23 | 18 | 8-11 | 68 | FSIQ >70 | 16 wk, 1 × 75-min Weekly session (1200) | N | Therapist (G) | WL | SF | PSI | Parent | |

| Koning et al,54 2013 | ASD | 7 | 8 | 10-12 | 100 | FSIQ >80 | 15 w, 1 × 2-h Weekly session (1800) | N | Therapist (G) | TAU | SF and SC | SRS and ER from facial expression, tone of voice, and gestures | Parent | |

| Laugeson et al,16 2009 | ASD | 17 | 16 | 13-17 | 85 | VIQ >70 | 12 w, 1 × 90-min Session/wk for parent and child groups (1080) | Y | Therapist (G) | WL | SF | SSRS | Parent | |

| Lopata et al,62 2010 | ASD | 18 | 18 | 7-12 | 94 | FSIQ >70 | 5 wk, 5 d/wk, 6 h/d (1750) | Y | Therapist (G) | WL | SF and SC | SRS and DANVA-2, child faces | Parent | |

| Matthews et al,57 2018 | ASD | 22 | 12 | 13-17 | 82 | FSIQ >70 | 14 × 90-min Weekly sessions (1260) | N | Therapist (G) | WL | SF | SRS-2 | Parent | |

| Michelson et al,47 1983 | Other (social maladjustment) | 14 | 14 | 8-12 | 100 | FSIQ >70 | 12 × 1-h Weekly sessions; 12-mo follow-up (720) | N | Therapist (G) | AC | SF | SSCE | Parent | |

| Pfiffner and McBurnett,46 1997b | ADHD | 18 | 9 | 8-10 | 70 | Attends regular school | 8 × Weekly sessions of 90 min (720) | Y | Therapist (G) | WL | SF | SSRS | Parent | |

| Rabin et al,69 2018 | ASD | 20 | 21 | 12-17 | 95 | FSIQ >70 | 14 wk, 1 × 90-min Session/wk; 16-wk follow-up (1260) | Y | Therapist (G) | WL | SF | SSIS-RS | Parent | |

| Rice et al,40 2015 | ASD | 16 | 15 | 5-11 | 90 | FSIQ >70 | 10 wk, 1 × 25-min Session/wk (250) | N | Computer program (Tech) | AC | SF and SC | SRS-2 and NEPSY II Affect Recognition | Teacher, blinded | |

| Schohl et al,70 2014 | ASD | 29 | 29 | 11-16 | 81 | VIQ >70 | 12 wk, 1 × 90-min Session/wk (1260) | Y | Therapist (G) | WL | SF | SRS | Parent | |

| Shum et al,58 2019 | ASD | 33 | 33 | 11-15 | 79 | VIQ >70 | 14 wk (1260) | Y | Therapist (G) | WL | SF | SRS-2 | Parent | |

| Solomon et al,63 2004 | ASD | 9 | 9 | 8-12 | 100 | FSIQ >75 | 20 wk, 1 × 90-min Session/wk (1800) | Y | Therapist (G) | WL | SC | DANVA-2, child faces | Parent | |

| Soorya et al,50 2015 | ASD | 35 | 32 | 8-11 | 83 | VIQ >70 | 12 × 90-min Weekly sessions (1080) | Y | Therapist (G) | AC | SF and SC | SF and SC composite scores | Parent for SF; trained raters (blinded) for SC | |

| Spence et al,48 2000 | Other (social phobia) | 36 | 14 | 7-14 | 62 | NR | 12 wk, 1-h Sessions plus 2 booster sessions (1080) | Y | Therapist (G) | WL | SF | SSQ | Parent | |

| Stichter et al,41 2018 | Other (social deficits including ASD) | 146 | 128 | 11.4-15.4 | 85 | FSIQ >70 | 32 Sessions (1440) | N | Therapist (G) | TAU | SF | SRS-2 | Teacher | |

| Storebø et al,42 2012 | ADHD | 28 | 27 | 8-12 | 71 | VIQ and PIQ >80 | 8 wk, 1 × 90-min Session/wk; 3-mo follow-up (720) | Y | Therapist (G) | TAU | SF | Conners-3, peer relations | Teacher | |

| Thomeer et al,59 2015 | ASD | 22 | 21 | 7-12 | 88 | IQ >70 | 12 wk, 2 × 90-min Session/wk; 5-wk follow-up (4320) | N | Therapist (Tech) | WL | SF and SC | SRS and Cambridge FER | Parent | |

| Thomeer et al,64 2019 | ASD | 28 | 29 | 7-12 | 84 | IQ >70 | 5 wk, 5 × 70-min Sessions/wk (8750) | Y | Therapist (G) | WL | SF and SC | SRS-2 and CASL, idiomatic language | Parent | |

Abbreviations: AC, active control; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; ASD-HF, high-functioning autism spectrum disorder; CASL, Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language; CCC, Carolina Child Checklist; CCC2-Prag, Children’s Communication Checklist-2, Pragmatics Rating Scale; Conners-3, Conners, third edition; CSBQ, Children’s Social Behavior Questionnaire; DANVA-2, Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy-2; ER, emotion recognition; FER, facial emotion recognition; FSIQ, full-scale IQ; G, group; Ind, individual; NEPSY II, Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment, second edition; NR, not reported; PIQ, performance IQ; PSI, Pro-Social Index of the Social Competence Inventory; SC, social cognition; SCPQ, Social Competence with Peers Questionnaire; SF, social function; SNS, Social Network Salience; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; SRS-2, SRS, second edition; SSCE, Consumer Evaluation of Social Skills; SSIS-RS, Social Skills Improvement System Rating Scale; SSQ, Social Skills Questionnaire; SSRS, Social Skills Rating System; TAU, treatment as usual; Tech, technologically delivered; ToM, theory of mind; VIQ, verbal IQ; WL, wait-list; WM, working memory.

Patient ages are presented as the range in years unless otherwise specified.

Only the parent-mediated arm of the intervention was included in the analysis.

Social Function Outcomes

Of the 33 articles, 31 studies16,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,64,66,67,68,69,70 with a total of 2131 participants (1711 [80%] male; 420 [20%] female; mean [SD] age, 10.8 [2.2] years) were included in the meta-analyses to examine the weighted mean difference in social function outcomes between the intervention and control groups; per-study sample sizes ranged from 15 to 296 participants (median [IQR], 50 [33-67] participants). Thirteen outcome measures were used across the studies. Most of the studies used parent-rated outcomes (26 studies16,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,64,66,67,68,69,70 [84%]), 4 (13%) reported teacher ratings,39,40,41,42 and 1 (3%) reported peer ratings.43 Most of the RCTs (23 studies16,40,43,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,64,66,67,68,69,70 [74%]) enrolled participants with a diagnosis of ASD or those who met cutoffs on validated ASD scales. The remainder enrolled participants with ADHD (4 RCTs [13%])42,44,45,46 or other conditions associated with social deficits (4 RCTs [13%]39,41,47,48). Most RCTs (20 studies16,39,43,44,45,46,48,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,64,66,67,68,69,70 [64%]) used a wait-list control, 4 (13%) used an active control,40,47,49,50 and 7 (23%) used a treatment-as-usual control condition.41,42,51,52,53,54,55 Twenty-one studies (68%) were classified as having a higher risk of bias16,40,41,44,45,47,48,49,50,51,53,55,56,57,60,61,62,67,68,69,70 and 10 (32%) as having a lower risk of bias.39,42,43,46,52,54,58,59,64,66

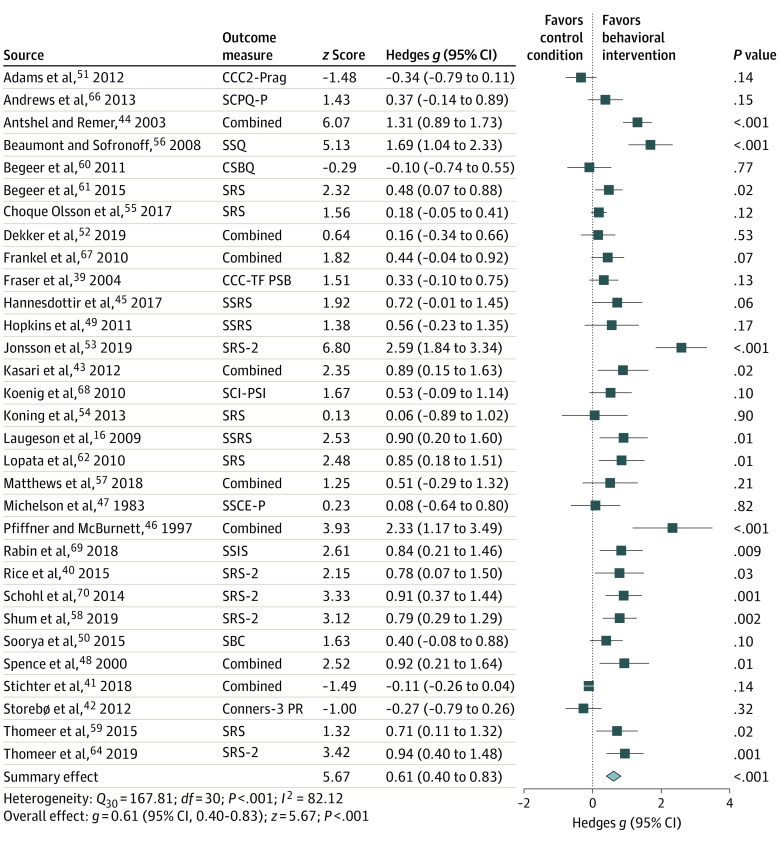

Among participants who received a behavioral intervention, significantly greater gains in social function were reported compared with participants who received the control conditions; the effect size was medium to large (Hedges g, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.40-0.83; P < .001) (Figure 2). Between-study heterogeneity was high (Q30, 167.81; P < .001; I2, 82.12; τ2, 0.27; τ, 0.52), with effect sizes (Hedges g) ranging from −0.34 (Adams et al51) to 2.59 (Jonsson et al53).

Figure 2. Forest Plot for Social Function Outcomes.

Effect sizes for maintenance of social function gains are shown. Squares indicate Hedges g, with horizontal lines indicating 95% CIs. The size of the squares indicates the relative weighting of each study in the meta-analysis. The diamond represents the overall effect size, with points of the diamond representing the 95% CI. CCC2-Prag indicates Children’s Communication Checklist, secondnd edition, Pragmatics Rating Scale; CCC-TF PSB, Carolina Child Checklist–Teacher Form, Prosocial Behavior Scale; Conners-3 PR, Conners, third edition, Peer Relations Scale; CSBQ, Children’s Social Behavior Questionnaire; SBC, Social Behavior Composite; SCI-PSI, Pro-Social Index of the Social Competence Inventory; SCPQ-P, Social Competence with Peers Questionnaire, parent report; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; SRS-2, SRS, second edition; SSCE-P, Consumer Evaluation of Social Skills, parent report; SSIS, Social Skills Improvement System; SSQ, Social Skills Questionnaire; and SSRS, Social Skills Rating System.

The Egger test indicated asymmetry of the funnel plot. The Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill procedure38 was used to provide the best estimate of an unbiased effect size. This procedure did not add any missing studies, and the effect size remained unchanged at 0.61. Six potential outliers were identified.41,44,46,51,53,56 Removing these outliers resulted in a medium effect size (Hedges g, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.35-0.62; P < .001) and significantly reduced heterogeneity (Q24, 36.09; P = .050). Sensitivity analyses using the posttest only with control data are shown in the eResults in the Supplement.

Participant age, IQ, proportion of male individuals, and intervention length did not moderate the mean effect size (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Diagnosis, reporting source, mode of intervention delivery, parent involvement, and risk of bias also did not moderate the treatment outcome. The type of control condition, however, significantly moderated the effect size (Q2, 7.11; P = .03), explaining 41% of the total between-study variance. The 20 RCTs that used a wait-list control16,39,43,44,45,46,48,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,64,66,67,68,69,70 demonstrated a medium to large mean effect size (Hedges g, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.57-0.95; P < .001) with a moderate amount of heterogeneity remaining between these studies (Q19, 40.33; P = .003; I2, 52.89; τ2, 0.10; τ, 0.31). Four studies40,47,49,50 using an active control revealed a medium effect size (Hedges g, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.12-0.76; P = .007) with minimal between-study heterogeneity (Q3, 1.95; P = .58; I2, 0.0). In contrast, the mean effect size was small for the 7 intervention trials using a treatment-as-usual comparator41,42,51,52,53,54,55 and was not statistically significant (Hedges g, 0.25; 95% CI, –0.17 to 0.68; P = .24). The associations of outliers with the type of control condition are reported in the eResults in the Supplement.

Maintenance of Gains in Social Function

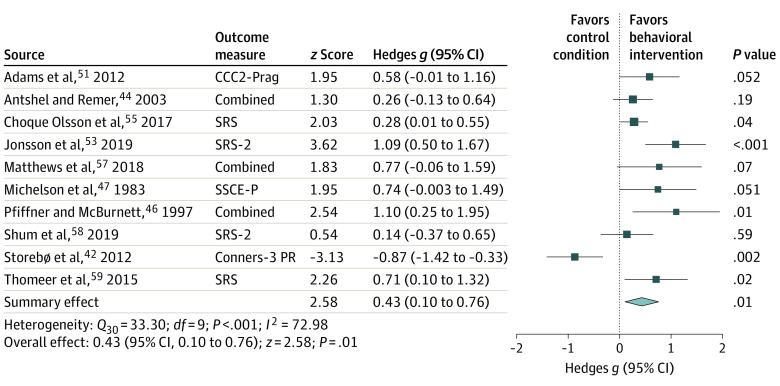

Ten RCTs provided sufficient data to assess the longer-term association of social skills treatment with social function.42,44,46,47,51,53,55,57,58,59 The total sample size of these studies was 806 participants, with a range of 27 to 296 participants per study. Follow-up periods varied from 5 weeks to 10 months after intervention (mean [SD], 17.8 [9.8] weeks). Six of these RCTs examined participants with ASD,51,53,55,57,58,59 3 examined participants with ADHD,42,44,46 and 1 assessed socially maladjusted boys.47 Five used a wait-list control,44,46,57,58,59 4 used a treatment-as-usual control condition,42,51,53,55 and 1 used an active control.47 Three of these studies examined interventions with substantial parent involvement.42,46,58 Data for parent ratings were extracted from all studies except 1, which reported teacher ratings.42

The results of the meta-analysis suggested that social interventions were associated with sustained benefits, with a significant small-to-medium mean effect size (Hedges g, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.10-0.76; P = .01) (Figure 3). We found high between-study heterogeneity (Q9, 33.30; P < .001; I2, 72.98; τ2, 0.19; τ, 0.43), with a Hedges g for individual studies ranging from −0.87 (Storebø et al42) to 1.10 (Pfiffner and McBurnett46).

Figure 3. Forest Plot for Maintenance of Social Function Gains.

Effect sizes for maintenance of social function gains are shown. Squares indicate Hedges g, with horizontal lines indicating 95% CIs. The size of the squares indicates the relative weighting of each study in the meta-analysis. The diamond represents the overall effect size, with points of the diamond representing the 95% CI. CCC2-Prag indicates Children’s Communication Checklist, second edition, Pragmatics Rating Scale; Conners-3 PR, Conners, third edition, Peer Relations Scale; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; SRS-2, SRS, second edition; and SSCE-P, Consumer Evaluation of Social Skills–parent report.

Although the Egger test did not indicate publication bias, visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested asymmetry. The Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill method revealed that 2 studies in favor of controls were likely missing, which would reduce the Hedges g from 0.43 to an imputed effect size estimate of 0.29. One potential outlier was detected and removed from the meta-analysis,42 subsequently resulting in a medium effect size (Hedges g, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.30-0.75; P < .001). There were no significant moderators of the treatment effect (eResults in the Supplement).

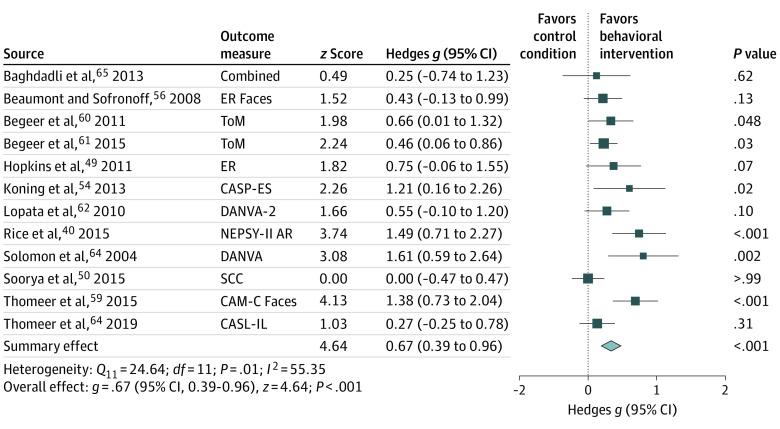

Social Cognition Outcomes

Twelve RCTs examined treatment effects on task-based social cognitive end points.40,49,50,54,56,59,60,61,62,63,64,65 The total sample size of these studies was 487 participants (439 [90%] male; 48 [10%] female; mean [SD] age, 10.4 [1.7] years), with a range of 14 to 97 participants per study. All 12 RCTs comprised participants with ASD. The social cognitive outcomes assessed were predominantly theory of mind and emotion recognition. Seven (58%) of these RCTs used a wait-list control,56,59,60,61,62,63,64 4 (33%) used an active control,40,49,50,65 and only 1 (8%) used a treatment-as-usual control condition.54 All but 3 of these RCTs59,64,65 were classified as having a higher risk of bias.

The overall mean weighted effect size was significant and medium to large in magnitude (Hedges g, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.39-0.96; P < .001), indicating better performance in treatment groups compared with control groups (Figure 4). Similar results were found using the data for posttest only with control (eResults in the Supplement). Examination of the individual studies revealed high consistency with positive effect sizes in 11 studies; a null effect size was detected in the study by Soorya et al.50 There was moderate study heterogeneity (Q11, 24.64; P = .01; I2, 55.35; τ2, 0.13; τ, 0.36).

Figure 4. Forest Plot for Social Cognition Outcomes.

Effect sizes for maintenance of social function gains are shown. Squares indicate Hedges g, with horizontal lines indicating 95% CIs. The size of the squares indicates the relative weighting of each study in the meta-analysis. The diamond represents the overall effect size, with points of the diamond representing the 95% CI. CAM-C Faces indicates Cambridge Mindreading Face-Voice Battery for Children–Faces scale; CASL-IL, Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language–Idiomatic Language subtest; CASP-ES, Child and Adolescent Social Perception Measure Emotion Score; DANVA, Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy; ER, emotion recognition; NEPSY-II AR, Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment, second edition, Affect Recognition subtest; SCC, Social Cognitive Composite; and ToM, theory of mind.

The Egger test suggested significant publication bias, and trim-and-fill analysis detected 1 hypothetical unpublished study favoring controls. After imputation of that study, the overall mean effect remained medium to large (Hedges g, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.34-0.91). Age, IQ, intervention length, proportion of males, type of control condition, parent involvement, and risk of bias were not associated with the effect size (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Behavioral interventions represent the most common treatment for social deficits in children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental diagnoses and mental health disorders.43 Despite the transdiagnostic nature of social deficits, evidence has focused on intervention effectiveness in specific populations or under specific study conditions. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we examined associations between behavioral interventions in children and adolescents with social challenges and improvements in social outcomes to guide delivery and improvement of this treatment approach.

Our analyses revealed several important and novel findings. First, social interventions were associated with greater and sustained gains in social function and improved social cognitive abilities compared with control conditions. These findings are consistent with those of previous research showing positive outcomes associated with social interventions among children with high-functioning ASD and learning disabilities.13,21,24,71 Gains in social function were maintained after treatment, suggesting that behavioral improvements may persist for at least several months after treatment completion.

Second, this study found that the neurobehavioral diagnoses of children and adolescents were not associated with intervention efficacy. To our knowledge, individual RCTs and meta-analyses of social interventions to date have largely been disorder specific, with most reporting positive effects of intervention in cohorts with ASD,21,24 emotional or behavioral disabilities,13 and learning disabilities.71 These findings contrast, however, with those of meta-analyses within the ADHD literature that report no benefits of behavioral interventions for social deficits.17,18 There are considerable differences in scope and methods between the current meta-analysis and meta-analyses within the ADHD literature, which likely account for the differences in the findings. For example, Morris et al17 explored peer social functioning in adolescents (Hedges g, −0.08; 95% CI, −0.34 to 0.19) and excluded younger children (aged <10 years), who may be more responsive to behavioral interventions given the plasticity of their developing brains; Storebø et al18 included a broader range of interventions including school-based programs and social skills training as an adjunct to pharmacological treatment. A strength of the current meta-analysis is that interventions were restricted to behavioral interventions delivered by a trained therapist, which controlled for some of the variability inherent in community-based programs. The results of the current study suggest that children with ADHD are as likely to benefit from behavioral intervention as are children with other neurobehavioral disorders and should be offered appropriate therapy if clinically indicated.

Third, we found that patient age, sex, and IQ were not associated with intervention efficacy. Consistent with this study’s results, previous studies have reported no association between sex14,24 or age13,72 and intervention success. Given that significant developmental changes occur throughout childhood and adolescence,5 pediatric interventions are typically designed within a developmental context and adapted for the age and cognitive skill level of the target group.55,73 This adaptation likely underlies the lack of association between age and IQ level with intervention efficacy and suggests that children with social deficits, regardless of IQ level, may benefit from developmentally appropriate intervention. However, of note, all studies in this meta-analysis included participants with an IQ greater than 70; therefore, the current findings cannot be generalized to individuals with intellectual disability.

Fourth, we found significantly larger effect sizes in studies using a wait-list control group compared with those using a treatment-as-usual control condition. This finding emphasizes that the type of control condition may be associated with intervention efficacy.23 Most of the studies (64% in the social function meta-analysis) included a wait-list control group, in which participants were assessed before and after a given period and received the protocolized intervention only after study completion.23 Seven studies in the social function meta-analysis (23%) included a treatment-as-usual control condition, which allowed comparative assessment of the association of treatment (therapeutic ingredients only) with outcomes in the context of standard care receipt. However, treatment-as-usual practices varied significantly across studies (eg, length and intensity of therapy), which not only affects effect sizes but also makes it difficult to combine results across studies.23 The discrepancy in effect sizes between wait-list and treatment-as-usual studies may be associated with the understated treatment effects that were found in studies with treatment-as-usual control conditions compared with those that had a wait-list condition. Accordingly, the effect sizes for studies with wait-list control designs may have been artificially inflated. A better understanding of the influence of control conditions on treatment effects should be a focus of future research to develop empirical guidelines that aim to optimize the design of future RCTs.74

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this meta-analysis include the use of robust methods, the large sample size, and a novel transdiagnostic approach. This study also has limitations. Descriptions of interventions were not sufficiently detailed to categorize interventions by type in a clinically meaningful way; therefore, the findings were collapsed across heterogeneous intervention types, which may have limited the generalizability of specific intervention characteristics. Because we limited included studies to those that had clinic-based populations with social deficits, the findings cannot be generalized to interventions delivered in schools or community settings. In addition, the study results must be interpreted within the context of possible study and publication biases. Although we included only RCTs, 21 studies (68%) were rated as having a higher risk of bias, most commonly owing to a lack of blinding for outcome assessors, which is difficult to avoid in studies of behavioral interventions. Of importance, the risk of study and publication bias did not significantly influence the results of the meta-analysis, suggesting that this study’s findings are robust.

Conclusions

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, significantly greater gains in social function and social cognition were reported among children and adolescents who received behavioral interventions for social deficits compared with participants receiving the control conditions. Patients may benefit from such interventions regardless of their individual characteristics. Publication of additional high-quality, low-risk RCTs across a broader range of disorders and intellectual functioning will enable a better understanding of the generalizability of interventions targeting social deficits.

eTable 1. Search Protocol

eTable 2. Intervention Characteristics of All Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis

eTable 3. Risk of Bias Summaries for eligible studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool

eTable 4. Moderators of Treatment Effect for Social Function Outcomes

eTable 5. Moderators of Treatment Effect for Social Cognition Outcome

eResults. Sensitivity Analyses

eReferences

References

- 1.McClelland MM, Morrison FJ, Holmes DL. Children at risk for early academic problems: the role of learning-related social skills. Early Child Res Q. 2000;15(3):307-329. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(00)00069-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segrin C. Social skills deficits associated with depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20(3):379-403. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00104-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(suppl):S54-S66. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goswami H. Social relationships and children’s subjective well-being. Soc Indic Res. 2012;107(3):575-588. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9864-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beauchamp MH, Anderson V. SOCIAL: an integrative framework for the development of social skills. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(1):39-64. doi: 10.1037/a0017768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord C, Brugha TS, Charman T, et al. Autism spectrum disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):5. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0138-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ros R, Graziano PA. Social functioning in children with or at risk for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47(2):213-235. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1266644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spence SH, Donovan C, Brechman-Toussaint M. Social skills, social outcomes, and cognitive features of childhood social phobia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108(2):211-221. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.2.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurney JG, Krull KR, Kadan-Lottick N, et al. Social outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2390-2395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoza B, Gerdes AC, Mrug S, et al. Peer-assessed outcomes in the multimodal treatment study of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34(1):74-86. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asher SR. Recent advances in the study of peer rejection. In: Asher S, Coie J, eds. Peer Rejection in Childhood. Cambridge University Press; 1990:3-14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones DE, Greenberg M, Crowley M. Early social-emotional functioning and public health: the relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2283-2290. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn MM, Kavale KA, Mathur SR, Rutherford RB Jr, Forness SR. A meta-analysis of social skill interventions for students with emotional or behavioral disorders. J Emot Behav Disord. 1999;7(1):54-64. doi: 10.1177/106342669900700106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willis D, Siceloff ER, Morse M, Neger E, Flory K. Stand-alone social skills training for youth with ADHD: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2019;22(3):348-366. doi: 10.1007/s10567-019-00291-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrera M, Schulte F. A group social skills intervention program for survivors of childhood brain tumors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(10):1108-1118. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laugeson EA, Frankel F, Mogil C, Dillon AR. Parent-assisted social skills training to improve friendships in teens with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(4):596-606. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0664-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris S, Sheen J, Ling M, Foley D, Sciberras E. Interventions for adolescents with ADHD to improve peer social functioning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Atten Disord. 2021;25(10):1479-1496. doi: 10.1177/1087054720906514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storebø OJ, Elmose Andersen M, Skoog M, et al. Social skills training for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children aged 5 to 18 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6:CD008223. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008223.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans SW, Schultz BK, Demars CE, Davis H. Effectiveness of the Challenging Horizons After-School Program for young adolescents with ADHD. Behav Ther. 2011;42(3):462-474. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozonoff S, Miller JN. Teaching theory of mind: a new approach to social skills training for individuals with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1995;25(4):415-433. doi: 10.1007/BF02179376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolstencroft J, Robinson L, Srinivasan R, Kerry E, Mandy W, Skuse D. A systematic review of group social skills interventions, and meta-analysis of outcomes, for children with high functioning ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(7):2293-2307. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3485-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller A, Vernon T, Wu V, Russo K. Social skill group interventions for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;1:254-265. doi: 10.1007/s40489-014-0017-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karlsson P, Bergmark A. Compared with what? an analysis of control-group types in Cochrane and Campbell reviews of psychosocial treatment efficacy with substance use disorders. Addiction. 2015;110(3):420-428. doi: 10.1111/add.12799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gates JA, Kang E, Lerner MD. Efficacy of group social skills interventions for youth with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;52:164-181. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Constantino JN, Gruber CP. Social Responsiveness Scale. 2nd ed. Western Psychological Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Social Skills Improvement System Rating Scales. NCS Pearson; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lerner MD, White SW. Moderators and mediators of treatments for youth with autism spectrum disorders. In: Maric M, Prins P, Ollendick T, eds. Moderators and Mediators of Youth Treatment Outcomes. Oxford University Press; 2015:146-173. doi: 10.1093/med:psych/9780199360345.003.0007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. ; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group . The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343(7829):d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Comprehensive Meta-analysis. Version 3.0. Biostat; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT. Introduction to Meta-analysis. Vol 10. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. doi: 10.1002/9780470743386 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gleser LJ, Olkin I. Stochastically dependent effect sizes. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-analysis. 2nd ed. Russell Sage Foundation; 2009:357-376. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hedges LV, Pigott TD. The power of statistical tests for moderators in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 2004;9(4):426-445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11(2):193-206. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carlson KD, Schmidt FL. Impact of experimental design on effect size: findings from the research literature on training. J Appl Psychol. 1999;84(6):851-862. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.84.6.851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoyt WT, Del Re AC. Effect size calculation in meta-analyses of psychotherapy outcome research. Psychother Res. 2018;28(3):379-388. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2017.1405171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubio Aparicio M, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, López-López JA. Guidelines for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Ann Psychol. 2018;34(2):412-420. doi: 10.6018/analesps.34.2.320131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455-463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fraser MW, Day SH, Galinsky MJ, Hodges VG, Smokowski PR. Conduct problems and peer rejection in childhood: a randomized trial of the Making Choices and Strong Families programs. Res Soc Work Prac. 2004;14(5):313-324. doi: 10.1177/1049731503257884 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rice LM, Wall CA, Fogel A, Shic F. Computer-assisted face processing instruction improves emotion recognition, mentalizing, and social skills in students with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(7):2176-2186. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2380-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stichter JP, Herzog MJ, Kilgus SP, Schoemann AM. Exploring the moderating effects of cognitive abilities on social competence intervention outcomes. Behav Modif. 2018;42(1):84-107. doi: 10.1177/0145445517698654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Storebø OJ, Gluud C, Winkel P, Simonsen E. Social-skills and parental training plus standard treatment versus standard treatment for children with ADHD—the randomised SOSTRA trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e37280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E, Locke J, Gulsrud A. Making the connection: randomized controlled trial of social skills at school for children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53(4):431-439. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02493.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Antshel KM, Remer R. Social skills training in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32(1):153-165. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hannesdottir DK, Ingvarsdottir E, Bjornsson A. The OutSMARTers program for children with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2017;21(4):353-364. doi: 10.1177/1087054713520617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pfiffner LJ, McBurnett K. Social skills training with parent generalization: treatment effects for children with attention deficit disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(5):749-757. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.5.749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Michelson L, Mannarino AP, Marchione KE, Stern M, Figueroa J, Beck S. A comparative outcome study of behavioral social-skills training, interpersonal-problem-solving and non-directive control treatments with child psychiatric outpatients. Behav Res Ther. 1983;21(5):545-556. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(83)90046-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spence SH, Donovan C, Brechman-Toussaint M. The treatment of childhood social phobia: the effectiveness of a social skills training-based, cognitive-behavioural intervention, with and without parental involvement. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(6):713-726. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hopkins IM, Gower MW, Perez TA, et al. Avatar assistant: improving social skills in students with an ASD through a computer-based intervention. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(11):1543-1555. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1179-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soorya LV, Siper PM, Beck T, et al. Randomized comparative trial of a social cognitive skills group for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(3):208-216.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adams C, Lockton E, Gaile J, Earl G, Freed J. Implementation of a manualized communication intervention for school-aged children with pragmatic and social communication needs in a randomized controlled trial: the Social Communication Intervention Project. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2012;47(3):245-256. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00147.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dekker V, Nauta MH, Timmerman ME, et al. Social skills group training in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(3):415-424. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1205-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jonsson U, Olsson NC, Coco C, et al. Long-term social skills group training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(2):189-201. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1161-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koning C, Magill-Evans J, Volden J, Dick B. Efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy-based social skills intervention for school-aged boys with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2013;7(10):1282-1290. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.07.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choque Olsson N, Flygare O, Coco C, et al. Social skills training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(7):585-592. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beaumont R, Sofronoff K. A multi-component social skills intervention for children with Asperger syndrome: the Junior Detective Training Program. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(7):743-753. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01920.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matthews NL, Orr BC, Warriner K, et al. Exploring the effectiveness of a peer-mediated model of the PEERS curriculum: a pilot randomized control trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(7):2458-2475. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3504-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shum KK, Cho WK, Lam LMO, Laugeson EA, Wong WS, Law LSK. Learning how to make friends for Chinese adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial of the Hong Kong Chinese version of the PEERS® intervention. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(2):527-541. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3728-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomeer ML, Smith RA, Lopata C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mind reading and in vivo rehearsal for high-functioning children with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(7):2115-2127. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2374-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Begeer S, Gevers C, Clifford P, et al. Theory of mind training in children with autism: a randomized controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(8):997-1006. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1121-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Begeer S, Howlin P, Hoddenbach E, et al. Effects and moderators of a short theory of mind intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Autism Res. 2015;8(6):738-748. doi: 10.1002/aur.1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lopata C, Thomeer ML, Volker MA, et al. RCT of a manualized social treatment for high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(11):1297-1310. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0989-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Solomon M, Goodlin-Jones BL, Anders TF. A social adjustment enhancement intervention for high functioning autism, Asperger’s syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder NOS. J Autism Dev Disord. 2004;34(6):649-668. doi: 10.1007/s10803-004-5286-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thomeer ML, Lopata C, Donnelly JP, et al. Community effectiveness RCT of a comprehensive psychosocial treatment for high-functioning children with ASD. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019;48(suppl 1):S119-S130. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1247359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baghdadli A, Brisot J, Henry V, et al. Social skills improvement in children with high-functioning autism: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22(7):433-442. doi: 10.1007/s00787-013-0388-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andrews L, Attwood T, Sofronoff K. Increasing the appropriate demonstration of affectionate behavior, in children with Asperger syndrome, high functioning autism, and PDD-NOS: a randomized controlled trial. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2013;7(12):1568-1578. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.09.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frankel F, Myatt R, Sugar C, Whitham C, Gorospe CM, Laugeson E. A randomized controlled study of parent-assisted Children’s Friendship Training with children having autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(7):827-842. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0932-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koenig K, White SW, Pachler M, et al. Promoting social skill development in children with pervasive developmental disorders: a feasibility and efficacy study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(10):1209-1218. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0979-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rabin SJ, Israel-Yaacov S, Laugeson EA, Mor-Snir I, Golan O. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the Hebrew adaptation of the PEERS® intervention: behavioral and questionnaire-based outcomes. Autism Res. 2018;11(8):1187-1200. doi: 10.1002/aur.1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schohl KA, Van Hecke AV, Carson AM, Dolan B, Karst J, Stevens S. A replication and extension of the PEERS intervention: examining effects on social skills and social anxiety in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(3):532-545. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1900-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kavale KA, Mostert MP. Social skills interventions for individuals with learning disabilities. Learn Disabil Q. 2004;27(1):31-43. doi: 10.2307/1593630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang SY, Parrila R, Cui Y. Meta-analysis of social skills interventions of single-case research for individuals with autism spectrum disorders: results from three-level HLM. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(7):1701-1716. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1726-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McVey AJ, Dolan BK, Willar KS, et al. A replication and extension of the PEERS® for Young Adults Social Skills Intervention: examining effects on social skills and social anxiety in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(12):3739-3754. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2911-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Faltinsen E, Todorovac A, Hróbjartsson A, et al. Placebo, usual care and wait-list interventions for all mental health disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:MR000050. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Search Protocol

eTable 2. Intervention Characteristics of All Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis

eTable 3. Risk of Bias Summaries for eligible studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool

eTable 4. Moderators of Treatment Effect for Social Function Outcomes

eTable 5. Moderators of Treatment Effect for Social Cognition Outcome

eResults. Sensitivity Analyses

eReferences