Abstract

Background

In SELECT-PsA 1, a randomised double-blind phase 3 study, upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg were superior to placebo and non-inferior to adalimumab in ≥20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria at 12 weeks in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Here, we report 56-week efficacy and safety in patients from SELECT-PsA 1.

Methods

Patients received upadacitinib 15 mg or 30 mg once daily, adalimumab 40 mg every other week for 56 weeks or placebo through week 24 switched thereafter to upadacitinib 15 mg or 30 mg until week 56. Efficacy endpoints included the proportion of patients achieving ≥20%/50%/70% improvement in ACR criteria (ACR20/50/70), ≥75%/90%/100% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI75/90/100), minimal disease activity (MDA) and change from baseline in modified total Sharp/van der Heijde Score. Treatment-emergent adverse events per 100 patient years (PY) were summarised.

Results

Consistent with results through week 24, ACR20/50/70, PASI75/90/100 and MDA responses were maintained with upadacitinib through week 56 and were generally numerically higher than with adalimumab; inhibition of radiographic progression was also maintained. Patients who switched from placebo to upadacitinib exhibited comparable improvements at week 56 as patients originally randomised to upadacitinib. The rates of serious adverse events were 9.1 events/100 PY with upadacitinib 15 mg and 12.3 events/100 PY with upadacitinib 30 mg. Two deaths were reported in each of the upadacitinib groups.

Conclusion

Efficacy across various domains of PsA were maintained with upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg through week 56 with no new safety signals observed.

Keywords: adalimumab, arthritis, psoriatic, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Despite the availability of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in psoriatic arthritis (PsA), only a small percentage of patients achieve low disease activity; therefore, additional treatment options are needed.

In the SELECT-PsA 1 study, through 24 weeks, once daily upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg demonstrated improvements in clinical manifestations of PsA including musculoskeletal symptoms (peripheral arthritis, enthesitis and dactylitis), psoriasis, physical function, pain, fatigue and quality of life (QoL), as well as inhibition of radiographic progression in patients with PsA and inadequate response or intolerance to ≥1 non-biological DMARD. Additionally, the results demonstrated non-inferiority of both upadacitinib doses and superiority of upadacitinib 30 mg versus adalimumab in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20 response at week 12.

Key messages.

What does this study add?

Consistent with responses through week 24, between weeks 24 and 56 of the SELECT-PsA 1 study, responses for clinical manifestations of PsA including musculoskeletal symptoms (peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis and spondylitis), psoriasis, physical function, pain, fatigue and QoL, as well as inhibition of radiographic progression were increased or maintained with upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg. ACR20/50/70 and Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria responses were numerically greater with upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg versus adalimumab. Safety data through week 56 were also consistent with week 24 and the upadacitinib rheumatoid arthritis trials and did not show any new safety signal.

Efficacy results in patients who switched from placebo to upadacitinib were comparable to those observed in patients originally randomised to upadacitinib.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

56-week efficacy data across all domains of PsA support the benefits of continued upadacitinib therapy in patients with PsA. Safety at week 56 was comparable to findings through week 24.

Introduction

The treatment goal for psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is to maximise patient outcomes by controlling inflammation and preventing irreversible joint damage and disability.1 2 Treat-to-target strategies optimise treatment until the desired management goal, such as minimal disease activity (MDA), is achieved and maintained. Such an approach can improve long-term joint and skin outcomes and quality of life (QoL).3 4 Although multiple therapeutic choices are available, additional options are needed as under one third of patients achieve MDA in most placebo-controlled trials.5–10 Upadacitinib is an oral, reversible Janus kinase inhibitor approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), PsA and ankylosing spondylitis in the EU.11–15 The results of SELECT-PsA 1 through 24 weeks demonstrated that once daily (QD) upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg were more efficacious than placebo for clinical manifestations of PsA including musculoskeletal symptoms (peripheral arthritis, enthesitis and dactylitis), psoriasis, physical function, pain, fatigue and QoL, as well as inhibiting radiographic progression in patients with PsA and inadequate response (IR) or intolerance to ≥1 non-biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD).16 At week 24, greater improvements (nominal p≤0.05) were observed with upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg versus adalimumab in 20%/50%/70% improvement in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria (ACR20/50/70 responses). Here, we report safety and efficacy of upadacitinib versus adalimumab over 56 weeks from SELECT-PsA 1.

Patients and methods

Patients and study design

Inclusion criteria have been described previously.16 Briefly, patients in SELECT-PsA 1 (NCT03104400) were ≥18 years of age with active PsA and IR or intolerance to ≥1 non-biological DMARD. Patients were blindly randomised to upadacitinib 15 mg or 30 mg QD, placebo or adalimumab 40 mg every other week. At week 24, all placebo patients switched to upadacitinib 15 mg or 30 mg. Blinding was maintained to the sites until all patients reached the week 56 visit.

Stable treatment of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids and ≤2 non-biological DMARDs was permitted through week 36 but not required. However, after the week 16 visit had been completed, patients who qualified for rescue therapy were permitted to add or modify background therapy. After week 36, initiation or change in background PsA medication(s) was permitted for all patients. From week 36, all patients not achieving ≥20% improvement in tender joint count and swollen joint count (TJC/SJC) versus baseline at two consecutive visits were discontinued from study drug. Concomitant treatments specifically for psoriasis (eg, topicals, light therapy, retinoids) were not permitted until after week 16 psoriasis-related endpoints were evaluated. Also, from week 16, all patients who qualified for rescue therapy (ie, did not achieve ≥20% improvement in TJC and SJC at weeks 12 and 16 compared with baseline) were permitted to have background medication(s) initiated or changed.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Assessments

Efficacy endpoints were assessed through week 56. Online supplemental section S1 describes these assessments in detail. Importantly, changes from baseline in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) were assessed in patients with presumed psoriatic spondylitis at baseline. This determination of ‘psoriatic spondylitis’ was presumptively made by the treating physician based on their assessment of the totality of the information available to them, which could have included previous imaging, the duration and characteristics of back pain and/or the age of onset but was not confirmed by the recognised diagnostic tests required by the classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis. Safety reports are presented for all patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug. Adverse events (AEs) were coded per the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, V.22.0; AEs and laboratory changes were graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria AE V.5.0 and V.4.03, respectively. An independent, external Cardiovascular Adjudication Committee blindly adjudicated deaths and cardiovascular events per predefined event definitions. An internal Gastrointestinal (GI) Perforation Adjudication Committee blindly adjudicated reported GI perforation events as stated in the GI perforation charter.

rmdopen-2021-001838supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

Efficacy analyses were conducted in the full analysis set, including all randomised patients receiving ≥1 dose of study drug. For binary endpoints, treatments were compared using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, adjusting for current DMARD use (yes/no). Non-responder imputation (NRI) was used for missing data handling. As observed (AO) data excluding missing evaluations are also shown for binary endpoints at week 56. For non-radiographic continuous endpoints, analyses were conducted using a mixed-effects model repeated measures (MMRM) model based on AO data, with fixed effects of treatment, visit, treatment-by-visit interaction, current DMARD use and the corresponding baseline value as a covariate. Missing data were handled by MMRM assuming missing at random. Analyses for radiographic endpoints were based on an analysis of covariance model including treatment and current DMARD use as fixed factors and baseline value as a covariate, with linear extrapolation used as the primary approach for missing data handling. Patients originally randomised to placebo were switched to upadacitinib 15 mg or 30 mg at week 24 and summarised by ‘placebo to upadacitinib 15 mg or 30 mg’. Treatment comparisons between each upadacitinib dose versus adalimumab were conducted for the originally randomised upadacitinib groups and adalimumab for all non-radiographic endpoints; nominal p values are presented for weeks 12, 24 and 56.

For safety analyses, the upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg groups included patients who were originally randomised to placebo and switched to upadacitinib at week 24. Treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were summarised for events occurring while exposed to upadacitinib or adalimumab until the last subject reached week 56; exposure-adjusted event rates per 100 patient years (PY; E/100 PY) were summarised as events based on the treatment received at the time of each AE, during the time between the first and last dose of upadacitinib or adalimumab, and up to 30 or 70 days after, respectively, if the patient discontinued prematurely from the study; multiple events occurring in the same patient were included in the numerator and 95% CIs were calculated. Exposure-adjusted incidence rates per 100 PY were summarised as the number of patients with ≥1 event/100 PY (n/100 PY), with exposure calculated up to onset of the first event; multiple events occurring in the same patient were not included in the numerator and 95% CIs were calculated.

Results

Patients

Of 1705 patients randomised, 1419 (83.2%) completed 56 weeks of treatment (online supplemental figure S1). The most common reasons for study discontinuation across all treatment groups were withdrawal by patient and lack of efficacy. As reported previously, baseline characteristics were balanced across groups (online supplemental table S1).16

Efficacy

Consistent with previously reported week 24 results,16 upadacitinib continued to demonstrate efficacy at week 56 across key domains of PsA including musculoskeletal and skin outcomes and patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

Musculoskeletal outcomes

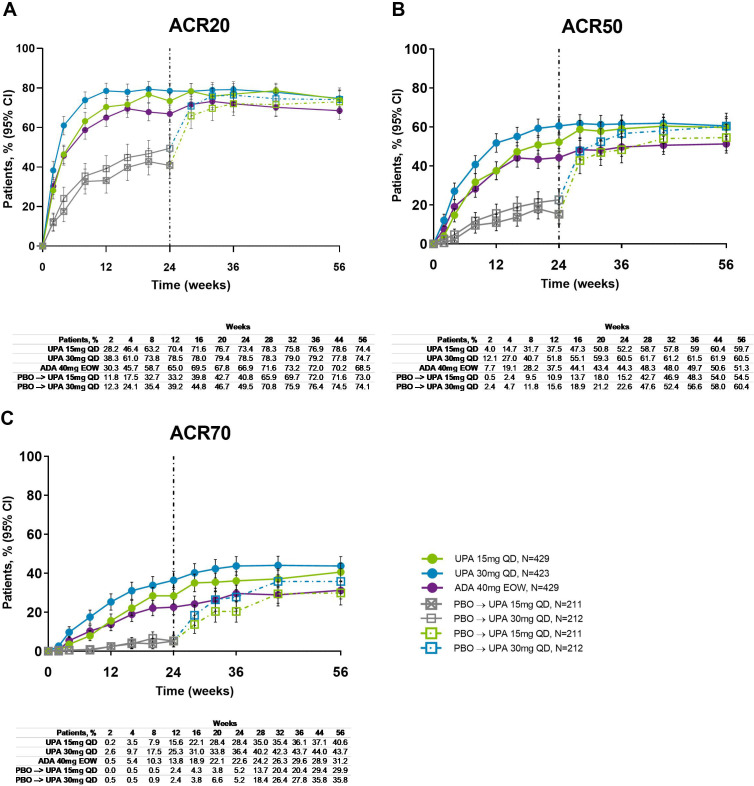

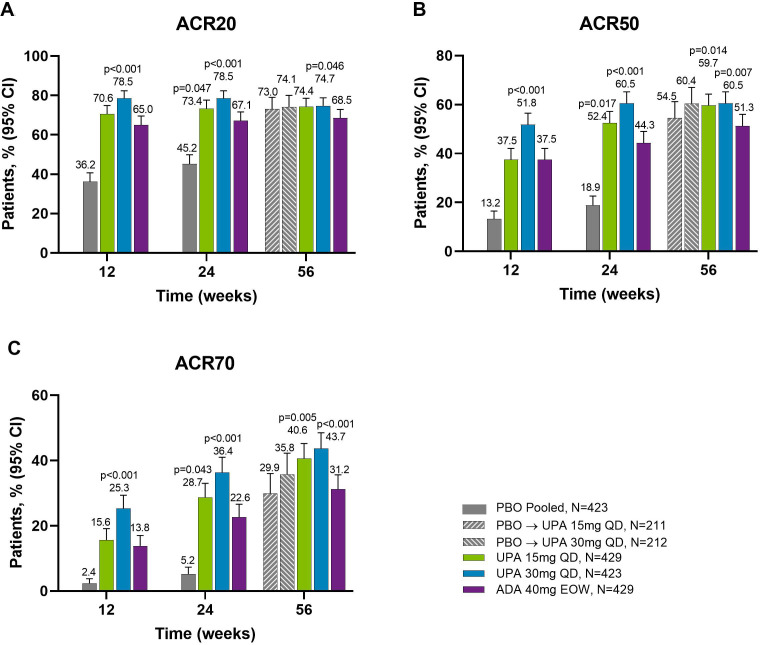

Across all treatment groups, the proportions of patients achieving ACR20/50/70 response were maintained from week 24 through week 56, with greater proportions of patients originally randomised to upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg achieving ACR20/50/70 compared with adalimumab at week 56 (NRI analysis; nominal p≤0.05 for upadacitinib 15 mg versus adalimumab for ACR50/70; nominal p≤0.05 for upadacitinib 30 mg versus adalimumab for ACR20/50/70) (figures 1 and 2). Improvements were observed for all ACR components (table 1). At week 56, patients originally randomised to placebo showed a similar ACR20/50/70 response following switch to upadacitinib at week 24. Individual patient responses for ACR20/50/70 over time, including the time course of achievement and sustainability of these responses are presented in online supplemental figure S1.

Figure 1.

Proportions of patients achieving (A) ACR20, (B) ACR50 and (C) ACR70 response over 56 weeks (NRI). ACR20/50/70, ≥20%/50%/70% improvement in American College of Rheumatology response criteria; ADA, adalimumab; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; EOW, every other week; NRI, non-responder imputation; PBO, placebo; QD, once daily; UPA, upadacitinib. Patients originally randomised to placebo switched to either upadacitinib 15 mg QD or upadacitinib 30 mg QD (1:1) at week 24 and their data up to week 24 are under placebo exposure. 95% CIs for response rate were calculated based on normal approximation to the binominal distribution. Nominal p value was constructed using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test adjusted for the main stratification factor of current DMARD use (yes/no).

Figure 2.

Proportions of patients achieving (A) ACR20, (B) ACR50 and (C) ACR70 response at weeks 12, 24 and 56 (NRI). Nominal p values are for upadacitinib versus adalimumab. ACR20/50/70, ≥20%/50%/70% improvement in American College of Rheumatology response criteria; ADA, adalimumab; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; EOW, every other week; NRI, non-responder imputation; PBO, placebo; QD, once daily; UPA, upadacitinib. For the week 56 data, patients originally randomised to placebo switched to either upadacitinib 15 mg QD or upadacitinib 30 mg QD (1:1) at week 24 and their data up to week 24 are under placebo exposure. 95% CIs for response rate were calculated based on normal approximation to the binominal distribution. Nominal p value was constructed using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test adjusted for the main stratification factor of current DMARD use (yes/no).

Table 1.

Continuous efficacy endpoints at week 56 (MMRM based on as observed data)

| Parameter | Placebo → UPA 15 mg QD (N=211) | Placebo → UPA 30 mg QD (N=212) | UPA 15 mg QD (N=429) | UPA 30 mg QD (N=423) | ADA 40 mg EOW (N=429) | |||||

| N | LSM change from BL (95% CI) | N | LSM change from BL (95% CI) | N | LSM change from BL (95% CI) | N | LSM change from BL (95% CI) | N | LSM change from BL (95% CI) | |

| PhGA | 177 | −4.7 (−4.9 to −4.5) | 177 | −4.8 (−5.1 to −4.6) | 378 | −4.9 (−5.0 to −4.7) | 360 | −4.9 (−5.0 to −4.7) | 360 | −4.7 (−4.8 to −4.5) |

| Swollen Joint Count (66 joints) | 178 | −9.2 (−9.7 to −8.7) | 178 | −9.6 (−10.1 to −9.2) | 375 | −9.7 (−10.1 to −9.4) | 360 | −9.8 (−10.1 to −9.4) | 358 | −9.6 (−9.9 to −9.3) |

| Tender Joint Count (68 joints) | 178 | −15.4 (−16.4 to −14.3) | 178 | −15.6 (−16.7 to −14.6) | 375 | −15.7 (−16.4 to −14.9) | 360 | −15.8 (−16.5 to −15.0) | 358 | −15.3 (−16.1 to −14.6) |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 173 | −7.5 (−8.6 to −6.5) | 169 | −8.7 (−9.8 to −7.7) | 356 | −7.8 (−8.6 to −7.1) | 351 | −8.6 (−9.3 to −7.9)† | 353 | −7.5 (−8.2 to −6.7) |

| HAQ-DI | 178 | −0.40 (−0.48 to −0.32) | 176 | −0.45 (−0.53 to −0.38) | 370 | −0.54 (−0.59 to −0.48)* | 361 | −0.56 (−0.61 to −0.50)† | 361 | −0.43 (−0.49 to −0.38) |

| FACIT-F | 178 | 7.2 (5.9 to 8.6) | 176 | 8.8 (7.4 to 10.1) | 370 | 8.9 (8.0 to 9.9) | 362 | 8.4 (7.4 to 9.4) | 364 | 7.6 (6.7 to 8.6) |

| SF-36 PCS | 178 | 9.3 (8.0 to 10.5) | 176 | 9.8 (8.6 to 11.1) | 371 | 10.8 (10.0 to 11.7)* | 362 | 10.5 (9.6 to 11.4)† | 364 | 8.9 (8.0 to 9.8) |

| SF-36 MCS | 178 | 3.6 (2.3 to 4.9) | 176 | 4.0 (2.7 to 5.3) | 371 | 5.2 (4.2 to 6.1) | 362 | 4.4 (3.4 to 5.3) | 364 | 4.3 (3.4 to 5.2) |

| Self-Assessment of Psoriasis Symptoms | 178 | −28.1 (−30.5 to −25.6) | 175 | −30.3 (−32.8 to −27.9) | 370 | −29.6 (−31.4 to −27.9)* | 362 | −30.4 (−32.2 to −28.7)† | 364 | −25.8 (−27.6 to −24.1) |

| WPAI overall work impairment‡ | 88 | −21.9 (−27.1 to −16.7) | 85 | −24.7 (−30.0 to −19.5) | 187 | −24.5 (−28.1 to −20.9) | 190 | −22.9 (−26.5 to −19.3) | 180 | −20.8 (−24.5 to −17.1) |

| PtGA (NRS) | 178 | −3.4 (−3.7 to −3.0) | 176 | −3.7 (−4.0 to −3.3) | 370 | −3.7 (−3.9 to −3.4)* | 361 | −3.6 (−3.9 to −3.4)† | 362 | −3.2 (−3.4 to −2.9) |

| Patients’ assessment of pain (NRS) | 178 | −3.1 (−3.5 to −2.8) | 176 | −3.3 (−3.7 to −3.0) | 370 | −3.3 (−3.6 to −3.1)* | 361 | −3.3 (−3.6 to −3.1)† | 362 | −2.9 (−3.1 to −2.7) |

| DAPSA | 173 | −38.9 (−41.1 to −36.7) | 166 | −41.6 (−43.8 to −39.3) | 355 | −40.0 (−41.5 to −38.4) | 348 | −41.0 (−42.6 to −39.4)† | 350 | −38.5 (−40.1 to −36.9) |

| ASDAS§ | 62 | −1.7 (−1.9 to −1.4) | 44 | −1.9 (−2.2 to −1.6) | 113 | −1.8 (−2.0 to −1.6) | 113 | −1.9 (−2.1 to −1.7)† | 102 | −1.6 (−1.8 to −1.4) |

| BASDAI§ | 63 | −3.1 (−3.6 to −2.6) | 46 | −3.1 (−3.7 to −2.5) | 116 | −3.3 (−3.7 to −2.9) | 119 | −3.2 (−3.6 to −2.8) | 107 | −2.8 (−3.2 to −2.4) |

All p values are nominal. Analyses were conducted using an MMRM model based on as observed data. Missing data were handled by MMRM assuming missing at random.

Per study design, all patients in the placebo group were switched to upadacitinib 15 mg one time a day or upadacitinib 30 mg one time a day at week 24.

*P≤0.05; for upadacitinib 15 mg QD versus adalimumab.

†P≤0.05; for upadacitinib 30 mg QD versus adalimumab.

‡Assessed in patients employed at baseline.

§Assessed in patients with psoriatic spondylitis at baseline as determined by the investigator based on available information, which could have included previous imaging, the duration and characteristics of the back pain and the age of onset.

ADA, adalimumab; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BL, baseline; DAPSA, Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; LSM, least squares mean; MCS, Mental Component Summary; MMRM, mixed-effects model repeated measures; NRS, numeric rating scale; PCS, Physical Component Summary; PhGA, Physicians’ Global Assessment of Disease Activity; PtGA, Patients' Global Assessment of Disease Activity; SF-36, Short Form Health Survey questionnaire; UPA, upadacitinib; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment.

The proportion of patients achieving Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria (PsARC) was also maintained from week 24 through week 56 in all treatment groups; more patients achieved PsARC response with upadacitinib 30 mg versus adalimumab at week 56 (nominal p≤0.05; online supplemental figure S3).

At week 56, similar proportions of patients originally randomised to upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg or adalimumab achieved resolution of enthesitis or dactylitis; these proportions were maintained or increased compared with week 24 (online supplemental figure S4).

At week 56, patients showed improvement in Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis (table 1), and patients with evidence of psoriatic spondylitis at baseline showed improvements in ASDAS and BASDAI. Comparable results at week 56 were observed in patients who switched from placebo to upadacitinib compared with patients originally randomised to upadacitinib (table 1).

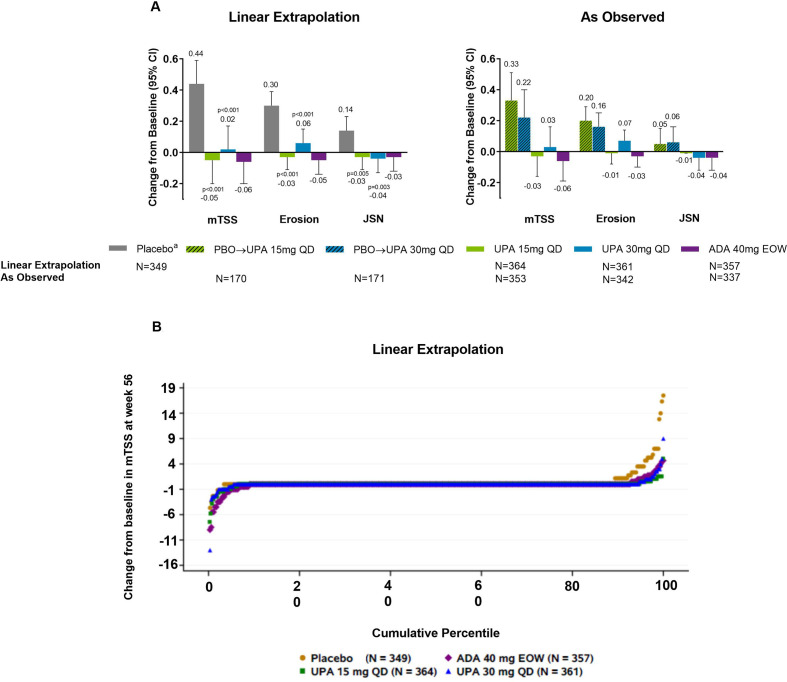

Mean changes from baseline in radiographic endpoints were comparable with upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg and adalimumab based on linear extrapolation at week 56 (figure 3). As linear extrapolation assumes results would follow the same trend regardless of switch or discontinuation, AO analyses were also conducted with similar results observed (figure 3). At week 56, the rates of non-progression were greater with upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg versus those initially randomised to placebo based on linear extrapolation analysis (nominal p≤0.05; online supplemental figure S5).

Figure 3.

(A) Change from baseline at week 56 in radiographic endpoints. (B) Probability plot of change from baseline in mTSS at week 56 (linear extrapolation). Nominal p values are for upadacitinib versus placebo. ADA, adalimumab; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; EOW, every other week; JSN, joint space narrowing score; mTSS, modified total Sharp/van der Heijde Score; PBO, placebo; QD, once daily; UPA, upadacitinib. Patients originally randomised to placebo switched to either upadacitinib 15 mg QD or upadacitinib 30 mg QD (1:1) at week 24 and their data up to week 24 are under placebo exposure. Least square mean and 95% CIs and nominal p values are based on an analysis of covariance model including treatment and the stratification factor current DMARD use (yes/no) as fixed factors and baseline value as covariate.

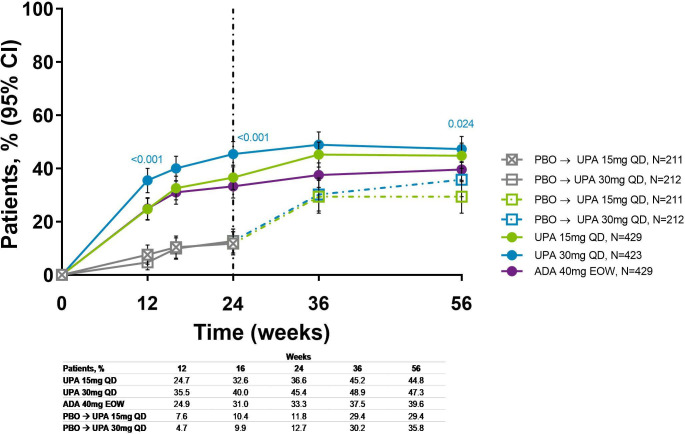

The proportions of overall patients achieving MDA were maintained from week 24 through week 56 in patients originally randomised to upadacitinib (36.6% and 45.4% for upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg, respectively, at week 24, and 44.8% and 47.3% at week 56) or adalimumab (33.3%–39.6%); more upadacitinib 30 mg-treated patients achieved MDA versus adalimumab at week 56 (nominal p≤0.05; figure 4). An increase in patients achieving MDA was observed for those originally randomised to placebo and switched to upadacitinib. Individual patient response for MDA over time showed that most patients who achieved MDA maintained the response through week 56 (online supplemental figure S6).

Figure 4.

Proportion of patients achieving MDA over 56 weeks (NRI). Nominal p values are for upadacitinib versus adalimumab. ADA, adalimumab; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; EOW, every other week; MDA, minimal disease activity; NRI, non-responder imputation; PBO, placebo; QD, once daily; UPA, upadacitinib. Patients originally randomised to placebo switched to either upadacitinib 15 mg QD or upadacitinib 30 mg QDy (1:1) at week 24 and their data up to week 24 are under placebo exposure. NRI with additional rescue handling was used, where patients rescued at week 16 are imputed as non-responders. 95% CIs for response rate were calculated based on normal approximation to the binominal distribution. Nominal p value was constructed using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test adjusted for the main stratification factor of current DMARD use (yes/no).

Skin outcomes

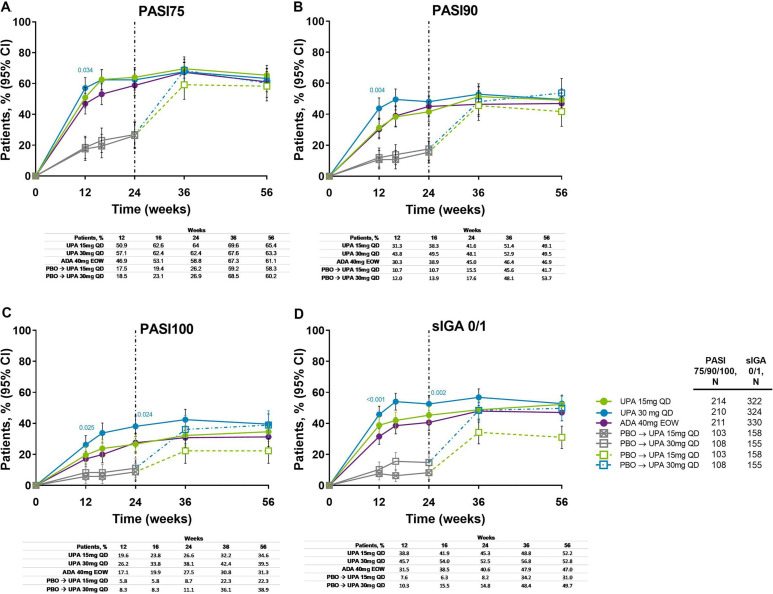

Improvements in skin outcomes were maintained over time in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI75/90/100) and Static Investigator Global Assessment of Psoriasis of 0 or 1 (sIGA 0/1) response rates (figure 5), and change from baseline in Self-Assessment of Psoriasis Symptoms (table 1). In patients randomised to placebo, the proportion of patients achieving PASI75/90/100 and sIGA 0/1 increased following switch to upadacitinib, and responses were similar to the upadacitinib groups at week 56. Individual patient PASI75/90 responses over time for all treatment groups, including the time course of achievement and sustainability of these responses, are presented in online supplemental figure S7.

Figure 5.

Proportion of patients achieving (A) PASI75, (B) PASI90, (C) PASI100 and (D) sIGA 0/1 response over 56 weeks (NRI). Nominal p values are for upadacitinib versus adalimumab. ADA, adalimumab; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; EOW, every other week; NRI, non-responder imputation; PASI75/90/100, ≥75%/90%/100% improvement in Psoriasis Area Severity Index; PBO, placebo; QD, once daily; sIGA, Static Investigator Global Assessment of Psoriasis; UPA, upadacitinib. After week 16 assessments have been performed, patients may use concomitant treatments specifically for psoriasis per investigator judgement. Patients originally randomised to placebo switched to either upadacitinib 15 mg QD or upadacitinib 30 mg QD (1:1) at week 24 and their data up to week 24 are under placebo exposure. 95% CIs for response rate were calculated based on normal approximation to the binominal distribution. Nominal p value was constructed using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test adjusted for the main stratification factor of current DMARD use (yes/no).

Patient-reported outcomes

Improvements were maintained from week 24 through week 56 in Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, Short Form Health Survey questionnaire (SF-36) Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary, patients’ assessment of pain, Patients’ Global Assessment of Disease Activity and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment. Similar proportions of patients across all treatment groups achieved ≥30% reduction in baseline pain and ≥50% reduction in baseline pain at week 56 (online supplemental figure S8). Furthermore, greater improvement was observed in the upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg groups compared with the adalimumab group for change from baseline in HAQ-DI and SF-36 PCS (nominal p≤0.05 for all comparisons; table 1). At week 56, improvements in PROs for patients randomised to placebo generally reached similar levels to those observed in patients randomised to upadacitinib.

The proportion of patients achieving HAQ-DI minimally clinically important difference (MCID) (improvement in HAQ-DI total score of ≥0.35 from baseline) or a normative HAQ-DI17 (HAQ-DI score ≤0.25) at week 24 continued to increase or was maintained through week 56. Compared with the adalimumab group, the proportion of patients who achieved an MCID in HAQ-DI was greater in the upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg groups at week 56 (nominal p<0.05) (online supplemental figures S9 and S10).

Numerically greater improvements in musculoskeletal, skin and PROs were generally observed at week 56 using AO analysis compared with NRI analysis (online supplemental table S2).

Safety

Through week 56, rates of TEAEs were higher with upadacitinib 30 mg versus upadacitinib 15 mg and adalimumab (333.9 vs 281.1 and 265.9 E/100 PY, respectively). Rates of serious AEs were also higher with upadacitinib 30 mg versus upadacitinib 15 mg and adalimumab (12.3 vs 9.1 and 9.3 E/100 PY, respectively). The most commonly reported AEs were upper respiratory tract infection and blood creatine phosphokinase (CPK) elevations (online supplemental table S3). Two deaths were reported with upadacitinib 15 mg (one from metastatic lung cancer and one from lower respiratory tract infection), two with upadacitinib 30 mg (one from coronavirus infection and one from interstitial lung disease) and one with adalimumab (due to a traffic accident). One death was reported in the placebo group during the 24-week placebo-controlled period in a patient who experienced an unspecified emergency while driving. These deaths are described in detail in online supplemental figure S2.

Up to week 56, the rate of serious infections was 2.9, 4.7 and 1.3 E/100 PY with upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg and adalimumab, respectively (figure 6). Treatment-emergent opportunistic infections included one event each of candida urethritis, bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and oral fungal infection with upadacitinib 15 mg; one event each of cytomegalovirus infection, oropharyngeal candidiasis and pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; and four events of oral fungal infection with upadacitinib 30 mg. No cases of active tuberculosis were reported. The rate of herpes zoster (HZ) was 3.9, 6.4 and 0.5 E/100 PY with upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg and adalimumab, respectively; most events were mild/moderate in severity, limited to one to two dermatomes, and did not lead to study drug discontinuation. Most patients experiencing an HZ event had not had a prior HZ vaccination.

Figure 6.

(A) Exposure-adjusted event and (B) incidence rates of treatment-emergent AEs through week 56. aExcluding tuberculosis and herpes zoster. ADA, adalimumab; AE, adverse event; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; EAER, exposure-adjusted event rate; EAIR, exposure-adjusted incidence rate; EOW, every other week; GI, gastrointestinal; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events (defined as non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke and cardiovascular death); NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; PY, patient years; QD, once daily; UPA, upadacitinib; VTE, venous thromboembolism (defined as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism). There were 11 malignancies reported in each of the upadacitinib 15 mg (4 basal cell carcinomas, 2 squamous cell carcinoma of skin and 1 event each of endometrial adenocarcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma, lung cancer metastatic, malignant melanoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma) and upadacitinib 30 mg groups (2 basal cell carcinomas, 2 squamous cell carcinoma of skin and 1 event each of adenocarcinoma of colon, Bowen’s disease, breast cancer, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, invasive breast carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma and plasma cell myeloma), and six malignancies reported with adalimumab (two basal cell carcinomas and one event each of colon cancer metastatic, ovarian cancer, pancreatic carcinoma metastatic and uterine cancer).

Malignancy event rates were similar with upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg and adalimumab, and no notable pattern or types of malignancies were observed. Most events of non-melanoma skin cancer were mild/moderate in severity, non-serious and did not lead to study drug discontinuation. Two basal cell carcinoma events led to study drug discontinuation (one in each of the upadacitinib groups). Two non-fatal strokes and one non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI) were reported in each of the upadacitinib 15 mg and adalimumab groups, and two non-fatal MIs were reported with upadacitinib 30 mg. These events are described in detail in online supplemental section S3. Ten venous thromboembolic events were reported in nine patients. One event of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) was reported in each of the upadacitinib groups and two with adalimumab; one event of pulmonary embolism (PE) was reported with upadacitinib 15 mg and three events with upadacitinib 30 mg. One patient in the upadacitinib 15 mg group had concurrent DVT and PE. These events are described in detail in online supplemental section S4.

Grade 3 decreases in haemoglobin, platelets, lymphocytes and neutrophils occurred in ≤4% of patients in each group; most events of lymphopenia were isolated, resolved without interruption in therapy and were not associated with bacterial, opportunistic, fungal or viral infections (online supplemental table S4). Grade 4 decreases in haemoglobin, platelets, lymphocytes and neutrophils were reported in ≤1% of patients in each group. However, post database lock, it was determined that all grade 4 decreases were captured due to data entry errors by the site and were not considered potentially clinically significant. AEs of anaemia and lymphopenia were more common with either dose of upadacitinib versus adalimumab and with upadacitinib 30 mg versus upadacitinib 15 mg. AEs of neutropenia were more common with upadacitinib 30 mg and adalimumab versus upadacitinib 15 mg.

The rate of hepatic disorder AEs was 19.1, 22.2 and 24.9 E/100 PY with upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg and adalimumab, respectively. Most alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) increases were mild/moderate (grade 2 or less) and transient. Grade 3 increases in ALT or AST were observed in <2.1% of patients across all groups. No Hy’s law cases were reported. Grade 3 or 4 CPK increases were more common with upadacitinib and were reported in <5.7% of patients; CPK increases were generally asymptomatic (one patient on upadacitinib 30 mg had CPK elevation >10 × upper limit of normal and experienced dermatomyositis approximately 34 days after discontinuing treatment due to a prior event of bronchitis), and no patients experienced rhabdomyolysis.

Discussion

SELECT-PsA 1 is a large study in patients with PsA who have had IR or intolerance to ≥1 non-biological DMARD and includes adalimumab as an active comparator; as such, this study offers the opportunity to understand the maintained efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in the context of current standard of care treatment for PsA. In this 56-week analysis, upadacitinib continued to demonstrate improvements in most clinically relevant manifestations of PsA including musculoskeletal and skin symptoms, physical function, QoL and other PROs, as well as inhibiting radiographic progression. In addition, the proportion of patients achieving MDA at week 24 continued to increase through week 56. Notably, upadacitinib continued to show results that were comparable with those of adalimumab at week 56, with results for some endpoints being significantly greater based on nominal p values. At week 56, improvements in patients who switched from placebo to upadacitinib were generally comparable, except for resolution of enthesitis and dactylitis, to those originally randomised to upadacitinib. Although not unexpected, it is encouraging to see that patients originally treated with placebo rapidly improved between weeks 24 and 56 after switching to upadacitinib, and reached similar levels of improvement as those originally randomised to upadacitinib.

Safety over 56 weeks remained consistent with observations through week 24 and the upadacitinib RA trials.11–16 18 Event rates of serious and opportunistic infections and HZ were greater with upadacitinib versus adalimumab. Treatment-emergent malignancies, major adverse cardiovascular events and venous thromboembolism appeared comparable across treatment groups.

A major limitation of the axial data presented from this trial includes the lack of axial imaging to assess for psoriatic spondylitis; the diagnosis was made on presumptive criteria that could have included patients without true spondylitis. As magnetic resonance images and radiographs of the sacroiliac joints and axial skeleton were not required to confirm evidence of inflammation in the spine nor radiographic changes in the spine or sacroiliac joints, the presence of ‘psoriatic spondylitis’ was based on the totality of the information available to the treating physician, which may have been subjective and may not have included imaging. This poses a potential major limitation to the interpretation of the results pertaining to axial symptoms. Another limitation was that this 56-week study was not powered or designed to include a prespecified statistical comparison for efficacy between the upadacitinib groups and adalimumab through week 56.

In summary, efficacy responses were maintained with upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg treatment over 56 weeks and were generally numerically higher than with adalimumab. The significant inhibition of radiographic progression at week 24 was maintained at week 56 and was similar in the upadacitinib and adalimumab groups. Additionally, at week 56, improvements in efficacy were observed in patients who switched from placebo to upadacitinib. No new safety findings were observed with longer term exposure to upadacitinib.

Acknowledgments

AbbVie and the authors thank the patients, trial sites and investigators who participated in this clinical trial. AbbVie was the trial sponsor, contributed to trial design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and to writing, review and approval of final version. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship. Medical writing support was provided by Ramona Vladea, PhD of AbbVie and Laura Chalmers, PhD of 2 the Nth (Cheshire, UK), and was funded by AbbVie.

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was first published. The author name 'Frank Behrens' was incorrectly spelt as 'Franck Behrens'.

Contributors: ALP, JL and KK participated in the design of the study. LC, YD, IBM, MM, JFM, MK, CP-T and DH participated in the acquisition of data. ALP, KK, LC, YD, PZ, JL, RL, IBM, MM, JFM, MK, CP-T and DH participated in the interpretation of data. LC and YD participated in the analysis of data. ALP, KK and IBM contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: AbbVie funded this study and participated in the study design, research, analysis, data collection, interpretation of data, review and approval of the publication. All authors had access to relevant data and participated in the drafting, review and approval of this publication. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship.

Competing interests: IBM: research grants and honoraria from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi Regeneron and UCB Pharma. MM: research grants from AbbVie, Amgen and UCB Pharma; consulting fees from Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma. JFM: consultant and/or investigator for AbbVie, Arena, Avotres, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, EMD Sorono, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma and UCB Pharma. MK: consulting fees and/or honoraria from AbbVie, AmgenAstellas BioPharma, Asahi-Kasei Pharma, Astellas, Ayumi Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai, DaiichiSankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Novartis, Ono Pharma, Pfizer, Tanabe-Mitsubishi, Teijin Pharma and UCB Pharma. CP-T: research grants and honoraria form AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche, R-Pharm, Sanofi Regeneron and UCB Pharma. DH: advisory board/speaker bureau or similar committee for AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme and Takeda; funded grant or clinical trials: AbbVie, Adiga Life-Sciences, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Can-Fite Biopharma, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme and UCB Pharma; honoraria or other fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Takeda and UCB Pharma; not a part of/has not received payment from a commercial organisation (gifts or ‘in kind’ compensation); does not hold a patent for a product referred to in the CME/CPD program, or marketed by a commercial organisation; does not hold investments in a pharmaceutical organisation, medical devices company or communications firm. FB: research grants from Celgene, Chugai, Janssen, Pfizer and Roche; consultancies/speaker fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer, Celgene, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Genzyme, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi and UCB Pharma. KK, ALP, YD, LC, PZ, RL, JL: AbbVie employees and may own AbbVie stock or options.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and statistical analysis plan and execution of a data-sharing agreement. Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process or to submit a request, visit the following website: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted according to the International Conference on Harmonization guidelines, applicable regulations and guidelines governing clinical trial conduct, and the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial protocol was approved by independent ethics committees and institutional review boards, and all patients provided written informed consent.

References

- 1.Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1060–71. 10.1002/art.39573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:700–12. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coates LC, Helliwell PS. Treat to target in psoriatic arthritis-evidence, target, research agenda. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2015;17:517. 10.1007/s11926-015-0517-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coates LC, Moverley AR, McParland L, et al. Effect of tight control of inflammation in early psoriatic arthritis (TICOPA): a UK multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:2489–98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00347-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deodhar A, Gottlieb AB, Boehncke W-H, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet 2018;391:2213–24. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30952-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. Lancet 2013;382:780–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60594-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mease P, Coates LC, Helliwell PS, et al. Efficacy and safety of filgotinib, a selective Janus kinase 1 inhibitor, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis (EQUATOR): results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2018;392:2367–77. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32483-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1537–50. 10.1056/NEJMoa1615975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mease P, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. Secukinumab improves active psoriatic arthritis symptoms and inhibits radiographic progression: primary results from the randomised, double-blind, phase III future 5 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:890–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:79–87. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burmester GR, Kremer JM, Van den Bosch F, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-NEXT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018;391:2503–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31115-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleischmann R, Pangan AL, Song I-H, et al. Upadacitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a phase III, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1788–800. 10.1002/art.41032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Combe B, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis refractory to biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (select-beyond): a double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018;391:2513–24. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31116-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smolen JS, Pangan AL, Emery P, et al. Upadacitinib as monotherapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate (select-monotherapy): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 3 study. Lancet 2019;393:2303–11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30419-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Vollenhoven R, Takeuchi T, Pangan AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib monotherapy in methotrexate-naive patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis (SELECT-EARLY): a randomized, double-blind, active-comparator, multi-center, multi-country trial. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:1607–20. 10.1002/art.41384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McInnes IB, Anderson JK, Magrey M, et al. Trial of upadacitinib and adalimumab for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1227–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa2022516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishnan E, Sokka T, Häkkinen A, et al. Normative values for the health assessment questionnaire disability index: benchmarking disability in the general population. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:953–60. 10.1002/art.20048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen SB, van Vollenhoven RF, Winthrop KL, et al. Safety profile of upadacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis: integrated analysis from the select phase III clinical programme. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;80:304–11. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2021-001838supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and statistical analysis plan and execution of a data-sharing agreement. Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process or to submit a request, visit the following website: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.