Abstract

Genetic relationships among 46 isolates of Mycobacterium avium recovered from 37 patients in a 2,500-bed hospital from 1993 to 1998 were assessed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and PCR amplification of genomic sequences located between the repetitive elements IS1245 and IS1311. Each technique enabled the identification of 27 to 32 different patterns among the 46 isolates, confirming that the genetic heterogeneity of M. avium strains is high in a given community. Furthermore, this retrospective analysis of sporadic isolates allowed us (i) to suggest the existence of two remanent strains in our region, (ii) to raise the question of the possibility of nosocomial acquisition of M. avium strains, and (iii) to document laboratory contamination. The methods applied in the present study were found to be useful for the typing of M. avium isolates. In general, both methods yielded similar results for both related and unrelated isolates. However, the isolates in five of the six PCR clusters were distributed among two to three PFGE patterns, suggesting that this PCR-based method may have limitations for the analysis of strains with low insertion sequence copy numbers or for resolution of extended epidemiologic relationships.

Despite the common occurrence of disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex disease in patients with AIDS, the epidemiology of this infection is incompletely understood. Notably, the predominant source of infection and whether disseminated M. avium complex infection results from reactivation or recent acquisition of infection in human AIDS patients remain unclear. It has recently been demonstrated that water distribution systems may be colonized with M. avium (18) and may subsequently serve as a potential source of infection for AIDS patients (43). However, in contrast to these findings, some epidemiologic and clinical studies have failed to find an association between specific environmental sources and human infection (16, 44). These conflicting results may, in particular, illustrate the need for suitable epidemiologic markers for investigation of the sources of M. avium infections as well as the routes of transmission, especially because of the large numbers of potential sources for human exposure.

Different laboratory methods, including serotyping (41), multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (45), restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis and hybridization to specific probes (4, 10, 11, 14, 15, 19, 29, 32, 33), and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (2, 4, 7, 23, 24, 36), have been applied for these purposes. The last two methods mentioned are DNA-based methods and typically use agarose gel electrophoresis of restriction enzyme-digested genomic DNA which is stained directly with ethidium bromide (PFGE) or which is transferred to membranes and probed with labeled DNA (RFLP analysis). Both techniques are relatively slow and labor-intensive (especially for M. avium, whose slow growth can delay the time to retrieval of results), requiring DNA of high integrity and at high concentrations. More recently, PCR-based typing methods have been described (22, 25, 31). The application of PCR to the molecular typing of bacterial species offers the potential for a relatively simple and inexpensive means of typing bacterial isolates for epidemiologic purposes. One of them, described by Picardeau and Vincent (31), used primers that bound to the ends of insertion elements specific for M. avium (IS1245 and IS1311), thus amplifying the DNA between closely spaced copies of these elements.

We investigated the genetic relationships of all M. avium isolates consecutively recovered from patients in the Rouen university hospital from 1993 to 1998 and a few isolates from patients in two smaller hospitals in the neighboring area by PFGE and PCR typing as described by Picardeau and Vincent (31). The aim of the study was (i) to characterize the genetic diversity of the M. avium strains from the Rouen hospital, (ii) to investigate whether nosocomial acquisition of M. avium infection either by cross-contamination or by exposure to a common source occurred in our large urban teaching hospital, and (iii) to evaluate whether this PCR-based method is reliable for typing and longitudinal analysis of large numbers of isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

M. avium isolates.

Forty-six isolates, including 35 isolates recovered from 26 patients with AIDS and 11 isolates from 11 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-uninfected patients, were studied. These isolates consisted of all M. avium isolates collected in the Rouen university hospital from March 1993 to March 1998 (40) and of other isolates initially cultured in two different hospitals in the area (a hospital in Dieppe, France, five isolates; a hospital in Evreux, France, one isolate). Among these 46 isolates were 13 sequential isolates cultured from identical or nonidentical sites from four patients (at intervals ranging from 8 to 670 days). The 46 M. avium isolates were cultured from sterile sites (blood [n = 25 isolates], bone marrow [n = 2], lymph node [n = 2], bladder [n = 1], and cutaneous biopsy specimen [n = 1]) and from nonsterile sites (gastric aspirates [n = 2], bronchopulmonary specimens [n = 11], and cutaneous specimens [n = 2]). In this study, isolates recovered from different patients were considered to be unrelated, and sequential isolates obtained from a single patient over weeks were considered to be related.

Isolates were identified as M. avium on the basis of conventional biochemical tests and by PCR-restriction enzyme pattern analysis of the hsp65 gene (37).

PFGE.

M. avium isolates were grown in 10 ml of Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with 0.5 M sucrose–0.05% Tween 80–10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose until they reached an optical density of 0.250 at 650 nm. Plugs were prepared and digested as described previously (21, 36) with 25 U of AseI (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.). Large restriction fragments were separated in a 1% agarose gel (SeaKem GTG; FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) at 14°C for 19.7 h by using the Gene Path system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Ivry/Seine, France). The patterns were visualized under UV light and were digitized with the Gel Doc 1000 documentation system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). PFGE fingerprints were analyzed by applying the Dice coefficient to peaks. For clustering, the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic means was used. A tolerance in the band positions of 1.2% was applied for comparison of the fingerprint patterns. Fingerprint analysis and the methods and algorithms used in this study were performed according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Bacteriophage lambda DNA concatemers (New England BioLabs) were included as molecular weight standards with each run.

PCR.

The PCR typing method used in the study was a variation of a previously reported procedure (31), with specific modifications made to simplify the extraction of DNA from mycobacteria. Briefly, one colony of M. avium was taken from Middlebrook 7H10 plates and was suspended in 20 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA [pH 7.6]) containing 1% Triton X-100. Five microliters of this suspension was submitted to a lytic cycle directly in the amplification tube of a GeneAmp PCR system 2400 (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) as described previously (3). Subsequently, 45 μl of the PCR reagent mixture was added to the PCR tube to initiate amplification. The PCR mixture and the amplification reactions were performed as described by Picardeau and Vincent (31). All experiments included negative controls which were processed with the samples. Amplification products were electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel (SeaKem LE; FMC BioProducts) and were detected by ethidium bromide staining. Gels were photographed with UV illumination, and band patterns were compared visually.

Reproducibility and discriminatory power of PFGE and PCR.

A total of 13 and 20 isolates were studied in duplicate by PFGE and PCR, respectively, to assess the reproducibilities of the PFGE and PCR patterns in our hands. Reproducibility was defined as the percentage of pairs with identical patterns. The discriminatory power was calculated as described by Hunter and Gaston (17) on the basis of the patterns obtained with the 37 unrelated isolates.

RESULTS

PFGE.

PFGE after AseI digestion of chromosomal DNA revealed 32 distinct banding patterns, according to the interpretive criteria of Tenover et al. (39), among the 46 isolates collected over 5 years from 37 patients. Of these 32 PFGE patterns, 25 were unique. The patterns observed were polymorphic and complex, including 10 to 18 fragments ranging from 35 to 900 kb (Fig. 1). The reproducibility rate of PFGE was 100%.

FIG. 1.

Restriction patterns from AseI digests of M. avium isolates resolved by PFGE. Lanes: 1 and 6, bacteriophage lambda DNA concatemers (sizes [in kilobases] are indicated on the left); 2, isolate 100A8; 3 and 4, pattern P7 (isolates 100A28 and 100A32, respectively); 5, isolate 100A25; 7 to 11, five sequential isolates from one patient, respectively (pattern P1); 12 to 15, four isolates from two patients, respectively (pattern P2).

Isolates obtained from different specimens collected from the same patient were compared. For two of the four HIV-infected patients studied, all sequential isolates had identical PFGE profile (patterns P1 and P3); for the third patient, one isolate differed from the two others by only a single band consistent with a single genetic event (Dice coefficient, 96%) (Fig. 2). Such minor variation was considered consistent with variation within a strain (pattern P2) (Fig. 2). For the fourth HIV-infected patient studied, the patterns of the two isolates cultured 668 and 670 days, respectively, after culture of the initial M. avium isolate presented up to six band differences compared with the original profile. Thus, they were considered possibly related to the first isolate and their profiles were designated subtypes of the initial profile (pattern P6) (39). Such variations have been reported among isolates collected over a long period of time (≥6 months) (39). Thus, for all four patients, we explicitly documented clonally disseminated M. avium infections, with three patients infected with a strain at multiple sites.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram of PFGE fingerprints of 46 M. avium isolates as determined by the Dice method. Brackets indicate identical or closely related patterns.

Among the patterns observed, one (pattern P4) was strictly identical for three isolates obtained from one urine and two bronchopulmonary samples from three HIV-negative patients monitored in three different units of the hospital in Dieppe. Their place of residence was not the same, but their clinical specimens were received in the laboratory on the same day, suggesting either laboratory contamination or nosocomial acquisition of the isolates. On the other hand, three particular clusters (patterns P2, P5, and P7) of two to four isolates each were defined according to the interpretive criteria of Tenover et al. (39). These clusters comprised isolates that were considered to be closely related because they exhibited very close PFGE patterns which differed by only one or two DNA fragments (Dice coefficients, 92 to 96%) (Fig. 2). Each of these clusters consisted of clinical isolates cultured from two patients who either attended the same hospital but at different times (from 3 to 21 months apart) or were monitored at different study sites (hospitals in Rouen and Dieppe) at different periods of time (18 months apart).

The patterns exhibited by the 11 isolates collected from HIV-negative patients were distributed throughout the dendrogram.

PCR.

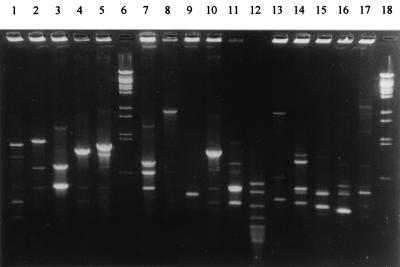

The same 46 isolates were also analyzed by a PCR-based typing technique with primers directed at the conserved inverted repeats of IS1245 and IS1311. This PCR was designed to amplify DNA segments between multiple copies of these elements, resulting in a mycobacterial strain-specific banding profile (31). These two primers generated PCR banding patterns with DNAs from all M. avium isolates included in the study. Twenty-seven profiles were observed among the 46 isolates. The PCR profiles were relatively diverse (Fig. 3). Banding patterns consisted of fewer than 10 bands ranging from 350 to 2,900 bp, with some corresponding to intense bands and others corresponding to weaker bands (Fig. 3). The PCR profiles were identical for strains isolated from the same patient (including isolates from different body sites) and were different for the majority of the strains from different patients. Twenty-one isolates had unique PCR patterns, and six profiles (labeled profiles A to F) with up to six bands were observed for two or more isolates. Most of the isolates included in the same PCR cluster had the same minor bands; the exception was for cluster D, the two isolates of which differed by one reproducible minor band, suggesting that these isolates were more likely closely related than identical (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

PCR typing of clinical M. avium isolates. Lanes: 1 to 5, 7 to 11, and 13 to 17, patterns of isolates obtained from 15 unrelated patients; lanes 6 and 18, bacteriophage lambda DNA-BstEII digest molecular weight marker; and lane 12, pBR322 DNA-MspI digest (New England Biolabs).

The reproducibility rate for this PCR based-typing method in our hands was 90% on the basis of different PCR tests with the same bacterial extracts of 20 isolates. Of note, for one isolate, an extra major band was apparent compared to the bands for other sequential isolates from the same patient (Fig. 4, lanes 7 and 9), but this band was no longer present when the PCR was repeated on two separate occasions (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Electrophoretic PCR patterns for M. avium isolates. Lanes 6 and 18, bacteriophage lambda DNA-BstEII digest; lane 12, pBR322 DNA-MspI digest (New England Biolabs); lanes 1 to 5, five sequential isolates from one patient, respectively (PCR profile A, PFGE pattern P1); lanes 7, 8, and 9, three sequential isolates from one patient, respectively (PCR profile A, PFGE pattern P2) (no amplification product was detected in lane 8 in that experiment); lane 10, isolate 100A31 from another patient (PCR profile A, PFGE pattern P2); lanes 11 and 13, two sequential isolates from one patient, respectively; lane 14, isolate 100A7 from a different patient (PCR profile E, PFGE pattern P6 or a unique pattern); lanes 15, 16, and 17, isolates 100A13, 100A26, and 100A30, respectively.

Comparison of typing methods.

To evaluate the epidemiologic value of PCR typing for isolates collected over a 5-year period, related and unrelated isolates were studied by both PFGE and PCR techniques. Analysis of the same 46 isolates by PCR yielded results similar to those of PFGE because of the similar banding patterns for isolates within most clusters detected by PFGE. One exception was for two isolates (isolates 100A13 and 100A26) that belonged to PFGE cluster P5 but that exhibited clearly different PCR profiles (Fig. 4, lanes 15 and 16). On the other hand, most of the unrelated isolates with distinct PFGE patterns had distinct PCR profiles. However, even if the numerical index of discriminatory power of both methods was 0.98, the isolates clustered in five of the six PCR profiles common to multiple isolates were distributed among two or three distinct PFGE patterns (Dice coefficients, 40 to 67%) (Fig. 2; Table 1). The DNAs of isolates with these five PCR profiles exhibited one to five bands (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

PFGE patterns of M. avium isolates clustered among the six PCR profiles shared by multiple isolates

| PCR

|

PFGE pattern(s) (no. of isolates) | Isolate nos.a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Profile (no. of bands) | No. of isolates (no. of patients) | ||

| A (1) | 9 (3) | P1 (5), P2 (4) | 31, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 56, 57, 58 |

| B (5) | 4 (3) | P3 (2), ub (2) | 27, 37, 45, 46 |

| C (1) | 3 (3) | P7 (2), u (1) | 8, 28, 32 |

| D (4) | 2 (2) | u (2) | 34, 38 |

| E (4) | 4 (2) | P6 (3), u (1) | 7, 17, 18, 19 |

| F (6) | 3 (3) | P4 (3) | 41, 42, 43 |

The prefix for all isolate designations is 100A.

u, unique PFGE pattern.

DISCUSSION

Precise definition of the epidemiology and mode of transmission of infectious bacterial diseases requires both detailed clinical and epidemiologic data and an effective method (which meets the criteria of typeability, reproducibility, and discriminatory power [1, 20]) for the differentiation of different strains of the organism concerned. The analysis of multiple isolates from each infected patient can also provide insights into the pathogenesis of infection (2, 36).

The aim of the present study was to analyze retrospectively related and unrelated M. avium isolates collected over a 5-year period from patients in the same hospital, to define the local epidemiology of M. avium infections, and to expand our understanding of the local chain of transmission of M. avium.

Among all the various approaches previously attempted for the typing of M. avium isolates, PFGE has been proposed as the “gold standard” (1, 2, 20, 24, 38) because of its highly discriminatory and reproducible results. However, because this method remains laborious and time-consuming, especially when it is applied to mycobacteria, the evaluation of other techniques is appreciated. For this reason, we analyzed our collection of 46 isolates of M. avium recovered from 1993 through 1998 by two techniques that rely on independent molecular markers: PFGE after AseI digestion of the chromosomal DNA and a PCR-based technique with oligonucleotide primers against the inverted repeats of IS1245 and IS1311 (31).

Picardeau and colleagues (30, 31) have previously shown that this PCR typing technique is rapid and simple and is as discriminatory as RFLP analysis. In agreement with their findings, in our hands, this typing system provided reproducible and easy-to-analyze patterns comprising fewer than 10 bands. Faint bands were taken into account only when they were reproducible in different PCR tests. Indeed, there were variations in some of the minor and/or major PCR products, which may make the comparison of large number of strains difficult. One of the most critical limitations, which was associated with a low insertion sequence copy number, is that the corresponding patterns, which consisted of only one band, are poorly discriminatory for epidemiologically unrelated isolates that represent distinct strains as resolved by PFGE (Dice coefficients, 40 to 62%). These observations are analogous to those obtained by IS1245 Southern blot analysis (8, 10, 11, 29, 32) and to those reported by Ross and Dwyer (34) from their analysis of two strains with one IS6110 copy by a similar PCR-based method that relied on the amplification of DNA fragments between IS6110 copies. On the other hand, this PCR typing method seems to have a lower discriminatory power than PFGE (despite a good numerical index that was calculated according to the recommendations of Hunter and Gaston [17]) because five sets of isolates clustered in one PCR pattern were distributed among two or three PFGE patterns, and the two isolates in one PFGE cluster pattern (pattern P5) had two distinct PCR patterns.

Except for these limitations, the comparison of the two fingerprinting methods revealed that the banding patterns were similar within each cluster and were distinct from those for strains from different clusters.

Both typing techniques performed in the present study demonstrated the heterogeneity of the M. avium species by the high number (32 PFGE patterns and 27 PCR profiles) and high degree of diversity of the patterns observed for the 37 unrelated isolates. This is consistent with the results of previous studies based on PFGE, RFLP analysis with repetitive insertion sequences as DNA probes, or PCR (2, 6, 14, 24, 30, 31, 33, 36). No prevalent strain was identified among HIV-infected patients, and the patterns of the isolates from HIV-negative patients were diverse, too. This marked polymorphism contrasts with the similarity between isolates obtained from the same patient over time, which indicates monoclonal infections.

Among the 37 unrelated M. avium isolates included in our study, PFGE and/or PCR analyses defined four clusters (clusters P2, P4, P5, and P7) of identical or closely genetically related isolates recovered from two patients. The information collected for patients infected with isolates in clusters P2 and P5 indicated that there was no epidemiologic link between the two patients. Under these conditions, the identification of two strains collected a few years apart and/or in different cities could suggest that some M. avium strains could be maintained in a population and/or in the same geographic area for several years, as reported previously for two M. avium strains collected for up to almost 4 years in the recirculating hot water systems of two hospitals (43). This has also been described for other bacteria such as isolates of Staphylococcus aureus that were genotypically identical and that were recovered over a long period of time from unrelated patients (28, 35). With respect to cluster P7, because the two patients concerned attended the same facility at the same hospital over a 3-month period but also lived in cities that were close to each other, many hypotheses can be evoked, including exposure to an unidentified common (nosocomial [43] or not nosocomial) environmental source or direct transmission from patient to patient, even if the latter has never been reported (6, 18, 26). Cluster P4 included clinical isolates collected on the same day from three HIV-negative patients (patients 1, 2, and 3) attending three different medical units of the same hospital during the same period. A nosocomial outbreak or laboratory contamination, as reported previously (5), could therefore be suspected. The retrospective review of the bacteriological data for the three patients revealed that three urine samples collected 1 day apart from patient 1 yielded multiple M. avium colonies 21 to 32 days after the inoculation of the solid media, consistent with a high likelihood of true M. avium infection. In contrast, retrospective assessment of the bacteriological and clinical significance of the isolation of M. avium from patients 2 and 3 failed to suggest a role for these isolates as pathogens. No contamination at the time of sample collection can be suspected because this step was performed by different persons in each unit. In contrast, a laboratory contamination event remains a likely explanation for cluster P4. Indeed, the two identical M. avium isolates from patients 2 and 3 cultured over a long time (51 to 75 days) may be the result of cross-contamination from the positive urine sample from patient 1 since the samples from patients 2 and 3 were received and sequentially processed at the laboratory on the same day as the sample from patient 1. The two other M. avium strains (strains 100A26 and 100A39) isolated in this laboratory from 1993 to 1998 had clearly distinct PCR and PFGE profiles (Dice coefficient, 43%), suggesting that this contamination was self-limited. The impact of this contamination was much lower than that reported previously (5, 9, 12, 13, 27, 40, 42) as the result of a dysfunction of the BACTEC system or a low inoculum of M. avium in medium additives from an exogenous source or other hospital or laboratory sources, which generated large pseudo-outbreaks.

In summary, the one-band patterns and the variations observed in some of the minor and/or major bands could make the comparison of large numbers of isolates by the PCR-based technique used in this study difficult. We therefore recommend that this rapid technique, which does not need a tedious DNA preparation step in particular, could be used to investigate small numbers of isolates collected over a short period of time or for preliminary screening (especially for investigation of several colonies from a single strain), whereas PFGE remains the reference technique for strain characterization and seems more suitable for large-scale studies.

The application of molecular techniques such as PFGE and PCR enabled us (i) to investigate the genetic diversity of the M. avium strains present in a given community, (ii) to identify the existence of possible remanent strains in our particular given region, (iii) to raise the question of the nosocomial acquisition of an M. avium strain, and (iv) to document laboratory contamination. Thereby, this study confirms how useful molecular strain typing can be in investigations of the genetic relationships of M. avium isolates collected in a given community.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully thank R. D. Arbeit for interest and helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arbeit R D. Laboratory procedures for the epidemiologic analysis of microorganisms. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 116–137. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbeit R D, Slutsky A, Barber T W, Maslow J N, Niemczyk S, Falkinham III J O, O’Connor G T, Von Reyn C F. Genetic diversity among strains of Mycobacterium avium causing monoclonal and polyclonal bacteremia in patients with AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1384–1390. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.6.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbier-Frebourg N, Nouet D, Lemee L, Martin E, Lemeland J-F. Comparison of ATB Staph, Rapid ATB Staph, Vitek, and E-test methods for detection of oxacillin heteroresistance in staphylococci possessing mecA. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:52–57. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.52-57.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bono M, Jemmi T, Bernasconi C, Burki D, Telenti A, Bodmer T. Genotypic characterization of Mycobacterium avium strains recovered from animals and their comparison to human strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:371–373. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.371-373.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burki D R, Bernasconi C, Bodmer T, Telenti A. Evaluation of the relatedness of strains of Mycobacterium avium using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:212–217. doi: 10.1007/BF02310358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbonne A, Lemaitre N, Bochet M, Truffot-Pernot C, Katlama C, Grosset J, Bricaire F, Jarlier V. Mycobacterium avium complex common-source or cross-infection in AIDS patients attending the same day-care facility. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1998;19:784–786. doi: 10.1086/647725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffin J W, Condon C, Compston C A, Potter K N, Lamontagne L R, Shafiq J, Kunimoto D Y. Use of restriction fragment length polymorphisms resolved by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for subspecies identification of mycobacteria in the Mycobacterium avium complex and for isolation of DNA probes. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1829–1836. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1829-1836.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins D M, Cavaignac S, de Lisle G W. Use of four DNA insertion sequences to characterize strains of the Mycobacterium avium complex isolated from animals. Mol Cell Probes. 1997;11:373–380. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1997.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conville P S, Keiser J F, Witebsky F G. Mycobacteremia caused by simultaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare detected by analysis of a BACTEC 13A bottle with the Gen-Probe kit. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;12:217–219. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(89)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devallois A, Rastogi N. Computer-assisted analysis of Mycobacterium avium fingerprints using insertion elements IS1245 and IS1311 in a Caribbean setting. Res Microbiol. 1997;148:703–713. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(99)80069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garzelli C, Lari N, Nguon B, Cavallini M, Pistello M, Falcone G. Comparison of three restriction endonucleases in IS1245-based RFLP typing of Mycobacterium avium. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:933–939. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-11-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham L, Jr, Warren N G, Tsang A Y, Dalton H P. Mycobacterium avium complex pseudobacteriuria from a hospital water supply. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1034–1036. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.5.1034-1036.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gubler J G H, Salfinger M, Von Graevenitz A. Pseudoepidemic of nontuberculous mycobacteria due to a contaminated bronchoscope cleaning machine. Chest. 1992;101:1245–1249. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.5.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerrero C, Bernasconi C, Burki D, Bodmer T, Telenti A. A novel insertion element from Mycobacterium avium, IS1245, is a specific target for analysis of strain relatedness. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:304–307. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.304-307.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hampson S J, Thompson J, Moss M T, Portaels F, Green E P, Hermon-Taylor J, McFadden J J. DNA probes demonstrate a single highly conserved strain of Mycobacterium avium infecting AIDS patients. Lancet. 1989;i:65–69. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91427-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horsburgh C R, Jr, Chin D P, Yajko D M, Hopewell P C, Nassos P S, Elkin E P, Hadley W K, Stone E N, Simon E M, Gonzalez P, Ostroff S, Reingold A L. Environmental risk factors for acquisition of Mycobacterium avium complex in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:362–367. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunter P R, Gaston M A. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson’s index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2465–2466. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.11.2465-2466.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inderlied C B, Kemper C A, Bermudez L E M. The Mycobacterium avium complex. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:266–310. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lari N, Cavallini M, Rindi L, Iona E, Fattorini L, Garzelli C. Typing of human Mycobacterium avium isolates in Italy by IS1245-based restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3694–3697. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3694-3697.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maslow J N, Mulligan M E, Arbeit R D. Molecular epidemiology: application of contemporary techniques to the typing for microorganisms. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:153–164. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maslow J N, Slutsky A M, Arbeit R D. Application of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to molecular epidemiology. In: Persing D H, Smith T F, Tenover F C, White T J, editors. Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 563–572. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsiota-Bernard P, Waser S, Tassios P T, Kyriakopoulos A, Legakis N J. Rapid discrimination of Mycobacterium avium strains from AIDS patients by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1585–1588. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1585-1588.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazurek G H, Chin D P, Hartman S, Reddy V, Horsburgh C R, Jr, Green T A, Yajko D M, Hopewell P C, Reingold A L, Crawford J T. Genetic similarity among Mycobacterium avium isolates from blood, stool, and sputum of persons with AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:976–983. doi: 10.1086/516509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazurek G H, Hartman S, Zhang Y, Brown B A, Hector J S R, Murphy D, Wallace R J., Jr Large DNA restriction fragment polymorphism in the Mycobacterium avium-M. intracellulare complex: a potential epidemiologic tool. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:390–394. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.390-394.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazurek G H, Reddy V, Marston B J, Haas W H, Crawford J T. DNA fingerprinting by infrequent-restriction-site amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2386–2390. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2386-2390.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McFadden J J, Kunze Z M, Portaels F, Labrousse V, Rastogi N. Epidemiological and genetic markers, virulence factors and intracellular growth of Mycobacterium avium in AIDS. Res Microbiol. 1992;143:423–430. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90057-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray P R. Mycobacterial cross-contamination with the modified Bactec 460 TB system. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;14:33–35. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(91)90085-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pestel M, Pons J-L, Goodman R, Aronson E, Maslow J, Arbeit R D. Program and abstracts of the 8th International Symposium on Staphylococci and Staphylococcal Infections. 1996. Fifteen year review of the genetic diversity of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream isolates at a VA Medical Center, abstr. P297. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pestel-Caron M, Arbeit R D. Characterization of IS1245 for strain typing of Mycobacterium avium. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1859–1863. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.1859-1863.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Picardeau M, Varnerot A, Lecompte T, Brel F, May T, Vincent V. Use of different molecular typing techniques for bacteriological follow-up in a clinical trial with AIDS patients with Mycobacterium avium bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2503–2510. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2503-2510.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Picardeau M, Vincent V. Typing of Mycobacterium avium isolates by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:389–392. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.389-392.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritacco V, Kremer K, Van Der Laan T, Pijnenburg J E M, de Hass P E W, Van Soolingen D. Use of IS901 and IS1245 in RFLP typing of Mycobacterium avium complex: relatedness among serovar reference strains, human and animal isolates. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:242–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roiz M P, Palenque E, Guerrero C, Garcia M J. Use of restriction fragment length polymorphism as a genetic marker for typing Mycobacterium avium strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1389–1391. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1389-1391.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross B C, Dwyer B. Rapid, simple method for typing isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by using the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:329–334. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.329-334.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlichting C, Branger C, Fournier J-M, Witte W, Boutonnier A, Wolz C, Goullet P, Doring G. Typing of Staphylococcus aureus by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, zymotyping, capsular typing, and phage typing: resolution of clonal relationships. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:277–232. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.227-232.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slutsky A M, Arbeit R D, Barber T W, Rich J, Von Reyn C F, Pieciak W, Barlow M A, Maslow J N. Polyclonal infections due to Mycobacterium avium complex in patients with AIDS detected by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of sequential clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1773–1778. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1773-1778.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Telenti A, Marchesi F, Balz M, Bally F, Bottger E C, Bodmer T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:175–178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.175-178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V. How to select and interpret molecular strain typing methods for epidemiological studies of bacterial infections: a review for healthcare epidemiologists. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997;18:426–439. doi: 10.1086/647644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tokars J I, McNeil M M, Tablan O C, Chapin-Robertson K, Patterson J E, Edberg S C, Jarvis W R. Mycobacterium gordonae pseudoinfection associated with a contaminated antimicrobial solution. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2765–2769. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2765-2769.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsang A Y, Denner J C, Brennan P J, McClatchy J K. Clinical and epidemiological importance of typing of Mycobacterium avium complex isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:479–484. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.479-484.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vannier A M, Tarrand J J, Murray P R. Mycobacterial cross contamination during radiometric culturing. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1867–1868. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.9.1867-1868.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Von Reyn C F, Maslow J N, Barber T W, Falkinham III J O, Arbeit R D. Persistent colonisation of potable water as a source of Mycobacterium avium infection in AIDS. Lancet. 1994;343:1137–1141. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yajko D M, Chin D P, Gonzalez P C, Nassos P S, Hopewell P C, Reingold A L, Horsburgh C R, Jr, Yakrus M A, Ostroff S M, Hadley W K. Mycobacterium avium complex in water, food, and soil samples collected from the environment of HIV-infected individuals. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;9:176–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yakrus M A, Reeves M W, Hunter S B. Characterization of isolates of Mycobacterium avium serotypes 4 and 8 from patients with AIDS by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1474–1478. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1474-1478.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]