Abstract

The development of gene-editing technology holds tremendous potential for accelerating crop trait improvement to help us address the need to feed a growing global population. However, the delivery and access of gene-editing tools to the host genome and subsequent recovery of successfully edited plants form significant bottlenecks in the application of new plant breeding technologies. Moreover, the methods most suited to achieve a desired outcome vary substantially, depending on species' genotype and the targeted genetic changes. Hence, it is of importance to develop and improve multiple strategies for delivery and regeneration in order to be able to approach each application from various angles. The use of transient transformation and regeneration of plant protoplasts is one such strategy that carries unique advantages and challenges. Here, we will discuss the use of protoplast regeneration in the application of new plant breeding technologies and review pertinent literature on successful protoplast regeneration.

Keywords: protoplast, regeneration, gene editing, crop improvement, tissue culture

Introduction

Since the advent of CRISPR/Cas9 and related gene-editing technology, direct modification of crop genomes has become the way of the future for advanced breeding techniques in agriculture (Zhang et al., 2019). These new plant breeding technologies (NPBT) have opened avenues of fundamental and translational research that were previously inaccessible. In contrast to transgenic approaches, NPBT can avoid costly and time-consuming regulatory hurdles and accelerate the introduction of new crop lines to the ag market (Lassoued et al., 2021).

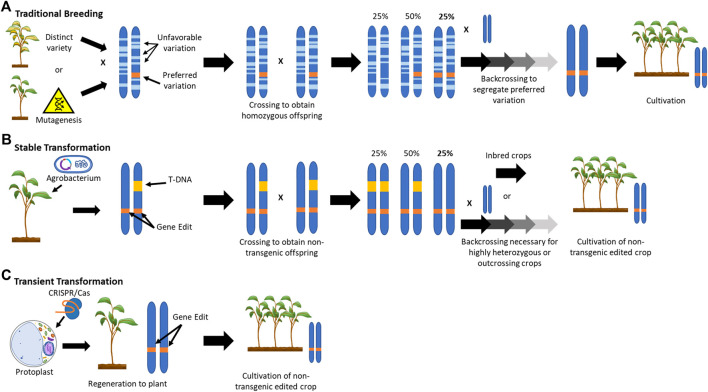

Breeding for the introgression of new traits from a wild relative or mutagenized population into an elite crop cultivar is a lengthy procedure, requiring numerous rounds of selection to regain the characteristics of the parental strain (Figure 1A). The ability to efficiently modify crop genes can save several years over conventional breeding approaches and phenotypic recurrent selection (Bull et al., 2017). However, the current most commonly used NPBT method of inserting a transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 construct into the host genome and then crossing it out again to obtain transgene-free progeny still requires multiple rounds of selection (Figure 1B). This is especially true for highly heterozygous and/or outcrossing crops.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic Representation of the Application of New Plant Breeding Technologies.

In contrast to conventional breeding or transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 approaches, gene editing through transient transformation and regeneration of protoplasts can achieve the desired genetic outcome within a single clonal generation by avoiding the integration of foreign DNA into the host genome (Figure 1C). Aside from the potential to speed up the application of NPBT, the use of protoplasts may have numerous other advantages.

Advantages of Using Protoplasts in NPBT

As stated above, the use of transient transformation of protoplasts can circumvent transgenesis (the integration of genetic material from one organism into the genome of another organism). The enzymatic removal of the plant cell wall allows for the introduction of foreign DNA, RNA, or protein into protoplasts through either polyethylene glycol (PEG) treatment or electroporation. Although relatively infrequent, the use of DNA (often in the form of plasmids) does not fully preclude the random integration of transgenes (Lin et al., 2018). However, CRISPR/Cas9 can also be expressed through transformation with mRNA encoding the Cas9 enzyme along with the desired guide RNA (gRNA) (Zhang et al., 2016). Alternatively, protoplasts can be transformed with ribonucleoprotein complexes, consisting of Cas9 associated with the gRNA (Svitashev et al., 2016). The latter two approaches more effectively preclude the integration of foreign DNA, although there have been cases where DNA-template contamination in the in vitro transcribed mRNA or gRNA has led to insertions, e.g. (Andersson et al., 2018). Particle bombardment is a potential alternative for transient delivery method for DNA-free gene-editing tools, e.g. (Liang et al., 2018). However, it may suffer from limitations in transformation efficiency and the regeneration of chimeric plants (as discussed below).

If the goal of the gene-editing approach goes beyond site-specific insertions and/or deletions for the knock-out of gene function but instead aims for specific nucleotide substitutions or insertion of a specific sequence through homologous recombination, there is a need for the co-introduction of a DNA-repair template (as in oligo directed mutagenesis) or a donor sequence, respectively. Prime editing and viral replicons are potential methods to deliver such templates and donors transgenically (Čermák et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2020). However, in addition to the potential for a non-transgenic outcome, the use of protoplasts allows for more control over the amount of template or donor delivered and effect higher precision and efficiency, e.g. (Sauer et al., 2016).

In many plant species, the lack of host susceptibility to Agrobacterium transformation limits the use of transgenic NPBT approaches. This is seen in particular in monocots (Hwang et al., 2017). Host-pathogen incompatibility is also expected to be a limiting factor in the applicability of viruses for the delivery of gene-editing tools (Ma et al., 2020). In such cases, the use of protoplasts (or particle bombardment) may be a feasible alternative delivery method.

Chimerism (where only parts of the regenerated plant are descended from an edited cell) can be an issue when using conventional, tissue-culture based approaches where a callus intermediate is used, e.g. (Charrier et al., 2019). This phenomenon occurs because de novo shoots or embryos can be formed from a group of cells rather than a single antecedent. In the case of protoplasts, regenerated plants are (in most cases) derived from a single cell, thereby avoiding this potential problem. Chimerism can be a concern especially when non-selectable, non-transgenic approaches are used together with conventional tissue culture, e.g. transient transformation with Agrobacterium or particle bombardment. Additionally, such non-selectable strategies can suffer from low editing efficiency in the regenerated plants because only the cells on the surface of the tissue are potentially edited whereas regeneration can also occur from the numerous non-transformed cells. In comparison, protoplast transformation efficiencies are much higher and plants regenerated from protoplasts transiently transformed with editing tools will therefore have better chance of being successfully edited.

However, a glaring limitation in the use of protoplasts for NPBT is the challenges faced in the regeneration of plants from single cells and there appears to be no universal strategy that applies to diverse (sub)species. Plant tissue culture in general, and protoplast regeneration in particular, is often lightheartedly considered more of an artform than a science, requiring an experienced eye and instinctual decision making, as comprehensive systematic approaches are too vast in scope to be feasible. In this review, we will discuss a compilation of literature on plant regeneration from protoplasts. We will deliberate protoplast isolation, protoplast culture, and plant regeneration from protoplast culture, specifically in the light of the application of NPBT.

Obtaining Protoplasts

Source Tissue

The tissue from which protoplasts are derived is very important for obtaining regenerable starting material. The genotype, organ or tissue, and growth conditions of the plants used can be a significant determinant in regeneration success.

Genotype

Different cultivars or ecotypes can have widely varying success rates in tissue culture and protoplast regenerative capacity. Depending on the species being worked with and the end goal of the application, it is recommended to assess the regenerative capacity of multiple genotypes and select the most suitable for further use.

When comparing four different Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ecotypes (Col-0, Ws-2, No-0, and HR-10), all gave a similar number of protoplasts with an optimized digestion, but differed significantly when comparing optimal protoplast division media, callus induction media, and shoot induction media (Jeong et al., 2021). Ws-2 showed the highest regeneration efficiency, whereas the Col-0, No-0, and HR-10 had relatively ineffective regeneration rates, regardless of efforts to vary the composition of media and tissue culture methods.

Comparison of three different Cyclamen species (C. graecum, C. mirabile, and C. alpinum) found significant differences in protoplast culture and regeneration, including division frequencies (often referred to as plating efficiency) and morphological appearance of regenerating embryos (Prange et al., 2010a). Plants were regenerated from protoplasts derived from embryogenic callus in all three species, but had different efficiencies in microcallus formation and development of somatic embryos. Interestingly, there was no correlation between the regenerative capacity of the source embryogenic callus and the ability of the protoplasts to divide and regenerate, with C. graecum performing the worst in regeneration from callus but showing the highest protoplast division rates.

Organ or Tissue

Different source materials for protoplast isolation can affect the number, size, viability, and regenerative capacity of protoplasts. There are examples of protoplast isolation and regeneration from numerous tissues, including leaves, cotyledons, roots, petioles, hypocotyls, petals, callus, and suspension cultures (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Obtaining Protoplasts.

| Species | Tissue Source | Pre-digestion | Enzyme Composition | Digestion Buffer | Conditions | Yield | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Elm (Ulmus americana) | Cell suspension | None | 0.2% cellulase Onozuka RS, 0.1% Driselase, 0.03% pectolyase Y-23 | 0.5 M mannitol, 2.5 mM MES, CPW salts | 2 h, dark, 25°C | 2 × 106 per ml of packed cell volume | Jones et al. (2015) |

| Amur cork tree (Phellodendron amurense) | Callus | Sliced | 1% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 1% Driselase | 0.6 M mannitol | 8 h | 5.5 x 105 gfw−1, 90% viability | Azad (2012) |

| Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) | Seedlings | Plasmolysis | 1% cellulase Celluclast 1.5 L, 2% carbohydrase Viscozyme L, 1% pectinase Pectinex ultra SP-L | 0.47 M mannitol, 10 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MES | 12 h, dark, 50 rpm, RT | 1 × 107 gfw−1 | Jeong et al. (2021) |

| Banana (Musa paradisiacal) | Embryogenic cell suspension | None | 3.5% cellulase R-10, 1% macerozyme R-10, 0.15% pectolyase Y-23 | 204 mM KCl, 67 mM CaCl2 | 10–12 h, dark, 50 rpm, 27°C | 6 × 106 per ml of packed cell volume | Dai et al. (2010) |

| Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) | Cotelydons | Sliced and Plasmolysis | cellulase, pectinase (concentrations not disclosed) | 0.5 M mannitol, 3 mM MES, CPW salts | Overnight, dark, 30 rpm, 25°C | not disclosed | Jie et al. (2011) |

| Leaves | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 0.5% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.1% pectolyase Y-23 | 0.4 M mannitol, 3 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MES | 18 h, dark, 20 rpm, 25°C | not disclosed, 88% viability | Kiełkowska and Adamus (2019) | |

| Hypocotyls | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 0.5% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.1% pectolyase Y-23 | 0.4 M mannitol, 3 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MES | 18 h, dark, 20 rpm, 25°C | not disclosed, 92% viability | Kiełkowska and Adamus (2021) | |

| Leaves and hypocotyls | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 1% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.1% macerozyme R-10 | 0.8 M sucrose, KM medium | 16–18 h, dark, 30 rpm, 25°C | Leaves: 2 × 106 gfw−1; Hypocotyls: 0.7 × 106 fw−1; 60–90% viability | Kiełkowska and Adamus (2012) | |

| Canola (Brassica napus) | Leaves | Sliced | 1% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.1% macerozyme R-10 | 0.4 M sucrose, K3 medium | 14–18 h, dark, 24°C | 1 x 107 gfw−1 | Sahab et al. (2019) |

| Carrot (Daucus spp.) | Leaves | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 1% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.1% pectolyase Y-23 | 0.6 M mannitol, 5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MES | 14–16 h, dark, 30 rpm, 26°C | not disclosed | Grzebelus and Skop (2014) |

| Leaves and hypocotyls | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 1% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.1% pectolyase Y-23 | 0.6 M mannitol, 5 mM CaCl2, 20 mM MES | 14–18 h, 30 rpm, 26°C | Leaves: 3.21 x 106 gfw−1, 74% viability; Hypocotyls: 0.96 x 106 gfw−1 | Grzebelus et al. (2012) | |

| Leaves | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 1% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.1% pectolyase Y-23 | 0.6 M mannitol, 5 mM CaCl2, 20 mM MES | 12–16 h, dark, 30 rpm, 26°C | 2.8 x 106 gfw−1, 72–93% viability | Maćkowska et al. (2014) | |

| Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis) | Hypocotyls | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 1% cellulase R-10, 0.1% macerozyme R-10 | 0.4 M sucrose, B5 salts and vitamins | 15 h, dark, 24°C | 5.2 x 106 gfw−1 | Sheng et al. (2011) |

| Chicory and Endive (Cichorium intybus and endivia) | Leaves | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 1% cellulase Caylase 345, 0.5% pectinase Caylase M2 | 0.5 M mannitol, 30 mM sucrose, 0.55 mM inositol, 0.05 mM FeNa-EDTA, 1/2 MS macro elements, Heller micro elements, Morel & Wetmore vitamins | 16 h, dark, 25 rpm, 23°C | 1 x 106 gfw−1, 85–95% viability | Deryckere et al. (2012) |

| Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium) | Leaves | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 1.5% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.3% macerozyme R-10, 0.1% Driselase | 0.4 M mannitol, 5 mM MES, CPW salts | 4 h, dark, 40 rpm, 25°C | 6.32 × 105 gfw−1, 91.7% viability | Adedeji et al. (2020) |

| Leaves and callus | Sliced and Plasmolysis | Leaves: 0.5% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.3% macerase R-10, 0.1% Driselase; Callus: 1.5% cellulase Onozuka R- 10, 0.5% macerase R-10, 0.1% Driselase | 0.4 M mannitol | 16 h, dark, 10 rpm, 22°C | not disclosed | Eeckhaut et al. (2020) | |

| Coriander (Coriandrum sativum vars.) | Embryogenic cell suspension | None | 2% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 1% pectinase and 0.2% macerozyme R-10 | 0.6 M mannitol, 5 mM CaCl2 | 14–18 h, dark, 50 rpm | 4.81 × 106 gfw−1, 90-93.8% viability | Ali et al. (2018) |

| Cottonwood (Populus beijingensis) | Cell suspension | None | 1% cellulase Onozaka RS, 1% macerozyme R-10 | 0.6 M mannitol, 5 mM MES, CPW salts | 4–6 h, dark, 80 rpm, 28°C | not disclosed, 90–95% viability | Cai and Kang (2014) |

| Crown imperial (Fritillaria imperialis L.) | Callus | Sliced | 2% cellulase, 0.1% pectinase | 0.5 M mannitol, CPW salts | 8 h, dark, 70 rpm, 25°C | 1.37×105 gfw−1 | Chamani and Tahami (2016) |

| Florist Kalanchoe (Kalanchoe blossfeldiana) | Cultured leaf explants | Sliced | 0.4% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.2% Driselase | 0.4 M mannitol, 100 mM glycine, 14 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MES, MS macro elements | 4 h, dark, 40 rpm, 25°C | 6.0 x 105 gfw−1 | Castelblanque et al. (2010) |

| Gentian (Gentiana decumbens) | Leaves | Plasmolysis | 1% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.5% macerozyme R-10 | 0.5 M mannitol, 5 mM MES, CPW salts | 3–4 h, dark, 50 rpm, 26°C | 9.31 × 105 gfw−1, 84.6% viability | Tomiczak et al. (2015) |

| Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe.) | Embryogenic cell suspension | None | 4.0% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 1.0% macerozyme R-10, 0.1% pectolyase | 0.6 M mannitol, 0.45 M CaCl2, 5 mM MES | 12–14 h, dark, 27°C | 6.27 x 106 gfw−1 | Guan et al. (2010) |

| Leaves and callus suspension | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 1–3% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.5-1% macerozyme, 0-0.5% hemicellulase | 0.5 M mannitol, CPW salts | 10 h at 15°C followed by 6–8 h at 30°C, dark, 53 rpm | not disclosed | Nirmal Babu et al. (2016) | |

| Grape hyacinth (Muscari neglectum) | Embryogenic callus | None | 1% cellulase R-10, 1% Driselase, 0.1% pectolyase Y-23 | 0.5 M mannitol, 5 mM MES | 2 h, dark, 90 rpm, 25°C | 7 × 105 gfw−1 | Karamian and Ranjbar (2011) |

| Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) | Embryogenic callus | None | 2% cellulase Onozuka, 1% macerozyme R-10, 0.05% pectolyase Y-23 | 0.5 M mannitol, 10 mM CaCl2, 5 mM MES | 6 h, shaking | 1 × 107 gfw−1, >80% viability | Bertini et al. (2019) |

| Guava (Psidium guajava) | Leaves | Sliced | 2.4% cellulase, 3% macerase, 0.6% hemicellulase | 0.75 M mannitol, CPW salts | 10 h, dark, 45 rpm, 27°C | 3.7 x 106 gfw−1, >90% viability | Rezazadeh and Niedz (2015) |

| Hydrangea (Hydrangea spp.) | Leaves | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 0.002% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.0005% Driselase, 0.0005% MKC- hemicellulase, and 0.001% pectinase a | 0.35 M sorbitol, 0.35 M mannitol, 9 mM CaCl2, 0.83 mM NaH2PO4, 3 mM MES | 14–18 h, dark, 30 rpm, 25°C | 5.5 × 106 gfw−1, 87% viability | Kästner et al. (2017) |

| Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) | Cotelydons | None | 1% cellulase R-10, 0.5% macerozyme R-10 | 0.45 M mannitol, 20 mM MES, CPW salts | 14 h, dark, 40 rpm, 25°C | not disclosed | Woo et al. (2015) |

| Leaves | Sliced | 1.5% cellulase R-10, 0.3% macerozyme R-10 | 0.4 M mannitol, 20 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 20 mM MES, 0.1% BSA | 4,5 h, dark, 50 rpm | not disclosed | Park et al. (2019) | |

| Lily (Lilium ledebourii) | Leaves | Sliced | 4% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 1% pectinase | 0.7 M mannitol, CPW salts | 24 h, dark, 70 rpm, 25°C | not disclosed | Tahami et al. (2014) |

| Love-in-a-Mist (Nigella damascena L.) | Callus | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 1% cellulase, 0.1% pectolyase | 0.6 M mannitol, 5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MES | 14–16 h, dark, 30 rpm, 26°C | 3 × 105 gfw−1 | Klimek-Chodacka et al. (2020) |

| Oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) | Cell suspension | None | 2% cellulase, 0.5% cellulase Onuzuka R10, 1% pectinase, 0.1% pectolyase Y23 | 0.2 M mannitol, 0.4 M KCl, 45 mM CaCl2 | 14 h, dark, 26°C | 1.14 × 106 gfw−1, 82% viability | Masani et al. (2013) |

| Petunia (Petunia hybrids) | Leaves | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 2% cellulase Onozuka R-10 , 0.6% macerozyme R-10 | 0.6 M mannitol, 10 mM MES, 0.2% BSA | 6 h, dark, 30 rpm, 25 °C | 1.04 × 106 gfw−1, 73.3% viability | Kang et al. (2020) |

| Leaves | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 1.2% carbohydrase Viscozyme, 0.6% cellulase Celluclast, 0.6% pectinase PectinEX | 1 M Manitol, 8 mM CaCl2, 0.1 M MES, 0.1% BSA | 3 h, 40 rpm, 25°C | 6.9 × 106 per 12–16 leaves, 94.3% viability | Yu et al. (2020) | |

| Qin-jiao (Gentiana macrophylla) | Embryogenic cell suspension | None | 2% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.5 % macerozyme R-10, 0.5% hemicellulase | 0.4 M sorbitol, 50 mM CaCl2, 2.5 mM MES | 14–16 h, dark, 30 rpm, 25°C | 6.2 x 106 gfw−1, >90% viability | Hu et al. (2015) |

| Silk tree (Albizia julibrissin) | Leaves and callus | Sliced and Plasmolysis | Leaves: 1.5% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 1% pectolyase Y-23; Callus: 2% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 1% pectolyase Y-23 | 0.7 M mannitol, CPW salts | 6 h (leaves) 16 h (callus), dark, 40 rpm, 25°C | Leaves: 6.31 x 105 gfw−1, 87% viability; Callus: 5.53 x 105 gfw−1, 85% viability | Rahmani et al. (2016) |

| Sowbread (Cyclamen spp.) | Somatic embryos and embryogenic cell suspension | Sliced and Plasmolysis for embryos only | 2% cellulase R-10, 0.5% macerozyme R-10 | 0.35 M sucrose, KM8p macro elements | 16–18 h, dark, 24°C | Suspension cultures: 4.24 x 105 gfw−1; Somatic embryos: 0.57 x 105 gfw−1; Dissected germinated embryos: 3.09 x 105 gfw−1 | Prange et al. (2010b) |

| Embryogenic cell suspension | None | 2% cellulase R-10, 0.5% macerozyme R-10 | 0.35 M sucrose, KM8p macro elements | 16–18 h, dark, 24°C | 1.36 × 106 gfw−1 | Prange et al. (2010a) | |

| Stevia (Stevia rebaudiana) | Leaves | Sliced | 2% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 1.5% macerozyme Onozuka R-10, 0.2% Driselase, 0.1% pectolyase Y-23 | 0.5 M mannitol, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM MES | 4 h, dark, 55 rpm, 25°C | 8.4 x 106 gfw−1, 98.8% viability | Lopez-Arellano et al. (2014) |

| Strawberry (Fragaria ananassa) | Shoots | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 1% cellulase Cellulysin, 0.1% pectinase Macerase | 0.4 M sucrose, K3 medium | 18 h, dark, 20 rpm, 25°C | not disclosed | Barceló et al. (2019) |

| Widow's-thrill (Kalanchoë spp.) | Leaves | Sliced and Plasmolysis | 0.5% cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.1% Driselase | 0.58 M mannitol, 14 mM CaCl2, 93 mM glycine, 2.5 mM MES, 1.65 g/L MS macro elements | 16–18 h, dark, 40 rpm, RT | 10.78 × 105 gfw−1, 60-90% viability | Cui et al. (2019) |

= suspicion of inaccurate magnitude reported.

In cabbage (Brassica oleracea), it was observed that hypocotyl-derived protoplasts yielded more regenerated shoots than leaf-derived protoplasts (Kiełkowska and Adamus, 2012). In a comparison on the regeneration capacity of protoplasts derived from leaves, cotyledons, and callus from coastal medick (Medicago littoralis), leaf protoplast-derived callus was found to have the highest regeneration capacity with a frequency of 20% and cotyledon protoplast-derived callus had a regeneration frequency of 15% (Zafar et al., 1995). In this study, callus-derived protoplasts developed only a few microcolonies that were not tested for regeneration. Embryogenic callus can potentially provide improved regeneration success in cases where somatic tissues fail to produce regenerable protoplasts, e.g. in grapevine (Vitis vinifera) (Bertini et al., 2019).

The age of the source tissue can also be of importance, both for protoplast yield and viability as well as regeneration success. Generally, protoplasts derived from younger tissues perform better in culture. This has been shown for hypocotyls and leaves in cabbage (Kiełkowska and Adamus, 2012) and cell suspension cultures in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) (Masani et al., 2013), for example.

Plant Growth Conditions

The growth conditions of the starting material, including growth media and light, can have a significant effect on the regenerative capacity of protoplasts. An important consideration is that the material needs to be sterile (either grown under aseptic conditions or sterilized upon harvest) in order to be used for further culture of the obtained protoplasts.

In Arabidopsis, plants grown on Gamborg B5 medium and harvested 3 weeks after germination had a larger rosette with nearly twice as many leaves when compared to plant grown on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium, resulting in twice as many protoplasts per harvested plant. However, during protoplast culture, the plants grown initially on MS media showed two to three times higher plating efficiency. And when comparing the photoperiod under which plants were grown, short day (10 h) resulted in a fourfold higher plating efficiency than long day (16 h) (Masson and Paszkowski, 1992).

Examination of cauliflower (Brassica oleracea) leaf protoplast quality of shoots grown in various vessel types found that protoplast yield, viability, division, and shoot regeneration was higher from tissue of plants grown in containers with vented lids compared to containers with closed lids (Chikkala et al., 2009).

Enzymolysis

When it comes to isolating protoplasts, it is not only about obtaining a high number of protoplasts, but also about optimizing their viability and regenerative capacity. Many factors in the enzymolysis procedure may be of influence, including the utilized pretreatment, buffer composition, cell-wall digestion enzymes, incubation conditions, and purification methods (Table 1). Although, to our knowledge, there are not studies on the effect on protoplast regeneration directly for all of the different factors described here, it seems reasonable to assume that effects on the quality (viability) of the isolated protoplasts will translate to an influence on regenerative capacity of the isolated protoplasts.

Pretreatment

Pretreatment of tissue can be used to augment the number of viable protoplasts isolated by increasing the access of the used enzymes to the plant cell wall. This can be achieved through physical disruption of the tissue (e.g. slicing leaf tissue), vacuum infiltration of the enzyme solution, or a preplasmolysis treatment.

Slicing tissue into smaller sections or strips before moving to the enzyme solution allows for more surface area for the enzymes to work, leading to the release of more protoplasts. With rice (Oryza sativa), longitudinal cutting, parallel to the veins, before enzyme digestion resulted in over twice as many viable protoplast as leaves cut in cross section (Lin et al., 2018). Another example of physical disruption is the “Tape-Arabidopsis Sandwich” method (Wu et al., 2009). This method uses tape on both sides of a leaf to add support and allow the removal of the bottom epidermal layer. This protocol has been successfully applied to other Brassicaceae species, including B. oleracea, B. napus, Cleome spinosa, C. monophilla, and C. gynadra (Lin et al., 2018).

In addition to physical disruption, vacuum infiltration of plant tissue with the enzyme solution can be used to ensure that the enzymes are able to reach more of the cells, which could increase protoplast yield. In both apple (Malus domestica) and grapevine, vacuum infiltration was a part of the optimization of the protoplast isolation procedure to obtain the highest number of viable protoplasts per gram of fresh weight (Osakabe et al., 2018).

Preplasmolysis treatment is used to shrink the protoplasts away from the cell wall before introducing the enzyme solution. This is thought to avoid damage to the cell membrane. When comparing protoplasts isolated from birdsfoot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus) tissue with and without preplasmolysis, the pretreated protoplasts had roughly five times more cell wall formation than the nontreated after 3 days of culture. After 1 week, the viability of the nontreated protoplasts decreased significantly (Vessabutr and Grant, 1995).

Enzyme Solution Buffer

The buffer for the enzyme solution is critical for optimal enzyme activity and ensuring a high number of viable protoplasts. The buffer solution typically includes KCl; CaCl2; mannitol, sorbitol, or salts as osmolytes; MES (2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid) as pH buffer; BSA (bovine serum albumin) as an alternate target for proteases that may degrade the enzymes; and β-mercaptoethanol as a reducing agent (Table 1). Frearson et al. (1973) first formulated a combination of salts that many still use, called the cell and protoplast washing (CPW) salts. This basal salt solution is often modified with the addition of mannitol or sorbitol for osmotic pressure and different enzymes for optimal protoplast isolation (Jie et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2015; Tomiczak et al., 2015).

Proper osmolality is crucial in order to ensure the survival of the cells and provide an environment for potential cell wall formation and division, leading to regeneration. Protoplast development has been shown to be inhibited by excess osmotic pressure during isolation and culture by impairing metabolism (Ruesink, 1978) as well as division and cell wall regeneration (Pearce and Cocking, 1973).

Enzyme solutions with the same (or similar) composition as the subsequent protoplast culture medium have also been used successfully in protoplast regeneration applications. For example sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) callus protoplasts were isolated using Kao and Michayluk salts in the enzyme solution (Dovzhenko and Koop, 2003); Mango (Mangifera indica) pro-embryogenic mass-derived protoplasts were isolated using an enzyme solution containing Gamborg B5 and Murashige and Skoog salts (Ara et al., 2000); petunia (Petunia spp.) and calibrachoa (Calibrachoa spp.) leaf protoplasts were isolated with Kao and Michayluk and Gamborg B5 salts in the solution (Meyer et al., 2009).

Enzymes

Many commercially available cell-wall degrading enzymes (or enzyme mixtures) are used for the isolation of protoplasts. They differ in their substrates as well as the purity or combination of the enzymes in the extract. Enzymolysis is generally achieved using both cellulases and hemicellulases (e.g. beta-glucanases, xylanases, protopectinases, polygalacturonases, pectin lyases, and pectinesterases). Some of the most commonly used enzymes or enzyme mixtures are Cellulase R-10, Macerozyme R-10, and Pectolyase Y-23 (Table 1). The manufacturer/supplier of the enzymes may be a factor in the success rates (personal experience and communication with others).

The effect of different enzyme combinations and concentrations were tested on the isolation of protoplasts from stevia (Stevia rebaudiana) leaves (Lopez-Arellano et al., 2014). The optimized enzyme solution contained 2% Cellulase R-10, 1.5% Macerozyme Onozuka R-10, 0.2% Driselase, and 0.1% Pectolyase Y-23. When the Cellulase R-10 was decreased to 1% or increased to 3%, there was a significant drop in both the yield and viability of the protoplasts. There was also a lower viability when pectolyase Y-23 was not present. When isolating protoplasts from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaves, it was found that Pectolyase Y-23 was 20 times more effective than Macerozyme R-10 (Nagata and Ishii, 1979). This was determined to be due to the Pectolyase Y-23 having 50 times stronger endopolygalacturonase activity.

As the cost of lab-grade enzymes can be prohibitive, the use of food-grade cell wall degrading enzymes was investigated as a low-cost alternative for the isolation of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) leaf protoplasts (Burris et al., 2016). It was determined that using a combination of Rohament CL with Rohapect 10 L and Rohapect UF (cellulases and pectinases commonly used in brewing and juicing) yielded up to 8.4 × 105 protoplasts per gram of leaf tissue.

Although (to our knowledge) there have been no systematic analyses of whether the combination of enzymes used may influence the division rates and regenerative capacity of the produced protoplasts, one can imagine that there could well be an effect. The enzymes themselves, the crude extracts, as well as the cell-wall degradation products they produce can all be recognized by plant cells as pathogenic elicitors, to a greater or lesser extent, depending on the sensitivity of the genotype used to the different enzymes and extracts employed. Protoplast yield and viability may well be a good measure for protoplast isolation, but it could be the case that an enzyme combination that does not necessarily give the highest yield and viability could be more suitable for subsequent regeneration of the protoplasts.

Enzymolysis Conditions

Conditions during protoplast isolation (i.e. duration, temperature, light, and agitation) can play a significant role in the subsequent yield, viability and regenerative capacity of the protoplasts.

The length of a digestion period typically ranges from 2 to 18 h (Table 1). The duration of digestion needs to be long enough to release sufficient numbers of protoplasts, but not too long as to decrease the viability due to cell damage or the lack of nutrients and growth regulators in the enzymolysis solution. For example, when comparing 4, 8, and 12 h digestion duration of crown imperial (Fritillaria imperialis) callus, the yield and viability were highest at 8 h (Chamani and Tahami, 2016).

Temperature also plays an important role in protoplast yield and viability. Room temperature is the most commonly used, although there are examples of higher temperatures being employed (Table 1). There could be effects on enzyme activity (and protoplast yield) as well as protoplast viability and regenerative capacity. Intuitively, it may be preferable to use a temperature that is close to that used for the growth of the source material and/or subsequent protoplast culture conditions, in order to minimize temperature fluctuations or shocks. Conversely, perhaps a particular temperature treatment may actually benefit regenerative capacity.

Digestion in a light or dark condition may additionally influence the protoplast isolation, with most choosing dark conditions (Table 1). This may avoid the production of free radicals and photoinhibition in cells containing chloroplasts. Although there are also examples where digestion under light performed better than in the dark. In geranium (Pelargonium x hortorum) leaf protoplast isolation, protoplast yield and viability were increased when the digestion occurred in light; in the dark, the enzymes were efficient but most of the released protoplasts had burst (Nassour and Dorion, 2002). The protoplasts isolated from the light condition were regenerated into plants, but the effect of light or dark condition during digestion on the regeneration capacity was not investigated.

Agitation of the enzymatic solution on a gyratory shaker during the protoplast digestion can increase the protoplast yields. Typically, speeds range from 0 to 90 rpm, with the average being around 40 rpm (Table 1). Alternatively, the agitation can be implemented only at the end of the digestion period to facilitate the release of protoplasts from the cell wall remnants.

Again, protoplast yield and viability may well be a good measure, but it could be the case that digestion conditions that do not necessarily give the highest yield and viability could be more suitable for subsequent regeneration of the protoplasts.

Purification

Following enzymolysis, separation of the protoplasts from undigested tissue, cell wall debris, and dead cells can be an important factor in the culture of the protoplasts. Debris and dead cells may elicit negative effects in the living protoplasts that will inhibit their division and development, e.g. in kalanchoe (Kalanchoe blossfeldiana) (Castelblanque et al., 2010). Filtration and sucrose cushions, or floatation through a density gradient, are commonly used techniques.

Protoplast Culture

Culture Media

Protoplast culture media are central to protoplast division and plant regeneration. The appropriate macro-, micro-nutrients, and additives, such as plant growth regulators, osmotic stabilizers, medium solidifiers, and supplements, are essential in protoplast culture.

Nutrients

Optimal protoplast culture media vary widely, depending on the genotype and source tissue used (Table 2). Common medium formulations (such as MS (Murashige and Skoog, 1962), Gamborg (B5) (Gamborg et al., 1968), Kao and Michayluk (KM (Kao and Michayluk, 1975)), Y3 (Eeuwens, 1976), or Nitsch (Nitsch and Nitsch, 1969)), or slight modification thereof, are often used in protoplast culture. Although there are also examples of custom formulations, e.g. TM2G for tomato (Solanum lycopersicon) protoplast culture (Shahin, 1985). This is also a case where the manufacturer/supplier of the premixed media may be a factor in the success rates (personal experience and communication with others). When establishing and optimizing a protoplast culture procedure, it is prudent to assay an array of medium formulations for suitability.

TABLE 2.

Protoplast Culture.

| Species | Protoplast Density | Protoplast Culture Medium | Protoplast Culture PGRs | Time to Division | Time to Microcalli | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Elm (Ulmus americana) | 2 × 105 protoplasts/ml | Agarose beads (1.6% SeaPlaque agarose); liquid KM5/5 medium (KM medium, 10% mannitol, 2.56 mM MES) | 5.4 μM NAA, 5 μM BAP | 2-6 days | Not disclosed | Jones et al. (2015) |

| Amur cork tree (Phellodendron amurense) | 4-6 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Solid MS medium (3% sucrose, 0.2% Gellan gum) | 4 μM NAA, 2 μM BAP | 2 weeks | 2 months | Azad (2012) |

| Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) | 1 x 106 protoplasts/ml | Thin alginate layer (1.4% sodium alginate); liquid PIM medium (B5 medium, 2% sucrose, 6% myo‐inositol) | 2.3 μM 2,4-D, 8.9 μM BAP | 7 days | 28 days | Jeong et al. (2021) |

| Banana (Musa paradisiacal) | 1 × 106 protoplasts/ml | Nurse culture: protoplasts in liquid M5 (MS medium, 4.5% sucrose, 4.1 μM biotin, 680 μM glutamine, 0.01% malt extraction) with a sterilized nitrocellulose filter seperating the feeder layer (MS medium, Morel vitamins, 4% sucrose, 0.25% myo-inositol, 9.05 μM 2,4-D, 2.8 mM glucose, 278 mM maltose, 1.2% agarose) containing the nurse cells (M. acuminate cv. Mas (AA)) | 4.5 μM 2,4-D | 4-5 days | 1 month | Dai et al. (2010) |

| Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) | 1-2 x 105 protoplasts/ml | agarose embedding culture (MS medium (without NH4NO3), 8% myo-inositol, 3% sucrose, 1.19 mM thiamine), media with (20.6 mM ammonia (NH4+), 39.4 mM nitrate ions (NO3-)) added after 2 weeks | 9.05 μM 2,4-D, 2.2 μM BAP | 3-5 days | 4 weeks | Jie et al. (2011) |

| 4 × 105 protoplasts/ml | Alginate layers (1.4% alginic acid sodium salt); liquid culture medium (B5 medium, KM vitamins, 7.4% glucose, 0.025% casein hydrolysate, 0.1 μM PSK-α) | 0.45 μM 2,4-D, 0.91 μM zeatin | 3,4 days | 3 weeks | Kiełkowska and Adamus (2019) | |

| 4 × 105 protoplasts/ml | Alginate layers (1.4% alginic acid sodium salt); liquid culture medium (B5 medium, KM vitamins, 7.4% glucose, 0.025% casein hydrolysate, 10 μM putrescine) | 0.45 μM 2,4-D, 1 μM zeatin | 3-5 days | 4 weeks | Kiełkowska and Adamus (2021) | |

| 4 × 105 protoplasts/ml | Alginate layers (1.4% sodium alginate); CPP liquid medium (KM medium, MS FeEDTA, B5 vitamins, 7.4% glucose, 0.025% casamino acids) | 0.45 μM 2,4-D, 0.91 μM zeatin | 3,4 days | 4 weeks | Kiełkowska and Adamus (2012) | |

| Canola (Brassica napus) | 5 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Agarose (0.3% Sea-Plaque agarose) or Alginate (0.5% sodium alginate) Beads; liquid medium (combination of K3, H, and A mediums) | 5.4 μM NAA, 0.45 μM 2,4-D, 0.89 μM BAP | 6 days | 3,4 weeks | Sahab et al. (2019) |

| Carrot (Daucus spp.) | 4 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Thin alginate layer; liquid CPP (KM medium, B5 vitamins, 7.4% glucose, 0.025% casein enzymatic hydrolysate, 100 nM PSK-α, 0.88 mM cefotaxime, 0.01-0.05% antibiotic (cefotaxime or timentin)) | 0.45 μM 2,4-D, 0.91 μM zeatin | 5 days | Not disclosed | Grzebelus and Skop (2014) |

| 4 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Calcium alginate layers (1.4% alginic acid sodium salt); CPP liquid medium (KM medium, B5 vitamins, 7.4% glucose, 0.025% casein hydrolysate) | 0.45 μM 2,4-D, 0.91 μM zeatin | 3 days | 3-6 weeks | Grzebelus et al. (2012) | |

| 4 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Thin alginate layer; liquid CPP (KM medium, B5 vitamins, 7.4% glucose, 0.025% casein hydrolysate, 100 nM PSK-α, 0.88 mM cefotaxime, 0.3 mM timentin) | 0.45 μM 2,4-D, 0.91 μM zeatin | 4-8 days | Not disclosed | Maćkowska et al. (2014) | |

| Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis) | 2 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Nurse culture: protoplasts in solid 1/2 medium (B5 medium, 4.5% sorbitol, 4.5% mannitol, 0.2% glucose, 0.2% agarose), suspended in liquid MS medium (7.3% mannitol) containing nurse cells (tuber mustard) | 2.7 μM NAA, 4.5 μM 2,4-D, 2.2 μM BAP | 3,4 days | 21 days | Sheng et al. (2011) |

| Chicory and Endive (Cichorium intybus and endivia) | 5 x 104 protoplasts/ml | Low melting point agarose (LMPA) beads (0.25% LMPA); MC1 liquid medium (1/2 MS macro elements, Heller micro elements, Morel & Wetmore vitamins, 9% mannitol, 1% sucrose, 1.39 mM inositol, 2.55 mM glutamine, 0.05 mM FeNa-EDTA). After 5 days, MC1 liquid medium replaced with MC2 liquid medium (1/2 MS macro elements, Heller micro elements, Heller KCl, Morel & Wetmore vitamins, 6% mannitol, 1% sucrose, .55 mM inositol, 5.1 mM glutamine, 0.05 mM FeNa-EDTA) | MC1: 10.75 μM NAA, 4.45 μM BAP; MC2: 2.7 μM NAA, 2.2 μM BAP | Not disclosed | 14 days | Deryckere et al. (2012) |

| Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium) | 1 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Liquid medium (1/2 MS medium (without NH4NO3), 7.2% mannitol, 1% sucrose, 5.13 mM MES, 0.02% activated charcoal) | 10.75 μM NAA, 4.45 μM BAP | 4,5 days | 5 weeks | Adedeji et al. (2020) |

| 1 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Liquid culture (1/2 MS salts (without NH4NO3), KM vitamins, 7.2% mannitol, 1% sucrose, 3.42 mM glutamine, 0.83 mM inositol, 5.13 mM MES) | 10.75 μM NAA, 2.2 μM BAP | <1 week | 5,6 weeks | Eeckhaut et al. (2020) | |

| Coriander (Coriandrum sativum vars.) | 2 × 105 protoplasts/ml | Liquid MS medium | 4.5 μM 2,4-D | Not disclosed | Not disclosed | Ali et al. (2018) |

| Cottonwood (Populus beijingensis) | 2 × 105 protoplasts/ml | Thin liquid culture (MS medium (without NH4NO3), 10.8% glucose) | 9.05 μM 2,4-D, 0.89 μM BAP | 4,5 days | 5 weeks | Cai and Kang (2014) |

| Crown imperial (Fritillaria imperialis L.) | 1 × 105 protoplasts/ml | Liquid MS medium (MS medium, 9% mannitol, 0.02% casein hydrolysate) | 2.3 μM 2,4-D, 4.45 μM BAP | 48 h | 3-4 weeks | Chamani and Tahami (2016) |

| Florist Kalanchoe (Kalanchoe blossfeldiana) | 1 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Liquid BMb medium (macronutrients (5 mM NH4NO3, 15 mM KNO3, 3 mM CaCl2, 1.5 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM KH2PO4), MS micronutrients, SH vitamins (Shahin, 1985), 5.8% mannitol, 4.45% sucrose, 28 mM myo-inositol, 25 mM xylitol, 0.3 mM ascorbic acid, 0.05 mM adenine hemisulfate, 0.5 mM MES) | 5.4 μM NAA, 2.3 μM 2,4-D, 2.2 μM BAP | 5-7 days | 30 days | Castelblanque et al. (2010) |

| Gentian (Gentiana decumbens) | 1 × 105 protoplasts/ml | Agarose beads (0.8% Sea Plaque Agarose); PCM liquid medium (MS medium (without NH4NO3), 3% glucose, 9% mannitol, 20.53 mM glutamine, 0.8% Sea Plaque Agarose) | 10.75 μM NAA, 0.45 μM TDZ | 3-5 days | 10-12 weeks | Tomiczak et al. (2015) |

| Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe.) | 1 x 106 protoplasts/ml | Shallow liquid MS medium (MS medium, 9% mannitol, 0.05% casein hydrolysate) | 4.5 μM 2,4-D, 0.93 μM kinetin | 2-4 days | 10-12 weeks | Guan et al. (2010) |

| Not disclosed | Liquid medium (MS medium, 7% mannitol, 2% sucrose) | 2.7 μM NAA, 2.3 μM 2,4-D, 2.2 μM BAP | Not disclosed | Not disclosed | Nirmal Babu et al. (2016) | |

| Grape hyacinth (Muscari neglectum) | 1 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Nurse culture: protoplasts were isolated in alginate beads (1% sodium alginate), suspended in liquid culture (MS medium, 9% mannitol, 0.57 mM ascorbic acid) with nurse cells (same species, 1 × 10^6 protoplasts/ml) also in alginate beads | 5.4 μM NAA, 4.45 μM BAP | 4-5 days | 4-5 weeks | Karamian and Ranjbar (2011) |

| Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) | 1 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Disc-cultures: protoplasts in solid Nitsch’s medium (5.4% glucose, 3% sucrose, 0.2% gellan gum) suspended in liquid Nitsch’s medium (5.4% glucose, 3% sucrose, 0.3% activated charcoal) | 10.75 μM NAA, 2.2 μM BAP | 10 days | Not disclosed | Bertini et al. (2019) |

| Guava (Psidium guajava) | 1 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Alginate beads; liquid culture media (MS medium (without NH4NO3), 3% sucrose, 59.3 μM thiamine, 48.6 μM pyridoxine, 16.25 μM nicotinic acid, 22.8 μM pantothenic acid, 0.17 mM ascorbic acid, 10.25 μM glutamine, 0.56 mM myo-inositol, 0.43 mM proline) | 5.4 μM NAA | Not disclosed | 7 weeks | Rezazadeh and Niedz (2015) |

| Hydrangea (Hydrangea spp.) | 1 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Liquid PPM1 media (MS medium, MW vitamins, 0.5% sucrose, 9.5% mannitol, 0.5% PVP 10, 3.48 mM MES, 0.6 mM Timentin, 1.4 μM ascorbic acid, 0.13 mM citric acid, 67 nM Karrikinolide) | 5.4 μM NAA, 2.2 μM BAP | 3-15 days | 3 weeks | Kästner et al. (2017) |

| Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) | 2.5 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Agarose layers (1.2% agarose); liquid medium (1/2 B5 medium, 10.3% sucrose, 3.38 mM CaCl2, 50 μM NaFe-EDTA, 1.67 mM sodium succinate, 0.51 mM MES) | 0.9 μM 2,4-D, 1.33 μM BAP | Not disclosed | 3 weeks | Woo et al. (2015) |

| 5 days | 4 weeks | Park et al. (2019) | ||||

| Lily (Lilium ledebourii) | 1 × 106 protoplasts/ml | Liquid medium (MS medium, 9% mannitol, 0.2% yeast extract) | 4.5 μM 2,4-D, 0.93 μM kinetin | 48 h | 20 days | Tahami et al. (2014) |

| Love-in-a-Mist (Nigella damascena L.) | 4 × 105 protoplasts/ml | Alginate layers; CPP liquid medium (KM medium, B5 vitamins, 7.4% glucose, 0.025% casein hydrolysate) | 5.4 μM NAA, 9.3 μM kinetin | 10 days | Not disclosed | Klimek-Chodacka et al. (2020) |

| Oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) | 5.7 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Agarose bead culture (0.6% SeaPlaque agarose); Y3A liquid medium (2 μM GA3) | 10 μM NAA, 2 μM 2,4-D, 10 μM IAA, 2 μM IBA, 10 μM Zea, 2 μM GA3 , 10 μM BA and 2 μM 2iP | 9 days | Not disclosed | Masani et al. (2013) |

| Petunia (Petunia hybrids) | 1 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Liquid medium (KM medium, B5 vitamins, 10.9% mannitol, 1.0% sucrose, 5.13 mM MES) | 5.4 μM NAA, 4.45 μM BAP | 3 days | 4 weeks | Kang et al. (2020) |

| 2.5 × 105 protoplasts/ml | Liquid medium (MS medium, 6% myo-inositol, 2% sucrose) | 9.05 μM 2,4-D, 2.2 μM BAP | 1 day | 3-4 weeks | Yu et al. (2020) | |

| Qin-jiao (Gentiana macrophylla) | 3–5 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Agar-pool culture: protoplasts in liquid P1 (MS (without NH4NO3), 5.5% mannitol, 2% sucrose, 1% glucose, 20.53 mM glutamine, 0.05% casein hydrolysate) surronded by agar-solidified P1 (0.85% agar) | 9.05 μM 2,4-D, 2.2 μM BAP | 3-4 days | 3-4 weeks | Hu et al. (2015) |

| Silk tree (Albizia julibrissin) | 3-5 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Agarose layers (1.4% SeaPlaque agarose); liquid KM8p medium (KM medium, 8% sucrose, 10.25 mM MES) | 2.7 μM NAA, 2.2 μM BAP | 30-48 h | 4 weeks | Rahmani et al. (2016) |

| Sowbread (Cyclamen spp.) | 1.5 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Alginate films (1.15% sodium alginate); modified liquid KM8p medium (3.75 mM NH4NO3, 8.11 mM CaCl2) | 2.3 μM 2,4-D, 1 μM 2iP | 24-48 h | Not disclosed | Prange et al. (2010b) |

| 1.5 × 105 protoplasts/ml | Species dependent: Agarose lense (1.5% LM agarose) or Alginate film (1.15% sodium alginate) in liquid medium, either 8 pmC.1 or 8 pmC.2 (modified KM8p, 3.75 mM NH4NO3, 8.11 mM CaCl2) | 8 pmC.1: 4.5 μM 2,4-D, 0.4 2 μM 2iP; 8 pmC.2: 2.3 μM 2,4-D, 1 μM 2iP | 24-48 h | Not disclosed | Prange et al. (2010a) | |

| Stevia (Stevia rebaudiana) | 5 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Agarose bead culture (0.6% SeaPrep agarose); liquid modified KM8p medium (5.1% sucrose, 5.5% mannitol) | 5.4 μM NAA, 0.9 μM 2,4-D, 2.28 μM zeatin | 2,3 days | 14 days to microcolonies | Lopez-Arellano et al. (2014) |

| Strawberry (Fragaria ananassa) | 2 × 105 protoplasts/ml | Agarose beads (0.6% agarose); modified KM8p liquid medium (7.2% glucose) | 5.4 μM NAA, 1.14 μM TDZ | Not disclosed | 3 weeks | Barceló et al. (2019) |

| Widow's-thrill (Kalanchoë spp.) | 1 x 105 protoplasts/ml | Liquid medium (KM medium, Schenk and Hildebrandt (1972) vitamins, 5% mannitol, 4% sucrose, 0.5% myo-inositol, 19.7 mM xylitol, 2.56 mM MES, 0.28 mM ascorbic acid, 27.1 μM adenine hemisulfate, 0.15 mM timentin) | 5.4 μM NAA, 2.3 μM 2,4-D, 2.2 μM BAP | 3-7 days | 8 weeks | Cui et al. (2019) |

In a comparison of 14 formulations based on MS, KM, and Y3 media for oil palm cell suspension-derived protoplast division, Y3-based medium gave the fastest cell wall formation, quickest division, and highest division frequency (Masani et al., 2013). Amur cork tree (Phellodendron amurense) stem protoplasts were cultured in MS, half-strength MS, and Woody Plant Medium (WPM), and culture in full-strength MS medium resulted in the highest colony formation rate (Azad, 2012).

Protoplast cultures also need a carbon source for energy metabolism, typically sucrose or glucose and to a lesser degree mannitol or sorbitol (Table 2). Comparing the effect of 1 and 2% of either glucose or sucrose as the carbon source for chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium) leaf protoplast culture, 1% sucrose performed best (Adedeji et al., 2020). Although 2% sucrose resulted in the highest division rate, there was no subsequent colony formation. Only 1% sucrose and 2% glucose led to microcallus formation, with 1% sucrose more rapidly producing larger microcalli. For Arabidopsis seedling protoplast culture, three different variations of supplements with B5 medium and vitamins were tested for protoplast proliferation (Jeong et al., 2021). Myo-inositol as the primary carbon source along with sucrose resulted in the highest proliferation rate across four the different Arabidopsis ecotypes. A simplification of KM8p medium with the removal of all of the sugars (fructose, ribose, xylose, mannose, rhamnose, cellobiose, sorbitol and mannitol) except glucose still resulted in protoplast division that led to callus and embryo formation from carrot (Daucus carota) leaf protoplasts (Grzebelus et al., 2012).

Osmotic Pressure

Osmotic pressure is an important aspect of protoplast culture media. Generally, mannitol, sorbitol, sucrose, glucose, myo-inositol or a combination of these components is used to ensure the proper osmolarity. Determining the proper solute concentration is critical for the protoplast survival and division rates. Generally, the concentration of the major osmoticum used in the initial protoplast culture medium varies from 0.1 to 0.8 M (Table 2). Intuitively, it seems that having a comparable osmolarity between enzymolysis and initial culture conditions would expose the protoplasts to less osmotic shock upon transfer to culture medium and benefit their viability and vigor.

For cabbage cotyledon protoplasts, myo-inositol was a better osmotic regulator than mannitol (Jie et al., 2011). It is theorized that myo-inositol may be advantageous to both carbohydrate metabolism in cell walls and inositol metabolism in cell membranes in protoplast culture. However, whether these advantages are gained with a small addition of myo-inositol with a different primary osmoticum or if a large quantity of myo-inositol is needed has yet to be determined.

Osmolarity is commonly decreased gradually as the protoplast reform their cell walls and begin to divide. For example, gradually reducing the osmolarity for oil palm cell suspension protoplast cultures doubled the number of microcalli (Masani et al., 2013). In gentian (Gentiana decumbens) leaf protoplast culture, the osmolarity of the liquid medium around agarose beads was decreased by reducing the mannitol concentration from 0.5 to 0.33 M during the fifth and sixth week of culture, followed by another decrease to 0.17 M mannitol in the seventh and eighth week, and no mannitol for the subsequent weeks (Tomiczak et al., 2015). In chrysanthemum protoplast culture, after the first week in liquid culture medium, myo-inositol was omitted from the refresh medium and mannitol concentrations were dropped from the initial 0.4 M to 0.32, 0.21, and 0.11 M for weeks 2, 3, and 4, respectively (Eeckhaut et al., 2020).

Plant Growth Regulators

Plant growth regulators, particularly cytokinins and auxins, are essential for the growth of microcalli from protoplasts. Additionally, gibberellic acid (GA3) has been shown to be beneficial in some cases. The most common cytokinins are 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP), zeatin, kinetin, isopentenyl adenine (2iP), and thidiazuron (TDZ). The most common auxins are indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), and naphthalene acetic acid (NAA). Optimal concentrations, combinations, and ratios vary widely, depending on the genotype and source tissue of the protoplasts (Table 2).

A ratio of a relatively higher concentration of auxin with a lower concentration of cytokinins was effective for microcallus formation from populus (Populus beijingensis) cell suspension protoplasts (Cai and Kang, 2014). Conversely, in kalanchoe leaf protoplast culture, a higher cytokinin to auxin ratio resulted in better proliferation and microcallus formation; having cytokinin exclusively resulted in slow growth and the microcalli eventually died (Castelblanque et al., 2010).

Coconut water is a natural source of plant growth regulators, both auxin (IAA) and cytokinins (various) as well as other phytohormones, such as gibberellins, and other supplements, such as vitamins and minerals, that have been found to be beneficial in plant tissue culture (Yong et al., 2009). As a supplement in corn (Zea mays) embryogenic callus protoplast culture, coconut water led to a high efficiency of microcallus formation, with a 2% coconut water addition producing the most microcalli (Imbrie-Milligan et al., 1987). Coconut water was also found to increase protoplast cell division in orchid (Phalaenopsis spp.) callus protoplasts (Kobayashi et al., 1993).

Additional Supplements

Additional supplements, such as polyvinylpyrrolidone, antioxidants, activated charcoal, silver nitrate, antibiotics, complex organics, amino acids, polyamines, conditioned medium, and peptide growth factors, can be added to the media to support protoplast division and microcallus formation (Table 2).

Antioxidants, such as ascorbic acid, citric acid, reduced glutathione, and L-cysteine, can be used to mitigate the inhibitory effects of reactive oxygen species. In oil palm protoplast regeneration, it was found that 200 mg/L ascorbic acid gave the greatest indication of further cell growth and development with the microcalli turning yellow and developing into embryogenic calli (Masani et al., 2013). With this supplementation, two types of embryogenic callus were observed, compact and friable embryogenic callus, which were both able to further develop into somatic embryos and regenerate into plantlets.

Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) is used to adsorb phenolics. While phenolics may be beneficial for plant defense (Bhattacharya et al., 2010), an accumulation during protoplast culture has been found to lead to oxidative browning of the culture medium, inhibiting protoplast growth and division (Reustle and Natter, 1994; Prakash et al., 1997). There has also been reports of PVP suppressing tissue browning and improving callus formation in peony (Paeonia lactiflora) petal explant tissue culture (Cai et al., 2020). Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP), a highly cross-linked version of PVP, has also been found to inhibit tissue necrosis in Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana) callus culture (Tang et al., 2004), as well as preventing browning better than PVP in guar (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba) cotyledon protoplast culture (Saxena and Gill, 1986). When PVP was added to the PVPP culture of guar cotyledon protoplasts, not only was it found to enhance the necrosis inhibition, but it also improved the protoplast division frequency. Another compound known to decrease tissue browning is 2-aminoindane-2-phosphonic acid (AIP), which is a reversible inhibitor of phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), an enzyme necessary for polyphenol production (Appert et al., 2003). While the inhibition of PAL was able to increase the cell wall digestibility and facilitate sustained cell division in American elm (Ulmus americana), extended inhibition results in decreased shoot growth in tissue culture (Jones et al., 2012). This decrease in plant growth due to PAL inhibition from AIP has also been seen in birch (Betula pubescens) (Nybakken et al., 2007) and St. John’s wort (Hypericum spp.) (Klejdus et al., 2013). It could be hypothesized that an early addition of AIP will increase the likelihood of protoplast survival, but it should not be used for an extended period as to disrupt the callus and shoot growth, as described for American elm protoplast regeneration (Jones et al., 2015).

Activated charcoal is a commonly used additive employed for its ability to adsorb inhibitory elements, such as phenolics and reactive oxygen species, that can impede protoplast division. Adedeji et al. (2020) found that the ideal concentration of activated charcoal for chrysanthemum leaf protoplast regeneration was 0.02% (w/v) and adding a higher concentration of 0.1% resulted in agglutination of the protoplasts, causing them to die before entering the microcolony stage. In primrose (Primula spp.) cell suspension-derived protoplast culture, the addition of 0.1% PVP did not induce callus formation; however, the addition of activated charcoal did (Mizuhiro et al., 2001).

Silver nitrate (AgNO3), an inhibitor of ethylene action, has been shown in some cases to increase callus formation and regeneration efficiency as well as effect protoplast isolation efficiency. The culture of hypocotyl protoplasts from several Brassica species was markedly improved by the addition of silver nitrate in the culture medium (Pauk et al., 1991; Hu et al., 1999). With rice (Oryza sativa) suspension cultures, the addition of silver nitrate during protoplast isolation reduced protoplast yield but increased the frequency of colony formation (Ishii, 1988).

Antibiotics may be used to avoid endogenous or exogenous contamination, however they can either inhibit or stimulate explant growth and development with the direct causation not yet understood (Qin et al., 2011). A study analyzing the effects of three β-lactam antibiotics (cefotaxime, carbenicillin, and timentin) at different concentrations on carrot seedling protoplasts found that, while plating efficiencies decreased in all antibiotic concentrations higher than 100 mg/L, cefotaxime and timentin in the range of 100–500 mg/L increased regeneration efficiency (Grzebelus and Skop, 2014). Timentin was used with Hydrangea leaf protoplasts to limit the endophytes and it was observed that in antibiotic-free medium, the protoplasts rebuilt the cell wall faster and divided earlier, but callus was only formed in medium with antibiotics (Kästner et al., 2017).

The exact composition of complex organics, such as casein hydrolysate, casamino acids, coconut water, and yeast extract, is typically undefined and varies depending on the manufacturer/supplier and potentially the batch. However, the amino acids, hormones, vitamins, fatty acids, carbohydrates, and other growth supplements they provide may enhance growth and regeneration of plants (Bhatia, 2015). The addition of casein hydrolysate was initially shown to give a more consistent high rate of microcallus formation from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) protoplasts (Galun and Raveh, 1975), and is currently an addition to protoplast culture media regularly (Table 2).

Polyamines can regulate plant growth and stress responses through many means, including increasing antioxidant activity and regulating oxidative stresses (Chen et al., 2019). In a comparison of the exogenous addition of the polyamines putrescine, spermidine, and spermine on sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) cell suspension-derived protoplasts, spermine resulted in the highest plating efficiency, likely due to its stronger inhibitory effect on ethylene production (Majewska-Sawka et al., 1997). Polyamines exogenously applied in different concentrations on cabbage hypocotyl protoplast culture obtained the highest frequency of shoot organogenesis from protoplasts treated with putrescine (Kiełkowska and Adamus, 2021). However, the addition of putrescine had no effect on the culture or regeneration of Love-in-a-Mist (Nigella damascena) callus protoplasts (Klimek-Chodacka et al., 2020).

Conditioned medium (spent liquid medium used for cell-suspension cultures that is filtered and subsequently used as a supplement for protoplast culture) may contain compounds that encourage growth and mitotic activity. Fresh conditioned medium from cell-suspension cultures significantly increased the plating efficiency in chrysanthemum leaf protoplast culture (Zhou et al., 2005).

Phytosulfokine (PSK), specifically PSK-α, is a peptide that was originally detected secreted in conditioned medium, but was later found in whole plants (Yang et al., 1999). It was found to promote cell growth, enhance callus growth as well as adventitious root and bud formation, and improve somatic embryogenesis in multiple species, and has also been shown to enhance protoplast regeneration in carrot (Maćkowska et al., 2014) and cabbage (Kiełkowska and Adamus, 2019). With carrot leaf protoplasts, application of PSK-α during the initial culture resulted in a four-fold increase in regenerated plants (Maćkowska et al., 2014). PSK-α was shown to be both genotype- and dose-dependent and did not require a constant presence to maintain cell divisions in cabbage leaf protoplasts (Kiełkowska and Adamus, 2019). Not only was the PSK-α found to promote cell proliferation, but it also increased differentiation and organogenesis in five of the six cabbage accessions tested.

Protoplast Culture Conditions

Protoplast culture conditions, such as the use of liquid or semi-solid medium, temperature and light, cell density, or the presence of nurse cultures, can have a significant effect on the division and microcallus formation potential of protoplasts.

Liquid Vs. Semi-solid Medium

When it comes to determining the solidity of the media to use with protoplast culturing, there are multiple factors to consider, including imaging potential, media refreshing, toxin accumulation, and cell aggregation.

Liquid medium is the most straightforward to make since it requires no agar manipulation. However, it faces a multitude of challenges. With imaging, unless each cell is in a separate space, it is impossible to track the growth of an individual cell. There is also the potential for aggregation of cells to form a non-homogeneous callus, possibly resulting in chimerism of the regenerated plants. Aggregation can also cause a local accumulation of toxic substances released from dying cells that may inhibit the growth of neighboring cells (Deryckere et al., 2012).

To avoid cell agglutination, embedding the protoplasts in semi-solid medium can ensure physical separation of cells. The embedding medium will typically contain agar, agarose, or alginate as a solidifier. Alginate is favorable for heat-sensitive protoplasts because the gelling is induced by exposure to calcium ions rather than the need to heat the agar or agarose solutions above the melting point.

In a comparison between thin alginate layers and extra thin alginate films on carrot shoot protoplast culture, thin alginate layers resulted in nearly a 20% increase in plating efficiency in every accession tested (Maćkowska et al., 2014). Sterilizing the alginate solution through filter-sterilization was also found to give over a 10% increase in plating efficiency over autoclave-sterilization in several of the accessions used.

The amount of liquid medium surrounding alginate beads can affect the protoplast proliferation capability. In American elm (Ulmus americana) cell suspension-derived protoplast alginate bead culture, cultures that contained less than 2 ml or more than 3 ml of liquid medium failed to develop beyond the first cell division; whereas cultures that contained 2 or 3 ml of liquid medium continued to proliferate (Jones et al., 2015).

Temperature and Light

The temperature and light conditions used during protoplast culture vary widely (Table 2) and have both been shown to be of effect in regeneration success. Cabbage leaf protoplast cultures were greatly affected by light and temperature, with very few divisions occurring in cultures moved from dark at 25°C to light at 23°C after 7 days of culture, compared to those kept in the dark conditions for all 15 days (Kaur et al., 2006). Using lettuce (Lactuca saligna) leaf protoplasts, dark culture led to sustained division while light bleached and killed the protoplasts in 3 days (Brown et al., 1987). However, Arabidopsis cotyledon protoplasts did not show a significant variation in either the plating density or growth rates whether cultured in the light or dark (Dovzhenko et al., 2003).

Cell Density

The protoplast plating density can range from single cells up to a few million protoplasts per milliliter, but typically range from 5 × 104–1 × 106 protoplasts/ml (Table 2). In a comparison of plating densities of petunia (Petunia hybrida) leaf protoplast culture, 1 × 106 protoplasts/ml produced a significantly higher division frequency and number of calli than 5 × 104 protoplasts/ml (Kang et al., 2020). However, the microcolony viability decreased with the plating density increasing to 1.5 × 106 protoplasts/ml, potentially due to high phenolics accumulation. Over-crowding the protoplasts can also result in a lower viability due to a lack of available nutrients (Kiełkowska and Adamus, 2012). In contrast, a lower density may also be desired to track an individual protoplast after transformation or fusion (Bhojwani and Dantu, 2013). However, a lower protoplast density can be more costly and time consuming. Additionally, protoplasts can release growth factors which can stimulate mitotic division non-cell-autonomously. This is also the basis for nurse cultures.

Nurse Cultures

Nurse cultures are the culture of target protoplasts with additional actively dividing protoplasts or suspension cells, either from the same species (e.g. in crocus (Crocus cancellatus) embryogenic calli-derived protoplast culture (Karamian and Ebrahimzadeh, 2001)) or from another, often closely related species (e.g. in desert banana (Musa paradisiacal) embryonic cell suspension protoplast culture (Dai et al., 2010) and cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis) hypocotyl protoplast culture (Sheng et al., 2011)). There are many nurse culture techniques, one example is feeder layer-cultures, which can be embedding the target protoplasts in agar layers with the nurse cells in a liquid surrounding the layers (Sheng et al., 2011), or the target protoplasts in liquid culture with the nurse cells embedded in agarose (Dai et al., 2010). Alginate bead cultures, which can be performed by embedding the target protoplasts in alginate beads and having the nurse cells in liquid medium (e.g. with rice (Oryza sativa) suspension culture protoplasts (Kyozuka et al., 1987)). An alternate method for ensuring a separation of the nurse cells and the target protoplasts is using a nitrocellulose filter which allows growth factors, signaling molecules, and nutrients to pass through, but not cells (Dai et al., 2010).

Plant Regeneration From Protoplast Culture

Callus Formation

From microcalli, regeneration could come from organogenesis or embryogenesis. Organogenesis-oriented microcalli can be moved to a callus proliferation medium to increase the callus size, whereas embryogenesis-oriented microcalli can be moved to embryo formation medium; however, either could also proliferate callus or form embryos on the microcallus medium, depending on the genotype, source tissue, and medium composition.

Organogenesis typically relies on moving callus to a medium containing both a cytokinin and auxin or a shooting medium followed by a rooting medium. When it comes to the timeframe for regeneration, it is difficult to directly compare organogenesis and embryogenesis between different species and source tissues (Table 3). Intuitively, embryogenesis should take less time than organogenesis due to the extended time the callus needs to shoot and then root versus an embryo’s ability to grow and differentiate both organs at the same time.

TABLE 3.

Regeneration from Protoplast Culture.

| Species | Callus Proliferation/Embryo Formation Medium | Callus/Embryo PGRs | Time to Calli/Embryo | Regeneration Medium | Regeneration PGRs | Time to Regeneration | Regeneration Process | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Elm (Ulmus americana) | Microcalli not transferred | N/A | Not disclosed | Shoots: solid ESM medium (DKW medium (Driver and Kuniyuki, 1984), 3% sucrose, 0.3 μM GA3, 0.22% Phytagel); Roots: solid RM medium (DKW medium (Driver and Kuniyuki, 1984), 3% sucrose, 0.6% activated charcoal, 0.22% Phytagel) | Shoots: 2.2 μM BAP; Roots: 0.5 μM IBA | 4–6 weeks from calli to shoots; 1,2 months from shoots to roots | Organogenesis | Jones et al. (2015) |

| Amur cork tree (Phellodendron amurense) | Microcalli not transferred | N/A | 4 months to calli | Solid MS medium (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 0.2% Gellan gum) | Shoots: 2 μM BAP and 1 μM NAA or 2.5 μM IBA; Roots: 2 μM IBA | 5 weeks from callus to shoots; 1 week from shoots to roots | Organogenesis | Azad (2012) |

| Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) | Callus induction medium (B5 medium, 2% sucrose) | 2.3 μM 2,4-D, 8.9 μM BAP | 2,3 weeks from microcalli to calli | Shoots: Shoot induction medium (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 2.41 mM MES, 0.8% plant agar); Roots: rooting medium (1/2 MS medium containing vitamin, 1% sucrose, 2.41 mM MES, 0.8% plant agar) | Shoots: 0.9 μM IAA, 2.5 μM 2iP; Roots: 5 μM IBA | 0–3 weeks from transfering calli to shoots; 2 weeks from shoots to roots | Organogenesis | Jeong et al. (2021) |

| Banana (Musa paradisiacal) | Solid M6 (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 0.2% gelrite) | 2.3 μM IAA, 2.2 μM BAP | 3 months to germinated embryos | Solid rooting media (MS medium, 0.1% activated charcoal, 3% sucrose, 0.7% agar) | None | 1 month from germinated embryo to plantlet | Embryogenesis | Dai et al. (2010) |

| Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) | Solid MS medium (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 8% myo-inositol, 0.4% Gelrite) | 9.05 μM 2,4-D, 2.2 μM BAP | Not disclosed | Shoots: MS medium; Roots: half-strength MS medium | Shoots: 2.7 μM NAA, 8.9 μM BAP and ; Roots: none | 3 weeks from calli to shoots | Organogenesis | Jie et al. (2011) |

| Microcalli not transferred | N/A | Not disclosed | MS medium (0.1 μM PSK-α) | None | 4-6 weeks from calli to shoots | Organogenesis | Kiełkowska and Adamus (2019) | |

| Microcalli not transferred | N/A | 4-6 weeks from microcalli to calli | Shoots: Solid MS2 medium (MS medium, 2% sucrose, 0.25% Gelrite); Roots: MS medium | Shoots: 2.7 μM NAA, 8.8 μM BAP; Roots: none | Not disclosed | Organogenesis | Kiełkowska and Adamus (2021) | |

| Microcalli not transferred | N/A | Not disclosed | Solid MS medium (MS medium, 2% sucrose, 0.25% Phytagel) | None | 4 weeks from calli to shoots | Organogenesis | Kiełkowska and Adamus (2012) | |

| Canola (Brassica napus) | Microcalli proliferation medium (MS medium, 3.5% sucrose, 2.56 mM MES, 0.7% agarose) | 5 μM NAA, 5 μM 2,4-D, 5 μM BAP | 1 week from microcalli to calli | Shoots: shoot regeneration medium (SRM) (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 2.56 mM MES, 0.05% PVP, 29.4 μM silver nitrate, 0.3 μM GA3, 0.7% agarose); shoot elongation medium (SEM) (MS medium, B5 vitamins, 2% sucrose, 2.56 mM MES, 0.1 μM GA3, 0.8% agar); Roots: root induction media (RIM) (1⁄2 strength MS, B5 vitamins, 1% sucrose, 2.56 mM MES, 0.6% agar) | SRM: 0.5 μM NAA, 2.5 μM 2iP; SEM: 2 μM BAP; RIM: 2.5 μM IBA | 4-6 weeks from calli to shoots; 4 weeks for shoot elongation; 3-7 days from elongated shoots to roots | Organogenesis | Sahab et al. (2019) |

| Carrot (Daucus spp.) | Microcalli not transferred | N/A | 2 months to calli and embryos | Solid R medium (MS medium, 2% sucrose, 0.3 mM thiamine, 0.49 μM pyridoxine, 4.06 μM nicotinic acid, 40 μM glycine, 0.56 mM myo-inozytol, 0.25% phytagel) | None | 2,3 weeks from calli/embryos to plantlets | Undetermined | Grzebelus and Skop (2014) |

| Microcalli not transferred | N/A | Not disclosed | None | Somatic embryos; 1 month from calli to plants; 2-3 months total to plantlet | Embryogenesis | Grzebelus et al. (2012) | ||

| Microcalli not transferred | N/A | 2 months to calli and embryos | None | 5 weeks from calli or embryo to plantlet | Undetermined | Maćkowska et al. (2014) | ||

| Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis) | Microcalli not transferred | N/A | 5–7 weeks to calli | Solid regeneration medium (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 0.8% plant agar) | 4.6 μM zeatin and 1.15 μM IAA | 10 weeks to shoots | Organogenesis | Sheng et al. (2011) |

| Chicory and Endive (Cichorium intybus and endivia) | Microcalli not transferred | N/A | Not disclosed | Solid MC3 medium (1/2 MS macro elements, Heller micro elements, Morel & Wetmore vitamins, 1% sucrose, .55 mM inositol, 0.05 mM FeNa-EDTA, 0.5% agar) | 2.85 μM IAA, 2.2 μM BAP | 14 weeks total to plantlet | Organogenesis | Deryckere et al. (2012) |

| Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium) | Soild proliferation medium (1⁄2 MS medium, 2% sucrose, 0.25% gelrite) | 10.75 μM NAA, 4.45 μM BAP | Not disclosed | Shoot induction medium (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 0.3% gelrite) | Shoots: 2.7 μM NAA, 4.45 μM BAP; Roots: 9.05 μM 2,4-D, 13.3 μM BAP | 16 weeks from calli to plantlet | Organogenesis | Adedeji et al. (2020) |

| Semi-solid proliferation media (1/2 MS salts, KM vitamins, 1% sucrose, 26.6 μM glycine, 0.4% Phytagel) | 0.11 μM NAA, 2.2 μM BAP | 2 weeks from microcalli to calli | Regeneration media (MS medium, KM vitamins, 2% sucrose, 26.6 μM glycine, 0.6% MC29 agar) | 0.45 μM TDZ | Not disclosed | Organogenesis | Eeckhaut et al. (2020) | |

| Coriander (Coriandrum sativum vars.) | Microcalli not transferred | N/A | 3,4 weeks to calli; 4 weeks from calli to embryos | MS medium (1.44 μM GA3) | 4.45 μM BAP | 4,5 months to outdoor plant | Embryogenesis | Ali et al. (2018) |

| Cottonwood (Populus beijingensis) | Callus proliferation media (MS medium (without NH4NO3), 3% sucrose, 0.6% agar) | 4.52 μM 2,4-D, 0.89 μM BAP | Not disclosed | Shoots: MS medium; Roots: rooting medium (1/2 MS medium, 3% sucrose, 0.6% agar) | Shoots: 2.22 μM BA, 0.54 μM NAA; Roots: 2.46 μM IBA | 4 weeks from calli to shoots; 12 weeks totals to shoots | Organogenesis | Cai and Kang (2014) |

| Crown imperial (Fritillaria imperialis L.) | Microcalli not transferred | N/A | Not disclosed | Solid MS medium | 2.7 μM NAA, 6.66 μM BAP | Not disclosed | Organogenesis | Chamani and Tahami (2016) |

| Florist Kalanchoe (Kalanchoe blossfeldiana) | Colonies cultured in liquid BMb for 15 days, then added liquid BMc (MS medium, SH vitamins (Shahin, 1985), 3.8% mannitol, 3% sucrose, 0.6 mM myo-inositol) for calli proliferation, then small calli moved to solid BMc (0.8% agar) | 5.4 uM NAA and 8.9 uM BAP | Not disclosed | Solid BMa (MS medium, ST vitamins (Staba, 1969), 3% sucrose, 0.6 mM myo-inositol, 3 μM thiamine, 0.8% agar) | 0.6 μM IAA | 5 months total to plantlet | Organogenesis | Castelblanque et al. (2010) |

| Gentian (Gentiana decumbens) | Agar-solidified CPM3 (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 0.217 mM adenine sulfate), then non-embryo calli moved to agar-solidified PRM3 (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 2% coconut water, 1.44 μM GA3, 0.217 mM adenine sulfate) for embryo formation | CPM3: 0.54 μM NAA, 8.9 μM BAP, 4.53 μM dicamba; PRM3: 4.65 μM kinetin | Somatic embryos 6 weeks on CPM3 or 12 weeks on CPM3/PRM3 | Agar-solidified half-strength MS medium (1/2 MS medium, 1.5% sucrose) | None | Not disclosed | Embryogenesis | Tomiczak et al. (2015) |

| Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe.) | Solid MS medium (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 0.7% agar) | 0.9 μM 2,4-D, 22.2 μM BAP | 6 months to embryos | MS medium | Shoots: none; Roots: 3.22 μM NAA, 8.9 μM BAP | 15 months total to plantlet | Embryogenesis | Guan et al. (2010) |

| Microcalli not transferred | N/A | 40–60 days to calli | Solid MS medium (MS medium, 4% mannitol, 3% sucrose) | 5.4 μM NAA, 4.45 μM BAP | Not disclosed | Organogenesis | Nirmal Babu et al. (2016) | |

| Grape hyacinth (Muscari neglectum) | Solid half-strength MS agar medium | Callus proliferation: 0.45 μM BAP; Embryo formation: none | Not disclosed | half strength MS medium | 4.45 μM BAP | 3 months from embryo to plantlet | Embryogenesis | Karamian and Ranjbar (2011) |

| Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) | Embryo germination medium (Nitsch’s medium, 3% sucrose, 0.2% gellan gum) | None | 3-4 months to embryos; 4 weeks for embyo germination | Shoots: C2D4B medium (C2D medium, 3% sucrose, 0.7% TC agar); Roots: MS medium (3% sucrose, 0.7% TC agar) | Shoots: 4 μM BAP; Roots: 0.5 μM NAA | 3-4 weeks from germinated embryo to shoots; 6 month total to outdoor plants | Embryogenesis | Bertini et al. (2019) |

| Guava (Psidium guajava) | Solidified culture media (8% agar) | 5.4 μM NAA | Not disclosed | Shoots: shoot regeneration medium; Roots: MS medium (medium specifics not disclosed) | Shoots: 11.15 μM kinetin, 7.1 μM BAP; Roots: 0.5 μM IBA | 8 weeks from microcalli to shoots; 4 weeks from shoots to roots | Organogenesis | Rezazadeh and Niedz (2015) |

| Hydrangea (Hydrangea spp.) | Solid PPM3 medium (MS medium, MW vitamins, 0.5% PVP 10, 3.48 mM MES, 3% sucrose, 5% mannitol, 0.6 mM Timentin, 1.4 μM ascorbic acid, 0.13 mM citric acid, 67 nM Karrikinolide, 0.25% Phytagel) | 10.75 μM NAA with 8.9 μM BAP | 8 weeks from microcalli to calli | Solid SRM medium (B5 salts and vitamins, 2.18% sucrose, 0.615 mM myo-inositol, 0.6 mM Timentin, 0.142 mM ascorbic acid, 0.13 mM citric acid, 0.068% Gelrite, 0.3% bactoagar) | 0.54 μM NAA, 8.9 μM BAP | 15 months total to plantlet | Organogenesis | Kästner et al. (2017) |

| Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) | Microcalli not transferred | N/A | Not disclosed | Shoots: Regeneration medium (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 0.6% plant agar); Roots: 1/2 MS medium | Shoots: 0.54 μM NAA, 2.2 μM BAP; Roots: none | 4 weeks from microcalli to shoots | Organogenesis | Woo et al. (2015) |

| Microcalli not transferred | N/A | Not disclosed | Shoot induction medium (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 0.6% agar); Roots: MS medium | Shoots: 0.54 μM NAA, 2.2 μM BAP; Roots: none | 4 weeks from calli to shoots | Organogenesis | Park et al. (2019) | |

| Lily (Lilium ledebourii) | Microcalli not transferred | N/A | Not disclosed | semi-solidified MS medium | 0.54 μM NAA, 6.66 μM BA | Not disclosed | Organogenesis | Tahami et al. (2014) |

| Love-in-a-Mist (Nigella damascena L.) | Embryo formation media (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 0.7% agar) | 5.4 μM NAA, 9.3 μM kinetin | 3 months to calli; 3 weeks from calli to embryo | Regeneration media (MS medium, 13.4 μM glycine, 2% sucrose, 0.2% phytagel) | None | 2 months from embryo to plantlet | Embryogenesis | Klimek-Chodacka et al. (2020) |

| Oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) | Solid Y3 medium (1.14 mM ascorbic acid) | 1 μM NAA, 0.1 μM BAP | 4-12 weeks to calli; 20-24 weeks from calli to embryos | ECI solid medium (media specifics not disclosed) | 1 μM NAA and 0.1 μM BAP | 12 weeks from embryo to plantlet; 56-68 weeks total to plantlet | Embryogenesis | Masani et al. (2013) |

| Petunia (Petunia hybrids) | KM proliferation medium (KM medium, B5 vitamin, 3.0% sucrose) | 2.7 μM NAA, 2.2 μM BAP | 4 weeks from microcalli to calli | MS medium (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 0.8% plant agar) | Shoots: 1 μM IBA, 4.45 μM BAP; Roots: none | Not disclosed | Organogenesis | Kang et al. (2020) |

| Callus induction medium (MS medium, 3% sucrose) | 2.7 μM NAA, 8.9 μM BAP | 2,3 weeks from microcalli to calli | Regeneration medium (MS medium, 3% sucrose) | Shoots: 4.6 μM zeatin; Roots: none | 2,3 weeks from calli to shoots | Organogenesis | Yu et al. (2020) | |

| Qin-jiao (Gentiana macrophylla) | Solidified MS medium (MS medium, 3% sucrose, 0.05% casein hydrolysate, 0.85% agar) | Callus proliferation: 9.05 μM 2,4-D, 2.2 μM BAP; Embryo formation: 2.3 μM 2,4-D | 6 weeks from microcalli to proembryos | Solidified MS medium (MS medium, 0.05% casein hydrolysate, 3 % sucrose, and 0.85 % agar) | Germination: 8.9 μM BAP; Rooting: none | 2 weeks from proembryo to germination; 3 weeks from germination to plantlet | Embryogenesis | Hu et al. (2015) |

| Silk tree (Albizia julibrissin) | Solid MSB5 medium (MS medium, B5 vitamins, 3% sucrose, 0.02% casein hydrolysate) | 10.8 μM NAA, 4.4 μM BAP | Not disclosed | Shoots: MS medium; Roots: half-strength MS medium | Shoots: 4.6 μM zeatin, 13.2 μM BAP; Roots: 4.9 μM IBA | 5 weeks from calli to shoots; 4,5 weeks from shoots to roots | Organogenesis | Rahmani et al. (2016) |