Abstract

Background

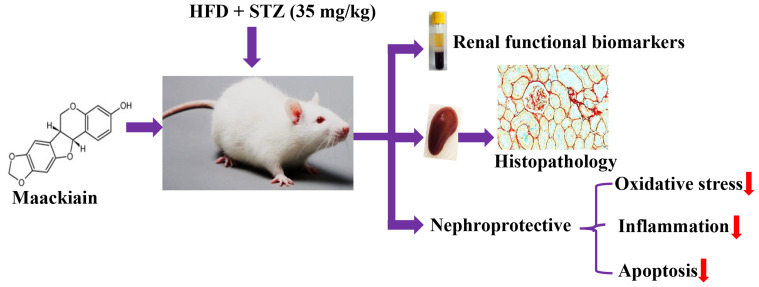

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is aglobal health burden that accounts for about 90% of all cases of diabetes. Injury to the kidneys is aserious complication of type 2 diabetes. Maackiain, apterocarpan extracted from roots of Sophora flavescens, has been traditionally used for various disease conditions. However, nothing is known about its possible potential effect on HFD/STZ-T2D-induced nephrotoxicity.

Methods

In this study, T2D rat model is created by high-fat diet (HFD) for 2 weeks with injection of asingle dose of streptozotocin (35mg/kg body weight). T2D rats were orally administered with maackiain (10 and 20mg/kg body weight) for 7 weeks.

Results

Maackiain suppressed T2D-induced alterations in metabolic parameters, lipid profile and kidney functionality markers. By administering 10 and 20mg/kg maackiain to T2D rats, it was able to reduce lipid peroxidation while improving antioxidant levels (SOD, CAT, and GSH). Furthermore, the present study demonstrated the molecular mechanisms through which maackiain attenuated T2D-induced oxidative stress (mRNA: Nrf2, Nqo-1, Ho-1, Gclc and Gpx-1; protein: NRF2, NQO-1, HO-1 and NOX-4), inflammation (mRNA: Tlr, Myd88, IκBα, Mcp-1, Tgf-β, col4, Icam1, Vcam1 and E-selectin; Protein: TLR4, MYD88, NF-κB, IκBα, MCP-1; levels: TNF-α and MCP-1) and apoptosis (mRNA: Bcl-2, Bax, Bad, Apaf-1, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3; protein: Bcl-2, Bax, Caspase-3 and Caspase-9) mediated renal injury. Additionally, significant improvement in kidney architecture was observed after treatment of diabetic rats with 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain.

Conclusion

Maackiain protects the kidney by decreasing oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis to preserve normal renal function in type 2 diabetes.

Keywords: high-fat diet, streptozotocin, oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, kidney

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Diabetes is aserious public health threat that respects no socioeconomic status globally in developed and developing countries.1 Diabetes is ametabolic disorder that occurs when the pancreas is unable to produce insulin or the body is unable to use insulin efficiently. According to the most recent assessments of the Global Diabetes Organization, 463million adults now have diabetes, with this number expected to rise to 578million by 2030 and 700million by 2045.2 Type 2 diabetes is amore common condition in adults where the body cannot effectively use insulin to make glucose into energy. It accounts for around 90% of all diabetes cases and is linked to multiple comorbidities and complications. Hyperglycemia affects the heart, blood vessels, eyes, nerves and teeth, including kidneys. Microvascular alterations in the kidneys caused by various mechanisms often result in diabetic kidney disease, also known as diabetic nephropathy.3,4

Among various pathophysiological processes involved in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy, oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis have been considered significant contributors.5 Earlier evidence pointed out the contributory roles of elevated levels of reactive oxygen species and suppressed antioxidant defenses in the development of diabetic kidney disease.6,7 Recent reports also highlighted the role of Nrf2/Keap1/ARE pathway at the transcriptional level to regulate cellular oxidative and anti-oxidative status.8 Furthermore, nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) knockout in streptozotocin-induced mice showed high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) with greater oxidative DNA damage and renal injury.9 Studies also reported the involvement of diabetes-mediated oxidative stress in instigating the inflammatory pathways for the progression of kidney damage.5,10 Inflammation has been recognized as an underlying mechanism that plays acritical role in the progression and pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease.11 It is also noteworthy to mention the involvement of TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway and its effector mediators such as proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, pro-fibrotic factors and adhesion molecules inactivation of inflammation.12,13 However, oxidative stress and inflammation work in coordination to activate amitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway, which further damages the diabetic kidney and ultimately results in renal failure.5 So agents which counteract oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis might prevent diabetes-mediated renal damage.

Although there are many treatment modalities, including western medications, available to treat and manage type 2 diabetes-mediated complications and kidney damage, management with lesser side effects at affordable cost is still abig challenge for researchers. Nowadays, much emphasis has been given to herbal medication due to its relatively safe nature, less side effects and availability at low cost.14,15 Sophora flavescens is one such well-known Chinese herbal medicine. It has also history in traditional medicines of Japan, Korea, India, and some countries of Europe that are prescribed for various ailments such as skin burns, asthma, and jaundice dysentery, ulcers, fever and inflammatory disorders.16 Maackiain, apterocarpan isolated from the roots of S.flavescens, has abroad spectrum of biological activities including anti-cancer,17 anti-allergic,18 and inhibitory activity on monoamine oxidaseB19 and anti-inflammatory properties.20

Taking into consideration the diabetes-induced kidney problems as well as the safety properties of maackiain, the current study was designed to investigate the possible protective effect of maackiain on type 2 diabetes-induced renal dysfunctions and to characterize the anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic mechanisms through which it protects renal injury using arat as an exploratory model.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Maackiain (MN) (<98%) was procured from Ruicong Ltd (Shanghai, China) and streptozotocin (STZ; <98%) was procured from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., (St.Louis, MO, USA). All of the other chemicals and reagents used in this research were obtained locally.

Animals

Adult male healthy Swiss Albino mice and Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats with body weights ranging from 25 ± 03 gand 200 ± 20 g, respectively, were obtained from the Institute of Experimental Animals, Qingdao No.9 People’s Hospital, China. Initially, after procurement, animals were shifted to aquarantine room to check the health status of animals by the veterinarian. After one week of acclimation to experimental room conditions, healthy animals were subjected to experiments. Animals were maintained in standard experimental room conditions (22 ± 3°C temperature, 50 ± 10% humidity, 12 hours lighting) and had to access to ad libitum irradiated standard rodent diet and autoclaved water before dietary manipulation. All animal experiments were approved and carried out in compliance with Institutional Animal Care Guidelines (approval no.202009673590; Experimental Animal Ethics Committee, Qingdao No.9 People’s Hospital, Shandong, China).

Induction of Type 2 Diabetes in Experimental Animals

Type 2 diabetes was induced in rats as described previously by Srinivasan etal21 and Mahmoud etal.22 Induction of type 2 diabetes in rats using ahigh fat diet [29.5% tallow of beef; 22% casein; 23% starch; 17.9% cellulose; 4% lcysteine; 0.3% choline chloride; 1.8% vitamin mixture; 1.5% salt mixture (AIN-93 ViX))] for 2 weeks and asingle low dose of STZ, 35mg/kg body weight dissolved in freshly prepared 0.1 M cold citrate buffer (pH 4.5) through intraperitoneal route administered intraperitoneally. After aweek of STZ injection, rats with fasting blood glucose levels more than 12.5 mmol/L were classified as type 2 diabetic and used in the study. However, control rats received anormal diet (56% starch; 18.5% protein; 8% fat; 12% fibre) and afreshly prepared 0.1 Mcold citrate buffer (pH 4.5) through intraperitoneal route.

Acute Oral Toxicity Study

The acute toxicity of maackiain was investigated using OECD [1998] Guideline 425 in Swiss Albino male mice after oral administration up to amaximum dosage of 2000mg/kg. The animals were constantly monitored for two hours to assess their behavioral, neurological, and autonomic features.23

Experimental Design

The rats were divided randomly into four groups of ten individuals each:

Group 1: Normal control rats received 1% sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (Na-CMC) vehicle

Group 2: Type 2 diabetic rats received 1% Na-CMC vehicle

Group 3: Type 2 diabetic rats received 10mg/kg/bw of maackiain

Group 4: Type 2 diabetic rats received 20mg/kg/bw of maackiain

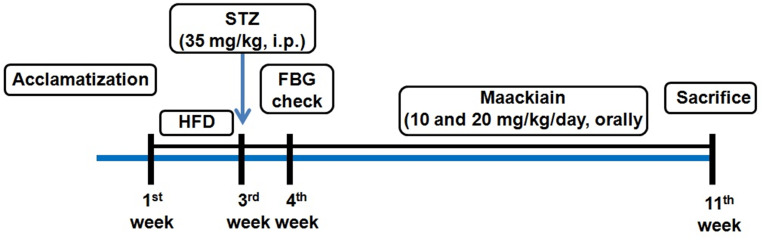

Doses of maackiain were selected based on earlier study.24 Meanwhile, groups 2 to 4 proceed with HFD for 7 weeks of treatment. Maackiain was maackiain suspended in 1% Na-CMC and administered orally with an oral gavage tube everyday for 7 weeks. The details are presented in Figure1.

Figure1.

Schematic representation of experimental design of the study.

Abbreviations: HFD, high-fat diet; STZ, streptozotocin; HFD, high-fat diet; FBG, fasting blood glucose.

Assessment of Bodyweights, Feed and Water Intake and FBG Levels

Daily feed and water consumption and weekly body weight and fasting blood glucose levels were observed throughout the study period. On the lastday of the experiment, urine was collected in metabolic cages and animals were anesthetized (xylazine-12.5mg/kg/bw and ketamine −87.5mg/kg/bw, i.p), blood was collected via cardiac puncture and centrifuged at 2000g for 15 minutes to separate serum for biochemical analysis, and animals were sacrificed via cervical dislocation.

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, insulin serum concentrations were determined using arat enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) test kit (Elabscience Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Wuhan, China). Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and the serum concentrations of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) were measured by using the automatic Beckman Coulter analyzer. Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) and HOMA β-cell function was calculated using the formula.25

Kidneys were taken immediately after necropsy and fixed in 10% neutral formalin buffer for histological examinations and biochemical and molecular studies stored at −80°C till further use.

Determination of Renal Functional Biomarkers

Renal functional assessment biomarkers such as serum creatinine (µmol/L), albumin (g/dL), urea (mg/dL) and uric acid (µmol/L) were evaluated using commercially available colorimetric assay kits (Elabscience Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Wuhan, China). BUN is calculated by using the following formulae:

|

Further, Urinary protein concentrations (mg/day) were evaluated by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay method using BSA as standard (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Determination of Oxidative and Antioxidative Status in Kidneys

The levels of lipid peroxidation products (MDA) and antioxidant defenses such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione (GSH) were measured in 10% kidney tissue homogenate supernatant samples using commercially available kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). The Bradford protein assay kit assessed total protein concentrations (Sigma-Aldrich, St.Louis, MO, USA).

Reverse Transcription Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR) Analysis

Following the animals’ euthanasia, the extracted kidneys were stored in RNA later solution to preserve the RNA’s integrity. Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol® Reagent, quantified with ananodrop, and Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using aHigh-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems, Ca, USA). PCR was carried out using SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and was performed in StepOnePlus Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Table1 contains the primer sets used in RT-qPCR. After normalization to the housekeeping gene, ie, β-actin, the relative expression of each gene was measured. Three duplicates of each reaction were maintained to ensure the reproducibility of the findings.26

Table1.

PCR Primers Used in This Paper

| Nrf2 | F: 5′CCTATGCGTGAATCCCAAT3′ |

| R: 5′TGTGAGATGAGCCTCTAAGCG3′ | |

| Keap1 | F: 5′ATGTTGACACGGAGGATTGG3′ |

| R: 5′TCATCCGCCACTCATTCCT3′ | |

| Nqo-1 | F: 5′GCGAGAAGAGCCCTGATTGT3′ |

| R: 5CTTCAGCTCACCTGTGATGTCAT3′ | |

| Ho-1 | F: 5′CAAGCCGAGAATGCTGAGTT3′ |

| R: 5′CAGGGCCGTGTAGATATGGTA3′ | |

| Gclc | F: 5′ TCGCCTCCGATTGAAGATG3′ |

| R: 5′ TACTATTGGGTTTTACCTGTGCC3′ | |

| Gpx1 | F: 5′ CAGTTCGGACATCAGGAGAAT3′ |

| R: 5′ AGAGCGGGTGAGCCTTCT3′ | |

| Tlr4 | F: 5′ GTGGAAGTTGAACGAATGGA3′ |

| R: 5′ TGGATGATGTTGGCAGCA3′ | |

| Myd88 | F: 5′ TCGCGCATCGGACAAACG3′ |

| R: 5′ GCAATGGACCAGACACAGGT3′ | |

| Col4 | F: 5′ TACTGGCAGAGCCCTTGAGCC3′ |

| R: 5′ CATTCTTTCTGGATTTAGTGAAGC3′ | |

| Tgf-β | F: 5′ GACCTCAATTGCGAGCTTTC3′ |

| R: 5′ AGTCCTCCTTCCGCCTTTAG3′ | |

| Mcp-1 | F: 5′TCTCTTCCTCCACCACTATGCA3′ |

| R: 5′GGCTGAGACAGCACGTGGAT3′ | |

| Vcam-1 | F: 5′TGACAAGTCCCCATCGTTGA-3′ |

| R: 5′ACCTCGCGACGGCATAATT3′ | |

| Icam-1: | F: 5′CCTGTTTCCTGCCTCTGAA3′ |

| R: 5′GTCTGCTGAGACCCCTCTTG3′ | |

| E-selectin: | F: 5′TGAACTGAAGGGATCAAGAAGACT3′ |

| R: 5′GCCGAGGGACATCATCACAT3′ | |

| Bcl2 | F: 5′ CCTGAGAGCAACCGAACG3′ |

| R: 5′ CCTGAGAGCAACCGAACG3′ | |

| Bax | F: 5′ CACCAGCTCTGAACAGATC3′ |

| R: 5′ CTTCTTCCAGATGGTGAGC3′ | |

| Bad | F: 5′ CCCCCCAATCTCTGGGCAGCG3′ |

| R: 5′ TCACTGGGAGGGGGTGGAGCC3′ | |

| Apaf-1 | F: 5′ GTAGACGGCTTTCTCCGCTC3′ |

| R: 5′ CGGATCCAGGACACAAAAGC3′ | |

| Caspase-9 | F: 5′ ATGCAGGTCCCTGTCATG3′ |

| R: 5′ GCTTGAGGTGGTTGTGGA3′ | |

| Caspase-3 | F: 5′ GAGCTTGGAACGCGAAGAAA3′ |

| R: 5′ CCATTGCGAGCTGACATTCC3′ | |

| β-actin | F: 5′GTGCTATGTTGCTCTAGACTTCG3′ |

| R: 5′ATGCCACAGGATTCCATACC3′ |

Determination of Levels of TNF-α and MCP-1 Levels and NF-κB p65 DNA Binding Activity

Using ELISA kits, cytokines (tumor necrosis factor; TNF-α and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MCP-1) levels were quantified in kidney homogenates according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Elabscience Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Wuhan, China). According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB was determined using the TransAM® NF-B p65 transcription factor assay kit (Cat. No.40596, Active Motif, Tokyo, Japan). The optical density of protein-bound NF-κB was measured at 450 nm. The TransAM format is perfect for assaying transcription factor binding to aconsensus-binding site.

Histopathological Analysis

Left kidneys from both control and treatment groups were immediately fixed in 10% neutral formalin buffer until further investigation. On theday of processing, tissues were appropriately trimmed, subjected to aseries of alcohol washes, embedded in paraffin, microtomed into 5m thick sections, and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Picro-Sirius Red (PSR) (ab246832) stains, and atrichrome stain kit (ab150686) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). An Olympus phase contrast microscope was used to examine and capture the pictures.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed using the method described by Giribabu etal.27 Kidney sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and antigen-retrieved using a10 mM sodium citrate buffer solution (pH 6.0) for immunohistochemical investigations. Endogenous peroxidase activity was suppressed with 0.3% Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) prior to sections being incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies such as Anti-Nrf2 (ab62352), anti-NOX-4 (ab109225), anti-Keap-1 (ab218815), anti-NF-κB (ab16502), anti-MCP-1 (ab25124), anti-BCL-2 (ab194583) and anti-BAX (ab32503), anti-Caspase-9 (ab184786) (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) diluted in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). After incubation, slides were rinsed three times in PBS, incubated for 1hour with the appropriate secondary antibody for 60 min, stained with 3ʹ-Diaminobenzidine (DAB), and counterstained with hematoxylin. The images were examined and captured using an Olympus phase-contrast microscope.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed in accordance with the method described by Khalil etal.28 On the kidney sections, immunofluorescence staining was performed after deparaffinization, rehydration, antigen retrieval with 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0), and blocking with 5% BSA. Following blocking, sections were incubated (anti-NQO-1: ab80588; anti-HO-1: ab189491; anti-TLR4: ab217274; anti-MYD88: ab219413; anti-IKB alpha: ab32518; and anti-Caspase-3: ab184787) overnight at 4oC with 1:1000 dilutions of primary antibodies in the serum. Following PBS washes, kidney sections were incubated with asecondary antibody conjugated with DyLight 488/594 (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at room temperature in the dark. The slices were mounted using UltraCruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) media containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for nuclear staining and sealed with acoverslip. Finally, images were viewed and captured using fluorescence microscopy (Leica DM IRB, Germany).

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 22 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The data were expressed as mean standard deviation (S.D). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine the significance of differences between groups. Aprobability value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effects of Maackiain on Acute Oral Toxicity Test

Maackiain was found to be safe following oral administration up to 2000mg/kg. No mice mortality was observed within 24 hours of the observational study.

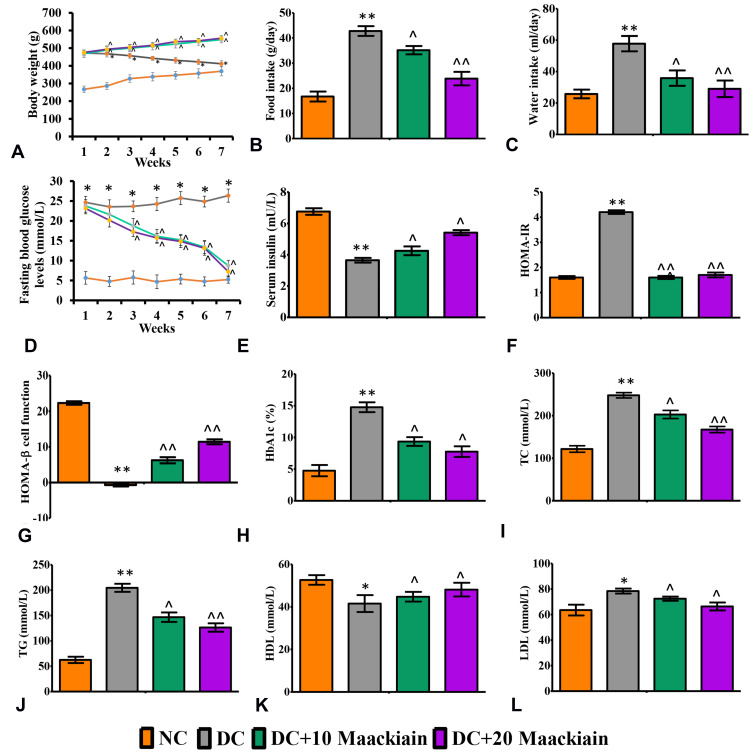

Effects of Maackiain on Body Weights, Feed and Water Intake of HFD/STZ-Induced Type 2 Diabetic Rats

The changes in weekly body weights and feed and water consumption of control and experimental rats are shown in Figure2A–C. When HFD-fed rats were compared to normal diet-fed rats, their body weights increased significantly (p<0.001), while body weights dropped dramatically after STZ injection. As diabetic rats were given 10 (p<0.05) or 20 (p<0.05)mg/kg bw maackiain, their body weights increased substantially when compared to non-diabetic rats. Diabetic rats consumed significantly more feed (p<0.001) and water (p<0.001) than control rats, while treatment with maackiain 10 (p<0.05) or 20 (p<0.001)mg/kg bw dramatically decreased diabetic rats’ feed and water intake.

Figure2.

The effects of maackiain metabolic parameters in HFD & low STZ induced diabetic rats. (A) Weekly body weights; (B) Food intake; (C) Water intake; (D) Fasting blood glucose levels (FBG); (E) serum insulin; (F) HOMA-IR; (G) HOMA-β cell function; (H) Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c); (I) Total cholesterol (TC); (J) Triglycerides (TG); (K) High density lipoproteins (HDL); (L) Low density lipoproteins (LDL). The data were expressed as the mean ± S.D, n=6, **p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05 versus NC; ^^p<0.001 and ^p< 0.05 versus DC.

Abbreviations: NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; DC+10 maackiain, 10 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats; DC+20: 20 maackiain, 20 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats.

Effects of Maackiain on Metabolic Parameters in Type 2 Diabetic Rats

Weekly FBG levels in diabetic rats did not decrease significantly when compared to control rats until the end of the experiment, whereas 7 weeks of treatment with 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain resulted in asignificant (p<0.001) decrease in FBG levels to near normal levels when compared to diabetic rats at the same levels (Figure2D). Serum insulin levels in diabetic rats were significantly (p<0.001) lower than in control rats, however, treatment of 10 (p<0.05) or 20 (p<0.05)mg/kg maackiain resulted in asignificant rise in insulin levels when compared to diabetic animals (Figure2E). Diabetic rats also showed adramatic increase in HOMA-IR (p<0.001) (Figure2F) and drastic decline in HOMA-β cell function (p<0.001) (Figure2G) with respect to controls, however, after treating diabetic rats with either 10 (p<0.001) or 20 (p<0.001)mg/kg maackiain showed asignificant drop in HOMA-IR and rise in HOMA-β cell function. The percentage of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) (Figure2H) is within normal limits in controls, abnormally high in diabetic rats (p<0.001), while treatment with either 10 (<p0.05) or 20 (p<0.05)mg/kg maackiain resulted in significant improvement.

Effects of Maackiain on Lipid Markers in Type 2 Diabetic Rats

When diabetic rats were compared to normal control rats, there were significant increases in total cholesterol (p<0.001) (Figure2I), triglycerides (p<0.001) (Figure2J), and LDL (p<0.05) (Figure2L), as well as asignificant decrease in HDL (p<0.05) (Figure2K). Treatment with 10 (p<0.05) or 20 (p<0.001 for TC and TG; p<0.05 for LDL and HDL)mg/kg maackiain for seven weeks significantly reduced the lipid metabolic alterations observed in diabetic rats.

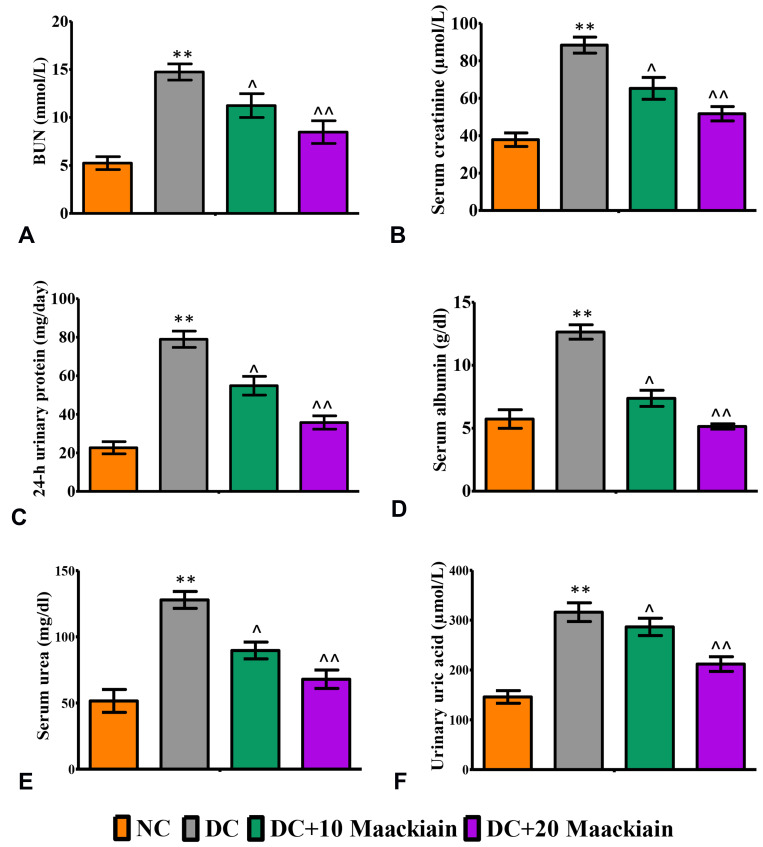

Effects of Maackiain on Kidney Function Biomarkers in Type 2 Diabetic Rats

Diabetic rats exhibited significantly higher levels of renal functioning markers such as BUN (p<0.001) (Figure3A), serum creatinine (p<0.001) (Figure3B), 24 hrs urinary protein (p<0.001) (Figure3C), serum albumin (p<0.001) (Figure3D), serum urea (p<0.001) (Figure3E) and urinary uric acid (p<0.001) (Figure3F) than control rats. Treatment of diabetic rats with 10 (p<0.05) or 20 (p<0.001)mg/kg maackiain significantly improved renal function by significantly decreasing the above-mentioned parameters.

Figure3.

The effects of maackiain serum and urinary renal markers in HFD & low STZ induced diabetic rats. (A) Blood urea nitrogen (BUN); (B) Serum creatinine; (C) 24-hour urine protein; (D) Serum albumin; (E) Serum urea; (F) Urinary uric acid. The data were expressed as the mean ± S.D, n=6, **p < 0.001 versus NC; ^^p<0.001 and ^p< 0.05 versus DC.

Abbreviations: NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; DC+10 maackiain, 10 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats; DC+20: 20 maackiain, 20 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats.

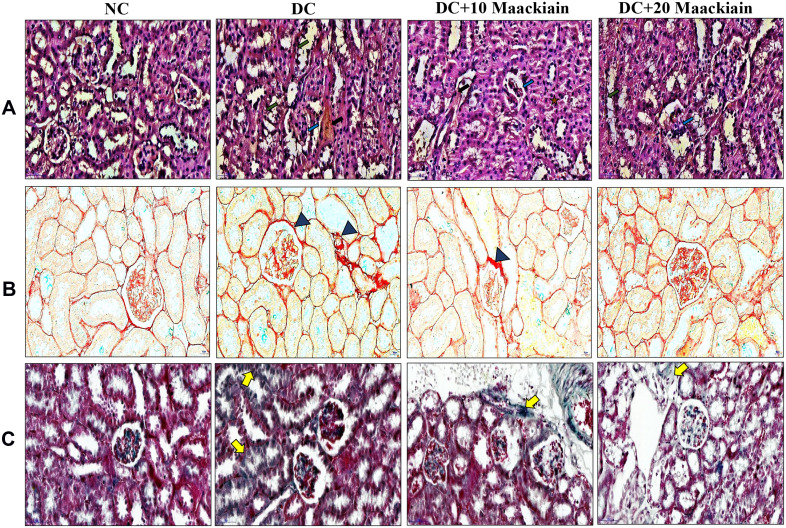

Effect of Maackiain on Histopathology of Kidney

Histopathological analysis of kidney tissue by H&E (Figure4A), PSR (Figure4B), MT (Figure4C) staining depicted in Figure4. Histological sections of the normal kidney displayed normal architecture with glomeruli and tubules in the kidney cortex. Diabetic rat kidney sections presented with thickened glomerular basement membrane, increased glomerular space, degenerated glomeruli, sclerotic glomeruli, tubular degeneration and interstitial fibrosis. However, kidney sections from 10mg/kg maackiain treated diabetic rats revealed moderate improvement through reduced thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, reduction in sclerotic glomeruli and interstitial fibrosis. While, kidney sections from 20mg/kg maackiain treated diabetic rats showed significant improvement, showing glomerular and tubular structures near normal limits.

Figure4.

The effects of maackiain histopathology in HFD & low STZ induced diabetic rats. (A) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining; (B) Picro Sirius Red (PSR) staining; (C) Masson’s Trichrome (MT) staining; H& E(Black color arrow shows necrosis, Green color arrow shows thickened glomerular basement membrane, blue color arrow shows increased glomerular space). PSR and MT (Blue color triangle shows collagen deposition and yellow color arrow also shows collagen deposition). Magnification = x40; Scale bar = 100µm.

Abbreviations: NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; DC+10 maackiain, 10 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats; DC+20: 20 maackiain, 20 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats.

PSR and MT observed collagen deposition in the tissues; the blue and red staining indicated collagen involvement, respectively. Collagen fibers were not seen in the renal interstitial control group, but higher collagen fibers were observed in diabetic groups. However, 10 and 20mg/kg maackiain treated diabetic rats were shown to have reduced collagen deposition.

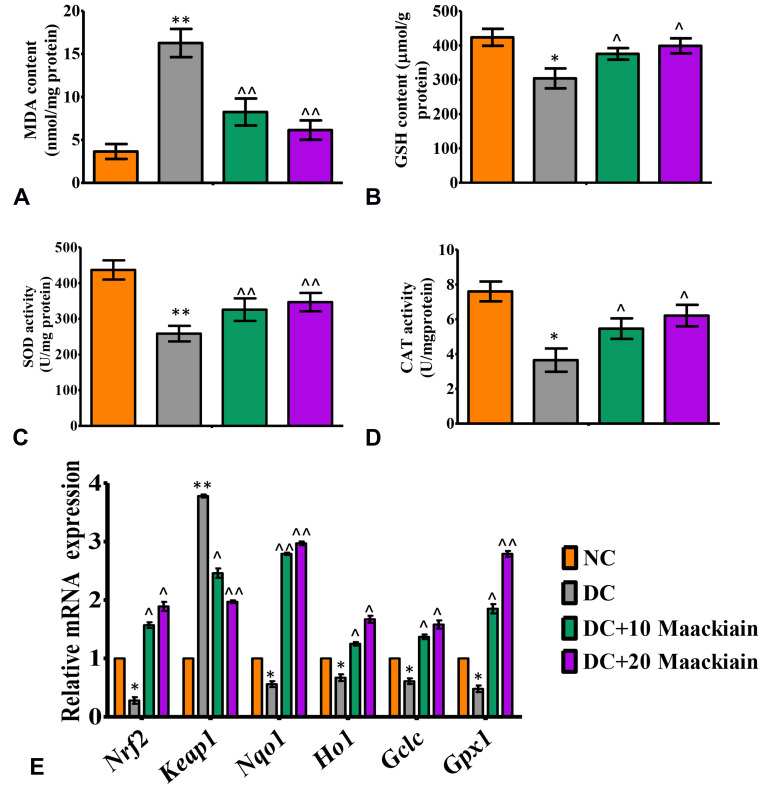

Effect of Maackiain on Oxidative and Antioxidative Status in Type 2 Diabetic Rat’s Kidney

The findings of this research showed dysregulation of oxidative and anti-oxidative state in diabetic rats, as shown by asignificant (p<0.05) rise in MDA (Figure5A) and asignificant reduction in SOD (Figure5C) and CAT (Figure5D) and GSH (Figure5B) levels. On the other hand, diabetic rats treated with either 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain demonstrated significant (p<0.05) improvement in the form of decreased lipid peroxidation products (MDA) and increased antioxidant defense activities such as SOD, CAT and GSH levels.

Figure5.

The effects of maackiain on renal oxidative stress and antioxidant status in HFD & low STZ induced diabetic rats. (A) Lipid peroxidation product malondialdehyde (MDA) levels; (B) Reduced glutathione (GSH) content; (C) Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity levels; (D) Catalase (CAT) activity levels in experimental rats kidney; (E) mRNA levels of Nrf2, Keap1, Nqo1, Ho-1, Gclc, Gpx in experimental rats kidney. The data were expressed as the mean ± S.D, n=6, **p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05 versus NC; ^^p<0.001 and ^p< 0.05 versus DC.

Abbreviations: NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; DC+10 maackiain, 10 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats; DC+20: 20 maackiain, 20 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats.

Figure5E depicts the gene expression of the Nrf-2-Keap-1 signaling pathway from control and experimental rats. The mRNA levels of Nrf2, Nqo1, Ho-1, Gclc and Gpx1 were significantly (p<0.05) reduced in diabetic rats, while Keap1 (p<0.001) was significantly elevated. Besides, diabetic rats treated with 10 or 20 maackiain showed significantly (p<0.05) increased mRNA expression levels of Nrf2, Ho-1, Gclc and Gpx with decreased Keap1 as compared to diabetic rats.

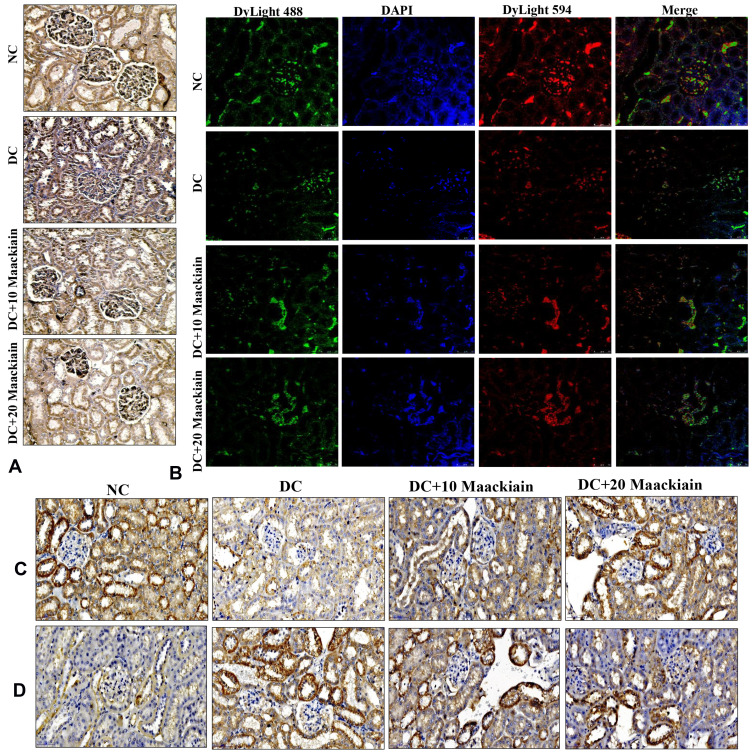

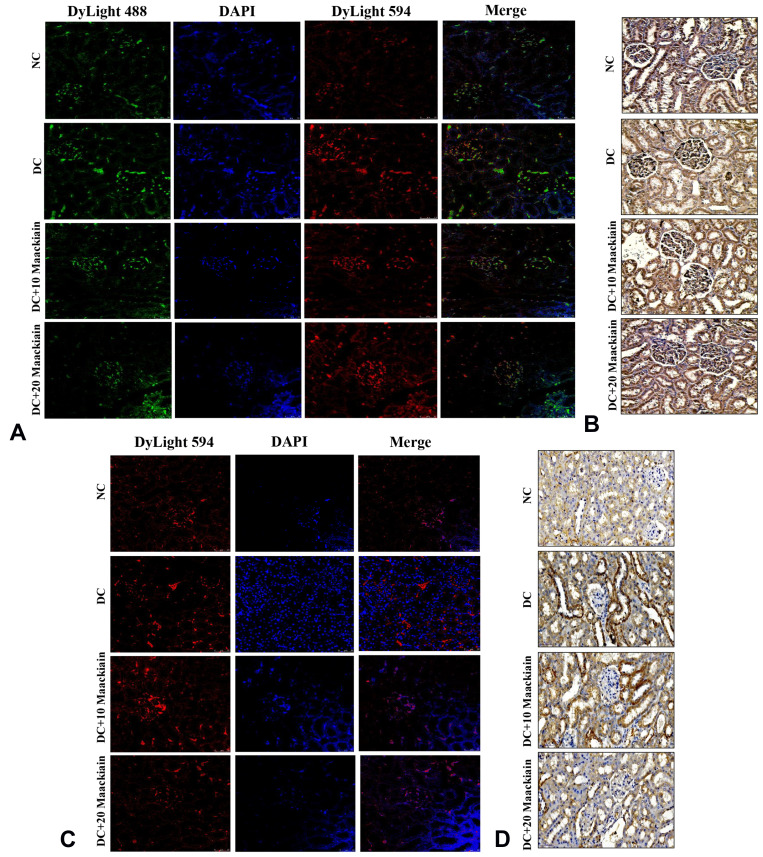

Immunohistochemistry (Nrf2, NOX-4, and Keap1) and immunofluorescence (NQO-1 (red color) and HO-1 (green color) studies confirmed the gene expression data, revealing decreased Nrf2 (Figure6A), NQO-1 (Figure6B), HO-1 (Figure6B), NOX-4 (Figure6C), and with increased Keap-1 (Figure6D) protein distributions in the cortical and glomerular regions. In contrast, diabetic rats receiving either 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain, Nrf2, NQO-1, HO-1, and NOX-4 proteins were increased, while the distribution of Keap-1 protein was decreased.

Figure6.

The effects of maackiain on Nrf2/Keap-1 pathway protein destruction in HFD & low STZ induced diabetic rats. (A) Immunohistochemistry results of Nrf2; (B) Immunofluorescence double staining results of NQO-1 (red color) and HO-1 (green color); (C) Immunohistochemistry results of NOX-4; and (D) Keap-1. Magnification = x40; Scale bar = 100µm.

Abbreviations: NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; DC+10, 10 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats; DC+20, 20 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats.

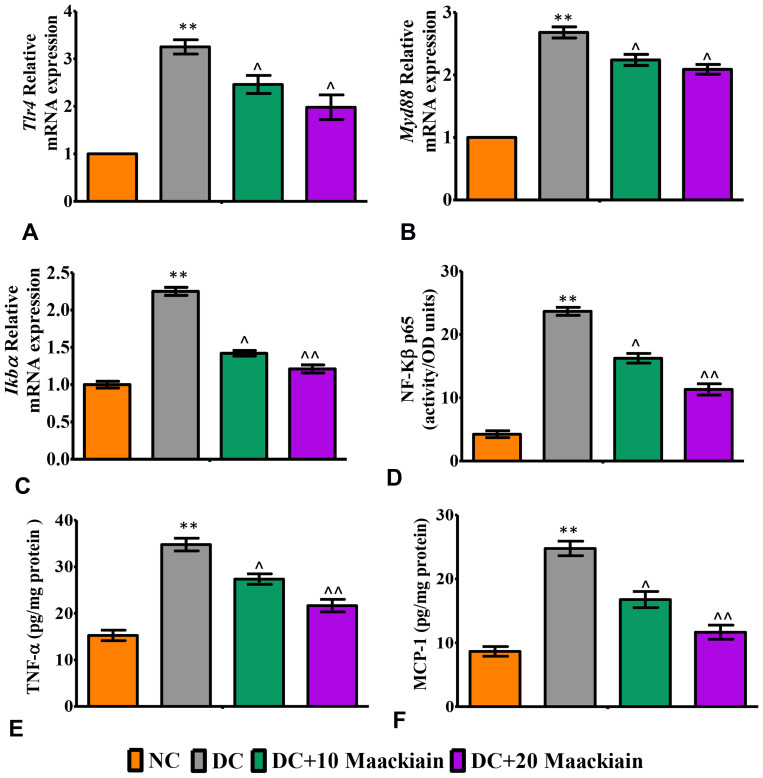

Effect of Maackiain on Inflammatory Status in Type 2 Diabetic Rat’s Kidney

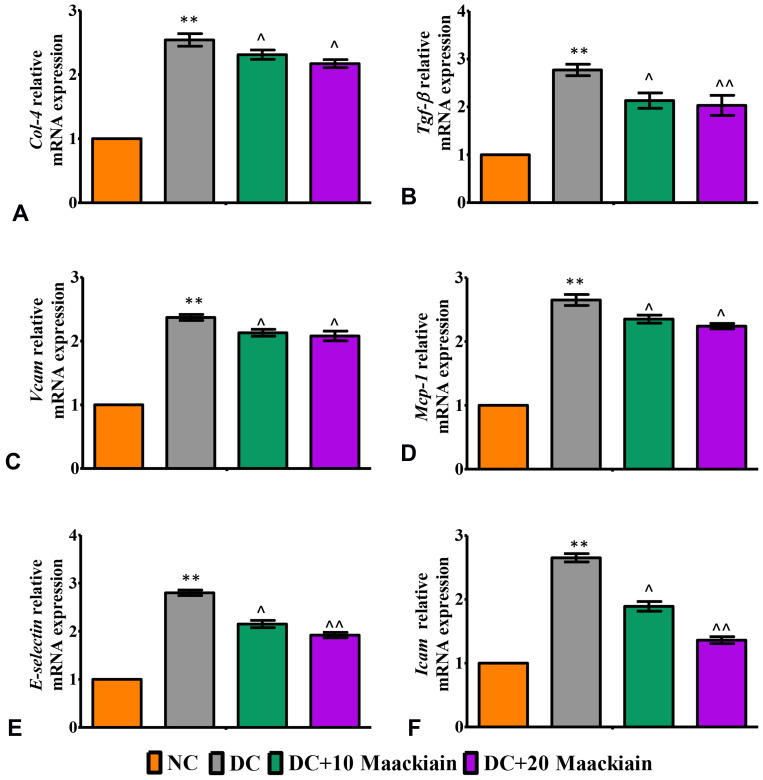

The inflammatory markers such as relative mRNA expression levels assessed by RT-qPCR, levels of cytokines and chemokines and activity of NF-κB p65 in kidney were depicted in Figures7 and 8. The mRNA expression levels of Tlr4 (Figure7A), Myd88 (Figure7B), ikbα (Figure7C), Col-4 (Figure8A), Tgf-β (Figure8B), Vcam (Figure8C), Mcp-1 (Figure8D), E-Selectin (Figure8E) and Icam (Figure8F) and levels of TNF-α (Figure7E) and MCP-1 (Figure7F) and activity of NF-κB p65 (Figure7D) were significantly elevated in diabetic rats in comparison with same parameters in the control group. Contrary to that, those inflammatory markers’ expression levels and activities were significantly (p<0.05) reduced after treating diabetic animals with either 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain than diabetic rats.

Figure7.

The effects of maackiain on renal inflammatory marks in HFD & low STZ induced diabetic rats. mRNA levels of (A); Tlr4; (B) Myd88 (C) Ikbα; (D) renal NF-κB p65 (ELISA results); (E) renal TNF-α (ELISA) levels; (F) renal MCP-1 (ELISA) levels. The data were expressed as the mean ± S.D, n=6, **p < 0.001 versus NC; ^^p<0.001 and ^p< 0.05 versus DC.

Abbreviations: NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; DC+10 maackiain, 10 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats; DC+20: 20 maackiain, 20 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats.

Figure8.

The effects of maackiain on renal inflammatory marks in HFD & low STZ induced diabetic rats. mRNA levels of (A) Col4 (B) Tgf-β; (C) Vcam; (D) Mcp-1; (E) E-Selectin; (F) Icam gene in rental tissue of experimental rats. The data were expressed as the mean ± S.D, n=6, **p < 0.001 versus NC; ^^p<0.001 and ^p< 0.05 versus DC.

Abbreviations: NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; DC+10 maackiain, 10 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats; DC+20: 20 maackiain, 20 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats.

Additionally, immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry experiments were used to determine the protein distribution pattern shown in Figure9. The protein expression levels of TLR4 (red color) (Figure9A), MYD88 (green color) (Figure9A), NF-κB p65 (Figure9B), IKBα (red color) (Figure9C) and MCP-1 (Figure9D) were elevated in diabetic rats, but those protein distributions were decreased in diabetic rats treated with either 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain.

Figure9.

The effects of maackiain TLR4/MYD88/NF-κB pathway protein destruction in HFD & low STZ induced diabetic rats. (A) Immunofluorescence double staining results of TLR4 (red color) and MYD88 (green color); (B) Immunohistochemistry staining results of NF-κB p65; (C) Immunofluorescence single staining results of IKBα (red color); (D) Immunohistochemistry staining results of MCP-1. Magnification = x40; Scale bar = 100µm.

Abbreviations: NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; DC+10 maackiain, 10 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats; DC+20 maackiain, 20 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats.

Effect of Maackiain on Apoptotic Status in Type 2 Diabetic Rat’s Kidney

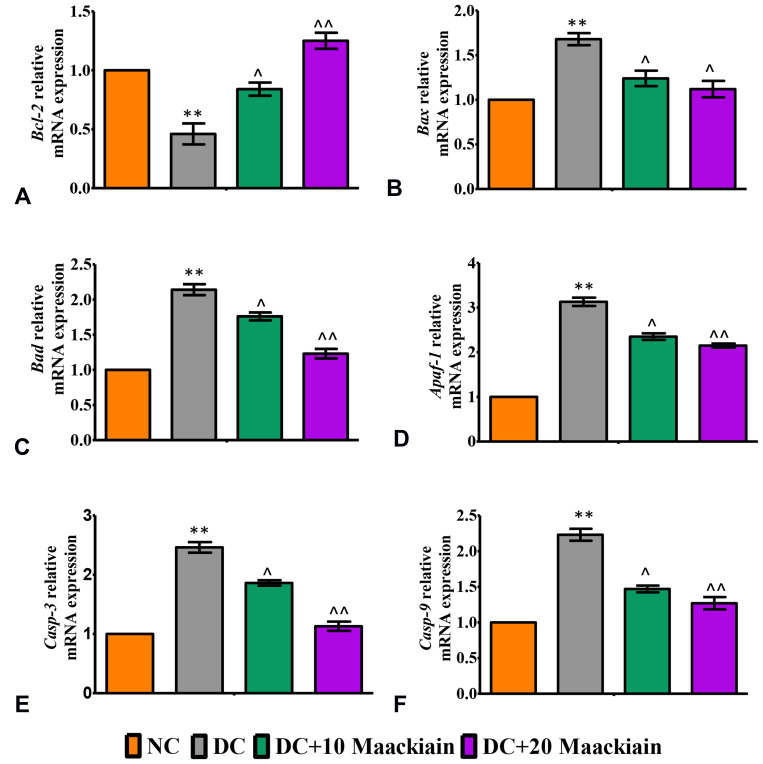

In diabetic rats’ kidneys, Bax (Figure10B), Bad (Figure10C), Apaf-1 (Figure10D), Caspase-3 (Figure10E) and Caspase-9 (Figure10F) gene expression levels were upregulated, while Bcl-2 (Figure10A) gene expression levels were reduced. When compared to untreated diabetic rats, 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain treatment resulted in areduction in Bax, Bad, Apaf-1, Caspase-3, and Caspase-9 mRNA expression but an increase in Bcl-2 mRNA expression. In comparison to untreated diabetic rats, maackiain administration at 10 or 20mg/kg resulted in adecrease in Bax, Bad, Apaf-1, Caspase-3 and Caspase-9 but an increase in Bcl-2 mRNA expression levels.

Figure10.

The effects of maackiain on renal apoptosis marks in HFD & low STZ induced diabetic rats. mRNA levels of (A) Bcl-2 (B) Bax; (C) Bad; (D) Apaf-1; (E) Caspase-3; (F) Caspase-9 gene in rental tissue of experimental rats. The data were expressed as the mean ± S.D, n=6, **p < 0.001 versus NC; ^^p<0.001 and ^p< 0.05 versus DC.

Abbreviations: NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; DC+10 maackiain, 10 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats; DC+20: 20 maackiain, 20 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats.

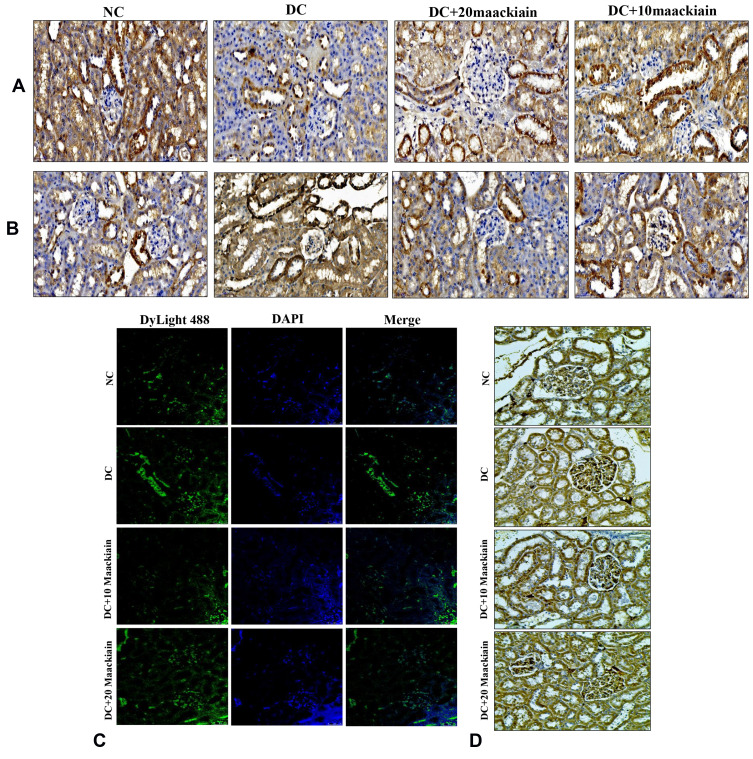

The findings of gene expression investigations in diabetic rats’ kidneys were reproduced in immunohistochemistry [decreased Bcl-2 protein distribution (Figure11A) and elevated Bax (Figure11B) and Caspase-9 (Figure11D)] and immunofluorescence [increased caspase-3 protein distribution] (Figure11C) in diabetic rat’s kidney. However, treatment with either 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain increased Bcl-2 protein distribution levels in the kidneys of only diabetic rats while decreasing Bax, Caspase-3, and Caspase-9 protein distribution levels.

Figure11.

The effects of maackiain on renal apoptosis marks in HFD & low STZ induced diabetic rats. Immunohistochemistry protein distribution of (A) Bcl-2; (B) Bax; (C) Immunofluorescence staining results of caspase-3 (green color); (D) Immunohistochemistry protein distribution of caspase-9 protein in rental tissue of experimental rats. Magnification = x40; Scale bar = 100µm.

Abbreviations: NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; DC+10 maackiain, 10 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats; DC+20: 20 maackiain, 20 mg/kg/bw maackiain treated diabetic rats.

Discussion

The present study attracts special attention due to the unavailability of information on the possible effects of maackiain against HFD/STZ-induced type 2 diabetes-induced renal complications. The study provided clear evidence of significant protection against diabetes-mediated alterations in metabolic profile, lipid profile, and kidney dysfunction. Furthermore, maackiain treatment resulted in significant attenuation in oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in kidneys of diabetic rats. Additionally, this study demonstrated the molecular mechanisms by which maackiain protects against HFD/STZ type 2 diabetes-induced oxidative stress (Nrf2/Keap1/ARE), inflammation (TLR4/MYD88/NF-κB) and apoptosis (intrinsic pathway) mediated renal damage.

Type-2 diabetes is characterized by chronic hyperglycemia and hypoinsulinemia and enhanced insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction.29,30 Elevated glucose and glycated haemoglobin levels throughout the experimental period and reduced serum insulin levels, arise in HOMA-IR, and areduction in HOMA-cell function were all indicators of hyperglycemia hypoinsulinemia, high insulin resistance, and low β-cell function, respectively. Similar findings were observed in astudy conducted by Mahmoud etal22 in HFD/STZ-induced diabetic rats. However, asignificant dose-dependent reversion in all these parameters was observed in HFD/STZ-induced diabetic rats after treating animals with 10 or 20mg/kg, indicating the anti-diabetic effect of Maackiain. The possibility of the anti-diabetic effect of flavonoids from S.flavescens is revealed from in silico molecular modeling and docking studies by interrupting Na+-glucose cotransporter activity in type 2 diabetes.31 The results of this study are well supported by findings of Shao etal,32 which revealed an inhibitory effect of S.flavescens extract against ahigh-fat diet and low-dose streptozotocin-induced metabolic alterations (increase in fasted blood glucose levels and worsened lipid profile, glycosylated serum protein, glycosylated hemoglobin index with pancreas damage). Additionally, the anti-diabetic effect of maackiain was evidenced via AMP-activated protein kinase activity.33

Dyslipidemia is another complication that is commonly associated with type 2 diabetic condition.34,35 Dyslipidemia in the diabetic milieu is responsible for developing diabetic nephropathy30 and is considered apotential risk factor for cardiovascular diseases.36 Usually, in biological conditions, insulin acts on lipoprotein lipase to convert triglycerides to fatty acids and glycerol. Fatty acids generated from triglycerides undergo either re-esterification or oxidation for storage in adipose tissue or for fuel in muscle, respectively. It is reported that insulin resistance suppresses lipoprotein lipase activity and leads to acondition of triglyceridemia.37 Furthermore, LDL transports cholesterol from the liver to other bodily tissues38 and vice versa HDL transports cholesterol from bodily tissues to liver39 to prevent cholesterol deposition. In the present study, HFD/STZ-induced diabetic rats presented with significantly increased total cholesterol, triglycerides and LDL levels with asignificant decrease in HDL levels. The results are in consonance with the findings of earlier reports.40,41 Furthermore, Hirano42 reported abnormal lipoprotein metabolism in diabetic nephropathy patients and managing dyslipidemia is particularly important otherwise, it leads to cardiovascular disease. Treatment of diabetic rats with either 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain resulted in significant improvement in dyslipidemia through asignificant decrease in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL levels with significant increase in HDL levels due to its insulinotropic effect or insulin secretagogue activity. These findings provided evidence that maackiain protects against diabetic kidney disease by improving lipid profile. The present findings support the earlier observations of Kim etal,43 who reported hypolipidemic effects (significant reduction in elevated TC, TG, and LDL-C levels and significant elevation in reduced HDL-C levels) of S.flavescens in poloxamer 407-induced hyperlipidemic and cholesterol-fed rats.

Evaluation of functional kidney biomarkers gives essential information related to the functioning of kidneys.44,45 In the present study, dysfunctioning of kidneys in diabetic rats was evident from the findings of kidney functionality assessment markers such as increased serum levels of BUN, urea, creatinine, albumin, 24 hrs urinary protein and urinary uric acid. The findings are in line with earlier observations of Wen etal,46 who reported that type 2 diabetic rats experienced kidney dysfunction through impairment in functional kidney markers. However, 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain treatment to diabetic rats dose-dependently decreased the serum levels of BUN, urea, creatinine, albumin, 24 hrs urinary protein, and urinary uric acid depicting significant improvement in kidney functional alterations induced by type 2 diabetic condition.

Numerous scientific studies have shown that oxidative stress is responsible for the pathophysiology of the diabetic kidneys.47,48 Oxidative stress is acondition that occurs when free radicals overwhelm antioxidant defenses.49 Malondialdehyde (MDA), alipid peroxidation product, induces kidney damage at cellular and tissue level and antiperoxidatives such as SOD, CAT, and GSH protect against oxidative stress-mediated injuries.50,51 In this study, significantly increased levels of MDA and significantly decreased activities of SOD, catalase and levels of GSH were observed in kidneys of diabetic rats. Similar observations were reported in kidneys of experimentally induced type 2 diabetic rat model.52 In contrast, treatment of diabetic rats with either 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain offered significant protection to oxidative stress in kidneys through the reduction in MDA levels and elevation in SOD and catalase enzyme activities and GSH levels. Earlier it was reported that flavonoids from roots of S.flavescens showed significant scavenging activities on 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical and ONOO-.53 Furthermore, the anti-oxidant activity of maackiain was revealed by the significant reduction in 6-OHDA-induced elevation in levels of ROS.54

Nowadays, the mechanism by which oxidative stress is mitigated has remained amore significant challenge. Recent studies claimed that the kidney cells are equipped with Nrf2, atranscriptional activator of antioxidant genes, to protect against oxidative stress.55 At normal physiological state, Nrf2 is coupled with its negative regulator Keap1 in the cytoplasm and at induced state, Nrf2 dissociates from Keap1 and enters into the nucleus to activate abattery of its regulated antioxidant genes such as Nqo1, Ho-1, Gclc and Gpx1.56 To further know whether maackiain activates Nrf2 signaling pathway to act against diabetes-induced oxidative stress, we examined the mRNA and protein expression levels of Nrf2 and its downstream genes and proteins. This study revealed that diabetic rats showed downregulation in mRNA (Nrf2, Nqo-1, Ho-1, Gclc and Gpx-1) and protein (Nrf2, NQO-1, NOX-4 and HO-1) expressions of Nrf2 pathway in association with an upregulation in mRNA and protein expressions of Keap1 in kidneys. Similar results of downregulation in mRNA and protein expressions of Nrf2 and its regulated genes and proteins and upregulation in mRNA and protein expression level of Keap1 were observed in experimentally induced type 2 diabetic rat model.46 Additionally, the importance of Nrf2 is evidenced from aNrf2 knockout study in which streptozotocin-induced Nrf2 knockout mice experienced hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and kidney damage.9,57 Interestingly, treating diabetic rats with maackiain at 10 or 20mg/kg body weight illustrated upregulation in Nrf2 and its regulated genes and proteins and downregulation in Keap1 gene and protein expression, demonstrating the activation of Nrf2 signaling pathway to counteract the diabetes-induced oxidative stress in kidneys.

Inflammation, in addition to oxidative stress, is acommon feature of chronic kidney disease and akey mediator in its progression.58 In recent years, the involvement of TLR4/MYD88/NF-κB pathway in aggravating inflammation in kidneys has surfaced.59 Studies have also been reported the implication of TLR4/NF-κB pathway in acute and chronic kidney injuries, including diabetic nephropathy.59,60 At normal physiological state, NF-κB is located in the cytoplasm with its negative regulator, IκBα, but at induced state, IκBα is degraded by IKKβ and allows NF-κB to enter into the nucleus to induce the expression of various effector molecules.12 TLR4 through MYD88 (adaptor protein) activates NF-κB, which in turn activates arange of effector molecules of inflammation such as pro-inflammatory cytokines, pro-fibrotic factors, chemokines and adhesion molecules.12 In this study, HFD/STZ-induced type 2 diabetic condition caused stimulation in TLR4/MYD88/NF-kB pathway through elevation in mRNA (TLR4, MYD88 and IκBα) and protein (TLR4, MYD88, IκBα and NF-κB) expression levels and NF-κB DNA binding activity. The activation of TLR4/MYD88/NF-κB pathway elevates the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α), chemokines (MCP-1) and mRNA expression levels of pro-fibrotic factors (MCP-1, TGF-β and Col-4), intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM1) vesicular adhesion molecule (VCAM1) and selectin (E-selectin). Earlier it was reported that induction of levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and pro-fibrotic factors as aresult of activation of NF-kB leads to macrophage infiltration, extracellular matrix deposition and fibrosis and ended up with huge damage to the kidney.27 In contrast, maackiain (10 or 20mg/kg) treatment showed anti-inflammatory effects in the form of reduced mRNA (Tlr4, Myd88 and Iκbα) and protein (TLR4, MYD88, IκBα and NF-κB) expressions along with decreased NF-κB DNA binding activity as aconsequence it limits the expression of various above mentioned inflammatory effector molecules and protects the kidney from diabetes-mediated inflammatory damage.

Previously, Ma etal20 demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effects of extracts of S.flavescens residues both in-vivo (inhibition of ear and paw swelling and reduction in paw swelling production levels of PGE2 in inflammatory tissues) and in-vitro (dose dependent inhibition in release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, NO and MCP-1 in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells) study findings. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory effects of maackiain is evidenced from its inhibitory action on LPS-induced NO production.61

A plethora of reports emphasized that oxidative stress and inflammation work together to activate apoptotic signals to further damage injury and lead to organ failure.5,62,63 The increased generation of ROS has been shown to upregulate NF-κB and vice versa NF-κB and/or its mediators have been shown to promote ROS production60,64 further. Inflammatory mediators or ROS generation in mitochondria due to hyperglycemia can release cytochrome cinto cytosol which then forms apoptosome to activate executioner caspase ie, caspase-3.65 The activated caspase-3 then cleaves DNA repair enzymes and cell stabilizing proteins, leading to apoptotic cell death.65 Thus, suppressing elevated oxidative stress and inflammation can be ideal for preventing apoptosis in the diabetic kidney. In the present study, mRNA expression levels of Bcl-2, Bax, Bad, Apaf-1, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 and protein expression levels of Bcl-2, Bax, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 were upregulated in kidneys of diabetes-induced rats indicating cellular apoptosis in the kidney. These findings are consistent with the earlier findings of elevated expression of apoptotic mediators and subsequent apoptotic cell death in diabetic kidneys.5,66 Whereas, treatment of diabetic rats with either 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain significantly reduced the expression of pro-apoptotic factors (Bax and Bad), Apaf-1, initiator caspase (Caspase-9), executioner caspase (Caspase-3) and significantly improved anti-apoptotic factors (Bcl-2) signifying the anti-apoptotic potential of maackiain. The observed attenuation after maackiain treatment in renal apoptosis might be due to observed suppression in oxidative stress and inflammation. The inhibitory action of maackiain on apoptosis is revealed by its anti-apoptotic effect on 6-OHDA-induced apoptosis.54 Supporting these observations, Kim etal67 demonstrated protective effect of S.flavescens against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion-induced intrinsic apoptosis by upregulating suppressed Bcl-2 expression and downregulating elevated Bax, cytochrome cand caspase-3 expression. Furthermore, supporting the observations of biochemical and molecular findings, histopathological findings revealed significant improvement in kidney architecture after treatment of diabetic rats with 10 or 20mg/kg maackiain.

Conclusions

In conclusion, HFD/STZ-induced type 2 diabetic rats showed substantial changes in metabolic parameters, lipid profile, renal functional markers, oxidative stress, inflammatory and apoptosis markers. However, treatment of HFD/STZ-induced type 2 diabetic rats with 20mg/kg body weight of maackiain showed more effect than 10mg/kg body weight of maackiain treatment in the reduction of metabolic, lipid profile and fictional kidney alterations, oxidative stress, inflammatory and apoptosis markers. The current research further showed maackiain nephroprotective benefits via modulating Nrf2/Keap1/ARE, TLR4/MYD88/NF-κB, and Bcl2/Bax/Caspase-3/Caspase-9 pathways in HFD/STZ-induced type 2 diabetes. Based on these results, maackiain has excellent potential for use as an agent rental change in diabetic patients.

Data Sharing Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 8th ed. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saeedi P, Salpea P, Karuranga S, etal. Mortality attributable to diabetes in 20–79 years old adults, 2019 estimates: results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108086. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anders H-J, Huber TB, Isermann B, Schiffer M. CKD in diabetes: diabetic kidney disease versus nondiabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(6):361–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anguiano Gómez L, Lei Y, Kumar Devarapu S, Anders H. The diabetes pandemic suggests unmet needs for ‘CKD with diabetes’ in addition to ‘diabetic nephropathy’—implications for pre-clinical research and drug testing. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(8):1292–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al Hroob AM, Abukhalil MH, Alghonmeen RD, Mahmoud AM. Ginger alleviates hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis and protects rats against diabetic nephropathy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;106:381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandes SM, Cordeiro PM, Watanabe M, Fonseca CD, Vattimo MF. The role of oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy in rats. Arch Endocrinol Metabol. 2016;60(5):443–449. doi: 10.1590/2359-3997000000188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahmoodnia L, Aghadavod E, Beigrezaei S, Rafieian-Kopaei M. An update on diabetic kidney disease, oxidative stress and antioxidant agents. JRenal Injury Prev. 2017;6(2):153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vomund S, Schäfer A, Parnham MJ, Brüne B, Von Knethen A. Nrf2, the master regulator of anti-oxidative responses. IntJMol Sci. 2017;18(12):2772. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang T, Huang Z, Lin Y, Zhang Z, Fang D, Zhang DD. The protective role of Nrf2 in streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2010;59(4):850–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bao L, Li J, Zha D, etal. Chlorogenic acid prevents diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation through modulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 and NF-ĸB pathways. IntImmunopharmacol. 2018;54:245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donate-Correa J, Luis-Rodríguez D, Martín-Núñez E, etal. Inflammatory targets in diabetic nephropathy. JClin Med. 2020;9(2):458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suryavanshi SV, Kulkarni YA. NF-κβ: apotential target in the management of vascular complications of diabetes. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su Q, Lv X, Sun Y, etal. Role of TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway in coronary microembolization-induced myocardial injury prevented and treated with nicorandil. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;106:776–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Modak M, Dixit P, Londhe J, Ghaskadbi S, Devasagayam TP. Recent advances in Indian herbal drug research guest editor: Thomas Paul Asir Devasagayam Indian herbs and herbal drugs used for the treatment of diabetes. Nutrition. 2007;40(3):163–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Feng B, Xiong X. Chinese herbal medicine for the treatment of obesity-related hypertension. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/757540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He X, Fang J, Huang L, Wang J, Huang XJ. Traditional usage, phytochemistry and pharmacology of an important traditional Chinese medicine. Sophora Flavescens Ait. 2015;172:10–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao X, He Q. Anti-tumor activities of bioactive phytochemicals in sophora flavescens for breast cancer. Research. 2020;12:1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nariai Y, Mizuguchi H, Ogasawara T, etal. Disruption of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90)-protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) interaction by (−)-maackiain suppresses histamine H1 receptor gene transcription in HeLa cells. JBiol Chem. 2015;290(45):27393–27402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee HW, Ryu HW, Kang M-G, etal. Potent selective monoamine oxidase Binhibition by maackiain, apterocarpan from the roots of Sophora flavescens. Bioorgan Med Chem Lett. 2016;26(19):4714–4719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma H, Huang Q, Qu W, etal. In vivo and invitro anti-inflammatory effects of Sophora flavescens residues. JEthnopharmacol. 2018;224:497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srinivasan K, Viswanad B, Asrat L, Kaul C, Ramarao P. Combination of high-fat diet-fed and low-dose streptozotocin-treated rat: amodel for type 2 diabetes and pharmacological screening. Pharmacol Res. 2005;52(4):313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahmoud AM, Ashour MB, Abdel-Moneim A, Ahmed OM. Hesperidin and naringin attenuate hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokine production in high fat fed/streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetic rats. JDiabetes Complicat. 2012;26(6):483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Test No.425: Acute Oral Toxicity: Up-And-Down Procedure. OECD Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizuguchi H, Nariai Y, Kato S, etal. Maackiain is anovel antiallergic compound that suppresses transcriptional upregulation of the histamine H1 receptor and interleukin‐4 genes. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2015;3(5):e00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Runtuwene J, Cheng K-C, Asakawa A, etal. Rosmarinic acid ameliorates hyperglycemia and insulin sensitivity in diabetic rats, potentially by modulating the expression of PEPCK and GLUT4. Drug Design Dev Ther. 2016;10:2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yelumalai S, Giribabu N, Kamarulzaman Karim SZO, Salleh NB, Salleh NB. In vivo administration of quercetin ameliorates sperm oxidative stress, inflammation, preserves sperm morphology and functions in streptozotocin-nicotinamide induced adult male diabetic rats. Archiv Med Sci. 2019;15(1):240. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2018.81038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giribabu N, Karim K, Kilari EK, Salleh N. Phyllanthus niruri leaves aqueous extract improves kidney functions, ameliorates kidney oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis and apoptosis and enhances kidney cell proliferation in adult male rats with diabetes mellitus. JEthnopharmacol. 2017;205:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khalil ASM, Giribabu N, Yelumalai S, Shahzad H, Kilari EK, Salleh N. Myristic acid defends against testicular oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis: restoration of spermatogenesis, steroidogenesis in diabetic rats. Life Sci. 2021;278:119605. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hudish LI, Reusch JE, Sussel L. β cell dysfunction during progression of metabolic syndrome to type 2 diabetes. JClin Investig. 2019;129(9):4001–4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qi Y, Ma J, Li S, W L. Applicability of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girija R, Aruna S, Sangeetha R. In silico molecular modelling and docking studies of sophora flavescens derived flavonoids against SGLT2 for type 2 diabetes mellitus. IntJBioinform Biol Sci. 2018;6(2):71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shao J, Liu Y, Wang H, Luo Y, Chen LJ. An integrated fecal microbiome and metabolomics in T2DM rats reveal antidiabetes effects from host-microbial metabolic axis of EtOAc extract from Sophora flavescens. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:1–25. doi: 10.1155/2020/1805418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang Y, Hao J, Tian D, etal. Antidiabetic activity of a flavonoid-rich extract from Sophora davidii (Franch.) Skeels in KK-Ay mice via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuzaka T, Shimano HJ. New perspective on type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia and non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. JDiabetes Investig. 2020;11(3):532–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawanami D, Matoba K, Utsunomiya K. Dyslipidemia in diabetic nephropathy. Renal Replacement Ther. 2016;2(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s41100-016-0028-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burkhardt RJ. Hyperlipidemia and cardiovascular disease: new insights on lipoprotein (a). Curr Opin Lipidol. 2019;30(3):260–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quispe R, Martin SS, Jones SR. Triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein–cholesterol ratio, glycemic control and cardiovascular risk in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. 2016;23(2):150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ference BA, Kastelein JJ, Ray KK, etal. Association of triglyceride-lowering LPL variants and LDL-C–lowering LDLR variants with risk of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2019;321(4):364–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu Y, He Z, King GL. Introduction of hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia in the pathogenesis of diabetic vascular complications. Curr Diabetes Rep. 2005;5(2):91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erejuwa OO, Nwobodo NN, Akpan JL, etal. Nigerian honey ameliorates hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Nutrients. 2016;8(3):95. doi: 10.3390/nu8030095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irondi EA, Oboh G, Akindahunsi AA. Antidiabetic effects of Mangifera indica Kernel Flour-supplemented diet in streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetes in rats. Food Sci Nutr. 2016;4(6):828–839. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirano T. Abnormal lipoprotein metabolism in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2014;18(2):206–209. doi: 10.1007/s10157-013-0880-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim HY, Jeong DM, Jung HJ, Jung YJ, Yokozawa T, Choi JS. Hypolipidemic effects of Sophora flavescens and its constituents in poloxamer 407-induced hyperlipidemic and cholesterol-fed rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31(1):73–78. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Sawalha NA, AlSari RR, Khabour OF, Alzoubi KH. Influence of prenatal waterpipe tobacco smoke exposure on renal biomarkers in adult offspring rats. Inhal Toxicol. 2019;31(5):171–179. doi: 10.1080/08958378.2019.1624897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Severin MJ, Campagno RV, Brandoni A, Torres AM. Time evolution of methotrexate-induced kidney injury: acomparative study between different biomarkers of renal damage in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2019;46(9):828–836. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wen W, Lin Y, Ti Z. Antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory activities of ethanolic seed extract of Annona reticulata L.in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:716. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duni A, Liakopoulos V, Roumeliotis S, Peschos D, Dounousi E. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis and evolution of chronic kidney disease: untangling Ariadne’s thread. IntJMol Sci. 2019;20(15):3711. doi: 10.3390/ijms20153711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee SJ, Kang JS, Kim HM, etal. CCR2 knockout ameliorates obesity-induced kidney injury through inhibiting oxidative stress and ER stress. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alotaibi MF, Bin-Jumah M, Elgebaly H, Mahmoud AM, Mahmoud AM. Olea europaea leaf extract up-regulates Nrf2/ARE/HO-1 signaling and attenuates cyclophosphamide-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in rat kidney. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;111:676–685. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdelhalim MAK, Qaid HA, Al-Mohy YH, Ghannam MM. The protective roles of vitamin eand α-lipoic acid against nephrotoxicity, lipid peroxidation, and inflammatory damage induced by gold nanoparticles. IntJNanomedicine. 2020;15:729–734. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S192740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park WS, Park MS, Kang SW, etal. Hesperidin shows protective effects on renal function in ischemia-induced acute kidney injury (Sprague-Dawley Rats). Transplant Proc. 2019;51(8):2838–2841. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.02.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maheshwari R, Balaraman R, Sen AK, Shukla D, Seth A. Effect of concomitant administration of coenzyme Q10 with sitagliptin on experimentally induced diabetic nephropathy in rats. Ren Fail. 2017;39(1):130–139. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2016.1254659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jung HJ, Kang SS, Woo JJ, Choi JS. Anew lavandulylated flavonoid with free radical and ONOO- scavenging activities from Sophora flavescens. Arch Pharm Res. 2005;28(12):1333–1336. doi: 10.1007/BF02977897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsai RT, Tsai CW, Liu SP, etal. Maackiain ameliorates 6-hydroxydopamine and SNCA pathologies by modulating the PINK1/parkin pathway in models of Parkinson’s disease in Caenorhabditis elegans and the SH-SY5Y cell line. IntJMol Sci. 2020;21(12):4455. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li X, Zou Y, Xing J, etal. Pretreatment with roxadustat (FG-4592) attenuates folic acid-induced kidney injury through antiferroptosis via Akt/GSK-3β/Nrf2 pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:6286984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ashrafizadeh M, Ahmadi Z, Samarghandian S, etal. MicroRNA-mediated regulation of Nrf2 signaling pathway: implications in disease therapy and protection against oxidative stress. Life Sci. 2020;244:117329. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi BH, Kang KS, Kwak MK. Effect of redox modulating NRF2 activators on chronic kidney disease. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 2014;19(8):12727–12759. doi: 10.3390/molecules190812727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pedruzzi LM, Cardozo LF, Daleprane JB, etal. Systemic inflammation and oxidative stress in hemodialysis patients are associated with down-regulation of Nrf2. JNephrol. 2015;28(4):495–501. doi: 10.1007/s40620-014-0162-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tan J, Wan L, Chen X, etal. Conjugated linoleic acid ameliorates high fructose-induced hyperuricemia and renal inflammation in rats via NLRP3 inflammasome and TLR4 signaling pathway. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63(12):e1801402. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201801402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu S, Tang S, Su F. Dioscin inhibits ischemic stroke-induced inflammation through inhibition of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway in arat model. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17(1):660–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee W, Ku S-K, Bae J. Anti-inflammatory effects of Baicalin, Baicalein, and Wogonin invitro and in vivo. Inflammation. 2015;38(1):110–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kandemir FM, Yildirim S, Kucukler S, Caglayan C, Mahamadu A, Dortbudak MB. Therapeutic efficacy of zingerone against vancomycin-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis and aquaporin 1permeability in rat kidney. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;105:981–991. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen X, Wei W, Li Y, Huang J, Ci X. Hesperetin relieves cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury by mitigating oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis. Chem Biol Interact. 2019;308:269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lingappan K. NF-κB in oxidative stress. Curr Opin Toxicol. 2018;7:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cotox.2017.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fuchs Y, Steller H. Live to die another way: modes of programmedcell death and the signals emanating from dying cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16(6):329–344. doi: 10.1038/nrm3999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marques C, Mega C, Gonçalves A, etal. Sitagliptin prevents inflammation and apoptotic cell death in the kidney of type 2 diabetic animals. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:538737. doi: 10.1155/2014/538737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim HY, Jeon H, Kim H, Koo S, Kim S. Sophora flavescens aiton decreases MPP(+)-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in SH-SY5Y cells. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:119. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]