Abstract

Agricultural best management practices (BMPs) reduce non-point source pollution from cropland. Goals for BMP adoption and expected pollutant load reductions are often specified in water quality management plans to protect and restore waterbodies; however, estimates of needed load reductions and pollutant removal performance of BMPs are generally based on historic climate. Increasing air temperatures and changes in precipitation patterns and intensity are anticipated throughout the U.S. over the 21st century. The effects of such changes on agricultural pollutant loads have been addressed by several authors, but how these changes will affect the performance of widely promoted BMPs has received limited attention. We use the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) to investigate potential changes in the effectiveness of conservation tillage, no-till, vegetated filter strips, grassed waterways, nutrient management, winter cover crops, and drainage water management practices under potential future temperature and precipitation patterns. We simulate two agricultural watersheds in the Minnesota Corn Belt and the Georgia Coastal Plain with different hydro-climatic settings, under recent conditions (1950–2005) and multiple potential future mid-century (2030–2059) and late-century (2070–2099) climate scenarios. Results suggest future increases in agricultural source loads of sediment, nitrogen and phosphorous. Most BMPs continue to reduce loads, but removal efficiencies generally decline due to more intense runoff events, biological responses to changes in soil moisture and temperature, and exacerbated upland loading. The coupled effects of higher upland loading and reduced BMP efficiencies suggest that wider adoption, resizing, and/or combining practices may be needed in the future to meet water quality goals for agricultural lands.

Keywords: Agricultural management, Best management practices, Climate change, Conservation tillage, Cover crops, Drainage water management, Hydrologic and water quality modeling, Nutrient management, Pollutant removal efficiency, Soil conservation, Vegetated buffers

INTRODUCTION

Excess nutrient loads from agricultural lands are perennial sources of impairment in waterbodies throughout the U.S. (Carpenter et al., 1998; Howarth et al., 2002) and can lead to harmful algal blooms (Michalak et al., 2013), eutrophication, and hypoxic “dead zones” (Rabalais et al., 2002). Nutrient loading from agricultural land is typically mitigated through best management practices (BMPs). Water quality management plans often identify the types of BMPs and participation rates needed to achieve an acceptable amount of loading.

Estimates of water quality benefits of BMPs often assume that future climatic conditions will resemble the historic record. That assumption is questionable as average air temperatures are expected to rise and the future precipitation regime is subject to uncertainty, but will likely include more intense storms (IPCC, 2014). There is a general agreement in the technical community that such changes are likely to have significant impacts on streamflow and pollutant loads in watersheds throughout the U.S. (Sinha et al., 2017; Leung and Wigmosta, 1999; Murdoch et al., 2000; Tomer and Schilling, 2009). Changes in precipitation and runoff characteristics also may alter the performance of BMPs directly or due to the indirect effects of these changes on plant and soil ecology. Together, these factors might render BMP implementation plans inadequate for meeting water quality goals.

Many field and modeling studies have examined BMP treatment efficiencies under current conditions. For example, conservation tillage is a widely-promoted BMP that limits soil disturbance and field studies have shown this practice effectively reduces erosion in burley tobacco and winter wheat plots (Benham et al., 2007) and cotton fields (Soileau et al., 1994). No-till management improves infiltration capacity and provides substantial erosion protection (Williams and Wuest, 2011). Alternative tillage practice effectiveness has also been explored in multiple watershed-scale modeling studies (Cho et al., 2016; Hui et al., 2014; Motsinger et al., 2016; Tuppad et al., 2010; Yuan et al., 2008).

Based on a review of seven Conservation Effects Assessment Program studies, Garbrecht et al. (2014) conclude that potential increases in rainfall amounts and intensity will stress conservation practices. A review of recent studies (Liu et al. 2016) found that although numerous authors have assessed performance of BMPs or the effect of climate change on pollutant load generation from agriculture, the state of the science on integrating climate change and BMP assessment is very limited. The potential alteration of BMP performance under alternative precipitation and temperature regimes has been studied with simulation models in a few studies. Woznicki et al. (2011) and Woznicki and Nejadhashemi (2012) assessed BMP performance under future climate in the Tuttle Creek Lake watershed in Kansas and Nebraska using the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT; Neitsch et al., 2011) and reported both positive and negative effects. Bosch et al. (2014) simulated no-till, cover crops, and filter strips in the Raisin, Maumee, Sandusky, and Grand River watersheds in Michigan, Illinois, and Ohio under predicted future precipitation and temperature using SWAT and suggested that no-till, cover crop, and filter strip BMPs will be less effective under wetter and warmer future conditions. Renkenberger et al. (2018) report similar results for a watershed in Maryland. However, these papers are all based on older global climate model (GCM) runs from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 3 (CMIP3; released 2005–2006), examine only a few GCMs (Bosch et al., Woznicki et al.) or ensemble averages for CMIP3 storylines (Renkenberger et al.), and do not incorporate recent improvements in spatial and temporal downscaling methods.

This study explores BMP performance under potential future air temperatures and precipitation patterns derived from the recent CMIP5 GCM runs with downscaling using constructed analogues. There are two principal study questions that focus on the potential relative change from historic to future conditions:

How will changes in air temperatures and precipitation patterns affect the ability of agricultural BMPs to mitigate pollutant loading to streams?

What are the implications of changes in agricultural source loads and BMP performance for meeting target pollutant reductions?

METHODS

MODELING APPROACH

We used SWAT, a watershed model that simulates physical processes associated with water and pollutant cycling and transport, crop growth and yields, and agricultural operations, to evaluate the performance of agricultural BMPs under a range of potential future temperature and precipitation regimes. SWAT was developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and simulates continuous hydrology and water quality at the watershed-scale (Arnold et al., 1998; Neitsch et al., 2011). SWAT was specifically designed to study dynamic effects of water and land management practices on diverse soil types, terrain, and under spatially varied weather, which makes SWAT a tool well suited for evaluating the water quality impacts associated with climate change. In addition, we selected SWAT for this study because it explicitly simulates growth of common cash crops (including response to air temperature, moisture regime, and altered CO2 concentrations) and many agricultural practices (e.g. tillage) and BMPs (e.g., filter strips). Furthermore, SWAT has been widely applied to test the effectiveness of agricultural conservation practices (e.g., Arabi et al., 2007; Cho et al., 2010; Ullrich & Volk, 2009), and various studies have verified that SWAT BMP simulations are representative of field implementation (e.g., Gitau et al., 2008; Watershed Evaluation Group, University of Guelph, 2017). We used SWAT 2012 (version 664) with some additional code modifications to model drainage water management practices for tiled cropland. These modifications are described in the BMP scenarios section.

STUDY WATERSHEDS

SWAT simulations were conducted for two agricultural watersheds that are representative of humid subtropical and humid continental climates, with the objective of assessing BMP performance in different hydro-climatic settings: the Ichawaynochaway Creek (IC) watershed in the Georgia Coastal Plain and the Little Cobb River (LCR) watershed in the Minnesota Corn Belt. Agricultural practices in these two regions differ. Some BMPs are appropriate in both areas (e.g. conservation tillage) but employ different timing. Other BMPs are region or practice specific (e.g. drainage water management used only on tile-drained fields).

Ichawaynochaway Creek (IC)

IC is located in southwest Georgia and is part of the Flint River Basin. The 1,624 km2 area selected for modeling was the upstream portion of the Ichawaynochaway basin (HUC 03130009). The long, hot growing season of this subtropical region allows the cultivation of cotton (Gossypium), corn for grain (Zea mays), and peanuts (Arachis hypogaea), which are generally planted in annual rotation (USDA-NASS, 2002, 2007, 2012; USDA Cropland Data Layer, 2008 – 2014). To represent this, three quarters of cropland in the model were established as corn-peanut-cotton crop rotations, 25% with corn planted the first year (CPTN), 25% with peanut planted the first year (PTNC), and 25% with cotton planted the first year (TNCP), ensuring that all three crops were cultivated in any given year. Fruit, vegetable, nut, grain, and legume crops were also grown (NASS, 2008 – 2014), which were represented with a general crop land-use class (AGRR, 25% of cropland in the model).

In recent years, about half of all cropland in Georgia was conventionally tilled with the remainder using conservation till or no-till (USDA, 2012). To represent this, conventional tillage was simulated for PTNC and TNCP rotations, conservation tillage for CPTN rotations, and no-till on AGRR. Mixing efficiency (EFTMIX) and mixing depth (DEPTIL) were set at 0.5 and 125 mm for conventional tillage, 0.25 and 100 mm for conservation tillage, and 0.05 and 25 for no-till. Crop stem and leaf biomass (stover) was left on fields at harvest when conservation tillage (30%) and no-till (100%) are practiced. Organically enriched soils of non-conventionally tilled fields tend to have a higher moisture retaining capacity. An empirical study conducted in Georgia found that USDA curve numbers for surface runoff were a few points lower under conservation tillage on cotton-peanut rotation plots (Feyereisen et al., 2008). This corresponds with recommendations in the conservation practice modeling guide for SWAT (Waidler et al., 2009) so curve numbers were reduced by 2 and 5 points for conservation and no-till mixing, respectively.

Application rates of synthetic fertilizer in the IC model followed recommendations from the Cooperative Extension at the University of Georgia for high yields of corn, cotton, and peanut crops (AESL, 2017). Producers irrigate about half of fields in the IC watershed to satisfy plant water demands when rain is inadequate. Annual irrigation depths vary widely (Hook et al., 2005) so inter-annual variability was represented with the auto-irrigation operation. Surface and groundwater supplies were applied to half of cropland in the IC model to represent irrigation (IRR_EFF = 70; IRR_ASQ = 0.2; AUTO_WSTR = 0.8). Modifications were made to the SWAT model code to ensure that drawdown due to agricultural groundwater extraction was consistent across model subbasins. All management operations were scheduled based on heat units to allow timing to change with climate (Table 1).

Table 1.

Heat unit scheduling for the Ichawaynochaway Creek (IC) and Little Cobb River (LCR) watershed models.

| Operation | Fraction of heat units | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| IC watershed model | ||||

|

| ||||

| Grain corn (CORN) | Peanuts (PNUT) | Cotton (COTS) | Generic crop (AGRR) | |

| Tillage | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 | NA (No-till) |

| Planting | 0.259 (2,062 PHU) | 0.259 (1,548 PHU) | 0.259 (2,277 PHU) | 0.259 (1,500 PHU) |

| Fertilizer application | 0.259 (98 kg-N/ha + 28 kg- P2O5/ha) | 0.259 (45 kg-N/ha + 12 kg- P2O5/ha) | 0.259 (27 kg-N/ha + 28 kg- P2O5/ha) | 0.259 (62 kg-N/ha + 20 kg- P2O5/ha) |

| Fertilizer application | 0.384 (196 kg-N/ha) | 0.305 (54 kg-N/ha) | 0.384 (125 kg-N/ha) | |

| Harvest/Kill | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

|

| ||||

| LCR watershed model | ||||

|

| ||||

| Grain corn (CORN) | Soybean (SOYB) | |||

|

| ||||

| Tillage | 0.032 | 0.074 | ||

| Planting | 0.046 (1,383 PHU) | 0.105 (1,120 PHU) | ||

| Fertilizer application | 0.104 (191 kg-N/ha + 84 kg-P2O5/ha) | |||

| Harvest/Kill | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

In SWAT, planting and pre-planting practices are scheduled using base-zero heat units that have accumulated since the first day of the year (expressed as a fraction of potential heat units (PHU0) for the entire year). After planting, practices are timed based on the fraction of heat units that have been accumulated by the plant since seeding (expressed as a fraction of potential heat units (PHU) needed for the plant to reach maturity).

Little Cobb River (LCR)

The Little Cobb River is a tributary of the Cobb River, which flows into the Le Sueur River in southern Minnesota (HUC 07020011). Land use in the 338 km2 watershed is primarily agriculture (approximately 86%). NASS (2008–2014) spatial coverages show that corn-soybean (Zea mays-Glycine max)rotations are the major crops. Half of cropland was specified as a corn-soybean rotation and half as soybean-corn to ensure that both crops are grown in any given year. Management practices for corn and soybeans (table 1) were based on prior studies in the Le Sueur River watershed (Folle, 2010a; Folle et al. 2010b), and nitrogen fertilization rates were based on the survey of Bierman et al. (2011). For the baseline model, all fields were simulated as receiving conventional tillage in the spring before planting and in fall after harvest of the summer crop (Folle, 2010a).

Artificial drainage (via tile drains) is widely used in this region because of poorly drained glacial/lacustrine soils and relatively flat topography. Tile drains were explicitly simulated for row crops on flat slopes (0 to 3%) and on poorly drained soils (Hydrologic Soil Group (HSG) designated as D, A/D, B/D, or C/D). Tile drains were simulated using the Hooghoudt and Kirkham equations as implemented in the SWAT model by Moriasi et al. (2013). Tile drain specific parameters were based on a previous SWAT application in the Mason Ditch watershed in Indiana (Boles et al., 2015). Sediment concentration in lateral flow is a constant that is user defined in SWAT. The code was modified to instead use the sediment concentration in runoff for both lateral and tile flow.

SWATDEVELOPMENT AND CALIBRATION

In SWAT, Hydrologic Response Units (HRUs) represent unique combinations of soil, slope, and land use. Plant growth, landscape hydrology, sheet and rill erosion, and nutrient processing and export are simulated at the HRU level then routed to model reaches. Spatial datasets were overlain to develop model HRUs (Table 2). Model subbasins were established from HUC10 catchments and model reaches were identified from the National Hydrography Dataset (NHD) high-resolution stream layer.

Table 2.

Landscape and hydrographic data sources for SWAT model development.

| Landscape and Hydrography Data | Source |

|---|---|

| Digital elevation model (DEM; 10 meters) | United States Department of Agriculture GeoSpatial Data Gateway |

| Soil classes and properties | National Resource Conservation Service’s Soil Survey Geographic (SSURGO) |

| Land use/cover | National Land Cover Database (2006) |

| Cultivated crops | Cropland Data Layer (2008 – 2014) |

| Watershed boundary and catchment delineations | Hydrologic Response Units (HUC10s) |

| Stream reaches | National Hydrography Dataset (NHDPlus) |

Both models were calibrated using historic weather forcing series. Instead of using ground weather station (point) data, we selected gridded data products to represent spatial variability in weather patterns across the watersheds. Daily precipitation series were developed from PRISM (Parameter-elevation Relationships on Independent Slopes Model), a 4-km resolution gridded product (Daly et al, 2008, 2015). Data from NLDAS2 (North American Land Data Assimilation System; ~14 km resolution) were processed to develop air temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation, and wind forcing series (Mitchell et al., 2004). Potential evapotranspiration was computed using the Penman-Monteith method.

The model calibration consisted of iteratively refining parameters within recommended ranges to improve the simulation of average monthly hydrology and water quality under current land management practices. Fit to USGS flow gage records was evaluated at a monthly time-step with the Nash Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) for water years 2005–2015. Both flow calibrations were rated highly (IC NSE = 0.90; LC NSE = 0.72), as evaluated by the criteria suggested by Moriasi et al. (2007), and relative seasonal volume errors were less than 15%. In addition, visual comparisons of simulated and observed flows (e.g., hydrographs, flow duration curves, monthly flow volumes) were used to calibrate the models. Water quality data were limited, thus the models were calibrated based on regional estimates of upland sediment and nutrient export (White et al., 2015) and with available concentration samples and paired loads. Both models provided reasonable representations of baseline water quality (relative median load errors for IC: TSS = 3.28%, TN = −5.37%, TP = −0.67%; LCR: TSS = 6.42%, TN = 6.36%, TP = −0.18%). that were appropriate for climate and conservation practice sensitivity tests.

AGRICULTURAL BMPSCENARIOS

We represented agricultural BMPs following recommendations for SWAT applications (Waidler et al., 2009), except for a few code modifications described below. Assessed BMPs are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Best Management Practices simulated with the Ichawaynochaway Creek (IC) and Little Cobb River (LCR) SWAT watershed models.

| BMP | Abbreviation | IC | LCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservation tillage | CT | X | X |

| No-till | NT | X | |

| Grassed waterways | GW | X | |

| Filter strips | FS | X | X |

| Nutrient management | NM | X | X |

| Fertilizer substitution[a] | PM | X | |

| Winter cover crops | CC | X | X |

| Winter cover crops fertilized and/or irrigated | CCf, CCi, CCfi | X | |

|

| |||

| Drainage water management BMPs | |||

|

| |||

| Controlled drainage | CD | X | |

| Bioreactor | BR | X | |

| Saturated buffer | SB | X | |

| Treatment wetland | TW | X | |

[a] Substitution of synthetic fertilizers with poultry manure

Conventional tillage can exacerbate soil erosion. Conservation tillage and no-till reduce soil disturbance, and plant residue is left to enrich soil with nutrients and moisture retaining organic material. Our BMP scenarios included 1) converting all conventionally tilled cropland to cropland under conservation tillage, and 2) adopting no-till on all conventionally tilled cropland.

Grassed waterways are vegetated channels that slow field runoff, facilitate infiltration, and trap sediment and pollutants. Key design considerations include the channel shape and dimensions, slope, and vegetative cover, and these features were represented in the SWAT grassed waterway management operation. Grassed waterway widths in the IC model followed recommendations (25 feet) outlined in the BMPs for Georgia Agriculture Manual (GSWCC, 2013). Lengths of grassed waterways were set as equivalent to the HRU length, and depths were estimated based on trapezoidal channel geometry. Channel slope was set relative to the HRU slope (75%) and a dense, tall grass was represented using a relatively high Manning’s n (0.08). The default value of the sediment re-entrainment parameter (GWATSPCON = 0.005) was applied.

Vegetated filter strips line the downslope side of an agricultural field and filter runoff and associated nutrients. Filter strips were simulated using the built-in filter strip management operation. Filter strip area and flow concentration parameters were set at values recommended in the conservation practice modeling guide (Waidler et al., 2009; VFSCON = 0.5; VFSRATIO = 50; VFSCH = 0).

Fertilizer can facilitate crop growth; however, excessive application can harm beneficial microorganisms and increase pollution from fields. Application of chemical fertilizers followed recommendations for high crop yields in the baseline models. Lower application rates used for nutrient management were about 35% less for phosphorus and 15% less for nitrogen fertilizers (AESL, 2017), and these reductions were applied uniformly for the nutrient management scenario with the IC model. Randall et al. (2017), suggest that 135 kg-N/ha provides the maximum return on investment (yield vs. cost) at typical sites in southern MN under current prices. Therefore, we reduced the nitrogen fertilization of corn from 191 to 135 kg-N/ha for the LCR nutrient management scenario.

Georgia is a leading producer of poultry, making fresh broiler manure plentiful and locally available for use as a fertilizer. An alternative fertilization strategy was simulated by substituting half of synthetic fertilizer with fresh boiler manure. Nitrogen and phosphorus application rates can be managed separately when synthetic fertilizers are used. This is not the case for manure. Manure application was estimated for half nitrogen substitution using the approach by Ritz and Merka (2016), although both chemical nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer application rates were halved.

Cover crops planted after the fall harvest stabilize soils over the winter. Red clover (Trifolium pretense), a legume cover crop that fixes nitrogen (Hancock, 2014), and rye (Secale cereale) are recommended winter cover crops for southwest Georgia (Baldwin and Creamer, 2016; Hancock, 2014; Lee et al., 2008). For the IC cover crop scenario, red clover was grown prior to nitrogen-demanding corn and rye was grown prior to peanuts and cotton. Four additional scenarios were developed for IC to examine benefits and consequences associated with fertilizing and irrigating cover crops. Fertilizer application rates for rye (18 kg-N/ha and 9 kg-P2O5/ha) and red clover (23 kg-P2O5/ha) recommended by the University of Georgia Cooperative Extension were assumed (GCE, 2008). Rye is also commonly grown as a winter cover crop in Minnesota (MDA, 2017). Therefore, it was used as the cover crop for LCR.

Base zero heat units are reset in SWAT when the summer cash crop is harvested and cover crops are scheduled to be planted roughly a few weeks later (fraction of base zero heat units = 0.05). The planting of winter cover crops generally occurs mid-fall when soils have regained moisture and temperatures have cooled. To ensure that cover crops are planted at an appropriate time, an earliest planting date was added as a parameter. We modified the SWAT code so that both the heat unit requirement and the date criterion must be satisfied to trigger planting.

Drainage water management BMPs, including controlled drainage, bioreactors, saturated buffers, and treatment wetlands, were also studied for the densely tile drained LCR where tile flow constitutes 39% of the overall water balance. Drainage water management BMPs are not explicitly represented in the latest version of SWAT so we modified the code to represent these BMPs. Adjustable weirs or flashboards at tile flow outlets are used to change the depth of the water table for the controlled drainage BMP. To represent controlled drainage in SWAT, the depth of the tile drain is altered based on plant growth requirements to maximize biomass and reduce nutrient losses. The tile drain is closer to the surface during the winter and spring months when no crop is growing (set to 300 mm), and the depth of the tile drain is gradually increased during the growing season based on root development (up to 1000 mm). Bioreactors are trenches with wood chips or other carbon rich material that facilitate denitrification. Reduction in nitrate-nitrogen in tile flow was implemented using the Illinois Bioreactor Performance Curve (http://www.wq.illinois.edu/dg/). Saturated buffers receive tile flow and reduce nutrient loads to the waterways via plant uptake and denitrification. To simulate this BMP, we added a new subroutine called satbuf.f to the SWAT code that applies the empirical equations used for vegetative filter strips. The sources of flow and nutrients routed to saturated buffers include surface runoff, lateral flow, and tile flow. The subroutine satbuf.f is called from the subroutine subbasin.f if the flag vfsi is set to 2 in the model. Treatment wetlands are placed in series in tile lines. The SWAT model limits wetlands to one per subbasin, which is not adequate for representing treatment wetlands; instead, we employed the pothole sub-routine (pothole.f). Minor edits were made to the sub-routine, which included diversion of tile flow and associated sediment and nutrients to the wetland in addition to surface runoff and lateral flow. The area of each pothole (or treatment wetland) was set to 1 percent of the area of the draining HRU.

To isolate the impacts on BMP performance under potential future climate, we assume that other landscape characteristics, such as soil properties, slope, land use, and cash crops that are cultivated in these watersheds remain constant.

FUTURE AIR TEMPERATURE AND PRECIPITATION SCENARIOS

Potential future air temperature and precipitation scenarios were developed from GCM output from CMIP5 model runs, statistically downscaled in space (4 km resolution) and time using the Multivariate Adaptive Constructed Analogs (MACA) method (Abatzoglou and Brown, 2012). Each future scenario is paired with MACA-downscaled output for the historic run of the same GCM to reduce bias associated with the characteristics of the GCM. MACA is a statistical downscaling and bias correction method using constructed analogs that captures the scales relevant for impact modeling while preserving time-scales and patterns of meteorology as simulated by GCMs. The training dataset for MACA downscaling incorporates PRISM monthly precipitation and air temperature with daily departures from NLDAS-2 (Abatzoglou, 2013), helping ensure consistency with the weather data used in the SWAT calibrations. An important advantage of MACA relative to other statistically downscaled data sets is that, in addition to precipitation and temperature, it downscales humidity, wind, and downward shortwave radiation, allowing calculation of PET using an energy balance approach that is consistent with the precipitation and temperature time series. Downscaled data (MACAv2-METDATA) from five GCMs were selected for each watershed to represent a range of possible future conditions under high radiative forcing of 8.5 W/m2 by 2100 (Representative Concentration Pathway [RCP] 8.5; Riahi et al., 2011).

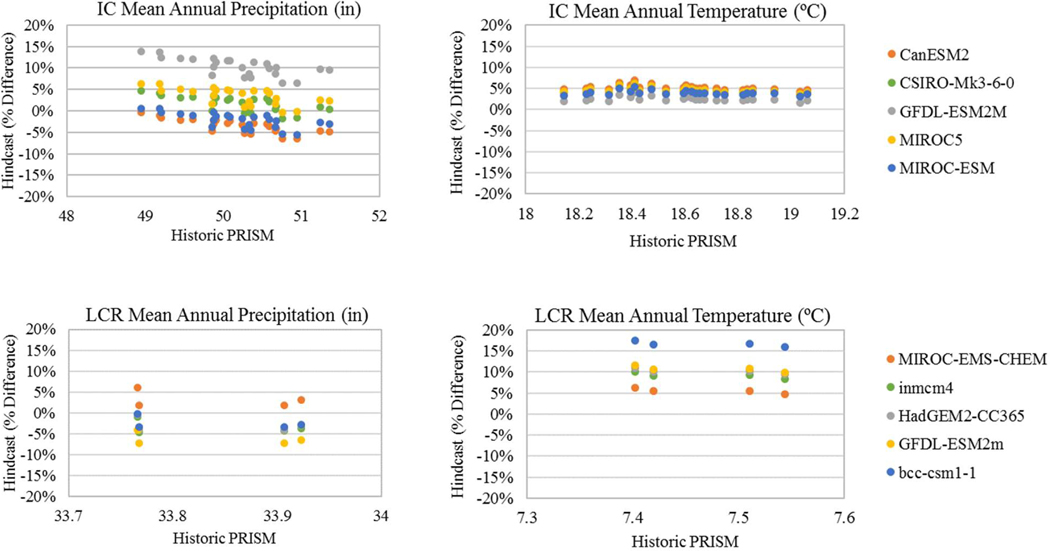

Hindcast predictions of mean annual precipitation were generally comparable to historic gridded data from PRISM (2000–2015), with some GCMs overpredicting and some underpredicting historic precipitation (±14% for IC subbasins and ±7.5% for LCR subbasins), and hindcast predictions of mean annual air temperature were within ±1.3°C of historic gridded data from PRISM for IC subbasins (figure 1). The five GCMs for LCR all appear to be biased high for historic air temperature, with the maximum difference compared to PRISM being +1.3°C (bcc-csm1–1). The hindcast GCM precipitation and air temperature data were fairly representative of historic records for the study watersheds and were, therefore, suitable for evaluating the potential relative change in BMP performance over time. For each study area the selected GCMs bound the range of projected future temperature and moisture conditions by 2100 across all GCMs (RCP 8.5 only) in the CMIP5 archive. We chose RCP 8.5, the highest radiative forcing, to examine BMP performance under precipitation and temperature conditions that differ significantly from predicted historic climate. We modeled three periods: a 1951 – 2005 baseline period, a mid-century period from 2030 – 2059 (centered at 2045), and a late-century period from 2070 – 2099 (centered at 2085).

Figure 1.

Percent difference in Global Climate Model hindcast predictions of mean annual precipitation and air temperature (relative to historic PRISM data) for model subbasins in the Ichawaynochaway Creek (IC; 24 subbasins) and Little Cobb River (LCR; 4 subbasins) SWAT watershed models (2000–2015).

Many plant species decrease stomatal conductance to satisfy carbon demands as atmospheric CO2 increases, and this reduces vegetative transpiration and alters terrestrial water cycling (Franks and Beerling, 2009; Lammertsma et al, 2011). SWAT reduces water vapor losses by vegetation as CO2 concentrations rise (Morison and Gifford, 1983; Easterling et al., 1992). We specified future atmospheric CO2 concentrations consistent with RCP 8.5 at 513 ppmv mid-century (2045) and 801 ppmv late-century (2085) (IPCC, 2013, table All.4.1). Historic CO2 was set to the 1978 value of 335 ppm in Meinshausen et al, 2010.

RESULTS

POLLUTANT LOADING UNDER CURRENT MANAGEMENT AND FUTURE CLIMATE

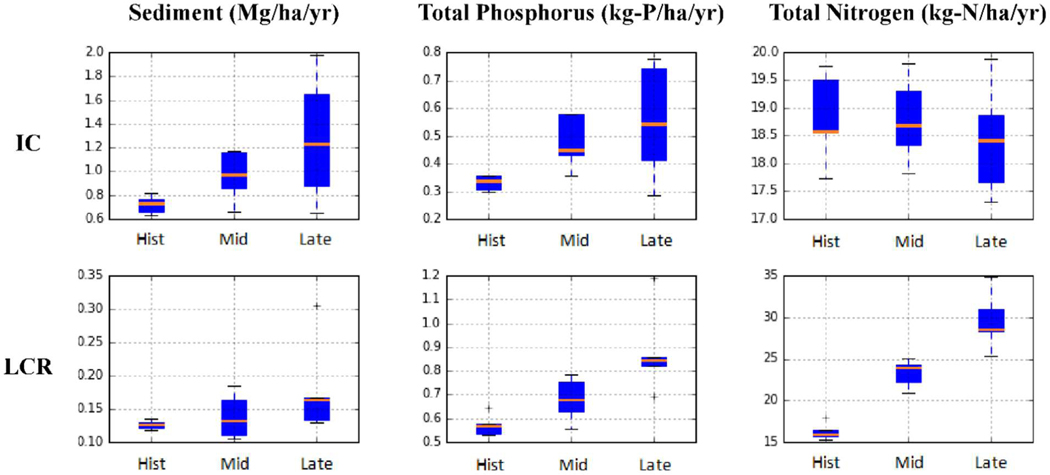

Simulated pollutant loads for cropland under current management strategies (baseline scenario) with hindcast and futurecast climate scenarios are shown in figure 2. Pollutant loads from cropland generally increase under simulated future conditions. Variability is greater around median yields (orange lines) in the late 21st century than earlier periods for IC; this is because annual precipitation is more similar across GCMs for the historic period than future periods. For future periods, some GCMs project increasing precipitation volume and intensity, aggravating sheet and rill erosion as well as dissolved constituent transport (e.g., sediment loads double for CSIRO-Mk3–6-0, which estimates that mean annual precipitation in IC will be 10% higher in the late-century). Sediment loads are higher than historic loads in IC and LCR even for GCMs that project decreasing mean annual precipitation in the late-century due to more intense storm events. GCM scenarios are generally more consistent for the LCR model than the IC model, as shown by the narrower range in simulated yields. Similarly to sediment, more intense storm events across the GCM scenarios (even for those where mean annual precipitation is projected to decrease) increase dissolved and particulate P loads, resulting in projected higher mean total phosphorus (TP) yields for both watersheds by midcentury. Higher mean total nitrogen (TN) yields occur in response to GCMs projecting wetter mid-century conditions for IC and LCR (e.g., for GFDL-ESM2m TN loads increase by 121% for a 20% increase in mean annual precipitation in LCR). This is due to more N leaching from the root zone and N transported to streams by more frequent and higher intensity runoff events. However, the median TN load across all GCM scenarios for the IC model (orange lines) decreases from the mid to late 21st century due hotter temperatures that increase evapotranspiration and, for select GCMs, lower precipitation, which limits dissolved N transport. This is not the case for LCR where median projected TN loads increase by mid-century and are suggested to nearly double by late-century.

Figure 2.

Range of mean annual pollutant loads for five Global Climate Model predictions of future changes in air temperature and precipitation. Loads shown for cropland under baseline management and historic (Hist), mid-century (Mid), and late-century (Late) conditions in the Ichawaynochaway Creek (IC) and Little Cobb River (LCR) SWAT watershed models.

EFFECTS OF CHANGES IN AIR TEMPERATURE AND PRECIPITATION ON CROP BIOMASS AND BMPPERFORMANCE

Changes in mean annual precipitation from historic to late-century in the IC watershed ranged from −9.1% to 10% across the five GCMs and mean annual air temperature was predicted to increase across the GCMs, ranging from 3.8°C to 5.6°C. We also examined the changes in crop biomass relative to the historic period with the SWAT models. Crop biomass increased by about a quarter from historic to late-century for GCM scenarios that predicted nearly the same or an increase in mean annual precipitation but relatively lower changes in mean annual air temperature. These conditions extend the crop growing season without significantly worsening heat or water stress in the IC watershed. Crop biomass was still increased, but to a lesser degree (by about 5%), for the scenario with the most extreme change in annual temperature (MIROC-EMS). For this scenario warmer spring weather supported the initial stages of crop growth but later in the growing season crops were hindered by hotter weather. The GCM predicting the highest change in mean annual precipitation (20%) with the lowest increase in mean annual air temperature (GFDL-ESM2m) generated the highest increase in crop biomass in LCR. Conversely, when precipitation decreased, and air temperature increased the most from historic to late-century, crop growth was stunted by water stress and biomass production declined by about 10%.

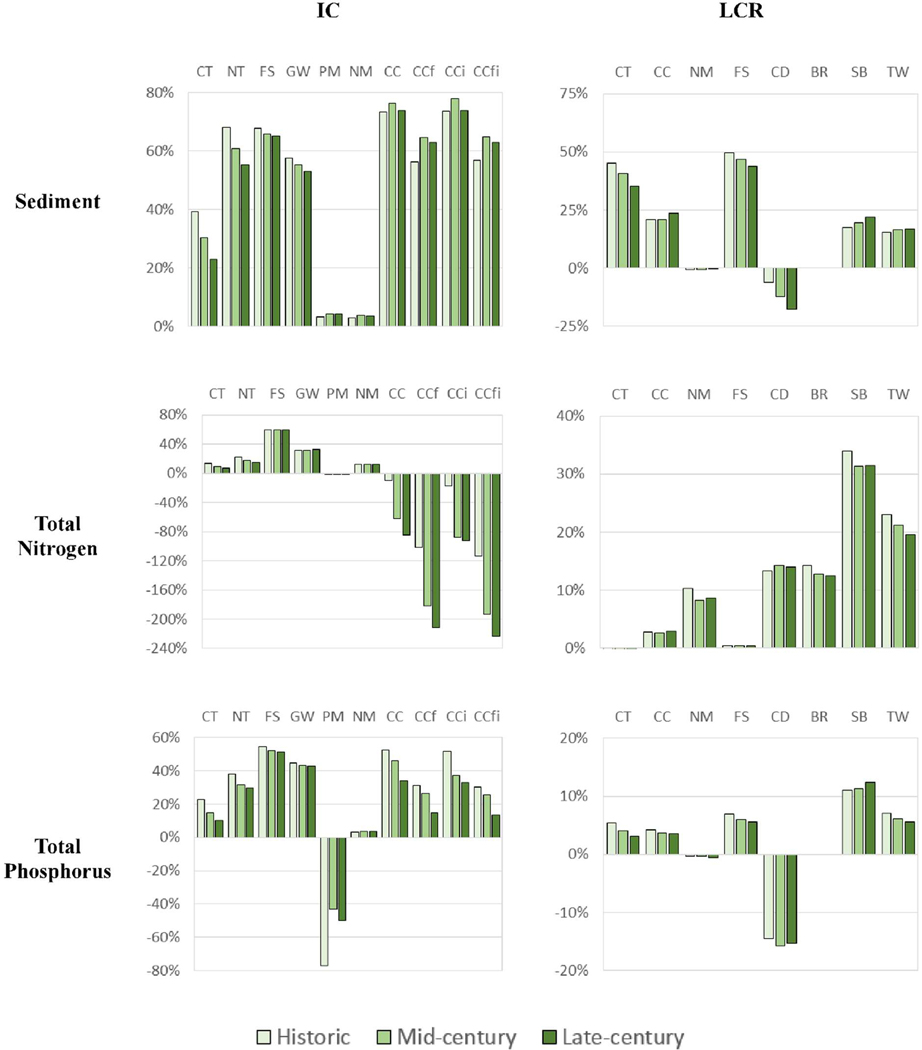

Simulated BMP removal efficiencies were also altered by climate as shown for the historic, mid-century, and late-century scenarios in figure 2. Upland loading rates to stream reaches are provided in table 4.

Table 4.

Upland loading rates to stream reaches for BMP applications in the Ichawaynochaway Creek and Little Cobb SWAT models. Load shown for Sediment (Mg/ha/yr), Total Phosphorus (kg-P/ha/yr), Total Nitrogen (kg-N/ha/yr) and Nitrite-N + Nitrate-N (kg-N/ha/yr) averaged across GCM scenarios for historic, mid-century, and late-century periods. BMPs include conservation tillage (CT), no-till (NT), filter strips (FS), grassed waterways (GW), poultry manure (PM), nutrient management (NM), cover crops (CC with fertilization (f) or irrigation (i) practices), controlled drainage (CD), bioretention (BR), saturated buffers (SB), and treatment wetlands (TW). Negative removal efficiencies indicate pollutant loading increases with BMP application.

| BMP | Sediment (Mg/ha/yr)_ | Total Phosphorus (kg-P/ha/yr) | Nitrite + Nitrate (kg-N/ha/yr) | Total Nitrogen (kg-N/ha/yr) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Historic | Mid- century | Latecentury | Historic | Mid- century | Latecentury | Historic | Mid- century | Latecentury | Historic | Mid- century | Latecentury | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Ichawaynochaway | ||||||||||||

| No BMP | 0.73 | 0.97 | 1.28 | 0.33 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 15.44 | 15.49 | 15.03 | 18.83 | 18.76 | 18.42 |

| CT | 0.46 | 0.68 | 1.00 | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 15.10 | 15.24 | 14.78 | 17.29 | 17.72 | 17.66 |

| NT | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 14.67 | 14.69 | 14.42 | 16.36 | 16.80 | 16.90 |

| FS | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 5.87 | 5.78 | 5.54 | 7.66 | 7.58 | 7.41 |

| GW | 0.31 | 0.44 | 0.60 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 11.07 | 11.01 | 10.61 | 12.84 | 12.79 | 12.47 |

| PM | 0.71 | 0.93 | 1.22 | 0.59 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 14.38 | 14.39 | 13.77 | 19.00 | 18.77 | 18.64 |

| NM | 0.71 | 0.94 | 1.24 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 13.41 | 13.58 | 13.05 | 16.38 | 16.50 | 16.06 |

| CC | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 19.84 | 30.51 | 33.64 | 21.13 | 32.41 | 36.39 |

| CCf | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 39.20 | 55.78 | 59.70 | 41.10 | 58.39 | 63.21 |

| CCi | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 21.32 | 36.49 | 35.10 | 22.65 | 37.95 | 37.91 |

| CCfi | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 41.80 | 58.34 | 62.21 | 43.76 | 60.99 | 65.78 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Little Cobb | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| No BMP | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.88 | 14.50 | 21.10 | 26.80 | 16.30 | 23.30 | 29.60 |

| CT | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 0.85 | 14.75 | 21.36 | 27.15 | 16.48 | 23.51 | 29.90 |

| CC | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.85 | 14.11 | 20.55 | 26.03 | 15.86 | 22.70 | 28.75 |

| NM | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 13.01 | 19.36 | 24.49 | 14.81 | 21.56 | 27.29 |

| FS | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.83 | 14.43 | 21.01 | 26.70 | 16.15 | 23.14 | 29.41 |

| CD | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 1.02 | 12.57 | 18.08 | 23.06 | 14.65 | 20.63 | 26.28 |

| BR | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.88 | 12.43 | 18.41 | 23.47 | 14.23 | 20.61 | 26.27 |

| SB | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.77 | 9.59 | 14.47 | 18.38 | 11.32 | 16.60 | 21.08 |

| TW | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.83 | 11.18 | 16.61 | 21.55 | 12.96 | 18.79 | 24.33 |

Filter strips and grassed waterways

Projected future increases in precipitation volume and intensity could lead to increased field erosion, causing more sediment to be delivered to filter strips and grassed waterways. Simulated mean annual upland sediment yields from cropland in the IC model increase from 0.73 Mg/ha/yr under historic conditions to 0.97 Mg/ha/yr in the mid-century, and to 1.28 Mg/ha/yr in the late-century without BMPs. Similarly, in LCR, loads increase from 0.13 Mg/ha/yr to 0.18 Mg/ha/yr. Higher mean annual precipitation increases loads to filter strips and grassed waterways and degrades their removal efficiencies. This results in higher export to streams even though filter strips and grassed waterways generally trap more sediment mass in future scenarios. Sediment loading rates for fields with filter strips increase from 0.24 Mg/ha/yr under historic conditions to 0.34 Mg/ha/yr under mid-century conditions in the IC model. Likewise, loads increase from 0.07 Mg/ha/yr to 0.10 Mg/ha/yr over time in LCR. TN and TP are also treated with both practices. The BMP removal efficiency for a pollutant is calculated as the percent difference in unit-area load to the stream network with and without the BMP. In the IC model, filter strips have the highest TN removal efficiency (nearly 60%) of the simulated BMPs. Model results show that filter strips also effectively trap particulate P and infiltrate dissolved P at the field’s edge, consistent with field experiments (Abu-Zreig et al., 2003). Predicted TSS, TN, and TP removal efficiencies for filter strips and grassed waterways increase slightly from historic conditions in IC when mean annual precipitation is lower and air temperatures are hotter in the late century, which reduces flow to and improves the performance of these BMPs.

Conservation tillage and no-till

The efficiency of erosion control practices, such as conservation tillage and no-till, decrease under future conditions as more intense storm events disturb even protected field soils. Simulated sediment loads for fields with conservation tillage rise through mid-century and are about twice as high in the late 21st century than the historic period for both watersheds. No-till also becomes a less efficient practice in the future; however, of the two alternative tillage practices, no-till is effective in limiting current and future TN and TP export as undisturbed soils enriched from crop residue better retain moisture and dissolved and particulate forms of pollutants, reduce field runoff, and limit erosion, as has been shown by field experiments (Wuest et al., 2004). Simulations show that the performance of these BMPs in IC and LCR is best maintained into the late-century when increases in air temperature are less extreme, regardless of whether mean annual precipitation increases or decreases.

Nutrient management

TN loads to streams are 9.1% lower (reduced to 14.8 from 16.3 kg-N/ha/yr; table 4) when nutrient management is applied in the LC model under historic conditions. Although slightly less effective, nutrient management still reduces TN pollution in the mid 21st century (TN loads reduced by 7.5% in LCR). Unlike LCR, lower application rates of synthetic fertilizers maintain its effectiveness over time in the IC model for both TN and TP across the different climate scenarios. Application of poultry manure in the IC model does not alter TN loading much, because application rates were established as a direct substitution of synthetic fertilizer. TP yields are higher on IC fields when manure is applied instead of chemical fertilizers; this is because application rates are based on crop nitrogen requirements. As a result, phosphorus application is excessive when manure is incorporated as a fertilizer, increasing TP export from fields. As indicated by the results, nutrient management is not an effective practice for reducing sediment pollution in LCR or IC as this BMP is primarily designed for nutrient load reduction.

Winter cover crops

Winter cover crops are the most efficient BMP for reducing sediment yield in the IC model, reducing export by more than 70% for all three time periods. By mid-century, winter cover crops reduce sediment loads by nearly 0.8 Mg/ha/yr in the IC model. Growing winter rye as an offseason cover crop in the LCR model is also an effective BMP for sediment pollution, and winter rye reduces sediment export by 20.8% in the historic and mid-century periods. Warmer temperatures improve winter rye growth and vitality in the late 21st century, reducing sediment yields by 23.8%. Even though there are improvements in the performance of cover crops over time due to warmer mean annual temperatures, increases in precipitation still exacerbate sediment pollution (e.g. loads increase from 0.16 to 0.30 Mg/ha/yr in IC and from 0.10 to 0.14 Mg/ha/yr in LCR). Warmer temperatures speed mineralization of fresh organic P, making cover crops less efficient at P treatment for both IC and LCR, and TP removal efficiency is most hindered under the warmest and driest predicted conditions in IC. Winter cover crops are not shown to be wholly effective in IC. Nitrogen fixed by red clover worsens TN export. In addition, fresh organic nitrogen from cover crop residue mineralizes more rapidly with warmer weather and this increases TN loading rates to 32.4 kg/ha/yr in the mid 21st century for IC. Irrigating and fertilizing winter cover crops results in even higher TN export from fields in the IC model and therefore indicates that mismanaged winter cover crops can intensify TN pollution. Changes in precipitation have the greatest impact on the irrigated and fertilized cover crop BMP in IC. This practice increases TN loads from baseline levels for all periods, and the increase is 79.8% higher in the mid-century compared to the historic scenario.

Drainage water management and saturated buffers

Drainage water management BMPs perform best at reducing TN loads in the LCR model. Saturated buffers are the most effective TN BMP for LCR and reduce TN loads by about 30% for all three time periods. TN removal efficiencies of treatment wetlands, bioreactors, and controlled drainage BMPs are reduced over time and equal 19.3%, 11.5%, and 11.4% in the mid 21st century. Saturated buffers and treatment wetlands are comprehensively effective and reduce TP export as well. In contrast, controlled drainage is shown to increase TP export in both hindcast and futurecast precipitation scenarios. Simulations show that under controlled drainage runoff, lateral flows and groundwater flows increase, while tile flow decreases. This results in an increase in runoff-associated phosphorus (both soluble and sediment bound) and in soluble phosphorus loading associated with lateral and groundwater flow, but nutrients associated with tile flow are reduced.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Future changes in air temperature and precipitation, including more intense storms, are expected across much of the U.S. (USGCRP, 2017). These changes are likely to alter physical and biological factors that control sediment and nutrient loading from agricultural lands. More intense precipitation events can increase erosion and transport from fields resulting in higher pollutant loads to edge-of-field BMPs, increase leaching through sub-surface pathways, and reduce contact time in practices that rely on filtration. BMP performance can also be altered by changes in temperature. Warmer future temperatures affect plant growth (e.g., winter cover crops grow more rapidly in LCR and better stabilize soils), increase rates of decay of surface residue, and speed the cycling of nutrients (e.g., quicker decomposition of moisture-retaining plant residue for conservation tillage). Three climate changes scenarios were applied to study the hydrologic impacts on the Skunk River watershed in South Dakota and found a significant increase in evapotranspiration and reduction in water yield (Mehan et al., 2016). Such environmental changes are likely to alter BMP performance across the country. In simulations for southern Minnesota and southern Georgia, treatment efficiencies of BMPs generally decline by mid-century in response to projected future changes in air temperature and precipitation. This trend in downgraded performance continues into the late-century. The average change in removal efficiency across BMPs (excluding irrigated and fertilized winter cover crops) from historic to late 21st century for IC was −4.8% for sediment (GCM range: −3.2% to −6.1%), −13% for TN (GCM range: −8.4% to −17%), and −2.5% for TP (GCM range: −0.31% to −5.3%). Removal efficiency was altered less for LCR, averaging −3.1% for sediment (GCM range: - 1.4% to −5.0%), −0.70% for TN (GCM range: −0.23% to −2.0%), and −0.70% for TP (GCM range: 0.25% to −1.5%) across all simulated BMPs. The relative change in mean annual temperature from historic to late-century averaged across the five GCMs was lower for IC (+4.4°C) compared to LCR (+5.9°C), yet BMP performance suffered more in IC under future weather conditions. This suggests that agricultural lands in the southern U.S. may be more vulnerable to negative changes in future BMP performance compared to the Midwest. Performance did not decrease for all BMP types. Winter cover crops in LCR, for example, performed similarly under historic and mid-century conditions, and were healthier and more effective under warmer late-century conditions, which improved sediment removal efficiency by 3.0%.

We show BMP performance to be sensitive to changes in air temperature and precipitation. In IC, simulated pollutant removal efficiencies of filter strips and grassed waterways tend to be more influenced by changes in mean annual precipitation, and higher flows and pollutant loads worsen the performance of these BMPs. Conservation tillage and no-till are more affected by air temperature; as increased air temperatures and moisture deficit hinder crop growth and limit biomass production, degrading the performance of BMPs that rely on plant residue for the protection and enhancement of soil.

If realized, increasing air temperatures and changes in precipitation patterns and intensity may exacerbate upland pollutant loading from agricultural lands to water bodies, resulting in higher background sediment and nutrient loads. Decreased BMP pollutant removal efficiency could compound pollution issues in the future. Bosch (2014) also found that BMPs become less effective (but more important) under future climate in SWAT simulations of six watersheds that drain to Lake Erie.

The combined effects of increased pollutant loading rates and reduced BMP efficiencies present a risk to the success of water quality improvement plans. For example, in LCR saturated buffers for artificially drained fields might be implemented to achieve a 30% N reduction target (11.3 kg/ha/yr) under historic conditions. Simulations suggest that TN loads without BMPs could increase from 16.3 to 23.3 kg/ha/yr by mid-century in LCR. Saturated buffers bring the yield in mid-century down to 16.6 kg/ha/yr, but are not able to fully offset the increases associated with changes in air temperature and precipitation. To fully offset the increase, saturated buffers would need to be paired with other complementary BMPs, such as winter cover crops or treatment wetlands. Treatment areas could also be expanded for some BMPs to compensate for increased precipitation volumes. For instance, if 10% of 100 ha of cropland in IC utilized filter strips and the other 90% did not employ a BMP then the simulated combined TP load is 31.2 kg/yr (10 ha x 0.15 kg/ha/yr + 90 ha x 0.33 kg/ha/yr) under historic conditions. Based on mid-century simulations, at least 68% of cropland would require filter strips to achieve the same TP load (68 ha x 0.23 kg/ha/yr + 32 ha x 0.48 kg/ha/yr = 31.0 kg/yr). Renkenberger et al. (2018) present similar findings for the Greensboro watershed in Maryland. They simulated BMP implementation schemes that were optimized under current climate at the watershed-scale and showed that these were insufficient for meeting TMDL objectives under future climate. Implementation plans will likely require wider spatial extent, resizing, and/or combining practices to satisfy goals for agricultural lands. For example, a comprehensive BMP strategy may reduce the use of synthetic fertilizers and implement no-till and winter cover crops to enrich soils for cash crop production. These non-structural BMPs offer flexibility and are particularly advantageous. For example, the species grown as a winter cover crop can be adapted from year to year in response to changes in local climate. Appropriately timing fertilizer application is important as well and fall application resulted in minimum TN and TP reductions in the Lincoln Lake watershed in Arkansas and Oklahoma (Chaubey et al., 2010). Critical pollutant source areas should also be identified and targeted because strategizing conservation practices in these areas been shown to provide the same water quality protection as widespread implementation in the Susquehanna River Basin (Wagena & Easton, 2018). High pollutant loading areas, such as fine sediment fields conventionally tilled and subject to erosion, should be prioritized for BMP implementation to optimize the water quality benefits achieved with available funding.

The results of this study are conditional and dependent on the methods and model applied. By design, SWAT uses semi-empirical models to calculate runoff, sediment, and nutrient reductions of filter strips and grassed waterways, all of which are completely removed from the system. Contaminants that infiltrate from BMPs may reach streams via subsurface pathways, but this is not represented in SWAT. Legume cover crops fix nitrogen and increase N export in the IC model. Other studies report similar results. N leaching was higher for cover crops compared to fallow soils under high intensity rainfall events in pot experiments (Wang et al., 2011). However, this may be misleading because synthetic fertilizer requirements are lower when cover crops are grown (Ebelhar et al., 1984) and N leaching has been shown to be reduced by 40% when reduced fertilizer application was paired with legume cover crops (Tonitto et al., 2006). Fertilizer application rates were not reduced here to isolate the impacts of this BMP. Examining the joint performance of complementary BMPs (e.g. cover crops and nutrient management) under future conditions is an area for additional research.

In sum, agricultural BMPs examined in this paper will continue to be an important part of strategies for reducing agricultural pollution. The selection of BMPs for meeting water quality management targets must consider factors such as economic efficiency, feasibility, regulatory setting, and other factors. Our simulations indicate that BMP selection should also consider sensitivity of BMP performance to future changes in air temperature and precipitation.

Figure 3.

Best Management Practice (BMP) removal efficiencies for the Ichawaynochaway Creek (IC) and Little Cobb River (LCR) SWAT watershed models. Removal efficiencies shown for Sediment, Total Phosphorus, and Total Nitrogen averaged across scenarios for historic, mid-century, and late-century periods. BMPs include conservation tillage (CT), no-till (NT), filter strips (FS), grassed waterways (GW), poultry manure (PM), nutrient management (NM), cover crops (CC with fertilization (f) or irrigation (i) practices), controlled drainage (CD), bioretention (BR), saturated buffers (SB), and treatment wetlands (TW). Negative removal efficiencies indicate pollutant loading increases with BMP application.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The dataset MACAv2-METDATA was produced with funding from the Regional Approaches to Climate Change (REACCH) project and the SouthEast Climate Science Center (SECSC). We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme’s Working Group on Coupled Modeling, which is responsible for CMIP5, and we thank these modeling groups for producing and making available their model output. For CMIP5, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison provides coordinating support and led development of software infrastructure in partnership with the Global Organization for Earth System Science Portals. The views expressed in this paper represent those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

REFERENCES

- Abatzoglous JT (2013) Development of gridded surface meteorological data for ecological applications and modelling. Int. J. Climatol,, 33(1), 121–131. 10.1002/joc.3423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abatzoglou JT, & Brown TJ (2012). A comparison of statistical downscaling methods suited for wildfire applications. Int. J. Climatol, 32(5), 772–780. 10.1002/joc.2312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Zreig M, Rudra RP, Whiteley HR, Lalonde MN, & Kaushik NK (2003). Phosphorus removal in vegetated filter strips. J. Environ. Qual, 32(2), 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AESL (Agricultural & Environmental Services Laboratories). (2017). Crop code sheets: Fertilizer recommendations by crops. University of Georgia College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences. Athens, GA. Retrieved from http://aesl.ces.uga.edu/publications/soil/CropSheets.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Arabi M, Frankenberger JR, Engel BA, & Arnold JG (2007). Representation of agricultural conservation practices with SWAT. Hydrol. Process, 22(16), 3042–3055. 10.1002/hyp.6890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold JG, Srinivasan R, Muttiah RS, & Allen PM (1998). Large area hydrologic modeling and assessment, Part I: Model development. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc, 34, 73–89. 10.1111/j.1752-1688.1998.tb05961.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad MA, Schnitzer M, Angers DA &Ripmeester JA (1990). Effects of till vs no-till on the quality of soil organic matter. Soil Bio. Biochem, 22(5), 595–599. 10.1016/0038-0717(90)90003-I [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin KR, & Creamer NG (2016). Cover crops for organic farms. Center for Environmental Farming Systems. Retrieved from https://cefs.ncsu.edu/resources/cover-crops-for-organic-farms/ [Google Scholar]

- Benham BL, Vaughan DH, Laird MK, Ross BB, & Peek DR (2007). Surface water quality impacts of conservation tillage practices on burley tobacco production systems in southwest Virginia. Water Air Soil Pollut, 179(1–4), 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman PM, Rosen CJ, Venterea RT, & Lamb JA (2012). Survey of nitrogen fertilizer use on corn in Minnesota. Agric. Syst, 109, 43–52. 10.1016/j.agsy.2012.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boles CMW, Frankenberger JR, & Moriasi DN (2015). Tile drainage simulation in SWAT2012: Parameterization and evaluation in an Indiana watershed. Trans. ASABE, 58(5), 1201–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch NA, Evans MA, Scavia D, & Allan JD (2014). Interacting effects of climate change and agricultural BMPs on nutrient runoff entering Lake Erie. J. Great Lakes Res, 40(3), 581–589. 10.1016/j.jglr.2014.04.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter SR, Caraco NF, Correll DL, Howarth RW, Sharpley AN, & Smith VH (1998). Nonpoint pollution of surface waters with phosphorus and nitrogen. Ecol. Applic, 8(3), 559–568. 10.1890/1051-0761(1998)008[0559:NPOSWW]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaubey I, Chiang L, Gitau MW, & Mohamed S. (2010). Effectiveness of best management practices in improving water quality in a pasture-dominated watershed. J. .Soil .Water Conserv, 65(6), 425–437. doi: 10.2489/jswc.65.6.424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J, Lowrance RR, Bosch DD, Strickland TC, Her Y, & Vellidis G. (2010). Effect of watershed subdivision and filter width on SWAT simulation of a coastal plain watershed. J. Am. Water Resourc. Assoc, 46(3), 586–600. 10.1111/j.1752-1688.2010.00436.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J, Her Y, & Bosch D. (2016). Sensitivity of simulated conservation practice effectiveness to representation of field and in-stream processes in the Little River watershed. Environ. Model Assess, 22(2), 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Daly C, Halbleib M, Smith JI, Gibson WP, Doggett MK, Taylor GH, Curtis J, & Pasteris PP (2008). Physiographically sensitive mapping of climatological temperature and precipitation across the conterminous United States. Int. J. Climatol, 28(15), 2031–2064. 10.1002/joc.1688 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorioz JM, Want D, Poulenard J, & Trévisan D. (2006). The effect of grass buffer strips on phosphorus dynamics – A critical review and synthesis as a basis for application in agricultural landscapes in France. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ, 117(1), 4–21. 10.1016/j.agee.2006.03.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Easterling WE, Rosenberg NJ, McKenney MS, Jones CA, Dyke PT, & Williams JR (1992). Preparing the erosion productivity impact calculator (EPIC) model to simulate crop response to climate change and the direct effects of CO2. Agric. For. Meteorol, 59(1–2), 17–34. 10.1016/0168-1923(92)90084-H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebelhar SA, Frye WW, & Blevins RL (1984). Nitrogen from Legume Cover Crops for No-Tillage Corn. Agron. J, 76(1), 51–55. doi: 10.2134/agronj1984.00021962007600010014x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). (2017). Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Watershed Nutrient Task Force, 2017 report to Congress. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-11/documents/hypoxia_task_force_report_to_congress_2017_final.pdf

- Feyereisen GW, Strickland TC, Bosch DD, Truman CC, Sheridan JM, & Potter TL (2008). Curve number estimates for conventional and conservation tillages in the southeastern Coastal Plain. J. Soil Water Conserv, 63(3),120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Folle SM (2010a). SWAT modeling of sediment, nutrients and pesticides in the Le Sueur River Watershed, South-Central Minnesota. Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. Retrieved from http://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/59212/Folle_umn_0130E_10935.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Folle S, Dalzell B, & Mulla D. (2010b). Evaluation of best management practices (BMPs) in impaired watersheds using the SWAT Model. Minnesota Dept. of Agriculture. Retrieved from http://www.mda.state.mn.us/protecting/cleanwater/research/~/media/Files/protecting/cwf/swatmodel.ashx [Google Scholar]

- Franks PJ, & Beerling DJ (2009). Maximum leaf conductance driven by CO2 effects on stomatal size and density over geologic time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA,106(25), 10343–10347. 10.1073/pnas.0904209106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbrecht JD, Nearing MA, Shields FD Jr., Tomer MD, Sadler EJ, Bonta JV, & Baffaut C. (2014). Impact of weather and climate scenarios on conservation assessment outcomes. J. Soil Water Conserv, 69(5), 374–392. doi: 10.2489/jswc.69.5.374 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- GCE (Georgia Cooperative Extension). (2008). Soil Test Handbook for Georgia. University of Georgia, College of Agricultural and Environmental Services. Retrieved from http://aesl.ces.uga.edu/publications/soil/STHandbook.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gitau MW, Gburek WJ, & Bishop PL (2008). Use of the SWAT Model to Quantify Water Quality Effects of Agricultural BMPs at the Farm-Scale Level. Trans. ASABE, 51(6), 1925–1936. [Google Scholar]

- GSWCC (Georgia Soil and Water Conservation Commission). (2013). Best management practices for Georgia agriculture: conservation practices to protect surface water quality, second edition. Retrieved from https://gaswcc.georgia.gov/best-management-practices-georgia-agriculture

- Hancock DW (2014). Rye. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. Athens, GA. Retrieved from http://georgiaforages.caes.uga.edu/species/documents/Rye.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hook JE, Harrison KA, & Hoogenboom G. (2005). Ag water pumping: Statewide irrigation monitoring. University of Georgia, Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences. UGA: ID 25–21-RF327–107. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth RW, Sharpley A, & Walker D. (2002). Sources of nutrient pollution to coastal waters in the United States: Implications for achieving coastal water quality goals. Estuaries, 25(4b), 656–676. [Google Scholar]

- Hui W, Yongbo L, Junzhi L, & Xing ZA (2014). Representation of agricultural best management practices in a fully distributed hydrologic model: A case study in the Luoyugou watershed. J. Resour. Ecol, 5(2), 179–184. DOI: 10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2014.02.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). (2013). Annex II: Climate System Scenario Tables [Prather M, Flato G, Friedlingstein P, Jones C, Lamarque J-F, Liao H.and Rasch P.(eds.)]. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner G-K, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V. and Midgley PM(eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). (2014). Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, Pachauri RK and Meyer LA (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Lammertsma EI, de Boer HJ, Dekker SC, Dilcher DL, Lotter AF, & Wagner-Cremer F. (2011). Global CO2 rise leads to reduced maximum stomatal conductance in Florida vegetation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108(10), 4035–4040. 10.1073/pnas.1100371108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Gaskin J, Schomberg H, Hawkins G, Harris G, & Bellows B. (2008). Success with cover crops. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. Athens, GA. Retrieved from http://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.cfm?number=EB102 [Google Scholar]

- Leung LR, & Wigmosta MS (1999). Potential climate change impacts on mountain watersheds in the Pacific Northwest. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc, 35(6), 1463–1471. 10.1111/j.1752-1688.1999.tb04230.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Yang W, Qin C, & Zhu A. (2016). A review and discussion on modeling and assessing agricultural best management practices under global climate change. J. of Sustain. Devel, 9(1), 245–255. 10.5539/jsd.v9n1p245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MDA (Minnesota Department of Agriculture). (2017). Conservation practices, Minnesota conservation funding guide. Saint Paul, MN. Retrieved from http://www.mda.state.mn.us/protecting/conservation/practices/covercrops.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Meinshausen M, Smith SJ, Calvin K, Daniel JS, Kainuma MLT, Lamarque JF, Matsumoto K, Montzka SA, Raper SCB, Riahi K, Thomson A, Velders GJM, & van Vuuren DPP (2010). The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions from 1765 to 2300. Clim. Change, 109, 213–241. 10.1007/s10584-011-0156-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehan S, Kannan N, Neupane RP, McDaniel R, & Kumar S. (2016). Climate Change Impacts on the Hydrological Processes of a Small Agricultural Watershed. Climate, 4(4), 56. 10.3390/cli4040056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak AM, Anderson EJ, Beletsky D, Boland S, Bosch NS, Bridgeman TB, … Zagorski MA (2013). Record-setting algal bloom in Lake Erie caused by agricultural and meteorological trends consistent with expected future conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 110(16)6448–6452. 10.1073/pnas.1216006110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KE, Luhmann D, Houser PR, Wood EF, Schaake JC, Robock A, … Bailey AA (2004). The multi-institution North American Land Data Assimilation System (NLDAS): Utilizing multiple GCIP products and partners in a continental distributed hydrological modeling system. J. Geophys. Res, 109(D7), D07S90. 10.1029/2003JD003823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moriasi DN, Arnold JG, Van Liew MW, Bingner RL, Harmel RD, & Veith TL (2007). Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. Trans. ASABE, 50(3) 885–900. doi: 10.13031/2013.23153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moriasi DN, Gowda PH, Arnold JG, Mulla DJ, Ale S, Steiner JL, & Tomer MD (2013). Evaluation of the Hooghoudt and Kirkham tile drain equations in the Soil and Water Assessment Tool to simulate tile flow and nitrate-nitrogen. J. Environ. Qual, 42(6), 1699–1710. 10.2134/jeq2013.01.0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morison JIL, & Gifford RM (1983). Stomatal sensitivity to carbon dioxide and humidity. Plant Physiol, 71, 789–796. 10.1104/pp.71.4.789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motsinger J, Kalita P, & Bhattarai R. (2016). Analysis of best management practices implementation on water quality using the Soil and Water Assessment Tool. Water, 8(4), 145. 10.3390/w8040145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch PS, Baron JS, & Miller TL (2000). Potential effects of climate change on surface water quality in North America . J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc, 36, 347–366. 10.1111/j.1752-1688.2000.tb04273.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neitsch SL, Arnold JG, Kiniry JR, & Williams JR (2011). Soil and Water Assessment Tool, theoretical documentation, version 2009. TR-406. Texas Water Resources Institute, College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- NASS (National Agricultural Statistics Service). (2008–2014). Cropland data layer. United States Department of Agriculture, Retrieved from https://www.nass.usda.gov/Research_and_Science/Cropland/Release/index.php

- Rabalais NN, Turner RE, & Wiseman WJ (2002). Gulf of Mexico hypoxia, a.k.a. “the dead zone”. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst, 33, 235–263. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randall G, Schmitt M, Strock J, & Lamb J. (2017). Validating N rates for corn on farm fields in southern Minnesota. University of Minnesota Extension. Retrieved from https://www.extension.umn.edu/agriculture/nutrient-management/nitrogen/validating-n-rates-for-corn-on-farm-fields-in-southern-minnesota/ [Google Scholar]

- Renkenberger J, Montas H, Leisnham P, Chanse V, Shirmohammadi A, Sadeghi A, … Lansing D. (2018). Effectiveness of Best Management Practices with Changing Climate in a Maryland Watershed. Trans. ASABE, 60:769–782, doi: 10.13031/trans.11691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riahi K, Rao S, Krey V, Cho C, Chirkov V, Fischer G, … Rafaj P. (2011). RCP 8.5 – A scenario of comparatively high greenhouse gas emissions. Clim. Change, 109, 33–57. 10.1007/s10584-011-0149-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz CW, & Merka WC 2016. Maximizing poultry manure use through nutrient management planning (B 1245). University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. Athens, GA. Retrieved from http://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.cfm?number=B1245 [Google Scholar]

- Sinha E, Michalak AM, & Balaji V. (2017). Eutrophication will increase during the 21st century as a result of precipitation changes. Science, 357(6349), 405–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soileau JM, Touchton JT, Hajek BF , & Yoo KH (1994). Sediment, nitrogen, and phosphorus runoff with conventional- and conservation-tillage cotton in a small watershed. J. Soil Water Conserv, 49, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Tonitto C, David MB, & Drinkwater LE (2006). Replacing bar fallows with cover crops in fertilizer – intensive cropping systems: A meta-analysis of crop yield and N dynamics. Agric., Sust., Environ, 112(1), 58–72. 10.1016/j.agee.2005.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomer MD, & Schilling KE (2009). A simple approach to distinguish land-use and climate-change effects on watershed hydrology. J. of Hydrol, 376, 24–33. 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.07.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tuppad P, Kannan N, Srinivasan R, Rossi CG, & Arnold JG (2009). Simulation of agricultural management alternatives for watershed protection. Water Resour. Manag, 24(12), 3115–3144. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich A, & Volk M. (2009). Application of the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) to predict the impact of alternative management practices on water quality and quantity. Agri. Water Manage, 96(8), 1207–1217. 10.1016/j.agwat.2009.03.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). (2002). 2002 census of agriculture. Retrieved from http://www.agcensus.usda.gov

- USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). (2007). 2007 census of agriculture. Retrieved from http://www.agcensus.usda.gov

- USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). (2012). 2012 census of agriculture. Retrieved from http://www.agcensus.usda.gov

- USGCRP. (2017). Climate science special report: Fourth national climate assessment, Volume I [Wuebbles DJ, Fahey DW, Hibbard KA, Dokken DJ, Stewart BC, and Maycock TK (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, 470 pp, doi: 10.7930/J0J964J6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waidler D, White E, Steglich E, Wang S, Williams J, & Srinivasan R. (2009). Conservation practice modeling guide for SWAT and APEX. Retrieved from http://swat.tamu.edu/media/57882/conservation_practice_modeling_guide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wagena MB, & Easton ZM (2018). Agricultural conservation practices can help mitigate the impact of climate change. Sci. Total Environ, 635, 132–143. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Li Y, Klassen W, & Alva A. (2011). High retention of N P nutrients, soil organic carbon, and fine particles by cover crops under tropical climate. Agro. Sustain. Devel, 32(3), 781–790. [Google Scholar]

- Watershed Evaluation Group, University of Guelph. (2017). SWAT Modelling and Assessment of Agricultural BMPs in the Gully Creek Watershed. Retrieved from http://www.abca.on.ca/downloads/2017_GLASI_SWAT_Modelling_Report_Gully_Creek_Watershed_Web_RE.pdf

- White M, Harmel D, Yen H, Arnold J, Gambone M, & Haney R. (2015). Development of sediment and nutrient coefficients for the U.S. ecoregions. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc, 51(3), 758–775. 10.1111/jawr.12270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JD, & Wuest SB (2011). Tillage and no-tillage conservation effectiveness in the intermediate precipitation zone of the inland Pacific Northwest, United States. J. Soil Water Conserv, 66(4), 242–249. doi: 10.2489/jswc.66.4.242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woznicki SA, Nejadhashemi AP, & Smith CM (2011). Assessing best management practice implementation strategies under climate change scenarios. Trans. ASABE, 54(1), 171–190. doi: 10.13031/2013.36272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woznicki SA, & Nejadhashemi AP (2012). Sensitivity analysis of best management practices under climate change scenarios. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc, 48(1), 90–112. 10.1111/j.1752-1688.2011.00598.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest SB, Williams JD, Gollany HT, Siemens MC, & Long DS (2004). Comparison of runoff and soil erosion from no-till and inversion tillage production systems. Retrieved from http://www.ars.usda.gov/sp2UserFiles/person/6233/comparisonOfRunoffAndSoil_2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y, Locke MA, & Binger RL (2008). Annualized agricultural non-point source model application for Mississippi Delta Beasley Lake watershed conservation practices assessment. J. .Soil .Water Conserv., 63(6), 542–551. doi: 10.2489/jswc.63.6.542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]