Abstract

The rate of multiple-antibiotic resistance is increasing among Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strains in Southeast Asia. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and other typing methods were used to analyze drug-resistant and -susceptible organisms isolated from patients with typhoid fever in several districts in southern Vietnam. Multiple PFGE and phage typing patterns were detected, although individual patients were infected with strains of a single type. The PFGE patterns were stable when the S. enterica serovar Typhi strains were passaged many times in vitro on laboratory medium. Paired S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates recovered from the blood and bone marrow of individual patients exhibited similar PFGE patterns. Typing of S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates from patients with relapses of typhoid indicated that the majority of relapses were caused by the same S. enterica serovar Typhi strain that was isolated during the initial infection. However, some individuals were infected with distinct and presumably newly acquired S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates.

Infections with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi continue to be a major problem in developing countries, causing typhoid in over 10 million people and an estimated 600,000 deaths per year (12, 25). S. enterica serovar Typhi naturally infects only humans and is a well-adapted bacterial parasite with the ability to invade, persist, and, in some individuals, establish a chronic carrier state with persistent excretion of the organism for months or years (43). Typhoid may also resolve and then later relapse with recrudescence of clinical disease (4, 11, 19, 20). Relapse can occur without a history of clinical intervention but more often follows antibiotic treatment. The incidence of relapse following treatment with new antibacterial drugs, including fluoroquinolones (1.5%) or broad-spectrum cephalosporins (5%), is much lower than that normally observed after treatment with traditional antibiotics (chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ampicillin) (1, 2, 7, 24, 31, 41–43). Resistance to the conventional antibiotics is usually associated with the acquisition of an incompatibility group HI plasmid, which can encode simultaneously resistance to chloramphenicol, ampicillin, trimethoprim, sulfonamides, and tetracyclines (3, 6, 26, 27). More recently, S. enterica serovar Typhi has been reported to have acquired quinolone resistance, which is associated with chromosomal point mutations in the gyrA gene (40). At the Centre for Tropical Diseases in Ho Chi Minh City, a referral center in southern Vietnam, over 80% of the S. enterica serovar Typhi organisms that cause infections are now resistant to quinolones, and full fluoroquinolone resistance is likely to appear under continued selection pressure in the near future. The rapid emergence and spread of these resistant organisms, particularly in Vietnam (31, 39, 42), southern India (29), and Tajikistan (21), and their continued selection under antibiotic pressure raises the scenario of the reemergence of untreatable typhoid.

The phenomenon of relapse could result from recrudescence of bacteria that lie quiescent within host tissues, reinfection with the same strain, or infection with a different strain. Although simple methods, such as comparison of antibiotic sensitivity patterns, may give some clues to the identities of the organisms, the organisms are not always susceptible to antibiotics. The development of novel molecular typing methods allows a more precise distinction between S. enterica serovar Typhi strains in general and between relapse and reinfection in particular. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), in which the electrophoretic patterns of large DNA fragments are analyzed on gels following restriction enzyme cleavage, is particularly valuable. The restriction enzyme I-CeuI, which cleaves within the S. enterica serovar Typhi rRNA genes, together with other rarely cutting restriction endonucleases, including BlnI and XbaI, have been used to create a physical map of the S. enterica serovar Typhi genome (5, 8, 10, 18, 22, 30, 33–38). This has demonstrated that S. enterica serovar Typhi has a remarkably plastic genome compared to the genomes of other enteric bacteria (9, 14–17, 23, 32). Plasticity may be, in part, a consequence of homologous recombination between different rRNA operons. In this study we have used PFGE, together with phage typing, plasmid profiling, and ribotyping, to distinguish recrudescence from reinfection in a region where multiple-drug-resistant typhoid fever is endemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

The patients in this study (964 in total) were part of ongoing treatment studies reported elsewhere (43) and were admitted to one of three hospitals in southern Vietnam: the Centre for Tropical Diseases, an infectious disease referral hospital, Dong Nai Provincial Paediatric Hospital, and Dong Thap Provincial Hospital. The following relapse patients (RR) have been studied previously: RR1 (31); RR2 (39); RR3, RR4, and RR5 (40–42); and RR6, RR7, RR8, and RR9 (43). Patients RR10, RR11, and RR12 were recent patients who had not been examined for a previously published study.

On admission, the clinical history and examination findings were recorded on a standard form. Before treatment was started, blood, bone marrow (for those patients with a clear history of preadmission antibiotic use), and up to three stool specimens were collected for culture. For the investigation of the stability of PFGE patterns in vivo, bone marrow and blood were collected from five patients admitted to the Dong Thap Provincial Hospital. Patients were treated either as part of ongoing studies described elsewhere (40, 41) or at the discretion of the treating physician. These studies were approved by the Ethical and Scientific Committee of the Centre for Tropical Diseases, and all patients gave informed consent prior to recruitment.

Laboratory diagnostic methods.

The diagnosis of typhoid fever was made by isolation of S. enterica serovar Typhi from blood or bone marrow by standard methods. A total of 5 to 10 ml of blood was drawn aseptically from each patient and was inoculated into 50 ml of brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) containing 0.05% sodium polyanetholesulfonate (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom). A minimum blood-to-broth ratio of 1 to 10 was maintained. Blood culture broths were incubated for 7 days, and subcultures were performed at 24 h and after 7 days. All bottles were examined daily, and if the bottle showed visible signs of growth, subculture onto sheep blood agar was performed. All S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates were identified with urease agar slopes, citrate agar slopes, and Kligler iron agar slants (Oxoid) and by agglutination with antisera specific for O9 and Vi antigens (Murex, Dartford, United Kingdom). The antibiotic disc method for determination of sensitivities was performed by a modified Bauer-Kirby method. Organisms resistant to chloramphenicol, ampicillin, trimethoprim, and sulfamethoxazole but susceptible to ofloxacin and ceftriaxone were described as multiple-drug resistant. Isolates were stored and transported on Protect beads (Prolabs, Oxford, United Kingdom) and were stored at −18°C.

Stability of PFGE patterns following passage of S. enterica serovar Typhi on laboratory media.

In order to evaluate the potential of PFGE for epidemiological typing and, in particular, to distinguish relapses from newly acquired infections, the stabilities of the PFGE patterns of six S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates obtained from patients who had typhoid fever and who had been admitted to the Centre for Tropical Diseases and entered into treatment trials of fluoroquinolones or cephalosporins (43) were determined by subculture of the strains 17 times by standard methods. The subcultures were done at 24-h intervals (except on Sundays and bank holidays). This took 27 days to complete. The bacteria were then frozen at −40°C, shipped on dry ice, and kept frozen until they were processed for PFGE.

Analysis of PFGE patterns of multiple S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates from the same patient.

To assess the stability of the PFGE patterns of the S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates from typhoid patients in vivo and to investigate the possibility of infection with multiple S. enterica serovar Typhi strains, at least 10 separate isolates from the blood and 10 separate isolates from the bone marrow of five different patients admitted to the Dong Thap Provincial Hospital were examined. These patients were originally included in a study into the quantitative bacteriology of typhoid fever (41). Multiple clonal isolates were collected, as follows: aliquots of 1 ml of blood or 0.5 ml of bone marrow from each patient were mixed with 19 ml of molten (50°C) Columbia agar (Oxoid) containing 0.05% sodium polyanetholesulfonate in sterile petri dishes. After being allowed to set, all plates were incubated at 37°C overnight. Ten colonies were collected from the plates without further culture by using a wide-bore sterile plastic pastette to take a core of agar in which the bacterial colony was incorporated. These cores were then frozen in separate sterile containers and were stored at −18°C for subsequent whole-chromosome digestion.

Comparison of digests of DNA of paired S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates from patients with relapses.

Pairs of S. enterica serovar Typhi strains were obtained from 10 patients during the acute and relapse phases of typhoid (Table 1). These patients had been admitted to any one of the three hospitals described above with culture-positive typhoid fever and were then readmitted to the same hospital with culture-positive typhoid fever.

TABLE 1.

Clinical features associated with patients who had typhoid relapses and who provided S. enterica serovar Typhi samples for the study

| Strain designationa | Treatment | Duration of treatment (days) | Complication | Fever clearance time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR1-A | Ceftriaxone | 3 | None | 162 |

| RR1-R | Ofloxacin | 5 | None | 100 |

| RR2-A | Ofloxacin | 3 | None | 90 |

| RR2-R | Ofloxacin | 7 | None | Unknown |

| RR3-A | Ofloxacin | 3 | Gastrointestinal bleeding | 114 |

| RR3-R | Ofloxacin | 10 | None | 114 |

| RR4-A | Ofloxacin | 2 | None | 72 |

| RR4-R | Ofloxacin | 7 | None | 72 |

| RR5-A | Cefixime | 7 | None | 180 |

| RR5-R | Ofloxacin | 20 | None | 150 |

| RR6-A | Ofloxacin | 7 | None | Unknown |

| RR6-R | Ofloxacin | 20 | Severe | 168 |

| RR7-A | Ofloxacin | 7 | None | 180 |

| RR7-R | Ofloxacin | 6 | None | 96 |

| RR8-A | Ofloxacin | 8 | None | 140 |

| RR8-R | Ofloxacin | 3 | None | 68 |

| RR9-A | Ofloxacin | 24 | None | Unknown |

| RR9-R | Ofloxacin | 5 | None | 60 |

| RR10-A | Ofloxacin | 7 | None | 112 |

| RR10-R | Ofloxacin | 5 | None | 56 |

A, strain from acute phase sample; R, strain from relapse-phase sample.

PFGE.

To characterize the S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates included in this study, PFGE of restriction enzyme-cleaved genomic DNA was performed for strain typing. The restriction enzymes XbaI and BlnI (Boehringer Mannheim, Lewes, United Kingdom) and the intron-encoded enzyme I-CeuI (New England Biolabs, Hitchin, United Kingdom) were selected because these enzymes had previously been used to type S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates (18). DNA was prepared from isolates cultured from frozen beads or agar cores onto nutrient agar (Oxoid) by the method of Liu et al. (14). PFGE of chromosomal fragments was carried out in gels of 1% agarose (Boehringer) at 6 V/cm in 0.5× Tris-borate buffer (0.045 M Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) at 4°C with a Bio-Rad (Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom) CHEF-DR II apparatus. The following conditions were used: (i) for long gels (gel size, 13 by 20 cm; XbaI and BlnI cleavages), pulse times were ramped from 10 to 50 s over 12 h, then 20 to 35 s over 8 h, then 10 to 15 s over 8 h, and finally, 2 to 10 s over 8 h; and (ii) for standard gels (gel size, 13 by 14 cm; I-CeuI cleavages), pulse times were ramped from 50 to 80 s over 17 h and then 2 to 12 s for 6 h. The gels were then stained with ethidium bromide to visualize the DNA. Images were captured with an image analyzer for computer analysis. The similarities of the fragment length patterns were scored with the Jaccard coefficient, and the relationships between strains were compared by the unweighted pair-group average method to produce a dendrogram (32).

Phage typing and ribotyping.

Phage typing was performed by the Department of Enteric Pathogens, Central Public Health Laboratory, London, United Kingdom. For ribotyping, genomic DNA (1 to 2 mg) was cleaved with PstI (Boehringer Mannheim), separated by standard gel electrophoresis, denatured, and transferred to nylon membranes (Hybond N+; Amersham, Amersham, United Kingdom) (28). Hybridization analysis was carried out with a 400-bp probe that hybridizes within the rRNA operons of S. enterica serovar Typhi. The probe was labelled with an enhanced chemiluminescence nonradioactive detection kit (Amersham) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Hybridization was carried out at 65°C overnight, and the products were washed by the protocol provided with the kit.

Plasmid preparation and replicon typing.

Plasmids were isolated from the S. enterica serovar Typhi strains by the method of Kado and Liu (13). Each preparation was retested four times to ensure reproducibility. Plasmids from Escherichia coli of known size (kindly supplied by Hilary Richards, University College London, London, United Kingdom) were used as size markers. The isolated plasmids were examined by PFGE under the following conditions: 1% agarose gels in 0.5× Tris-borate buffer at 6 V/cm at 4°C with pulse times ramped from 50 to 80 s for 8 h and then 3 to 12 s for 3 h. The gels were then stained with ethidium bromide.

Replicon typing was used to confirm the presence of incompatibility group HI plasmids in the isolates from patients with relapses. Hybridization with specific DNA probes, which contain the genes involved in plasmid maintenance, was carried out by the method of Couturier et al. (3). The probe was prepared from plasmid pULB2434 containing a 7-kbp EcoRI fragment from the IncHI1 plasmid TR6 cloned in pBR322 (supplied by Katja Hill, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom [originally from Martine Couturier, University of Brussels, Brussels, Belgium]). The 2.25-kbp DNA fragment that was released by cleavage with EcoRI and HindIII (both enzymes were from Boehringer Mannheim) and that was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis was excised from the gel and was purified with a Bio-Rad Prep-a Gene kit. Southern blotting of the plasmids from the pulsed-field gel to nylon (Hybond N+; Amersham) was carried out by a standard procedure (28). The probe DNA was labelled with [α-32P]dATP by using the Megaprime labelling kit (Amersham). Hybridization was carried out at 50°C overnight, and the products were washed by the protocol from the Megaprime kit.

RESULTS

Stability of PFGE patterns following passage of S. enterica serovar Typhi on laboratory media.

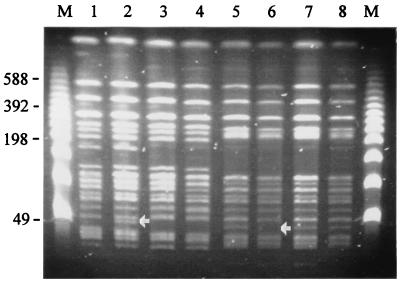

Of the six independent S. enterica serovar Typhi clinical isolates investigated (isolates TY38, TY39, TY51, TY57, TY61, TY81), all had different and distinct PFGE patterns. There were no detectable differences in the I-CeuI cleavage patterns of any isolate after 17 passages, showing that rearrangements due to recombination events between different rRNA operons were not a frequent occurrence. When DNAs prepared from the same passaged strains were analyzed by PFGE following cleavage of the DNA with either BlnI or XbaI, very conserved patterns were observed. In many cases the patterns were identical, but in a few instances minor differences in banding patterns were observed. The PFGE patterns following BlnI cleavage of four passaged isolates are shown in Fig. 1. The BlnI cleavage patterns of TY39 and TY57 were indistinguishable, whereas TY38 and TY51 had changes in single DNA fragments (arrows in Fig. 1). Thus, the PFGE cleavage patterns were relatively conserved following extensive in vitro passage.

FIG. 1.

PFGE cleavage patterns of S. enterica serovar Typhi DNAs prepared from isolates TY38, TY39, TY51, and TY57 following cleavage with BlnI and after passage of the strains on laboratory media. Lanes 1 and 2, TY38 after 0 and 17 subcultures, respectively; lanes 3 and 4, TY39 after 0 and 17 subcultures, respectively; lanes 5 and 6, TY51 after 0 and 17 subcultures, respectively; and lanes 7 and 8, TY57 after 0 and 17 subcultures, respectively. See Materials and Methods for subculture conditions. Arrows point out differences in the DNA fragment band patterns in lane 2 and lane 6. Lanes M, bacteriophage lambda concatamer molecular size markers, with the sizes of the DNA fragments (in kilobase pairs) indicated to the left of the figure.

Analysis of PFGE patterns of multiple S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates from the same patient.

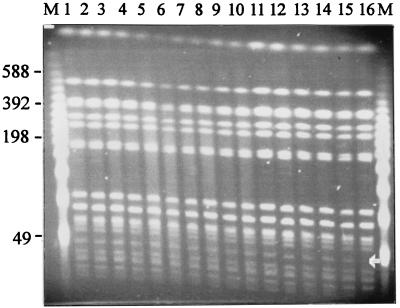

Figure 2 shows the PFGE patterns obtained following cleavage with XbaI of the genomic DNAs from 16 isolates collected with minimal subculture from the bone marrow of a single patient. All other samples gave broadly similar results (data not shown). Of the 16 isolates obtained from bone marrow, 1 was missing a DNA fragment of approximately 50 kbp. This was associated with the loss of the antibiotic resistance plasmid, as confirmed by sensitivity testing and plasmid profiling. Again, the PFGE patterns of the S. enterica serovar Typhi strains isolated during infection are very stable, and multiple bacterial infections in the same patient were not detected.

FIG. 2.

Pulsed-field gel showing the XbaI cleavage patterns of genomic DNA prepared from S. enterica serovar Typhi isolated from the bone marrow of an individual typhoid patient. Similar results were obtained with blood from the same patient at several time points during the infection. Lanes 1 to 16, PFGE patterns for 16 different S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates, respectively; arrow, difference in DNA fragment band pattern (lane 16); lanes M, bacteriophage lambda concatamer molecular size marker, with the sizes of the DNA fragments (in kilobase pairs) indicated to the left of the figure.

Comparison of digests of DNA of paired S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates from patients with relapses.

Pairs of S. enterica serovar Typhi strains were obtained from patients during the acute and relapse phases of typhoid. The median age of the patients suffering from typhoid relapses in this study was 14 years (range, 3 to 33 years). The average afebrile period between the resolution of the first typhoid episode and the beginning of the second episode was 22 days (range 8 to 40 days). Two patients had afebrile periods of nearly 6 weeks (39 and 40 days). Eight patients had been treated with a short (2- to 7-day) course of ofloxacin, and the S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates from two patients were nalidixic acid resistant and had reduced susceptibility to ofloxacin. In most patients the relapse was less severe than the initial episode, although in one patient it was more severe. The response to therapy in the initial attack was usually slower than that in the relapse; the median time to fever clearance of 4.8 days (range, 3 to 7.5 days) in the first episode was less than that of 3.4 days (range, 2.3 to 7 days) in the relapse.

Having established the reproducibility of S. enterica serovar Typhi PFGE patterns in isolates passaged in vitro or isolated during infection, the PFGE patterns of paired S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates taken from patients with relapses during the acute or relapse phase were examined. Cleavage with I-CeuI gave similar patterns of seven DNA fragments, as expected, for all isolates (data not shown) (14). The sizes of the seven DNA fragments were calculated from at least two independent gel electrophoresis runs and were totaled to give an approximation of the genome size of each isolate. The mean genome size was 4,450 kbp, with very little variation (range, 4,300 to 4,500 kbp). Partial cleavage with I-CeuI revealed that all the S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates were either type 2 or type 3 by using the analysis of Liu et al. (14) and were the two types most commonly identified by those investigators. The paired isolates obtained during the acute and relapse phases from each patient had the same I-CeuI type for each patient.

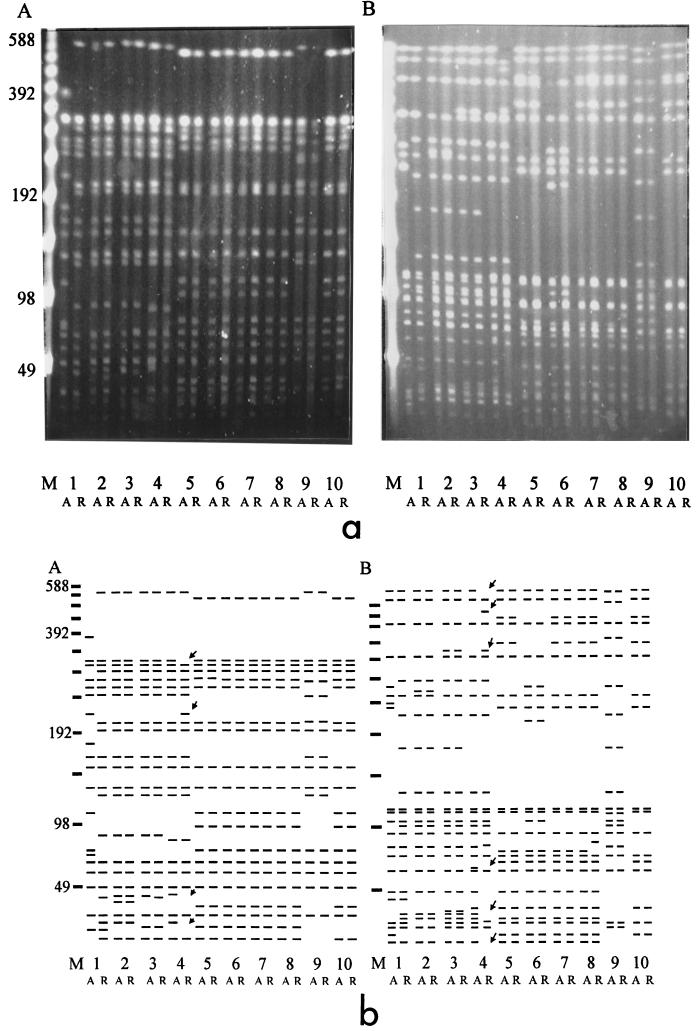

Total genomic DNA cleaved with either XbaI or BlnI revealed complex PFGE patterns that required the use of a long gel protocol for maximum resolution (Fig. 3a). DNA prepared from the isolates obtained during the acute and relapse phases from individual patients generated PFGE patterns that were distinct for the isolates from each patient following cleavage with either BlnI or XbaI. This is consistent with the presence of multiple PFGE patterns among S. enterica serovar Typhi strains in Vietnam. It was clear that comparison of most of the pairs of strains obtained from individual patients during the acute and relapse phases revealed indistinguishable patterns. There were two exceptions. The acute- and relapse-phase isolates from patient RR1 were clearly not the same (Fig. 3a and b) when the criteria suggested by Tenover et al. (32) were used because their XbaI and BlnI patterns differed by at least seven fragments. Close examination of the acute- and relapse-phase isolates from patient RR4 also revealed minor differences in the BlnI and XbaI patterns (arrow, Fig. 3b). The differences were in more than one DNA fragment but were consistent with the type of changes observed when some isolates were passaged in vitro. In addition, some of these differences can be accounted for by the lack of plasmids in the relapse isolate, which results in DNA fragment differences in the lower portion of the gel. If only the two fragment differences in the upper portion of the gel were counted, they would be categorized as “closely related” by the criteria of Tenover et al. (32). Cluster analysis confirmed the relationships between strains (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

(a) Agarose gel showing the PFGE patterns of S. enterica serovar Typhi relapse isolates. (A) XbaI cleavage patterns. Lane 1, RR1-A and RR1-R; lane 2, RR2-A and RR2-R; lane 3, RR3-A and RR3-R; lane 4, RR4-A and RR4-R; lane 5, RR5-A and RR5-R; lane 6, RR6-A and RR6-R; lane 7, RR7-A and RR7-R; lane 8, RR8-A and RR8-R; lane 9, RR9-A and RR9-R; lane 10, RR10-A and RR10-R. A, strain from acute-phase sample; R, strain from relapse-phase sample. (B) BlnI cleavage patterns of the same DNA preparations described for panel A. Lane M, bacteriophage lambda concatamer molecular size marker, with the sizes of the DNA fragments (in kilobase pairs) indicated to the left of the figure. (b) Cartoon interpretation of the panels in part a of the figure. Arrows indicate differences between RR4-A and RR4-R.

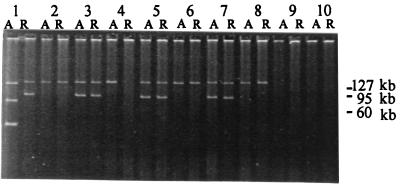

Plasmids from acute- and relapse-phase strains.

Most of the S. enterica serovar Typhi strains in this study had one or two large plasmids of 80 to 140 kb (Fig. 4), although strain RR1-A had two additional smaller plasmids of approximately 30 and 50 kb. The smallest plasmid is not visible in Fig. 4 but was identified and sized by electrophoresis on a standard 0.8% gel (data not shown). The RR1-A and RR1-R pair of isolates, which had already been identified as different according to their PFGE profiles, also had clearly different plasmid profiles (Fig. 4). The acute- and relapse-phase isolates from patient RR4 differed in their plasmid profiles. The acute-phase isolate from patient RR4 harbored a 140-kb plasmid which was absent from the relapse-phase isolate. Plasmid transfer experiments have shown that this 140-kb plasmid encodes multiple-drug resistance (our unpublished data). Antibiotic sensitivity testing of acute- and relapse-isolates from patient RR4 revealed that acute-phase isolate was multiple-drug resistant, whereas the relapse-phase isolate was susceptible (Table 2). Immediately after isolation in the clinical laboratory in Vietnam the relapse-phase isolate from patient RR4 was reported to be multiple-drug resistant, and, thus, this strain may have lost the 140-kb plasmid on storage. All other pairs of acute- and relapse-phase isolates had identical plasmid profiles: either a single 140-kb plasmid or both a 140-kb and an 80- to 90-kb plasmid. All isolates with the larger 140-kb plasmid were multiple-drug resistant (Table 2).

FIG. 4.

Plasmids isolated from strains from patients with relapses. Sizes of known plasmid markers (in kilobase pairs) are indicated to the right of the gel. The lanes are the same as those for Fig. 3a and b.

TABLE 2.

Summary of typing resultsa

| Strain designation | Resistance phenotype | Phage type | Plasmid profile (kb) | I-CeuI type | Ribotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR1-A | MDR Nas | Deg Vi | 135, 80, 50, 30 | 3 | 1 |

| RR1-R | MDR Nas | UT Vi2 | 140, 90 | 3 | 1 |

| RR2-A | MDR Nar | UT Vi | 140 | 3 | 1 |

| RR2-R | MDR Nar | UT Vi | 140 | 3 | 1 |

| RR3-A | MDR Nas | UT Vi2 | 140, 85 | 3 | 1 |

| RR3-R | MDR Nas | UT Vi2 | 140, 85 | 3 | 1 |

| RR4-A | MDR Nas | 56 | 140 | 3 | 1 |

| RR4-R | FS Nas | 56 | NONE | 3 | 1 |

| RR5-A | MDR Nas | E3 Var | 140, 80 | 2 | 2 |

| RR5-R | MDR Nas | E3 Var | 140, 80 | 2 | 2 |

| RR6-A | MDR Nas | E1 | 140 | 2 | 2 |

| RR6-R | MDR Nas | E1 | 140 | 2 | 2 |

| RR7-A | MDR Nar | E3 Var | 140, 80 | 2 | 2 |

| RR7-R | MDR Nar | E3 Var | 140, 80 | 2 | 2 |

| RR8-A | MDR Nas | E1 | 140 | 2 | 2 |

| RR8-R | MDR Nas | E1 | 140 | 2 | 2 |

| RR9-A | FS Nas | N | NONE | 3 | 1 |

| RR9-R | FS Nas | N | NONE | 3 | 1 |

| RR10-A | FS Nas | E1 | NONE | 2 | 2 |

| RR10-R | FS Nas | E1 | NONE | 2 | 2 |

Abbreviations: A, strain from acute-phase sample; R, strain from relapse-phase sample; MDR, multiple-drug resistant (resistant to chloramphenicol, ampicillin, co-trimoxazole, and tetracycline); Nar, resistant to nalidixic acid; FS, susceptible to all antibiotics tested; Deg, degraded; UT, untypeable; Var, variant; None, no detectable plasmids. The I-CeuI types are those used by Liu and Sanderson (18).

Ribotyping and phage typing.

Ribotyping was not found to be a useful method for discrimination of the set of S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates examined in the present study. Seven DNA fragments were detected in each isolate, five of which were common to all RR isolates (data not shown). The positions of the other two DNA fragments varied, but there were only two patterns, and those are assigned type 1 or type 2 in Table 2. The phage typing results, however, correlated well with the results of PFGE (Table 2). In summary, of the 10 pairs of acute- and relapse-phase isolates examined, nine pairs, including the isolates from patient RR4, were of the same phage type. Interestingly, the acute- and relapse-phase pair of isolates from patient RR1 were found to be of different phage types, confirming that these are indeed different S. enterica serovar Typhi strains.

DISCUSSION

A relapse of typhoid fever may be due to recrudescence or reinfection (19). If the initial strain of S. enterica serovar Typhi is identical to the strain that causes the second attack, then the relapse would normally be defined as a recrudescence. If the two strains are different, then the second attack would be classified as a reinfection, presumably with a new strain. However, if a patient is infected more than once from the same source (i.e., from a single carrier), then an apparent recrudescence may actually be reinfection. Alternatively, the first infection may be caused by more than one strain and only one strain is detected initially, whereas the other strain causes a recrudescence. Assuming that neither of these is very likely, then typing should prove to be valuable for the assessment of treatment response, for a greater understanding of the immune response to infection, and for epidemiological surveillance (11).

At the Centre for Tropical Disease referral center in Ho Chi Minh City, we have observed a 5% relapse rate among 322 patients treated with ceftriaxone or cefixime for periods of 3 to 14 days and a 1.5% relapse rate among 642 patients treated with fluoroquinolones for periods of 2 to 14 days. The broad-spectrum cephalosporins are less effective than the fluoroquinolones (the median fever clearance time of 7 days with broad-spectrum cephalosporins is also inferior to that with chloramphenicol or trimethoprim-sulfonamide). These estimates of cure rates are likely to be underestimates, because patients may have a recurrent attack of typhoid that is blood culture negative or mild attacks during which samples are not obtained for culture, or alternatively, they may attend a different hospital for their second attack.

In the series of 10 patients with recurrent attacks of typhoid fever examined in the present study, the average afebrile period between the resolution of the first attack and the beginning of the second attack was longer than that usually described in the past, although periods as long as 70 days have been reported. Most of the patients in the present series presented in the second week of their illness and were of similar age to other typhoid patients admitted to the Centre for Tropical Disease. In nine patients the relapses were less severe than the initial episodes, but in one patient it was more severe. The response to therapy in the initial attack was usually slower than that in the relapse; median fever clearance times were 4.8 days (range, 3.0 to 7.5 days) for the acute attack and 3.4 days (range, 2.3 to 7.0 days) for the relapse. The patients came from a wide variety of locations and were not concentrated in one particular area. The ability to distinguish between typhoid recrudescence and reinfection is particularly important in evaluations of the efficacies of new antibiotics, understanding of host immunity, and control of the spread of disease. Antibiotic sensitivity patterns and phage typing have been used in the past to distinguish between relapse and reinfection, but these methods are not sufficiently sensitive (11). The development of molecular methods for the typing of S. enterica serovar Typhi now allows a more precise distinction to be made.

We have used a number of approaches to the typing of S. enterica serovar Typhi in an attempt to describe more completely the infecting organism. In order to validate PFGE as a tool in a region of high background endemicity, the stability of the PFGE patterns of the Vietnamese isolates was established first. This was particularly important because many different PFGE patterns were present in a relatively small geographical area. There was no information on how rapidly the genome of the S. enterica serovar Typhi was evolving in this environment, where selective pressure from widespread antimicrobial resistance, unrestricted access to antibiotics, and common partial host immunity may all exert profound influences. Minor differences in DNA fragment patterns were detected, but these were consistent with either plasmid loss or single-base-pair differences within restriction enzyme target sites. Major changes in PFGE patterns or in I-CeuI profiles that would suggest recombination between rRNA operons, a phenomenon reported previously (18), were not observed. Cleavage of DNA with I-CeuI did not reveal any significant size variations in the genomes of the different S. enterica serovar Typhi tested in this study. Other workers (37) have detected genome size variations among S. enterica serovar Typhi clinical isolates.

Several different plasmids were detected in the present study. All multiple-drug-resistant isolates carried a 140-kb plasmid, and several had an additional 80- to 90-kb plasmid. It was confirmed that the large 140-kb, multiple-drug-resistance plasmids belong to the IncHI incompatibility group. This is the same group to which plasmids from other multiple-drug-resistant S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates described in Southeast Asia belong (8, 26). The 80- to 90-kb plasmid does not appear to be involved in drug resistance but is common and stable. The acute-phase isolate from patient RR4 carried the 140-kb plasmid, whereas at the time of plasmid analysis, this plasmid was absent from the relapse-phase isolate. However, at the time of clinical isolation this organism was multiple-drug resistant, suggesting that this plasmid had been lost on storage. The data from PFGE and plasmid typing for the 10 patients show that one pair of acute- and relapse-phase strains were different from each other, whereas the isolates in the other nine pairs were the same S. enterica serovar Typhi strains and caused recrudescences. The appearance of S. enterica serovar Typhi strains with reduced sensitivity to fluoroquinolones will result in poorer responses to these antibiotics in the future and the potential for more relapses (39). In Vietnam, where typhoid is rapidly becoming untreatable due to the emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance, the PFGE and plasmid typing combination of typing schemes is now being used to investigate these repeat infections further.

In conclusion, we have shown that PFGE is both reproducible and discriminatory and can be used to analyze multiple-drug-resistant S. enterica serovar Typhi strains in a region where typhoid is endemic. By this approach, in combination with other approaches, it is possible to examine the relationship between S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates taken from the same patient during acute and relapse phases of infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the directors and staff of the Centre for Tropical Diseases, Dong Nai Paediatric Hospital, and Dong Thap Provincial Hospital for support during this work.

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust UK.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bethell D B, Day N P, Dung N M, McMullin C, Loan H T, Tam D T, Minh L T, Linh N T, Dung N Q, Vinh H, MacGowan A P, White L O, White N J. Pharmacokinetics of oral and intravenous ofloxacin in children with multidrug-resistant typhoid fever. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2167–2172. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.9.2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler T, Rumans L, Arnold K. Response of typhoid fever caused by chloramphenicol-susceptible and chloramphenicol-resistant strains of Salmonella typhi to treatment with trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole. Rev Infect Dis. 1982;4:551–561. doi: 10.1093/clinids/4.2.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Couturier M, Bex F, Bergquist T L, Maas W. Identification and classification of bacterial plasmids. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52:375–395. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.3.375-395.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dylewski J S, Somlo F. Concurrent infection with multiple strains of Salmonella typhi. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;5:567. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.3.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Echeita M A, Usera M A. Chromosomal rearrangements in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi affecting molecular typing in outbreak investigations. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2123–2136. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.2123-2126.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fica A, Fernandez-Beros M E, Aron-Hott L, Rivas A, D’Ottone K, Chumpitaz J, Guevara J M, Rodriguez M, Cabello F. Antibiotic-resistant Salmonella typhi from two outbreaks: few ribotypes and IS200 types harbor Inc HI1 plasmids. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:339–343. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gotuzzo E, Morris J G, Jr, Benavente L, Wood P K, Levine O, Black R E, Levine M M. Association between specific plasmids and relapse in typhoid fever. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1779–1781. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.9.1779-1781.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hampton M D, Ward L R, Rowe B, Threlfall E J. Molecular fingerprinting of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:317–320. doi: 10.3201/eid0402.980223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermans P W, Saha S K, van Leeuwen W J, Verbrugh H A, van Belkum A, Goessens W H. Molecular typing of Salmonella typhi strains from Dhaka (Bangladesh) and development of DNA probes identifying plasmid-encoded multidrug-resistant isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1373–1379. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1373-1379.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hessel A, Liu S-L, Sanderson K L. Abstracts of the 95th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1995. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. The chromosome of Salmonella paratyphi C contains an inversion and is rearranged relative to Salmonella typhimurium LT2, abstr. H61; p. 503. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Islam A, Butler T, Ward L R. Reinfection with a different Vi-phage type of Salmonella typhi in an endemic area. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:155–156. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivanoff B. Third Asia-Pacific Symposium on Typhoid Fever and Other Salmonellosis. 1997. Typhoid fever: global overview, abstr. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kado C I, Liu S-L. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1365-1373.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu S-L, Hessel A, Sanderson K L. Genomic mapping with I-CeuI, an intron-encoded endonuclease specific for genes for ribosomal RNA, in Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli and other bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6874–6878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu S-L, Sanderson K L. Rearrangements in the genome of the bacterium Salmonella typhi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1018–1022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu S-L, Sanderson K L. I-CeuI reveals conservation of the genome of independent strains of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3355–3357. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3355-3357.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu S-L, Sanderson K L. Genomic cleavage map of Salmonella typhi Ty2. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5099–5107. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.5099-5107.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S-L, Sanderson K L. Highly plastic chromosomal organisation in Salmonella typhi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10303–10308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marmion D E, Naylor G R E, Stewart I O. Second attacks of typhoid fever. J Hyg Camb. 1953;51:260–267. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400015680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCrea T. The symptoms of typhoid fever. In: Osler W, McCrea T, editors. Modern medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea Brothers and Co.; 1907. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murdoch D A, Banatvala N A, Bone A, Shoismatulloev B I, Ward L R, Threlfall E J. Epidemic ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella typhi in Tajikistan. Lancet. 1998;351:339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)78338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nair S, Poh C L, Lim Y S, Tay L, Goh K T. Genome fingerprinting of Salmonella typhi by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for subtyping common phage types. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;113:391–402. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800068400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navarro F, Llovet T, Echeita M A, Coll P, Aladuena A, Usera M A, Prats G. Molecular typing of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2831–2834. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2831-2834.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen T C, Solomon T, Mai X T, Nguyen T L, Nguyen T T, Wain J, To S D, Smith M D, Day N P, Le T P, Parry C, White N J. Short courses of ofloxacin for the treatment of enteric fever. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:347–349. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pang T, Levine M M, Ivanoff B, Wain J, Finlay B B. Typhoid fever—important issues still remain. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:131–133. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01236-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards H, Datta N. Plasmids and transposons acquired by Salmonella typhi in man. Plasmid. 1982;8:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(82)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowe B, Ward L R, Threlfall E J. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella typhi: a worldwide epidemic. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;27(Suppl. 1):S106–S109. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shanahan P M, Jesudason M V, Thomson C J, Amyes S G. Molecular analysis of and identification of antibiotic resistance genes in clinical isolates of Salmonella typhi from India. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1595–1600. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1595-1600.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith C L, Condemine G. New approaches for physical mapping of small genomes. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1167–1172. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1167-1172.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith M D, Duong N M, Hoa N T, Wain J, Ha H D, Diep T S, Day N P, Hien T T, White N J. Comparison of ofloxacin and ceftriaxone for short-course treatment of enteric fever. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1716–1720. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thong K L, Cheong Y M, Puthucheary S, Koh C L, Pang T. Epidemiologic analysis of sporadic Salmonella typhi isolates and those from outbreaks by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1135–1141. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1135-1141.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thong K L, Puthucheary S, Yassin R M, Sudarmono P, Padmidewi M, Soewandojo E, Handojo I, Sarasombath S, Pang T. Analysis of Salmonella typhi isolates from Southeast Asia by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1938–1941. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1938-1941.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thong K-L, Cordano A-M, Yassin R M, Pang T. Molecular analysis of environmental and human isolates of Salmonella typhi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:271–274. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.271-274.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thong K L, Passey M, Clegg A, Combs B G, Yassin R M, Pang T. Molecular analysis of isolates of Salmonella typhi obtained from patients with fatal and nonfatal typhoid fever. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1029–1033. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.1029-1033.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thong K L, Puthucheary S D, Pang T. Genome size variation among recent human isolates of Salmonella typhi. Res Microbiol. 1997;148:229–235. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(97)85243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thong K L, Ngeow Y F, Altwegg M, Navaratnam P, Pang T. Molecular analysis of Salmonella enteritidis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and ribotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1070–1074. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1070-1074.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vinh H, Wain J, Vo T N, Cao N N, Mai T C, Bethell D, Nguyen T T, Tu S D, Nguyen M D, White N J. Two or three days of ofloxacin treatment for uncomplicated multidrug-resistant typhoid fever in children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:958–961. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wain J, Hoa N T, Chinh N T, Vinh H, Everett M J, Diep T S, Day N P, Solomon T, White N J, Piddock L J, Parry C M. Quinolone-resistant Salmonella typhi in Viet Nam: molecular basis of resistance and clinical response to treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1404–1410. doi: 10.1086/516128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wain J, Diep T S, Ho V A, Walsh A M, Nguyen T T, Parry C M, White N J. Quantitation of bacteria in blood of typhoid fever patients and relationship between counts and clinical features, transmissibility, and antibiotic resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1683–1687. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1683-1687.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White N J, Dung N M, Vinh H, Bethell D, Hien T T. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics in children with multidrug resistant typhoid. Lancet. 1996;348:547. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)64703-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White N J, Parry C M. The treatment of typhoid fever. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1996;9:298–302. [Google Scholar]