ABSTRACT

There are about 4–6 slips on a fruit, and they are good materials for effective regeneration of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus. Adventitious root (AR) induction is essential for the propagation of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus slips. Growth regulator treatment, and culture medium are imperative factors that affect slip growth and rooting. In order to screen the optimal methods for slips rooting and reveal the anatomic procedure of slip rooting, this study induced slip rooting by different treatment of growth regulator, culture medium, observed the slip stem structure, AR origination and formation procedure through paraffin sections. The results showed that, slip cuttings treated with 100 mg/L of Aminobenzotriazole (ABT) for 6 hrs, cultured in river sand: coconut chaff: garden soil 2:2:1 medium is the optimal method for rooting. The proper supplementary of ABT can enhance the soluble sugar content, soluble protein content, polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity and peroxidase (POD) enzyme activity, which resulted in the improvement of rooting. The slip stem structure is quite different from other monocots, which consists of epidermis, cortex, and stele with vascular tissues distributed in the cortex and stele. The AR primordia originates from the parenchyma cells located on the borderline between the cortex and stele. The vascular tissues in the AR develop and are connected with vascular tissue of the stem before the AR grew out the stem. The number of primary xylem poles in AR is about 30.

KEYWORDS: Ananas comosus var. bracteatus, slip, adventitious root, root primordia, growth regulator

1. Introduction

Ananas comosus var. bracteatus is an economical important horticultural plant species because of its red fruit and colorful leaves. Ananas comosus var. bracteatus is self-incompatible, propagated by suckers in production. There are about 1–2 suckers on a plant, which limit the effective regeneration of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus. However, there are about 4–6 slips on a fruit of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus, it is a good alternative way of propagating. Unlike the suckers and crown buds, which form adventitious root primordia in the stem when they grow on the mother plant, the slips does not form AR primorida inside the stem when they grow on the mother plants. The lack of developed AR primordia can be linked to a low rate of slip rooting. It is important to reveal the rooting procedure and find out slip rooting optimal method for improving the propagation rate of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus.

During the developmental process of roots, they are organized gradually from a simple form to a highly hierarchical architecture.1 The root contains three functional internal parts, the meristem, th elongation zone, and maturation zone.2 The meristem is at the root tip, area where cell division and growth occur to develop new cells.3 Above this area is the elongation zone, where cells increase in size through minerals and water absorption.4 The increase in cell size causes the root to push through the soil5 while maturation of cells causes differentiation of specific tissues such as epidermis, cortex, and vascular tissues.6 The epidermis forms the outermost layer of cells surrounding the root.7 Generally, rooting is initiated during embryogenesis which is branched afterward to lateral root formation.8 On the other hand, during post-embryonic roots formation, different adventitious roots (AR) are reproduced through vegetative propagation techniques from non-rooting tissues.9 The formation of ARs from non-root tissue such as leaves, slips, hypocotyls, stems, and shoots are triggered by favorable action10 such as wounding,11 cutting, excessive water supply, and loss of primary root growth.12 Arabidopsis thaliana forms adventitious roots after continues absence of light.13 Solanum lycopersicum seedlings ARs are initiated after flooding or excess water supply.14 Moreover, growth induction regulators can also initiate the formation and development of ARs.15 The induction of AR formation allowed for clonal propagation.16 The use of slip, sucker and buds for propagating process can achieve large quantity and quality of regenerated plants when adventitious root formation is enhanced.17 Even though there is no pericycle in stem and leaf, the cell divisions of parenchyma cells in a depth-layer connecting to the vascular tissues can initiate adventitious roots formation.18 Ananas comosus plant species have cup-like leaf axils rudimentary (partially developed) roots called axillary roots that can absorb moisture and dissolved nutrients directly.19 Generally, Ananas comosus families root system are typical monocot adventitious root system.20 In this study, we revealed the histological process of slip adventitious root formation. As an alternative key technique for propagation, we screened the optimal growth regulator treatment and culture medium for slip rooting. This knowledge will provide the needed formation on adventitious rooting formation and development in Ananas comosus var. bracteatus slip, helpful to understand rooting mechnism and propagates Ananas comosus var. bracteatus more effectively.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant materials

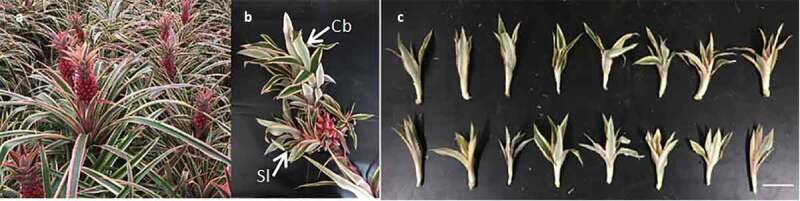

The slips of chimeric plants of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus with 6–8 expanded leaves were selected (Figure 1AB).

Figure 1.

Plant material used in this experiment. (a) Parent plant, (b) Crown buds (Cb) and Slips (Sl) on the fruit of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus (c) Slips for AR induction experiment. Scale bar = 5 cm

The slips of equal size were carefully cut out from the parent fruit (Figure 1c) and used as plant material for this study. The rooting experiment was carried out in a semi-enclosed greenhouse, and was done under natural variation during May to August.

2.2. Selection of root induction treatment

Four different factors at three different levels L9(34) orthogonal test were used to screen optimal methods for slip rooting (Table 1). The culture medium consisted of river sand, coconut chaff, and garden soil in different volume ratio (1:1:1, 2:1:1, 2:2:1), respectively.

Table 1.

The factors and levels of L9(34) orthogonal test for AR induction

|

Treatment number |

Culture medium (river sand: coconut chaff: garden soil) |

Regulator types |

Concentration (mg/L) |

Treat time (hrs) |

| 1 | 1:1:1 | Aminobenzotriazole (ABT) |

50 | 1 |

| 2 | 1:1:1 | 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) | 100 | 3 |

| 3 | 1:1:1 | Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) | 200 | 6 |

| 4 | 2:1:1 | 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) | 50 | 6 |

| 5 | 2:1:1 | Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) | 100 | 1 |

| 6 | 2:1:1 | Aminobenzotriazole (ABT) |

200 | 3 |

| 7 | 2:2:1 | Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) | 50 | 3 |

| 8 | 2:2:1 | Aminobenzotriazole (ABT) |

100 | 6 |

| 9 | 2:2:1 | 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) | 200 | 1 |

Before planting, the slips were immersed in growth regulators of Aminobenzotriazole (ABT), 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), and indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) at concentrations of 50 mg/L, 100 mg/L, 200 mg/L for 1 hr, 3hrs, and 6 hrs at room temperature, separately. Each treatment was triplicated with 30 slips.

2.3. Rooting index determination

The rooting time was calculated from the beginning of the experiment until ARs were visible on the stem base. After 40 days of growth, the slips were taken out from their respective medium, washed with water, and dried on filter paper at room temperature. The root length (RL), root number (RN), and rooting rate (RR) were recorded. The rooting rate was calculated as (Rooting rate = Number of rooting slips/Total number of slips × 100%).

2.4. Physiological indicators content of the induced slips

The soluble sugar content, soluble protein content, peroxidase (POD) enzyme activity, and polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity of the basic 1–2 cm rooting region of the slips stem under the selected best rooting treatment (T8) were determined. The soluble sugars were determined by the Anthrone Colorimetric method,21 while the soluble protein was determined by the Coomassie Brilliant Blue method.22 The POD enzyme activity was determined by the Guaiacol Colorimetric method,23 and the PPO activity assay was determined by the Catechol Colorimetric method.24

2.5. Histological observation of the rooting process

The histological observation was conducted by paraffin section following the steps as described.25 All the treatments samples were fixed in 70% FAA for 2 d: 10 ml of 40% formaldehyde, 5 ml acid, and 85 ml of 70% ethanol. Fixation was followed by an ethanol dilution series and a subsequent stepwise exchange of ethanol with Histoclear (xylem substitute). After that, the samples were fixed in paraffin and cut with a microtome (Leica RM2245, Leica Biosystems, Nussloch-Germany) into 12-μm-thick sections. The paraffin-embedded tissue sections were about 1–8 steps to obtain clear vision of cells. The sections were stained with safranin and fast green26 and examined under a light microscope (Olympus BX50; 50–300× magnification).

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Observation of the ARs emergence on slip stem

After 18 days of induction, ARs were observed at the base of the slip stem (Figure 2a). The ARs grew from the root primordium at the incision base without the formation of callus. When the ARs grew longer, the base part becomes lignified but the ARs at the tip remain tender to keep effective absorption capacity (Figure 2b). Along with the ARs growth, lateral roots were formed on the primary adventitious roots to create root system (Figure 2c). This root system character help Ananas comosus var. bracteatus to be highly adaptable to drought environment. This is in consistent with Oryza sativa, where the stem develops adventitious root primordia on each node to form an entirely new secondary root system.27

Figure 2.

Rooting procedure of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus slips. (a) ARs were observed on the base of the slip stem. (b) ARs grew longer and more lignified. (c) Lateral roots formed on the primary roots. Bar = 1 cm

3.2. The screen of optimal ars induction treatment method

The growth regulator type, growth regulator treatment methods, and composition of culture medium significantly affected the slips rooting situation. After 40 days of culture, the rooting condition of the slips was recorded. The rooting rate of growth medium ratio 2:2:1 induced with ABT, treatment eight (T8, 70.47%) was significantly higher than other treatments (Figure 3a). There was a significant difference of rooting quality among the nine (9) treatments (Table 1). The average rooting length of T8 is 5.97 cm, with an average rooting number of 8.77 was significantly higher than the other treatments (Figure 3BC). Furthermore, the rooting time of T8 was significantly shorter than other treatments (Figure 3d). Treated with 100 mg/L ABT for 6 hrs and cultured on the medium composed of river sand, coconut chaff, and garden soil (2:2:1) was the optimal AR induction approach for Ananas comosus var. bracteatus slips root induction. The present results revealed the positive effects of growth regulators in improving AR induction of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus, in consistent with Zea mays,28 and Gypsophila paniculata L.29 where the adventitious roots developed significantly after induction supplemented with ABT to promote rooting and plantlet growth increased, respectively.

Figure 3.

The rooting situation of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus slips under different treatments after 40 days of culture. (a), Rooting rate, (b) Rooting length,(c) Rooting Number, and (d) Rooting time, after the treatment period

3.3. Physiological changes in the rooting stem of Ananas comosus var. Bracteatus slip

The test results showed that T8 (slips in growth medium ratio 2:2:1 induced with 100 mg/L ABT) was the optimal AR induction approach (Figure 3). The T8 treated and control (treated with water without growth regulator) slips were used to analyze the physiological changes occurred during the rooting period. About 18d of culture, the ARs were visible (Figure 2a) parameters detected here showed a high peak value on the 18d (Figure 4). All the parameters detected here in the ABT treated slip stem is higher than that of the control (Figure 4). The soluble sugar and soluble protein content decreased from 0–12d but reached the highest significant value on the 18th day (Figure 4AB). The decrease of soluble sugar and soluble protein content during 0–12d may be due to the slow metabolism of the slips and need to consume sugar and protein to promote adventitious roots formation.30 After 18d of culture, the AR grew out from the stem, signifying the absorption ability of the slip, resulting in the accumulation of soluble sugar and soluble protein. In Cunninghamia lanceolate tissue cultured seedling, ABT treatment increased the soluble sugar content and soluble protein content.31 From 18–24d, the soluble sugar and soluble protein started to decrease as the adventitious roots elongates, increasing in numbers, consuming large amount of soluble sugar and protein for cell division. After 24–30 days, the slip soluble sugar and protein content increased. As adventitious roots are formed and elongated, the new plants metabolism are accelerated, and proteins can be synthesized.32 The appropriate concentration of exogenous rooting agents increased PPO activity, resulted in the improvement of the rooting rate and formation of more complex roots.31 After 18 d of ABT treatment, PPO and POD activity increased to a peak value, and then decreased between 18 and 30 days (Figure 4CD). It was possibe because of the demand for PPO enzymes in the formation of adventitious roots and the decline of the phenolic activity in the slips.32 In Olea europaea L., PPO activity slowly increased at the early stage of the AR inducing period and then decreased apparently.33 In other work, the POD activity concentration increased in Tamarix chinensis treated with ABT leading to increase of adventitious roots formation.32

Figure 4.

The physiological changes in the slip stem of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus. The figure represent culture period of 30 days for ddH2O (No Regulator) and the optimal ABT growth regulator induction treatment T8 (slips in growth medium ratio 2:2:1 induced with 100 mg/L of ABT). (a) Change of soluble sugar content during rooting, (b) Changes of soluble protein content, (c) Changes of Polyphenol oxidase activity during rooting, and (d) Changes of Peroxidase activity during rooting

3.4. The anatomical structure of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus slips stem

ARs are formed from a specified differentiated cell and developed from a location where they do not usually occur.27 In order to understand the origination of the ARs, we studied the anatomic structure of the slip stem first. The cross-section structure of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus slip stem is divided into epidermis, cortex, and stele (Figure 5AH). This structure is quite different from many monocots, such as Oryza sativa, and Zea mays, where they do not have stele in the stem.34 Moreover, most gramineous plants stem structure consists of epidermis, basic tissues, and vascular bundles, without distinct demarcation between the cortex and stele cells.35 Vascular bundles are distributed differently in the cortex and stele of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus slip stem. These vascular bundles distributed in the cortex region are smaller and sparse, but larger and more densed in the stele region. The vascular tissues form an apparent border between the cortex and stele (Figure 5AH). The epidermis (Ep) is located in the outermost part of the slip stem, consisting of about 1–2 layers tightly arranged as protective tissues.30 The epidermal cells are approximately square-shaped with a stratum corneum covering (Figure 5b). Inside epidermis are multi-layer thickened cells called collenchyma cells (Col), revealed to give mechanical support to the slip epidermal tissues36 (Figure 5b). The cortex is mainly composed of parenchymal cells (Pa), spherical and highly vacuolated in structure but not differentiated. These parenchyma cells are organized random and loose. Some of the parenchymal cells are enlarged and specialized to contain crystals (Cr) (Figure 5c). Conducting tissues for transverse transport was formed at the axis of the stem, and the procambial beam surround it furtherly differentiated into mature vascular cambium (Figure 5d). During the primary meristem thickening of Oryza sativa, the cell division does not produce enough parenchymal cells and procambial meristematic tissues that could penetrate through the parenchyma cells; hence, thin stem axis is observed.37

Figure 5.

Anatomical features of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus slip stem. (a) The structure of the slip stem without AR initiation is consisted of epidermis (Ep), cortex (Co), and stele (St). (b) The epidermal (Ep) and collenchyma cells (Col) under the epidermis to form mechanical tissues. (c) The parenchyma cells in the cortex (Co) of the stem are round. Some of the parenchyma cells are big, and contain crystals (Cr). (d) Radial arranged vascular tissue in the stem’s cortex. (e) Vascular bundles located in the cortex of the stem. (f) The vascular bundle located at the border between cortex and stele. (g) The vascular bundle located in the stele of the stem. (h) The structure of the rooting slip stem. Ve: vessel; Si: sieve tube; Cc: companion cell and Vbs: vascular bundle sheath

In many cases, the primary thickened meristems can be found in many monocots with thick stalks, such as Zea mays, Saccharum officinarum, Musa acuminata, Arecaceae, and Iris germanica.27 From our observation, the vascular bundles in the slip stem stele are large and more lignified than that in the cortex (Figure 5e-h). The vascular bundles of Zea mays stem are organized in circle at the cortex’s inner region, forming a distinct boundary between the cortex and the stele.38 The slip stem vascular bundles consists of xylem, phloem, and bundle sheath, but these layers are not conspicuous as other monocots, which these layers are the main features in the stem. Compared to the classic monocots such as Oryza sativa and Zea mays, the developed vascular tissues and the differentiation of cortex and stele enhanced the absorption efficiency of water and nutrient.37 This distinct absorption efficiency can was also observed in Ananas comosus var. bracteatus slip stem is an adaptative feature for growth and survival under stress conditions such as drought.

3.5. Location of adventitious root primordia in the slip stem

ARs and AR primordia at different developmental stages were observed in the slip stem rooting (Figure 6AC). Signs of the AR primordia formation were detected in the stem region between borderlines 2 to 5 (Figure 6a). Beyond line 2, was exact place predicted for leaf emergence with no AR primordium (Figure 6BD). In the non-rooting region of the stem, the differences between cortex and stele is not so clear (Figure 6d), while there was an apparent circle between the cortex and stele in the rooting region in the stem (Figure 6DE). In the AR primordia formation region (between lines 2–5), big vascular bundles are connected together to form a notable circle (Figure 6e). The ARs grew downward across the cortex and then breakout from the stem to form mature ARs, then a complete cross-section of AR is observed in the stem cortex (Figure 6AF).

Figure 6.

The sites of ARs formation in the slip stem of A. comosus var. bracteatus. (a) Longitude section of the rooting stem. Leaves generated from the upper part of the stem (line 1) and the ARs emerged at the lower part of the stem (between lines 2–5). Line 1 represents section location of the sections in B and D. Line 3 represents section location corresponding to the sections in C and E. Line 4 represents section location of the section in F. (b, d) Cross section at line 1, located above the AR formation region. No AR primordia were observed in this region. (c, e) Cross-section at line 3, AR primordia was developed frequently in the Co of the stem. (f) Cross-section at line 4. Adventitious root primordia and adventitious root are visible in the stem’s cortex, Rp: root primordia; AR: adventitious root; Co: cortex and St: stele

Contrary to our findings, is the stem of Psaronius which does not have a concentric rings but the stem consist of a central stele composed of numerous arcs representing xylem tissues.39 Transections of the slip stem between borderline 2–5 (Figure 6a) was used to study the anatomic procedure of AR initiation and development.

3.6. Origination of the adventitious root primordia in the slip stem

A cross-section along the rooting stem showed the initiation and development of adventitious root primordia. During the early rooting period, some vascular bundles were connected to form bigger vascular tissues. These vascular tissues are close to each other to form a ring surrounding the stele (Figure 6e). The borderline between cortex and stele near the vascular bundles was the place AR primordia originates (Figure 7a-f). On the boundary between the stele and cortex, the vascular bundles are connected to form more prominent vascular tissue surrounded by large and round parenchyma cells (Figure 7a). Some of the parenchyma cells dedifferentiated and regained ability predicted for cell division. These cells are divided into two long strip cells by periclinal division (Figure 7b), and the generated parenchyma cells continues division forms the primary primordia (Figure 7c-f). A continues cell division and differentiation of these cells lead to the fully developed adventitious root primordium in the slip stem (Figure 7g-i). Moreover, the formation of the slip stem root primordia is divided inot stages. First, the primary primordia forms the root cap covering and protecting the tip of the AR primordia (Figure 7g). The continues cells division inside the root cap form elongation and mature region.

Figure 7.

Adventitious root primordia formation inside the slip stem of A. comosus var. bracteatus. (a) Vascular tissues on the border between cortex (Co) and stele (St) of the stem. Some of the primary vessels of the vascular bundles were lignified (dark-stained). Parenchyma cells surrounded the vascular tissues are large and round. (b) Some of the parenchyma cells outside the vascular tissue circle between cortex and stele carried out the periclinal division (arrowhead). (c) Early stages of cell divisions where an adventitious root primordium is initiated (circle). (d) The dividing cells (arrowhead) in the early stages of adventitious root primordium. (e) Larger and more advanced adventitious root primordium (circle) with dividing meristematic cells. (f) Cell division and expansion lead to the increased size of the developing adventitious root primordium and forming a dome-like structure (circle). (g-i) The development of the adventitious root primordium. The stem cells (Sc) were protoplasm-rich (dark-stained) and cubical shaped. At the outer part of the root tip formed root cap (Rc) surrounded the stem cells. Lacuna (La) is formed between the adventitious root primordium and the cortex of the stem. (i) Developed adventitious root primordium with differentiated root cap (Rc), a region of stem cells (Sc), the region of elongation (El), and maturity region (Ma). Co: cortex; St: stele; Va: vascular tissue; Rc: root cap; Sc: stem cell; La: lacuna; El: elongation region; Ma: maturity region

The cells of the elongation region are long and vacuolized, making the root grow longer. In the mature region, the vascular tissues are developed, and are connected to the stem vascular tissues (Figure 7i). Along with the development of the AR primordia, the cortex cells are destroyed and lacuna. This is revealed to provide space for the development of ARs. The developed root primordia do not remain dormant as exposed to the desired environment, as small white swellings tip develop on the stem (Figure 2). In other work in Oryza sativa under drought stress40 but contrarily to Ipomoea batatas L. the developed root primordia remain dormant17 and Solanum dulcamara rapidly supply of water induces AR primordia formation.41

3.7. Development and growth of adventitious root in the stem

The elongation and enlargement of existing cells and the generation of additional cells led to the growth of the AR primordia through the stem (Figure 8a). The well-developed AR primordia grow obliquely downward inside the stem and break out of the stem at last (Figure 8a-c). It is revealed that, as Hedera helix AR primordia matures and lignifies the formation of its adventitious roots decreases.42 Nevertheless, Ananas comosus var. bracteatus slip AR does not develop alone, their vascular tissues are connected with the stem vascular tissues to increase elongation of ARs downwards in the stem (Figure 8d). Because the ARs grow downward in the stem cortex, a complete cross-section of ARs can be observed (Figure 8e). In many monocot plants, the stele and cortex are merge together, forming vascular tissues to form specialized tissues like xylem and phloem for transport and grow with the vascular bundles43 different from Ananas comosus var. bracteatus where the cortex and stele are separated.

Figure 8.

Development and growth of adventitious root inside the stem of A. comosus var. bracteatus. (a) Longitudinal section of the rooting stem showing the well-developed, lignified (brown) adventitious root grow inside the stem. Line 1 presents the section location of sections in B and D. Line 2 presents the section location of sections in C and E. (b, d) The vascular tissue of the stele of the adventitious root is connected with the vascular tissue of the stem at the base part of the adventitious root. (c, e) Along with the elongation of the adventitious root, it grows obliquely downward. There is a lacuna between the adventitious root and the cortex of the stem. D and E are paraffin sections of the part surrounded by a block in B and C, respectively. Co: cortex; St: stele; Ar: adventitious root

3.8. Anatomical structure of the adventitious root of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus

The mature AR exhibit conspicuous cortex, epidermis, and stele, surrounded by vascular tissues (Figure 9AD). The cortex consists of parenchyma cells, and beneath is the exodermis. The Air cavity (Ac) is located close to the epidermis, this can enhance the resistance of the plant (Figure 9BE). The side-by-side thicken-wall endodermis (En) cells forming Casparian strip. The inner part of the endodermis is the stele, consisted of pericycle (Pe), pith cells, primary xylem, and phloem vessels (Figure 9c). The matured AR is highly lignified when it grew out of the stem (Figure 9DF). Within the stele, the walls of the pericycle cell are thickened and lignified (Red stained). Like the stele, the pith cell walls are thickened and lignified (Red stained) to form mechanical tissue (figure 9f).

Figure 9.

Anatomic structure of the adventitious root. (a) The young adventitious root formed in the stem. The root is consists of the epidermis (Ep), cortex (Co), and stele (St). (b) The character of the epidermis and cortex of the adventitious root. Under the epidermis is the exodermis (Ex). The cortex is consists of parenchyma cells (Pa). The Air cavity (Ac) was formed in the cortex. (c) The innermost cell of the cortex is the endodermis (En). The thickening of the endodermis cell wall developed the Casparian strip. The Inner endodermis is the stele (St), consisting of pericycle (Pe), primary xylem, primary phloem, and pith. Sclerenchyma (Sc) is formed in the pith. Si: sieve tube; Ve: vessel. (d) The structure of the mature lignified adventitious root. (e) The structured character of the cortex of mature adventitious root. The cell wall of exodermis cells thickened and lignified to form mechanical tissue (deeply red-stained). (f) The structure characteristics of the stele of the mature adventitious root. The cell wall of a pericycle is thickened and lignified (deeply red-stained). Lpe: lignified pericycle. The vessel is highly lignified (red-stained). The pith cell’s cell wall is thickened and lignified (deeply red-stained) to form mechanical tissue (Mt). Pve: protovessel; Mve: metavessel

The number of primary xylem poles in the AR is about 30. The stem stele parenchyma cells are identified as the only tissue capable of initiating AR formation. The high lignification of the ARs is structured for adaptation of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus to high temperature, high light, and drought conditions.

4. Conclusion

This study has revealed that the slip stem structure of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus can be divided into epidermis, cortex, and stele. Vascular tissues are distributed differently in cortex and stele to form a clear borderline. The ARs grew from root primordia, not from callus. The AR primordia originated from the dedifferentiated parenchyma cells located near vascular tissues on the borderline between stele and cortex. The AR matured in the stem before growing out the stem, with about 30 primary xylem poles. ABT increased the soluble sugar content, soluble protein content, PPO activity and POD activity in slips and promoted the initiation and development of ARs. The slips treated with 100 mg/L ABT for six hours (6hrs), cultured in river sand, coconut chaff, and garden soil in 2:2:1 ratio is optimal for the rooting of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus slips.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sichuan Agricultural University, China, for supporting this work.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, 31770743; 31971704 (http://www.nsfc.gov.cn).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Author contributions

MOA wrote the manuscript. YX conducted the research. YH analyzed the anatomic results. XZ referenced the manuscript. MM, review the manuscript. JL planted the slips in the medium. HH conducted the induction treatment. JL, HZ, LF, WY take part in the planting experiment and microscope observation. XL analyzed the results. JM designed the experiment, organized the figures, and evaluated the manuscript for further corrections.

References

- 1.Teixeira PC, Novais RF, Barros NF, Neves JCL, Teixeira JL.. Eucalyptus urophylla root growth, stem sprouting and nutrient supply from the roots and soil. For Ecol Manage. 2002;160::1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shishkova S, Rost T, Dubrovsky J.. Determinate root growth and meristem maintenance in angiosperms. Ann Bot. 2008;101:319–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark SE. Cell signalling at the shoot meristem. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groß-Hardt R, Laux T. Stem cell regulation in the shoot meristem. J Cell Sci. 2003(116): 1659-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucob‐Agustin N, Kawai T, Takahashi‐Nosaka M, Kano‐Nakata M, Wainaina CM, Hasegawa T, Inari‐Ikeda M, Sato M, Tsuji H, Yamauchi A, et al. WEG1, which encodes a cell wall hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein, is essential for parental root elongation controlling lateral root formation in rice. Physiologia Plantarum. 2020;169(2):214–227. doi: 10.1111/ppl.13063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan L, Linker R, Gepstein S, Tanimoto E, Yamamoto R, Neumann PM. Progressive inhibition by water deficit of cell wall extensibility and growth along the elongation zone of maize roots is related to increased lignin metabolism and progressive stelar accumulation of wall phenolics. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:603–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamura M, Grebe MJ. Outer, inner and planar polarity in the Arabidopsis root. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2018;41:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harada J. Signaling in plant embryogenesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2:23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellini C, Pacurar DI, Perrone I. Adventitious roots and lateral roots: similarities and differences. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2014;65:639–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geiss G, Gutierrez L, Bellini C. Adventitious root formation: new insights and perspectives. Annu Plant Rev Online. 2018;127–156. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Efroni I, Mello A, Nawy T, Ip P-L, Rahni R, DelRose N, Powers A, Satija R, Birnbaum KD. Root regeneration triggers an embryo-like sequence guided by hormonal interactions. Cell. 1721-33;2016(165). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucas M, Swarup R, Paponov IA, Swarup K, Casimiro I, Lake D, Peret B, Zappala S, Mairhofer S, Whitworth M, Wang J. Short-Root regulates primary, lateral, and adventitious root development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2011;155:384–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Da Costa CT, Gaeta ML, de Araujo Mariath JE, Offringa R, Fett-Neto AG. . Comparative adventitious root development in pre-etiolated and flooded Arabidopsis hypocotyls exposed to different auxins. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2018;127:161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vidoz ML, Loreti E, Mensuali A, Alpi A, Perata P. Hormonal interplay during adventitious root formation in flooded tomato plants. The Plant Journal. 2010;63:551–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Druege U, Franken P, Hajirezaei MR. Plant hormone homeostasis, signaling, and function during adventitious root formation in cuttings. Frontiers in Plant Science.2016;7:381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorpe TA, Patel KR, Vasil I. Clonal propagation: adventitious buds. Cell Culture and Somatic Cell Genet Plants. 2012;1:49–60. [Google Scholar]

- 17.YASUI K. 11. Notes on the Propagation of Sweet Potato, Ipomoea Batatas Lam. Proc Imperial Acad. 1944;20::41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steffens B, Rasmussen A. The physiology of adventitious roots. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:603–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng Y, Bartholomew D, Qin Y. Biology of the Pineapple Plant. Genet Genomics Pineapple. 2018;Springer:27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillemin J-P, Gianinazzi S, Gianinazzi-Pearson V, Marchal J, Science F. Contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizas to biological protection of micropropagated pineapple (Ananas comosus (L.) Merr) against Phytophthora cinnamomi Rands. Agric Food Sci. 1994;3:241–251. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Li J. Determination of the content of soluble sugar in sweet corn with optimized anthrone colorimetric method. Storage Process. 2013;13:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asryants R, Duszenkova I, Nagradova N. Determination of Sepharose-bound protein with Coomassie brilliant blue G-250. Anal Biochem. 1985;151:571–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sachadyn-Król M, Materska M, Chilczuk B, Karaś M, Jakubczyk A, Perucka I, Jackowaska I. Ozone-induced changes in the content of bioactive compounds and enzyme activity during storage of pepper fruits. Food Chem. 2016;211:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan T-T, Sun D-W, Paliwal J, Pu H, Wei Q. New method for accurate determination of polyphenol oxidase activity based on reduction in SERS intensity of catecho. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:11180–11187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerk NM, Ceserani T, Tausta SL, Sussex IM, Nelson TM. Laser capture microdissection of cells from plant tissues. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmitz N, Laverty S, Kraus V, Aigner T. Basic methods in histopathology of joint tissues. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:S113–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin C, Sauter M. Control of adventitious root architecture in rice by darkness, light, and gravity. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:1352–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ZHAO M ZHOUS-X, Y-h CUI. Research and application of plant growth regulators on maize (Zea mays L.) in China [J]. J Maize Sci. 2006;1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wahome PK, Oseni TO, Masarirambi MT, Shongwe VD. Effects of different hydroponics systems and growing media on the vegetative growth, yield and cut flower quality of gypsophila (Gypsophila paniculata L.). World J Agric Sci. 2011;7:692–698. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Javelle M, Vernoud V, Rogowsky PM, Ingram GC. Epidermis: the formation and functions of a fundamental plant tissue. New Phytologis. 2011;189:17–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Y, Liang Y, Yang M. Effects of composite LED light on root growth and antioxidant capacity of Cunninghamia lanceolata tissue culture seedlings. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun J, Xia J, Zhao X, Su L, Li C, Gao F, Liu P. Effects of rooting powder and soil salt stress on the growth and physiological characteristics of Tamarix chinensis cuttings. Research Square. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ortega‐García F, J P. The response of phenylalanine ammonia‐lyase, polyphenol oxidase and phenols to cold stress in the olive tree (Olea europaea L. cv. Picual). Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2009;89::1565–1573. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saleem M, Lamkemeyer T, Schützenmeister A, Madlung J, Sakai H, Piepho H-P, Nordheim A, Hochholdinger F. Specification of cortical parenchyma and stele of maize primary roots by asymmetric levels of auxin, cytokinin, and cytokinin-regulated proteins. Plant Physiology. 2010;152:4–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roncato-Maccari LD, Ramos HJ, Pedrosa FO, Alquini Y, Chubatsu LS, Yates MG, Rigo LU, Steffens MB, Souza EM. Endophytic Herbaspirillum seropedicae expresses nif genes in gramineous plants. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2003;45:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crang R, Lyons-Sobaski S, Wise R. Parenchyma, Collenchyma, and Sclerenchyma. Plant Anat. 2018;Springer:181–213. [Google Scholar]

- 37.IV N. Botany. Pattern in the meristems of vascular plants: III. Pursuing the patterns in the apical meristem where no cell is a permanent cell. Journal of the Linnean Society of London, Botany. 1965;59:185–214. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Philipson W, Balfour EE. Vascular patterns in dicotyledons. The Botanical Review. 1963;29:382–404. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gillette N. Morphology of some American species of Psaronius. Botanical Gazette. 1937;99:80–102. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rebouillat J, Dievart A, Verdeil J-L, Escoute J, Giese G, Breitler J-C, Gantet P, Espeout S, Guiderdoni E, Perin C. Molecular genetics of rice root development. Rice. 2009;2:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dawood T, Rieu I, Wolters-Arts M, Derksen EB, Mariani C, Visser E. Rapid flooding-induced adventitious root development from preformed primordia in Solanum dulcamara. AoB Plants. 2014;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reineke RA, Hackett WP, Smith AG. Lignification associated with decreased adventitious rooting competence of English ivy petioles. Journal of Environmental Horticulture.2002;20:236–239. [Google Scholar]

- 43.McSteen P. Auxin and monocot development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]