Abstract

Background

Due to SARS-CoV-2-related encephalopathic features, COVID-19 patients may show cognitive sequelae that negatively affect functional outcomes. However, although cognitive screening has been recommended in recovered individuals, little is known about which instruments are suitable to this scope by also accounting for clinical status. This study thus aimed at comparatively assessing the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in detecting cognitive deficits in post-COVID-19 patients premorbidly/contextually being or not at risk for cognitive deficits (RCD + ; RCD-).

Methods

Data from N = 100 COVID-19-recovered individuals having been administered both the MMSE and the MoCA were retrospectively analyzed separately for each group. RCD ± classification was performed by taking into consideration both previous and disease-related conditions. Equivalent scores (ESs) were adopted to examine classification performances of the two screeners.

Results

The two groups were comparable as for most background and cognitive measures. MMSE or MoCA adjusted scores were mostly unrelated to disease-related features. The two screeners yielded similar estimates of below-cut-off performances—RCD + : MMSE: 20%, MoCA: 23.6%; RCD-: MMSE: 2.2%, MoCA: 4.4%. However, agreement rates dropped when also addressing borderline, “low-end” normal, and normal ability categories—with the MoCA attributing lower levels than the MMSE (RCD + : Cohen’s k = .47; RCD-: Cohen’s k = .17).

Discussion

Although both the MMSE and the MoCA proved to be equally able to detect severe cognitive sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection in both RCD + and RCD- patients, the MoCA appeared to be able to reveal sub-clinical defects and more sharply discriminate between different levels of ability.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Cognitive screening, Mini-Mental State Examination, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Psychometrics

Introduction

Due to both primary and secondary encephalopathic features of SARS-CoV-2 infection [1], COVID-19 patients may show both short- and long-term cognitive sequelae within the dysexecutive and amnesic spectrum [2]—which have been postulated as negatively affecting prognosis and functional outcomes [3].Consistently, first-level cognitive assessment has been recommended in COVID-19-recovered individuals [3]. However, little consensus has been reached as for which psychometric instruments should be adopted to this scope.

Among screening tools, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) have proved effective in detecting global cognition deficits following COVID-19 [2]—despite the former and the latter seemingly being more sensitive to severe and mild-to-moderate dysfunctions, respectively [4]. In this respect, the choice of suitable screeners is further challenged by the complex interplay between disease-related outcomes—i.e., encephalopathic complications of COVID-19 and iatrogenic effects of COVID-19 treatments on the brain—and premorbid neurological/medical-general risk factors for cognitive impairment [4].

This study thus aimed at comparing the performance of the MMSE and the MoCA in the screening for cognitive sequelae in post-infectious SARS-CoV-2 patients being or not at risk for cognitive deficits (RCD+; RCD-) due to either previous or disease-related conditions.

Methods

Materials

Data from N=100 COVID-19-recovered individuals referred to Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri located in Northern Italy between May 2020 and 2021 who had been administered both the MMSE and the MoCA were retrospectively collected (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ background, clinical, and psychometric measures

| Domain | Outcome | RCD + | RCD- | p† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | |||||

| N | 55 | 45 | - | ||

| Age (years) | 66.13 ± 13.84 (18–85) | 63.33 ± 11.4 (28–85) | .105 | ||

| Sex (male/female) | 34/21 | 39/6 | .005* | ||

| Education (years) | 11.2 ± 3.63 (2–19) | 11.02 ± 3.89 (3–18) | .664 | ||

| Clinical | |||||

| Disease duration (days) | 40.6 ± 26.72 (2–113) | 42.31 ± 26.26 (5–129) | .649 | ||

| Time from onset (days) | 74.13 ± 41.02 (7–241) | 76.43 ± 35.33 (26–186) | .522 | ||

| Severity | .008* | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 9.1% | 2.2% | - | ||

| Mildly symptomatic | 18.2% | 6.7% | - | ||

| Mild-to-moderate | 25.5% | 11.1% | - | ||

| Moderate-to-severe | 47.3% | 80% | - | ||

| ICU | 45.5% | 71.1% | .015* | ||

| Steroids | 12.7% | 20% | .186 | ||

| Infection | 32.7% | 35.6% | .433 | ||

| Psychometric | |||||

| MMSE | 27 ± 3.36 (15–30) | 28.22 ± 1.94 (22–30) | .115 | ||

| MoCA | 21.71 ± 4.97 (8–30) | 23.51 ± 3.09 (18–30) | .186 | ||

RCD + patients at risk for cognitive deficits, RCD- patients not at risk for cognitive deficits, MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination, MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment, ICU intensive care unit

†p-values refer to either χ2 (categorical measures) or Mann–Whitney U (continuous measures)

*Significant at α = .05

COVID-19 severity was classified as “asymptomatic,” “mildly symptomatic,” “mild-to-moderate” (requiring O2 but not ventilation), and “moderate-to-severe” (requiring either non-invasive ventilation or ICU).

RCD+ group included patients with (a) previous neurological or psychiatric disorders, (b) a history of severe internal conditions or ≥3 internal/metabolic risk factors for cognitive dysfunction, and (c) COVID-19-related neuropsychiatric manifestations. By contrast, RCD- patients did not present with the abovementioned risk factors. This classification was performed, on the basis of medical records, by two independent authors blinded to patients’ cognitive outcome; disagreements were solve throughout discussion with an independent judge.

Statistics

Associations/predictions were tested via non-parametric approaches due to normality not being met (as assessed through skewness and kurtosis values).

Inferential analyses were run separately for RCD+ and RCD+ groups; a Bonferroni-adjusted α=.025 was thus adopted.

MMSE and MoCA scores were adjusted for age and education and converted to equivalent scores (ESs) [5] based on current norms [6, 7]. The ES scale allows drawing clinical classifications from performances as follows: ES=0 → impaired; ES=1 → borderline; ES=2 → “low-end” normal; ES=3 → normal; and ES=4 → “high-end” normal. As being standardized, the ES scale allows comparisons between different tests having different original metrics.

Inter-rater agreement between MMSE and MoCA clinical classifications was tested through weighted Cohen’s k [8].

Analyses were performed via SPSS 27 (IBM Corp., 2020).

Results

RCD+ and RCD- patients were balanced as for the majority of demographic and clinical measures—except for sex, severity and ICU admission—as well as for cognitive scores (see Table 1).

When assessed separately for each group, no disease-related variables affected either MMSE or MoCA adjusted scores (severity: 2.73≤H(3)≤4.14; p≤.302; steroids: 41≤U≤51; p≤.09; duration in days: .26 ≤rs≤.07; p≤.059; days from onset to assessment: .24 ≤rs≤.06; p≤.058) except for infections in RCD+ patients (MMSE: U=166.5, p=.003; MoCA: U=180, p=.006)—with those who showed them reporting lower scores (MMSE: M=25.59, SD=2.97 vs. M=27.83, SD=2.88; MoCA: M=19.86, SD=3.57 vs. M=22.79, SD=4.14).

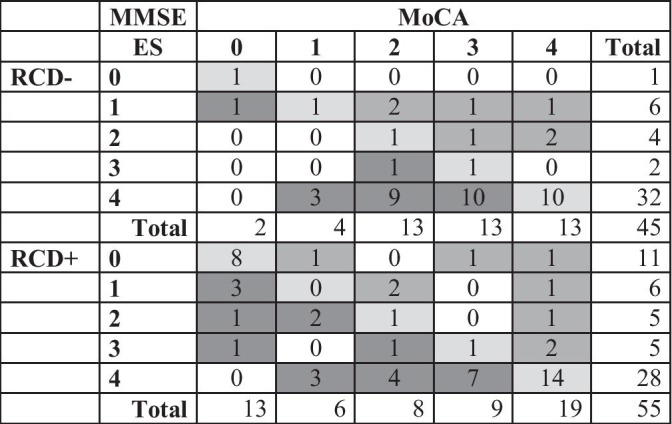

Within both groups, the two tests provided similar prevalences of defective performances (ES=0)—RCD+: MMSE: 20%, MoCA: 23.6%; RCD-: MMSE: 2.2%, MoCA: 4.4%. Agreement rates for such dichotomous classification were indeed found to be substantial for RCD- patients (Cohen’s k=.66) and moderate for RCD+ (Cohen’s k=.57).

However, when addressing the full range of ESs (0–4), agreement rates dropped by also showing an inverse pattern (see Table 2), as being poor for RCD- (Cohen’s k=.17) and moderate for RCD+ (Cohen’s k=.47). Indeed, the MMSE tended to classify less conservatively those performances that were addressed by the MoCA as either defective, borderline, or “low-end” normal—this especially occurring for RCD+ patients. Several misclassification were detected also for ESs of 3 and 4 (normal and “high-end” normal)—the MoCA being more conservative than the MMSE.

Table 2.

Equivalent score (ES) classifications by the MMSE and the MoCA

MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination, MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment, RCD- patients not at risk for cognitive deficits, RCD + patients at risk for cognitive deficits. ESs are to be interpreted as follows: ES = 0 → impaired; ES = 1 → borderline; ES = 2 → “low-end” normal; ES = 3 → normal; ES = 4 → “high-end” normal. Diagonal cells show agreements; extra-diagonal cells show disagreements

Discussion

The present study provides practitioners with useful information on the capability of the MMSE and the MoCA to detect sequelae deficits in COVID-19-recovered individuals who were or not at risk for cognitive deficits (RCD+ vs. RCD-) due to either premorbid or disease-related conditions.

Overall, both screeners proved to be equally able to detect severe cognitive sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection in both RCD+ and RCD- patient. This finding is consistent with the supposed amnesic/dysexecutive profile of COVID-19 patients—as the MMSE and the MoCA being reckoned, albeit to a different extent, as memory—and executive-loaded screeners [6, 7].

However, the MoCA proved to be slightly more sensitive than the MMSE in detecting sub-clinical cognitive changes, as well as abler than the MMSE in differentiating between diverse levels of cognitive efficiency [4]. These findings are in line with previous ones on the MoCA—which were also paralleled by neurofunctional evidence [4, 9]. Such differential performances of the two screeners appear to be also supported by the fact that, when considering different ability levels, their agreement was higher for patients whose putative cognitive impairment could be more easily detected (RCD+).

Results herewith reported should be borne in mind by practitioners since even mild/sub-clinical cognitive deficits have been shown to negatively affect functional outcomes of recovered COVID-19 individuals [10].

With regard to the interplay between premorbid status and cognitive after-effects of COVID-19 as assessed by the MMSE and the MoCA, the present work suggests that (1) non-COVID-19 comorbid infections might determine a decrease in cognitive efficiency that can be revealed by I-level tests in RCD+ patients; (2) the performance on such tests may not be associated with other disease-related variables; and (3) both screeners provide higher estimates of cognitive impairment in RCD+ patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all participants. The authors would like to thank Dr. Sharon Brambilla for her precious help to data collection.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Informed consent was acquired from patients. This study received approval from the local Ethics Committee (I.D.: 2470, 8 September 2020).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Edoardo Nicolò Aiello, Email: e.aiello5@campus.unimib.it.

Elena Fiabane, Email: elenamaria.fiabane@icsmaugeri.it.

Marina Rita Manera, Email: marina.manera@icsmaugeri.it.

Alice Radici, Email: alice.radici@icsmaugeri.it.

Federica Grossi, Email: federica.grossi@icsmaugeri.it.

Marcella Ottonello, Email: marcella.ottonello@icsmaugeri.it.

Debora Pain, Email: debora.pain@icsmaugeri.it.

Caterina Pistarini, Email: caterina.pistarini@icsmaugeri.it.

References

- 1.Ellul MA, Benjamin L, Singh B, Lant S, Michael BD, Easton A, Kneen R, Defres S, Sejvar J, Solomon T (2020) Neurological associations of COVID-19. The Lancet Neurology 19:767–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Daroische R, Hemminghyth MS, Eilertsen TH, Breitve MH, Chwiszczuk LJ. Cognitive impairment after COVID-19 - a review on objective test data. Front Neurol. 2021;12:1238. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.699582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson BA, Betteridge S, Fish J. Neuropsychological consequences of COVID-19. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2020;30:1625–1628. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2020.1808483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pistarini C, Fiabane E, Houdayer E, Vassallo C, Manera MR, Alemanno F. Cognitive and emotional disturbances due to COVID-19: an exploratory study in the rehabilitation setting. Front Neurol. 2021;12:643646. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.643646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capitani E, Laiacona M. Outer and inner tolerance limits: their usefulness for the construction of norms and the standardization of neuropsychological tests. Clin Neuropsychol. 2017;31:1219–1230. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2017.1334830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aiello EN, Gramegna C, Esposito A, Gazzaniga V, Zago S, Difonzo T, Maddaluno O, Appollonio I, Bolognini N (2021) The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): updated norms and psychometric insights into adaptive testing from healthy individuals in Northern Italy. Aging Clin Exp Res 1–8. 10.1007/s40520-021-01943-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Carpinelli Mazzi M, Iavarone A, Russo G, Musella C, Milan G, D’Anna F, Garofalo E, Chieffi S, Sannino M, Illario M, De Luca V. Mini-Mental State Examination: new normative values on subjects in Southern Italy. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32:699–702. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther. 2005;85:257–268. doi: 10.1093/ptj/85.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blazhenets G, Schröter N, Bormann T, Thurow J, Wagner D, Frings L, Weiller C, Meyer PT, Dressing A, Hosp JA. Slow but evident recovery from neocortical dysfunction and cognitive impairment in a series of chronic COVID-19 patients. J Nucl Med. 2021;62(7):910–915. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.121.262128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miskowiak KW, Johnsen S, Sattler SM, Nielsen S, Kunalan K, Rungby J, Lapperre T, Porsberg CM. Cognitive impairments four months after COVID-19 hospital discharge: pattern, severity and association with illness variables. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;46:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]