Abstract

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) play important roles in carcinogenesis. Here, we investigated the mechanisms and clinical significance of circ-NOL10, a highly repressed circRNA in breast cancer. Subsequently, we also identified RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that regulate circ-NOL10. Bioinformatics analysis was utilized to predict regulatory RBPs as well as circ-NOL10 downstream microRNAs (miRNAs) and mRNA targets. RNA immunoprecipitation, luciferase assay, fluorescence in situ hybridization, cell proliferation, wound healing, Matrigel invasion, cell apoptosis assays, and a xenograft model were used to investigate the function and mechanisms of circ-NOL10 in vitro and in vivo. The clinical value of circ-NOL10 was evaluated in a large cohort of breast cancer by quantitative real-time PCR. Circ-NOL10 is downregulated in breast cancer and associated with aggressive characteristics and shorter survival time. Upregulation of circ-NOL10 promotes apoptosis, decreases proliferation, and inhibits invasion and migration. Furthermore, circ-NOL10 binds multiple miRNAs to alleviate carcinogenesis by regulating PDCD4. CASC3 and metadherin (MTDH) can bind directly to circ-NOL10 with characterized motifs. Accordingly, ectopic expression or depletion of CASC3 or MTDH leads to circ-NOL10 expression changes, suggesting that these two RBPs modulate circ-NOL10 in cancer cells. circ-NOL10 is a novel biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis in breast cancer. These results highlight the importance of therapeutic targeting of the RBP-noncoding RNA (ncRNA) regulation network.

Keywords: circRNA, breast cancer, MTDH, CASC3, circ-NOL10

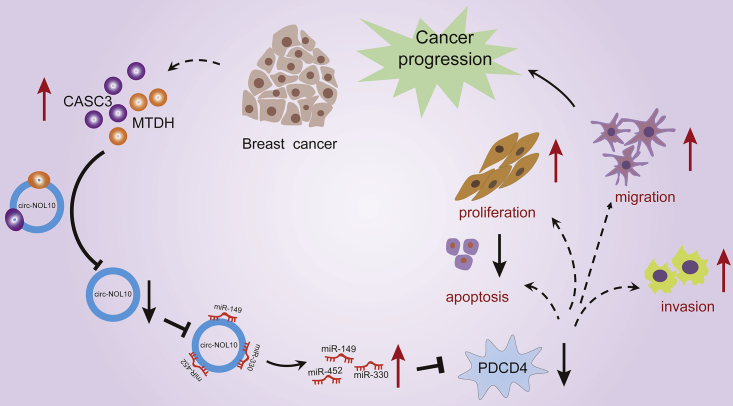

Graphical abstract

A novel RBP-ncRNA signaling route, formed by two RBPs (MTDH and CASC3), one circRNA (circ-NOL10), three miRNAs (miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, and miR-452-5p), and the effector PDCD4, is identified. This investigation reveals a ncRNA-mediated mechanism in breast cancer carcinogenesis and provides novel insights for therapeutic targeting of ncRNAs.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common and heterogeneous disease among women in the world.1 Despite continuous development of early diagnosis and improvement of treatments over the past few decades, there are still limited efficient therapies, especially in subtypes such as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). The median overall survival is only 10–13 months for metastatic TNBC.2 Therefore, understanding the molecular pathogenesis involved in cancer development and identifying novel biomarkers are essential to determine diagnosis, treatment strategies, and prognosis. Over the last few years, accumulating reports have found that noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), including circular RNAs (circRNAs), are implicated widely in breast cancer progression.3,4

circRNA is a circular form of endogenous ncRNA produced mainly by circularization of specific exons. Expression analyses have indicated that it is tissue- or developmental stage-specific and evolutionarily conserved between mice and humans.5,6 A variety of molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain circRNA function in human cancer, including acting as microRNA (miRNA) decoys, regulating gene splicing or transcription, translating peptides, and epigenetic regulation.4,7,8 Further, circRNAs are stable in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue and human biofluids, such as exosomes, saliva, and plasma, indicating their potential diagnostic values9, 10, 11

In breast cancer, we and others have discovered that several circRNAs inhibit tumor progression or promote tumorigenesis.12, 13, 14 For example, circEPSTI1 has been found to be increased significantly in TNBC samples. This circRNA is also a prognostic marker.14 Using a high-throughput circRNA microarray profiling platform, we identified a set of significantly decreased circRNAs in a large cohort of individuals with breast cancer. We elucidated the functions and molecular mechanisms of circTADA2As in breast cancer. Among these differentially expressed circRNAs, circ-NOL10 was the most downregulated in TNBC samples. In this study, we first investigated the clinical significance of circ-NOL10. Subsequently, we explored its biological roles and molecular mechanism during breast cancer progression. Furthermore, our bioinformatics analysis predicted that two RBPs (metadherin [MTDH] and CASC3 exon junction complex subunit [CASC3]) can directly bind to circ-NOL10, which is confirmed by follow-up experiments. Overall, we identified a novel RBP-ncRNA signaling route formed by two RBPs (MTDH and CASC3), one circRNA (circ-NOL10), three miRNAs (miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, and miR-452-5p), and the effector PDCD4 in breast cancer carcinogenesis.

Results

Circ-NOL10 is downregulated in breast cancer and associated with aggressive characteristics

We performed qPCR analyses on 178 breast cancer tissues (LA, N = 25; LB, N = 21; Her-2, N = 17; TNBC, N = 115) and 16 normal mammary gland tissues. Expression of circ-NOL10 is significantly lower in breast cancer tissue, which is consistent with our previous finding by circRNA array.13 The reduction of circ-NOL10 is more evident in LA and TNBC tissues (Figure 1A). Correspondingly, the expression levels of circ-NOL10 in 10 breast cancer cell lines were lower than in the immortalized mammary gland cell line MCF-10A (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Decreased expression of circ-NOL10 in breast cancer and clinical implications

(A) circ-NOL10 was significantly lower in breast cancer tissue. Shown is relative expression of circ-NOL10 in 178 breast cancer tissues (LA, N = 25; LB, N = 21; Her-2, N = 17; TNBC, N = 115) and 16 normal mammary gland tissues; each point represents one tissue sample. (B) circ-NOL10 was significantly lower in breast cancer cells. Shown is relative expression of circ-NOL10 in 10 breast cancer cell lines compared with MCF-10A cells. (C-F) ROC curve of circ-NOL10 in LA(C), LB (D), Her-2(E) and TNBC (F) using normal mammary gland tissues as control. (G and H) Kaplan-Meier analyses of the association between circ-NOL10 and DFS (G) or OS (H) in individuals with TNBC. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Notably, decreased circ-NOL10 expression is correlated significantly with advanced clinical stage (p = 0.018), increased lymphatic metastasis (p = 0.032), recurrence (p = 0.001), and death (p = 0.001) in individuals with TNBC (Table 1). These results suggest an association between downregulation of circ-NOL10 and aggressive characteristics of TNBC. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for circ-NOL10 were calculated. The area under the curve (AUC) for TNBC was 0.9212 (p < 0.0001; Figure 1F). Additionally, the AUCs for LA, LB, and Her-2 were 0.9275, 0.7619, and 0.9154, respectively (Figures 1C–1E), indicating that circ-NOL10 might be a promising diagnostic indicator for breast cancer. Next, according to the cutoff value of the ROC curve, individuals with TNBC were divided into two groups for disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) analyses. Interestingly, low circ-NOL10 expression was significantly related to shorter DFS (p = 0.032) and OS (p = 0.027) (Figures 1G and 1H). Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses indicated that circ-NOL10, like clinical stage, T classification status, and lymphatic metastasis, is a risk factor for DFS of individuals with TNBC (HR = 4.616, p = 0.043) and OS (HR = 3.886, p = 0.045) but not an independent prognostic factor for poor DFS and OS in the multivariate Cox model (Tables S1 and S2).

Table 1.

Correlation between clinicopathological factors and circ-NOL10 expression level in TNBC tissue (n = 115)

| Characteristics | No. of individuals (%) | Mean ± SEM | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| ≥55 | 42 (36.5%) | 0.02803 ± 0.00828 | 0.364 |

| < 55 | 73 (63.5%) | 0.04637 ± 0.01447 | |

| AJCC TNM stagea | |||

| I–II | 82 (74.5%) | 0.04876 ± 0.01331 | 0.018∗ |

| III–IV | 28 (25.5%) | 0.01451 ± 0.00507 | |

| T classificationb | |||

| T1–2 | 95 (91.3%) | 0.04540 ± 0.01159 | 0.296 |

| T3–4 | 9 (8.7%) | 0.00568 ± 0.00331 | |

| Lymphatic metastasis | |||

| N0–1 | 91 (79.1%) | 0.04576 ± 0.01207 | 0.032∗ |

| N2–3 | 24 (20.9%) | 0.01660 ± 0.00583 | |

| Relapsec | |||

| No | 91 (85.0%) | 0.04837 ± 0.01207 | 0.001∗∗ |

| Yes | 16 (15.0%) | 0.00502 ± 0.00150 | |

| Survivalc | |||

| Yes | 92 (86.0%) | 0.04786 ± 0.011945 | 0.001∗∗ |

| No | 15 (14.0%) | 0.00525 ± 0.00160 | |

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

4.35% patient information missing.

9.57% patient information missing.

6.96% patient information missing.

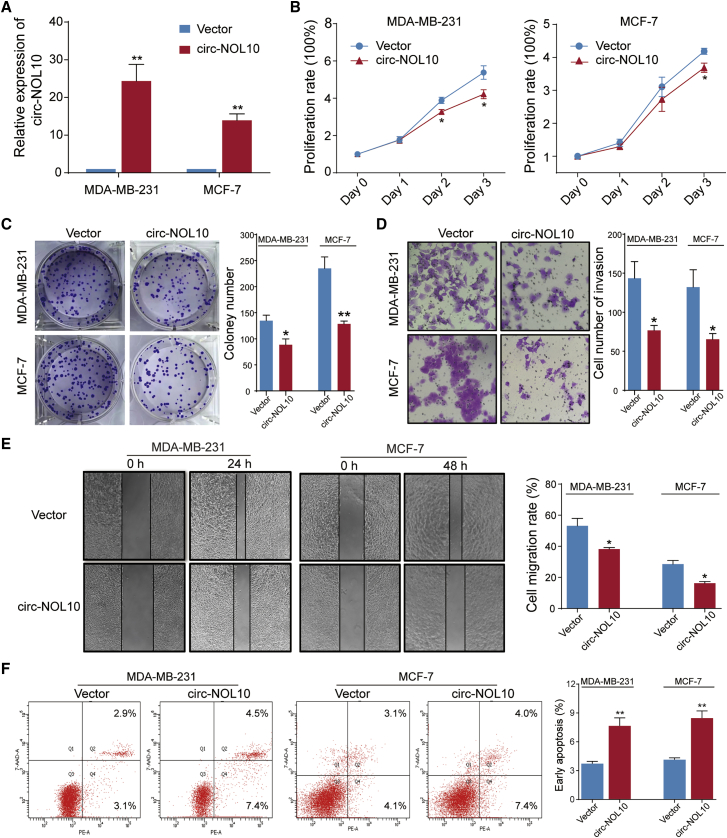

Circ-NOL10 inhibits breast cancer progression and metastasis

In view of circ-NOL10 being downregulated in breast tissue and cell lines, we overexpressed circ-NOL10 to further study its potential function in the MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cell lines. As shown in Figure 2A, ectopic expression of circ-NOL10 was increased significantly, indicating good overexpression efficiency. Upregulation of circ-NOL10 decreased cell proliferation (Figure 2B) and inhibited colony formation and invasion (Figures 2C–2D). Moreover, the wound healing assay demonstrated that ectopic expression of circ-NOL10 significantly inhibited migration of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Figure 2E). In addition, we investigated whether circ-NOL10 affects cell apoptosis using a flow cytometry assay. The results showed that early apoptosis could be triggered by circ-NOL10 overexpression but late apoptosis could not (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

circ-NOL10 suppresses cancer progression

Experiments were conducted after transfecting MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells with a circ-NOL10-expressing vector for 48 h. (A) Ectopic circ-NOL10 expression was analyzed by qPCR. (B) The effect of circ-NOL10 on cell viability was analyzed by CCK-8. (C) The effect of circ-NOL10 on colony formation was determined via a clonogenicity assay (left, representative pictures; right, quantitative bar for colony numbers). (D) The effect of circ-NOL10 on cell invasion was detected via a Transwell assay (left, morphological comparison of cell penetration; right, quantitative bar for number of penetrating cells). (E) The effect of circ-NOL10 on cell migration was measured by a wound scratch assay (left, representative images; right, quantitative bar for cell migration rate). (F) The effect of circ-NOL10 on early apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry in cells (left, representative images; right, quantitative bar for cell apoptosis rate). Error bars represent the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

To further confirm the function of circ-NOL10, we designed two small interfering RNA (siRNA)-circ-NOL10 products (circ-NOL10 siRNA#1 and siRNA#2) that could efficiently knock down expression of circ-NOL10 in cells (Figure 3A). Then alterations in proliferative capacity were evaluated using a CCK-8 assay. The results showed that depletion of circ-NOL10 could increase proliferation of breast cancer cells (Figure 3B). Furthermore, silencing circ-NOL10 expression significantly increased colony formation ability, migration, and invasion in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Figures 3C–3E). Flow cytometry results also showed that silencing circ-NOL10 by siRNAs decreased apoptosis (Figure 3F). Similar cellular function was also observed by siRNA treatment in MCF-10A cells, which expressed higher circ-NOL10 (Figure S1). These results suggest that circ-NOL10 plays a vital role in cell carcinogenesis.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of circ-NOL10 promotes breast cancer progression

Experiments were conducted after transfecting MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells with circ-NOL10 siRNAs for 24 h. (A) circ-NOL10 expression after transfecting was analyzed by qPCR. (B) The effect of circ-NOL10 siRNAs on cell viability was analyzed by CCK-8. (C) The effect of circ-NOL10 siRNAs on colony formation was determined via a clonogenicity assay (top, representative pictures; bottom, quantitative bar for colony numbers). (D) The effect of circ-NOL10 siRNAs on cell invasion was detected via a Transwell assay (left, morphological comparison of cell penetration; right, quantitative bar for number of penetrating cells). (E) The effect of circ-NOL10 siRNAs on cell migration was measured by a wound scratch assay (left, representative images; right, quantitative bar for cell migration rate). (F) The effect of circ-NOL10 siRNAs on early apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry in cells (left, representative images; right, quantitative bar for cell apoptosis rate). Error bars represent the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Circ-NOL10 reduces tumor growth in vivo

To study the function of circ-NOL10 in vivo, MDA-MB-231 cells were stably transfected with Lv-circ-NOL10 or Lv-circ-control and inoculated subcutaneously into nude mice. The tumors were monitored over a period of 21 days. The tumor volumes of the Lv-circ-NOL10 group were significantly smaller than those of the control group (Figures 4A–4C). A qPCR assay confirmed that circ-NOL10 expression was higher in circ-NOL10 overexpression mice (Figure 4D). Thus, the xenograft tumor model verified that circ-NOL10 can inhibit BC tumor growth in vivo.

Figure 4.

Circ-NOL10 reduces tumor growth in vivo

(A) The tumor volumes in subcutaneous tumor-bearing nude mice at 7, 10, 14, 18, and 21 days. (B and C) Subcutaneous tumors were removed from nude mice at 21 days, and tumor weights were measured. (D) circ-NOL10 expression in tumors after removal from nude mice. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Circ-NOL10 interacts with and sequesters miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, and miR-452-5p

To explore the molecular mechanism of circ-NOL10 in breast cancer, we determined the subcellular location of circ-NOL10 in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). As shown in Figure 5A, circ-NOL10 was expressed in the cytoplasm and nucleus in cancer cells. Previous studies have demonstrated that some circRNAs can function as miRNA sponges in breast cancer,13,15 so we combined several bioinformatics tools to predict miRNAs that potentially bind to circ-NOL10 (Figure 4B). Furthermore, we used the mirgator.kobic3.0 database to select eight miRNAs that are expressed abundantly in breast cancer tissues and have binding sites on circ-NOL10 (Figure 4C). Next, miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, miR-452-5p, and miR-767-5p were selected manually for experimental verification. Dual-luciferase reporter assays were performed with a recombinant reporter plasmid containing a luciferase gene and the circ-NOL10 sequence (psiCHECK2-circ-NOL10). A schematic of psiCHECK2-circ-NOL10 and circ-NOL10 recognition sites is shown in Figure 5D. Co-transfected psiCHECK2-circ-NOL10 and miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, and miR-452-5p significantly decreased firefly luciferase reporter activity, but there was no significant change for co-transfected psiCHECK2-NOL10 and miR-767-5p (Figure 5E). These results indicate that miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, and miR-452-5p can bind to circ-NOL10. Furthermore, the relative expression of miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, and miR-452-5p were reduced significantly after overexpression of circ-NOL10 in breast cancer cells (Figure 5F). Finally, we checked cellular apoptosis after co-transfection of these miRNAs or circ-NOL10 alone in cells. We found that overexpression of these three miRNAs in the circ-NOL10-treated group can significantly decrease cellular apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Figures 5G and 5H). These results confirmed our hypothesis that circ-NOL10 can interact with and sequester miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, and miR-452-5p in breast cancer.

Figure 5.

Circ-NOL10 interacts with and sequesters miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, and miR-452-5p in breast cancer cells

(A) The distribution of circ-NOL10 in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells detected by FISH. Red, Cy3-labeled probes specific to circ-NOL10; green, FITC-labeled probes specific to 18S RNA; blue, DAPI stain for nuclei; merge represents an overlay figure. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Multiple bioinformatics tools were used to find miRNA and circ-NOL10 interaction. (C) An illustration showing the putative binding sites of circ-NOL10 with miRNAs. miR-452-5p has two binding sites. (D) A schematic of the psiCHECK2-circ-NOL10 vector and circ-NOL10 recognition sites. (E) Luciferase activity of psiCHECK2-circ-NOL10 co-transfected with selected miRNA mimics or control mimics was determined by a reporter assay. The relative luciferase activity was normalized with Renilla activity. (F) miRNA expression after transfection of the circ-NOL10 overexpression plasmid or a control vector in MDA-MB-231 cells (left panel) and in MCF-7 cells (right panel). (G and H) The effect of circ-NOL10 on early apoptosis after transfection of circ-NOL10 or co-transfection with miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, or miR-452-5p in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (left, representative images; quantitative bar for cell apoptosis rate). ∗, circ-NOL10+miR NC compared with vector+miR NC; #, circ-NOL10+miRNA compared with circ-NOL10+miR NC. ∗, #p < 0.05; ∗∗, ##p < 0.01; ∗∗∗, ###p < 0.001.

Circ-NOL10 suppresses carcinogenesis by regulating PDCD4

Next we combined five bioinformatic databases (TargetScan, miRNAorg, PITA, PicTar, and miRDB) to analyze the potential miRNA targets. Four genes (TUSC2, PDCD4, GRIA3, and CCBE1) were selected based on overlap of these prediction results for follow-up experimental verification (Figure S2A). After ectopic expression of circ-NOL10, we found that only PDCD4 was increased significantly compared with vector transfection at the protein level (Figures S2B and S2C). Because miRNAs generally regulate target gene expression by inhibiting translation, we decided to focus on PDCD4 in the following experiments. As a tumor suppressor with multi-functions, PDCD4 has been reported to be involved in proliferation, migration, invasion, and apoptosis.16, 17, 18 Downregulation of PDCD4 was also associated with poor prognosis in previous studies.19,20 Importantly, it is a known target gene for miR-330-3p in esophageal cancer.21 After transfection of the circ-NOL10 plasmid or circ-NOL10 siRNAs, the protein level of PDCD4 was increased accordingly in circ-NOL10-overexpressing cells and decreased in siRNA circ-NOL10-treated cells (Figure 6A). Then we used two different siRNAs to inhibit expression of PDCD4 (Figure 6B). As shown in Figures 6C–6G, cell invasion, migration, and apoptosis assays indicated that knockdown of PDCD4 partially abolishes the effects of circ-NOL10 on breast cancer cells. Additionally, western blotting was performed to examine whether PDCD4 protein expression was affected by miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, and miR-452-5p. In MDA-MB-231 cells, a fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based assay indicated that apoptosis was promoted following transfection of miRNA inhibitors (Figure S2D). Accordingly, protein expression of PDCD4 was upregulated significantly. Apoptosis-related markers, cleaved caspase-3 and Bad, were also increased significantly after downregulation of miR-149-5p, miR330-3p, and miR452-5p (Figures S2E and S2F). Upregulation of circ-NOL10 induced PDCD4 and apoptosis marker expression, and the effects could be reversed by miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, and miR-452-5p mimics (Figures S2G and S2H). These data indicate that circ-NOL10 exerts a biological function via a circ-NOL10/miR-149-5p/miR-330-3p/miR-452-5p/PDCD4 pathway.

Figure 6.

Circ-NOL10 suppresses breast cancer progression by regulating PDCD4

(A) Western blot of PDCD4 after transfection of the overexpression circ-NOL10 plasmid or siRNAs in cells. (B) Expression of PDCD4 mRNA was examined after transfection two different siRNAs in cells. (C) Cell viability was analyzed by CCK-8. (D) Colony formation was determined via a clonogenicity assay (left, representative pictures; right, quantitative bar for colony numbers). (E) Cell invasion was detected via a Transwell assay (left, morphological comparison of cell penetration; right, quantitative bar for number of penetrating cells). (F) Cell migration was measured by a wound scratch assay (left, representative images; right, quantitative bar for cell migration rate). (G) Early cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry in cells (left, representative images; right, quantitative bar for cell apoptosis rate). Error bars represent the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

MTDH and CASC3 regulate formation of circ-NOL10 in breast cancer

An essential next step for understanding circRNA function is to identify key determinants in circRNA biogenesis. We reasoned that if a gene is a bona fide regulator, then it should have following characteristics: (1) alterations such as point mutation, copy number variation, and aberrant mRNA expression of this gene have been found in breast cancer, and (2) these alterations may have led to pathogenic changes and are correlated with survival. Based on these ideas, we analyzed multi-omics data of 825 BC samples and predicted 25 potential regulatory RBPs (materials and methods; Table S3). ADAR and FUS are involved in some circRNAs’ life cycle.22,23 Thus, combining our bioinformatics analysis and previous reports, we selected seven RBPs (ADAR, FUS, SRSF1, CWC15, CASC3, MTDH, and ESRP1) for further experiments. We constructed seven RBPs overexpression plasmids to examine whether they controlled aberrant expression of breast cancer-associated circ-NOL10. First, qPCR analyses showed that expression of circ-NOL10 was downregulated in cells’ ectopic expression of CASC3 or MTDH, but cells treated with the other five RBPs did not show a consistent pattern (Figure S3A). OS analyses found that individuals with more alterations on these two RBPs had a poor prognosis in the BRCA dataset, suggesting that they play crucial roles in carcinogenesis (Figure S3B). A siRNA assay was used to further verify the association of MTDH and CASC3 with circ-NOL10 (Figures 7A and 7B). The qPCR results indicated that inhibition of MTDH and CASC3 resulted in a significant increase of circ-NOL10 in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Figure 7C). These findings confirmed that CASC3 and MTDH could disrupt circ-NOL10 expression.

Figure 7.

MTDH and CASC3 regulate formation of circ-NOL10

(A–C) After transfecting cells for 48 h with MTDH and CASC3 siRNA#1 and siRNA#2, (A) MTDH and CASC3 mRNAs were analyzed by qRT-qPCR, (B) MTDH and CASC3 proteins were analyzed by western blot, and (C) circ-NOL10 expression was analyzed by qPCR. (D) IF-FISH assay showing that circ-NOL10 colocalized with MTDH and CASC3 proteins in MDA-MB-231 cell cytoplasm. Red, Cy3-labeled probes specific to circ-NOL10; green, MTDH and CASC3 protein; blue, DAPI stain for nuclei; merge represents an overlay figure. (E) MTDH and CASC3 proteins were analyzed by western blot after overexpression of MTDH and CASC3 in MDA-MB-231 cells. (F) qPCR was used to measure circ-NOL10 binding to MTDH and CASC3 by using an antibody against FLAG pulled-down bound complexes. Values were normalized to the level of background RIP, as detected by an IgG isotype control. (G) qPCR was used to measure circ-NOL10 binding to endogenous MTDH and CASC3 by using specificity antibody against CASC3 and MTDH. Values were normalized to the IgG isotype control. (H) Schematic illustrating luciferase reporters containing the circ-NOL10 sequence (Luc-circ-NOL10), mutated MTDH binding sites (Luc-circ-N-mut A and Luc-circ-N-mut B), and mutated CASC3 binding site (Luc-circ-N-mut C). The putative binding sites are colored in red, and the mutated sites (replaced by complementary sequences) are shown in green. (I) Reporter analyses showing the luciferase activity of Luc-circ-NOL10, Luc-circ-N-mut A, Luc-circ-N-mut B, and Luc-circ-N-mut C in 293 T cells ectopically expressing MTDH (left panel) or CASC3 (right panel). Quantitative data from three independent experiments are presented as mean ± SEM (error bars). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

An RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay was performed to determine whether MTDH and CASC3 can bind directly to circ-NOL10. Immunofluorescence and FISH (IF-FISH) analysis confirmed co-localization of circ-NOL10 with MTDH and CASC3 in the cytoplasm of MDA-MB-231 (Figure 7D). We transfected the pEZ-93-MTDH and pEZ-93-CASC3 plasmids, which express the encoded proteins fused to a FLAG tag, and individually overexpressed the two RBPs in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 7E). Bound complexes were pulled down using an antibody against FLAG. The qPCR results indicated that circ-NOL10 was highly enriched in the FLAG-containing group compared with the immunoglobulin G (IgG) isotype control (Figure 7F). We further verified the interactions between circ-NOL10 and endogenous RBPs by using a specific antibody against CASC3 and MTDH (Figure 7G).

To determine the binding motifs, the immunoprecipitated RNAs were also sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system. Bioinformatics analyses of RIP-seq reads showed two putative binding sites of MTDH and one of CASC3 on the circ-NOL10 (Figure 7H). As shown in Figure 7I, the luciferase activity of the reporter with the wild-type circ-NOL10 sequence (Luc-circ-NOL10) was inhibited significantly by MDTH and CASC3. This decrease was attenuated by mutation of MDTH binding sites (Luc-circ-N-mut A and Luc-circ-N-mut B) or the CASC3 binding site (Luc-circ-N-mut C). These experimental results suggest that CASC3 and MTDH bind circ-NOL10 to regulate its formation in breast cancer. Importantly, these results also demonstrate that our bioinformatics predictions can be verified experimentally.

Discussion

Our results demonstrated that circ-NOL10 inhibits breast cancer cell progression. Mechanistic studies indicated that MTDH and CASC3 converge at downregulating circ-NOL10 to release a set of three miRNAs. Competitive binding with the three miRNAs, in turn, blocks expression of the target gene PDCD4. Then decreased PDCD4 inhibits apoptosis and promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion (Figure 8). Thus, circ-NOL10 plays a central role in linking the upstream stimuli with downstream effectors in the RBP-ncRNA regulation network.

Figure 8.

Model of the RBP-ncRNA regulating network in breast cancer

Altered MTDH and CASC3 bind and repress circ-NOL10, which further releases a set of three miRNAs. miRNAs bind to the target gene PDCD4 to inhibit its expression, promoting proliferation, migration, and invasion and decreasing apoptosis in breast cancer cells.

Accumulated evidence has shown correlations between circRNA expression and clinicopathological parameters such as tumor size, OS time, and tumor staging in various cancers.13,24,25 Notably, our study found that expression of circ-NOL10 is significantly lower in breast cancer, especially in the LA and TNBC subtypes. Based on a large cohort of individuals with TNBC, we have shown that circ-NOL10 expression is correlated with clinical stage, lymphatic metastasis, recurrence, and survival. Downregulated circ-NOL10 is also associated with poor prognosis. Thus, circ-NOL10 can potentially be utilized as a promising diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for breast cancer.

Recently, a few RNA-binding proteins have been shown to control circRNA generation. For example, the splicing factor ESRP1 can interact with the flanking regions of circ-BIRC6-forming exons to promote formation of circ-BIRC6 in human embryonic stem cells.26 Another report found that ADAR1 mediates adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing to inhibit circRNA production.22,27 However, the proteins that drive the circRNA differential expression in breast cancer remain elusive. We found that circ-NOL10 is highly inhibited in all subtypes of breast cancer compared with normal tissue. Previous reports have also indicated that circ-NOL10 is expressed at low levels in breast, lung, and colorectal cancer.28, 29, 30 This agreement suggests that circ-NOL10 is a common player in carcinogenesis. Investigation in lung cancer also found that circ-NOL10 is regulated by the splicing factor ESRP1. Although ESRP1 is indeed a candidate, based on our bioinformatics analysis of its expression profile and genomic variations, the experimental results did not support its role in regulation (Figure S3A). This reflected the flexible mechanistic option when cells facing different circumstance. Instead, our integrative approach identified two RBPs, MTDH and CASC3, that regulate circ-NOL10 expression in breast cancer.

MTDH was first identified as a mediator responsible for breast-to-lung cancer metastasis.31 Compared with non-malignant tissues, it is expressed highly in many cancers, including breast, prostate, and liver cancer.32, 33, 34 Subsequently, MTDH has been demonstrated to coordinate multiple signaling pathways implicated in various aspects of carcinogenesis and become an attractive novel therapeutic target.35, 36, 37, 38 Limited biological function is known for CASC3 (also known as metastatic lymph node 51). It was first identified as core component of the exon junction complex.39 Previous studies have established that it resides in the chromosome 17q12–q21 region, where amplifications occur frequently.40 CASC3 overexpression has been found in breast cancer and fibroblast-like synoviocytes from individuals with rheumatoid arthritis.41,42 However, the role of CASC3 in breast cancer progression remains unclear. We found that these two RBPs bind and repress circ-NOL10, which is expressed at low levels in breast cancer. Thus, this investigation not only adds a novel ncRNA link to the many signaling pathways involving MTDH but also opens a new chapter for elucidating CASC3’s functional consequences.

This investigation of the regulation of circ-NOL10 and its biological functions and clinical implications in breast cancer should shed light on the circRNA-mediated mechanism in tumorigenesis.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

16 normal mammary gland tissues and 178 breast cancer tissues were used in this study, which have been described previously in detail.13

Cell culture

MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, T47D, BT20, BT549, SKBR3, MDA-MB-157, MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-436, MDA-MB-468, MCF-10A, and 293T cells were purchased from the ATCC and cultured under conditions recommended by the ATCC.

Oligos, plasmids, and transfection

siRNA oligonucleotides were designed and synthesized by GenePharma (Suzhou, China). miRNA mimics or inhibitors were designed and synthesized by IGEbio (Guangzhou, China) (sequences are listed in Table S4). To efficiently circularize a circRNA transcript in cells, the circ-NOL10-overexpressing plasmid was synthesized by Genechem (Shanghai, China). The overexpression plasmids pEZ-93-MTDH-FLAG, pEZ-93-CASC3-FLAG, pEZ-93-SRSF1-FLAG, pEZ-93- ESRP1-FLAG, pEZ-93-CWC15-FLAG, pEZ-M14-ADAR, and pEZ-M14-FUS were purchased from GeneCopoeia (Guangzhou, China). Cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured to 60%–70% confluence before transfection. Plasmids were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (catalog number L3000015, Invitrogen, USA), and siRNA miRNA mimics, inhibitors, or corresponding controls were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (catalog number 13778150, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

RNA extraction and qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For circRNA and mRNA analyses, cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara, Japan). Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex TaqII (Takara, Japan), and the reactions were subsequently measured on an ABI7500 PCR instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). GAPDH was applied as an internal standard control. For miRNA analyses, cDNA synthesis was performed with miRNA-specific stem-loop primers using a Quantscript RT Kit (Ibsbio, Guangzhou, China). SYBR Premix Ex TaqII (Takara, Japan) was used for transcript quantification with specific primers on a LightCycler 96 PCR instrument (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Primers were designed according to our previous study and are listed in Table S4.13

Protein isolation and western blot analyses

Cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (Biotechnology, China) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Switzerland). Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, MA, USA), incubated with 5% non-fat milk powder in TBST for 1 h at room temperature, and treated with specific primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Then the membrane was incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody, and each band was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Millipore, MA, USA) and visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) BioImaging system (Azure, USA). Anti-CCBE1 was purchased from Biorbyt (catalog number orb215381). Anti-GAPDH, anti-caspase-3, and anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (catalog numbers 2118S, 9663S, and 9661S, respectively). TUSC2 antibodies were purchased from Affinity Bioscience (catalog number AF0500). Anti-glutamate receptor 3/GRIA3[EP813Y] and anti-Bad were purchased from Abcam (catalog numbers ab40845 and ab40845, respectively). Anti-PDCD4 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog number sc-376430).

RNA FISH

FISH was performed as described previously in detail.13 Cy3-labeled probes specific to circ-NOL10 and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled probes specific to 18S (Geneseed, Guangzhou, China; Table S4) were used in the hybridization. Nuclei were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. The images were acquired on an Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope.

RIP assays

The RIP assays were performed using the Magna RIP RNA-Binding Protein Immuno-Precipitation Kit (Millipore, MA, USA). In brief, MDA-MB-231 cells were harvested when they reached 90%. 2 × 107 cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and resuspended in 100 μL of RIP lysis buffer combined with a protease inhibitor cocktail and RNase inhibitors. 100 μL cell lysate was incubated with beads coated with 5 μg of control mouse IgG or an antibody against CASC3 (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA) and an antibody against MTDH (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) or against FLAG with rotation at 4°C overnight. After the lysates were treated with proteinase K buffer, immunoprecipitated RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara, Japan). The abundance of circ-NOL10 was detected by qPCR. The immunoprecipitated RNAs were also sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system using the KAPA Stranded RNA-Seq Library Prep Kit (Illumina, USA). Motif analyses was conducted by TREME with default settings.43

Dual-luciferase reporter gene assay

The recombinant reporter plasmid (psiCHECK2_ Firefly_Luciferase-Renilla_Luciferase containing the circ-NOL10 sequence psiCHECK2-NOL10), reporters containing circ-NOL10-luc with mutated MTDH binding sites (Luc-circ-N-mut A and Luc-circ-N-mut B), and circNOL10-luc with a mutated CASC3 binding site (Luc-circ-N-mut C) were designed by IGEbio (Guangzhou, China). For the miRNA-circRNA interaction assay, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with the reporter plasmid and miR-149-5p, miR-330-3p, miR-452-5p mimic, or a negative control mimic and incubated for 24 h. For the RBP-circRNA interaction assay, cells were co-transfected with the reporter plasmid and MTDH or CASC3 overexpression plasmids and incubated for 48 h. Then luciferase activity was detected with a dual-luciferase reporter assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China).

IF-FISH co-localization assay

MDA-MB-231 cells were vaccinated in a confocal glass dish and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 min. After washing three times with permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min, cells were added anhydrous ethanol 1 min and dried in the air. Cells were added with a denatured hybridization probe (Cy3-labeled probes specific to circ-NOL10, denatured at 88°C for 5 min, equilibrated at 4°C for 3 min) and incubated overnight at 37°C in a hybridization chamber. The next day, cells were rinsed with 2 × saline sodium citrate (SSC) preheated at 42°C for 5 min, and then rinsed with 2 × SSC at room temperature for 5 min twice. Then cells were blocked with 2% goat serum for 10 min at room temperature and incubated with primary antibody (MTDH antibody, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA and CASC3 antibody, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA) overnight at 4°C. On the third day, cells were washed with PBS and then incubated with the corresponding Alexa 488-labeled secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, followed by staining the nucleus with DAPI. Fluorescence images were acquired using an Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope. The colocalization overlap coefficient was analyzed using Olympus FV3000 software.

Cellular assays

Wound healing assay

MDA-MB-231 cells and MCF-7 cell were cultured in 6-well plates and transfected with a circ-NOL10-overexpressing plasmid or a control vector. The injury line was made with a 200-μL pipette tip when a monolayer of cells was plated in culture dishes at 100% confluence. Images of cell migration were captured at 0 and 24 h for MDA-MB-231 cells or at 48 h for MCF-7 cells. An average of eight random width of injury line was measured for quantization and normalized to the 0 h control and expressed as a relative migration rate. The assays were repeated at least three times.

Colony formation assay

Transfected MDA-MB-231 or MCF-7 cells were plated in 6-well plates at a density of 400 cells per well. Then cells were cultured for 14 days to form visible colonies. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.5% crystal violet, and then colonies were imaged and counted. The experiment was replicated at least three times.

Cell proliferation assay

Each well of 2 × 103 cells was seeded in five copies on a 96-well plate after MDA-MB-231 or MCF-7 cells were transfected for 48 h. 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent (Yeasen, China) was added to each well at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The optical density at 450 nm was measured using an automatic microplate reader (Synergy4, BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). The experiment was repeated three times.

Matrigel invasion assay

Transfected cells were serum starved for 24 h, and 2 × 104 MDA-MB-231 or MCF-7 cells in 200 μL serum-free medium were seeded in the upper chamber pre-coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). 600 μL of complete medium was added to the lower chambers, and then the cells were incubated for 24 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. Invaded cells were counted in five random fields of view.

Apoptosis assay

Transfected cells were stained with PE/7-AAD (catalog number 557963, BD Biosciences, CA, USA) and incubated 15 min after trypsinization. Then treated cells were analyzed by a FACSCANTO II flow cytometer and FlowJo software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Lentiviruses and tumor xenograft model

All animal experimental protocols were approved by the animal care and use Committee of Guangdong Medical UniversityA green fluorescent (ZsGreen) tagged circ-NOL10 OE vector (Lv-circ-NOL10) and blank vector (Lv-circ-control) were constructed and packaged in lentiviruses (HanBio, Shanghai, China). 4-week-old female nude mice were purchased from GemPharmatech (Nanjing, China) and kept under controlled conditions. Mice were divided randomly into 2 groups, with 5 mice in each group. Lv-circ-NOL10 and Lv-circ-control were transfected into MDA-MB-231 cells. Then MDA-MB-231 cells (2 × 106 cells in 200 μL PBS solution) were inoculated subcutaneously into the left flanks of nude mice. The tumor volume was measured 1 week after injection and determined every 4 days, and the tumor volume (V = L × W2/2, L represents the longest diameter, and W represents the shortest diameter) was recorded each time. The mice were killed, and tumor tissue was removed for further research after 21 days.

Bioinformatics analysis

Potential miRNAs binding to circ-NOL10 are predicted by CircNet, CircInteractome, and Arraystar algorithms.44,45 We selected miRNAs that are expressed abundantly in breast cancer samples based on the miRGator database.46 To predict a potential regulator in cicRNA biogenesis, 1,344 RBP reported in previous literature were used for this analysis.47 Multiple omics data were downloaded from the cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/), which includes somatic mutation, copy number variations, and differential mRNA expression in 825 breast-invasive carcinoma samples. The proportion of samples that harbors at least one of the above alterations was calculated. Furthermore, we ran a log rank test for each RBP to assess the association between gene alteration and survival time with R package “survival.” RBPs that are altered in more than 10% of all cancer samples and correlated with survival (p < 0.1) are reported as potential circRNA regulators in breast cancer.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software with at least three independent experiments. The relationship between circ-NO10 expression and clinical features was analyzed by independent t test. ROC curve analyses were performed using Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad, USA). DFS and OS curves were drawn using the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression models were used to evaluate risk factors for breast cancer DFS and OS.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81673037 and 91859120) and the Start-Up Fund for High Talents from Xiang’an Hospital of Xiamen University (PM201809170013). We thank Dr. Stanley Lin for editing this manuscript.

Author contributions

J.X. and M.C. conceived the project and designed the experiments. Y.C., X.Z., Q.C., C.-C.S., Y.-X.O., J.F., and L.C. performed the experiments. X.Z. and F.Z. contributed to acquisition and analysis of clinical data. J.X. and D.C. developed the computational pipeline. J.X. and M.C. collected and interpreted the data. J.X. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2021.09.013.

Contributor Information

Min Chen, Email: mchen@xah.xmu.edu.cn.

Jianzhen Xu, Email: jzxu01@stu.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waks A.G., Winer E.P. Breast Cancer Treatment: A Review. JAMA. 2019;321:288–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X., Fang L. Advances in circular RNAs and their roles in breast Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;37:206. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0870-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao X., Cai Y., Xu J. Circular RNAs: Biogenesis, Mechanism, and Function in Human Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3926. doi: 10.3390/ijms20163926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeck W.R., Sorrentino J.A., Wang K., Slevin M.K., Burd C.E., Liu J., Marzluff W.F., Sharpless N.E. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA. 2013;19:141–157. doi: 10.1261/rna.035667.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Memczak S., Jens M., Elefsinioti A., Torti F., Krueger J., Rybak A., Maier L., Mackowiak S.D., Gregersen L.H., Munschauer M. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495:333–338. doi: 10.1038/nature11928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kristensen L.S., Andersen M.S., Stagsted L.V.W., Ebbesen K.K., Hansen T.B., Kjems J. The biogenesis, biology and characterization of circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019;20:675–691. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patop I.L., Wüst S., Kadener S. Past, present, and future of circRNAs. EMBO J. 2019;38:e100836. doi: 10.15252/embj.2018100836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang F., Zhao X., Dong H., Xu J. circRNA expression analysis in lung adenocarcinoma: comparison of paired fresh frozen and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;500:738–743. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.04.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahn J.H., Zhang Q., Li F., Chan T.M., Lin X., Kim Y., Wong D.T., Xiao X. The landscape of microRNA, Piwi-interacting RNA, and circular RNA in human saliva. Clin. Chem. 2015;61:221–230. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.230433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y., Zheng Q., Bao C., Li S., Guo W., Zhao J., Chen D., Gu J., He X., Huang S. Circular RNA is enriched and stable in exosomes: a promising biomarker for cancer diagnosis. Cell Res. 2015;25:981–984. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng K., He B., Yang B.B., Xu T., Chen X., Xu M., Liu X., Sun H., Pan Y., Wang S. The pro-metastasis effect of circANKS1B in breast cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2018;17:160. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0914-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J.Z., Shao C.C., Wang X.J., Zhao X., Chen J.Q., Ouyang Y.X., Feng J., Zhang F., Huang W.H., Ying Q. circTADA2As suppress breast cancer progression and metastasis via targeting miR-203a-3p/SOCS3 axis. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:175. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1382-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen B., Wei W., Huang X., Xie X., Kong Y., Dai D., Yang L., Wang J., Tang H., Xie X. circEPSTI1 as a Prognostic Marker and Mediator of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Progression. Theranostics. 2018;8:4003–4015. doi: 10.7150/thno.24106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren S., Liu J., Feng Y., Li Z., He L., Li L., Cao X., Wang Z., Zhang Y. Knockdown of circDENND4C inhibits glycolysis, migration and invasion by up-regulating miR-200b/c in breast cancer under hypoxia. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38:388. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1398-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Q., Zhu J., Wang Y.W., Dai Y., Wang Y.L., Wang C., Liu J., Baker A., Colburn N.H., Yang H.S. Tumor suppressor Pdcd4 attenuates Sin1 translation to inhibit invasion in colon carcinoma. Oncogene. 2017;36:6225–6234. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santhanam A.N., Baker A.R., Hegamyer G., Kirschmann D.A., Colburn N.H. Pdcd4 repression of lysyl oxidase inhibits hypoxia-induced breast cancer cell invasion. Oncogene. 2010;29:3921–3932. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuhashi S., Manirujjaman M., Hamajima H., Ozaki I. Control Mechanisms of the Tumor Suppressor PDCD4: Expression and Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2304. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meric-Bernstam F., Chen H., Akcakanat A., Do K.A., Lluch A., Hennessy B.T., Hortobagyi G.N., Mills G.B., Gonzalez-Angulo A. Aberrations in translational regulation are associated with poor prognosis in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R138. doi: 10.1186/bcr3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Z., Yuan Y.C., Wang Y., Liu Z., Chan H.J., Chen S. Down-regulation of programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) is associated with aromatase inhibitor resistance and a poor prognosis in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015;152:29–39. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3446-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng H., Wang K., Chen X., Guan X., Hu L., Xiong G., Li J., Bai Y. MicroRNA-330-3p functions as an oncogene in human esophageal cancer by targeting programmed cell death 4. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015;5:1062–1075. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivanov A., Memczak S., Wyler E., Torti F., Porath H.T., Orejuela M.R., Piechotta M., Levanon E.Y., Landthaler M., Dieterich C., Rajewsky N. Analysis of intron sequences reveals hallmarks of circular RNA biogenesis in animals. Cell Rep. 2015;10:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Errichelli L., Dini Modigliani S., Laneve P., Colantoni A., Legnini I., Capauto D., Rosa A., De Santis R., Scarfò R., Peruzzi G. FUS affects circular RNA expression in murine embryonic stem cell-derived motor neurons. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14741. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen B., Huang S. Circular RNA: An emerging non-coding RNA as a regulator and biomarker in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018;418:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kristensen L.S., Hansen T.B., Venø M.T., Kjems J. Circular RNAs in cancer: opportunities and challenges in the field. Oncogene. 2018;37:555–565. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu C.Y., Li T.C., Wu Y.Y., Yeh C.H., Chiang W., Chuang C.Y., Kuo H.C. The circular RNA circBIRC6 participates in the molecular circuitry controlling human pluripotency. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1149. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01216-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rybak-Wolf A., Stottmeister C., Glažar P., Jens M., Pino N., Giusti S., Hanan M., Behm M., Bartok O., Ashwal-Fluss R. Circular RNAs in the Mammalian Brain Are Highly Abundant, Conserved, and Dynamically Expressed. Mol. Cell. 2015;58:870–885. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nan A., Chen L., Zhang N., Jia Y., Li X., Zhou H., Ling Y., Wang Z., Yang C., Liu S., Jiang Y. Circular RNA circNOL10 Inhibits Lung Cancer Development by Promoting SCLM1-Mediated Transcriptional Regulation of the Humanin Polypeptide Family. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 2018;6:1800654. doi: 10.1002/advs.201800654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang F., Wang X., Li J., Lv P., Han M., Li L., Chen Z., Dong L., Wang N., Gu Y. CircNOL10 suppresses breast cancer progression by sponging miR-767-5p to regulate SOCS2/JAK/STAT signaling. J. Biomed. Sci. 2021;28:4. doi: 10.1186/s12929-020-00697-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y., Zhang Z., Yi Y., Wang Y., Fu J. CircNOL10 Acts as a Sponge of miR-135a/b-5p in Suppressing Colorectal Cancer Progression via Regulating KLF9. OncoTargets Ther. 2020;13:5165–5176. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S242001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown D.M., Ruoslahti E. Metadherin, a cell surface protein in breast tumors that mediates lung metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:365–374. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thirkettle H.J., Girling J., Warren A.Y., Mills I.G., Sahadevan K., Leung H., Hamdy F., Whitaker H.C., Neal D.E. LYRIC/AEG-1 is targeted to different subcellular compartments by ubiquitinylation and intrinsic nuclear localization signals. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:3003–3013. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tokunaga E., Nakashima Y., Yamashita N., Hisamatsu Y., Okada S., Akiyoshi S., Aishima S., Kitao H., Morita M., Maehara Y. Overexpression of metadherin/MTDH is associated with an aggressive phenotype and a poor prognosis in invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2014;21:341–349. doi: 10.1007/s12282-012-0398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robertson C.L., Mendoza R.G., Jariwala N., Dozmorov M., Mukhopadhyay N.D., Subler M.A., Windle J.J., Lai Z., Fisher P.B., Ghosh S., Sarkar D. Astrocyte Elevated Gene-1 Regulates Macrophage Activation in Hepatocellular Carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2018;78:6436–6446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan L., Lu X., Yuan S., Wei Y., Guo F., Shen M., Yuan M., Chakrabarti R., Hua Y., Smith H.A. MTDH-SND1 interaction is crucial for expansion and activity of tumor-initiating cells in diverse oncogene- and carcinogen-induced mammary tumors. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu G., Wei Y., Kang Y. The multifaceted role of MTDH/AEG-1 in cancer progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:5615–5620. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srivastava J., Robertson C.L., Rajasekaran D., Gredler R., Siddiq A., Emdad L., Mukhopadhyay N.D., Ghosh S., Hylemon P.B., Gil G. AEG-1 regulates retinoid X receptor and inhibits retinoid signaling. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4364–4377. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang Y., Hu J., Li J., Liu Y., Yu J., Zhuang X., Mu L., Kong X., Hong D., Yang Q., Hu G. Epigenetic Activation of TWIST1 by MTDH Promotes Cancer Stem-like Cell Traits in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3672–3680. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bono F., Ebert J., Lorentzen E., Conti E. The crystal structure of the exon junction complex reveals how it maintains a stable grip on mRNA. Cell. 2006;126:713–725. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arriola E., Marchio C., Tan D.S., Drury S.C., Lambros M.B., Natrajan R., Rodriguez-Pinilla S.M., Mackay A., Tamber N., Fenwick K. Genomic analysis of the HER2/TOP2A amplicon in breast cancer and breast cancer cell lines. Lab. Invest. 2008;88:491–503. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Degot S., Régnier C.H., Wendling C., Chenard M.P., Rio M.C., Tomasetto C. Metastatic Lymph Node 51, a novel nucleo-cytoplasmic protein overexpressed in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21:4422–4434. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jang J., Lim D.S., Choi Y.E., Jeong Y., Yoo S.A., Kim W.U., Bae Y.S. MLN51 and GM-CSF involvement in the proliferation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2006;8:R170. doi: 10.1186/ar2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bailey T.L. DREME: motif discovery in transcription factor ChIP-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1653–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dudekula D.B., Panda A.C., Grammatikakis I., De S., Abdelmohsen K., Gorospe M. CircInteractome: A web tool for exploring circular RNAs and their interacting proteins and microRNAs. RNA Biol. 2016;13:34–42. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1128065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y.C., Li J.R., Sun C.H., Andrews E., Chao R.F., Lin F.M., Weng S.L., Hsu S.D., Huang C.C., Cheng C. CircNet: a database of circular RNAs derived from transcriptome sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D209–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cho S., Jang I., Jun Y., Yoon S., Ko M., Kwon Y., Choi I., Chang H., Ryu D., Lee B. MiRGator v3.0: a microRNA portal for deep sequencing, expression profiling and mRNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D252–D257. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neelamraju Y., Hashemikhabir S., Janga S.C. The human RBPome: from genes and proteins to human disease. J. Proteomics. 2015;127(Pt A):61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.