Abstract

Purpose

Treatment with long-term androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and radiation therapy (RT) is the nonsurgical standard-of-care for patients with high- or very high-risk prostate cancer (HR-PC), but the optimal timing between ADT and RT initiation is unknown. We evaluate the influence of timing between ADT and RT on outcomes in patients with HR-PC using a large national cancer database.

Methods and Materials

Data for patients with clinical T1-T4 N0, M0, National Cancer Comprehensive Network HR-PC who were treated with definitive external RT (≥60 Gy) and ADT starting either before or within 14 days after RT start were extracted from the National Cancer Database (2004-2015). Patients were grouped on the basis of ADT initiation: (1) >11 weeks before RT, (2) 8 to 11weeks before RT, and (3) <8 weeks before RT. Kaplan-Meier, propensity score matching, and multivariable Cox proportional hazards were performed to evaluate overall survival (OS).

Results

With a median follow-up of 68.9 months, 37,606 patients with HR-PC were eligible for analysis: 13,346 (35.5%) with >11 weeks of neoadjuvant ADT, 11,456 (30.5%) with 8 to 11 weeks of neoadjuvant ADT; and 12,804 (34%) patients with <8 weeks of neoadjuvant ADT. The unadjusted 10-year OS rates for >11 weeks, 8 to 11 weeks, and <8 weeks neoadjuvant ADT groups were 49.9%, 51.2%, and 46.9%, respectively (P = .002). On multivariable and inverse probability of treatment weighting analyses, there was a significant OS advantage for patients in the 8 to 11 weeks neoadjuvant ADT group (adjusted hazard ratio 0.90; 95% confidence interval, 0.86-0.95; P < .001) but not the >11 weeks group.

Conclusions

Neoadjuvant ADT initiation 8 to 11 weeks before RT is associated with significantly improved OS compared with shorter neoadjuvant ADT duration. Although prospective validation is warranted, this analysis is the largest retrospective study suggesting an influence of timing between ADT and RT initiation in HR-PC.

Introduction

Radiation therapy (RT) with androgen deprivation (ADT) is the nonsurgical standard of care for patients with high or very high-risk localized prostate cancer (HR-PC).1 Multiple trials have demonstrated improvements in overall survival (OS) with the addition of ADT to RT,2,3 even in the dose-escalated era.4 However, the timing of ADT initiation among trials has been heterogeneous, using neoadjuvant ADT, concurrent, or even adjuvant ADT initiation.

Few studies have directly addressed this timing. In a randomized trial of neoadjuvant versus adjuvant ADT, Malone et al5 reported equivocal results for biochemical relapse-free survival (BRFS) between groups. However, 95% of patients had intermediate-risk rather than HR-PC, the biology of which is fundamentally more indolent and less affected by ADT.6 In another phase 3 trial randomizing patients to either 3 or 8 months of neoadjuvant ADT, neooadjuvant ADT duration did not affect BRFS, but only 31% of patients had HR-PC.7 One population-based analysis reported improved OS among patients with HR-PC treated with neoadjuvant compared with concurrent ADT, implying that timing of ADT initiation does indeed affect disease outcomes.8 In the Radiation Oncology Group (RTOG) 9413 trial, which included more HR-PC patients, those treated with whole-pelvis RT had improved BRFS with neoadjuvant ADT, but ADT timing had no effect among patients treated with prostate-only RT.9 This precluded definitive conclusions regarding the temporal influence of ADT on oncologic outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has reinvigorated the debate on whether and how temporal differences in ADT and RT delivery affects HR-PC outcomes. Oncologists are now compelled to weigh the risks of delaying RT against those of potential iatrogenic exposures with treatment.10 Recently, a National Cancer Database Analysis (NCDB) by Dee et al found no differences in OS between HR-PC patients treated with ADT that was initiated at 0 to 60, 61 to 120, and 121 to 180 days before RT.11 Herein, we describe the influence of the timing of neoadjuvant ADT initiation on OS and identify a precise, clinically relevant timeframe its initiation before RT in patients with HR-PC.

Methods and Materials

Patient cohorts

The study sample was extracted from the NCDB, which collects data from more than 1500 Commission On Cancer–accredited facilities.12 The NCDB was queried for patients with a first and only cancer diagnosis of localized, node-negative HR-PC, as defined by NCCN guidelines,1 treated with curative-intent RT (≥60 Gy),13 and ADT that was initiated either before RT or ≤14 days after the start of the RT start date. Patients missing ADT or risk stratification data and those who received brachytherapy, surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or palliative-intent therapy were excluded.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 with macros developed by the Biostatistics Shared Resource at Winship Cancer Institute.14 Descriptive statistics for each variable were reported. Association between variables of interest and the study cohort were examined using χ2 for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. The association with OS was modeled by the Cox proportional hazards model, and the multivariable models were built using a backward variable selection procedure with an alpha = 0.05 removal criteria. The <8 weeks neoadjuvant ADT group served as the reference group. The interval between ADT and RT was initially divided into 6 cut-off values that maximized the discriminative ability for OS in terms of the highest bias-corrected C-index15 with subsequent consolidation into 3 groups.

The inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) method was implemented to balance patient baseline characteristics.16 A logistic regression model was used to estimate the probabilities that a patient would receive any one of the 3-level time-interval based on their baseline covariates that also predict OS. The balance of covariates was evaluated by the standardized differences, and value of <0.1 was considered as negligible imbalance (Fig. E1).

Results

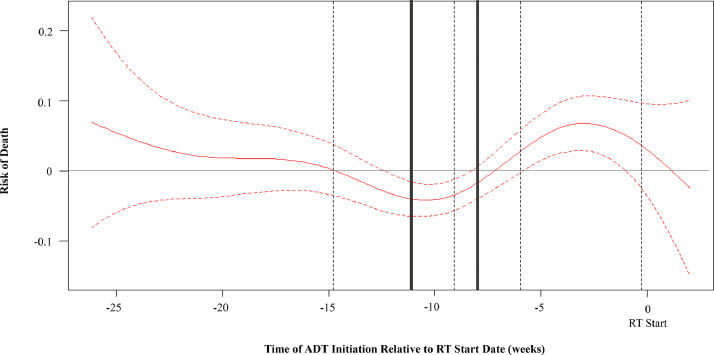

Between 2004 to 2016, 14,911,140 cases of prostate cancer were identified in the NCDB with 37,606 patients meeting our inclusion criteria. To identify time points of ADT initiation relative to RT and their influence on OS, we plotted Martingale residuals of OS as a nonlinear function of time between ADT and RT (Fig. 1), revealing 6 optimal discriminatory time points between ADT initiation and RT. These were then consolidated into 3 groups for statistical power and clinical applicability: <8 weeks (n = 12,804), 8 to 11 weeks (11,456), and >11 weeks (13,346).7 As shown in Fig. 1, there was a clear valley in the curve corresponding to the 8 to 11 week timeframe.

Fig. 1.

A nonlinear relationship between the risk of death (Martingale residuals) and the number of weeks between androgen deprivation therapy and radiation therapy initiation. Zero corresponds to the date of radiation therapy initiation. We identified 6 optimal, discriminatory time points (dotted and solid gray lines) in predicting overall survival. These were then consolidated into three groups (<8 weeks, 8-11 weeks, and >11 weeks [solid gray lines]).

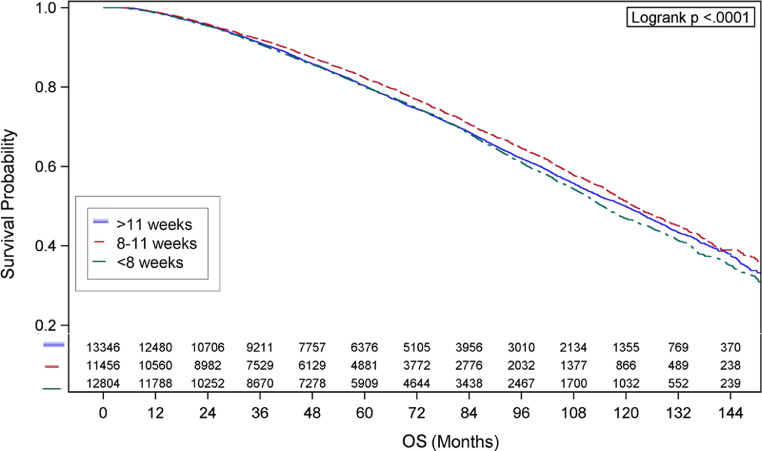

Descriptive characteristics are shown in Table 1. Median radiation doses were 77.4 Gy for each group (P = .379). Kaplan-Meier curves for OS are shown in Fig. 2, which demonstrated median survival of 114.7 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 112.6%-116.9%) for the <8 weeks group, 121.8 months (95% CI, 119.2%-125.2%) for the 8 to 11 weeks group, and 119.8 months (95% CI, 117.2%-122.7%) for the >11 weeks group (P < .001). Additional characteristics associated with univariate survival are shown (Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Characteristic | <8 wk N = 12,804 | 8-11 wk N = 11,456 | >11 wk N = 13,346 | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ≤65 | 3456 (27) | 3110 (27.1) | 3610 (27) | .963 |

| >65 | 9348 (73) | 8346 (72.9) | 9736 (73) | ||

| Race | White | 10,102 (78.9) | 9030 (78.8) | 10279 (77) | <.001 |

| Black | 2229 (17.4) | 1990 (17.4) | 2456 (18.4) | ||

| Other | 473 (3.7) | 436 (3.8) | 611 (4.6) | ||

| Median income quartiles 2008-2012 | <$38,000 | 2728 (21.4) | 1999 (17.5) | 2445 (18.4) | <.001 |

| $38,000-$47,999 | 3156 (24.8) | 2748 (24.1) | 3088 (23.3) | ||

| $48,000-$62,999 | 3351 (26.3) | 3043 (26.7) | 3540 (26.7) | ||

| ≥$63,000 | 3514 (27.6) | 3622 (31.7) | 4201 (31.6) | ||

| High school degree 2008-2012 (%) | ≥21.0% | 2123 (16.6) | 1848 (16.2) | 2290 (17.2) | <.001 |

| 13.0-2.9% | 3613 (28.3) | 2916 (25.5) | 3476 (26.2) | ||

| 7.0-12.9% | 4191 (32.9) | 3861 (33.8) | 4383 (33) | ||

| <7.0% | 2825 (22.2) | 2799 (24.5) | 3136 (23.6) | ||

| Primary payor | Other government/not insured/unknown | 1227 (9.6) | 1128 (9.8) | 1498 (11.2) | <.001 |

| Private | 3206 (25) | 2983 (26) | 3322 (24.9) | ||

| Medicare | 8371 (65.4) | 7345 (64.1) | 8526 (63.9) | ||

| Facility type | Community cancer program | 1586 (12.4) | 1027 (9) | 1352 (1.1) | <.001 |

| Comprehensive community cancer program | 6049 (47.2) | 5282 (46.1) | 6243 (46.8) | ||

| Academic/research program | 3499 (27.3) | 3708 (32.4) | 4087 (3.6) | ||

| Integrated network cancer program | 1670 (13) | 1439 (12.6) | 1663 (12.5) | ||

| Year of diagnosis | 2004-2006 | 2673 (2.9) | 2013 (17.6) | 3161 (23.7) | <.001 |

| 2007-2009 | 3187 (24.9) | 2503 (21.8) | 3365 (25.2) | ||

| 2010-2012 | 3372 (26.3) | 3044 (26.6) | 3191 (23.9) | ||

| 2013-2015 | 3572 (27.9) | 3896 (34) | 3629 (27.2) | ||

| Charlson-Deyo score | 0 | 10,831 (84.6) | 9662 (84.3) | 11,269 (84.4) | .064 |

| 1 | 1578 (12.3) | 1394 (12.2) | 1582 (11.9) | ||

| 2+ | 395 (3.1) | 400 (3.5) | 495 (3.7) | ||

| Grade | Well differentiated, differentiated, NOS | 78 (.6) | 68 (.6) | 87 (.7) | .005 |

| Moderately differentiated, moderately well differentiated, intermediate differentiation | 1178 (9.2) | 1041 (9.1) | 1361 (1.2) | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 11,017 (86) | 9873 (86.2) | 11,402 (85.4) | ||

| Undifferentiated, anaplastic | 165 (1.3) | 118 (1) | 121 (.9) | ||

| Cell type not determined, not stated or not applicable, unknown primaries, high-grade dysplasia | 366 (2.9) | 356 (3.1) | 375 (2.8) | ||

| Clinical T stage | T1 | 5905 (46.1) | 4937 (43.1) | 5793 (43.4) | <.001 |

| T2 | 5024 (39.2) | 4639 (4.5) | 5190 (38.9) | ||

| T3-4 | 1875 (14.6) | 1880 (16.4) | 2363 (17.7) | ||

| PSA (ng/mL) | <10 | 5475 (43.3) | 4830 (42.6) | 5077 (38.5) | <.001 |

| 10-20 | 2536 (2.1) | 2372 (2.9) | 2646 (2.1) | ||

| >20 | 4625 (36.6) | 4143 (36.5) | 5448 (41.4) | ||

| Gleason score | 2-6 | 537 (4.3) | 434 (3.8) | 661 (5.1) | <.001 |

| 7 | 2131 (16.9) | 1942 (17.2) | 2488 (19) | ||

| 8-10 | 9928 (78.8) | 8937 (79) | 9937 (75.9) | ||

| Percent biopsy cores positive | Median (IQR) | 58.3 (36.4-83.3) | 58.3 (33.3-83.3) | 58.8 (40-91.7) | <.001 |

| Radiation dose (Gy) | Median (IQR) | 77.4 (75.6-79.2) | 77.4 (75.6-79.2) | 77.4 (75.6-79.2) | .379 |

Abbreviations: IQR = interquartile range; PSA = prostate specific antigen.

The parametric P value is calculated by analysis of variance for numerical covariates and χ2 test for categorical covariates. All values are displayed as N (percent) unless otherwise specified as median (interquartile range).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves are shown for patients in whom androgen deprivation therapy had been initiated <8 weeks, 8 to 11 weeks, and >11 weeks prior to radiation therapy are shown.

Table 2.

Univariate association with overall survival

| Covariate | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time between ADT and RT initiation | <8 wk | - | - |

| 8-11 wk | 0.89 (0.84-0.93) | <.001 | |

| >11 wk | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | .090 | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | ≤65 | 0.59 (0.56-0.62) | <.001 |

| >65 | - | - | |

| Race | White | 1.35 (1.21-1.51) | <.001 |

| Black | 1.20 (1.06-1.35) | .003 | |

| Other | - | - | |

| Median income quartiles 2008-2012 | <$38,000 | 1.20 (1.13-1.27) | <.001 |

| $38,000-$47,999 | 1.24 (1.18-1.31) | <.001 | |

| $48,000-$62,999 | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | <.001 | |

| ≥$63,000 | - | - | |

| Percent no high school degree 2008-2012 | ≥21.0% | 1.13 (1.06-1.20) | <.001 |

| 13.0%-20.9% | 1.15 (1.09-1.22) | <.001 | |

| 7.0%-12.9% | 1.10 (1.04-1.16) | <.001 | |

| <7.0% | - | - | |

| Primary payor | Other government/not insured/unknown | 0.84 (0.78-0.90) | <.001 |

| Private | 0.63 (0.60-0.66) | <.001 | |

| Medicare | - | - | |

| Facility type | Community cancer program | 1.13 (1.04-1.23) | .003 |

| Comprehensive community cancer program | 1.09 (1.03-1.16) | .005 | |

| Academic/research program | 0.91 (0.85-0.98) | .009 | |

| Integrated network cancer program | - | - | |

| Year of diagnosis | 2004-2006 | 0.94 (0.87-1.02) | .162 |

| 2007-2009 | 0.97 (0.90-1.06) | .532 | |

| 2010-2012 | 0.98 (0.90-1.07) | .700 | |

| 2013-2015 | - | - | |

| Charlson-Deyo score | 0 | 0.50 (0.45-0.55) | <.001 |

| 1 | 0.69 (0.62-0.77) | <.001 | |

| 2 + | - | - | |

| Grade | Well differentiated, differentiated, NOS | 0.84 (0.57-1.24) | .382 |

| Moderately differentiated, moderately well differentiated, intermediate differentiation | 0.74 (0.63-0.88) | <.001 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 1.04 (0.89-1.21) | .614 | |

| Undifferentiated, anaplastic | 1.18 (0.95-1.47) | .124 | |

| Cell type not determined, not stated or not applicable, unknown primaries, high-grade dysplasia | - | - | |

| Clinical T stage | T1 | 0.89 (0.84-0.94) | <.001 |

| T2 | 0.99 (0.94-1.04) | .686 | |

| T3-4 | - | - | |

| PSA (ng/mL) | <10 | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | .054 |

| 10-20 | 1.20 (1.14-1.27) | <.001 | |

| >20 | - | - | |

| Gleason | 2-6 | 0.59 (0.54-0.66) | <.001 |

| 7 | 0.78 (0.74-0.82) | <.001 | |

| 8-10 | - | - | |

| Biopsy cores positive | <50% | 0.74 (0.67-0.81) | <.001 |

| ≥50% | - | - | |

| Radiation dose (Gy) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | .280 |

Abbreviations: ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; NOS = not otherwise specified; PSA = prostate specific antigen; RT = radiation therapy.

*The parametric P value is calculated by analysis of variance for numerical covariates and χ2 test for categorical covariates. All values are displayed as N (percent) unless otherwise specified as median (interquartile range).

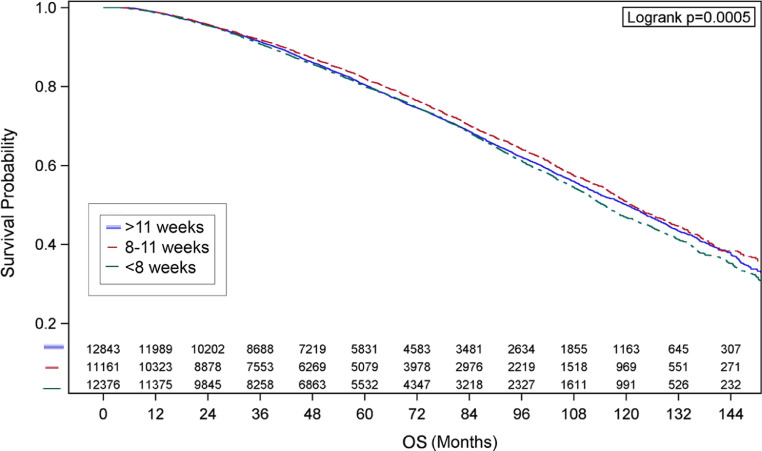

Neoadjuvant ADT initiation 8 to 11 weeks before RT remained significantly associated with an OS advantage on the multivariable analysis (HR 0.90; 95% CI, 0.86%-0.95%) compared with the <8 week group (Table 3). Similar results were found when stratifying the multivariate analysis by doses of <76 Gy compared with ≥76 Gy (Table E2). On IPTW analysis, there were 12,843 patients in the >11 weeks group, 11,162 patients in the 8 to 11 week group, and 12,376 patients in the <8 weeks group. Kaplan-Meier plots are shown in Figure 3. Patients in the 8 to 11 week group had a significantly longer OS (HR: 0.90; 95% CI, 0.86%-0.95%; P < .001) compared with the <8 weeks group. The >11 weeks group did not reach significance but trended in the same direction (HR: 0.96; 95% CI, 0.91%-1.01%; P = .082). The IPTW method generated almost the same HR as that in the multivariable analysis, indicative of balance of covariates before analysis.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis for overall survival

| Covariate | HR (95% CI) | HR P value | Type 3 P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time between ADT and RT initiation | <8 wk | - | - | <.001 |

| 8-11 wk | 0.90 (0.86-0.95) | <.001 | ||

| >11 wk | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | 0.104 | ||

| Age at diagnosis, y | ≤65 | 0.66 (0.62-0.70) | <.001 | <.001 |

| >65 | - | - | ||

| Race | White | 1.23 (1.09-1.38) | <.001 | .002 |

| Black | 1.19 (1.05-1.35) | 0.007 | ||

| Other | - | - | ||

| Median income quartiles 2008-2012 | <$38,000 | 1.18 (1.11-1.26) | <.001 | <.001 |

| $38,000-$47,999 | 1.18 (1.11-1.24) | <.001 | ||

| $48,000-$62,999 | 1.07 (1.01-1.13) | 0.022 | ||

| ≥$63,000 | - | - | ||

| Primary payor | Other government/not insured | 1.04 (0.96-1.13) | 0.313 | <.001 |

| Private | 0.79 (0.75-0.84) | <.001 | ||

| Medicare | - | - | ||

| Facility type | Community cancer program | 1.07 (0.99-1.16) | 0.105 | <.001 |

| Comprehensive community cancer program | 1.02 (0.96-1.09) | 0.514 | ||

| Academic/research program | 0.93 (0.86-0.99) | 0.030 | ||

| Integrated network cancer program | - | - | ||

| Charlson-Deyo score | 0 | 0.51 (0.46-0.57) | <.001 | <.001 |

| 1 | 0.68 (0.60-0.75) | <.001 | ||

| 2+ | - | - | ||

| Clinical T stage | T1 | 0.80 (0.76-0.85) | <.001 | <.001 |

| T2 | 0.87 (0.82-0.92) | <.001 | ||

| T3-4 | - | - | ||

| PSA | <10 | 0.75 (0.71-0.79) | <.001 | <.001 |

| 10-20 | 0.94 (0.89-1.00) | 0.034 | ||

| >20 | - | - | ||

| Gleason | 2-6 | 0.53 (0.48-0.59) | <.001 | <.001 |

| 7 | 0.70 (0.66-0.75) | <.001 | ||

| 8-10 | - | - |

Abbreviations: ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; HR = hazard ratio; PSA = prostate specific antigen; RT = radiation therapy.

Number of observations in the original data set = 37,606. Number of observations used = 36,384.

Backward selection with an alpha level of removal of.05 was used. The following variables were removed from the model: grade, percent no high school degree 2008 to 2012, and year of diagnosis.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves are shown for are shown for patients in whom androgen deprivation therapy had been initiated <8 weeks, 8-11 weeks, and >11 weeks prior to radiation therapy are shown using the inverse probability of treatment weighting method.

Discussion

Despite the well-defined role of long-term ADT for patients with HR-PC treated with definitive RT, consensus on the optimal timing of ADT delivery relative to RT remains unclear. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, knowing whether and how long to delay RT after ADT initiation is critical. Our findings demonstrated improved OS among patients who began ADT at 8 to 11 weeks before RT relative to shorter neoadjuvant ADT duration. This association remained significant in both multivariable and IPTW analyses.

The benefit of neoadjuvant compared with adjuvant ADT initiation is well-documented in animal models and may be related to cytoreduction.17 However, among patients with HR-PC, a temporal effect of ADT delivery has been less clear. In the RTOG 9413 trial, neoadjuvant ADT initiation benefited patients treated with whole-pelvic RT but not prostate-only RT.9 A recent meta-analysis of the patients treated with prostate-only RT from the RTOG 9413 and Ottawa 0101 trials found improved metastasis-free survival with concurrent ADT initiation compared with neoadjuvant ADT initiation.18 Given that this analysis excluded patients receiving pelvic nodal irradiation, the discrepancy with our findings may be related to the effect of treatment volumes on the optimal timing of ADT initiation, as suggested by RTOG 9413.9 Furthermore, ADT duration among all patients in this meta-analysis was 6 months, making these data less generalizable to a modern HR-PC cohort.18

Dee et al have recently published their NCDB analysis of the effect of timing of ADT initiation in intermediate and HR-PC patients in the 2004 to 2014 data set treated with RT,11 reporting no differences in OS between patients who started ADT 0 to 60, 61 to 120, and 121 to 180 days before RT. Our study included NCDB data between 2004 to 2015 and explicitly excluded patients treated with <60 Gy to prevent the inclusion of patients who treated with palliative intent. Our analysis avoided the assumption that there would be either a linear association between the timing of ADT delivery or that arbitrary, predefined timeframes of ADT initiation would demonstrate differences in outcomes. This advanced, unbiased statistical approach ultimately led to the identification of an optimal window of ADT initiation as 8 to 11 weeks before RT delivery, as shown in Figure 1. Additional study of the optimal timing of ADT initiation should consider the timing of neoadjuvant ADT on a spectrum rather than a categorical variable (ie, adjuvant vs neoadjuvant).

Our analysis is subject to limitations. First, its design is subject to the well-known limitations of NCDB studies, including unobserved cofounders. Long-term ADT became standard-of-care during the study period in HR-PC patients, and ADT duration is not collected in the NCDB, which remains a major limitation.3,6,19 Likewise, PSA values are not recorded after the initial value, preventing analysis of PSA response to neaoadjuvant ADT, which has been shown to highly prognostic.20 Finally, treatment volumes and fractionation were not reliably collected in the NDCB, which could also affect our results.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study is the first to identify a nonlinear relationship between the timing of ADT initiation before RT in patients with HR-PC. Our results argue for additional randomized trials to assess the optimal timing of ADT initiation in patients with HR-PC.

Conclusions

Neoadjuvant ADT initiation 8 to 11 weeks before RT is associated with improved OS compared with shorter neoadjuvant ADT duration. Although prospective validation is warranted, this is the largest study showing an influence of timing between ADT and RT initiation in HR-PC.

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The data used in the study are derived from a deidentified National Cancer Database Analysis file. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for the analytical or statistical methodology used, or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigator.

Footnotes

Sources of Support: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Biostatistics Shared Resource of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and National Institute of Health/National Cancer Instituite (NIH/NCI) under award number P30CA138292.

Disclosures: Dr Jani reports personal fees from Blue Earth Diagnostics, which is outside the scope of this present work.

Research data are publicly available through the National Cancer Database.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.adro.2021.100803.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Prostate cancer. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2020.

- 2.Roach M, Bae K, Speight J. Short-term neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy and external-beam radiotherapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: long-term results of RTOG 8610. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:585–591. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolla M, Van Tienhoven G, Warde P. External irradiation with or without long-term androgen suppression for prostate cancer with high metastatic risk: 10-year results of an EORTC randomised study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1066–1073. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolla M, Maingon P, Carrie C. Short androgen suppression and radiation dose escalation for intermediate- and high-risk localized prostate cancer: Results of EORTC Trial 22991. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1748–1756. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malone S, Roy S, Eapen L. Sequencing of androgen-deprivation therapy with external-beam radiotherapy in localized prostate cancer: A phase III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:593–601. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisansky TM, Hunt D, Gomella LG. Duration of androgen suppression before radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: Radiation therapy oncology group randomized clinical trial 9910. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:332–339. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.0662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crook J, Ludgate C, Malone S. Final report of multicenter Canadian phase III randomized trial of 3 versus 8 months of neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy before conventional-dose radiotherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee A, Becker DJ, Lederman AJ. Comparison of neoadjuvant vs concurrent/adjuvant androgen deprivation in men with high-risk prostate cancer receiving definitive radiation therapy. Tumori. 2017;103:387–393. doi: 10.5301/tj.5000595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roach M, Moughan J, Lawton CAF. Sequence of hormonal therapy and radiotherapy field size in unfavourable, localised prostate cancer (NRG/RTOG 9413): Long-term results of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1504–1515. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30528-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaorsky NG, Yu JB, McBride SM. Prostate cancer radiotherapy recommendations in response to COVID-19. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020;5(Suppl 1):26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dee EC, Mahal BA, Arega MA. Relative timing of radiotherapy and androgen deprivation for prostate cancer and implications for treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1630–1632. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su C, Peng C, Agbodza E. Publication trend, resource utilization, and impact of the US National Cancer Database: A systematic review. Medicine. 2018;97:e9823. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. Part I: Risk stratification, shared decision making, and care options. J Urol. 2018;199:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Nickleach DC, Zhang C, Switchenko JM, Kowalski J. Carrying out streamlined routine data analyses with reports for observational studies: introduction to a series of generic SAS® macros. [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. F1000Res. 2018;7:1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Barrio I, Arostegui I, Rodríguez-Álvarez M-X, Quintana J-M. A new approach to categorising continuous variables in prediction models: Proposal and validation. Stat Methods Med Res. 2017;26:2586–2602. doi: 10.1177/0962280215601873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34:3661–3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zietman AL, Prince EA, Nakfoor BM, Park JJ. Androgen deprivation and radiation therapy: Sequencing studies using the Shionogi in vivo tumor system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:1067–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spratt DE, Malone S, Roy S. Prostate radiotherapy with adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) improves metastasis-free survival compared to neoadjuvant ADT: An individual patient meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:136–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denham JW, Joseph D, Lamb DS. Short-term androgen suppression and radiotherapy versus intermediate-term androgen suppression and radiotherapy, with or without zoledronic acid, in men with locally advanced prostate cancer (TROG 03.04 RADAR): 10-year results from a randomised, phase 3, factorial trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:267–281. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30757-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hallemeier CL, Zhang P, Pisansky TM. Prostate-specific antigen after neoadjuvant androgen suppression in prostate cancer patients receiving short-term androgen suppression and external beam radiation therapy: Pooled analysis of four NRG Oncology Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Randomized Clinical Trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;104:1057–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.