Abstract

Background

Global surgery has recently gained prominence as an academic discipline within global health. Authorship inequity has been a consistent feature of global health publications, with over-representation of authors from high-income countries (HICs), and disenfranchisement of researchers from low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). In this study, we investigated authorship demographics within recently published global surgery literature.

Methods

We performed a systematic analysis of author characteristics, including gender, seniority and institutional affiliation, for global surgery studies published between 2016 and 2020 and indexed in the PubMed database. We compared the distribution of author gender and seniority across studies related to different topics; between authors affiliated with HICs and LMICs; and across studies with different authorship networks.

Results

1240 articles were included for analysis. Most authors were male (60%), affiliated only with HICs (51%) and of high seniority (55% were fully qualified specialist or generalist clinicians, Principal Investigators, or in senior leadership or management roles). The proportion of male authors increased with increasing seniority for last and middle authors. Studies related to Obstetrics and Gynaecology had similar numbers of male and female authors, whereas there were more male authors in studies related to surgery (69% male) and Anaesthesia and Critical care (65% male). Compared with HIC authors, LMIC authors had a lower proportion of female authors at every seniority grade. This gender gap among LMIC middle authors was reduced in studies where all authors were affiliated only with LMICs.

Conclusion

Authorship disparities are evident within global surgery academia. Remedial actions to address the lack of authorship opportunities for LMIC authors and female authors are required.

Keywords: surgery, obstetrics, health services research, other study design

Key questions.

What is already known?

There is authorship inequity in global health academia, with over-representation of male authors and authors from high-income countries (HICs).

A bibliometric study of global surgery studies published between 1987 and 2017 showed that most authors in global surgery academia were affiliated with low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).

What are the new findings?

In recently published global surgery studies, the majority of authors are affiliated only with HICs.

There is a gender gap in global surgery authorship, which is greater at higher levels of seniority, and among LMIC authors.

The gender gap in middle authors from LMICs is greater in studies coauthored with HIC authors.

What do the new findings imply?

Authorship inequity is present in global surgery publications, with under-representation of LMIC authors and female authors.

Global surgery research collaborations between HIC and LMIC coauthors should be examined for practices contributing to gender inequity.

Introduction

Global health research aims to tackle health inequities worldwide, and low-income and middle-income country (LMIC) researchers are its major stakeholders.1 However, they find themselves under-represented in global health publications, especially in prominent first and last author positions, whereas high-income country (HIC) authors disproportionately dominate.2–4 Furthermore, gender inequity is present in global health academia even though 70% of global healthcare workforce in LMICs is made up of women.5 Such inequities have become central considerations as global health academia reflects on its origin and purpose.6

The field of global surgery is concerned with the provision of surgical, anaesthetic and obstetric (SAO) care worldwide. In 2015, the report from the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery was published,7 and the World Health Assembly adopted Resolution 68.15, ‘Strengthening emergency and essential surgical care and anaesthesia as a component of universal health coverage’.8 The Lancet Commission carved a niche for global surgery academia by identifying a research agenda, including the determinants, burden and impact of SAO disease; the cost, financing, quality and safety of SAO care; and SAO workforce expansion. In addition, the report highlighted the need for the research agenda to ‘fit the local context’. Thus far, only one bibliometric study has investigated authorship demographics in in global surgery9: this analysis of studies published between 1987 and 2017 found that the majority of authors were affiliated with LMICs, and that the majority of global surgery research was conducted solely by LMIC authors.

The research and authorship dynamics in global surgery academia are evolving rapidly. Notably, there is increased participation of students and early-career researchers in global surgery research. This is facilitated by organisations such as InciSioN, a non-profit organisation which connects students and young doctors passionate about global surgery worldwide.10 We, therefore, conducted a systematic analysis of current trends in authorship demographics for global surgery publications, extending the previous analysis9 by considering the intersection of author gender, authorship position, institutional affiliation (HIC or LMIC) and seniority.

Methods

We conducted a systematic bibliometric analysis of global surgery studies published between 2016 and 2020. We aimed to capture authorship dynamics following the two seminal events in 2015, namely the publication of the Lancet Commission report and adoption of resolution WHA68.15.7 8

We followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines by predefining our eligibility criteria, search strategy, article screening process, data collection variables and data management plan (table 1).11 We searched for articles indexed in the PubMed database for three reasons: (1) PubMed has been used in isolation for bibliometric analyses of global health literature previously4 12; (2) The database was freely accessible by all collaborators and (3) Publications in PubMed-indexed journals are often specifically considered when measuring research productivity, which has implications for authors’ career progression.

Table 1.

Search string

| Search string | (((surg* OR operativ* OR ‘surgical procedur*’ OR anesthe* OR anaesthe* OR obstetric* OR gynecolog* OR gynaecolog*) AND (‘low income’ OR ‘middle income’ OR ‘LMIC’ OR ‘developing countr*’)) OR ‘global surg*’) |

| Database | PubMed |

| Search limits |

|

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

| Variables for data collection |

|

We adapted the search string used by Sgrò et al9 to include studies covering Obstetrics and Gynaecology (O&G), two key aspects of global surgery highlighted by the Lancet Commission.7 We included original English-language research articles, systematic reviews and meta-analyses relating to Surgery, Obstetrics, Gynaecology, Anaesthesia or Critical care addressing at least one area of research identified by the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery,7 with data from LMICs as the primary focus. We excluded articles for which a collaboration was listed as the only author, or individual author affiliations were not stated. Two independent authors blindly screened all articles for inclusion or exclusion, and any conflicts were resolved by discussion between the two authors, failing which the final decision was taken by an independent third author.

All author characteristics were obtained from publicly available data sources, including the author affiliations on PubMed, authors’ public profiles on ResearchGate, LinkedIn and websites of professional bodies (eg, General Medical Council in the UK, College of Surgeons of East, Central and Southern Africa in the region of East, Central and Southern Africa). Author seniority was ranked from 1 to 5 from the least to most senior (table 1): we classified undergraduates as grade 1; postgraduates as grade 2; clinicians in a specialty training programme or post-doctoral academics as grade 3; fully qualified generalist or specialist clinicians, or Principal Investigators as grade 4; and those with a senior leadership or management role as grade 5. We determined author seniority at the time the study was published by comparing the dates that data sources were published or updated with the study’s publication year. If we were unable to deduce author seniority, corresponding authors were emailed with an enquiry regarding authors’ positions at the time the study was published. Author genders were derived from authors’ profiles or their pronouns; if an author’s gender was indeterminable through these sources, Namsor Applied Onomastics software (NamSor Gender API. September 2015; http://blognamsorcom/api/.) was used to approximate the gender from the author’s full name. Author institutional affiliations were defined according to World Bank income categories.13 All data were entered in a custom-designed Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and was independently verified by at least one other author. The Google h5 index was used to assess journal impact; the index is calculated for articles published in the last 5 years, and represents largest number h such that at least h articles were cited at least h times each.14

Data analysis

First, we analysed the distribution of author genders, institutional affiliations, and seniorities across studies related to Surgery, O&G, Anaesthesia and Critical care (A&C) and studies related to more than one of these topics (multiple topics). Then, we analysed the distribution of author gender and seniority for first, last and middle authors affiliated with at least one HIC (termed ‘HIC authors’) and authors affiliated only with LMICs (termed ‘LMIC authors’). We then analysed the intersection between these characteristics by categorising authors into different seniorities within each gender. Finally, within the HIC and LMIC author subgroups, we analysed differences in combined author gender and seniority distribution according to the overall authorship characteristics of the study: we compared all studies with studies where all authors were HIC authors, studies where all authors were LMIC authors, studies with HIC first and last authors, and studies with LMIC first and last authors.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were visualised using histograms to ascertain normality, and median values were calculated. Categorical data were analysed to answer specific study questions, and the χ2 test was used to compare the distributions of author characteristics across various groups of authors. Statistical analysis and graphing were conducted using STATA Statistical Software Release V.16 (StataCorp). A p<0.05 was considered significant. R Statistical Software V.4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used to generate choropleth maps with packages tidyverse, sp, geojsonio, ggplot2 and mapproj.

Results

Summary of studies

The PubMed database screening identified 10 051 articles, of which 1240 studies were eligible for inclusion. The characteristics of a total of 9301 authors from these 1240 studies were analysed (online supplemental figure 1).

bmjgh-2021-006672supp001.pdf (268KB, pdf)

Most studies were related to Surgery (49%) and Obstetrics and Gynaecology (42%), with a small proportion (5%) related to Anaesthesia and Critical care. Observational studies with cross-sectional (39%) and cohort (21%) study designs were the most prevalent (table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the 1240 included studies

| Google h5 index: median | 48 | ||

| Authors per study: median | 6 | ||

| Topic: no of studies (% of total) | Surgery | 611 (49) | |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology (O&G) | 522 (42) | ||

| Anaesthesia and Critical care (A&C) | 59 (5) | ||

| Surgery/O&G | 3 (0.2) | ||

| Surgery/A&C | 15 (1) | ||

| O&G/A&C | 9 (0.7) | ||

| Surgery/O&G/A&C | 21 (2) | ||

| Primary study design: no of studies (% of total | Qualitative | 101 (8) | |

| Cross-sectional | 482 (39) | ||

| Cohort | 266 (21) | ||

| Case–control | 19 (2) | ||

| Case series | 24 (2) | ||

| Clinical trial | 58 (5) | ||

| Feasibility study | 31 (3) | ||

| Costing analysis | 45 (4) | ||

| Systematic review and/or meta-analysis | 99 (8) | ||

| Other | 115 (9) | ||

| Author gender: no of authors (% of total) | Male | 5626 (60) | |

| Female | 3638 (39) | ||

| Unknown | 37 (0.4) | ||

| First author gender: no of authors (% of total) | Male | 642 (52) | |

| Female | 596 (48) | ||

| Unknown | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Last author gender: no of authors (% of total) | Male | 815 (66) | |

| Female | 415 (34) | ||

| Unknown | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Middle author gender: no of authors (% of total) | Male | 4169 (61) | |

| Female | 2627 (38) | ||

| Unknown | 33 (0.5) | ||

| Author seniority: no of authors (% of total) | 1: Undergraduate | 89 (1) | |

| 2: Postgraduate | 806 (9) | ||

| 3: Specialty trainee, postdoctoral academic | 1701 (18) | ||

| 4: Consultant/attending clinician fully qualified as a generalist or specialist, principal investigator | 3862 (42) | ||

| 5: Senior leadership or management | 2258 (24) | ||

| Unknown | 585 (6) | ||

| First author seniority: no of authors (% of total) | 1 | 20 (2) | |

| 2 | 139 (11) | ||

| 3 | 313 (25) | ||

| 4 | 519 (42) | ||

| 5 | 201 (16) | ||

| Unknown | 48 (4) | ||

| Last author seniority: no of authors (% of total) | 1 | 1 (0.08) | |

| 2 | 35 (3) | ||

| 3 | 135 (11) | ||

| 4 | 536 (44) | ||

| 5 | 496 (40) | ||

| Unknown | 29 (2) | ||

| Middle author seniority: no of authors (% of total) | 1 | 68 (1) | |

| 2 | 632 (9) | ||

| 3 | 1253 (18) | ||

| 4 | 2807 (41) | ||

| 5 | 1561 (23) | ||

| Unknown | 508 (7) | ||

| Author institutional affiliation: no of authors (% of total) | High income country (HIC) | 4744 (51) | |

| All low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC) | 4192 (45) | ||

| Upper-middle-income country (MIC) | 1180 (13) | ||

| Lower MIC | 1908 (21) | ||

| Low income country (LIC) | 1089 (12) | ||

| MIC and LIC (MIC and LIC) | 15 (0.2) | ||

| HIC and L/MIC | 365 (4) | ||

| First author institutional affiliation: no of authors (% of total) | HIC | 706 (57) | |

| LMIC | 417 (34) | ||

| HIC and L/MIC | 117 (9) | ||

| Last author institutional affiliation: no of authors (% of total) | HIC | 792 (64) | |

| LMIC | 356 (29) | ||

| HIC and L/MIC | 84 (7) | ||

| Middle author institutional affiliation: no of authors (% of total) | HIC | 3246 (48) | |

| LMIC | 3419 (50) | ||

| HIC and L/MIC | 164 (2) | ||

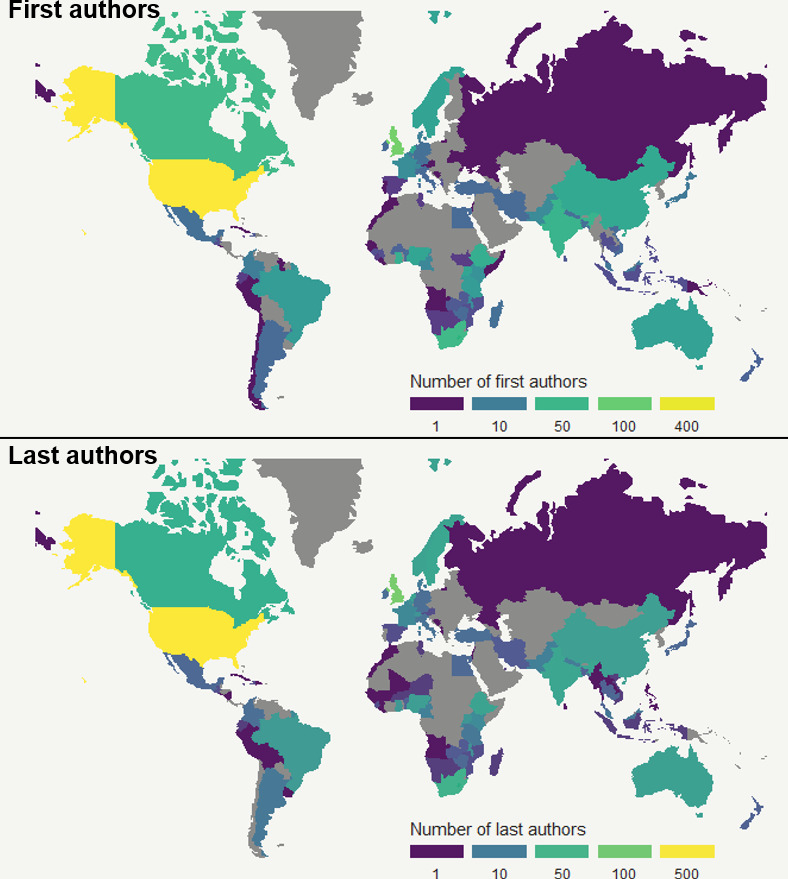

The majority of authors were male (60%), and of high seniority (seniority 4: 42%, seniority 5: 24%). 51% of authors were affiliated with HICs alone, and a further 4% were affiliated with both HICs and LMICs. 45% of authors were only affiliated with LMICs—of these LMIC authors, 46% were affiliated with lower middle-income countries, and similar proportions were affiliated with upper middle-income (28%) and low-income countries (26%). Male authors and authors of seniority 4 remained the majority across first, last and middle authors, although 40% of last authors were of seniority 5. Over two-thirds of first and last authors and half of middle authors were affiliated with at least 1 HIC institution. 39% of first authors and 43% of last authors were affiliated with institutions in the USA (table 2 and figure 1).

Figure 1.

Country affiliations of first and last authors. World maps depicting the number of first authors and last authors affiliated with a country.

Missing data

Information regarding author seniority was missing for 10.7% of authors affiliated with LMICs, but for less than 3% of authors affiliated with HICs alone or both HICs and LMICs. Author gender data were missing for less than 1% of authors across all author affiliation categories (online supplemental figure 1).

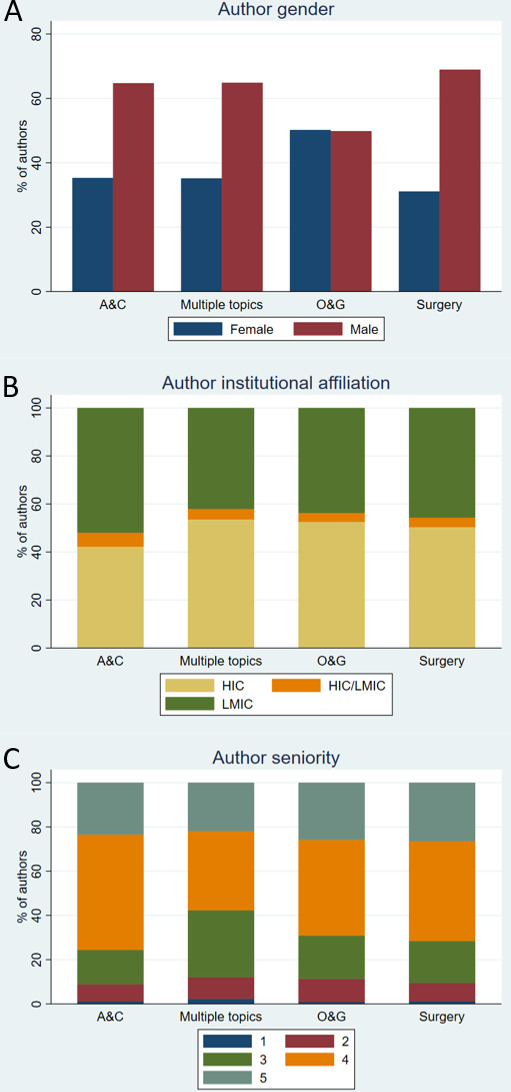

Authorship demographics by study topic

65% of authors in studies related to A&C and multiple topics, and 69% of authors in studies related to Surgery were male; whereas, the proportions of male and female authors were equal in O&G studies (figure 2). The majority of authors across all topics except A&C were only affiliated with HIC institutions (O&G: 53%, Surgery: 50%, Multiple topics: 54%), while 52% of authors in A&C studies were affiliated only with LMIC institutions (figure 2B). Most authors were of seniority grades 4 and 5 regardless of study topic (figure 2C). The differences in distribution of author gender, institutional affiliation and seniority shown in figure 2 were statistically significant (online supplemental table S2).

Figure 2.

Author demographics for studies related to Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynaecology (O&G), Anaesthesia and Critical care (A&C) and Multiple topics. Percentages of: (A) male and female authors; (B) authors affiliated with only HICs, with only LMICs and with both HICs and LMICs; (C) authors of seniorities 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest). (HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low-income and middle-income country.)

bmjgh-2021-006672supp002.pdf (359.7KB, pdf)

Authorship demographics by institutional affiliation

LMIC authors had a significantly higher proportion of male authors overall: 67% of first and middle authors and 73% of last authors were male (online supplemental table S3). LMIC authors also had more first and middle authors of seniorities 4 and 5 (online supplemental table S3).

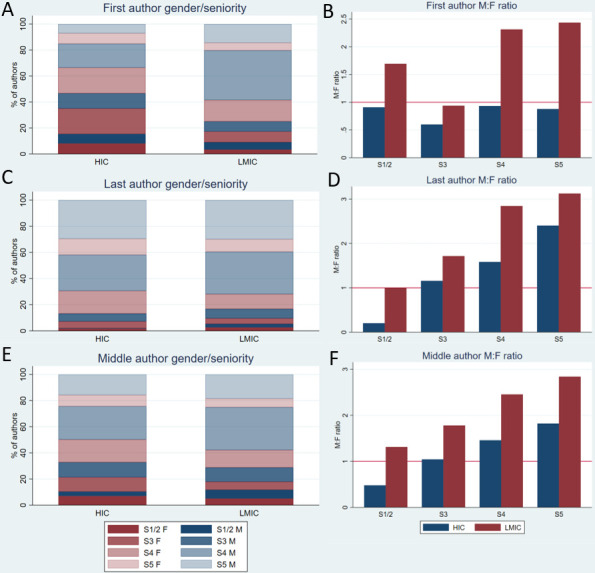

The proportion of male authors increased with increasing seniority for last authors and middle authors regardless of institutional affiliation (figure 3D, F). There were more female than male authors among HIC first authors of all seniorities, and HIC middle and last authors of seniorities 1 and 2; conversely, there were more male than female LMIC authors at nearly all seniority grades (figure 3). The differences in the distribution of combined gender and seniority between HIC and LMIC authors shown in figure 3 were statistically significant for first, last and middle authors (online supplemental table S4).

Figure 3.

Gender and seniority of authors affiliated with at least 1 HIC (HIC authors) and authors affiliated only with LMICs (LMIC authors). (A, C, E) Percentages of male and female authors at each seniority grade for first (A), last (C) and middle (E) authors. (B, D, F) Male:Female ratio (M:F) (number of male authors/number of female authors) at each seniority grade for first (B), last (D) and middle (F) authors. Seniority 5 represents the highest seniority. (HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low-income and middle-income country.)

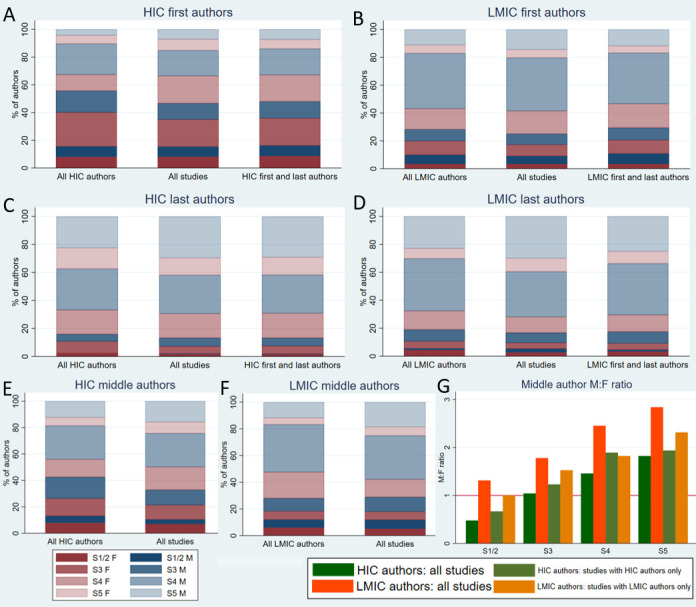

Authorship demographics by overall authorship network

Finally, we compared four study types with different authorship networks: studies with only HIC authors, only LMIC authors, HIC first and last authors, and LMIC first and last authors. 21% of studies had LMIC first and last authors, whereas 59% had HIC first and last authors (online supplemental table S5). The median h5 index was comparable across study types (online supplemental table S5).

There were more junior HIC middle authors (of seniorities 1 to 3) in studies with only HIC authors (43%) compared with all studies (33%) (figure 4E). The proportion of female LMIC middle authors increased in studies with only LMIC authors (37% female vs 31% in all studies), whereas the proportion of female HIC middle authors decreased in studies with only HIC authors (40% female vs 44% in all studies) (figure 4F, G). The differences in the distribution of combined author gender and seniority across different study types were statistically significant for middle authors from both HICs and LMICs (online supplemental table S6: subgroup analyses for HIC middle authors and LMIC middle authors). The number of middle authors for whom gender and seniority was known was low in studies with HIC first and last authors, and studies with LMIC first and last authors. Therefore, the analysis was repeated after excluding these study types, but the statistical significance remained unaltered (online supplemental table S6).

Figure 4.

Gender and seniority of HIC authors and LMIC authors, separated by overall authorship network. Author demographics are shown for all studies, studies where all authors are affiliated only with HICs (all HIC authors), studies with HIC first and last authors, studies where all authors are affiliated only with LMICs (all LMIC authors) and studies with LMIC first and last authors. Seniority 5 represents the highest seniority. (A, C, E) Percentages of male and female authors at each seniority grade for HIC first (A), last (C) and middle (E) authors. (B, D, F) Percentages of male and female authors at each seniority grade for LMIC first (B), last (D) and middle (F) authors. (G) Male:female ratio (M:F) (number of male authors/number of female authors) at each seniority grade for HIC and LMIC middle authors. (HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low-income and middle-income country.)

Discussion

Bibliometric studies of global health publications not only identify authorship representation and subject trends but also indirectly assess data ownership and development of research capacity in LMICs. Many of these studies have reported inequalities in global health research overall, with marginalisation and disempowerment of LMIC authors, especially women.3–5 12 15–20 Global surgery research has gained momentum since the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery highlighted the need for evidence to expand access to surgical care worldwide in 2015.7 This study is the first bibliometric analysis of global surgery publications to describe the intersection between author gender, seniority and institutional affiliation.

Our study found a preponderance of male authors and authors affiliated with HICs within recently published global surgery literature (table 2). Moreover, a greater proportion of LMIC-affiliated authors were found to be male and of higher seniority (figure 2 and online supplemental table S3). A consistent gender gap was found among LMIC authors, with a lower proportion of female compared with male authors at nearly every seniority grade across first, last and middle authors (figure 3 and online supplemental table S4). There was a paucity of LMIC authors in prominent first and last author positions (table 2 and online supplemental table S5).

Our findings contrast with those of Sgrò et al, whose bibliometric analysis of global surgery publications from 1987 to 2017 found that the proportion of LMIC-affiliated authors was twice as high as HIC authors, and that the majority of studies were conducted entirely by LMIC authors.9 The definition of global surgery research differed between the two studies. We included terms for O&G within our search string to ensure identification of studies related to all aspects of SAO care. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were included in our study to capture research synthesis efforts in global surgery literature. We included research primarily focusing on data related to LMICs to capture multicentre global surgery studies, whereas Sgrò et al excluded research conducted outside LMICs unless HIC data was only used for comparison. We defined the scope of global surgery research more specifically based on research recommendations from the Lancet Commission.7 However, the difference in definitions does not explain the discrepancy in findings. We found that studies related to O&G and those related to Surgery had similar representation of LMIC authors, and that systematic reviews were a minority of the studies included. Our search strategy was also designed to exclude studies mainly discussing data from HICs. Furthermore, although the Scopus database used by Sgrò et al indexes more journals, it is not known to index more local or regional journals from LMICs.19 Our study identified 1240 publications in 5 years (2016–2020) compared with Sgrò et al, who found 1623 articles published over 30 years (1987–2017). This implies that there may be disenfranchisement of LMIC authors despite an increasing number of publications. The academic resources in HIC institutions—including technology, institutional access to journals and the ability to collaborate with statisticians—may have allowed HIC academics to rapidly shift their focus to global surgery following the increased prominence of the field in 2015. Funding bodies may therefore be disproportionately funding academic global surgery centres based in HIC institutions in this post-2015 golden age of global surgery.

Our findings echo those of Morgan et al, who found that the greatest gender gap in global health academic authorship existed among LMIC authors.5 We noted that the gender gap increased with increasing seniority for last authors and middle authors regardless of institutional affiliation. Importantly, our results indicate that this gender disparity among LMIC middle authors is mitigated at every seniority grade when all authors in the study are affiliated solely with LMIC institutions (figure 4 and online supplemental table S6). This implies that gender disparities in LMIC authorship may also be a feature of collaborative global surgery research between HICs and LMICs.

Authorship dynamics may be considered a proxy for the power dynamics between HIC-affiliated and LMIC-affiliated researchers in global surgery research. This is noteworthy as the Lancet Commission recommends the development and implementation of national surgical plans, designed to strengthen surgical systems within health systems, based on country-specific needs assessments.7 As countries around the world use data from global surgery research studies to design their national surgical plans,21 the power imbalances within global surgery academia are at risk of being transferred to national policy and adversely affecting resource allocation.

There are several possible reasons for the over-representation of HIC-affiliated authors in global surgery, particularly in prominent first and last author positions. These include the availability of research infrastructure, access to academic resources, familiarity with the English language, availability of protected research time and the ability to afford article processing fees for open access journals.4 22 Token authorship with middle author positions is frequently seen as appeasement for the LMIC authors.15 The gender disparity observed among all authors, but particularly among LMIC authors and authors of higher seniority, reflects entrenched biases against female academics in research grant allocation and career progression, as well as collaborator selection within HIC-LMIC research partnerships.5 23 24 Other potential contributing factors could be the adverse effect of childcare leave and the gender gap in self-promotion.25 26 Such gender inequity may discourage student and early-career researchers who have contributed significantly to global surgery research and advocacy.10

We found that the proportion of authors of seniorities 1–3 was lower for LMIC first and middle authors compared with HIC authors (online supplemental table S3). Better academic infrastructure may have created more conducive research environments for junior researchers in HICs. We also noted that HIC middle authors in studies with only HIC authors were more likely to be junior compared with those in all studies (online supplemental table S6), suggesting that HIC-only global surgery research networks offered more opportunities for junior HIC researchers. No such trend was seen with LMIC middle authors. Enthusiasm for global surgery research exists among junior researchers in both HICs and LMICs10 and so, junior researchers from LMICs need to be offered sympathetic mentorship and authorship opportunities on par with their HIC peers.

Fundamentally, any collaboration between HICs and LMICs is burdened with financial inequalities as many studies conducted in LMICs are funded and led by HIC institutions.27 28 In our study, 34% of first authors and 29% of last authors were affiliated solely with LMIC institutions (table 2), whereas 39% of first authors and 43% of last authors were affiliated with institutions in the USA (figure 1). Moreover, 50% of studies with LMIC first and last authors had only LMIC-affiliated authors, whereas the median percentage of LMIC-affiliated authors in studies with HIC first and last authors was much lower at 22.6%. A recent systematic review of collaborative global health research in sub-Saharan Africa revealed that representation of authors from the country of the paper’s focus was lowest if collaboration was with researchers from USA, Canada or Europe.4 A ‘silo’ effect has been found, with the existence of insular research clusters of connected HIC authors, particularly from the UK and the USA, dominating many HIC-LMIC global health collaborations29 30—this may be contributing to the increased gender gap in LMIC middle authors seen in publications coauthored by HIC and LMIC authors. Thus, there is an urgent need for equitable research collaborations which are designed to meet the local research need and give due credit to local stakeholders, as opposed to rigid partnerships which unilaterally shape research agendas and authorship dynamics.

Confirming the existence of these inequities is just the beginning. Actions are needed across many fronts, including the development of more inclusive policies by international funders to shift research control to LMICs, a change in standard authorship guidelines for collaborative global surgery research designed to empower LMIC authors, adherence to good collaboration practices to promote equity, and greater investment in meaningful research capacity building.12 15 17 18 31–33 The gender disparity within global surgery academia deserves specific attention but is unfortunately not an exceptional phenomenon; structural misogyny has been found across a range of fields where such inequities have been studied.34 35 Funding application processes, peer-review processes, the availability of research and leadership opportunities and academic career progression pathways need to be critically assessed and corrected for gender bias within HIC and LMIC institutions but also within HIC-LMIC research partnerships.35

The prevalence of virtual meetings and collaborations in the COVID-19 era brings opportunities for research capacity building36 and facilitates participation of LMIC stakeholders in global surgery events,37 but cannot be considered a panacea. Access to a secure high-speed Internet connection remains problematic across many LMICs, thereby hindering meaningful participation of LMIC attendees at virtual events. Links to virtual events are often distributed via mailing lists or social media announcements by HIC organisations, limiting the involvement of patients, carers, policy-makers and other LMIC stakeholders in priority setting. Intentional efforts must be taken to widen meaningful participation of LMIC stakeholders at virtual meetings, probably best achieved when led by LMIC organisations. This is crucial considering the inequitable access to COVID-19 vaccines worldwide and discussions regarding ‘vaccine passports’.38 Furthermore, virtual collaborations may allow HIC researchers without real-world understanding of SAO care in the study country(ies) to occupy prominent roles in global surgery research due to the availability of academic resources, contributing to authorship parasitism18; equitable opportunities must be made available to LMIC researchers in virtual research collaborations.

If effective decolonisation of global surgery is to be achieved, ‘research on research’ through bibliometric studies like ours is needed for accountability, to pinpoint gaps in equity, diversity and inclusion, and to highlight where action is necessary.23 39 40 Nevertheless, our study has limitations. The use of PubMed as our sole database is likely to have excluded studies from local and regional journals, particularly those from LMICs,4 potentially excluding articles with greater representation of LMIC authors. However, the under-representation of LMIC authors—the major stakeholders of global surgery—in PubMed-indexed international journals remains unjust. Restricting the search to English-language articles excluded global surgery literature in Spanish and Portuguese from South and Central America, French from the Francophone African nations and Arabic from the Middle East and North Africa, which is likely to have excluded more studies from LMIC journals.41 However, publishing in English is widely recognised to increase the visibility of research,41 thereby increasing the likelihood of future funding and impacting advocacy efforts—thus, the dominance of HIC authors within English-language global surgery literature is likely to exacerbate inequities. Another limitation is that author seniority data are missing disproportionately for LMIC-affiliated authors. We attempted to mitigate this by contacting corresponding authors for information regarding author seniority, but the response rate was low. It is also possible that female LMIC authors are less likely to have academic profiles online than male LMIC authors, which could have contributed to the gender gaps found among LMIC authors. Finally, although NamSor reportedly covers all languages and countries, it performs poorly when inferring genders of Asian names—one study found that 35% of Asian names were classified inaccurately by Namsor compared with 3% of European and 7% of African names.42

Conclusion

Despite increasing awareness of their existence in global health research, authorship inequities related to gender and institutional affiliation are still prevalent within global surgery publications published within the last 5 years. Such inequities result in the systematic under-valuation of the work of researchers, especially women, from LMICs, thereby affecting career progression and access to research funding. They may also contribute to the neglect of local context and perspectives. It is ironic that these LMIC researchers, who are the major stakeholders in global surgery, face such inequities in academia, as the raison d'être of global surgery is to provide equitable surgical care all over the world. Bibliometric studies such as ours can pinpoint gaps in authorship equity so that necessary remedial actions can be taken.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Sarah Davidson for her support and wisdom during the process of conducting this study. We thank Mr David Layfield for his timely input regarding the design of the data collection spreadsheet. We thank Dr Niveshni Maistry for her generous assistance with collaborator recruitment.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @krithi95, @danielsafari12, @KyrillosWassim, @Nina MBF

AT, AB, DD, FB, ME, NB, SSNHS and SB contributed equally.

HK, HK and MNS-D contributed equally.

AA, AS, AGMN, A-TW, AN, AS, ANM, ADN, AS, BH, DSN, DWN, EdW, EAT, FZW, HE, HM, HM, KN, KR, KW, LAO, LSN, MM, MN, MGP, NT, NEA, OMM, OAS, OO, PC, PP, RPH-S, SK, SM, SM, SEH, TA, VAK, VA, WS, WM, YAF, ZO and ZA contributed equally.

ME and NAH contributed equally.

Contributors: KriR conceived the idea for the study, designed the protocol and data collection tool, recruited and supervised collaborators, screened articles, collected data from included articles, cleaned and analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. DS performed the background literature review, provided guidance regarding the study idea, protocol design and data analysis, contributed to collaborator recruitment, and wrote the manuscript. ZB provided feedback regarding the study protocol and data collection tool, contributed to collaborator recruitment, screened articles and collected data from included articles. AT, AB, DD, FB, ME, NB, SSNHS and SB completed their share of the article screening and data collection from included studies. HKh, HKi and MNS-D completed their share of the article screening and partially completed their share of the data collection. AN, ASo, ANM, ADN, ASa, BH, DSN, DWN, EdW, EAT, FZW. HE, HMou, HMoo, KN, KruR, KWN, LAO, LSN, MM, MN, MGP, NT, NEA, OAS, OMM, OO, PC, PP, RPH-S, SK, SMa, SMo, SEH, TA, VAK, VA, WS, WM, YAF, ZO and ZA completed their share of the article screening or data collection. ME and NAH partially completed their share of the data collection. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Raw data used for analysis are supplied in Tables included in either the main manuscript or in Supplementary Information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

As the study did not involve any patients or staff, it was deemed exempt from ethical approval by the Research and Development Department at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

References

- 1.Sharma D, Agrawal V, Agarwal P. Roadmap for clinical research in resource-constrained settings. Tropical Doctor 2020;51:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Lancet global H (2021) global health 2021: who tells the story? Lancet Glob Health;9:e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cash-Gibson L, Rojas-Gualdrón DF, Pericàs JM, et al. Inequalities in global health inequalities research: a 50-year bibliometric analysis (1966-2015). PLoS One 2018;13:e0191901. 10.1371/journal.pone.0191901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedt-Gauthier BL, Jeufack HM, Neufeld NH, et al. Stuck in the middle: a systematic review of authorship in collaborative health research in Africa, 2014-2016. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001853. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan R, Lundine J, Irwin B, et al. Gendered geography: an analysis of authors in the Lancet global health. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e1619–20. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30342-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abimbola S. On the meaning of global health and the role of global health journals. Int Health 2018;10:63–5. 10.1093/inthealth/ihy010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, et al. Global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015;386:569–624. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.. WHA68.15: strengthening emergency and essential surgical care and anaesthesia as a component of universal health coverage World Health Organization; 2015. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA68/A68_R15-en.pdf [Accessed 14 Aug 2021.]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sgrò A, Al-Busaidi IS, Wells CI, et al. Global surgery: a 30-year bibliometric analysis (1987-2017). World J Surg 2019;43:2689–98. 10.1007/s00268-019-05112-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vervoort D, Bentounsi Z. Incision: developing the future generation of global surgeons. J Surg Educ 2019;76:1030–3. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2016;354:i4086. 10.1136/bmj.i4086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mbaye R, Gebeyehu R, Hossmann S, et al. Who is telling the story? A systematic review of authorship for infectious disease research conducted in Africa, 1980-2016. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001855. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Bank. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/ [Accessed 14 Aug 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Google. Available: https://scholar.google.com/intl/en/scholar/metrics.html#metrics [Accessed 14 Aug 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelaher M, Ng L, Knight K, et al. Equity in global health research in the new millennium: trends in first-authorship for randomized controlled trials among low- and middle-income country researchers 1990-2013. Int J Epidemiol 2016;45:2174–83. 10.1093/ije/dyw313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghani M, Hurrell R, Verceles AC, et al. Geographic, subject, and authorship trends among LMIC-based scientific publications in high-impact global health and general medicine journals: a 30-month bibliometric analysis. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2021;11:92–7. 10.2991/jegh.k.200325.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chersich MF, Blaauw D, Dumbaugh M, et al. Local and foreign authorship of maternal health interventional research in low- and middle-income countries: systematic mapping of publications 2000-2012. Global Health 2016;12:35. 10.1186/s12992-016-0172-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rees CA, Lukolyo H, Keating EM, et al. Authorship in paediatric research conducted in low- and middle-income countries: parity or parasitism? Trop Med Int Health 2017;22:1362–70. 10.1111/tmi.12966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimitris MC, Gittings M, King NB. How global is global health research? A large-scale analysis of trends in authorship. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e003758. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iyer AR. Authorship trends in the Lancet global health. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e142. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30497-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gajewski J, Bijlmakers L, Brugha R. Global Surgery - Informing National Strategies for Scaling Up Surgery in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Health Policy Manag 2018;7:481–4. 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma D. A call for reforms in global health publications. Lancet Glob Health 2021;9:e901–2. 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00145-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacLean E, Bigio J, Singh U, et al. Global tuberculosis awards must do better with equity, diversity, and inclusion. Lancet 2021;397:192–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32627-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jumbam DT. How (not) to write about global health. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e003164. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riner AN. Herremans Km, Neal DW, et al (2021) diversification of academic surgery, its leadership, and the importance of intersectionality. JAMA Surg 156:748-756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Arora TK, Greenberg CC. Time for deliberate organizational and departmental Action-Seize the awakening. JAMA Surg 2021;156:756–7. 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ndounga Diakou LA, Ntoumi F, Ravaud P, et al. Published randomized trials performed in sub-Saharan Africa focus on high-burden diseases but are frequently funded and led by high-income countries. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;82:29–36. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fourie C. The trouble with inequalities in global health partnerships. MAT 2018;5:142–55. 10.17157/mat.5.2.525 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maleka EN, Currie P, Schneider H. Research collaboration on community health worker programmes in low-income countries: an analysis of authorship teams and networks. Glob Health Action 2019;12:1606570. 10.1080/16549716.2019.1606570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collyer TA, Smith KE. An atlas of health inequalities and health disparities research: "How is this all getting done in silos, and why?". Soc Sci Med 2020;264:113330. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaccour J. Authorship trends in the Lancet global health: only the tip of the iceberg? Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e497. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30110-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faure MC, Munung NS, Ntusi NAB, et al. Mapping experiences and perspectives of equity in international health collaborations: a scoping review. Int J Equity Health 2021;20:28. 10.1186/s12939-020-01350-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker M, Kingori P. Good and bad research collaborations: researchers' views on science and ethics in global health research. PLoS One 2016;11:e0163579. 10.1371/journal.pone.0163579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruzycki SM, Franceschet S, Brown A. Making medical leadership more diverse. BMJ 2021;373:n945. 10.1136/bmj.n945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Filardo G, da Graca B, Sass DM, et al. Trends and comparison of female first authorship in high impact medical journals: observational study (1994-2014). BMJ 2016;352:i847. 10.1136/bmj.i847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gandhi SM, Ravi K, Jalloh-Pa-R F, et al. Building sustainable and consequential research capacity within a global alliance of paediatric surgical centres. Pediatr Surg Int 2021;37:677–8. 10.1007/s00383-021-04858-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Velin L, Lartigue J-W, Johnson SA, et al. Conference equity in global health: a systematic review of factors impacting LMIC representation at global health conferences. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e003455. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voigt K, Nahimana E, Rosenthal A. Flashing red lights: the global implications of COVID-19 vaccination passports. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e006209. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Büyüm AM, Kenney C, Koris A, et al. Decolonising global health: if not now, when? BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e003394. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abimbola S, Pai M. Will global health survive its decolonisation? Lancet 2020;396:1627–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32417-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bentounsi Z, Vervoort D, Drevin G. Global surgery doesn't belong to the English language. BMJ Global Health Blogs 2019;18. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santamaría L, Mihaljević H. Comparison and benchmark of name-to-gender inference services. PeerJ Comput Sci 2018;4:e156. 10.7717/peerj-cs.156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2021-006672supp001.pdf (268KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-006672supp002.pdf (359.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Raw data used for analysis are supplied in Tables included in either the main manuscript or in Supplementary Information.