Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the relationship between markers of staff employment stability and use of short-term healthcare workers with markers of quality of care. A secondary objective was to identify clinic-specific factors which may counter hypothesised reduced quality of care associated with lower stability, higher turnover or higher use of short-term staff.

Design

Retrospective cohort study (Northern Territory (NT) Department of Health Primary Care Information Systems).

Setting

All 48 government primary healthcare clinics in remote communities in NT, Australia (2011–2015).

Participants

25 413 patients drawn from participating clinics during the study period.

Outcome measures

Associations between independent variables (resident remote area nurse and Aboriginal Health Practitioner turnover rates, stability rates and the proportional use of agency nurses) and indicators of health service quality in child and maternal health, chronic disease management and preventive health activity were tested using linear regression, adjusting for community and clinic size. Latent class modelling was used to investigate between-clinic heterogeneity.

Results

The proportion of resident Aboriginal clients receiving high-quality care as measured by various quality indicators varied considerably across indicators and clinics. Higher quality care was more likely to be received for management of chronic diseases such as diabetes and least likely to be received for general/preventive adult health checks. Many indicators had target goals of 0.80 which were mostly not achieved. The evidence for associations between decreased stability measures or increased use of agency nurses and reduced achievement of quality indicators was not supported as hypothesised. For the majority of associations, the overall effect sizes were small (close to zero) and failed to reach statistical significance. Where statistically significant associations were found, they were generally in the hypothesised direction.

Conclusions

Overall, minimal evidence of the hypothesised negative effects of increased turnover, decreased stability and increased reliance on temporary staff on quality of care was found. Substantial variations in clinic-specific estimates of association were evident, suggesting that clinic-specific factors may counter any potential negative effects of decreased staff employment stability. Investigation of clinic-specific factors using latent class analysis failed to yield clinic characteristics that adequately explain between-clinic variation in associations. Understanding the reasons for this variation would significantly aid the provision of clinical care in remote Australia.

Keywords: human resource management, quality in healthcare, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Data are for an entire population—remote living residents in communities serviced by Northern Territory (NT) Department of Health.

Analyses adjusted for key potential confounders, including remote community population size, average number of employees, Euclidean distance in kilometres to the major centres of Darwin or Alice Springs (whichever was closest) and Euclidean distance in kilometres to the nearest of the five NT hospitals.

The major limitation was the retrospective design, relying on routinely collected and administrative data.

Introduction

Australia is a geographically large country (7.7 million km2) with a concentration of both population and healthcare resources along its eastern and southern seaboard.1 In 2019, 69% of the Australian estimated resident population lived in the eastern and southern seaboard state capital cities and three large regional towns (Newcastle, Wollongong and Geelong).2 A relatively small fraction of the Australia’s healthcare resources are used to service the primary healthcare (PHC) needs of its extensive rural and remote populations, with the National Rural Health Alliance estimating a large rural health expenditure deficit of approximately US$2bn per annum.3

In non-metropolitan Australia, access to PHC is further limited by the combination of high health need and the need for cultural competency when providing health services for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations who have much greater health needs across both acute and chronic conditions relative to all Australians.4 This is particularly apparent in the Aboriginal population of the Northern Territory (NT) where chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes are up to four times more prevalent and life expectancy at birth is approximately 16 years less than the corresponding measure for Australia as a whole.5 While continuity of care is important for all patients, it is especially important for vulnerable populations, such Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations living in small, isolated communities.6 7 Continuity of high-quality PHC can help ensure chronic health conditions are prevented where possible, and diagnosed early and managed optimally where not, ensuring that patients avoid potentially preventable hospitalisations.8 9

The long-standing geographical maldistribution of general practitioners has been the target of numerous programmes by government and health professional bodies over a long period, with only mixed success.10–12 In geographically remote areas, PHC services are more commonly provided by resident remote area nurses (RANs) and aboriginal health practitioners (AHPs), supported by visiting medical, nursing and allied health professionals, and other short-term health workers engaged on a fly-in fly-out or drive-in-drive-out basis and often engaged through employment agencies.13 While resident staff remain in a community from months to several years and therefore get to know and be known by community members, short-term employment agency staff may only be in a community for a period of weeks. Such short tenure makes continuity of care less attainable and staff less able to develop appropriate levels of cultural and social awareness to engage effectively with local residents, leading to lower utilisation of PHC services.14 15 Lower PHC utilisation may contribute to poorer health outcomes: better access and utilisation of PHC by aboriginal people living in remote NT communities and remote outstations is associated with lower mortality, lower morbidity and more cost-effective healthcare, though the association between PHC utilisation and hospitalisations is more complex.16–18

A further potential consequence of poor continuity of care and cultural attunement of healthcare staff is reduced quality of care. Short-term staff may focus on acute care needs and neglect or have insufficient awareness of preventive and chronic care needs, such as health promotion, health screening, monitoring chronic health conditions, encouraging smoking cessation or checking the immunisation status of infants and adults. Most, though not all, research shows that continuity of PHC provider is associated with better control of type 2 diabetes19–22 as well as increased provision of preventive care services including immunisations and screening for hypertension, alcohol abuse and high cholesterol levels.23 However, the extent to which continuity of care and measures of staff turnover and stability are associated with quality of care in complex cross-cultural contexts characterised by reliance on short-term PHC providers is not well understood. While research using a case study design suggests that in remote NT, PHC workforce turnover is the most significant barrier to successful quality improvement, the association between workforce turnover or stability and quality of PHC in remote NT is yet to be verified using stronger study designs.24

This article, therefore, seeks to evaluate the relationship between markers of staff employment stability and turnover and use of short-term PHC staff with markers of quality of care, in order to determine whether these are detrimental to the care received by residents of remote locations. We hypothesised that stability would be positively associated with quality measures and that turnover and the use of short-term PHC staff would be negatively associated with quality measures. We also sought to identify factors which may counter hypothesised reduced quality of care associated with lower stability, higher turnover or higher use of short-term staff.

Methods

Study design and setting

This observational study has a retrospective cohort design: the cohort consists of patients, RANs, AHPs and short-term staff of 48 NT Department of Health (DoH) remote clinics during the period 2011–2015, inclusive.

Data

Data were provided by the NT DoH. Workforce data were obtained from the Personnel Information and Payroll Systems (PIPS) dataset. PIPS data provided comprehensive, individual-level, deidentified information on all RANs and AHPs paid directly through the NT DoH payroll. These data were used to ascertain the number of RAN and AHP exits from remote health services and to calculate annual turnover and 12-month stability rates. The government accounting system was used to identify labour hire costs for agency nurses paid directly by employment agencies (hereafter termed agency nurses). The aggregated full-time equivalent (FTE) for agency-employed nurses working in remote health services was derived using the standard NT DoH formula of agency labour expenses divided by twice the departmental annual average nurse personnel cost.25

Quarterly Traffic Light Reports were produced by NT DoH staff for each remote community as part of the Chronic Conditions Management Model.26 The combined Traffic Light Report, which has retrospective data for all NT DoH remote health clinics, was the source of data for twelve quality indicators. Data for some indicators were available every 3 months from March 2012 to November 2015, though reporting on other indicators commenced at a later date (the latest being August 2013). Additionally, routine health services reports of NT Aboriginal Health Key Performance Indicators (AHKPIs), extracted from the NT DoH Primary Care Information Systems, were the source of data for a further twelve quality indicators. The NT AHKPI data related to outcomes for 25 413 patients. NT AHKPI data were available for 48 of 53 NT DoH clinics in the larger study. NT AHKPI data were not available for five clinics that used a different PHC electronic clinical records management system.

Measures

In this study, the main independent variables were clinic-level measures of RAN and AHP annual turnover and 12-month stability and the proportional use of agency nurses. Hereafter, these three measures will be collectively referred to as markers of staff employment stability. We used three different measures of staff employment stability because of the complexities involved in staffing remote health services, the known heavy reliance on agency nurses in remote NT and because none of these workforce metrics on their own provide a sufficiently comprehensive picture of workforce mobility patterns.27 28 The three main workforce metrics are defined in table 1. An additional metric, the number of exits from a health service (which is the numerator of the turnover metric), was used in the latent class analysis.

Table 1.

Definitions of indicators measuring employment stability (main independent variables)

| Measure | Definition |

| Turnover rate | |

| Stability rate | |

| Agency nurse proportion |

FTE, full-time equivalent.

Additional independent variables (potential confounders) included remote community population size, average number of employees, Euclidean distance in kilometres to the major centres of Darwin or Alice Springs (whichever was closest) and Euclidean distance in kilometres to the nearest of the five NT hospitals (distances calculated using google maps). The socioeconomic status of the community in which each clinic was located was measured using the Index of Relative Socioeconomic Advantage and Disadvantage for clinic catchment areas’ average scores for Indigenous localities29 as measured in the 2011 national census conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The Aboriginal composition of each community was measured as the proportion of the resident population identifying as an aboriginal person in the 2016 census.30 The latter was dichotomised into whether or not aboriginal people comprised a majority of the population (>50%) in the community.

We were initially provided with data for 24 quality indicators (several of which were the same indicator but measured using different data sources at slightly different time points). Some indicators also had more than one component. For example, child immunisation was categorised into different age groups and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) results were categorised into different levels of glycaemic control. Our aim was to examine a sufficient range of indicators of quality of care to ensure that a reasonable spectrum of PHC activities was covered by the indicators, rather than to be exhaustive. We, therefore, grouped quality indicators into three categories: child and maternal health; chronic disease management and preventive health activity, and reduced the number of indicators, ensuring there were at least three indicators within each category (table 2). The reporting period for the indicators ranged from 6 months for the HbA1c test reported in the NT AHKPIs, up to 2 years.

Table 2.

Definitions of quality indicators (dependent variables)

| Indicator name | Definition | Denominator population | Source of data |

| Child and maternal health | |||

| First antenatal visit | Number and proportion of regular clients who attended a first antenatal visit (at any health service locality)

|

Resident women who gave birth to an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander baby | NT AHKPI |

| Fully immunised children | Number and proportion of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander children fully immunised at

|

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander resident children aged 6 months to <6 years | NT AHKPI |

| Anaemia test | Number and proportion of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander children who, in the past year have been tested for anaemia | Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander resident children who are ≥6 months old and <5 years | NT AHKPI |

| Anaemia result | Number and proportion of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander children who, in the past year have been found to be anaemic | Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander resident children who are ≥6 months old and <5 years | NT AHKPI |

| Chronic disease management | |||

| Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) test | Number and proportion of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander resident clients aged 15 years and over with type 2 diabetes mellitus who have had a HbA1c test in the past 12 months. | Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander resident clients aged ≥15 years diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus | TLR |

| HbA1c result | Number and proportion of Aboriginal or Torres Strait islander clients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and whose most recent HbA1c measurement within the past 12 months is ≤8% (≤86 mmol/mol) | Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander resident clients aged ≥15 years diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus and had HbA1c tested | TLR |

| ACE inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker | Number and proportion of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander clients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with albuminuria who are on ACE Inhibitor and/or an angiotensin receptor blocker. | Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander resident clients aged ≥15 years diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus and albuminuria | TLR |

| Non-smoking | Number and proportion of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander clients who are ex- or never smokers of cigarettes | Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander residents aged ≥15 who have had their smoking status recorded | TLR |

| Preventive health | |||

| Pap smear tests | Number and proportion of eligible Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander women who have had at least one Pap smear test during the last:

|

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander resident women aged 20–69 inclusive | NT AHKPI |

| Adult health check 15–55 | Number and proportion of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander clients who have had a full adult health check. | Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander resident clients aged 15 years to <55 years | TLR |

| Adult health check 55+ | Number and proportion of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander clients who have had a full adult health check. | Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander resident clients aged ≥55 years | TLR |

NT AHKPI, Northern Territory Aboriginal Health Key Performance Indicator data; TLR, traffic light reports.

Statistical approach

The associations between markers of staff employment stability (independent variables) and markers of quality (dependent variables) were assessed using linear regression which employed the linearisation method31 to estimate the within-clinic correlation and adjust standard errors accordingly. Each dependent variable was expressed as the sequential change from the previous period (month, quarter or half year) to express change in indicator status. Due to the non-normal distribution of some outcome variables, formal statistical inference employed the non-parametric bootstrap method. The direction and strength of the associations between independent variables and dependent variables is reported through the regression slopes (β coefficients) along with 95% CI upper and lower limits and two-tailed p values. Analyses adjusted for potential confounders. It is noted that this is an exploratory study, the first of its kind in this environment, and therefore no allowance for multiple hypothesis testing has been made. We, therefore, interpret statistically significant results as indicative rather than definitive.

Clinic-specific estimates of the associations between independent variables and dependent variables were also calculated using linear regression and the SD of coefficients is reported as a measure of between-clinic variation in the influence of markers of staff employment stability on quality of care. To facilitate understanding of the proportion of clinics that experience positive, negative or no association with a given measures of staffing, standardised coefficient were classified as ≤−0.1, >−0.1 to <0.1 and ≥0.1.

Considerable between-clinic heterogeneity was identified. To aid in understanding clinic profiles that are associated with stronger or weaker associations, clinics were clustered into mutually exclusive groups based on their markers of staff employment stability using latent class models.32 A cluster membership probability is calculated for each cluster for each clinic and clinics are allocated to the cluster for which they have highest probability of membership. Variation between clusters of clinics with respect to association (slopes) between markers of staff employment stability and quality measures were examined to generate hypotheses concerning clinic factors that might counter the effects of reduced staffing stability or increased turnover or use of agency nurses. The clustering process can be hindered by multivariate outliers that have undue influence on the cluster solution.33 34 For this reason, a two-cluster solution was set as a first step in which forty-four clinics were allocated to one cluster and just four into the second. The analysis was then repeated on the forty-four remaining clinics. The four clinics omitted from the latent class analysis reported (due to them being outliers that could unduly influence further analysis) were statistically significantly associated with lower stability (p=0.04), higher turnover (p=0.002) and lower proportional use of agency nurses (p=0.004). Quality-of-care measures for the four clinics that were omitted from the modelling as multivariate outliers were also compared with the clinics included in the analysis. Given the very small number of clinics omitted it is difficult to make any firm conclusions, and no differences reached statistical significance, but there was a general trend for these clinics to have lower rates of meeting quality criteria.

Patient and public involvement

It was not appropriate or possible to involve patients or the public in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of the research reported here. Nevertheless, this study formed part of a broader project which used mixed-methods, including interviews and focus group discussions with clinic users. The results of the broader project were disseminated to participants and the analysis of the broader project informed the interpretation of this study’s findings and discussion.

Results

Included clinics were relatively small with respect to staffing (table 3) and located long distances from the major NT centres of Darwin and Alice Springs, on average 304 km (SD=191) from the nearest of these. The average clinic had 4–5 staff at any point in time although there was considerable variation between clinics with some having less than one and others almost 20. Similarly, there was considerable between-clinic variation in the measures of turnover, stability and use of short-term staff, with some clinics having mean scores approximately twice the overall average. Agency nurses made up a little under 20% of remote staff, on average, although these values also varied considerably between clinics with the highest being over 40%.

Table 3.

NT Department of Health clinics, characterised by staff employment stability indicators and quality indicators, 2011–2015

| Characteristics | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Number of clinics |

| Markers of staff employment stability | |||||

| Average annual head count | 4.5 | 3.8 | 0.28 | 19.17 | 48 |

| Turnover rate | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.18 | 48 |

| Stability rate | 0.4 | 0.14 | 0 | 0.77 | 48 |

| Agency nurse proportion | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.42 | 48 |

| Quality indicators* | |||||

| First antenatal visit | 0.49 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.96 | |

| (1. Before 13 weeks’ gestation) | 47 | ||||

| First antenatal visit | 0.72 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 1 | |

| (2. At or before 20 weeks’ gestation) | 47 | ||||

| First antenatal visit | 0.98 | 0.04 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| (3. Any antenatal care) | 47 | ||||

| Fully immunised children (6–11 months) | 0.88 | 0.08 | 0.63 | 1 | 47 |

| Fully immunised children (12–23 months) | 0.83 | 0.12 | 0.54 | 1 | 47 |

| Fully immunised children (24–71 months) | 0.8 | 0.08 | 0.58 | 0.935 | 47 |

| Fully immunised children (any age) | 0.81 | 0.08 | 0.6 | 0.93 | 47 |

| Anaemia test | 0.78 | 0.09 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 47 |

| Anaemia result | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.3 | 47 |

| Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) test | 0.92 | 0.04 | 0.84 | 1 | 46 |

| HbA1c result ≤8% | 0.48 | 0.1 | 0.23 | 0.71 | 47 |

| ACE Inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker | 0.84 | 0.1 | 0.59 | 1 | 46 |

| Non-smoking | 0.52 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.73 | 47 |

| Adult health check 55+ | 0.34 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.72 | 47 |

| Adult health check 15–54 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.75 | 47 |

| Pap smear 2 years | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.2 | 0.79 | 47 |

| Pap smear 3 years | 0.4 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.55 | 47 |

| Pap smear 5 years | 0.46 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.56 | 47 |

*One of the 48 health clinics did not independently report on any quality indicators during the study period. A second health clinic did not report on HbA1c tests and ACE inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker quality indicators

NT, Northern Territory.

The proportion of resident Aboriginal clients receiving high-quality care as measured by the various quality indicators varied considerably across indicators and clinics (with some variation also evident by dataset). On average, high-quality care was more likely to be received for management of chronic disease such as diabetes and least likely to be received for general/preventive adult health checks. Many indicators used in the Traffic Light Report programme had target goals of 0.80. These target goals were mostly not achieved.

The evidence for associations between markers of staff employment stability and reduced performance as measured by markers of quality was not supported as hypothesised. For the majority of associations reported in table 4, the overall effect sizes (slopes) were small (close to zero) and failed to reach statistical significance. Where statistically significant associations were found, however, they were generally in the hypothesised direction. Examples include increased turnover being associated with lower proportions of eligible women having pap smears within the previous 5 years and lower proportions of children being fully immunised (6–11 months); and increased stability associated with glycaemic control (HbA1c ≤8%). There were however exceptions, such as where increased turnover was associated with higher achievement of adult 55+ health checks.

Table 4.

Associations between markers of staff employment stability and quality indicators

| Indicator | Staffing measure | Slope* | 95% CI | P value | SD† | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| First antenatal visit (before 13 weeks’ gestation) | Turnover | 0.023 | −0.01 | 0.056 | 0.2 | 0.33 |

| Agency nurse | −0.06 | −0.178 | 0.059 | 0.3 | 1.03 | |

| Stability | 0.001 | −0.113 | 0.115 | >0.9 | 0.55 | |

| First antenatal visit (at or before 20 weeks’ gestation) | Turnover | 0.026 | −0.018 | 0.07 | 0.3 | 0.27 |

| Agency nurse | −0.088 | −0.231 | 0.056 | 0.2 | 1.1 | |

| Stability | 0.008 | −0.091 | 0.107 | 0.9 | 0.44 | |

| First antenatal visit (any antenatal care) | Turnover | −0.001 | −0.006 | 0.004 | 0.7 | 0.13 |

| Agency nurse | 0.015 | −0.028 | 0.058 | 0.5 | 0.38 | |

| Stability | 0.007 | −0.015 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.27 | |

| Fully immunised children (6–11 months) | Turnover | −0.061 | −0.119 | −0.002 | 0.04 | 0.36 |

| Agency nurse | 0.022 | −0.135 | 0.179 | 0.8 | 1.21 | |

| Stability | 0.011 | −0.073 | 0.095 | 0.8 | 0.51 | |

| Fully immunised children (12–23 months) | Turnover | −0.001 | −0.017 | 0.015 | 0.9 | 0.16 |

| Agency nurse | −0.049 | −0.155 | 0.057 | 0.4 | 0.63 | |

| Stability | −0.017 | −0.062 | 0.028 | 0.5 | 0.25 | |

| Fully immunised children (24–71 months) | Turnover | −0.012 | −0.03 | 0.006 | 0.2 | 0.11 |

| Agency nurse | −0.056 | −0.122 | 0.009 | 0.09 | 0.43 | |

| Stability | 0.002 | −0.034 | 0.037 | 0.9 | 0.23 | |

| Fully immunised children (any age) | Turnover | 0.002 | −0.008 | 0.013 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Agency nurse | −0.061 | −0.118 | −0.005 | 0.03 | 0.38 | |

| Stability | 0.004 | −0.025 | 0.033 | 0.8 | 0.19 | |

| Anaemia result | Turnover | 0.011 | −0.025 | 0.048 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| Agency nurse | 0.019 | −0.055 | 0.093 | 0.6 | 0.62 | |

| Stability | 0.042 | −0.008 | 0.092 | 0.1 | 0.24 | |

| Anaemia test | Turnover | 0.017 | 0 | 0.034 | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| Agency nurse | 0.023 | −0.046 | 0.092 | 0.5 | 0.55 | |

| Stability | 0.002 | −0.041 | 0.045 | >0.9 | 0.32 | |

| Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) test | Turnover | −0.006 | −0.024 | 0.012 | 0.5 | 0.11 |

| Agency nurse | −0.003 | −0.076 | 0.07 | 0.9 | 0.57 | |

| Stability | 0.015 | −0.015 | 0.044 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| HbA1c result | Turnover | −0.006 | −0.022 | 0.01 | 0.5 | 0.24 |

| Agency nurse | 0.037 | −0.026 | 0.101 | 0.3 | 0.27 | |

| Stability | −0.036 | −0.066 | −0.007 | 0.02 | 0.26 | |

| ACE Inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker | Turnover | −0.025 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.2 | 0.24 |

| Agency nurse | 0.053 | −0.104 | 0.21 | 0.5 | 0.35 | |

| Stability | 0.044 | −0.01 | 0.097 | 0.1 | 0.34 | |

| Non-smoking | Turnover | −0.007 | −0.019 | 0.005 | 0.3 | 0.28 |

| Agency nurse | 0.005 | −0.043 | 0.053 | 0.8 | 0.28 | |

| Stability | −0.005 | −0.033 | 0.023 | 0.7 | 0.29 | |

| Adult health check aged 15–55 | Turnover | 0.031 | −0.003 | 0.066 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| Agency nurse | 0.129 | −0.036 | 0.294 | 0.1 | 0.59 | |

| Stability | −0.056 | −0.119 | 0.006 | 0.08 | 0.38 | |

| Adult health check aged 55+ | Turnover | 0.024 | −0.04 | 0.087 | 0.5 | 0.21 |

| Agency nurse | 0.265 | 0.073 | 0.457 | 0.007 | 1.01 | |

| Stability | −0.027 | −0.145 | 0.091 | 0.7 | 0.56 | |

| Pap smear 2 years | Turnover | −0.007 | −0.019 | 0.005 | 0.2 | 0.09 |

| Agency nurse | −0.058 | −0.127 | 0.011 | 0.1 | 0.47 | |

| Stability | 0.006 | −0.038 | 0.051 | 0.8 | 0.2 | |

| Pap smear 3 years | Turnover | −0.021 | −0.038 | −0.004 | 0.01 | 0.18 |

| Agency nurse | −0.053 | −0.137 | 0.03 | 0.2 | 0.73 | |

| Stability | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.2 | 0.51 | |

| Pap smear 5 years | Turnover | −0.023 | −0.041 | −0.005 | 0.01 | 0.2 |

| Agency nurse | −0.048 | −0.155 | 0.059 | 0.4 | 0.83 | |

| Stability | 0.057 | −0.03 | 0.143 | 0.2 | 0.59 | |

*Slope=β coefficient.

†SD of clinic-specific estimates of association.

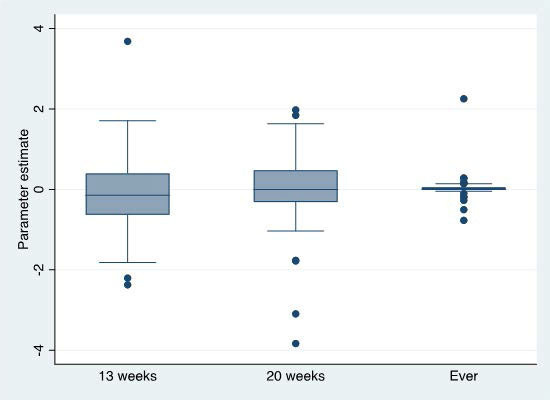

A common finding was considerable between-clinic variation in markers of staff employment stability and quality indicators, although the degree of variation between clinics was inconsistent and differed with different levels of a quality indicator. Figure 1 illustrates this for the association between proportion of agency nurse and three levels of provision of antenatal care where the median slope is close to zero for all three levels of the antenatal care indicator. During the first and second trimester, the association with proportion of agency nurses appears to vary widely between positive and negative values while for receiving care at any time before the end of pregnancy there is relatively little between-clinic variation. In this example, if we calculate standardised mean differences based on the SD of the 13 week clinic-specific estimates and classify each clinic’s estimate as negative, effectively zero or positive based on thresholds of ≤−0.1, between −0.1 and +0.1 or ≥0.1 the percentage of clinics with negative, nil or positive associations with agency nurse proportion were 53%, 7%, 40% (respectively) at 13 weeks, 44%, 14%, 42% at 20 weeks and 12%, 65%, 23% by end of pregnancy. Hence the overall association effect size can hide considerable variation in the direction and magnitude of association in individual clinics.

Figure 1.

Distribution of clinic-specific associations between proportional use of agency nurses and antenatal care quality of care indicators.

Subsequent to finding the considerable variation between clinics described above, latent class analysis was undertaken which identified three clusters of clinics (columns labelled 1, 2 and 3 in table 5) which appear to represent a gradient in the markers of staff employment stability. Cluster 1 is distinguished by comparatively high service populations, larger staff numbers and correspondingly high mean number of staff exits but also high variance in staff exits over time. This cluster has levels of average stability and turnover that are in between those of clusters 2 and 3. The second cluster services smaller populations than cluster 1 and has correspondingly smaller staff numbers. It also has comparatively low average and variance in staff exits, lower turnover and higher stability scores, hence represents a hypothetically desirable group of clinics on average. The third cluster services the smallest populations, on average, and has correspondingly the lowest average staff numbers. It lies between the first and second with lower mean and variance over time in staff exits than cluster 1 but has the highest turnover (indicative of smaller clinic size than cluster 1 clinics), the lowest stability and the highest proportional use of agency nurses, hence represents a hypothetically undesirable group of clinics on average. There was overall less variation in the mean proportion of agency nurses between clusters, with cluster 2 having the lowest proportion (17%) and cluster 3 the highest (20%).

Table 5.

NT Department of Health clinic clusters, characterised by staff employment stability indicators, geographical remoteness and socioeconomic disadvantage, 2011–2015

| Mean | SD | |||||

| Cluster no | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| No of clinics | 9 | 16 | 19 | 9 | 16 | 19 |

| Average* | ||||||

| Staff count | 10.2 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 4.6 | 2.3 | 0.9 |

| Staff exits | 2.2 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Turnover rate | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Stability rate | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Agency nurse proportion | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Within-clinic SD† | ||||||

| Staff count | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Staff exits | 2.2 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Turnover rate | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Stability rate | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Agency nurse proportion | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Time-invariant | ||||||

| Population (2015) | 1391 | 505 | 338 | 1012 | 395 | 229 |

| Index of relative socioeconomic advantage and disadvantage | 652 | 746 | 709 | 84 | 122 | 137 |

| Google distance to darwin or alice springs | 313 | 267 | 332 | 222 | 167 | 220 |

| Predominantly non-aboriginal: % (count) | 0.0 | 6.3 | 15.8 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

*Based on calculating a single average per clinic over the recording period.

†Based on calculating a single SD per clinic over the recording period.

NT, Northern Territory.

In general, there was not clinically meaningful and statistically significant variance in quality indicator achievement between clusters (table 6). Exceptions were lower use of ACE Inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker in cluster 1 than clusters 2 and 3 and higher rates of childhood anaemia in clinics in cluster 1 than in clusters 2 and 3. However, in general, the clusters are not differentiated with respect to indicators of quality of care.

Table 6.

Associations between NT Department of Health clinic clusters and quality indicators, 2011–2015

| Mean | SD | |||||||

| Cluster | Overall | Cluster | Overall | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| First antenatal visit by 13 weeks | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| First antenatal visit by 20 weeks | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| First antenatal visit any time | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Child immunisation 6–11 m | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Child immunisation 12–23 m | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Child immunisation 24–71 m | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Child immunisation (all) | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Anaemia test | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Anaemia result* | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) test | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| HbA1c result | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.10 |

| ACE Inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker* | 0.74 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Non-smoking | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| Adult health check aged 15–54 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Adult health check aged 55+ | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.15 |

| Pap smear 2 years | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| Pap smear 3 years | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Pap smear 5 years | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

*P<0.001.

NT, Northern Territory.

Table 7 presents the mean association effect sizes across clusters according to the markers of staff employment stability and quality indicator combinations. In general, clusters did not differ substantially or in a statistically significant way with respect to strength/direction of the association. Exceptions included the association between stability and antenatal care at any time during pregnancy for which cluster 1 reported a statistically significant negative association; and pap smears at 2 years, for which cluster 1 reported a statistically significant positive association with stability. All other clusters reported no association.

Table 7.

Variation in mean associations between NT Department of Health clinic clusters and quality indicators, 2011–2015

| Stability | Turnover | Agency nurse % | |||||||

| Cluster | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| First antenatal visit 13 weeks | 0.176 | −0.012 | −0.110 | −0.058 | 0.061 | 0.013 | 0.029 | 0.002 | −0.289 |

| First antenatal visit 20 weeks | 0.180 | 0.065 | −0.046 | −0.020 | 0.023 | −0.091 | 0.101 | 0.084 | −0.261 |

| First antenatal visit any | −0.050* | −0.113 | 0.054 | −0.015 | 0.023 | −0.038 | −0.082 | 0.201 | −0.018 |

| Immunisation 6–11 months | 0.115 | −0.181 | 0.026 | −0.155 | 0.011 | 0.117 | 0.087 | −0.263 | 0.304 |

| Immunisation 12–23 months | 0.083 | 0.113 | −0.079 | 0.002 | 0.012 | 0.039 | 0.075 | −0.106 | 0.362 |

| Immunisation 24–71 months | 0.114 | 0.107 | −0.002 | 0.057 | 0.039 | −0.005 | −0.174 | −0.303 | −0.117 |

| Immunisation overall | 0.128 | 0.098 | −0.008 | 0.031 | 0.034 | −0.010 | −0.106 | −0.242 | −0.016 |

| Anaemia test | 0.162 | 0.027 | 0.107 | −0.000 | 0.008 | −0.032 | −0.050 | 0.034 | 0.050 |

| Anaemia result | −0.011 | −0.023 | 0.065 | −0.016 | −0.001 | 0.006 | −0.032 | 0.118 | 0.142 |

| Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) test | 0.115 | −0.467 | 0.152 | 0.311 | 0.050 | −0.033 | 0.298 | −0.392 | −0.352 |

| HbA1c result | −0.060 | 0.048 | 0.233 | −0.078 | 0.014 | 0.039 | −0.020 | −0.183 | −0.060 |

| ACE Inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker | −1.048 | −0.015 | 0.000 | −0.615 | −0.257 | −0.046 | 0.298 | −0.392 | −0.352 |

| Non-smoking | 0.067 | 0.012 | −0.017 | 0.024 | 0.037 | −0.019 | −0.021 | 0.002 | 0.122 |

| Pap smear 2 years | 0.173* | −0.015 | −0.016 | −0.037 | 0.003 | 0.024 | −0.086 | −0.101 | −0.061 |

| Pap smear 3 years | −0.331 | −0.041 | −0.012 | −0.084 | 0.061 | −0.052 | −0.070 | −0.382 | 0.054 |

| Pap smear 5 years | −0.371 | −0.065 | 0.017 | −0.086 | 0.061 | −0.058 | −0.031 | −0.385 | 0.055 |

| Adult health check 15–54 | −0.220 | −0.009 | −0.229 | −0.464 | −0.278 | −0.124 | 0.733 | 0.077 | −0.098 |

| Adult health check 55+ | −0.478 | 0.218 | −0.382 | −0.403 | −0.169 | −0.126 | 2.825 | 0.310 | 0.315 |

*P<0.05.

NT, Northern Territory.

Discussion

Overall, minimal evidence of the hypothesised negative effects of increased turnover, decreased stability and increased reliance on temporary staff on quality of care was found. In a small number of cases, there were statistically significant associations in the hypothesised direction, a smaller number in a direction opposite to that hypothesised, but the majority yielded overall association measures (slopes) that were close to zero and failed to reach statistical significance (table 2). While these findings could indicate that the hypothesised negative effects of staffing instability on quality of care are not supported by the evidence, there are several pointers that on-the-ground reality might not be that simple. First, while the overall estimates of association were all close to zero, there was substantial variation in the clinic-specific estimates, meaning that in some clinics quality was negatively associated with higher turnover, lower stability and higher use of short-term staff but in other clinics quality was unrelated or even positively related with these measures. The latter, counter-hypothesised results might reflect random chance but they might also reflect clinic-specific factors that counter the potential negative effects of decreased workforce stability, increased turnover and increased use of short-term staff. An illustration of the fraction of clinics with negative, effectively zero or positive associations was given for antenatal care as the quality indicator and proportion of agency nurses as the stability measure. Where the association was clearly not statistically significant 65% of clinics had estimate associations that were effectively zero, with the remainder split between some degree of negative or positive associations. A clustering of clinics based on markers of staff employment stability failed to yield clinic groupings that explain the between-clinic variation in associations (table 7).

Alternate explanations of this variability might include a number of unquantified local factors. For example, a competent clinic manager may be able to manage an unstable workforce more effectively, thus mitigating the deficits that might otherwise have occurred.35 A robust Continual Quality Improvement programme, visiting outreach health staff and clinic-level data reports may also counter any negative effects of employment instability. Heavy reliance on short-term agency nurses might not be as detrimental as hypothesised if some of these nurses return repeatedly to the same clinic or group of clinics, and thus have local knowledge and long-standing relationships with residents which facilitate continuity of care.36 Or it may be that in some instances skilled agency nurses enable resident RANs to take planned annual leave or undertake professional development, rather than having a stream of inexperienced or poorly prepared agency nurses filling longstanding vacancies at short notice.35 In these ways, the administrative data might indicate greater instability in the workforce than is actually experienced in terms of continuity of care on the ground.

Other factors that cannot be readily quantified that may contribute to the observed variability include both the clinical and cultural competence of short-term health staff.35 The acceptability of the service to local residents is not only a function of the cultural competence of non-aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander staff, but also the presence of aboriginal staff, both clinical and non-clinical staff such as administrative officers, drivers and groundsmen. These non-clinical staff are often long-serving and knowledgeable. Their varying numbers across clinics may also help to explain the variability in the results presented.35 37

Given the high healthcare needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations living in remote communities, and the importance of ensuring equitable access to high-quality PHC, future research is warranted to explore whether and how the range of factors postulated as possible explanations are indeed associated with the substantial between-clinic variation in quality of primary care in remote clinics. The authors are currently undertaking some of this work by examining whether similar patterns exist in Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services in the same jurisdiction and will be updating analyses with NT DoH data to try and gain a better understanding of the extent to which a range of factors identified as differentiating Indigenous PHC models from mainstream services, such as cultural safety, having a culturally appropriate and skilled Indigenous workforce and increased acceptability of the health service to community members are associated with variability in quality of care.38 39

Limitations

This study relied on territory-wide, routinely collected data to test its hypotheses rather than collecting data prospectively using definitions and in formats that might have been optimal for the purpose. The routine collection is used to guide service delivery and is routinely reported at both NT and national levels. Its use for this study was not only guided by feasibility but also to demonstrate the wider utility of the collection. Nonetheless the use of the existing collection contributed to both measurement noise and definitional challenges which made underlying associations less evident. For example, the use of agency nurses in NT DoH remote clinics are recorded either in payroll data or in expenditure data, depending on the payment arrangements that NT DoH has with each nursing agency. For this study agency nurses recorded in the NT DoH payroll were included in turnover and stability figures, whereas work by agency nurses recorded in expenditure data were included in the estimation of agency nurse proportion. A further limitation related to our choice of workforce indicators. Given the dearth of literature describing health workforce metrics specific to the Australian remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander context, our choice of health workforce indicators was guided by literature taken from the rural Australian context.27 The metrics we chose were unable to capture all important facets of the remote health workforce, including, for example, employment of local Aboriginal staff. Our study used a selection of clinical indicators of quality of care. Other than the aforementioned employment stability indicators, no non-clinical indicators were used. Thus, even though it is recognised that characteristics such as culture, community participation and self-determination are important for providing high-quality Indigenous PHC services, indicators measuring there were not included. Additionally, no data were available on the proportion of patients with cardiovascular disease on acetylsalicylic acid, so even though measurement of this outcome was described in the study protocol, this indicator was not used. A further limitation was that it was not possible to allocate staff working in a supernumerary capacity in a remote health clinic to that clinic as this was not recorded in the administrative records used. Finally, the research relates to a very specific context of government-provided PHC in small, remote NT communities and the findings may not be generalisable to other health systems, service models, geographical settings or study populations.

Conclusion

Overall, minimal evidence of the hypothesised negative effects of increased turnover, decreased stability and increased reliance on temporary staff on quality of care was found. Substantial variations in clinic-specific estimates of association were evident, suggesting that clinic-specific factors may counter any potential negative effects of decreased staff employment stability. Investigation of clinic-specific factors using latent class analysis failed to yield clinic characteristics that adequately explain between-clinic variation in associations. Understanding the reasons for this variation would significantly aid the provision of clinical care in remote Australia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Northern Territory Department of Health staff who provided technical assistance in accessing and interpreting departmental personnel, primary healthcare, hospitalisation and financial data. The authors also acknowledge and sincerely thank all staff working in the remote NT communities, particularly the clinic managers.

Footnotes

Contributors: MPJ contributed to the design of the study and led analysis and drafting of the paper. MPJ acts as gaurantor of the article. JW led the conceptualisation and overall study design and contributed to drafting the paper. JSH contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study and assisted with drafting the manuscript. SG, YZ, MR and DJR contributed to the design of the study and assisted with drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (project number DP150102227). The funder had no input in to the design, conduct and reporting of this analysis.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Author note: Original protocol for the study: The original protocol for the study is published and available (open access): Wakerman J, Humphreys JS, Bourke L, Dunbar T, Jones M, Carey T, et al. Assessing the impact and cost of short-term health workforce in remote Indigenous communities in Australia: a mixed methods study protocol. JMIR research protocols. 2016;5(4):e135.

Data availability statement

No data are available. The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to identifiability of remote primary health care providers and the need to protect their privacy.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was received from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Territory Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research (2015-2363).

References

- 1.Australian Government . The Australian continent, 2019. Available: https://www.australia.gov.au/about-australia/our-country/the-australian-continent [Accessed 11 Feb 2019].

- 2.ABS . ABS 2020 regional population growth, Australia, 2018-19. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Bureau of Sstatistics . ABS 2011 census of population and housing data generated using ABS TableBuilder. Canberra: ABS, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Australian burden of disease study: fatal burden of disease in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2010. Australian burden of disease study series No. 2. Cat. no. BOD 2. Canberra: AIHW, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Georges N, Guthridge SL, Li SQ, et al. Progress in closing the gap in life expectancy at birth for Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory, 1967-2012. Med J Aust 2017;207:25–30. 10.5694/mja16.01138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maarsingh OR, Henry Y, van de Ven PM, et al. Continuity of care in primary care and association with survival in older people: a 17-year prospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e531–9. 10.3399/bjgp16X686101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minore B, Boone M, Katt M, et al. The effects of nursing turnover on continuity of care in isolated first nation communities. Can J Nurs Res 2005;37:86–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menec VH, Sirski M, Attawar D, et al. Does continuity of care with a family physician reduce hospitalizations among older adults? J Health Serv Res Policy 2006;11:196–201. 10.1258/135581906778476562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker I, Steventon A, Deeny S. Continuity of care in general practice is associated with fewer ambulatory care sensitive hospital admissions: a cross-sectional study of routinely collected, person-level data. Clin Med 2017;17:s16. 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-3-s16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mason J. Review of Australian government health workforce programs. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbon P, Hales J. Review of the rural retention program. final report. Kent Town, SA: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walters LK, McGrail MR, Carson DB, et al. Where to next for rural general practice policy and research in Australia? Med J Aust 2017;207:56–8. 10.5694/mja17.00216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakerman J, Curry R, McEldowney R. Fly in/fly out health services: the panacea or the problem? Rural Remote Health 2012;12:2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerin P, Guerin B. Social effects of fly-in-fly-out and drive-in-drive-out services for remote Indigenous communities. Aust Comm Psychol 2009;21:8–23. [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Walraven C, Oake N, Jennings A, et al. The association between continuity of care and outcomes: a systematic and critical review. J Eval Clin Pract 2010;16:947–56. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowley KG, O'Dea K, Anderson I, et al. Lower than expected morbidity and mortality for an Australian Aboriginal population: 10-year follow-up in a decentralised community. Med J Aust 2008;188:283–7. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas SL, Zhao Y, Guthridge SL, et al. The cost-effectiveness of primary care for Indigenous Australians with diabetes living in remote Northern Territory communities. Med J Aust 2014;200:658–62. 10.5694/mja13.11316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y, Wright J, Guthridge S, et al. The relationship between number of primary health care visits and hospitalisations: evidence from linked clinic and hospital data for remote Indigenous Australians. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:466. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saint-Pierre C, Prieto F, Herskovic V, et al. Relationship between continuity of care in the multidisciplinary treatment of patients with diabetes and their clinical results. Applied Sciences 2019;9:268. 10.3390/app9020268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lustman A, Comaneshter D, Vinker S. Interpersonal continuity of care and type two diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes 2016;10:165–70. 10.1016/j.pcd.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Younge R, Jani B, Rosenthal D, et al. Does continuity of care have an effect on diabetes quality measures in a teaching practice in an urban underserved community? J Health Care Poor Underserved 2012;23:1558–65. 10.1353/hpu.2012.0193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gulliford MC, Naithani S, Morgan M. Continuity of care and intermediate outcomes of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Fam Pract 2007;24:245–51. 10.1093/fampra/cmm014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flach SD, McCoy KD, Vaughn TE, et al. Does patient-centered care improve provision of preventive services? J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:1019–26. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30395.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Busbridge MJ, Smith A. Fly in/fly out health workers: a barrier to quality in health care. Rural Remote Health 2015;15:3339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Northern Territory Government Department of Health . Indicator definition: full time equivalents v1.0. Darwin: NTG Department of Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burgess CP, Sinclair G, Ramjan M, et al. Strengthening cardiovascular disease prevention in remote indigenous communities in Australia’s Northern Territory. Heart Lung Circ 2015;24:450–7. 10.1016/j.hlc.2014.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell DJ, Humphreys JS, Wakerman J. How best to measure health workforce turnover and retention: five key metrics. Aust Health Rev 2012;36:290–5. 10.1071/AH11085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Northern Territory Department of Health . Remote area nurse safety: on-call after hours security. Darwin: NT: Department of Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.ABS . Technical paper: socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2011 census quickStats, 2013. Available: https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/quickstat/0 [Accessed 21 Jun 2021].

- 31.Kish L. Survey sampling. New York, London: John Wiley & Sons Inc, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagenaars JA, McCutcheon AL. Applied latent class analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang MF, Tseng SS, Su CM. Two-Phase clustering process for outliers detection. Pattern Recognit Lett 2001;22:691–700. 10.1016/S0167-8655(00)00131-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, Shan H, Banerjee A. Bayesian cluster ensembles. Stat Anal Data Min 2011;4:54–70. 10.1002/sam.10098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunbar T, Bourke L, Murakami-Gold L. More than just numbers! perceptions of remote area nurse staffing in Northern Territory government health clinics. Aust J Rural Health 2019;27:245–50. 10.1111/ajr.12513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bourke L, Dunbar T, Murakami-Gold L. Discourses within the roles of remote area nurses in Northern Territory (Australia) government-run health clinics. Health Soc Care Community 2021;29:1401–8. 10.1111/hsc.13195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Y, Russell DJ, Guthridge S, et al. Long-term trends in supply and sustainability of the health workforce in remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory of Australia. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:836. 10.1186/s12913-017-2803-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harfield SG, Davy C, McArthur A, et al. Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Global Health 2018;14:12. 10.1186/s12992-018-0332-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laverty M, McDermott DR, Calma T. Embedding cultural safety in Australia's main health care standards. Med J Aust 2017;207:15–16. 10.5694/mja17.00328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to identifiability of remote primary health care providers and the need to protect their privacy.