This systematic review and meta-analysis reports the risk of self-harm, including self-injurious behaviors and suicidality, among pediatric and adult populations with autism spectrum disorder.

Key Points

Question

What excess risk of self-harm, including self-injurious behaviors and suicidality, is associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD)?

Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 31 studies found that the pooled odds of self-harm in people with ASD was more than 3 times the odds in people without ASD. The excess odds of self-harm were found in both children and adults (although a slightly higher risk was identified in adults) across geographic regions and regardless of study designs, methods, and settings.

Meaning

Findings of this study suggest that children and adults with ASD are at a substantially increased risk for self-injurious behavior and suicidality.

Abstract

Importance

Multiple studies have reported that people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are at a higher risk for self-injurious behavior and suicide. However, the magnitude of this association varies between studies.

Objective

To appraise the available epidemiologic studies on the risk of self-injurious behavior and suicidality among children and adults with ASD.

Data Sources

PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Web of Science were systematically searched for epidemiologic studies on the association between ASD and self-injurious behavior and suicidality. Databases were searched from year of inception to April through June 2020. No language, age, or date restrictions were applied.

Study Selection

This systematic review and meta-analysis included studies with an observational design and compared self-injurious behavior (defined as nonaccidental behavior resulting in self-inflicted physical injury but without intent of suicide or sexual arousal) and/or suicidality (defined as suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or suicide) in children (aged <20 years) or adults (aged ≥20 years) with ASD.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Information on study design, study population, ASD and self-harm definitions, and outcomes were extracted by independent investigators. Study quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Overall summary odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were estimated using DerSimonian-Laird random-effects models.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The ORs for the associations of ASD with self-injurious behavior and suicidality were calculated. Analyses were stratified by study setting and age groups as planned a priori.

Results

The search identified 31 eligible studies, which were of moderate to high quality. Of these studies, 16 (52%) were conducted in children, 13 (42%) in adults, and 2 (6%) in both children and adults. Seventeen studies assessed the association between ASD and self-injurious behavior and reported ORs that ranged from 1.21 to 18.76, resulting in a pooled OR of 3.18 (95% CI, 2.45-4.12). Sixteen studies assessed the association between ASD and suicidality and reported ORs that ranged from 0.86 to 11.10, resulting in a pooled OR of 3.32 (95% CI, 2.60-4.24). In stratified analyses, results were consistent between clinical and nonclinical settings and between children and adults.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found that ASD was associated with a substantial increase in odds of self-injurious behavior and suicidality in children and adults. Further research is needed to examine the role of primary care screenings, increased access to preventive mental health services, and lethal means counseling in reducing self-harm in this population.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction along with restricted, repetitive behaviors.1 In 2017, an estimated 5 437 988 US adults (2.21%) had ASD.2 Prevalence estimates in the US pediatric population have increased over the past several decades partly because of improved awareness, changes in documentation, and identification of milder cases without intellectual disability.3 In 2016, 1 in 59 children aged 8 years met surveillance criteria for ASD, and 1 in 40 children aged 3 to 17 years had a parent-reported ASD diagnosis.4,5

Among the myriad potential health problems for people with ASD is the excess risk of injury morbidity and mortality. Several epidemiologic studies using emergency department visit data have shown that children with ASD are at an elevated risk for injuries.6,7,8,9,10 Epidemiologic evidence has also indicated that people with ASD are at a heightened risk of injury mortality, with a risk of premature death that is 2- to 10-fold higher than in the general population.11,12,13,14 Self-harm may be a factor in this excess injury mortality given that people with ASD have a greater risk of self-injurious behavior, suicidal ideation, and suicide, although the estimated odds ratios (ORs) of self-harm in this population vary from 0.86 to 18.76.15,16,17,18

Several factors may explain the variability of existing estimates of self-harm risk in people with ASD, including common co-occurring mental health conditions that are associated with an increased risk of suicide.19,20,21 Pooled prevalence estimates demonstrate that 28% of people with ASD have co-occurring attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 20% have co-occurring anxiety disorders, and 11% have co-occurring depressive disorders.22 These diagnoses are associated with a higher risk of suicide and increased prevalence of self-harm in this population. Estimates also vary among studies because of the outcome measures and comparison groups chosen, small sample sizes, and inclusion of clinical vs nonclinical samples.

Estimates may also vary depending on the definition of self-harm. Self-injurious behavior, such as hand hitting, self-cutting, or hair pulling, is common in the population with ASD, with an estimated prevalence of 42%.23 Self-injurious behavior is known to be associated with suicide, which has been documented in people with or without ASD.12,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 Among adolescents, nonsuicidal self-injury is associated with a markedly increased risk of suicide attempt (hazard ratio, 5.28; 95% CI, 1.80-15.47).25 This association is well established across the age spectrum.32 In a survey of people with ASD, Moseley et al24 found that every 1-point increase in score on the suicide item of the self-administered Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire was associated with a 2.2-fold increase in the risk of self-harm.

More precise estimates are needed to improve the recognition of and evidence-based interventions for self-harm in children and adults with ASD. In this systematic review with meta-analysis, we appraised the available epidemiologic studies on the risk of self-injurious behavior and suicidality among children and adults with ASD.

Methods

We registered this systematic review and meta-analysis with PROSPERO (CRD42020175223) at the onset of the project; eMethods 1 in the Supplement describes deviations from the protocol. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline33 and the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) reporting guideline.

Study Eligibility, Search Strategy, and Study Selection

Studies were eligible if they (1) had an observational design, such as cohort, case-cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional; (2) included the exposure group as ASD, which was ascertained by standardized tools, medical professionals, or International Classification of Diseases codes; (3) used an appropriate comparison group without ASD (eg, the general population or participants with non-ASD neurobehavioral disorder); (4) compared the prevalence or incidence of self-injurious behavior, suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or suicide between those with ASD and those without ASD; and (5) presented quantitative data and at least 1 measure of association between ASD and self-injurious behavior or suicidality. Relevant literature was identified through a comprehensive search of PubMed (from 1996 to April 19, 2020), Embase (from 1980 to May 13, 2020), CINAHL (from 1982 to June 16, 2020), PsycINFO (from 1967 to June 16, 2020), and Web of Science (from 1900 to June 23, 2020). No language, age, or date restrictions were applied. The Boolean searches were completed with the assistance of a medical informationalist who specializes in systematic reviews and used relevant keywords and database-specific controlled vocabulary terms; the search strategies are available in eMethods 2 in the Supplement. Embase weekly search alerts were used from May 13, 2020, to January 31, 2021, to identify additional eligible studies. To identify unpublished or gray literature, we searched relevant conference abstracts, the National Institutes of Health RePORTER database, and the websites of organizations that are involved in ASD and self-injury research (eg, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, and National Institute of Mental Health). We contacted authors of potentially eligible studies if data were missing or incomplete or if study populations seemed to be duplicates. No additional studies were obtained from author contacts or gray literature searches. Eligible studies spanned the entire age continuum; pediatric and adult studies were summarized separately.

All of the studies identified from searches were imported and deduplicated in Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation). Two of us (A.B. and S.C.) screened study titles and abstracts for eligibility. Studies that we identified as potentially eligible were then reviewed in full text to ascertain their eligibility. Discrepancies in study selection were resolved by a discussion between the 2 of us or with a third author (G.L.). Reference lists and related article links of eligible studies were searched to identify and screen additional potential studies for inclusion.

Data Extraction

Data on primary author, year of publication, country of study origin, setting, study design, sample size, comparison group, sample age, exposure assessment, outcome definition, outcome ascertainment, covariates, subgroups, and results were abstracted from included studies. Two of us (A.B. and S.C.) independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (score range: 0-9 for cohort and case-control studies and 0-10 for cross-sectional studies, with higher scores indicating higher-quality studies).34

We compared study authors, start and end dates, and data sources to identify overlapping study samples. In circumstances in which multiple studies reported outcomes on the same study sample, the study that was most relevant to the objectives of the review was included. For studies that reported separate results for self-injurious behavior and suicidality, both results were included for analysis.

To perform subgroup analyses by self-harm type, we combined studies with outcomes that were associated with suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or suicide under the term suicidality. We defined self-injurious behavior as nonaccidental behavior that resulted in self-inflicted physical injury but had no specified intent of suicide or sexual arousal.35 We stratified results according to self-harm type (ie, self-injurious behavior or suicidality), and we pooled the results given that both types of self-harm co-occur at high rates in both children and adults27,36,37,38 and may share important correlates, such as depression, compensatory regulation, and substance use disorder.39,40 Studies that included children (aged <20 years) and adults (aged ≥20 years) were included in both subgroup analyses if relevant outcomes for each age group were reported separately. When adult and pediatric age groups were not reported separately, the study was categorized as pediatric if the mean age of participants at enrollment was younger than 20 years, and the study was categorized as adult if the mean age of participants at enrollment was 20 years or older. Study setting was defined as clinical if participants were evaluated in clinical settings, such as outpatient clinics or emergency departments, or nonclinical if participants were recruited through community settings, registries, or databases.

Statistical Analysis

Pooled ORs and 95% CIs were estimated using the DerSimonian-Laird random-effects model.41 A random-effects model was chosen a priori to allow for heterogeneity across studies and generalization of findings. Meta-regressions were performed with potential moderators, including age group, setting, quality score, sample size, year of publication, sex, presence or absence of comorbid conditions (including other neuropsychiatric conditions, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and intellectual disability), and continent when at least 4 studies provided relevant data. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 tests and the Cochran Q test42,43 based on γ distribution as proposed by Kulinskaya and Dollinger.44 In addition, 95% prediction intervals were computed to estimate the variation of the true effect size (ie, the distribution of the effect sizes in comparable populations). Publication bias was assessed using the Egger and Tang tests, sample size–based funnel plots,45 and trim-and-fill funnel plots by imputing missing studies that would be needed to eliminate publication bias (ie, symmetric and inverted funnel plot) based on the L0 estimator. Summary ORs and 95% CIs were recomputed according to these imputed studies. Analyses were performed using the meta package in R and Stata, version 16 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

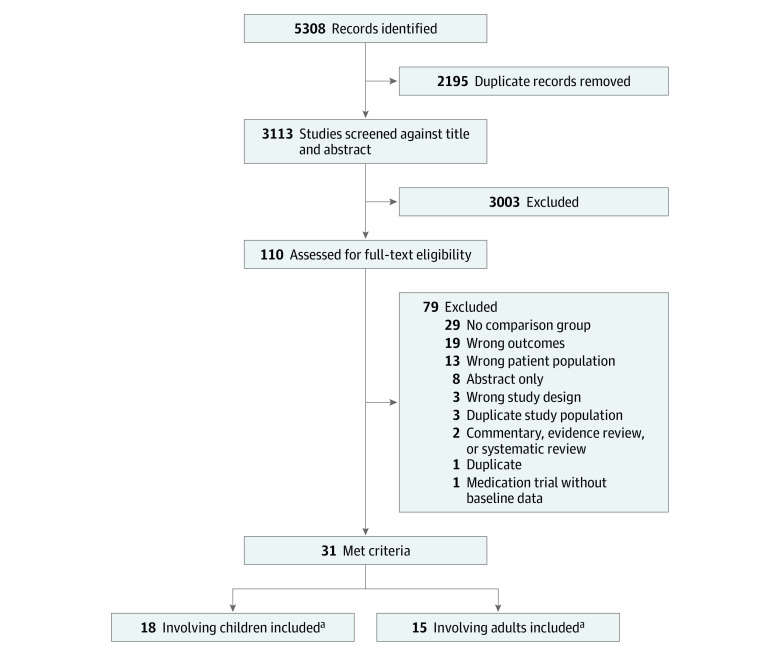

The initial database search identified 5304 records, and Embase search alerts subsequently identified 4 additional studies, resulting in a total of 5308 records (Figure 1). After removing 2195 duplicates, we screened 3113 titles and abstracts, of which 3003 were excluded during title and abstract review. After a full-text review of 110 potentially eligible studies, we excluded 79 for reasons such as lack of comparison group, wrong outcomes, or wrong or duplicate patient population, leaving 31 studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1. Study Selection.

aTwo studies involved both adults and children.

A total of 36 results were retrieved from the 31 studies.9,16,17,18,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72 Twenty-nine of the 36 results showed a significant association between ASD and self-harm,9,18,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,60,61,63,64,66,67,68,69,70,71,72 and people with ASD were at similarly increased risk of both self-injurious behavior and suicidality. Included studies were published from 1999 to 2021. Of the 5 studies with multiple observed results, 2 reported results separately for pediatric and adult populations49,64 and 3 reported results for separate relevant outcomes.48,60,72

Study Characteristics

The 31 studies were heterogeneous in the comparison group chosen, ASD ascertainment, age groups included, and study setting (Table 1). Overall, 31 studies from 11 countries were identified, including 14 studies (45%) from Europe,17,46,47,48,50,52,55,57,60,61,64,67,68,69 13 studies (42%) from North America,9,16,51,53,54,56,58,59,63,65,66,70,72 and 4 studies (13%) from Asia.18,49,62,71

Table 1. Characteristics of the Studies Included in the Meta-analysis.

| Source (country of study origin) | Sample age, y | Age group | Setting | Comparison group | Self-harm outcome | Sample size, No. | Controls for covariates? | Study design | Quality scorea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agnafors et al,46 2020 (Sweden) | 0-17 | Pediatric | Nonclinical, database | Participants without ASD or developmental delays | Self-injurious behavior | 359 597 | Yes | Cross-sectional | 10/10 |

| Buono et al,47 2010 (Italy) | 1-47 | Pediatric | Nonclinical | Participants without ID or ASD | Self-injurious behavior | 84 | No | Cross-sectional | 4/10 |

| Cassidy et al,48 2018 (England) | 20-60 | Adult | Nonclinical | Participants without ASD | Self-injurious behavior and suicidality | 333 | No | Cross-sectional | 7/10 |

| Chen et al,49 2017 (Taiwan) | 12-29 | Pediatric and adult | Nonclinical, database | Age- and sex-matched control participants without ASD diagnosis | Suicide attempt | 28 090 | Yes | Cohort | 9/9 |

| Cooper et al,50 2009 (Scotland) | ≥16 | Adult | Nonclinical | Participants without ASD | Self-injurious behavior | 1023 | No | Cohort | 7/9 |

| Croen et al,51 2015 (United States) | ≥18 | Adult | Nonclinical | Participants without ASD | Suicide attempt | 16 577 | No | Cohort | 7/9 |

| Culpin et al,17 2018 (England) | 7-16 | Pediatric | Nonclinical | Participants without ASD | Self-injurious behavior | 2720 | Yes | Cohort | 9/9 |

| Dell’Osso et al,52 2019 (Italy) | Mean age: 25.7 | Adult | Nonclinical | Participants without ASD | Suicidal ideation and suicide attempt | 194 | No | Cross-sectional | 6/10 |

| Dickerson Mayes et al,53 2015 (United States) | 6-18 | Pediatric | Clinical | Participants without neurodevelopmental disorders or prescribed psychotropic medications | Suicidal ideation and suicide attempt | 515 | No | Cross-sectional | 6/10 |

| Dominick et al,54 2007 (United States) | 4-14 | Pediatric | Nonclinical | Participants with a history of language impairment | Self-injurious behavior | 92 | No | Cross-sectional | 7/10 |

| Eden et al,55 2014 (United Kingdom) | 4-15 | Pediatric | Nonclinical | Participants with Down syndrome | Self-injurious behavior | 231 | No | Cross-sectional | 5/10 |

| Fodstad et al,56 2012 (United States) | 12-39 mo | Pediatric | Nonclinical | Participants without ASD | Self-injurious behavior | 624 | No | Cross-sectional | 7/10 |

| Folch et al,57 2018 (Spain) | 18-84 | Adult | Nonclinical | Participants with ID and without ASD | Self-injurious behavior | 833 | No | Cross-sectional | 7/10 |

| Hand et al,58 2020 (United States) | ≥65 | Adult | Nonclinical, database | Age- and sex-matched control participants without ASD | Self-injurious behavior and suicidality | 51 535 | Yes | Cross-sectional | 10/10 |

| Hardan and Sahl,59 1999 (United States) | 4-18 | Pediatric | Clinical | Participants without ASD | Suicide ideation | 193 | No | Cohort | 6/9 |

| Hirvikoski et al,60 2020 (Sweden) | 0-100 (mean age: 22) | Adult | Nonclinical, registry | Age- and sex-matched control participants without ASD, ID, or ADHD | Suicide and suicide attempt | 325 008 | Yes | Case-control | 9/9 |

| Jokiranta-Olkoniemi et al,61 2021 (Finland) | 2-28 | Pediatric | Nonclinical, registry | Participants without ASD or severe/profound ID | Self-injurious behavior and suicidality | 23 145 | Yes | Cohort | 7/9 |

| Kalb et al,9 2016 (United States) | 3-17 | Pediatric | Clinical | Participants without ASD or ID | Self-injurious behavior | 6 412 727 | Yes | Cross-sectional | 8/10 |

| Kamio,62 2002 (Japan) | “Children and adolescents” | Pediatric | Nonclinical | Participants without ASD | Self-injurious behavior | 657 | No | Cross-sectional | 6/10 |

| Kats et al,63 2013 (United States) | 30-59 | Adult | Nonclinical, database | Participants with ID and without ASD | Self-injurious behavior | 4989 | No | Cross-sectional | 8/10 |

| Kirby et al,16 2019 (United States) | 14-70 | Adult | Nonclinical, registry | Participants without ASD | Suicide | 9 121 537 | No | Cohort | 7/9 |

| Kõlves et al,64 2021 (Denmark) | ≥10 | Pediatric and adult | Nonclinical, registry | Participants without ASD | Suicide attempt | 6 559 266 | Yes | Cohort | 8/9 |

| MaClean et al,65 2010 (United States) | 18-72 mo | Pediatric | Clinical | Participants without ASD | Self-injurious behavior | 196 | No | Cross-sectional | 6/10 |

| Moses,66 2018 (United States) | 13-18 | Pediatric | Nonclinical | Participants without ASD | Suicide attempt | 10 489 | No | Cross-sectional | 5/10 |

| Nicholls et al,67 2020 (United Kingdom) | 3-19 | Pediatric | Nonclinical | Participants in special education without ASD | Self-injurious behavior | 321 | No | Cross-sectional | 6/10 |

| Pelton et al,68 2020 (United Kingdom) | 18-90 | Adult | Nonclinical | Participants without ASD | Suicidal ideation | 689 | No | Cross-sectional | 7/10 |

| Richards et al,69 2012 (England) | 4-62 (mean age: 13) | Pediatric | Nonclinical | Participants with Down syndrome | Self-injurious behavior | 197 | No | Cross-sectional | 7/10 |

| Soke et al,70 2018 (United States) | 30-68 mo | Pediatric | Nonclinical | Participants with developmental delay | Self-injurious behavior | 1668 | Yes | Case-control | 8/9 |

| Takara and Kondo,71 2014 (Japan) | 18-87 | Adult | Clinical | Participants without ASD and with depression | Suicide attempt | 336 | No | Case-control | 7/9 |

| Tani et al,18 2012 (Japan) | 18-73 | Adult | Nonclinical | ASD vs patients with no mental disorders but with disturbance of social functions and communication skills | Self-injurious behavior | 162 | No | Cross-sectional | 6/10 |

| Vohra et al,72 2016 (United States) | 22-64 | Adult | Clinical | Participants without ASD | Self-injurious behavior and suicidality | 102 108 | No | Cross-sectional | 8/10 |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; ID, intellectual disability.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for quality assessment can award a maximum score of 10 for cross-sectional studies and a maximum score of 9 for case-control and cohort studies. A score range of 7 to 10 indicates high quality, 5 to 6 indicates moderate quality, and 0 to 4 indicates low quality in cross-sectional studies. A score range of 6 to 9 indicates high quality, 4 to 5 indicates moderate quality, and 0-4 indicates low quality in cohort and case control studies.

The study populations spanned the entire age spectrum from toddlers to older adults. Six studies (19%) combined pediatric and adult populations,16,47,49,60,64,69 of which 2 studies reported relevant analyses by age group.49,64 Of the remaining 4 studies, 2 studies were categorized as having a pediatric population, with a mean participant age of younger than 20 years at the time of enrollment,47,69 and 2 studies were categorized as having an adult population with a mean participant age of 20 years or older at the time of enrollment.16,60 The final subgroup analysis by age group included 16 studies (52%) in pediatric populations,9,17,46,47,53,54,55,56,59,61,62,65,66,67,69,70 13 studies (42%) in adult populations,16,18,48,50,51,52,57,58,60,63,68,71,72 and 2 studies (6%) in both pediatric and adult populations49,64 (Table 1).

The study quality was, overall, moderate to high, with higher numbers representing a lower degree of potential bias. Case-control studies were assigned a mean score of 8 of 9, cohort studies were assigned a mean score of 7.5 of 10, and cross-sectional studies were assigned a mean score of 6.8 of 10 (Table 1).

Of the 31 studies, 6 (19%) recruited participants in a clinical setting9,53,59,65,71,72 and 25 (81%) recruited participants in a nonclinical setting16,17,18,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,54,55,56,57,58,60,61,62,63,64,66,67,68,69,70 (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Most studies (n = 22 [71%]) used the general population without ASD as the control group.9,16,17,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,56,58,59,60,61,62,64,65,66,68,72 Nine studies (29%) used individuals with neurodevelopmental or neuropsychiatric conditions or special education eligibility without ASD as control participants.18,54,55,57,63,67,69,70,71 Fifteen studies (48%) investigated self-injurious behavior without suicidality,9,18,46,47,50,54,55,56,57,62,63,65,67,69,70 14 studies (45%) investigated suicidality (ie, suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or suicide),16,17,49,51,52,53,58,59,60,61,64,66,68,71 and 2 studies (6%) investigated both.48,72

Summary of Findings

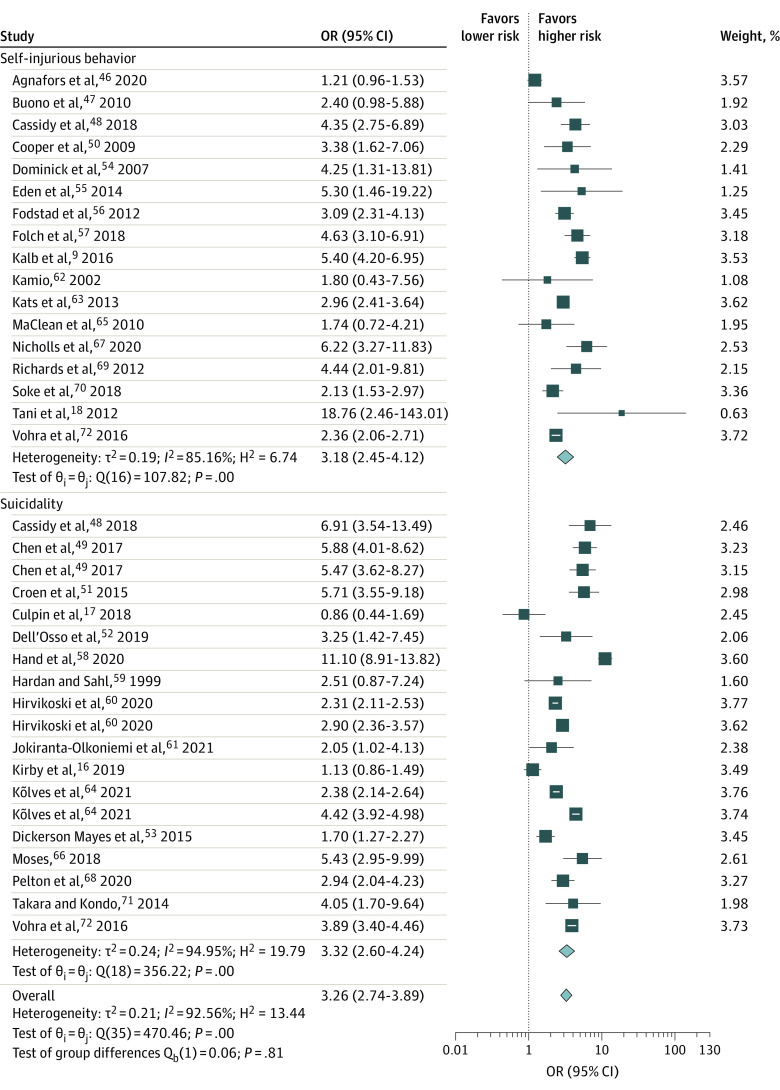

Of the 36 results retrieved from 31 studies, 29 revealed significant associations between ASD and self-harm, and 7 showed no significant association. In pooled data, people with ASD had 2.26-times higher odds of self-harm than those without ASD (pooled OR, 3.26; 95% CI, 2.74-3.89; I2 = 92.56%). Seventeen studies9,18,46,47,48,50,54,55,56,57,62,63,65,67,69,70,72 assessed the association between ASD and self-injurious behavior and reported ORs that ranged from 1.21 to 18.76. Sixteen studies16,17,48,49,51,52,53,58,59,60,61,64,66,68,71,72 assessed the association between ASD and suicidality and reported ORs that ranged from 0.86 to 11.10. Individuals with ASD were at similarly heightened risk of self-injurious behavior (pooled OR, 3.18; 95% CI, 2.45-4.12; I2 = 85.16%) and suicidality (pooled OR, 3.32; 95% CI, 2.60-4.24; I2 = 94.95%) (Table 2; Figure 2).

Table 2. Summary Estimates of ORs and 95% CIs of Self-harm Associated With Autism Spectrum Disorder by Study Characteristics.

| Study characteristic | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-injurious behavior | Suicidality | Self-harm (self-injurious behavior or suicidality) | |

| Overall | 3.18 (2.45-4.12) | 3.32 (2.60-4.24) | 3.26 (2.74-3.89) |

| Children | 2.99 (1.93-4.64) | 2.53 (1.70-3.76) | 2.74 (2.17-3.44) |

| Adults | 3.38 (2.54-4.50) | 3.84 (2.78-5.30) | 3.97 (3.11-5.01) |

| Setting | |||

| Clinical | NA | NA | 2.93 (2.07-4.16) |

| Nonclinical | NA | NA | 3.37 (2.73-4.16) |

| Asia | NA | NA | 5.38 (4.05-7.14) |

| Europe | NA | NA | 2.98 (2.40-3.72) |

| North America | NA | NA | 3.22 (2.32-4.47) |

Abbreviations: NA, not available; OR, odds ratio.

Figure 2. Forest Plot of the Association of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Risk of Self-injurious Behavior, Suicidality, and Overall Self-harm.

The length of the horizontal lines represents the 95% CIs. The size of the squares represents the weighted odds ratios (ORs), and the size of the diamonds represents summary ORs.

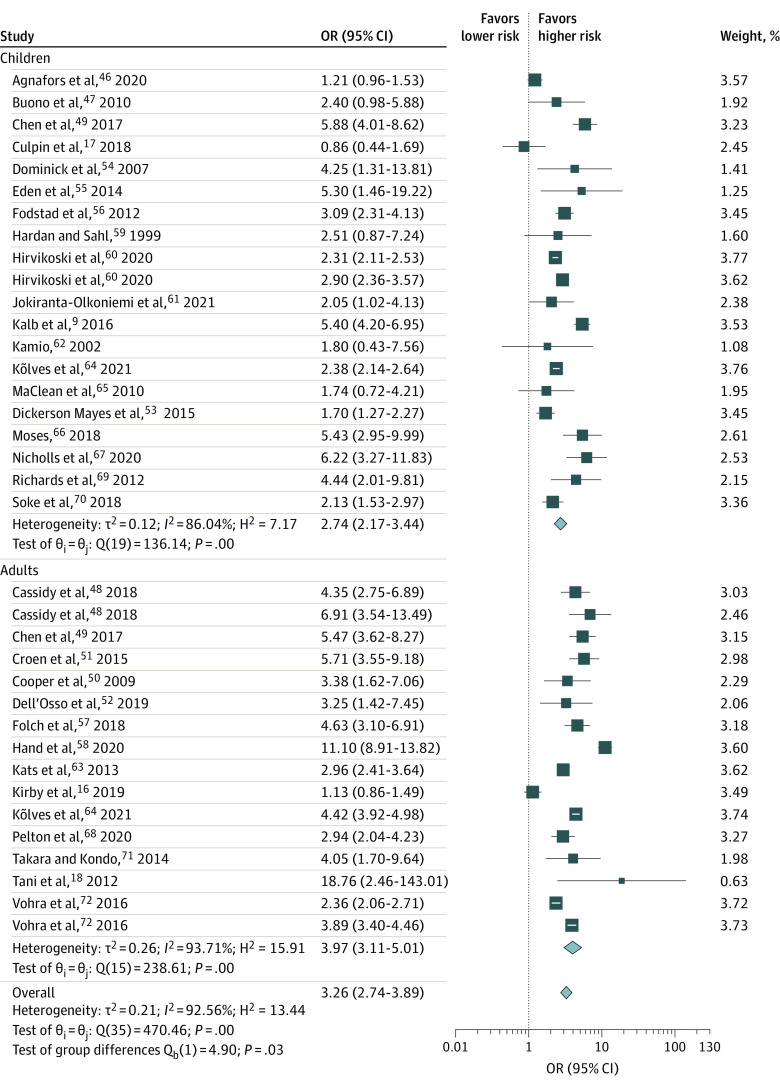

In meta-regression analyses, only age group significantly moderated the association between ASD and self-harm, where adults were at greater risk of self-harm than children (OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.04-2.03). The pooled ORs for both self-injurious behavior and suicidality were similarly high in adults (pooled self-harm OR, 3.97 [95% CI, 3.11-5.01; I2 = 93.71%]; self-injurious behavior OR, 3.38 [95% CI, 2.54-4.50; I2 = 74.12%]; and suicidality OR, 3.84 [95% CI, 2.78-5.30; I2 = 96.09%]) and in children (pooled self-harm OR, 2.74 [95% CI, 2.17-3.44; I2 = 86.04%]; self-injurious behavior OR, 2.99 [95% CI, 1.93-4.64; I2 = 88.66%]; and suicidality OR, 2.53 [95% CI, 1.70-3.76; I2 = 85.89%]) (Table 2; Figure 3). Results were consistent in the direction and magnitude of the association across continents (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). We were unable to consider sex and comorbid conditions as potential moderators because the studies did not provide enough information about these factors to allow appropriate analyses.

Figure 3. Forest Plot of the Association of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Risk of Self-injurious Behavior and Suicidality Among Children and Adults.

The length of the horizontal lines represents the 95% CIs. The size of the squares represents the weighted odds ratios (ORs), and the size of the diamonds represents summary ORs.

The trim-and-fill funnel plots did not indicate any major publication bias in any of the meta-analyses. Pooled ORs based on combined observed and imputed studies still showed significant associations between ASD and self-harm in the pediatric and adult populations (eFigures 3-5 in the Supplement). When 6 studies were imputed to the meta-analysis, the overall OR decreased from 3.26 (based on 36 observed results from 31 studies) to 2.82 (based on 42 observed and imputed results) (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). In addition, both the Egger test and Tang test showed nonsignificant publication bias.

Effect size estimates indicated a high level of heterogeneity across studies in all sets of meta-analyses, with the Cochrane Q statistic ranging from 19.32 (df = 5; P < .001) to 469.36 (df = 35; P < .001) for the pooled meta-analysis. The estimated mean Eth [Q] of the null distribution of Q was 21.15, and the corrected mean E[Q] was 21.42 with an estimated variance of 40.06. The parameters of the approximating γ distribution were α = 11.45 and β = 1.87, with a P < .001. The Breslow-Day statistic value was 231.65 (P < .001). Despite a high level of heterogeneity, the results showed consistent significant associations between ASD and self-harm, with all but 1 study indicating an increased odds of self-harm among people with ASD.

Discussion

In the US, the incidence of suicide attempts or suicidal ideation in children aged 5 to 19 years who are treated in emergency departments has doubled in the past decade,73 and recent studies suggest that people with ASD are at a particularly heightened risk of self-harm.24,74,75 The present meta-analysis found that ASD was associated with more than a 3-fold increase in odds of self-injurious behavior and suicidality. These findings were generally consistent across children and adults and across geographic regions. The substantially increased odds of self-harm associated with ASD was robust regardless of study designs and methods, settings, and populations. The 3 funnel plots visually demonstrated appropriate symmetry and scatter, indicating limited publication bias, and imputation of missing studies did not substantially change the estimated ORs. Because heightened odds of self-harm were observed in both children and adults, targeted interventions to identify and mitigate the risk are imperative.

The findings of this study are of public health importance given the continuing increase in ASD prevalence and the high prevalence of self-injurious behavior in individuals with ASD. A recent meta-analysis investigated self-injurious behavior among people with ASD and reported a pooled prevalence estimate of 42% (95% CI, 38%-47%), but it did not investigate the comparative risk or the risk of suicidality.23 We included 31 studies with samples that cover a wide range of ages and self-harm outcomes, creating substantial heterogeneity. Although the I2 statistic showed the proportion of the variance in observed outcomes that reflected variation in true effect sizes rather than a sampling error, it did not measure the absolute variance of true effect sizes.76 It is the proportion of total variation in the point estimates that is attributable to between-study heterogeneity.77 In contrast, the prediction interval shows the range of the absolute amount of dispersion in true effect sizes.76 In this study, the true effect size (ie, OR for association of ASD and self-harm) likely is between 1.26 and 8.47.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the estimates of the association between ASD and self-harm were not adjusted for comorbidities, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and intellectual disability. Although the role of comorbid conditions warrants further investigation, comorbidities are unlikely to fully explain the substantially increased odds of self-harm among people with ASD.64 Second, we found that substantial heterogeneity among the observational studies in this systematic review can be partly explained by the differences in study age groups, definitions, designs, analytic approaches, and comorbidities that were infrequently considered as covariates. Third, the outcomes of self-injurious behavior and suicidality varied broadly in their clinical presentations, patient and family burden, and interventions. This study synthesized the epidemiologic evidence for the 2 types of self-harm but did not offer estimates for each specific type of self-harm. Fourth, as in most studies that explore epidemiologic patterns in people with ASD, the linear positive cohort effects that demonstrate year-to-year increases in autism diagnoses are important to note.78 In this study, the cohort effects may introduce bias that is associated with misclassification of ASD diagnosis in older populations, possibly underestimating the risk of self-harm in adults with ASD. Most studies included in this meta-analysis involved children, although adults represent a larger proportion of the population with autism.79 This situation reflects a greater awareness and more appropriate diagnosis of ASD in the past few decades that has focused on pediatric practitioners and populations, accompanied with limited research on autism in adulthood. Fifth, we did not exclude studies on the basis of assessment of their risk of bias. Most included studies received Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores that were reflective of minimal risk of bias, but a few studies received lower scores (4-5 points).

Conclusions

This systematic review with meta-analysis found that ASD was associated with a substantially increased risk of self-injurious behaviors and suicidality. This finding was consistent in pediatric and adult populations across geographic regions and in study designs, methods, and settings. Further research is needed to examine the role of primary care screenings, preventive mental health services, and lethal means counseling in reducing self-harm among people with ASD.

eFigure 1. Forest Plot Showing the Association of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Self-Harm by Study Setting

eFigure 2. Forest Plot Showing the Association of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Self-Harm by Continent

eFigure 3. Funnel Plot for Self-Harm Associated With Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Among Children and Adults

eFigure 4. Funnel Plot for Self-Harm Associated With Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Among Adults

eFigure 5. Funnel Plot for Self-Harm Associated With Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Among Children

eMethods 1. Deviations from PROSPERO Protocol

eMethods 2. Search Strategies

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Autism spectrum disorder (ASD): diagnostic criteria. June 29, 2020. Accessed January 22, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/hcp-dsm.html

- 2.Dietz PM, Rose CE, McArthur D, Maenner M. National and state estimates of adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(12):4258-4266. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04494-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandell DS, Barry CL, Marcus SC, et al. Effects of autism spectrum disorder insurance mandates on the treated prevalence of autism spectrum disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(9):887-893. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kogan MD, Vladutiu CJ, Schieve LA, et al. The prevalence of parent-reported autism spectrum disorder among US children. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20174161. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Baio J, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020;69(4):1-12. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee LC, Harrington RA, Chang JJ, Connors SL. Increased risk of injury in children with developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2008;29(3):247-255. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDermott S, Zhou L, Mann J. Injury treatment among children with autism or pervasive developmental disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38(4):626-633. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0426-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain A, Spencer D, Yang W, et al. Injuries among children with autism spectrum disorder. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(4):390-397. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalb LG, Vasa RA, Ballard ED, Woods S, Goldstein M, Wilcox HC. Epidemiology of injury-related emergency department visits in the US among youth with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(8):2756-2763. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2820-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirvikoski T, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Boman M, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, Bölte S. Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(3):232-238. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickett J, Xiu E, Tuchman R, Dawson G, Lajonchere C. Mortality in individuals with autism, with and without epilepsy. J Child Neurol. 2011;26(8):932-939. doi: 10.1177/0883073811402203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guan K, Fox KR, Prinstein MJ. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a time-invariant predictor of adolescent suicide ideation and attempts in a diverse community sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):842-849. doi: 10.1037/a0029429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillberg C, Billstedt E, Sundh V, Gillberg IC. Mortality in autism: a prospective longitudinal community-based study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(3):352-357. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0883-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mouridsen SE, Brønnum-Hansen H, Rich B, Isager T. Mortality and causes of death in autism spectrum disorders: an update. Autism. 2008;12(4):403-414. doi: 10.1177/1362361308091653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duerden EG, Oatley HK, Mak-Fan KM, et al. Risk factors associated with self-injurious behaviors in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(11):2460-2470. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1497-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirby AV, Bakian AV, Zhang Y, Bilder DA, Keeshin BR, Coon H. A 20-year study of suicide death in a statewide autism population. Autism Res. 2019;12(4):658-666. doi: 10.1002/aur.2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Culpin I, Mars B, Pearson RM, et al. Autistic traits and suicidal thoughts, plans, and self-harm in late adolescence: population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(5):313-320.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tani M, Kanai C, Ota H, et al. Mental and behavioral symptoms of person’s with Asperger’s syndrome: relationships with social isolation and handicaps. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2012;6(2):907-912. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):1249-1257. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang KL, Wei HT, Hsu JW, et al. Risk of suicide attempts in adolescents and young adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212(4):234-238. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):300-310. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai MC, Kassee C, Besney R, et al. Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(10):819-829. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steenfeldt-Kristensen C, Jones CA, Richards C. The prevalence of self-injurious behaviour in autism: a meta-analytic study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(11):3857-3873. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04443-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moseley RL, Gregory NJ, Smith P, Allison C, Baron-Cohen S. Links between self-injury and suicidality in autism. Mol Autism. 2020;11(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13229-020-0319-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asarnow JR, Porta G, Spirito A, et al. Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: findings from the TORDIA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(8):772-781. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brent D. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a predictor of suicidal behavior in depressed adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):452-454. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nock MK, Joiner TE Jr, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. 2006;144(1):65-72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andover MS, Gibb BE. Non-suicidal self-injury, attempted suicide, and suicidal intent among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(1):101-105. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Victor SE, Klonsky ED. Correlates of suicide attempts among self-injurers: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(4):282-297. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamza CA, Willoughby T. Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: a latent class analysis among young adults. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkinson PO. Nonsuicidal self-injury: a clear marker for suicide risk. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(8):741-743. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamza CA, Stewart SL, Willoughby T. Examining the link between nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: a review of the literature and an integrated model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(6):482-495. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006-1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Accessed March 3, 2020. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 35.Huisman S, Mulder P, Kuijk J, et al. Self-injurious behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;84:483-491. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guertin T, Lloyd-Richardson E, Spirito A, Donaldson D, Boergers J. Self-mutilative behavior in adolescents who attempt suicide by overdose. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(9):1062-1069. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown MZ, Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Reasons for suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(1):198-202. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Linehan MM. Suicidal people: one population or two? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;487:16-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb27882.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yates TM. The developmental psychopathology of self-injurious behavior: compensatory regulation in posttraumatic adaptation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(1):35-74. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett S, Coggan C, Adams P. Problematising depression: young people, mental health and suicidal behaviours. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(2):289-299. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00347-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lipsey M, Wilson D.. Practical Meta-Analysis. Sage Publications, Inc; 2001. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://idostatistics.com/lipsey-wilson-2001-practical-meta-analysis-2001/ [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kulinskaya E, Dollinger MB. An accurate test for homogeneity of odds ratios based on Cochran’s Q-statistic. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:49. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0034-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin L. Graphical augmentations to sample-size-based funnel plot in meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10(3):376-388. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agnafors S, Torgerson J, Rusner M, Kjellström AN. Injuries in children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1273. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09283-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buono S, Scannella F, Palmigiano MB. Self-injurious behavior: a comparison between Prader-Willi syndrome, Down syndrome and autism. Life Span and Disabil. 2010;13(2):187-201. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cassidy S, Bradley L, Shaw R, Baron-Cohen S. Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults. Mol Autism. 2018;9:42. doi: 10.1186/s13229-018-0226-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen MH, Pan TL, Lan WH, et al. Risk of suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: a nationwide longitudinal follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(9):e1174-e1179. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper SA, Smiley E, Allan LM, et al. Adults with intellectual disabilities: prevalence, incidence and remission of self-injurious behaviour, and related factors. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2009;53(3):200-216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01060.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Croen LA, Zerbo O, Qian Y, et al. The health status of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism. 2015;19(7):814-823. doi: 10.1177/1362361315577517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dell’Osso L, Carpita B, Muti D, et al. Mood symptoms and suicidality across the autism spectrum. Compr Psychiatry. 2019;91:34-38. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dickerson Mayes S, Calhoun SL, Baweja R, Mahr F. Suicide ideation and attempts in children with psychiatric disorders and typical development. Crisis. 2015;36(1):55-60. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dominick KC, Davis NO, Lainhart J, Tager-Flusberg H, Folstein S. Atypical behaviors in children with autism and children with a history of language impairment. Res Dev Disabil. 2007;28(2):145-162. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2006.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eden KE, de Vries PJ, Moss J, Richards C, Oliver C. Self-injury and aggression in tuberous sclerosis complex: cross syndrome comparison and associated risk markers. J Neurodev Disord. 2014;6(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1866-1955-6-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fodstad JC, Rojahn J, Matson JL. The emergence of challenging behaviors in at-risk toddlers with and without autism spectrum disorder: a cross-sectional study. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2012;24(3):217-234. doi: 10.1007/s10882-011-9266-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Folch A, Cortés MJ, Salvador-Carulla L, et al. Risk factors and topographies for self-injurious behaviour in a sample of adults with intellectual developmental disorders. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2018;62(12):1018-1029. doi: 10.1111/jir.12487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hand BN, Angell AM, Harris L, Carpenter LA. Prevalence of physical and mental health conditions in Medicare-enrolled, autistic older adults. Autism. 2020;24(3):755-764. doi: 10.1177/1362361319890793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hardan A, Sahl R. Suicidal behavior in children and adolescents with developmental disorders. Res Dev Disabil. 1999;20(4):287-296. doi: 10.1016/S0891-4222(99)00010-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hirvikoski T, Boman M, Chen Q, et al. Individual risk and familial liability for suicide attempt and suicide in autism: a population-based study. Psychol Med. 2020;50(9):1463-1474. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719001405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jokiranta-Olkoniemi E, Gyllenberg D, Sucksdorff D, et al. Risk for premature mortality and intentional self-harm in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(9):3098-3108. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04768-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kamio Y. Self-injurious and aggressive behavior in adolescents with intellectual disabilities: a comparison of adolescents with and without autism. Jpn J Spec Educ. 2002;39(6):143-154. doi: 10.6033/tokkyou.39.143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kats D, Payne L, Parlier M, Piven J. Prevalence of selected clinical problems in older adults with autism and intellectual disability. J Neurodev Disord. 2013;5(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1866-1955-5-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kõlves K, Fitzgerald C, Nordentoft M, Wood SJ, Erlangsen A. Assessment of suicidal behaviors among individuals with autism spectrum disorder in Denmark. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2033565. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.MaClean WE Jr, Tervo RC, Hoch J, Tervo M, Symons FJ. Self-injury among a community cohort of young children at risk for intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Pediatr. 2010;157(6):979-983. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.05.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moses T. Suicide attempts among adolescents with self-reported disabilities. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2018;49(3):420-433. doi: 10.1007/s10578-017-0761-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nicholls G, Hastings RP, Grindle C. Prevalence and correlates of challenging behaviour in children and young people in a special school setting. Eur J Spec Needs Educ. 2020;35(1):40-54. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2019.1607659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pelton MK, Crawford H, Robertson AE, Rodgers J, Baron-Cohen S, Cassidy S. Understanding suicide risk in autistic adults: comparing the interpersonal theory of suicide in autistic and non-autistic samples. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(10):3620-3637. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04393-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Richards C, Oliver C, Nelson L, Moss J. Self-injurious behaviour in individuals with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2012;56(5):476-489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01537.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Soke GN, Rosenberg SA, Rosenberg CR, Vasa RA, Lee LC, DiGuiseppi C. Brief report: self-injurious behaviors in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder compared to other developmental delays and disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(7):2558-2566. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3490-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takara K, Kondo T. Comorbid atypical autistic traits as a potential risk factor for suicide attempts among adult depressed patients: a case-control study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s12991-014-0033-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vohra R, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U. Emergency department use among adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(4):1441-1454. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2692-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mishara BL, Stijelja S. Trends in US suicide deaths, 1999 to 2017, in the context of suicide prevention legislation. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(5):499-500. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Soke GN, Rosenberg SA, Hamman RF, et al. Factors associated with self-injurious behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder: findings from two large national samples. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(2):285-296. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2951-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cassidy S, Rodgers J. Understanding and prevention of suicide in autism. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(6):e11. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30162-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR.. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. doi: 10.1002/9780470743386 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coory MD. Comment on: heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(3):932. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Keyes KM, Susser E, Cheslack-Postava K, Fountain C, Liu K, Bearman PS. Cohort effects explain the increase in autism diagnosis among children born from 1992 to 2003 in California. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(2):495-503. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bresnahan M, Li G, Susser E. Hidden in plain sight. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(5):1172-1174. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Forest Plot Showing the Association of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Self-Harm by Study Setting

eFigure 2. Forest Plot Showing the Association of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Self-Harm by Continent

eFigure 3. Funnel Plot for Self-Harm Associated With Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Among Children and Adults

eFigure 4. Funnel Plot for Self-Harm Associated With Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Among Adults

eFigure 5. Funnel Plot for Self-Harm Associated With Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Among Children

eMethods 1. Deviations from PROSPERO Protocol

eMethods 2. Search Strategies