Abstract

Background

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are highly prevalent and associated with a substantial public health burden. Although evidence‐based interventions exist for treating SUDs, many individuals remain symptomatic despite treatment, and relapse is common.Mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) have been examined for the treatment of SUDs, but available evidence is mixed.

Objectives

To determine the effects of MBIs for SUDs in terms of substance use outcomes, craving and adverse events compared to standard care, further psychotherapeutic, psychosocial or pharmacological interventions, or instructions, waiting list and no treatment.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to April 2021: Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Specialised Register, CENTRAL, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, CINAHL and PsycINFO. We searched two trial registries and checked the reference lists of included studies for relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Selection criteria

RCTs testing a MBI versus no treatment or another treatment in individuals with SUDs. SUDs included alcohol and/or drug use disorders but excluded tobacco use disorders. MBIs were defined as interventions including training in mindfulness meditation with repeated meditation practice. Studies in which SUDs were formally diagnosed as well as those merely demonstrating elevated SUD risk were eligible.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

Forty RCTs met our inclusion criteria, with 35 RCTs involving 2825 participants eligible for meta‐analysis. All studies were at high risk of performance bias and most were at high risk of detection bias.

Mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) versus no treatment

Twenty‐four RCTs included a comparison between MBI and no treatment. The evidence was uncertain about the effects of MBIs relative to no treatment on all primary outcomes: continuous abstinence rate (post: risk ratio (RR) = 0.96, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.14, 1 RCT, 112 participants; follow‐up: RR = 1.04, 95% CI 0.54 to 2.01, 1 RCT, 112 participants); percentage of days with substance use (post‐treatment: standardized mean difference (SMD) = 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.37 to 0.47, 4 RCTs, 248 participants; follow‐up: SMD = 0.21, 95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.54, 3 RCTs, 167 participants); and consumed amount (post‐treatment: SMD = 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.31 to 0.52, 3 RCTs, 221 participants; follow‐up: SMD = 0.33, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.66, 2 RCTs, 142 participants). Evidence was uncertain for craving intensity and serious adverse events. Analysis of treatment acceptability indicated MBIs result in little to no increase in study attrition relative to no treatment (RR = 1.04, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.40, 21 RCTs, 1087 participants). Certainty of evidence for all other outcomes was very low due to imprecision, risk of bias, and/or inconsistency. Data were unavailable to evaluate adverse events.

Mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) versus other treatments (standard of care, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychoeducation, support group, physical exercise, medication)

Nineteen RCTs included a comparison between MBI and another treatment. The evidence was very uncertain about the effects of MBIs relative to other treatments on continuous abstinence rate at post‐treatment (RR = 0.80, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.44, 1 RCT, 286 participants) and follow‐up (RR = 0.57, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.16, 1 RCT, 286 participants), and on consumed amount at post‐treatment (SMD = ‐0.42, 95% CI ‐1.23 to 0.39, 1 RCT, 25 participants) due to imprecision and risk of bias. The evidence suggests that MBIs reduce percentage of days with substance use slightly relative to other treatments at post‐treatment (SMD = ‐0.21, 95% CI ‐0.45 to 0.03, 5 RCTs, 523 participants) and follow‐up (SMD = ‐0.39, 95% CI ‐0.96 to 0.17, 3 RCTs, 409 participants). The evidence was very uncertain about the effects of MBIs relative to other treatments on craving intensity due to imprecision and inconsistency. Analysis of treatment acceptability indicated MBIs result in little to no increase in attrition relative to other treatments (RR = 1.06, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.26, 14 RCTs, 1531 participants). Data were unavailable to evaluate adverse events.

Authors' conclusions

In comparison with no treatment, the evidence is uncertain regarding the impact of MBIs on SUD‐related outcomes. MBIs result in little to no higher attrition than no treatment. In comparison with other treatments, MBIs may slightly reduce days with substance use at post‐treatment and follow‐up (4 to 10 months). The evidence is uncertain regarding the impact of MBIs relative to other treatments on abstinence, consumed substance amount, or craving. MBIs result in little to no higher attrition than other treatments. Few studies reported adverse events.

Plain language summary

Mindfulness‐based interventions for substance use disorders

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to determine whether mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) i.e. interventions involving training in mindfulness meditation improve symptoms of substance use disorders (SUDs) (i.e. alcohol and/or drug use, but excluding tobacco use disorders). Cochrane researchers searched, selected and analyzed all relevant studies to answer this question. We found 40 randomized controlled trials,that assessed MBI as a treatment for SUDs.

Key messages

SUD outcomes were monitored at different time points: directly following completion of the MBIs, and at follow‐up time points, which ranged from 3 months to 10 months after the MBI ended. Relative to other interventions (standard of care, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), psychoeducation, support group, physical exercise, medication), MBIs may slightly reduce days with substance use, but it is very uncertain whether they reduce other SUD‐related outcomes. The effects of MBIs relative to no treatment was very uncertain across all SUD‐assessed outcomes, as was the risk for adverse events.

What was studied in this review?

SUDs are very common and associated with negative physical and psychological health outcomes. Although evidence‐based interventions exist for treating SUDs, the standard treatments may not be sufficient and many individuals relapse to substance use. In the past several decades, MBIs have been examined for the treatment of SUDs. MBIs involve training in mindfulness meditation practice, which emphasizes the cultivation of present‐moment, non‐judgmental awareness. MBIs may improve many of the psychological variables involved in substance use and relapse (i.e. depression, anxiety, stress, attention). We studied whether MBIs benefit individuals with SUDs.

We searched for studies that compared an MBI to no treatment or to another treatment (e.g. cognitive behavior therapy, psychoeducation). We studied the results at the end of the intervention and at follow‐up assessments, which occurred 3 to 10 months following the end of the intervention.

What are the main results of this review?

The review authors found 40 relevant studies, of which 45% were focused on individuals with various SUDs with the remaining studies including participants using a specific substance (e.g. alcohol, opioids). Of these 40 studies, 23 were conducted in the USA, 11 were conducted in Iran, two were conducted in Thailand, one was conducted in Brazil, one was conducted in China, one was conducted in Taiwan, and one was conducted in both Spain and the USA. We were able to analyze results of 35 studies composed of 2825 participants; the other five did not report usable results, and requests to the authors for more information were unsuccessful.

When MBIs were compared with other treatments, our review and analysis showed that MBIs may slightly reduce days with substance use at post‐treatment and follow‐up, and show similar study retention. The evidence is uncertain for other SUD‐related outcomes we assessed (continuous abstinence, consumed amount, craving intensity). When MBIs were compared with no treatment, the evidence was uncertain for all SUD‐related outcomes, although MBIs showed similar treatment retention. Adverse effects were only reported on in four studies. However, the available evidence did not suggest MBIs result in adverse events or serious adverse events.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies published up to April 2021.

Study funding sources

Sixteen studies reported no funding. The remaining studies reported one or more sources of funding and support. Nineteen acknowledged federal sources, seven acknowledged internal grants, four acknowledged non‐profit entities, and two acknowledged clinics.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings: mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) compared with no treatment for substance use disorders (SUDs).

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Continuous abstinence rate at post‐treatment RR < 1.00 favors MBI |

RR = 0.96 [0.44, 2.14] | 112 (1 RCT) | Very lowa, b, c | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to no treatment on continuous abstinence rate at post‐treatment. |

| Continuous abstinence rate at follow‐up (4 months) RR < 1.00 favors MBI |

RR = 1.04 [0.54, 2.01] | 112 (1 RCT) | Very lowa, b, c | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to no treatment on continuous abstinence rate at follow‐up. |

| Percentage days with substance use at post‐treatment Lower SMD favors MBI |

SMD = 0.05 [‐0.37, 0.47] | 248 (4 RCTs) | Very lowa, b, c | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to no treatment on percentage days with substance use at post‐treatment. |

| Percentage days with substance use at follow‐up (3 to 4 months) Lower SMD favours MBI |

SMD = 0.21 [‐0.12, 0.54] | 167 (3 RCTs) | Very lowb, c, d | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to no treatment on percentage days with substance use at follow‐up. |

| Consumed amount at post‐treatment Lower SMD favors MBI |

SMD = 0.10 [‐0.31, 0.52] | 221 (3 RCTs) | Very lowa, b, c | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to no treatment on consumed amount at post‐treatment. |

| Consumed amount at follow‐up (3 to 4 months) Lower SMD favors MBI |

SMD = 0.33 [0.00, 0.66] | 142 (2 RCTs) | Very lowb, c, d | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to no treatment on consumed amount at follow‐up. |

| Craving intensity at post‐treatment Lower SMD favors MBI |

Could not be pooled because of heterogeneity. Range = ‐4.84 to ‐0.32. | 128 (2 RCTs) | Very Lowa, b, c, e | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to no treatment on craving intensity at post‐treatment. |

| Treatment acceptability (attrition) RR < 1.00 favors MBI |

RR = 1.04 [0.77, 1.40] | 1087 (21 RCTs) | High | MBIs result in little to no increase in attrition relative to no treatment. |

| CI: confidence interval; MBI: mindfulness‐based interventions; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardized mean difference. | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||

a95% CI includes both an appreciable benefit and an appreciable harm. Downgraded one point downgraded for imprecision.

bSample size <400 (less then minimum optimal information size [OIS] recommended for continuous outcomes). Downgraded one point downgraded for imprecision.

cOutcome assessment was unblinded. Downgraded one point for risk of bias.

d95% CI includes both an effect not relevant to participants and an appreciable harm. Downgraded one point downgraded for imprecision.

eEffect sizes were highly heterogeneous (e.g., I2 ≥ 90%). Downgraded one point for inconsistency.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings: mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) compared with other treatments for substance use disorders (SUDs).

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Continuous abstinence rate at post‐treatment RR < 1.00 favors MBI |

RR = 0.80 [0.45, 1.44] | 286 (1 RCT) | Very Lowa, b, c | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to other treatments on continuous abstinence rate at post‐treatment. |

| Continuous abstinence rate at follow‐up (10 months) RR < 1.00 favors MBI |

RR = 0.57 [0.28, 1.16] | 286 (1 RCT) | Very Lowa, b, c | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to other treatments on continuous abstinence rate at follow‐up. |

| Percentage days with substance use at post‐treatment Lower SMD favors MBI |

SMD = ‐0.21 [‐0.45, 0.03] | 523 (5 RCTs) | Lowc, d | The evidence suggests that MBIs reduce percentage of days with substance use slightly relative to other treatments at post‐treatment. |

| Percentage days with substance use at follow‐up (4 to 10 months) Lower SMD favors MBI |

SMD = ‐0.39 [‐0.96, 0.17] | 409 (3 RCTs) | Lowc, d | The evidence suggests that MBIs reduce percentage of days with substance use slightly relative to other treatments at follow‐up. |

| Consumed amount at post‐treatment Lower SMD favors MBI |

SMD = ‐0.42 [‐1.23, 0.39] | 25 (1 RCT) | Very Lowa, b, c | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to other treatments on consumed amount at post‐treatment. |

| Craving intensity at post‐treatment Lower SMD favors MBI |

Could not be pooled because of heterogeneity. Range from SMD = ‐1.43 to 1.00 | 971 (9 RCTs) | Very lowc, d, e | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to other treatments on craving intensity at post‐treatment. |

| Craving intensity at follow‐up (3 to 6 months) Lower SMD favors MBI |

Could not be pooled because of heterogeneity. Range from SMD = ‐2.07 to ‐0.14 | 415 (4 RCTs) | Very lowc, d, e | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to other treatments on craving intensity at follow‐up. |

| Treatment acceptability (attrition) RR < 1.00 favors MBI |

RR = 1.06 [0.89, 1.26] | 1531 (14 RCTs) | High | MBIs result in little to no increase in attrition relative to other treatments. |

| CI: confidence interval; MBI: mindfulness‐based interventions; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardized mean difference. | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||

a95% CI includes both an appreciable benefit and an appreciable harm. Downgraded one point downgraded for imprecision.

bSample size < 400 (less then minimum optimal information size [OIS] recommended for continuous outcomes). Downgraded one point downgraded for imprecision.

cOutcome assessment was unblinded. Downgraded one point for risk of bias.

d95% CI includes both an effect not relevant to participants and an appreciable benefit.

eEffect sizes were highly heterogeneous (e.g., I2 ≥ 90%). Downgraded one point for inconsistency.

Background

Description of the condition

Substance use disorders (SUDs, see Table 3 for a list of all acronyms) are a disease category with a chronic and relapsing nature, characterized by dysfunctional patterns of tobacco, alcohol, prescription or illicit drug use, leading to specific psychophysical, affective and cognitive symptoms and consequences for psychosocial well‐being and health. While the major classification systems Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (APA 2000) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (WHO 2010) have subdivided SUDs into dependence and a secondary category, called "abuse" in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV) and "harmful use" in International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10) (Hasin 2006), the latest version of the DSM system, the DSM‐V (APA 2013) integrates both categories into a single substance use disorder concept that ranges along a continuum from mild to severe (Hasin 2013; Rehm 2013).

1. Acronyms used.

| Acronym | Term |

| SUD | substance use disorder |

| MBI | mindfulness‐based intervention |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| SMD | standardized mean difference |

| CI | confidence interval |

| USA | United States of America |

| MBSR | Mindfulness‐Based Stres Reduction |

| MBCT | Mindfulness‐Based Cognitive Therapy |

| MORE | Mindfulness‐Oriented Recovery Enhancement |

| DBT | Dialectical Behavior Therapy |

| ACT | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy |

| MBRP | Mindfulness‐Based Relapse Prevention |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SE | standard error |

| AE | adverse effects |

| SAE | serious adverse effects |

SUDs are highly prevalent and have a profound public health and economic impact (Degenhardt 2018; Vega 2002). It is estimated that about 4.2% of the global burden of disease as measured in disability adjusted life years (DALYs) is attributable to alcohol and 1.3% to illicit drugs (Degenhardt 2018). Together with mental disorders, SUDs constitute the fifth leading cause of death and disability worldwide (Whiteford 2013). Statistics vary between regions, with higher prevalence of some psychoactive substance use in more highly‐developed, compared to less‐developed, countries (Degenhardt 2018; WHO 2002a). Nevertheless, with the improved industrialization and centralization of alcohol production, alcohol consumption is increasingly becoming a problem in many developing regions (WHO 2002b). Regional shifts also seem to have reshaped the patterns of illicit drug use in the world (Uchtenhagen 2004; UNODC 2013). While some improvements for heroin use are registered in Western Europe, there is a rapid growth of the heroin market in the Afghanistan region and, further, in Central Asia, the Russian Federation and Eastern Europe. With the USA remaining the world's largest market for cocaine, there has been an increase in cocaine trafficking towards Western Europe (UNODC 2013).

The contribution of SUDs to the worldwide burden of disease and the costs to individuals, families and to society associated with substance use are rising (Whiteford 2013). As a large part of the substance‐attributable burden is assumed to be potentially avoidable through the implementation of preventive and therapeutic strategies (Rehm 2009), further effective strategies need to be developed that help individuals with SUDs to discontinue or reduce substance use in a way that increases health and well‐being.

Description of the intervention

Mindfulness is the English translation of Sati in Pali, an ancient language from northern India (Pali Text Society 1992). Rooted in 2500‐year‐old Buddhist philosophy and practice, mindfulness meditation practices such as Vipassana and Zen meditation are mind‐body practices promoting mindfulness as a state of consciousness attending to one’s moment‐to‐moment experience (Brown 2003); and “paying attention in a particular way, on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” (Kabat‐Zinn 1994). Practices like “focused attention meditation”, entailing voluntary and sustained attention on a selected object and “open monitoring meditation”, involving a meta‐cognitive monitoring of automatic cognitive and emotional processes contribute to a mindfulness content of experience with acceptance, patience, and compassion (Lutz 2008; Travis 2010; Vago 2012). By purposefully and nonjudgementally paying attention to the present moment, mindfulness meditation is often distinguished from concentrative meditation, which entails voluntary and sustained attention on a chosen object (Goleman 1988). Nevertheless, current neuroscientific evidence indicates that different types of attentional processes are activated in both meditation types (Lutz 2008). Furthermore, emphasis has been given to further classification criteria such as the role of self‐referential processes in different meditation types (Chiesa 2011).

There are various contemporary definitions of mindfulness in the psychological literature. Bishop 2004 has proposed a two‐component definition, with the first component focusing on self‐regulation of attention towards the immediate present moment and the second as an orientation marked by curiosity, openness and acceptance as fundamental features of mindfulness. Brown 2003 suggests a one‐dimensional definition of mindfulness, focusing on the “receptive attention to and awareness of the present moment”, while Shapiro 2006 developed a three‐component model by adding a motivational factor to Bishop’s components (for an overview see Chiesa 2011). Even though, to date, no consensus has been reached on how to define mindfulness, the two‐factor conceptualization (Bishop 2004) is often applied as an operational definition in research.

Mindfulness meditation was adapted for use in Western cultures in a variety of ways and has been incorporated into psychological treatment, constituting the “third wave” of behavior therapy (Hayes 2004). Combining mindfulness practice with components from mostly behavior and cognitive therapy, mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) have been explored to treat a variety of physical and psychological problems and disorders. Mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR), developed by Jon Kabat‐Zinn in 1979 (Kabat‐Zinn 1985; Kabat‐Zinn 1990; Kabat‐Zinn 1992; Kabat‐Zinn 1994; Kabat‐Zinn 2003), integrates mindfulness meditation techniques into a structured clinical program designed to help facilitate adaptation to the stressors of medical illness and assist people in managing pain and stress (Whitebird 2009). By combining Kabat‐Zinn's MBSR with elements of cognitive therapy for depression (Beck 1979), Segal, Williams, and Teasdale developed mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy (MBCT), a program that particularly targets “modes of mind” characteristic for mood disorders (Teasdale 2002). Mindfulness‐oriented recovery enhancement (MORE) ‐ a program integrating mindfulness with reappraisal and savoring skills ‐ has been developed to enhance recovery in people struggling with addiction and the underlying conditions (Garland 2012b). Mindfulness‐based relapse prevention (MBPR) is another MBI designed to target addiction. It integrates mindfulness practices with relapse‐prevention strategies (Witkiewitz 2014b). Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) are both innovative behavioral treatments that incorporate mindfulness practices and acceptance‐based interventions into their treatment programs (Chapman 2006). Major influences on DBT derive from behavioral science, dialectical philosophy and Zen practice, while a non‐judgemental observation and experience of thoughts constitutes one of the main elements of ACT. However, ACT and DBT do not emphasize formal training in mindfulness meditation. Following Crane 2017, we considered MBIs to be those that involved "sustained intensive training in mindfulness meditation practice" (p. 993).

Critical issues have been raised about mixing Buddhist elements with current psychological theories in modern MBIs and the resulting consequences for practitioners` aims and attitudes and the underlying psychological mechanism (Chiesa 2011). Some authors considered that influences of ancient Buddhist philosophy are only marginally acknowledged in modern MBIs and even identified misunderstandings of the concept of mindfulness in some modern ways of practicing mindfulness (Rapgay 2009; Chiesa 2011). In turn, it has been called into question whether mindfulness by itself can influence psychopathology without matching the type of mindfulness to a specific form of psycyhopathology (Teasdale 2003).

How the intervention might work

Teaching an attitude of non‐judgement and acceptance with an emphasis on substance use and craving, MBIs are increasingly recognized for their ability to enhance recovery from substance use disorders (Khanna 2013). The idea of experiencing urges without fighting against them has given rise to the term “urge surfing” (Marlatt 1985), in which cravings are conceptualized like waves in the ocean and individuals are encouraged to “surf on”, allowing it to pass instead of being wiped out by giving in to it (Murphy 2014). Through both cognitive behaviorally‐based exercises and mindfulness practices, MBPR practices share the common intention of bringing greater awareness to one’s experiences, with specific emphasis on the sequence of reactions that follow substance‐related cues (Witkiewitz 2014b). For explaining how MBIs may affect substance use, several plausible mechanisms of action emerge from both the addiction as well as the mindfulness perspective. By fostering an increasing ability to “stay in touch” with experiences rather than attempting to escape or distance oneself from unpleasant feelings and sensations, mindfulness practices might help individuals with substance use problems to increase the awareness of habit‐linked, minimally conscious and affective states linked to craving and relapse (Chiesa 2014). By strengthening the ability to “step back” from overwhelming emotions and sensations, while slowing down the chain of automatic processes of substance seeking, mindfulness practices increase the chance to interrupt the cycle of cognitive, affective, and psychophysiological mechanisms underlying craving, relapse and excessive drinking (Witkiewitz 2014b).

Referring to neuropsychological models of craving and self‐control, mindfulness practices have also been put into a neurocognitive perspective (Garland 2014c; Hölzel 2011; Witkiewitz 2014b). Neurocognitive models of self‐regulation hypothesize that the resolving of motivational conflicts to the benefit of intentions requires efficient top‐down control from the prefrontal cortex over subcortical regions, while self‐regulatory failure occurs whenever the balance is tipped in favor of subcortical areas, either due to prefrontal function impairments or particularly strong impulses (Heatherton 2011). Considering that substance‐related cues have acquired exaggerated salience in the course of substance use disorders – a process mainly attributable to neuroadaptive sensitization in the mesolimbic reward system (Robinson 2008) ‐ individuals with SUDs are faced with high demands on top‐down inhibitory control. As a strategy to control strong upwelling motivational drives, individuals with the intention to cut down their drinking often try to inhibit craving through the suppression of substance‐related thoughts (Bowen 2007; Garland 2012b). Thought suppression, in turn, has been shown to have the inverse effect, resulting in an increase, rather than decrease, of unwanted thoughts (Wegner 1994), causing a “behavioral rebound” with greater enactment of consummatory behaviors (Erskine 2010; Garland 2012a). Instead of trying to control strong upwelling motivational drives and to inhibit craving through the suppression of substance‐related thoughts, MBIs prevent swinging “the pendulum of prefrontal regulation from a context of under‐control to one of over‐control” (Garland 2014c), which might “snowball” minor lapses in self‐control into self‐regulatory collapse (Erskine 2010; Garland 2012a; Heatherton 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

MBIs currently receive a lot of attention worldwide and are increasingly suggested as therapeutic approaches for substance use and misuse (Chiesa 2014). In fact, from a theoretic perspective, MBIs appear to bring about meaningful advantages compared to first and second wave therapies. Even though MBIs show promise in the treatment of substance use disorders, findings are rather inconsistent (Murphy 2014). While several studies found positive treatment effects of mindfulness interventions, including reduced quantity and frequency of substance use, a number of studies did not report positive findings. This Cochrane Review on MBIs for SUDs aims to provide a systematic integration of the available evidence to health‐decision makers, therapists and patients; and to offer illustrative measures for estimating the relative benefits of MBIs compared to alternative types of psychotherapy, while indicating gaps of knowledge and methodological demands for future clinical research.

Objectives

To determine the effects of mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) for substance use disorder (SUD) (including alcohol and/or drug use disorders but excluding tobacco use disorders) in terms of substance use outcomes, craving and adverse events compared to standard care, further psychotherapeutic, psychosocial, or pharmacological interventions or instructions, waiting lists, and no treatment.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing MBIs for SUDs with other treatments or no intervention were eligible for inclusion in the review. Trials employing a cross‐over design were also eligible, using data from the first active treatment stage only to encounter the risk of carry‐over effects.

Types of participants

RCTs with patients suffering from SUDs including individuals with alcohol, prescription‐, illicit‐ and poly‐substance use disorders were considered as eligible for the review. There was no limitations on age or other participant characteristics. Besides accepted SUD diagnostic criteria including DSM‐III (APA 1980), DSM‐ III‐R (APA 1987), DSM‐IV‐TR (APA 2000), DSM‐V (APA 2013) and ICD‐10 (WHO 1992; WHO 2010), we also included studies in which SUD was not formally diagnosed, acknowledging that diagnostic systems are not consequently used in primary research.

Types of interventions

In accordance with the definition by Bishop and colleagues (Bishop 2004) of mindfulness, we consider as mindfulness‐based all approaches which promote a) an individual's attention towards the immediate present moment experience and b) an open and accepting orientation irrespective of the applied technique. In order to isolate the effects of mindfulness meditation practice specifically, we excluded interventions that involve solely the concept of mindfulness and do not include formal instruction in mindfulness meditation practice e.g. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT). This definition of MBIs is in keeping with that proposed by Crane 2017 and widely implemented in the meta‐analytic literature (see Goldberg 2021).

Accordingly, the following experimental interventions were included in the review:

ancient Buddhist meditations such as Vipassana meditation and Zen meditation;

other mindfulness meditation;

modern standardized group‐based meditation practices including mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR), mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness‐based relapse prevention (MBRP) and mindfulness training.

Any type of manually‐based and face‐to‐face treatment delivery including individual therapy and group session format were considered. Media‐ and CD‐supported interventions were accepted as complementary formats of treatment support (e.g. home‐practice formats), but not as exclusive modes of treatment delivery.

All comparators were eligible, with the exception of comparisons with other MBIs or similar mind‐body approaches. Comparisons could include standard care, further psychotherapeutic, psychosocial or pharmacological interventions or instructions, waiting list or no treatment. Comparisons were categorized into no treatment (which included standard care when both the mindfulness and non‐mindfulness arms received this) and other treatment (which included standard care when only the comparison condition received this).

Types of outcome measures

The study endpoints of the primary outcomes were considered essential to determine the effectiveness of MBIs, while secondary outcomes have only complementary value in the interpretation of results. If a study met the inclusion criteria, but did not provide necessary information for estimating effect sizes, while such data were also not available from the authors, the study was excluded from the meta‐analysis, but included in the qualitative analyses.

Primary and secondary outcomes were selected with regard to clinical relevance and conceptual considerations. With the "rate of continuous abstinence", the "per cent days with substance use" limited to non‐abstinent individuals and "consumed amount" limited to days with substance use, primary efficacy outcomes of the review assess conceptually‐distinct achievements in substance use control (Keller 1972); including an individual's ability to a) achieve and maintain continuous abstinence; and b) their ability to refrain from substance use on individual days; and c) to stop substance use once started. Evaluation of adverse effects, serious adverse effects, and treatment acceptability was included to allow evaluation of the safety and acceptability of MBIs relative to controls.

Primary outcomes

Continuous abstinence rate

Percentage of days with substance use

Consumed amount

Adverse event rate

Rate of continuous abstinence is a binary variable comprising the information whether a participant remained fully abstinent until the end of treatment or returned to substance use after detoxification. Accordingly, any substance use irrespective of the consumed amount or frequency of use was considered as treatment failure in the determination of the outcome. Percentage of days with substance use is a continuous measure calculated as the ratio of the total sum of substance use days related to possible exposure days during the treatment phase multiplied by the factor 100. If 'exposure days', representing days at which participants had a chance to use the substance (e.g. not incarcerated or hospitalized), are not available, substance use days were related to the study duration. Consumed amount is also a continuous measure and calculated by dividing the total consumed amount to the number of possible exposure days (or alternatively the entire study duration). Both outcomes, percentage of days with substance use and consumed amount, are measures representing substance use in the entire sample including all participants irrespective of their status of abstinence. Besides efficacy outcomes, harms were assessed with adverse events (AEs), which are binary variables comprising the information if an unfavorable event or symptom occurred during the course of the study or not.

To allow conclusions on the sustainability of treatment effects, post‐treatment efficacy outcomes (follow‐up after treatment termination) were evaluated. Indicators of substance use were considered irrespective of measurement including self‐reports, self‐report questionnaires, documentation templates (substance use diary, monitoring sheets), standardized interviews, observer‐reported measures, laboratory testing and breathalyzer tests. The validation of patient‐reported substance use by objective measures was entered in the risk of bias tables (susceptibility to bias).

Secondary outcomes

Craving intensity

Treatment acceptability (i.e. attrition)

Serious adverse events

Craving intensity occurring in natural settings and in laboratory paradigm was considered as assessed with a standardized tool (visual analog scale (VAS), questionnaire) or by an objective parameter of cue‐reactivity. Treatment acceptability was considered by either a) the number of participants dropping out from treatment for any reason; or b) subjective ratings of acceptance or satisfaction with care; or c) both measures. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were considered to be binary variables comprising the information if a serious unfavorable event such as, for example, suicide, suicide attempts or relapse requiring hospitalization.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials without language, publication year or publication status restrictions:

Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group's Specialised Register of Trials (searched on 26 April 2021);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, Issue 3);

PubMed (January 1966 to 26 April 2021);

Embase (OVID) (January 1974 to 26 April 2021);

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (EbscoHOST) (1982 to 26 April 2021);

Web of Knowledge, Web of Science (1990 to 26 April 2021);

PsycINFO (OVID) (1806 to 26 April 2021).

The Information Specialist modeled subject strategies for databases on the search strategy designed for PubMed. Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by the Cochrane Collaboration for identifying randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Chapter 6, Lefebvre 2011). Search strategies for major databases are provided in Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6.

We searched the following trials registries on 26 April 2021:

the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com);

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov).

Searching other resources

Key informants, primary authors and review authors were contacted with the request to indicate further studies of potential relevance. For this purpose, reference lists with identified studies and criteria of inclusion and exclusion of the review were provided. Finally, handsearching of reference lists of included studies and current reviews was conducted to complete the searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed the eligibility and relevance of trials on the basis of their abstracts retrieved from the electronic searches. For studies that met the inclusion criteria according to the abstract information, we obtained full‐text versions for closer inspection. Full‐text versions were also obtained if review authors differed in their judgement. Again, the relevance and eligibility of studies on the basis of full‐text versions was independently assessed by two review authors. In case of disagreements, the eligibility will be discussed with an additional consultant. The process of study identification and its results are outlined as flow diagrams according to the PRISMA statement (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

The review authors had full access to details about authors, institutions, and journals at all times. Information related to the study design and setting, the study participants, the interventions and comparators as well as the outcomes and methods for their assessment was abstracted from the original reports and entered into the study tables. The following information was extracted in detail:.

Study design and setting: design, principle of analysis, setting, study sites, country

Study sample: sample size, diagnosis, specific characteristics, age, gender

Interventions: description of the type of experimental and control intervention, treatment duration, treatment adherence

Outcomes: outcomes, methods of measurement, time points for assessment, compliance

Two review authors independently extracted all relevant outcome data onto pre‐specified data extraction forms and compared data value by value. In case of disagreements, the following sequential procedures were undertaken in descending order.

Comparison of published and extracted information to identify transcription and comprehension errors

Explanation of the coding decisions by each review author, followed by consensus discussion and arbitration

Any disagreement was discussed with an additional expert, and, when necessary, the authors of the studies were contacted for further information. Finally, after comparisons and corrections are concluded, we entered data into the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias assessment for RCTs and CCTs in this review was performed using the criteria recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The recommended approach for assessing risk of bias in studies included in Cochrane Reviews is a two‐part tool, addressing seven specific domains, namely sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and providers (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias), and other sources of bias. The first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement relating to the risk of bias for that entry, in terms of low, high or unclear risk. To make these judgements we used the criteria indicated by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions adapted to the addiction field. The criteria considered as constitutive for the rating of bias risks are outlined in Appendix 7.

The domains of sequence generation and allocation concealment (avoidance of selection bias) were addressed in the tool by a single entry for each study. We planned to consider blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessor (avoidance of performance bias and detection bias) separately for objective outcomes (e.g. dropout, substance use measured by urine‐analysis, participants who relapsed at the end of follow‐up,participants engaged in further treatments), and subjective outcomes (e.g. duration and severity of signs and symptoms of withdrawal, patient self‐reported use of substance, side effects, social functioning as integration at school or at work, family relationship). Incomplete outcome data (avoidance of attrition bias) were considered for all outcomes except for the dropout from the treatment, which is very often the primary outcome measure in trials on addiction. We considered the equivalence of baseline characteristics an additional indication of selection bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We measured treatment effects for dichotomous effectiveness outcomes (abstinence rate, retention rate) with a risk ratio (RR). For continuous outcomes (days with substance use, consumed amount per day, craving intensity), we planned to asses treatment effects using the mean differences (MD) for outcomes measured on the same scale.We used the standardized mean difference (SMD) for outcomes measured on different scales. We calculated all treatment effects within 95% confidence intervals (CIs). When effects on binary outcomes reached statistical significance, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB). A P value of 0.05 and below was chosen to indicate statistical significance of effects.

Unit of analysis issues

Only individually‐randomized trials with the individual participants constituting the unit of analysis were included in the review. To control unit of analysis errors in studies with multiple treatment groups of the same type (e.g. multiple alternative treatment comparisons; Bowen 2014), we combined interventions to create single‐pair comparisons.

Dealing with missing data

Outcome statistics were included as intent‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses. Sample sizes for continuous outcomes which were not explicitly provided in the trial publication were imputed by the size of treatment‐received samples or ‐ if not available ‐ by the size of the randomized sample. An exception was if samples were from analyses explicitly specified as completer analyses, which exclusively reported on patients who completed the trial. For differences in means, missing serious adverse events (SEs) were obtained from standard deviations (SDs), CIs or t values and P values. If only the medians were provided in the trial publications, the outcome statistics were not be included in the meta‐analyses, but we considered the information on the significance of effects in the qualitative discussion of results.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We quantified inconsistency across studies with the I² statistic (Higgins 2003), using threshold values for substantial heterogeneity as outlined by Deeks 2001. The Tau² statistic was additionally considered to provide an estimate of between‐study variance (Rücker 2008) independent of the sample size. A value of P < .10 was considered as significant statistical heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

When there were more than 10 included studies, we graphically illustrated the risk of publication bias with the funnel plot method (Light 1984; Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

For synthesizing outcome measures, we used a random‐effects model (DerSimonian 1986), with study effects being weighted using the Mantel‐Haenszel approach (Mantel 1959). For outcomes with low effect heterogeneity (I² < 30%), we applied a fixed‐effect model within the scope of sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Inconsistency across studies was quantified as described above (see Assessment of heterogeneity).

Sensitivity analysis

When the number of included studies was sufficient (> 10), we conducted sensitivity analyses to determine the influence of the following variables on the primary outcomes:

the underlying statistical model, by comparing effect sizes for low heterogeneity outcomes (I² < 30%) based on random‐effects models versus fixed‐effect models;

the method of measurement, by comparing effect sizes measured by breathalyzer or laboratory tests versus self‐reported data on alcohol use.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Findings were presented as summarized narrative and by summary of findings tables (GRADE); and the certainty of evidence was assessed with the GRADE approach for each outcome individually.

We created two summary of findings tables using the following outcomes: continuous abstinence, percentage days with substance use, consumed amount, craving intensity, treatment acceptability (attrition). We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence as it relates to the studies which contribute data to the meta‐analyses for the prespecified outcomes (Atkins 2004). We used methods and recommendations described in Chapter 14 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019) using GRADEproGDT software (GRADEpro GDT 2015). We justified all decisions to down‐grade or up‐grade the certainty of studies using footnotes, and we made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review where necessary.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grades of evidence.

High: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Results

Description of studies

The literature search and included studies are described below.

Results of the search

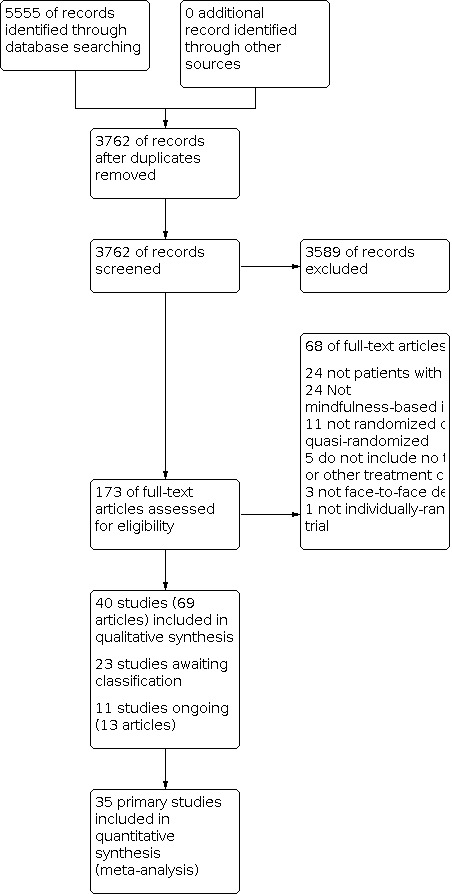

The searches of the seven databases (see Electronic searches) retrieved 5555 records. Our searches of other resources (Grant 2017, Li 2017, Goldberg 2018) identified no additional studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. Our screening of the reference lists of the included publications did not reveal additional randomized controlled trials (RCTs). We therefore had a total of 5555 records.

Once duplicates had been removed, we had a total of 3762 records. We excluded 3598 records based on titles and abstracts. We obtained the full text of 173 records. Of these, 68 records were not eligible to be included (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). We identified 23 studies awaiting classification and 11 ongoing studies reported in 13 references.

We included 40 studies reported in 69 references (as some studies were reported across multiple references). For a further description of our screening process, see the study flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Forty trials published in 69 publications met our inclusion criteria. Data eligible for meta‐analysis were available from 35 studies (2825) participants (Abed 2019; Alegria 2019; Alizadehgoradel 2019; Alterman 2004; Asl 2014a; Asl 2014b; Bein 2015; Bevan 2012; Black 2019; Bowen 2009; Bowen 2014; Brewer 2009; Brown 2017; Davis 2013; Davis 2018; de Dios 2012; Foroushani 2019; Garland 2010; Garland 2016; Garland 2019; Glasner 2017; Jenaabadi 2017; Imani 2015; Lee 2011; Machado 2020; Marfurt 2007; Margolin 2006; Mermelstein 2015; Shorey 2017; Vowles 2020; Witkiewitz 2014; Wongtongkam 2019; Yaghubi 2017; Zemestani 2016; Zgierska 2017). However, 18 trials only reported data usable for assessing acceptability (i.e. attrition) and did not provide eligible data for assessment of other primary or secondary outcomes. Five trials did not report any outcomes eligible for meta‐analysis (Esmaeili 2017; Himelstein 2015; Ramezani 2019; Wongtongkam 2018; Zhang 2019).

All studies used a randomized controlled trial design. Sixteen studies used an intention‐to‐treat analysis. Principle of analysis was unclear for three studies. In 17 studies, interventions and/or recruitment occurred in a residential treatment setting, while 19 studies did not involve a residential treatment setting. Setting was unclear in four studies. Of the 40 eligible studies, 23 were conducted in the USA, 11 were conducted in Iran, two were conducted in Thailand, one was conducted in China, one was conducted in Taiwan, one was conducted in Brazil, and one was conducted in Spain and the USA. Sample sizes ranged from eight (Bein 2015) to 341 (Alegria 2019), with an average of 76.08 (SD = 71.38).

Details of all 40 studies are available under Characteristics of included studies.

Participants

Eighteen studies included individuals with various substance use disorders (SUDs), 12 were focused on opioids, five on alcohol, three on stimulants, one on marijuana, and one on alcohol and/or cocaine use. Eighteen studies involved a formal diagnosis while 22 did not. Participants were on average 35.38 years old (SD = 8.27, range = 16.45 to 50.50). Samples were on average 31% female (SD = 34%, range = 0% to 100%). Samples were on average 34% non‐Hispanic White (SD = 36%, range = 0% to 100%).

Interventions

Studies implemented a variety of mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs). Sixteen studies involved mindfulness‐based relapse prevention (MBPR), or an adaptation of this intervention (e.g. mindfulness‐based relapse prevention for alcohol dependence; Zgierska 2017). Four studies involved mindfulness‐oriented recovery enhancement (MORE) or an adaptation of this intervention (e.g., mindfulness‐oriented recovery enhancement for child welfare; Brown 2017). Two studies involved mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy (MBCT), and one study involved mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR). The remaining studies involved other interventions that included mindfulness meditation training.

Three studies included multiple comparison conditions, with two including a second other treatment control conditions (Bowen 2014; Garland 2016) and one including a no treatment control (Jenaabadi 2017). Comparisons were made between MBIs and 19 other treatment conditions and 24 no treatment control conditions. Among the other treatment conditions, seven were standard of care (i.e. treatment as usual), six6 were based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), three were psychoeducation, one was a support group, one was physical exercise, and one was medication. Treatment as usual (TAU) was considered another treatment condition when the control group received treatment that was not also provided to the experimental group (e.g. control group received support group sessions while the experimental group received MBI).

MBIs lasted between one and 12 weeks, with an average duration of 7.17 weeks (SD = 2.49). Other treatment controls lasted between one and 19 weeks, with an average duration of 7.14 weeks (SD = 3.35). The majority (n = 32) of the MBIs used a group delivery format with five using an individual delivery format, and one using a combination of individual or individual and group (Margolin 2006). Delivery format was unclear in two studies. Thirteen of the other treatment control conditions used a group delivery format with two using an individual delivery format. Delivery format was unclear for four other treatment control conditions. Adherence to the MBI was reported in eight studies. All eight studies used a version of outside practice (e.g. minutes of practice, number of practice sessions). Fourteen studies included a mechanism to support provider adherence to the MBI protocol (e.g. recording of sessions, clinical supervision, fidelity checklist). Three studies included a mechanism to support provider adherence to the other treatment control condition protocols (e.g. recording of sessions, clinical supervision).

Outcomes

Primary outcome measures

Two studies reported eligible data for assessing continuous abstinence rate. The specific outcomes assessed included any drug use (Bowen 2014) and any heavy drinking (Zgierska 2017). Nine studies reported eligible data for assessing percentage days with substance use. The specific outcomes assessed included alcohol and other drug use days (Bowen 2009), drug use days (Bowen 2014; Witkiewitz 2014), percentage of days with alcohol use (Brewer 2009), Substance Frequency Scale (Davis 2018), marijuana use days (de Dios 2012), drinking episodes (Mermelstein 2015), and percentage heavy drinking days (Machado 2020; Zgierska 2017). Four studies reported eligible data for assessing consumed amount. The specific outcomes assessed included drinks per week (Davis 2013; Mermelstein 2015), drinks per day (Zgierska 2017), and alcohol consumption (Machado 2020). Four studies reported occurrence of adverse events (Bowen 2014; Brewer 2009; Zemestani 2016; Zgierska 2017). None of the primary outcomes were assessed objectively.

Secondary outcome measures

Eleven studies reported eligible data for assessing craving intensity. The specific outcomes assessed included desire to use from the Heroin Craving Questionnaire (Abed 2019), Alcohol Craving Questionnaire Revised (Bevan 2012), Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (Black 2019; Bowen 2009; Bowen 2014; Garland 2010; Garland 2016; Shorey 2017; Zemestani 2016), subjective craving during stress provocation (Brewer 2009), and the Craving Scale from the GAIN assessment (Davis 2018). Thirty‐four studies reported eligible data for evaluating treatment acceptability in the form of study attrition. Four studies reported occurrence of serious adverse events (Bowen 2014; Brewer 2009; Zemestani 2016; Zgierska 2017). Treatment acceptability in the form of study attrition was the only outcome that was assessed objectively.

Studies awaiting classification and ongoing studies

Twenty‐three studies were identified as awaiting classification. Eleven studies (13 articles) were identified as ongoing studies.

Excluded studies

The full‐text screening resulted in 68 references being excluded due to ineligible criteria. Reasons for exclusion included:

not patients with SUD (24 references);

not MBI (24 references);

not randomized or quasi‐randomized (11 references);

did not include no treatment or other treatment comparison (5 studies);

not face‐to‐face delivery (3 studies);

not individually randomized (1 study);.

Risk of bias in included studies

Results of risk of bias assessment is displayed in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

3.

Allocation

Seventeen studies were at low risk for allocation bias based on reporting adequate methods of sequence generation. The remaining 23 studies were at unclear risk for allocation bias due to insufficient reporting of sequence generation methods. Seven studies were at low risk for allocation bias based on reporting adequate methods of allocation concealment (Alegria 2019; Bevan 2012; Black 2019; Garland 2016; Glasner 2017; Zemestani 2016; Zgierska 2017). The remaining 33 studies were at unclear risk for allocation bias due to insufficient reporting of allocation concealment.

We examined equivalence of baseline characteristics as an additional source of selection bias. Twenty‐nine studies were at low risk for bias due to non‐equivalence of baseline characteristics, with mindfulness‐based intervention (MBI) and control conditions matched at baseline. Five studies were at high risk for bias due to non‐equivalence of baseline characteristics. This source of bias was unclear in six studies.

Blinding

All studies were at high risk for performance bias due to a lack of participant blinding, which is unsurprising given the behavioral nature of the MBIs being evaluated. With the exception of treatment acceptability in the form of attrition, all outcomes were assessed subjectively via self‐report and were therefore at high risk for detection bias (17 studies). Attrition was assessed objectively in all studies were it was assessed (34 studies). Five studies did not include an eligible outcome.

Incomplete outcome data

Fourteen studies were at low risk for attrition bias due to a lack of missing outcome data, adequate treatment of missing outcome data (e.g. through multiple imputation), balanced missingness across groups, and/or similar reasons for missingness across groups. Risk for attrition bias was unclear in 20 studies and high in six studies due to the reasons noted (e.g. missing outcome data that differed in reason and/or amount across conditions).

Selective reporting

Twelves studies were at low risk for reporting bias due to the availability of a study protocol or preregistration with all of the outcomes reported or through the identification of plausible primary outcomes within the published report itself. Risk for reporting bias was unclear in 24 studies. Risk of reporting bias was high in four studies due to the availability of a study protocol but a lack of reporting of pre‐specified outcomes.

Other potential sources of bias

No other potential sources of bias were considered.

Effects of interventions

Mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) versus no treatment

Twenty‐four studies included a comparison between MBI and no treatment. As noted, these comparisons may have included standard of care interventions which were received by both the MBI and no treatment conditions (i.e. no additional treatment was provided to the control group).

Primary outcome measures

Continuous abstinence rate

One study with 112 participants (Zgierska 2017) provided results for comparisons with no treatment controls at post‐treatment and follow‐up (four months post‐treatment). The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to no treatment on continuous abstinence rate at post‐treatment (Analysis 1.1;risk ratio ( RR) = 0.96, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.44, 2.14) and follow‐up (Analysis 1.2; RR = 1.04, 95% CI 0.54, 2.01).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Mindfulness versus no treatment, Outcome 1: Continuous abstinence at post‐treatment

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Mindfulness versus no treatment, Outcome 2: Continuous abstinence at follow‐up

Percentageof days with substance use

Four studies with 248 participants (de Dios 2012; Machado 2020; Mermelstein 2015; Zgierska 2017) provided results for comparisons with no treatment controls at post‐treatment and three studies with 167 participants (de Dios 2012; Zgierska 2017) provided results for comparisons with no treatment controls at follow‐up (three to four months post‐treatment). The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to no treatment on percentage days with substance use at post‐treatment (Analysis 1.3; standardized mean difference (SMD) = 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.37, 0.47) and follow‐up (Analysis 1.4; SMD = 0.21, 95% CI ‐0.12, 0.54).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Mindfulness versus no treatment, Outcome 3: Percentage days with substance use at post‐treatment

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Mindfulness versus no treatment, Outcome 4: Percentage days with substance use at follow‐up

Consumed amount

Three studies with 221 participants (Machado 2020; Mermelstein 2015; Zgierska 2017) provided results for comparisons with no treatment controls at post‐treatment and two studies with 142 participants (Machado 2020; Zgierska 2017) provided results for comparisons with no treatment controls at follow‐up (three to four months post‐treatment). The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to no treatment on consumed amount at post‐treatment (Analysis 1.5; SMD = 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.31, 0.52) and follow‐up (Analysis 1.6; SMD = 0.33, 95% CI 0.00, 0.66).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Mindfulness versus no treatment, Outcome 5: Consumed amount at post‐treatment

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Mindfulness versus no treatment, Outcome 6: Consumed amount at follow‐up

Adverse event rate

One study with 112 participants (Zgierska 2017) provided results for comparisons with no treatment controls. No adverse events were reported in either condition.

Secondary outcome measures

Craving intensity

Two studies with 128 participants (Abed 2019; Bevan 2012) provided results for comparisons with no treatment controls at post‐treatment. The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to no treatment on craving intensity at post‐treatment (Analysis 1.7; SMD range = ‐4.84 to ‐0.32). Results could not be pooled due to high heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 90%).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Mindfulness versus no treatment, Outcome 7: Craving intensity at post‐treatment

Treatment acceptability (attrition)

Twenty‐one studies with 1087 participants (Abed 2019; Alizadehgoradel 2019; Alterman 2004; Asl 2014a; Asl 2014b; Bein 2015; Bevan 2012; Brown 2017; de Dios 2012; Foroushani 2019; Imani 2015; Jenaabadi 2017; Machado 2020; Marfurt 2007; Margolin 2006; Mermelstein 2015; Shorey 2017; Vowles 2020; Wongtongkam 2019; Yaghubi 2017; Zgierska 2017) provided results for comparisons with no treatment controls (Figure 4). MBIs result in little to no increase in study attrition relative to no treatment (Analysis 1.8; RR = 1.04 95% CI 0.77 to 1.40); high‐certainty evidence.

4.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Mindfulness versus no treatment, Outcome 8: Treatment acceptability (attrition)

Serious adverse event rate

One study with 112 participants (Zgierska 2017) provided results for comparisons with no treatment controls. No serious adverse events were reported in either condition.

Sensitivity analyses

Sufficient studies to conduct a fixed‐effect model sensitivity analysis (>10 studies) were available only for treatment acceptability. Results indicated that MBIs result in little to no increase in study attrition relative to no treatment (Analysis 1.9; RR = 1.13 95% CI 0.84, 1.50).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Mindfulness versus no treatment, Outcome 9: Treatment acceptability (attrition): sensitivity analysis (fixed‐effects model)

Mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) versus other treatments

Nineteen studies included a comparison between MBI and another treatment.

Primary outcome measures

Continuous abstinence rate

One study with 286 participants (Bowen 2014) provided results for comparisons with other treatment controls at post‐treatment and follow‐up (10 months post‐treatment). The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to other treatment controls on continuous abstinence rate at post‐treatment (Analysis 2.1; RR = 0.80, 95% CI 0.45, 1.44) and follow‐up (Analysis 2.2; RR = 0.57, 95% CI 0.28, 1.16).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Mindfulness versus other treatments, Outcome 1: Continuous abstinence at post‐treatment

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Mindfulness versus other treatments, Outcome 2: Continuous abstinence at follow‐up

Percentage days with substance use

Five studies with 523 participants (Bowen 2009; Bowen 2014; Brewer 2009; Davis 2018; Witkiewitz 2014) provided results for comparisons with other treatment controls at post‐treatment and three studies with 409 participants (Bowen 2009; Bowen 2014; Davis 2018) provided results for comparisons with other treatment controls at follow‐up (4 to 10 months post‐treatment). The evidence suggests that MBIs reduce percentage of days with substance use slightly relative to other treatments at post‐treatment (Analysis 2.3; SMD = ‐0.21, 95% CI ‐0.45, 0.03) and follow‐up (Analysis 2.4; SMD = ‐0.39, 95% CI ‐0.96, 0.17); both results low‐certainty evidence.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Mindfulness versus other treatments, Outcome 3: Percentage days with substance use at post‐treatment

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Mindfulness versus other treatments, Outcome 4: Percentage days with substance use at follow‐up

Consumed amount

One study with 25 participants (Davis 2013) provided results for comparisons with other treatment controls at post‐treatment. The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MBIs relative to other treatments on consumed amount at post‐treatment (Analysis 2.5; SMD = ‐0.42, 95% CI ‐1.23 to 0.39).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Mindfulness versus other treatments, Outcome 5: Consumed amount at post‐treatment

Adverse event rate

Two studies with 322 participants (Bowen 2014; Brewer 2009) provided results for comparisons with other treatment controls. No adverse events were reported in either condition. One study with 74 participants (Zemestani 2016) included an other treatment control but results were only available for the MBI condition. No adverse events were reported.

Secondary outcome measures

Craving intensity

Nine studies with 971 participants (Black 2019; Bowen 2009; Bowen 2014; Brewer 2009; Davis 2018; Garland 2010; Garland 2016; Shorey 2017; Zemestani 2016) provided results for comparisons with other treatment controls at post‐treatment. Results could not be pooled due to high heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 90%) (Analysis 2.6; SMD range = ‐1.43 to 1.00). Four studies with 415 participants (Bowen 2009; Bowen 2014; Davis 2018; Zemestani 2016) provided results for comparisons with other treatment controls at follow‐up (three to six months post‐treatment) (Analysis 2.7; SMD range = ‐2.07 to ‐0.14). Results could not be pooled due to high heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 90%).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Mindfulness versus other treatments, Outcome 6: Craving intensity at post‐treatment

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Mindfulness versus other treatments, Outcome 7: Craving intensity at follow‐up

Treatment acceptability (attrition)

Fourteen studies with 1531 participants (Alegria 2019; Black 2019; Bowen 2009; Bowen 2014; Brewer 2009; Davis 2013; Garland 2010; Garland 2016; Garland 2019; Glasner 2017; Jenaabadi 2017; Lee 2011; Witkiewitz 2014; Zemestani 2016) provided results for comparisons with other treatment controls (Figure 5). MBIs result in little to no increase in study attrition relative to other treatment controls (Analysis 2.8; RR = 1.06 95% CI 0.89 to 1.26); high‐certainty evidence.

5.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Mindfulness versus other treatments, Outcome 8: Treatment acceptability (attrition)

Serious adverse event rate

Two studies with 322 participants (Bowen 2014; Brewer 2009) provided results for comparisons with other treatment controls. No serious adverse events were reported in either condition. One study with 74 participants (Zemestani 2016) included an other treatment control but results were only available for the MBI condition. No serious adverse events were reported.

Sensitivity analyses

Sufficient studies to conduct a fixed‐effect model sensitivity analysis (>10 studies) were available only for treatment acceptability. Results indicated that MBIs result in little to no increase in study attrition relative to no treatment (Analysis 2.9; RR = 1.07 95% CI 0.91, 1.25).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Mindfulness versus other treatments, Outcome 9: Treatment acceptability (attrition): sensitivity analysis (fixed effects model)

Discussion

Summary of main results

Mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) were compared with no treatment or other treatments on four primary outcomes (continuous abstinence rate, percentage of days with substance use, consumed amount, adverse event rate) and three secondary outcomes (craving intensity, treatment acceptability, serious adverse events).

Twenty‐four studies included a comparison between MBIs and no treatment. Relative to no treatment, the evidence was very uncertain about the effects of MBIs on all primary and secondary outcomes with the exception of treatment acceptability (differential attrition). MBIs resulted in little to no increase in study attrition relative to no treatment.

Nineteen studies included a comparison between MBI and another treatment. Relative to other treatments, MBIs may reduce percentage of days with substance use slightly at post‐treatment and follow‐up (4 to 10 months). However, the confidence intervals are compatible with both an improvement and little to no difference. MBIs result in little to no increase in study attrition relative to other treatments. The evidence is very uncertain regarding other outcomes including continuous abstinence rate, consumed amount, and craving intensity.

Four studies reported data on adverse events, with all reporting the absence of adverse events.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Of the eligible 40 studies, 35 provided data usable for at least one meta‐analysis. However, no study included data on all outcome measures and many studies included data on only one outcome measure (typically acceptability in the form of differential attrition). Only one study (Foroushani 2019) reported eligible data in a form that did not allow estimation of an effect size. It is possible that other studies measured outcomes that would have been eligible, but data were not available. The limited number of published protocols or preregistrations makes it difficult to determine precisely how much unpublished data may exist.

The majority of studies were conducted in the USA with several also occurring in Iran as well as Thailand, China, Taiwan, and Spain. Studies were conducted between 2004 and 2020. Almost half of the studies included individuals with various substance use disorders (SUDs) with a large proportion focusing on opioids and several focusing on alcohol. Almost half of the studies required a formal SUD diagnosis of some kind for inclusion. Slightly less than half of the studies investigated mindfulness‐based relapse prevention (MBRP) or an adaptation of MBRP with several investigating mindfulness‐oriented recovery enhancement (MORE) or an adaptation of MORE. Most interventions were delivered in a group and were similar in duration to mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR) (i.e. eight weeks). The samples were predominantly male. Given the diversity in study characteristics in terms of the samples and interventions, results of this review can theoretically be applied to MBIs for SUDs generally.

Limited information was available regarding the safety of MBIs for SUDs. However, no adverse events were reported in the four studies including this information.

Quality of the evidence

All studies were at high risk for performance bias due to an inability to blind participants engaging in a behavioral intervention. No studies assessed a substance use outcome objectively, so these outcomes were coded as at high risk for detection bias. Study attrition is by definition an objective (i.e. non‐self‐report) outcome, so treatment acceptability in the form of attrition was assessed as low risk for detection bias. Risk for selection bias due to randomization or allocation procedures was often unclear due to a lack of reporting. Risk of bias due to non‐equivalence at baseline was considered as another source of selection bias and was assessed as high in five studies. Risk of attrition bias was high in six studies. Risk of reporting bias was high in four studies and unclear in 24 studies.

Based on GRADE, the certainty of evidence was high for treatment acceptability (i.e. attrition). Certainty was low for percentage of days with substance use at post‐treatment and follow‐up for comparisons with other treatments due to inconsistency (sample size <400) and risk of bias (unblinded outcome assessment). For all other outcomes, certainty was very low due to inconsistency (sample size <400, 95% CI including both an appreciable benefit and an appreciable harm, 95% CI including both an effect not relevant to participants and an appreciable harm), risk of bias (unblinded outcome assessment), and/or inconsistency (I2 ≥ 90%).

Potential biases in the review process

Publication bias was not evaluated as 10 studies were not available for any of the primary outcomes. We sought to minimize publication bias through an extensive search process of both peer‐reviewed studies and dissertations, reviewing other recent meta‐analyses in this area, as well as contacting authors of ongoing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of MBIs for SUDs. Nonetheless, publication bias remains a plausible source of bias, particularly given the frequency at which studies were found to be of unclear risk for reporting bias (i.e. selective reporting).

Due to the limited number of available studies for estimating substance use outcomes, we used the last available follow‐up for each study. While this was viewed as providing the most robust estimate of sustained effects by maximizing the amount of data used and follow‐up periods were typically within two to three months of each other, separating follow‐up data into other groupings (e.g. short‐term follow‐up, medium‐term follow‐up, long‐term follow‐up) may have resulted in different results.

Our review protocol prespecified our primary and secondary outcomes. The outcomes assessed did not include some potentially meaningful outcomes (e.g. negative effects of substance use). A future review that includes additional outcome measures may arrive at differing conclusions.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Three meta‐analyses have evaluated the effects of MBIs on SUD outcomes. Li 2017 conducted a meta‐analysis of 34 RCTs, 15 of which were included in the current review. However, Li 2017 included studies focused on smoking cessation as well as interventions that did not emphasize formal mindfulness meditation practice (e.g. Murphy 1986). Li 2017 also did not require a formal or informal SUD diagnosis for inclusion (e.g. Garland 2014a) and analyses collapsed across‐control condition types. Li 2017 reported greater reductions in substance use (standardized mean difference (SMD) = ‐0.33) and craving (SMD = ‐0.68) at post‐treatment for MBIs relative to control conditions.

Grant 2017 conducted a meta‐analysis of nine RCTs testing MBRP for substance abuse. Eight of the included studies were also included in the current review (Uhlig 2009 was not individually randomized). Grant 2017 also collapsed across‐control condition types. Grant 2017 reported that MBRP did not differ from controls on relapse to substance use (odds ratio([OR) = 0.72), frequency of use (SMD = 0.02), quantity of use (SMD = 0.26), or treatment dropout (OR = 0.81). Grant 2017 reported that MBRP was associated with larger reductions in withdrawal and craving symptoms (SMD = ‐0.13) and negative consequences (SMD = ‐0.23).

Goldberg 2018 conducted a meta‐analysis of 142 RCTs testing MBIs for various psychiatric conditions. Effects were estimates for SUDs at post‐treatment and follow‐up. Twelve of the included studies were also included in the current review. Although Goldberg 2018 reported results separated by control condition type, results were collapsed across SUD outcome measure types. Goldberg 2018 included outcomes that were not eligible for inclusion in the current review (e.g. Addiction Severity Index). Goldberg 2018 reported that MBIs did not differ from no treatment on SUD outcomes at post‐treatment (SMD = 0.35), showed larger improvement relative to other treatment controls at post‐treatment (SMD = 0.27), but not at longest follow‐up (SMD = 0.38).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.