Dear Editor

We have read the article by Lim et al. with great interest.1 The authors found rapid and robust antibody responses after adenovirus vector-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in previously infected individuals. So far, antibody responses induced by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination have been intensively investigated.2 No requirement for the second SARS-CoV-2 vaccine has been discussed in previously infected individuals because of sufficient antibody responses elicited by only one dose.3 However, the details

of antibody responses after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in nursing home residents have not been fully characterized, although a few studies have been briefly reported.4, [5], [6] In this study, we evaluated the antibody response to BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination in SARS-CoV-2-naive and previously infected nursing home residents, with healthcare workers as a control. COVID-19 outbreaks have severely affected nursing home residents.7 Infection control during the outbreaks in nursing facilities is a critical public health issue.

This study was conducted as a serological follow-up evaluation after reporting a COVID-19 outbreak in a nursing facility in April 2020.8 There was an outbreak in the hospital adjacent to the facility in January 2021. SARS-CoV-2-infected healthcare workers in the hospital were also included in the study control. BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination was performed twice at a 21-day interval from May to July, 2021. Serum samples after the first and second dose were collected on the scheduled day 21. Serological testing was performed using the serum samples collected before and after vaccination. The quantitative levels of IgG antibodies for the spike antigen of SARS-CoV-2 were examined using the Abbott Architect immunoassays (SARS-CoV-2 IgG II Quant, Abbott, Park, IL, USA). The anti-spike IgG levels of ≥ 4,160 AU/mL were used as a surrogate marker of highly effective antibody neutralization, based on the manufacturer's instruction. Anti-spike antibody levels were also measured using the Roche immunoassays (Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S, Roche, Burgess Hill, UK). The details of the methods are shown in Supplementary methods.

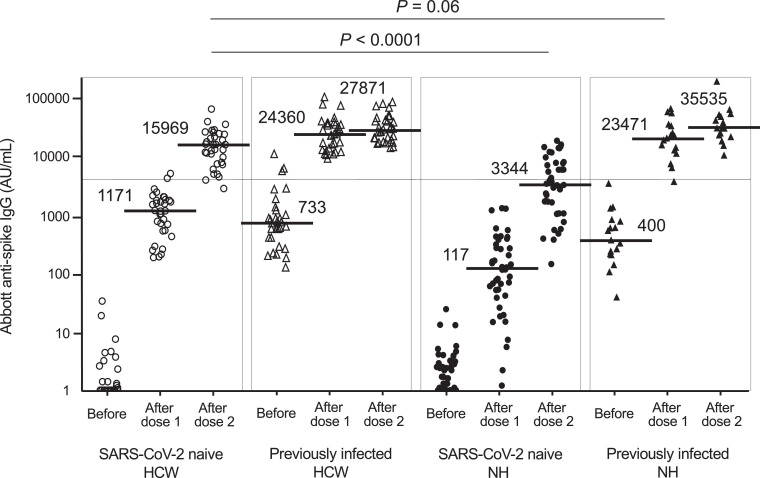

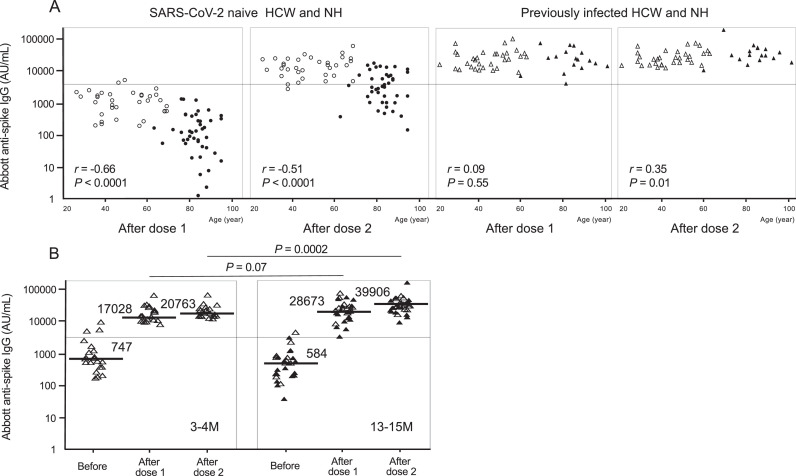

This study included 126 individuals: 60 nursing home residents (mean age, 84.0 years; 43 SARS-CoV-2-naive and 17 previously infected) and 66 healthcare workers (mean age, 46.7 years; 34 SARS-CoV-2-naive and 32 previously infected). The baseline clinical characteristics of the 126 individuals are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Fig. 1 shows Abbott anti-spike IgG antibody levels before and after vaccination. The median IgG level in SARS-CoV-2-naive residents after the second dose was approximately five-fold lower than that in SARS-CoV-2-naive healthcare workers after the second dose (3,344vs 15,969 AU/mL, P < 0.0001). The frequency of IgG levels of ≥ 4,160 AU/mL in residents (41.9%, 18/43) was significantly lower than that in healthcare workers (94.1%, 32/34) (P < 0.0001). IgG levels in previously infected residents after the first dose were comparable to those in SARS-CoV-2-naive healthcare workers after the second dose. The results of Roche anti-spike antibody levels were similar to those of Abbott antibody levels (Supplementary Fig. 1). The basic data of Abbott and Roche antibody levels are shown in Supplementary Table 2. The relationship between age and post-vaccination anti-spike IgG levels is shown in Fig. 2 . In SARS-CoV-2-naive healthcare workers and residents, increasing age significantly correlated with a decrease in IgG levels after both doses. In contrast, in previously infected healthcare workers and residents, a decline in antibody levels with increasing age was not shown. Next, IgG levels in the previously infected individuals were compared between two groups based on the duration from infection to vaccination (Fig. 2B). Post-vaccination IgG levels in the group with 13 to 15 months after infection appeared to be higher than in the group with 3 to 4 months, regardless of healthcare workers or residents. It was particularly significant in the comparison after the second dose (P = 0.0002).

Fig. 1.

Abbott anti-spike IgG antibody levels before and after BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination in SARS-CoV-2-naive and previously infected healthcare workers and nursing home residents. The white circles indicate data of SARS-CoV-2-naive healthcare workers (n = 34). The white triangles indicate data of previously infected healthcare workers (n = 32). The black circles indicate data of SARS-CoV-2-naive residents (n = 43). The black triangles indicate data of previously infected residents (n = 17). The horizontal solid bars and numbers in each group indicate the median values. The horizontal line indicates the value of 4,160 AU/mL, a threshold level indicating highly effective antibody neutralization. 50 AU/mL is the cut-off value. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; HCW, healthcare workers; NH, nursing home residents.

Fig. 2.

A. Association of age with Abbott anti-spike IgG antibody levels after BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination. The white circles indicate data of SARS-CoV-2-naive healthcare workers. The white triangles indicate data of previously infected healthcare workers. The black circles indicate data of SARS-CoV-2-naive nursing home residents. The black triangles indicate data of previously infected residents. The horizontal line indicates the value of 4,160 AU/mL. B. Comparison of pre- and post-vaccination anti-spike IgG antibody levels by the duration from infection to vaccination in previously infected healthcare workers and residents. The group with 3 to 4 months from infection to vaccination (3-4 M) included 21 previously infected healthcare workers. The group with 13 to 15 months from infection to vaccination (13-15 M) included 11 previously infected healthcare workers and 17 previously infected residents. The white triangles indicate data of previously infected healthcare workers. The black triangles indicate data of previously infected residents. The horizontal solid bars and numbers in each group indicate the median values. The horizontal line indicates the value of 4,160 AU/mL. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; HCW, healthcare workers; NH, nursing home residents.

In this study, we showed that after the second dose, anti-spike IgG levels in SARS-CoV-2-naive residents were extremely lower than those in SARS-CoV-2-naive healthcare workers. When using Abbott anti-spike IgG levels of ≥ 4,160 AU/mL as a threshold level indicating highly effective antibody neutralization, our results suggested that approximately 60% of SARS-CoV-2-naive residents after vaccination could not achieve antibody levels required to protect them against infection. SARS-CoV-2-naive nursing home residents may remain much more vulnerable to breakthrough infection than the general adult population. The clinical efficacy of the third (booster) dose of BNT162b2 vaccination in the elderly has just been reported.9 The requirement of a high application order of re-vaccination may be reasonable in SARS-CoV-2-naive nursing home residents. The dynamics of antibody levels after vaccination in SARS-CoV-2 previously infected nursing home residents was completely different from that of SARS-CoV-2-naive residents. In this study, we showed that in previously infected residents after the first dose, antibody levels comparable to SARS-CoV-2-naive healthcare workers after the second dose were induced. Our findings suggest that even advanced aged nursing home residents only require one vaccine dose within approximately one year of their SARS-CoV-2 infection. The study on the third vaccination in the elderly did not include individuals previously infected with SARS-CoV-2.9 It is likely that there is currently little discussion on the necessity of the third dose for previously infected individuals, including nursing home residents.

There has been little information on the factors related to rapidly increasing antibody responses after the vaccination of SARS-CoV-2 previously infected nursing home residents. It would be evident in this study that aging is not associated with an increase in post-vaccination antibody levels in SARS-CoV-2 previously infected individuals, at least within 15 months after infection. We obtained a finding that post-vaccination antibody levels were significantly higher in individuals with the longer duration after infection. Antibody responses after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination were more pronounced in adults with >3 months after infection than in those with 1to 2 months.10 Intriguingly, SARS-CoV-2-specific memory function to demonstrate booster responses after vaccination might be maintained more effectively in individuals with the period of one year after infection than in those with three months, even in advanced aged nursing home residents.

Abbott anti-spike IgG levels of ≥ 4,160 AU/mL, which were used as a threshold of highly efficient antibody neutralization, could not necessarily reflect the standard levels required to protect against clinical SARS-CoV-2 infection. Post-vaccination antibody levels of SARS-CoV-2-naive residents were frequently below the threshold. However, lower antibody levels may work to protect against the infection. On the other hand, antibody levels required to protect against current SARS-CoV-2-variant infection may exceed the threshold, because current vaccines are derived from wild strains. A further observation will be needed regarding how much antibody levels after current vaccination could result in a breakthrough infection with circulating variant viruses, not only in SARS-CoV-2-naive residents but also in previously infected ones.

In conclusion, SARS-CoV-2-naive nursing home residents may not achieve sufficient antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 infection, despite complete vaccination. In contrast, previously infected residents could maintain rapid and robust antibody responses to vaccination even more than one year after infection. We believe that our serological data of nursing home residents could be of significant use to many healthcare professionals for future control measures for COVID-19 outbreaks.

Declaration of Competing Interest

There are no competing interests to declare for any of the authors.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

First, we would like to thank Atsushi Hisaeda and Seiji Sasaki for their technical support. Next, we sincerely thank Junko Nakahara for all of her support in the investigation. We would also like to thank the entire Department of Clinical Chemistry (Kanenokuma Hospital), including Tomoyuki Fukamachi. Finally, we thank all staff members of the facility for their dedicated work.

Funding

No external funding was received for this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2021.10.011.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Lim S.Y., Kim J.Y., Lee J.A., Kwon J.S., Park J.Y., Cha H.H., et al. Immune responses and reactogenicity after ChAdOx1 in individuals with past SARS-CoV-2 infection and those without. J Infect. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.07.032. Jul 28 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Focosi D., Baj A., Maggi F. Is a single COVID-19 vaccine dose enough in convalescents? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:2959–2961. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1917238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wise J. Covid-19: people who have had infection might only need one dose of mRNA vaccine. BMJ. 2021;372:n308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blain H., Tuaillon E., Gamon L., Pisoni A., Miot S., Picot M.-.C., et al. Spike antibody levels of nursing home residents with or without prior COVID-19 3 weeks after a single BNT162b2 vaccine dose. JAMA. 2021;325:1898–1899. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.6042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Praet J.T., Vandecasteele S., De Roo A., De Vriese A.S., Reynders M. Humoral and cellular immunogenicity of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in nursing home residents. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab300. Apr 7 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canaday D.H., Carias L., Oyebanji O.A., Keresztesy D., Wilk D., Payne M., et al. Reduced BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine response in SARS-CoV-2-naive nursing home residents. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab447. May 16 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham N.S.N., Junghans C., Downes R., Sendall C., Lai H., McKirdy A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection, clinical features and outcome of COVID-19 in United Kingdom nursing homes. J Infect. 2020;81:411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong Y., Tani N., Ikematsu H., Terazawa N., Nakashima H., Shimono N., et al. Genetic testing and serological screening for SARS-CoV-2 infection in a COVID-19 outbreak in a nursing facility in Japan. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:263. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05972-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bar-On Y.M., Goldberg Y., Mandel M., Bodenheimer O., Freedman L., Kalkstein N., et al. Protection of BNT162b2 vaccine booster against Covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1393–1400. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2114255. Sep 15 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anichini G., Terrosi C., Gandolfo C., Savellini G.G., Fabrizi S., Miceli G.B., et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody response in persons with past natural infection. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:90–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2103825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.