Dear Editor,

Studies analyzing the persistence of protective immunity after SARS-CoV-2 infection are crucial to better understand the future dynamics of Covid-19 pandemic. We read with interest the results of Thangaraj et al.1 regarding the evolution over time of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies up to 7 months after an infection. Following 755 individuals, they observed a clear waning of anti-nucleocapside and anti-spike antibodies, but the persistence of neutralizing, anti-receptor binding domain (RBD) antibodies (NAb) in 86.2% of participants 181–232 days after RT-PCR diagnosis; those with more severe Covid-19 had higher NAb titres.

We conducted a follow-up of NAb titres 6 months (217 ± 19 days) and up to 1 year (377 ± 12 days) after a RT-PCR proven infection in 67 patients, infected between March and April 2020. Quantitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies targeting S1-RBD was determined by the Siemens SARS-CoV-2 IgG (sCOVG) assay on the Atellica IM platform (Siemens, Munich, Germany). Neutralizing antibody quantification was performed according to the previously published protocol,2 based on a pseudotyped virus entry assay using a luciferase reporter gene. Pseudo-virus displaying full-length SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (derived from USA-WA1/2020 strain) was produced in HEK293T cells and used to infect HeLa-ACE2 cells. The result from this assay is expressed as the serum dilution required to reduce infection by 50% (ID50). The study was approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est I on 20 August 2020 (Ref. 2020–84).

Mean age at positive RT-PCR was 59.8 ± 12 years; 42 (67.5%) of patients were males. Regarding Covid-19 severity, 17 (25.4%) individuals did not require oxygen supplementation, 17 (25.4%) required oxygen at a maximum of 2 L/min, and 33 (49.2%) required more than 2 L/min oxygen, among whom 29 were admitted to an intensive care unit. Dexamethasone was used in 20 of these 33 patients during the acute Covid-19 phase, all in patients admitted to ICU.

At the first sample (N = 67), median Atellica serology titre was 11.0 U/mL [IQR: 5–27]. It was correlated with age (p< 0.001, rho= 0.411) and severity (suppl. Table 1). Among those who required oxygen supplementation > 2 L/min, there was no significant difference according to steroid use (suppl Table 1). At this same time, the median ID50 NAb titre was 166 [IQR: 87–372]; two patients had no detectable NAb activity. Neutralization titres were correlated with age (p = 0.014, rho= 0.302) and severity (no oxygen vs. oxygen > 2 L/min: p = 0.020) (suppl. Table 1). Among individuals requiring oxygen supplementation > 2 L/min, there was no significant difference according to steroid use, although there was a trend toward lower titres for those who received steroids (suppl. Table 1). A positive correlation was observed between SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies as detected by the Atellica serology assay and the NAb titres (p< 0.001, rho= 0.455].

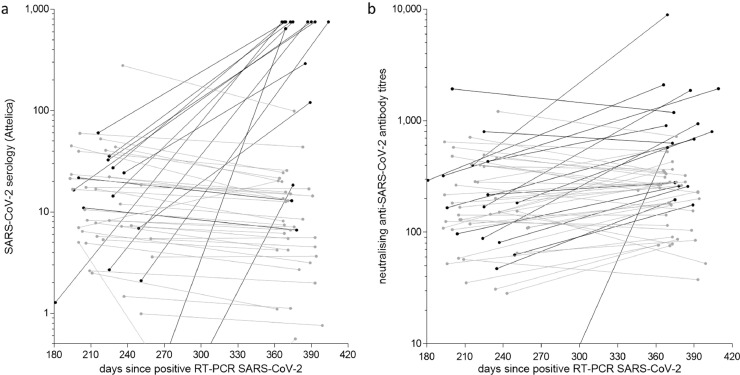

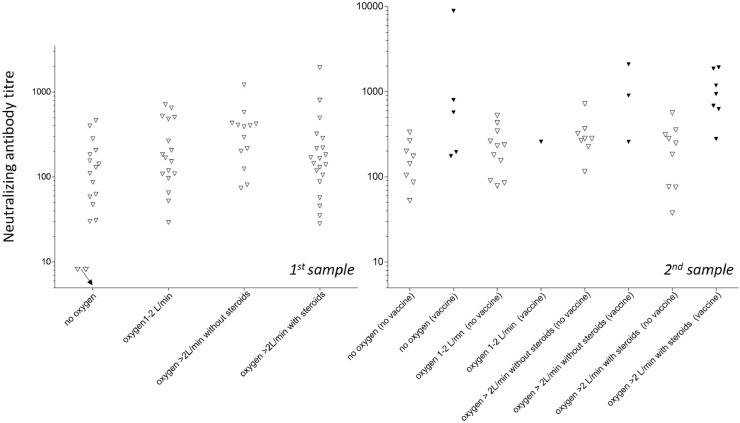

At the second sample (N = 52), 16 participants had received a first dose of the Covid-19 vaccine (Pfizer/BioNTech™, Moderna™, or AstraZeneca™) between the two samples. Median Atellica serology titre was 12.9 U/mL [4.8–85.1], with striking differences according to the vaccine status. Indeed, the median titre for those vaccinated before the second sample was 750.0 U/mL [16.2–750] vs. 6.9 U/mL [3.4–15.4] for unvaccinated subjects (p< 0.001) (Fig. 1 ); the Atellica serology titres remained stable between the two dates for unvaccinated individuals but greatly increased among the vaccinated. Median ID50 neutralizing titres was 268 [177–545], with the same difference as above according to vaccine status. Indeed, the median ID50 titre for patients vaccinated between the two samples was 742 [269–1528] vs 237 [122–320] for unvaccinated subjects (p< 0.001) (Fig. 1). This difference was observed throughout the different severity groups (Fig. 2 ). There was no difference in titre according to the initial use of steroids (Suppl. Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Quantitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies by Atellica serology (a) and neutralising antibody titres (b) at the two sample dates according to vaccination between the two titres (grey: no vaccination, black: vaccination). (The samples with no detectable antibodies are below the X axis).

Fig. 2.

Neutralizing antibody titres at the two sampling dates according to severity, steroid use, and (for the second date) vaccination (black triangles) or not (white triangles). (The two samples with no detectable NAbs are figured above the X axis with an arrow).

Correlates of protection for Covid-19 are not completely established. However, the presence of NAb is associated with protection against many viral infections, and recent studies showed that the risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection was correlated with the NAb titres.3 NAb response have therefore been particularly explored, mostly in the first months after SARS-CoV-2 infection, with somehow contrasting results.

We observed in our cohort that nearly all patients (65/67) had detectable NAb titres 7 months after their symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, and that titres were stable between 6 months and 1 year (as measured by both EIA and neutralization assay). Relatively few studies have yet assessed NAb titers 1 year after infection; in a cohort of 73 subjects,4 only 43% of individuals had detectable NAb titres after 1 year (vs 98% of 25 subjects sampled at months 5,6); in contrast, in a cohort of 620 individuals (58% inpatients and 42% outpatients),5 the proportion with detectable NAb was high (80 to 90%) at 1 month and stable at 13 months (70–85%); in another recent study,6 97% of 367 patients had detectable NAb against initial SARS-CoV-2 strain at 13 months. In these different studies, those with more severe Covid-19 had higher NAb titres, as observed in our participants.

We did not observed a significant influence of steroid therapy at the acute phase on the long-term NAb titres; this had already been observed during earlier follow-up (< 1 month).7

Although unintended when we designed the study, we observed the expected booster effect of the vaccine dose. This so-called “hybrid immunity” has been observed in previous studies,8 leading the French health authorities to recommend in early 2021 that subjects with a past SARS-CoV-2 infection should receive only one instead of two doses of the mRNA-based vaccine or AstraZeneca™ ChAd-based vaccine.9

Our study has several limitations, the first being its relatively small population size. Moreover, we did not assess the neutralizing potency of NAb against the Delta variant, which is less efficiently targeted by NAb induced by an infection with the viral strains circulating in 2020. Indeed, a recent pooled analysis.10concluded that the SARS-CoV-2 lineages Beta, Gamma, and Delta were less sensitive to NAb induced by a previous (2020) infection, with an average 4.1-fold (95% CI: 3.6–4.7), 1.8-fold (1.4–2.4), and 3.2-fold (2.4–4.1) reduction in IC50 titres.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Olivier Epaulard: Visualization, Writing – original draft. Marlyse Buisson: Writing – review & editing. Benjamin Nemoz: Visualization, Writing – original draft. Marion Le Maréchal: Visualization, Writing – original draft. Nicolas Terzi: Writing – review & editing. Jean-François Payen: Writing – review & editing. Marie Froidure: Writing – review & editing. Myriam Blanc: Writing – review & editing. Anne-Laure Mounayar: Writing – review & editing. Fanny Quénard: Writing – review & editing. Isabelle Pierre: . Patricia Pavese: Writing – review & editing. Raphaele Germi: Writing – review & editing. Laurence Grossi: Writing – review & editing. Sylvie Larrat: Writing – review & editing. Pascal Poignard: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Julien Lupo: Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Siemens Healthineers for Atellica sCOVG reagents offered free of charge.

Funding

This work was supported by the Direction à la Recherche Clinique et à l'Innovation du CHU Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France. This funding source had not involvement in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2021.10.009.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Thangaraj J.W.V., Kumar M.S., Kumar C.G., et al. Persistence of humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2 up to 7 months post-infection: cross-sectional study, South India, 2020-21. J Infect. 2021;83(3):381–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bal A., Brengel-Pesce K., Gaymard A., et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of symptomatic healthcare workers with suspected Covid-19: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):14977. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93828-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergwerk M., Gonen T., Lustig Y., et al. Covid-19 breakthrough infections in vaccinated health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2021:1474–1484. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109072. Under press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiang T., Liang B., Fang Y., et al. Declining levels of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent Covid-19 patients one year post symptom onset. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.708523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wisnivesky J.P., Stone K., Bagiella E., et al. Long-term persistence of neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 following infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(10):3289–3291. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07057-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haveri A., Ekstrom N., Solastie A., et al. Persistence of neutralizing antibodies a year after SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Eur J Immunol. 2021 doi: 10.1002/eji.202149535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muhlemann B., Thibeault C., Hillus D., et al. Impact of dexamethasone on SARS-CoV-2 concentration kinetics and antibody response in hospitalized Covid-19 patients: results from a prospective observational study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(10):1520.e7–1520.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.06.008. Under press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crotty S. Hybrid immunity. Science. 2021;372(6549):1392–1393. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haute Autoristé de Santé. [Vaccine strategy against SARS-CoV-2 - vaccination of people with a past history of Covid-19]. https://wwwhas-santefr/jcms/p_3237355/fr/strategie-de-vaccination-contre-le-sars-cov-2-vaccination-des-personnes-ayant-un-antecedent-de-Covid-19-synthese. 2021;consulted August 11th 2021.

- 10.Chen X., Chen Z., Azman A.S., et al. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants induced by natural infection or vaccination: a systematic review and pooled meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab646. Under press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.